ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Item

- Title

- ADOLESCENT HEALTH

- extracted text

-

%

RF_WH_.11.5_SUDHA

Sexual and reproductive health of

young people, India

Shireen Jejeebhoy

Population Council, New Delhi

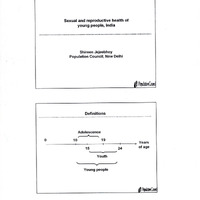

Definitions

Adolescence

0

19

10

—4-

-H-

-4-

15

—H

24

Years

of age

Youth

Young people

1

9

Adolescence and youth

Adolescence

has

both

biological

(physical

psychological) and socio-cultural dimensions

&

■

“Adolescence” is a phase rather than a fixed age group

and can be perceived differently in different cultures

■

Gender differentials are important

■

Stages in adolescence (10-13,14-16,17-19 years)

Why focus on young people?

4^

Adolescent risk behaviours and implications for

adult health

Behaviours formed in adolescence have lasting implications

for individual and public health.

Most adults who smoke started during their adolescence

Young people who start drinking before age 15 are four

times more likely to become alcoholics than those who

start at age 21 or later

HIV+ women more likely than others to report forced sex

in adolescence

Why focus on young people?

■ >300 million population aged 10-24: India’s health, mortality,

morbidity scenarios depend heavily on the experiences of

this population

■ Current thinking not informed by the unique needs and

vulnerabilities of young people - and continues to

Serve married adolescents in the same way as married

adults

r- Exclude unmarried adolescents from the network of

contraceptive supplies

> Focus on nutritional supplementation and other noncontroversial services

3

Why focus on young people?

• With new thrust towards youth programming (e.g. RCH-2),

need to have benchmarks, enable us to track the situation

of youth

• Above all, understanding young people's transitions to

adulthood, the life choices they face, the factors that

facilitate expansion of these choices or limit their

attainment will enable the design of more integrated and

realistic programming.

RyitoiCw

Context of young people’s lives

4

Young people not a homogeneous group: Youth transitions

■ Schooling: % attending school:

ages

80% of boys and 67% of girls

ages 15-17: 58% of boys and 40% of girls

■ Work: % 15-19 year olds working (1991):

Females:

26

Males:

44

■ Marriage: % 15-19 year olds ever married:

Females:

34

Males:

6

■ Family building: % women 15-19 with 1+ children:

All women:

16

Married women:

48

■ Mortality rates generally low; gender disparities apparent

What % are sexually experienced?

5

Unsafe, unwanted sexual relations

Majority of sexually active females are active

within marriage

Percentage ofyoung women married by age 13, 15, 18 years

Women currently aged:

20-24

25-29

Proportion ever married

78.8

94.5

Percentage married by age 13

8.9

12.1

Percentage married by age 15

23.5

29.2

Percentage married by age 18

50.0

58.9

Percentage married in adolescence

(by age 20)

67.1

74.9

Source: UPS and ORC Macro 2000

6

Sexual initiation within marriage

■ Large proportions of adolescent girls experience sexual

initiation within marriage

* Age at marriage remains low, and wide regional variation

■ Often the adolescent herself is excluded from the choice

of whom and when to marry

■ Married adolescents are a neglected population in terms

ofSRH

Premarital sexual activity observed among youth

30

26

26

20

20 15

55

15 10 -

5

0

6

4

3

Ki

Slum resettlement

colonv

College students

Low-income

A do 1 esc en t s y o un g

adults,

opportunist icallv

selected

Delhi

Chandigarh

Mum bai

1 6 cities

El Fem ale

Bi Male

Source: Abraham and Kumar 1999 for Mumbai; Kaur et al.. 1996 for Chandigarh;

Mehra, Savithri and Coutinho 2002 for Delhi; Watsa 1993 for the 16 city study

7

Sexual relations are not always safe

■ Multiple partners, casual and sex worker relations, relations with

“aunties"

10% rural males 15-19 reported a casual encounter in last 12

months (NACO and UNICEF, 2001)

r >20% in other studies

■ Non-use of condoms

Among unmarried males: large proportions report non-use, and

inconsistent use (>85%)

r- Among those reporting a casual contact, > 60% report

use (NACO and UNICEF 2001)

inconsistent

■ Non- use of contraception

r- Among the married, 8% report use and 27% report unmet need for

contraception (NFHS)

.

Sexual relations are not always wanted

Percentage of females and males aged 16-17 reporting nonconsensual sexual experiences, Goa

1

Forced sex f

7

6

j

Forced to touch [

abuser

[

Touched without

permission

10

6

'

.

:

'J— 13

-

- -- -

1

Brushed private

10

IP?

parts

0

5

10

□ Females

a Males

15

20

Source: Patel and Andrew (2001)

8

Non-consensual sexual relations are reported by

married females

“I decided to stop it since I used to feel uneasy while

having sex with a big abdomen. But my husband used to

get angry if I told him that I did not want to have sex. He

used to tell me that he would remarry if I refused to have

sex with him. I tried to explain to him, but he did not want

to listen. He used to get angry if I refused and we had

some tiffs on this issue. I had to give in to his demands

after a few days and our tiffs were resolved. We continued

in this manner till my ninth month. I had feelings of

discomfort but I had to accept my husband’s wishes”

(18 year old, recently delivered mother, Santhya et al., 2001).

Adverse consequences of unsafe or unwanted

sexual relations

9

Pregnancy related consequences

■

19% of TFR contributed by 15-19 year olds

■

Early pregnancy: >1 in 5 by age 17

■

Nearly 15% stunted and 20% anaemic

■

High rates of maternal morbidity and mortality

■

1-10% abortion seekers are adolescent

■

Neonatal mortality (63 vs 21) and low birth weight

Unintended Pregnancy

■ Large minorities of married

unintended pregnancy

and

unmarried

report

■ Often resolved by abortion

■ Young abortion seekers - particularly the unmarried - are

more likely than adults to delay abortion, opt for unsafe

providers and experience complications

io

Adolescent births are often unplanned

Ghana

Zimbabwe

Bolivia

Bangladesh

Egypt

60

80

RTIs, STIs and HIV

■

STIs observed: married young females aged 18-22 often

considered “low risk” : 18%

■

Significant percentages of youth with HIV/AIDS:

■ Females 14-24: 0.96%-0.46% (high & low prevalence

sites)

■ Males 14-24: 0.46%-0.20% (high & low prevalence

sites)

Sources: Joseph et al., 2003; UNICEF, UNAIDS, WHO, 2002

11

HIV/AIDS among youth, selected Asian countries: % of

youth living with HIV/AIDS

Females

Males

Adults

2il

I

% oJ

c ]

ir

.2

■u

c

a

Q.

Z

c

ca

o

a

c

a

2

22

0

Q.

5

o

8

c

- S

lo

a*

o

c

■O

5

'5i

«

rfTI

o

c

a

<3

Ecj

c

o

w

Z

£

F

Q.

ffl

Source: UNICEF, UNAIDS, WHO (2002)

Life expectancy at birth in 29 African countries

with and without AIDS

Without AIDS

E With AIDS

65 -i

60.4

2n

58.4

o 60 -1

>

o

c

56.4

54.1

55 4

0

o 50 o

a

x

©

45 -

51.7

50-249.2

52.6

-

■

47.5

47.4

■ ‘i £

’J .

V

’ -

40

1985-90

1990-95

1995-2000

2000-05

2005-10

2010-15

12

Underlying risk factors

and promising practices

CAN WE IDENTIFY THEM?

