TOBACCO HEALTH-CANCER-CONTROL REPORTS EPIDEMIOLOGICAL-FACTORS ETC.

Item

- Title

- TOBACCO HEALTH-CANCER-CONTROL REPORTS EPIDEMIOLOGICAL-FACTORS ETC.

- extracted text

-

RF_PH_7_SUDHA

c/XNCEK J>A'fTerjes

NC-^P -

B^^f\i-C> R.P- I1&2-

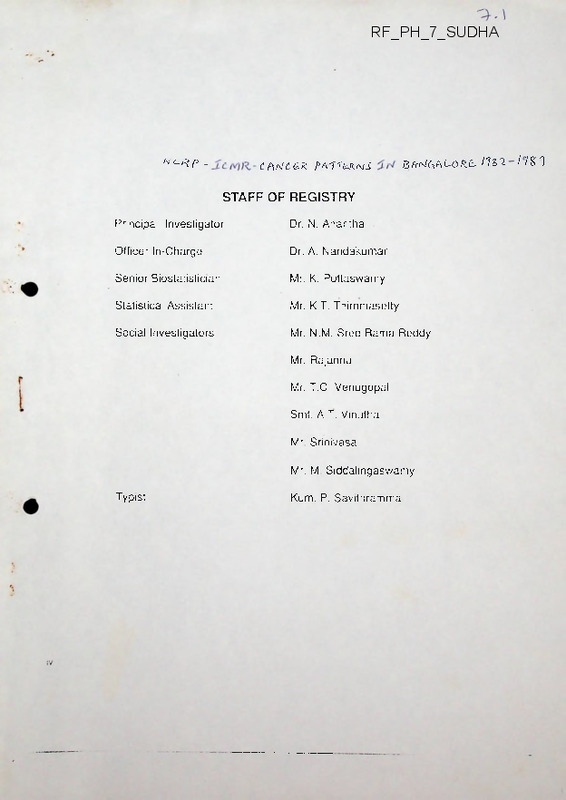

STAFF OF REGISTRY

Principal Investigator

Dr. N. Anantha

Officer In-Charge

Dr. A. Nandakumar

Senior Biostatistician

Mr. K. Puttaswamy

Statistical Assistant

Mr. K.T. Thimmasetty

Social Investigators

Mr. N.M. Sree Rama Reddy

Mr. Rajanna

Mr. T.C. Venugopal

Smt. A.T. Vinutha

Mr. Srinivasa

Mr. M. Siddahngaswamy

Typist

Kum. P. Savithramma

//S’*)

POPULATION-BASED CANCER REGISTRY BANGALORE

Year: 1989

Sex: Female

INCIDENT CASES OF CANCER BY MOST VAUD BASIS OF DIAGNOSIS AND SITE (ICD.9)

ICD

9TH

SITE

140 LIP

141 TONGUE

142 SALIVARY GLANDS

143 GUM

144 FLOOR OF MOUTH

145 OTHER MOUTH

146 OROPHARYNX

147 NASOPHARYNX

148 HYPOPHARYNX

149 PHARYNX ETC

150 OESOPHAGUS

151 STOMACH

152 SMALL INTESTINE

153 COLON

154 RECTUM

155 LIVER

15S GALL BALDDER

157 PANCREAS

158 RETROPERITONEUM

159 OTHER DIS SYS

160 NASAL CAVITY

161 LARYNX

162 LUNG

163 PLEURA

164 THYMUS

165 OTHER RES SYS

170 BONE

171 CONNECTIVE TISS

172 SKIN MELANOMA

173 SKIN OTHER

174 BREAST FEM

179 UTERINE UNS

180 CERVIX UTERI

181 PLACENTA

182 BODY UTERUS

183 OVARY

184 VAGINA

188 URI BLADDER

189 KIDNEY

190 EYE

191 BRAIN

192 NERVOUS SYSTEM

193 THYROID GLAND

194 OTH ENDO GLANDS

195 ILL DEF SITES

196 SEC LYMPH NODES

197 SEC RES ETC

198 SEC OTHER

199 PRIM UNK

200 LYMPHOSARCOMA

201 HODGKINS DIS

202 OTH LYMPHOMA

203 MULT MYELOMA

204 LEUK LYMPHATIC

205 LEUK MYELOID

206 LEUK MONOCYTIC

207 LEUK OTH SPE

208 LEUK UNS

ALLSITESTOTALS

%

MICROSCOPIC

n

%

8

5

24

3

68

5

3

7

75

27

0

19

17

5

4

5

2

6

13

4

1

0

12

16

227

5

253

0

21

42

5

5

20

0

46

2

8

6

4

1

3

10

21

5

8

23

0

0

4

1085

77.22

100.00

80.00

83.33

88.89

75.00

80.95

100.00

60.00

58.33

50.00

71.43

56.25

0.00

76.00

70.83

33.33

62.50

36.36

100.00

50.00

100.00

85.71

68.42

80.00

100.00

0.00

85.71

100.00

100.00

88.89

88.67

71.43

86.94

0.00

95.45

80.77

100.00

71.43

100.00

100.00

71.43

0.00

97.87

100.00

88.89

100.00

87.50

57.14

1.25

100.00

100.00

84.00

71.43

88.89

88.46

0.00

0.00

40.00

X-RAY

n

%

0

0

0

3

0

0

12

4

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

1

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

-o

3

0

0

0

0

1

0

3

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

CLINICAL ONLY

n

%

0

0

0

2

0.00

0.00

0.00

3.70

0.00

3.57

0.00

0.00

8.33

0.00

11.43

8.33

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

18.18

0.00

25.00

0.00

0.00

10.53

0.00

0.00

0.00

9

0

2

3

0

12

0

4

3

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

o

21

0

33

0

0

0.00

0.00

0.00

1.17

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

10.71

0.00

0.00

0.00

11.11

0.00

12.50

0.00

3.75

0.00

0.00

4.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0

2

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

39

2.78

117

8.33

81

0.00

0.00

0.00

7.41

25.00

10.71

0.00

40.00

25.00

0.00

11.43

22.92

0.00

16.00

12.50

16.67

12.50

9.09

0.00

25.00

0.00

0.00

5.26

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

8.20

0.00

11.34

0.00

0.00

7.69

0.00

28.57

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

2.13

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

28.57

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

14.29

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

OTHERS

n

%

D.C.O.

n

%

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0.21

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

1.90

0.00

0.00

4.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0

0

0

0

1

4

6

1

4

6

2

0

0

0

1

3

1

0

0

0

0

2

5

2

5

6

0

0

0

5

0

0

0

0

0

0

76

0

0

3

1

•j

3

0

0

6

161

11.46

0.00

20.00

16.67

0.00

0.00

4.76

0.00

0.00

8.33

50.00

3.81

12.50

100.00

4.00

16.67

50.00

25.00

36.36

0.00

0.00

0.00

14.29

15.79

20.00

0.00

0.00

7.14

0.00

0.00

1.95

28.57

1.72

100.00

4.55

11.54

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

17.86

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

14.29

95.00

0.00

0.00

12.00

14.29

11.11

11.54

0.00

0.00

60.00

TOTALS

n

%

10

6

27

84

5

5

12

2

105

48

25

24

12

8

5

4

7

19

5

0

14

18

256

7

291

22

52

14

7

5

28

0

47

2

9

6

8

80

3

10

25

7

9

26

0

0

10

1405

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

1 oo.oc

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

0.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

0.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

0.00

0.00

100.00

BANGALORE - 1989

MOST COMMON FORMS OF CANCERS

[males |

STOMACH

OESOPHAGUS

LUNG

PROSTATE

HYPOPHARYNX

TONGUE

RECTUM

LARYNX

[females |

CERVIX UTERI

BREAST

MOUTH

OESOPHAGUS

OVARY

STOMACH

THYROID GLAND

COLON

* AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION)

82

.

-

■ '

'

Trends Over Time

■ able G 3 gives the Age Adjusted Incidence Rales (AAR) and three year Moving Averages (MA) ol tobacco related

sues of cancer lor different years. The same is graphically represented in Fig 6.1 There is a clear rising trend in the

overall incidence of these cancers in males, whereas in females the rates are about the same over the ye'ars 1982

to 1989 The values of AAR for specific tobacco related sites is given in Tables 6.4 and 6.5.

