WOMEN'S SPECIFIC PROBLEMS-MENOPAUSE/MENSTRUATION/BREST CANCER/WOMEN & MENTAL HEALTH

Item

- Title

- WOMEN'S SPECIFIC PROBLEMS-MENOPAUSE/MENSTRUATION/BREST CANCER/WOMEN & MENTAL HEALTH

- extracted text

-

RF_WH_5_SUDHA

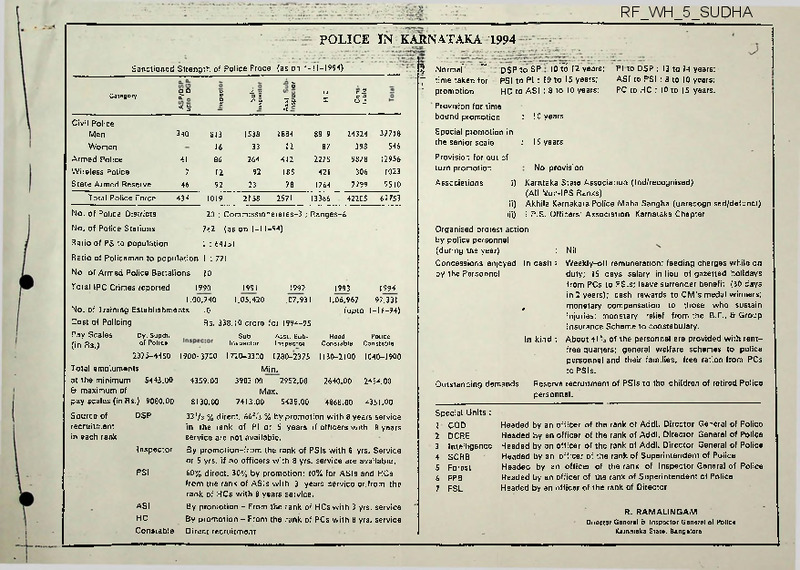

POLICE IN KARNATAKA 1994

Sanctioned Strength of Police Froce (as on l-l 1-1994)

Category

5

DO

XJ o

q

|

£7

< §■

Civil Police

Men

Women

Armed Police

Wireless Police

State Armed Reserve

Total Police Force

340

41

7

46

434

12

92

1019

Provision for time

bound promotion

:

10 years

:

IS years

306

7299

Provision for out of

turn promotion

231

421

1764

12956

1023

9510

Associations

2158

2571

13366

42205

1 : 64151

61753

(as on l-l1 -94)

10

1990

1991

1992

1.00,740

1.05,420

1.07,931

No. of Training Establishments

10

Cost of Policing

Rs. 338.10 crore for 1994-95

Pay Scales

Dy. Supdr.

Sub

Asst. Sub

inspector

Inspector

(in Rs.)

o’Poli«

2375-4450 1900-3700 I720-33C0 1280-2375

Total emoluments

Min.

at the minimum

5443.00

4359.00

3983.00

2952.00

& maximum of

Max.

pay scales (in Rs.) 9080.00

8130.00

5438.00

7413.00

ASI

HC

Constable

ASI to PSI : 8 to 10 years;

PC to HC : 10 to 15 years.

9878

Ratio of Policeman to population 1 : 771

PSI

PI to DSP : 13 to 14 years:

DSP to SP

2275

12

Ratio of PS to population

Inspector

10Y6 12 years:

PSI to PI : 10 to 15 years;

HC to ASI : 8 to 10 years;

412

185

78

742

DSP

"

37718

546

No. of Police Stations

Source of

recruitment

in each rank

time taken for

promotion

24324

398

20 ; Commissionerates-3 ; Ranges-6

No. of Armed Police Battalions

Normal'

7

'

8819

87

1884

No. of Police Districts

Total IPC Crimes reported

5

Special promotion in

the senior scale

1538

33

264

92

813

16

86

||

c 2.

c X)

02

o

—

—

1994

1993

1,06,967

97,331

. (upto 1l-l1-94)

Head

Constable

Police

Constable

1130-2100

IC40-I900

2640.00

2454.00

4868.00

4351.00

33’/s % direct, 662,'s % by promotion with 8 years service

in the rank of PI or 5 years if officers with 8 years

service are not available.

By promotion-from the rank of PSIs with 8 yrs. Service

or 5 yrs. if no officers with 8 yrs. service are available.

60% direct. 30% by promotion; 10% for ASIs and HCs

from the rank of ASIs with 3 years service or.from the

rank of HCs with 8 years service.

By promotion - From the rank of HCs with 3 yrs. service

By promotion - From the rank of PCs with 8 yrs. service

Direct recruitment

No provision

i)

ii)

iii)

Karntaka State Association (Ind/recognised)

(All Non-IPS Ranks)

Akhila Karnakata Police Maha Sangha (unrecognised/defunct)

I.P.S. Officers' Association Karnataka Chapter

Organised protest action

by police personnel

(during the year)

: Nil

Concessions enjoyed In cash : Weekly-off remuneration; feeding charges while on

by the Personnel

duty; IS days salary in lieu of gazetted holidays

from PCs to PSIs; leave surrender benefit (30 days

in 2 years); cash rewards to CM’s medal winners;

,

monetary compensation to those who sustain

injuries; monetary relief from the B.F., & Group

Insurance Scheme to constabulary.

In kind : About 41 % of the personnel are provided with rentfree quarters; general welfare schemes to police

personnel and their families, free ration from PCs

to PSIs.

Outstanding demands

Reserve recruitment of PSIs to the children of retired Police

personnel.

Special Units :

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

COD

DCRE

Intelligence

SCRB

Forest

FPB

FSL

Headed by an officer of the rank of Addl. Director General of Police

Headed by an officer of the rank of Addl. Director General of Police

Headed by an officer of the rank of Addl. Director General of Police

Headed by an officer of the rank of Superintendent of Police

Headed by an officer of the rank of Inspector General of Police

Headed by an officer of the rank of Superintendent of Police

Headed by an officer of the rank of Director

R. RAMALINGAM

Director General & Inspector General of Police

Karnataka State, Bangalore

IsJxzYl

b;

d)

WOMEN’S GRIEVANCE REDRESSAL CELL

OR

CRISIS CENTRE

m^]0AL LMK0EIHE

MULTI^CmARYPRO^

(MULTI-DEPARTMENT; MULT!-A GENCY)

rDEPT OF WOMEN &CWLD DEVELOPMENT

1. WELFAR^DFPT. OF SOCIAL WELFARE

COMPONENTS:

“—DIALLER SYSTEM ("HELPLINE")

- ----- &-

COUNSELLING CENTRE

(FACE TO FACE COUNSELLING)

SHELTER (INDEPENDENT/HOUSES)

'-WOMENS DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

„

p

vCORPS. OF DETECTIVES [DOWRY SELL)

-WOMENS POLICE STATIONS

Zpoue£--city police

-POLICE HEAD QUARTERS

... OPTIONAL:

SECRETARIAT/RESEARCH CELL

TO CO-ORDINATE WITH

GOVT. DEPTS-oS-SW DEPT

-POLICE DEPT

-LAW DEPT

-COLLEGES

-HOSPITALS etc....

(b)

NGO’s AND

^WOMEN’S

VOLUNTEERS [ ORGANISATIONS

H>SERVICE ORGANISATIONS

U>U.NJCOMMON WEALTH

I AGENCIES

^INDIVIDUAL VOLUNTEERS

LkCCHDI C’C

REPRESENTATIVES

•MEDIA PERSONS

rLAW DEPT

AXA, -LEGAL AID BOARD

^'LAW --LAWFEARS

'-NATIONAL SCHOOL OF LAW

-N! MNANS

~UTY DEPT.

4.PSYCW'-CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGISTS

Q^pp^yMARRIAGE COONS ELLERS

'-PRACTICING PSYCHOLOGISTS

-WOMEN& ORGANIZATIONS

S.NGQs -rlNDimUAL'vDLUNTEE^S

-GROOFS W0RHHV6 FOR WOMEN

STRUCTURE

|

(A)

ADVISORY COUNCIL

(B)

CORE GROUP (MONITORING BODY)

(C)

RESOURCE PERSONNEL

(experts to analyse DATA and ADVlS;7also

for FACE TO FACE COUNSELLING)

(D)

PRIMARY COUNSELLORS

(Trained volunteers to receive call and for

I

CONFRONTING DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

(DOWRY RELATED & OTHERWISE)

STAGE AND NATURE OF INTERVENTION

CATEGORY-1 WORSTPOST INCIDENT

‘POLICE

INVESTIGATION

OF CRIME CASE

(FACILITY ALREADY

IN POLICE)

CATEGORY-II

stage counselling)

* Ambulance (or Link with Ambulance

facility)

Shelter (or link with facility for Shelter^

Rehabilitation)

By

Way

of

CATEGORY - III HOPEFUL - WOMAN UNDER

EXTREME STRESS

4 Counselling cubicles

* Record maintenance system

SOURED RELATIONSHIP

* INTERVENTION

i)

COUNSELLING

ii)

LEGAL AID

iii)

SHELTER

IV) POLICE HELP

SNFRA STRUCTURE

* Telephones & cabins

BAD -

(INTERVENTION MOST BENEFICIAL

PERHAPS LIFE

SAVING)

A SPONSORED CRISIS

CENTRE

MULTI - DISCIPLINARY

MULTI - DEPARTMENT

MULTI - AGENCY PROJECT

HERBAL MEDICINES FOR GYNEACOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

l-J H "

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL, BANGALORE

I

MENSTRUATION:

1.

