Health for the Millions, Vol. 12, No. 5&6, Oct. - Dec. 1986

Item

- Title

- Health for the Millions, Vol. 12, No. 5&6, Oct. - Dec. 1986

- extracted text

-

HEALTH FOR THE MILLIONS

VOLUNTARY HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF INDIA

October-December, 1986

Volume XII

No. 5 & 6

Information is not communication. Information is,only potential communication. We communicate this in

formation using various media. Our messages and the media we choose have cultural connotations and reflect

our social environment’s beliefs, taboos, prejudices and preferences. In this issue of Health for the Millions,

we make an attempt to define various commonly used media, along with their potential and limitations.

This year saw a bloodless revolution in the Philippines—a revolution energized, sustained and supported

by “Veritas", the Catholic Radio and its news magazine. For this effort, Cardinal Sin, Archbishop of Manila,

was honoured at the 14th Congress of the Union Catholique Internationale de la Presse (UCIP) at Vigyan Bhavan,

New Delhi on 22nd October. His key note address, explaining the role of communication for political change,

appeal's on p. 21.

November '86 saw a unique development mela at Chakradharpur, Bihar. Birsa mela is held in the memory

of Birsa Munda, a tribal freedom fighter who was martyred in 1900. The mela was organised Jointly by an

enthusiastic IAS Officer and the tribal youth of Singhbhum district, in an attempt to demystify new technologies

for development. The Bihar VHA found this a unique opportunity for massive health education. Some of the

learnings irom this experience are shared on p. 18.

1986 has witnessed many changes in VHAI's existence: the inauguration of the new VHAI building, the

sad demise of Fr. James S. Tong, the appointment of Shri Alok Mukhopadhyay as Executive Director (Designate)

and the VHAI renewal where the staff and board of VHAI rededicated themselves to making health a reality

for all through people's participation.

For some time now, we have felt the need to enlarge the scope of Health for the Millions. We have discussed

this matter within VHAI and outside. The general feeling is that we expand Health for the Millions to cover

a particular theme in each issue: we incorporate a section covering national and international news on primary

health care and finally, initiate a debate on various aspects of primary health care around controversial issues.

We hope that the third section will enable the readers to participate in Health for the Millions more effectively.

Before we finalise this format we would like to have your views so that we can match your expectation.

Please fill in the attached suggestion card and send it to us soon. We are suspending the publication of Health

for the Millions till March to get all set for the new format from April. From April onwards, our magazine will

have 36 pages, a better get-up and layout and hopefully, vastly improved contents, .

Please do not forget to send your suggestion card.

With very best wishes for 1987 from all of us at VHAI!

Editor

CONTENTS

Communication for Development

Radio in Support of Mother and Child Health

As if People Don't Matter Anymore

Folk and Mass Media

Fair Communication: Reflections on Birsa Mela

Communication, Culture, Religion: The Philippine Experience

Sharing for Action: A Report on ESPOM II

1

io

14

16

18

21

25

This issue of Health for the Millions has been compiled and edited by Radha Holla Bhar, for Voluntary Health Association of India,

40. Institutional Area (near Qutab Hotel), New Delhi-110016. Designed and Produced by Parallel Lines Editorial Agencv E-8

Kalkaji, New Delhi-110019.

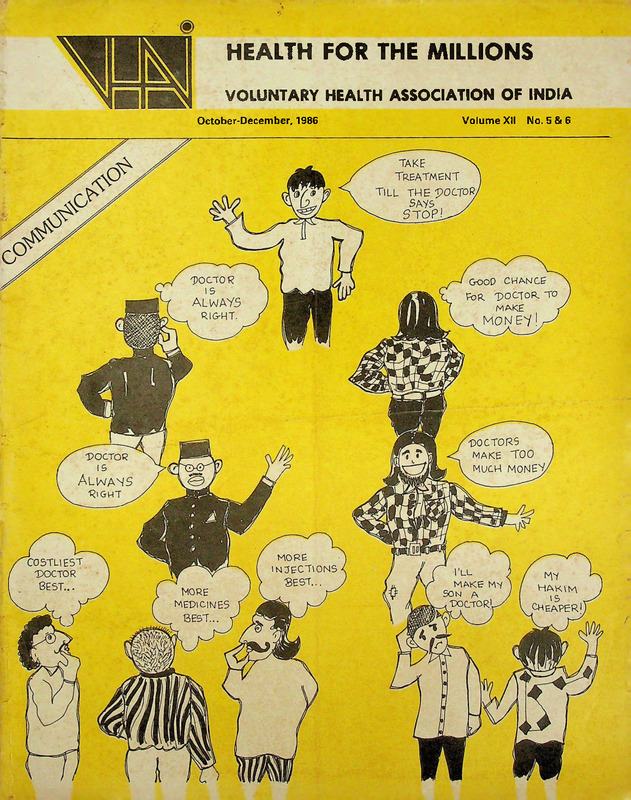

COMMUNICATING

FOR DEVELOPMENT

Communication is an essential

part of education. Education can

never be neutral. Education is a tool

that helps either reinforce existing

values or questions them with the

idea of ‘liberation’. In the latter form,

it sharpens people’s critical facilities.

Health education is again a

political tool for advocating change

by empowering people to demand

their rights by making them aware

of the nature of exploitation that

they suffer: this is ‘liberating’ educa

tion. Or it can suggest means of

symptomatic relief without facing

the real causes of ill health: this is

‘progressive’ education.

Health education, to be truly effec

tive in conscientizing people, does

not involve any readymade

packages. Mere transfer of informa

tion is not education. Education has

to be action-oriented. Such educa

tion assumes that the educator and

the learner share and exchange their

roles in the process of increasing

their knowledge together. Health

education involves the individual.

the community and their relation to

each other, in the process of problem

solving. So it involves community

systems—social, economic, political

and religious.

Who is a Health Educator?

A health educator need not

necessarily be a doctor or a health

professional. He is very often

another person, who lives in the

community, observes, listens and

wants to offer his time towards help

ing others become aware of the

reason for their exploitation. He does

not treat the community as a

laboratory to find out whether his

experiments are successful, but

together with the people, works to

find solutions.

Guidelines for a Health Educator

★ Admit openly to your students

that an education gap exists, and

that the shortcoming is yours as

much as theirs.

★ Understand in a personal way

the life, language, customs, and

needs of your students and their

communities.

★ Try not be the main teacher,

especially if your field of

specialization is narrow, and

limited to health care.

★ Always begin with the

knowledge and skills the

learners already have, and help

them build on these.

★ Make yourself as unnecessary as

possible, as soon as possible.

David Wernor, Helping Health Workers Learn

The health educator is humble

and maintains the lifestyle of the

community. He often has to unlearn

what he has professionally learnt

and is open to new concepts. He

often has to change the values

imbued in him through his own

previous lifestyle. The health com

municator views health problems in

the context of the existing social,

political and economic structures

within the community. He learns

how the community has traditional

ly solved its problems. He finds out

what the community believes to be

the causes of ill-health. He first

approaches everyone as a learner

and is willing to learn from each

person in the community.

The health educator does not

impose his ideas on the commu

nity, but through a series of

communication exercises, guides

and facilitates the community's

recognition of problems and the

finding of solutions.

