NUTRITION ASSESSMENT

Item

- Title

- NUTRITION ASSESSMENT

- extracted text

-

RF_NUT_7_SUDHA

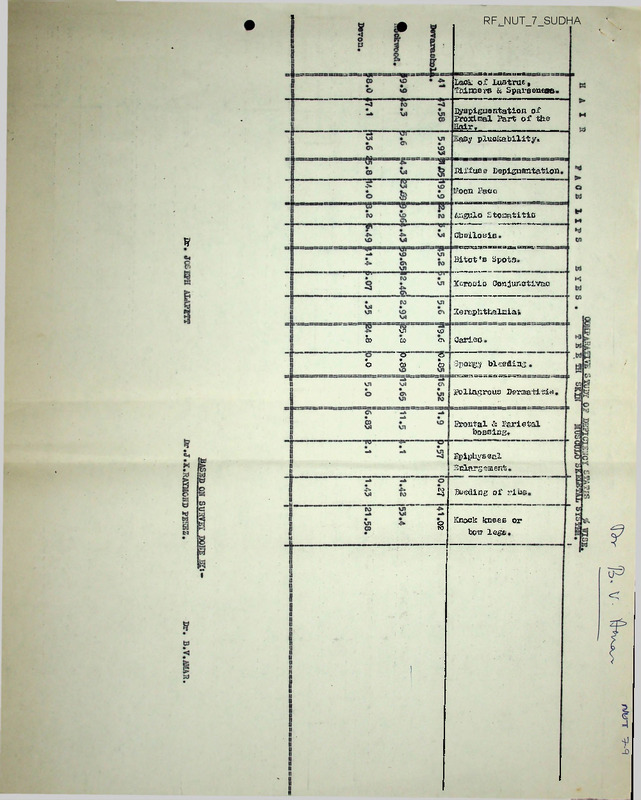

Lack of Lustrue,

Thinners & Sparseness.

Eyspigmentation of

Proximal Part of the

Hair.________

;«a£»y pluckability.

Diffuse Depignantation

Koon 1’aoo

Angulo stomatitis

ChciloBis

%

Bitot’s Spots.

Xerosis Conjunctivae

Xerophthalmia.

'Ll

to

b

00

<n

Sarles

b

*~5T

b

o

b

Spongy bleeding

Pellagrous Penaatitie

Frontal & Parietal

bossing.

Epiphyseal

Enlargement

3

Beetling of ribs.

8

Knock knees or

bon lege

clinical assessment survey- 197fr»79

(Devarashola, Rockwood,

Doveon and All-Indla).

—

H A I Hl

Jr- li Xeare»8

Deverashola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Kean for the group.

• All-India.

FA C E

_

Total Ko. of-Lack of lustre Thinners

Children, and Sparseness

Easy Pluckability

Diffuse

Depigacntation.

Ho. of Sign

of Children.

No. of

Percen

sign of

tage.

Children.

Ko. of

Sign of

Children,

Per

cen

tage.

53

46

27

126

ityspigmontation of

X’roxiraal part of hair.

Percentage Mo. of sign percen

tage.

of Children.

Mota Face,

No. of sign Per

of Children cen

tage.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

21

14

U

49

39.6

30.4

51.9

38.9

6.3

27

9

15

51

3.9

19.6

55.6

40.5

5.8

2

2

4

8

3.8

4.3

14.8

6.3

3

11

10

3

34

-

20.8

21.7

11.1

19

*

8.

8.

6

22

-

15.1

17.4

22.2

17.5

1.4

20

17

8

55-6

42.5

50

2

2

1

5.6

5

6.3

11

14

4

30.6

35

25

9

6

5

25

15

31.3

45

48.9

7

5

5.4

2.9

29

*

31.5

•*

20

—

21.7

2.4

4

6

16.2k

16

9.3

12.2

16.2

12.4

13

21

16

50

30.2

42.9

43.2

38.8

13

12

8

33

30.2

24.5

21,6

15.6

1.6

-

*■

-

3.4

5.3

2.3

12.5

5.2

1.2

11

12

4

27

*

28.9

27.9

25

27.8

-

6

11

3

20

—

15.8

25.6

18.8

20.6

4.9

——

Deverashola.

Rookwood.

Devon.

16

40

16

18

17

5 '

50.00

Mean for the group.

All India-

92

40

43.5

4.4

42.5

31.5

------- -

——

------ ------ -

2 - 2-?? Years*Tteverashola.

w Rockwood.

Devon.

Moan for the group.

All-India.

2j.. xlJ&gFLte

Devarashola.

Rookwood.

Devon.

Mean for the group.

All-India.

43

49

37.

129

26

20

1?

63

60.5

40.8

45.9

48.8

—

—

3.6

38

43

16

97

•»

13

19

5

37

*■

34.2

44.2

33.3

38.1

6.1

24

26

♦5.1

66

55.8

53 .1

45.2

51.2

6.6

14

15

4

33

-

36.8

34.9

25

34

6.6

2

1

2

5

•»

CKINICAB ASSESSHTMT SURVEY-. 1978"I5x

(Deverashola, Hockwood, Devon and All~In<Jia»)

____________________________________

H A I

R

Total Ho. of lack of lustre, thinness and Sparseness.

Children,

Percentage.

Signs of

Children.

2

1

*

______________

Dyspignention of proximal pari of hair

Signs of

Children.

3

Percentage.

4

Easy pluckability.

Signs of

Children.

5

Percentage

6

ZLsJLXearPir

Deveraohola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Mean fbr the Croup.

All-India:

96

106

80

282

-

42

39

29

110

-

43.75

36.79

36.25

39.00

2.9

44

47

41

132

-

45.83

44.33

51.25

46.80

3.8

7

4

9

20

4

7.29

3.77

11.25

7.09

1.00

Deverashola.

Rookwood.

Devon.

Mean for the Group.

All-Indiaj

85

102

53

240

-

27

36

25

88

-

31.76

35.29

47.16

36.66

1.5

38

47

22

107

-

44.70

46.07

41.50

44.58

1.6

4

f

5

14

-

4.70

4.90

9.43

5.83

0.5

•

ck

ai

s

ss ss

cssESssrsssssacsss » s ssjssa«»»53s= XSSlSSjxttUSSES essscssssswais! aa ss

Total No.

of Children,

•

3r4X.efi.rsL*

Deverashola

Rookwood.

Davon.

Mean for the Group.

All-India.

1jxxxuso Bopif^mentation

Sign of

Percen

Children.

tage.

96

106

80

282

85

002

53

240

w

Moon Pace ______ Xerosis

Percen

Sign of

Sign of

Children

tage,

Children

' 1 "........

2

3

4

31

42

27

100

32.29

39.62

33.75

35.46

23

27

9

59

•

23.95

25.47

11.25

20.92

3.5-

—

4 r. j..Xc££S?.=

Devarashola.

Rookwood.

Devon.

Mean for the Group.

All-lndla.

ss «s 33SS3Ssa»»SSS3 -nsaonssasisa sssssxssssassx

“~5

9

14

5

28

*>

Percen

tage.

g—~

9.37

13.20

6.25

9.92

5.5

Xeropthalmia

Sign of

percen

Children. tage.

37.64

45.09

32.07

39.58

•

a X s c:

Bitot's spot.

Sign of

Children Percen

tage.

7.....

I8

!5

10

7

«

*

11

7.29

3.77

3.90

51

61

37

149

53.12

57.54

46.25

52.83

3.3

42

74

25

141

-

49.41

72.54

47.16

58.75

4.8

—

<—

32

46

17

95

•

» -x s x

11

16

8

35

•

13.41

16.68

15.09

12,41

1.8

5

15

1

19

3.52

14.70

1.88

7.91

5.8

7

2

*

9

—

8.23

1.96

—

3.75

•

CLINICAL ASSESSHEHT

(Devaraehola, Rockwood, Devon anfl All-India.)