Amenorrhoea-

* Grita Kumari (Aloe barbadensis)- Take the fleshy part of the

Iraves; wash it in water few times,, mix with jaggery and eat

in empty stomach in the morning for five days.

* Papaya (Carica Papaya)- Take papaya milk from the fruit; add

2-3 drops with misri (sugar candy-'kalla sakkare').

Consume

it for seven days continuously twice daily.

* Jamun (Euginia; Jambolana)- Take the juice or decoction of

Jamun bark after diluting with water twice daily for about

seven days continuosly.

Cotton plant- Take a decoction of 20 grams each of flowers aid

leaves of the Cotton plant (500 ml. of water boiled to half

its quantity) mixed with 20 grams of jaggery to induce menstrual

flow.

" 125 grams of each of the following ingredients

skb

like sesame

seeds, tender shoots of the cotton plant and tender shoots of

bamboo plants and 220 grams of aged jaggery are to mixed with

the powder and pea-sized pills are prepared.

Take these pills

one at a time with warm water every morning and evening .

■ A good simple formula is shatavari and ashwagandha taken two

parts each, and turmeric and ginger one part each, using one

teaspoonful of the powder per cup of warm water.

Neem- Drink 1 tola of the juice of the tender leaves of neem

for about a month.

A decoction of the bark is also useful.

Onion- Eating the bulbs raw has been noticed to bring about a

desirable regularity in menstruation among women.

It ife is

a case where menstruation does not occur or is obstructed five

I

tolas of onion are cooked in one ser of water till the latter is

reduced to about ten to twenty tolas.

jaggery.

Then add 3 tolas of

This is to be made hot and drunk by the patient for

a few days.

Other reciepes are: three tolas of onion juice

are made luke warm and drunk before going to bed at night.

Or, ten tolas 1 of onion are cut into small pieces, garam

masala is added to it and the whole is roasted in ghee and

eaten.

The obstructed menstruation will become rectified.

2.

DYSMENORRHOEA;

* Kumari-asava which is a given to the patient in a dose of 6 tea

spoonfuls, twice daily after food with equal quantity of water.

* Raljah pravardhani which contains borax in bhasma form, asafoetida- ./>

and kumari, is also an effective drug.

Two tablet

I

* Add sufficient quantity of asafoetida to the food of the patient

which can be given in powder form.

For this it can be fried with

fixisd ghee or butter in a big spoon over fire, this makes it brittle

and powder can be made out of it conveniently.

This powder should

be taken in a dose of 1 teaspoonful twice daily along with food.

It should be followed by hot water.

Because of the pungent smell

it emits, some people do not like to take it alone.

It may be

added with butter milk or vegetables or rice or bread and taken

by the patient.

* Grind the leaves of bitter gourd with some pepper and garlic.

Take this once a day for three days.

* Take the juice of 'karaila'or hacjala kayi loz, once a day for

7 days.

* Make a decoction of somph, avala and jaggery of about 1/2 a cup

twice a day for 30 days.

* Boild the leaves of Arusha(Adathoda Vasica) in a glass of water

and reduce it to half.

From the first day of menses drink in the

morning in empty stomach for 5 days.

* Boil few leaves of Babul TulsiC'nayi tulsi")

in a glass of water

and drink thrice a day.

* Give the powder of the tneder leaves of tamarind 1 tsp with honey

twice a day for 7 days.

3.

MENORRHAGIA:

* Seeds of unripe mango fruit is cut into pieces, fried in ghee,

mixed with sugar and the whole stuff is made into a pill mass.

Several pills are made out later and these are given in stipu

lated doses.

The kernel of the seed is powdered and given in

stipulated doses of 20 to 30 grains with or without, honey.

Fluid extraction of the Park or an infusion of the bark is

•

curative too.

* A drink of the juice of plantain flowers mixed with curds acts

as a curative to young girls suffering from excessive bleeding.

* Burn some amount of coconut coir into ashes- Take a teaspoonful

of the ash, mix it well in tender coconut water, add small

auantity of sugar candy and administer this drug twice a' day

for young girls.

* .Asoka and lodhra are popularly used for the treatment of this

condition.

Thepowder of the bark of these drugs,

is given to

the patient either separately- or in a compound form in a dose of

one teaspoonful four times a day, with cold water.

* The tender leaves of pomegranate along with seven grains of rice

are made to a paste and given to the patient twice daily for a

month.

This works both as a preventive as well as curative

medicine.

* Two grams of each of these ingredients are taken and ground

together: dry (stone) ginger,-gum from the bark of a nemm tree,

ajwan seeds, tamal patra, and equal amounts of the five parts of

the Tulsi plant.

The powder so prepared is boiled in 100 grams

of water till one-fourth of the water remains.

be taken regularly.

The extract should

If excessive flow accompanies dizziness.

Tulsi juice mixed with honey will give quick relief

OLA^

Mx)C

<u_AdZatL

CL

V^v-voouiy

CO^v/zaJ-^

• 5>«o.

2_ ^LjSLcji.^

po rv-^y-VioLf-^^

-4Za£cHu

G^ZZ^

i^zvcZjL

cLdj-i ■

C)^2-2.-

Joouncu^L

^QlcJC

£t<fl

CLVO<Qtad ■

Zf^GO^WOM :

jjJ.■

Oi^Apj^

€ul>-

xUClcLa

cow

ex.

• K^-rvyjVOve.

4^1

'L^JcJL. J<Z-Z.C<2-

uli^cL

,

UajjCL AVvQL-UIX

-ZjO

Acb(_^-

, Cl/\gL

“ZZve

■CLlCLOCHC^,

EVy^'

^O\JLC>UC^

<'

aetF\JL (^GiaJLUXZ AjIOl/V-^

DCU_.UCt2A

, _

O>xZ

-^ci,

YY'^i_a.L-i

'T^e.

.

04

cLsJ

Cucjojjq

<2

£L

cUCl6l<

cQiZxo'

c<fioLc> oict

u

a>AC/

*u.a5jv)

-CK£.

COlcac/gC

<0? lAe.

%

Cl

JJLlzLo.

Zkn'XtM-/

<XOloCaoL '/rj

, >-tXo.. LocveXi •

^CldL?

cLtCa

o^o)

- CJCJduccu ^oea)

i^oZAl

XciQ<ix, •

c^uiook-vie,,

J^jud^Vd^ooa. ■

c<j-A

T^\a3

Zs.

UjOQiJJj

cLucU^o,^ $

''Ikj.i cRoa-ii ©

^■oJJ ‘

Qth&r. rkoQUS

UJG, obibcuc-Ko

0'--Uo+Aj2x

HERBAL MEDICINES FOR GYNEACOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL, BANGALORE

I MENSTRUATION:

1. Amenorrhoea-

* Grita Kumari (Aloe barbadensis)- Take the fleshy part of the

l&aves; wash it in water few times, mix with jaggery and eat

in empty stomach in the morning for five days.

* Papaya (Carica Papaya)- Take papaya milk from the fruit; add

'

2-3 drops with misri (sugar candy-'kalla sakkare').

Consume

it for seven days continuously twice daily.

* Jamun (Euginia; Jambolana)- Take the juice or decoction of

Jamun bark after diluting with water twice daily for about

seven days continuosly.

' AxdHSOKfcisnxsfxSBxgxaniBX

Cotton plant- Take a decoction of 20 grams each of flowers ard

leaves of the Cotton plant (500 ml. of water boiled to half

its quantity) mixed with 20 grams of jaggery to induce menstrual

flow.

125 grams of each of the following ingredients kkh like sesame

seeds, tender shoots of the cotton plant and tender shoots of

bamboo plants and 220 grams of aged jaggery are to mixed with

the powder and pea-sized pills are prepared.

Take these pills

one at a time with warm water every morning *^nd evening .

A good simple formula is shatavari and ashwagandha taken two

parts each, and turmeric and ginger one part each, using one

teaspoonful of the powder per cup of warm water.

Neem- Drink 1 tola of the juice of the tender leaves of neem

for about a month.

A decoction of the bark is also useful.

Onion- Eating the bulbs raw has been noticed to bring about a

desirable regularity in menstruation among women.

