MPH-CH 8TH DECEMBER TO FRIDAY 12THBDECEMBER 2025

Item

- Title

- MPH-CH 8TH DECEMBER TO FRIDAY 12THBDECEMBER 2025

- extracted text

-

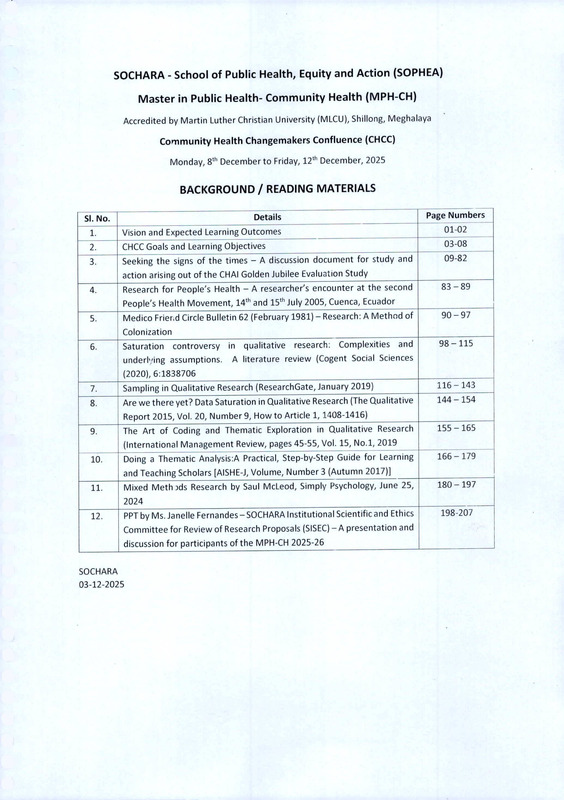

SOCHARA - School of Public Health, Equity and Action (SOPHEA)

Master in Public Health- Community Health (MPH-CH)

Accredited by Martin Luther Christian University (MLCU), Shillong, Meghalaya

Community Health Changemakers Confluence (CHCC)

Monday, 8th December to Friday, 12th December, 2025

BACKGROUND / READING MATERIALS

Page Numbers

Details

SI. No.

1.

Vision and Expected Learning Outcomes

01-02

2.

CHCC Goals and Learning Objectives

03-08

3.

Seeking the signs of the times - A discussion document for study and

09-82

action arising out of the CHAI Golden Jubilee Evaluation Study

4.

Research for People's Health - A researcher's encounter at the second

83-89

People's Health Movement, 14th and 15th July 2005, Cuenca, Ecuador

5.

Medico Friend Circle Bulletin 62 (February 1981) - Research: A Method of

90-97

Colonization

6.

Saturation

controversy

underlying assumptions.

in

qualitative

research:

Complexities

and

98-115

A literature review (Cogent Social Sciences

(2020), 6:1838706_________________________________ ____________

7.

Sampling in Qualitative Research (ResearchGate, January 2019)

116-143

8.

Are we there yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research (The Qualitative

144 -154

Report 2015, Vol. 20, Number 9, How to Article 1,1408-1416)

9.

The Art of Coding and Thematic Exploration in Qualitative Research

155-165

(International Management Review, pages 45-55, Vol. 15, No.l, 2019

10.

Doing a Thematic Analysis:A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning

166-179

and Teaching Scholars [AISHE-J, Volume, Number 3 (Autumn 2017)]

11.

Mixed Methods Research by Saul McLeod, Simply Psychology, June 25,

180-197

2024_________________________________________________________

12.

PPT by Ms. Janelle Fernandes-SOCHARA Institutional Scientific and Ethics

Committee for Review of Research Proposals (SISEC) - A presentation and

discussion for participants of the MPH-CH 2025-26

SOCHARA

03-12-2025

198-207

01

Soeharabuilding community health

Society for Community Health Awareness, Research and Action - SOCHARA

Registered under the Karnataka Societies Registration Act 17 of 1960, S.No. 44/91-92.

SOCHARA - School of Public Health, Equity and Action (SOPHEA)

Master in Public Health with specialisation in Community Health (MPH-CH)

Accredited by Martin Luther Christian University (MLCU), Shillong, Meghalaya

VISION AND EXPECTED LEARNING OUTCOMES

The MPH-CH builds on the community health approach that SOCHARA and other like

minded organisations have been working on for over four decades. This approach:

• builds on the societal paradigm of health and healthcare.

• explores alternative approaches to health and well-being which is rooted in

the community context and dynamics.

• encourages community action on social determinants of health.

• enables communities, practitioners and researchers to find sustainable solutions to

public health issues.

A community health approach builds on local capabilities, rational, safe and effective

health traditions, culture and context in a responsive, affirmative as well as challenging

manner.

The learning outcomes of the MPH-CH are to enable you:

• To be practitioners rooted in values of equity, rights, gender equality, ethics,

integrity, quality, accountability and responsibility at all levels in community

health and public health.

• To develop systems thinking, leadership, mentorship, ethical reasoning, problem

solving and implementation skills.

• To develop skills in qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research

including epidemiology and biostatistics.

• To strengthen interpersonal and rapport building skills for engagement and

partnership with communities, society and the state; across multiple sectors with a

special focus on the public health system.

• To develop skills for engaging with and strengthening an evidence-based Indian

public health system, plural healthcare (AYUSSH and others), health policy

processes, and for building community capacity, monitoring, evaluation and health

surveillance.

• To develop an understanding of public health priorities such as MCH, gender,

disability, communicable and non-communicable diseases, epidemics and pandemics,

climate change, disaster response, urban, rural and tribal health issues, emerging

concepts such as one health and planetary health.

• To develop the ability and skills to understand the micro and macro social

determinants of health, community contexts and develop community-based action

plans to address identified public health issues.

• To inculcate an understanding of determinants of health, together with approaches

and methodologies for health promotion (including prevention and protection)

using a community health approach.

• To develop capacities to initiate/strengthen community health action,

research, educational strategies, policy, dialogue and action.

• To develop an ability for life-long learning.

03

•? r

Socha

building community health

■J

*

-e

Q

Society for Community Health Awareness, Research and Action - SOCHARA

Registered under the Karnataka Societies Registration Act 17 of 1960, S.No. 44/91-92.

SOCHARA - School of Public Health, Equity and Action (SOPHEA)

Master in Public Health- Community Health (MPH-CH)

Accredited by Martin Luther Christian University (MLCU), Shillong, Meghalaya

Community Health Changemakers Confluence (CHCC)

Monday, 8th December to Friday, 12th December, 2025

CHCC Goals and Learning Objectives

Broad Goals

•

To participate actively in a research proposal development workshop

•

To further equip oneself with the necessary knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to become life-long

learners through study, research, action, reflection as Community Health and Public Health practitioners.

•

To revitalise one's commitment to working towards Health for All based on shared learning and life

experiences of fellow travellers in Community Health and Public Health.

•

To engage with a conversational methodology during the CHCC, actively sharing one's thoughts, and

utilising the opportunity to deepen one's inner learning.

Learning objectives

1.

2.

Core Objectives:

o

To develop a community health-oriented research study proposal for scientific and ethical

review. The research needs to be completed between November 2025 and July 2026.

o

To revisit and reflect on knowledge, skills, values and attitudes developed during the MPH-CH

course and to explore what lies ahead.

o

To develop an understanding of research and publication ethics in community health research and

action studies.

Secondary objectives:

o

To widen one's engagement in critical issues of current and future public health significance

through discussion and debate.

o

To strengthen the sense of 'community' and 'life-long learning' among participants for the

purpose of community health and public health.

o

To get to know each other better and to understand oneself through strengthening selfawareness and a practice of self-care.

04

PROVISIONAL AGENDA

DAY -1 MONDAY Sth December 2025

Core team reporter: Karun Puzhamudi

Participant moderator: To be assigned

Session name

Time

Facilitator

8.00 am to 8.45 am

9:15 am to 9.30 am

Registration

Venue

Breakfast

At accommodation

Maria, Precilia

Main Building, SOCHARA

Dr. Thelma Narayan, Director

of Academics

9.30 am to 10.00 am

Welcome,

introduction and

setting context

Ms. Prafulla S., Secretary-

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Coordinator

SOCHARA.