T E B TE

Total No. Carle s

of Chil

dren.

sign of percen

Children tage...

1

2

6666

1 - 1j Years;Dovara choir.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Lloan for the group.

All-India.

3.8

2.2

—

2.4

-

GUMS

Spongy bleeding gune

_____ SKI. H

pelKgrous-dermtoala

B O HE.

Frontal and Parietal

BoBeing.

Sign of

Children.

3

Sign of

Children.

5

Sign of

Children.

7

Percen

tage.

8

—

—

-

Percen

tage.

4

53

46

27

126

•

2

1

3

-

Devaraehola.

Rockwood

Devon.

Keen for tie group.

All-India.

36

40

16

92

-

4

4

8

-

10

25

8.7

0.4

2 - aiTeargtItevaran tola.

Dockwood.

Devon.

Mean for the Group.

AAll-India.

43

49

37

129

-

5

9

8

22

-

11.6

13.4

21.6

17.6

2.0

1

1

-

—

23.7

9.3

25.0

17.5

4.1

1

2.6

flfl*

—

—

—

-

1’ercen. tage.

6

Dpiphysaal enlaro»-nwnt.

Sign of

Ghildr»n.

9

Peroei>

10

8

6

2

16

—

15.1

13.00

7.14

12.7

0.2

2

5

3

10

-

3.8

10.09

11.1

7.9

2.23

*

5

2

4

11

-

13.9

5

25.0

12

0.4

1

2

4

7

-

2.8

5

25.0

7.6

2.23

*

2

2

-

*

5,0

—

2.2

6

5

1

13

*

14

12.2

2.7

10.1

0.4

2

6

2

10

•

4.7

12.2

5.4

7.8

2.25

1

1

5

-

2.3

2.0

8.1

3.9

1.3

3

3

*

6

—

7.9

7.0

—

6.2

0.4

«

7

1

8

-

16.3

6.25

8.2

2.23

1

3

—

4

-

2.6

7.0

—

4.1

1.3

»

2

-

*

4.3

*

1.6

1.3

i

2i - 3 YOfigB t DevaraBhola.

Rockwood

Devon.

Mean for -the group.

AlL-lndi.ru

39

43

16

97

—

9

4

4

17

-

—

*

—

W

-

-*

fl*0.1

•

—

-

1

-

-

2

0.8

0.8

—

—

1.0

1.2

w

>

1.31

SURVEY- 1978-7&

CLU1ZCAL

(Dcveraehola, Roaisrood, Devon & Ali-india).

lips.

eyes

total So. of XeroBiB Conjunctivae. Xsr cphttialaid'(Inola*”"

Children.ding Keratomalacia)»

Sign of

Percentage

Sign of

PcroenChildren

Children

tags.

1

V ~ H fraraiD veraohola

5

_

tpot

Sign of

Children

Percentag©.

. 4

___ 5______

6

___ 7____ 8

Sign Of

Children

____ 9___10___

53

5

5.7

1

30.19

2

3.8

2

3

-

4.5

11.1

1.5

1

•

1.9

2.2

0.1

16

46

27

23DEWhEXX±Mx&ESE?3 All-InfliasJtfcg

14

2

*

30.4

7.4

6

1

-

3.7

1.6

1

1

-

2.2

3.7

.4

Mean for tho Group.

126

8,

6.5

2

1.6

52

25.4

>

2.4

2

1.6

Deveraahola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

56

40

16

1

2

2

2.8

5.00

12.5

1

-

2

-

16

22

4

44.4

55.00

28.00

3

-

8.3

7.5

-

1

2

-

2.8

5.00

-

Mean for tho group.

All-Indin:

92

-

5

-

5.4

2.2

1

-

1.1

-

42

-

45.7

1.5

6

-

6.5

3.8

3

-

3.3

0.6

2=2^YearEl~

Dcveraehola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Mean for the group.

All-Indiat

45

49

57

129

*

3

6

5

12

7

12.2

8.1

9.5

5.5

2

1

4

*

4.7

4.1

19

57

7

63

-

44.2

75.5

18.9

48.8

1.9

2

3

6

11

*

4.7

6.1

16.2

8.5

3.4

4

3.

-

9.4

6.1

58

45

4

6

•

10

10.5

15.00

—

10.5

4.2

3

2

5

7.9

4.7

5.2

15

21

10

46

«■»

39,5

48.8

62 .5

47.4

3.1

8

4

12

21.1

9.3

12.4

6.1

1

2

3

Rockwood.

Devon.

I

2

Cheilitaia.

_

Percen- Sign of Peroen

tage.

Children tags.

Angular Stomatltio

lOotT's

-

-

Ikr. 2..Xems.r...

2j- 5

YearsiDeverashola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Mean for the Group.

All-India.

«e

m

-

ssiBn».Tr-.T ssts sskk:=»3S^===:sts, sssssasase: =s

«twswMBtsffiUMtBsxcMSiann sxsxsxascsxs^cxsssCTMnBTgaso

3.1

-

jsoaassca- HXSiS3S3 £2fT? S3-C3C5® 2222®~~SSIa sssa S3 XS SSSJwWSSS XUSxx

-

»»s:=s3S3sx=aecU3SSSSSES3SSSS3

—

5.4

1.2

2.6

12.5

3.1

1.5

asasssa

CLINICAL ASSESSm^T SURVEY- 1918-79

(Severashola, Rockwood,

Devon and All-India.)

IfflSOULAR

Total No. of

Children.

SKELETAL

AND

Bleading of Ribs.

SYS TEE.

Knock-knee© or Dow lege.

Sign of Children

Percentage.

>—

*

—

0.4

13

11

1

25

*

24.5

23.9

3.7

19.8

9*07

•w

5

*

2.2

0.4

9

16

7

32

-

25.00

40.00

43.8

34.8

0.07

«w

*

0.4

14

28

8

50

-

32.6

57.1

21.6

38.8

0.07

—

17

14

7

38

-

44.7

32.6

43.8

39.2

0.07

Sign of Children Percentage

1- HYears:Iteveraeiiola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Mean for the group.

All-India:

53

46

27

126

-

H -2 Years:Deveranhola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

llean for the group.

All-India:

—

■»

2

36

40

16

92

—

2

-

—

- rTu i

2 - 2{:- Years:Devorashola.

Rockwood.

Devon.

Mean for the group.

All-India:

43

49

37

129

-

2?> - 3 Tears:Devcrashoiu

Rockwood.

Devon.

Llean for tho group.

All-India.

36

43

16

97

•

S

53 S3 S3 S3 £5 SX

-

—

—

—

'f

—

—

-

*

*

0.4

= a = =saeaaaa = — as

as

ss as

nzcasEfias -

s» ss a o c s »

ss ss ss

ASSESSMENTS 19lg~Z2i.

(Devarashola Group of Estates.).

_________ ____ _______________ MtAQAJW„ age m,

_________ _____ ______________________________________________

0-3

3-6

6-9

9/12-1

li^xJJS^- 2-2* Yrs. 2^.-3 Yrs . 3 - 4

4 - . yrs. ._

Months. Months. Koniho.

Year.

mle Pejaale Lislepeaalo aale 3‘emale Male Eemale HaleItenale

mla /©male.

Devcsnehola.

2.5

5.9

$.6

7

7.7

7.4

8.3

8.4

9.8

9.1

10.9

10.7

11.5

10.8

13.1

12.6

W6ckwood.

3.1

9.3

6.5

6.9

8.3

7.4

9.0

8.4

9.8

8.8

11.3

9.9

12.1

11.4

12.9

12.6

Devon.

4.0

8t6

9.3

9.3

7.6

7.3

5.1

7.7

5.1

9j>

10 5

10.2

11.2

11.£

13.2

13.4

AU-India.