It it is

a case where menstruation does not occur or is obstructed five

tolas of onion are cooked in one ser of water till the latter is

reduced to about ten to twenty tolas.

jaogery.

Then add 3 tolas of

This is to be made hot and drunk by the patient for

a few days.

Other reciepes are: three tolas of onion juice

are made luke warm and drunk before going to bed at night.

Or, ten tolas 1 of onion are cut into small pieces, garam

masala is added to it and the whole is roasted in ghee and

eaten.

The obstructed menstruation will become rectified.

DYSMENORRHOEA:

Kumari-asava which is a given to the patient in a dose of 6 tea

spoonfuls, twice daily after food with equal quantity of water.

Ratyah pravardhani which contains borax in bhasma form, asafoetida ■/.

and kumari, is also an effective drug.

Two tablet

!

Add sufficient quantity of asafoetida to thg food of the patient

which can be given in powder form.

For this it can .be fried with

fried ghee or butter in a big spoon over fire, this makes it brittle

and powder can be made out of it conveniently.

This powder should

be taken in a dose of 1 teaspoonful twice daily along with food.

It should be followed by hot water.

Because of the pungent smell

it emits, some people do not like to take it alone.

It may be

added with butter milk or vegetables or rice or bread and taken

by the patient.

,

>

5 /

* Grind the leaves of bitter gourd with some pepper and garlic.

/Take this once a day for three days.

'

* Take the juice of *karaila’or hagala kayi loz, once a day for

7 days.

* Make a decoction of somph, avala and jagaery of about 1/2 a cup

V

twice a day for 30 days.

* Boild the leaves of Arusha(Adathoda Vasica) in a glass of water

and reduce it to half.

From the first day of menses drink in the

morning in empty stomach for 5 days.v

* Boil few leaves of Babul Tulsi('nayi tulsi')

in a glass of water

and drink thrice a day.

* Give the powder of the tneder leaves of tamarind 1 tsp with honey

'/ twice a day for 7 days.

3. MENORRHAGIA:

* Seeds of unripe mango fruit is cut into pieces, fried in ghee,

mixed with sugar and the whole stuff is made into a pill mass.

Several pills are made out later and these are given in stipu

The kernel of the seed is powdered and'given in

lated doses.

stipulated doses of 20 to 30 grains with or without honey.

Fluid extraction of the Park or an infusion of the bark is

curative too.

*,.A drink of the juice of plantain flowers mixed with curds acts

as a curative to young girls suffering from excessive bleeding.

* Burn some amount of coconut coir into ashes- Take a teaspoonful

of the ash, mix it well in tender coconut water, add small

nuantity of sugar candy and administer this drug twice a- day

for young girls.

* Asoka and lodhra are popularly used for the treatment of this

condition.

Thepowder of the bark of these drugs,

is given to

the patient either separately- or in a compound form in a dose of

one teaspoonful four times a day, with cold water.

* The tender leaves of pomegranate along with seven grains of rice

are made to a paste and given to the patient twice daily for a

month.

This works both as a preventive as well as curative

medicine.

* Two arams of each of these ingredients are taken and around

X

together: dry (stone) ginger,-gum from the bark of a nemm tree,

ajwan seeds, tamal patra, and eaual amounts of the five parts of

the Tulsi plant.

The powder so prepared is boiled in 100 grams

of water till one-fourth of the water remains.

be taken regularly.

The extract should

If excessive flow accompanies dizzin&ss.

Tulsi juice mixed with honey will aive guick relief

-to

ok(.o(.+f'pn.

J+lJ^Asd

<kj\cl

'■LI'ka. P<jl>..\cLqa.

T

‘tca^ iS ku^zu; Jii tA^.^o'^oa. t •

v-Cka

U j^LCAUu vjQLLLe

o^XG.c tf'.o^

■Zh.Q

pAj4-C£> t-\J

ZOnAjjj

^.'d_i.c.c. ■

<_ CuJ tea •

oui

<l‘^lcA.

CW

DLU'V.a.

rJrLi./y

(. ist'.'l th

-a

aguxZ.

lCJLu

V||| ■k&J’-

u '^> b<i.

Q.

^Xol.d.tld. drj

''t ^J~l

xt-tL^x<iJ.a.l£.( -Clu.

-U.o ttx..-0/A.

\(

tuo^ z pv-o^zvo&s

ol^e.e-A(b^

V

^dJ-C^

AP^-cZaZ/J"

V

Qth&r,

Qj-v-vO

55

ozxo ce.Acoxf-

<S)rv • l^bkt

AJdPQSQjd

yOaxj/tLuJAA vU /Uyoycxjced

lZ©

Cuajl pcvC^uUL pcU,

kJ H

HERBAL MEDICINES FOR WOMEN— CHC, BANGALORE

I MENSTRUATION

1.

Excessive Bleeding:

.

* Amarantus Spinous(Kannada- •mullu dantu', Telugu- 'attamullu

goranta, nalla doggeli') is used in checking excessive

menstrual flow.

* Drinking of 1 tola of the juice of the tender leaves of neem

are helpful.

* Fried Hibiscus (’dasavala'

in Kannada) in ghee is helpful.

* Seeds of unripe mango fruit is cut into pieces, fried in

ghee, mixed with sugar and the whole stuff is made into a

pill mass.

Several pills are made out later and these are

given in stipulated doses.

The kernel of the seed is powdered

and given in stipulated doses of 20 to 30 grains with or w

without honey.

Fluid extraction of the bark or an infusion

of the bark is curative too.

* A drink of the juice of plantain flowers mixed with curds

acts as a curative to young girls suffering x from excessive

bleeding.

* Xa Burn some amount of coconut coir into ashes- Take a

teaspoonful of the ash, mix it well in tender coconut water

■1s '

add small quantity of sugar candy and administer this drug

twice a day for young girls who suffer from excessive bleeding.

4% mashas each of the gum and marking nut(geru)(Kikar or

Gum Arabic, Acacia Arabica*:jali, karijali, bauni in Kannada)

should be given grinding them along with water.

Asoka and lodhra are popularly used for the treatment of

this condition.

The powder of the bark of these drugs, is

given to the patient either separately or in a compound form

in a dose of one teaspoonfijl four times a day, with cold

water.

Asoka-arista and

•

Asoka-arista and lodrasava are given to the patient in a dose

of one ounce twice daily after food with an equal quantity of

water.

, *zThe tender leaves of pomegranate along with seven grains of•

raice are made to a paste and given to the patient twice

daily for a month.

This works both as a preventive'as well

as curative medicine.

* Pravala and mukta are used in acute attacks of this disease.

They are given in a powder form which is called pisti.

One

grain of the powder of this drug is given to the patien four

times a day. '

* Diet: Old rice, wheat, moong dal, milk and ghee can £>e 'given.

Sugarcane juice, grapes, jack-fruit, banana, amalaki, pome

granate, are very useful.

Hot and spicy things are to be

strictly avo.tdedj

Two grammes of each of these ingredients are taken and ground

together: dry (stone) ginger, gum from the bark of a neem

tree, ajwan seeds, tamal patra, and equal amounts of the

five parts of the Tulsi plant.

The powder so prepared is

boiled in 100 grammes of water till one-fourth of the water

remains.

The extract should be taken regularly.

If excessive

flow accompanies dizziness, Tulsi juice mixed with honey will

give quick relief.

■ * Equal weights of Pathani Lodh, Ochre(Ger) and Oak Galls(Mazu)

should be finely powdered and four grams of it taken in the

morning and evening with milk.

* Half ripe fruits of the country Fig tree(Gular) shduld be

dried in the shade, powdered and mixed with an equal quantity

of sugar.

Six grams of the powder taken with-milk in the

morning and evening gives.

Alternatively, three grams of

Rasaut and an equal quantity of Shellac should be finely

-2-

ground together and made into two dosffs, one to be taken with

milk in the morning and evening.

* Dry Amla should be soaked in juice of green Amla for three

days and then ground into powder.

Six grams of this powder

taken with cow's milk for some days cures the condition.

Other remedies recommended afe:

10 grams each of Selkhari

(Talk) and Geru(Red Ochre) ground together should be taken

in three grams doses thrice daily.

Multani Mitti(Bole

Armeniac) steeped in water and the supernatant water drunk

in the morning is also good for excessive bleeding from the

womb.

Five' grams of bark of £ Kurchi and raw Sugar mixed

together taken' in the' morning and evening is also an

effective’remedy.

* Grind t'ogether the leaves of Mehandi(Lawsonia alba), Bhumi

avala(Phyllantus Niruri) and the rind of the anar fruit

(Punica granatum) and make pills.

stomach in the morning.

Dose: 1 day in empty

The' juice or decoction of the same

also' can be used.'

* Cut a ripe banana at the centre and put one small spoonful

of alum powder and eat in empty stomach in the morning for

2-3 days.

* Half a cup of the Jamun Ju'ice, to be taken twice daily for

five to seven days.