Programme Agenda

and Expected

Outcomes

10.00 am to 10.30 am

Dr. Thelma Narayan and Dr.

Archana S

Coffee / Tea Break

10.30 am to 11.00 am

Training Hall, SOCHARA and

Online via Zoom

SOCHARA premises

Ms. Janelie Fernandes - CHAI

Golden Jubilee Evaluation

Ms. Ranjitha L - Mitanin &

The SOCHARA

Research story

11.00 am to 1.00 pm

SHRC Evaluation

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Dr. Ravi D'Souza - Odisha

Health Policy & Health System

Reform

Lunch

1.00 pm to 2.00 pm

2:00 pm to 3:30p.m

Participants' Research

and life story

Participants

Coffee / Tea Break

3.30 pm to 3:45pm

SOCHARA premises

Training Hall, SOCHARA

SOCHARA premises

3:45 pm to 5:00 pm

Open session SOCHARA Team

SOCHARA team

Training Hall, SOCHARA

5:00pm to 5:30 pm

Concluding

Comments and

Announcements

SOPHEA team

Training Hall, SOCHARA

DAY 2 - TUESDAY 9th December 2025

Participant moderator:

team reporter: Ranjitha L

Core

of

Time

Facilitator

Session name

8.00 am to 8.45 am

9.15 am to 10.20 am

10:30 am to 11:30a.m

Discussion of

participants' research

topics

Literature review

workshop

(participants to come

with their individual

literature reviews and

Venue

Breakfast

At accommodation

Dr Thelma Narayan and Ms.

Janelle Fernandes

Training Hall, SOCHARA

SOPHEA team

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Q&As)

Coffee / Tea Break

11.30 am to 11.45 am

SOCHARA premises

11:45 am to 12.30 pm

Research story and

challenges

Dr. Upendra Bhojani, IPH,

Bengaluru

Training Hall, SOCHARA

12:30 pm to 1:00 pm

Alumni MPH-CH

Research Journey

Dr Nilesh Mohite

Online via Zoom

Lunch

SOCHARA premises

Dr. Upendra Bhojani, IPH,

Bengaluru and SOPHEA team

Training Hall, SOCHARA

1.00 pm to 2.00 pm

Developing a study

research question

and rationale

2.00 pm to 3:15pm

Workshop: Formulate

a Research question

Coffee / Tea Break

3.15 pm to 3.30pm

3:30 to 5:00 p.m

Workshop:

Literature review:

keywords and

structure

Develop research

objectives

Dr Hemanth, Janelle, Karun,

Ranjitha, Dr Ravi D'Souza and

participants

SOCHARA premises

Training Hall,

SOCHARA

U6

DAY 3 - WEDNESDAY 10th December 2025

Core team reporter:

Participant moderator:

Session name

Time

Facilitator

8.00 am to 8.45 am

Venue

Breakfast

At accommodation

9:15 am to 9:30 am

Recap

Ms. Janelie Fernandes

Training Hall, SOCHARA

9.30 am to 11:00 am

Quantitative research

Dr. Archana S (SOPHEA team

member)

Training Hall, SOCHARA

11.15 am to 11.30 am

11.30 am to 1.00 pm

Coffee / Tea Break

Quantitative research

1.00 pm to 2.00 pm

SOCHARA premises

Dr. Rahul ASGR

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Lunch

SOCHARA premises

Identifying an

appropriate research

design for your

research question

SOCHARA team

2.00 pm to 3.15 pm

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Practical exercises of

research methodsQuantitative

Coffee / Tea Break

3.15 pm to 3:30p.m

3.30 pm to 5:30pm

Further development

and refining of Draft

research proposal

SOPHEA team

SOCHARA premises

Training Hall, SOCHARA

DAY - 4 THURSDAY 11th December 2025

Core team

Participant moderator:

reporter: Janelle Fernandes

Time

8.00 am to 8.45 am

9:15am to 9:30a.m

Recap

9.30 am to 11:00 am

Qualitative research

11.00 am to 11.15 am

Facilitator

Session name

Venue

Breakfast

At accommodation

TBC

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Dr. Shivanand Savatagi

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Tea break

SOCHARA premises

11:15 am to

12*15 pm

12:15 pm to 1:00 pm

Mixed methods

Dr Sushi Kadanakuppe

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Highlighting key

ethical considerations

and dilemmas and

examples of

mitigation to keep in

mind.

Dr. Manjulika Vaz and Ms

Janelle Fernandes

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Lunch

SOCHARA premises

All participants

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Overview of SISEC

application process

with timeline

1.00 pm to 2.00 pm

02.00 pm to 3.15 pm

Idea draft

presentation

Tea Break

3.15 pm to 3.30pm

03:45 pm to 5:00 pm

Idea draft

presentation

All participants

6:30 pm to

8:30 p.m

Participant moderator:

SOCHARA premises

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Film show & Team Dinner

DAY - 5 FRIDAY 12th December 2025

Core team reporter:

8.00 am to 8.45am

Breakfast

At accommodation

8.45 am to 9:30 am

Open Session

All

Training Hall, SOCHARA

9.15 am to 9.45 am

Alumni Sharing

Mr. Shakti Singh Shekawat

Training Hall, SOCHARA

9:45 am to 10:45 am

Practical simulation

of FGDs, In depth

interview,

participatory

mapping

SOPHEA team

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Coffee / Tea Break

11.00 am to 11.15 pm

11.15 am to 01.00 pm

Report writing

TBC

SOCHARA premises

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Lunch

1.00 pm to 2. 00 pm

2.00 pm to 3.00 pm

Journey as a Health

Researcher

Dr. Denis Xavier, SOCHARA

President and Health

Researcher

3:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Closing Remarks

All

Tea Break

4.00 pm to 4.15 pm

Evening

Tibetan Medicine,

Compassionate

healing and

Meditation

Session with Dr Jampa Yonten

SOCHARA premises

Training Hall, SOCHARA

Training Hall, SOCHARA

SOCHARA premises

At Dr Jampa's office in

Brigade Road

08

09

f'

■■

',')

5%^

I

I

I

I

CPHE

I

ni

I

I

W' ft

i'| ,g%,

/\

?■ \ St S' r3W Sft

c

\>

\*

X

^SS#4.

fai+h /

^1/

Pl

WW3:

i\

¥S kWy

n\ I

Sig'!

n

I

.

ft \ 0

l\^a>l.

I^1

jy^

^0

yzw to- 14

'A”-W/

.y?v iC Sz

Oz ZTV

I

if

■?

10'

I

CPHE

ft TIME

mmNiNB

10

is a Ji me [o^* cveeyil

goes if\e retrain of a popu.

m’

e iune7

jAnd ai dUjACJ s fiffieify year^

C7t is time to be glad and eejoicey

"Do eaise beaets and minds

in thankfulness Io Caod.

D

C7t is time also to eefleot a while-/

to see l< the signs o•f tlye times/

to renew our vision and

commitment

and to look ahea d.

The times too lyave changed/ since inception/

for better and for worse/

^Therefore/ it is in the context of todayz

and perhaps more importantly of tomorrow/

~Uhat each person/ member/ associate and friend

of OHjACf, join together

in a common search towards

making health/ and life in all its fullness/

more of a reality for people

particularly the marginalised and iKHpoveeisKed/

the sick/ the least and the last/

who inhabit an ancient land/

rich in history, culture, ideas and expression,

and ever responsive in diverse ways,

to the call of+he. lOeep.

Art work and animation by

Dr. Shirdi Prasad Tckurof CHC &. Mr. Magimai Pragasan of CHAI

Support Team from Community Health Cell (CHC)

M. Kumar, M.S. Nagarajan, V. Nagaraja Rao, S. John, James

11

CPHE

The Catholic Hospital Association of India

POST BOX 2126, GUNROCK ENCLAVE, SECUNDERABAD-500 003.

