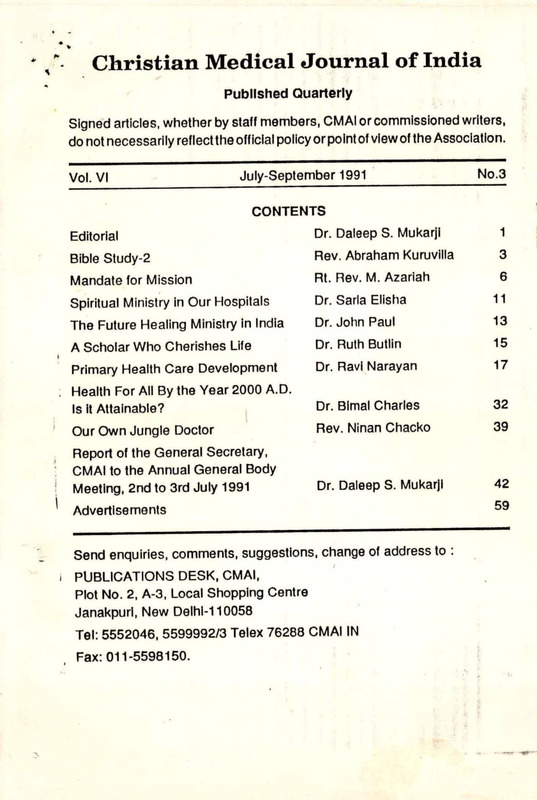

Christian Medical Journal of India

Item

- Title

- Christian Medical Journal of India

- extracted text

-

Christian Medical Journal of India

*

Published Quarterly

Signed articles, whether by staff members, CM Al or commissioned writers,

do not necessarily reflect the official policy or point of view of the Association.

Vol. VI

July-September 1991

No.3

CONTENTS

i

I'

Editorial

Dr. Daleep S. Mukarjl

1

Bible Study-2

Rev. Abraham Kuruvilla

3

Mandate for Mission

Rt. Rev. M. Azariah

6

Spiritual Ministry in Our Hospitals

Dr. Sarla Elisha

11

The Future Healing Ministry in India

Dr. John Paul

13

A Scholar Who Cherishes Life

Dr. Ruth Butlin

15

Primary Health Care Development

Dr. Ravi Narayan

17

. Health For All By the Year 2000 A.D.

Is it Attainable?

Dr. Blmal Charles

32

Our Own Jungle Doctor

Rev. Ninan Chacko

39

Report of the General Secretary,

CMAI to the Annual General Body

Meeting, 2nd to 3rd July 1991

Advertisements

Dr. Daleep S. Mukarjl

42

Send enquiries, comments, suggestions, change of address to :

I PUBLICATIONS DESK, CMAI,

Plot No. 2, A-3, Local Shopping Centre

Janakpurl, New Delhi-110058

Tel: 5552046, 5599992/3 Telex 76288 CMAI IN

Fax:011-5598150.

59

c^-i-

Primary Health Care

System Development

Learning from the NGO Experience

in Community Health

1. THE HEALTH POLICY EXHORTATION — RECOGNISING

THE NGO

The National Health Policy 1982-84 is a comprehensive statement

on the goals and intent of the Government on all aspects of health care

delivery and manpower education in the light of the national commitment

to Health For All by 2000 A.D.

One of the significant departures In this policy statement from the

planning process and framework of previous decades is the recognition

and importance given to the ‘Voluntary Organisations’—a large network

of health and development organisations working all over the country at

the grass-roots level.

The policy emphasises this 'new partnership’ In at least four different

paragraphs.

The recognition and the comprehensive dimensions of collaboration

are unambigously worded (Ref. National Health Policy, 1983).

To reiterate, they Include :

i)

Utilising the services of NGOs

ii)

Intermeshing NGO services with governmental efforts

Hi)

Encouraging increased Investment by NGOs

lv)

Offering financial, logistical and technical support to NGOs

V)

Assist in enlarger ent of services by NGOs.

17

ft

I

O

1

2.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE NGOs IN HEALTH CARE

There are estimated to be over 5000 NGOs involved in Health Care

all over the country (recent estimates are much higher). Quite a large

percentage of these are situated in the six states of Gujarat, Maharashtra,

Tamilnadu, Andhra, Kerala and Karnataka. A smaller number are available

in most other states.

The hallmark of the Indian NGO Health Action Initiators are the

diversity of approaches, structure, methodology and ideology. A special

issue of Health Action (a magazine of HAFA Trust. Secunderabad)

highlights some of this diversity and presents an overview of the situation

in the NGO sector.

exploring certain social dimensions of health work which are grossly

neglected or unrecognised in governmental efforts. In fact it is this

contribution that can be considered most significant to the Primary Health

Care movement.