Postal Gxiim

Underlying risk factors

and promising practices

1. Lack of awareness

|| ftpitoiCcMia

13

Lack of awareness: % of adolescents aged 15-19 who have heard of

AIDS and who know about transmission routes

10°

_,

93.2

89.6

90

82.7

n

80

72.3

70 60

60

as

50

40

55.6

I

54.1

1

44.5

30.3

30

20

10

0

ill

21.8

18.7

15

9|1

al

f

20.2

13

81

MALE

FEMALE

URBAN, 15-19

MALE

FEMALE

RURAL, 15-19

□ Have heard of HIV/AIDS

□ Aware of at least 2 important methods of prevention

a Correctty aware of 3 common misconceptions on transmission

□ Aware of Unk of STI and HfV

Source: NACO and UNICEF 2002.

Superficial awareness and widespread misperceptions

■ % women aged <25 who have heard of AIDS: 37

■ % of these who reported:

57

multiple partner sex as a risk factor:

58

Consistent condom use as protective:

A healthy looking person could be HIV+: 26

■ “One does not require much information on these ages in

the adolescent age. More information, no doubt, tempts

them to do wrong things.” (father’s group, Mehra et al.,

2002, Delhi).

14

Interventions can overcome lack of awareness and

misperceptions:

BEFORE

ADOLESCENT GIRLS, ALLAHABAD

- Could name a STI:

- Knew how pregnancy occurs

ADOLESCENT BOYS, LUCKNOW

- Aware of multiple types of STIs

- Know that STIs can

be asymptomatic

AFTER

67

44

94

98

66

83

30-40

80

Sources: Sebastian, 2002 personal communication; Awasthi et al., 2000.

||

Underlying risk factors

and promising practices

2. Gender double standards and power imbalances

15

Gender roles and power imbalances

■ Priority on preserving young women’s virginity before marriage

but condoning sexual activity among young men

■ Supervision of the movements of daughters and relative freedom

to sons

■ Friendships between girls and boys are unacceptable

Girls, low-income setting, Delhi: 80%

Boys, low-income setting, Delhi: 25%

• Boys do not respect girls who have engaged in pre marital sex:

>66%

• Girls who engage in pre-marital sex always regret it: 80%

■ Limited decision making autonomy of adolescent females in sexual

and reproductive matters

Sources: Mehra et al„ 2002; Sodhi et al., 2002

ftpdfeClW

Gender roles and power imbalances

Many feel that society condones premarital sexual

activity among boys and even puts social pressures on

boys to become sexually active at an early age"... And if

the girl says no then boys defame her in her gali (lane)

and colony. Because there is no effect on boy’s

character” [19 year-old male student]

“[Boyfriend] kissed me forcefully...he gets angry if I talk

to anyone in the lane. One day he saw me talking to my

brother...he... beat me up. He was saying that boy was

my boyfriend... he beat me so much even then I did not

say anything to him because I love him so much” [indepth interview, 15 year-old girl, slum setting, Delhi]

Source: Sod hi, 2005 forthcoming.

16

Gender roles and power imbalances

■

% women aged 19-24 who had a say in marriage

decisions

rural Uttar Pradesh:

10-12

rural Tamil Nadu:

37-53

■

“Did I get the chance to say anything? Could I say

anything after my parents took the decision? What could

I have done? [in-depth interview, 18 year old recently

delivered mother in Kolkata]”

Sources: Jejeebhoy and Halli, 2002; Santhya et al., 2001.

Emerging evidence of self-efficacy, autonomy,

negotiation skills

Follow-up of a cohort of out-of-school adolescent girls two to five years

after exposure to a comprehensive education and service intervention:

□ Control Q Intervention

80

68

70

52

60

50

%

42

35

40

25

30

20

10

0

8

I

Economically

Active

7

25

21

US'*

■

■•L

'

6

■ .ik-z

Participates

in marriage

decision

Decides on

going to the

market

Decides on

how to

spend money

Travelled

outside

village alone

Has gone to

a health

centre alone j

Source: Levitt-Dayal et al., 2002

17

Emerging evidence of self-efficacy and autonomy

Follow-up of girls aged 14-19 who participated in a

reproductive health education and vocational skills training

programme:

□ Base-line (2001) m Endline (2003)

90

78

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

63

26

Can make self

understood to

others

26

25

15

13

Woman is not

inferior to men

Husband should

decide on

spending income

ii

Agree’’boys

preferred in

education over

girls"

Source: Sebastian et al., 2004

Underlying risk factors

and promising practices

3. Interaction, communication, supportiveness missing

4^ RyufatotCouMa

is

Interaction with parents and other adults

■

Limited communication: sex and reproduction are taboo

subjects; belief that talking about sex leads to sexual

activity

■

Supervision of the movements of daughters and relative

freedom to sons

Parental counselling and supportiveness limited

Teachers ambivalent: stress biological information over

broader issues of sexuality

Parental interaction: policing may not safeguard

against risky behaviour

“There are a lot of constraints on girls’ movements. But

they continue to meet their male friends stealthily. When

parents leam of these cases they generally forcibly get

them married off elsewhere after an abortion or agree to get

them married to the same boy.” (Adolescent girls, 17-19,

slum)

“There are some cases of pregnancies among unmarried

girls, we do have girls of this kind in our area. We do not

know them well and do not interact with them” (Adolescent

girls, 15-17, resettlement colony)

Source: Mehra et al., 2002

19

Interaction with parents: what young people want

■ We need more attention, care and support from all. We

feel we do not have the right to make our own choices,

even after learning about all the alternatives and choices

related to our careers, friends, movements and life

partners. We greatly lack proper and correct information

and guidance, especially related to our bodies’

physiological and psychological changes.

■ We are not allowed to express our emotions and our

thoughts. To our parents, we say that we need you to

listen to us, to our dreams, our experiences, our

explanations. Give us your time. Don’t hide things from

us, especially when they are related to us. Give us the

privacy and the space to grow. Guide us; don’t drive us.

Source: Singh. 2002, statement made at the UNFPA South Asia

Conference on Adolescents, New Delhi,1998

Pyyfafavj

Underlying risk factors

and promising practices

4. Lack of an available, accessible, acceptable service

environment

20

Limited use of services

49% of married young women experiencing gynaecological

problem in rural Maharashtra

9% of married 16-22 year olds experiencing

symptoms in rural Tamil Nadu

RTI/STI

About as likely as older women to seek pregnancy related

care

Unmarried adolescent abortion-seekers more likely than

other women to seek second trimester abortion, choose

home remedies and unqualified providers

Sources: Barua and Kurz, 2001; Joseph et al., 2002; Santhya and Jejeebhoy, 2002;

Ganatra and Hirve. 2002

Service environment and obstacles to care

■

Lack of autonomy

■

Lack of affordability

■

Long distances, waiting times

■

Poor quality of care

■

Lack of privacy, confidentiality

■

Providers lack counselling skills, are judgmental and

disrespectful.

■

Providers reluctant to providing services -notably

contraception - to unmarried youth

21

Making the service environment “youth friendly”

■ Accommodating young people’s stated priorities:

“a welcoming facility, where I can drop in and be

attended to quickly”

r

“...where thee is privacy and confidentiality,”

“where staff treat us with respect and do not judge

us,”

“where we can get a range of services so that we do

not have to be referred to different places for

treatment”

Source: Godinho, Dias-Saxena, Divan et al., 2002

Key SR rights of adolescents

22

India’s commitment to SRHR of Adolescents

■ ICPD and ICPD+5 Plans of Action and made a commitment

to “protect and promote the right of adolescents to the

enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health,

provide appropriate, specific, user-friendly and accessible

services to address effectively their reproductive and

sexual health needs, including reproductive health

education, information, counselling and health promotion

strategies.”

■ Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989) and its

general comment No. 4 (2003) on the main “human rights

that need to be promoted and protected in order to ensure

that adolescents

are adequately prepared to enter

adulthood and assume a constructive role in their

communities and in society at large.”

