TOWARDS A PARADIGM SHIFT A Viewpoint from COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL. Bangalore

Item

- Title

-

TOWARDS A PARADIGM SHIFT A Viewpoint from COMMUNITY

HEALTH CELL. Bangalore - extracted text

-

SOURCE:

LINK Newsletter - Vol.7, No.2, August-September 1988

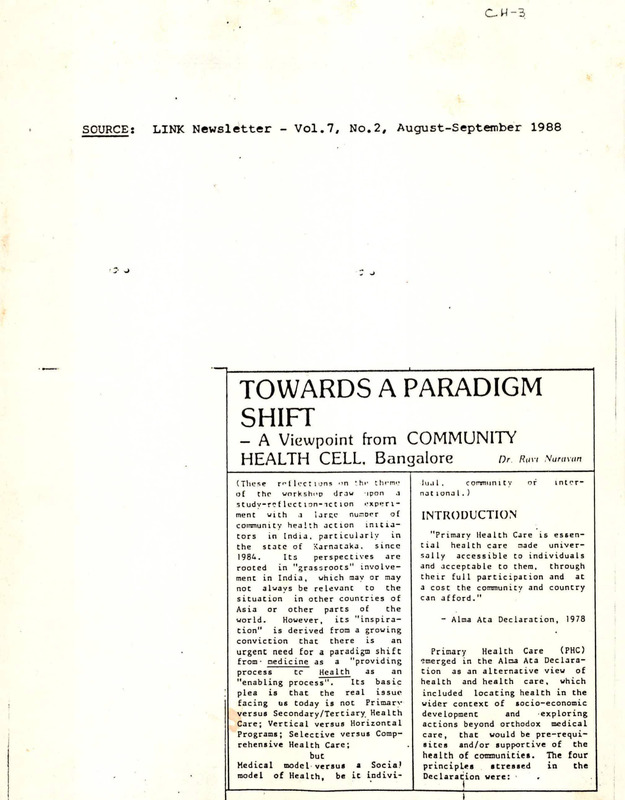

TOWARDS A PARADIGM

SHIFT

— A Viewpoint from COMMUNITY

HEALTH CELL. Bangalore

Dr. Run Nuravan

(These reflections <’n ’hr thrmc

of the worksht’p draw

ipon a

study-reflectlon-iction experi

ment with a large numocr of

community health action initia

tors in India, particularly

in

the state of Karnataka. since

1984.

Its

perspectives are

rooted in "grassroots" involve

ment in India, which may or may

not always be relevant to the

situation in other countries of

Asia or other parts of

the

world.

However,

its "inspira

tion" is derived from a growing

an

conviction that there is

urgent need for a paradigm shift

from • med ic ine as a "providing

as

an

process

tr

_

Heal

__ th

Its basic

"enabling process",

plea is that the real issue

facing us today is not Primary

versus Secondary/Tertiary Health

Care; Vertical versus Horizontal

Programs; Selective versus Comp

rehensive Health Care;

but

Medical model versus a Socia?

model of Health, be it indivi-

lua1.

commonity

not 1ona I .)

of

inter-

INTRODUCTION

’’Primary Health Care is essent ia 1 health care made universal ly accessible to individuals

and acceptable to them,

through

their full participation and at

a cost the community and country

can afford."

- Alma Ata Declaration,

1978

Primary

Health Care

(PHC)

emerged in the Alma Ata Declara

tion as an alternative view of

health and health care, which

included locating health in the

wider context of socio-economic

development

and

exploring

actions beyond orthodox medical

care, that would be pre-requi

sites and/or supportive of the

health of communities. The four

principles

stressed

in

the

Declaration were:

_____ j______________

I

i

1)

2)

3)

4)

Equitable distribution

Community participation

Multisectoral approach

Appropriate technology

Apart from a scries of techno

logical and managerial innova

tions that were considered in

the view of Health Action that

emerged at Alma Ata, probably

the most significant development

was

the

recognition

of

a

"social-process"

dimension in

health care including community

organisation, community partici

pation,

and

a move towards

equity.

