WOMEN'S HEALTH ARTICLES

Item

- Title

- WOMEN'S HEALTH ARTICLES

- extracted text

-

RF_WH_.11_8_SUDHA

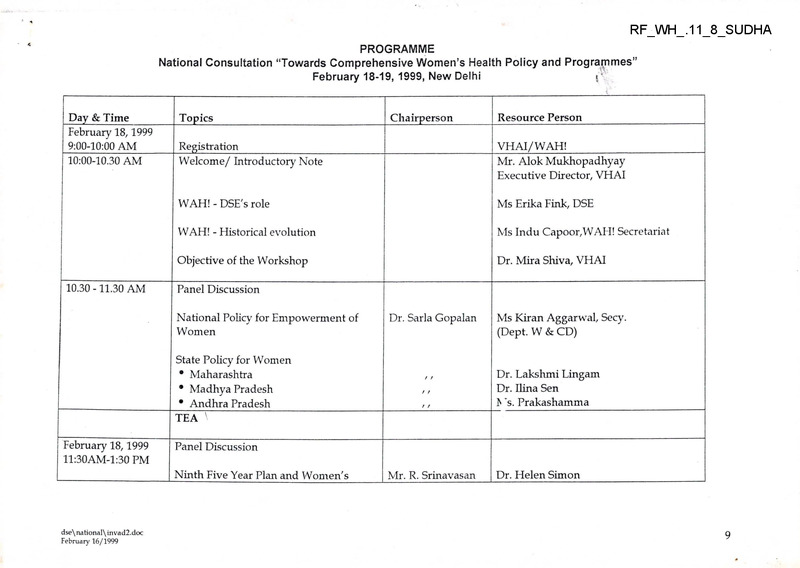

PROGRAMME

National Consultation “Towards Comprehensive Women’s Health Policy and Programmes”

February 18-19, 1999, New Delhi

i‘

Day & Time___

February 18,1999

9:00-10:00 AM

10:00-10.30 AM

10.30 -11.30 AM

Topics

Chairperson

Regis ti’ation_______________

Welcome/ Introductory Note

VHAI/WAH!__________

Mr. Alok Mukhopadhyay

Executive Director, VHAI

WAH! - DSE's role

Ms Erika Fink, DSE

WAH! - Historical evolution

Ms Indu Capoor,WAH! Secretariat

Objective of the Workshop

Dr. Mira Shiva, VHAI

Panel Discussion

National Policy for Empowerment of

Women

Dr. Sarla Gopalan

State Policy for Women

• Maharashtra

• Madhya Pradesh

• Andhra Pradesh

TEA \

February 18,1999

ll:30AM-l:30 PM

Ms Kiran Aggarwal, Secy.

(Dept. W & CD)

Dr. Lakshmi Lingam

Dr. Ilina Sen

F Ts. Prakashamma

Panel Discussion

Ninth Five Year Plan and Women's

dse\ na Honal\ invad2.doc

February 16/1999

Resource Person

Mr. R. Srinavasan

Dr. Helen Simon

9

Health

National Health Policies and

Programmes from women's perspective

Mr. R. Srinivasan

Women's Health Policy

Mr. R. Srinavasan

Dr. Imrana Qadeer

-■

Dr. Sundari Ravindran

Hoar.

2.15 - 3.30 PM

Panel Discussion

Economic Policy & Women's Health

Prof Ranjit Roy

Chowdhury

Drug Policy & Women's Health

Education Policy & Women's Health

3.30 - 5.30 PM

Ms. Kumud Sharma

Dr.Mira Shiva

Prof.. Usha Nayyar

Dr.Vimla Ramachandran

Dr.Y.N. Chaturvedi

Dr.Nirmala Murtv

Dr.Abhijit Dasgupta

Dr.Shanti Ghosh

Dicussion______

TEA___________

Panel Discussion

Reproductive & Child Health Policy &

Programme

Nutrition Policy & Women's Health

Traditional System of Medicine (TSM)

Policy & Women's Health

//

Dr. H. Sudershan

Dr.Veena Shatrughan

Dr.Shanta Shastri

Dr.G.G. Gangadharan

Ms. Philomena Vincent

Discussion

dse\national\invad2.doc

February 16/1999

10

Day & Time

February 19z 1999

9.00-9.30 AM

Topic

____

Mainstreaming Gender in Development

9.30 -11.45 AM

Panel Discussion

Chairperson

Ms. Binoo Sen

Policy

Resource Person

Dr.Sujata Rao

Ms.Sarojini Thakur

'XrG?c)

Ms Mohini Giri

Dr. Padma Seth

Laws Affecting Women's Health (WH)

Ms. Amita Dhanda/Dr.Bharghavi

Mental Health Concerns in WH

Ms Jasjit Purewal/

Ms.Hiti Mahendru

Violence & Women s Health

Dr. Padmini Swaminathan

Occupational Health Hazards of Women

TEA

11:45-1.:15 PM

Panel Discussion

Women & Panchayati Raj Institutions

Ms. Nirmala Buch

h s. Aleyamma Vijayan

District Level Planning for WH

Women and Media

1.15-2.15 PM

Dr. Susheela Kaushik

Dr. Rami Chabra

Ms. Akhila Shivdasa

LUNCH BREAK

11

■ ’-P.dnf-

c

2.15 - 3.45 PM

Training for Women's Health

Dr. Helen Simon

Gender & Power Issues in Medical

Education

Women's Perspective & Gender

Sensitization in Health Care

Ms.Pallavi Patel

Dr. Mira Sadgopal

•r.Thelma Narayan

Ms. Sarojini

Thakore

Ms.Shumita Gosh

Ms.Saulina Arnold

Dr.Srilekha Ray

Dr. Sarla Gopalan

Ms.Renu Khanna

Discussion

3.45 - 4.00 PM

TEA

4.00 - 5.30 PM

Issues for Advocacy

Work

5.30 PM

Conclusion

dse\national\invad2.doc

February 16/1999

Strategy - Group

Dr. Mira Shiva

12

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—33

instructions for filling rIN MONTHLY REPORT FORM

FOR HEALTH WORKERSj (MALE AND FEMALE)

You will complete this form at the end of each month and hand over a copy to your supervisor in the first week of (he next month.

.......... Yo11 wil1 nmintnin one copy in your own file at the sub

centre.

The monthly report form will mdicate the extent of work carried out by you during the month

“'k"‘ (M,">

mltted""',h’ ”” °ry°",

I.

‘l»

reported P, tJe He.S wX

the Repo,, „ het.g !ub.

■nd P',C “d tto m“'h f"

Immunizations

1.

±”y

‘"“’-S

—* ■«<

2.

p™, :»r " «■ “"S

3.

D.P.T. : Enter number of persons given first dose of DPT vaccine during the

given second and third doses of D^acciite^ £

vaccine during the month and

dose of DPT during the month.

Umber glven booster

4.

Poliomyelitis : Enter number of persons given first dose of poliomyelitis vaccine

month, number given second and third doses of vaccine during th<

booster dose during the month.

5.

er

Tetanus Toxoid : Enter number of pregnant women ; '

given first dose of T.T. during the month,

and number given second dose of T.T. during the month.

Enter number of persons other than pregnant women given T.T. during the month.

nun’ber of persons given other immunizations and specify which,

6-

H.

Communicable Diseases

I.

Malaria :

1.1 Enter number of fever cases seen during the month.

1.2 Enter number of blood films taken from fever cases during the month.

1.3 Enter number of cases showing blood films positive for malaria parasites.

NOTE : These may include positive films taken during the previous month from fever

cases, but of which the report is received only during the month under report.

1.4

Sh0Wing eaCh type Of SpeCieS Of ma,aria Parasi,e as mentioned in the

ep it of the blood smears, i.e. number of cases showing Plasmodium vivax in the smear,

tber showing Plasmodium falciparum, number showing Plasmodium malariae and

number showing any other Plasmodium.

1.5 Enter number of fever cases given presumptive treatment for malaria by you.

1.6

ianrCMaler"

rad'Cal treatment by ,he Health Assis-

I

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—34

Smallpox :

2.1 Enter number of cases of fever with rash which you have detected and reported during

the month.

