NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT & INTERVENTIONAL PLAN FOR TVS , HOSUR

Item

- Title

- NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT & INTERVENTIONAL PLAN FOR TVS , HOSUR

- extracted text

-

RF_NUT_13_SUDHA

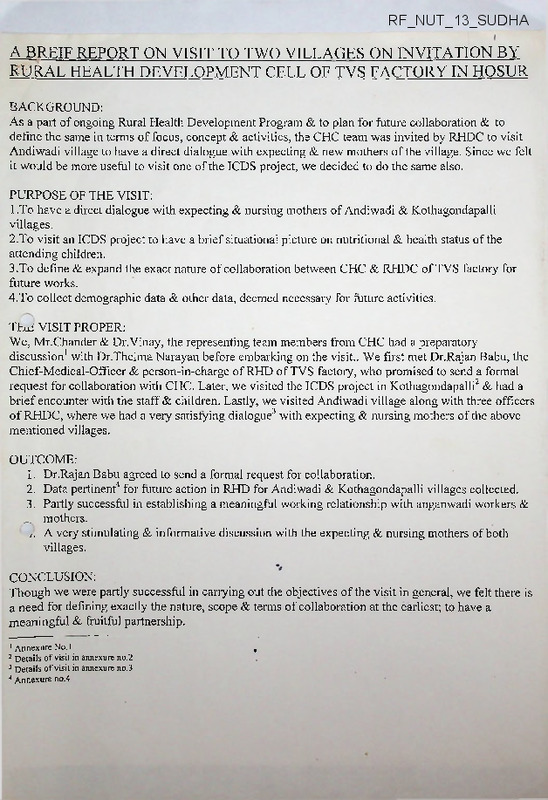

A BREIF REPORT ON VISIT TO TWO VILLAGES ON INVITATION BY

RURAL HEALTH DEVELOPMENT CELL OF TVS FACTORY IN HOSUR

BACKGROUND:

As a part of ongoing Rural Health Development Program & to plan for future collaboration & to

define the same in terms of focus, concept & activities, the CHC team was invited by RHDC to visit

Andiwadi village to have a direct dialogue with expecting & new mothers of the village. Since we felt

it would be more useful to visit one of the ICDS project, we decided to do the same also.

PURPOSE OF THE VISIT:

To have a direct dialogue with expecting & nursing mothers of Andiwadi & Kothagondapalli

l.

villages.

To visit an ICDS project to have a brief situational picture on nutritional & health status of the

2.

attending children.

To define & expand the exact nature of collaboration between CHC & RHDC of TVS factory for

3,

future works.

To collect demographic data & other data, deemed necessary for future activities.

4.

THE VISIT PROPER:

We, Mr.Chander & Dr.Vinay, the representing team members from CHC had a preparatory

discussion1 with Dr.Thelma Narayan before embarking on the visit.. We first met Dr.Rajan Babu, the

Chief-Medical-Officer & person-in-charge of RHD of TVS factory, who promised to send a formal

request for collaboration with CHC. Later, we visited the ICDS project in Kothagondapalli2 & had a

brief encounter with the staff & children. Lastly, we visited Andiwadi village along with three officers

of RHDC, where we had a very satisfying dialogue3 with expecting & nursing mothers of the above

mentioned villages.

OUTCOME:

1. Dr.Rajan Babu agreed to send a formal request for collaboration.

2. Data pertinent4 for future action in RHD for Andiwadi & Kothagondapalli villages collected.

3. Partly successful in establishing a meaningful working relationship with anganwadi workers &

mothers.

Z A very stimulating & informative discussion with the expecting & nursing mothers of both

villages.

CONCLUSION:

Though we were partly successful in carrying out the objectives of the visit in general, we felt there is

a need for defining exactly the nature, scope & terms of collaboration at the earliest; to have a

meaningful & fruitful partnership.

1 Annexure No. 1

2 Details of visit in annexure no.2

3 Details of visit in annexure no.3

4 Annexure no.4

,

ANNEXURE NO 1

PREPARATORY DISCUSSION WITH Dr.THELMA NAP-AYAN

A very iusiguuiil discussion with Dr.Thelma Narayan, ior whicuDr, vmay arrived laic, during which she

eave us anoverview of what should be our focus during the visit & oriented us towards the exact job at

kcn/i tka avow

u-*** v<*rious data to be collected stressed on the need for forma!

agreement & imponance of establishing a good rappon with concerned people. She also cautioned us

about carefully selecting the method of pedagogy, appropriate to the group The discussion gave ns that

IICDS PROJECT

Kothagondapalli, a village, is a 10 min drive from TVS Factory, where RHDC of TVS has been working

iu various capacities since 1954.

OBSERVATIONS:

1 The anganawadi is housed within the campus of Government school with a separate room &

kitchen to itself.

9 The hnildino as a whole was constructed hv the Government The ‘nnliftino’ in terms of naintinv

maintenance, toilet provision, gardening, enclosure construction <5c maintenance of play Helu is

undertaken by RHDC.

4. The anganawadi was spacious, cieaniy maintained with a separate, ciean kitchen with a gobar gas

fuelled stnve for cookino

j.

lucre was enougn space ror cmiuren to p>ay witmn tne room, aioert witnout enougn toys.

6. There is afiess to drinkma water & clean toilet.

*7

Tknro tvoc o Irvxvr o4*A*»z4«>r*AA rxT

r>-P "2 -C r\r»1xr 0/1 tvnrc

fQOCOri rrirrf^n

was me famess of me anganawadi from Their houses.Chiidren present at me time of visit were

reasonably healthy & most of them were well nourished However there were a few malnourished

vmjLuicil{ iuCiv iS a iict-u jlvi a uGiaiiou Stuuy vi uuc Same Wuivu WaS pvSipvucu due tv lavK vi

time).

C

TKa

kointy

woo

vAtv

All At»UrlrAv» WArA mor^A +q xirock 4iA,'r T»o*»i4c

& say meir prayer before being served food, with each chiid gening a separate piate for eating.

The children seemed more than ready to cooperate with a stranger & happily submitted themselves

ior vAdiiufiduun oy Dr. vinay.

10. The staff members were cooperative & friendly with us. They' seemed very well informed about

their duties & seemed to be doing the same reas onab ly well. They also seemed to be genuinely

interested in meir work. They aiso reported enough support from Government in terms of supply

of food # medicines

Various lunctioiis pcrlormcu by the stall as told by thein are as lollowsi

> Nutritional supplementation to all children in the age group of 0-6 years & all expecting &

lactating mothem r^,he'*z also followed differential Quantity as prescribed by the authorities

ANC for expecting mothers including tetanus immunization every 2nd Monday of the

month with help of visiting ANM.

0

r Imnmmzaiioii of all cliildieu. as prescribed by authorities, on every 2nd Wednesday of the

month with heln of visiting ANM.

> Distribution of IFA tablets’ to expecting mothers & all girls between 11-19 years,

administration of Vitamin-A to ail children at 6 months of age & then 2mi every 6 months

til! 5 years of age,distribution of paracetamol, albendazole A clotrimazole to people in

need.

>

j»

>

>

z-

Referral services for sick people.

Health education to all women between 15-45 ’’ears

Non-formai education to all children between 2-6 years of age.

Periodic meetings with women, adolescent girls & with village lemslative council.

ivlaiuiciiuiive 01 icCOfuS luCiiiuiiig gi'OWiu iiluiiituiuig, geiicial health 01 children &

performing ^nsex duty.

1iX.

1 livovrvi, CUV LjllXim^ UVAVVV -iron

>>UU iUo

CUV UlUVlllV; V»X VXXK/ OVUll

o^nrfc VI MUIrUvvr.

111U111U1111 U.1VXWA VUU1W

yUJUUl ^JUL, "V

dmy so imponam, due to acute shortage in the suppiy of growth chans by ihegovemmenti

1? The efaff WAS enthusiastic in fiirther imnrnvemente of the ancanawadi in general A readv to nive.

ilcip ui wnaievci way uiey Can.