What is Communication?

Communication is the process of

attempting to change the behavior

of others. Communication attempts

to alter the original relationship

which we have with the environ

ment. It attempts to reduce the

probability that we are solely the

target of external forces and

increases the probability that we

exert force on ourselves.

Communication is sharing: The com

municator’s job is chiefly helping

people learn to look at things in a

new way. Sharing real life ex

periences helps people see their

problems in perspectives other than

those they are used to. When you

share yourself with others, share

your feelings, your deepest

thoughts, you help others open up

and speak of things that really

matter to them.

When people exchange ideas and

information, they can work together

better. They strengthen one

another’s understanding and sup

port one another in action.

Sharing also entails parting with

information that gives power. Health

secrets are the most closely-guarded

secrets of the medical profession.

Sharing this knowledge helps over

come the imbalance in the power of

society over its health and promotes

self reliance.

Communication is trust: Sharing

oneself fully and honestly with

others is the first step in building

trust. Trust is the cornerstone of

communication. We believe in the

people whom we trust; we are will

ing to try out new ideas with them.

Trust comes when we live the

lifestyle of the people we are

1

★ Treat learners as equals—and as

friends.

★ Respect their ideas and build on

their experiences.

★ Invite cooperation; encourage

helping those who are behind.

★ Make it clear that we do not have

all the answers.

★ Welcome criticism, questioning,

initiative and trust.

★ Live and dress modestly; accept

only modest pay.

★ Defend the interests of those in

greatest need.

★ Live and work in the communi

ty. Learn together with people,

share their dreams.

David Werner, Helping Health

Learn.

Living Communication, Abner M. Eisenberg, Prentice Hall

communicating with, when we are

consistent in what we say and do.

Trust comes with humility. We need

to be honest about our potential and

our limitations. We have to accept

that our knowledge is not only

incomplete, but may be inappro

priate or wrong in the situation. We

should show our willingness to learn

from others.

Communication is listening: Listen

carefully and listen constantly. If

you have been open about yourself

and have facilitated sharing sessions

where everyone opens up, you will

be amazed at the perceptions of the

community. The community will

appear to be much more knowledge

able than you had probably

assumed. Always remember: com

munication is a two-way process.

Ask people about their problems.

Elicit their opinions and views.

Listen carefully to the answers.

These answers are the most impor

tant for helping you decide what you

want to communicate.

Listening helps build trust.

Listening helps you identify

priorities.

Communication Is honesty:

2

Be

Community health education is

successful to the extent that it

empowers ordinary people gain

greater control over their

health and their lives.

honest about what you can or will

do, and what you are prepared to

and capable of doing. This streng

thens trust. Be sure to keep your

promises.

Communication Is feedback: When

people share their information, feel

ings and problems with you, these

are important inputs in helping you

develop plans of action. Communi

cate progress back to those who

have helped you. Report back any

changes in plans that they have

helped you to make.

Communication is more than words:

It is more than films, slide shows.

puppets, mime, talking and reading.

Body language is also communica

tion. People are always responding

with non-verbal signals. Observe

them. Note them. They will give you

an indication of what your audience

is feeling.

Workers

What Does Communication

Entail?

Communication entails identify

ing a ‘message’ that needs to be

communicated. The message needs

to be put into a ‘code’—translated in

to symbols. These symbols can be

words, pictures, photographs,

stories, etc. The message is then

‘transmitted’—through books,

newspapers, posters, films, charts,

graphs, plays, songs, etc. The other

person to whom you are com

municating ‘receives’ the message

either visually, by hearing, or

through any of the other senses. He

then ‘decodes’ the message.

Any breakdown in any one of the

processes can cause a communica

tion breakdown.

Communication Breakdown in the

Process is Duo to

Vague idea or too general

Unclear symbols

Misunderstanding of the

symbols, indifference and

misperception

Unskilled transmission

Outer disturbances and

interference.

A. Jebamalaidass, Make a Model Before

Building.

Methods of Communicating

Communication methods include

interpersonal approaches (directed

towards individuals and groups).

visual aids and mass media. In

terpersonal communication - is

usually the best because it allows for

more interaction, more sharing, and

more learning for both the teacher

and the learner. Health education is

done best by these methods.

However, when mass awareness

needs to be created, other media

also come into play. A mixed media

approach possibly has belter results

than using any one single medium.

Campaigns particularly need a

multimedia approach, and also a

multi target approach. Choosing ap

propriate media depends on the ef

fects desired as also the cost.

When communicating, be sure of

what you want to communicate.

Does your message promote self

reliance, does it seek to transfer

knowledge, does it seek to

demystify? This is as important, in

fact more important than the

message itself, in the long run.

Individual educational efforts in

clude home visits, visits to work

place, and casual visits to the com

munity. In the following pages we

will try to provide an overview of the

other channels of communication.

Demonstration

Demonstration is a carefully

preplanned process. It starts as a

one-way communication but in the

hands of a good communicator, can

become a two-way process. It is best

suited to small groups, and to

teaching particular skills. It has

much more effect if the participants

themselves then practice what has

been demonstrated.

Group Discussions (group dynamics)

When a group of persons from dif

ferent backgrounds, class and caste

come together for the first time, they

may have difficulty in opening up

and sharing. Some of the people will

be talkers, and some listeners. The

talkers cap easily dominate the

discussion. They are also usually

from the more powerful section of

the community. Initially, they may

all listen, and expect you to do all

the talking.

A good leader looks for ways in

which she can get the more silent

and less powerful persons share

their ideas and feelings without fearing repercussions. The group leader

helps by supporting ideas, even if

she herself may not agree with some

of them. She facilitates by asking

questions, and helping the par

ticipants clarify their ideas.

Some helpful suggestions:

☆ Sit in a circle with everyone else.

This will help you feel an equal

and not superior to others.

☆ Dress in local style if possible.

★ Listen more than you speak.

Speak only to evoke responses

from the participants.

* Ensure that each one gets a

chance to speak. Do not let

anyone interrupt, especially

yourself.

■a- Be honest about your skills. Do

not presume to know all the

answers.

* Be open and friendly.

☆ Laugh with the group, not at

them.

* Try and remain in the

background. Encourage others to

take the lead.

☆ Recognize conflicts of interest.

Help participants find solutions

DOWN THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD or FROM FACT TO FALLACY

/

WHAT HAPPENED

THE EVENT

THE LABEL

(1st Inference)

2nd Inference

3rd Inference

4th Inference

ETC.

/

/

"1 see a

/

/

/

MR. "B" SAYS:

MR. "A" SAYS:

"It is a man

with a brief

case."

"He is taking

some work home

with him."

"He must be a very

dedicated man to

take work home

with him."

"A man that dedi

cated is bound to

be a success in life

and an asset to our

community."

ETC.

"1 see a

1

/mAN AND

1

/

I

S

(

BRIEFCASE

f

man and

briefcase/

\

COMMENT

l

\

1

\

"It is a man

with a brief

case "

yu

I

"Spies sometimes

use briefcases.

'

*

1

ff MAN AND^ \

//

BRIEFCASE S $ Jr\

I \< \

1

j

"1 wouldn't be

surprised if that

man doesn't turn out

to be a spy.