Health service provi

ders would be willing now to

appreciate social stratification

in society, conflicts of inte

rests among different strata and

to explore conflict management.

These

were

not

explicitly

delineated but were inherent to

the issues raised in the Decla

ration.

An equally important

fact wan that these perspectives

emerged

from the

pioneering

experience of a large number of

voluntary

agencies and

some

health ministers

ministerfl committed to

the development of a more just

and

equitable

health

care

system.

DISTORTIONS IN I’HC:

In recent years, however,

however, we

have been gradually witnessing,

the world over, a shift of empbasis

from the compr2hrnnive

community oriented exhortat ions

of Alma Ata, to a narrowing down

of

the scope and focus

of

primary health care.

Some of

the distinct trends noticed are:

a)

Primary health care is

becoming a top-down, communityimposed program not a bottom-up

community derived program that

it was meant to be.

b)

Primary health care is

becoming a selective

se

package of

services

not a comprehensive

program

of

locally

evolved

activities.

c)

Primary health care is

getting over-technologised.overmanaged and over-professionalised at the cost of the social

process

dimension

including

community

empowerment

and

demystification.

d)

Primary health care is

being protpoted as a monotonously

similar "model" rather than as a

locally created process appre

ciative of local diversity.

e)

Primary health care is

being "socially marketed"

by

Health Ministries, coerced by

international

health

and

resource

agencies

and

not

socially promoted or proposed by

community

involvement

a

in

participatory management.

Primary health care conf)

cepts have a growing re levance

for

secondary

and

tertiary

levels of health care as well,

However, they are still being

strictly focussed on

primary

levels.

g)

Primary health care i.a

getting medicalised, and industrially

produced al ternat ives

that can be sold or distributed

are being promoted, at the cost

of educational, organisat ionaI ,

awareness-building and empowering approaches.

h)

Primary health care conceptw

and

principles

(even

words) are being coopted by the

t’xiflting medical system which

han a veacrd interest in illhealth.

The deeper meanings of

the principles are lost in this

procesfl.

i)

Primary health care

car<? has

been hi jacked by teaching

coaching and

research institutions and inter

national NCOs in-thc drveloprd

world who arc now promoting "PHC

courses" and "PHC research" as

stepping stones co

to a lucrative

career in International Public

Health and not as a cha 1 lenging

commitment towards a movement

for social justice in health

This distortion and pro

care.

motion of myopia also stems from

the fact that most staff of such

institutions have little or only

peripheral, remote and secondhand

experience of community

based health care in the develo

ping-world situation.

In addi

tion, their own personal expe

rience of the* high-technology,

institutionalised and professio

nally m.lanaged health services of

their own countries is of little

relevance to the task.

j) .Primary health care has

not continued to learn from the

creative experience of voluntary

agencies and health ministries

committedI to social justice! in

health

<

care,

which was its

initial inspiration.

It now

draws sustenance more and imore

from top-down, "management: by

oriented

health

objectives "

projects thrust

on

research

health ministries of developing

countries by international NCOs.

These stress targets, quanti

fiable indicators and measurable

objectives, overlooking process

indicators which may be qualita

tive,

and all the

emerging

participatory management, trai

ning and research skills.

k)

Ln short. Primary Health

Care in 1988 is fast becoming a

caricature of its original philosophy, a captive of an over

medical ised health care system,

a rhetorical slogan coopted by

an inequitous social and economic order, both at the national

and international levels.

For.ty years after the cotnprehensive definition of health by

WHO and ten years after Alma

Ata, is our understanding; of

ive or

health care - compr

otherwise - still where it was

before?

COMMUNITY HEALTH

Is there an Emerging

Alternative?

I.

Cownunity oriented health

action haw been an important

dimension of Indian health plan

ning ninee independence.

The

Primary Health Centre concept,

the national programs, the con

cept of the multipurpose health

worker and community health wor

all were in principle

kers,

and

geared to the planners*

professionaIs * percephealth

need s.

of

community

t ions

However, all the tinkering and

attempted reforms were hampered

by the fact that we had uncriti:ally

adopted a

technology

intensive, institutional model

of

health care from western

industrialised nations, that was

proving to be more and more

inadequate to meet the social

realities

of- a predominantly

rural and agricultural popula

tion.

