WHICH SILK ROUTE THIS

Item

- Title

- WHICH SILK ROUTE THIS

- extracted text

-

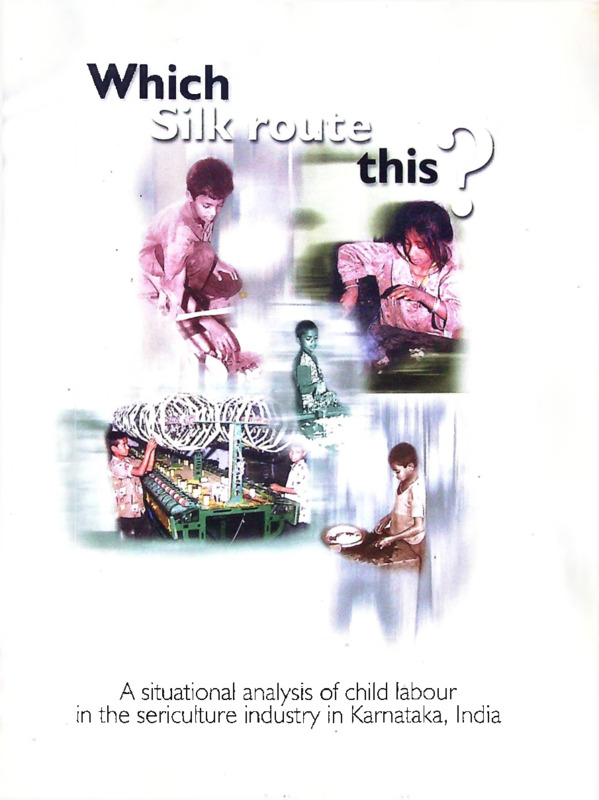

Which

A situational analysis of child labour

in the sericulture industry in Karnataka, India

SOCHARA

Community Health

Library and Information Centre (CLIC)

Community Health Cell

85/2, 1st Main, Maruthi Nagar,

Madiwala, Bengaluru - 560 068.

Tel 1080-25531518

email: clic@sochara.org I chc@sochara.org

www.sochara.org

Which Silk route this?

A situational analysis of

Child Labour in

the Sericulture Industry

MAYA

Movement for‘Alter natives and Youth Awareness

- a Development and Training Organisation

Summary

This report addresses issues of the growing

incidence of child labour in the sericulture

sector in Channapatna and Ramanagaram

talukas of Bangalore Rural district.

Karnataka - the largest silk producing state

in the country - continues to employ

children in the sericulture industry. The

employment of children, ostensibly to

provide employment to the poor families,

has in fact benefitted only the silk reelers

and filature unit owners and not the families

or the children employed. Further, it has

also been observed that the sericulture

industry acts as an incentive for parents to

send their children to work rather than to

school. The Government, on its part, has

failed to take any definitive action to prevent

children from being employed. On the

contrary, there has been an entrenchment

of child labour in this sector, which includes

designing child-sized reeling machines that

children can work on. More importantly,

the sericulture sector is an example of

gross violation of children’s right to

participation, survival, protection and

development.

Consequently, there is an urgent need to

redefine

our understanding of

‘development’ and highlight the ways in

which social underdevelopment is

sustained.

The development experience in our country reflects the extent to which economic

growth per se does not lead to improvement in the socio-economic conditions of

the people. Processes which speak of improved utilisation of resources and growth

patterns which give a boost to the economy have often led to increased marginalisation

of people, especially children and women, in the long run. A critical area of concern

in this regard should be to draw our attention to the thrust of development policies

and agendas. This should largely reflect people’s attitudes and responses both to an

immediate and a long-term macro-economic perspective and the social implication

Child labour of these policies on their lives. Progress, if viewed from an economic and

exists not

because of

development pathway appropriate to the conditions existing in a given socio

cultural milieu, will ensure a balance between economic development and the

quality of life of people. The political priorities which maintain the social and

poverty of economic order and the development agenda have ignored and pushed the poor,

income but

mainly

because of

and more so their children, to the edge of life.

In this regard, the development of sericulture industry in India is a case in point.

Sericulture is said to provide an excellent opportunity for socio-economic progress

in the context of a developing country like India, due to various reasons. First and

factors such

foremost, sericulture is a highly labour-intensive industry. Excluding moriculture

as

(mulberry cultivation) which is a cottage industry, silkworm rearing itself generates

1.5-4.5 person-years of employment per year per hectare of mulberry garden, under

community

rain-fed and irrigated conditions respectively.’ Sericulture and related activities operate

apathy,

on a relatively low amount of fixed capital making it easily affordable even for

parental economically weaker persons to invest. At the lower end, a fixed capital of less than

negligence,

Rs. 2000 on equipment can enable even a landless poor family to take up silkworm

rearing by leasing a plot of mulberry garden and using the premises of the dwelling

hostile school place itself. Similarly, a poor household needs to invest about Rs. 2500 on a charaka

environment

to take up silk reeling.

Hence, sericulture is often promoted by the Government as a low-cost, high-income

scheme. /Xssistancc from the World Bank of almost 400 million rupees has come

into Karnataka for development of the sericulture industry since 1980. The bank

believes that promotion of sericulture will create jobs to alleviate poverty and help

the disadvantaged groups. However, in reality, this has not been achieved even after

two decades. (It is estimated1 that 56.8% of the gross income from the sale of

i

Central Silk Board, Silk in India. 1992

Which Silk route this?

soft-silk fabrics (70g/mtr) goes to the cocoon producers, 16.6% to the trader, 10.7%

to the weaver, 9.1% to the twister and only 6.8% to the reeler2). The recent budget

(2000) of the Karnataka State Govt proposes to promote the sericulture sector as an

income generating activity, especially one in which women can be integrated.

Several development agencies have added to the Government’s promotion of

sericulture, seeing it as a viable regional development scheme and as one in which the

poor can be drawn

into the development

circle.

The flip side of

sericulture being a

cottage industry is

that it depends on

maximum amount of

work to be carried

out

by

children.

Children

are

employed in all stages of the silk processing, making sericulture a child-based industry.

The machines utilised are designed such that children can work on them. In the

sericulture sector, the child at present grows as an ‘exploitable commodity’ - denied

as a human potential who is entided to the fundamental right to exist. This sector has

over the past few decades been witness to a progressive and systematic marginalisation

of the poor. This situation has led to a total decadence of the social and cultural life

of people in this sector wherein, the children find themselves alienated from the

social mainstream. The administrative structures, institutional machinery and attitude

of the State continue to overlook the problems rather than enable people to

comprehend, access and utilise resources for their well-being. However, sericulture

and its processing are an industry that works at the cost of the health, education, and

social opportunities of children. The gross violation of children’s rights with regard

to their health, social life, education and their lost childhood should essentially be a

matter of great concern to policy makers, economists, employers, voluntary

organisations and other community members.

2

2

‘Rcclcr’ in this context refers to the filature unit owners and not the women and children working at the units.

Intervention by the Government and the voluntary sector

The growing incidence of child labour in almost all sectors has necessitated acdon

from various groups - including the government and Non Government Organisations

(NGOs) who have evolved different strategics to address the issue of child labour.

The Government is currcndy sponsoring National Child Labour Projects (NCLP)

throughout the country that seek to rehabilitate working children through non-formal

education and financial provisions for the families. r\ny attempt by the Govt toward

eradicating child labour in these talukas has been limited to establishing residential

....They

schools and hostels for working children (100 children per district), raiding filature

are of the

units, conducting meetings with the employers etc. However, none of this has fulfilled

opinion

the objective of reducing the number of working children in the sericulture sector;

on the contrary, the number of children seems to be increasing with more children

that

dealing

with the

dropping out of school and entering the workforce every year.