Table 6.3

TOBACCO RELATED CANCERS - TRENDS OVER TIME : 1982 - 1989

ALL SITES OF CANCER ASSOCIATED WTIH USE OF TOBACCO - MALES AND FEMALES

Table gives figures ol AAR and 3 year Moving Averages (MA) of AAR

YEAR

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1982-89

49.68

45 90

39.94

42.08

MALE

38.11

41.92

40.73

40.51

37.94 *

MA

40.3

41.1

39.7

L2.7

44.5

FEMALE

27.35

23.58

2625

22.86

24.93

MA

25.7

24.2

24.7

24.2

25.2

45.2

24.79

25.83

27.47

25 40

26.0

Fig 6 1

TOBACCO RELATED CANCERS - TRENDS OVER TIME ; 1982 - 1989

ALL SITES OF CANCER ASSOCIATED WTIH USE OF TOBACCO - MALES AND FEMALES

Figure shows line graphs ol 3 year Moving Averages of AAR

VLAR

Male

Female

Tobacco Related cancers (TRC):

>cancers of the oral cavity,pharynx,

and urinary

bladder

larynx,

oesophagus,

considered

are

as

the

cancer

lung

6a

sites

related to Tobacco use.The paportion of these cancers by sex

is shown below.

Tobacco related cancers by sex

EMALE

MALE

% TO

NO.

SITE

TRC

ALL SITES

TOTAL

% TO

NO.

% T

NO.

TRC

ALL SITES

TRC

AL

Oral cavity

386

24.5

12 16

553

58 2

14.87

939

37.2

Pharynx

503

31.9

15 84

97

10 2

2.60

600

23.8

Oesophagus

318

20.2

10 01

238

25 0

6.40

556

22.0

Larynx

157

10.0

4 94

17

1 9

0.46

174

6.9

Lung

187

11.9

5 89

37

3 9

1.00

224

8.9

Uri.Bladder

24

1.5

0 76

8

0 8

0.22

32

1.3

Total

1575 100.0

49 6

950 100 0

25.5

2525

100.0

All sites

3174

6892

3718

Tobacco related cancers constituted 37% of all cancers in

both

sexes.

males

and

It

26%

accounted

in

for

females.

No

about

50%

of

significant

all

cancers

change

in

in

the

relative proportions in the TRC have been observed over the

years. Among males,

one third of TRC were cancer of pharynx

followed by cancers of the oral cavity & oesophagus.

It can be observed that,

■

among Tobacco

Related Cancers

of

oral cavity in females was more than double compared to

the proportion

in

males.

This

could

be

mainly

due

to

the

habit of chewing which is very common in females more so from

the rural folk.

TOBACCO RELATED CANCERS

HOSPITAL CANCER REGISTRY 1995, KIMIO

■ males

MALES-1575(49.6%): FEMALES-950(25.5%)

O females

cancer incidence rate was observed in each registry. While in Barshi (rural) , on an average one out of 24 to 25

persons get cancer in their lifetime. While in Connecticut (USA) and in United kingdom (Oxford), on an average one

out of 6 to 8 persons get cancer (0-64 years).

2.8

MOST COMMON FORMS OF CANCERS

The most common forms of cancers observed in men and women in Bangalore, Bombay, Madras, Delhi Bhopal

and Barshi areas are presented in Table 2.8.

TABLE 2.8 : MOST COMMON FORMS OF CANCERS (1989) - MALES

RANK BANGALORE

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

1.

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung (14.6)

Oesophagus

(11-5)

Larynx

(8.8)

Hypopharynx

(8.2)

Stomach

(7.0)

Prostate

(6.9)

Tongue

(6.5)

Mouth

(5.8)

Stomach

(16.5)

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung (13.5)

Oesophagus

(10.2)

Mouth

(7.3)

Hypopharynx

(6.5)

Larynx

(5.5)

Tongue

(5.3)

Rectum

(4.5)

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung (11.9)*

Larynx

(8-6)

Tongue

(7.7)

Oesophagus

(6.4)

Prostate

(6.3)

Uri. Bladder

(5.6)

Lymphoma

(5.1)

Brain

(3.4)

Stomach

(3.4)

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung (14.1)

Tongue

(13.2)

Mouth

(10.4)

Hypopharynx

(8.4)

Oesophagus

(7.7)

Prostate

(5.6)

Rectum

(5.5)

Stomach

(3.7)

Oesophagus

(6.7)

Penis

(51)

Rectum

(4.7)

Hypopharynx

(3.5)

Mouth

(3.4)

Skin,other

(2.7)

Liver

(26)

Stomach

(3.4)

RANK BANGALORE

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

1.

Cervix Uteri

(26.4)*

Breast

(223)

Mouth

(11-1)

Oesophagus

(10.2)

Ovary

(4.7)

Breast

(26.1)

Cervix Uteri

(19.4)

Oesophagus

(8.2)

Ovary

(7.0)

Mouth

(3.9)

Cervix Uteri

(43.5)

Breast

(24.6)

Mouth

(8.2)

Oesophagus

(7.7)

Stomach

(7.1)

Cervix Uteri

(30.1)*

Breast

(28.3)

Ovary

(8.7)

Gall Bladder

(6.6)

Oesophagus

(4.6)

Cervix Uteri

(26.2)

Breast

(6.8)

Bone

(2.4)

Skin,other

(23)

Rectum

(1.7)

6.

Stomach

(4.3)

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung(3.7)

Ovary

(6.0)

Brain

(2.6)

Cervix Uteri

(24.3)

Breast

(21.9)

Mouth

(6.8)

Ovary

(6.2)

Oesophagus

(5.2)

Gall Bladder

(5.2)

Body Uterus

(4.2)

7.

Thyroid Gland

(3.2)

Stomach

(3.4)

Hypopharynx

(2-7)

8.

Colon

(23)

Rectum

(26)

Rectum

(2.6)

Body Uterus

Trachea, Bronchus

(2.5)

4 Lung (3.2)

Mouth

(2.5)

Stomach

Colon

(2.4)

(2.1)

Lymphoma

Thyroid Gland

(2.4)_____________ (2.1)

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Stomach

(9.5)*

Oesophagus

(9.4)

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung (8.6)

Prostate

(7.1)

Hypopharynx

(5-9)

Tongue

(4-7)

Rectum

(4.3)

Larynx

(4.1)

FEMALES

2.

3.

4.

5.

‘Age-adjusted (world population) cancer incidence rate, per 100,000 persons.

12

Oesophagus

(1-4)

Lymphoma

(1-4)

2.9

SOME OBSERVATIONS ON SELECTED CANCER SITES

2.9.1

Lip, Oral Cavity and Pharynx (ICD.9 : 140-149)

Malignant tumours of the lip, oral cavity and pharynx are the most common site group of cancers in the Indian

registries i.e., Bangalore, Bombay, Madras, Delhi, Bhopal and Barshi (Table 2.9.1).

The total incidence of the lip, oral cavity and pharynx cancers disguise very large differences in the individual

sites in the Indian registries. The tongue (mainly base tongue), mouth, oropharynx and hypopharynx are the

predominant sites in this group.

There is also a marked variation in the incidence of lip, oral cavity and pharynx cancer in different countries.

Indian registries display much higher age adjusted and truncated rates than those reported by other registries in

Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (Vol. V,1987). Although this grouping includes cancers of quite distinct etiology

(e.g. cancers of the oral cavity, nasopharynx and hypopharynx). The global picture is dominated by the incidence of

oral cancer in Southern Asia and of oral cavity plus nasopharynx cancer in South-Eastern Asia.

Oral cancer is one of the 10 most common cancers in the world. In India, Bangaladesh, Pakistan and Srilanka,

it is the most common and accounts for about a third of all cancers. More than 100,000 new cases occur every year

in south and South-East Asia, with poor prospect of survival (Bull. WHO, 1984).

TABLE 29.1 : LIP, ORAL CAVITY AND PHARYNX (ICD 9:140-149)

MALES*

ICD.9

SITE

140-149 Lip, Oral Cavity

& Pharynx

140

Lip

141

Tongue

142

Salivary Glands

143-145 Mouth

146

Oropharynx

147

Nasopharynx

148

Hypopharynx

149

Pharynx Etc.

BANGALORE

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

17.5

26.8

23.6

19.4

38.8

10.8

0.4

4.7

0.8

3.0

1.9

0.6

5.9

0.2

0.3

6.5

0.4

5.8

3.2

0.6

8.2

1.8

0.6

5.3

0.4

7.3

1.9

0.6

6.5

1.0

0.5

7.7

0.8

3.7

3.2

0.6

2.3

0.6

0.2

13.2

0.5

10.4

3.8

0.0

8.4

2.3

0.0

2.1

0.5

3.4

0.0

0.0

3.5

1.3

BANGALORE

BOMBAY'

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

14.9

9.5

14.7

6.4

10.4

1.1

0.1

1.0

0.5

11.1

0.5

0.4

1.2

0.1

0.2

1.9

0.3

3.9

0.6

0.2

1.5

0.9

0.3

2.1

0.2

8.2

0.4

0.3

2.7

0.5

0.3

1.3

0.5

2.5

1.0

0.2

0.6

0.0

0.0

1.4

0.0

6.8

0.5

0.5

0.8

0.4

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.6

0.0

0.0

0.5

0.0

FEMALES*

ICD.9

SITE

140-149 Lip, Oral Cavity

& Pharynx

140

Lip

141

Tongue

142

Salivary Glands

143-145 Mouth

146

Oropharynx

147

Nasopharynx

148

Hypopharynx

149

Pharynx Etc.