Mix one teaspoonful of dhania' powder in the water in which

rice has been washed.

Dose: 1 glass for a day.

I HERBAL MENSTRUATION

DYSMENORRHOEA- Painful

2.

* Fresh mint chutney or mint decoction is given to decrease

menstrual cramps.

For very severe dysmenorrhoea a decoction

of •Brahmamanduki• leaves is used in rural India.

These

leaves rich in Vellarin is a known sedative and anti

A fist-ful of the leaves boiled in a pint of

spasmodic.

w't'er, and given as a decoction in doses of an ounce «

thrice a day helps to relieve the discomfort in menses.

p Kumari-asava, which is an given to the patient in a dose of

6 teaspoonfuls, twice daily after food with equal quantity

of water.

Rajah pravardhani which contains borax in bhasma

form, asafoetida and kumari, is also an effective drug.

Two tablets of this medicine are given to the patient, twice

a day for about 7 days,immedietly before the due date of

menses.

It relieves congestion in the pelvic organs, works

as a laxative and thus keeps the patient free from any pain

during menstruation.

Add sufficient quantity of asafoetida to the food of the

patient which can be given in powder form.

For this it can

be givEnxtBxthexpatiHHtxxixxaxpHw fried with ghee or butter

in a big spoon over fire, this makes it brittle and powder

can be made out of it conveniently.

This powder kh should be

taken in a dose of 1 teaspoonful, twice daily along f with

food.

It should be followed by hot water.

Because of the

pungent -sSMre it emits, some people do not like to take it

alone.

It may be added with butter milk or vegetables or

rice or oread and taken by the patient.

*/

Grind the leaves of bitter gourd with some pepper and garlic.

Take this once a day for three days.

One hundred grams of juice of green leaves of Bleak Night-

*

shade( Mako) and leaves of Chicory (Kasni) should be placed

on fire and when it coagulates, it should be strained and

drunk after mixing 20 grams of Gur with it.

*

Twenty grames of the leaves of the following eight herbs are

boiled in water: ±k

i)

Sambhalu (Indian Wild Pepper);

Sahinjana(Horse

ii)

iii)

Radish);

Bakayan (Indian Lilac);

iv)

Kasni (Wild Chicory);

v)

Mako (Black Nightshade);

vi)

Khatmi (Marsh Mallow);

vii)

Narma Kapas (Cotton Plant);

viii)

Soya(Dil).

When the leaves are cooked and the water evaporated, they should

be fried in Sesame Oil like any vegetable and tied to the

lower abdomen like a pultice.

It will deal effectively with

inflammation.

* A decoction of root of Cotton Tree(18 grams), Telia Geru

(6 grams), leaves lof Rose Bush (6 grams). Root of Chulai

(6 grams), Gur (24 grams) boiled in 750 ml. of water till one

eight is left.

The decoction should be taken for three days

continuously.

v/*'rake the juice of ‘karaila* loz l/dayx7days.

/■'"Ta Make a decoction of spmph, aval a and jaggery.

cup

2/day x 30 days.

^/Boil two leaves of Arusha (Adathoda Vasica) in a glass of

water and reduce it to half.

From the first day of menses

drink in the morning in empty stomach for 5 days.

Boil few leaves of Babul Tulsi (Occimum basilacum) in a

glass of water and drink 3/day.

* Heat in mustard oil 5 tender leaves of Kujur (Malkanguni:

Celastrus Paniculata). Take 1 tea sp ful 2/day for 21 days.

* Root decoction of Kapas (Gossypium'indicum) 4 oz. 3/day x

7 days.

* Take Kujur oil 3 drops in Honey 1/day x 21 days.

frGive the powder of the tender leaves of imli (tamarind) 1

tsp with honey 2/day x 7 days.

-3I MENSTRUATION:

3. Amenorrhoea- Absence

*prita Kumari (Aloe barbadensis); take the fleshy part of the

leaves; wash it in water few times, mix with jaggery and eat

in empty stomach £ in the morning for 5 daiys.

* XakexanyxsfxkhExstHnsKaixKiadiEiMHsxniEFitiHnEdxxH

Pappaya milk

(Carica Pappaya) from the fruit 2-3 drops with misri (sugar

candy) 2/day x 7 days.

* The juice or decoction of Jamun bark (Euginia; ffJambolana)

Juice after diluting with water 2/day x 7 days.

■ Prepare a paste of the tuber of Kalihari (Gloriosa superba)

and apply over the supra pubi'c region for two hours.

Apply

same paste on the forehead also for the whole night .

* Give the decoction of the seeds of gajer with jaggery 1

tabj.e sp ful 1/day x 7-15 days

* The infusion or decoction of the root of Kapas (Gossypium

Indicum) is given with honey or jaggery in the morning in

empty stomach, and in the evening Dose:

2-4 oz.

A week before theperiods of a woman are due, a decoction of

six grams of Fl^j Seeds (about 250 mi. of water reduced to

half through boiling) mixed with 20 grams of jaggery and 20

grams -of ghee should be taken daily.

Alternatively, a decoc-

tion of ten grams of seeds of Carrots and jaggery should be

taken for about a week. ^Another remedy is to boil six grams

of Baberang (Emoelia Ribes), three grams of dyry

Ginger and

20 grams of Jaggery in 500 ml. of water till half of it is

left.

The decoction should be taken for some days before

it shows its effect

*/ A decoction of 20 grams each of flowers and leaves of the

Cotton Plant (500 ml. of water boiled to half its quantity)

mixed with 20 grams of Gur is also effective in inducing the

menstrual flow,

* Another remedy is to steep 10 grams of Black Sesame seeds

and an equal quantity of small Caltrops (Gokhru) in 250 ml.

of water and to ’grind them in the same water.

It should be

sweetened with sugar, and drunk.

* Treatment with -the seeds of Tulsi ground and suspended in

water for three days beginning from the first day of the

menstrual flow will help the woman to conceive, as this treat

ment is purifies the uterus.

If this treatment is given to

any infertile woman for a year, she is sure to conceive.

* One gramme of each of the following ingredients is taken:

Tulsi s’eeds, naagkesar, ashwagandha, and palash peepal.

These are then ground to a powder that is fine enough to pass

t through cloth.

To this powder are added 10 grams of cow's

milk^ and some sugar.

Administration of this preparation will

restore regularity of menstruation within two months, even

in the case of a woman who has stopped menstruating for some

reason.

e,

125 grams of each of the following ingr^die^nts are seasame

seeds, tender shoots of the cotton plant and tender shoots

of bamboo plants.

220 grams of aged jaggery are mixed with

the powder and pea-sized pills are prepared.

These pills

taken one at a time with warm water every morning and

evening will also restore regularity of periods, even in

cases of women with amenorrhoea.

* Myrrh by itself is often good for amenorrhoea, particularly

„

taken as a tincture.

An anti-Vata or toriiifiying diet is

paKtxEMiaKkyxkxkexxasxaxk±H<skuxHX primarily indicated using

dairy, meat, nuts, oils, whole grains arid other nourishing

foods.

Iron supplements.or Ayurvedic iron ash preparations

Warm seasame oil can bp, applied to the ower

are important.

abdomen or used as a. douche.

A mild laxative can be taken

such as Triphala, aloe gel or castor oil in lower dosages.

* For. amenorrhoea due to cold, many spicy herbs can be usedginger, turmeric, black pepper, cinnamon, rosemary, or the

formula Trikatu.

Fresh ginger and pennyroyal in equal parts,

ounce per pint of water, 1 cup three times a day, is good

Western herbal treatment for this condition, whisk

* Ayurvedic herbs for Vata type delayed menstruation include

asafoetida, cyperus, myrrh, ashwagandha, shatavari, kapika-

,

cchu, black and white musali.

*

A good simple formula is shatavari and ashwagandha two parts

tz each, and turmeric and ginger one part each, using one

teaspoonful of the powder per cup of warm water.

.

* Kapha (water) type delayed menstruation is die to congestion

x/\and- sluggishness in the system.

It can also be treated by

strong warming spices-ginger, cinnamon, cayenne, black pepper

or Trikatu or Clove combination formulas.

* P_itta_-(-fire) type delayed menstruation is usually mild and

can be treated by turmeric or saffron in warm milk.

Other

good herbs are rose, cyperus, dandelion and other cooling emeenagogues.

c

* Drinking of 1 tola of the juice of the tender leav^fe of neem

is effective.

A decoction of the bark is also useful.

* Pumpkin^: Kadu hire, nagadali bali in Kannada; adavibira in

Telugu- their seeds correct the absence of menstrual flow.

* Apium Petroselinum or Parsley: Apiol a green liquid distilled

from the root is much recommended in absent or disturbed X

menstrual flow:

is given then in doses of 2-3 minims given

in sugar or in capsules.

