CHILD TO CHILD ACTIVITY

Item

- Title

- CHILD TO CHILD ACTIVITY

- extracted text

-

Child-to~Child

Activity Sheet 6.10

Chlld-to-Chlld Activity Sheets are a resource for teachers, and health and

community workers. They are designed to help children understand how to

Improve health in other children, their families, and their communities.

Topics chosen are Important for community health and suit the age, Interests

and experience of children. The text, ideas and activities may be freely

adapted to suit local conditions.

AIDS

THE IDEA

Every country has AIDS. In some countries the number of cases recognised so far are very few. In others

the disease is wide-spread and many people are dying. In all countries everybody, including children and

young people, must learn the facts about AIDS. Children everywhere in the next ten years of their lives

will be in danger of catching the AIDS virus. In countries where many young adults are infected, the future

’ of the society depends on their children’s knowledge, attitudes and practice.

This sheet gives explicit facts about how the AIDS virus is caught and how it can be prevented. It also looijs

at people’s attitudes and practices concerning AIDS. It aims to develop in children, their teachers and their

families an openness to discuss these sensitive issues, a confidence to take decisions for thehrselves, and

a sense of caring for people with AIDS.

WHAT DOES ‘AIDS’ MEAN?

A

Acquired

means ‘to get

*.

AIDS is acquired (or got) from other people who

have the AIDS virus.

I

Immune

means ‘protected’.

The body is normally immune (or protected)

against many diseases.

D

Deficiency

means ‘a lack of.

With AIDS, the body has a deficiency (or lack) of

immunity against many diseases.

S

Syndrome

means ‘a group of different signs of a disease’.

When people have AIDS they have a syndrome

or many different signs of disease.

WHAT IS AIDS?

AIDS is a disease which attacks the body’s protective

system. The body Is unable to protect itself properly

from other diseases such as diarrhoea, TB, coughs

and sores in the mouth. With AIDS, these diseases

make people very sick and they may even die.

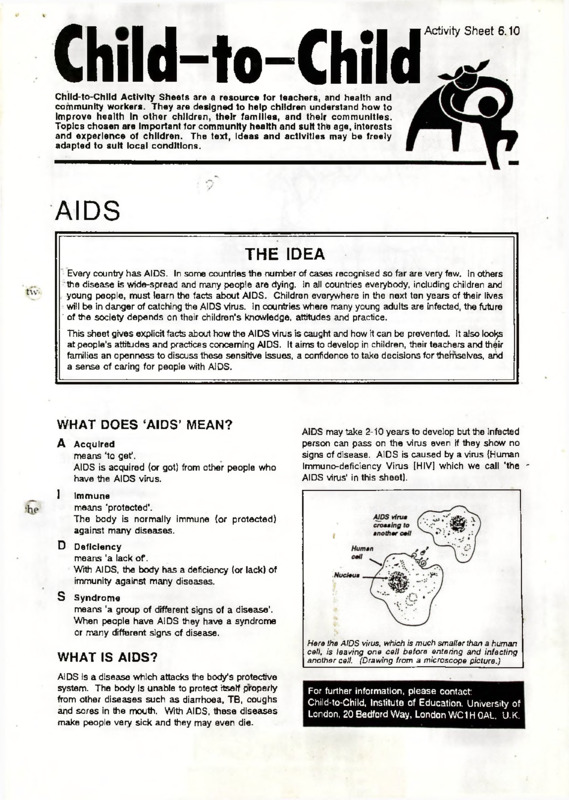

AIDS may take 2-10 years to develop but the infected

person can pass on the virus even if they show no

signs of disease. AIDS is caused by a virus (Human

Immuno-deficiency Virus [HIV] which we call 'the *

AIDS virus’ in this sheet).

Here the AIDS virus, which is much smaller than a human

cell, is leaving one cell before entering and infecting

another cell. (Drawing from a microscope picture.)

For further information, please contact:

Child-to-Child, Institute of Education. University of

London, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H OAL, U.K.

The AIDS virus can be passed

from any infected to any healthy

person by UNPROTECTED sex

ual intercourse, EVEN ON ONE

OCCASION.

Although in some cases no

symptoms are noted for up to

10 years, any infected person

remains able to infect others

during this time.

Any time after 2 years from

infection, AIDS disease can

appear and the consequences

of common infections, such

as diarrhoea, cough, etc., can

become more serious and

lead to death

HOW IS AIDS SPREAD?

There are two main ways of getting AIDS. The AIDS

virus is transmitted:

•

By sexual intercourse (vaginal or anal) with any

infected person;

•

Blood-to-blood, if someone receives blood con

taining the AIDS virus from another person:

by sharing needles or using unsterilised

needles (for injections);

by transfusion in a hospital or clinic where the

blood has not been properly tested;

by using unsterilised instruments that cut the

skin (for circumcision, scarification, tattooing,

ear-piercing, etc);

However, unborn babies can also get the AIDS virus

from their mother’s blood during pregnancy.

AIDS IS NOT SPREAD BY

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Shaking hands

Touching

Breathing

Kissing

Mosquitoes and bed bugs

Caring for those with AIDS

Cutlery and cooking utensils

Bedding and clothing

Toilets and latrines

MOTHERS WITH AIDS SHOULD CONTINUE

BREASTFEEDING. BREASTMILK IS STILL

THE BEST FOOD FOR BABIES.

J

PREVENTING THE SPREAD OF THE

AIDS VIRUS

The AIDS virus must be prevented from passing

between one person and another. It is impossible to

tell by looking at someone whether they carry the

AIDS virus. Therefore it is very important to protect

oneself against catching the virus.

HOW CAN THE AIDS

VIRUS BE PREVENTED

FROM SPREADING

BY.4SEX?

PEOPLE HAVE LIVED IN THE SAME HOUSE AS SOMEONE WITH THE

AIDS VIRUS FOr'mORE THAN 10 YEARS WITHOUT GETTING AIDS

•

By staying with one faithful

sexual partner.

The more

partners people have, the

greater the risk for both of

catching the AIDS virus.

••

By having safe sex. Kissing,

cuddling, touching are safe sex.

Penetration by the penis is not

•

By using a condom always.

Condoms, if used properly, will

do much to protect people from

AIDS and other sexually

transmitted diseases.

•

By drinking less alcohol. Alcohol

causes people to lose their

judgement about safe sex.

Drugs such as marijuana,

hashish, cocaine, heroin, etc.

can do the same thing.

•

By seeking early treatment for sores or unusual

discharge from the penis or vagina. People with

these sores or discharge are more likely to catch

and spread the AIDS virus.

.

HOW CAN THE AIDS VIRUS BE

PREVENTED FROM SPREADING BY

BLOOD?

•

By ensuring that needles, syringes and cutting

instruments are thoroughly washed after use and

sterilised by heat or chemicals. In national

immunisation programmes, health workers have

been specially trained in giving injections safely.

•

By asking for medicines which can be given by

mouth instead of by injection.

•

By avoiding contact with other people’s blood.

When giving first aid, it is important to cover cuts

and sores and wash hands well afterwards.

•

By reducing the number of blood transfusions.

Because blood can carry many diseases, doctors

now choose to give fewer blood transfusions.

School children are the future community and must

learn to be responsible for others as well as

themselves. Guided by school teachers, health

workers and community leaders, children can learn

how to protect their family, their partners and

themselves against AIDS. Children and young people

can make decisions about their own behaviour and

thereby offer safer patterns of sexual behaviour for

the community. For example, in Zambia there are

over 600 'Anti-AIDS Clubs’ organised by students in

schools throughout the country. The main aim of

these clubs is to give information on how AIDS is

spread and how to avoid it.

Here is part of a letter from a club member to the 'AntiAIDS Project in Lusaka which initiated the clubs:

/ received the things you

sent and I was very, very

glad.

I’ve signed on the

membership card and I’ve

kept the promises which I

must promise to follow as a

WHAT CHILDREN CAN DO

member of the Anti-AIDS

AIDS worldwide is a new problem and requires

changes in behaviour everywhere. Governments

can make some changes but families, communities

and schools play an important part

club. I’ve got questions for

you to help me.....

CARING FOR PEOPLE WITH AIDS

WHAT EVERY CHILD

SHOULD KNOW

We al! care for each other, In our families and

communities. Sick people, small children, old people

and orphans need our care. When a person has

AIDS, they may feel lonely and frightened. We need

to show that we care for them.

Schools should develop a policy that every

child should leave school knowing these

essential facts. Health workers and youth

group leaders can make a similar commitment

to pass on this vital knowledge.