‘Age-adjusted (world population) cancer incidence rate, per 100,000 persons.

Relative risk of oral cancer in people with various tobacco habits, as well as the frequency of those habits, based

on retrospective case control studies in India and Srilanka are noteworthy. There is a wide variation in frequencies

and risks in different regions, but certain conclusions stand out. Approximately, 90% of oral cancers in south and

south-east Asia can be attributed to tobacco chewing and smoking habits (Bull. WHO, 1984).

Case-control studies conducted in different parts of India have demonstrated that cancers of the oral cavity and

pharynx are associated to a wide variety of tobacco chewing (pan chewing and betel nut with tobacco, lime and other

ingredients) and smoking habits prevalent among men and women. These associations are statistically significant.

Although it is difficult to obtain precise estimates of the risk for oral cancer associated with specific substance, it is

clear that almost all of the risk is due to smoking of tobacco and the chewing of quids of various kinds. Notani et al.

(1989) estimated the attributable risks associated with these habits as 61 % for oral cancer (81 % for males, 36% for

females) and 79% for cancers of the pharynx and larynx (90% for males, 30% for females).

The most obvious and efficacious measure of control for oral cancer in I ndia would be the elimination of chewing

and smoking habits. I ntervention studies carried out in some parts of I ndia show that leukoplakia, a possible precursor

of oral cancer, does regress rapidly after cessation of betel chewing (Mehta et al., 1982). Education programmes

which reduced the prevalence of chewing and smoking tobacco also seem to have had an effect in reducing rates

of leukoplakia (Gupta et al., 1990).

TABLE 2.9.1b: COMPARISON OF LIFE TIME CUMULATIVE CANCER INCIDENCE RATES (0-64 YEARS), 1989.

UP, ORAL CAVITY AND PHARYNX (ICD-9 ; 140-149)

CUMULATIVE RISK

(%)

REGISTRY

2.9.2

ONE IN HOW MANY

PEOPLE WILL GET CANCER

IN THEIR LIFE TIME

MALE

FEMALES

MALE

FEMALE

BANGALORE

1.2

0.8

83

125

BOMBAY

1.8

0.6

56

167

MADRAS

1.6

1.1

DELHI

1.3

0.5

62

77

200

BHOPAL

2.8

1.0

36

100

BARSHI

0.9

0.1

111

1000

91

DIGESTIVE ORGANS AND PERITONEUM (ICD9 :150-159)

In the digestive system, the oesophagus and stomach are the most frequently affected sites in the Indian

Registries (Table 2.9.2).

TABLE 2.9.2 : DIGESTIVE ORGANS AND PERITONEUM (ICD 9:150-159) -1989.

(a) MALES*

ICD.9

SITE

BANGALORE

150-159 Digestive Organs 33.0

& Peritoneum

Oesophagus

9.4

150

Stomach

151

9.5

Small Intestine

0.0

152

Colon

2.7

153

Rectum

154

4.3

Liver

155

3.2

Gall Baldder

0.5

156

Pancreas

1.7

157

Retroperitoneum

0.9

158

Other

0.8

159

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

35.5

37.0

22.3

25.4

18.6

11.5

7.0

0.5

4.0

3.9

3.5

1.6

2.5

0.3

0.7

10.2

16.5

0.1

2.0

4.5

1.9

0.3

1.4

0.1

0.0

6.4

3.4

0.2

2.0

3.0

2.2

1.9

2.3

0.3

0.6

7.7

3.7

0.0

1.4

5.5

2.1

2.6

2.4

0.0

0.0

6.7

1.2

0.0

2.0

4.0

2.6

0.0

0.0

2.1

0.0

* Age-adjusted (World Population) Incidence Rate, Per 100,000 Persons.

14

(b) FEMALES*

ICD.9

SITE

BANGALORE

150-159 Digestive Organs 22.8

& Peritoneum

150

Oesophagus

10.2

151

4.3

Stomach

152

Small Intestine

0.0

2.3

153

Colon

154

Rectum

2.2

1.0

155

Liver

0.8

156

Gall Bladder

157

Pancreas

1.0

0.5

158

Retroperitoneum

0.5

159

Other

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

23.9

20.2

20.6

15.5

5.5

8.2

3.4

0.3

2.4

2.6

1.8

2.3

1.8

0.6

0.5

7.7

7.1

0.0

0.8

2.6

0.6

0.6

0.7

0.1

0.0

4.6

2.4

0.2

2.0

1.8

1.1

6.6

1.3

0.3

0.3

5.2

1.1

0.0

2.1

0.0

1.1

5.2

0.8

0.0

0.0

1.4

1.3

0.0

0.5

1.7

0.0

0.0

0.6

0.0

0.0

* Age-adjusted (world Population) Incidence Rate, Per 100,000 Persons.

2.9.2.1

Cancer of the Oesophagus (ICD.9 :150)

Oesophageal cancer is characterised by an extreme diversity of rates throughout the world. There are usually

more cases among males then females (Table 2.9.2.1).

It is interesting to observe that the cancer of the oesophagus in India mainly occur in the persons who are 30

years and above and age-specific incidence rates vary between 1 and 75 per 100,000. In 1989, age-adjusted

incidence rates of cancer of the oesophagus in males are Bangalore (9.4), Bombay (11.5), Madras (10.2), Delhi (6.4),

Bhopal (7.7) and Barshi (6.7), While in females, the rates are lower than males, except Bangalore (10.2); in other

centres rates are Bombay (8.2), Madras (7.7), Delhi (4.6), Bhopal (5.2) and Barshi (1.4).

One of the prominent epidemiologic characterstics of the oesophageal cancer isthe great variability in sex ratios

reported in different geographical regions of the world. The typical pattern of male preponderance has been noted

by several registeries. The sex ratios in urban areas in India vary between (M/F = 0.9 : 1) and (M/F = 1.5 : 1). In

Barshi rural population the sex ratio is (M/F = 5.6 :1).

TABLE 2.9.2.1: INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF AGE-ADJUSTED (AAR) AND

TRUNCATED TR) (35-64 YEARS) INCIDENCE RATE PER 100,000 PERSONS.

OESOPHAGUS CANCER (ICD.9:150)

(a) MALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1978-82

1978-82

1978-81

1978-82

CHINA (SHANGHAI)

SINGAPORE (CHINESE)

JAPAN (MIYAGI)

USA (CONNECTICUT) WHITE

BLACK

UK (OXFORD)

FINLAND

INDIA

BOMBAY

MADRAS

BANGALORE

BHOPAL

DELHI

BARSHI

20.8

13.5

13.3

5.1

24.0

3.6

3.7

21.0

13.9

14.5

6.2

47.8

2.8

3.4

11.5

17.3

10.2

9.4

7.7

6.4

6.7

19.6

14.3

13.4

10.7

10.4

1979-82

1977-81

1989

15

FEMALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1978-82

1978-82

1978-81

1977-81

1979-82

1978-82

CHINA (SHANGHAI)

SINGAPORE (CHINESE)

8.9

3.5

9.7

4.1

JAPAN (MIYAGI)

FINLAND

UK (OXFORD)

• USA (CONNECTICUT) WHITE

BLACK

INDIA

BANGALORE

BOMBAY

MADRAS

BHOPAL

DELHI

3.1

2.4

2.9

1.5

6.0

2.5

1.8

3.6

1.9

11.8

10.2

8.2

7.7

5.2

4.6

1.4

20.8

15.8

16.1

11.1

10.0

2.0

1989

BARSHI

* World Population

Source : Cancer Incidence In Five Continents, Vol. V.1987. NCRP Data, 1989

In Bombay, where oesophageal cancer is almost as common as in men as in women, drinking of the local

alcoholic brews and smoking of bidis & cigarettes are associated with particularly high risks in men, but chewing of

tobacco quids, smoking and drinking explain only a small fraction of the incidence in women (Jussawalla &

Deshpande, 1971). Notani et al. (1989) estimated that 34% of oesophageal cancer in India is related to tobacco use,

although the percentages for males (50%) and females (13%) are very different.