IMPRESSION:

before any improvements are suggested.

ANNEXURE N0.3

THE D1AL0UGE PROCESS AT ^NDIWADI WITH EXPECTING & NURSING MOTHERS OF

BOTH VTT.T AGP.S

expecting & nursing mothers of above mentioned two villages. The meeting was arranged by RHDC &

piace in the beaurifui cl secure anganawadi of Andiwadi viiiage.

The dialogue was held in a very informal manner, with the participants and resource persons mingling

a planting planted m wilderness & not cared! It helped to break the ice & also gave the woman an ideal

platform to start the dialogue. Then on the dialogue continued with good participation & some of the

observations as made by Dr.Vinay are as follows:

1 The participating group was a good mixture, of woman from different economic levels, though it

Caiiuvt v© Said SO vf uldi SOCial vlaSS.

2. Only 2-3 participants were very active & others answered only when questioned. 1'here was not

3. me coordinator was articulate, expressive & tactful, stimulating the women to think & participate.

4. The knowledge of most of the participants regarding child health &. rearing was commendable.

the effectiveness of dialogue):

> Mr.SJC: Why should you feed children?

Women: “To fill stomach; io help in growih;io maintain health of the children".

> Mr.SJC: When should breast feeding started? Weaning-When & how?

W omen. BF just after the birth; no prclactcal feeds to be given; Weening to start in 3-6 months

Withragi porridge & other soft foods; confusion among the group regarding marketed baby foods

& on informing^ by US, that they era not necec<;ary, one even questioned US bv askinn how crane

then that the doctor prescribes it?; most said they have never bottle fed their babies!

> Mr.SJC.' Tmmnnization-When. T-Tow many?

Women: Most of them knew of Ol’V, BCG, DPT, but not many knew of Measles vaccine. Also

they were ignorant of number of doses of each & tlie disease agamst which different vaccines were

health.

Mr.SJC: What are their ‘unmet needs’?

women:!. v>my rice not cnongu, varictj

2. Need more playthings.

4. Make ‘baiawadi’ attractive to children, so that they ‘love’ to come there.

> Mr.SJC: Why do they think some children are not attending anganawadi?

make their children dirty'1; some fear that there will be sharing of plates; distance problem;

Mr.SJC: Any other significant problem they wanted to discuss?

Women: Most of them strongly felt something is needed to he done to children of coolies, as the

anganawadi closes till then parents return home from their work.

Women: rood; preschool- so that their children become smart; to see that ‘headache" is transferred

to someone else for atlcast sometime!

Women: (Alter some minutes of silence) “You give the suggestions

then we will see how we

IMPRE S SIGN:

most important being the dangerous misconception of Govt, supplied ‘supplementary nutrition1 as a

‘replacement’ to

nutrition^ which TTiakes the basic objective of IGOS ^h^mp nf Snmnwinv child

nutrition", a distant dream. Also there is need io further the health knowledge or mothers regarding doses

of immunization & other aspects of child care. It seems necessary to consider how best can we make

conveniently overlooked is ‘the street children1 problem, it is an emergency problem which needs to be

addressed on a war fooling. Also it is pertinent for us to now evolve a strategy for effective 6comm»miiy

participation’ if we aic to make Rural Health Development a reality.

( (SX5J- -

.

4

f

L,

!&>'

?O^q\dS1^Y|

W^OkRFWG

CSLUCWD

Tokd

Va^UtK

"WUDfcEN

f4ki<3

0-(>w ’|~ram

Co-t'i]

^Q^faxc^YY<S^(JoUi

MAW<kdi

V°>G3>

3<50.' IO\3

\<Al

IW '153

|J-gArn

35-36™

<?3h

A US

® BoVVi

\fiJdxx.^y>

Wxie pBtc'DS-E.

W

•2:Q

lx>

W <w4> \hkta(^

\y)

Ph^ecfc

xmAc.ts

•

SEX

R fillO IN WTLWEn

6-6-4

O~(jCD

7-I6<y>

fj-36w

.jf-Sfcrn Su-t-j

.Arte

*Qrt

<iNG

11

13

6

3

liv-iao

’

2Q

AGOtfT WE iOS

®?^ese^)u^

JFWOW £ mHAGO^-DAVALUl

PW\

Mndkhkwe/n

1 ecn^^di

>

T7-

S'-5

j:5

131

- 36'.IQ

a&'33

PROTECTS

^MehwoerJi

VnVU U

93-’5t

a

o^T-N.

^n^acG

^vOpo^oA

nejQjA ^ufa^e.

® sta^ ■-

Kofaa^oYicRfolU

}>A^6voawacLi

AnrbvJadA

SoGmm >

C?e»xm&i

$ Hhi.Ual^na

fc. t1«5 )'

. 3a^ftwwa

^•Ah0|-

S- 6.9.051 M

(ji Oy\YA$nfop

A V\hK . Io^Iqm rr>i

Mli3G| ~

P..1U36/-

b) tta • fk>\Vx

o) Y\wi.\)o.'ft<w)W

p,- LUof'

t-bA • Se.4Va

ftAUO|~

$)M to

OBStRvAW >

The^e

tW'^'fauX,

is a

c^cLime

Vn

g-^tWd

o-W^l^ W>khv>C^ M(WiO

M cKU^.f.TV,^ u a

CAHSe

>

fogin

fcfK w

d^dHve

fa)

Co^tfc/-

^XvoIjqy),

9sn,

SRINIVASAN SERVICES TRUST

Jayalakshmi Estate, No.8, Haddows Road, Nungambakkam, Chennai -6

30.11.2004

To

Dr. Thelma Narayanan,

Community Health Cell - CHC

No. 367, Srinivasa Nilaya,

Jakkasandra I Main, I Block,

Koramangala,

Bangalore - 560 034.

Ph : 25531518(080)

Sub : Nutrition Programme for 5 Villages.

Dear Dr,

In continuation of discussing we had with Mr. Chandar & Dr. Vinay on the above subject

we would request you to assess under 5 children and conduct Nutritional Programmes

for the following 5 Villages. We would also request you to send the outline of the program

and the cost involved.

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

Kothakondapalli

Bommandapalli

Bathalapalli

Andivadi

Belagondapalli

Expecting an early reply.

Ref: CHC/2004/

10nd December 2004

Dr. A. Rajan Babu,

Chief Medical Officer,

Srinivasan Services Trust,

Jayalakshmi Estate, No.7,

Haddows Road,

Nungambakkam,

Chennai 6

Dear Dr. Rajan Babu,

Thank you for your letter. I have been on leave due to the serious illness of my

father and hence the delay in replying.

We are also currently busy with a training programme and with preparations

for a National Public Hearing on the right to health care being jointly organized

by the NHRC and the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan during mid- December in Delhi.

We would be able to assist you in January 2005. Dr.Vinay is presently in

Gadchiroli in Maharashtra and will be back in the last week of December 2004.

From a community health perspective it is better for your team with the local

health workers to conduct the nutritional programmes yourselves. We could

conduct the survey along with your team so that local skill development takes

place. We could assist in the process of participatory planning, implementation

and review of the nutrition intervention. Baseline and later measurements

would help the community to know if there is any impact following introduction

of the intervention.

We will keep in touch with you in this regard.

With best wishes,

Yours Sincerely,

For Community Health Cell

Thelma Narayan

Co-ordinator

k

P.S : Enclosed is a copy of the Peoples Charter on HIV/AIDS launched by

the Peoples Health Movement at the International AIDS Conference in

Bangkok in July 2004. Enclosed also is a Arogya Kalajatha Book of

songs on health issues. It also has a kannada translation of the AIDS

charter.