The Department of Sericulture and other associated Govt bodies view their role as

being limited to the technical aspects of the industry, research on the silk variety, etc.

issue of They arc of the opinion that dealing with the issue of child labour in the sector would

child

disturb the ‘economy’ of the industry. Prior to the intervention of die World Bank, a

study conducted by the Institute for Socio-Economic Change identified the incidence

labour

of child labour in the sericulture industry as an issue that needed to be addressed and

would

recommended that this aspect be included in the National Sericulture Project.

disturb

the

'economy'

of the

industry.

However, subsequent intervention by cither the Bank, the Swiss Development

Corporation and others has been restricted to conducting studies, analyses, and reports

on the issue. In reality, little has been done by them to improve the condition of the

children and the families toiling in the industry.

The various approaches amongst NGOs to address the issue of child labour can be

broadly classified as rehabilitative and preventive. Although most of these efforts

affect only a small number of children directly, they are effective to some extent, in

creating a climate that makes the employment of children difficult.

Rehabilitative efforts mostly consist of conducting non formal education classes,

enrolling working children into hostels, formal schools or providing vocational training

facilities for them. Many NGOs also attempt prevention through campaigns, working

with parents, and organising children. Although rehabilitation and prevention can be

viewed as separate approaches, some NGOs employ an integrated approach to address

the complex and multi-faceted issue of eradication of child labour. But in the two

talukas of Channapatna and Ramanagaram of Bangalore Rural district, there has

3

been no intervention even by the voluntary sector to mobilise public opinion against

employing children. In the absence of quality schools and relevant education for

children, sending them to work at the filature units has almost become a culture in the

villages and slums in these areas.

MAYA’s3 INTERVENTION

Drawing from observations and experiences, MAYA’s intervention and approach

towards the eradication of child labour is based on the premise that child labour

exists not because of poverty of income but mainly because of factors such as

community apathy, parental negligence, hostile school environment etc MAYA’s

role therefore is primarily to facilitate opportunities where communities are supported

to bring about change through their own effort and initiative rather than as passive

beneficiaries of charity. In this regard, MAYA has been addressing aspects of both

rehabilitation and prevention in its goal of working toward the eradication of child

labour since 1989. The organisation’s multiform approach includes direct work with

small children (aged 0-6 yrs), schoolgoing children and child labourers as well as

working with the immediate environment of the child i.e the family, school, and

community, .

The early childhood programme involves creating an environment in the area that

encourages children to go to school. The local community is supported to initiate

and run playschools where young children are prepared for formal schooling. To

complement the stimulation and learning needs of working and schoolgoing children

through games, cultural activities and other learning exercises, Child Development

Centres are initiated in the areas. Resource materials for these centres arc mobilised

from the local community. MAYA also works with school going children, parents

and the local government schools to reduce drop out rates and ensure that children

receive quality education. Efforts also include direct work with child labourers to

support them to explore viable alternatives such as pre-vocational education and

vocational training. Over the years, MAYA’s experience has shown that communities

have the inherent capacity to deal with issues faced by them and only require

support to perceive such opportunities. Experience has also shown that contrary

to popular belief, poverty of income is not the primary cause of child labour. A

study conducted by MAYA on the impact of wage pattern on the family and the

3

MAYA (Movement for Alternatives and Youth Awareness) is a development organisation registered as a society

under the Societies’ Registration Act of 1960.

child4 indicates that poverty is not only an economic condition but also includes a

culture that sometimes deprives children of their fundamental needs. A significant

finding of this study is that a child’s well being is more dependent on the

prioritisation of expenditure of the parents rather than on their income level.

Children of daily wage earners were found to be less likely to attend school than

those of monthly wage earners despite the fact that the absolute income (per month)

of the former is more than the latter.

“A child's

MAYA’s initiative to eradicate child labour in the sericulture sector of Bangalore

Rural began in January 19985. The purpose was to understand better the differences

well being

between the urban and rural setting in terms of social structure, cultural ethos,

is more

socialisation, and related factors that directly or indirectly impact the child’s

dependent

development. The high incidence of child labour in the sericulture industry, coupled

on the

with the complete absence of any effective intervention on the part of either the

.

.

I..

i ■ i

r

..............

,•

Government or the voluntary sector has also been a deciding factor in initiating this

prioritisation

project. In the light of these conditions, MAYA initiated a research study in order to

understand the factors that account for such a high incidence of child labour in the

expenditure

y

of the

area.

Objective of the Research Study

This study is not merely an academic exercise that seeks to establish or recognise the

rather than

on their

incidence of child labour in the area. On the contrary, die study starts from the premise

t^at tfoc jssue of child labour in the sericulture sector is a reality and MAYA is

committed to addressing this issue. It highlights the need for the Government and

donor agencies to recognise that the situation has become so grave that it is impossible

level.

for most people to even imagine the sector without children working. The condition

cays for a concerted effort by the Government, licencing authorities, community,

donor agencies and voluntary organisation to work towards the eradication of child

labour.Thc study also seeks to caution other states in the country who view this industry

as a ‘success’ and want to initiate it in their own state. Though sericulture has the

potential to be a successful, income- generation industry, one cannot afford to ignore

the plight of die people, especially the children, working in this sector and the price

they are paying for the ‘success’ of the industry.

4

Study on ‘Wage pattern and impact on the family and child* conducted by MAYA in 1997, in its working areas in

Bangalore Urban.

5

MAYA presently works in 40 villages and slums in the two talukas of Channapatna and Ramanagaram in Bangalore

Rural district. (These areas have been selected on the basis of the number of child labourers and the condition of

Government schools, basic amenities related to children etc).

There is a detailed description in this study of the different processes involved in the

sericulture industry’ and the condition of the children working therc(see Appendix 1).

The study concludes with a set of suggestions required for eradicating child labour in

the sericulture industry.

Methodology 6

Pilot Surrey

z\ pilot survey was conducted in 20 villages and slums in the two talukas of

Ramanagaram and Channapatna (Please sec zXppcndix 11 for details of these areas.

Through this survey, 14 areas were identified with respect to the incidence of child

labour and the socio-economic conditions prevalent in the area. Finally 6 of these 14

areas were selected for an intensive study on the basis of the diverse conditions,

characteristic of the particular village or slum that had contributed to the prevalence/

absence of child labour in the sericulture sector.

Si%e of Study

The study in the 14 areas covered a total of 5460 households, i.c. a population of

34,423 persons. The total child population surveyed was 6099, of whom the number

of child labourers was 1591. The average percentage of child labourers to the total

child population was found to be 20.3%. There were two areas, however, where the

percentage was found to be as high as 64% and 45.5%.

Aspects of Study

Primary socio-economic data of the families in these areas was collected and analysed

with regard to different indices such as monthly household income, family expenditure

pattern, schooling background of children, and gender of working and school going

children.

Analysis

Analysis of the data as illustrated shows that child labour is not a result of poverty of

the families but one of sheer neglect and indifference on the part of the parents,

community and the State. The secondary data collected also substantiates the results

of the analysis and further validates the need for immediate action on the issue.

6

This study has been conducted by MAYA in its working areas in Channapatna and Ramanagaram, with documentation

support by Dr A.R.Vasavi, National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore.