MAN AND

BRIEFCASE

"This country is

infested with spies

and unless we do

something about it

we're in trouble."

MAN AND

BRIEFCASE

No argument

i Inference because

\ it could be a

\ woman dressed

i like a man.

I Going off in

\ different

\ directions.

\

\

Where’s everybody going?

Brother!

ENDSVILLc

Communication—The Transfer of Meaning, Don Fabun, Glencose Press.

themselves. Group discussions

are best confined to groups of four

io ten people.

Storytelling

Storytelling is as old as com

munication itself. It is a natural part

of communication in communities

where learning still heavily leans on

‘audio’ methods. Stories project

situations and concepts without

confronting the listener directly with

his inadequate knowledge. They

allow listeners to identify with the

hero, who usually solves the pro

blems in the end. This is particular

ly true in cases where the practices

advocated in the story contrast with

or contradict existing beliefs and

practices. Il is precisely for this

reason that care should be taken in

selecting the story. The story cannot

afford to mock existing attitudes.

beliefsand practices, if the aim is to

give people confidence in their own

selves and their cu!lures.

Storytelling should be followed

with group discussions for further

expanding the concepts introduced.

Role play

Role play helps develop skills and

4

understanding through guided prac

tice. In this aspect it is similar to

drama. The members of the learn

ing group act out real life situations

and problems. But a drama has an

end planned in advance, which role

play does not have. In a role play.

the beginning is there. The end

develops through the play and is

often a surprise.

For example, a nutrition professor

once played the role of a poor

mother with eight children, and no

source of income except for a

depleted piece of land; a mother who

woke up at five in the morning after

a night of fitful sleep; a mother who

had to work as a labourer besides

having to cook, clean, fetch.water,

care for her husband, in-laws and

children. Towards the end, when

the money lender asked her to pay

the instalment on the loan she had

taken, she hit him on the head with

a handy paperweight. Fortunately.

the person playing the role of the

money lender was not seriously

hurt.

Role play helps one get into

another person’s skin, and feel the

problems from inside, as it were. It

helps the player explore ways of

overcoming the situation he would

meet in real life.

Role playing is especially useful

for developing practical skills in peo

ple who learn from life rather than

from books; it is helpful to the latter

also in putting into practice what he

has learnt in theory.

Such play helps develop leader

ship skills, and organizational skills.

It teaches players look for alter

natives in problem-solving, and

helps them critically analyze the

social, economic and political factors

that mould a person’s health.

Role playing is usually done in

small groups. There is no need for

any audience. The duration is usual

ly upto 20 minutes, if the action

maintains a high level of interest.

Role play works best when people

know and trust one another.

Games

Games arc fun, and at the same

time, can be used for imparting Im

portant messages. With adequate

Flipcharts

Flipcharts keep charts, pictures,

posters, diagrams neat and clean

and in proper order. The flip chart

keeps them bound. The pictures are

often connected by a story line.

Notes or explanations are written on

the back of the previous picture. A

flip chart needs a table, and is useful

for generating discussions in small

groups.

Flashcards

They are similar to flip charts. As

they are not bound, they are more

flexible. They can be rearranged to

tell different stories, or to present dif

ferent ideas. They create a dramatic

emotional impact through the flow

of pictures. Narration and handling

of flashcards are important for giv

ing appeal to the picture stories.

preparation and involvement of the

learners, they can become very rele

vant to the real conditions existing

in the community. However, if they

ar© not properly prepared, games

can pass on a lot of hidden

messages—especially games where

dice is used. Such games, though

ostensibly helping people get control

over their own health, can reinforce

ideas of‘fatalism’—the role that fate.

chance and luck play in life, and

thus shift responsibility from the

individual.

Games are best used in small

groups and are very effective with

children.

Songs

Song is a very attractive medium.

Songs and poems on health can be

effective if they have been developed

by the people. They help reinforce

messages and are a very good aid to

memory.

Puppets

Puppets again are fun. They are

also an accepted traditional form of

communication. They can interact

with the audience and elicit

responses immediately. They are

particularly effective with children.

Puppets need a dramatic story

with exaggerated action. Flat pup

pets do not need any props. Other

puppets may need simple props.

practise using puppets thoroughly

before you try it in front of an

audience.

Suggestions for effective use:

★ Keep the puppets facing the

audience.

★ Do not show yourself.

★ Make the good characters very

good and the bad horrible.

★ Avoid silent pauses.

★ Make your puppets speak to the

group. You are only the voice. Let

your voice be loud and clear.

Move the puppet when it speaks.

★ Change your voice when you in

troduce another puppet.

★ Make up the story as you go

along. Respond to the group’s

interests.

★ Let the puppet ask questions,

especially those you haven’t yet

asked.

★ Get the puppet to address

individuals directly.

★ The puppet directly answers

questions put by the group.

Flannelgraphs

These are flannel backed cut out

pictures placed in a series on a flan

nel board in the sequence of the

story. They help visualize concepts

and recreate situations involving

motion. They are again used in

groups like flashcards and

flipcharts.

Chalkboard

The chalkboard can be used in

conjunction with the other teaching

aids, to summarize essential points,

to draw diagrams, to clarify certain

points and to write our directions.

Remember: the chalkboard is not the

basis of the lesson; it only helps to clarify

it.

Newspaper

Wall newspapers are like bulletin .

boards which are regularly updated.

These newspapers are printed on

only one side, and are glued to the

wall. They contain considerable

amount of information. They are

useful for initiating discussion, infor

ming about new events, and as they

are stuck at the same place each

time, they can become an incentive

for adult literacy. Illustrations

enhance the newspaper’s appeal.

Posters

Posters are signs. They , inform

about coming events. They attract

attention. Posters can carry health

messages. They can motivate ac

tion. To be effective, posters should

5

A.

Communication Sender

B. Communication Receiver

DOES

COMMUNICATION

REALLY OCCUR

OR ONLY

ONE SIDED

‘LECTURING’

HAPPEN HERE ?

COMPARE

THE SECOND

SITUATION

WITH THE FIRST

Communication can be sucessful only if the SENDER of the MESSAGE also becomes the

RECEIVER of communication.

‘Teaching Village Health Workers—a Guide to the Process’, Ruth Harnar, Anne Cummins, VHA1

carry one message, with a simple

drawing. Colour strengthens the im

pact of the poster.

Posters can be used for initiating

discussions, creating awareness, or

as a health education aid.

Posters should be in local

language, and the illustration

should be applicable to local

conditions.

Books

As in all forms of communication,

the communicator must be clear

about his audience. A book or a

manual as an educational tool is

Judged by the response of the reader.

If he Is bored, he will simply shut it.

Written texts should be

★ warm and personal. Friendly

texts invite one to go ahead and

read more.

★ simple in structure without being

naive.

★ simplified by the use of diagrams.

★ Interspersed with appropriate

illustration.

The form of the book can be infor

mative. instructive or persuasive.

The choice depends on the target

audience, who writes the book, and

6

why. Printed word, like other forms

of communication, can either

‘domesticate' i.e. tie people more

closely to their realities; the hidden

messages in the book may be rein

forcing the reader’s role and status

within the existing system.