■ MDG goals cannot be achieved without attention to SRH of

adolescents

t

.

nlplwliffl Qwi

Key SR Rights of Adolescents

■ Protection from all harmful traditional practices notably

early marriage

■ Access to information

■ Access to health services, including counselling and health

services for sexual and reproductive health of appropriate

quality and sensitive to adolescents’ concerns

■ Opportunities to acquire life skills

■ A safe and supportive environment

Sources: CRC 2003, ICPD

23

Meeting these rights

■ How far have we come in aligning our own policies and

programmes with the commitments articulated in the CRC

and ICPD

■ To what extent have these rights been realised in terms of

the reality of young people’s lives?

■ Way forward

Protection from all harmful traditional practices

notably early marriage

24

Protection from all harmful traditional practices

such as early marriage

- CRC:

o State parties must [fulfil their] obligation to protect

adolescents from all harmful traditional practices, such

as early marriages... (para 39g)

o need to review and reform legislation and practice to

increase the minimum age for marriage with and without

parental consent to 18 years (para 20)

■ NPP (2000) and NYP (2003):

o special programmatic attention to delay marital age and

enforce the Child Marriage Restraint Act

Going further: Delay marriage and recognize the

vulnerability of married female adolescents

- REAL J IA ?

■ Secular trend towards increased marriage age: but at this rate,

by 2015 1/3 girls will marry in adolescence

o education for girls, programmes for parents, addressing

community norms and enforcing existing laws - to accelerate the

pace of change

o raise awareness of the negative impact of early marriage

o enhance married girls’ autonomy within marital homes: education,

life and livelihood skills and opportunities.

0

train providers to recognize married adolescent girls as a special

group

25

Access to information

Access to information

■ CRC:

o ensure that adolescents have access to the information that is

essential for their health and development (para 39b)

o including on family planning and contraceptives, the dangers

of early pregnancy, the prevention of HIV/AIDS and the

prevention and treatment of STIs regardless of marital status

and whether their parents or guardians consent. (Para 28)

■ICPD+5:

■ Ensure that adolescents, both in and out of school, receive the

necessary information, counselling and services to enable

them to make informed choices and decisions (para 73e)

26

Access to information

■NPP:

o ensure for adolescents access to SRH information

• NYP:

o information and education activities; incorporate sexuality

education within the school curriculum

•NAIDSP:

o generate greater awareness about nature of its transmission

|| RipufaCcwa

Going further: Attention to content and quality

• REAM I ¥?

■ As larger proportions of adolescents remain in school, larger

proportions will be exposed to school based sexuality

education programmes.

0

attention to content and quality of information

o reaching the out-of school

o Lessons from small scale innovative sexuality education strategies

o Sensitise trainers, counselors

o dispelling fears and misconceptions — no evidence that in-depth

awareness encourages risk taking

FbpdfltoGwid

27

Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability and Quality:

of sexual and reproductive health services and counselling

Access to SRH services

CRC:

o availability,

services

accessibility,

acceptability

and

quality

o effective prevention programmes

o address cultural and

adolescent sexuality...

other

taboos

surrounding

o remove barriers hindering the access of adolescents to

information,

preventive measures such as condoms,

and care.

o privacy and confidentiality...

o counselling and health services of appropriate quality

and sensitive to adolescents’ concerns

Source: paras 41, 33

28

Access to SRH services

ICPD+5

■ Ensure services that safeguard the rights of adolescents to

privacy, confidentiality and informed consent

■ Train all who are in positions to provide guidance to

adolescents, particularly parents and families, but also

communities, religious institutions, schools, the mass

media and peer groups

■ Ensure that attitudes of health care providers do not restrict

the access of adolescents to appropriate services and

information

■ Remove legal, regulatory and social barriers to reproductive

health information and care for adolescents

Source: ICPD+5 see paras 73b, e, f

Policies and programme commitments

■ NPP:

o ensure “access to... counselling and services, including RH

services, that are affordable and accessible;

o “strengthen PHCs and SCs to provide counselling, both to

adolescents and also to newly weds"

■ NYP:

o establish “adolescent clinics” for counselling and treatment

and Youth Health Associations at grass root level for family

welfare and counselling services

■ RCH-2 (proposed)

o Weekly adolescent health clinics at PHC, CHC and higher levels

29

Going further:

Integrate young people’s concerns into programmes

■REALITY? Ambiguities remain: Unmarried not eligible for

contraceptive services; married report unmet need for contraception

and lack pregnancy related care; Poor quality of care, lack of

confidentiality and privacy

o HW to provide SRH services including contraceptives to

unmarried females and males

o Providers to give

confidential services

sensitive,

non-judgmental,

private

and

o Redefine male health worker role to include SRH counselling and

services to young men

o Engage newly married young women and their husbands

(contraception, delaying pregnancy, appropriate care)

o Two-pronged effort: establish adolescent health clinics; supplies

and counselling also through other acceptable outlets, youth

clubs etc

Opportunities to acquire life skills and

address unbalanced gender role attitudes

30

Life skills development, redress gender imbalances

CRC, ICPD

■ ensure that adolescents...have opportunities... to acquire life

skills, to obtain adequate and age appropriate information, and to

make appropriate health behaviour choices. (CRC Para 39b)

• develop and implement awareness-raising campaigns, education

programmes and legislation aimed at changing prevailing

attitudes, and address gender roles and stereotypes(CRC Para 24).

■ Develop action plans, based on gender equity and equality that

cover education, professional and vocational training and income

generating activities, and incorporate mechanisms for education

and counselling in the areas of gender relations and equality,

violence, responsible sexual behaviour including contraception

and infection (ICPD+5, para?3c).

NPP, NYP:

■ not addressed but mentioned in RCH-2

Address life skills and gender role attitudes

•

REALITY?

■ Few programmes address life or livelihood skills, gender

double standards;

■ existing programmes are small-scale NGO efforts

■ Going further:

■ Expand life and livelihood skills programmes for youth, for

females but also males

■ Review, adapt and up-scale lessons learned from successful

demonstration projects that impart non-formaI, life skills, family

life, livelihood or vocational skills - for both females and males.

31

A safe and supportive environment

|| MtoiCw

Safe and supportive environment

CRC:

■ Creating a safe and supportive environment entails addressing

attitudes and actions of both the immediate environment of the

adolescent - family, peers, schools and services - as well as the

wider environment... (Para 14; 39a)

■

promote the health and development of adolescents by (a)

providing parents (or legal guardians) with appropriate

assistance.... (b) providing adequate information and parental

support to facilitate the development of a relationship of trust and

confidence in which issues regarding, for example, sexuality and

sexual behaviour and risky lifestyles can be openly discussed and

acceptable solutions found that respect the adolescent’s rights....

(CRC Para 16).

Cont...

32

Safe and supportive environment

ICPD:

■ ensure that parents and others responsible for rearing children are

educated about and involved in providing sexual and reproductive

health information in a manner consistent with the evolving

capacities of adolescents (para 73d)

NPP, NYP, RCH-2 (proposed):

■ Not addressed

Safe and supportive environment

• Parents unwilling to discuss & uncomfortable about

discussing sexual matters with adolescents & young

people

■ Going further: Sensitise parents and other adults to

provide more supportive environments for youth

■ Programmes for parents/adult gatekeepers

• about sexual and reproductive issues

■ breakdown inhibitions/discomfort

•improve communication skills

•address misperceptions: that talking about sex leads

adolescents to engage in risky sex

33

Last thoughts

■ No “best practices” models available

s feasibility, effectiveness and acceptability will

continue to remain poorly understood unless they are

rigorously and regularly monitored and assessed.