I

These dimensions are :

£ The links with a socio-political process.

]

* The commitment to individual and community awareness building

and generation of greater autonomy.

i

* The commitment to a participatory decision making process within

the health team, and within the community & health team interactions.

The process of ‘community building’, including increasing the participa

tion of those who do not/cannot participate at present.

The NGO health project ranges from alternative service provider at

micro level to alternative trainer, developer, issue raiser, awareness builder,

social activist, networker, health educator and community organiser.

The acceptance of conflicts of interests within the community.

The confrontation of various factors in the ‘medical model’ of health

care including the over medicalisation of health, over professionalisation of skill and knowledge, and the over emphasis on the ‘physical

dimension’ of health.

Due to the special nature and peculiar history c. their development

in the country, the NGO health project is marked by their diversity of

approaches and flexibility of options at the micro level.

I

The quest for medical pluralism.

Most of them however provide a combination of two or more of the

following types of services:

The reorientation process required to modify the existing super

structure of health services and training institutions to meet the larger

social goals of health care.

Appropriate Technology for Health.

Community Organisation and Participation in Health of Mahila Mandal,

Youth and Farmer Clubs.

I

The increasing commitment to accountability and medical audit.

The NGOs are brought together by various coordinating and

networking organisations like Voluntary Health Association of India (New

Delhi and state leve branches), Catholic Hospital Association of India

(Secunderabad), Christian Medical Association of India (New Delhi), All

India Drug Action Network (New Delhi), Medico Friend Circle (Bombay)

and so on. Through meetings and their bulletins/journals they maintain

constant interaction and dialogue between these groups.

& Community Based Village Health Workers.

Involvement of Traditional Healers, Dais and Indigenous Systems.

A

Education for Health.

Health with Integrated Development.

& Community Support to ? -alth Care—financia?,resources.

While these describe the technical and m. ;agerial aspects of the

NGO action they are increasingly characterised by their commitment to

1

19

18

1

?

5

3.

SOME CRITICAL ISSUES

The Community Health Cell is a study reflection action experiment

that has been learning from the micro level NGO experience In India

to evolve and explore macro level contributions to Health Policy and

PHC System Development.

I would like to present seven key policy formulations that the macro

health care delivery system, mostly under the Government of India,

can consider adopting for the next decade so that Health for All

becomes a much closer reality.

A. People as Participants and not as Beneficiaries

People do not mean only the formal leaders but a host of other

Informal sections including women, youth, children, local healers,

farmers, teachers and so on.

Care should be taken to focus on those marginalised,

underprivileged groups who do not participate in decision making

in the present social structure.

More than anything else, this attitudinal shift calls for a courageous

shift In present day beaurocratic/technocratic planning.

r

Informal awareness building, discussions, non-formal education,

community organisation and mobilisation, community building

activities and mobilisation of local skills, resources, Ideas and

Initiatives must take precedence over top-down centrally managed

distribution systems.

In concrete terms this will mean a change In emphasis from e.g.,

— providing taps or tube wells to ensuring their maintenance;

The NGO experience has shown time and again, that people can

participate as planners in programme development and

organisation and should not continue to be considered as

beneficiaries of a top down, centrally planned and heirarchically,

compartmentalised, health programme—be it from the national

or state level.

I

There has to be a shift in emphasis to enabllng/empowering

people to make decisions and carry them out in matters of health,

be they at an individual or collective/communlty level.

B. Focus of Service on Enabling and Empowering rather than

Just Providing and Distributing

For too long health programmes have been seen as distribution

programmes of food, vitamins, vaccines, contraceptives or drugs.

The focus has been on providing, distributing, record keeping,

accounting, supplying etc.

20

— from providing vitamin supplements to encouraging vegetable

gardens and low cost local nutrition mixes;

— from antidiarhoeals to home based ORT mixtures;

— from medical check ups to child to child, and child to home

school based health programmes and so on.

Training ‘tap turners off’ and not ‘floor moppers’

Much of present day focus and training of health manpower is on

curative skills—drugs, dispensing and diagnosing and not on

community awareness building or mobilisation.

The NGO community health trainers have made a significant

contribution to preparing manuals and organising courses that

shift emphasis so that health action begins to explore and support

action at the deeper roots of ill health—at the community and

societal level and not on a superficial, individual, physical level.

The shift In skills is not only from curative to preventive and

promotlve but from Individual to collective, from providing to

enabling and so on.