Liberating literature on the other

hand questions the system, conveys

knowledge on how to overcome it,

demystifies technical knowledge

and shares it with the layman.

Classic examples of liberating

literature is “Where There Is No

Doctor” and “Helping Health

Workers Learn”. Using all the three

forms where appropriate, the books

are person-centred. They acknow

ledge the reality of the people, and

help them gain skills to improve

their control over their health status.

While books can be occasionally

used for group discussions, they are

more useful as reference material

and aids to memory. They are also

helpful in teaching new skills.

especially if accompanied by

diagrams, flow charts and tables.

Illustrations

Illustrations are-very.good com

municators. They help in

understanding of the printed word

particularly.

Illustrations

★ bring visual interpretation to the

written word

★ bridge information gaps left over

in a written form

★ act as an exciter to further

imagination

★ bring an element of entertain

ment

★ simplify complicated concepts

★ present a realistic documentation

★ work as a creative element in a

good piece of printed material

★ work purely as a decorative

element

R. Kothari, The Role of Illustration in

Adult Education Material,

Illustrations can be and often are

misunderstood. While appropriate

drawings increase comprehension,

inappropriate ones block communi

cation.

While preparing visuals, work

with a talented person of the com

munity. She is often able to draw

HOW TO FIELD TEST

A- Decide who exactly is your audience.

☆ What do you want your audience to do with your message?

* Select a sample group from the audience. The group must have at

least 30 persons.

* Explain to the group what you are doing and why.

* Revise after testing.

REMEMBER: YOU ARE TESTING YOUR MATERIAL—NOT

THE AUDIENCE.

much better than you can. She also

visualizes things the way the com

munity generally would, and draws

them in a manner understandable to

everyone. Test all visuals before you

finally print them. If you are using

visuals in a book meant for a large

section of the population, test them

in all the places where they would

be used. For example, people in

North India sleep on a cot or bed,

while in the South, they sleep on the

floor. Women of Punjab wear salwar

kameez, women in Maharashtra

wear a sari tucked up between their

legs, and women in the South and

East wear a sari in their own styles.

Again, different foods are available

all over the country, and are served

in different ways.

Visuals should try and motivate

action.

Photos, Slides and Filmstrips

Photos are the basis of slides and

filmstrips. Slides can be used effec

tively to

* generate discussion and debate in

small groups;

yr motivate into action;

•A- question existing values;

* recognize signs and symptoms;

and

* teach practical skills.

Slides are usually accompanied by

narration—either pre-recorded or

adapted to the needs' of the au

dience. Slides can be interchanged,

or replaced by other more ap

propriate slides to change the thrust

of the presentation or to make it

more relevant to the area. If there is

on-going discussion, a particular

slide can be projected for as long as

is needed. Slides require narration.

This makes it a flexible tool for com

munication as the script can be

changed to suit the audience.

Filmstrips have similar advan

tages. However, as they have move

ment, and often a story, they gather

larger crowds. Filmstrips have the

added advantage that they can be

shown at the local cinema. But a

particular frame cannot be changed

if unsuitable, nor can it be shown for

a longer period if found necessary.

Both slides and filmstrips are ex

pensive. and need other accesories

like a slide projector, a film projec

tor, generators (if you are not sure

of the electricity status of the area).

technicians, etc.

Some helpful suggestions

* Try to shoot pictures in which ob

jects are familiar to the people;

yr Shoot at normal angles, and

using natural colour.

★ Shoot filmstrips in logical

sequence.

☆ Keep everything not really essen

tial out of the picture; extra

details merely tend to distract

from the main action or message;

Ar Take people’s permission if you

want Lo use their photographs.

Explain the use you wil be put

ting it to.

yr Pretest the photographs, slides

and filmstrips.

yr Introduce a film before you show

it, so that the audience knows

what to expect. It will give them

a purpose for viewing the film.

RECEIVER

Response:

"I don't

like it."

Division Manager

response:

"OK, I'll got

SENDER

the agency

to work

on it."

r

SH

RECEIVER

message:

Wants to

announce

a new

product.

message:

"Here's that

new product

ad."

Message:

"The boss

doesn't

like it."

Advertising Manager

response:

"We’ll start

SENDER

work

right away.'*

message:

Information

on new

product—

"Prepare an

p ad.”

message:

"Here's the

ad."

Message:

'The diem

doesn't

like It."

response:

"We’ve

turned

it over

to our

_

creative

department."

RECEIVER

Message:

"What’s the

matter with

you guys,

anyway?”

response:

"We’re

working

on it."

Advertising Agency |[

Account

Representative

SENDER

T

RECEIVER [

j Agency Creative

*

—

Supervisor

SENDER

message:

"Prepare

an od."

message:

"Prepare

an ad

about this

thing."

message:

"Here's the

ad.”

message:

"Here's the

ad."

RECEIVER

*^Copy writer/artist

SENDER

Communications—The Transfer of Meaning, Don Fabun, Glencose Press

★ The screening should be follow

ed by discussion. This will help

the group fix the important

messages in their mind, and will

clarify any points raised. If

necessary, show the film again.

Radio and Television

The choice of whether to listen or

not. to see or not. lies entirely with

the listener or the viewer, in both

these media. They are basically a

one-way communication. However,

if the programme has been devised

with the help of the listeners and the

health communicators in the field,

they can increase the credibility of

the health communicator.

In many countries, radio listening

groups have been formed, to in

crease the effectiveness of radio

broadcasts. These groups usually

listen to a programme together, and

then discuss it. Questions which the

health worker cannot answer are

referred back to the radio or TV sta

tion, and the answers relayed at the

next broadcast. Especially good pro

grammes can be taped for further

use.

Radio and TV programmes for in

itiating action cannot be very effec

tive without follow-up by the other

services. For example, a programme

t hat motivates mothers to immunize

their children is not of any use if the

local health centre does not have

any vaccines.

TV and radio to a certain extent

have become commercialized. The

TV particularly has proved very ef

fective in selling new lifestyles and

creating new consumer demands.

Using this medium to sell health and

development messages means the

further commercialization of the

fundamental right to health and life

with human dignity.

Both radio and TV in India are

controlled by the government. Many

of the programmes are produced by

the Centre, and are therefore total

ly irrelevant to the people in other

parts of the country. Again, though

there are many TV transmitters set

up, very few people can afford to buy

the TV sets they need to catch the

programmes. Again being govern

ment channels of communication,

these media have to transmit

messages that maintain the existing

structures of power. Messages sent

over the radio and TV today can on

ly be progressive and not liberating.

However, within these con

straints, programmes can be devis

ed with the local community, and

using traditional forms of com

munication, for beaming health

messages to a wider audience. The

basic purpose of such messages is

reinforcing the message of the

health worker in the field and in

creasing her credibility in the eyes

of the community.

TIPS FOR ILLUSTRATING

★ Use illustrations and words

together.

★ Use illustrations to motivate and

remind.

★ Discuss the illustrations with

audience.

★ Explain all symbols.

★ One illustration—one idea.

★ Use numbers to show the order of

viewing.

★ Make illustrations realistic.

★ Use realistic colours.

★ Use normal view for showing ob

jects. people and action.

★ Field test each illustration.