SEEKING THE SIGNS OF THE TIME

( A word from the Executive Director )

Dear Friends,

At last with gratitude to God and a big thank-you to the Evaluation Study

team, and to each one of you, I am happy to present to you this Discussion

Document arising out of the CHAI Golden Jubilee Evaluation Study. As the

study-team itself mentioned, this is not the report of the study. That would be

a really voluminous one to be ready, soon. This is not a summary of the

report, either. This is a discussion document for the use of our members

during the Golden Jubilee Year for further reflection, comments and contri

bution towards a detailed plan of action to be ready at the time of the closing

of our Golden Jubilee Year in November 1993.

However, since this document is arising out of the study, it contains all that

is necessary for our discussions at various levels. Hence, there is enough

matter for our discussions, and, to suggest concrete plan of action for, say,

the coming ten years. By now you would have already received the copy of

our re-printed book "Out of Nothing*'. Please read this book and the docu

ment, study them thoroughly and encourage others in your community/circle

to read them

And then discuss.

These should be read with interest. Relish them. Then, you will understand

their value and the taste. These will give you an idea of what CHAI was,

what it is and what it should be in the coming years. Then, it is for you to

suggest realistic and concrete plan of action. Then, it is for all of us, with

the help of the Lord, to strive together, putting our heads, hearts and hands

together to make health a reality to many more people in our country and may

be even elsewhere, with particular reference to the poor and the poorest of

the poor, thereby ensuring "fullness of life" to them. Through my subsequent

circulars, we shall keep you informed about the various steps to be taken for

discussions.

12

i

r*

f

Those of you who were at this year's convention and tho.Goldon Jubilee Year

inauguration at Guntur, would have understood the sacrifices, hardwork and

pain that went into the preparation of this document. And those of so many

people, particularly the study-team under the dynamic and inspiring leader

ship of Dr Thelma Narayan. Then, of course, the members of the Advisory

Committee and, specially Prof. P. Ramachandran and Dr. CM Francis. Then the

money that was required—a big sum indeed—which was provided so gene

rously by Cebemo, Holland.

The best way of showing our gratitude to all these, and above all, to our Lord

and Master, would be by reading, studying thoroughly and using this docu

ment the way it was intended for, and as explained above and in the document

itself, and thereby ensuring the fullness of life to our people by providing

health for many more through CHAI during the coming years.

1

f<

1

*9

a

1

O

il

H

F

V

t*

c

t

Fr John Vattamattom svd

Secunderabad

14-11-1992

<

13

SE£WW<? WE WM OF 1HE TIMES

A Discussion Document for Study and Action

arising out of the

CHAI Golden Jubilee Evaluation Study

Study Team

Thelma Narayan, Johney Jacob, Tomy Philip.

Assisted by Xavier Anthony

Community Health Cell

Bangalore, October 1992

Advisory Committee to the Study

Dr. C.M.Francis (Chairman)

Prof. P.Ramachandran (Consultant)

Dr. Ravi Narayan

Mr. P.Srinivasan

Sr. Adriana Plackal,JMJ (CHAI Representative)

Fr. John Vatlamatlom,SVD (CHAI Representative)

Fr. Jose Melcttukochiyil,CST (CHAI Representative)

IMPORTANT

This discussion document

gives basic information about CHAI and its membership,

some information about the wider context within which it functions, and

some feedback from the field

It raises issues specific to the future role and functioning of CHAI, that need to be

discussed by the membership in general.

The detailed report of the CHAI Golden Jubilee Evaluation Study will be ready

after a few months.

'This is not a summary of the Study report.

i

14

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We have deep appreciation for the openness with which CHAI has embarked on this ])roccss of

search. It is a sign of their seriousness that they allowed the searchlight to be focused on themselves,

as well as on the external milieu. We have had complete freedom in planning the study and exploring

any type ol issues with the members. We also had complete access to all documents. The privilege of

discussing a wide range of issues with the staff and associates was also ours. For a 11 this we arc grateful.

It has been an extremely enriching and fascinating experience for all of us though sometimes

exhausting!

Our gratitude goes to the many people who have made the study possible:

• To the 437 member institutions who readily offered hospitality to the investigators and spared many

hours from their busy schedules, discussing, giving feedback,and sharing about their work. This

has been an inspiration.

• To the 1032 members who replied to the mailed questionnaire and have shared their views freely

and frankly.

• To the band of forty investigators, who travelled to remote corners of the country in the heat of

summer, undeterred by bus strikes, terrorist problems, inter-state conflicts etc. Their sense of

dedication is revealed in the quality of work. They gave up several holidays fort he training, planning

and feedback sessions as well as for the field work. Some volunteered for two rounds of field work

in Dcccmbcrand in summer. Wcare grateful to their Provincials, Superiors, Rectorsand Guardians

who readily gave permission for them to participate in this exercise.

• To the forty panelists who actively participated in the Policy Delphi Method and shared many

valuable thoughts, ideas and perspectives. We are sure that CHAI will continue to benefit from

their involvement in the future.

• To the Principal and Staff of St. Joseph’s Evening College Computerand Data Processing Centre,

who thought through the programming and undertook analysis against the odds of several viruses.

• To the Staff of CHAI, who cheerfully provided us with the necessary information and shared their

own ideas and perspectives.

• To the CHAI Executive Board and most specially to Fr. John Vatlamattom, SVD, Executive Director

of CHAI, for daring to undertake such a journey. We deeply value the trust they have placed in

us to undertake this task. They along with representatives ol the regional units have also shared

their views about CHAI.

• To the Staff of Community Health Cell who supported us through every need and deadline, working

late into the evenings.

• Last and most importantly to the Advisory Committee of the Study, who have given much of their

lime and energy. They have provided us the light of wisdom and cxpert.se and have encouraged

us during our difficult moments.

' ’ ’ i our personal limitations, and also within

We have tried to give our best to the Study, within

framework.

The responsibility for any drawback is entirely

the constraints of a nit her tight lime 1

ours.

ii

IS

c

FOREWORD

vp;

Gandhi Jayanthi Day, 1992.

Uniting together to serve better,a group of dedicated and committed Sisters,working in the

field of lhe Healing Ministry,started on a yalra (journey) in 1943. Under the leadership of Sr. Dr.

Mary Glowery,they formed lhe Catholic Hospital Association of India for mutual support in the

service of the people. What were the objectives of the association? Have they been realised? Have

those objectives been changed over lhe period of lime? Do the objectives continue to be relevant

today? What changes arc necessary to make the objectives relevant in the foreseeable future? What

steps should be taken to achieve lhe objectives?

The Catholic Hospital Association look a bold and necessary step to evaluate the work of the

association and to formulate future tasks. The work was entrusted to the Community Health Cell.

Dr.Thelma Narayan and her team have been doing an excellent piece of study and research, with

the help and advice from Prof.P.Ramachandran,Director,Institute for Community Organisation

Research,Bombay, Dr. Ravi Narayan and many others. That report will be ready soon.

Il is essential that the report should be acted upon soon and not allowed to gather dust. To

enable the members and the association to address the more important findings and issues out of

the study,this booklet has been prepared. It is for the study and reflection by each member and

groups al various levels - Diocesan,State and National. That reflection and study must lead on to

decisions and lime-bound action,appropriate for each member and the association.

May the Good Lord guide us to lake the right steps in the right direction in the service of the

people and carry us in His palms,should difficulties arise.

Dr. CM. Francis

Chairman

Advisory Committee

Bangalore,

02.10.92.

CHAI Golden Jubilee Evaluation Study

iii

16

C O N i K N T ti

Acknow'Uxhynicnix

ii

Foreword

Hi

i

PART—A

I

01.

Introduction

1

02.

Study Methodology at a Glance

2

03.

Highlights from History-

04.

CHAJ Today — A Bird’s Eye View

9

05.

Profile of CHAI Membership— 1992

12

06.

Perceptions from the Field

16

07.

Directions from Delphi

08.

