NUTRITION & CHILD HEALTH

Item

- Title

- NUTRITION & CHILD HEALTH

- extracted text

-

... ..

.

r Sb :

- - X.RF_NUT_5_A_SUDHA

....... .

di

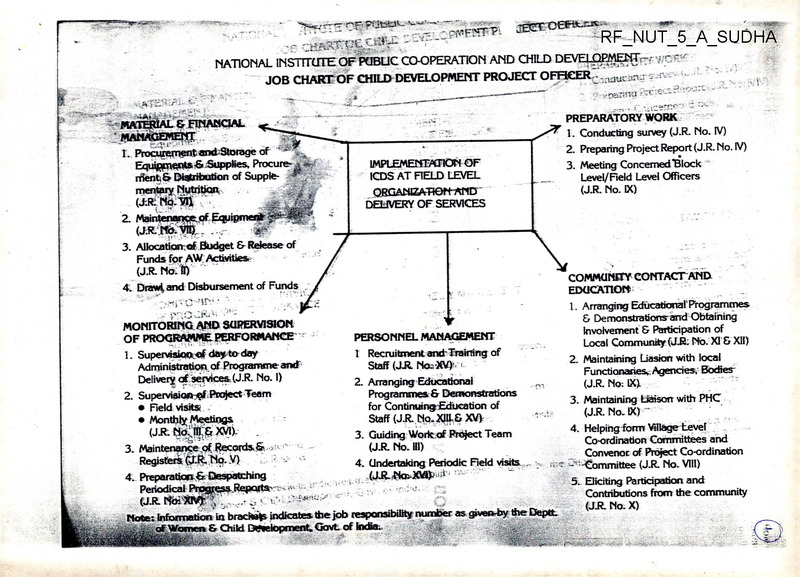

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC CO-OPERATION AND CHILD DEVEipP^NT^z v T, ■'

JOB CHARTOF CHILD DEVELOPMENT PROJECT OFHCER7 0 ;_ _ —--------- - :yganua rTCX'-..^

4

? ,r.a*TkF,'’3

PREPARATORY WORK

r 1. Conducting survey (J.R. No. IV)

-‘5- ■

—• *

-r

' MMWOEWEftT

I. Procurement and Sorage of

Equipm^rts -& Supplies, Procurerrient;& Distribution of Supple

mentary Nutrition

(J;R:Nb.Vll

2. Preparing Project Report (J.R. No. IV)

--

IMPLEMEHmFJON OF

ICDS AT FIELD LEVEL

ORGANIZATION-AND

DELIVERY OF SERVICES

3. Meeting Concerned "Block

Level/Field Level Officers

(J.R. No. IX)

2. Maintenancnof Equi|

(J.R..M&.VI1J,.

3. Allocation of Budget & Release of

Funds for AW Activities.

(J R. No:!)

COMMUNITY CONTACTAND

EDUCATION

1. Arranging Educational' Programmes

& Demonstrationyand Obtaining

Involvement & Participation of

Local Community (J.R. Mb. XI & XII)

4. Drawl, and Disbursement of Funds

-

c-'ir-’ • - -

:.!r:

■

MONITORING AND SUPERVISION

OF PROGRAMME PERFORMANCE

1. Supervision®! day to day

Administration, of Programme and

Delivery of services (J.R. No. I)

2. Supervision^.Project Team

• Field visits

• Monthly Meetings

• /

-

PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT

1 Recruitment and'Training of

Staff (JR. Nos'XV)4 1

2. Arranging Educational

Programmes & Demonstrations

for Continuing Education of

Staff (J.R NQ.XJIL& XV>

3. Guiding Woric of Project Team

(JR. No. HI)

2. Maintaining Liasion with local

Functionaries, Agencies, Bodies

(J.R. No: IX).

3. Maintaining Liaison with PHC

(J.R. No.lX) ~

4. Helping form Village Level

Co-ordination Committees and

Convenor of Project Co-ordination

4. Undertaking Periodic Field visits .. s {S-e S‘-^ommittee (JJt No. VIII)

4. PreparatiopfeDespatching

5. Eliciting Participation and

-Contributions from the community

UJt NoiXlVfc v

< v ....

■

(J.R.N0. X)

Note : Information in bracIMs indicates the job ^responsib.lrty number as grver^ the Deptt

of Women & Child D^elopment, GovL of Incfia.

(jjty«&xyik

F5C..i5l'- .r '

3. Maintenance of Records & .

Registers (JIR.N0. V)

.. ;

L

•

--T

'

< . , .

■ .

JOB RESPONSIBILITIES OF CDPOs

SKILLS

PREPARATORY____TASKS/SUB-TASKS

(F”

(D___________

WORK

1. Conducting a survey

(J.R. No. IV)

y

1. Identification of villages/

wards/families/beneficiaries for setting up AWs

1. Collecting information

about villages, analysing

and compiling information

2. Creating community

awareness about the

1CDS programme parti

cularly among the

Panchayats, Mahila

Mandals, BDO, MO,

Block Samiti and other

voluntary organisations etc.

2. Communication and

public speaking with

different categories

of persons

3. Obtain concurrence for

location of AWs

3. Elicting support from the

community

4. Help and supervise

AWWs/Supervisors in

i. conducting a survey

ii. filling up survey register

iii. compiling survey

information

iv. selection of benefi

ciaries

v. updating survey data

vi. compiling vital statistics

4. Talking to people to elicit

information, taking inter

views recording informal

interpreting information

r

•:;5

I

5. Writing project report

6. Interpreting survey data

7. Planning follow up actio

■

W

2. Preparation of project

report with necess

ary base-line infor

mation

5. Compile survey infor

mation collected by

AWWs/Supervisors, Prepar

ing project report (profile),

submitting to Programme

Officer

3

.

■ v

-

6

(3)

(2)

(1)

I

‘ti

a

I

Community Contact and

Education

1. Contact local people, local

bodies, different agencies and

organisations

1. Obtain inuoluement

and participation of

local community in

the ICDS

programme and

arrange educational

programmes and

demonstrations.

- BDO

— Panchayat

— Mahila Mandals

— Youth Groups

— Voluntary Organisations

— Primary School

— Rural Development

Programme functionaries

— Public Health Engineering

(water & sanitation)

— District Extension and

<»

Media Officer

(JR No. XI & XIII)

2. Maintaining liasion

with local

functionaries/ agencies/bodies.

1. Talking to local people,

addressing larger

gatherings, communicating

correct messages

2. Establishing linkage with

different people/

organisations agencies

etc.

I

3. Organising educational

publicity programmes,

melas etc. for community

Explain the programme

to them

'I

2. Discuss with local community

their expectation from the

ICDS project.

(JR No. IX)

.•jfB

3. Identify and suggest areas for

people's participation, discuss

with local people the help

they can render in the ICDS

programme.

4. Encourage people to

participate in the ICDS

programme and to contribute

towards its successful

implementation by

i.

ii.

4

s -al

availing services

providing shelter, food

supplements, waste

material etc.

n

5. Arrange educational

programmes/ publicity

meetings/exhibitions/meals

etc. for encouraging

involvement of local people

and for creating awareness,

utilizing the funds available

under IEC for this purpose.

4

■■

■

'^9

II

<n

.........

(3)

(2)

_________

■ . .................. ..

■

I

6. Mobilize community

resources for strengthening

services.

I.

— mothers,

artisans

— local groups

— adolescent girls

primary school teachers

— material resources

■

7. Work out Indicators for

monitoring people’s

participation in ICDS.

8. Make periodic visits to AW

centres to assess the

participation of the

community.

I

3. Maintain functional

liaison with Primary

Health Centre

(JR No. IX)

I

i

f.