Case studies, field experiences, simulation games, small group

discussions and aliernatlve pedagogy have been developed to

21

-W-

11

bring this change in the trainee's attitudes and prepare him for

more meaningful roles.

The overall pedagogical shift is from working for people to working

with and through people.

Most health care delivery systems today are hierarchical,

authoritarian with lot of ideas, decisions, targets, going down the

system but little feedback going upwards. Unless these top down

authoritarian systems change to a more participatory management

process, giving all team members due importance and share in

decision making and credit, PHC systems will just not deliver the

goods. The medicalised hospital system with the glorified role of

the specialist is at the heart of this problem and since most

health workers including doctors and nurses continue to be trained

in this setting—team work concept at the community level has a

long way to go. But change it must.

II

!

D. Supervision — From Fault Finding to Problem Solving

Any meaningful action programme at the field level needs an

effective supervision process. However, this has today become,

especially in the government health system a target setting, fault

finding system amounting to a sort of rigorous policing by superiors

over their juniors, all the way down the ladder. The average

monthly Primary Health Care meeting is typical of this situation.

F.

Supervision can be a very creative exercise and from the NGO

experience we know that to bo effective it should be supportive

and basically a problem solving exercise. Team members get

together regularly to look at their actions and results in a mutually

supportive way with the more senior members of the team

exploring ways of getting over problems encountered by junior

staff. The ethos is one of dialogue and the supervision process

looks at strengths and weaknesses as well as identifies

opportunities and threats.

There has been a preoccupation in all our education and

monitoring programmes with quantitative indicators and measures

of service distribution e.g. no. of vaccines given, no. of condoms

or contraceptives distributed, etc.

Apart from the fact that these have been consistently subjected

to inflation, and cooking up’ due to the stresses and pressures

of top down targets, these do not give any indication of the

processes and qualitative changes that need to take place if the

Health For All goal has to be reached.

This attitudinal change is an urgent necessity in the present

system.

E. Management

Management

Monitoring and Evaluation — From Quantitative Project

Indicators to Qi.?alitative Process Indicators

There is a need to shift to qualitative and quality indicators as

well as indications of equity and social processes e.g.

From Authoritarianism to Participatory

— From immunizations given to fully immunized children.

— From condoms distributed to couples seeking advice.

Building a Primary Health Care System which is responsive to

the needs of the large majority of people, with their participation,

is basically a democratic process which needs patience, faith

and enthusiasm. If health, workers at all levels ha j to develop

these basic attitudes, they need to function

a system that

considers them as ‘participants’ and ‘key components’ and not

just as ‘cogs in a wheel’.

22

— From health talks given to the extent of ideas and suggestions

given by the people in programme development.

I

!

— From numbers of materials distributed to numbers of people

made aware or enabled to make decisions regarding health.

— From what the Primary Health Care doctors, statisticians

23

or professional programme evaluators feel about the programme

to what people and grassroot level health workers feel about

the programme and so on.

THE PARADIGM SHIFT

PEOPLE

BENEFICIARIES

PARTICIPANTS

SERVICES

PROVIDING

ENABLING/EMPOWERING

The present focus of much of our research is at the Intracellular,

moleculor, biological level with the hope that we will discover

new drugs or vaccines that will cure or prevent some of our

health problems.

HEALTH WORKER

FLOOR MOPPERS -♦TAP TURNERS OFF

SUPERVISION

FAULT FINDING

PROBLEM SOLVING

MANAGEMENT

AUTHORITARIAN

PARTICIPATORY

There Is need to shift this emphasis to ‘societal or community’

research that will seek to determine, describe and understand

the larger societal forces that make ‘health’ an Impossible goal

for most people.

EVALUATION/

QUANTITATIVE/

QUALITATIVE/

MONITORING

PROJECT

PROCESS

RESEARCH

INTRACELLULAR -♦

COMMUNITY/SOCIETAL

What are these factors that prevent large majorities of our people

from getting the knowledge, skills, attitudes, means, opportunities

or services that make health possible?

All health planners, policy makers, administrators, educators, service

providers and evaluators need to appreciate this shift.

G. From Intracellular Research to Baloonlst/Socletal Research

We now know that Inadequate water supply is at the root of the

diarrhoea problem; inadequate land reform at the root of the

malnutrition problem; caste and corrimunal consideration prevent

access of large numbers of people to health services; class

determines access to education and wage Income; Indebtedness

as well as government liquor policy at the root of the alcohol

problem and so on.

4.

The entire group of regional review meetings and the previous

meetings of the past decade have seen Primary Health Care System

Development In a very myopic fashion.

|

As these deeper links are understood, action plans will emerge

which will strike at the larger issues and not focus only on

superficial programmes.