Glimpses of Health and Disease in India

26

09.

A Lamp V> Guide Our Feel

28

P A RT—B

10.

Important I'/.u'/, lor the Fuhm: ol ( fl Al

(he '//re of (bo

P A H J

I I.

I h< Nai/o/>al IP

12..

13.

C

L/h;.>iioh

• ?//) '/I ,

■a

33

O' i.

J p ;.ihb and //ho^ u' .

f#om z Fn O/1 \Af

t1 z ouu/ii Ion, » b in vn

!»’

• J/

pn • Hi/ /'//la / •>! Hh f hull II III India

.'.i. b.i fh 'hit • in* /\|Hii«iitlab lauu.nx

58

51

oO

17

PART A

INTRODUCTION

This document forms part of a process of ongoing search for meaning, relevance and direction for

the work of CHAI and its constituent members, in the context of India today, as integral components

of the health and social apostolatc of the church in India, and as citizens of the country.

It was in this spirit that the CHAI Golden Jubilee Evaluation Study was initiated by the Executive

Board and Director of CHAI in 1991. This was in preparation for the Fiftieth Anniversary of CHAI,

to be celebrated in 1993. The process of seeking the signs of the times, from members as well as from

others, employed methods of research available to us today.

Efforts were made to be as interactive as possible with members, staff and others, while also

maintaining objectivity. Rather than being an outside “expert” evaluation giving recommendations for

the future, it attempted to generate and draw from discussion and thinking among people at different

levels. This was both from within the Association as well as from outside.

Very many persons have participated and contributed to the process -

o 62.3% of the membership i.e., 1415 institutions have shared information about themselves,

and have given feedback and suggestions for the future.

o 40 persons outside of CHAI, with long years of social concern and involvement in diverse

fields relating to health and development, actively helped give an outside perspective.

o 40 investigators travelled the length and breadth of the country visiting members, often

through difficult terrains.

o The staff, executive board membersand representatives of regional units of CHAI also gave

feedback and suggestions.

The analysis and report will not be able to capture entirely or do justice to the depth and range

of discussions and feedback. However, we are sure the process has generated interest and

involvement. Many expectations too have probably been raised!

Some of the major issues and concerns that emerged during the process of data collection and

study arc being raised in this discussion document. Issues important for the future of CHAI,

that need to be discussed by the membership in general arc the ones that have been highlighted.

This document has been derived from all the components ot the study. However, it is not a report

of the study and its findings. The main study report will be a specific publication giving much

greater detail. It will be available for wider circulation within a fewr months.

The purpose of this document is to facilitate the second phase of the study-reflection process being

planned by CHAI. This will include discussions at regional levels, in small group meetings, and in

individual institutions.

The document may need to be read in small doses. Different parts may be used for a series of

meetings and reflections. It isourhopclhat issues that have arisen trom members and others in thestudy

process, and given in this document could be the focus of,or background in which the Golden Jubilee

reflections can take place.

18

r

STUDY METHODOLOGY AT A GLANCE

• After a preparatory phase of idea drafts and brain storming, the study started on a full lime basis

from July 1991.

• The aims of the study were:

1. To undertake an analytical study reflection on the Catholic Hospital Association of India

during the last five decades focussing particularly on the past twenty five years and the

present.

2. To explore possible roles the Catholic Hospital Association of India could play in the future,

in the context of the needs of its members, the national situation and the national health

policy, and as part of the voluntary' health sector and the health aposlolale of the Church.

• Specific objectives and methodologies were worked out towards achieving these aims. These

included :

— an analytical historical review;

— eUhetion of information and feedback from members;

— departmental and financial reviews;

— the use of the Policy Delphi Method to explore future scenarios and roles; and

— discussions with a number of people associated with CI I Al.

The membership as of October 1991 which comprised 2270 institutions, was taken as the cut

off point or sampling frame for the study of members. The members arc spread across the country.

They consist primarily of health centres, dispensaries, hospitals and a smaller number of diocesan

social sendee societies and social welfare organisations like orphanages, homes for the aged,

rehabilitation centres etc.

• For a detailed study of members, a 20 percent sample, comprising 455 institutions, was selected

using scientific statistical principles. It was a stratified random sample. Representation

..CH*'"

X

2

19

accord ing to size of insitution and location was ensured. This group was visited by investigators.

O Forty investigators received a six day preparatory training before visiting the member institu

tions. We were fortunate to get volunteer scholastics to undertake this important component.

They included Gipuchins (OFM Gip.,) and Franciscans (OFM) from Kripalaya and Alma

Jyothi respectively from Mysore; Jesuits from Vidyajyothi, Delhi; Diocesan brothers of Delhi

from Pratiksha, New Delhi; and a Priest from St. Thomas Mission Society, Mandya.

A field tested interview schedule was used during the discussions. Besides eliciting feedback

on the different aspects and programmes of CHAI, information was gathered regarding the work

involvements and activities of member institutions and the problems faced by them in the field.

O Questionnaires were mailed to the remaining 80 percenter 1817 member institutions. This was

the same as part A of the interview schedule. The purpose of this exercise was to gather uptodate information about the work of member insitutions, so as to enable future planning to be

related to the realities of members and their needs.

O Structured feedback and views from the staff, executive board members and representatives of

the regional units of CHAI was also gathered and analysed.

O A f inancial review (higher audit) was done by an outside expert and departmental reviews are

being done along with the departmental staff.

O The Pol icy Delphi Method was used with a group of forty persons to identify trends in the socio

pol ilical and economic spheres in India and their impact on the health status of the population

in the country. In this context and keeping in mind the specifics of CHAI, possible future roles

of the Association were explored. The panelists represented diverse fields including education,

management, communication, theology, psychology, sociology, social work, law, medical

ethics, pastoral care, development, nursing and nursing education, different disciplines of

medicine, viz., medical college profcssionals/educators, mental health, community health,

policy makers, researchers and representatives of other national level coordinating agencies/

networks in health.

© Secondary sources of information were studied for the section on the national health situation

and on Church teachings regarding health and related work.

® The entire study was guided by an Advisory Committee of seven members which met four times

during the year.

© The study team consisting of four members was based in Community Health Cell, Bangalore.

® The St.Joseph’s Evening College Computer and Data Processing Centre, Bangalore provided

the technical and infrastructural support for computer analysis of the data. Their staff helped

with programming and supervision of data entry.

The Staff of different departments of CHAI provided us the necessary support in collection of

information.

3

20

HIGHLIGHTS FROM HISTORY

The Catholic Hospitals Association (CHA)

was started on the 29th of July, 1943, by a group

of sixteen Sisters involved with medical work in

different parts of India. This was before Independ

ence, during the period of the Second World War.

Though rich in resources, several factors over the

years, including colonialisation, had had an

adverse impact on the country. The health

situation of people then was poor, especially that

of women and children. Epidemics and famines

took a heavy toll. Medical services, particularly

for the majority of the population in the rural areas,

were scarce.

Sr. Dr. Man' Glowcry.

The Sisters, all medical professionals, had

(Sr. Mary of ihc Sacred I lean, J Ml)

already been working for many years in remote

Foundress of C.I l.A.l.

parts of the country. Some of them had been

pioneers in initiating the medical aposlolatc of the Church during the 1920’s. In those days, they

had to get special permission from the Vatican to practice medicine and conduct deliveries, as

members of religious congregations. Several Sister nurses also worked in Government hospitals

in the early half of the century.

Inspired by the teaching of Pope Pius XII to ‘organise the forces of good’ and by medical

associations in India and abroad, the Sisters formed the Catholic Hospitals Association. This was

after a few years of ground work with the Bishops, superiors of congregations, Catholic medical

institutions and religious medical personnel working in government hospitals. The Resolutions of

the first meeting were :

— to establish a Catholic medical college and a collegiate course in nursing,

— to publish a pamphlet or magazine, and

— to appoint a Board of Examiners in nursing and midwifery.