REFERENCES:

Handbook of National Conference of

Culture. All India Association for

Christian Higher Education. 1986.

2. Where There Is No Doctor. David

Werner. Hesperian Foundation

3. Helping Health Workers Learn. David

Werner. Hesperian Foundation

4. Health Education. N. Scotncy. Rural

Health Series 3, African Medical and

Research Foundation

5. Medical Service. Vol. 39. No. 8. Sept-Oct

1982. Catholic Hospital Association

of India.

6. A Manual oj Learning Exercises, Ruth

Harnar, Lynn Zelmer. Amy E.

Zelmer, VHAI

7. Make A Model Before Building, N

Jebamalaidass. Scarsolin

8. Basic Communication Skills for Develop

ment Workers. Draft. 1976. for the

Communication Strategy' Project.

Ministry of Information and Broad

casting, Colombo. Sri Lanka

9 ■ Community Health Education in Develop

ing Countries, Action Peace Corps. In

formation Collection & Exchange Pro

gram & 1 raining Journal Manual No.

8, 1978

1.

WHERE DOES THE PROBLEM LIE?

An Analysis of Communication to Aid Solving Breakdown Problems

Characteristics

Ingredients

Sources

Ability

Knowledge

Attitudes

Culture

Social System

—to reason out

— to plan

—to decide

— to select

—of the subject

—ot the audience

—of the medium

—of the communication

techniques

—of the communication

approaches

—of the society

—of the communication

theory and process

—of the communication

situations

—•towards oneself

—-towards the audience

—■towards the medium

—-towards the purpose

—perception

—Interpretations

—usages

—barriers

—concepts

—acceptance

—involvement

—contribution

—similarity of

culture to

receiver

—position

—role he plays

—to adapt

— to act

—to listen

Messages

Channels

Weight

Content

Motivation

Adaptation

Influence

— to bring out the

correct perception

—enriching

—affect the belief

—local customs

—stimulating

—provoke thinking

—vocabularies

— to capture the

attention

—simple and

understandabl e

—change the customs

— to clarify the

interpretation

— to effect timely

response

—too general or

vague

—suited to audience

—create problems

—expressive

gestures

and habits

—differing

meanings

—through

frequency

—through

isolation

—through

reward

Capacity

Variety

Effects

Availability

Techniques

—to transmit

—five senses and the

nervous system

—easy access to

reach many

—traditional

media

—structure

and condlon

of the

channel

—relevancy of

the C

—balanced

use of the

channels

—at the

appropriate

time

—correct selection of the1—clarity of the channel

channel

— reduction of the effort

—group media

—to capture attention

—right use

—adaptable to

environment

—to convey the

correct meaning

—multi channels use

—known to the

audience

—to amplify

Receivers

--towards the receiver’s

groups

—to multiply messages

—to be available

— light wave channel

—sound wave channel

—electronic systems.

Ability

Knowledge

Attitudes

—economically

viable

Culture

—of the subject

—towards oneself

— to recognise the

—of the source

—towards the source

stimuli

— to perceive the purpose —of the medium

—of the society, environ —towards the medium

of stimuli

ment and culture

—towards the stimuli

—to interpret

—of the communication —towards his group

—to respond

—situation

—and least

effort

Social System

—cultural barriers —concept

—customs and

—acceptance

traditions

—understanding — involvement

— interpretation

—contribution

Make a model Before Building, A. Jebamalaidass

9

THE RADIO IN SUPPORT OF MOTHER

AND CHILD HEALTH

P.V. KRiSHNAMURTHY.

*

PETER CHEN.

**

Radio broadcasting has been in In

dia since 1927. The Government of

India named it ‘All India Radio'

when it nationalised the radio ser

vice in 1930. Today. AIR broadcasts

from 86 stations, covering about

89.65 per cent of a population of

about 750 million people.

AIR’s programmes include pro

grammes for development such as

agricultural extension, women

welfare, school broadcasts, youth

an«J current affairs, entertainment

programmes, commercial programmes and external services

programmes.

In order to improve the special

programmes for women and

children, the Ministry of Information

and Broadcasting of the Govern

ment of India, in collaboration with

UNICEF, has been organising

special

media

orientation

workshops on Mother and Child

Health for radio producers since

1982. These workshops focus on the

first year of a child’s life, from con

ception to 12 months of age and the

health interventions required for the

survival of the mother and child.

These workshops have been unique

in that they are all area and regionalspecific, involving decision makers

of various state governments from

the highest office down to the lowest

rung of field workers—the Anganwadl workers and Auxiliary Nurses

and Midwives.

Programme Formulation

Methodology

The radio series in support of Mother

and Child health is evolved during

a ‘Media Orientation Workshop’ for

the producers of relevant program

mes. This is a six-day workshop

where participants drawn from the

10

Social Welfare Department, Health

and Family Welfare Department, as

well as the Rural and Tribal Welfare

Department of the concerned states.

interact with media personnel from

the All India Radio. Doordarshan,

Field Publicity Department and the

Song and Drama Division of the

Ministry of Information and Broad

casting of the Central Government.

The number of participants and

resource persons are usually around

75 to 80, to optimise the organisa

tion of the workshop. The purpose

of the workshop is to

★ motivate producers to develop an

empathy for field-level workers

and to realise their role as a sup

port to them.

★ make the field level workers

realise the importance of media

as a support to their programmes

and its legitimising and confir

matory potential.

★ involve decision makers and sub

ject matter specialists in pro

viding the needed services and in

put to the programme.

★ develop the technique of a team

mode approach to programme

conceptualising, planning and

production.

The participants selected for the

workshop are such that all levels of

functionaries connected with the

implementation of the social welfare

programme and delivery of health

services are represented.

The programme producers from

AIR and Doordarshan are those

who are responsible for the produc

tion of women welfare programmes,

children’s programmes, Farm Radio

Officers and Extension Officers,

Field Publicity Officers from the

Mass Education and Information

Department of the State Govern

ment are also invited to participate.

Participants from the Social Welfare

Department range from the Deputy

Secretary-ICDS, Deputy SecretaryDD, to Anganwadi workers. Super

visors, DDPOS and the District

Social Welfare Officers. Participants

from the Health Department include

the Director of Health Services, the

Director of Family Welfare. District

Medical Services. Lady Health

Visitors. ANMS and traditional mid

wives (Dai).

Audience Profile

At the first plenary session of the

workshop, an audience profile of the

people of the area within the listen

ing range of the radio station is

presented to the participants. This

audience profile study is normally

undertaken by a social scientist/researcher of a University or Col

lege of Home Science or Agriculture

located in the same area. This has

the added advantage that the resear

cher is a local person and he/she

understands the language and

culture of the local population.

Besides the usual demographic

and psychographic profile, the study

highlights the knowledge, attitudes

and practices of mother and child

health (and by its extension, care of

the pregnant and lactating women

and new born infants) of the rural

population. The study also takes a

look at the medical services and

facilities available, as well as the

local belief, taboos and superstitions

associated with child-bearing and

child-rearing. This ‘audience profile’

is to give the participants an idea

about the people that they will in

teract with during the field visits.

Though all the participants are from

the same state with most of them

from the same region, it is con

sidered important to recap for them

what most of them may already

know of the KAP towards mother

and child health, through a scientific

study.