DFA

Report on field visit to Kothakondapalli. proaarmme bv TVS

Dr. Rajan Babu the chief medical officer and Mr.Kamalakanna the social welfare

officer of TVS company in Hosur visited Community Health Cell on 13th July 2004.

They requested for the support of CHC in addressing the problems pertaining to

nutrition and environmental and personal hygiene among the people in the villages

where the company is working.

The Community Health Cell team consisting of;

1.

Ms. Pamasini Asuri,

2.

S.J.Chander.

3.

Prasanna Saligram

Visited Kothakondapalli villages near TVS Company in for assessing the nutrition

programme on 22nd July 2004. We are given to understand that TVS Company is

working in six villages around the TVS Company where government is implementing

the ICDS Progarmme.

TVS Company is organizing self-help groups in all these

villages. These self-help groups make chapathis and supply them to TVS Company's

canteen.

According the filed worker Mr. Gangadharaiah, he collects information

regarding the children's nutritional status from the anganawadi centers and given to

the company.

The team was accompanied by Mr.Ganngadhariah to Kothakondapalli as he could

not give satisfactory answers to CHC team members, Dr. Rajan Babu was requested

to come to the field to provide information regarding the prevailing situation. Before

Dr. Rajan Babu could arrive the village the team had interacted with the anganawadi

worker and also reviewed the records used for growth monitoring. According to Mr.

Gangadharaiah; "there are no malnourished children. However, all the children were

within I & II Degree"

During our visit, 30 out of 35 children were present at the anganawadi center. The

scale against, which the children weighed used, by the ICDS Programme in Tamil

Nadu does not contain source and basis. According the CHC team there Is errors In

the scale for example a child born with 2.5 kgs of birth weight should gain 9kgs of

weight at three months, according to the scale 7.5 kgs as acceptable. The

1

supplementary feeding powder packet supplied by the government does not reveal

what it contains for example wheat/corn, it is difficult to infer if it contains wheat or

com.

According to our observation all children seemed undernourished and running low

temperatures. It was suooested to have a health check up and monitor the children

for general health problems. The anganawadi worker and the filed staff of TVS are

unable to interpret the data that they have documented regarding children's growth

monitoring.

It was suggested to check for helminthes infection and assess types of food children

get at home and its quantity in order to overcome calorie gap in diet intake both at

home and ICDS center. This is important for preventing brain damage, which could

occur during the first 11/2 years of the child's life, as it is difficult to repair later. It

appears that the children are not weighed regularly on monthly basis. The food

supply during the week to children, during the week the menu seems to be

satisfactory and its effect is not documented therefore it is difficult to asses.

It was suggested that not to depend on weight for age indicator alone for measuring

the weight for children as a child suffering from mild kwashiorkor could also show an

increase in weight.

It was suggested to make a follow up plan for children in two categories separately;

one for children below two years and children above two years. This is important to

understand the foilwing matters; food habits at home; the quantity of food given its

quality and how much is consumed; who normally feeds child and how the family

assesses the growth of a child for planning. There might exist misconception

regarding diet given to children, which must be identified and addressed.

It would be helpful if medical examination and weighing is done once in two months

for all children under two years for assessing their general decease pattern and

monitoring the growth. Finally it was suggested to involve mothers among the group

by training them and involve them for creating awareness and support the

programme on day-to-day basis.

2

&

-

nxv *1

••J

*

VI x^MvaiVivX* diIU

Environment hygiene. (Villages covered by TVS, Haritas at Hosur)

Dr .Rajan Babu and Mr. Kamalakannan of TVS came to Community Health Cell on

22ndly July and 27th August 2004 to request to help them in addressing the problem of

Nutrition and environmental hygiene. During the discussion it was discussed and agreed

that a collective process would be evolved with the community than implementing a

project to address the problem. Therefore the following visits were proposed to have

dialogues with the various groups were necessary.

CHC team members have made three visits so far to Asses the situation. The first visit

was made by a team of three people consisting of Ms. Padmasini Asuri Nutrition expert,

Mr. SJ.Chander Community Health and Sociology background and Mr.Prasanna

Communication background. Following were the observation made during the visit. The

first visit was made to Kothakondapalli anganwadi centre. The team had a dialogue with

the Anganwadi worker, Dr. Rajan Babu and Mr. Gangadharappa of TVS. The children

appeared sickly, running low-grade temperature. It was observed that the chart used for

recording the weight of the children is misleading in categorizing the grades of

malnutrition as the chart was shows less weight for the age.

During the second visit, the CHC team members had in interaction with the anganwadi

workers. All the anganwaid workers for the six centers were present for the meeting.

Couples of ayahs were also present. All of them expressed their willingness to work

together in addressing the nutrition problems of children. They are demotivated by lack

of supportive supervision and cooperation from their superiors. They expressed their

dissatisfaction over their salaries. They said they are made to work more for less salary.

Their knowledge on nutrition seems satisfactory; however an assessment would be

helpful before conducting the training programme for fine-tuning their knowledge and

skills. Without motivating the anganwadi workers, improving the infrastructure facilities

would not make much impact on the health and nutrition status of children.

The third was made to interact with the mothers. Eight mothers were present for the

discussion from three villages

In'1? • ‘

’ ’’

’••••"> >- --

nutritional needs of their ehildren adequately, later when probed they expressed that there

is a problem with the poor families where both the parents are working as coolies.

Childcare is a problem after anganwadi center as the children are left on the street or left

to care of the elderly until their parents return from work. It was reported that many of the

poor families arc unable to provide adequate food for their children.

The mothers

nuBundorBland that the food given al the anganwadi center is adequate, they do not know

it is only a supplementation. The angawadi teachers expressed absenteeism as a problem.

They said the following are the reasons; children want to be free, do not want to be

confined within four wall, no toys and distance. They said malting available more toys

and improve the quality food could attract more children. It was observed that there were

more boys than girls in (he register, we wonder if there is a problem of sex ratio.

Physical structure of anganwadi centers is excellent TVS has helped in providing toilet

and water facilities, they are also providing biogas facilities for cooking. The surrounding

of the villages appeared untidy. There is a need to work with the village leaders and if

there are any village level committees.

It is not clear, what is the extent of the problem of nutrition. Therefore it is suggested that

a sample survey may be necessary. It would also be helpful to assess the knowledge

attitude and skills of andganwadi workers and mothers.

Anganwadi workers told us that they regularly monitor the growth of children. However

it would be helpful do an assessment of a small sample to know how well growth

monitoring is done.

PROTECT PROPOSAL FOR NUTRITINAL STATUS OF CHILDREN (0-6YEARS) IN

6 VILLAGES IN HOSUR TALUKA

AIM: Assessment of nutritional status of children between 0-6 years of age in 6 villages

of Hosur taluka of Krishnagiri district of Tamilnadu state & to plan & enable measures

to mitigate malnutrition in children & to promote the development of children & ensure

them a healthy childhood.

OBJECTIVES:

■

■

■

To assess the nutritional status of children aged 0-6 years in 6 villages of Hosur

taluka where health division of Community Development department of TVS

Motors (TVSM) is working.

To identify the various factors; social, economical, political, educational &

cultural; that affect the nutritional status of the children in that area.

To plan & enable the local community & Community Development department

of TVSM to take collective action to adapt & maintain rational & appropriate

nutritional practices of the children to restore their nutritional status to normalcy

& maintain the same.

THE PROCESS:

The whole project will be taken in two phases:

1.

Assessment phase including collection & analysis of child nutrition data &

2.

Post assessment action phase includes evolving a plan to enable the local

community & health division of Community Development department of TVSE

to take collective action to adapt & maintain rational & appropriate nutritional

practices of the children.