2.

2.2 Enter number of those cases of fever with rash which have been confirmed by the Medical

Officer as cases of smallpox.

2.3 Enter number of cases of smallpox contained during the month.

Cases

Cases of

of Other

Other Notifiable

Notifiable Diseases:

Diseases : Note

Note whether there have been cases of any other noti

fiable diseases in your area during the month and if so, specify which disease and what control

3.

measures have been taken.

TH. Vital Statistics

if Enter the number of live births of male children, female children and total children during

/

2.

the month.

Enter the number of deaths among males in each of the five age groups i.e °-l year, >1-5

years >5-15 years, >15-44 years and >44 years. Enter the number of deaths among females

in each of these age groups, and the total number of deaths in each of these age groups.

3.

S cify the signs and symptoms preceding death wherever the information is available but

especially in age groups 0-1 year and >1-5 years, and among pregnant women.

IV. Family Planning

1. Eruer the total number of eligible couples registered for your area at the end of the month.

NOTE ' " i sum of the total number of eligible couples stated by each of the two Health Wor

kers (Male) of the subcentre in their reports should equal the total number of eligible

couples stated by the Health Worker (Female) in her report.

2.

Use of Family Planning Methods :

area on whom vasectomy was performed during the

2.1 Enter the number of cases from your i

month.

area on whom tubal ligation (tubectomy) was per2.2 Enter the number of cases from your

formed during the month.

i • the

me uuiuwui

2.3 Enter

number vf

of cases from jyour areai in whom the intra-uterine device was inserted

during'the month. Give separate figures for the insertion of Lippes loop and Copper T.

2 4 Enter the number of pieces of Nirodh which were distributed to couples in your area during

the month (either at the subcentre, or by you on your home visits, or by the depot holders).

2.5 Enter the number of diaphragms fitted in your area during the month.

the number of tubes of jelly distributed to couples in your area during the month,

2.6 Enter

2.7 Enter the number of vials or packets of foam tablets distributed to couples in your area

during the month.

2.8 Enter the number of packets of oral contraceptives distributed to couples in your area

during the month.

3.

Depot Holders :

3.1 Enter the total number of depot holders of Nirodh in your area at the end of the month.

3.2 Enter the number of pieces of Nirodh distributed to the depot holders in your area during

the month.

I

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

V. Maternal,

1.

and

S—35

Child Health

Prenatal care :

1.1 Enter the new cases of pregnancy in the area during the month. Also enter the number

of cases of pregnant women carried forward from the previous month, i.c. all those who

have not yet delivered. Enter the total number of pregnant women in the area during the

month.

1.2 Enter the new cases registered in your area during the month for prenatal care. Also

enter the number of registered prenatal cases carried forward from the previous month,

and the total cases registered.

1.3 The Health Worker (Female) will enter the number of prenatal cases from her whole area

(intensive and twilight) referred to the Health Assistant (Female) during the month.

1.4 The Health Worker (Male) will enter the number of prenatal cases from the twilight area

referred to the HeaUh Worker (Female) during the month.

2.

Intranatal care :

2.1 Enter the number of pregnancies ending in live births, i.e. infants born alive—cases regis

tered (R) and cases not registered (NR).

..2 Enter the number of pregnancies ending in still birth, i.e. infants born dead—cases regis

tered (R) and cases not registered (NR).

2.3 Enter the number of pregnancies ending in abortion, i.e. pregnancy terminating prior

to the period of viability, viz., before 28 weeks of pregnancy.

2.4 Enter the number of pregnancies ending in Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP),

i.e. deliberate planned interruption of the pregnancy by the doctor before 28 weeks and

generally before 12 weeks.

In each case enter how many deliveries were conducted by the Health Worker (Female), by

trained dais, by untrained dais, and by other persons, e.g., medical practitioners in the area, or

female relatives. Enter how many pregnant women in the area were referred for delivery to

the PHC'/Hospital.

3.

Postnatal care :

3.1 Enter the number of cases from the area registered during the month for care after delivery.

3.2 Enter the number of ca^es or their husbands who accept a method of family planning during

the first six weeks after delivery.

4.

Infant care :

4.1 Enter the number of new cases of infants (zero to one year) from your area registered

during the month for infant care. Also enter the number of infants carried forward from

the previous month for infant care, and enter the total number of infants registered for

infant care.

5.

Care of pre-school children :

Enter the new cases of pre-school children (one to five years) registered during the month for

child care.. Also enter the number of pre-school children carried forward from the previous

month for child care, and enter the total number of pre-school children registered for child

care.

6. Nutrition :

6.1 Enter the number of cases of anaemia in mothers and in children detected in your area

during the month.

6.2 Enter the number of cases of anaemia in mothers and children referred for treatment to

the PHC during the month.

manual for health worker

Si-36

(female)

6.3 Enter the number of cases of malnutrition in mothers and children detected in your area

during the month.

6/ Enter the number of cases of malnutrition in mothers and children referred for treatment

to the PHC during the month.

6.5 For each of the groups mentioned, (i.e. pregnant and nursing mothers, children zero to

five yea. and family planning adopters to be given iron and folic acid, and children one to

five years to be given vitamin A solution), enter the number of new cases, carried forward

cases and total cases given nutritional supplements (i.e. iron and folic acid tablets, and

Vitamin A solution) during the month.

"

VI.

ONMENTAL SANITATION

1.

-nter the number of wells chlorinated in your area during the month.

2.

Enter the number of soakage pits constructed in your area during the month.

3.

Er er the number of latrines constructed in your area during the month.

4.

Enter the number of kitchen gardens started in your area during the month.

5.

Enter the number of compost heaps supervised by you in your area during the month.

Enter the number of smokeless chulhas installed in your area during the month.

7.

Enter the number of water pumps out of order in your area at the end of the month.

VU. Treatment of Minor Ailments

1.

2.

Enter the number of persons treated by you for various ailments, e.g., headache, cuts, burns,

etc. in the five age groups, i.e. 0-1 year, > 1-5 years, >5-15 years, >15-44 years and >44 years

in your area during the month.

Enter the number of persons from your area referred by you for treatment either to the PHC

or hospital or to a local practitioner.

VIH.

Health Education Activities

Enter the number of group meetings, mass meetings and film shows held by you during the month

and under the remarks column enter any relevant remarks, e.g., as to the topic of the meeting, atten

dance, reaction of the audience, etc.

IX.

Home Visits

1

Enter the total number of home visits made by you during the month.

2.

Enter the number of families visited by you during the month.

NOTE : You may visit the same family more than once during the month so that the number of

home visits paid will be more than the number of families visited during the month.

Other Activities

Mention any other activities carried out by you during the month, e.g., base-line survey of a

village, assistance in vasectomy camps, assistance in spraying operations, involvement in special

X.

campaigns for control of communicable diseases, etc.

Enter the date of completing the report, your name, designation and the name of your subcentre and PHC.

I

(

K

i

ANNEXURE 9.2

ANTEN^ AL CARD

Date of Enrolment

Age

PHC :

Card No.

Name

PREVIOUS PREGNANCIES :

Number

Pregnancy

Delivery

♦

♦

Puerperium

*

Result

Subcentre

Village No.

Address

Use abbreviations HISTORY OF PAST ILLNESS (TB, STD,

♦N = Normal

Heart, Diabetes, Abdominal Operation, etc.)

Place of

delivery By whom

C = Complicated

Home/

delivered

**L = Liveborn

Hospital

S = Stillborn

A = Abortion

LABORATORY TESTS :

Add (P) for

premature

c

tfl

2

tn

Z

H

O

>

z

d

£

"fl

o

73

TETANUS IMMUNIZATION

Date

Whether put on Iron tablets

PRESENT PREGNANCY : First day of last menstruation :

General Nutrition :

Anaemia :

Tongue :

Teeth :

Pyorrhoea :

Breasts :

Varicose Veins :

Bowels :

Institutional delivery recommended :

Reason for recommendation :

S

ra

>

YES/NO

Expected date of delivery

a

*

o

73

*m

73

Heart :

Lungs :

Liver :

Spleen :

Vomiting :

Oedema :

Vaginal discharge :

Bleeding :

M

2

>

S'

I

Contd.