By 1975, the group on

Medical Education and Support

Manpower, a high-powered commit

tee set up by the Government of

India was constrained to record:

"It is desirable that we take

a

conscious

and

deliberate

decision to abandon this model

and strive to create instead a

viable and economic alternative

suited to our conditions, needs

and aspirations"

- Shrivastava Report 1975

2.

In the meanwhile since the

23

■

X'

late sixties, a large number of

initiatives and projects outside

the Government system were esta

blished

by

individuals

and

groups keen to adapt health care

to our social realities. Broadly

classified as voluntary agen

cies, (now NGOs

NGOs),

), all of them

started with illness care, but

moved on to a whole range of

activities in health and develo

pment.

Soon, ongoing community

development projects and commu

nity education experiments also

began to add health dimensions

to their actions. As the number

increased, networking and trai

ning efforts were also

ini

tiated. Soon health issues began

to feature on the agenda of

people-based movements - be they

environmental or around women's,

dalit's or trade union issues.

This upsurge was a spontaneous

development and not an organised

pre-planned movement.

3.

From 1984, a team of us

have been studying this process

through participatory

reflec

tions and presently a much more

detailed report is in circula

tion among health action initia

tors in India for participatory

and collective comment.

From

these reflections, liowwer, we

have begun t«> ♦ivoIvh a svrius <>t

principle* and issues th.it arc

emerging from the successes and

failures, strength* and weaknvssen

of dll these

community

health action initiators, and we

list some of them out here:

The broad definition that

4».

has emerged of community heal th

itself, initially, is

process of enabling people

to exercise collectively their

to their

responsibility

own

health and to demand health as

their right, and involves the

increasing of the individual,

family and community autonomy

over health and over organisa

tions,

means,

opportunities,

knowledge, skills and supportive

structures

that make

health

possible**

5. The next set of issues are

components of community health

action wh'ich are very similar to

those outlined in the Alma Ata

declaration.

These

being

attempts to:

i

Integrate Health with develop*

me nt programs,

Integrate curative with preve-

I

■!

24

Experiment with low-cost ,ef fective, appropriate technology,

v) Recognising that community

health needs community-building

efforts through group work, pro

moting cooperative efforts and

celebrating collectively;

indigenous

Involve

local,

health knowledge, resources and

personne1,

vi)

Confronting the super

structure of medicalised health

delivery system to become

health

more poor people oriented,

more connnunity oriented,

more soc io-epidemiologicaIJy

oriented

more democratic,

more accountable

ntive;

promotive

rehabilitative activities,

Train village-based

workers,

and

Initiate,

support community

organisations like youth clubs,

farmers clubs and mothers clubs,

Increase community participa

tion in all aspects of health

planning and management,

Generate community support by

mobilising financial,

labour,

skills and manpower resources.

These abov<? dimensions could

broadly be described as technological and managerial innova

tiona, which, in principle could

also become part of top-down

vertical programs, though they

reach their full potential in

♦*vol ved

community

based and

programs.

Ilov<’vt,r. in our rvt Ivc.inothrr

we discovered

set ui is such and actions

could b<» broadly c lass I-*

tied as "social process dimens ion®'* which w«*re beginning Co

a

be seriously taken up by

programs.

growing

number of

These were:

6.

t ions

whole

which

Organisat ion of noni)

forma I , informal, 'demyst i fying

consclent is ing 'educat ion

and

for health’ programs;

ii)

Initiating a democratic,

decentralised, participatory and

non-hierarchica 1 value-system in

the

interactions within

the

health team and in the health

team-consuunity interactions;

iii) Recognising conflicts of

interests and social tensions in

the existing inequitous society

and initiating action to orga

nise,involve all those who do

at

not/cannot

participate

present;

iv)

Questioning

overQuest ioning the

medicalised

value system

of

health care and training insti

tutions and challenging these

within the health tenia',- learning

new health oriented values;

Recognising the cross

vii)

cultural conflicts inherent . in

transplanting a Western Medical

model on a non-western culture

and hence exploring integration

with other medical cultures and

systems in a spirit of dialogue.