People with AIDS need food, support, medical care,

physical help and particularly family and friends who

will accept them and listen to them. They can be

encouraged to live an active life wherever they are.

We can help them to lead a healthier life by encouraging

them to eat well, smoke less and drink less alcohol.

WHAT IS AIDS?

We cannot catch the AIDS virus by caring for someone

who is sick with AIDS. We must remember.

to protect the person with AIDS from infections;

to protect ourselves and others from the AIDS

virus.

AIDS is an infection. Al DS makes people

unable to protect themselves against many

kinds of diseases, such as diarrhoea, TB,

cough. Due to AIDS, these diseases can

make people become very sick and die.

We do this by following the usual hygiene principles:

HOW IS THE AIDS VIRUS SPREAD?

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

;

person:

•

•

•

By sexual intercourse with a person

carrying the AIDS virus;

By blood containing the AIDS virus getting

from one person’s body to another in

blood transfusions or on needles and sharp

instruments;

From an infected, pregnant mother to her

unborn child.

THE AIDS VIRUS IS NOT SPREAD BY

•

All teachers, not just the health education teacher,

have a responsibility to include teaching on AIDS in

their lessons. There are also many opportunities for

teaching about AIDS on other occasions where

children and young people gather together - in clubs,

religious meetings, youth and scout/guide groups.

The adults leading these sessions can choose the

appropriate activities. (In the following examples the

word 'teacher

*

can apply to all adults working with

children.)

|

The AIDS virus is spread from person to®

Covering open wounds on our hands;

Washing hands before and after caring for the

sick person;

Washing hands before handling food;

Keeping the sick person and surroundings clean.

ACTIVITIES FOR SCHOOL

AND YOUTH GROUPS

J

Insect bites, touching, and caring for

people with the AIDS virus.

WHEN AND WHERE TO DISCUSS ABOUT

AIDS

•

In health clubs or special anti-AIDS clubs, in

which the children learn about how AIDS is spread

and make a commitment to protect themselves

and teach others how to prevent AIDS.

•

Sometimes it is easier to talk about these sensitive

issues in single sex groups. The groups of girls

or boys can discuss issues about AIDS, share

their concerns openly, and support each other to

have confidence in the decisions they need to

make. It is easier if the adult involved is also of the

same sex.

|

|

GETTING THE FACTS RIGHT

years’ time. The teacher can ask questions like:

‘Who will you be living with?’; ‘Who will your

friends be?’; ‘How will you show your love and

friendship?’; ‘Might you try drugs, alcohol or

*;

smoking?

‘How might AIDS enter your lives or

the lives of your families and friends?’ The

children can then imagine their lives in 10 years’

time and answer the same questions. Finally

they can imagine that they are parents and have

children aged 13. What advice would they give

them?

Children can:

•

•

Play a true/false’ game. The teacher writes down

true or false statements about AIDS on separate

pieces of paper, e.g.: ‘You can catch the AIDS

virus from mosquitoes’ (false); ‘You can’t catch

the AIDS virus by shaking hands’ (true). On the

floor mark three areas - ‘TRUE’, ‘FALSE’ and

‘DON'T KNOW

*.

Each child takes one statement,

puts it on one of the three areas and explains the

reason for their choice. Anyone else can challenge

the decision.

•

Make a role play about different married couples

and how they treat each other. Which are the

happiest marriages?

•

Where possible, find out from newspapers or

government health departments the number of

AIDS cases in the country. Work out the

percentage of the total population this figure

represents.

Discuss situations when it is sometimes difficult

to say ‘No’ and list the reasons. In pairs, children

can role play different situations, imagine how

people might try to persuade them to do something

and how they could say, ‘No’ in a way which is

polite but firm, e.g. when asked:

to have a cigarette;

to go somewhere with a stranger;

to go out for the evening.

•

Visit a local health centre. Health workers can

talk about why they give injections and

demonstrate how needles and syringes are

sterilised.

Find out what guidance their religious books give

on sexual practices.

DISCUSSION AND ROLE PLAY ABOUT

ATTITUDES TO PEOPLE WHO HAVE AIDS

Write quiz questions about AIDS and discuss the

answers in pairs.

FINDING OUT ACTIVITIES

Children can:

•

•

DISCUSSION AND ROLE PLAY ABOUT

AVOIDING AIDS

Children can:

•

Imagine how AIDS might affect their lives. They

can shut their eyes and imagine their lives in two

Children can:

•

Collect newspaper cuttings concerning AIDS and

discuss the attitudes the articles suggest.

•

Write poems expressing their feelings about AIDS

and its effect upon their own or other people’s

lives.

•

Use pictures, e.g. of someone caring for a friend

with AIDS, to help them to imagine how they

would feel in the role of one person in the picture.

They can ask questions about what events led to

the scene shown and what might happen in the

future.

•

Create short plays, for example about caring at

home for a person with AIDS. They can first act

the play themselves, then each make a simple

puppet for their character and perform the play

with puppets to the rest of the school or the

community.

•

Collect and discuss stories from religious books

of people caring for the sick.

•

Fill in the details of a story, for example about an

imaginary school pupil thought to have AIDS.

The children divide into groups representing, in

this example, the pupil, other pupils, teachers

and parents. Each group separately considers:

*What do I feel?’, ‘What are the main effects on

me?**, and ’What do I want to happen?’. After 15

minutes the groups reassemble and share their

discussions.

•

PASSING ON THE MESSAGE

Children can:

•

make up and perform songs, plays and puppet

shows about AIDS;

•

design and make posters to display in class and

on open days;

•

join in the promotion of sports for better health of

people with AIDS.

Listen to the following stories:

A young woman returns to her village

from a neighbouring city. As she walks

across the square people shout at her

“AIDS! AIDS!” Her stepfather insists that

she gets an AIDS test before she lives in

the family home. The test is positive. ’

FOLLOW-UP

Teachers can:

•

A group of politicians see a video showing

a person dying of AIDS and make a policy

that everyone should be tested and those

carrying the virus should be locked up.’

ask children different questions to find out if they

know:

what spreads AIDS;

what does not spread AIDS.

•

ask children to write stories:

about people catching the AIDS virus;

about caring for people with AIDS.

Then look at the stories. What do they tell us

about children’s knowledge and about their

attitudes?

‘The colleagues of a woman whose

husband has AIDS refuse to work with her.

She is sacked.’

•

ask children to find out how many local schools or

youth groups have clubs and activities which look

at AIDS. What do they do? Have the children

joined them?

•

find out if children have:

Then try to answer these questions:

•

•

•

•

What do you think about these situations?

Why do people react in these ways?

Will these reactions help to control the spread of

AIDS?

What would you do If you were any of the

characters in these stories?

taken part in anti-AIDS campaigns;

helped anyone with AIDS;

warned other children about the risks of AIDS.

CHILD-TO-CHILD PUBLICATIONS

Available through

TALC (TEACHING-AIDS AT LOW COST)

DECEMBER 1993

ENGLISH

1.

Sample pack of Child-to-Child Activity Sheets

Free

2.

Complete pack of Child-to-Child Activity Sheets

£2.00

3.

Child-to-Child and Disability (2 Readers and 14 Activity Sheets concerning disability)

£4.20

4.

Child-to-Child Readers:

Dirty Water (level 1)

Accidents (level 1)

Not Just a Cold (level 1)

A Simple Cure (level 2)

Teaching Thomas (level 2)

Down with Fever (level 2)

Diseases Defeated (level 2)

Flies (level 2)

I Can Do It Too (level 2)

Deadly Habits (level 3)

£1.30

£1.30

£1.30

£1.45

£1.45

£1.45

£1.45

£1.45

£1.45

£1.45

5.

Health into Mathematics: William Gibbs and Peter Mutunga. The first in the Health Across the

Curriculum series, this volume teaches many basic concepts of mathematics while making them

relevant to everyday life by using health examples.

£4.50

6.

Primary Health Education: Beverley Young and Susan Durston. This successful and extremely

popular volume has been used by primary school teachers worldwide to help with health education

in schools.

£5.50

7.

Toys for Fun: June Carlile (Ed). A book of toys for pre-school children with multi-lingual text

(English. Arabic. French, Portuguese, Spanish and Swahili all in one volume).

£2.00

8.

Children, Health and Science: Hugh Hawes, John Nicholson and Grazyna Bonati. This book,

designed for science teachers in primary and secondary schools, contains an introduction and 20

specially selected Child-to-Child activity sheets. Certain groups can receive bulk orders free.

(French and Spanish versions are available directly from Unesco. Paris.)

£1.00

9.