Obs trie Examin tk is

Date

C*/H

Height

I

Weight

Urine

Hb.

B.P.

Week of ■ Fundal

Height

gestation

Presentation

Engaged-Free

Foetal

movements

Oedema

OO

>

%

♦C=Clinic

H=Home

■ Progress notes : Progress, complications, advice, drugs & diet supplements - treatment etc. given :

Signature

•n

o

X

Date :

TO

f

X

o373

7?

M

75

Delivery by PHC I 1 Subcentre CZZ]

Premature

Abortion IZ3

END OF PREGNANCY : Full Term

Dai I 1

Others (specify)

Mother : Alive I I

Died during labour 1 I Child : Alive I I

Still born

Died immediately after birth

POST NATAL EXAMINATION : (6 weeks after delivery) : Breasts, abdomen,

and child.

Family Planning adopted :

Card closed : Date :

Nirodh

Diaphragm

IUD

Sterlization |

Hospital E3

perineum, pelvic organs, lactation, general health of mother

| Others

(Mark the appropriate box.)

Signature

’ll

W

g

Pl

ANNEXURE 9.3

DELIVERY CARD

No.:

PHC

Subcentre

PREVIOUS PREGNANCIES

No.

Result

♦

Nat-re of

pregnancy

PN |—|

only

Date of

enrolment

Village No.

Name

A. N.

'ard No.

best ieFisetsssam joizj

Indiv. No.

Age

Nature of

delivery**

ANTENATAL CARE : By this PHC

other qualified |

c

■T3

| none

m

2

m

Z

BIRTH ATTENDANT (signature, designation)

Birth attendant called (day, hour)

In-patent, admitted (day, hour)

arrived

left

O

discharged

>

31

Z

d

£

General appearance

o

50

State of membranes

Show or vaginal bleeding

X

ra

I

|

>

qX

Week of gestation

o

5

MEDICAL EXAMINATION

50

nT

ra

2

>

•S*L = Liveborn

S = Stillborn

A = Abortion

LL = Liveborn

twins,

etc.

Add P for prematurity

**N = Normal

C = Complicated

Date and Signature

C/2

Contd.

L

LABO JR

Day

Hour

rwiiMi

i'emp.

Pulse

Urine

Contractions

intervals/

duration

Lie-

sentation

Enga

ged,

free

Foetal

heart

i

■cations, treatment (drugs).

Rectal or vaginal examination if necessary

Co i

z

c

o

75

s

SUMMARY OF LABOUR

MODE OF DELIVERY :

Other

£

Day

Hour

Onset of labour

o

Normal

Delivery of placenta

Spontaneous I

Complete

Delivery of membranes :

Complete

1

----

Rupture of membranes

assisted

incomplete I

incomplete I

I

I

Beginning of second stage

2

Delivery of child

rrt

Delivery of placenta

and membranes

Injury to mother

Abnormal blood loss I

75

m

I

Total time of labour

Contd.

(

THE BABY

LivebornO Stillborn

Sex

Birthweight

.

Medical care of baby

^raaraassE.

«s»- tjsssujbc

Eye propbylax's

Condition : Asphyxia; spina bifida, anencephalus, clubfoot, cleft palate/lip, polydactyly, etc.

co

C

PUERPERIUM

•xj

^3

FT}

Date

Temp.

z

zH

Date

4 2 -

Fundal height

41 o 8

6

4

2

Co

-

40 o -

8 6 -

O

Cm

z

14

>

I

12

10

39 o -

6

8 6 -

4

38 o -

37 o Z

8 6 -

38

q

o

5«

8

-

8

6

4

2

*TJ

x

o

2

5

Symphysis pubes

50

*n'

m

-

Z

>

r

«

Pulse

Lochia

Urine

Contd.

I

Child

Mother

"Date”*

or

plications, treatment, advice

rogress, oi p!

♦

Progress, complications, treatment, advice

Signature

g

z

C

•n

o

73

Condition on discharge

Condition on discharge

X

tn

POSTNATAL EXAMINATION 6 weeks after delivery (breasts, abdomen, perineum, internal examination, lactation, general health

of mother and child)

o

*

tn

73

Family Planning adopted : IUD I

I

tn

Nirodh

Diaphragm

died during labour

Cause of death :

Mother

Sterilization

Others

r

tn

Mother was alive 6 weeks after delivery

died within 6 weeks after delivery

L I

Unknown I ~1

Survival of liveborn child (ren)

after delivery (Twin)

7 days after : Alive

□□

[Alive

dead [—|j

dead

dead O

I I

[Alive

dead I

28 days after : Alive

O

dead

Child

Card closed date :

Signature

*C or H (Clinic or Home)

k

|]

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—43

ANNEXURE 9.4

CHILD CARD

PHC

Subcentre

Child Card No.

Mother’s Card No.

Name :

Religion :

Male/Female :

Number of brothers :

Date of birth :

Number of sisters :

Birth order :

Name of father :

Birth attendant :

Occupation :

Birth weight :

Name of mother :

Date of enrolment :

Occupation :

Address :

Milestones

Immunization® Date Date Date

Diseases

Yes* Age

Yes£ Age

Holds head up

Measles

Sits

Chickenpox

Smallpox

Examng.

of scar

Revaccination

Smallpox

B.C.G.

Crawls

Diphtheria

Teething

Whooping Cough

Stands without support

Typhoid fever

ED

Examng.

of scar

D.P.T.

Keratomalacia

Walks without support

Speaks syllables

(Triple)

D.T.

Marasmus

Feeding :

Kwashiorkor

Typhoid

Fed on breast milk

Poliomyelitis

Supplement introduced EZ]

Others (specify)

Milk

Pulscs/Cereals

Laboratory examinations—Dates & results

Fruits/Vegctabies

Breastfeed stopped

Eats family food

EZJ

Family Planning Status of Parents :

♦Mark x/in the box if the milestone is observed and give the age in months.

£Mark y/in the box if the child suffered from the disease and give the age at which it suffered.

©Enter the date on which the inoculations were given and dates of examining the scars.

Mention if the parents are practising F. P. If so, the method. If not the action taken.

This card should be maintained from birth to five years of age.

Contd.

S—44

Femember

to examine

the

following

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

♦

Date

C/H

Height

in cm

Weight Findings-diagnosis-advice & treatment

in kg

Fontanelle

Eyes

Fars

Nose

Throat

Mouth

Teeth

Feeding

Bowels

Nutrition

Skin

Muscles

Clands

Genitals

Walk

Speech

Cleanliness

aess

F. . Status

of parents

I

*C—Centre

H—Home

Contd.

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—45

CHILD CA-RD---- CONTINUATION CARD

Remember

to examine

the

following

V-

Fontanelle

Eyes

Ears

Nose

Throat

Mouth

Teeth

Feeding

Bowels

Nutrition

Skin

Muscles

Glands

Genitals

Walk

Speech

C' uanliness

Illness

F.P. Status

of parents

*C—Centre

H—Home

♦

Date

C/H

Height

in cm

Weight Findings-diagnosis-advice & treatment

in kg

1

I'l

s-

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

ANNEXURE 10.1

House

EHHble

Couple Number

Number

ELIGIBLE COUPLE

Name of Husband (H)

Name of Wife (W)

Age

Address

Number of living

children

H

M

u

F

W

(I)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(0

(7)

I

I

I

S—47

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

REGISTER

Age of Pregnant.

youngest novv

child

with sex Yes No

(8)

(9)

Whether using i. If yes,

family pan

method

ning method (s) used

ii. If no,

Yes

reasons

No

(10)

(U)

Remarks

Date

(12)

(13)

Obser

vations Date

Obser

vations

(15)

(16)

(14)

■

S—48

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MAINTAINING ELIGIBLE COUPLE REGISTER

The Eligible Couple Register is intended to keep a record of all currently married women

between the ag:s of 15 to 44 years. The objectives of the Eligible Couple Register are :

i.

To find out the eligibility of the couples for family planning.

11.

To identify the priority groups of couples for various methods in order to approach

them for motivation and ultimate adoption of the method.

iii.