The Association was registered as a Society in 1944. During the early years all the office

bearers had full time medical/nursing responsibilities as well. The Association covered India,

Burma, Srilanka (and Pakistan after partition) till 1956. They had annual meetings, and since 1944

regularly published an in-house bulletin named ‘Catholic Hospital'.

A Catholic medical college committee was formed and after more than ten years of lobbying,

fund raising and working through many details, the project was handed over to the Catholic Bishops

Conference of India (CBCI).

The CHA Nursing Board functioned for some years and was later closed after the formation

of the Indian Nursing Council, which was set up for the standardisation ol nursing education.

4

21

Members played an active role in setting up schools for the training of nurses, midwives and

auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM’s).

Issues of medical ethics were raised and discussed al various forums of the Church and the

medical profession. CHA encouraged and fostered the formation of Catholic nurses and doctors

guilds for this purpose.

In summary, the main focus of CHA during the first fourteen years was on :

a. Promotion and upholding of ethical values in medical care.

b. Fostering the professional education of nurses, doctors, pharmacists, laboratory' techni

cians and auxiliary nurse midwives. This was with a view to providing competent and

qualified staff for member insilulions.

c. Issues relating to the betterment of medical care and to the professional running and

management of hospitals. Members kept abreast with developments within India and

also internationally. They were encouraged to join and participate in national professional

organisations.

Over the years, the numberof Church related

medical and health insilulions, and consequently

the membership of CHA, also grew. In 1957, the

first full lime Executive Director of CHAI was

appointed. He was also one of the secretaries of the

CBCI Commission on Social Action. Thebullctin

was renamed ‘Medical Service’. Much work was

done towards the framing of a new constitution,

which was registered in 1961 and to establishing

sound procedures of functioning.

; .■ ..-.W

Me? ■ ■

’

AS'*''.'

The emphasis during the next decade (1957 1968) was on :

a. Providing continuing education inputs

to its members through the journal, the

Fr. James. S. Tong, S J.

annual conventions and through

Executive Director of C.H.A.I.

1957 - 1973

seminars,a nd

b. providingassistance to members to meet

their needs for medicines and equipment by developing linkages with various agencies,

donors and government.

The annual meetings gradually grew into annual National Hospital Conventions. Different

departments developed, namely, Membership; Projects; Publication; Employment; National

Hospital Convention and Exhibition; and Responsible Parenthood.

The importance of public health and outreach to the community was recognised. The

implications of the Second Vatican Council documents and teaching to health work was discussed

atan annual convention. Ecumenical and latersccular linkages were further strengthened as a result.

Working with government was actively pursued.

5

22'

In 1969, an important meeting of Christian health leaders in India was held. Il was sponsored

by the Christian Medical Commission, Geneva. Community Health was identified as a major

priority and also the need for working together. As a follow up, the ecumenical ‘Coordinating

Agency for Health Planning' (CAHP) was jointly set up by the Christian Medical Association of

India (CMAI)and by CHAI in 1970. Slate level Voluntary Health Associations began lobe formed

from 1970 onwards, with Bihar taking the lead. This resulted from an understanding by CHAI and

CM Al, that the voluntary health sector must work together in a coordinated and more decentralised

way. Since heal th was a State subject, it was considered appropriate to have Slate level associations.

In 1974, these were federated al the National level into the Voluntary Health Association of India

(VHAI). The Executive Director of CHAI, who had been in that position for seventeen years, was

very involved in all these developments. In 1974, he moved from CHAI to the leadership position

in VHAI. He was also the moving force, along with others, in the formation of Catholic Charities

India, which later developed into Caritas India.

Among several initiatives which received the active support of CHAI were :

i.

the federation ofthc numerous nurses guilds all over the country into the Catholic Nurses

Guild of India (CNGI),

ii.

the units of St. Luke’s Medical Guilds which had been fostered by CHAI were federated

into the Indian Federation of Catholic Medical Guilds (IFCMG),

iii.

natural family planning and the concept of responsible parenthood were introduced.

-

Later, the Natural Family Planning Association of India (NFPAI) was formed as an

autonomous group by several involved people,

iv.

the Hospital Pastoral Care Association was formed in 1971. This was the only initiative

that did not survive,

v.

the Executive Director was also closely involved in the formation of the Indian Hospital

Association (IHA).

After 1974, by mutual agreement, VHAI focused primarily on community health, technical

issues and linkaging with government. CHAI began to develop further, the more specifically

Catholic areas of its work. New departments and honorary consultative committees were set up.

These included Responsible Parenthood, Pastoral Care, and Medical Moral Affairs. The Central

Purchasing Service (CPS) and legal services were also skirled.

Further amendments to the Constitution were made in 1978. These objectives of CHAI hold

good till today. They are :

1.

To improve the standards of hospitals and dispensaries in India.

2.

To promote, realise and safeguard progressively higher ideals in spiritual, moral,

medical, nursing, educational, social and all other phases of health endeavour.

3.

To promote community health and family welfare programmes.

4.

To assist voluntary health organisations in procuring quality amenities.

Since 1980, which marks the beginning of the present phase, CHAI has continued to grow and

develop. Its membership (as of October 1991) is 2215 member institutions, 57 Diocesan Social

6

23

Service Societies and 32 individuals who have Associate Membership. In September 1992, the

membership was 2308. The office has shifted from the few rooms in the CBCI Centre, Delhi, to a

much larger pcrmanentofficeatSccundcrabad. The numberof full timestaff has increased to about

sixty. Medical Service was transformed into Health Action in 1988 and is published by a separate

registered society, 'Health Accessories for All’ (HAFA). Other publications have also been

brought out.

CHAI adopted for itself the goal of‘Health For Many More’ (a modification of the Alma Ata

goal of Health For All by 2000 AD), with a special emphasis and focus on the poor. An earlier plan

was put into action and a department of community health was developed in 1981. The concept of

Community Health was understood “as a process of enabling people to exercise collectively their

responsibilities to maintain their health and to demand health as their right”.

Some of the influencing factors during this phase were :

ii.

The Alma Ata Conference of WHO (1978),

A regional consultation of the Christian Medical Commission held in Delhi (1980),

iii.

The articulation of the National Health Policy (1982),

iv.

The social teachings of the Church,

v.

The introduction of social analysis by the Indian Social Institute and others,

vi.

The growing experimentation in the country in community health and other areas.

i.

In 1983, CHAI adopted for itself the following ten point programme for the next decade:

1.

2.

“Promotion of community health programmes, according to our new vision.

Promotion of spiritual and pastoral aspects of health care.

3.

Promotion of “Respect Life” with special emphasis on just wages and healthy

human relations etc., in our institutions and promotion of natural family planning.

4.

Working towards self sufficiency of CHAI programmes, especially by collaborating

with the Government at various levels and utilising their resources.

Building up of solidarity among our member institutions especially by promoting

the idea of adopting rural health centres by big hospitals.

5.

6.

Diocesan and regional level organisation of CHAI.

7.

Membership drive for strengthening the organisation.

Promotion of low-cost medical care by influencing a better drug policy, prescription

pattern and standardising of drugs.

Promotion of indigenous medicines and systems of health care.

8.

9.

10.

Holistic approach to health and training of new types of health care personnel in

large numbers”.

New departments and activities were also initiated, for example continuing medical education,

library and documentation services, pastoral care (rebirth!) and lowcost media. Short courses were

offered which ranged from ‘Human and Spiritual Growth through Clinical Practice to a variety

of management courses. Short courses in community health and longer community health team

training programmes (CHIT) were also initiated. This was later supplemented by a course on

7

24

I

Community Health Organisation, Planning and Management (CHOPAM) in collaboration

with VHA1.

The CBCI has always had a section or commission on health. In the 1980’s this was for some

time part of the commission on Justice and Peace. The CBCI commission on Health Care

Apostolate was separated out in 1989. CHAI hasalways participated actively, in various capacities

in these commissions.

i

CHAI had initiated the process of drawing up health policy guidelines for member institutions.

A draft policy was circulated to all members in 1988 with a plan to finalise this through a process

of regional meetings. Following a series of meetings in which CHAI was involved as a participant,

the CBCI Commission for Health Care Aposlolatc brought out Health Policy Guidelines for

Church-related health institutions.