Child-to-Child: A Resource Book: Grazyna Bonati and Hugh Hawes (Ed). This contains most

Child-to-Child activity sheets, sections on methodology, evaluation and running workshops, and

examples of action taken from round the world.

*

£5.00

10.

Education for Health in Schools and Teachers’ Colleges: This contains guidelines for the

introduction of Child-to-Child approaches in primary schools, teachers’ colleges and the curriculum.

based on experience from projects over many years.

£2.00

11.

We are on the Radio (book plus tape): Clare Hanbury and Sara McCrum. Introduces basic broad

casting techniques and skills for those who want to involve children in making effective broadcasts

about health.

£3.50

12.

Child-to-Child and Children Living in Camps: Clare Hanbury (Ed). Written for people working

with children in refugee camps or camps for displaced people, this volume contains specially adapted

Child-to-Child materials plus a section on these children’s special needs.

£2.50

13.

Children for Health: Hugh Hawes and Christine Scotchmer (Ed.) This book contains all the

messages in the 1993 version of Facts for Life together with sections to help children understand the

health ideas and act upon them both in and out of school. 25% discount available on orders of 100 or

more copies.

£2.00

Special price for overseas.

’

SPANISH

1.

Child-to-Child Activity Sheets

2.

Spanish versions of the Child-to-Child Readers:

*

£2.00

£1

Accidentes

£1

\gua Sucia

£1

Buena Alimentation

£1

Enseriandole a Tomas

£1

Un Remedio Sencillo

£1

8 8 8 8 8 8

A Bajar la Fiebre

Please send your orders with payment to TALC, P.O. Box 49, St Albans, Herts AL1 4AX, U.K. (Tel. (0727) 853869;

fax: (0727) 846852). Add 30% to the total cost of the books for surface or U.K. mail (minimum £2.00) OR 60% for

airmail (minimum £2.50).

Available from ARC, PO Box 7380, Nicosia, Cyprus:

ARABIC

Adaptations of Child-to-Child Readers:

Dirty Water

Teaching Thomas

I Can Do It Too

Diseases Defeated

Down with Fever

A Simple Cure

Good Food

Flies

Available from EDICEF, 26 rue des Fosses Saint-Jacques, 75005 Paris, France:

FRENCH

Child-to-Child Readers:

La Fievre du Lion (Le coup de chateur)

Le Vieux Roi et la Petite Fiancee (L’alimentation des bebes)

L’Hyene aux Yeux de Poulet (La vitamine A)

Halte aux Maladies! (Les vaccinations)

Fati n’est plus Triste (Les enfants handicap's)

La Revanche de Sonko-le-Ltevre (L’hygiene des puits)

Mon Petit Frere est Malade (La diarrhee)

Surveillons les Petits (Les accidents)

La Pernique Rouge de Bouki (Les poux)

Le Jeune Homme et le Dragon (Les vers)

Available from the Child-to-Child Trust, Institute of Education, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL, U.K.:

A set of 4 Activity Sheets Helping Children in Difficult Circumstances:

Children who Live or Work on the Street

Children who Live in an Institution

Helping Children whose Friends or Relatives Die

Helping Children who Experience War or Disaster

Christian Responses to AIDS

A Bibliography

Caritas Internationalis: El SEDA. Un Desafio a la Iglesia.

Memoria del Coloquio de Santo Domingo, Iglesia y Enfermos de SIDA, Enero 7 al 12, 1990.

Secretariado Latinoamericano de Caritas (SELAC), Apartado Postal 1703 1389, Quito Ecuador.

Catholic Health Associaton of the United States (ed.): The Gospel Alive. Caring for

Persons with AIDS and Related Illnesses.

(1988). Catholic Health Association of the United States, 4455 Woodson Road, St. Louis, MO

63134-0889/ USA. ISBN 0-87125-149-3.

This book addresses AIDS in relation to the special opportunity it provides all of us, as Church, to herald

Christ's message and care for others.

Cosstick, V.: AIDS. Meeting the Community Challenge.

(1987). St. Paul Publications, Middlegreen, Slough SL3 6BT/ United Kingdom. ISBN

0-85439-264-5.

This book brings together the precious experience ofprofessionals and concerned laity, of religious leaders,

priests and religious. And it makes abundantly clear that the solution to the moral problem which lies behind

the questions ofpublic health is not to be found in declarations by experts but in the perceptions and

spiritual renewal ofthe whole people ofGod.

Cullen, T.: AIDS. A Christian Response.

(1991).Montfort Missionaries, P.O.Box 280, Balaka, Malawi.

This pastoral book aims at improving our understanding of the AIDS disease by presenting it from four

different angles: the Spritual, Psychological, Moral and Cultural viewpoints. The book does not offer an

exhaustive analysis ofall these aspects; only a few are selected and reflected upon. The writers come from

different Christian denominations and they are concerned to present a Christian response to the present

AIDS crisis in Malawi.

Dorr, D.: Integral Spirituality. Resources for Community, Justice, Peace, and the Earth.

(1990).Gill and Macmillian Ltd., Goldenbridge, Dublin 8/ Ireland. ISBN 07171-1730-8.

Throughout the book there are guided meditations and other resource materials which can be used by groups

or individuals to put the spirituality into practice. Beginning with a study of "down-to-earth-spirituality"

which enables one to be "rooted" or "grounded", the author goes on to show how personalprayer plays a key

role in spirituality.

Joinet, B.A.: The Challenge of AIDS. Vol.l: Basic facts.; Vol.2: Prevention and

Survivors. (1992).Fr. Bernhard Joinet, W.F., P.O.Box 280, Dar es Salaam/ Tanzania.

These two volumes will give educators and pastors the information they need to help people make their own

decisions when faced with the AIDS pandemic.

Kelly, R.(S.J.): Calming the Storm. Christian Reflections on AIDS.

Mission Press, P.O.Box, 71581 Ndola/Zambia.

This book invites usfirst to make sure that we have some understanding ofthis new disease, how it spreads

and how it can be prevented. Then we will reflect on what the AIDS crisis is saying to us as people and as

Christians about modem society and the way we live and the values that influence our life-style.

Kirkpatrick, B.: AIDS. Sharing the Pain. A Guide for Caregivers.

(1990). Pilgrim Press, 475 Riverside Dr., New York, N.Y. 10115/ USA. ISBN

0-8298-0827-2.

The author offers practical and sensitive guidelines for the care of those infected by HIV. He explores the

pain and difficulties ofthose who are going through the various stages ofAIDSfrom initial to full-blown

AIDS.

MAP International (Ed.): The Church's Response to the Challenge of AIDS/HIV. A

Guideline for Education and Policy Development.

(1991). MAP International, P.O.Box 50, Brunswick, GA 31521-0050.

This document is not designed to be an exhaustive discussion of the issue, but rather a frameworkfor the

local church's approach to AIDS/HIV. It touches on the fears and the facts related to AIDS and HIV

infection, as well as ways to educate and involve a local congregation. Each local church will need to address

AIDS/HTV in its own specific community.

Me Cloughry,R., and C. Bebawi: AIDS: A Christian Response.

Grove Ethical Studies, No.64. (1990). Grove Books Ltd., Nottingham NG9 3 DS/ United

Kingdom.

In this small booklet there are two parallel lines ofthought. The first may be seen by some as pessimism about

the future. Even were it possible to find a vaccine for AIDS soon, many thousands ofpeople will still die. The

scale of the human tragedy to come is awesome, but farfrom bringing people to a new sense of their need of

God. The second arises out ofthe Christian calling to hope, faith and love and to enable those who may

otherwise choose despair to choose life.

Sandys, S.: Embracing the Mystery. Prayerful Responses to AIDS.

(1992). SPCK, Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone Road, London NW1 4DU/ United

Kingdom. ISBN 0-281-04574-7,

In this book there are prayers, readings and meditations - many ofthem written specially for this book - that

can be used by individuals or groups as part oftheir practical response to the tragedy ofHIV infection.

Tilleraas, P.: The Color of Light. Daily Meditations for All of us Living with AIDS.

Hazeldon Meditation Series. (1988). Hazeldon Press. Pleasent Valley Road, Box 176, Center

City, MN 55012-0176, USA. ISBN 0- 89486-511-0.

This book offers hope and comfort as we struggle to cope with AIDS in our lives and in our society. Here is

daily guidance on moving from isolation toward loving support, rediscovering spiritual rewards, and

reaching out with love and wisdom.