-

-

-

-

7.8

7.3

8.5

8.0

9.4

9.0

9.8

9.7

11.1

10.7

13.2

12.6

Doveraehola.

51.0

60.9

63.5

66.7

70.8

70.3

74.0

75.0

79.3

79.2

86.0

82.8 89.0

86.7

95.2

92.3

Booktood.

51.5

55.7

63.7

63.9

98.6

66.6

72.9

72.3

78.2

76.9

83.6

81.3 84.3

85.6

92.1

91.9

Devon.

57.0

57.2

64.5

68.3

73.7

71.8

78.0

77.2

75.4

78.0

85.5

85.1

87.4

87.3

93.2

95.1

',11-India.

—

—

-

—

70.8

69.3

74.2

73.3

78.2

77.1

81.3

85.8

86.2

84.9

93.9

92.6

Doveraslwla,

37.1

41.2

42.5

43.2

45.6

43.8

45.9

^j.O

46.5

46.3

48.0

47.2 47.9

47.3

48.9

48.3

Bockwood.

35.5

39.6

41.8

43.1 ■

44.4

41.6

44.4

|44.2

46.4

45.8

46.6

45.7

47.1

46.4

47.5

47.4

47.1

1-4.3

46.6

45.8

47.0

46.3

48.4

47.0

48.9

47.4

45.1

I4.O

45.5

44.6

46.3

45.4 47 .a

46.1

47.9

47.1.

Ci'S1OOggEXESl I

5Y UI j>

13.2

12.6 Ji2*7

12.7

14,1

14.3

WEIGHT AGAINST AGE G-HOU?;

AGE BZ HEAD CIWCWIJWiCE

41.0

Devon.

All India.

-

IWeraahola.

39.7

-

42.8

-

43.8

-

45.2

43.9

43.8

43.0

13.1

13.0

15.6

13.5

13.8

13.5

13*5

13.4

14.1

13.4

14.0

14.5

14.3

14.2

12,6

12.5

13.0

12.3

12.8

12.9

13.1

13.5

12.7 K5- 15.0

AGE BY CHEST aihWMFERENcji/ “ “ •

45.0 J'43.7

44.6

44,0

47.8

12.8

13.0

13.0

13.4

13.4

14.0

13.9

45.9

4818

47.9 49.6

49.1

51.0

50.7

Bo ck wood.

13.5

13.1

13.6 Jp3.3

Devon.

12.9

11.2

11.4 hl.6

All-Indla

1*. «» «RT

•pevareehola.

Bookwocd.

mb

■»*

m*

w

12.5

12.1

44.6

42.4

45.9 ,W 45.9

48.0

46.4

48.5

48.0 49.5

48.5

49.7

49.4

Devon.

44.9

44.1

47.3 /■ 43.6

47.4

46.4

48.5

47.4

50.0

48,3

49.9

49.4

All India.

43.1

42.1

45.5

48,1

46.9

49.6

48.6

44.5 ‘4M

45.4

44.4

46.6

Nutritional assessment of under fives belonging to three estates

* in Gudulur Taluk.

-z-z. zZ--3-3,

Survey done by: Dr. Joseph Alapatt.

Dr. B.v.Amar.

Dr. Raymond X. Perez.

SUMMARY: Large majority of children are suffering from malnutrition

Anthropometrical measurement shows close parallel to the all India

mean and falls ^elow the normal growth curves. Clinical assessment

supports these ^sctsjT’most of those, examined showed deficiency

signs. Practice of bad food habits and unhealthy housing and

sanitation has contributed to the high degree of malnutrition

among the under Fives. Ill^tracy also plays an important role.

INTRODUCTION: Good nutrition is of prime importance in attaining

normal growth and development and maintenance of health throughout

life. During our stay in the estates we noticed that most of the

mothers go for work leaving behind their children in the Creeches

I and paying little attention to their diet. 1979 being the Inter

national Year of the Child we decided to look into the nutritional

status of these children*Ue participated in similar surveys during

our "Social Paediatrics" posting which gave us the impetus to attempt

this survey.

OBJECTIVES: Objectives are as follows:1)

Anthropometrical and Clinical Assessment of

nutricional status.

2)

having found the deficiency/malnutrition; to

assess the impact of existing, curative and

educational /standards of the health care in the

estates.

wW ?

MATERIALS AND METHODS 8

PERSONNEL:!) Medical adviser ( CLWS, UPASI)

~

)■

2) One health worker ( —" —•)

3)

Balasevikas and the compounder of the respective

estates.

A proforma containing anthropometrical measurements and various

signs of nutritional deficiency states was prepared for each child.

We instructed ^supervised the balasevikas, health worker, and

the compounder in the use of measuring tape, weight, balance and height

scale in taking anthropometrical measurements while we carried out

the clinical assessment of children.

Advance notice was given to all the workers to bring their

children to tTie resPsctive creeches/schools for assessment. Defaulters

were covered by line to line approach, The hospital in-patients were

also examined thereby obtaining 100% coverage

the children in

these estates.

- 2 -

ANALYSIS!

Key to the Graphs

: ANTIffidPOMiiTTICAL MEASUREMENTS!

1.

2.

Weigh t/age study in male.

Weight/age study in female.

3.

Ht/age study mules.

4.

5.

Ht/age study feraalf1".

Chest oircumference/age male.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Chest circumferenee/age female,

Head cLrcoEiference male.

Head circumference female*

Midarm clrctaiferenoe male.

10.

Midarm circumference female.

Graph 1 A 2;-

All the three estates and the Indian mean appear to be much

below the norftal co ad to health standards.

'

2 - 2J- year aga group, both boys and girls have not registered

any weight gains all of growth curve also occurs iu Rockwood estate

at 4th yeai'.

In Devarahola 3 years 4ysurs age group show only bare,

minimal weight gain.

Graph 3 & 4?.~

Growth curves of all 3 estates drop at the age of 4 years

Growth curve which sre wall below ths standards begin to full-

one thinks it is time to worry.

1£ “

years ag-' group i" Devon (both b&ya and girls) show

a stepp fall in the growth curve, thereby suggesting that weaning

period and their customs contribute to a great many

of PCM in

this estate.

The vegetarian food habits of this community also

contributes.

Graphs 5,6t7,8 & 11,

At birth, the head oiroumfex'enoe is much greater than the

chest circuEifex'snce but depending upon the mental gxowth, the two

curves meet aadh other sooner or later and the Chest circumference

overtakes the Iwsi circumference at the age of 2 years in Indian

children and 9 month or so among American children, Thia hae been

linked up with malnutrition prevailing in our country. Among the

estates, in hevsrshole, the crossing takes plf.ce at the age of

2| years.

In Rockwood, the head circumference always remains

lowers in Devon, they cross at 1 year.

- 3 -

’

Based upon this we find that in Rockwood, - from "birth, the

child is at a dieadvantage(therefore interbreeding among the Maplhas

is very common and polygamy is the rule) and continues to be deprive

them from growing up normal citizens of India.

DEVARSHOLA:

Ac for as the data collected, thid is perhaps the only

estate amongst these three estates which shows signs of promise and

this is due to

(1) The group Manager is incharge of this estate.

(ii) The group medical officer (CM3) and his AMO are residing

there, having a group hospital with OT facilities.

Head and chest circumference cross each other at a later age

than the mean, Indian child does (2 years), as this is an indication

of the prevailing nutrititional status of children, this goes to

show the situation st Devarshola estate.

A

Graphs 9 & 10:

Midarm circumference in devon is well below that of All India

mean, whereas Rockwood and Devarshola are above it.

boys in Bevan, there is fall in circumference.

years

DISCUSSION

BAR DIAGRAM:

% of diflciency status in each estate.