In cases of arrested menstruation

accompanied with fever and malaria, pills made of 2 grains

of quinine suislphate, l/3rd grain of apiol,

a grain perma

nganate of potash are given beneficially.

* Onion: Eating the bulbs raw has been noticed to bring about

a desirable regularity in menstruation among the ladies.

If

it is a case where^ menstruation does not occur or is- obstru

cted five tolas of onion are cooked in one ser of water till

the latter.is reduced to about ten to twenty tolas.

3 tolas of jaggery.

Then add

This is to be made hot and drunk by the

patient for a few days.

Other recipes are: three tolas of

onion juice are made luke warm and drunk before going to

bed at night: Or, ten tolas of onion afe cut into small ,

pieces, garam masala is added o to it and thewhole is roated

in ghee and eaten.

rectified.

The obstructed menstruation, will become

I MENSTRUATION:

4.

Leucorrhoea - White discharge

A regular douching of the genital tract with a decoction of

the bark of the Banyan tree, or the potassium permaganate is

indicated..

Douching pwith decoction of bark of the Banyan of Cig tree

keeps the tissues of the vaginal tract healthy

* The dried and powdered bark of the Muisari (Mimusops Elengi)

tree mixed with an equal weight of raw Sugar should be taken

in nien grams doses every morning with water.

Alternatively,

equal weights of the leaf-sghoots of Bastard Teak (Dhak)

and Banyan tree should be tried and powdered. An equal quant

ity of raw sugar should be mixed with them and nine gram

doses should be taken with 250 ml. of milk thrice daily.

Theroot of the Silk Cotten tree (Sembhal) is another specific

for this condition. Seven grams of its powder with an equal

weight of raw Sugar should be taken with a glass of milk.

* Dry Amla and Liquorice in equal quantities and powdered and

mixed with thrice the quantity of honey make an effective

drug against the disease.

Six grams of the linctus should

be taken in the morning and evening with milk.

* The patient should chew betel nut after meals as it has

curative effect.

* Cumin seeds ground in Tulsi juice and mixed with fresh milk

/of a cow have a beneficial effect in leucorrhoea, and they

also improve the general health of the wonjan.

* 20 grammes of Tulsi juice with rice water, meanwhile restri-

^/cting the diet to rice and milk, or rice and ghee for the

duration of the treatment.

* One teaspoonful of the powder of the banyari tree and fig tree

should be boiled in one litre of water and reduced to half.

The decoction is then filtered and the powder thrown away.

When it is slightly warm, douching should be performed.

This

decoction keeps the tissue cells of this area healthy.

-The-"

* popular medicine used by Ayurvedic physicians in this condi

tion is 'pradarantaka lauha'.

of iron.

This drug contains some bhasmas

For the peeparation of this medicine, the ingre

dients are triturated with the juice of 'kumari'.

Four

grains of this drug is given to the patient three times a

day, with honey,

* When the outer skin of the leaf of this kumari is removed,

a fleshy pulp comes out which is used for the extraction of

juice.

One ounce of this is to be given to the patient

twice daily with a littlye honey added to it, preferably on

an empty stomach.

This juice stimulates the liver, promotes

digestion and regulates the bowels.

* Lodhra is also used for the purpose of douching.

The bark of

this tree is used and the decoction of the bark is prepared

on the lines suggested above.

The medicine is also used

in the form of lodhra asava.

* Tankana or alum is also used both externally and internally

for the treatment of this condition.

Alum is fried in a

vessel over fire and then powdered.

One teaspoonful of the

powder is added to the decoctions described above and used

for the purpose of douching.

* Two grains of this powder are mixed with two grains 01L p

pradarantaka lauha and given to the patient twice daily on

an empty xebkh! stomach mixed with honey.

* Alongwith all the medicines described above tanduledaka

(rice-wash)

is given as a means to accelerate their action.

Rice-wash alone is also useful for the cure of this disease.

* Take the leaves of Drum stick tree in any form as soup or

sagH or chatni.

Take the juice of arhar (Cajanns Indfcus) leaves.

cup with sandha namak (rock salt)

1/day x 30 days

Dose:

1

-2-

* Take thS inner part of the leaves of Gritha Kumari with

1/day in the morning in empty stomach x 5 days.

jaggery.

* Grind the tuber of 4' o'clock plant (Gulavas; Mirabilis jalpa)

in empty stomach.

Mehandi seeds-1 kg. Triphala-250 grams each, grind all these

together; add little bit of the powder of jira, ajwain, and

somph.

Make pills mixing with the syrup

of jaggery. Dose:

1 each 3/day x 30 days.

* Grind and give a handful of Brahmi (Centella asiatica) 1/day

x 30 days.

* Dry and powder separately raw Banana, rice (ara rice, and

4-. Triphala) .

jaggery.

Mix all in equal amount end prepare lehyam in

Dose: 1-2 teaspoonful 2/day x 30 days.

* Grind the leaves of Kena grass anddrink with a glass of

cow's milk.

g

1/day x 3-7 days.

* ^oil few cut pieces of ginger and few flowers (Better buds)

L of arhul (hibiscus Rosa) in a glass of cow milk adding equal

amount of water and reduce it to half.

with sugar.

Strain and drink

2/day; morning and at bed time x 21 days.

* Fluid extraction of the bark or an infusion of the bark of

V mango tree is curative in h leucorrhoea.

* Prepare a tincture or an alcoholic extract of the powder of

betel nut and employ it but freely diluted with wat^r- 1

drachm of the tincture in 4 ounces of water.

This is used

locally or as an injection to stop water discharge from the

vagina and also in checking the hydrosis of water rash of

^pregnancy.

Hdre, a sudden flow of acid fluids from the

stomjph to mouth occurs and an outbreak of burning sensation

(heart burn) in the gullet, as well.

I MENSTRUATION;

5.

Other Problems:

* Drinking of 1 tola of the juice of the tender leavjss neem is

advised even in the aDsence of menstrual flow or the obstru-

ction of such a flew because this is a good corrector of

menstrual irregularities.

This is also used in cleaning

the Uterus.

* The juice of the flowers "is given regularly upto six'mashas

in dosaae to be licked along with hone^. -(-neEOTh

* Bitter gourd; hagala kayi in Kannada; kakara, tellakakra

in Telugu is given internally to cure disorders of menstr

uation (freshly extracted juice).

* rhe seeds of raddish are regarded to be possessing emenago-

guic properties viz. they regulate menstrual cycle among

women and are therefore used in the related disturbances.

The external application of the seeds promotes menstruation.

A teaspoonful of the seeds of raddish is to be ground into a

smooth paste.

then drunk.

This is to be mixed well with buttermilk and

This will commence menses that had become

obstructs.

* If the flow is too little or is accompanied with pain, heat

water, mix mustard powder with it andplace the patient in

such a water upto the waist.

Such a hip w bath for an hour

would render the flow to become normal and pain free.

* Betel nut is regarded as a nervine tonic and an emenagogue

or that which brings about regulation in menstruation and

its cycle.

Gingel ly decoction is given to girls to bring about quick

A pinch of saffron well crushed in a tablespoonful

px)

puberty.

J

of milk is another useful prescription for underdeveloped

girls.

effect,

In adolescence saffron has an overall stimulating

* It is a practice among certain communities in south India to

give the girl who has newly come of age a combination of a

teaspoonful of gingelly oil with a teaspoonful of overnight

soaked urad dal, a few grains of whole Bengal gram and the yolk

of one egg.

girl.

This 'egg nog.' helps in the full maturity of the

In addition, chutney made with coriander leaves, curfy

leaves, mint or fenugreek leaves all help in the full growth

of the adolscent girl.

come on.

Anaemia is checked, regular periods

Mint in particular is supposed to cure painful

periods xsm by acting as an uterine tonic.

* A tasty drink is

raade by mixing in milk egg yolk, four almonds

crushed, a little gingelly powder and a teaspponful of honey.

v This

could be given for sexually underdeveloped girls as well

as for those with undue delay in the onset of periods in

adolscence.

* Green unripe papaya is considered to be a more effective

J emenagogue which brings on the periods quickly.

the flow of periods.

It also increases

Pineapple has similar qualities too.

* Cumin and gingelly decoction sweetened with palm candy is

supposed to help the onset of menses and the free flow of blood.

i

* A modification of the above is to make sweet rolls with jaggery

black cumin and dry turmeric powder and take one or two a day

to help onset of periods.

* Boil pieces of the fig root(Anjeer, Dumeer, Athi pazyam) in

, water and make a decoction.

Filter and drink the decoction

/

for a few weeks to set the cycle normal.

* One gramme of each of the following ingredients is taken:

$ Tulsi seeds,^ naagkesar, ashwarfjandha, and palash peepal. These

are then ground to a powder that is fine enough to pass

through cloth.

To this powder are added 10 grammes of cow's

-2-

milk and some sugar.

Administration of this preparation will

restore regularity, of menstruation within 2 months, even in the

case of a woman who has stopped menstruating for some reason.