<

htlcrnnlioiinl {ouriml of STD & AIDS 1992; 3: 79-86

/A / ■

1/lJ W

EDITORIAL REVIEW

HIV and pregnancy

Frank D Johnstone MD FRCOG

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh/Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion, and Department of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Edinburgh, Centre for Reproductive Biology,

Edinburgh, UK

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, pregnancy, baby, transmission

In the United States and Europe, the number of

women with AIDS is increasing rapidly, both in

absolute terms and as a ratio to men1'2. Thus in the

55% of all AIDS cases in women in the

epidemic's first decade have occurred within the last

two years3. Although injection drug use was the

predominant mode of transmission initially, hetero

sexual transmission is becoming the dominant

route3, with all the potential this involves for much

wider dissemination. In a Paris study, 20% of

infections in women were attributed to heterosexual

intercourse in 19874. In 1989 the proportion was

58% and increasing.

In Africa, the scale of the problem and the

potentially devastating consequences of maternal

and childhood infection with HIV have long been

recognized5. New worries surround reported

increases in prevalence in South America6,

Thailand7 and India8.

In addition to the particularly harrowing problem

of children becoming ill and losing parents^ there

^^many unresolved scientific questions concerning

W-ie, timing and prevention of vertical transmission.

All these features combine to project pregnancy to

the forefront of current concern in HIV infection.

In this necessarily limited review I will leave aside

important issues such as testing and screening for

HIV in pregnancy9-11 and clinical management12-14.

Instead, I will restrict discussion to three areas

which are contentious, but of intense research and

clinical interest; the effect pregnancy has on HIV

disease progression; the effect HIV has on

pregnancy outcome; and vertical transmission.

EFFECTS OF PREGNANCY ON HIV DISEASE

Pregnancy is believed to be associated with a mild

impairment of the immune system, together with

an increased virulence of some infections. This has

fuelled concern that pregnancy may exacerbate the

progression of HIV disease.

Correspondence to: Dr F D Johnstone, Senior Lecturer,

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, University of Edinburgh,

Centre for Reproductive Biology, 37 Chalmers Street, Edinburgh

EH3 9EW, UK

Pregnancy and susceptibility to infectious disease

The evidence for a decline in immune response in

pregnancy is conflicting. There is agreement that

antibody mediated immunity is unchanged, with no

alteration in B cell number15, satisfactory antibody

responses to vaccines in pregnancy16-18 and

unchanged or slightly increased complement

levels19'20. Most studies have found a reduction in

absolute T cell counts15'21-23 but this could simply be

a haemodilution effect, and there are differing reports

about a decrease in CD4 cells expressed as a

percentage of total lymphocytes or as a CD4/CD8

ratio22'23. T lymphocyte function does not appear

to be reduced23*24. Current opinion suggests that

systemic T cell function is maintained, but that there

is some depression of cell mediated immunity,

perhaps due to the raised levels of some steroid

hormones and/or plasma proteins in pregnancy25.

There are many studies which suggest increased

virulence of a number of infectious diseases in

pregnancy and these have been excellently

reviewed26-27. The methodology of many of these

studies has been criticized28 but the totality of

supporting evidence is impressive. Perhaps the best

example of increased susceptibility to infection is

falciparum malaria29 but there is also good evidence

of increased risk with hepatitis30-31, polio32-34>

influenza35'36 and general clinical recognition of

worsening of vulval papillomata26.

Progression of HIV disease

For the above reasons there have been persistent

concerns that pregnancy may adversely affect

progression of HIV disease. Initial reports tended to

confirm these concerns37'38. However, these studies

were based on identification of mothers of children

who had already developed AIDS, and who were

themselves at particularly high risk39.

Although several studies of the effect of pregnancy

on the natural history of HIV disease are in progress,

none have been reported in full. Two reports, one

from France40, the other from Haiti41, suggested

higher progression to CDCIV disease in women who

had completed a pregnancy compared to a non

pregnant control group. However, numbers were

SO

Inh*iIidlion.il lounidl et SID & AIDS Volume 3 March April IW?

small, and whether I he groups were comparable in

time since seroconversion is not known. Similar

studies from New York42, Bethesda'13, and Genoa1'1,

did not document any adverse clinical effect of

pregnancy on the progression of HIV.

A number of studies have examined prognostic

markers which may be taken as surrogates for

clinical progression. In Edinburgh, follow up of

152 women enrolled since 1985 has not shown

women who had a pregnancy to be disadvantaged

(compared with non-pregnant HIV infected women)

in terms of clinical, virological, or immunological

progression45 (and unpublished data). Similar

conclusions have been reached by Berrebi et al.46

from Toulouse, France.

The type of analysis used in all the above studies

has implicit methodological problems of ensuring

comparability of disease status between groups.

Indeed, systematic bias could occur if iller women

deliberately avoided pregnancy; if non-pregnant

drug users were more likely to continue to inject47;

or if the non-pregnant group were significantly

older. Another, and perhaps preferable, method is

to study the effect pregnancy has on each woman's

slope of fall in CD4 lymphocyte count with time.

She will thus be her own control, in terms of CD4

decline before and after pregnancy. An attempt to

do this was made by Biggar et al.48. The authors

believed their data were compatible with the

hypothesis that pregnancy may mildly accelerate

HIV induced depletion of CD4 lymphocytes, and

could therefore increase the rate of progression.

However, they had.no non-pregnant HIV sero

positive control group, and this conclusion does not

seem justified.

In short, conclusive evidence about the effect of

pregnancy on longer term progression of HIV

disease is lacking. Available studies have small

numbers, relatively short follow up, and methodo

logical problems. However, it seems unlikely

that pregnancy has any major adverse effect on

asymptomatic women.

AIDS in pregnancy

There are other possible ways in which pregnancy

could affect disease. In susceptible, immuno

compromised women, the additional pregnancyinduced fall could reduce CD4 lymphocyte count

below the threshold for opportunistic disease.

Pregnancy could also increase the probability of an

AIDS defining illness being fatal, or affect longer

term prognosis after a CDC 4CI defining event.

Published case reports suggest that the outcome

of AIDS in pregnancy is poor. In the United States,

the first 6 reported cases of Pneumocystis carinii

pneumonia (PCP) were fatal49"51 as was a case of

listeria bacteraemia where AIDS was assumed52.

Further reports of pregnancy-associated deaths from

AIDS have followed53-55.

In contrast to this? as late as 1990, Hicks et al.56

described a single case of a woman who developed

PCP during pregnancy but survived (his initial

episode. The authors claimed this was the first

reported case of survival from PCP in pregnancy.

This bias to mortality is strikingly different from

the situation in non-pregnant women. However, the

gloomy outlook may simply represent reporting

bias. Thus survival from PCP in pregnancy has been

reported by others57. Physicians are more likely to

report fatal cases, and perhaps journal editors are

more likely to publish such reports. Nothing is

known of non-fatal AIDS defining illness in the

population from which these women are drawn,

and there is no satisfactory information about

survival time after AIDS in pregnancy.

The only series which addresses these issues,

and has the advantage of being based on a total

geographical population, is from Edinburgh58.

Numbers are too small to provide reliable data, with

only 22 women with AIDS, four of whom were

pregnant. However, all three women who had PCP

for the first time in pregnancy survived this initial

episode, and survival time was not obviously

reduced by the conjunction of AIDS and pregnancy.

Whether the onset of AIDS in pregnancy does

carry a worse prognosis is not known. Because it

remains an uncommon event in the developed

world, and because the issue has not been

specifically studied in Africa, it will be some time

before this becomes clear.

EFFECT OF HIV INFECTION

ON PREGNANCY OUTCOME

There are several theoretical ways in which HIV

infection might affect pregnancy outcome59.

Abortion

Several studies have found an association between

HIV seropositivity and a history of spontaneous

abortion6®-62 but these studies have the problem

that the woman's HIV status during that pregnancy

was unknown. A case control study in Nairobi

showed HIV infection to be more common in

women admitted with a spontaneous abortion,

but the difference with control women whose

pregnancy was continuing was not statistically

significant63. A small prospective study64 did not

show an increase in spontaneous abortion. It is,

therefore, uncertain at present whether HIV is

directly associated.

Several studies have shown a higher HIV sero

prevalence in women having induced abortion than

in those continuing pregnancy65*66 and it might be

expected that women infected with HIV would

accept termination of pregnancy readily. Thus, 80%

of pregnant women in France67 and 83% of young

women in New York68 were in favour of abortion

for HIV infected women. Women actually infected,

behave differently however.

Studies from New York69 and Edinburgh70 have

not shown termination of pregnancy to be chosen

luhii.sienv

more commonly bv 11IV seropositive women

compared Io 111V seronegative drug using controls.