• Need to address sustainability and up-scaling

importance of inter-sectoral collaboration & public

private partnerships: Health and Family Welfare,

Education, Youth, NGOs...

o

*

34

I

4 Special articles

Long-Tenn Population Projections

for Major States, 1991-2101

The authors decompose the prospective population growth in 16 major states between

1991 and 2101 into three components to estimate the contribution of each of

them individually. The decomposition of population growth in different states seeks to

estimate the impact of growth momentum built into the age distribution of population and

the share ofprospective growth attributable to (a) the unmet need for family

planning and (b) high wanted fertility.

Leela Visaria, Pravin Visaria

In 1996, a decomposition ofthe projected long-term population

growth in India as a whole and an exploration of its policy

implications had elicited considerable interest among the plan

iven the scale and diversity of India’s population, a ners and policy-makers [Visaria and Visaria 1996].1 A similar

u

—woman in 1970, to analysis at the sub-national level for the major states of the

| ^decline

from around six children per

almost

half

that

level

in

a

span

of

30

years is a significant country was recommended as potentiaHy useful and instructive,

VJt___

j country, albeitt The case for such an exercise rested on the regional diversity

achievement. Fertility has declined throughout the

...

in

states in the level and pace of decline in fertility as well as in mortality

at varying pace in rural and urban areas or L.different

---------------^fiTKeSa^dTamilNadualready reaching replacement level, during the past several years and also on the fact that the onset

Fertility

Fertility in

in India

India has

has fallen

fallen under

under aa wide

wide range

range of

of socio-economic

socio-economic and the course of demographic transition m the Indian states

and cultural conditions. The rising levels of education, influence have varied. The 16 major states are at different stages of demoofthe media, economic changes, continuing urbanisation, decline graphic transition; and therefore, the analysis of interstate yanain infant and child mortality all have contributed to fertility tions in the role of different factors m long-run population

decline. The diffusion of new ideas and enhanced aspirations for growth was expected to highlight the appropnate state-specific

children has led even the uneducated parents to limit their family policy options.

size [Bhat 2002]. Fertility has fallen at all ages; at younger ages

This paperpresents long-term state level projections up to 2101.

due to rise in the age at marriage and at older ages due to control We decompose the prospective growth in each state in a manner

of fertility within mairiage through the adoption of family plan- similar to that followed for the national projections prepared m

ning (mainly sterilisation).

1996.2 The procedure relies on a series of population projections

Population projections made by the United Nations, the World with alternative assumptions about the rate of decline m fertility

Bank and demographers all indicate that India as a whole will and a likely course of mortality decline. The projections use:

attain replacement level fertility or complete the fertility tran (a) the state level base population and its five-year age distri

sition in the next 20 years [Visaria and Visana 1996, United bution available from the 1991 Census; (b) life expectancy at

Nations 2001, World Bank 2000, Natarajan and Jayachandran birth (separately for males and females), based on the Sample

2001, Dyson 2003]. However, the population size will continue Registration System (SRS) life tables for 1991-95; and (c) the

to rise for 50 to 60 years due to the recent history of high fertility SRS-based age-specific fertility rates for the period 1992-94.

that has resulted in young age structure and because, despite the In the different variants of projections, future trends in fertility

decline, the total fertility rate (TFR) for the country as a whole are assumed to vary, whereas only one pattern ofmortality regime

is still well above replacement level of TFR of 2.1. On the other is envisaged.

Decomposition of the future population growth in

hand, the welcome decline in mortality that began around 1921

m different

and accelerated since 1951 has caused substantial population states seeks to estimate the impact ofthe growth momentum built

growth in the past. However, since a significant proportion of into the young age distribution of population and the share of

deaths in India continue to be due to communicable diseases, prospective growth attributable to (a) the unmet need for family

their control will bring mortality levels further down in the planning and (b) high wanted fertility. A ‘standard’ population

’

L

coming decades. It is important to understand why population projection, which corresponds to the ‘medium’ projections m

most

such

exercises,

is

made

for

all

the

major

states.

The

second

will continue to grow in the years to come and the relative

contribution of the factors causing growth. An exercise in de- set ofprojections is based on the assumption that the replacement

composition of population growth would enable us to devise level fertility will be attained with immediate effect by all the

appropriate policy measures to affect growth.

states

states regardless

i

of their present actual levels. A third set ot

I

IntzoducticQ

..................................................

Economic and Political Weekly

November 8, 2003

’

’

4763

projections is based on the assumption (unrealistic, of course)

that the unwanted fertility will be eliminated within the next fiveyear period (or with almost immediate effect). In addition, a fourth

projection illustrates the implications of below replacement level

of fertility, such as has been observed in Kerala since 1988.

Assuming that this process will spread to the rest of India as

well, this fourth projection is essentially an extension of the

standard projection, in which the TFR is assumed to decline to

1.8 in each state and then remain stable at that level.

The expected absolute growth of population in each state

between 1996 and 2101 according to the standard projection is

decomposed to estimate and analyse the contribution to growth

of unwanted fertility, high desired fertility and population

momentum. Population growth resulting from unwanted fertility

will require identification of measures that would assist the

couples to achieve their reproductive goals in a manner that is

safe, affordable and accessible. The government-sponsored

family welfare programme needs to be responsive to individual

needs while offering good quality comprehensive services.

Population growth resulting from a desired family size or wanted

fertility that is higher than the replacement level of fertility will

require efforts to modify the preferences of couples about their

family size. To address this issue, a socio-economic environment

favouring small families will need to be created. Population

growth attributable to momentum can be reduced by measures

such as a later age at marriage among females, raising their age

at first birth (which would increase the length of generation),

and elongation of the inter-birth intervals.

The long-term projections have been prepared for 16 major

states with the 1991 Census population above five million.

Although 18 states had a population of more than five million

in 1991, we have not considered Delhi with a population of

9.4 million, of which nearly 90 per cent is urban, because

migration is a major factor influencing its population

growth. Jammu and Kashmir has not been considered because

the 1991 Census could not be conducted, and as a result, we do

not have an age distribution for the base period. Its population

was 6.0 million in 1981 and an estimated 7.7 million in 1991

[Office of the Registrar General 1998a: 4]. The all-India

projections, however, cover all the states and union territories

of the country.

I

The Indian states vaiy widely in terms oftheir total population.

Among the 18 major states with the 1991 Census population

exceeding five million, Uttar Pradesh had 139.1 million people,

nearly 27 times the population in Himachal Pradesh (5.2 million).

The other two populous states of Bihar and Maharashtra had a

population of 86 and 79 million, respectively. Together, the three

most populous states accounted for 36 per cent of the total

population ofthe country. In three other states ofAndhra Pradesh,

Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, population ranged between

66 and 68 million and the six states included almost 60 per cent

ofIndia’s population (505 out of846 million) in 1991. Population

of Gujarat, Karnataka and Rajasthan ranged between 41 and 45

million, whereas that of Tamil Nadu was close to 56 million.

Except for Himachal Pradesh, the 1991 population in the remain

ing five states ranged between 16 and 31 million (Table I).4

TrendsinMzrtality

The Indian states have varied in their mortality levels and in

the pace of mortality decline. As shown in Table 2, we have

chosen the expectation of life at birth (e (0)) as the indicator of

mortality during 1971-75 and 1991-95 to illustrate the differ

entials in the level ofmortality and the level ofinterstate diversity

in India over time. The estimates are shown separately for males

and females. During 1971-75, the difference between the highest

e (0) value of Kerala (62 years) and the lowest e (0) value of

Uttar Pradesh (43 years) was 19 years for both sexes together.