To follow up the acceptors of the various family planning methods in order to find

out about the regularity of use, satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the method, and

complaints as a result of the use of the method.

i

/

I

In this Register particulars of all the currently married women in the age group 15 to 44 years

should be entered. The missing information should be collected during the course of the follow

up of contacts. During these visits the particulars collected earlier may also be verified.

Absence of the wife to visit her parental home, or the husband for employment in another

place, constitute only a temporary separation. In such cases the spouse present should be inter

viewed. Guests and casual visitors to the house should not be interviewed and should not be re

corded in this register.

At the time of conducting the initial survey, three copies of the Eligible Couple Register

should be prepared village-wise, of which one set should be kept by the Health Worker (Male),

One should be given to the Health Worker (Female), and one should be kept at the Primary Health

Centre. Additional pages should be left blank for entering future additions to the eligible couple

list. A separate Eligible Couple Register should be kept for each village for easy reference.

i

The Eligible Couple Register should be updated at least once a year.

Column 1 : Eligible couple number : This should be a running number starting from one (1)

‘ the village where survey is undertaken. For instance if there are 250 couples in a village, the

k .her will start from 1 and end at 250. If there are more than one couple in the house, where the

wife’s age is between 15 to 44 years, each couple should be given a separate number and the

rticulars of all the couples in the house should be entered separately, one line of the register being

allotted to each couple.

Column 2 : House number : If the houses have already been numbered by the panchayat for

the malaria programme, the existing number of the houses should be recoided. If the houses aic

not numbered, all the houses should be serially numbered. These numbers should be painted on

small iron plates, which should be fixed on the right-hand upper corner of the main door frame of

inch house. In case iron plates are not available the number should be painted in fast colour

on the right-hand upper corner of the door. The same number should be entered in this column.

Column 3 : Name of Husband) Wife : The name of the husband along with the name of the

should be given in this column. The name of the husband should be written above the line

ar^

u of the wife below it. If the husband has more than one living wife staying with him, her

r.. jc should also be entered below the first wife’s name.

■

C. ./< 4 . Address : The full address indicating the street, lane and village should be entered.

T-- - -’’ess should be complete so as to facilitate the location of the house in subsequent visits for

follow-up.

Column 5 : Age of Husband) Wife : In this column, the age of the husband should be entered

in complete years above the line and that of his wife below it.

SUPPLEMENT TO

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—49

Columns 6 and 7 .• Number of living children : The number of living children, male and female,

should be entered irrespective of the fact whether or not they are living with the couple. If the

person has marricu more than cnce, the number of living children from all marriages should be en

tered and the fact of two or three marriages should be given in the remarks column. If the hus

band has more than one wife living with him, the number of children from the second wife should

also be mentioned separately against her name.

Column 8 : Age of youngest child with sex : The age of the youngest child should be entered

in years and months and the sex of the child may be indicated by ‘M’ for males or ‘F’ for females

after the age. For instance, if the age of the youngest child, who is a boy, is found to be three years

4

and four months, it should be written as : 3-|2_M

Column 9 : Pregnant now 'Yes' or 'No' : The entry should be ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ according to

whether 05. not the wife is reported to be pregnant.

Column 10 : Whether using family planning method(s) : The entry should be ‘Yes’ or ‘No*.

Column 11 ; If the reply to W is ‘Yes’, it means that the wife/husband is sterilized, or the wife

is fitted with an IUD, or the couple is using some other method. This fact should be indicated by

the following abbreviations :

(1) Vasectomy

V

(2) Tubectomy

T

(3) Intra-utcrine device

IUD

(4) Nirodh (condom)

N

Foam tablet

FT

(5)

(6) Jelly/Cream

J

(7) Diaphragm

D

(8) Safe period or rhythm

R

(9)

Withdrawal

W

If the reply to column 10 is ‘No’, it means that the couple is not using any method and, there

fore, the reason(s) should be indicated in brief (for the investigator's guidance only). The reason(s)

for not using family planning methods may be of the following types : (i) sterility, (ii) wanting a

child, (iii) ill health of husband or wife, or (iv) husband away for long period.

she

Column 12 : Remarks : In this column any relevant observations, not covered elsewhere,

be recorded.

Columns 13 and 15 : Date : The date along with the month and year on which a suosequent

visit for follow-up is made, should be entered.

Columns 14 and 16 : Observations : After the completion of the Eligible Couple Register, the

couples should be followed-up at regular intervals. Observations with regard to regularity of use

of a method, difficulties in use, complications as a result of the use, and other problems of the couples

should be noted in this column. Observations such as ‘Neither of the spouses found at home’,

‘4 iouse locked’, ‘Loop expelled’, ‘Discontinued using Nirodh’, ‘Changed method’, etc.,

which may be found on subsequent visits should also be recorded here. Any other observation

not covered in previous columns may be entered here, e.g., if any advice or method is given; if one

of the spouses is sterilized, the date of sterilization; if an IUD is fitted, the date of insertion; if

separated, the date of separation; if one of the spouses has died, the date of death.

S—jO

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

NOTE : If a family has shifted from the area, the serial number of the family in column 1

should be circled. The fact that the old family has vacated the house should be

mentioned in the remarks column. In case a new family has occupied the vacant

house, the entry of the new family should be made after the last entry in the Eligible

Couple Register and a new serial number should be assigned. In order to facili

tate cross reference, the serial number of the new family should also be indicated

in the remarks column against the old family. For instance, the family living

in house number ‘X* at serial number 19 has left the area and a new family has occu

pied the house and has been entered at serial number 507. The entry in the remarks

column against serial number 19 will read as follows :

‘Family left the area. Particulars of new family occupying house number ‘X*

given at serial number 507’.

1

SUPPLEMTs r TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—51

ANNEXURE 11.8

FORMS A, B AND C FOR VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY PROPHYLAXIS

PROGRAMME

Form A :

.C

REGISTER OF BENEFICIARIES UNDER THE VITAMIN ‘A’ DEFICIENCY

PROPHYLAXIS PROGRAMME

SI.

No.

Date of

Regis

tration

Child

Card

No.

Name

(1)

C2)

(3)

(4)

Address Age Date of Administration Remarks Initials

of the

1 2 3 456789 10

worker

(5)

(6)

(7)

(9)

(8)

I

Form 8 : STOCK REGISTER OF RECEIPTS AND ISSUES OF VITAMIN

o

‘A’ SOLUTION

Date

Receipt

Issue

Balance

Remarks

Initials

(I)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S- -52

PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST BLINDNESS IN CHILDREN

VITAMIN ‘A’ DEFICIENCY

Form C :

19

eport for the month ending

CAUSED BY

for the State of.

Statement of Beneficiaries

Category

Age of children

(years)

No. covered during

the month

Progressive total

for the year

Remarks

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

i

i

I

1-2

(I) Children

given

1st

2-3

3-4

i

4-5

(Total 1-5 yrs.)

1-2

(2) Children

given

2nd dose

2-3

3-4

4-5

(Total 1-5 yrs.)

(2)

Position Regarding the Receipt and Issue of the Drug

!

. -ling Mance

o the 1st day of the

nth in mill'htres

(1)

Receipt during

the month in

millilitres

Issued during

the month in

millilitres

(3)

(2)

On hand on the last

day of the month in

millilitres

(4)

Remarks

(5)

♦

j

Age break-up of children may be given. If the break-up is not available then the total children

in 1-5 years age group should be given.

Place

Signature

Date

Designation

I

S—53

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

J

ANNEXURE 11.9

I

J

FORMS A, B AND C FOR NUTRITIONAL ANAEMIA PROPHYLAXIS

PROGRAMME

Form A :

SI.

No.

REGISTER OF BENEFICIARIES UNDER THE NUTRITIONAL ANAEMIA

PROPHYLAXIS PROGRAMME

Card

No.

(2)

(1)

Date

of

enrol

ment

Name

(3)

(4)

Age

Category

Mother Child

(5)

(6)

(?)

Family

Planning

accep

tor

Date of Re

cessa marks

tion of

treat

ment

(8)

(9)

(10)

)

I

Initials

of

worker

I

(H)

!