Self-Introduction for Breaking

the Ice

As the participants are drawn from

a cross-section of activities in the

social development area, each per

son is asked to introduce

himself/herself and say a few words

about his/her experience in the field

till date. This is a very effective way of

‘breaking the ice’ between the ‘class’

and ‘status’ barriers normally en

countered when people working at

different levels are brought together.

The participants are told that the

status of superiors and subordinates

will not be in force for the next five

days but that they are to sit on a

common platform to evolve the

series of radio programme schedule.

Field Visits

The participants are divided into

small groups, normally around eight

to a group, with each group a

heterogeneous whole as far as possi

ble. Each group will have at least

one media person, one social

worker, one health worker and one

resource/decision making person.

The resource persons are drawn

from specialists on various fields

such as communication, nutrition,

pediatrics, gynaecology, preventive

and social medicine and ad

ministrators of the social welfare

programmes. Throughout the

workshop, there are no lectures or

presentation of papers (except for

the audience profile initially). The

resource persons act as guides to the

participants to clarify any doubts

they may have in the field of their

specialization beside participating

as full-time participants.

On the second and third days of

the workshop, each group is sent out

to visit different villages within the

listening radius of the radio

transmitter. As the radio transmit

ter is usually located at the outskirts

of a city, some groups travel as far

as 80 to 100 km away for their field

visits, while others are distributed

between urban slum areas and near

by villages.

The purpose of the field visits is for

the participants to get to know the

routine working of a day in the

village, unbiased by previous infor

mation of their arrival so that the

villagers do not get the feeling that

an ‘inspection’ team is visiting them

and that they are to ‘prepare’ for the

visitors.

On arrival at the villages, the

groups normally split up into

smaller groups of two or three per

sons so that they can interact with

the villagers easily and conduct a

door to door survey. The survey is

not a regular structured one but em

phasis is placed on observation and

unstructured questions. No doubt

this method makes it a little difficult

to analyse data thus collected but it

is invaluable for creating rapport

with the villagers who usually see

visitors as strangers or government

people who normally come to ask a

lot of questions, make a lot of pro

mises and leave without ever going

back to implement their promises.

The information sought in this

survey is focused on the period of

conception, to delivery, till the child

attains his/her first birthday, the

type of health care/interventions

that rural women take to ensure the

safe delivery and survival of their

children and themselves, the

facilities available and whether they

use them or not, the availability of

radio sets in the villages, and the

types of programmes they listen to

and whether they will listen to

special programmes on mother and

child care if they are produced for

broadcast on a regular basis.

It is interesting to note that in all

the 16 workshops organised since

1982, though most of the topics

evolved for the radio series were

about the same (as the process of

pregnancy and childbirth always re

main the same), each region where

these workshops were held, laid dif

ferent emphasis on different aspects

of pre-natal,/- post-natal and child

care. Thusr; Haryana in the northern

part of India stressed on the early

age of marriage and early concep

tion as a problem to be addressed,

while participants of the workshop

held in the Koraput district of Orissa

saw the problem to be prolonged

breast feeding of the child among

the tribals of Orissa.

An important component of the

field visit is the pre-testing (actual

ly, post-testing) of radio program

mes that are already broadcast. The

purpose of the pre-test is to elicit in

formation from the rural audience as

to whether the programme is one

they normally listen to, and if not

why not, the language used in the

broadcast—whether it is too

academic or technical, and the

format—whether it is pleasing and

acceptable. The rural audience is

also asked to recommend the format

for producing the series of program

mes on mother and child health. In

all the 16 workshops, the radio pro

ducers and other media personnel

found it very useful to have this ac

tual field level interaction with the

villagers. As one of the radio pro

ducers said, they do not have the

time to sit and ‘chat’ with the rural

people when they go out to record a

programme in the field as there is

always the question of time con

straint or availability of transport.

So they record quickly what they

think to be acceptable by the rural

audience and produce a programme

for broadcast. This field interaction

also enables the participants from

other departments to see the need of

linking up service facilities and

departmental interaction.

11

Group Work

During the remaining two days of

the workshop, each group compiles

and analyses the data collected from

the field visits. Based on the infor

mation gathered, they draw up a list

of recommended radio programme

information gathered, they draw up

a list of recommended radio pro

gramme schedules to be produced

and broadcast later. It is during this

group work that the resource per

sons’ expertise comes in handy to

help formulate the schedule. The

schedule lists the problems iden

tified, the messages to be imparted

to address the problems and suggest

programme titles. Normally, an

average of 26 radio programmes are

identified for broadcasting. As each

group comes up with a different

schedule, a technical committee

screens all the schedules and com

piles a ‘master’ schedule which is

presented to a representative of the

Information and Broadcasting

Ministry at the valedictory function

on the sixth day. This schedule

gives the programme producer a list

of topics to produce for the next six

months if these special programmes

are to be broadcast once a week.

An average schedule of radio pro

gramme topics reads like this: (Final

schedule of the Cuttack workshop)

★ Age of Marriage

★ Signs of Pregnancy

★ Diet during Pregnancy

★ Ante-natal Check-up

★ Common Diseases during

Pregnancy and their Prevention

☆ Anaemia

*

☆ Toxaemia of Pregnancy

*

☆ Ante-partum haemorrhage

*

★ Preparation for Delivery

★ Post-natal Care

★ Diet During Lactation

★ Breast Feeding is Best Feeding

★ Colostrum is Necessary for the

*

Child

★ Care of the Newborn

★ When to Immunize the Child and

Why

★ Polio, a crippling Disease

★ Diphtheria, a Dangerous Disease

★ Whooping Cough is Dangerous

★ Tetanus, a Killer Disease

★ Measles—be Careful of Compli

cations.

12

★ Save Your Child from Tuber

culosis

★ Diarrhoea is Dangerous—do not

Neglect it

★ Infants’ Diet

★ Growth and Development of the

Child

★ Weigh Regularly and Know the

Progress of Your Child

★ Common Childhood Diseases

★ Common Accidents during

Infancy

★ At your Service—

☆ Health Institutions

☆ Health Workers

☆ Anganwadi Workers

★ Sanitation for Health

★ Responsibility of the Family for

the Health of the Mother and Child

★ Safe Drinking Water

*

★ Nutrition from the Kitchen

Garden

★ Spacing for the Health of the

Mother and Child.

(The participants at the Cuttack workshopfelt

that those programmes marked with an

*

asterisk

should be treated separately, hence

they came up with a total of 31 programmes

for the schedule.)

Follow-up

The Media Orientation workshop is

only the beginning of the project to

harness the vast potential of the

radio for development communica

tion, focusing on mother and child

health in the rural areas. The next

logical step is io see that radios are

made available to the rural women.

Though statistics show that there is

a high proportion of radio ownership

in India, few of them are actually in

the hands of those who need to use

it most, the rural women. Due to a

variety of reasons stemming from

traditional subservience to the male,

to families not being able to afford

the cost of a radio set, rural women

rarely get the chance to listen to pro

grammes primarily aimed at them.

Collecting groups of women

together to listen to a radio pro

gramme is one thing and getting

them to learn from them is another.