9. Contact MO for

M-

— health check ups

— immunization

— timely supply of medicine

kit and training of AWWs in

Its use

— joint visits to project area

10. Work out an action plan for

effective delivery of health

services.

*0

:1

11. Identification of ‘at risk’

children and mothers

I

12. Attend meeting of district

medical adviser/CMO

i

1

4. Convene project

coordination

committee

(JR No. VIII)

13. Form the project

coordination committee

14. Brief members about their

role and responsibilities.

1. Conducting meeting.

■

2. Recording minutes of

meeting.

' ■ ^9

15. Prepare agenda items, fix

date of meeting, convene

meeting, help to conduct

meeting and prepare the

minutes.

§

I-'.

I

5

■••yk

1 SB

vs?

' 'Mil

(3)

(2)

(1)

«

16. Take follow up action on the

decisions, orient

Supervisors/ CDPOs/ AWWs

about decisions taken.

5. Help in formation of

village level

coordination

committees

(JR No. XII)

17. Identify local influential

persons for co-opting in the

village coordination

committee.

18. Brief members about ICDS

purpose of committee and

their role

19. Orient supervisors, ACDPOs,

AWWs about the method of

conducting the meeting

20. Organise the first 1-2

meetings of the coordination

committee

1. Collecting information about

people who can be made

members of the committee

2. Convening meeting of the

committee

‘•w

3. Recording minutes of

meeting.

4. Communicating with people

n

■■■

21. Help wherever necessary to

fix dates of further meetings,

convene meeting and record

minutes

r

i

V;

1

22. Plan follow up action on

decisions taken

23. Involve committee members

in the activities of AW Centre

6. Obtain contribution

of local community

for

bullding/materials

(JR No. XI)

Personnel Management

1. Recruitment and

training of staff

(JR No. XV)

24. Help AWW to obtain

accomodation for the AW

centre

1. Identify and prepare a list of

eligible AWWs/Helpers as per

the prescribed qualifications

2. Arrange for selection of

AWWs/Helpers

i

v

J

■’I

1. Preparing statements of

eligible AWWs/Helpers, their

qualifications and

experience, untrained/

trained workers etc.

Form Selection Committee,

hold interviews for selection.

6

,’usS

'll

(3)

(2)

(1)

3. Issue appointment orders to

AWWs/Helpers

2. Conducting interviews for

selection of AWWs/Helpers

4. Make a list of untrained

ACDPOs/ Supervisors/AWWs/

Helpers and send

requirements of training to

the programme officer

3. Drafting appointment

orders, deputation orders

etc.

4. Conduct sessions during

orientation training of

AWWs/Helpers/Supervisors

S ACDPOs

«

5. Depute untrained

functionaries for training and

trained functionaries for

refresher courses.

6. Organise short term

orientation training at project

level for newly recruited

ACDPQs/Supervisors/AWWs/

Helpers in case a job training

course In not due

immediately.

7. Intimate number of vacancies

of AWWs/Supervisors/

ACDPOs to Programme

Officer.

f

s

■

■

■■

■

’ ■ -fi'-ri:/

■..-'WtJ!

?

■<

8i Fill up vacancies/make

; •

arrangements In case of long

leave by project Staff

I

♦

9. Provide advance to

AWWs/Helpers before they

proceed for training

10. Take session in training

courses for Supervisors/

AWWs/Helpers*

1

2. Arrange educational

programmes and

demonstrations for

staff development

(JR No. XIII & XV)

11. Identify areas/services which

require to be strengthened In

the block on the basis of

I. visits

ii. performance in the field

iii. scrutiny of records and

registers

iv. information from

MPRs/QPRs

1. Demonstrate appropriate

methods of organising

activities, growth monitoring,

conducting meetings etc.

,z

2. Scrutinizing MPR data for

planning follow up action

3. Motivating functionaries for

service delivery

.. « J

• Circular No. 15-3/85 CD dated 23 February 1989

7

1

I

i.

__Jl_

!

e

I

i ■

(3)

(2)

111

-

4. Supervising delivery of

services by field

functionaries

&

F

■

12. Demonstrate/arrange

demonstrations, Invite

resource persons, local

artisans etc. to build skills of

AWWs/Supervisors/ACDPOs

In conducting pre school

activities, growth monitoring,

community meetings, home

visits, mahila mandal

meetings etc.

•

■I

1

g1

13. Develop the office of the

CDPO as a resource centre*

H

14. Obtain material like picture

books, teaching aids, play

material, reference material

for the resource centre

'W

15. Ensure the utilisation of

material by ACDPOs/

Supervisors/ AWWs

■I

16. Circulate material from the

resource centre among

different AW Centres to

Introduce variety in the

programme

f'

i

17. Motivate AWWs/Supervisors

and ACDPOs to fulfil their job

responsibilities utilizing

competent/experienced

workers as resource persons

X

r

' ..•>

'’S'

19. Identification of gaps/lacunae

for strengthening service

delivery

•4

-

18. Make a list of AW Centres

according to their

'

performance

■'

* National Policy of Education, 1985 POA

4

■■

11

■

i—4

8

■

-

■

■<.

■

.

;r

V-

..

/■

■■

\

«

(3)

(2)

(1)

■

s

20. Identification of difficulties in

supervision

'

3. Supervision of

project team

through project

meetings

21. Arrange project meetings at

the project office

(JR No. Ill)

■

I. strengthening delivery of

services

H. enhancing skills

iii. improving supervision

24. Set goals/targets for

achievement in consultation

with project functionaries

25. Plan a monthly tour

*

programme and submit to

programme officer

4. Guide the work of

the project team

1

(JR No. Ill)

26. Make periodic field visits to

AW Centres. Use the

following to observe the work

of AWWs

‘

.

. :• - -V

23. Plan follow up action based

on the reports of field visits

for

■

■■

■

22. Plan the content for

discussion during the

meeting

-'■'1

■ -■ wa

■

if

•1

1. Prepare a tour programme

2. Demonstration of correct

method for delivery of

different services

■

3. Conducting a review

meeting

1

J

5. Undertake periodic

field visits

(JR No. XVI)

i. records and registers

ii. discussions with AWWs

iii. monitoring check list

lv. discussions with

f beneficiaries and

community

■

27. Monitor achievements against

set targets

fl

28. Appraise performance of

ACDPOs/Supervisors/AWWs

for filling up ACRs

I

. at

29. Conduct a monthly review

meeting

9

i

k.

-

i

I

F

.4

. ..

ife...

■/ft

30. Make arrangements for field

placement of trainee

AWWs/Supervisors/CDPOs/

ACDPOs*

I

Monitoring and

Supervision of

Programme

performance

.

1. Principal Executive

Functionary for

supervision of dayto-day

Implementation of

programme/services

(JR No. I)

4’

¥

2. Supervision of

project team

through field visits

(JR No. II and XVI)

•.J.:

i

1. Mapping AW Centres and

working out circles for

supervision

1. Know the

ACDPOs/ Supervisors/AWWs/

Helpers, their qualifications

and abilities

2. Observation and monitoring

delivery of services by

project staff

2. Prepare an annual action plan

for the project

- ’Ml

3. Skill In using checklist for

monitoring

3. Check the location of AW

Centres in the project and

distance/mode of travel to

different Anganwadi Centres

4. Discussion with project staff

for supervision during

project meeting

4. Distribute circles to

Supervisors/ACDPOs, making

them coterminus with the

circles of LHV

> . • iFw

5. Organizing project level

meetings, recording minutes^

of the meeting

5. Discuss with

supervisors/ACDPOs and

prepare a plan of supervision

of AW Centres including;

I. frequency of visits of

CDPOs/ ACDPOs/

Supervisors

IL time to be spent at each

AW Centre

lii. joint visits with medical

staff

II'

6. Discuss with

Supervisors/ACDPOs,

check lists for monitoring AW

Centres: pre school activities,

Nutrition and Health activities,

community activities**

*

1 Ir. '

6. Identification of

lacunae/gaps in delivery

of services

•.'S

• Circular No. 44/85 AT dated 7 March 1986

*• Checklist for monitoring AW* has been developed by NIPCCD

I. •

10

■i

i

(2)

(1)

(3)

7. Discuss with

Supervisors/ ACDPOs

information recprded |n

supervisors diary or check-list

1.