Though India is the second largest silk producer in the World after China, it accounts

for just 5% of the global silk market, since the bulk of Indian silk thread and silk

cloth are consumed domestically. Germany is the largest consumer of Indian silk.

The sericulture industry is land-based as silk worm rearing involves over 700,000

farm families and is concentrated in the three Southern states of Karnataka, Tamilnadu

and Andhra Pradesh. (The states of rYssam and West Bengal are also involved in the

industry to a certain extent).

The present market context for silk in India

is one of vigorously growing internal

demand for silk fabrics, with growth rates of

above 10% per year. It is mostly for

traditional (sari type) design and docs not

impose sophisticated quality requirements

upon the industry. This situation is likely to

continue, unless Indian sericulture is able to

provide sufficient quantities of raw silk at

affordable prices. The present trends

represent a limitation to price increases for

silk produced in India by import from other

silk producing countries like China, Brazil,

Korea etc., as well as by substitution with

other fibres including by artificial silk. It also

appears unlikely that the present demands can be met merely by expanding mulberry

area in order to increase cocoon and raw silk production. Future additional output

in raw silk will therefore mostly have to come from substantial productivity increases

and labour productivity.

Concurrently there is an increasing demand for silk fabric among the growing Indian

middle class and young urban consumers. These modern silk fabrics typically are

produced by the expanding power loom weaving industry. The quality requirements

imposed by this trend can only be met by bivoltine raw silk, although it is possible to

produce high quality multi-bivoltine silk for conventional powerlooms. The bulk of

today’s world export demand is almost exclusively based on high graded quality

bivoltine raw silk. If Indian sericulture is unable to generate a substantial production

7

which Silk route this?

of bivoltine raw silk, these important market segments will continue to be lost to

outside competitors.

Hence, three main market segments offer great opportunity to India’s silk industry:

(i) the broadening domestic traditional demand multi bivoltine based, (ii) the domestic

demand for non-traditional silk fabrics, based adeast pardy on non-graded bivoltine

raw silk, (iii) the vast and expanding international market for raw silk, silk fabrics and

ready-mades, based on graded bivoltine silk, an export potential as yet relatively

little exploited by India.

In one of the efforts of die Indian Government to promote the sericulture industry,

the National Sericulture Project (NSP) was initiated as a national project operational

in 17 States in India. The project funded by the Central and State Governments

together with an input of foreign funds, has a credit portion from the World Bank

and a grant contribution from Swiss Development Corporation. The project was

started in 1989 for a period of six years with the objectives oriented toward increased

production, improved productivity, quality and equity. One of the critical elements

taken into consideration by the project was the dominant involvement of the Central

and State Government organisations in the promotion of sericulture.

8

Karnataka is the premier mulberry silk producing state in India. Rearing of silkworms

and commercial production of cocoons and silk in Karnataka date back to the 18th

century, when sericulture was patronised by the rulers of the erstwhile Mysore State.

Sericulture is practised both under rain-fed and irrigated conditions.

History of sericulture in the region7:

Pre Independence Period:

Sericulture is not new to this region — its

beginning can be traced back to Tipu Sultan,

the ruler of erstwhile Mysore State, who

organised a silkworm rearing unit in the

southern parts of his region. Channapatna is

believed to be one such centre. Emissaries

were sent to different parts of the world and

finally procured a yellow multivoltine race,

suited to the climatic conditions of the

region, which is surviving till today.

Sericulture did show progress between

1866-1875. There was much demand for

Mysore silk in the world market and it fetched

a comparatively higher price. In 1896, a new

silk farm was started by J RD Tata in Bangalore, which produced healthy eggs out of

its own tearings and offered training to sericulturists.

The Department of Sericulture was opened in 1913-14 and a Silk Farm established

in Channapatna in 1914. By 1917, high yielding varieties, modern methods of grainage,

silk farm works, and hybridisation were in operation due to the services of the Japanese

expert Yonemura. He also gave the idea of establishing an isolated seed area for

propagating the pure Mysore race and protecting the exotic races from European

countries. Efforts were also made to introduce the subject as a two-year course under

the State Education Department. The Second World War gave an impetus to the silk

industry. All the cocoons produced in the state were taken to the Mysore Silk Filatures

Ltd. and all the filatures were turned to war production (to produce parachutes).

This increased production and the area under mulberry also increased. The technique

of filature reeling was also improved. Cocoon harvesting also gained momentum.

Karnataka State Gazetteer: Bangalore Rural district, 1990.

9

which .bilk route this?

In 1921, the Government Silk Filature was established at Mysore to help the

sericulturists in reeling with cottage basins. Twelve Italian basins were also imported

during this period which worked continuously for 17 years. Efforts were also made

to assemble these machines indigenously. In 1925-27, the domestic basin was evolved.

This was a simple silk reeling device, inexpensive but adequately serving the needs of

the small-scale reelers. While the Government was paying attention to the developed

machines, die country ‘charaka’ was improving its production. In 1929, there was a

crisis in the waste silk trade abroad. Large quantities of silk waste had accumulated in

the State. The reelers had to face many problems- the reeling rate had to be reduced

and even the wages had to be curtailed.

Post war Period:

The post-war period saw a slump in filature production. The large production at a

high cost (till then paid for by the War Department) could not be sold in the open

market. The filatures ran into financial difficulties. The Government took over all the

filatures and continued running them even at a loss as it provided work for a large

number of persons and helped establish the price of the cocoons.The slump in the

post war period made the Central and State Governments think of means by which

the industry could be developed as it provided work for a large number of farmers

and landless labourers. At Delhi, the Government of India constituted a Silk

Directorate and a Silk Panel in 1945. The report of the Panel stressed the need for an

all India body to work up Five-Year Plans and provide the finances for this.

The All India body turned out to be the Central Silk Board. The Central Silk Board

Act, 1948 was passed and the Board came into being on 01 z\pril 1949.

Growth tinder Plans

Thefollowing data show that sericulture is a much-favoured industry in the State and has been given

adequate emphasis in the Plans:

• There was an increase in mulberry production and non-mulberry raw silk during

the First Plan. Though the production technique and cost of production were not

significant, various developmental schemes were designed to consolidate the

industry.

10

• The Second Plan was significant from the point of view of development of seed

organisation and improvement of silk reeling. Improved cottage basins were

introduced on a large scale.

•

During the Third Plan, chawki rearing centres were established and cocoon

markets started in the cross breed area.

• The Fourth Plan saw an increase in the number of families being covered by the

sector, larger area under mulberry cultivation, increase in the number of charakas

and cottage basins, and in raw silk production.

•

The Fifth Plan witnessed a growth rate of 7.5% in sericulture and several special

schemes were also taken up.

• The Sixth Plan had a larger budget allocation to the sector. During this period, the

industry suffered due to the attack of a fly called ‘Uzi’ which spread from Hoskote

taluk to other rearing centres in the district and other parts of the State.

•

The Seventh Plan saw an increase in Karnataka’s percentage share in India’s total

raw silk production. /\t the end of 1988, there were about 55,465 farmers culti

vating mulberry in 41,127 acres of land in 2032 villages.

• Special emphasis was given to the devel

opment of sericulture in the Eighth Plan

on account of its economic importance

and employment generation. In 1992-93,

the area under mulberry cultivation was

1.58 lakh hectares and nearly 6.65 lakh

families were employed in the industry.

•

In the Ninth Plan period, rhe number of

chawki rearing centres in rhe district has

increased to 219 and the cocoon produc

tion in 1995-96 was 16,051 tonnes.