Eighty-five per cent ol women who tested HIV sero

positive were estimated in a survey of major obstetric

clinical centres to continue their pregnancy71.

Some of the reasons which underlie decision

making about pregnancy were discussed bv

Selwyn69. However, local perception of illness and

death due to HIV may influence choice, and in

Edinburgh, seropositive women now seek termi

nation of pregnancy significantly more often than

controls.

Powerful factors motivate an asymptomatic infected

woman to continue pregnancy, and counselling

must be sensitive to the extremely difficult issues

considered by her in making her decision.

Pregnancy complications K

Aarly studies reported a high incidence of pre-term

labour, caesarean section, syphylis and low birth

weight72-75. These studies were uncontrolled and

illicit drug use and poverty are known to be

associated with both HIV infection and poor

pregnancy outcome.

The first controlled study, in Edinburgh women,

most of whom had a history of drug use, showed

both case and control groups to have a high

incidence of pre-term labour, intrauterine growth

retardation, and low birth weight. However, there

were no differences according to HIV status74.

A prospective study of methadone clinic attenders

in New York64 did not show differences in

pregnancy complications and outcome, and nor did

a larger study from New York75. Similar findings

were reported from Milan76 and Toulouse77.

These data from the United States and Europe

^ontrast with much information from Africa. Several

wLrge studies from Zaire78-79, Congo80, Zambia81,

Kenya82, Uganda85 and Rwanda84-85 compared

pregnancy outcome in women who were, and were

not, infected with HIV. These studies include

1832 infected mothers and 3911 HIV seronegative

controls. HIV seropositivity was associated with;

pre-term delivery in some studies78"85 but not

others79-82-84-85; increased perinatal deaths in some

studies78-85-85 but no difference in others82-84. An

increase in chorioamnionitis in HIV positive

pregnancies was reported in one study78, bleeding

in the third trimester in another82, twinning in

another80. One large case control study from Kenya

focused on stillbirth and low birth weight86. Linear

logistic regression retained HIV status as a

significant association of these adverse outcomes

with odds ratios ranging from 2.0 to 2.9.

Although these reports on pregnancy compli

cations are somewhat inconsistent, all of the African

studies agree that birth weight is reduced in HIV

infected women. The difference from controls

ranges from 130 g84 to 232 g (calculated from ref 78).

There is evidence that decrease in fetal size at birth

is related to stage of maternal disease78. However,

11|\'.mJ prvgn.ui*y

S|

birth weight is unrelated to whether or not the baby

is itself infected'

Congenital abnormality is probably not more

common in HlV« infected women

*

5’. A dysmorphic

syndrome associated with 11IV was reported1’0-91

but subsequent reports have not confirmed this

finding92-95 and an HIV dysmorphic syndrome was

not seen in the large European Collaborative

Study89.

Reasons for the discrepancies between studies

The differences between African studies and those

from Europe and the United States may arise partly

from problems of methodology. Control groups in

the African studies are loosely matched and clearly

differ in other respects apart from HIV status. The

differences tend to be in a direction which would

favour the control groups as far as pregnancy

outcome is concerned. Attempts have been made

to allow for these differences using linear logistic

regression, but residual distinguishing features may

remain to confound the analysis.

There are other possible reasons for the dis

crepancies. The number of pregnancies studied in

Europe and the United States is very small in

comparison with the African studies and thus real

differences could be missed. In addition, the great

majority of women have been asymptomatic. In

contrast 18% of women had AIDS in one African

study78 while 53% and 17% were symptomatic in

others81-82. Finally, the difference in African popu

lations may be due to differential load of other

infectious diseases (particularly malaria) and to

differences in nutritional status. Basic data on

malarial parasites and maternal weight do not seem

to have been reported.

Conclusions

In asymptomatic women, HIV infection per se

may be associated with a modest reduction in birth

weight, but the effect on pregnancy appears to be

slight. Under African conditions, there may be

increased rates of spontaneous abortion, pre-term

labour and stillbirth. When a woman' becomes

clinically ill, it seems inevitable that there will be

a detrimental effect on pregnancy, and there is

evidence that this is so.

TRANSMISSION OF INFECTION TO THE BABY

Infection could be transmitted to the baby in utero,

at delivery, or by breast feeding. The relative

importance of these routes is still not certain,

although unlike other retroviruses breast feeding

does not seem to be the major mode of spread. The

outlook for infected children seems poor with one

third becoming ill with HIV disease within the first

year of life89., Th ere may be a bimodal pattern of

disease in perinatally-acquired infection94.

M2

h.»< rn.i!:oii.il bnirn.ii ■ .1 s| D - ,.\!i;S

Volume 3

M.iu.lvApnl |V»2

Timing and inode of transmission

The mode of transmission is uncertain. hi vitro

studicsshow that trophoblast is readily infected by

HlV-lM- ’ though there is dispute about whether

this is by a pathway mediated by CD/'5-96. Lewis

ct al.'

* 7 apparently located HIV-1 antigen in villus

trophoblast derivatives, villus mesenchymal cells,

and embryonic blood cell precursors in tissues from

3 out of 3 8-week fetuses, and claimed that there is

therefore a cytological pathway for transmission

established by 8 weeks.

Several early studies suggested that transmission

of HIV could occur in utero5*-™'™. Subsequently,

successful culture of HIV-1 was reported from 4 out

of 14 second trimester fetuses1(x)-101 and HIV DNA

sequence could be detected using polymerase chain

reaction in 12 of 41 fetuses101'104. In all these

studies, precautions were taken to minimize the

possibility of maternal cell contamination, but it is

difficult to exclude this beyond all doubt. One study

which seems to have done this used a polymorphic

DNA sequence adjacent to the cystic fibrosis

locus105. These authors examined only fetuses

where the mother was heterozygous, and the fetus

homozygous, for this sequence. In 9 such fetuses,

the maternal specific allele could not be detected,

thus excluding maternal cell contamination, but

HIV-1 DNA sequences were detected in 8. This

seems a surorisinglv high rate of HIV detection in

the light of known figures for transmission to the

child, and raises the possibility that defective

fragments of DNA are being identified rather than

true infection.

Even though infection can be transmitted early in

intrauterine life, it is not clear whether this is the

common or usual timing. The very early onset of

clinical and immunological features in some infected

children is suggestive. However, the fetus could be

infected late in pregnanev, during delivery bv

exposure to maternal blood or cervical mucous, or

postnatally through breast feeding. This timing is

of critical importance because if infection is usually

around delivery, the risk might be reduced by

prophylaxis (for example with large amounts of

soluble CD4 or zidovudine). Unfortunately, though

this is such a key issue, many uncertainties remain.

The risk of vertical transmission

Early reports suggested a transmission rate of at

least 50% but were biased by the inclusion of

children who presented ill. Prospective studies have

suggested rates of 13-39%78-81 -s~-89-106. The largest

study reported is the European Collaborative

Study89. Of 419 children born 18 months or more

before analysis, 372 were of known infection status,

48 were infected (12.9%). A further 4 had repeatedly

positive viral cultures, even though they had cleared

maternal antibody. Some of the differences in these

studies can be attributed to methodological problems,

as was discussed in the paper from the European

Collaborative Study89. Thus some studies included

younger children who were ill, hence inflating the

numerator artificially. Others had a low follow-up

rate, and one used virus culture on cord blood as

an end point for infection. Nevertheless, it seems

likely that much of the variation in transmission is

genuine and is related to population differences.

These include particularly stage of HIV disease, but

may also include other infections, and breast feeding.

Factors influencing vertical transmission

These are becoming clearer. There are maternal

features, probably mainly reflecting high viral load.

Placental abnormality and fetal genotype may also

be relevant.

There are accumulating, and convincing, data that

transmission is particularly likely late in the course

of disease107, when the woman is severely immuno

compromised. A French study108 reported that 66%

of 15 women with CD4 count in pregnancy

< 150/cm3, 50% of 24 women with P24 antigenaemia,

and 78% of 14 women who displayed a high viral

replication rate of HIV in culture, transmitted

infection to their babies. The significance of a low

maternal CD4 lymphocyte count was confirmed by

others39-109 while a Nairobi study110 claimed that

transmission correlated with maternal viral load as

assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

In addition to late disease being a risk factor, there

is evidence that vertical transmission is also likely

in the first year after seroconversion39. This

presumably also represents a time of higher viral

load, before relative protection from broadly

neutralizing antibody.