8. Make available records and

registers to AWWs/

Supervisors/ACDPOs as per

the requirement of the State

Govt./MlS Manual. Ensure

timely replenishment of

registers to AWWs/

Supervisors

3. Maintenance of

Registers and

records

(JR No. V)

i

9. Open all records/registers at

project office prescribed by

State Govt/MIS Manual

t

‘■S

1. Filling up different

records/registers, MPRs,

APRs and checking those

filled by the project staff

‘ ’S/

2. Compiling Information

in MPRs

'•O

3. Interpreting data from MPRs JO

4. Preparing a list of action

points for follow up work

10. Ensure maintenance of

reglster/records at the AW

level/project office

11. Maintain files as per

requirement

J

12. Check records maintained by

AWWs/Supervisors/ ACDPOs

and office staff

■

*

13. Guide AWWs/Supervisors/

ACDPOs to fill-up-records/

registers correctly

.<■

■

t

II

1

I

'1

4* Preparation of and

despatching

periodical progress i

reports

;

(JR No. XIV)

i

I

1

a

i

• ‘ ; f’ f; t

J

.i

1 I

17. Ensure filling up MPR of

AWWs, corripiling of

information by supervisors for

their circles

,

11

I

■ ■

16. Prepare a compilation of

circulars issued by the State

Government

/■o;>

v

■k.

15. Make arrangements for filling*

Up records/registers in case

of illiterate/semi literate

AWWs and orient them to fill

records correctly.

4

'

i"- ' ’ ' 'aia.

14. Ensure updating of

information in

records/ registers

»

.a.

I

■’'1

? •, r-?

■ w ;

■AJl.

(2)

(1)

t

18. Compile information from

MPRs and timely submission

to State Programme Officer

and Central Government

every month

I

19. Fill up APR and send to

Programme Officer and

Central Government

■

*r

(3)

■

£

!

I

s

20. Prepare list of action points

on the basis of MPRs for

strengthening service delivery

I

i:

■r

-

21. Maintain appropriate

discipline In office

i"

w

■-

22. Build a team of ICDS project

staff for effective

implementation of the

scheme. Maintain good

Interpersonal relationships

f

w-

I

■

I

Material and Financial

Management

t-..

I

I

!

|

L Procurement,

transportation

storage and

distribution of

equipment and

supplies and SNP

•

(JR No. VI)

2. Accounting for and

maintenance of

equipment

V

4

(JR Ho. VII)

’.V'Jt

i

;

'

1. Prepare a list of equipment

required for

— project office

— anganwadi centres

2. Send requisition for

procurement of equipment to

the Programme Officer

3. Make arrangements for*

procurement, storing

supplementary nutrition*

other equipment to AWC

4. Ensure uninterrupted supply

of SN to AW Centres

-

1. Working out the

requirements of the project

preparing lists and writing to

the programme office

2. Writing letters making

notings, draftings

3. Maintaining files, making

stock entries

4. Preparing accounts

statements.

5. Buidling a team spirit

6. Filling up ACRs

•z

■

5. Replenishment of medicines

in AW Centre**

t

6. Ensure entries are made in

the respective stock registers

• Circular No. 15 - 2/89-90 dated 19 May, 1989

Circular No. 15 - 3/85-CD dated 23 February, 1989

■

I

I

L.J

1

(1)

(2)

(3)

—

7. Make arrangements for

replenishing stocks/

maintenance of equipments.

3. Drawing and

Disbursing Officer to

allocate budget and

release of funds for

AW activities

(JR No. II & X)

■

: :

8. Send requisition for release of

funds for ICDS project

9.

Draw money for incurring

expenditure on salaries,

supplementary nutrition,

material etc

10. Incur expenditure from

contingency allocation for

material/articles for AWCs

<*

i

■

11. Ensure proper utilization of

funds and maintenance of

accounts of the project

12. To get prepared an audited

statement of accounts at the

completion of the financial ‘

year

13. Plan activities as part of the

IEC activities. Request for

release of IEC funds and

arrange for organising

activities

'W

■

-W

r-

I

••

■

4

I

Z

; fig-

/

fell

13

_ __ _

10.

FOR REPORTING

formats

—

—

Incidence as compared

format -I

to last month

4

AWW-S MONTHLY MONITORING RETORT FORM

1. Month

.

Other important events: (Pl. Tick)

-- -----

2. Year-------

Name of the Village where AW is located

Diarrhoea

b)

Live births

c)

Still births

d)

Total deaths

i)

0 to <1 year

ii)

1 to <3 year

(b) Total Population of Children 0 to 6 years---------------

iii)

3 to <6 years

Supplementary Nutrition was distributed at AW:

iv)

Pregnant Women

during delivery

(a) Total Population of the AW Area—- ----------------- -

5

6.

Previous month

a)

4. S.No. of AW

Number

(b) Moderately regular (c) Irregular

(a) Very Regular

(15-21 days)

(21+days)

e)

(<15 days)

7. Quality of Supplementary Nutrition:—

Good/Acceptable/Poor.

No. previous month

11.

No reporting month j

Pregnant Women

ii)

Lactating Women

Date

Reviewed by

Signature

ii) Sector

MO/LHV/HA (F)

—Grade III/IV

Immunisation carried out in the month. (Please Tick)

Note:

9.

Yes/No

i)

i) ANM/MPHW(F)

—Grade 11

BCG

Total No. of:

O.R.T. advised Yes/No.

8. NumberofmalnourishedchildrenO-6yrs,ascomparedtolastmonth.

Grade

Reporting month

DPT

IBSEiS

Yes/No

T.T.

Polio

Measles

DT

Yes/No

Yes/No

Yes/No Yes/No |

-i

-

102

i) The report is for the whole months (1 st to the last day).

The report should be discussd with ANM & LHV and

finally submitted to the sector MO at the sectoral meeting.

Jr

ii) Information on item S-6-7-8 and 10 (d) & (e) are same

as AWW is providing to CDPO for MPR.

••• •

Si

10S

MR.

-

FORMAT-2

'J.;1

State

Pincode

SECTOR MEDICAL OFFICER’S MONTHLY

REPORT ON SECTORAL MONITORING AND CON

TINUING EDUCATION FOR MONTH OF

Note:

1. Name of the PHC/CHC __________________________

2. The report is to be submitted to the project adviser (MO

I/C-PHC/CHC) on the 1st working day of the following

month.

2. Sector No. I/II/III/IV (Circle your sector No.)

3. Total Population of:

(i) your sector

1. Reference month Ist-last day of the month under

report.

________

3. All the MMRs received from AWWs in your sector till

last day each month should be submitted to MO I/C PHC

alongwith your report.

(Meeting must be held between 26th and last day of each month)

4. Please indicate the address in full including PINCODE

at which the quarterly check for your honorarium may be

sent.

(ii) Reported AWs in your sector

4. Sectoral meeting held on

at village

i

5. Topic discussed for continuing education

6.

Staff Position

No.