Today Karnataka produces 9000 MT of

mulberry silk out of a total of 14000 MT

produced in the country, thus contributing to

nearly 70% of the country’s total mulberry

silk production. It has the largest area under

11

which Silk route this?

mulberry cultivation in the country. As much as 1.4 lakh hectares arc under mulberry

cultivation in this State alone. Unlike the other States, the Department of Sericulture

here has fully developed infrastructural facilities required to meet the demand of

Despite such

silkworm eggs not only of the State but also of some districts of the neighbouring

states, through organised seed cocoon growing areas. The State is producing nearly

heavy

20 crores of silkworm eggs enabling the farmers to produce about 48,000 MT of

investment...

cocoons annually.

Sericulture which was earlier confined to a few districts has now spread to other

little or no

attention has

areas, because of the introduction of new technologies, new varieties of mulberry

and new silkworm races which have made sericulture more profitable than other

been paid to

crops. The Karnataka Sericulture Project was functional from 1980 to 88 and aimed

the growing

at establishment of project infrastructure and services. Its performance was said to

incidence of

be satisfactory and it is said to have accelerated the growth of Karnataka’s raw silk

production from 2900 tons in 1980-1 to 4700 tons in 1986-87. Today, there are nearly

8 lakh families employed in the sericulture industry’ in rhe State. Despite such heavy

in the

investment to develop the infrastructure and other technological aspects of the

sericulture

industry, little or no attention has been paid to the growing incidence of child labour

in the sericulture industry’ in the State.

There are an estimated 36 lakh child labourers in the state. z\ccording to the 1991

census, the participation rate of children aged 5-14 as full-time workers is 8.2 for

boys and 6.5 for girls. It is 0.7 and 2.2 as marginal workers. The ratio of child workers

to adult workers in the industry is 2:1 for reeling and twisting. In weaving, the

employment of children is limited.

The Govt report ‘Human Development in Karnataka-1999’, cites the findings of a

study by the Human Rights Watch8 to state that 80% of the individuals involved in

reeling silk in Karnataka are between the ages of 10-15 years.

Despite this observation, however, there has been no definite action by the Govt to

prevent the employment of children in the industry.

The main silk regions in the State are the four talukas of Channapatna, Ramanagaram,

Kanakapura and Magadi in Bangalore Rural district (See appendix III for overview

of Bangalore Rural district), and Kollegal taluka of Mysore district.

8

The Small Hands of Slavery: Bonded Child labour in Karnataka, Human Rights Watch

12

child labour

industry in

the State.

Oericulture in -Bangalore Jtvural JLIistrict

Sericulture is a labour-intensive agro-based industry. It includes growing of mulberry

plants, rearing of silkworms, production of cocoons, and reeling of silk-yarn. While

cultivation of mulberry and rearing of silkworms are agricultural in character, reeling

of silk, twisting, and weaving are distinctly industrial in nature. The reeling of cocoons

is done in cottage establishments or in large factories called filatures. Sericulture is a

means of livelihood for over 51,700 families in Bangalore Rural district.

CHANNAPATNA

Channapatna situated on the State highway, approximately 62 km from Bangalore,

forms one of the eight talukas of Bangalore Rural district. In 1873, it was a sub-taluk

under Closepet (Ramanagaram) and only since 1892, it has been recorded as a full-

fledged taluka. Today it is a part of Division I (the sericulture belt) of Bangalore

Rural district, with a total of 145 villages.

Population:

According to the 1991 census, Channapatna taluka has a total area of 543.4 hectares

and a population of 239,203. The child population (5-14 years) of the taluka is 46,200.

The population density of the taluka is 400 persons per sq.km. The rural population

(183,994) accounts for nearly 77% of the total population while the urban population

of 50,725 for only 23%. Of the urban population, 45% are slum dwellers. There arc

22 slums in Channapatna. The total working population of the taluka is 103,400.

35% of the total population arc main workers. Of this, 8% arc agricultural labourers,

16.1% cultivators, and 11% constitute ‘other workers’. 4.7% of the total population

arc marginal workers while almost 60% are non-workers. Hindus and Muslims

constitute a notable percentage of the population in the taluka. Scheduled Castes and

Tribes also form a sizeable part of the population (16.4%).

Education and Literacy:

The literacy rate is 43% (an increase from 30% in 1981). There are a total of 245

Government primary schools in the taluka and the number of children enrolled is

30,702. There arc 247 anganwadi centres in the taluka. There are 31 High schools in

the taluka with 9038 children enrolled.

13

which Silk route this?

Economics:

There is a dam at Kanwa, 6 km from Channapatna town, after the construction of

which the agricultural production has increased rapidly. The main crops grown here

arc paddy, ragi, mulberry, groundnut seeds, etc. The place is also famous for its wooden

toys’ industry. There is an agricultural market committee established due to the increase

in rice and silk production. The town has trade links with 45 surrounding villages.

RAMANAGARAM

Ramanagaram situated (48 km from

Bangalore) in a valley surrounded by rocky

The total

hillocks has been the sub-divisional

child

headquarters from 1884. It became the taluka

headquarters in 1928 and the place was named

population

Ramanagaram in 1949. It is the largest cocoon

in the

marketing centre in Asia. Ramanagaram has

taluka is

a total of 135 villages within its taluka limits.

Population:

According to the 1991 census, the total

47,411 of

which

13,000

number of households in the taluka is 39,057

with a population of 205,956. Of this the rural

population is 75.5% (155,519) and the urban

population is 24.5% (50,437). The total child

population in the taluka is 47,411. Of the total

working population of 87,600,13,000 are child labourers. 52% of the total population

are cultivators, 16.1% are agricultural labourers, and 24.9% arc ’other workers’. 5.9%

are marginal workers, of whom 95% are women. Almost 60% of the total population

are non-workers.

Education and Literacy:

The literacy rate of the population is 49.21%, according to the 1991 census. The total

number of Government primary schools in the taluka are 256 with the total children

14

are child

labourers.

enrolled as 33,899. There are 7625 children enrolled in rhe 30 High schools in the

taluka. There arc 157 anganwadi centres for the (0-6years) child population of 33,508

(1991 census) in the taluka.

Sericulture in Ramanagaram

Majority of the working population in Ramanagaram taluka are employed in different

stages of the sericulture process. Since Ramanagaram is the largest cocoon market in

Asia, the average daily cocoon arrivals at the Ramanagaram cocoon market vary

between 15-50 tonnes. Most of the reclcrs do this job as this is their traditional

occupation. Muslims constitute about 90% of the reeling entrepreneurs. Hindus are

new entrants to the field, over the last 20 years. While most of the rcelers have been

living there for generations, more than 50% of the workforce arc migrants from

Kollegal, Yelandur and Chamrajnagar who have come- into town in search of work

during the last two decades of expansion in the sericulture sector.

Description of issues presently faced by the people in the two talukas

There arc approximately 630,000 people living in the 280 villages of Channapatna

and Ramanagaram talukas in Bangalore Rural district. The urban influence of the

slums on the villages is growing, creating a need for working simultaneously in slums

and villages. People living in the working area belong mostly to SC/ST and minority

community. The region is extremely sensitive to caste and religion problems and

prone to communal tension.