There is a search for more specific markers to

identify those individuals most likely to transmit

infection. This would help in counselling about

pregnancy and termination and also could select out

pregnancies at sufficiently high risk to justify trials

of drug prophylaxis. The levels of antibody to

epitopes on the hypervariable V3 loop of viral

gp 120, or the MN primary neutralizing domain,

have been found by some workers to be predictive

of fetal infection106111. This has not been confirmed

by others112"117 and certainly infection does seem to

have occurred despite high maternal levels of

antibodies. Nsvami et al.Ub may be correct when

they suggest that any protective effect of antibodies

against gp 120 neutralizing epitopes is type specific

rather than group specific.

As well as maternal factors, there are suggestions

that placental damage may be associated with

an increased rate of transmission. There is an

association with chorioamnionitis 78. The finding of

a high transmission rate with maternal anaemia

(though it could simply be a reflection of HIV

disease activity) could result from malaria, which

preferentially infects the placenta118. In addition,

fetal genotype may be important. One study reported

that susceptibility to HIV infection was related to

genetic variation in HLA immune response genes119.

h’hnstenv.

Finally, what obstetric factors could influence

transmission? Invasive fetal procedures, (cordocentesis, scalp sampling, application of scalp electrodes

etc) could result in micro-inoculation of the fetus

with maternal blood and hence cause infection.

Interestingly, the only fetal sample with maternal

blood contamination in one study was the one

where earlier cordocentesis had been performed101.

Such procedures should therefore be avoided where

the mother is infected. The role of caesarean section

is unclear. In theory elective caesarean section could

be protective by minimizing time spent by the baby

exposed to cervical mucus and blood from cervical

dilatation. A study of twins discordant for HIV

transmission could give support to this120. Of 15

discordant twin sets the first twin was infected in

13 cases, the second in only 2 (P = 0.01). Infection

of the baby has certainly occurred despite caesarean

^^ection being performed72'87'88'1061121. However,

wPaost studies do not clearly distinguish between

elective caesarean section, with intact membranes,

and caesarean section done after many hours in

labour with ruptured membranes, where it would

not be expected to be protective.

At present caesarean section should be performed

for standard obstetric reasons only, but this advice

may have to be revised as more evidence

accumulates.

The situation with zidovudine is unclear. In

the few cases reported so far, there have not been

major problems with use during pregnancy122'123.

However, infection of the infant has been

documented despite zidovudine treatment

throughout pregnancy124*125.

Breast feeding

^Dther retroviruses, such as Moloney murine

leukaemia virus126 or HTLV I in the human127 are

spread principally by breast feeding. HIV-1 occurs

in breast milk128 and there is no doubt that

infection has been transmitted to the baby postnatally by women infected by blood transfused for

post partum haemorrhage129"131. In addition, an

African study showed that 53% of women who were

seronegative at birth but who later seroconverted,

infected their babies132. In these situations, before

the development of neutralizing antibody, viral load

may be very high, and this may not parallel the

situation with an already infected woman. However,

one European study has reported significantly

higher infection rates in breast fed babies88.

It seems probable that breast feeding carries a risk

of infecting an otherwise non-infected baby. This

extra risk is probably small, and current belief is that

breast feeding is not a major route of transmission.

The avoidance of breast feeding itself carries risks,

particularly in developing countries but also to a

lesser extent in the industrialized world. Advice

about breast feeding is therefore dependent on an

assessment of these different risks in the population.

Mathematical models of the event frequencies

IIIV and prvgn.mcv

S3

which have to be taken into account have been

suggested133. In general terms, HIV infected

women in developed countries should be advised

to bottle feed. In countries where formula milk is

not readily available, and where poor standards of

hygiene are used in constituting milk powder,

breast feeding should continue to be promoted, as

offering infants the optimum chances for survival.

Conclusions

Progress is being made in several aspects of the

interaction between HIV and pregnancy. However,

many uncertainties remain. In particular, the timing

and mechanisms of vertical transmission are criticallv

important but poorly understood, and there is so

far no effective way of interrupting transmission to

the baby.

There is no reliable way of predicting early in

pregnancy which woman will transmit infection,

and no fully established method of early diagnosis

of infection status in the infant. The only certainty

about HIV and pregnancy is that the problem will

not disappear in the near future.

References

1 Centre for Disease Control: Update: Acquired immuno

deficiency syndrome—United States 1981-1990. M.MWR

1991;40:358-63

2 WHO Collaborating Centre on Aids—AIDS surveillance in

Europe Quarterly Report No. 24: 1989 December (Paris WHO)

3 Berkelman R, Fleming P, Chu S, Hanson D. Women and

AIDS: the increasing role of heterosexual transmission in the

United States. Vllth International Conference on /\IDS

1991—Florence, Abst. No WC 102

4 Henrion R, Henrion-Geant E. Mandelbrot L, et al. Trends

in HIV transmission in pregnancy. Lancet 1990;i: 1401(letter)

5 Piot P, Plummer F, Mhalu F, et al. AIDS: An international

perspective. Science 1988;239:573-9

6 Duart G, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Feres MC, et al. The ascendent

pattern of seropositivity for HIV antibody and the risk factors

associated to the HIV transmission in parturients cared at

a school hospital in Brazil. Vllth International Conference

on AIDS-Florence, 1991 Abst. No. WC 3257

7 Ung Chusak K, Thanprasertsuk S, Vichai C, et al. Trends

of HIV spreading in Thailand detected by National Sentinel

Surveillance. Vllth International Conference on AIDSFlorence, 1991 Abst. No. MC 3246

8 Kandaswami J, Ravinathan R, Padmarajan S, et al. Seroepidemiological study of HIV infection in two major centres

of South India. Vllth International Conference on AIDSFlorence, 1991 Abst. No. MC 3302

9 Johnstone FD. Ante-natal screening for HIV—review and case

for anonymysed unlinked studies. In: Templeton AA,

Cusine D, eds. Reproductive medicine and the law. Edinburgh:

Churchill Livingstone, 1990:123-39

10 Holman S, Sunderland A, Berthaud M, et al. Prenatal HIV

counselling and testing. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1989;32:445-55

11 Gillon R. Testing for HIV without permission. BM]

1987;294:821-3

12 Minkoff HL. AIDS in pregnancy. Curr Probl Obstet Gynecol

Fertil 1989;12:205-28

13 Johnstone FD. HIV infection in pregnancy. Curr Obstet

Gynecol 1991;1:78-83

J4

IT

|n‘ern.iti«<n.il Journal <>i STD

AIDS

Volume 3

M.irch/Apnl 1992

MacGregor SN. I Inman immunodeficiency virus infection

in pregnancy. Clin Perinatal 1991;18:33-50

15 Sridama V, Pacini F, Yang SI., Muawad A, Reilly M, De Groot

LJ. Decreased levels of helper T-cells—a possible cause of

immunodeficiency in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1982;307:352-6

16 Carvalho AA, Giampaglia CMS, Kimura H, et al. Maternal

and infant antibody response to meningococcal vaccination

in pregnancy. hiucet 1977;ii:8G9-I1

17 Sumaya CV, Gibbs RS. Immunization of pregnant women

with influenza A/New Jersey'76 virus vaccine: reactogenicity

and immunogenicity in mother and infant. I Infect Dis

1979;140:141-6

18 Brabin BJ, Nagel I, Hagenaars AM, et al The influence of malaria

and gestation on the immune response to one and two doses of

adsorbed tetanus toxoid in pregnancy. Bull WHO 1984;62:919-30

19 Johnson U, Guslavii B. Complement components in normal

pregnancy. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand 19S7;95c:97-9

20 Kovar IZ, Riches PG. C3 and C. complement components

and acute phase proteins in late pregnancy and parturition.

J Clin Pathol 1988,41.650-2

21 Castilla JA, Rueda R, Vargas ML, Gonzalez-Gomez F,

Garcia-Olivares E. Decreased levels of circulating CD, + T

lymphocytes during normal human pregnancy I Reprod

Immunol 1989;15:103-11

22 Tallon DF, Corcoran AJ, O'Dwyer EM, et al. Circulating

lymphocyte sub-populations in pregnancy: A longitudinal

study. / Immunol 1984;132:1784-87

23 Bailey K, Herrod HG, Younger R. et al. Functional aspects

of T-lymphocyte sub-sets in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol

1985;66:211-15

24 Hawes CS, Kemp AS, Jones WR, et al. A longitudinal study

of cell-mediated immunity. / Reprod Immunol 1981;3:165-73

25 Weinberg ED. Pregnancy associated immune suppression:

risks and mechanisms. Microbiol Pathogenesis 1987;3:393-7

26 Weinberg ED. Pregnancy-associated depression of cellmediated immunity. Rev Infect Dis 1984;6:814-31

27 Brabin BJ. Epidemiology of infection in pregnancy. Rev Infect

Dis 1985;7:579-603

28 Falkoff R. Maternal immunologic changes during pregnancy:

a critical appraisal. Clin Rev Allergy 1987;5:287-300

29 Brabin BJ. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull

WHO 1983;61:1005-16

30 Khuroo MS, Teli MR. Skidmore S, et al. Incidence and

severity' of viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Am J Med 1981;70:252-5

31 Borhanmanesh F, Haghighi P, Hekmat K, et al. Viral hepatitis

during pregnancy. Gastroenterology 1973;64:304-13

32 Weinstein L, Aycock WL, Feemster RF. The relation of sex,

pregnancy and menstruation to susceptibility in poliomyelitis.