* Fry the kernel of the seeds of Neem in til oil and powder it.

Dose:

1 tspfull with sugar candy 2/day in empty stomach x 3-5

days.

* Prepare the decoction of the barks of Jamun tree.

Mango tree

, and shimal tree (Bombax Malabaricum)-silk cotton tree in 2 ltrs

of water reducing it to half. Dose:

1 cup 2/day x 1 day.

- S’-3

HERBAL MEDICINES

AMARANTUS Sr'INOUS( Kannada-'mullu dantu’, Telugu-1 ettamullu

1.

goranta, nalla doggali)

Used in checking excessive "mdnstrual

blood flow and its

( consumption by ladies Soon after childbirth

milk content.

gonorrhoea.

The root

increases their

is regarded as specially medicinal

in women)

laxatibe and galactagogue

(promoting milk production

Its decotion i’s beneficial

in curing urinary retention and

gonorrhoea.

in

In Madagascar a the root is considered diuretic,

The root ground in water is apolied over chancres

(the hard swellings that constitute the primary lesions in

syphilis) that are also infected with fungi,

in addition.

(LEAFY VEGETABLES-Traditional Family

Medicine)

NEEM

1 .

(TFM)

IN LABOUR PAIN:

In Maharashtra, neem is called balantnimb viz the after labour

neem,

the use of neem here is so m^uch reputed.

If the midwife

administers fresh m juice of leaves even before the labour,

contraction of the uterus is facilitated.

The flow will

the

be

clear, the swellings of the uterus and the surroundings get

lessened and the patier^starts getting hunger.Faecal matter

becomes clear, there will not be any fever and even if fever

arises its violence is much less.

Drinking water in which neem bark has been boildd whenever she

feels thirsty after the labour is over,

/

will keep the patient

healthy.

Washing the uterus with warm neem water will relieve the uterine

pains due to delivery and ia also the morbid swellings if

apy.

The wounds will heal and dry up and the orifice becomes

clean and contracted.

V

Fermentation with the inner bark of old

neem trees is highly recommended for all diseases following

delivery.

The fresh juice of neem leaf

after the birth of the child.

meals.

is given for the first three days

This is given before the principl

Such a measure improves the general health of the mother

and also increases the. milk yield.

This is also given to the

cows so as to increase the yield of milk.

s

2.

LEAF PREPARATIONS:

Hysteria in Ladies- Taking fresh leaf juice or leaf decoction

for three to four months will relieve such a hysteria which is

due to the abnormalities of uterus.

If there is ixcess menstrual flow, a drinking of 1

the juice of the tender leaves is resorted to.

tola of

This is advised

even in the absence of menstrual flow or the obstruction of such

a flow because this is a good corrector of menstrual irregulari

ties.

3.

This is also used in cleaning the uterus.

BARK PREPARATIONS:

Amenorrhoea(Absence of Menstrual Flow)- A decoction of the bark

is given as a drink for sarrsstiapixxiR the same.

4.

FLOUER PREPARATIONS:

After Labour Pain- Flowers are ground and applied over the head

or the stomach to relieve the pains at the head or the stomach

following delivery.

Menstrual Irregularities- The juice of flowers is given regu-

V]

larly upto six mashas in dosage to be licked along with hone£.

I

GOURDS AMD PUMPKINS

Sore kayi, halu kumbala

gubba kaya

(TFM)

(the milky pumpkin)

(a bloated vegetable),

The io sweet fruit variety

in Kannada; alaburu,z

sorakaya in Telugu.-

is wh olesome to the developing foetus

and therefore well advised for the pregnant women, as a very

salutary diet.

Kadu hire, nagadali balli in Kannada;

adavibira in Telugu- their

seeds correct the absence of menstrual flow in amenorrhoea.

Bittef Gourd;

hagala kayi in Kannada; kakara,

in Telu’’

tellakakra

is given internally to cure disorders of menstruation.(freashly

extracted juice).

Kadavanchi in Marathi and Kannada are tubers used to procure

abortion.

Bitter Apple; pavamekke kayi,

klaaRmMfctixc chittipapara,

tumati kayi

in Kannada; pey

etipuccha. in Telugu is useful

in

rectifying abnormal presemtation of foetus and also in atrophy

(or non-development and growth.) of foetus.

-2-

vegetables(tfm)

CARROTS: Ths seeds of carrot are emenagoguic

(regulating men

strual cycle), cleaning to uterus and abort ifacient

(i.e. causes

abortion of the f.oetus).

RADDISH:

The seeds of b

raddish are regarded to be possessing

emenagoguic properties viz. they regulate menstrual

cycle among

women and are therefore used in the related disturbances.

The

external application of the seeds is promotes menstruation.

A teaspoonful of the seeds of radish is to be ground into a

smooth paste.

then drunk.

HIBISCUS ;

This is to be mixed well with buttermilk and

This will commence menses that had become obstructs

dasaval

in Kannada-are fried in ghee and given in

menorrhagia or excessive menstrual flow.

FRUITS (TFM)

MANGO: Tind of unripe fruit

is cut into pieces, fried in ghee,

mixed withs sugar and the whole stuff

is made into a pill mass.

Several pills are made out later and these are given in sti

pulated doses in case of menorrhagia or excessive menstrual

flow.

The kernel of the seed is powdered and given in doses of

20 to 30 grains with or without honey i-n—many-af-f-l-ict-i-on's-:—i~i‘ke

excess-menstrual flow.

kernel

For dysentry in pregnant women the

is fried in ghee and given for e ting.

Fluid extraction

of the bark or an infusion of the bark is curative in excessive

menstrual flow, white discharge.

BANANA:

Pregnant ladies will find nashBdxwB consuming ripe

,

banana fruits regularly would nourish their food well and will

als@ pave way to a safe delivery.

A drink of the juice of

plantain flowers mixed with curds acts as a curative to young

girls suffering from excessive haemorrhage during and after

menses.

The relief obtained is quite quick.

PAPAYA: The major use has been in correcting menstrual disorders

or as an emenagogue.

There is a popular quite strong particu

larly in Tamil Nadu that they may cause abortion.

In central

and South America, the seeds are used as anthelmintic and

emmenagogue to normalise mensus troubles.

Juice of the green

fruit is applied in—r-ingworm and as a sure remedy for scorpion

locally as a pessary to uterus to induce abortion.

However,

it is better that pregnant ladies aboid eating paoaHa,

□r ripened,

till the thi^d month.

abortion then.

A fruit salad

raw

For, there would Be a risk o

of honey, milk and paoaya

fruit is an excellant tonic-ideal for children,

feeding mothers

and pregnant ladies(after their third month).

SPICES(TEM)

-PEPPER-:

In Kerala an infusion of the root

is prescribed after/

childbirth to cause an expulsion of the placenta, almost as a

regulars household remedy.

PIPER BETLE-Betel leaf vine in English;

pan,

tatobuli in Kannada

Used for child bearing in' Orissa.

The slender roots with black

pepper are used to cause sterility

in womdn.

PEPPER; /nennasu in Kannada- facilitiates menstruation.

CLOVE: lavanga in Kannatja;

lavangamu, karavappu in Telugu.-

Take a masha of .tie powder of cloves, mix

sugar candy or pomegranate juice.

it with a syrup of

This is to be taken by the

pregnant by licking, teo get rid of the repeated vomitings andthe agitation thereof.

An infusion of cloves also serves the

same purpose but this should not be given if there is an

accompaniment of fever along with vomiting.

CINNAMONUM TAMALA:

dalchini, lavangada pattai,

kadu dalcljini in Kannada;

It

lavanga patri,

talisha patri in Telugu.

is promotive of menstruation and a lactagogue-promoting

milk secretion.

CINNAMOMUM MACROCARPUM:

bhringa, dalchini, lavanga pattre in

Kannada has a reputatijawxaR ed application

in menorrhagia

and also in difficult labours that are due to defective uterine

contractions.

The distress of the labour pain.after child

birth will get

greatly relieved by a drink of the cinnamon

decotion.

<By'consuming a pinch of cinnamon powder daily at

night for a'"month altogether would postpone the reappearance

of menstrual flow as much as possibleTJ^.

CARDAMOMS:

elakki

in Kannada a can cause mm abortion.

Chewing these grains well and gulping in, will ward off stomach

upsets, dizziness of the head and oozing of water in the mouth

as well as the tendency to vomitting.

Another measure to over

come dizziness and avoid vomitting tendency is

to take the

cardomom powder in a glassful of lemon juice.

Drop three to

-3-

four pinches of cardomom powder into a cupful of tender cocoanut

juice, add two spoonfuls of honey to it and take in.

stop vomitting.

In case however,

This will

vomitting is too violent,

adopt this measure thrice a day for two to three days.

SEASONING HERBS(TFM)

MUSTARD:

sasive

in Kannada; avalu in Telugu-

To expel dead foetus:

rattis of fried

3 mashas of mustard and 4

hing are mixed with soury conjee or wine and given as a drink.