I

i

Form B :

STOCK REGISTER OF IRON AND FOLIC ACID TABLETS

Date

Receipt

Issue

G)

(2?

(3)

Balance

i

Initials

■

(4)

(5)

I

ik J

I

I

I

I

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—54

Form C :

PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST NUTRITIONAL ANAEMIA AMONG MOTHERS

AND CHILDREN

Report for the month ending

(D

£

• ’ .*

'■'h

19

'i

for the State of

Statement of Beneficiaries

SI.

No.

Category of

beneficiaries

(2)

1.

Mothers

2.

F.P. cases

No. on

1st day

of the

month

No. of

cases

enrolled

during

the

month

No. of

cases

dropped

during

the

month

No. of

cases

remain

ing at

the end

of the

month

Progres

sive

total for

the year

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6!

(7)

Remarks

•:

(8)

1

t

■IUD

Tubectomy

1

Others

3.

Children

der 5

years of

age)

i

3

4.

1

Position of Receipt and Issue of the Drug

O :mng balance

on the first day

of the month

Receipts during

the month

Issues during

the month

On hand on

the last

day of the

month

Remarks

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

>•

1' .i'.

■

L

Signature

Date

Designation

• _

MGIPLP(FBD)-101/M of H*FW (ND)/77------ 22-11-78------- 25,000

■

■uJ

APPENDIXES

A—1.3

1 enema can with tubing, connector, clamp and rectal tube

18. Plastic mackintosh (1 metre square)

19. Plastic apron

20. Soap dish with soap

21. Towel

22. Nail brush

23. Torch

24. Safety pins

25. Baby weighing spring scale

26. Containers for drugs :

17.

\

i. 5 plastic bottles of suitable sizes with water-tight caps for liquid medicines

ii. 1 amber coloured bottle with dropper cap

iii. 3 plastic containers of suitable sizes for tablets, powders and ointments.

27. Kit box

28. Medicines :

For internal use

i. Ergot tablets

ii. Mist chloral hydrate

iii. Injection methyl ergometrine maleate (methergen).

For external use

iv. Antiseptic lotion

v.

vi.

vii.

viii.

ix.

x.

Liquid paraffin

Mercurochrome 2 %

Methylated spirit

Silver nitrate eye drops 1 %

White vaseline

Zinc boric dusting powder.

APPENDIX 2

LIST OF ALLOPATHIC MEDICINES USED AT SUBCENTRE LEVEL

2.1

MEDICINES TO BE CARRI^p BY HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

For Internal Use

1. Aspirin, Phenacetin and Caffeine (APC) tablets

2. Belladonna and phenobarbitone tablets

3. Chloroquine tablets

4. Dried aluminium hydroxide tablets

5. Ergot tablets

6. Iron and folic acid tablets

7. Magnesium hydroxide tablets

8. Magnesium sulphate

9. Mepyramine (Antihistamine tablets)

10. Mist bismuth kaolin

11. Phthalyl sulphathiazole tablets

12. Piperazine citrate tablets

13. Rehydration powder

14. Tincture codeine co.

15. Triple-sulpha tablets

16. Vitamin A solution

For External Use

17. Antiseptic lotion

18. Benzoic salicylic ointment

19. Benzyl benzoate emulsion

20. Ephedrine nasal drops

21. Gentian violet 2%

22. Mercurochrome 2 %

23. Methyl salicylate liniment

24. Potassium permanganate crystals

25. Silver nitrate eye drops 1 %

26. Sulphacetamide eye and ear drops 10%

27. Sulphanilamide skin ointment

28. Sulphonamide dusting powder

29. Tetracycline eye ointment

30. White vaseline

Reagents

31. Benedict’s qualitative reagent

32. Acetic acid 5%

2.2

MEDICINES TO BE KEPT AT SUBCENTRE

For Internal Use

1. Biphenium hydroxy-naphthoate granules

2. Calcium gluconate tablets

3. Liquid paraffin

4. Mist, alkaline

5. Mist, carminative

6. Mist, chloral hydrate

7. Mist, sedative expectorant

8. Multivitamin tablets (A, B, C, D)

I

1

A—2.2

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

9.

10.

Prochlorperazine tablets (emidoxyn)

Syrup ferric citrate

11. Vitamin C tablets

12. Injection methyl ergometrine maleate (methergen)

For External Use

13. Boric acid powder

14. Calamine lotion

15. Methylated spirit

16. Tincture benzoin co.

17. Tincture iodine

18. Zinc boric dusting powder.

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR

HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

ANNEXURE 4.1

HOUSEHOLD AND FAMILY RECORD

General Information

I.

1.

House No. :

2.

Village :

3.

Name of PHC :

4.

Block :

5.

District :

6.

State :

7.

Name of head of family :

8.

Religion :

9.

Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe :

10.

SI.

No.

19.

11.

Name

of

family

member

12.

Rela

tion

ship

to

head

of

family

Source of income :

13.

14.

Age

Sex

Non-vegetarian >—.

(fish or meat) —

|

18.

Re

marks

per month

19.2 casual employment :

19.3 self employment :

Rs.

Rs.

per month

per month

Rs.

per month

Dietary habits of family :

Partly vegetarian 1

(eggs)

17.

Occu

pation

Rs.

19.5 Barter payment :

Purely vegetarian

16.

Edu

cation

19.1 regular employment :

19.4 Total

20.

15.

Mari

tal

status

S—2

II.

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

Immunization Status

1.

SI.

No.

2.

Smallpox

3.

B.C.G.

Pock Pri Revac 1st Booster 1st

marks mary cinat

vac ion*

cina

tion

(2.1) (2.2) (2.3) (3.1) (3.2) (4.1)

4.

D.P.T.

5.

Poliomyelitis

2nd Boos 1st 2nd Boos

and ter

and ter

3rd

3rd

7.

6.

Other

T.T.

(specify)

in

pregnancy

1st 2nd

(4.2) (4.3) (5.1) (5.2) (5.3) (6. 1) (6.2J

* Within the last 3 years

III.

Maternal and Child Health

1. Mother :

1.1 No. of times pregnant :

1.2 Pregnant at present :

1.3 If yes, duration of pregnancy

1.4 Presence of anaemia :

1.5 Under treatment for anaemia :

Yes

No

weeks

Yes

Iron and folic acid :

Yes

Yes

Other :

Mild

1.6 Presence of malnutrition : Absent EZJ

1.7 Under treatment for malnutrition :

Yes

2. Children (0-5 years) :

2.1 Presence of anaemia :

2.2 Under treatment for anaemia :

Yes CZI

Iron and folic acid :

Yes I |

Yes

Other :

Mild F I

2.3 Presence of malnutrition : Absent

2.4 Getting nutritional supplements : Vitamin A solution

Yes □□

Yes O

Other :

No

CZJ

No

No

Severe

No

No

No

No

Severe i

:

No

No

I

SUPPLEMENT TO

S—3

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

Family Planning

IV.

1. No. of living children : Male

2. Age of last child :

3. Couple eligible for family planning :

4. Use of Family Planning Methods :

SI.

No.

Family Planning

Methods

Ever

used

Yes

(2)

(1)

Female

Years

Yes

Period

of use

Presently

using

(4)

(5)

Total

Months

ZJ No

Discon

tinued

Since

when

Reasons

for dis

conti

nuing

(6)

(7)

(8)

No

(3)

4.1 Vasectomy

4.2 Tubal ligation

4.3 Intra-uterine

device

4.4 Oral contraceptive

4.5 Condom (Nirodh)

4.6 Diaphragm

4.7 Jelly

4.8 Foam tablets

4.9 Other

4.10 No method used at present

4.11 No method ever used

4.12 Remarks :

V.

Environmental Sanitation

1.

House :

I 1

f I

Reason

Reason

1.1 Pucca : with thatched roof

without thatched roof

1.2 Kutcha : with thatched roof

without thatched roof

1.3 No. of rooms :

2.

Smokeless chulha used :

Yes

3.

Water supply :

3.1 Community supply

3.2 Source :

Tap

3.3 Source : Sanitary

3.4 Storage of water :

Pump |

4.