On observing the tables the bar diagram, protien calorie deficiency

(

is prevalent in ail 5 estates, Rockwood and Devarshola have high

incidences (47.50$ ami 42.5$ resp) of protine dificieney as compared

to Devon where protin calorie deficiency is more, explaining the

fact that there are more vegetarians in Devon estate.

£

Vit * A* : dificieney is prevalent in all, amounting to more than 40$.

But in Rockwood, it is nearly 60$, This high incidence of Vit ‘A*

dificieney may be explained due to their cooking habits (Prolonged ----- 7

boiling of vegltables).

The car&dane intak of Devon appears to be

much more than the other tow estates - may be due to their food habits

(vegetarians).— ?

Vit *B* ;

deficiency appear to be more in Devarshola.

Vit * C* ; deficiency does not seen to exist as citrus fruits are

*7

easily available amidst the hills.

(------------------------------------------------------------As far as Vit *D*;

deficiency is concerned it is double that of

Devon in Rockwood, and Devershola estates. The $ of attendance in

creches and schools in Devon estate is comparitivety low and the

child is carried on the back of the mother explaining the following.

PCM because they do not get enou^i supplement from creche or

scnoola.

Vit "D’ deficiency is less than elsewhere ie.t u v light

exposure is more than the other tw0 estates reflecting the low

attendance in school and creches in Devon estate, where they are

given Mid Day Meal which for some form they only Balance diet.

- 4 The elirnnte and the natural

up io not allow enough euilight

resulting in the deficiency of Vit ’D' in all three estates.

BEOOMMBNDATIONS?

1.

Education is a in tint People there lack literacy.

be able to read, write, and understand.

the health education will be abortive.

2.

They should

Unless there la basic education

Family Planning shouldbe introduced and encouraged there.

For a few, it is against their religions customs,

The cause of

this failure can also be explained by the fact that after the age

of 10, he/she in the family becomes one of the earning members in

the house. Naturally, an earning member is as asset to the family

and they would like to have as many as possible. (They should be

encouraged to have less but healthier and better educated children

there by, increasing eai'ning capacity.)

h

3. Early marriage should be discouraged.

4. biiring our line to line visit we observed that, the lines

7

are crowded and the houses are not adequate enough to accomodate

the Icing slaefamilies. Sanitation is very poor and the surrounding

are not kept clean.

The house lack adequate ventilation.

Health education should Ls baaed ou the followings-,

1.

3.

Family Planning.

Food habits.

2. Sanitation.

4. Chnsanguityr— >

/

/

During our assessment we cane across, few cases of gross mental

retardation congenital heart diseases, CDS, and TEV - may be due to

coneanguity,

)

5. Rockwood needs a full time MO as it is far from the group

hospital and the Medical Officers arc not staying in an approachable

distance.

An annual objective review by the Medical Officers to assess the

response to the health education should be carried out.

A closer participation of the estate beaurocracy is indicated.

AOiOiOWLaD GEMi& To?

We thank first and foremost, our Community Medicine Department

for having given us this exeellant opportunity of studying the

workings of the Tea estates and its workers.

We thank them also for

their guidance and full Co-operation in having made the project a

success.

We thank Dr. M&4. Rahamaihullah,

Dr. S. Pothl and the CLWS

workers, for their guidance and organisation.

□or heartful thanks to ths froup Medical Officer, and the

Medical Officer for their help, encouragement and guidance.

- 5 -

We are feaiful to the Manager, Balasevikas, and Compounders

of the respective estates, for helping us to obtain insight into

the problem.

BIOLOGRAPHY

Text Bosk of preventive and social medicine - Part.

National Pls n of action for international year of the child 1979.

Text Bosk of Paediatsiss- nelson,

Text Book of Pediatries - Aohar.

Outline of Paediatrics

- Slobody.

PKuGRAl! COMPONENT

I'ight st the outset of our interchip, we wore informed about

the need of bias io health doctors' appreciation and involvement in

the following,

1. Prevecitics:

1

a) Eviornmental sanitation.

b) Im'scnleation of under 5s.

2.

Ke al th education of the masses.

3.

4.

Family Planning.

Curtice work.

EHPIK.13:;S?'TA]j 3’ITATIJKs-

Xa th-: estates of Xtlgiris, we noticed

poor housing, inadequate ventilation and lighting, improper disposal

of waste and axercto.

tTs p:>^*nhle wr;*:r lo *.Inible f$r the c&aenmptioh of the workers

We udrisnd the *r;tnte M.-marrsr and lick workers, how to circumvent

the vace,

IMHdSIuATIOih I haring cur social paedlatoro posting, before, we

embarked to the estates, we inntoiaed 1058 children belonging to

our neighbouring villages, <3uddag?Jhte- paiyg, Gurapu pslya and

providence school) with Df'T & JPV,

We did a study of the innufflerisatioa coverage among the CIWS

estates, with hr. dahaiathullab, the figoraa of which, she presented

during th® child haslth conference, at Ccocoor,

HEALTH EDUCATIVE s- During our Bocxal peadlatx’ics posting, we educated

the pax'euts of the aei^jbouring villages with the help ;f charts,

the need for

i) proper disposal of waste and excreta.

ii) the need for IraaunismtioB

ill) Balanced diet.

iv) anti helminthtio precautions.

v) Portable water.

It: the estate,s we educated, the link workers by giving them

simpxe data about nutrition, sanitation, Inuuunisatiu and common

diseases, who intern are sappased to educate the workers.

Suring our clinical asscuement of children, ’.-re inforised th®

parents, of the sailuxwa*3 inadequacies, their eauste and co ruction,

FAMILY PWKINGj-

Chrativa work:-

be handled the out patient clinic

in Goonoci-, dozing the moming hours.

Boring the IfFMI week, w© were the medical officcra who were

posted at different sport venues.

The congenital heart disease, TEV, Qi>H, these cases we reffered

tn the Coimbatore District Hospital for the necessary treatment.

We brought to the notice of th® Medical Officer, oases which needed

treatment in the estates.

- 2 Oar interest in social paediatries was eahaaced daring SJMC

Hospital posting where— we have already mentioned, we assessed

nutritional status of children among the neighbauring villages,

we were askecTta da a study an the foilawing amongst the estate

warkers.

1. Bauble checking the ICMR pilat project.

2, Respiratory disorders amongst the insecticide sprayers.

J. Link warkers scheme.

We finished the double checking af the ICMR pilot project.

We could not carry aut a study an the inseeticide, sprayers

as all the male Workers are employed in apreying as a part af the

task work. We attended the link voters meeting at different

estates and educated them.

We prepared the falders and its contents for the 'Child Health

Conference’ which was held at UP AS I @n September 2, 1979.

As instructed and guided by Dr, Dara,

S.?Amar, w started

examining children f®r the incidence af aieabrics and pedioulasn

in Glendall estate. But, befare we could camplete the survey we

were requested by Dr. Mrs. Rahamathullah, to assess the Nutritional

status of children belonging to the Devarshola group of estates.

We assessed all the children (100$)

FaAjLY PLANNING*- During sy Family Planning postings, I did 4

tubtfetomies. £k I did not get an opportunity for vasectomy.

Durink my da a no or postings, I did 7 Tub^atomies making it a

total ©f 11 Tubeetomies.

UM

2^

■ J

tew

gSSgS

nnn

pill

ns

iios

I • OS'f)

llllilibSSliiBli

/ A e V M P C -fi(r tv (l

■

1101

- Qihj

1111*

fi'illl

■

(7 ^

!

Mid- mn

ciRccMPe/e^Aj c&

£1

>

IZn>v

siifflBSil

NUTHTTIONAl assessment.

Clinical Analysis of Highwayye—Group, Pff-j-atates*

Name of the estateB,

; Age group.

0-J months*

j

Cloudland.

i

Highwavye.

Upper Maneleer*

Manalaar.

Venniar I.

Venniar II,

Venniar III.

8

8

1

7

]

j

j

Total number

i of children.