Sanctioned

No. in

Position

-

No. Attended

Meeting

) LHV/HA(F)

-t

ii) ANMs/MPHWs(F)

ii) AWWs

7. Did MS participate in the meeting Yes/No

a*

8. ^4o. of AWs visited by you during the month

9. Remarks, if any

Date

Signature

Name of MO

Designation

Sector/PHC

Town/Village P.O.

District

104

105

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

FORMAT-3 (A)

(MMR Proforma for Rural & Tribal Project Adviser)

Monthly Monitoring Report of Project Adviser (MO-I/C

Block PHC for the month of

19 (From 1st day to

last day of the month under report).

3. Name of the Block PHC/CHC

4. Name of the ICDS Project

_______________

6. No. of AWs in the PHC/CHC: Sanctioned

Reported

Functional

7. Population: (i) Total in PHC/CHC

(ii) Reported AWs (All Sectors)

a

Number of Sectoral Level Trg. courses organised by

9.

I ■

-

No of participants (All sectors)

Staff Position

i) Medical Officers

ii) LHVs/HAs(F)

iii) ANMs/MPW(F)

iv) AWWs

L

Grade II

12.

Quality of supplementary nutrition food:(Pl. Tick)

Good/Acceptable/Poor.

No. in

No.

Sanctioned Position

Total No.

DPT

BCG

POLIO

Mea Tetanus

Immunised

sles

Toxiod

in the PHC

1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd

(Reg.Women)

/CHC

1st 2nd

i) In the repor

ting month

ii) Total since

s

1st .April

14. Incidence of other important events:-______

Event

No. Previous month

all MOs.

b

No.Reporting month

13.

Immunisation performance figure (To be filled in from

available information at the Block PHC/CHC).

5. Total Number of Sectors in the PHC/CHC area

8

No. Previous month

________________________

Type ofProject(Rural/Tribai/U rban)

Sector Reported

Grade

Grade III & IV

I. Name of the State

2. District

10.

No. ofAWs where supplementary nutrition was distributed

(a) Very Regular(b) Moderately(c) Irregular

Regular

(2 l~days)

(15-21 days),

(< 15 days)

11.

Malnourished children 0-6 yr as compared to last month

No. Attended

Meeting

Not applicable

Not applicable

(a) Diarrhoea*

(b) Total Births

(c) Total Deaths

i) 0 to <1 year

ii) 1 to <3 years

iii) 3 to <6 years

iv) Preg. women

during delivery.

107

No. Reporting month

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

Yes/No

♦ ORT Advised

15 Supply Position:

Occasionally

Available

Regularly

Available

Supply Position

Not

Available

FORMAT-3 (B)

I

11

(MMR Proforma for Urban Project Adviser)

of

Monthly Monitoring Report of Project Adviser for the month

19. (from 1st day to last day of the monnth under report).

Iron & Folic Acid

1

Name of the State

Tablets_________________ _

2

(a) Name of the City(b) Urban Project

Medical Kits

he

Vit. ‘A’

Administrative3Deptt.: Corporation/Municipality/State Health

Deptt.

_ ______________________

16 (a) PHC Meeting held on

(b) DA Present Yes/No

Date_______________

■«

4

Signature

_

No. of AWs in the Project: Sanctioned

Reported

Functionnal

Name

5

CHC old PHC

Population: (i) Total in Project

Address

(ii) Reported AWs

(All Sectors)

Pincode

5

* Pl. indicate the address with pincode to send you the

quarterly cheque/Information foryour honorarium.

Staff Position

.No.

Sanctioned

No. in

Position

No.

Trained

Medical Officers

LHVs/HAs (F)

Note:

L

ANMs or MPHW (F)

Despatch the report to the Central Cell within eight

days after the end of each month.

AWWs

•

2.

Copy of MMR should be sent to the State Co-ofdinator

and Chief District Adviser within 8 days after the end

of each month.

7

is

biLM

108

No. of AWs wher supplementary nutrition was distributed:

a) Very Regular

(b) Moderately Regular

(c) Irregular

(21+Days)

(15-21 Days)

(<15 Days)

109

-

iI

Malnourished children 0-6 yr as-compared to last month

12 Supply Position:

.^ade________ No.Previous Month________ No.Reporting month

Supply Position

____________

■"•cade II

_ iTadelll & IV

Quality of supplementary nutrition food:

Good/Acceptable/Poor.

» Immunisation performance figure (To be filled in from avail-

ISotalNo.

DPT

13. Sectoral Training conducted

DA Present:

POLIO

.nnmunised

the PHC

Mea

sles

1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd

Tetanus

Toxiod

(Preg. Women)

1st 2nd

Name

PHC

Address

Total since

1st April

Pincode

Incidence of other important events:-

No. Previous month

No. Reporting month

^a) Diarrhoea*

<b) Total Births

uc) Total Deaths

0 to <1 year

ii)

?ii) I to <3 years

mi) 3 to <6 years

av) Preg. women

_____ during delivery.

* ORT Advised

Yes/No

Signature

Date

Intherepor

ting month

Event

Not

Available

Medical Kits

______

Vit. ‘A’

Iron & Folic Acid

Tablets___________*_____________

information at the PHC).

BCG

Occasionally

Available

Regularly

Available

* Pl. indicate the address with pincode to send you the

quarterly cheque/Information for your honorarium.

Note:

1.

Despatch the report to the Central Cell within eight

days after the end of each month.

Copy of MMR should be sent to the State Co-ordinator

and Chief District Adviser within 8 days after the end

of each month.

Yes/No

Il 1

< .^1

■

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

FORMAT-4

District Adviser’s Monthly Monitoring Report for the month of.

1. Name ofthe State

District

tW

Remarks about the following events as compared to last month:

al

Event ______ No. Previous Month No. Reporting Month

(a) Malnourished

Children 0-6 Yrs

Grade II

Grade III & IV

(b) Diarrhoea*

(c) Total Births

(d) Total Deaths

i) 0 to <1 year

ii) 1 to <3 years

iii) 3 to <6 years

iv) Preg. women

during delivery.

_________________

7. Remarks about the (a) Co-ordination with CDPO and (b)

Mr

I

2. Number of Sanctioned ICDS Projects in the district

3. Number of Operational ICDS Project under your charge

4. Number of Project Advisers under your charge

5. Details of Monthly Monitoring Reports received from the PHC

_

of Operational CDS Projects under your charge. *

No. of

Date of PHC Topics

Name of Name of Date of

Participants

Level Meet Dis

MMR

PHC

ICDS

cussed MO/LHV/

ing and

Checked

Projects

(Title CDPO/MS/

Continuing

and

Others

only)

despatched Education

Food Quality at AW centre:

Good/Acceptable/Poor

Signature

Name (in block letters)

Full Address

j

*w

Pincode_________ _________ _

Date-------- ------------------ -----Please do indicate Pincode in the address.

Note:

1.

2.

3.

The Monthly meeting in all ICDS projects under your

charge should be completed within 7 days after the end

of each month.

z

This MMR should be submitted to Central Cell within

11 days, after the end of each month;

Copy of MMR should be sent to the State Coordinator

within 11 days, after the end of each month.

113

112

£

INTETGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

FORMAT-5

Chief District Adviser’s Monthly Review Report for the month

of

19.

District

1. Name of the State

Population

2. Date of District Level Meeting (including ICDS)

6. Immunisation performance in the district (These figures are to

be filled from the available informatidn for children below 1 years

under UIP at the District Headquarters)____________________

TTto

No.

Pregnent

Measles

Polio

doses

immunised BCG D.P.T. Doses

women

1st 2nd 3rd 1st 2nd 3rd

in the distt

1st dose/

2nd dose

i) During

the month

3. Number of ICDS Projects in the District:-

(a) Sanctioned•

ii) Total Since

1st April

(b) Operational.•

4. Number of ICDS health functonaries in the District:-

(a) District Advisers

I

(b) Project Advisers

7. Remarks about the following events as compared to last month

No. Reporting

I No. Previous

EVENTS__________ month

(a) Malnourished Children

5.