I '

They have focussed all along on infrastructure, manpower, materials,

logistics and educational materials and rightly so because they are the

basis of public health programmes.

But they have missed an Important dimension of Primary Health

Care System Development. Primary Health Care can never be a reality

In this country If PHC is provided by professionals, technical/beaurocratlo—

from the top.

The Paradigm Shift

These seven dimensions represent a major paradigm shift in our

understanding of Health and Primary Health Care and these are crucial

to the goals of Health For All 2000.

FROM SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT TO AWARENESS BUILDING

(DEMAND/CREATION)

!

Primary Health Care has to be a demand from the grassroots—a

demand from an aware and health conscious people. We have failed In

our understanding of the need and necessity of planning for this dimension.

Unless health Is seen as a right and a responsibility, unless people and

24

25

communities begin to have a vested interest in Health and unless Health

becomes a demand for the common people, all our efforts will fail.

Health Education to Education for Health

II

Awareness building in Health or the term Education for Health used

in this paper is very different from what we know as. Health Education,

which has become a euphemism for telling people the dos and don’ts of

Health in a sort of passive, one way, top down process. Education for

Health is a more creative, liberating process exploring the roots of ill

health with people through informal group discussions and a host of two-

It is therefore necessary to recognise that Primary Health Care System

Development means both

Services

Provision

V o

(Supply)

[

Education for

Health

I

This will mean that we will need to face up to some new questions:

Are we ready to discuss how to make health and health care

important on this country’s political agenda?

iii) Are we willing to plan.to generate health as a people’s science

movement involving science educators, teachers, youth groups

media people, folk and modern communicators and so on?

z-><4i<-»

_ —i —

puippoii y , oiicci iiicdiic, u ckjuioi icil ikJirx dl IO

I

More than any other action I think the NGOs in Health Care and

Development have skills, resources, ideas and initiative in this direction.

If only health planners and health policy makers are willing to see this

V4I 11-i more and more wr

IVUIlll NGOs see this

UIIO CiO

UH WiyClll

need and

of the Health

as an

urgent

1 necessity, a major break-through could be made.

■

IIUWV*

IIIWIIZ

iriv'ikz

iiivr

I

M

Awareness building is not new. It has been mentioned differently in

policy statements. (Ref. National Health Policy, 1982, and National

Education Policy, 1986).

iv) Are we willing to plan how to generate health as a mass move

ment from below, involving all sections of the people—their

leaders, political parties, health, social & development activists,

trade unions, women’s groups, dalit and marginalised groups,

workers and so on?

The 1990s call for a major shift in our efforts and deliberations to this

important aspect of system development, otherwise our efforts will remain

as unimportant, peripheral, anaemic and ineffective as they continue to

be, inspite of all our efforts.

inTArnr’Iii ir\

, nnuiuuii»<. i>n.uia

and jathas so that, not only are people able to understand what causes

or maintains their ill health, but what means, processes and initiatives’are

available or need to be sought to build health, both individually and

collectively. For example, while teaching about water borne diseases, the

stress on the need to have good personal hygiene and to drink boiled

water is an example ol orthodox health education. On the other hand,

i initiating a discovery process by which water availability and access are

explored in a community and the group is motivated to take collective

action to improve the situation in the community through village based

action or pressure on the authorities is an example of the new emphasis.

(Demand)

ii) Are we willing to discuss how to infiltrate the entire educational

system of this country—formal and informal, professional,

technical or vocational with the message of individual and

community health?

urow

The emphasis has, however, unfortunately been on a passive, top

down education process thrust on people rather than an active grass

roots and upward extending process.

1

The purpose to highlight it here is to emphasise that this new emphasis

.1 on education for health must be given, and that this crucial area must

I receive concerted attention and action.

■»

27

26

?

■

<

will continue to be the main service In quantitative terms. This cannot

and should not be Ignored.

5. GOVERNMENT — NGO COLLABORATION IN THE 1990s

Having recognised the Health NGO as a potential partner In the

health policy statement In 1982, the experience of the last 8 years has

shown some important but disturbing trends In the area of Govt.—NGO

collaboration in Health Care. I would like to highlight them, raise some

points of caution and explore some alternative approaches.

4.

Linked to the above, there is an Increasing tendency to belittle or

denigrate the government system and plead about its inabilities or

built In problem or hs resistance to change. This leads to two problems

at the planning level. The first is, that reforming the government

system is not adequately worked upon. The second Is that under the

garb of NGO Involvement there is a definite move towards privatisation

and involvement of the profit oriented corporate sector In health care.

Trends

1.