Menstrual flow:

If the flow is too little or is accompanied

i

with pain, heat water, mix mustard powder with it and place

the patient

in such a water upto the waist.

Such a hip bath

for an hour would render the flow to become normal and pain

free.

CUMINUM:

women,

jeerige in Kannada; jeeraka

in Telugu- For pregnant

/

seeds are ground and mixed with lime juice and given

in cases of bilious nausea.

Intake of cumin seeds soon after

child birth will increase milk secreation.

■CORIANDER: kottambari,

haveeza

in Kannada; kotimiri

Take a teaspoonful of coriander seeds, powder,

in Telugu-

grindtit smoothly

in water, mix this paste homogeneously in water in which rice

has been washed, add sugar and administer.

This measure can

be continued twice a day till, the vomitting tendency comes

under full control.

APIUM PETROSELINUM OR PARSLEY:Apiol

from the root)

menstrual flow;

(a green liquid distilled

is much recommended in absent or disturbed

it

is given then in doses of 2-3 minims given

in sugar or in capsules.

In cases of arrested menstruation

accompanied with fever and malaria,

pills made of 2 grains of

qui-nine sulphate, l/3rd grain of apiol,

ganate of potash are given beneficially.

1/2 a grain perman

When the leaves are

applied several times a day to the breasts,

it will arrest milk

secfeat ion.

ASAFOETIDA

OF HING: hingu or ingu in Kannada;

inguva in Telugu-

' Hing at the child birth stimulates uterine wall,

render it clean

and stops the terrible disease of makkalla characteristic of

child birth in many women.

To prevent abort ion:Habitual abortion is treated in the foil

manner.

Six grammes of hing are made into 60 pills

■yi^ain). Directly the pregnancy

is given twice a day.

(each,

of

is suspected one such pill

The dose is-then slowly gx increased to

ten pills a day and then ^gradually reduced till confinement.

Such a procedure has proved sutcessful in cases having three’

to five abortions,

or complications of premetritis

ammation of the outer layers of the uterus)

(the infl

or catarrhal

endometritis(discharge from the inner walls of the uterus)

and also in cases in which abortion at sixth month was threatnin<

* Taking a teaspoonful of the decoction of clo'tae to which a

j

little bit of hing is added and doing so thrice a day

'

is bene-

ficial to feeding mothers for this will ensure greater milk

production.

* Keeping a bit of hing enclosed within a piece of cotton

in the ears will ensure freedom from catching cold after child

birth.

DILL-EUROPEAN AND INDIANzsabbasige in Kannada;

sompa in Telugu-

The herb is particularly invaluable for women after child birth.

Consuming its preparations regularly will promote rich secretion

of milk and more imoortantly it also acts a good family planning

measure.

For,

by this procedure, the interval between child

birth and the next menses period gets greatly prolonged so

that both the mother and the child can secure ample time for

halthy and proper nourkshment.

* However as this stimulates abortion,

it is better that the

pregnant ladies should totally avoid eating it during the

first three months.

* Sowa or the Indian Dillis useful otherwise too.

Take fresh

fruits of sowa, powder and keep in a fresh and greased vessej-

One should get up in the early morning at Srahmi muhurta

(3.30)

and lick up 1,2 or 4 tolas of the powder along with ghee.

Or,

one can determine the quantity as per one’s own digestive a

ability and take that amount every day.

After this is fully

digested one should take a meal of milk and rice as much as

desired.

A person who thus consumes 400 tolas fof shatapushpa

can get a progeny of whatever quality he desires.

barren woman can become fertile by this procedure.

■^feftP-Q-NUT-

Even a

COCONUT, BETEL NUT etc

(TFf*l)

COCONUT: Abortion- Take fresh flowers, the fruit of gular

(Ficus Glomerata) and nagar motha-all in equal parts.

Prepare

a decoction which can be given to reduce the chances of abortion

* If pregnant ladies find that there is an excruciating pain

during urination, they are best advised to consume as much of/

tender coconut water and barley water as they desire.

always proves greatly relieving.

This

Another simple recipe to

get rid of the burning sensations during the passing of urine

is to consume tender coconut water twice a day adding to it

a little bit of jaggery and half a teaspoonful of coriander /

powder.

* Coconut oil is an ideal medium for massaging.

month of pregnancy,

it

In the 7th

is quite frequent to suffer from back

Massaging the back with coconut oil or castor oil and

pain.

then taking bath in^hot water will lessen this pain much.

* The coconut coir has been used medicinally.

of this coir into asheswell

Burn some amt

Take a teaspoonful of the ash,

mix it

in tender coconut water, add a small quantity of sugar

candy and administer this drug twice a day for young girls

who suffer from excessive discharge during menstruation.

BETEL NUT: Prepare a tincture or an alcoholic extract of the

oowder and employ it but freely diluted with water- 1

of the tincture in 4 ounces of water.

drachm

This is used locally

or as an- injection to stoo water discharge from the vagina

and also in checking the hydrosis or water rash of pregnancy.

Here, a sudden flow of acid fluids from the stomach to mouth

oECurs and an outbreak of burning sensation (heart burn)

in

the gullet, as well.

* The nut is regarded as a nervine tonic and an emmenagogue II

or that

which brings about regulation in menstruation and

its cycle.

II

’

* The young green shoots are utilised to bring about abortion

in early pregnancy.

KIKAR OR GUM ARABIC,ACAC IA ARABICA:jali, karijali, bauni

ini}'

Kannada- Gum of Babul-This is usually given to ladies after ,

child birth.

Its water removes the pains at' the stomach and__

the intestines.

In excessive menstruation 4-1/2 mashas each

aTrd~-m-a-r-k-i-n-g—n-ut-(~ge-jru--j------

v

of the gum and marking nut

(geru) are given,

grinding them

and along with water.

KATHA,CATHA,KHAIR OR ACACIA CATECHU:

Decotion of the heart

wood of khair is excellent to prevent excessive haemorrhage

For leucorrhoea due to uterine debility,

at child birth.

bleeding and uterine laxedness, pills of kattha and myrrh

in equal ia proportion are useful.

A mixture of these two

drugs is given for strenghthening after child bieth and to

incr§ase milk

secretion.

An aqueous injection of kattha is

given for lircorrhoea and the blood flow at the uterus and

also in gonoorhoea.

A tincture of kattha is an excellant

application for suspected bed sores and also cracked nipples.

GINGER AND TURMERIC (TFM)

31

If \Q

GINGER: To cure vaginismus or spasmodic contractions of the

vagina,

powdered dry ginger is well mixed with castor oil or

castor root powder or paste and then applied to the painful partU

concerned.

TURMERIC:

During labour and as long as the child is young and

breast feeding,

it is advised for the ladies that they should

be regularly taking turmeric-for ex

in milk.

This is an ex

cellent practice as this l$ill stimulate the uterus and will

also porify milk secretion.

CURCUMA ZEDOARIA ROSE: kachora in Kannada; kicchili gadda

in Telugu- The root is an ingredient in some of the strength-

y

ening conserves taken by women so as to remove weakness

,after childbirth.

It is given 3 times a day to women during

the first two weeks following child birth.

ONION AND GARLIC(TFM)

ONION: Eating the bulbs raw has been noticed to bring about

a desirable regularity in menstruation among the ladies.

If

it is a case .where menstruation does not occur or is obstructed

(amenorrhoea or ruddhartava), five tolas of onion are cooked in

one set of water till the latter is reduced to about ten to

twenty tolas.

Then add 3 tolas of jaggery.

This is to be made

-5hot and drunk by the patient fora feu days.

Other recipes

are: three tolas of onion juice are made lake warm and drunk

before going to bed at night:

small pieces,

Or, ten tolas of onion are cut int

garam masala is added to it and the uhole is

roasted in ghee and eaten.

The obstructed menstruation will

become rectified

GARLIC:

Useful in difficult menstruation..

In cases where

much pain is felt at the loins during menstruation,

garlic

juice is given internally and crushed garlics are applied

externally as a massaging material.

* In shooting pains at the loins: Proprietary garlic preparation

called rasona paka helpful.

Garlic and salt are to be ground

together, made into a poultice and bound over the regions

of injury,

sprain,

spasms,

twisting pains and the like.

Mt NS T£ (Ja T)OM.

).

cp

y ■

t

” <3

^fy&T- t'JA TA) L Ca £6

ptoccwto_

-iutfe 1 (0

—/^LCjZgLl'^O

--- .SCCL'U'uty

—^7

C

XjXCt

-7’

cCtAct^uA^Q •

g•

&GrOyC0)'CAL

•

I.

3 .

■

>

1. -Cjek,

<2- <c^C\£x.C wzcc

2>- 'TtU.

4 Pb.vu

,

’-C&jl

^JLIoqz'cclC

9

b~^cLi, ,

i

—S>

.