Name of

District Adviser

No. of Proj

ect Adviser

reports

Name of

Name of.

Project Projects/PHCs despatched

Under his charge. by PAs in

the district to

Central Cell.

Grade II

GUI & IV

(b) Diarrhoea

(c) Total Births

(d) Total Deaths

i) 0 to <1 year

ii) 1 to <3 year

iii) 3 to <6 years

iv) Preg. women

during delievery.

i)

ii)

iii)

iv)

8. Remarks regarding food quality at AW centers: (Plase Tick)

Good/Acceptable/Poor

114

is

115

[g

..

..

9 . Number of participants in Distt Level Meeting.

< (a) District Adviser(b) Project Advisers

W:

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

FORMAT-6

(c) CDPOs (d), Distt. Social welfare

officers (e)

QUARTERLY REPORT OF THE DIVISIONAL ADVISOR

Others-------------- -—

10. Quarterly remuneration of ReceivedNot received

the District for MMRs

1. Name of the Divisional Adviser

Date

Distributed/Not distributed

Division

State

2. Report for the Quarter ending 31 st March/3 Oth June/3 Oth Sept?

31st Dec. 1994

Date

(Pl. Tick)

11. No. of Lectures taken for Social Welfare functionaries during

3. Date of Divisional Level Monitoring Conference

the month•

4. No. of districts in the division

Remarks if any

___________

5. No. of Chief District Advisors in the division

Signature

6.____________

Name of CDA District

Name (in block letters)

Designation

i-2?-’

Full Address

Date

Pincode

it

No. of Projects/PHC’s No. of CDA

Report sent

under his charge

in quarter

under

Review

yh;r: -

Please do indicate Pincode in the address.

Note:

1.

The District level review meeting of ICDS should be

combined with the routine monthly meeting at the

District Headquartef.

2.

This monthly Review Report must be submitted to

Central Cell within 21 days after the end of each month.

3.

Copy of MMR should be sent to State Coordinator

w ithin 21 days after the end of each month.

;'r----------;

’ -----------------

7. Participants in the Meeting:

(a) No. of CDA’s

______________

(b) No. of Programme officers

(c) State Level functionary

116

(If yes, write name & Designation)

117

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

(d) Senior Consultant

(Yes/No)

FORMAT-7

(e) Cbnsultant

QUARTERLY REPORT OF THE SENIOR ADVISER

If Yes, write names

1. Name of the Senior Adviser

8. District not Represented in the meeting

2. Report for the quarter ending 31 st March/3 Oth June /3 Oth Sept/

31st Dec. 199 (PL Tick)

9. Monthly Review of ICDS activities at divisional level done

regularly/irregularly

10. Lecture taken by consultant during the meeting (Yes/No)

11. Last Quarterly Meeting

3. (a) District Level meetings attended (Places and dates):

Held/Not Held

If held, date

12. Remarks if any

Name (block letters)

Designation

NOTE:

The Divisional Adviser is also supposed to review the

ICDS Programs with District Level functionaries dur

ing routine monthly meeting at the division.

2.

This report prepared for special ICDS session as "Quar

terly Divisional Level Monitoring Conference must

be submitted to central cell within in I month after the

Name of Distt

Date

Name of Distt

Date

Distt.

Date

Distt.

Date

Distt.

Date

Distt.

Date

Distt.

Date

Distt.

Date

(d) If you have attended any other ICDS meeting, please give

date and place:

4. No. of lectures for Social welfare functionaries delivered

during the reported Quarter

_______________________

5. Date when Expenditure Statement dispatched

end of each quarter.

A copv of the report should be sent to the State

Coordinator as well.

118

Date

(c) Field visits to PHC with ICDS projects in the quarter (Place

and Date):

Full Address

1.

Name of Distt

(b) Project level meetings attended (place and date):

Signature

Date

State

6. Specific recommendations if any

119

■■

1

!

4

■

Date

Signature

Name

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES

-

ft

FORMAT-8

QUARTERLY REPORT OF THE STATE COORDINATOR

Full Address

1. Name of the sate coordinator

2. State/U.T.

Note:

1.

At least one meeting or visit is expected each month.

2.

A brief report on 3 (a), (b) and (c) above should be sent

to Central Cell and State Coordinator.

3.

The quartertv report should be submitted to Central

Cell within 30 days, after the end of each quarter.

____________

3. Report for the quarter ending: 31 st Mar/30th June/30th Sept

31st Oct. 199 (PL tick)

4. Project Status (At the end of the reporting quarter).

Sector No. Sanctioned No. Functioning No. allotted for

monitoring

Central

State

Total

5. a) No. of functionaries in position at the end of the quarter

i)

Chief District Advisers (CDAs)

ii) District Advisers (DAs)

___________________

I

b) MMRs receipt position (at the end of reporting quarter)

!f

f-W

Month

in the

reporting

Quarter

CD As Report

DAs report

Expected I Received Expected Received Expected Received

1st Month

2nd Month

3rd Month

I

TOTAL

I

120

/ -

PAs(MOl/C PHC)!

Report

121

6. Consultants performance (at the end of the reporting quarter)

Participants

Training Course

No. of No.

3 day No. of MOs CDPOs Othen

2 day

1 day

Consul of

Regu courses

Refesher| Intro

ants at Qtly

held

the end Repts. Seminar ductory lar

of quarter Recd.______

Quarterly report of senior Adviser: Received/Not received

7.

8. No. of Lecture hours devoted for social welfare functionaries

during the quarter by:i) State Coordinator ii) Sr. Advisor

11. Specific problems/points (if any) related to above may be

mentioned below.

12. Paper cutting/'/assembly questions if any on ICDS the quarser

(Please attach copies thereof).

Signature of State Coordinator

Signature of ODA

Name

Name

Date

Date

Note: Quarterly report should be submitted to central cell within 45

days after the end of each quarter.

iii)ODA

iv) Consultants

v) CDAs

vi)DAs

9. Quarterly Expenditure Statement submitted to the Central Cell

by (Blease tick).

i) State Coordinator............ Yes/No

10. Monitoring Feedback from Central Cell, received for the

month of

in the quarter.

Action taken

by State Coordinator

Comments on

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

f)

Shortfall in MMRs

Staff Position

Sector Level

Supplies

Vital Statistics

Immunisation

122

-

123

^4? '

-

sw

I*

ii

i

<<

CL

& E

co >

E

u

u

z

S

co

UQ

O

>

w

co

o'

O

k.

E

o

I S

2 2□

_

>

w

Q

Q

u

5C

o

Q

Q-

ai

23

U

Os

i

H

<

ss:

o

E

c

5

c

V

o:

ta

c.

us

.£

£

•o

8

co

Q

X '

c.

H

O

•o'

s

•o

t»

Cl

£ 8

g

o

eg

a.

Almost at the very outset of ICDS in 1975, it was decided that

the academic community of the medical colleges of India would

constitute the ‘external investigator’ component for evaluation and

research. In this endeavour, as manias 29 senior faculty members

from 27 medical colleges, located within a reasonable distance to 33

experimental ICDS projects, unanimously resolved at a meeting

held at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New

Delhi in November, 1975, to act as its honorary' consultants with

twin role of (i) evaluation and research; and (ii) orientation and

training of the functionaries.