There is scarcity of drinking water supply in the areas and there is a lack of proper

sanitation and sewage. Basic amenities of toilets and electricity arc inadequate. The

educational institutions in the villages and slums do not function properly and face

problems of inadequate teaching staff, lack of water and toilets, which results in low

learning levels of children and drop-outs. Other institutions for children like

anganwadis and balwadis also function poorly. The women and youth in the area are

not adequately aware of the different Government schemes and programmes for

poverty alleviation, slum / village development and income generation. Existing

village and slum based institutions / facilities too are inaccessible and apathetic to

the needs of the people.

The area receives poor rainfall and is sometimes drought prone. This proves a major

problem for the area, as people cannot depend on agriculture as a means of livelihood.

The food-grain production has been declining over the past few years. The average

15

which Silk route this?

size of land holdings has also been declining over the past few years, forcing people

to move from agriculture to other sectors of work. Sericulture is one such sector that

has grown manifold over the past few years. However even in this sector, in terms of

crop development, little has been done to train and provide adequate support services

to farmers in mulberry cultivation.

Some statistics regarding sericulture in Channapatna and Ramanagaram

talukas:

Ramanagaram

Channapatna

Total no. of reelcrs

1923

433

Total no. of charakas

1065

284

Reeling:

No. of workers (male)

743

503

No. of workers (female)

867

832

Total no. of filature units9

854

149

No. of workers (male)

3280

628

No. of workers (female)

4392

711

34

-

No. of workers (male)

18

-

No. of workers (female)

22

-

Total no. of multi-end

reeling machines

Twisting:

163

37

Total no. of machines

628

114

No. of workers (male)

822

386

No. of workers (female)

722

66

Total no. of units

8

8

Total no. of machines

48

46

No. of workers

58

67

Total no. of units

Weaving:

9

Each filature unit has between 4 and 10 basins, i.e. an average of 8 basins.

16

Child Labout in the

Children work in the sericulture industry mostly on compulsion exerted by the parents

who have taken an advance from the employers (rcclers), not out of economic

constraints to eke out a living but for immediate expenditure. Of the total number

of families studied, nearly 80 % had taken loans for marriages, festivals, etc. The

children are made to work as bonded labourers till the advance money is adjusted

against the wages of the children or till it is paid back. Children work as turners and

helpers, pupae pickers, and cocoon cooks in the filature units. The preference for

children to work in the sericulture industry is because of the narrow space and the

low height (they have to be shorter than the height of the bobbin). They stand cornered

against the wall, and trapped under the machinery, as if in narrow cages, waiting for a

ladleful of cocoons to be put aside by the rceler every now and then. A lot of

concentration is necessary to avoid wastage and minor lapses are enough to invite

reprimand.

Child labour in the country is prohibited and regulated in various processes /sectors

by the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986. The Act classifies various

sectors and processes as ‘hazardous’ or ‘non-hazardous’ based only on the physical

working environment.. However such a perspective fails to recognise that any process

involving child labour is detrimental to the

child, since it hinders the overall

development and health of the child; health

in this context refers to the physical,

emotional and social well being of the child

(as defined by the WHO).

In this study conducted by MAYr\, besides

a detailed survey of particular villages and

slums in the two talukas, the children’s

health conditions and several critical

factors influencing their educational

opportunities were observed, analysed and

documented. These areas were identified

for a detailed study, due to the high

incidence of child labour and the specific

conditions existing in each of the areas.

Also refer tn 'Elcgalondluge elqraru* -a stutly done by K S Saroja on the condition of chJdrcn uxirking in twisting units in Ntagadi.

17

Wliicli Silk route this?

eas 11

Honganur

This village, 6 km from

Channapatna town on

the Sathnur Road is

spread over an area of

about 612 acres. It has a

total of 1125 households

with a population of

6820. The population

has both Hindus and

Muslims. The Hindus largely belong to the SC, Gowda, and Urs communities. The

main occupation of the people there is agriculture, filature, trading and goldsmith.

Honganur is the Gram Panchayat centre for the surrounding villages. There arc three

Government schools-1 Urdu Higher Primary School and 2 Kannada medium (1

Higher Primary and 1 High school) and four anganwadis for children. There is also a

Government ‘shishuvihara’ for SC/ST children and a Pre- Primary’ Centre for children

below five years. The village also has a residential Ashram school (l*'-4,h standard)

for SC/ST children, under a scheme from the State Government. There is a private

Higher Primary school in the village. Honganur also has a private Prc-Univcrsity

college. Honganur has a Government Lacquerware training centre to impart 1-ycar

training to 25 persons. There is also a Government tailoring centre under the TRYSEM

scheme. Being an important village, there is a Primary Health Centre as well in

Honganur. Other facilities like a Fair Price Shop, post office, milk dairy etc also exist

in the village. The members of the Masjid Committee in Honganur have formed a

Social Welfare Association, besides which there is an Ambcdkar Sangha in the village.

Despite these facilities and being the Gram Panchayat centre, of a total child population

of 870 in Honganur, 200 are child labourers. These children are employed in filature

units mainly, though some also work in garages, shops, housework, assisting goldsmiths,

etc.

18

For statistics regarding child population and percentage of child labourers in the studied areas, see appendix 1

Kariappanadoddi

Kariappanadoddi is a village in Channapatna taluka, 2km from Channapatna town. It

is basically a wooden toy industry-based village. The village has a total of 226

households inhabited by a population of 1188. Though the enure population belong

to the same caste of Bestha, there is a distinction made between the families that are

economically better-off and those who arc not. The main occupations of the village

are mainly agriculture, toy-making, and collecting firewood. Of the total child labour

population of 92 in the village, only 10 work in the sericulture sector. The remaining

are engaged in cattle grazing, at home, in brick-kilns, in the agriculture sector and a

few children work in the toy-making units. Kariappanadoddi has a Government

primary school from l*'-7'h standard and 1 anganwadi for children for children below

the age of six.

Molledodi

Of a total

Molledodi is a village in Channapatna taluka with 360 households inhabited by a

total population of 1700. The village population belong to a single caste of Bestha,

child despite which there are differences among those who are relatively better off than the

population others. A large percentage of the population live in thatched huts. The main

almost 27%

occupations here arc agriculture, sericulture and business. Of the total child population

of 408, 110 arc child labourers i.c., almost 27% of the total child population do not

do not attend school. These children work mainly in the sericulture sector, at filature units in

attend Channapatna town and some go to Honganur also to work. The village is devoid of

school

any developmental activity either on the part of the local Government or by the

people themselves. There is no association of women or youth in the area, unlike

what is commonly found in most villages. The village faces acute water scarcity ,

especially during summer.The area also has high incidence of alcoholism. There is a

Government Lower Primary school in Molledodi until 5,h standard. There are also

two Government-run anganwadis for children below the age of six.

Adi Jambava Colony

Adi Jambava Colony is a slum locality in Channapatna town, with a total of 125

households and inhabited by a population of 550. The entire population belongs to

Adi Jambava (mentioned in the Scheduled Castes list). Children from this area work

mainly in the sericulture industry. /Vdults work as daily wage labourers in the fields or

are engaged in hawking. Some of the women work as bottle cleaners in distilleries

situated in Bangalore. There is a Government school upto Standard 7 which is adjacent

19

which Silk route this?

to the colony. Though the school has adequate infrastructure, the enrolment in this

school is poor. The area does not have adequate basic amenities. There arc no organised

groups or sanghas in the area that would undertake any developmental

activities.Though the income levels of people is not very poor, compared to other

slums in Channapatna, the parents prefer to send their children to work in the silk

units. Even though it is a homogenous community, there are various informal groups

who work against the common good of the community. A women’s sangha has recently

been formed to address children’s issues and look into the developmental needs of

the area.