4

5

1 a

1 b

1 o

1 d

1

1

..

1

..

..

2 a

2 b

••

••

3 a

3 d

••

3

Hair.

I

Face.

’

i

'

Eyes.

lips.

I

4 a

4 b

I

Teeth.

i

Bin.

I

..

6 a

6 b

8 a

8 b

••

••

9 a

• •

..

I

Najl.

A A

A ‘ti

AA

Mugcular_&

skeletal

gystems.

' 1

••

■•

A*

••

••

A A

AA

••

A*

• A

*A

A A

..

••

••

••

0

;

I

AA

a a

••

••

••

- a

*A

••

1

I

Pyoderma *

P

I

•' «

I

Otitjp.

i

|

..

11 a

11 d

11 8

11 h

11 f

L

.a

••

Pb

••

!

Mo

•*

Soabieo*

..

A* A

i

I

I

••

_k¥TJ.

••

••

••

I

I ••

••

••

••

••

• •

••

••

••

1

••

I

••

••

••

••

i

I

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT.

Clinical Analysis of Highwavys Group__of Elates

I

Name of the estates.

Age group.

Cloudland•

Highwavys•

Manalaar.

Upper Manalaar.

Venniar I.

Venniar II,

Venniarlll

4

5

. . .

Total number

of children.

9

9

9

14

7

1

1

1

1

F

[

I

Hair.

a

b

c

d

3

• •

..

4

2

6

2

ii

Face.

2

••

..

••

• •

I

1

| ■

2 a

2 b

..

• •

Eyes.

..

3 a

3 d

I

Lips.

• •

I

4 a

4 b

••

..

••

Teeth.

B

6 a

6 b

••

..

8 a

8 b

• •

Skin.

■

••

■

''

I

• •

I

Nail.

9 a

..

..

a

d

g

h

f

••

A.

• •

• •

••

• •

0

• >

I

..

••

••

a.

a •

•«

-.

• •

• a

• •

• •

• •

••

••

• •

••

• •

• •

••

••

••

• •

••

••

**

••

Muscular &

skeletal

systems.

11

11

11

11

11

--

1

-.

...

Otitis.

••

••

Pyoderma.

P

LRTI

••

••

1

••

••

• •

••

Scabies.

S

• •

••

Pb

••

••

Me

••

•*

.•

• •

••

I

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSI-IEN.

Clinical Analysis of_Kighwa^s.. Grpup_<^.^o.tes .

Name of the estates.

6-9 months.

Highwavys.

Cloudland.

Manalaar.

Upper Manalaar.

Venniar I.

Venniar II.

Venniar III

i

i

i

Total number

of children.

5

12

7

12

3

7

10

3

6

1

8

1

2

3

4

**

*i

Hair.

1 a

1 b

m

r

~

1

c

d

::

I

i

Pace .

2 a

2 b

i

••

••

Eyes .

..

3 a

3 d

Lips.

4 a

4 b

Teeth.

6 a

6 b

A

••

..

Skin.

8 a

8 b

1

Nail.

9 a

Muscular &

skeletal

figstarns.

i

11 a

11 d

11 ff

11 h

11 f

*i

z

I

Otitis.

0

-

1

Pyoderma..

P

i

••

1

"

LRTI.

1

1

Scabies.

S

Ph

__

I

!

J

i

-----------------------

I

::

...

••

i

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT,

Clinical Analysis of Highws.V£P—P?QUP—PJ ^BtateR.

Name of the estates

Age group

9-12 months.

Upper Manalaar.

Highwavys.

Cloudland.

Manalaar.

j

Venniar I.

Venniar .11 .

Venniar III.

I

1

Total number

of children.

5

13

6

6

3

11 dc

3

.a

••

• •

o a

••

2 a

2 b

• •

-•

3 a

3 d

..

• • •

4 a

4 b

••

24

3

5

1 a

1 b

ml

F

r

8

1

He. ir .

15

3

2

••

6

1

••

• •

Face .

..

••

••

!

..

Eyes .

••

Lips .

• •

••

••

• •*

6 a

6 b

B

a•

• •

!

8 a

8 b

••

9 a

••

••

..

• •

••

..

• •

Skin.

'

I

1

Teeth.

1

..

...

i

• • •

|

Neil.

• •

•.

••

Muscular &

skeletal

systems.

11

11

11

11

11

a

d

g

h

f

|

••

••

•’

1

1

m *

•.

a •

••

Otitis.

Ii

I

i

••

1

1

•a .

*•

••

.*

• a

**

• •

• .

. •

••

•.

••

••

••

••

I

••

..

2

• •

••

••

••

• •

1

. .

• •

••

1

••

••

..

..

••

• •

1

••

S

••

..

..

••

• •

..

Pb

1

..

••

• •

..

Me

1

••

**

••

0

j

Pyoderma.

P

LREI.

I

j

I

Scabies.

i

I

i

I

••

••

I

i

;

>

!

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT.

Clinical Analysis of Highwayye Orgur O.£_gptates.

1

Name of the estates,

Age group.

1-1/2 years.

____ ______ ._______________________________________ ______________ ___ .______

Cloudland.

I

Highwayye.

F

M

F

9

12

17

2

«=>

7

M

F

M

F

M

7

9

9

13

13

4

8

1

6

5

9

6

SB

am

so

'SB

—

ca

Venniar I.

Manalaar.

Upper Manalaar.

M

Venniar II.

M

F

M

F

7

13

6

10

6

6

•

SB

i

Total number

of children.

Venniar III.

F

Hajr.

1 a

1 b

I ■

—

-

1

-

2 a

2 b

—

•

Sb

*

-

I

1

-

3

<a»

<->

*

6

■■

n

8

sb

■B

«•

«=»

■

*

-

1

-

-

1

mm

—

•

*

•

•

•

2

Face.

I

—

—

—

-

-

W

a.

—

I -

6

*

Eyep.

3 a

3 d

-

—

m

—

am

—

—

*

-

■B

-

■B

-

-

•

—

«•

'-a

•

__

—

—

—

—

—

•

•

-

-

-

•

«»

•

so

-

am

SB

—

i

iiR£.

*

•»

—

-»

—

—

—

-

-

-

-

8 b

SB

•

*

—

—

1

1

—

—

•B

9 a

—

mb

—

•

*

•

—

-

-

-

—

*

—

*

•»

*

—

—

*

1

*

1

*

SB

Sb

*

SB

SB

«•

*1

■»

SB

es

«m

-

SB

SB

a*

«»

—

—

—

am

•

M*

•

•»

*»

—

m.

1

1

4 &

4 b

Teeth.

6 a

6 b

I

I

Skin.

—

—

SB

•

—

—

-

M4

ern

—

•

•

SB

•

•

SB

•

MB

MS

*

SB

-

•

1

1

•

Najl.

Muscular A

skeletal

systems.

11

11

11

11

11

a

d

e

h

f

MB

,MB

—

—

I

i

I

1

ate

am

-

sb

MS

•

<a*

OB

otitis.

0

*

■fycdermy..

F

1

•

-

LET I.

i

1

1

-

—

•

1

1

-

-

—

•

-

*

—

•

«»

me

—

*

Scabies,

S

Eb

Me

•

1

-

-

-

—

•

«•

-

—

j

-

|

**

-

I

-

i

i

SB

-

«•

—

—

i

i

Sb

NUTRIIIONAI. ASSESSMENT.

Clinical Analyais of Highwevys Grpup 2.f_Eatgt£g

Name of the estates,

Age group.

1/2-2 years.

Cloudland.

M

Highwavye.

M

F

F

Manalaar.

Upper Manalaar.

M

M

F

F

Venniar I.