2.9.2.2. Cancer of the Stomach (ICD.9 : 151)

In 1980, stomach cancer was estimated to be the single most common form of cancer in the world, accounting

for some 670 000 new cases per year (10.5% of all cancers) (Parkin etal., 1988). It is probably now the second most

common cancer, after lung cancer. The highest incidence rates occur in Japan (Males - 79.6; Females - 36.0 per

100,000) and lowest rates in Kuwait (Males - 3.7, Females -1.6) (Table 2.9.2.2).

Age-adjusted incidence rates of stomach cancer in India are low. In 1989, the rates in men in Madras (16.5) is

iTOre than Bangalore (9.5), Bombay (7.0), Bhopal (3.7), Delhi (3.4) and Barshi (1.2). Thus stomach cancer, in men,

in Madras is frequent where the incidence is almost 1.5 times than Bangalore, double that in Bombay and over three

times as frequent as in Delhi and Bhopal. The female incidence rates are lower than males: Madras (7.1), Bangalore

(4.3), Bombay (3.4), Delhi (2.4), Bhopal (1.1) and Barshi (1.3).

The incidence and mortality rates in males are approximately double those for females in both high-risk and

low-risk countries.

The most remarkable feature of the epidemiology of gastric cancer is the universal decline in its incidence and

mortality. The decline is about 2-4% per year, but there is a lot of variation between different countries. Rates are

falling more rapidly for females than for males.

Christopher et al (1986) have indicated that, between 1950 and 1979, the Scandinavian countries, Switzerland

and the USA exhibited the greatest percent decrease (65% - 73%) in their gastric cancer mortality rates. Western

Euporean countries showed the next greatest percent decrease (59% - 62%), followed by Australia (56%). The

countries that demonstrated the smallest percent change in gastric cancer mortality over the 29-year period were

Japan and Italy (44%), and Northern Ireland (41%). The authors conclude that the major etiologic influences in gastric

cancer are environmental rather than genetic.

Data from cancer registries indicate that the temporal changes in the incidence of gastric cancer in Norway

(Munoz & Asvall, 1971) and Japan (Hanai et al., 1982) are due largely to the disappearance of the'intestinal' type

16

of gastric cancer as opposed to the 'diffuse' type.

Case-control and cohort studies in a wide variety of populations have shown increased risk associated with

more frequent use of starchy foods (such as corn, wheat, rice, potatoes, and beans), smoked, salted and fried foods,

and a decreased risk associated with the more frequent intake of green leafy vegetables, citrus fruits and dairy

products (Hirayama, 1980).

TABLE 29.2.2: INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF AGE-ADJUSTED (AAR) AND

TRUNCATED (TR) (35-64 YEARS) INCIDENCE RATE PER 100,000.

STOMACH CANCER (ICD-9 :151)

MALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1978-81

JAPAN (MIYAGI)

FINLAND

UK (OXFORD)

USA (CONNECTICUT) WHITE

BLACK

KUWAIT: KUWAITIS

INDIA

MADRAS

BANGALORE

BOMBAY

79.6

24.6

20.2

111.8

10.8

19.4

3.7

11.5

22.0

4.1

32.6

16.3

BHOPAL

DELHI

16.5

9.5

7.0

3.7

3.4

BARSHI

1.2

1977-81

1979-82

1978-82

1979-82

1989

25.7

225

9.5

8.5

6.2

3.9

FEMALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1978-81

1977-81

1979-82

1978-82

JAPAN (MIYAGI)

FINLAND .

UK (OXFORD)

USA (CONNECTICUT) WHITE

BLACK

KUWAIT: KUWAITIS

INDIA

MADRAS

36.0

12.9

7.8

4.3

9.1

1.6

50.5

13.7

6.8

4.5

11.3

2.0

7.1

4.3

3.4

24

1.1

1.3

17.4

8.4

1979-82

1989

BANGALORE

BOMBAY

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

6.1

5.0

3.0

4.1

* World Population

Source : Cancer Incidence In Five Continents, Vol. V.1987. NCRP Data, 1989

2.9.3

RESPIRATORY AND INTRATHORACIC ORGANS (ICD 9 : 160-165)

In the respiratory and intrathoracic organs, cancers of the larynx and trachea, bronchus and lung are the most

affected sites (Table 2.9.3).

17

TABLE 2.9.3a : RESPIRATORY AND INTRATHORACIC ORGANS (ICD 9:160-165) -1989.

MALES*

ICD.9

SITE

BANGALORE

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

IBHOPAL

BARSHI

160-165 Respiratory

13.7

25.1

17.6

21.3

19.0

3.3

0.3

4.1

8.6

1.4

8.8

14.6

0.6

5.5

11.1

0.5

8.6

11.9

1.6

2.9

14.1

0.0

1.3

2.0

0.6

0.1

0.0

0.2

0.1

0.0

0.2

0.2

0.0

0.2

0.1

0.0

0.4

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

163

164

165

& Intrathoracic

Nasal Etc.

Larynx

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung

Pleura

Thymus etc.

Other

ICD.9

SITE

BANGALORE

BOMBAY

MADRAS

DELHI

BHOPAL

BARSHI

160-165 Respiratory

3.3

6.3

2.8

4.6

4.6

0.0

0.4

0.7

1.6

1.0

1.3

3.7

0.8

0.3

1.7

0.4

1.8

2.2

0.4

0.5

3.2

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.5

0.1

0.0

0.2

0.1

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.2

0.0

0.0

0.5

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

160

161

162

•

FEMALES*

160

161

162

163

164

165

& Intrathoracic

Nasal etc.

Larynx

Trachea, Bronchus

& Lung

Pleura

Thymus etc.

Other

* Age-adjusted (World Population) Incidence Rate, Per 100,000 Persons

2.9.3.1 Cancer of the Larynx (ICD.9 : 161)

The age-adjusted incidence rate of laryngeal cancer in Indian material is high in men than women. Among men,

the highest incidence rates are in Bombay (8.8 per 100,000) and Delhi (8.6 per 100,000), during the period 1989.

•

TABLE 2.9.3.1 : INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF AGE-ADJUSTED

(AAR) AND TRUNCATED (TR) (35-64 YEARS) INCIDENCE RATE PER 100,000.

LARYNX CANCER (ICD-9:161)

(a) MALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1978

1978-82

BRAZIL (SAO PAULO)

17.8

USA (CONNECTICUT) BLACK

WHITE

FINLAND

UK (OXFORD)

SWEDEN

INDIA

12.6

7.7

4.5

4.2

2.8

27.6

24.8

12.4

7.1

5.8

4.1

8.8

8.6

5.5

4.1

2.9

1.3

15.6

19.7

8.9

8.3

5.3

4.1

1977-81

1979-82

1978-82

1989

BOMBAY

DELHI

MADRAS

BANGALORE

BHOPAL

BARSHI

18

(b) FEMALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

1978-82

USA (CONNECTICUT) BLACK

1978

WHITE

BRAZIL (SAO PAULO)

UK (OXFORD)

1979-82

1977-81

1978-82

1989

AAR*

TR*

2.7

1.7

4.4

3.0

1.3

0.5

2.8

0.8

0.7

0.7

0.3

0.3

FINLAND

SWEDEN

INDIA

DELHI

BOMBAY

BANGALORE

BHOPAL

MADRAS

BARSHI

1.8

1.3

0.7

0.5

0.3

0.0

4.0

1.8

1.6

0.0

0.5

0.0

* World Population

Source : Cancer Incidence In Five Continents, Vol. V, 1987. NCRP Data, 1989

The rates in other centres are: Bangalore (4.1), Madras (5.5), Bhopal (2.9) and Barshi (1.3). While in females,

laryngeal cancer age-adjusted incidence rates are very low in all the centres (vary between 0.0 and 1.8 per 100,000).

International comparisons are done in Table 2.9.3.1 for selected countries.The highest incidence rate of

laryngeal cancer world wide have been reported from Sao Paulo (Brazil) in males (Males - 17.8 and Females-1.3

per 100,000) and the lowest rate reported for European populatins in Sweden (Males - 2.8, Females - 0.3).

Jayant et al. (1977) estimated the proportion of cases of laryngeal cancer in Bombay that could be attributed

to chewing tobacco quid and/or smoking. The attributable risk for these two exposures combined was 78%; 28% of

the cases occurred in chewers who were nonsmokers, 38% in smokers who did not chew and 34% in cases who

admitted to both habits. The smokers mostly smoked bidis and the chewers used pan with betel nut, tobacco and

lime. Only 11 % of the cases were nonchewers and nonsmokers compared to 46% of the controls.

2.9.3.2

Cancer of the Trachea, Bronchus & Lung (ICD.9 :162)

Cancer of the lung is of epidemiological interest because of the wide spread geographical and racial variations

observed and steadily increasing incidence and mortality noted in the West. This increase has so far been noticed

particularly in men, but recently women have also begun to present a similar rising trend.