N Eng / Med 1951;245:54-8

33 Priddle HD, Lenz WR, Young DC, et al. Poliomyelitis in

pregnancy and the puerperium. Am / Obstet Gynecol

1952;63:408-13

34 Siegel M, Greenberg M. Incidence of poliomyelitis in

pregnancy. N Engl / Med 1955;253:841-7

35 Freeman DW, Barno A. Deaths from Asian influenza

associated with pregnancy. Am I Obstet Gynecol 1959;78:1172-5

36 Greenberg M, Jacobziner H, Pakter J, et al. Maternal mortality

in the epidemic of Asian influenza. New York City, 1957.

Am ] Obstet Gynecol 1958;76:897-902

37 Scott GB, Fischl MA, Klimas N, et al. Mothers of infants with

the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Evidence for both

symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers. JAMA 1985;253:363-6

38 Minkoff HL, Nanda D, Menez R. etal. Follow-up of mothers

of children with AIDS. Obstet Gynecol 1987;87:288-91

39 Hague RA, Mok JYQ, MacCallum L, et al. Do maternal factors

influence the risk of vertical transmission of HIV? Vllth

International Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991:

Abstract WC3237

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

Delfraissey |F, Pons JC, Sercni D, et id. Docs pregnancy

influence disease progression in HIV positive women. Vth

International Conference on AIDS, June 1989, Montreal,

Canada Abstract MBP 34

Deschamps M-M, Pape JW, Madhavan S, et al. Pregnancy and

acceleration of HIV related illness. Vth International Conference

on AIDS, June 1989, Montreal, Canada. Abstract MBP 6

Schoenbaum EE, Daverny K, Selwyn PA, et al. The effect

of pregnancy on progression of IIIV related disease. Vth

International Conference on AIDS, June 1989, Montreal,

Canada Abstract MBP 8

Bledsoe K, Olopoenia L, Barnes S, et al. Effect of pregnancy

on progression of HIV infection. Vlth International Conference

on AIDS, June 1990, San Francisco, USA. Abstract ThC 652

Mazz.arello G, Canessa A, Melica F, et al. Influence of

pregnancy on HIV disease progression. VII International

Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991. Abstract WC3235

MacCallum LR, Cowan FM, Whitelaw J, et al. Disease

progression following pregnancy in HIV seropositive women.

Vth International Conference on AIDS, June 1989, Montreal,

Canada. Abstract MBP 3

Berrebi A, Puel J, Tricoire J, et al. Influence of gestation on

HIV infection. Vlth International Conference on ?\IDS, June

1990, San Francisco, USA. Abstract ThC 651

Des Jarlais D, Friedman SR, Marmor M, et al. Development

of AIDS, HIV seroconversion, and potential co-factors for

T. cell loss in a cohort of intravenous drug users. AIDS I

1987:105-11

Biggar RJ, Pahwa S, Minkoff H, et al. Immunosuppression

in pregnant women infected with HIV. Am / Obstet Gynecol

1989;161:1239-44

Jensen LP, O'Sullivan MJ, Gomez-Del-Rio M, et al. Acquired

immunodeficiency (AIDS) in pregnancy. Am / Obstet Gynecol

1984;148:1145-6 '

Antoine C, Morris M, Douglas D. Maternal and fetal mortality

in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Y State / Med

1986;86:443-5

Minkoff H, de Regt RH, Landesman S, Schwarz R.

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia associated with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome in pregnancy: a report of three

maternal deaths. Obstet Gynecol 1986;67:284-7

Wetli CV, Roldan EO, Fujaco RM. Listeriosis as a cause of

maternal death: an obstetric complication of the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Am / Obstet Gynecol

1983;147:7-9

Kell PD, Barton SE, Smith DE, et al. A maternal death caused

by AIDS. Case Report. Br / Obstet Gynaecol 1991;98:725-7

La Pointe N, Michaud J, Pekovic D, et al. Transplacental

transmission of HTLV-III virus. N Engl J Med 1985;312:1325-6

Koonin LM, Ellerbrock TV, Atrash HK, et al. Pregnancyassociated deaths due to AIDS in the United States. JAMA

1989:261:1306-9

Hicks ML, Nolan GH, Maxwell SL, Mickle C. Acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome and Pneumocystis carinii

infection in a pregnant woman. Obstet Gynecol 1990;76:480-1

Minkoff HL, Willoughby A, Mendez H, et al. Serious

infections during pregnancy among women with advanced

human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1990; 162:30-4

Johnstone FD, Willox L, Brettle RP. Survival time after AIDS

in pregnancy.

Johnstone FD, HIV and pregnancy outcome. Bailliere Clin

Obstet Gynaecol 1991 (in press)

Lasley-Bibbs V, Renzullo P, Goldenbaum M, et al. Patterns

of pregnancy and reproductive morbidity among HIV

infected women in the US Army: a retrospective cohort

study. Vlth International Conference on AIDS, June 1990,

San Francisco, USA: Abstract Th.C 655

JiihnMuiiv

Miolti PG, Dallabvlta G. Wlo\ i E, if al. HIV-l and

pregnant women: associated tailors, prosalencc. estimate of

incidence and role in ictal wastage in central Africa. AIDS

1990;4:733-6

62 LePage P, Dabis F, I lilimana DG. el til. Perinatal transmission

of HIV-1: lack of impact ot maternal HIV inteclion on

characteristics of livebirths and on neonatal mortality in

Kigali, Rwanda AIDS 1991;5:295-300

63 Lopitn MI, Temmerman M. Sinei SKF, et til. HIV infection

as a risk factor for spontaneous first trimester abortion. Vlth

Internationa! Conference on AIDS, June l°90, San Francisco,

USA: Abstract Th.C 653

64 Selwyn PA, Schoenbaum EE, Davcnny K. et al. Prospective

study of human immunodeficiency virus infection and

pregnancy outcomes in intraxenus drug users. JAM A

1989;261:1289-94

65 Johnstone FD, MacCallum LR, Brettle RP, et al. Testing for

HIV in pregnancy: 3 years experience in Edinburgh City. Scott

Med J 1989,34:561-3

66 Emanuelli F, Ermigha ML, Gabutti G, et al. Human

I

immunodeficiency virus infection among women attending

F

obstetric and gynaecology departments in Liguria, Italy. VII

International Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991.

Abstract WC 3275

67 Moatti JP, Gales C, Seror V, et al. Social acceptability of HIV

screening among pregnant women. AIDS Care 1990;2:213-22

68 Balanon A, Fordyce EJ, Stoneburner R. AIDS concerns and

women's reproductive intentions: HTV testing and pregnancy

choices. Vlth International Conference on AIDS, June 1990,

San Francisco, USA: Abstract Th.D 804

69 Selwyn P.A, Carter RJ, Schoenbaum EE, ct al. Knowledge

of HIV antibody status and decision to continue or terminate

pregnancy among intravenous drug users. JAMA 1989;261:

3567-71

70 Johnstone FD, Brettle RP, MacCallum LR, et al. Women's

knowledge of their HIV antibody state its effect on their

decision whether to continue the pregnancy. BMJ 1990;

300:23-4

71 Stratton P, Mofenson L, Willoughby A, et al. Prenatal

screening policies for HIV antibody at major obstetric clinical

centers in the United States. Vlth International Conference

i

on AIDS, June 1990, San Francisco, USA: Abstract SC 665

72 Minkoff H, Nanda D, Menez R, Fikrig S. Pregnancies

resulting in infants with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

or AIDS related complex. Obstet Gynaecol 1989;69:285-7

73 Gloeb DJ, O'Sullivan MJ, Efantis J. Human immuno

deficiency virus infection in women 1. The effects of human

immunodeficiency virus on pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1988;159:756-61

74 Johnstone FD, MacCallum L, Brettle R, et al. Does infection

with HIV affect the outcome of pregnancy? BMJ 1988,296:467

75 Minkoff HL, Henderson C, Mendez H, et al. Pregnancy

outcomes among mothers infected with human immuno

deficiency virus and uninfected control subjects. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1990;163:1598-604

76 Semprini AE, Ravizza M, Bucceri A, ct al. Perinatal outcome

in HIV-infected pregnant women. Gynecol Obstet Invest

1990;30:15-18

77 Berrebi A, Lahlov M, Puel J, et al. Effects of HIV infection

on pregnancy. VII International Conference on AIDS,

Florence, June 1991. Abstract WB2042

78 Ryder RW, Nsa W, Hassig SE. el al. Perinatal transmission

of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to infants of

seropositive women in Zaire. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1637-42

79 Kamenga M, Manzila T, Behels F, et al. Maternal HIV

infection and other sexually transmitted diseases and low

birth weight in Zairian children. VII International Conference

on AIDS, Florence, June 1991. Abstract WC3244

bl

I !l\ ..mi pregnancy

8?