Many important events and changes have taken place in its external milieu since CHAI was

formed in 1943. These have been within the Church, in the national and international socio-pol ilical

situation, and also in the area of medicine and health. There have been changes in thinking regarding

concepts of causation of disease and typesand levels of intervention that would improve the health

of people, both as individualsand communities. The health and medical care scenario in India has

also changed, with tremendous growth in the governmentand privatesectors and changes in disease

patterns among the population.

The role of CHAI today and in the future has to be located in this broader context. Equally

important is the role of CHAI as part of the healing ministry/health apostolate of the Church, where

health is not seen only in technical, professional or in its socio-political aspects but is also related

to the deeper dimensions of personhood, relationships, spirituality and faith and also to wholeness

of creation, justice and peace.

At this point in history, it is important for those of us who happen to be present, to reflect

analytically on the past and present so that we can be better equipped to build the future.

The early pioneers of the medical apostolate of the Church and of CHAI, thought far ahead of

their times. Many of their ideas were considered foolish or at best “impractical dreams”. It was

recorded in a newspaper in 1944 that CHAI was formed “out of nothing”, that is when there were

hardly any Catholic hospitals! And Sr. Mary Glowcry has been described as a 'grain of wheal who

dreamt of a golden harvest’. Today we are witnesses to a multiplication of that grain. How we

respond to the challenges facing us today may be studied fifty years later! We now ask ourselves

the question “Harvest for whom and for what”?

"The Important thing Is this —to be able at any moment to sacrifice what

we are for what we can become."

Anon

8

25

CHAI TODAY — A BIRD’S EYE VIEW

1. Distribution of CHAI Members According to Size/Type:

As of October 1991, CHAI has 2302 members spread across the country. The break-up

according to size/ type of insitutions is as follows :

1148

388

591

86

57

32

(49.9%)

(16.8%)

(25.7%)

(3.7%)

(2.5%)

(1.4%)

2302

(100%)

1163

(52.5%)

b. Central Slates (Bihar-160, Madhya Pradcsh-205, Rajasthan-30,

and Uttar Pradesh-118)

513

(23.2%)

c. The North Eastern Slates (Manipur-20, Meghalaya-47,

Mizoram-4, Nagaland-19, Tripura-4, Sikkim-1 and Assam-51)

146

(06.6%)

d. Other States (Goa-29, Gujarat-58, Harayana-11,

Himachal Pradcsh-3, Jammu & Kashmir-5, Maharashtra-94,

Orissa-79, Punjab-28, West Bengal-67 and Union Territories-17)

391

(17.7%)

2213

(100%)

a. Health cenlres/dispensarics with no beds for inpatients to be admitted—

b. Health cenlrcs/dispensaries withl to 6 beds

—

c. Hospitals with 7 to 100 beds

—

d. Hospitals with more than 100 beds

—

e. Diocesan Social Service Societies

—

f. Associate members (individuals having no voting rights)

—

TOTAL

2.

The Geographical Distribution of Members:

a.. The four Southern Stales (Kerala-403, Tamilnadu-380,

Andhra-227 and Kama taka-153)

TOTAL

N.B.

The 57 Diocesan Social Service Societies and 32 Associate members are not

included here.

3. Organisational Structure:

a. CHAI is registered under the Societies Registration Act. The members of the general body

elect a nine member Executive Board with a President, two Vice-Presidents, Secretary,

Treasurer and four Councillors. Three posts arc elected every year, so as to ensure continuity

in the Board. Board members arc elected for three years and may be re-clecled fora second

lime. The Board appoints an Executive Director, Assistant Executive Director and Admin

istrator. There arc various departments in the CHAI Head Office at Secunderabad staffed

by over sixty people.

b. Membership is of two classes, constituted (institutional) and associate (individuals). The

latter do not have voting rights.

9

26

c. Prior to 1981, voting rights were according to size of institutions. Thereafter a constitutional

amendment equalised voting rights to one vole per member.

d. About 15.0 percent of the total membership arc life members and the remaining arc annual

members. Life membership was introduced in the 1980's.

c. Rcgional/Slalc Units:

There is a provision for the formation of Rcgional/Statc Units in the Constitution. Attempts

were made to form such units ever since the Silver Jubilee in 1968 with varying success.

After 1980 greater efforts were made in this direction. Regional or Slate units arc separate

registered bodies, but linked to the Centre. The membership fees arc divided equally between

the centre and the units. The units al present arc :

i. Catholic Hospital Association of

Kerala.

ii.

REGIONAL UNI1S Of CHAI

Catholic Health Association of

Tamilnadu.

iii. Catholic Health Association of

Andhra Pradesh.

iv.

Orissa Catholic Health Association.

v. North Eastern Community Health

Association (NECHA).

vi.

,11

Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh Catholic

Health Association (RUPCHA).

iftil

£2 RAJA5TH4N 8 U-P (RUPCHA)

E2) ORISSA COCHA)

Karnataka and West Bengal have had

E3 north eastern states

occasional meetings. Some dioceses

□ Ural.

C-ecKA)

EUD KARmATAKA * WE5T 0EN6ALalso have diocesan level activities.

Slffil Andhra pradech

TAMIL- M A Du (chat)

During the early eighties diocesan

health coordinators were identified.

North and South zone meetings were held. This attempt did not last long.

4. The Headquarters and Units:

A. The Departments al the CHAI office include:

a. Administration (General).

b. Accounts and Finance.

c. Membership.

d. Central Purchasing Service.

c. Community Health with four sub-units

i. Rural Health

ii. Urban Health

iii. Research (Planning stage)

10

E

27

iv. Low-cosl communication media.

f. Continuing medical education.

g. Documentation.

h. Pastoral Care.

i. Electronic Data Processing.

B. Zonal Office in New Delhi

C. A separately registered society named ‘Health Accessories For AIT (HAFA) brings out the

monthly magazine called” Health Action” and other publications.

D. Additional Projects:

a. The CHAI Farm Project - with poultry, agriculture, etc for income generation. There arc

plans underway lo start a model integrated health centre with community health

programmes and a training centre.

b. A Central Drug Quality Assurance Laboratory is being planned. This will test drugs and

pharmaceuticals as part of quality control for rational drug therapy and to support the

network of low cost generic name drug manufacturers. A feasibility study has been

carried out.

5. Finances:

The funding of the activities of the Association depended on membership fees and donations

from members in the earlier years. Later some funds were available by processing purchases ot

Indian equipment through donor agencies abroad. Additional sources were from exhibitions of

medical products at the conventions and advertisements in the journal. This has been restricted

since the mid-eighties in order to fit in with the overall philosophy of the Association. In the mid

seventies and eighties, funds from foreign donor agencies began to be utilised for specific projects

and programmes. Initiatives towards self-reliance have been the starting ol a Corpus Fund, the Farm

and a raffle, besides the sale of publications by HAFA.

6. Linkages:

a. CHAI has close interaction with CM Al and also with VHAI. The “Health and Healing Week”

reflections and celebrations arc jointly planned with CM Al. Together they have brought out

the Joint Hospital Formulary. The three organisations also jointly sponsor and conduct

seminars and workshops.

b. CHAI also interacts with thcCSl, Ministry of Healing, the Asian Community Health Action

Network (ACHAN), the All India Drug Action Network (AIDAN) and the International

Association of Catholic Health Care Institutions.

c. CHAI cooperates with government and other organisations to promote health and

development.

1 1

(

28

PROFILE OF CHAI MEMBERSHIP — 1992

A member is the most important person for us

She is not dependant on as, ive are dependant on her,

She is not an interruption in our work,she is the purpose of it,

She is not an outsider in our business,she is part of it,

We are not doing her a favour by serving her,

She is doing us a favour by giving us an opportunity to do so.

— Adapted from Mahatma Gandhi.

The profile of the present membership of CHAI indicates its distribution, diversity and

richness. For those familiar with the history of CHAI, it is evident that the membership is a dynamic,

alive entity, undergoing several changes over lime.