In order to facilitate the absorption

of the child survival and develop

ment (CSD) messages by the rural

women, the Anganwadi worker is

given basic training on how to

generate group discussions. A pre

pointed and pre-paid letter paper is

also given to her along with a guide

book in the form of a flipchart for use

during the group discussions. The

guide book (flipchart) has a picture

of the programme topic on one side

while the other side has a small

synopsis of the radio programme

with a few printed leading—in ques

tions. The questions help the

Anganwadi worker start the discus

sion regarding the programme

broadcast. At the end of the session,

the Anganwadi worker fills in the

pre-paid inland envelope and mails

it to the radio station. If there are

questions raised by the audience she

cannot answer, the reply will be

broadcast during the first five

minutes of the next scheduled

broadcast.

Analysis of Experience

From July 1982 till 31 July 1986, a

total of 16 Media Orientation

workshops were held in 12 states

with participation from 57 AIR sta

tions. Eleven of these stations went

on the air for organised group listen

ing while the others are either in the

various stages of the project or have

already used the information

gathered from the workshop for

their normal programme produc

tion. Some of these stations, after

the completion of the series, have

gone on to repeat the series with

minor modifications based on the

evaluation of the programme under

taken by a third party. It is in

teresting to note that ongoing

monitoring and evaluation of these

programmes showed that there is a

very significant number of

disorganised listeners turning into

the programmes and writing to the

radio stations on their own to seek

more information or clarfication

regarding

the

programme

broadcast.

Observations and results of three

monitoring and evaluation studies

carried out in the states of Haryana,

Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh In In

dia provided a number of organised

listeners’ groups in these three

states were 1470. 1000 and 250,

respectively. It is not known how

many self-owned radio sets are in

these states as the government of In-

dla has discontinued the need for

maintaining license fees for low cost

radio receivers, on which basis an

enumeration could have been made.

For the purpose of the study, a

total of 2041 listeners from organis

ed groups were interviewed while

only 249 independent listeners were

interviewed. Simultaneously, 290

group animators were Included in

the survey with 248 non-listeners

thrown in to complete the picture.

The combined studies showed

that more than 90% of the clientele

consisted of women from the weaker

sections of the community with the

majority of the respondents within

the age group of 20-39 years of age

(approx. 80%). Over 50% of these

women were illiterate while about

35% of these were still nursing their

children. Most of these rural women

also live in Joint or extended families

with or without a radio set in the

house. Though about 60% of them

claimed to have a radio set at home

they rarely listened to radio pro

grammes. This may be because they

could not get access to the radio set

as the husbands carried it off to the

field or their place of work. Motiva

tion for listening to the special pro

grammes promoting child survival

and development were usually pro

vided by the Anganwadi worker as

this took the form of extension

education through the radio. A

welcome feature was that over 45%

of the respondents were elderly

women with grown-up children.

These were the mothers and

mothers-in-law who normally take

the responsibility of bringing up the

children in the village.

The number of women in each

listening group varied, ranging from

10 to 35 with an average centred

around 23 per group. About 60% of

the groups surveyed entered into

discussion of the radio programmes

topic immediately with initiation

from the animators. This gave the

listeners a lot of satisfaction as well

as new knowledge, as their im

mediate doubts were clarified.

Significantly, about 97.19% of the

Anganwadi animators surveyed

reported gain in new knowledge

related to child survival and

development issues while over 74%

women learnt something new.

Topics from which new knowledge

was gained were: common vaccine

preventable diseases (74.83%),

Vitamin A deficiency (69.85%).

anaemia (60.86%), common eye

infections (69.85%), cleanliness of

environment (58.60%), diarrhoea

management (40%), and family

planning/spacing (19.46%). Those

who participated ingroup listening

gained more knowledge through

discussions of the topics after the

broadcast although individual

listeners also made significant

knowledge gains.

The evaluation studies also show

ed that retention of new knowledge

gained varied from topic to topic,

with the highest on accidents

(95.18%), common eye infections

(89.70%), cleanliness and environ

ment (82.5%), diarrhoea manage

ment (50%). family planning/spacing

(43.90%), etc. The reasons given for

the low retention of some of the

messages were that these were too

complex and difficult to follow and

so were forgotten easily. Those

messages that had prior exposure

had higher retention value.

Attitudinal and behavioural

changes were also noticed among

the respondents who listened to the

programmes. Nearly half of the

respondents in Tamil Nadu showed

their willingness to add more

greens, milk and vegetables to their

diets after listening to the broad

casts. A large number of listeners

consulted medical practitioners on

the subjects of immunization,

nutritious food for their children,'

care of children, care of pregnant

women as well as on family spacing.

As a result of these radio program

mes, a large number of rural women

came to know of the services

available to them. They also ac

cepted the advice young Angan

wadi workers gave them on nutri

tion and mother and child care even

though a number of the workers are

unmarried. This was the legitimis

ing effect as previously, the Angan

wadi workers were treated as inex

perienced girls, who were still un

married and “naturally will not

know about childbirth and child

rearing’’ by the older women of the

community.

Tailpiece

As a spin off, All India Radio has

now also included sessions on using

the radio for promoting mother and

child health in the courses con

ducted at their Staff Training In

stitutes at New Delhi and

Hyderabad, for senior programme

producers and station directors who

go in for refresher courses.

Doordarshan has also requested

UNICEF to organise special media

orientation workshops for their TV

programme producers working in

the’INSAT’ stations beginning with

Nagpur, Maharashtra. The ‘INSAT’

stations are those TV stations which

have the responsibility of producing

programmes for telecasting to the

rural area via the Indian Satellite,

INSAT-IB. Presently, there are six

such production centres located in

Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat,

Maharashtra, Orissa and Uttar

Pradesh.

* P. K Krishnamurthy is Media Consultant,

UNICEF ROSCA, New Delhi.

** Peter Chen is Assistant Programme Com

munication Officer, UNICEF, New Delhi.

‘ ‘There is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what

is happening. ”

13

The New Drug Policy

The new drug policy has been

finally announced, after four years

of intense discussions.

It is well recognized that health

care ideally covers preventive, pro

motive and rehabilitative aspects.

besides the curative. However, in

the absence of such an ideal situa

tion, curative care becomes very

important, and a rational national

drug policy becomes imperative.

Keeping this in mind, numerous

national and international organiza

tions like VHAI, MFC, FMRAI, KSSP,

D AF WB, AIDAN (All India Drug Ac

tion Network), CHAI and WHO

organized conferences, seminars

and workshops. The policy makers

also had recourse to the recommen

dations of the Hathi Committee and

the WHO model list of essential

drugs. The example of Bangladesh’s

drug policy and its positive impact

on the health care system was also

there.

What is the essence of the new

drug policy and why should health

personnel be seriously concerned

about it?

★ Decision making and formula

tion of the drug policy has been done

by the Chemical Ministry, with very

marginal inputs from the Health

Ministry. Not merely has there been

no Informed public debate, with free

availability of the relevant

documents and statistics, but worse

still, even the Parliament has been

bypassed.

* Hike up of drug prices has been

assured to the drug industry.

Estimates of price rise are

anywhere between 20 to 300 per

cent. A rise in the price of essential

drugs will force the government to

spend a larger part of the already

meagre health budget on buying the

same amount of drugs.