Age-adjusted and truncated incidence rates of lung cancer are much lower in I ndia than the corresponding rates

reported world wide by other countries in Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (VoLV, 1987). Age-adjusted incidence

is higher in the male population : Bombay (14.6), Bhopal (14.1), Delhi (11.9), Madras (11.1), and Bangalore (8.6).

Lung cancer is in the first rank in Bombay, Delhi and Bhopal, but it is not in the first eight ranking sites in the Barshi.

While in Indian women, incidence is low (ranges between 1.7 and 3.7 per 100,000).

The highest rates for cancer of the bronchus and trachea in people of European stock are 100.4 in males in

western Scotland and 33.3 among white females in San Francisco (Bay Area); the lowest rates are found in Iceland

in males (24.7) and in Doubs, France, in females (2.8), indicating a potential for prevention of 75% in males in western

Scotland, and 92% in females in San Francisco (Tomatis et al., 1990). Theoverall incidence of the disease is much

higher in the industrialised countries.

A large number of epidemiological studies in the West has shown that there is a progressive and absolute risk

in its incidence which has occurred over the past few decades and that it is clearly linked to cigarette smoking and

environmental pollution.

The association of cigarette smoking with lung cancer has now been universally accepted. The U.S. Surgeon

General’s Advisory Committee concluded that cigarette smoking is causally related to lung cancer in men and that

its effect far outweighs all other probable etiological factors. The risk increases with the duration of smoking habit

19

and the number of cigarettes smoked daily. A heavy smoker (more than 50 cigarette per day) runs a 20 times higher

risk of developing lung cancer, than a non- smoker. The increasing incidence of lung cancer in women in the West

is clearly linked with the steep increase registered in cigarette smoking by women during the sixties.

Many specific occupations and occupational exposures have been associated with elavated risks for lung

cancer, and in a number of cases the link has been clearly established to be causal. Clearly identified occupational

lung carcinogens are asbestos, coal-tars and soots, arsenic and arsenic compounds, nickel compounds, mustard

gas and radon. Increased risk for lung cancer have also been found to be causally associated with occupational

exposure in aluminium production, in coal gasification and coal production, in iron and steel founding etc. (IARC,

1987).

TABLE 2.9.3.2: INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF AGE-ADJUSTED

(AAR) TRUNCATED (TR)(35-64 YEARS) INCIDENCE RATE PER 100,000.

TRACHEA, BRONCHUS & LUNG (ICD.9:162)

MALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1979-82

1977-81

1979-82

1978-82

1978-82

UK (WEST SCOTLAND)

FINLAND

UK (OXFORD)

USA (BAY AREA) WHITE

USA (CONNECTICUT) WHITE

BLACK

COLUMBIA (CALI)

INDIA

BOMBAY

100.4

74.2

68.8

65.8

64.3

120.7

93.2

68.1

84.0

81.1

89.8

19.5

140.1

25.5

14.6

14.1

11.9

11.1

8.6

2.0

24.7

24.5

233

23.2

13.2

3.9

1977-81

1989

BHOPAL

DELHI

MADRAS

BANGALORE

BARSHI

FEMALES

YEAR STUDIED

REGISTRY

AAR*

TR*

1978-82

1979-82

1978-82

USA (BAY AREA) WHITE

UK (WEST SCOTLAND)

USA (CONNECTICUT) WHITE

BLACK

UK (OXFORD)

33.3

28.6

25.3

21.9

19.5

FINLAND

COLUMBIA (CALI)

7.0

5.4

54.4

46.3

41.5

41.1

25.6

10.0

9.5

3.7

3.2

2.2

1.7

1.6

0.0

5.3

6.3

4.5

4.5

4.1

0.0

1979-82

1977-81

1972-76

1989

INDIA

BOMBAY

BHOPAL

DELHI

MADRAS

BANGALORE

BARSHI

* World Population

Source : Cancer Incidence In Five Continents, Vol. V.1987.