In this document only a brief sketch is given so that the discussion about the future role and

strategics of CH Al may take into consideration the realities of the membership today. Greater detail

and analysis is given in the main report.

The membership of CHAI as of October 1991 was taken as the cut-off point for the study.

This comprised 2270 institutions including Diocesan Social Service Societies. Associate members

(individuals) were not included. We have data from 1472 or 64.8 percent of the total membership.

Included in this group are the 20 percent of the total members (the stratified random sample) visited

by investigators and the respondents to the mailed questionnaire. The Runs Test performed showed

that these respondents were randomly distributed. Of this group of 1472 institutions, 57 i.e., (3.9%)

have closed/arc not functioning presently. This is 2.5 percent of the total membership.

The information that is given in this section is therefore derived from 1415 active respondent

member institutions. This number is the denominator in all tables.

1. Year of Establishment:

• 14 institutions (1%) were established before 1900,

• 93 (6.6%) during the first fifty years of this century, and

• 1186 (83.8%) thereafter, till October 1991.

While institutions established earlier were mainly hospitals, in later decades smaller dispen

saries and health centres became more common.

2. Ownership/Management:

• 66.9% are owned by congregations of women religious, while 76.9% are run by them.

3. Geographical Location:

• 67.8% (959) institutions are in rural areas,

• 15.6% (221) in tribal areas, and

• 16.6% (235) in urban areas.

12

29

Thus 83.4% arc located in rural/lribal regions. At the national level, all sectors put together,

hospitals, beds and doctors are more concentrated in urban areas compared to rural areas in a ratio

of 80:20. Dispensaries, however, arc more rural based. This is, therefore, notvcry different from

the overall national situation. However, the level of functioning and effectiveness of Government

primary health centres and dispensaries is very variable.

4. Nature of Institution:

O 93.9% (1,329) arc primarily medical care institutions. Of these

— 57.0% (806) are dispensarics/hcalth centres,

— 18.7% (265) general hospitals,

— 9.2% (130) maternity centres and maternity centres cum dispcnsaries/hospitals.

— 4.1% (058) community health cenlrcs/projecLs.

— 4.9% (070)have a specific focus on leprosy, tuberculosis, mental health, cancer etc.

O 6.1 % (86) includesocial welfare organisations (homes for the aged, orphanages, rehabilita

tion centres etc.) and diocesan social service societies. Most of these have components ol

mcdical/hcalth work.

5. Medical Care Institutions According to Bed Strength

O 35.5% (502) have no beds, and

® 21.6% (306) have one to six beds.

This large group of 57.1% (808) could be considered as health outposts or primary health

centres.

© 32.3% (458) arc small hospitals with 7 to 100 beds. Of these 318 have 7 to 30 beds.

O 4.90% (69) arc large hospitals with more than 100 beds. Of these only 3 have more than

500 beds.

Different strategics would be required to meet the needs of these broad groups of members,

namely health centres, small hospitals, large hospitals, social welfare organisations and diocesan

social service societies. The work or circumstances in which they function as well as their needs,

problems and potentials would be quite different.

6. Distribution of Hospital Beds:

The total number of hospital beds in the respondent institutions is 31,245. A further analysis

of the distribution of beds is revealing :

a. Rural-Urban Distribution of Hospital Beds

— 58.1% (18,160) arc in rural areas,

— 4.9% ( 1,521) arc in tribal areas, and

— 37.0% (11,564) arc in urban areas.

13

30 .

b. Statewise Distribution of Hospital Beds

• 41.0% (12,827) arc in Kerala, 30.1% (9,418) arc in the remaining three Southern States,

namely Tamilnadu - 11.9% (3,713), Andhra Pradesh - 11.5% (3,599) and Karnataka 6.7% (2,106). The remaining States have 29.0% (9000) beds.

• 81.3% (25,390) arc located in Stales where health indicators arc relatively good, that is,

where the targets for 1990 laid down in the National Health Policy have been achieved.

And 18.7% (5,855) arc in the States where health indicators arc poor.

Historical factors probably account for this pattern. It could however be suggested that further

investment in terms of infrastructure and expansion should be in areas cf greater need.

7. Systems of Medicine/Methods of Healing Practised:

A fairly large proportion of members use methods/systems of medicine other than allopathy.

In these eases, most often more than one system/method is practised.

f*

93.9% (1328) use Allopathy,

24.7% (350) use Herbal Medicine,

10.6% (150) use Ayurveda,

8.3% (117) use Naturopathy,

7.1% (101) use Homeopathy,

4.5%

(64) use Acupressure,

4.4%

(63) use Magnetotherapy and

4.4% (63) use other systems/methods.

• 61.7% (864) practice only allopathy, 3.1% (44) do not practice allopathy and 32.8% (464)

practice allopathy along with one or more methods/systems ot medicine.

During the past ten years CHAI has promoted herbal medicine and non-drug therapies. So too

have other organisations. The time is ripe now to initiate investigation and study the strengths and

weaknesses of these methods.

8. Work Profile:

• 46.3% (655) have cxtcnsion/outrcach programmes.

A range of approaches namely camps, mobile clinics and extension services are used for

curative and preventive/promotive health work. Some arc also involved in awareness raising

activities.

86.9% (1,230) arc involved in some type of mother and child health work.

Communicable disease control programmes

— 22.4% (317) have tuberculosis control programmes,

— 12.9% (183) arc involved in control of leprosy,

14

31

— 37.2% (526) in control of diarrhoea and gastrointestinal disease,

— 40.1% (568) promote oral rchydration solution.

O 63.7% (902) have programmes for health education and a variety of methods are used.

O 46.8% (633) arc involved with awareness raising activities among the community with

whom they work. A wide range of issues arc taken up.

O 32.3% (456) undertake preparation of some medicines in their institutions. These include

mixtures, ointments, ORS packets, powders etc.

O 20.2% (286) have introduced rational therapeutics in their institutions.

O 13.4% (189) purchase medicines from low-cost drug manufacturers.

O 12.6% (179) have got herbal gardens.

9. Time and Budget Allocation for Preventive Work:

O 53.0% of members spend more than 50% of their lime and 58.3% of them spend more than

50% of their money for preventive and promotive work.

10. Training

O Training of a variety of community based workers is undertaken by the members.

— 29.1% (412) train community health workers,

— 9.7% (138) train traditional birth attendants (dais),

— 8.1% (114) train natural family planning teachers.

O Training of more specialised health personnel is undertaken by 6.4% (90) institutions.

® 30.4% (430) have continuing education programmes for their staff.

n.

Distribution of Personnel:

There are a total of 28,133 personnel working in these 1415 institutions.

O 11.3% (160) were single personnel run institutions,

® 78.4% (1109) had nurses,

® 41.0% (581) had doctors,

® 22.0% (312) had pharmacists, and

• 30.9% (430) had laboratory technicians.

12. Referral of Patients:

The member institutions refer patients to the following sectors :

• 66.8% (945) to government hospitals,

• 40.0% (567) to mission hospitals,

• 36.6% (518) to private hospitals.

15

32

PERCEPTIONS FROM THE FIELD

Feedback on various aspects of CHAI has been gathered from members, those on the

Executive Board, representatives of regional units, as well as from the staff of CHAI.

All members have had the opportunity to share their views regarding the strengths and

weaknesses of CHAI, their expectations from CHAI and their suggestions regarding future thrusts.

The 20% member institutions which were selected for a detailed study gave feedback on objectives,

organisational structure and each of the various programmes and activities of CHAI. The level of

involvement of members with CHAI during the past five years was also studied.

The overall response rate to the mailed questionnaire, as well as the response to each question

has been high. The volume of information gathered has been large. The first round or the

provisional analysis of this data has been done. However, more time is required for further analysis,

integration and assimilation.

In this section, keeping in mind the above

constraints,some of the main findings from the

members’ feedback have been given. This is to

make available the trends of views of members.

This would help as part of the background for the

regional/small group meetings being planned dur

ing the Jubilee Year.