M

1

9

4

10

3

3

em

me

cm

-

8

•

*

1

8

M

F

M

F

12

11

4

10

8

cm

7

•

3

•m

7

••

me

me

em

me

**

3

me

m.

cm

*

*

—

•

me

•

—

*

*

me

1

—

1

1

•

—

6

15

14

11

13

3

3

cm

em

6

•

12

1

me

cm

-

—

6

•

■»

1

5

m»

«•

—

^7'

me

cm

cm

me

cm

8

1Venniar III.

J

I

Total number of

children.

Venniar II.

F

Hf;lr.

1 a

Jm

11 bo

wF

1

d

5

1

*

1

-

Fee?.

2 a

2 b

•»

me

«=»

-

-

1

3 e

*

*

■e

-

1£®£.

3 a

•

4 a

am

C»

4 b

•

•

6 a

6 b

*

8 a

*

am

me

me

•

-

am

-

me

I

line.

i

me

1

7!*

I

—

A*

*

<m

cm

1

-

1

am

me

—

1

me

*

•

*

w

1

1

Teatfa.

f

P

I

cm

1

•

Skin.

I

8 b

/

4

*

-

•fl

am

me

T

1

K>

me

Wail.

9 a

-

i

Muscular &

Skeletal

systems.

11a

11 d

11 g

11 h

11 f

j

/

cm

cm

*

me

me

me

cm

-

—

*

am

me

me

me

cm

me

me

me

*

am

me

me

«.

1

cm

m

ami

*

*

•

*•'

-

•

-

*

1

1

—

me

1

*

3

«

i

2

■m

me

-

*

Otitis.

0

1

1

j1

2S21.

|=

Scab!eg.

i

1

1

1

1

1

2

-

me

- ■

-

-

i

i

Pyoderma.

2

1

me

am

*

1

—

-

ir

-

•

8

-

*

•

-

-

•

-

-

-

Fb

-

-

•

me

-a

-

-

-

-

•*

•

-

*

•

F

Me

i

*

*

—

cm

I

-

j

-

-

•

•

i

-

1

-

•

I

“

.

-

—

*

T

!

-

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT.

Clinical Analysis pf Hi^hwavys Group, of &afatep

Name of the estates.

Age group.

2-2/2 years.

Cloudland.

M

:

Upper Manaleer.

Highwavys.

T

M

F

M

:

<

F

Venniar I.

Manalaar.

M

F

M

Venniar III

Venniar II.

F

M

F

M

F

3

6

,0

2

2

7

1

i

t

3

12

13

9

8

3

6

a*

10

•

•

2

•

—

-

4

-

1

6

I

i

«•

1

s

7

2

5

9

3

-

’

—

-

;

—

1

*

*

5

—

1

-

-

-

—

—

I

-

—

-

■

I

A.

-

-

face.

2 a

2 b

1

-

-

1

-

I

Eyes.

—

-

I

I

-

I

3 a

3 d

-

•

-

-

-

—

1

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Lips.

-

-

•s

—

-

-

*

-

-

-

4 a

4 b

Teeth.

I

6 a

6 b

-

1

1

—

-

Skin.

8 a

8 b

-

-

1

2

—

—

1

1

1

—

1

-

-

1

-

2

I

—

-

-

1

1

-

-

-

-

-

*

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

—

•m

*

*

—

—

—

_

*

—

—

a*

-

-

-

-

-

*

•

-

«*

1

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

1

—

-

-

-

-

-

1

-

-

Nail.

-

-

Muscular ft

skeletal

systems.

—

—

-

1

••

—•

—

1

!•

2

—

1

-

«>

•

-

-

Fyoderma.

f

lrti.

■Scabies.

S

-

-

-

2

1

—

—

-

-

-

-

•

-

-

•

-

-

-

•

•

I

-

1

-

1

_

-

—

i

1

-

—

*

-

1

—

•

-

-

•

-

-

-

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT.

Clinical Analysis of Highwayyg Grpup. of ggtat^p..

Name of the estates,

V

( Age group,

; if 2 - 3 years,.------------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------------- ~-------Cloudland•

M

Manalaar.

Upper itonalaar.

Highwavys.

|

Venniar I.

Venniar II.

Venniar III,

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

IH

F

M

>■

M

F

5

9

10

12

11

8

12

3

3

4

5

10

5

2

•a

7

—

2

-

3

3

4

2

1

—

as

■s

as

*

mb

<=»

1

*

*

3

•B

1

•

•B

2

■a

*

1

*

1

—

-

*

■

Total number

of children.

2

i

Hair.

1 a

1 b

1 c

1 d

1

*»

—

2 a

2 b

*

«-

—

*

•»

•B

SB

MB

MB

-

*•

?£££*

as

—

—

•

-

*

M

T

-

—

«M

-

BM

*

*

*

1

as

I

*

*

“

I

Eyes ,

•

-

*

•

•

-

M

SB

n.

as

*

•

as

3 a

3 d

*

!

se

*

as

mb

•

-

Lipp.

4 a

4 b

an

M

<s»

as

•s

1

1

1

•

—

1

,

■B

*

•

•U,

*

1

MB

I

Teeth.

I

6 a

6 b

*

1

1

-

—

-

-

MS

1

st

as

—

•

Skin.

SB

8 a

8 b

■SB

1

*■

1

n

1

•

1

1

1

j

Mail.

*

09

1

•

I

i

a>

9 a

Muscular &

Skeletal

pystemp.

11

11

11

11

11

a

d

g

h

f

MB

—

•a

•»

•

!

0

—

*

«B

as

an

m

■»

*

•s

as

■a

*

*

*

*

'SB

*

•i

-

•

1

1

-

*

*

•

—

•

-

-

1

-a

—

MB

1

*

-

-

as

-

SB

1

-

as

SB

«a

*

SB

I

as

SB

a

•a

1

MB

MS

•

*

*

*

»

MB

M.

-

•

•

*B

•

SB,

-

«W

1

•

SB

*

•

i

*

!

Pyoderma.

£

LRTI.

-

—

M

•

!

1

-

as

’

-

-

-

•

•

-

*

!

I

1

Scabjeg.

S

-

-

—

Pb

*

-

•

Mo

|

I

—

1

I

-

SB

-

•

*

SB

-

-

•

-

-

-

-

•

*

-

•

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT .

Clinical Analyste c>f E ighwavys_ Group Q^-EstgteB•

Name of the estates •

Age group.

3-4 years.

I

■

.

;

Upper Manaleer.

Highwavye.

Cloudland•

Venniar I.

Manalaar.

F

M

F

I

M

F

M

F

M

15

16

21

16

13

23

37

23

9

t

5

2

7

7

14

-

-

1

:

’

F

17

7

Venniar II. j

Hair.

17

6

Venniar III.

I

M

F

9

15

11

5

2

4

1

—

1

-

i

!

Total number

of childrezi.

a

F

:

■

2

1

b

a

r

•

1

,

1

d

-

Face.

2

!

—

*

-

-

i

2

•

2

1)

-

Eyea.

-

3

5 d

-

-

-

-

1

-

-

-

i

-

i

1

I

-

I

2

I

-

1

-

2

”

Lips.

4 a

4 b

Seeth.

6

6 b

B

—

—

*

•

—

2

3

2

1

2

-

1

2

1

—

SB

SB

—

—

w

1

1

•

3

-»

-

—

—

—

—

4

1

•

•

—

-

—

—

2

1

1

-

-

w

2

i

Skis.

8 a

8 b

-

—

1

SaU-

I

0

F

1

w.

—

—

*

—

*

«»

—

-

-

1

"•

1

-

2

3

-

-

2

1

1

*

2

*

I

*

2

1

i

—

!

—

*

1

—

—

*

*

*

—

1

*

I

i

2

1

1

-1

1

I

Sb

I

e

MB

i

-

-

1

-

-

-

-

-

I

'

1

5

i

I

I

2

1

■»

!

i

1

—

|

I

5

1

i

I

"

*

—

*

I

I

I

-

1

-

1

•

1

-

-

*

•

•*

•*

1

-

I

s

Eb

*

I

Scabies.