In 1991-95, among the major states, Madhya Pradesh reported

the lowest e (0) of 55 years, 18 years lower than that in Kerala

(73 years). The interstate difference of 15 years for males and

21 years for females reflected the uneven progress in the avail

ability of health care services and infrastructural facilities in

different parts of the country. During 1991-95, life expectancy

Table 1: Papulation Statistics for 16 Mtjar States of India, 1571-2001

State

1971

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Gujarat

Haryana

Himachal Pradesh

Karnataka

Kerala

Madhya Pradesh

Maharashtra

Orissa

Punjab

Rajasthan

Tami 1 Nadu

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

Alllhia

43.5

14.6

56.4

26.7

10.0

3.5

29.3

21.3

41.7

50.4

21.9

13.6

25.8

41.2

88.3

44.3

548.2

Rjpulatdcn (inmi 11 i<~n)

1981

1991

2001

2001

53.6

69.9

34.1

12.9

4.3

37.1

25.5

52.2

62.8

26.4

16.8

34.3

48.4

110.9

54.6

683.3

66.5

22.4

86.4

41.3

16.5

5.2

45.0

29.1

66.2

78.9

31.7

20.3

44.0

55.9

139.1

68.1

846.3

75.7

26.6

109.8

50.6

21.1

6.1

52.7

31.8

81.2

96.8

36.7

24.3

56.5

62.1

174.5

80.2

1027.4

1971-1981

1971-1981

Interoensal Growth (Per Cent)

1971-1991

1981-1991 1991-2001

23.1

24.2

24.1

27.7

28.8

23.7

26.7

19.2

25.3

24.5

20.2

23.9

33.0

17.5

25.5

23.2

24.7

23.5

21.2

27.4

20.8

21.1

14.3

26.8

25.7

20.1

20.8

28.4

15.4

25.5

24.7

23.8

13.9

18.9

33.6

22.5

28.1

17.5

17.3

9-4

22.7

22.6

15.9

19.8

28.3

11.2

25.5

17.8

21.3

52.9

53.4

53.2

54.7

65.0

48.6

53.6

36.6

58.8

56.5

44.7

49.3

70.5

35.7

57.3

53.7

54.4

1971-2001

74.0

82.2

94.7

89.5

111.0

74.3

79.9

49.3

94.7

92.1

67.6

78.7

119.0

50.7

97.6

81.0

87.4

NDtea:

Census was not conducted in Assam in 1981 and in Jammu and Kashmir in 1991 due to disturbed conditions.

The 2002 Census figures far the bifurcated states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh are included in the respective states.

Souzres: Census of India, 1971, 1981 and 1991. Series I, India, Final Itpulaticn Tables, New Delhi, Office of the Registrar General: Census of India 2001

Series 1, India, Provisicnal Papulation Ibtals, Raper 1 of 2001, New Delhi, Office of the Registrar General.

4764

Economic and Political Weekly

November 8, 2003

was below 60 years in all the four large north Indian states (Bihar,

Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) as well as in

Assam and Orissa.

In India as a whole, the female life expectancy at birth in 1991 95 exceeded the male life expectancy by a mere 1.2 years (a much

lower figure than is observed in the developed countries in

northern and western Europe, North America and Japan).5 In

fact, until 1976-80, the SRS reported a lower life expectancy for

females than for males in the country as a whole. The reversal

of this pattern became visible in the national estimates as female

life chances started improving throughout the country, more so

in all the four southern states and in Punjab and Maharashtra.

In all these states, according to the 1991-95 estimates, female

life expectancy was higher than that of males by more than

2 years. However, the anomaly of female disadvantage in life

expectancy has continued in the most populous states of Uttar

Pradesh and Bihar and to a small extent also in Orissa and Madhya

Pradesh. The gender gap in life expectancy was the highest in

Bihar (2.1 years), relatively moderate in Uttar Pradesh (1.3 years)

and less than halfa year in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh. In Assam

and Rajasthan, the female life expectancy has improved signifi

cantly, and as in India as a whole, the male life expectancy is

no longer higher than that of females.

A further examination of the data suggests that the anomaly

of lower life expectancy among females, wherever it is evident,

mainly reflects the sex-differentials in their chances of survival

in rural areas; in urban areas, the females enjoy a higher life

expectancy at birth than males in all the states.6 As for the future,

our mortality assumptions envisage a faster rise in female life

expectancy and the disadvantage ofwomen in chances ofsurvival

is presumed to disappear gradually over time.

By 1971, the regional differentials in fertility had begun to

appear in India. In 1970-72 the TFR in the southern states of

Kerala and Tamil Nadu was around 4, whereas in the northern

states of Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Rajasthan, it was above 6.7

By 1988, Kerala had attained a TFR below the replacement level

(2.0); and since 1993, Tamil Nadu has also attained the replace

ment level of fertility (a TFR of 2.1). During 1995-97, total

fertility rate in the other two southern states of Andhra Pradesh

and Karnataka had dropped to 2.9 and 2.7, respectively, from

around 3.9 and 3.6 reported in the mid-1980s.8 According to

the results of the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) of

1992-93 and 1998-99, the small western state of Goa with a

population of only 1.2 million in 1991 also had a TFR below

replacement level of 2.1 during the three years preceding the

survey.9 Because of its very small size, we have not done any

projection exercise for Goa.

On the other hand, fertility in some northern states has con

tinued to be quite high. Despite the evidence of some decline

in recent years, TFR ranged between 4.5 and 5.0 in Bihar,

Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh according to the SRS data for 199597. Evidently, the pace of decline has varied, such that the gap

between the low-fertility states and high-fertility states has widened

Table 3: Absolute and Percentage Change in Total Fertility

Rate, 1982-84 to 1992-94 in thaMajor States of Tnrtia

State

IttalFfertilityffete

1982-84

1992-94

TUI India

Kerala

Tamil Nadu

Andhra Pradesh

Karnataka

Maharashtra

Group 1 mean

Punjab

West Bengal

Gujarat

Orissa

Assam

Haryana

Group 2 Mean

Madhya Pradesh

Bihar

Rajasthan

Uttar Pradesh

Group 3 Mean

4.5

2.6

3.3

3.9

3.7

3.8

3.5

3.9

4.0

4.1

4.4

4.2

4.9

4.3

5.2

5.7

5.6

5.8

5.6

3.5

1.7

2.1

2.7

2.9

2.9

2.5

3.0

3.0

3.2

3.2

3.5

3.7

3.3

4.3

4.6

4.5

5.2

4.6

Deel i ne in the 10-Year Period

Absolute

Itercentage

Decline

Dy] ine

21.5

35.4

35.4

30.5

22.5

23.p

29.4

23.7

26.4

23.4

27.5

17.3

23.8

23.7

17.9

18.8

21.0

10.9

17.0

1.0

0.9

1.2

1.2

0.8

0.9

1.0

0.9

1.0

1.2

0.7

1.2

1.0

0.9

1.1

1.1

0.6

1.0

Table 2: Eetimates of Life Expectancy1 at Birth by Sex for the 16 Major States of India for 1971-75 and 1991-95

State

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Gujarat

Haryana

Himachal Pradesh

Karnataka

Kerala

Madhya Pradesh

Maharashtra

Orissa

Punjab

Rajasthan

Tamil Nadu

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

Alllrdia

e(0) in 1991-95

e(0) in 1971-75

Male

Female

Male

Fetrale

48.4

46.2

49.3

44.8

48.8

56.7

54.8

55.4

60.8

47.6

53.3

46.0

59.0

49.2

49.6

45.4

48.8

52.5

50.9

55.1

63.3

46.3

54.5

45.3

56.8

47.5

49.5

40.5

50.5

49.0

60.3

55.6

60.1

60.2

63.0

64.1

60.6

69.9

54.7

63.5

56.6

66.1

58.3

62.3

57.3

61.5

59.7

62.8

56.1

58.0

62.0

64.0

64.7

63.9

75.6

54.6

65.8

56.2

68.4

59.4

64.4

56.0

62.8

60.9

Increase in Years ine (0)

between 1971-75 and 1991-95

Male

Female

11.9

9.4

13.5

11.3

11.4

6.3

9.3

5.2

9.1

7.1

10.2

10.6

9.1

12.7

11.9

13.2

11.5

13.8

8.8

12.3

8.3

11.3

10.9

11.6

11.9

14.9

15.5

9.2

11.9

Years in Viiiche(O) will Reach

__________ Highest Levels___________

Nfale (79years)

Female (85 Years)

2056-61

2066-71

2056-61

2056-61

2051-56

2056-61

2056-61

2031-36

2071-76

2051-56

2066-71

2041-46

2061-66

2051-56

2066-71

2056-61

2061-66

2056-61

2071-76

2071-76

2061-66

2051-56

2056-61

2056-61

2026-31

2076-81

2056-61

2071-76

2046-51

2066-71

2051-56

2071-76

2056-61

2066-71

bbte:

Estimates for Bihar and West Bengal for the initial period are not available.