Badi Gali and Choti Gali

This is a slum area located in the centre of Channapatna town. It is unique in that it is

a slum locality surrounded by a high income residential area. The number of child

labourers working in the sericulture industry is fairly large. The total population of

the area is 1300 with the number of households numbering 250. The area is so

named because it is inhabited by Muslims belonging to two different belief systems.

The area has a number of filature units where children from neighbouring slums and

villages close to Channapatna town come to work. The total child population of the

area is 410, of whom the child labourers number 94, i.e. almost 23% of the total

child population.

Baalgere

Baalgcre is a slum locality, situated close to the main market area in Ramanagaram

town with a total population of 3300. It is one of the bigger slums in Ramanagaram

and is inhabited by a mixed population of Scheduled Castes, Mara this, Tamil migrants,

Muslims and Thigala. The area has one Government Higher Primary school (till 7,h )

and two anganwadis for children below the age of six. There is a Government run

pre primary centre also in the area. Among other facilities, Baalgere has a community

hall. There are two youth sanghas(groups)-thc Dalitha Sangharsha Samithi and the

Thigalaru Sangha in the area. People in the area arc mostly occupied in the silk

reeling units in and around the area. Some others work in the shops or are daily wage

earners as well. Children from this area go to the reeling units in the area or to units in

the surrounding slums to work. Though there is no immediate problem of water

and drainage, the area lacks proper toilet facilities. There is no clear demarcation but

20

the houses in the area arc of two kinds-those of the slightly better off families which

are at the entrance to the slum and those of the SC community and Tamil migrants

which form the rear part of the slum.

Yarab Nagar

Yarab Nagar is one of the biggest slums in

Ramanagaram town, situated close to the

railway station. It has a total population of

about 5000 with a child population of about

1500. It is a Muslim locality that has grown

manifold in area and population in the recent

years due to migration of Muslims from other

neighbouring villages after the 1991 riots.

Yarab Nagar forms part of the chain of slums

in the Kothipura-Ammaalikere area of

Ramanagaram. This, together with the

surrounding slums, houses the maximum

number of filature units in the town limits and

also employs the highest number of children.

In Yarab Nagar alone , there are over 500

child labourers who work in the filature units

locally / in the neighbouring slums. Of the total child population of 1100, almost

50% are child labourers who work in the sericulture industry alone. The area thrives

on a workforce of adults, youth and children alike, in the sericulture sector. A handful

of individuals of the total population also work in garages, tailor shops, butcheries,

and bakeries. Some of the women and young girls in Yarab Nagar are engaged in

beedi-rolling within their homes. There are two Government lower primary schools

(from rr-4,h and from l“-2nd). and a Government-run anganwadi in the area. There is

also a private creche in the slum run by a local person. The problem of water and

drainage in the area is not as critical as that of toilet facilities. There is absolutely no

proper facility for toilets in Yarab Nagar. The children, young girls and women

especially are the worst affected by this condition. The schools also do not have

adequate toilet facility for the children. With regard to water, while some parts of the

slum get water in an adequate quantity, others who are at a height do not. The water

that is available is also very hard and affects the health of the people, if not boiled/

21

Which Silk route this?

The correlation of factors influencing the educational opportunities of children in

the studied areas arc summarised below:

i

Monthly Household Income Level

and children’s Educational

Opportunities

A correlation between the monthly household income of the families to the condition

of the child/children (school going or in child labour) indicated that there is no

direct link between income and education opportunity. In the studied areas, almost

25 % of the households with income below Rs 1000 per month were sending

children to school. In contrast, households with income above Rs 3000 per

month sent their children to work

Family Income Level

< Rs 1000

Rs 1000-2000

Rs 2000-3000

Rs >3000

Areas

Child

labourers

School

goers

Child

labourers

School

goers

Child

labourers

School

goers

Child

labourers

School

goers

Honganur

7.20%

24.70%

9.50%

36.00%

3.50%

12.00%

2 80%

4.30%

Kariappandodi

8.50%

10.70%

8.90%

27.70%

9.40%

17.40%

4.50%

2.90%

Molledodi

3 30%

11.60%

15.30%

40 00%

7.60%

15.30%

2.80%

3.20%

Adi Jambava

Colony

7.80%

26.50%

4.00%

33.00%

2.20%

10.50%

3.50%

12.50%

Badi Gali

Baalgeri

3.10%

3.40%

8 50%

50.30%

4.40%

10.10%

15.60%

25.20%

4.90%

3.00%

9.00%

5.00%

2.00%

1.00%

4.40%

2.00%

As illustrated, almost half the child population (50.3 %) at Baalgeri attends school

despite coming from families that earn a monthly income below Rs 1000/-. This

is primarily due to the presence of a Government higher primary school in the

vicinity of the slum, where the environment in terms of physical infrastructure,

basic facilities and teaching is supportive of children’s learning. In contrast, the

presence of a Govt school in Kariappandodi has not ensured similar high attendance

to school from families of the same income level, as the school is ill-equipped

and not supportive of children’s learning needs.

This clearly indicates that despite low-income levels, parents are willing to send

their children to school, provided they find the schools meeting the children’s

educational needs. Secondly, the mere physical presence of a school does not suffice

22

Children involved in various processes of the sericulture industry

: Cooking the cocoons

to kill the silkworms by

dipping their hands

dirccdy in boiling water

and pulsating the

cocoons - one of the

most unhygienic

processes.

'Transporting

cocoons from

the market to

the filature

units.

6 Disposing the dead worms

and other waste.

23

to ensure that children attend school. The school must provide an educational

environment that meets the learning needs of the children and the local community.

In further substantiation of this, it was found that in Kariappandodi 4.5 % of the

families sent their children to work, despite earning a monthly income of over Rs

3000/-. These families though in an economically better position, preferred to make

Correlation between monthly household Income and

children's educational opportunities

their children work in their own toy units rather than send them to the local Govt

school, where they did not see the use of the education received. In Molledodi also,

2.8 % of the families did not send their children to school inspite of a monthly

income above Rs 3000/-; however the main reason here was apathy and neglect of

the parents and community, rather than an economic one.

These observations dispel the myth of poverty of income being the primary cause

of child labour. Factors such as the condition of local Govt schools, parental

and community participation and support were found to be more crucial in

determining the children’s educational opportunities.

ii

Expenditure Pattern of Families and Children’s Educational

Opportunities

On studying the relationship between the expenditure pattern of the families and the

condition of children, it was found that in a majority of families of child labourers,

the expenditure on marriages, festivals and alcohol was much higher vis-a vis the

families of school going children. This is a clear indication that rather than the lack of

income, it is the lack of prioritisation of expenditure that determines the children’s

educational opportunities.