Recognition as service providers only

The government continues to see NGOs as only alternative service

providers and at best, alternative family planners or Immunises. Their

skills in providing other aspects of the package of health programmes

are still not seen. Their additional abilities as trainers, evaluators,

issue raisers, awareness builders Is still unrecognised. In many states,for planners, NGOs still mean Rotary or Lions Clubs or at best the

Family Planning Association of India or a Mission Hospital. The Indian

NGO today Is a much more diverse and creative species and needs

to be understood as such.

2.

Government systems can change if all those at the helm of affairs

are committed and rightly oriented. There are innumerable.examples

all over the country and these need to be highlighted.

■-

Pressures on scaling up

There is a tendency to expect NGOs who have shown their abilities

at the micro level to scale up their efforts to larger and larger levels

to make up for the deficiencies and Inadequacies of government 5.,

programmes at the periphery. The NGO’s strength Iles In its creative

abilities at the micro level, allowing for qualitative Inputs and processes.

Pressures to expand will often make them as ineffective or :

bureaucratic as the larger system.

’I

3.

Glorifying NGO & denigrating Govt, sector

Due to the inadequacies and failures of the existing health care

delivery system and the large unmet needs, there Is a growing

tendency to 'glorify' or 'romanticise' the NGO and have unrealistic

expectations of this sector. This sector Is small and primarily qualitative ;

in Its contribution. For a long time to come, the government service

i-

28

Privatisation under the garb of NGO Involvement

i1

While the private sector may have Its role in providing some aspects

of health care—health services are basically a state responsibility

and the tax payer must get basic health care for his contribution.

Profit orientation of the private sector means that the consumer Is

always paying more than Is necessary and this must be recognised.

It is at least Important not to confuse the NGO voluntary sector with

the private sector to begin with, and to deal with them rather differently

on policy Issues.

Community participation

Synonyms

and NGO Involvement

are

not

Finally, at all levels community participation is often seen as being

equivalent to Involving NGOs. This is neither synonymous nor realistic.

NGOs are definitely closer to people, more responsive to the local

situation and function under lesser, top down controls and are hence

more creative. But they too are trying to explore real Involvement of

people In their own initiatives and processes and are meeting with

varying degrees of success. Not all NGOs have succeeded In eliciting

meaningful participation. If these terms are not confused, then we ■

29

will at least see community participation as a process that can be

Primary Health Care System Development Is the backbone of this

Initiated In any system, Government or NGO.

planning and management exercise.

What is most crucially required is the development of a new culture |

The 1980s have seen a preoccupation with infrastructure development,

in health services and planning and this Is highlighted by the following logistics, supplies and manpower development and statistical exercises,

aspects:

valid and Invalid, Interspersed with a large dose of populist rhetoric

I) Information transfer and awareness building programmes for the ancJ P°,,cy statements.

PeoP,e|

The 1990s must see a paradigm shift In attitudes and efforts so that

li) Reorientation programmes for government staff at all levels about Primary Health Care Is an enabling, empowering process and not Just a

the concept of people as ‘participants’ rather than as ‘beneficiaries’. Jmere provision of services and Infrastructure. A new spirit and a qualitative

ill) Monitoring and record keeping systems that are Interactive and change In all our efforts are required. The NGO experience In the country

qualitative and build on feedback from people and grass roots Is diverse and creative. Major lessons can be learnt from studying this

wealth of micro level experience. There Is need to Incorporate these

level staff who are closer to them.

[Ideas and processes into all our efforts In Primary Health Care System

iv) Increasing involvement of voluntary agencies/NGOs in the role of

■Development—governmental or non-governmental. This Is the challenge

monitors, evaluators, Issue raisers, demand creators and trainers,

ibefore us.

not just as programme implementors.

v) Positive discrimination towards those groups who do not partici- ^pr. Ravi Narayan, Coordinator, Community Health Cell, Bangalore.

pate In local decision making processes.

fThe original article has 6 pages of cartoons, references and

vl) Health/Educatlon efforts to strengthen the community building

appendices. All those Interested could request these from the

aspects.

Community Health Cell, 326, V main, I Block, Koramangala,

vli) A move away from top down, centralised models to regional lBangalor^S60034.

planning that reflects local soclo-economlc-politlcal-cultural |

realities.

I

viii) Increasing acceptance of diversity of options and flexibility of |

approaches.

Many of these have been highlighted earlier. Concerted political will and

professional will Is necessary in the 1990s to bring this major attitudinal

change.

11

CONCLUSION—THE CHALLENGES AHEAD

There are hardly 110 months ahead to reach the goal of HFA 2000,

whether comprehensively or selectively.

i

31

30

i

T-

- Media

CH-10.pdf

CH-10.pdf

Position: 199 (62 views)