The decision to increase the mark

up to 75 and 100 per cent on the two

new categories has already been

taken, while the drugs to be includ

ed in these categories have not yet

been finalized. While an attempt to

keep these lists of Category 1 and 2

drugs as small as possible has been

14

AS IF PEOPLE DON'T MATTER ANYMORE

made, it has been decided to decon

trol all other drugs, leaving the

manufacturers free to fix and adjust

their own prices.

The government proposes to set

up a National Drugs and Phar

maceutical Authority (NDPA)/

which is to be the apex body of

decision-making on drug issues.

However, this authority will be set

up only after three months. Though

such a statutory body was recom

mended even by the Hathi Commi

ttee, the present proposed body is

merely advisory in nature. While its

composition is not specified, special

mention has been made of the

representation of the industry

among its members. There is no

mention at all of health groups, con

sumer groups and other concerned

sections of society. Again, as an ad

visory body, its recommendations

cannot be enforced; those which suit

the industry are bound to be heed

ed, and those which put people

before profits will be put in hiberna

tion, as has been the practice all

along.

★ There is no assurance of

availability of essential drugs. Drawing

up of the nation’s Essential Drugs

List is the first exercise to be under

taken when framing a drug policy.

We have enough recommendations

to go by—WHO’s essential drug list,

the recommendations of the Interna

tional Consultation on Rational

Selection of Drugs, organized by

VHAI, the drug list of Bangladesh,

whose health problems are so

similar to ours. Yet the main thrust

of the new policy appears to be

reducing such a list to the barest

minimum. While the model lists

contain around 250 drugs, under

the new policy Categories 1 and 2

will total about 100 drugs, and

Category 3 has been done away with

altogether.

The government has delicensed

96 drugs in the hope that more

essential drugs will be produced.

Past experience has, however,

shown a decrease that a certain

percentage of essential and life

saving drugs be produced, as had

been demanded by health and con

sumer groups. In view of the

existing shortages of essential and

life-saving drugs, it was critical that

a stipulation be made, making it

mandatory to produce 50 to 75% [

essential drugs.

The increase in MAPE (Maximum

Allowable Post Manufacturing

Expenses)

the

government

presumes, will make the production

of essential drugs more attractive to

the industry. This again has been

disproved by past experience, and at

tremendous cost to the consumer.

★ There has been no attempt at

banning of useless, irrational or hazar

dous drugs. India has the- largest

number of formulations in the whole

world. And a majority of them are

combinations, whose ingredients

and dosages are in total violation of

therapeutic norms. The Hathi

Committee and the WHO have

recommended the need to withdraw

such drugs. In view of the increas

ingly available medical reports and

results of studies which indicate the

cost ineffectiveness or harmfulness

available, such drugs should be

removed from the market.

Yet the policy makers have not

taken the trouble to screen the for

mulations available, blacklist harm

ful ones, and make the information

available to the medical profession

and to the people at large.

(

Instead, the only mention made is

that the NDPA will, as one <Of itS I I

naftpr

*

many activities, look into the matter

of formulations and make recommen

dations for banning. Besides the

irony of the NDPA and the drug in

dustry deciding on the rationality of

drugs, this means precisely nothing

when we remember that the NDPA

is only an advisory body.

No mention has been made in the

policy about detailed package

inserts or any form of unbiased in

formation to the medical profession

and to the user.

From the health point of view, it

is extremely irresponsibile on the

part of the policy makers not to have

ensured rationalization of drugs in

the market before taking the deci

sion to raise the markups. Such

drugs, even if their prices fall, are an

economic waste; but when their

prices increase, it is nothing short of

criminal.

★ Production ratios have been chang

ed in order to increase the produc

tion of essential drugs, or so claims

the policy document. The new ratios

are as follows:

Bulk Formulation

FERA Companies

ExFERA and Indian

Cos.with turnover

over Rs. 25 crores

Turnover between

Rs. 10 & 25 crores

Turnover less than

Rs. 10 crores

1

4

1

5

1

7

1

10

The question of enforcing the

production ratios does not appear to

have been looked into, and from

past experience we know that such

ratios were never abided by. Earlier,

50 percent of the bulk production by

the FERA companies was to be

made available to unrelated pro

ducers for formulations. The new

drug policy says nothing about this.

Delicensing of bulk drug produc

tion has taken place even in areas

where production capabilities have

been established by wholly Indian

companies. In the case of those

delicensed drugs which fall outside

Categories 1 and 2, the production

of non-essential, irrational and

hazardous drugs would escalate,

because of their increased

profitability.

One of the major criticisms of this

aspect of the policy by the industry

itself is that though 40 per cent

diluted, ex FERA companies are yet

essentially non-Indian, especially as

the difference between the capital

i nvested by them and foreign remit

tances made by them is so drastic.

These companies are being treated

on par with wholly Indian

companies.

With increased profitability, no

control on the foreign remittances,

transfer pricing, etc., it will not be in

the interest of national economy and

the growth of indigenous industry to

treat ex FERA companies like

Indians.

★ The new drug policy has ex

tended broad banding to 31 groups of

bulk drugs and formulations. This

means that companies can produce

drugs and formulations having

similar processes without needing

special licences. That is. companies

can make changes in multiingre

dientformulations, even if the major

ingredient does not come under

broad banding. Broad banding can

only work if irrational and hazar

dous drugs are removed from the

market, and restrictions are placed

on combination drugs.

* Quality control is of prime con

cern to the policy makers. Any

attempt at controlling the quality of

over 40,000 formulations of different

combinations and permutations has

to begin with restricting the number

of formulations allowed, and by en

suring that a majority of them are

single ingredient drugs. Only then

can good manufacturing practices

and good quality control be ensured.

Allowing responsible institutions

like labs of academic and govern

ment institutions conduct quality

control checks is theoretically a

good idea in the absence of any

other infrastructure. Yet the ram

pant corruption, the purchasing

power of the industry’ and the

previous track record of several

companies will place the onus of

quality control on the consumer,

who will be forced to evolve indepen

dent counter checking strategies if

he desires a safe, cheap and yet ef

fective drug. This responsibility

must ultimately lie with the govern

ment and the manufacturer.

India with a well evolved phar

maceutical industry, a large medical

system and a democratic form of

government could well have affored

a people oriented rational drug

policy. Yet the present policy is

nothing but a new year’s gift to the

industry—people have taken the

back seat.

The whole issue of brand name vs.

generic names has been given a

silent burial. This, infact was one of

the major demands of consumer and

health groups—a demand backed by

the experience of other third world

countries, a demand that would

have cut down confusion for the

medical profession and cost for the

consumer.

The policy makers appear not to

be content with mere handling

backwards to appease the industry’

but have converted industry

demands into policy statements.

Liberalization of policies to help

industries is understandable when

it comes to consumer goods, but un

pardonable when it comes to life

saving drugs in a country’ where the

majority of the people are too poor

to afford even on square meal a day.

These drugs are literally the dif

ference between life and death for

them, if they are cheap. If they have

to further scrimp and save for just

a few tablets or injections, and this

through government action, the

government is going back on its

responsibilities. The commercializa

tion of health, in India is complete.

The most shocking aspect of the