24

Marriages

Child

labourers

School

goers

Honganur

16.70%

Kariappandodi

19.00%

Education

Alcohol

Festivals

Areas

Child

labourers

School

goers

24.70%

9.50%

11.90%

11.90%

Child

labourers

School

goers

Child

labourers

School

goers

36.00%

3.50%

12.00%

2.80%

4.30%

8.70%

15.90%

4.80%

3.90%

23.80%

Molledodl

7.40%

4.40%

20.60%

17.70%

26.50%

7.40%

2.70%

13.30%

Adi Jambava

Colony

Badi Gali

11.80%

7.60%

9.90%

7.50%

13.90%

9.60%

1.00%

38.70%

10.00%

8.90%

14.20%

16.60%

6.60%

6.60%

0.00%

37.00%

Baalgeri

15.10%

12.80%

19.30%

12.40%

7.40%

4.60%

1.00%

27.40%

In Mollcdodi it was observed that the expenditure on alcohol among families of

child labourers was as high as 26.5 %, when compared to 7.4 % in families of school

going children. Likewise, the high expenditure on festivals among families of working

children in Baalgeri was seen to be responsible for a large number of children going

Correlation between expenditure pattern of families

and children's educational opportunities

to work. Similar observations in the other areas also revealed that the lack of

prioritisation of expenditure strongly influences the condition of children, determining

whether they attend school or go to work. z\ study of the expenditure on education

showed that only less than 2 % of the families of child labourers spent money on

education as compared to 25.9 % of the families of school going children.

iii

Gender of Children in Relation to the Child Population in the Area

In all the studied areas, it was

observed that the percentage

Gender In relation to children's educational opportunities

of girl children not attending

school was higher than that

of boys. It was found that the

percentage of girls attending

work

was

15.8

%

as

compared to 12.6 % of boys.

25

Which Silk route this?

Child Labourers

School Goers

Area

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

Honganur

19.20%

23.90%

32.00%

2500%

Kariappandodi

13.70%

42.40%

11.60%

32.20%

Moiled odi

14.00%

45.30%

13.20%

27.70%

Adi Jambava

Colony

Badi Gali

7.40%

39.20%

10.00%

43.40%

these girls

10 70%

40.10%

16.30%

32.90%

Baalgeri

13.80%

39.60%

9 50%

37.20%

are not

...though

directly

In Honganur and Badi Gali, the percentage of girls not attending school was much

higher (32% and 16.3 % respectively) than that of boys (19.2% and 10.7 %

any formal

respectively). r\n important feature to be noted is that, though these girls arc not

sector, they

directly working in any formal sector, they arc child labourers. They are forced to

stay away from school to look after younger siblings, maintain the house and /or be

engaged in rolling incense sticks, beedis, etc at home. Consequently, these girl children

lose out on educational opportunities to a much greater extent than the boys do.

iv

Schooling background of the working children in the studied areas

In all the areas studied, there was a high percentage of working children who had

never been to school at all, thereby clearly indicating that the availability of

employment serves as an incentive for parents to send their children to work.

'26

working in

are child

labourers

Never

Attended

School

2nd

Honganur

23.60%

6.60%

Kariappandodi

29.10%

7.60%

Molledodi

45.00%

8.00%

Adi Jambava

Colony

Badi Gali

28.60%

37.10%

15.00%

17.50%

Baalgen

16.90%

13.60%

Yarab Nagar

51.80%

8.70%

11.90%

3rd

7th

8th

6.60%

12.60%

4.40%

5.10%

15.20%

5.10%

4.00%

19.00%

11 00%

3.00%

2.80%

5.70%

2.80%

5.70%

8.80%

3.30%

30.00%

15.60%

3.30%

20.30%

13.60%

10.20%

10.20%

25.40%

13.50%

10.30%

1.60%

4th

5th

6th

7.70%

16.50%

17.60%

8.90%

14.00%

6.30%

5.00%

5.00%

17.10%

6.80%

In Molledodi, 45% of the working children had never attended school, largely because

this village docs not have a culture of sending children to school and the school that

exists, has been established only recently. Proximity to Honganur, one of the few

villages where silk units arc based, is also a significant reason for the large percentage

of children not attending school in Molledodi. Almost half the number of working

children (51.8%) in Yarab Nagar have never been to school at all. The reason for this

is the mushrooming silk filature units, coupled with the lack of any intervention by

the authorities. Consequently, sending children to work at the filature units has become

almost a custom in the area, for the past several decades.

In Baalgeri, the high dropout rate seen in Std 7 can be explained by the fact that the

slum has only a Govt Higher Primary School (upto 7,h std) and the children have to

go a long distance to attend the Govt High School (the only one in Ramanagaram).

This is true, particularly for girl children in the area.

The correlation studied between these different factors and the educational

opportunities of children in the areas clearly indicates that child labour is

primarily caused by factors such as ineffective functioning of Govt schools,

community apathy, parental neglect, and the lack of prioritisation of

expenditure rather than poverty of income. Child labour enhances the possibility

of retaining a family in poverty. Children who work during their childhood in the silk

units arc devoid of any skills or education on reaching adulthood; thereby leaving

them unemployed, economically disadvantaged and ill-equipped to earn a livelihood.

27

which Silk route this?

Reflections of Adolescents Previously Employed in the Silk Filature Units

As a part of the research study, we also spoke to a group of adolescents who had

spent their entire childhood working at the silk units. On the one hand, these youth

Child

were now no longer required to work at the filature units, and on the other, they were

labour

ill equipped to take up any skilled work. Consequently, they were forced to work in

the informal, unorganised sector as coolies in the cocoon market, as daily wage

enhances

labourers, mechanics, etc. r\lmost all the youth had been sent to work by their parents

the

so as to repay loans taken for marriages, festivals, and other immediate expenditure.

possibility

These loans were to be repaid by deduction from their wages, but this did not usually

happen since the wages they received was minimal. Further, their work was dependent

on the availability of cocoons. In the absence of adequate or good quality cocoons,

retaining

children did not have any work. During this time, the parents once again took petty

a family

loans from the employers, thereby increasing the amount of money to be repaid by

the children. The youth also felt that besides losing out on education in their childhood,

they had spent the most productive years of their lives doing work that did not teach

them any skill. This proved a disadvantage for their future in that without even a

basic education they did not feel confident to learn a new skill /vocation at this age

and earn a stable livelihood.

28

of

in

poverty.

eas

Children arc employed in

almost all processes of the

sericulture industry making it

almost a child—based economy.

They

work

in

mulberry

cultivation, cocoon rearing,

reeling, winding, doubling,

twisting, and re-reeling, all of

which adversely affect the

health of the child. They are

required to work in filature

units that are cramped, damp,

dark, poorly ventilated, and

have loud, deafening music

playing in the background. The

handling of dead worms with

bare hands, and the unbearable

stench is also a cause for

spreading infection and illness.

Standing for 12-16 hours a day

with

hardly

any

break,

concentrating on reeling the fine threads, leads to other health disorders. Vapours

from the boiling cocoons and the diesel fumes from the machines also contribute to

the poor condition in the units. These conditions have been found responsible for

retardation of the child’s normal growth and development. Though there have been

other studies conducted on the health aspects of this sector, practically nothing has

been done to ameliorate the working environment in the units as a result of the studies.

There is therefore an urgent need for health professionals to come together and work

out possible solutions in this regard.

The following is a report of these conditions on the health of children working in the

sericulture industry, in Channapatna and Ramanagaram talukas of Bangalore Rural

district. To represent the existing situation in the talukas, a detailed health survey and

29

which Silk route this?

.

a medical check-up was conducted for a sample size of 200 children between the

ages of 6-14 years in the studied areas.

Respiratory Diseases

This is one of the most commonly observed ailments among children working in the

silk units. Inhalation of vapours arising from cocoons undergoing steaming, cooking

and reeling invariably produces breathing problems, asthma and other bronchial

ailments among the children. During the process of cooking, the silkworms emit a

protein called sericin in the form of foul-smelling vapours that pervade not only the

silk units but also the entire region surrounding die units. These protein vapours have

been found to be the primary cause for chronic bronchitis, asthma and other related

disorders among the children that are difficult to treat. In many areas, sawdust (used

as fuel for cooking the worms) was found in ample quantities in and around the units,

which also causes chronic irritation of the bronchioles leading to asthma. Difficulty

in breathing is also caused by other allergens present in the silk filament and poor

ventiladon in the working environment. The children work in highly damp and dirty

conditions of this process, throughout the day. The units are cramped, dark, wet and

poorly ventilated and sometimes have small generators running inside the rooms

that generate carbon monoxide and other noxious fumes. Most of the machines arc

run on diesel, which also acts as an irritant during working. The smoke generated by

the cocoons being cooked

and also by the firewood used

causes difficulty in breathing

and leads to related ailments.