20

TABLE 2.10.1 : TRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

BANGALORE*

SEX: MALES

YEAR : 1982-1989

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

0.2

Lip

141

Tongue

4.5

142

Salivary Gland

0.4

143-145i Mouth

4.0

146

Oropharynx

2.2

147

Nasopharynx

0.9

148

Hypopharynx

4.9

149

Pharynx Uns

0.4

150

Oesophagus

8.4

151

Stomach

11.0

152

Small Intestine

0.0

153

Colon

2.0

154

Rectum

3.0

155

Liver

4.0

156

Gallbladder

0.0

157

Pancreas

0.7

158

Peritoneum

1.0

160

Nose Etc

0.2

161

Larynx

4.5

162

Lung

5.3

163

Pleura

0.7

164

Other Thoracic

0.4

170

Bone

1.0

171

Connective Tissue 1.5

i /z

Skin Melanoma

0.5

173

Skin Other

2.7

175

Breast

0.3

185

Prostate

4.1

186

Testis

0.7

187

Penis Etc

2.3

188

Bladder

3.3

189

Kidney

1.2

190

Eye

0.7

191-192 Brain-Ns

1.8

193

Thyroid Gland

0.9

194

Endocrine Other

0.2

201

Hodgkins Disease 1.5

200-202 Non-Hodg Lymphoma 3.1

203

Mult Myeloma

0.7

204

Leuk Lymphoid

0.9

205

Leuk Myeloid

1.0

206

Leuk Monocytic

0.0

207

Leuk Other

0.0

208

Leuk Uns

0.6

Primary Unk

12.5

0.0

4.0

0.4

4.9

2.0

0.4

6.0

0.4

6.3

10.9

0.2

2.0

2.3

1.5

0.3

1.2

1.0

0.2

4.9

8.8

0.4

0.2

1.6

1.2

0.7

0.9

0.6

3.2

0.3

2.8

4.5

0.8

0.1

2.6

0.4

0.4

' 1.4

3.1

0.5

0.7

1.0

0.0

0.3

0.5

6.6

0.0

3.0

0.0

3.6

2.3

0.7

6.6

0.8

8.2

10.5

0.0

2.4

2.3

3.7 ■

0.2

0.7

0.5

0.5

4.0

9.2

0.2

0.2

1.1

1.3

0.0

1.7

0.3

4.2

0.9

2.0

2.9

1.0

0.1

1.1

0.4

0.1

1.0

3.4

1.1

1.1

1.2

0.0

0.1

0.4

5.5

0.0

2.6

0.3

4.5

1.3

0.7

6.0

0.7

7.3

12.1

0.1

2.6

3.4

3.6

0.3

0.7

1.1

0.8

3.7

11.8

0.5

0.2

1.1

0.8

0.0

0.9

0.3

5.6

0.7

2.3

2.8

1.8

0.2

1.7

1.1

0.0

1.4

2.9

0.8

1.0

0.8

0.2

0.3

0.3

7.6

0.1

2.8

0.4

3.1

1.9

0.4

5.2

0.3

7.6

9.9

0.4

2.4

3.5

2.8

0.7

0.8

0.5

0.6

4.1

10.0

0.5

0.1

0.5

0.3

0.5

1.4

0.5

5.0

1.0

1.0

3.0

1.9

0.3

3.0

1.7

0.0

1.6

3.2

1.0

1.2

1.0

0.0

0.0

0.5

10.4

0.0

4.5

0.5

5.4

1.9

0.3

7.5

0.7

11.1

9.3

0.0

2.1

3.4

3.4

0.7

1.4

0.7

0.9

4.8

10.8

0.3

0.2

0.5

1.6

0.1

1.4

0.5

5.5

0.7

1.4

3.1

1.5

0.1

2.2

0.6

0.1

1.5

1.7

0.9

0.8

1.5

0.0

0.0

0.5

14.3

0.1

2.9

0.7

3.4

2.5

0.2

7.3

0.6

9.9

13.6

0.2

2.6

3.6

2.8

0.4

2.3

0.7

0.6

4.4

11.7

0.5

0.1

1.3

0.6

0.0

2.5

0.4

4.9

0.3

2.2

3.3

0.6

0.1

3.5

1.2

0.0

1.2

4.2

0.3

1.2

0.9

0.0

0.0

0.2

14.7

0.4

4.7

0.8

3.0

1.9

0.6

5.9

0.2

9.4

9.5

0.0

2.7

4.3

3.2

0.5

1.7

0.9

0.3

4.1

8.6

0.6

0.1

1.3

0.6

0.1

2.0

0.2

7.1

0.6

1.8

2.7

1.1

0.2

4.0

0.9

0.1

2.4

3.1

0.6

1.6

2.3

0.1

0.0

0.7

15.2

92.5

90.6

98.7

97.0

110.7

114.6

112.2

ICD9

SITE

ALL SITES

100.2

* Incidence Rate Per 100,000

30

TABLE 2.10.2 :TRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

BANGALORE*

SEX: FEMALES

YEAR: 1982-1989

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

0.1

Lip

141

Tongue

1.1

142

Salivary Gland

0.2

143-145 Mouth

13.4

146

Oropharynx

0.4

147

Nasopharynx

0.1

148

Hypopharynx

1.3

149

Pharynx Uns

0.3

150

Oesophagus

7.1

151

Stomach

6.0

152

Small Intestine

0.1

153

Colon

1.5

154

Rectum

2.6

155

Liver

1.4

156

Gallbladder

0.0

157

Pancreas

0.4

158

Peritoneum

1.6

160

Nose Etc

0.7

161

Larynx

1.3

LUNG

162

1.4

163

Pleura

0.4

164

Other Thoracic

0.1

170

Bone

1.2

171

Connective Tissue 1.1

172

Skin Melanoma

0.5

173

Skin Other

1.9

174

Breast

17.3

179

Uterus Uns

0.2

180

Cervix Uteri

35.6

181

Placenta

0.2

182

Corpus Uteri

1.8

183

Ovary etc

5.0

184

Other Fem Genital 2.3

188

Bladder

0.7

189

Kidney

1.7

190

Eye

0.3

191- 192 Brain-Ns

1.2

193

Thyroid Gland

2.5

194

Endocrine Other

0.0

201

Hodgkins Disease 0.4

200-202 Non-hodg Lymphoma 1.4

203

Mult Myeloma

0.2

204

Leuk Lymphoid

0.5

205

Leuk Myeloid

0.9

206

Leuk Monocytic

0.2

207

Leuk Other

0.0

208

Leuk Uns

0.3

Primary Unk

10.0

0.1

1.4

0.5

9.6

0.4

0.5

1.7

0.4

7.3

6.0

0.2

1.1

1.9

1.2

0.6

0.4

0.7

0.4

0.8

1.7

0.4

0.0

0.4

0.7

0.4

2.4

17.6

0.2

33.7

0.2

2.2

4.3

1.2

0.4

0.9

0.2

1.0

2.7

0.2

0.3

1.6

0.1

0.3

1.0

0.0

0.3

0.7

6.1

0.3

1.0

0.6

10.2

0.3

0.3

1.6

0.0

9.5

5.7

0.4

1.2

2.8

0.6

0.3

0.3

0.7

0.1

0.6

2.2

0.4

0.0

1.3

0.9

0.4

2.1

18.5

1.0

31.0

0.0

1.6

5.5

1.2

0.5

0.4

0.0

1.1

3.4

0.1

0.3

1.7

0.7

0.5

0.9

0.0

0.0

0.1

3.9

0.1

1.2

0.2

9.2

0.2

0.0

1.2

0.6

7.2

7.0

0.3

1.5

2.5

0.8

0.4

1.3

0.1

0.7

0.9

1.7

0.4

0.1

0.2

0.7

0.3

1.2

17.8

0.4

29.5

0.2

1.0

3.1

0.8

0.6

0.6

0.2

1.6

3.1

0.0

0.9

1.0

0.6

0.8

1.4

0.0

0.0

0.0

5.1

0.1

0.8

0.3

10.4

0.4

0.1

0.6

0.5

10.1

4.7

0.1

2.2

3.2

0.9

0.2

0.5

0.7

0.7

0.7

1.4

0.3

0.0

0.6

0.8

0.2

1.3

15.9

0.5

28.7

0.4

1.3

5.3

1.5

0.2

0.8

0.1

1.4

1.7

0.0

0.4

2.5

0.6

0.6

1.3

0.0

0.0

0.3

. 10.5

0.1

1.1

0.9

8.9

0.1

0.1

1.2

0.2

9.8

5.2

0.1

2.6

3.0

1.1

0.8

1.0

0.2

0.2

0.6

2.3

0.3

0.1

0.7

1.0

0.1

0.7

20.9

0.8

32.4

0.1

2.0

5.9

1.5

0.7

1.1

0.2

1.8

3.0

0.1

0.7

2.0

1.0

0.4

1.5

0.0

0.1

0.4

10.4

0.2

1.2

0.2

11.2

0.5

0.3

1.5

0.3

8.1

6.3

0.1

2.4

3.6

1.5

0.7

0.7

0.7

0.5

0.5

1.5

0.2

0.1

0.8

0.5

0.2

2.5

20.4

0.1

32.2

0.0

0.9

4.7

1.9

0.8

0.5

0.4

1.3

3.4

0.1

1.0

1.3

0.5

0.5

2.1

0.0

0.1

0.6

12.9

0.1

1.0

0.5

11.1

0.5

0.4

1.2

0.1

10.2

4.3

0.0

2.3

2.2

1.0

0.8

1.0

0.5

0.4

0.7

1.6

0.5

0.1

0.9

0.3

0.1

1.6

22.3

0.6

26.4

0.0

2.0

4.7

1.4

0.8

0.4

0.0

1.7

3.2

0.1

0.7

2.1

0.7

0.6

2.0

0.0

0.0

0.9

10.5

129.0

116.2

116.3

108.7

115.9

129.5

132.3

124.7

ICD9

SITE

ALL SITES

* Incidence Rate Per 100,000

31

TABLE 2.10.3 rTRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

BOMBAY*

SEX: MALES

YEAR: 1982-1989

SITE

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