ASSESSMENT PHASE:

It includes the following processes:

* An action based & participatory community approach will be the guiding

principle for the whole process. Meeting the local people & building working

relationship with them will be the first step of the project. Local people includes

the staff at health division of Community Development department of TVS

Motors, the community leaders of all 6 villages, representatives from parents,

women, men, children & elderly groups of the community, the anganwadi

workers & ANMs of the area. The meeting would serve as a place to:

o Know the willingness of the community to participate in the project

o Inform & discuss, with all parties involved, the objectives & methodology

of the project

o To understand & build rapport with the community

o To involve every stake holder in decision making process

o To finalize the logistics of the assessment phase of the project

To collect past records, whatever is available, regarding the health status

of the children in the community

o To build a causal model of malnutrition

Methodology used for the assessment of nutritional status of the children would

be a 'cross sectional study' of all the children through house to house visits &

recording their weight using Salter scale & height (for children >2 years)/length

(for children <2 years) using fibre glass scale/infantometer. The data will be

collected with the involvement of the local people. The data collected will be

collated with the past records of the children to assess the nutritional status. The

NCHS values for weight & height of children, as recommended by WHO, will be

used as the reference values to draw inferences.

In addition, based on the causal model of malnutrition, a questionnaire designed

to study the various factors; social, economical, political & cultural; that affect the

nutritional status of the children in that area will be administered to a

representative sample of the different groups in the community.

The process will be designed & implemented with full participation of the local

people. The community will be asked on how best can we involve them in the

process (& also will be asked to provide 2 volunteers in each village for the entire

process to move forward. Then, the volunteers will be involved in a discussion

where the whole process of the project will be discussed with them & their needs

identified. In addition, their inputs will be incorporated in the design of the

questionnaire. A training program to build capacity of the volunteers to

undertake the project themselves will be planned.)

o

■

■

■

COMPONENTS OF THE ASSESSMENT PHASE:

1.

Meeting with the local people: Meetings will be held with local communities &

staff members of RHDC of TVSE with the objectives mentioned earlier. Also,

these meetings will be made participatory & will be used to serve the following

requirements:

■ Build a team within these villages to assist us in the project. In addition,

capacity building of the same to be undertaken during the process of

project execution to enable them to continue the work in future

■ Construct a simple & functional

hypothetical causal model of

malnutrition

2.

Collection of vital statistics: It is important to have a general picture of the

community in which a health program is being planned. Apart from helping us

in providing on the demographic profile of the region & an approximate number

in the target group (children of 0-6 years), it also helps in giving a broader

picture of the overall health status of the children in the region. RHDC can obtain

the same from the local governmental authorities. The data deemed pertinent for

the project are number of children in 0-6 year age group, sex ratio in the same

age group, IMR, 1-4 mortality rate, vaccination coverage, life expectancy of the

area, spacing of the child birth, details of families with 0-6 year old children &

any other deemed necessary during actual process.

3.

Collection of previous records of the children: Such as growth charts, birth

certificates, under 5 health records, records from pre primary child care centres &c.

any other records pertaining to the health of the children under study.

4.

Clinical examination: Clinical examination of all the children to search for

specific signs of malnutrition to be carried out. The specific signs of malnutrition

that will be looked in each child will be as follows:

• Hairs: Sparse, thin, easy pluck ability, hypo pigmentation, without sheen,

flag sign

• Eyes: Dry eyes, Bitot's spots, keratomalacia, xeropthalmia, pallor

• Tongue & mouth: Sore, red & glazed tongue; cheilosis; pallor

• Skin: Erythema, Hyper pigmentation, raw hypo pigmentation; easy

bruisability; dry, inelastic & mosaic skin; phrynoderma

• General appearance: Wasted muscles & bony prominences; no fat under

the skin; protuberant abdomen; generally apathetic or highly irritable

child; child which has stopped feeding; oedema;

5.

Anthropometric measurements: The height & weight of each child is to be

measured & then weight for age (under weight), weight for height/ weight for

length (acute malnutrition) & height for age/ length for age will be calculated for

a sample of children. The age of the child in question will be assessed according

to the data in birth record or if no such data is available using the local calendar

or an approximate age is calculated using the clinical examination. All

measurements are to be obtained under standard conditions using standard

equipment & standard techniques. The NCHS values of height & weight for age

in children will be used as reference values to draw conclusions. The same will

be recorded on a growth chart & the importance of maintaining the same in

future will be stressed. If previous records of weight & height are available, the

same will be collated with the current measurements to know the trend of

nutritional status & to identify the 'at risk age', if any, in the community.

Community survey: Once a simple & functional causal model of malnutrition is

built & major determinants for the cause of malnutrition identified, analysis of

the data will be taken up & priority areas for intervention will be identified.

A period of one month is envisaged to be the time period to carry out all the above

activities. Once, the above process is over, the project moves into the post- assessment

action phase.

6.

PROJECT PROPOSAL FOR NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF CHILDREN IN 6

VILLAGES IN COLLOBORATION WITH RHDC OF TVSE FACTORY IN HOSUR

AIM: Assessment of nutritional status of children between 0-6 years of age in 6 villages of

Hosur taluka & to plan & enable measures to mitigate malnutrition in children, if it is

prevalent, & to promote the adequate development of children & ensure them a healthy

childhood.

OBJECTIVES:

■

■

■

To map out the magnitude of the burden of malnutrition as a health ptoblem in

children between 0-6 years of age in 6 villages of Hosur taluka.

To identify the various factors; social, economical, political & cultural; that affect the

nutritional status of the children in that area.

To plan & enable the local community & RHDC of TVSE to take collective action to

adapt & maintain rational & appropriate feeding practices of the children to restore

their nutritional status to normalcy & maintain the same.

THE PROCESS:

For the sake of convenience, the whole project will be taken in two phases:

1. Assessment phase

2. Post assessment action phase includes analysis of the data collected during the

assessment phase & evolving a plan to enable the local community & RHDC of

TVSE to take collective action to adapt & maintain rational & appropriate feeding

practices of the children.

ASSESSMENT PHASE:

It includes the following processes:

■ Meeting the local people & building working relationship with them. Local people

includes the staff at RHDC of TVSE, the community leaders of all 6 villages,

representatives from parents, women, men, children & elderly groups of the

community, the anganwadi workers & ANMs of the area. The meeting would serve

as a place to:

o Know the willingness of the community to participate in the project

o Inform & discuss, with all parties involved, the objectives & methodology of

the project

o To understand & build rapport with the community

o To involve every stake holder in decision making process

o To finalize the logistics of the assessment phase of the project

o To collect past records, whatever is available, regarding the health status of

the children in the community

o To build a hypothetical causal model of malnutrition

■ Methodology used for the assessment of nutritional status of the children would be

a 'cross sectional study' of all the children through house to house visits & recording

their weight using

height (for children >2 years)/length (for children <2

years) using

. The data will be collected with the involvement of the local

people. The data collected will be collated with the past records of the children to

■

■

assess the nutritional status. The WHO/ICMR values of height & weight for age in

children will be used as reference values to draw conclusions.

In addition, based on the hypothetical model of malnutrition, a questionnaire

designed to study the various factors; social, economical, political & cultural; that

affect the nutritional status of the children in that area will be administered to a

representative sample of the different groups in the community.

The process will be designed & implemented with full participation of the local

people. The community will be asked on how best can we involve them in the

process (& also will be asked to provide 2 volunteers in each village for the entire

process to move forward. Then, the volunteers will be involved in a discussion

where the whole process of the project will be discussed with them & their needs

identified. In addition, their inputs will be incorporated in the design of the

questionnaire. A training program to build capacity of the volunteers to undertake

the project themselves will be planned.)

COMPONENTS OF THE ASSESSMENT PHASE:

1. Meeting with the local people: Meetings will be held with local communities &

staff members of RHDC of TVSE with the objectives mentioned earlier. Also, these

meetings will be made participatory & will be used to serve the following

requirements:

■ Build a team within these villages to assist us in the project. In addition,

capacity building of the same to be undertaken during the process of project

execution to enable them to continue the work in future

■ Construct a simple & functional hypothetical causal model of malnutrition

2. Collection of vital statistics: It is important to have a general picture of the

community in which a health program is being planned. Apart from helping us in

providing on the demographic profile of the region & an approximate number in the

target group (children of 0-6 years), it also helps in giving a broader picture of the

overall health status of the children in the region. RHDC can obtain the same from

the local governmental authorities. The data deemed pertinent for the project are

number of children in 0-6 year age group, sex ratio in the same age group, IMR, 1-4

mortality rate, vaccination coverage, life expectancy of the area, spacing of the child

birth & any other deemed necessary during actual process.