* i

1

3

I

FyodermiL.

LET I.

-

5

(

Muscular &

skeletal

systems.

otit14.

I

i

o

11 A

11 d

11 g

11 U

—

4

1

-

1

-

-

-

-

I

I

I

I

i

-

-

-

-

-

*

-

-

-

—

-

1

NUTRIIIONAL ASSESSMENT.

Clinical Analysis of Hjghwavys Group of JBgt^tes.

!

J

I Clcudlana.

.Ago group.

4-5 year

Iteme of the estates,

Eighwavys.

Manalaar.

Upper Manalaar.

!Venniar I.

Venniar II.

Venniar III.

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

M

F

K

F

6

13

23

20

15

13

37

48

7

8

13

22

8

16

a

b

c

d

•»

••

—

4

1

••

—

2

*

11

—

2

*

*

•

4

a

m

<•

11

-

—

«•

—

22

2

••

—

—

••

6

—

—

1

2 a

2 b

—

-

*

—

*

—

a.

—

-

*

«e

-

1

<»

—

3 a

3 d

-

-

<=>

1

-

1

Total number

of childrei1>

Sala:.

1

*

1

2

I

1

••

—■

2

*

i

*

*

face .

-

Syeg.

1

-

•

Teeth.

-

-

-

•

-

1 3

1

2

1

5

z

1

3

1

1

-

|

I

1

-

I

6

6 b

U

w

i

I

2

1

!

Iiips .

4

4 b

2

—

\

*

2

1

5

1

2

2

1

2

I

8 a

8 b

-

—

j

1

—

—

4

—

8

i.

2

4

r

i I

9a

—

-

-

-

•*

!

!

11

! i-

11

—

-

!i

-

-

—

—

Ptitis.

I

3

2

1

-

-

—

—

—

—

—

*

1

:

—

—

P

;

1

—

-

-

1

•

-

8

-

-

-

-

Pb

1

-

-

-

1

1

2

\

—

3

3

I

a.

* -

-

I

-

I

-

-

—

1

-

-

I

!

*

-

w

«a

i

1

1

-

2

-

1

i

—

-

1

j

I

flEpder^a •

1221.

’

I

-

•

0

2

.1

. -

I

i

i

iKpletal

gyptems.

d

S

h

f

-

- ’■

I

Nail.

-

;

-a

•

1

-

1

2

Scabies.

/'

Mo

-

-

■

-

-

I

-

I

-

—

-

-

.

—

•

-

]

i

•

-

2

KEYtHair.

1 a 1b1c1 d -

Lack of lustre Thinness end sparseness.

Dyspigmentation of proximal part of hair.

Flag sign.

Easy pluckability.

Face.

2 a - Diffuse depigmentation.

2b- Naso-labial dysseb&cea.

Eyes.

3a- Xerosis conjunctivae.

3d- Angular palpebritis.

Lips.

4 a - Angular stomatitis.

4b- Angular scars.

Teeth.

6 a - Caries.

6 b - Mottled enamel.

Skin.

8 a - Xerosis.

8b- Follicular hyperkeratosis, types 1

Mail.

9 a - Kollonyohia.

Muscular and Skeletal_systems.

11

11

11

11

11

a

d

g

h

f

0

P

LRTI

S

Pb

Me

ss.

27-2-1980.

- Frontal and parietal bossing.

- Knock-knees or bowlegs.

~ Eiseon chest.

- HariBson'e sulcus.

-

Otitis.

Pyoderma.

Lower Respiratory tract infection.

Scabies.

Mo Hue cum ContaglOB,„m.

and 2.

HEIGHT

Name o_C jj/S’ta'te/

Division.

0-3 months.

N

207

51.75

Total

Mean.

N

Total

Mean.

9 N

12 months

’Total

Mean.

GROUP___ ~___ 12121

1 yeat to 11/2 years.

172 years to 2 years.

Male

Female

Male

Female

NTT6tal~l "Flean? nTTo^ aTTean? -N~TTo^aI” "Mean N |T6EaI Mean?

9

525

58.3

5

314

62.8

5

342.5 68.5

7

501.5

71.64

9

638

70.9

9

695

77.2

8

628

78.5

5

272.5 54.5

9

532

59.1

12

786

65.5

13

892.5 68.7

9

639

71

13

921

70.84

4

298

74.5

0

751

75.1

Manalaar

8

423

52.88

14

841

60.07 12

770

65.16 24

1638

68.25 12

864

72

17 1188

69.88

15

1129

75.27

1016

72.57

Upper Manalaar

3

158

52.66

7

408

58.3

7

431

62.71

6

403

67.16 13

927

71.3

9

616

68.44

8

615

76.87 6

431

71.83

Venniar I (a)

3

153

51

5

291

58.2

3

187

62.33

3

195

65

2

129

64.5

5

350

70

4

295

73.75 8

580

72.5

Venial-

5

24-3

48.6

4

230

57.5

-

2

129

64.5

1

70

70

2

138

69

7

535

76.42 5

358

71.6

Veniar II

1

53

53

4

222

55.5

7

451

64.43

8

522

65.25 13

875

67.31

6

425

70.83 12

861

Veniar III

7

358

51.14

5

295

59

10

631

63.1

8

532

66.5

692

69.2

6

398

66.33

4

292

71.75 11

73

j' 10

805

714

73.18

71.4

1867.5 51.88 57

3344

58.67 56

3570

63.75 69

4654

67.44 67 4697.5

70.1

67 4674

69.76 63

4720

74.9 ; 72 5283

73.38

- .

-

-

70.8

74.2 ;!

J

73.3

I

(b)

Group Total:-

36

Deli Study

57.4

All-India.

Name o±'

Estate/

Division.

'

N

-___ HIGH WAVYS

Highwavys

Cloudlgnd

1

Mean.

AGE

6—9 months.

3 - 6 months.

Total

FOR

-

-

-

-

!

____2’7 2 years to 3_years .___

2 years to 2^/2 years.

-----_ ___

N

Total

Mean.

N

Toia.1

Mean.

Total

N

Mean.

Total

N

Mean.

N

Total

Mean.

2002.5

87.06 37

3476

98.94 48

4923

102.56

2017

87.69

15

1400

93.33 13

1213

93.30

6

520

86.66

4

378

94.5

289

96.33

15

1325

88.3

82.8

21

1879

89.47

Manalaar.

6

466

77.67

552

78.86

8

681

85.13

12

982

81 .83 36

3309

Upp er: -Manalaar.

9

706

73.4

8

613

76.62 12

980

81.66 1 1

883

80.27 13

1135

1

80

30.0

4

301

75.3

2

169

84.5

77

77.0

792

88.0

1

6

,463

77.17

47

3704

78.8

Groy.p Total:-

Delhi Study.

All-India.

73.2

74

74.0

1

;

90

90.0

2

171

85.5

8

684

85.5

230

76.67

4

■

318

79.5

3

241

80.33

17

1497

10

756

75.6

i 10

830

83

5

4oo

80

88.06

I 87.07

52

4041

77.7

48

3971

77.9

i

82.73 49 3988

81.39

81 .8

85 • 8

1306

13

Mean,

87.30 23

81.2

828

___

Total

89.43 23

406

10

Veniar III.

N

94.4

5

82.33

77.89

Mean

94.35

31

741

83.0

87.7

Female

Total

1887

162

9

83

N

1227

2

81.38

701

Mean •

95.12 20

76.2

1058

1

4 years to 5 years.

Male

91.3

457

13

9

1403

-

L

548

6

80.83

Veniar II/

[16

Total

-

2188

78.3

970

9

N

=

6

235

Veniar l/b)

-

. 85.62 23

3

12

1

69.3

-

1370

Cloudland.