Sources: Registrar General, India, Occasional Papers No 1 of 1985, SRSBasedAbridgedLife Tables 1975-80. New Delhi.

Registrar General, India, SRS Analytical Studies, Report No 1 of 1998, SRSBasedAbridgedLife Tables, 1990-94 and1991-95, New Del hi.

Economic and Political Weekly

November 8, 2003

4765

from about 2 to 2.5 children in the 1970s to 2.5 to 3.2 children

in the 1990s. The 16 states fall in three distinct categories in terms

of fertility decline during 1982-84 and 1992-94: (a) those having

low initial level offertility and experiencing fast decline, (b) those

with moderate fertility level and moderate decline and (c) those

with high fertility and slow decline (Table 3).

As a result ofdifferences in the initial levels and pace ofdecline

in fertility and mortality during the recent past, the Indian states

are at different stages of demographic transition. The states of

Kerala and Tamil Nadu are much ahead of the large north Indian

states along the path of transition.10 Age at marriage, literacy

level (especially female literacy), access to and use of contra

ceptive and health care services, level of urbanisation and of

industrialisation also differ among different states.

I

Assumptions Underlying Population

Projections

The state-level projections presented in this paper begin with

the life expectancy at birth as reported for 1991-95 and the TFR

estimates for 1992-94.

Mbctality-Trends

For mortality decline, we have envisaged only one pattern. It

is presumed that consistent with the international experience, the

pace of mortality decline will slow down as life expectancy at

birth rises beyond 65 years. The initial estimates of life expect

ancy are taken from the 1991-95 state-level life tables, based on

the Sample Registration System [Office of the Registrar General

1998b]. In response to the ongoing efforts to control vaccinepreventable diseases and lowering of infant and child mortality,

life expectancy at birth is assumed to increase at a relatively faster

rate (implying an annual gain in life expectancy of 0.4 years for

males and 0.5 years for females) until it reaches 65. The annual

increase in life expectancy is expected to slow down thereafter

Table 4: Hat BxtarstataMLgxatlau during 1971-81 and 1981-91 as

Par Cent of Population Enunerated in 1981 and 1991 Censuses

.q-ate

Both Sexes

1981

1991

Males

1981

1991

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Gujarat

Haryana

Himachal Pradesh

Karnataka

Kerala

Madhya Pradesh

^harashtra

Orissa

Punjab

Rajasthan

Tamil Nadu

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

-0.8

-0.9

-0.4

2.8

-0.8

-2.7

1.1

4.2

-3.0

2.0

-0.6

0.5

4.0

-5.8

0.3

-2.3

1.4

3.8

13

2.3

-0.3

-0.2

-1.6

7.3

0.8

4.1

0.4

-2.9

1.6

5.0

1.0

2.7

-0.7

-0.4

-2.6

8.6

-03

2.3

-22

1.7

2.8

-1.6

0.4

-2.4

1.9

3.3

N

1.4

-0.8

-0.6

-2.7

6.0

0.5

-3.6

1.9

6.1

0.8

3.1

-1.0

-0.6

-3.5

9.9

2.7

-1.0

0.6

-2.6

1.9

4.1

-0.2

1.5

-12

-0.7

-3.4

6.6

Females

1981

1991

-0.7

1.9

-1.3

1.3

2.9

0.2

-2.1

1.9

2.6

0.3

1.3

-0.4

-0.4

-2.0

5.2

The estimates are based cn a definition of migrant as a perscn

reporting a 1 nnul -j t-ydi fferent from the place of enuneraticnas the

place of his previous or last usual residence.

N: ItegligibLe.

Sbtazxff.' Census of India, GecyraphicDiet^ributicn of Internal Migration in

India: 1971-81, New Delhi, 1989.

Census of India, 1991, State Profile, NewDelhi, 1998.

jNOteS:

4766

to 0.3 years for males and 0.4 years for females, until the life

expectancy reaches 70 years for both sexes. Thereafter, the annual

gain in the length of life is expected to slow down even further

to 025 years for males and 0.3 years for females.

We have assumed that the gain in life expectancy for females

will be faster than for males throughout the period. The peak

value in life expectancy reached by males is 79 years, and for

females it is 85 years. The age-specific mortality rates or

survivorship ratios, based on the SRS life tables, are assumed

to converge linearly to the pattern implicit in the ‘west’ model

life tables of Coale and Demeny when the e (0) attains its

maximum value.11

Given the different initial levels of life expectancy in 199195, the states are expected to attain the highest level of life

expectancy assumed by us in different years. Both men and

women in Kerala will attain the maximum level of e (0) within

the next 30 years. Except for Punjab in the case of both males

and females and Himachal Pradesh in the case of men only,

women in all the other states will take at least 30 more years

and men 20 more years to catch up with Kerala with respect to

the highest life expectancy.12

The future trends in fertility are difficult to predict. Recently,

a surprising plateauing or stagnation in the national TFR had been

evident since 1991. The TFR was 3.6 during 1991 -92,3.5 during

1993-95 and 3.4 during 1996-97. Therefore, our assumptions

about fertility decline in different states, including those'about

the year ofattainment ofreplacement level offertility, seem rather

arbitrary. The experience of Kerala since 1988 suggests that the

TFR can fall below the replacement level and continue at that

level; but it may either rise or fall further in the years to come.

The base period values of fertility for each state used in our

projections are the averages ofthe SRS age specific fertility rates

and total fertility rates estimated for 1992-94.

One variant of our projections (called standard projection)

assumes that in all the states, TFR would remain stable after it

reaches the replacement level. Another variant of the projection

assumes that unwanted fertility will be eliminated with immediate

effect and after that fertility will decline following the standard

path. In the third variant, fertility is assumed to drop to the

replacement level with immediate effect and continue at that level

in the future. In the fourth variant, we have assumed that in all

the major states, total fertility will drop below the replacement

level to 1.8, as has happened in the state of Kerala and is likely

to happen in Tamil Nadu.

Effect cfMigration

Prima facie, projections for different states of India seem more

difficult than the national projections because interstate migration

can be quite important and therefore estimates of the future

interstate net migration (inmigration minus outmigration) are

needed. At the national level, the volume of net international

migration has been unimportant in the past several decades and

can be ignored. Further, the census data for 1981 and 1991,

presented in Table 4, confirm that the net interstate migration

(measured in terms of persons reporting a place of last residence

different from the place of enumeration) accounted for only

about 3 to 6 per cent of the population even in Maharashtra and

Economic and Political Weekly

November 8, 2003

Therefore, for these two states, our standard projection and the

projection with below replacement level fertility are the same.