Sanitary

No

|

|

|

Household supply CZJ

Well I | Other (specify)

Insanitary QU

Insanitary | |

Excreta disposal :

4.1

Household latrine

Communal latrine Q

4.2 Type of latrine : latrine with water seal I I

latrine without water seal | |

bucket latrine | |

other (specify)

4.3 Sanitary | |

Insanitary

No latrine |

facilities

|

/

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

5.

6.

Sullage water disposal

5.1 Soakage pit :

5.2 Kitchen garden :

5.3 Open drain :

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

EZI

Sanitary

Sanitary

Sanitary

□□

Insanitary

Insanitary

□□ Insanitary

EZJ

Refuse disposal :

6.1 Method :

6.2 Sanitary

composting

| |

1 1

Insanitary

burning

tipping

7. Livestock and poultry :

7.1 Livestock kept on the premises :

7.2 Maintenance and housing of livestock :

7.3 Poultry kept on the premises :

7.4 Maintenance and housing of poultry :

Yes

I—I

Sanitary I I

Yes

Sanitary | |

No

I—I

Insanitary

No

O

Insanitary I I

VI. Communicable Diseases

SI. No.

Disease

(1)

(2)

1.

Tuberculosis

2.

Leprosy

3.

Trachoma

4.

Malaria

5.

Filariasis

6.

Sexually transmitted

diseases (specify)

Date :

Name of persons in

household known to

be suffering from

the disease________

(3)

Under treatment Treatment dis

continued

since when

since when

(4)

Name of the Health Worker :

Designation :

Subcentre :

PHC :

(5)

supplement to

manual for health worker

(female)

HOUSEHOLD AND FAMILY RECORD FOLLOW-UP SHEET

Date of follow up

I.

General Information

10 to 18. Change in

family members :

II.

Immunization

2 to 7. Change in

immunization status :

2. Smallpox

3. B.C.G.

4. D.P.T.

5. Poliomyelitis

6. T.T.

7. Other (specify)

III.

Maternal and Child Health

1.2 Wife pregnant :

Yes

No

IV.

Family Planning

3. Couple eligible for

family planning :

Yes

No

4. Family Planning method

presently used :

4.1 Vasectomy

4.2 Tubal ligation

4.3 Intra-uterine device

4.4 Oral contraceptive

4.5 Condom (Nirodh)

4.6 Diaphragm

4.7 Jelly

4.8 Foam tablets

4.9 Other

4.10 Nil

I

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—6

Date of follow up

V.

Environmental Sanitation

Change in environmental

sanitation :

1. Housing

2. Smokeless chulha

3. Water supply

4. Latrine facilities

5. Sullage water disposal

6. Refuse disposal

7. Livestock and’ poultry

VI.

Communicable Diseases

Change in persons in house

hold suffering from follow

ing communicable diseases :

1. Tuberculosis

2. Leprosy

3. Trachoma

4. Malaria

5. Filariasis

6. S.T.D.

Remarks

Signature

SUPPLEMENT TO

S—7

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMPLETING HOUSEHOLD

AND FAMILY RECORD

This form is to be filled in for each household in your area during the initial or base-line

survey. The information is meant to give you a comprehensive picture of each family—its socio

economic status, the size of the family, the health of the family members, and the environmental

conditions in which the family lives.

A family unit consists of the husband, his wife and children. Besides the family unit, other

relatives, e.g., an aged parent or an unmarried brother or sister, who are permanently residing in

the house, are also included in the household. If a married son or daughter or a younger married

brother or sister continues to reside in the house with his or her spouse and/or children, a separate

form should be filled for each family unit under the same household number. For example, if

there are three family units in household No. 77, there will be three Household and Family Record

Forms numbered 77A, 77B and 77C, and on form 77A a note will be entered: ‘See forms 77B-77C*.

I.

General Information

1. Enter the house number if it has already been numbered, e.g., by the malaria survey.

If there is no number, mark your own number on each house and use this number in your record.

2-6. Enter the name of the village, the location of the PHC which covers the area, and the

block, district and State in which the PHC is situated.

7. Enter the name of the husband.

8. Enter the religion of the family, e.g., Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Jain, Parsi, Neo

Buddhist, etc. If the husband and wife belong to different religions, mention, e.g., Hindu (H)/

Muslim (W).

9.

Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe : Strike off whichever does not apply.

10. & 11. Enter all the members of the family unit starting with serial number 1 as the

husband (head of the family), then the wife, and unmarried children. Add any other relatives (not

forming separate family units) who are permanently residing in the household.

12. Enter the relationship of each family member to serial No. 1, i.e. wife, daughter, brother,

mother, father-in-law, etc.

13. Mention age in years or, if below two years, in years and/or months.

able, mention date of birth.

Wherever avail

14.

State whether Male (M) or Female (F).

15.

State whether Married (M), Single (S), Widowed (W) or Divorced (D).

16.

State level of education completed up to date, i.e.

Post-graduate degree, e.g., M.A. (Soc.).

ii.

Graduate degree, e.g., B.Ed.

iii.

College level, e.g., 1st Year Arts.

iv.

School level, e.g., S.S.C. or 9th Std.

17. Mention actual occupation, e.g., farmer, weaver, shopkeeper, teacher, etc. In the case

of a woman who is not earning, mention ‘housewife*. In the case of children attending school or

college, mention ‘attending school’ or ‘attending college’.

i

I

S—8

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

18. Remarks : Any relevant remarks may be entered against any particular family member,

e.g., as regards his or her state of health, occupation, impending marriage, etc.

A specimen form may read as follows :

10.

11.

12.

1.

2.

\a!^

3.

So-n

4PahA/iJc

16.

13.

14.

41

A7

SSC

F

75^.

15.

I(d

3

/Z

S

64

F

h/

17.

18.

ScK&trC

Ndi

19. State approximate earnings of the family in rupees per month against one or more of the

types of employment listed.

19.1

Regular employment : e.g., those in service or holding regular jobs with a monthly

salary, such as teachers, clerks, factory workers, etc.

19.2

Casual employment : e.g., those who arc daily wage labourers, porters, etc.

19.3

Self employment : e.g., those who have their own business such as shopowners,

farmers, potters, etc.

19.4

Total : The total income of the family in rupees (/>. 19.1, 19.2 and 19.3) is cal

culated.

19.5

Barter payment, i.e. payment in kind in exchange for work, e.g., grain, vegetables,

etc.

20. Check off in the appropriate box whether the family is purely vegetarian, i.e. no eggs,

meat or fish are eaten by any member of the family unit, or partly vegetarian, i.e. the diet consists

mainly of cereals, vegetables and fruit but eggs are eaten by some or all members of the family unit,

or non-vegetarian, i.e. meat or fish are eaten by some or all members of the family unit.

11.

Immunization Status

1.

2.

The same serial numbers as in Section I should be used.

Smallpox :

2.1 Pock marks : Mention whether or not the individual has pock marks (state ‘yes’

or ‘no’).

2.2 Primary vaccination : Indicate whether or not primary vaccination has been given

as ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and, where available, mention the date. Check for scars of primary

vaccination and note if they are seen.

2.3

3.

Revaccination : Note whether or not the person has been revaccinated within the last

three years and mention ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

B.C.G. vaccination :

3.1 First dose : indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where available, mention

approximate date.

SUPPLEMENT TO

3.2

4.

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S-9

Booster dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’), and, where available,

mention approximate date.

Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus (Triple) vaccination :

4.1 First dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where available, men

tion approximate date.

Second and third doses : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where

available, mention approximate date.

4.3 Booster dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where available,

mention approximate date.

5. Poliomyelitis vaccination :

5.1 First dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where available, mention

the date.

5.2 Second and third doses : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where

available, mention the date.

5.3 Booster dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes' or ‘no’) and, where available,

mention the date.

Tetanus

Toxoid in pregnancy :

6.

6.1 First dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where available, men

tion the date.

6.2 Second dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no') and, where available, men

tion the date.

6.3 Booster dose : Indicate whether given or not (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and, where available,

mention the date.

4.2

7.