3.

Collection of previous records of the children: Such as growth charts, birth

certificates, under 5 health records & any other records pertaining to the health of

the children under study.

4.

Clinical examination: Clinical examination of all the children to search for specific

signs of malnutrition to be carried out. The specific signs of malnutrition that will be

looked in each child will be as follows:

•

•

•

•

•

Hairs: Sparse, thin, easy pluck ability, hypo pigmentation, without sheen, flag

sign

Eyes: Dry eyes, Bitot's spots, keratomalacia, xeropthalmia, pallor

Tongue & mouth: Sore, red & glazed tongue; cheilosis; pallor

Skin: Erythema, Hyper pigmentation, raw hypo pigmentation; easy

bruisability; dry, inelastic & mosaic skin; phrynoderma

General appearance: Wasted muscles & bony prominences; no fat under the

skin; protuberant abdomen; generally apathetic or highly irritable child; child

which has stopped feeding; oedema;

5.

Anthropometric measurements: The height & weight of each child is to be

measured & then weight for age (under weight), weight for height/ weight for

length (acute malnutrition) & height for age/ length for age (chronic malnutrition) ?

should this also be used to children>2 years? will be calculated for each child. The

age of the child in question will be assessed according to the data in birth record or if

no such data is available using the local calendar or an approximate age is calculated

using the clinical examination. All measurements are to be obtained under standard

conditions using standard equipment & standard techniques. The WHO/ICMR

values of height & weight for age in children will be used as reference values to

draw conclusions. The same will be recorded on a growth chart & the importance of

maintaining the same in future will be stressed. If previous records of weight &

height Eire available, the same will be collated with the current measurements to

know the trend of nutritional status & to identify the 'at risk age', if any, in the

community.

6.

Community survey: Once a simple & functional hypothetical causal model of

malnutrition is built & major determinants for the cause of malnutrition identified,

a questionnaire will be designed to study the identified factors; social, economical,

political & cultural; & will be administered to a representative sample of the

different groups in the community with the help of local people.

A period of one month is envisaged to be the time period to carry out all the above

activities. Once, the above process is over, the project moves into the post- assessment

action phase.

Report of visit to TVS community development project in Hosur

On 7lh March 2005 a meeting was held with the anganwadi workers working in the

following five villages; Andhivadi, Kothakondapalli, Romandapalli, Relakondapalli and

Bathalapalli to finalize the nutritional assessment of under five children. The anganwadi

workers clearly indicated that they are de motivated to work as they are paid a very

meager salary (honorarium) they said they are not doing their work as per the conceptual

framework given by the Integrated Child Development Services project. They said if

TVS considers providing them some support it would motivate them to collaborate with

the initiative of TVS in improving the health and nutritional status of children. They did

not say this as a condition.

Regarding areas of concern for improving the anganwadi centers they said many children

are going to private nursery schools and others not motivated to come to the center. For

this they said, if TVS could help in providing additional supplementary food like the

government gives an egg on Thursdays and the attendance goes high on Thursdays. They

also said if they children could be provided with uniform it will motivate the parents

sending their children to private nursery schools to send them to the anganwadi centers.

On 19,h March 2005 it was decided to start the assessment at Kothakondapalli and it was

communicated to Dr.Rajanbabu of the Chief Medical Officer of TVS. When we went to

Kothakondapalli on 18U1 at 9 am. there were only four children in the center. We waited

there for the teacher and the ayah to come, at about 10 am the ayah came with a basin full

of cow dung for the Gobargass plant installed for the cooking. The ayah said the teacher

had gone for a meeting and she would not be coming. She was busy cutting the

vegetables for the food that she was planning to cook and the children were playing on

their own in the center. Few mothers and relatives of the children came there to drop the

children.

We started the assessment at about 10 am and could not continue after assessing about 10

children, as wc could not elicit the information about the name of children and their

mothers and also their date of births. Since we had to leave these columns incomplete we

decided to stop the assessment and planned to continue when the anganwadi teachers was

there and their parents were informed. We met the self-help group members of TVS and

explained to them about the proposed nutritional interventional plans. They said they

would support the initiative. Some of them said that their children are also in the

anganwadi and they were not happy with the way the anganwadi center is functioning as

their children not taught well and taken care. After meeting the self-help group members

we went to Bomnadapalli, there were about 15 children in the aganwadi and the ayah was

busy cooking the food. Here too the anganwadi teachers had gone for the meeting. We

went to meet the panchayt president’s house to seek his support. Mr. Srinivas Reddy was

not there but his family members said they would convey the message to him and gave us

his phone number to talk to him. We met the self-help group leader Ms. Prema and two

other women, they said they would support the initiative planned by TVS. During the

afternoon we had meeting with Dr. Dhakshinamoorthy, he said we had to assess all the

children under five years of age, which was contrary to the plans that we had. We had

decided to assess all the children who are coming to aganwasdi and assess about 20% of

the children who are not coining to the center. We told him if we have to consider

assessing all the under five children, we need to revise our budget. We also told him that

we will only assess the nutritional status and build the capacity of mothers, self help

group members, anganwadi workers and TVS staff we will not do the intervention alone

for TVS. We also discussed the concern of the aganwadi workers and appointing a

female health staff by TVS. Dr. Dhakshinamoorthy said that TVS will not consider

appointing such a person and regarding the grievance of the anganwadi workers, he said

TVS would not consider offering any support to them too. He suggested that we could

have planned their support as part of their budget. Later he took us to Kothakonda palli

and Belagondapalli to meet the key informant in the village and to identify the places

where we could establish the assessment centers in the village. After this he dropped at

the Hosur bus station at 5 pm.

Ref: CHC/2005^

June 13, 2005

Ms. Padmasini Asuri

Nutrition, consultant

Jayanagar,

Bangalore

Dear Madam,

Greetings from Community Health Cell!

You have been supporting our nutrition intervention for the Community Development

Programme of TVS Motor Company in Hosur during the past few months. Your support

is highly appreciated both by CHC and TVS Motor Company. I would like to request

you to continue to support in planning and implementing appropriate intervention based

on the finding of the recent assessment carried out in five villages. The next meeting with

all the anganwadi workers, CDPO and TVS staff is planned for 20th June,2005 at. 2.00

pm, at Community Health Cell. Kindly facilitate the discussion and planning process. We

shall make arrangement for you conveyance.

With warm regards

Yours sincerely

^STChander

For Community Health Cell

Field Training Coordinator

Ref; CHCpoy05

8th August,2005

Dr. Rajan Babu

Srinivasan Services Trust

Jayalakshmi Estate

No.8, Haddows Road

Nungambakkam

Chennai - 600 006

Dear Sir

Greeting from Community Health Cell

Subject: Partial payment for our services towards nutrition intervention project.

Please find furnished below the details of our service charges towards the nutrition

intervention project of TVS Company in five villages in Hosur taluk.

Sl.No

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Description of cost

Resource fee for the preliminary visits for 7 days

for two people @ Rs. 1000 for one person and Rs.

500 for another person.

Equipment for measuring height and weight

Travel during the assessment phase

For 20 days @ Rs. 400 per visit for two people

Resource fee during assessment phase

@ Rs. 500 for one person and Rs. 300 for another

person

cko-W

Total

<

(Rupees thirty nine thousand five hundred only)

With regards

Yours sincerely

ftfChander

For Communty Health Cell.