Recognising that comviii)

munity health efforts withi the

above principles and philosophy

cannot be just

a spec iality;

a professional discipline;

a technology fix;

of actions;

a package

,

a project of mvaaurnbl* activi

ties;

but han to transform itself to

a new vision of health care;

a new v.ilue-orientat ion in

action and learning;

a movement, not a project;

a means, nut an end

Are these

alternat ive?

the

axioms

of an

THE PARADIGM SHIFT

We have suggested a 'paradigm

shift' from a Medical model of

health to a social mode 1 of

health as the basic plea of this

paper. From all the perceptions

that have evolved in the action

reflections in these past years,

we see this as the crucial and

probably

the key

perceptual

change that has begun to take

place in our own perceptions,

values, definitions, indicators,

methodologies

and

plans

of

action.

In table I we propose a short

list of the differences between

these

two models.

«

7

Recently we received a letter of

concern from David Werner and

his colleagues at the Hesperian

They were distresFoundat ion.

sed at the top-down approach

being used to promote ORT as

They were keen to

part of PHC.

help evolve a more integrated,

decentra 1ised, effective peopleoriented approach to ORT. David

sent a chart comparing the two

strategies to us.

It was a

the

further

indication

of

growing awareness of the two

of

approaches to health care,

the tendency of technology to be

equally people-debilitating as

it can be people-empowering.

TABLEI

PARADIGM SHIFT

HEALTH

Medical Model

Ind ividua1

Patient

Disease

Providing

Drugs & Technology

to

to

to

to

to

to

Predominantly physical &

mental

Professional control over

skills and knowledge

Intracellular research

Patient as beneficiary and

consumer

Mystifying knowledge

to

to

to

to

to

Social Model

Community

Persons/people

Positive living

Enab 1ing/empowering

Knowledge & social

processes

Physical/Mental/Soc ia1

Ecological/Political

Transfer of skills &

knowledge to lay people

Social Research

Patient as participant

in process

Demystifying knowledge

and promoting autonomy

the

same

We

believe

that

d ichotomy/divergence exists in

Approaches to training, manage

ment and research in emerging

health care.

I

1

TWO STRATEGIES FOR ORT PROGRAMS

AN APPROACH TO

DIALOGUE

Siritfqy of nta I! a UmiTl

Iftler1i0A4i

V."

training, evaluaManagement,

t ion and research approaches 1 n

they

our health care system aa

exist

today reflect moat

often

the dominant. orthodox, me d 1 C a I

Thia medical orirnviewpoint,

their

cation

io built

into

aaaumptions.

incurpret at ion o(

facts,

under it and ing of comm.ini t y rea | 11 im ,

priority 4«»d

methodologies.

4

ic«MAtea

4t p4,t Of

itltC

measure

enabling

oaoiI'oaI

<•41 • IM

•'•4l’h,

jop-/

ItA 1 •(, i

t f n, txxJf '

M«4lth •lAtllry,

ino n^ieft

v ■ yA

A *4 * f

<A4AA«I| "*' ■ ‘

..4w4r>A«tl *4111*1

■ iiVAAlAltf p4'< >'. < P4( 1 0* *ot*4*l,

popull* 0*14* I / 4t I <1*1 , ’'4414*1,

1444*4*1, <.*114*4*1

•

<. QT**" • t

"J.! it.1?*!--.

"■/111 xector 1 4 I

PO»K.

' J* .