Other :

Indicate any other immunization which the individual may have had during the

last 12 months, e.g., Typhoid, Cholera, etc., and, where available, mention the date.

Maternal and Child Health

III.

1.

2.

Mother :

1.1

Mention the total number of pregnancies of the wife, including those that ended

in live births, still births, spontaneous or induced abortions. If the wife is pregnant

at the time of survey, the present pregnancy should also be included.

1.2

Check of! whether or not the wife is pregnant at present.

1.3

If yes, mention the period of pregnancy in weeks.

1.4

Check off whether or not the wife is anaemic as judged by the colour of the con

junctiva, lips and nails. If haemoglobin estimation has been carried out, note the

haemoglobin level.

1.5

1.6

Check off whether or not the wife is receiving iron and folic acid tablets or any other

treatment for anaemia.

Check off whether malnutrition is absent or present and if the latter, whether mild or

severe. Presence of malnutrition would include any of the symptoms, viz., cracks

at the corners of the mouth, red glossy tongue, presence of rickets or osteomalacia, etc.

1.7

Check off whether or not the wife is receiving treatment for malnutrition.

Children (zero to five years), i.e. from birth up to and including the 5th birthday :

2.1

Out of the total number of children aged zero to five years in the family unit, include

in each box the number who have anaemia and the number who do not.

S—10

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

2.2

Include in the appropriate box the number of children who arc under treatment for

anaemia (i.e. either receiving iron and folic acid tablets or syrup, or any other treat

ment), and the number who are not.

2.3

Include in each box the number of children who do not have malnutrition and the

number who have mild or severe malnutrition. The presence and degree of mal

nutrition may be gauged by measuring arm circumference.

Include in the appropriate box the number of children who are getting nutritional sup

plements (vitamin A solution or other nutritional supplements) and the number who

are not.

Family Planning

2.4

IV.

1.

Enter in the appropriate box the number of male, female and total living children.

Note the age of the youngest living child in years and months.

3. Note whether or not the couple is eligible for family planning, i.e. they are currently

married and the wife is between 15 and 44 years of age.

4. Against each method of family planning, note whether or not the method has ever been

used and if so, the duration of use, and whether it is still being used or has been discontinued, Jf

the method has been discontinued, note since when it has been discontinued and the reason for

discontinuing.

A specimen form may read as follows :

4. Use of Family Planning Methods :

o

SI. No.

Family Plan

ning Method

Ever used

Yes

(1)

(2)

Vasectomy

Tubal ligation

Intra-uterine

device

4.1

4.2

4.3

I YZ|

Diaphragm

Jelly

Foam tablets

Other

V.

(5)

Disconti- Since

nued

when

I

No method used at present

No method ever used

Remarks : yo

| (3

(6)

Reasons

for dis

conti

nuing

(8)

(7)

□

E]

4.6

4.12

(4)

(3)

Oral contraceptive I I

Condom (Nirodh) |v/~|

4.10

|4.11

Presently

using

No

4.4

4.5

4.7

4.8

4.9

Period

of use

‘—I

as

Reason:

Reason :•

Environmental Sanitation

1. Housing : Check off whether pucca : i.e. built of bricks, wood, cement or stone, with or

without a thatched roof, or kutcha : i.e. built of mud, straw, tin sheets, etc. with or without a

thatched roof.

SUPPI.FMFNT 1O

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—11

Mention the number of rooms (separated by walls or partitions).

2.

Smokeless chulha used: Mention whether or not the house has a smokeless chulha.

NOTH : If tho household is using some other form of fuel, c.g., gobhar gas or a kerosene stove,

make a note of this.

3.

Water supply :

3.1

Check off whether the household has its own water supply or uses the common water

supply of the village.

3.2

Check off whether the water used by the household comes from a tap, pump, well

(tube well or ordinary well) or other source (specify whether a pond, river, reservoir,

canal, etc.).

Check off whether the source of water supply is sanitary or insanitary.

3.3

3.4

4.

Check off whether the water is stored by the household in a sanitary or insanitary

way.

Excreta disposal :

Check off whether the household has its own latrine, or uses a common latrine or has

no latrine facility at all.

4.2 If there is a household or common latrine, check off whether the latrine is one with

a water seal, one without a water seal, or a bucket latrine. If it is of some other type,

specify.

4.3 Check off whether the latrine used by the household is sanitary or insanitary.

4.1

5.

Sullage water disposal :

5.1 Check off whether or not the household has a soakage pit and if so, whether or not it

is sanitary.

5.2 Kitchen garden : Check off whether or not the household has a kitchen garden and

if so, whether or not it is sanitary.

5.3 Open drain : Check off whether or not the household has an open drain to carry off

sullage water and if so, whether or not it is sanitary.

6.

Refuse disposal :

6.1 Check off the method of disposal of refuse, whether by composting, burning, or

tipping.

6.2 Note whether the method used is sanitary or insanitary.

7.

Livestock and poultry :

Check off whether or not livestock are kept on the premises.

If yes, check off whether or not the maintenance and housing of livestock are sani

tary.

7.3 Check off whether or not poultry are kept on the premises.

7.4 If yes, check off whether or not the maintenance and housing of poultry are sani

tary.

7.1

7.2

VI.

Communicable Diseases

If there are any persons in the household suffering from tuberculosis, leprosy, trachoma,

malaria, filariasis or specific sexually transmitted diseases, note in column 3 the name of each person

suffering from the disease, in column 4 whether the patient is under treatment and if so, since when,

and in column 5 whether the patient has discontinued treatment and if so, since when.

NOTE : If any particular disease is endemic in an area and information on the incidence

of the disease is required, it can be added to section VI.

S—12

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

Fill in the date on which the household has been interviewed, your name and designation,

and the location of your subcentre and PHC.

HOUSEHOLD AND FAMILY RECORD FOLLOW-UP SHEET

In order to keep your records up to date it is necessary to enter any new information as regards

general socio-economic conditions, immunization status, use of family planning methods, inforn. ion regarding MCH, environmental sanitation and communicable diseases of the households

in your area. A follow-up sheet is provided with columns in which at regular intervals, e.g.,

monthly or three monthly, you can enter any new information gathered since the time of the base

line survey. All information collected on a particular visit is entered in one column. The numbers

for e?ch item are the same numbers used in the Household and Family Record.

I.

General Information

10-18. Any changes in the household since the last visit are recorded, e.g., the birth of a baby,

or the death of a family member, or the marriage of a son or daughter, brother or sister. In the

last case, if the newly married couple is staying in the household a separate form with the same

household number will be prepared.

II.

Immunization

2~7. Note if any more family members have received any of the immunizations listed.

III.

Maternal and Child Health

1.2 Note whether or not the wife is pregnant.

IV.

Family Planning

3.

4.

V.

Note whether or not the couple arc still eligible for family planning.

Note what family planning method is presently used by the couple.

Environmental Sanitation

1-7. Note any change in housing, the acquisition of a smokeless chulha, any improvement or

deterioration in source of water supply, the construction of a latrine, the construction of a soakage

pit, or the commencement of a kitchen garden, and a change in method of refuse disposal or in the

maintenance and housing of livestock and/or poultry.

Communicable Diseases

1-6. Note if any family member previously suffering from tuberculosis, leprosy, trachoma,

malaria, filariasis or specific sexually transmitted diseases has completed or has interrupted treatment,

or if any other family member is now suffering from one of these diseases.

VI.

Enter any pertinent remarks and your signature.

S—13

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

ANNEXURF. 4.2

VILLAGE RECORD

I.

General Information

1.

Name of village:

3.

Block_____

6.

Distance from subcentre:

7.

Distance from PHC‘

8.

Date of commencement of

9.

Date of completion of

2.

4. District:

5. State:

base-line survey:.

base-line survey:

10.

Total number of households;

12.

Population according to religious group :

Others

13.

11.

Muslim

Hindu

Total number of families:

Christian

Sikh

Total

Population according to age and sex :

SI. No.

Age group

Male

Female

Married

(13.1)

(13.2)

(I)

0-1 year

(2)

>1-5 years

(3)

>5-15 years

(4)

>15-44 years

(5)

>44 years

(6)

Total

14.