■

' S7■ Lf85

'the LANCET, JANUARY 14, 1989

Community Health

diseases in rural women; (2) awareness and perceptions of

the women about their gynaecological and sexual disorders;

and (3) die proportion of women who have access to

gynaecological care.

HIGH PREVALENCE OF GYNAECOLOGICAL

DISEASES IN RURAL INDIAN WOMEN

R. A. Bang

M. Baitule

S. Sarmukaddam

A. T. Bang

Y. Choudhary

O. Tale

SEARCH, Gadchiroli-442 605, India

A population-based cross-sectional study

of gynaecological and sexual diseases in

rural women was done in two Indian villages. Of650 women

who were studied, 55% had gynaecological complaints and

45% were symptom-free. 92% of all women were found to

have one or more gynaecological or sexual diseases, and the

average number of these diseases per woman was 3-6.

Infections of the genital tract contributed half of this

morbidity. Only 8% of die women had undergone

gynaecological examination and treatment in die past.

There was an association between presence of

gynaecological diseases and use of female methods of

contraception, but this could explain only a small fraction of

the morbidity. In the rural areas of developing countries,

gynaecological and sexual care should be part of primary

health care.

Summary

INTRODUCTION

Maternal and child health care is one of the eiglit basic

components of primary health care in the Declaration of

Alma-Ata? In some programmes, a more focused approach

has been advocated and promoted—termed selective

primary health care2 or child survival revolution.3 There is

new concern about the health care of women during

pregnancy and childbirth,4 and prevention of maternal

mortality has been identified as a priority.5 By contrast, little

attention has been given to the reproductive health of

non-pregnant women. In third-world countries, such

women tend to encounter the health care system only when

they are the target of family planning programmes.6

The term gynaecological diseases is used in this paper to

denote structural or functional disorders of the female

genital tract other than abnormal pregnancy, delivery, or

puerperium. One reason for the relative neglect of

gynaecological care is a failure to appreciate the extent of

unmet needs in rural areas. Most of the data are from

hospitals or clinics and are highly selective; they give no idea

of the rates in the population.7,8 The few population-based

studies have focused only on specific disorders—ie, cervical

cancer9*16 (chosen for study because of hospital experience),

vaginal discharges,17 and genital infections18 (based on

family planning clinic data). We are unaware of any

population-based study of the whole range of gynaecological

diseases in developing countries. An additional reason for

lack of information on these disorders is the extreme scarcity

of female doctors in the rural areas of developing countries.

Traditionally women from these areas are very reluctant to

talk to or be examined by male doctors for gynaecological or

sexual disorders. Nurses and paramedical workers are not

trained to deal with gynaecological diseases; so the result is

near total absence of care.

In the present study we sought to determine: (1) the

prevalence, types, and distribution of gynaecological

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Area and Sample Population

Gynaecological inquiry and examination is a very sensitive matter

for rural women in India. One cannot randomly select a few women

from a large population and descend upon them. Hence it was

decided to make villages the units of study.

The investigation was conducted in Gadchiroli district, a

backward district of Maharashtra state. Two villages were selected

on the following criteria: socioeconomic composition similar to that

of the average village; leaders who could understand the nature of

study and would persuade the women to participate; prevalence of

gynaecological diseases not known to be atypical.

Village A had a population of 1400 and village B 2200. They were

located 20 km from the district town and from each other. Both had

perennial roads. A primary health centre with two male doctors was

located in village B while a small mission hospital run by the nurses

was located in village A. 'Phus both the villages had good access to

primary health care, though the nearest gynaecologist was at the

district town.

Female social workers, village leaders, and volunteers invited all

females who were age 13 years and above or had reached menarche

to participate in die study, whedier or not they had symptoms.

Investigations

A field camp was set up in the village, first in A then in B, with

facilities for interview in privacy and pelvic examination, pathology

laboratory, and operating theatre. A base pathology and

bacteriology laboratory was established at the project headquarters

20 km away. The study team (a female gynaecologist with 10 years’

experience as consultant, a physician, a pathologist, a laboratory

technician, a nurse, and female social workers) visited the field camp

and conducted the study. The women who were found to have

disease were offered treatment.

First, information was obtained on personal details,

socioeconomic status, perceptions and practices as regards

gynaecological symptoms, past experience of care, and obstetrical,

gynaecological, and sexual history. The women then had a general

physical examination including speculum examination and

bimanual examination of the pelvis; unmarried girls with an intact

hymen had rectal rather than vaginal examination. The following

laboratory investigations were done (apart from vaginal specimens,

omitted in the never married): urine and stool tests; haemoglobin

(cyanmethaemoglobin method); peripheral smear for typing of

anaemia and for parasites; VDRL test (slide flocculation test using

antigen from Government serology laboratories with positive and

negative controls for quality control); sickling test with 2% sodium

metabisulphite; urine culture and antibiotic sensitivities when

necessary; vaginal smear microscopy and gram staining; vaginal and

cervical cytology with Papanicolaou stain (method of Hughes and

Dodds19); culture and antimicrobial sensitivity of vaginal swab

(after transport to base laboratory in nutrient broth, primary

inoculation was done on McConkey and blood agar and growth was

observed 24 h later; motility and gram staining were studied, with

biochemical reactions; specimens were not incubated in carbon

dioxide atmosphere for Neisseria gonorrhoeac, or for anaerobes);

blood biochemistry, when necessary; husband’s semen analysis,

when indicated;20 and cervical biopsy, dilatation and curettage, and

radiological examination when indicated (all histopathology slides

of biopsy or uterine curettage material and suspicious cytology

slides were reviewed by senior pathologists at the nearest referral

laboratories at Nagpur).

Diagnostic terms and entities were those in the International

Classification of Diseases, 9th revision.21 Vaginitis was diagnosed

when the vaginal wall was visibly inflamed and the vaginal smear

showed at least 5 pus cells per high-power field. When smear

THE LANCET, JANUARY 14, 1<

86

TABLE I—COMMON GYNAECOLOGICAL AND SEXUAL COMPLAINTS

(n = 650)

Complaint

Frequency

(%)

88

60

36

82

45

32

132

98

43

63

135

92

Vaginal discharge

Burning on micturition

Childlessness

Scantv periods

Irregular periods

Profuse periods

Amenorrhoca

Dysmcnorrhoea

Dyspareunia

Other

12-6

6‘ 9

•/■9

203

66

9-7

microscopy, gram staining, or culture revealed no pathogenic

organisms, it was labelled vaginitis of unknown origin. Syphilis was

diagnosed when the VDRL test was positive in 1:8 dilution or

more.- Pelvic inflammatory disease was diagnosed when adnexac

were palpable and tender on vaginal examination, with or without

restricted mobility of uterus. Jcffcoate’s criteria2-' were used for

various other gynaecological conditions.

Anaemia in females was defined as a haemoglobin of 11 -5 g'dl or

less.34 Iron deficiency was diagnosed on the basis of hypochromia

and microcytosis in peripheral smear. Vitamin A deficiency was

diagnosed by identification of conjunctival xerosis or Bitot’s spots.

Sickle cell disease was diagnosed by the sickling test, but

homozygous disease and trait, could not be distinguished, in the

absence of electrophoresis.

Because of the sensitive nature of the survey and the cultural

norms of these traditional societies, we aimed conservatively at 50%

coverage of the eligible women. In the event, 654 out of 110-1(59%)

turned up to participate and the investigations were completed in all

but 4. Although every effort was made to persuade both

symptomatic and symptomless women to participate, selection

might have arisen. We therefore visited a 25% random sample of

non-partidpanr. women at home to record their personal,

obstetrical, and contraceptive histories, presence or absence of

gynaecological symptoms (vaginal discharge and menstrual

disorders), and reasons for non-participation.

The data were analysed by use of the SPSS-PC package on a

RESULTS

The mean age of the 650 women was 32-11 years (SD

13-46). 92 (14%) were unmarried, 462 (71%) were married

and living with husbands, 28 (4%) were separated, and 68

(11%) were widows. Thus 558 women were married at the

time of study or had been in the past. 281 (44%) were

farmers, 149 (23%) were landless labourers, 93 (14%) were

housekeepers, 21 (3%) had regular jobs, 46 (7%) were

students, and 55 (9%) were in other occupations. 436 (68%)

were illiterate; 84 (13%) had schooling up to 4th standard,

52 (8%) up to 7th standard, and 65 (10%) up to 10th

standard, and 8 (1 %) had college education.

299 (46-0%) belonged to middle castes and 123 (18-9%)

to lower castes; 138 (21-3%) were of tribal origin and 28

(4-3%) from nomadic tribes; and 62 (9-5%) were of other

castes or non-Hindu.

28 (4%) of the subjects had not reached menarche, 468

(72%) were menstruating, and 154 (24%) had reached

menopause. The mean gravidity was 3-99 (SD 2-77) and