Lip

141

Tongue

142

Salivary Gland

143-145 Mouth

146

Oropharynx

147

Nasopharynx

148

Hypopharynx

149

Pharynx Uns

150

Oesophagus

151

Stomach

152

Small Intestine

153

Colon

154

Rectum

155

Liver

156

Gallbladder

157

Pancreas

158

Peritoneum

160

Nose etc

161

Larynx

162

Lung

0.3

7.1

0.6

5.7

3.3

0.9

9.5

2.6

11.2

7.4

0.2

2.5

4.0

3.8

0.7

2.2

0.5

1.1

7.0

13.7

0.4

7.2

0.5

5.9

2.7

1.1

7.7

2.3

9.9

7.4

0.2

2.9

3.1

3.3

0.6

1.7

0.1

0.8

8.9

14.7

0.3

7.8

0.4

5.0

3.8

0.5

8.6

1.6

12.1

7.1

0.3

2.5

3.5

3.3

1.1

2.2

0.2

1.1

8.1

13.4

0.3

7.9

0.4

6.9

3.6

0.7

8.1

2.4

11.6

7.3

0.2

2.6

3.2

3.3

1.2

3.2

0.3

1.0

7.8

14.2

0.4

7.8

0.5

5.9

2.7

0.8

8.0

2.6

11.4

7.9

0.5

3.5

2.9

3.7

1.0

2.7

0.3

0.9

9.8

13.1

0.3

6.3

0.5

5.6

3.3

0.5

8.3

2.1

11.8

6.8

0.2

4.5

3.2

3.2

1.1

2.6

0.4

1.1

9.9

14.8

0.2

5.9

0.5

6.1

3.5

0.6

9.4

1.8

11.4

7.7

0.2

3.0

3.3

3.5

1.2

2.3

0.6

0.7

8.1

14.0

0.3

6.5

0.4

5.8

3.2

0.6

8.2

1.8

11.5

7.0

0.5

4.0

3.9

3.5

1.6

2.5

0.3

1.4

8.8

14.6

163

Pleura

164

O ther Thoracic

170

Bone

171

Connective Tissue

172

Skin Melanoma

173

Skin Other

175

Breast

185

Prostate

186

Testis

187

Penis etc

188

Bladder

189

Kidney

190

Eye

191-192 Brain-Ns

193

Thyroid Gland

194

Endocrine Other

201

Hodgkins Disease

200-202 Non-hodg Lymphoma

203

Mult Myeloma

204

Leuk Lymphoid

205

Leuk Myeloid

206

Leuk Monocytic

207

Leuk Other

208

Leuk Uns

Primary Unk

0.1

0.1

0.9

1.0

0.3

1.9

0.2

5.4

0.8

2.2

3.4

1.1

0.2

1.8

0.6

0.1

1.1

2.6

1.2

1.7

1.5

0.1

0.0

0.4

6.6

0.0

0.0

0.8

1.2

0.2

1.6

0.1

5.7

1.0

1.7

3.1

1.5

0.5

1.8

0.9

0.1

1.3

3.4

0.9

1.1

1.4

0.0

0.1

0.5

6.8

0.1

0.1

0.9

1.8

0.4

1.4

0.5

6.9

1.1

2.1

4.0

1.5

0.2

2.8

0.8

0.1

1.0

3.3

0.7

2.2

2.1

0.0

0.0

0.6

6.8

0.3

0.1

0.9

1.1

0.3

2.6

0.3

8.3

0.9

1.7

3.2

1.1

0.3

2.7

0.6

0.1

1.4

4.1

0.9

1.7

1.9

0.0

0.0

0.5

8.5

0.5

0.1

0.9

1.4

0.2

2.1

0.3

6.1

1.1

2.2

3.8

. 1.5

0.2

2.0

1.0

0.2

1.2

3.6

0.8

1.5

1.9

0.0

0.0

0.58.9

0.5

0.2

0.9

1.3

0.1

1.9

0.6

7.3

1.0

2.0

4.1

1.5

0.3

2.6

0.7

0.2

1.0

4.4

0.9

1.4

1.7

0.0

0.1

0.6

9.0

0.5

0.1

0.8

1.3

0.5

2.0

0.4

8.2

0.9

2.0

4.5

1.6

0.1

2.8

0.7

0.3

1.1

3.1

0.8

1.7

1.7

0.0

0.1

0.4

10.0

0.2

0.1

0.8

1.5

0.3

1.3

0.3

6.9

0.9

1.6

4.2

1.4

0.4

3.1

0.7

0.2

1.2

4.0

1.3

1.6

1.9

0.0

0.2

0.3

9.7

119.9

116.5

123.9

129.5

128.5

130.4

129.6

130.4

ICD9

ALL SITES

* Incidence Rate Per 100,000

32

TABLE 2.10.4 iTRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

BOMBAY*

SEX: FEMALES

YEAR: 1982-1989

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

0.1

Lip

141

Tongue

2.9

142

Salivary Gland

0.7

143-145 Mouth

4.5

146

Oropharynx

0.5

147

Nasopharynx

0.5

148

Hypopharynx

2.1

149

0.4

Pharynx Uns

150

Oesophagus

8.4

151

Stomach

5.4

152

Small Intestine

0.5

153

Colon

2.3

154

Rectum

2.4

155

Liver

2.7

156

Gallbladder

1.0

157

Pancreas

1.4

158

Peritoneum

0.2

160

Nose Etc

0.8

161

Larynx

1.2

162

Lung

3.3

163

Pleura

0.1

164

Other Thoracic

0.1

170

Bone

0.7

171

Connective Tissue 1.0

172

Skin Melanoma

0.1

173

Skin Other

1.3

174

Breast

21.4

179

Uterus Uns

1.5

180

Cervix Uteri

18.5

181

Placenta

0.3

182

Corpus Uteri

2.1

183

Ovary etc

5.9

184

Other Fem Genital 1.6

188

Bladder

0.7

189

Kidney

0.5

190

Eye

0.2

191-192 Brain-Ns

1.3

193

Thyroid Gland

1.5

194

Endocrine Other

0.0

201

Hodgkins Disease 0.6

200-202 Non-hodg Lymphoma 1.8

203

Mult Myeloma

0.6

204

Leuk Lymphoid

1.0

205

Leuk Myeloid

1.4

206

Leuk Monocytic

0.1

207

Leuk Other

0.1

208

Leuk Uns

0.4

Primary Unk

4.9

0.4

2.4

0.3

4.2

0.7

0.4

1.3

0.5

7.4

3.7

0.3

2.7

2.3

1.5

1.6

1.3

0.3

0.6

2.0

3.2

0.0

0.0

0.8

0.8

0.0

0.9

21.6

1.2

18.5

0.2

2.2

6.3

1.2

1.0

0.7

0.3

1.2

1.3

0.1

0.5

2.0

0.8

0.7

1.3

0.0

0.0

0.5

4.8

0.2

2.0

0.4

3.9

0.3

0.2

2.0

0.9

8.4

3.9

0.3

2.8

2.3

1.4

1.4

. 1.2

0.5

1.0

1.3

4.1

0.0

0.0

0.9

0.7

0.2

1.2

23.6

1.2

19.6

0.2

2.1

6.2

1.4

0.9

0.7

0.1

1.5

1.4

0.2

0.7

2.4

1.0

0.8

1.7

0.0

0.1

0.3

6.7

0.2

2.5

0.3

4.4

1.0

0.2

2.6

0.7

8.9

4.2

0.2

2.5

2.5

2.2

1.9

1.9

0.6

0.9

1.4

2.7

0.3

0.1

0.6

1.1

0.5

2.0

26.4

1.4

19.3

0.3

2.0

6.7

1.1

1.3

0.8

0.1

1.7

1.5

0.2

0.7

2.0

1.1

0.9

1.4

0.1

0.0

0.4

7.1

0.3

3.2

0.5

4.5

0.6

0.3

1.9

0.5

8.3

4.9

0.2

2.4

2.6

2.5

1.5

1.1

0.5

0.9

1.6

2.0

0.4

0.1

0.8

0.7

0.2

1.6

26.7

1.7

19.9

0.1

2.7

6.0

1.2

0.9

0.7

0.1

1.6

1.8

0.1

0.3

2.3

0.8

1.3

1.4

0.0

0.0

0.4

6.7

0.3

2.5

0.3

4.4

0.7

0.1

1.8

0.9

8.8

4.8

0.2

2.8

2.8

1.7

2.0

2.0

0.4

0.7

1.6

2.9

0.1

0.0

0.6

0.6

0.1

1.7

24.2

1.1

19.1

0.2

2.4

7.3

1.7

0.7

0.6

0.3

2.3

1.7

0.0

0.6

2.8

0.8

0.9

1.5

0.0

0.0

0.3

5.4

0.3

2.2

0.3

4.7

0.6

0.3

2.2

0.6

8.0

4.3

0.3

2.7

2.3

1.9

2.1

1.9

0.3

0.3

1.5

3.6

0.2

0.1

0.6

0.9

0.2

1.1

25.0

1.3

21.0

0.2

2.2

7.6

1.6

1.3

0.7

0.4

1.7

2.0

0.1

0.5

2.6

0.8

1.1

1.4

0.0

0.0

0.5

6.9

0.2

1.9

0.3

3.9

0.6

0.2

1.5

0.9

8.2

3.4

0.3

2.4

2.6

1.8

2.3

1.8

0.6

1.0

1.3

3.7

0.2

0.1

0.7

0.9

0.3

1.2

26.1

1.5

19.4

0.1

2.2

7.0

1.7

1.3

0.8

0.2

2.3

2.0

0.1

0.7

3.0

0.6

1.1

1.3

0.0

0.1

0.4

6.1

106.3

113.8

122.9

120.9

118.8

122.7

120.4

ICD9

SITE

ALL SITES

111.2

* Incidence Rate Per 100,000

33

TABLE 2.10.5 :TRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

MADRAS*

SEX: MALES

YEAR: 1982-1989

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

0.4

Lip

141

Tongue

3.8

142

Salivary Gland

0.3

143-145 Mouth

6.7

146

Oropharynx

1.8

147

Nasopharynx

0.7

148

Hypopharynx

3.7

149

0.6