In the sample studied, 86% ofthe

children werefound to be suffering

from respiratory ailments..

Scabies and Other Skin

Infections

The first step in reeling is where the cocoons are boiled in water to kill the worms and

to loosen the sericin, a natural substance that holds the filaments together. The child

dips her/his hands into the scalding water and palpates the cocoons-, judging by touch

30

whether the fine threads of silk have loosened enough to be wound. This causes

blisters and open wounds/injurics, which leads to secondary infection. The cocoons

are transported to the reeling units in ‘ganis’ (each gani measures 25-30 kg). After

every half gani of cocoons is reeled, the children have to dip their hands in the reeling

basin to remove the pupae from the basement of the water. At the end of the day, the

bottom plugs of the reeling basins are opened up to flush out the left over pupae

with the dirty water. The children who work as pupae pickers have to bend down

under the basin and clean up die place. They also have to clean up the entire premises

before the day is over. As a result of constant immersion in scalding water, with no

protection for their hands or feet, the skin of the children becomes raw, blistered,

resulting in peeling of the skin and leading to severe infection of their hands and feet.

This also causes the skin to roughen up. Children complain of difficulty while eating

spicy food, touching hot stuff and difficulty in handling things while they have blisters

in their hands. As they grow older, most of the children are not able to do complex

and intricate work using their hands. Working in damp conditions also causes the

soles of their feet to peel off leaving them unable to go out to play. 78°/o of the children

studied wen found to be sufferingfrom skin infection as described above.

Injuries

The raw silk is processed in winding units that employ children aged 6-9 years to

wind the silk into strands, which has the hazard of cutting the already soaked and

damp hands and causing injury that docs not heal in those conditions. The children

also suffer occasional injuries-mainly cuts-from the machines, particularly to their

hands and fingers. Often this kind of injuries forces the children to absent themselves

from work which then increases their “period of bondedness”. Non-treatment of

ulcers and exposure to unhealthy environment leads to secondary infection. The

slippery floors and poor draining conditions in the units arc also responsible for

injuries caused to children.

Other Commonly Observed Health Disorders

Children complain of severe headache and fever during all seasons. They spend almost

their entire waking period in an atmosphere with a strong stench, caused by the killing

of the worms, and poor ventilation. Concentration on the thread to avoid breaking

coupled with the smell of diesel, the loud noise of the machines and inhalation of the

noxious fumes leads to secondary infection of common cold and bronchitis. Since

children are exposed to work in such conditions on an everyday basis, it results in

31

Porcontaga of children with frequant

headache and body ache

In that

process,

they have

to cover a

distance of

stunted physical growth and leads to overall poor development of the child. In the

15-20 feet

filature units, children are forced to work as cocoon cooks. They put the stifled cocoons

each time,

into the boiling water in the cooking basin, remove the floss, collect the ends of the

76 times an

threads and supply them in ladles on to reeling basins. In that process, they have to

cover a distance of 15-20 feet each time, 76 times an hour and about 10-12 hours a

hour and

day. This adds upto a distance of about 4km, earning a ladle of hot cocoons, weighing

about 10-

about 700 gms.

12 hours a

Complaints of neck pain, low back pain, and general body ache is a regular feature

day.

for most children as they have to lift heavy material. Due to irregular eating habits

some of die children also complained of pain abdomen, and were diagnosed to be

suffering from gastritis. The children in the silk tunsting factories suffer pain in their

legs and backs from standing for more than 10 hrs a day without rest. Some of them

develop leg deformities over the years, including bow-leggedness. Having to stand

throughout the day leads to menstrual disorders in girl children and could also cause loss

of a child during pregnancy. Many girl children in this sector reach puberty by the time

they are 8-9 years.In the process of doubling the strands of silk, children aged 6-14

years are employed. As in the case of winding, children here arc required to stand

continuously and keenly concentrate on the yarn constandy to avoid breaking or

knotting of the yarn, often leading to related healdi problems of back ache and severe

problems of vision. The children who work as pupae pickers are exposed to the worst

condition of all. It involves working continuously in a constrained position in the

narrow space of just about two feet width between the wall and machinery, throughout

the day. Their hands and feet are exposed to the most unhygienic conditions of dead

worms, dirty water and slippery floors.

32

Hearing Disorders

Children arc forced to listen to loud music ostensibly to prevent them from hearing

the deafening noise of the machines; however this often causes problems related to

hearing. This also leads to loss of balance on occasions and lack of concentration in

the work, which results in minor mistakes that incurs abuse from employers.*

Abuse

Abuses common to other industries are found in silk production as well. Verbal and

physical abuse including threats, harsh language and beatings for arriving late, working

slowly or annoying the employer was commonly observed in the silk units. In many

eases when children are unwell or are severely sick, they arc denied adequate rest and

time to recuperate and often the

employers come to their houses

and the children arc dragged to

work.Girl workers also suffer

sexual abuse at the hands of the

employers. By and large, most

children in this sector work

under bonded conditions.

Parents take an advance from

their employers and bond their

children to their employers for

several years until the loans are

paid back with exharbitant

interest. Most of the children

are malnourished and have long

working hours leading to

chronic illnesses such as

Tuberculosis,

Chronic

Bronchitis, Asthma, non healing

Ulcers etc.

33

which Silk route this?

tate

One of the biggest drawbacks on the part of the Indian Government is that there is

no blanket prohibition on the employment of children, nor any universal minimum

age set for child.workers under the Indian law. The Child Labour (Prohibition and

Regulation) Act, 1986, the Minimum Wages z\ct, 1948, The Plantation Labour Act,

1951, The rXpprentices z\ct, 1961, and zlrucle 24 of the Constitution define “child”

as any person below the age of 14. The Shops and Establishments Act, 1961, allows

the definition to be set by the states, and in thirteen states the minimum age is 12 yrs

and in eleven states, it is 14 yrs. The Children (Pledging of Labour) Act, 1933 defines

The entire

approach

a child as any person below fifteen years of age. The Juvenile Justice Act, 1986, defines

itself has a

“juveniles” as any male under sixteen and any female under eighteen. However, the

transient

large number of‘protective’ legislations and legal safeguards for checking the incidence

of child labour mean little in the absence of a conscious political will to implement

basis and

them. All of the labour laws are routinely flouted, with virtually no risk of punishment

does not

to the offender. Whether flouted due to indifference or corruption, the fact remains

take into

that these laws arc simply not enforced.

According to vast and deeply entrenched set of myths regarding child labour, child

labour (bonded or otherwise) in India is inevitable; it is caused by poverty and

consideration

the fact that

represents the natural order of things. It is also said that working to eradicate child

the children

labour is a ‘Western’ concept. The truth is diat the Indian Government and the people

can go to

have failed to protect children.

Any effort by the Government so far has been ver}' short-lived in nature. The setting

work in

other

up of residential schools for 100 child labourers, or the raiding of shops, units, and

other establishments that employ children has not served to eradicate child labour.