E"

o

d

3

Fl

55

00

t*-

o

o .E

4>

b>

4

8 $O

Z co

w

2

’8

i

u

s

k.

o

•8u.£

•o

o

Z

Qi

Q

U

sJp

2

EVALUATION AND RESEARCH SYSTEM

o

>

E

I

O

§ E

§ >

<

oi

k]

OD

V>

•E

£<

cc

Chapter in

‘i

O

co

Z

<z

SE To------

>

5

cn

z

o *

fl

•E

to

H

O

C

o

•o

o

QC

Vi

c/i

<

C-

.2

U

52

<

co

<Z)

5

-Si

o-

v

o

s

T

[

©

£fi s

J g

3

c

u

■g

These consultants agreed to work under the overall guidance

of the Central Technical Committee (CTC) of ICDS. The group

unanimously laid down following guidelines to achieve various

goals of ICDS:

■ r 'O ■

(a)

The evaluation and research methodology should be

updated from time to time through meetings of the

consultants and the academic staff of the CTC;

(b)

The evaluation and research should involve minimum

possible resources with active participation of the

postgraduate students and faculty members belonging

to the respective departments ofthe ICDS Consultants;

•5

>

o

Q

CH.

*Qi *Z Zs

it

•o’

c2

125

124

4

INAUGURAL

S^KEBttMML^^INAIiDNmNOWmDNSmCCCD

KEYNOTE ADDRESS

Early Childhood Care for Child Survival, Growth and Development in India

Patrice Engle, Section Chief, CD&N, UNICEF

In her keynote address, Ms Engle clarified basic concepts of the ECC-SGD framework. She answered 3 basic

questions - the what, why and how of this framework.

I.

WHAT characterizes a programme in ECCSGD?

Any programmatic effort that simultaneously addresses the three goals for children: survival, growth, and

development.

1.

Definition of the letters :

E : Early, prior to age of school entry, up to age 8;

C: Child, person from conception to age 18 (CRC definition);

C : Care, what family members and other members of society do for a child to facilitate the

processes of growth and development;

S : Survival, absence of mortality, and including health;

G : Growth, or an increase in size, which requires good nutrition particularly under the age of

two, and for women, during adolescence, and during pregnancy and lactation. Good nutrition

requires not only sufficient energy for growth, but also specific micronutrients such as iron,

zinc or iodine;

D : Development refers to an orderly process along a continuous path, in which a child learns to

handle more complicated levels of moving, thinking, speaking, feeling and relating to others.

Children vary enormously in their rates of development, but all cover essentially the same

sequence of developmental changes.

Developmental domains

Motor

The ability to move and to coordinate muscles

Cognitive

The ability to think, reason, and solve problems

Linguistic

The ability to communicate

Social

The ability to relate to other people

Emotional

The ability to feel and recognize emotions

2.

Characteristics of ECC-SGD programmes

It must include attention to nutrition, early childhood development, and health.

May have different entry points - e.g., health care, nutrition (not only food but also information),

growth monitoring, parenting classes, day care for children of employed women, special needs

children, community development, women’s empowerment groups, and care for children in special

circumstances (e.g., refugees).

UNICEF, Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26, 1999

14

SUSRBSIONAILSEMINAFgaNt INNOVATIONS Ir^ECCq

3.

Examples of programmes from India : Do they meet these criteria? Are these examples of ECCSGD programmes?

Midday meals

Public distribution systems

Pulse polio and vitamin A

Growth monitoring and promotion programmes

Balby Friendly hospitals

Preschools

Women’s thrift and credit groups

Parent support groups

Day care center for children of working mothers

that provides food and nutrition education as well as an

educational program

II.

Studies show that

a.

Nutrition is important for development. Even from the *IQ’ perspective, it has been seen that ♦

♦

♦

early nutritional supplementation in a nutritionally at risk population will result in significant

increases in cognitive development and IQ through adolescence.

a number of other nutritional interventions have resulted in long-term benefits of

approximately 10 IQ points such as •

Iodine : absence can lead to deficits in IQ or, if extreme, to cretinism

•

Iron affects cognitive functioning and increased attention.

•

Breastfeeding can result in higher IQ scores

•

Low Birth Weight without excellent family support is associated with lower levels of

physical and mental development.

India has one of the highest rates of malnutrition among children under 5; as many as 53%

of children are classified as mildly or moderately malnourished.

2.

Combined nutrition and early childcare programs have a greater impact on development

than either alone.

3.

A second reason for these combined programmes is that they may work better than the

individual programmes

a.

Increased motivation : A parent may be more likely to adhere to nutritional recommendations

that take time and effort if they believe that their child will become brighter because of feeding.

b.

Overlap of skills: A parent who learns to help the child develop better may also become more

attentive to the changes in the child, and identify children’s hunger cues or danger signs for illness.

HOW can ECCSGD programs be made most effective?

1.

Interventions should start early, and continue late

♦

♦

Any intervention to affect children’s nutritional status (as measured by height) must occur in the

first two years of life, preferably including the prenatal period.

Children who are born at term and weigh less than 2500 grams have a greater risk of being

shorter, and mentally delayed and are less likely to achieve in school than those born with a

higher weight. They are also more vulnerable to other risks.

Interventions for poor children from infancy onward show significantly greater effects at

adulthood than interventions that begin at ages 3 and 4.

UNICEF, Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26, 1999

J

yes

WHY do we think that ECCSGD is important for helping children develop

1.

III.

no

no

no

no

no

usually not

usually not

- depends on what they do

~

-

15

INAUGURAL

SUB^REBIONALSEMINAR GN INNOVATIONS1N£CCD

Newsweek, Nov. 1: Results from a carefully controlled study of early day care in North Carolina,

USA, showed that “poor children enrolled in high-quality day care from infancy do much better

academically and economically than low-income kids who don’t get that initial boost. As adults,

children who received the intervention were more than twice as likely to attend college and be

employed. “Craig Ramey, who did the study, concludes, “ It has become crystal clear that if you

wait until age 3 or 4, you are going to be dealing with a series of delays and deficits.”

Combining cognitive enhancement and food supplementation has a significantly greater effect

on children’s development than either one alone among children less than 24 months.

Grantham-McGregor in Jamaica found that home visiting to increase cognitive skills plus

supplementary feeding among 12-24 month old stunted children in Jamaica resulted in greater

effects than either home visiting or supplementary feeding alone. But the greatest long-term

effect was seen for the group who received the educational stimulation.

2.

Interventions should be culturally appropriate and be consistent with what families want for

their children.

Families’ values for their children often depend on how they earn their living and what they think that

their children’s chances of survival are. Based on these values, parents have investment strategies

fortheir children that make sense to them. We must understand them in order to build on them.

The way those families must support themselves, and children’s chances of survival influences what

parents want from their child. These conditions also affect parents' investment strategies with their

children, or their child-rearing patterns.

Many families are in transition - they move to urban areas, begin to change their desires for their children,

begin to replace farming with wage labor. Schooling may be much more important than before. As their goals

for children change, parents may need help in learning how to achieve the new goals. They also need support

to keep valuable child-rearing traditions that may disappear. So, we should be aware of where in this transition

families are as we design programs. We should respect parents’ goals for their children, and assist those

whose goals are not in agreement with their behavior (e.g., valuing obedience and quiet, while wanting children

to do well in school).

IV.

Where do we go from here?

A.

Develop ECC-SGD perspective in

Growth monitoring and promotion programmes - incorporate assessment and recommendations

for psychosocial care ((Indonesia)

Baby Friendly hospitals - improve newborn care for development , such as touch for LBW

babies, contact with mothers including those with c-sections, showing mothers the abilities that

children already have at birth (USA)

Preschools - provide information for children and mothers on appropriate foods (helps with

inappropriate food choices)

Day care for working mothers - Provide information regarding how to prepare foods, provide

health services, and, if needed, supply supplementary foods (e.g., Philippines, SEWA centers,

ICDS centres).