Lallcmanl M, 1 allemanl-LeC’ovur S, Cheynicr D, <7 al.

Mother-child transmission of IIIV-I and infant survival in

Brazzaville, Congo. A IDS F\Sl’;3 013-6

81 1 lira SK, Kamanga J, Bhat Gl, <7 al. Perinatal transmission

of HIV-1 in Zambia. BMJ 1°89:299:1250-2

82 Braddick MR, Krciss JK, Ernbrec IE. et al. Impact of maternal

HIV infection on obstetrical and early neonatal outcome.

AIDS 1990;4:1001-5

83 Guay L. Mmiro F, Ndugwa, et al Perinatal outcome in HIVinfected women in Uganda. VI International Conference on

AIDS, San Francisco, June 1990. Abstract ThC42

84 LePage P, Dabis F, Hitimana D-G, et al. Perinatal trans

mission of HIV-1: lack of impact ot maternal HIV infection

on characteristics of livebirths and on neonatal mortal it v in

Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS 1991;5:295-300

85 Bulterys M, Chao A, Kurawige IB, et al. Maternal HIV

infection and intrauterine growth: a prospective cohort

study in Butare, Rwanda. VII International Conference on

AIDS, Florence, June 1991. Abstract WC3234

86 Temmerman M, Plummer FA, Mirza NB, et al. Infection with

HIV as a risk factor for adverse obstetrical outcome. AIDS

1990;4:1087-93

87 Italian Multicentre Study. Epidemiology, clinical features,

and prognostic factors of paediatric HIV infection. Lancet

1988;ii:1043-5

88 Blanche S, Rouzioux C, Moscato M-L, et al. A prospective

study of infants born to women seropositive for human

immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med 1989,-320:

1643-8

89 European Collaborative Study. Children born to women

with HIV-1 infection: natural history and risk of trans

mission. Lancet 1991;337:253-8

90 Marion RW, Wiznia AA, Hutcheon G, Rubinstein A. Human

T-cell lymphotrophic virus IH (HTLV-HI) embryopathy: a new

dysmorphic syndrome associated with intrauterine HTLVIII infection. Am J Dis Child 1986;140:638-40

91 Marion RW, Wiznia AA, Hutcheon RG, Rubinstein A. Fetal

AIDS syndrome score. Correlation between severity of

dysmorphism and age at diagnosis of immunodeficiency.

Am J Dis Child 1987;141:429-31

92 Nicolas S. Is there an HIV associated facial dysmorphism?

Pcdiatr Ann 1988;5:353

93 Qazi QH, Sheikh TM, Fikrig S. Lack of evidence for

craniofacial dysmorphism in perinatal HIV infection. J

Pcdiatr 1988;112:7-11

94 Auger I, Thomas P, de Gruttola V, et al. Incubation periods

for paediatric AIDS patients. Nature 1988;336:575-7

95 Maury W, Potts BJ and Rabson AB. HIV-1 infection of first

trimester and term human placental tissue: a possible mode

of maternal-fetal transmission. J Infect Dis 1989;160:583-8

96 Zachar V, Noskov-Lauritsen N, Juhl C, et al. Susceptibility

of cultured human trophoblast to infection with human

immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol 1991;72:1253-60

97 Lewis SH, Reynolds-Kohler C, Fox HE, Nelson JA. HIV-1

in trophoblastic and villous Hofbauer cells, and haemato

logical precursors in eight-week fetuses. Lancet 1990;

335:565-8

98 Sprecher S, Soumenkoff G, Puissant F, Degueldre M.

Vertical transmission of HIV in 15 week fetus. Lancet

1986;ii:2S8-9

99 Jovaisas E, Koch MA, Schafer A, et al. LAV/HTLV HI in a

20 week fetus. Lancet 1985;ii:1129

100 Peutherer JF, Rebus S, Aw E, et al. Detection of HIV in the

fetus: A study of six cases. IV International Conference on

AIDS, Stockholm, June 1988; Abstract 7235

101 Mano H, Chermann J-C. Fetal human immunodeficiency

virus Type 1 infection of different organs in the second

trimester. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1991;7:83-8

80

<6

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

International Journal of STD & AIDS

Volume 3

March/April 1992

Siegel G, Schafer A, Unger M, cl al. HIV-1 in fetal organs

and in embryonic placenta of HIV-1 positive mothers. VI

International Conference on AIDS, San Francisco, June

1990, Abstract FB 445

Soeiro LR, Rashbaum WK, Rubinstein LA, et al. The

incidence of human fetal 111V-I infection as determined by

the presence of HIV-1 infection as determined by the

presence of HIV-l DNA in abortus tissues. VII International

Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991 Abstract VVC3250

Ehrnst A, Lindgren S, Dictor M, cl al. HIV in pregnant

women and their offspring: Evidence for late transmission.

Lancet 1991,338.203-7

Courgnaud V, Laure F, Brossard A, et al. Frequent and early

in ulero HIV-1 infection AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses

1991;7:337-41

Coeder: JJ, Mendez H, Drummond JE, et al. Mother-toinfant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type

1: association with prematurity or low anti-gp 120. Lancet

1989;ii:1351-4

D'Arminio M, Ravizza .A, Muggiasca M, et al. HIV infected

pregnant women: possible predictors of vertical trans

mission. VII International Conference in .AIDS, Florence,

June 1991. Abstract WC49

Boue F, Pons JC, Keros L, et al. Risk for HIV-1 perinatal

transmissions varies with the mother's stage of HIV

infection. VI International Conference on AIDS, San

Francisco, June 1990. .Abstract ThC44

St Louis ME, Kabagaho U, Brown C, et al. Maternal factors

associated with perinatal HIV transmission. VII International

Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991. Abstract MC 3027

KreissJ, Datta P, Willerford D, et al. Vertical transmission

of HIV in Nairobi: correlation with maternal viral burden.

VII International Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991.

Abstract MC3062

Rubinstein A, Calvelli T, Goldstein H, et al. Correlation of

maternofetal (abortus) HIV-1 transmission with high

affinity avidity antibodies to the primary neutralizing

domain (PND). VII International Conference on AIDS,

Florence, June 1991. Abstract MC3052

Attain JP, Mathews T, Coombs R, et al. Antibody to V3

loop peptide does not predict vertical transmission of HIV.

VII International Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991.

Abstract WC3263

Beyssen V, Meyohas MC, Gras G, et al. Neutralization titers

in sera from HIV-infected pregnant women, and their corre

lation with materno-fetal transmission. VII International

Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991. Abstract WA 1344

Shaffer N, Parekh BS, Pau CP, et al. Maternal antibodies

to V3 loop peptides of GP 120 are not associated with bulk

of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. VII International Conference

on AIDS, Florence, June 1991. Abstract WC48

Halsey NA, Markham R, Rossi P, et al. V3 loop peptide

antibodies in Haitian women and infant HIV-1 infections.

VII International Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 1991.

Abstract WA1311

Nsvami M, St Louis M, Geoge JR, et al. Low prevalence

in HIV-infected Zairian mothers of antibodies against GP

120 neutralizing epitopes of the MN HIV-1 isolate lack

of association with perinatal HIV transmission. VII

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

International Conference on AIDS, Florence, June 199L

Abstract MC 3065

Krasink.ski K, Cao Y-Z, Friedman KA, et al. Elevated

maternal total and neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibody does

not prevent perinatal HIV-1. VI International Conference

on AIDS, San Francisco, June 1990; Abstract fhC 45

Diro M, Beydoun SN. Malaria in pregnancy. South Med /

1982;75:959-62

Just J, Louie L, Abrams E, et al. Genetic risk factors for