Pharynx Uns

150

Oesophagus

6.3

151

Stomach

12.1

152

Small Intestine

0.3

153

Colon

1.5

154

Rectum

2.7

155

Liver

1.7

156

Gallbladder

0.1

157

Pancreas

1.0

158

Peritoneum

0.7

160

Nose Etc

0.6

161

Larynx

4.2

162

Lung

5.1

163

Pleura

0.0

164

Other Thoracic

0.0

170

Bone

0.9

171

Connective Tissue 0.6

172

Skin Melanoma

0.2

173

Skin Other

0.9

175

Breast

0.3

185

Prostate

2.8

186

Testis

0.6

187

Penis etc

2.9

Bladder

188

1.8

189

Kidney

1.7

190

Eye

0.5

191-192 Brain-Ns

1.3

193

Thyroid Gland

0.7

194

Endocrine Other

0.2

201

Hodgkins Disease 2.3

200-202 Non-hodg Lymphoma 2.3

203

Mult Myeloma

0.4

204

Leuk Lymphoid

1.2

205

Leuk Myeloid

1.4

206

Leuk Monocytic

0.3

Leuk Other

207

0.0

Leuk Uns

208

0.6

Primary Unk

3.4

0.2

3.5

0.8

6.1

1.7

0.6

5.4

1.0

6.1

14.2

0.5

2.1

2.1

1.6

0.4

1.0

0.3

1.1

3.9

7.3

0.1

0.1

1.1

1.1

0.6

1.0

0.4

2.1

0.3

3.7

0.8

0.7

0.4

2.3

0.9

0.0

1.8

1.8

0.5

1.0

0.9

0.0

0.0

0.5

6.1

0.1

4.0

0.7

5.6

1.4

0.9

4.2

0.4

7.6

13.8

0.2

0.7

2.6

2.5

0.3

1.1

0.5

0.7

4.8

8.5

0.0

0.0

1.0

1.1

0.3

1.3

0.3

1.3

0.5

3.0

1.9

0.6

0.1

2.8

0.5

0.1

1.3

2.0

0.8

1.3

1.1

0.0

0.0

0.2

5.5

0.5

5.5

0.7

6.7

1.1

0.8

3.8

0.4

7.7

15.7

0.1

1.7

2.1

3.1

0.4

0.9

0.4

0.7

4.6

8.0

0.2

0.1

0.7

0.6

0.2

1.7

0.1

1.5

0.9

1.9

1.4

0.9

0.3

1.7

0.8

0.3

1.4

3.2

1.0

1.4

1.1

0.0

0.0

0.3

5.4

0.1

5.0

0.4

7.4

2.0

0.8

5.9

1.2

7.2

17 1

0.0

1.7

2.6

2.1

0.3

1.2

0.4

1.2

4.3

9.9

0.1

0.2

0.1

0.9

0.3

1.4

0.5

3.1

0.8

2.5

1.8

1.7

0.6

2.1

0.6

0.0

1.7

2.7

0.6

1.1

1.2

0.0

0.0

0.1

6.4

0.5

5.1

0.7

8.1

2.2

0.4

6.6

0.9

9.5

14.3

0.2

1.3

2.5

2.4

0.9

1.5

0.3

0.6

4.6

8.8

0.1

0.1

0.7

0.9

0.4

1.4

0.1

2.6

0.5

2.6

3.C

1.5

0.4

2.4

0.7

0.1

1.7

3.4

0.5

1.0

1.4

0.0

0.0

0.6

6.6

0.5

8.2

0.9

9.8

2.9

1.4

7.8

1.2

10.4

15.1

0.2

1.9

3.7

3.9

0.5

0.3

1.6

5.5

11.4

0.4

0.0

1.4

1.5

0.1

1.5

0.1

2.9

0.7

4.0

2.3

0.4

0.9

2.7

0.8

0.2

1.6

3.5

0.9

1.4

0.9

0.0

0.0

0.2

8.5

0.6

5.3

0.4

7.3

1.9

0.6

6.5

1.0

10.2

16.5

0.1

2.0

4.5

1.9

0.3

1.4

0.1

0.6

5.5

11.1

0.2

0.2

0.9

1.0

0.3

2.2

0.7

3.6

1.1

2.8

3.8

0.9

0.3

1.8

0.9

0.1

1.7

3.9

0.5

1.5

1.4

0.2

0.0

0.3

10.4

88.7

87.6

92.2

101.3

104.4

125.2

118.5

ICD9

SITE

ALL SITES

81.6

Incidence Rate Per 100,000

to

TABLE 2.10.5 .'TRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

MADRAS*

SEX: MALES

YEAR : 1982-1989

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

0.4

Lip

141

Tongue

3.8

142

Salivary Gland

0.3

143-145 Mouth

6.7

146

Oropharynx

1.8

147

Nasopharynx

0.7

148

Hypopharynx

3.7

149

Pharynx Uns

0.6

150

Oesophagus

6.3

151

Stomach

12.1

152

Small Intestine

0.3

153

Colon

1.5

154

Rectum

2.7

155

Liver

1.7

156

Gallbladder

0.1

157

Pancreas

1.0

158

Peritoneum

0.7

160

Nose Etc

0.6

161

Larynx

4.2

162

Lung

5.1

163

Pleura

0.0

164

Other Thoracic

0.0

170

Bone

0.9

171

Connective Tissue 0.6

172

Skin Melanoma

0.2

173

Skin Other

0.9

175

Breast

0.3

185

Prostate

2.8

186

Testis

0.6

187

Penis etc

2.9

188

Bladder

1.8

189

Kidney

1.7

190

Eye

0.5

191-192 Brain-Ns

1.3

193

Thyroid Gland

0.7

194

Endocrine Other

0.2

201

Hodgkins Disease 2.3

200-202 Non-hodg Lymphoma 2.3

203

Mult Myeloma

0.4

204

Leuk Lymphoid

1.2

205

Leuk Myeloid

1.4

206

Leuk Monocytic

0.3

207

Leuk Other

0.0

208

Leuk Uns

0.6

Primary Unk

3.4

0.2

3.5

0.8

6.1

1.7

0.6

5.4

1.0

6.1

14.2

0.5

2.1

2.1

1.6

0.4

1.0

0.3

1.1

3.9

7.3

0.1

0.1

1.1

1.1

0.6

1.0

0.4

2.1

0.3

3.7

0.8

0.7

0.4

2.3

0.9

0.0

1.8

1.8

0.5

1.0

0.9

0.0

0.0

0.5

6.1

0.1

4.0

0.7

5.6

1.4

0.9

4.2

0.4

7.6

13.8

0.2

0.7

2.6

2.5

0.3

1.1

0.5

0.7

4.8

8.5

0.0

0.0

1.0

1.1

0.3

1.3

0.3

1.3

0.5

3.0

1.9

0.6

0.1

2.8

0.5

0.1

1.3

2.0

0.8

1.3

1.1

0.0

0.0

0.2

5.5

0.5

5.5

0.7

6.7

1.1

0.8

3.8

0.4

7.7

15.7

0.1

1.7

2.1

3.1

0.4

0.9

0.4

0.7

4.6

8.0

0.2

0.1

0.7

0.6

0.2

1.7

0.1

1.5

0.9

1.9

1.4

0.9

0.3

1.7

0.8

0.3

1.4

3.2

1.0

1.4

1.1

0.0

0.0

0.3

5.4

0.1

5.0

0.4

7.4

2.0

0.8

5.9

1.2

7.2

17.1

0.0

1.7

2.6

2.1

0.3

1.2

0.4

1.2

4.3

9.9

0.1

0.2

0.1

0.9

0.3

1.4

0.5

3.1

0.8

2.5

1.8

1.7

0.6

2.1

0.6

0.0

1.7

2.7

0.6

1.1

1.2

0.0

0.0

0.1

6.4

0.5

5.1

0.7

8.1

2.2

0.4

6.6

0.9

9.5

14.3

0.2

1.3

2.5

2.4

0.9

1.5

0.3

0.6

4.6

8.8

0.1

0.1

0.7

0.9

0.4

1.4

0.1

2.6

0.5

2.6

3.C

1.5

0.4

2.4

0.7

0.1

1.7

3.4

0.5

1.0

1.4

0.0

0.0

0.6

6.6

0.5

8.2

0.9

9.8

2.9

1.4

7.8

1.2

10.4

15.1

0.2

1.9

3.7

3.9

0.5

0.3

1.6

5.5

11.4

0.4

0.0

1.4

1.5

0.1

1.5

0.1

2.9

0.7

4.0

2.3

0.4

0.9

2.7

0.8

0.2

1.6

3.5

0.9

1.4

0.9

0.0

0.0

0.2

8.5

0.6

5.3

0.4

7.3

1.9

0.6

6.5

1.0

10.2

16.5

0.1

2.0

4.5

1.9

0.3

1.4

0.1

0.6

5.5

11.1

0.2

0.2

0.9

1.0

0.3

2.2

0.7

3.6

1.1

2.8

3.8

0.9

0.3

1.8

0.9

0.1

1.7

3.9

0.5

1.5

1.4

0.2

0.0

0.3

10.4

88.7

87.6

92.2

101.3

104.4

125.2

118.5

ICD9

SITE

ALL SITES

81.6

* Incidence Rate Per 100,000

34

to

TABLE 2.10.6 : TRENDS IN AGE-ADJUSTED (WORLD POPULATION) CANCER INCIDENCE RATES

MADRAS*

SEX: FEMALES

YEAR: 1982-1989

1982

1983

YEAR OF DIAGNOSIS

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

140

0.3

Lip

141

Tongue

1.7

142

Salivary Gland

0.2

143-145 Mouth

8.6

146

0.8

Oropharynx

147

Nasopharynx

0.2

148

Hypopharynx

1.1

149

Pharynx Uns

0.1

150

Oesophagus

3.3

151

Stomach

5.9

152

Small Intestine

0.1

153

Colon

0.5

154

Rectum

1.3

155

Liver

0.6

156

Gallbladder

0.2

157

Pancreas

0.3

158

Peritoneum

0.2

160

Nose Etc

0.3

161

Larynx

0.5

162

Lung

1.1

163

Pleura

0.0

164

Other Thoracic

0.1

170

Bone

0.7

171

Connective Tissue 0.9

172