Parent support groups - Information on growth and development as well as health or income

earning.

B.

Develop innovative models for addressing these aspects of child development

India and USA both developed similar programs during the 1960s and 1970s to address the problems

of children in poverty. Both have changed and matured over time; both have been criticized as

ineffective, and both have shown that there are clear evidences of positive impacts at a broad

national level. Both have also recognized the importance of beginning to intervene in the earliest

UNICEF, Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26, 1999

16

' I

F'

L

r

INAUGURAL.

SUB REGIONAL SEMINAB ON INNOVATIONS IN ECCO *

■

years. Comparing the resources used for each can make us aware of how much is done in India by

ICDS with so few resources. For example in ICDS, an AWW and assistant may handle up to 83

children, whereas in the Head Start program in USA, the same pair handles about 15 children.

i

I

The experience of both programs has led to the recognition that it is essential to begin

earlier, and to develop different models for care. Head Start now has an Early Start program

with home visiting and nutritional support. They have also designed specific programs for

children of migrant parents who work in changing areas.

There is no one right way; we need to be aware of the multiple needs of the child for

survival, for growth, and for development, as well as for protection and participation. We

need to take the parents’ investment strategies, and the reality of their lives, into account.

We need to recognize that investing in children is a very cost-effective use of public and

private funds, particularly for children under three years of age. But the cost is high, because

the efforts that parents have been putting into child rearing has never been paid for. As we

move forward, to the next millennium, we will find more families transitioning into the new

model of child rearing, and we must be ready to meet the challenge of addressing their

needs and assisting parents to support children.

UNICEF. Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26. 1999

17

9

W s

r

SUBREGIONA^SEMINARO^INNawnONSINECCIl

NATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

THE YOUNG CHILD IN THE 21st CENTURY IN INDIA : IDEAS FOR TODAY AND TOMORROW

MrSK Mutto, Director, NIPCCD, New Delhi

VISION STATEMENT

Balika Samariddhi Yojana - starting early

•

Ensure child survival

DPEP

•

Facilitate growth of the child

RCH

•

Promote development of the child with the

element of participation

STRATEGIES FOR MAXIMIZATION

•

Home visits, NHED, enhancing capabilities

among caregivers

•

Maternal nutrition and for 0-2 child

•

complementary feeding

•

Hygiene

•

Institutional deliveries/ante natal care

•

Contraception and spacing

•

FLE for adolescent girls; anaemia

•

Creativity in pre school and making schools fun

GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

•

Reduce infant mortality to half of the present

level by 2020

•

Eliminate Grade III and IV malnutrition by 2010

•

Eliminate vaccine preventable disease by 2010

•

Get all children into school by 2020

TODAY’S SITUATION

•

Infant mortality is 71

•

30% babies have low birth weight

•

Most babies are delivered at home, causing

deaths as well as congenital defects

•

Over 50% children are malnourished

•

100 million children are out of school

GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

•

ICDS - a holistic approach to child development

•

IMY and RWDEP - empowering women

UNICEF, Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26, 1999

LOOKING INTO THE FUTURE

Survival will improve; development requires

attention

AIDS is a potential killer of children

Education deserves further attention

Rise in demand for child care services

Support mechanisms for and early detection of

disabilities important

23

i

snuEF^ispBznvE

SUB REGIONAL SEMINAR ON INNOVATIONS IM ECCO

a

STATE PERSPECTIVES

department of social welfare, tamilnadu

Mr. Sakthikanta Das, Secretary

Innovations in ECCD in Tamil Nadu

Started new facilities and new inputs like 1 egg a day for each child

Numerous number of Anganwadi Centres, Health centres, help centres, mid day meal centres exist and

serves as focal point for community mixing and exchanging ideas and needs.

Importance of Education

Need to educate youth to develop both technically and economically

Software a high source of employment for youth

Tamil Nadu at the forefront of technological advancement

Anganwadi centres to help shape and develop children with a view to sending them to Primary school

Child to be given all facilities regardless of gender

Work for 0 percent drop outs.

Importance of ECCD

Early childhood care and development crucial and essential in shaping the future, nature and character

of the child

The family, community, anganwadi centres, etc., needs to have an integrated and comprehensive approach

towards ECCD.

Anganwadi centres not merely feeding centres but plays an integral part in creating awareness on the

importance of development of the child, nutrition, education, health, etc.

They bring other social groups into the programme

Training programmes are regularly held for women and children in rural areas. Attractive reading material

and innovative pictures, etc.

Much importance given to the micro level situation where family is the focal point for improvement in

ECCD

Realising the gaps in the implementation of various programmes, the Govt, of Tamil Nadu has tried to

improve.

DIRECTORATE OF SOCIAL WELFARE, GOVTERNMENT OF KERALA

Ms Ishita Roy, Director

Objectives of ECD

•

•

®

•

•

Recognise that the child’s right to survival, development, protection and participation is universal and with

no discrimination whatsoever,

Ensure that every child is healthy, well nourished and cared for and able to achieve full development

potential and active learning capacity, so as to give the best possible start to life for the young child.

Develop and mainstream community-based approaches to ECD for children under three years of age.

Enhance the capabilities of care-givers

Increase family and community participation

UNICEF, Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26, 1999

25

I J

I I •

1

k

••

’ ‘ -a .S'

- SraTEFERSFBOTVE

SUBREGIONAL. SEMINAFFON INNOVATIONS IN ECCa

Effective training programmes for various levels

Orientation to the community through the resource group consisting of AWW, Teacher, HM, Opinion Leader

Periodical reviews with field staff - CDPOs and PDs

Training

Ongoing training programmes at various levels involving MLTCs, AWTC instructors, Supervisors, AWWs,

RDDs, PDs and CDPOs

Strategies to ensure girls’ education

Improve literacy among adolescent girls, through bridge course

Improve vocational skills through training programmes

Information & Communication

Publication of Newsletter in Telugu for supply to all the AWCs to create awareness of Mothers Committees

as well as brochures on their role and responsibilities

Press tours/exposure visits to various Projects, Anganwadi centres

Organisation of photo exhibition

Production of TV /Ad. Film documentaries on various programmes

UNicef, Chennai & Hyderabad

November 24-26, 1999

29

I

•4

*

STATE PERSPECTIVE ON ICDS, 1999- 2000

Mr. B.3. Kanti, Department of Women and Child, Government of Karnataka

In Karnataka ICDS programme was launched on 2nd Oct

1975 at T Narasipura of Mysore District with 100 centres.

The scheme expanded gradually and has emerged as the

most effective child survival scheme of the state. The

present project and Anganwadi profile is as follows :

Rural

Urban

Tribal

Total

166

166

10

10

9

9

185

185

(100%)

Anganwadi Centres

Sanctioned 35856

Operational 35846

1120

3194

3047

40170

40013

(99.6%)

ICDS Projects:

Sanctioned

Operational

1120

ICDS scheme has spread over in ail the 175 taluks and

10 urban areas of the state. Rest are being covered under

World Bank assistance. Added to this, all the 27districts

are sanctioned with District ICDS Monitoring Ceils

entrusted with reviewing of ICDS programme.

The six package of services under the scheme are being

effectively implemented in the state by the Zilla

Panchayats. The Dept is monitoring and guiding the

implementation of the scheme based on the guidelines

issued by the State Government and the Government of

India from time to time.

Supplementary Nutrition Programme

In Karnataka, supplementary feeding is being carried on

in all the 185 projects in 6 days, a week. Ablend of Energy

Food and locally prepared food out of rice is given on

different days. At present, apart from children below 6

years, pregnant and nursing mothers, adolescent girls in

the age group of 11-18 and Anganwadi workers and

helpers are also enrolled for supplementary feeding. An

average of_24 days of feeding is registered in the state.