Subcent rc:

(13.3)

Total

Unmarried

(13.4)

(13.5)

Number of couples according to number of living children :

SI. No.

Number of living children

(14.1)

(14.2)

(I)

0

(2)

1

(3)

2

(4)

3

(5)

4

(6)

5

(7)

6 and above

(8)

Total

Number of couples

(14.3)

I-

■

.

S—14

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

15. Private medical practitioners :

Qualifications

Address

SI. No.

Name

System

(15.1)

(15.2)

(15.3)

(15.4)

(15.5)

SI. No.

Name

Trained

Untrained

Address

(16.1)

(16.2)

(16.3)

(16.4)

(16.5)

16. Dais :

17. Community leaders and Community Health Workers:

SI. No.

Name

(17.1)

(17.2)

Occupation/Designation

(17.3)

Address

(17.4)

18. Depot holders (Nirodh) :

SI. No.

Name

Sex

(18.1)

(18.2)

(18.3)

Occupation/Designation

(18.4)

Address

(18.5)

19. Community resources and agencies (Youth Club/Mahila Mandal/Bhajan Mandal/Young

Farmers’ Club/Drama Club/Balwadi/Cooperative, etc.)

SI. No.

Type of resource

Address

(19.1)

(19.2)

(19.3)

I

. j"

supplement to

manual for health worker

Facilities

Address

(I)

(2)

(3)

20.1

Primary Schools

20.2

Secondary Schools

20.3

Post Office

20.4

Police Station

20.5

Panchayat Office

20.6

Places of Worship

20.7

Other (specify)

SI. No.

21.

Communications :

21.1

Village connected to subcentre by :

pathway

bus route |

other (specify)

]

Village connected to PHC by :

road

21.3

S—15

Public facilities :

20.

21.2

(female)

bus route

train

waterway 1

other (specify)

I

Nearest telephones available :

Address

(1)

21.4 Village electrified :

II.

Family Planning

1.

Total number of eligible couples

Telephone number

(2)

Yes

No EZ1

S—16

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE.)

Couples presently using family planning methods :

2.

SI.No.

Method

(1)

O)

Number of couples currently practising with number of living

children

0

(3)

2.1

Vasectomy

2.2

Tubal ligation

2.3

Intra-uterine device

1

(4)

2

(5)

3

(6)

4

(7)

5

(8)

6+

Total

(9)

(10)

Oral contraceptive

2.5

Condom (Nirodh)

2.6

Diaphragm

2.7

Jelly

2.8

Foam tablets

2.9

Other (specify)

2.10

Nil

III.

Immunization Status of Community :

1. Smallpox

Pock Primary

Marks vacci

nation

(2)

(0

3. D.P.T.

2nd Booster

and

3rd

(3)

(I) (2)

_2. B.C.G.

1st Booster 1st

Re

vacci

nation*

(I)

(3)

(2)

4. Poliomyelitis

1st

Booster

2nd

and

3rd

(3)

(1) (2)

* Within the last 3 years.

IV.

Environmental Sanitation :

1.

Housing :

1.1 Pucca : with thatched roof

without thatched roof

1.2 Kutcha : with thatched roof

without thatched roof

2.

Source of water supply :

2.1

Number of wells :

Household :

Communal :

sanitary

insanitary

total

sanitary

insanitary

total

I 1

EH

EH

EE

I I

EZJ

5. T.T. in

pregnancy

2nd

1st

(1)

(2)

SUPPLFMFNT IO

2.2

Number of pumps :

S—17

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

Household :

in working order

out of order

total

in working order

out of order

total

Comnuinal :

2.3

Number of ponds/tanks :

2.4

Other sources (specify) :

protected

unprotected

total

protected

unprotected

total

3.

Number of latrines :

(1)

Type

(2)

3.1

Latrine with water seal

3.2

Latrine without water seal

3.3

Bucket latrine

3.4

Other (specify)

SI. No.

Household

(3)

Communal

(4)

Total

(5)

3.5

Number of households with no latrine :

4.

Number of households with soakage pits :----------sanitary

insanitary □□

Number of households with kitchen gardens :

sanitary

insanitary Q]

Number of households with open drains :

sanitary

ihsanitary 1

5.

6.

7.

Number of households with smokeless chulhas :

Date :

Name of health worker :

Designation :

Subcentre :

PHC :

1

S—1ft

MANUAL LOR IIFAI.TH WORKER (I FMAI.E)

VILLAGE RECORD FOLLOW-UP SIIEI I

Date of follow-up

I.

General Information

10.

Total number of

households

11.

Total number of

families

12.

Population

religionwise :

Hindu :

Niuslim :

Christian :

Sikh :

Others :

Total :

13.

Population

agewise :

Male

Female

Married

Unmarried

Male

Female

Married

Unmarried

0-1 year

>1-5 years

>5-15 years

> 15-44 years

>44 years

I

Total

14.

Number of

couples with

living children :

0 child

1 child

2 children

3 children

i

I

I

4 children

Contd.

SUPPLEMENT TO

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

S—19

5 children

6 or more

children

Total

15.

Change in private

m c d i ca I practitioners

16.

Change in dais

17.

Change in community

leaders and Community

Health Workers

18.

Change in depot

holders (Nirodh)

19.

Change in community

resources and agencies

20.

Change in public

facilities

21.

Change in communi

cations

II.

Family Planning

I.

Total number of

eligible couples

2.

Couples presently

using family

planning methods

No. of couples currently

practising with number

of living children

0 1 2 3 4 5

6+ Total

No. of couples currently

practising with number

of living children

0 1

2 3 4 5 6-]- Total

2.1 Vasectomy

2.2 Tubal ligation

2.3 I.U.D.

2.4 Oral contraceptive

2.5 Condom (Nirodh)

Contd.

S—20

2.

MANUAI. FOR Hr.Al.TlI WORKER (fEMAT.E)

Couples presently

using family

planning methods

No. of couples currently

practising with number

of living children

0 1 2 3 4 5

6 + Total

No. of couples currently

practising with number

of living children

0 1 2 3 4 5 64 Total

2.6 Diaphragm

2.7 Jelly

2.8 Foam tablets

2.9 Other (specify)

2.10 Nil

111.

Immunization Siatus

of Community

Number of persons

protected by :

I.

Smallpox vaccination :

1.1 Pockmarks

1.2 Primary vaccination

1.3 Revaccination

2.

B.C.G. :

2.1 1st dose

2.2 Booster

3.

D.P.T. :

3.1 1st dose

3.2 2nd and 3rd doses

3.3 Booster

4.

Poliomyelitis :

4.1 1st dose

4.2 2nd and 3rd doses

4.3 Booster

Contd.

SUPPLEMENT TO MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

5.

S—21

Tetanus Toxoid :

(in pregnancy)

5.1 1st dose

5.2 2nd dose

IV.

Environmental Sanitation

I.

Housing :

1.1 Pucca :

1.2 Kutcha :

2.

Thatched

Not thatched

Thatched

Not thatched

Water supply:

2.1 No. of wells

Household

Communal

Household

Communal

Sanitary :

Insanitary :

Total :

2.2 Number of pumps:

in order :

Out of order :

2.3 No. of Ponds/Tanks :

Protected :

Unprotected :

i

2.4 Other sources :

Protected :

Unprotected :

3.

Number of Latrines :

3.1 With water seal :

Household :

Communal :

Total :

Contd.

S—22

MANUAL FOR HEALTH WORKER (FEMALE)

3.2 Without water seal :

Household :

Communal :

Total :

3.3 Bucket latrine :

Household :

Communal :

Total :

3.4 Other (specify) :

Household :

Communal :

Total :

3.5 Number of households

with no latrine :

4'

Number of households with

soakage pits :

Sanitary :

Insanitary :

5.

Number of households with

k.tvhen gardens :

Sanitary :

Insanitary :

6.

Number of households with

open drains :

Sanitary :

Insanitary :

7.

Number of households with

smokeless chulhas :

Remarks

Signature

Designation

1

suphtment to manual for health worker

(female)

S—23

INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMPLETING VILLAGE RECORD

This form is to be filled in for each village in your area and is a summary record of all the