(^)

-

M ale___________________ Female_________

Highwavys.

Veniar I

-

_______ 3 years to 4 years.___

Male___________________ Femal_________

Female

Male

69.0

66.5

63.O

10

16

'

1

92

92.0

3

272

90.66

473

94.6

9

780

86.67 13

1233

94.85

12

2046

93.0

11

972

88.36

728

91

16

1493

93.3

135 11,927 33.35 105 9156.5 87.2

86.2

84.9- '

109

10,223 93.79

■

93.9

140 13,551

96.79

92.6

for

0

3 months.

3

-

Me an.

N

age

9 months.

6 months.

6

Total

Me an.

N

Total

Me an •

Name of Estate/Div.

N

Total

HIGIIUAVYS group -

-

1979.

,9 - 12 moriths. _ 1_ Year to 1''/2 years.

Male

Female

N" "To^al

w“ "ToTal"1 "Mean7

Mean.

N Total Mean.

11'2 years to 2 years.

Female

Male

FTotal

ean. "n To^al" Mean

.Cloud Land

4

17.5

4.33

9

5-1.7

5.74

5

32.5

6.54

5

37.0

7.4

7

55.7

7.96

9

69.2

7.7

9

84.6 9 4

8

74.7 9.33

High.'.Wavys

5

18.8

3.76

9

48.3

5.37

12

80.1

6.68

13

89.3

6.87

9

76.0

8.44

13

102.5

7.83

4

34.3 8 57

10

84.5 8.45

Manalaar

8

33.4

4.18

14

79.9

5.71

12

78. 1

5.58

24

185-9

7.75

12

97.9

8.16

17

131.5

7.74

15

138.4 9 23

14

1 14.2 8.16

Upper Manalaar

3

8.83 2.94

7

33.9

4.84

7

43.5

6.21

6

42.3

7.05

13

103.6

7.96

9

66.6

7.4

8

72.8 9 06

6

50.1

3

19.4

6.46

3

19.4

6.46

2

14.6

7.3

5

35.5

7.5

4

33 • 2 8 3

8

66.2 8.27

5

39.2 7.84

Veniar I

(a)

3

11.1

3•7

5

26.8

5.3o

Veniar I

(b)

4

19.6

4.9

-

-

-

2

13.4

6.7

1

7.5

7.5

2

15.0

7.5

7

62.8 8 97

17.6

4.4

7

46.9

6.7

8

54.3

6.79

13

100.0

7.69

6

45.4

7.57

12

97.7 8

5

25.2

5.04

10

62.1

6.21

8

59.6

7.45

10

78.7

7.87

6

42.1

7.02

4

32.1

57

311.0

5.46

56

362.6

6.48

69

501.2

7.26

67

533.9

7.97

67

507.8

7.58

63

-

-

-

-

-

-

7.8

-

-

7.3

-

-

5

17.5

3 •5

Veniar II

1

4.3

4.3

Veniar III

7

28.0

4.0

Group Total;Delhi Study

36

-

All-India

139.43 3.87

-

4.8

-

-

6.2

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

2 Years to 21/2 Years.

Name of Estate/Div.

"

6.9

21/2_years

Female

"Total] Mean.

Mai.e

“n“‘ tsezi "Mean.

-

N

-

-

7-6

-

-

-

-

-

to 3 Years.

3 Years to h years.

8 03

88.8 8.1

78.6 7.86

10

555.9 8 82 72 596.3 8.28

8 5

-

-

-

-

8.0

4 years to 5 years.___

Female

Male

iBSal" "Mean? " n“ "Total" "Mean

Female

"ToTal" "Mean?

Male

"Total" Mean •

-

14 11

8.35

_Male

Female

—v" "Total" Mean? "n"]T6T al Mean

Cloud Land

3

27.7

9.2

6

53.3

8.9

2

18.8

9.4

5

50.5

10.1

15

167.3

11.2

16

177.7

11

1

6

12.68

13 198.8

12.2

High Wavys

12

121.1

10.09

13

121.1

9.31

9

88.8

9.36

10

97.6

9.76 21

255.7

12.17

16

178.6

11

16

23

304.0 13.21

20 257.6

12.88

76.1

Manalaar

6

54.9

9.15

7

67.2

9.6

8

88.6

11.07

12

124.2

10.35 37

443.3

11.98 23

272.8

11

86.

37

505.7 13.66 48

638.7 1 1330

Upper Manalaar

9

88.3

9.8

8

72.0

9.0

12

124.9

io.4o

11

111.4

10.12 13

155.1

11.93 23

269.9

11

73

15

195.0 13.0

13

171.0

13.15

43

53.0 13.25

3

45.1

15.0

3

36.3 12.1

5

65.9

Veniar I

(a)

1

10.4 10.4

4

36.6

9.15

2

20.7 10.5

1

10.0

10.0

9

105.5

11.72

6

68.6

11

Veniar I

(b)

1

10.7 10.7

1

8.1

8.1

1

12.1

12.1

2

22.4

11.2

8

84.6

10.57

1

12.5

12 5

Veniar II

9

85.2

9.47

3

28.4

9.47

4

38.0

9.5

3

30.1

10.03

17

200.0

11.76

9

100.1

11

12

13

106.8 12.98 22 282.8

Veniar III

6

58.8

9.8

10

89.3

8.93

10

106.15 1 0x62

5

47.7

9.54 15

167.4

11.16 11

127.1

1 1 55

8

97.5 12.19

493.9

10.08 135

Group Total;-

47

457.11

Delhi Stury.

All-India.

-

9.73

52

476.9

78.2

-

-

77.9

-

-

-

-

9.15

48

-

498.1

10.38

-

81.8

-

-

49

-

85.8

1573.9 11.7

105

1207.3

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

86,2

-

-

1 1

5

109 1436.4 13.18

16

84 9

-

93.9

209.6 13.1

140 18?) .5

-

13.8

12.85

13.07

-

-

-

92.6

CHEST

lame of Estate/

Division.

Total

Mean.

N

Total

Mean •

N

Total

Mean.

- high wavys gaoup - 19?9»

N

Total

Mean.

1 year to 11/2 years.

- TotalMaAean.

Tota?a^Fiean.

N

N-

9 -

6-9 months,

3-6 months.

0-3 months.

N

CIA CL 2-xE2?A^=~~- CL I1 'oi< age

12 months

44.2

N

11/2 years to 2 years.

Totafle]ftean.

Me an •

N

Cloud Land.

4

143.5

35.88

9

352

39.1

5

203

40.6

5

217

43.4

7

309.5

9

337.5

43.1

9

426

47.3

8

372

46<2

High Wavys.

5

180.5

36.1

9

349

38.78

12

505.5

42.13

13

558.5

42.96

9

397.25 44.13

13

574

44.15

4

191.5

47.87

10

454

45.4

Manaliar.

8

282

35.25

14

545

38.93

12

488.5

40.7

24 104-9.5

44.15

Upper Manalaar. 3

110.5

36.83

7

272

38.85

7

287

41

6

(a). 3

101.5

33.83

5

195

39

3

122

4o.66

3

(b).

Veniar

(l)

43.73 12

519.5

43.29

17

732.5

43.08

15

663.5

44.25

14

574

249

41.5

13

569.5

43.8

9

382

42.4

8

365.5

45.68

6

260.5

43.41

125

41.66

2

84.5

42.25

5

21 1

42.2

4

176.5

44.1 2

8

349

43.63

83.5

5

1 71

34.2

155

38.75

-

-

2

41.75

1

44

44

2

87.5

43.75

7

323

46.85

5

221

44.2

Veniar II.

1

35

35

4

152.5

38.13

7

301.5

43.1

8

339

42.4

13

575.

44.2

6

267.5

44.58

12

549.5

45.79 11

493

44.82

Veniar III.

7

247