----------

—

Xf'QOl

How <t M pr^tenlf*;

4t > ewoic’ne Ito flC’l'titf

ICCfPtinte eno utfI

41 4 fooo or •jr|A» (to OfWftt’ff 4A0

pro^otf vAOfritfAfllng of COntfjt

Annul I CMt*

•-increttet e»erjr /f«r -jve to

growing Of«4«<l ifor P4l«et»l

--or trinsferreo »0 C0Mu«wri

tftrouqn co^wertxl $iif of ptcaets

fairly conitint for f 1'31 f?w rfir$t

tn*n ripirjij Mclmei i» •oucit’orii

inffjt»w"t

off mo 1014’10 t*T

pricticet &fcor>e "tonwon mowfOOf’

[»4Iwition

..Sifety <jf CBS ■•tfos c-4$»o n«inly

on content of forw.,.* 4na iCCwMcy of

pr«04r’n9 solution

— inoiCJtors of luccvil.

-nueo*'- jf paciets <J»ttrxou’eo

.Av004r Of 5400 If «no t«0w now

to "1 * C’S Correct|y

• rffluction in cm Io nortility

. .-rtliince on ruro <Mt4.

lUtHUCI, controller ttjfliei

— 14fety of ■Wt"041 54141 -cv c«

10C14I *4C:i*1 4»4'l40ll’ty 4*0

co*it*4'*t» of tupply, ;eoo 4j •o,:i

4*4 4tt1’.U04l

--'"0iC4ti*i of tuccei*

-*>ow n4"» ceotile unoe*ltl*4

concept 4*0 Dfoceii

• now R4ny peooif uit CAT ’* ! -« ■

1 t*at i»e-n to .on

i

|

-'"04CI on cii loecVt, faatl'.fi'

4*0 c<x»Ki"ity 1 well-oei*9

--*eii4*ce of peooiei '»oretiicni

.’*<3 C3ier»411 9*1.

9041

1 •-•orewo 3u4i'’y of

and

Do we

empowerment dimensions,

have an understanding of such

indicators yet?

These will be some of the issues

that are going to emerge in any

discussion thjit seeks to explore

the issue "vertical

interven

tions vs CBHC".

, .A.^e ma

tMqif or ifriii

• ■f.iTnMli 4440t»4 11) lOCH

/•IQurret.

• •IOC 14 I 'Mritl1*1

■ .|0<l|l mom I I/4< l QA '70U’"9

POHUCU"* 4"0 <»i«oritiei 10

profit It )

To

do justice to the new

ve

community health approach

would have to explore process

indicators which may be qualita

to

■Ateqrjlrd into <OAQfeArAt1.f ;

u«X tne X-<,.4

IIA 1

proqrjm,

N1IA f«XUl 4*4 IA.«H«WA<

■ >9* prnclvc t 1 , l«4Auf4Ctv’4 4"4

4 11 < r I SwlUni

rf

How justified would we be

orthodox

indicators such

as

mortality and morbidity were the

only ones used as the criteria

CBHC

evaluation

of

for

are

when

we

especia I ly

increasingly recognising it as

a social process at base.

tive,

il *<4

arq.,’

*4 1A t ypwt of Olil oriMXIKO

. . p 4 < » « < I “f <l»* 14 Hl |JlM<0t4

04l«4I

• •*<4A44r4l l»4 f'>r*.l4

in

How justified would wr b**

imposing

thewe approaches

to

study/learn/undi’ratand the new

alternative

‘social model' o I

health car" that

11 emerging

today out of the experience of

numerous community based health

care programs m Asia.

I

nf

1 na Din

Fol 1:1 cal Strategy:

tueoort

uSin? -m.-,;.-,

lirrn;-.A4-n 4*0 fp’.tll’f

r-nner 1

jnc T4t» p*o©i« :<•>.*.!«-<? XI

art. »•■?*»* U0»5'->»n- • ... -

References:

I. The Alma Ata Declaration

2. Cccrnunity Health: The Search

| "■n rooulf y,ccort j j

•.nil

tr0 f co*#' XfOp.e.

"♦•P’nc tn«-» tp see 4W

eu

cepenoent. -o** te

-*• • .-t

for

an

Alternative

Process

(Report of the Study-ReflectionAction Experiment of Cooraunity

Health Cell, Bangalore.

25

<

J

- Media

CH-3.pdf

CH-3.pdf

Position: 186 (50 views)