Total

Rs. 10,500.00

Rs. 5,000.00

Rs. 8.000.00

Rs. 16.000.00

Rs. 39,500.00

Budget for Nutritional assessment and intervention in five villages'TJ^ZE^it

SI. No

1.

2.

3.

4.

Description of cost

Preliminary visits

7 visits by two resource person

@Rs. 1000 per one person and Rs.500.00 per another

person 7X1500.00= Rs. 10, 500.00

Resource charges during intervention phase

For 24 days two visits in month by two people @Rs.I500

per visit 24X1500= Rs.36.000.00

Printing and stationery

Equipment for measuring height and weight of children

Travel

During assessment Phase

For 20 days @ Rs. 400.00 per visit for 2 people

400X20

During intervention phase

@Rs.4OO per visit for two people for 24 days

Rs.400X24 = Rs.

Total

Rs. 10, 500.00 /

Rs. 36,000.00

Rs.

Rs.

5,000.00

5,000.00 J

Rs.

8,000.00

Rs.

9,600.00

Rs.

4,000.00

5.

Training programme

Two one day training programmes

@ Rs. 2000.00 per day

Rs.2x2000= 4,000.00

Total

(Rupees seventy eight thousand one hundred only)

Rs. 78,100.00

.

lrb&!

-*

Technical Comments on the activities of ICDS

programme support from TVS Medical Unit Hosur.

This comment has been written after a single visit to the Anganwadi

center of Government of TN that has the support of TVS unit at Hosur.

Hence it is limited to what had been observed at the time of visit.

The Situation:

The village Kothaguntapalli is about few kms from Hosur Factory. The

Anganwadi is one the centres of ICDS. There was a teacher and an ayah

manning the children, A typical Anganwadi center with lackluster in

various aspects, this is attached to the primary school of the village.

There was a ‘Salter Scale ‘ hanging in the middle of the room, (perhaps

to indicate that the center was an Anganwadi) There were about 25

children, out of enrolment 35. It was about a month since the centre had

been opened for the current year.

The strength of Anganwadi Positive points ;The Govt of TN had

provided the teacher with the chart which is almost a ready- reckoner for

the teacher to classify the children according to the nutritional status.

Naturally the teacher lacked in depth understanding of the purpose of the

chart, She merely records the wt and had mentioned that most of the

children were normal or in grade 1 Similarly the chart had been given for

the weight for the expectant mothers, who are also the beneficiary of the

centre. Both the charts did not show the reference standards. I could not

check the weight recorded as the register was not in the class. The fact

that an effort to help the teacher to record the weight, utilising the

figures provided in the chart shows the concern of the authorities.

The Ration given to the children as per the Governmental instruction is

as under

WEANING FOOD (as found on the label) Composition per 100 g.

Cereal (wheat/Maize/ Bajra------52 g

Ragi

----- 05 g

Bengal gram — 12 g

Jaggery

----- 30 g

Nutritional facts

per 100g Calories 350

Protein

8.5 g

The ration permitted of the ready mix to the children . The processed

powder is mixed with boiled and cooled water to make into laddoos

50 g ball for the under two yrs and 100 g balls for the above 2 yrs upto

5yrs. As soon as the children arrive the balls are sserved The under twos

have the laddos and return with the mothers while the anganwadi

children get the midday meal as well. The ration per child /day are

as Rice

80 g , dhall 10 g- oil 2 g In addition on Mondays

potatoes are given, Tuesdays Greengram Thursdays

1 egg while on

Wednesdays and Fridays no additional item is provided .

Through this meal as per the calculation the children get 290 calories

and 6.5 g Protein thus during the day with laddo and meal the

anganwadi children get in total 640 calories (RDA 1230 )

15 g Protein (RDA 25 g)

The food provided during the day gives about 50% of RDA and is quite

good. According to the ‘consultant’ of the team the normal status

children in the class is to the extent of 70-80% (!) But the Team had also

taken the wt of children who do not attend the anganwas\di class and the

wt recorded shows children with normal wt also to the extent of 75 %

What is the impact of the meal provided ?

My observations: The support given by the Government of TN in

providing a ready reckoner is a good start. But beyond this there were no

information whether the the children me given any vitamin /mineral

supplements. Whether the medical checkup was done or notwas not

known. The children looked rather weak and stunted in growth.Though it

is difficult to weigh the children of that age certain care need to be taken

during weight recording. Since we did not see any data of individual

child’s growth rate one does not know whether the normal child is on the

borderline or well above. There was no individual weight card. When the

children are getting the calorie gap filled in with the meal and laddoos,

there should be some difference between the anganwadi and nonanganwadi attending children. Weight alone is inadequate to rate the

child’s nutrtional status. Some of the standards, recommended

maintained in India and elsewhere are stated below.

Standards available to assess the nutritional status of the children :

On the recommendations of the WHO the standards of National Centre

for Health Statistics (NCHS)is the reference point recommended in

India. The median value of NCHS is taken as Indian reference standard

(copies enclosed) Normally the classification of nutritional status are

Ht for age wt for age as well as wt for ht.

1. According to Gomez standard the classification details are :

Normal

above 90% of Indian standard

I st degree mal-nutrition

75-90 %

II nd degree

60-75

III rd degree

<60 %

Reference is 50th centile

2 The Indian Academy of Pediatrics (LAP)

Normal

I st degree

II nd

III rd

Iv th

above 80%

70-80 %

60-70

50-60

< 50%

To confirm the nutritional status weight alone is inadequzte. Height for

age is also essential and weight for ht as well as wt for agegrefer to the

table) A proper medial checkup need to be done at the beginnng to check

for possible infection or infestation ,other factors that would inhibit the

absorption of the nutrients by the body,

With the average availability of 650 calories even the mal nourished

should be able to show some improvement and move up in the scale.

Since the teacher appears to be not so trained in the technical details

including the weighing of the child in the balance ,A-close observation

whether the children are eating what is served would give more

information about the children and the instruction received from their

mothers.

It is said that every child has the same growth potential if properly

nourished. It us thus necessary as not to accept lower standards as

“Indian “

4

With my handicap of limited information received on the spot, I make

the following suggestion for the TVS team who are graciously

supporting the Government’s effort in the area of child development

The suggestions are:

1. Check the scale used by the Anganwadi as the spring needs to be

strengthened.

2. Weigh the children individually as to wt for age ,measure the ht for

age with reference to the NCHS 50th centile (as per the chart) of

the Anganwadi group and record their status. Measurement of

arm-girth would be also useful if the doctors have the time. This

data of individual child , the team could keep in their office and

not share with the teacher till certain facts could be deduce

3

The teacher can continue her exercise. This can be corrected once

the doctors ares sure of the data. For this reason a close supervision

of the anganwadi school children need to be done’

As to their eating habits alertness and interest. A close observation of

children’s eating habit is required to find out whether they do get

their share and consume the food served. This one of the team

members can do continuously for a week or two during the meal

time The same person should make enquiries about the food that is

given by the mothers at home to compute the food availability for the

growing child

4.

Provide the medical check up for possible corrections if required

The children should be weighed periodically (once in three

months) to observe the growth during the period and also see the

difference between Anganwadi and outside.

6. To weigh the other children bathroom scale (platform type)

should be avoided..

7. Conduct under two advisory centers as this age is very crucial to

promote the potential growth factor in the child

8. To conduct this it should be considered as Health-nutrtion

education programme.

8.1

Select intelligent mothers and train them on few facts

of nourishment and health care of the under two yrs,

and make them as para- teachers/mother-teachers to

teach minimum of five mothers in their peer group,

5.