Table

‘ ‘ 5 shows the .period when **the major states will attain

.

replacement level of fertility. As noted above, Kerala and Tamil

Nadu had already attained the replacement level offertility (RLE)

by 1988 and 1993, respectively. The other two southern states

of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka are expected to attain RLE

by 2008. Fertility has declined rather rapidly in recent years in

the small mountainous state of Himachal Pradesh and in

.

Maharashtra, where TFR had dropped below 3 during 1992-94.

StandardProjecticns

However, according to our standard proj ections, these two states

The standard projections have assumed that fertility in each will take five years longer to reach the replacement level fertility

state will decline at the same annual rate as was observed during than Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka,

At the other end of the spectrum are the four large north Indian

the 10-year period between 1982-84 and 1992-94 in the state.

As shown earlier in Table 3, the states fell rather neatly into three states, and Haryana, where the TFR during 1991-95 was above 4.

groups. In

1 one group of stetes, which included the four southern If fertility in these states continues to decline at the slow pace

.

of

states < Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, observed in recent years, they would take 35 to 40 years to reach

amid Maharashtra, fertility had declined at an average annual rate the replacement level fertility. In between these two extremes

“

are a number of states both in Western and in Eastern India, such

of2.9 percent. In the second group ofsix states including Gujarat,

Haryana, Punjab, Orissa,?Assam and West Bengal, fertility had as Gujarat, Punjab, Assam, Orissa and West Bengal, where the

declined at an average rate of 2.4 per cent per annum. In the prevailing level of TFR during 1991-95 was between 3 and 3.5.

third group of four large north Indian states of Bihar, Uttar Their fertility transition is expected to be very similar to that

Pradesh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, the pace of fertility of Maharashtra and Himachal Pradesh. At the current pace of

decline during 1983-93 was the slowest at 1.7 per cent per annum. fertility decline, most of these states can expect to attain

These are also the states where the initial level of fertility was the replacement level fertility by 2013; only Assam will attain

it in 2018.

higher than that observed in the rest of the country.

In the standard population projection, in all the states except

Kerala and Tamil Nadu, once fertility reaches the replacement Projections BasedcnAssumedElimination

level of 2.1, it is assumed to stay at that level until the end of ofit^nntedFertility

the projection period. In the case of Tamil Nadu, if we assume

that fertility would continue to decline at the rate of 3.5 per cent

In the second set ofprojections, unwanted fertility is eliminated

per annum (the rate at which it declined between 1982-84 and with immediate effect. These projections attempt to bring out

1992-94), it would drop significantly below 2.1 to about 1.4 in the implications of meeting the unmet need for contraception or

a short span of 10 years. In Kerala also fertility declined at an eliminating the unwanted fertility ofcouples so that women have

annual rate of 3.5 per cent between 1882-84 and 1992-94 and only the children they want. The initial level of unmet need for

reached the below replacement level of 1.7 by 1993.13 Instead family planning or unwanted fertility in each state is assumed

of envisaging a reversal of the trend and a rise in fertility to the to be the same as the state-specific estimates of the extent of

replacement level in these two states, for the standard projection unwanted fertility estimated by the National Family Health Survey

we have assumed that the TFR will continue at the below conductedin 1992-93[IIPS 1995].Infourstates(AndhraPradesh,

replacement level of 1.8 until the end of the 21st century.14 Maharashtra, Punjab, West Bengal), if unwanted fertility is

West Bengal, where it was more important. Interstate migration

has been important in Delhi, the two north-eastern states of

Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura, and in the union territories of

Chandigarh, Pondicherry and Andaman and Nicobar Islands as

well as in Lakshadweep. However, we have not prepared separate

projections for these relatively small territories. Given the small

volume of migration even in major states, we have assumed it

to be an unimportant factor influencing population growth.

VA.

AV***

—-----------------------

—

Z

---- ---------------------------------------------

w

—

Table 5« Total Fertility Rate 1111991-95, Year Mme It Will ftwrihRaplaomMct Level CRL) acoording to Standard Projecticn

St^e

TFR below 3

Ksrala

Tamil Nadu

Andhra Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh

Karnataka

Maharashtra

TFUbetMsenJ. 0and4. 0

Punjab

West Bengal

Gujarat

Or-iRm

Assam

All India

TFR above 4. 0

Haryana

Madhya Pradesh

Bihar

Rajasthan

Uttaar Pradesh

TFR in 1996-2000

1991-95

2001-05

2006-10

2021-25

2026-31

Year WhenTFR Years Needed

Reaches RL

to Reach RL

2.1

NA

5

15

20

15

20

22

22

23

23

2.4

2.5

2.1

2.1

2.1

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.1

2.1

2013

2013

2013

2013

2018

2018

20

20

20

20

25

25

3.1

3.1

3.1

2.8

2.8

2.7

2.8

3.1

2.6

2.5

2.5

2.6

2.8

2033

2028

2028

2028

2033

40

35

35

35

40

2.1

2.5

2.7

2.6

2.7

2.3

2.4

2.3

2.4

2.1

22

2.1

22

3.0

3.0

3.2

3.2

3.5

3.6

2.7

2.7

2.8

2.9

3.1

3.2

2.4

2.4

2.6

2.6

2.7

2.8

4.2

4.3

4.5

4.5

5.1

3.8

3.8

4.0

4.0

4.5

3.4

3.4

3.5

3.5

3.9

November 8, 2003

2016-20

NA

1998

2008

2013

2008

2013

1.7

2.2

2.8

2.9

2.9

2.9

Economic and Political Weekly

2011-15

32

3.5

2.1

2.4

2.3

22

2.3

2.5

22

2.1

2.1

2.1

22

4767

eliminated, TFR level would drop very close to die replacement

level. In Himachal Pradesh, the gap between the prevailing total

fertility rate and wanted fertility was the highest in the country;

31 per cent of the current fertility was reported as unwanted.

Elimination ofunwanted fertility would lower the TFR in Himachal

Pradesh slightly below the replacement level. Surprisingly, even

in die states ofKerala and Tamil Nadu, where the estimated TFR

was close to or below the replacement level, 12 and 15 per cent

oftotal fertility was reported as unwanted, respectively.15 Wanted

fertility was significantly above the national average of TFR of

2.6 in all the four large north Indian states and also in Haryana

in north India; it ranged between 2.8 in Haryana and Rajasthan

and 3.8 in Uttar Pradesh.

In the states, where TFR was above the replacement level after

the unmet need or the unwanted fertility was eliminated, we have

assumed that the TFR would gradually decrease during successive five-year periods until it reaches the replacement level of

2.1. The year when that would happen will vary between the

states and would depend on the existing or initial level of fertility,

the extent of unwanted fertility (reported in the NFHS survey),

and the pace of decline in fertility observed in each state during

1982-84 and 1992-94.