A process of Teductionism’ has been neces

sary as we have had to code, summarize and be

concise. The main report will cover these aspects

in much greater detail.

Strengths

The fifteen major strengths of CHAI in

descending order of priority, as identified by

members are given. 62.0% (878) members re

sponded to the question on strengths.

1. Support, concern and service for its members.

Il is “a hand to hold on to” in the words of a

member.

2. “Health Action” and other publications.

3. Training programmes, seminars and courses.

4. Meetings and correspondence with members.

THEM®!

5. That the association is organised and is func

tioning well.

r

t

16

33

6.

The large number of members spread throughout India — that it is a national level body.

7.

It is a network imparting education to Catholic hospitals and dispensaries.

8.

It is a forum for unity, where like-minded people can come together.

9.

Conventions and similar meetings.

10.

Community health policy.

11. Dedication to health work.

12.

Alertness to the needs and signs of the times.

13.

Philosophy and vision.

14.

Preferential option for the poor, reaching out to the marginalised and involvement in social

issues.

15.

Dedicated and efficient staff.

Weaknesses

The fifteen major weaknesses of CHAI in descending order of priority as identified by

members arc given. 45.0% (640) member institutions responded to the question on weaknesses.

1.

Poor interaction between CHAI and its members, poor personal contact and communication,

and sense of alienation felt by members.

2.

Inadequate focus on rural based members and their activities.

3.

It does not fulfill the needs of its members and does not look into their problems.

4.

CHAI programmes arc not accessible to many members in terms of cost and their location,

especially for the smaller ones.

5.

Poor functioning of the regional and State units. The centre does not take much interest

in them.

6.

Services offered arc meagre and inadequate.

7. The administration and functioning is not efficient.

8.

CHAI is not practical in its approach.

9.

Concentration on bigger hospitals.

10.

Discrimination between members in its service.

11.

Too much centralisation of power.

12.

Charging for “Health Action” to small/poor institutions.

13.

Lack of initiative of members in activities of CHAI.

14.

Lack of professionalism. It is run as a religious association. Lack of qualified personnel in the

mcdical/heallh field.

15.

It does not stand for its objectives.

17

34

Expectations

The fifteen major expectations that members have of CHAI arc given. 69.0% (978) members

responded to the question on expectations.

i. Better interaction between CHAI and members through visits, more personalised

correspondence.

2. Financial assistance.

3. Guidance and support to member institutions, especially smaller ones.

4. Training programmes at the State level, preferably using regional languages.

5. Medical aid (supply of medicines) on a regular basis.

6. CHAI to focus on rural areas.

7. Provision of information to improve health work.

8. Courses/scminars on labour laws, social analysis.

9. Production of health education material in local languages.

10. CHAI should be ready to help members out of their problems.

n. CHAI to arrange for doctors who arc efficient and service minded to work in member

institutions.

12. Support to/ promotion of community health programmes.

13. Promotion of low cost drugless therapy.

14. Strengthening of regional units.

15. Training for community health workers.

Future Thrusts

The fifteen major suggestions for future thrusts of CHAI from members arc given. 55.0%

(775) members responded to the question on future thrusts.

i. Focus on rural and tribal areas and their development.

2. Community health and development.

3. Health for All by 2000 AD, including cooperation with Government to achieve this goal.

4. Health education/Health awareness.

5. Training programmes to be organised on different aspects of health care.

6. Wholistic health.

7. Preferential option for the poor and social justice in the healing ministry.

8. Interaction with member institutions.

9. Women’s development programmes.

18

• 35

io. Work on prevention of AIDS/Canccr/mcntal illness.

11. Alcoholism and Drug dependence.

12.

Assistance to institutions working for rural health.

13.

Regional planning and action as per the vision of CHAI.

14.

Support to members in their activities.

15.

Supply of free medicines.

DETAILED STUDY FINDINGS

Some of the key findings from the detailed study of the members arc highlighted here. These

were the 20% of members (455 institutions) visited by investigators. Fifteen institutions could not

be covered due to unforeseen reasons, thirty two were closed and one institution refused to

participate. The number of institutions functioning currently in this group is 407. This therefore,

is the denominator in the pcrcentagcs/tablcs given in this section.

A. Level of Interaction with CHAI:

O 97.3% (396) receive the circulars from CHAI regularly.

O 13.8% (56) have been visited by staff members/olTice bearers of CHAI during the past five

years that is, 2.8% per year. A higher percentage of institutions with bed strength of more

than 6 were visited than smaller institutions. Institutions visited were more in regions of the

country with poor health indicators rather than those with good/better health indicators.

More urban based institutions are visited than rural and tribal. The differences given here are

statistically significant.

O 25.1% (102) institutions have participated in some programmes of CHAI during the

past five years. These include seminars/workshops on rational therapeutics, ORT, herbal

remedies, spiritual growth through clinical practice, pastoral care, management and others.

They also include diocesan and regional level programmes. A total of 315 persons from this

sample participated in these during the past five years, that is, more than one person attended

per institution. During the past five years, there is a gradual increase in the number of

institutions participating per year.

© A large majority i.c., more than 80% found the contents of the programmes useful. They

also felt that the seminars were well conducted.

B. Conventions:

® 32.4% or 132 member institutions have participated in annual conventions during the past

five years, that is, the annual average is 6.5%. The number of persons from the sample who

have attended conventions during these five years are 250. Again more than one person

attends per institution.

The themes of the meetings during the past five years were :

a. Health as if people mattered.

b. Our health care mission - a search for priorities,

19

36

c. Our hospitals - towards greater accountability,

d. Financial administration and project planning,

c. Women in health care.

The majority found the themes useful, the sessions interesting and the conventions in general

well organised.

• The follow up by institutions after conventions is low with an average of 3.5% (15) of

institutions having followed up conventions during each of the past five years.

C. Publications - Health Action:

• 92.9% (378) members received Health Action during 1988-90.

• 66.6% (271) of the sample now subscribe to Health Action. 77.3% of urban, 77.9% of

tribal and 62.3% of rural based institutions subscribe. The difference is statistically

significant.

The large majority (95.5%) felt that the magazine was relevant, and that it was interesting.

A smaller number (4.3%) felt that it was too technical.

On the whole, it was highly appreciated and found to be useful and informative.

D. Central Purchasing Service (CPS):

24.6% (100) institutions from the sample have availed of the services of Central Purchasing

Service at any lime in the past.

(The 5 year lime period was not considered for this Department)

• 42.4% of high bed strength institutions (more than seven beds) and 20.1% of low bed

strength institutions (less than six beds) have availed of the services of Central Purchasing

Service.

50.0% of urban based institutions, 24.5% of rural, and 13.8% of tribal based institutions have

used Central Purchasing Service.

E. Catholic Medical Mission Board (CMMB) Medicines:

53.3% (217) members received CMMB gift supplies during the past five years.

81.6% members felt that the medicines were useful and 16.1% said it was not useful.

However, 41.0% mentioned that the lime period between receiving a consignment of medicines and

the expiry date was very short, while in 20.3% the expiry date was already past when the

consignment was received. In 50.2% cases the time interval was sufficient.

F. Discretionary Fund:

27.5^ of members (112) received grants from the Discretionary Fund during the past five

years.

Six institutions received the funds twice during the past five years.

20

r

37

G. Project Proposals:

During the past 5 years, project proposals from 9.6% (39) member institutions had been

forwarded to funding agencies through CHAI or had been referred to CHAI by the agency.

H. Community Health Department (CHD):

® 8.6'/ (35) member institutions participated in programmes organised by the CHD during the

past 5 years. A total of 150 persons participated in programmes such as orientation seminars,

short term training, CHOPAM course (Community Health Organisation, Planning and

Managcmcnl),workshops, exchange programmes etc.

O 7.4% (30) members were fully aware of the vision of CHD, 91.1% (341) were pa rtially aware,

1.5% (6) were ignorant and 7.4% (30) did not respond to the question.

O 84.8% members (345) said that the CHD vision was relevant to their work, 9.3% (38) felt