5

8.2

8.3

8.4

Conduct nutrition and health education classes to

give a holistic information on water,hygiene and food

requirements

The clinical classes should be a positive under two

Programme and not just cater to the sick children

alone. This would enable the mothers to a understand

and help in maintaining the weight chart as well as

provide possible adequate nourishment at home

Encourage the mother- teachers to participate and help

the anganwadi specially during meal time. This can

be done by the selected mother-teachers in turn

A comparative findings of local situation with that

of anganwadi will be useful for other areas

alsowhere anganwadi programme is executed. In TN

With time bound project the TVS team can show the way to

organize Under Twos in Anganwadi centres

The above activities are only a suggestion to improve the condition

of the children and the approach to anganwadi with TVS support.

0

D. HANUMANTHA RAO AND K. VIJAYARAGHAVAN

154

.155

TEXTBOOK OF HUMAN NUTRITION

Table 2: Median Values (50th percentile) Weight for Height for Boys and Girls

Table 1: Median Values (50th centUes) of Heights and Weights of

Boys and Giris (0-60 months) — NCHS

Height

(ems)

Ref: WHO. Measuring change in nutritional status. Guidelines for assessing the nutritional impel of

supplementary feeding programmes for vulnerable groups. WHO. Geneva. 198.1.

Expected Weight (kg)

Boys

Giris

Heighl

Expected Weight (kg)

<UnV

Boys

Girls

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

14.2

14.5

14.7

15.0

15.2

' 15.5

15.7

16.0

16.3

16.6

16.9

17.1

17.4

17.7

180

18.3

13.9

14.1

14.3

14 6

14.9

15.1 .

154

15.6

15.9

16.2

. 16.5

16.7

17.0

17.3

17.6

17.9

112

113.

114

115

116

117

1 18

119

120

121

122

19.3

19.6

20.0

' 20.3

20.7

21.1

21.4

21.8

22.2

22.6

23.0

J8.9

19.2

19.5

20.3

20.6

21 0

21.4

21.8

21 8

22.7

126

127

128

129

24.8

25.2

25.7

26.2

24 6

25.1

25.7

26.2

132

133

134

135

136

137

27.8

28.4

29.0

29 6

" 30.2

30.9

28 0

28-7

29.4

30.1

30.8

31.5

19.9

Kef: WHO Measuring change In nutritional status. Guidelines for assessing the nutritional impact of

tupplementary feeding programmes for vulnerable groups. WHO. Geneva, 1983.

GROWTH CHART - BOYS

156

TEXTBOOK OF HUMAN NUTRITION

(IAP-Clast®atlon - NCHS standards)

CLASSIFICATION OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Relatively speaking, weight, height and arm circumference have come to be considered

the most sensitive parameters for assessing nutritional status of under fives. Several

methods have been suggested for the classification of nutritional status ,based on these

measurements.

The anthropometric data can be expressed in a number of ways in relation to. refer- ■

ence data: (a) by the use of mean and standard deviation values, (b) by calculating per

centages of the median value of reference population which is assigned as 100 per cent,

and (c) by comparing with percentiles of the reference data, where median value is the

50th centile.

Weight for Age

Various methods have been suggested to classify children into various nutritional grades

using the body weights. The most widely used classification is the Gomez classification

(Gomez et al., 1956), in which the children are classified as having first, second or third

degree malnutrition if their weight for age is in the range of 75—90%, 60-75% or less

than 60% respectively of the reference median. All children whose weight is 90% and

above are categorised as normal. The selection of cut-off levels was based on the clini'cal/hospital experience in Mexico. Gomez et al. (1956) observed a marked difference in

mortality during first 48 hours between children with second degree malnutrition (6075% of median) and those with third degree malnutrition (< 60% of median). The Indian

Academy of Paediatrics (IAP) recommends the following classification : 80%, 70-80%,

60-70%, 50-60% and < 50% as normal, first, second, third and fourth grtde of mal

nutrition respectively (LAP, 1972). This classification is currently used by the Integrated

Child Development Scheme (ICDS) for selecting beneficiaries and growth monitoring

(Chart 1). As such, most of the classifications, based on weight for age use arbitrary cut

off points. Normal growth is considered to encompass values within two standard devia

tions of the mean. Since body weight does not follow Gaussian distribution, use of mean

and standard deviations for classifying children into differenet grades of nutritional

status may not be appropriate. To overcome these problems. Ramnath, et al. (1993),

recommend use of 5th percentile of reference values as the cut-off point to classify

children as normal and malnourished. They suggest that the weight below the 10th per

centile values of the community (ICMR data) may be considered as indicative of severe

degree of malnutrition. When these criteria were used, their analysis indicated that 80%

of NCHS median appeared appropriate to decide whether children were normal or mal

nourished. The current criterion of 60% of reference median for grading the children as

suffering from severe degree of malnutrition and 80% of reference median as cut-off be

tween 'normals' and malnourished, appears to be the most reasonable. A summary of

these classifications is given in Table-3.

GROWTH CHART - GIRLS

(IAP classification - NCHS standards)

SI.

No

Name of the

Village

1. Andhivadi

2. Kothakondapalli

I

3. Kothakondapalli

II

4. Bathalapalli

5. Bomandapalli

6. Belagondapalii

Number of

houses

Population

Male

Female

356

289

1551

1345

838

665

713

680

Male

134__

54

Female

86

70

167

640

312

328

52

56

108

370

182

433

1829

992

2132

937

514

1033

892

478

1099

110

44

103

115

40

89

225

84

192

0-5 population

Non SC

Total

220

124

Male

97

Female

63

Scheduled

Caste

Male Female

37

23______

Preliminary discussion on the finding of the nutritional assessment carried out in five

Miinties of the meeting

1. The following people from TVS company were present

2. Dr. Rajan Babu Chief Medical Officer

6. Mr. Ami tab . Community Development officer

llie following people from C11C were present

1.

Ms. Padmansim Asuri. Nutrition Consultant

2.

Mr. SJ.Chandcr, Field Training Coordinator

3.

Dr. Vinny. C?omrnunity Health Fellow

Before starling the presentation on the findings of the study. Ms. Padmasini clarified with the

TVS team to what extent, the concept of ICDS is being understood by the project staff of the

ICDS. The TVS team gave the feed back that it is not well understood by them. She said

ICDS is not merely a nursing teaching the number and rhymes to the children, it was started

to i’ldu in the over a.u development oi tnc child. it is not training centre out correctional

centre, helping addressing the child’s health and development needs. ICDS should focus on

personal hygiene, food hygiene and socialization. ICDS should take two years children too,

and asked if they take them; the answer was no.

Ms. Padmasini wanted to know if the ICDS project of the Krishnagiri district has a medical

officer to look into (he health needs of the children. She said if the government docs not have

one they should accept the role oi 1 VS medical officers.

Later she explained the standard used for assessing the nutritional status by the National

Centre for Health Statistics.. She explained what is percentile, particularly the 50th percentile

Later Mr.S J.Chander of CIIC made a presentation on ihe rinding of the study. The total

number of children covered by the study was 640 which include 313 girls and 327 boys

between 0-60 months of use.

■ Boys

. Girts

Total

i 7,7%

25,3%

___ ; 9.7%____ j 21.1%

■ 17.3%

i 46.4%

! 15.5%

:| 16.7%

! 32.2%

I 2.7%

; 1.4%

4.1%

|

j

i

It was noted that only 17% are normal and 78.6% were mild and moderate and 4.1 percent

were severe. Data on each village was also presented with comparison between boys and

girls. It was found that Bathala paili was the lowest and Andhiwadi was the highest. The TVS

team explained that residents of Andliiwadi are economically better off and the'residents of

Balhlapaiii arc poor. Il was observed that over all the girls seems io bee belter that the boys. Il

was observed that the malnutrition was present more in the 12-24 months age frequency. This

was explained as that this could uiie the increasing need of dietrary intake as the olav activity

of the child increase but the child may not be getting sufficient food. The TVS team

members asked why some cluldrcn cat mud. It was explained that the children that the

children could be suffering from calcium deficiency.

Ms. Padmasini said regarding the causes of mild malnutrition, it could he that the children are

not getting adequate food; as they children are growing the mother’s milk may not be

sufficient for the children and parents may not be aware of the required dietary intake for

children. Mother’s health status is important for delivering a normal child is important.