The information on the extent of unwanted fertility, estimated

by the NFHS, is shown in Table 6. Admittedly, unwanted fertility

is unlikely to be eliminated suddenly. But the assumption of its

elimination is made in order to estimate the effect of unwanted

Tabla 61 Tbtal FertilityRata, MtaitedFertillty Rate aodtkMKxtad

Fertility aa Per Oent of TFRby State, 1992-93 (NFBSData)

State

TFR in

Wanted

Wanted

Unwanted UMrtedlfertility

ferala

Tamil Nadu

Andhra Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh

Karnataka

Maharashtra

Punjab

West Bengal

Gi^arat

Cirima

Assam

Alllrdia

Haryana

Madhya Pradesh

Bihar

Rajasthan

Uttar Pradesh

1992-93

Rrtility

RTtilfry

Rrtitity

as Per Cent of TFR

2.00

2.48

1.82

1.76

2.09

2.04

2.18

0.18

0.72

0.50

0.93

0.67

0.73

0.77

0.70

0.66

0.60

1.01

0.75

1.18

0.69

09.0

29.0

2.59

2.97

2.85

2.86

2.92

2.92

2.99

2.92

3.53

3.39

3.99

3.90

4.00

3.63

4.82

2.13

2.15

2.20

2.33

2.32

2.52

2.64

2.81

3.21

3.18

2.78

3.82

0.82

0.85

1.00

19.3

31.3

Projections BasedcnAssunption ofAttainment

In the third set of hypothetical population projections, fertility

is assumed to reach the replacement level in all the states with

immediate effect, regardless of the prevailing fertility levels in

each of the states. The TFR is assumed to drop to 2.1 during

the five-year period 1996-2001 and is assumed to stay at that

level until the end of the 21st century. In reality, fertility cannot

drop so drastically from a relatively high level, but the projections

based on this assumption help to estimate the contribution of

the momentum of population growth. The momentum is in

part due to a young age structure of population and in part

due to future improvements in mortality that are envisaged in

the country and built into the mortality regime assumed for

the projections. Again, we have not carried out this set of

projections for Kerala and Tamil Nadu, because it would

require raising their TFR from below replacement level to the

replacement level.

BelowReplaoementLevel fertilityProjections

The fourth set of projections is an extension of the standard

projections. Instead of assuming that fertility will stabilise at the

replacement level, with a TFR of 2.1, this set of projections

envisages that fertility would decline below the replacement level

up to a TFR level of 1.8. Under this projection, all the states

are assumed to maintain a TFR of 1.8 through the rest of the

21 st century after it is attained. Given the different levels ofinitial

fertility in the Indian states, and the variations in the pace at which

fertility has declined in recent years, the below replacement level

fertility will also be reached in different time periods.

23.5

25.5

26.4

24.7

22.1

20.5

28.6

22.1

29.6

17.7

20.5

23.4

20.7

Nttee: - Ffertilityrates are calculated cn the basisof births Airing the 0-36

rrenths before the interview of women aged 15-49.

- A birth was ccnsidered unwanted if the nuntoer of living children at

the time of conception was greater than or equal to the current ideal

nurber of children, as reported by the respondent. By subtracting

was derived,

- timet need for familyplanning includes need for spacing as well as

for limiting fertility, tlxret need for spacing is estimatedbytaking

account of the pregnant women whose pregnancy was mistimed,

women whose last birth was mistimed and those women who wanted

to wait two or more years before their next birth but were not using

any method of family planning, timet need for limiting is estinated

by taking into account of the pregnant women whose pregnancy was

unwanted, wcxnen whose last child was unwanted and who did not

want any children but were not using any family planning to avoid

beconing pregnant.

Source: Internaticnal Institute fcrKpulatirxiScienoes (UPS), 1995, National

FamilyJtfealth Survey, 1992-93, Bootoay, UPS.

4768

fertility on the long-term growth of population expected under

the standard projection in different states.

Population Growth According to Alternative

Proj actions

The population projections for 1991-2101 for all-India are

shown as Figures 1. Additionally, figures for one state from each

of the three groups are also given.16,17 For all the major states

and for India, the expected population in years 2051 and 2101

according to the standard projections is shown in Table 7 along

with the base population of 1991. The population of India is

expected to nearly double in a 60-year period during 1991-2051

from 846 million to 1620 million. However, the state-level

differences in the population growth would be quite large. By

2051, population is expected to more than double or increase

by nearly one and a half times in the large north Indian states

including Haryana from 352 million to 820 million. Thus, these

five states between them would contain more than half the

population of India in 2051.18 The population will increase by

about 75 per cent in most of the other states of the country. The

only two exceptions are Tamil Nadu and Kerala, where popu

lation growth over the next 60 years is expected to be less than

30 per cent.

Apart from the northern states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh,

Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, where population will range be

tween 106 and 337 million by 2051, the other states with a

Economic and Political Weekly

November 8, 2003

the states after reaching a peak in different years. This is evident

in the Figures 1 to 4 for all-India and the three states of Andhra

Pradesh, Guj arat and Madhya Pradesh. For the country as a whole,

2000

the population in 2101 with a below replacement level of

fertility would be 25 per cent smaller (1.36 billion as against 1.81

1800

billion) than if it is assumed to remain stable at the replacement

level. As might be expected, the extent of decline in total

population by 2101 would differ between the states, according

1600

to the year when the replacement level of fertility is expected

J

to be reached. The difference would be of the order of 30

J 1400

per cent in the six states of Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh,

Karnataka, Maharashtra, Punjab and West Bengal. In the

1200

four large north Indian states and Haryana, the expected popu

lation size in 2101 with a below replacement level of fertility

1000

would be about 20 per cent smaller than under the standard

projection.

800

If unwanted fertility were to be eliminated with immediate

effect, India’s population in the year 2101 would be about 13

per cent (240 million) smaller than is expected under the standard

600

’

1991 2001 2011 2021 2031 2041 2051 2061 2071 2081 2091 2101 projection(1.57billion as against 1.81 billion). As can be expected,

Year

the effect of this factor on the population size would be greater

RLFby 1998

RLFby 2018

in those states (Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Assam) where nearly

TFR of 1.8 by 2028

NSinerted fertility

30 per cent of the TFR was reported as unwanted fertility

population exceeding 100 million would be Andhra Pradesh, according to the 1992-93 NFHS data.

For India as a whole, the assumed immediate attainment of

Maharashtra and West Bengal. These seven states between them

will contain more than a billion people or 65 per cent of India’s a replacement level fertility would lower the 2101 population

by only 16percentbelowthestandardprojection(to 1.52billion).

estimated population of 1.6 billion.

The effect of attainment of replacement level fertility in all Relative to the projection envisaging an immediate elimination of

the states will be evident in the quantum of increase in unwanted fertility; total population with an immediate attainment

the population during the next 50-year period between 2051 and ofreplacement level of fertility would be only 3 per cent smaller.

2101. Although the net increase in population will continue In the demographically backward states such as Bihar, Madhya

to be positive in all the states, except Tamil Nadu and Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, population with an im

Kerala, the absolute increase in the country as a whole will mediate attainment of replacement level of fertility would be 30

be about 193 million, or 12 per cent above the figure reached per cent smaller than under the standard projection. In fact, in

these four states, the population size in the year 2101 would be

in 2051.

If fertility declines below the replacement level to a TFR of smaller under this assumption than ifthe below replacement level

1.8, the absolute size of population will begin to decline in all TFR of 1.8 is reached after the standard path of fertility decline.

FLgmlt Bopulafclcnof Ibdl&aoaaDdhvtoAltKxiafcivB

Aasuaptlcns, 1991*2101

Table 7: PryiinHcnnf

State

Kerala

Tamil Nadu

Andhra Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh

Karnataka

Maharashtra

Si±total

Per cent of total pcpulaticn

Punjab

West Bengal

Gujarat

Orissa

Assam

SLfctotal

Per cent of total pcpulaticn

All India

Haryana

Madhya Pradesh

Bitar

Rajasthan

Uttar Pradesh

Sctfcotal

Per cent of total pcpulaticn

In 1991. 2051 rad 2101 acxxodHagto Standard Projection, by State

1991

2051

2101

29.1

55.9

66.5

5.2

45.0

78.9

280.6

31.2

20.3

68.1

41.3

31.7

22.4

183.8

21.3

846.3

16.5

66.2

86.4

44.0

139.1

352.2

41.6

36.0

72.0

119.9

9.5

78.0

147.4

462.8

28.2

35.7

121.9

73.0

53.9

42.0

326.5

19.9

1619.5

41.1

148.0

188.0

106.1

337.0

820.2

50.0

25.2

57.0

130.5

10.3

85.0

159.6

467.6

25.4

37.9