Children, who have experienced many episodes ot diarrhoea, should be ted double the

amount of food. It is important to know if the mothers know this and can they afford.

Education of diarrhoea and food hygiene is important in preventing. Worm infestation also

could be one of the causes A sick child my drop in growth but should regain in the next few

months. Others causes such as the economic status of the family particularly Hie-mother’s is

important for the nutritional status of a child.

Regarding the moderate state, it is likely to remain the same unless something drastic is done.

Regarding growth monitoring, she said it is not necessary that the children be weighed every'

month: it is OK if they' are weighed once in two or three months but weighing is important.

She said weighing is important; it is like the child’s horoscope.

Action plan

It was suggested that the mothers and community development staff of TVS should focus on

normal and mild children in preventing further mal nutrition. Moderately malnourished

cluldrcn should be attended by the anganwadi workers and the severely malnourished

children should be attended by a doctor. It was suggested to send a report with the findings of

the study io Tamil Nadu government. The meeting concluded with the decision that on 20"

TVS team with the anganwadi workers and CDPO’s will come to CHC for discussion and

drawing up a joint action plan.

By : S.J.Chandor

9*° June 2005

4

fxjvT- 1 3>»

Risks & Benefits

Justice

Informed consent

Public Health Research

Ethics in Nutrition Intervention Research

Common infections precipitate malnutrition, which in turn reduces resistance. This facilitates

further infections, which again lead to increased nutrition deficit. The 1960s was a period of

developing awareness of interactions between infections and malnutrition. Up to then the

research on and organisation of programmes for these two issues were separate enterprises.

So a national medical research institute, with multi-disciplinary participation of

scholars/researchers, decided to undertake a nutrition intervention study in a Primary Health

Centre area somewhere in North India with financial support from the International - UN and

state agencies and Indian government. The main objective/purpose of the study was to

determine if there was a synergism in. the programmes to control malnutrition and infections

similar to the known synergism between these problems. The child nutrition programmes at

that time (1960s) placed emphasis on nutritional rehabilitation, which treated children with

severe conditions like marasmus and kwashiorkor. This study was a step forward to

examining the synergism between malnutrition and infections to practical policy and

programmes.

The researchers felt that the only way that the synergy between malnutrition and infection in

the young infants and children could be examined was to find groups with high prevalence of

malnutrition and common infections and then study them to see what happens when efforts

were made to selectively reduce each type of condition. The nutrition project was conducted

in four clusters of 10 villages. Care was taken to ensure comparability between different

groups of villages and also sufficient separation in order to minimise communication among

villagers who received different service packages. To avoid random events particular to a

specific village from affecting the research process, at least two villages were selected from

each experimental or control group.

The total population covered in the two nutrition and population studies was 35,000 people in

26 villages distributed in clusters as experimental groups within 3 community development

blocks. On an average in the 10 nutrition study villages there were 1000 children below 3

years of age with each experimental group having an average of 200-300 children. In the

neighbourhood PHC, in 1955-60, the death rate for infants below age 1 was 156 per 1000 live

births. For the children 0-4 years of age, the mortality rate was 27 per 1000 population.

The researchers sought the cooperation of the villages and negotiated with them until the

combination of service interventions assigned to the village was accepted. There was no

compulsion for families to cooperate, but all village leaders agreed to help persuade all the

families to participate in the survey.

The following interventions were undertaken - the three nutrition villages received nutrition

care; the 2 health care villages received health care mainly for infection control and the third

received services for both. There were two control villages. The nutritional input consisted of

twice daily food supplements consisting o calorie fortified milk in the mid morning and

porridge made from crushed wheat, milk powder, raw sugar and oil in the mid after noon,

with a combined nutrient value of400 calories and 11 grams of protein.

Findings: The study found that nutrition care alone or in combination with health care

significantly improved both weight and height of study children beyond 17 months of age. At

36 months, children from the Nutrition intervention villages or the Nutrition and Health Care

intervention villages weighed on an average 560 gms. more and were 1.3 cm taller than those

in control villages. A male higher caste child from a nutritional input village or a nutrition

and health care input village averaged about 2 kilogrammes more in weight and 6 cm more in

height at 36 months than a female, lower caste child from the control village. Perinatal

mortality was significantly reduced in the nutrition and nutrition and health care input

villages compared with only health care villages (31 vs 45 perinatal deaths per 1000 live and

still births) and it was higher in the control villages ((57 per 1000 live and still births). This

was due to the supplementation of all mothers with iron and folic acid and additional feeding

for mothers at nutritional risk. Neonatal mortality and post-neonatal mortality significantly

reduced by one third to half in villages where health care or nutritional inputs were provided

vis-il-vis control villages.

Many years after the study was conducted, some Indian researchers expressed reservations

about the idea of undertaking a study in such settings and the ethical justification for

continuing to study a control group even though the implications of nutritional deprivation on

child survival were clearly established. The study researchers contended that even in control

villages, if the health workers found that a child was dying, going blind or suffering from

other illnesses that would leave permanent damages, the worker was instructed to call the

doctor to start intensive care. Others have justified the study saying that, (a) in the late 60s

and early 70s this was the understanding of scientific and ethical research. The scientists had

done their best to ensure scientific validity by conducting and documenting the study

carefully and drawing appropriate and cautious conclusions, (b) The study did not cause any

additional harm and all that researchers did was to make use of an existing

condition/situation.

Questions for discussion

1.

Who are the participants in this study and how would the researchers should-obtain their

informed consent for participation?

2.

What are the risks and benefits of participation in each arm of this study?

3.

What standard of care in each arm should be mandatory in order to conduct this study?

4.

Do the participants in each arm have a right to receive additional benefits after the

conclusion of the study, and if so, what and for how long?

5.

What kind of community engagement would be required for a study of this kind?

6.

In order to do this study, who all must consent? In order to obtain their consent, what

information each one needs to be provided? Would the researchers require different kinds of

consent for form for each?

(By Mala Ramanthan and Amar Jesani)

2

Risks and benefits - Informed consent -Methodology to study natural history of disease

An Indian study of the natural history of cervical cancer

Cancer of uterine cervix is the most frequent neoplasm among women in India. The epidemiological

evidence available in mid-1970s supported a spectrum of heterogeneous epithelial lesions antedating

invasive cervical cancer. The biological behaviour of these pre-cancerous lesions was not clearly

understood. It was felt that identification of relevant risk factors and the detection and management

of the pre-cancerous lesions were important in the prevention and control of invasive cancer of the

uterine cervix, more so in a resource poor setting of India. Such knowledge will help the health

services to selectively intervene early only in those women having high-risk cervical lesions. This

would enable the country to use its scarce health resources more efficiently.

Study design and methods: With such a goal, scientists.of a national institute in India designed amulti-disciplinary study. The study was carried out from 1976 to 1990. From 1976 to 1986, 120,471

women attending the gynaecologic outpatient departments of six major hospitals in a metropolitan

city were screened, and cervical smears of 117,411 collected along with clinical history and other

parameters. All women were called to the hospital clinics after 15 days to take reports of their

cervical smears. Of 117,411 cervical smears collected, 30,399 (25.9%) were negative, 84,889

(72.3%) showed inflammation, 1,910 (1.6%) had dysplastic lesions and 213 (0.2%) were malignant.

As women reported back to clinics of hospitals after 15 days to collect their reports, those women

who were having dysplasia were approached for recruitment in a study to observe or follow them up

for long time in order to understand the causative factors and biological behaviour of the dysplasia.

Some of those without any dysplasia and malignancy were recruited as matching control. On

recruitment the researchers collected detailed epidemiological information as well as biological

material for cytological (study of cells), histo-pathological (study of tissues to study manifestations

of disease), serological (study of body fluids) and immunological studies from all participants.