The state government is bearing a cost of 52% from the

central government. The state government releases funds

to ZPs_periodically under both feeding and administrative

components.

Preschool activities

Pre school activities in AWCs are made more attractive

and innovative by developing and introducing integrated

approach - a blend of COPPC and thematic Approach.

This new approach which is being practiced in the centres

successfully since 1991 is well accepted by the

beneficiaries. 5.86 lakh boys and 5.71 lakh girls are

attending pre school activities. Special efforts are made

for enrolment of girls.

DSERT in collaboration with the Dept and Unicef has

conducted workshop on the development of ECE curriculum,

activity bank and activity kit. ICDS functionaries like

Sub Regional Seminar on Innovations in ECCD,

Chennai - November 24-26,1999

CDPOs, Supervisors and Aws were actively involved in

the workshop.

District Primary Education Project

It is proposed to strengthen Anganwadi centres providing

pre school equipment in some of the selected districts

under DPEP programme with the coordination of Director,

District Primary Education Project in the state. This project

was started in the yeaM9Q4 - 95. The main purpose of

the scheme is to see that girls who are engaged in looking

after siblings in the houses thus depriving themselves of

school going, are made to attend schools by keeping

AWCs open upto 5 pm; This programme aims at the

increase in the attendance of girls in schools. The AWWs

and AWHs who have to work in the AWCs up to 5 pm will

be paid an additional honorarium of Rs. 300 for AWWs

and Rs. 250 per month under DPEP. An amount of Rs.

2000 one time grant will be released to AWCs for

purchasing pre school equipment and toys. At present,

2405 AWCs in 28 ICDS blocks of 11 districts are covered

under this programme.

Health Services

Immunization and Health check up are being conducted

in the AWCs with the coordination of the Health

Department. JpinlLVisits of medical officers and CDPOs

and middle level functionaries of both departments are

being conducted. Referral services are given to the

severely malnourished children who are suffering from

chronic diseases. Of the total children 20.55 lakh children

are weighed and of this 12.50 (61%) lakh constitute

malnourished children. Stringent action is taken to reduce

the percentage of malnourished children by gearing up

health checkup and referral services.

Two days joint Training course has been organised by

the Dept of Health and FW services to AWWs and lady

junior health assistants during 1996-97 in Kolar and

Chitradurga districts on pilot basis. Jt is proposed to

conduct these training courses in other districts of the

state in phased manner.

Translation of Training materials

The department had developed six types of traininq

materials in Kannada to enable the AW worker to

understand the concept of ICDS programme. This was

done with the assistance of Unicef.

Staff and Training Position of ICDS Functionaries

sanctioned

filled

185

219

183

144

663

38928

CDPO

ACDPO

Supervisor 2036

AWWs

40170

vacant

trained untrained

2

157

124

75

Cj3732)

663

659 27993

25

20

11518

89

Decentralised Training

Anganwadi Workers

Programme

for

The Department of Women and Child Development in

Karnataka has taken up an innovative decentralised and

revised programme of Refresher Training of Anganwadi

workers of 6 days during at the district level with the

financial assistance from UNICEF with a view to clear the

heavy backlog. As a pilot project this programme was

taken up in four districts in Gul ba rga, DK. Bellary and

Shimoga Districts during 1993 - 94. Evaluation of the

pilot project was conducted by the NIPCCD, Bangalore

which indicated the success of the training programme.

Therefore, the Refresher Training was extended to the

remaining districts during 1994 - 95 and continued up to

1996-97. For this purpose, Core Teams at district level

Involving District Assistant Director of Women and Child

Development, CDPO, supervisors, Medical officers, and

instructors of AWTCs were constituted. £5250 Anganwadi

workers have been trained under this programme. Final

concurrent Evaluation of the programme was again

conducted by NIPCCD, Bangalore during 1996 which

indicated success of the programme. Based on the

previous experience it is proposed to continue the training

programme under UDISHA during..2000.

The ATI was specifically entrusted with responsibility of

facilitating training at_district training instituteJDIIs) by

setting up necessary dish antennae, making available TV

sets and STD phone lines and providing space for

conducting training programme. The department of W &

C undertook responsibility for developing software for the

workshops in collaboration with NIPCCD, Bangalore and

other NGOs.

The programme was transmitted from the Earth Station

at Bangalore to all the districts. The training included

issues relating to ICDS such as techniques in pre school

activities, growth monitoring and other new schemes of

the department. In the first phase, the training was

imparted to ADS, CDPOs, ACDPOs, Pos, Supervisors

and principals of AWTCs. The total No^of functionaries

under this training was 718.

In the subsequent phase, under UDISHA, it is proposed

to conduct four satellite tele-workshops each year on the

subject stated below :

—————

1.

Community participation and convergence of

services of ICDS at AWCs.

2.

Impact of Nutrition on Pregnant and Nursing Mothers

and children below 6 years.

3.

Importance of health education to the community

4.

Importance of pre school activities in AWCs.

Satellite-Based Interactive Training Programme

The first innovative satellite based interactive training

programme was organised in the state of Karnataka at

Bangalore during Feb 1995. Based on the previous

experience the Department has organised training

programme for all the district officers and ICDS

functionaries through satellite based interactive Network

in May 1997 in collaboration with ATI, Mysore at ISRO

Bangalore.

The department is coordinating with other departments

for implementing ICDS activities. Theleading NGOs like

Sumangali Sevashram, Sutradhar, Promise Foundation.

Guild of Service, Jindal, Prerana, Sumaha,Lords, Myrada,

etc., have also been involved in the implementation of

ICDS programme in the state.

v . /

EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT

Ms. Ishita Roy, Secretary, Directorate of Social Welfare, Government of Kerala

Early children development is a time of opportunity and

learning. It is a process when the child unfolds behavioural

patterns from immature to mature, which enables the child

to emerge from a dependent entity to an independent adult.

The more a child receives, better his intelligence, his

personality and his growth and development. Therefore

the need for more protection, care, affection, interaction,

stimulation and learning. These are the rights of the child

and not mere concessions.

The efforts, therefore, should lie in advocating a rightsbased strategy which should respond to a vision of children

in the 21” century who are respected, protected and loved.

In order to ensure the best interest of the child it is essential

to guarantee his economic, social, cultural and civil rights.

More importantly every single child ought to be guaranteed

equality of opportunities without any distinction and this

could perhaps come from the creation of a caring

Sub Regional Seminar on innovations in ECCD,

Chennai - November 24-26,1999

i

community, right from the parents to guardians, to care

providers, to neighbours, to peer groups, to policy-makers

and implementors.

We are all aware of the fact that India has been a signatory

to CRC. The ratification of the CRC implies obligation on

the State Governments to respect, protect, facilitate and

fulfil rights as embodied in CRC. It also implies that the

unreached should be reached, specially those belonging

to SCs, STs, those disadvantaged due to socio-economic

and socio-cultural factors, the neglected and all the juvenile

delinquents, etc. It also implies moral obligation on the

family and community to provide care and protection

because many of the violations of child rights take place

within the household, and sometimes with the knowledge

of the community. This is particularly with regard to issues

of protection such as child suicides, child abuse and their

sexual exploitation.

90

Kerala, as the entire nation is aware of, has gone for a

massive decentralisation of democratic authority, where

40% of the State's Plan funds have been given to the

local bodies for implementation at the local level. The

objective is that through local initiative, the effort should

aim at effective delivery of services, increased

accountability and openness and transparency in decision

making. Towards achieving this end, monitoring by

People’s Committees as in the case of Panchayath

committees should be strengthened which act as watch

dogs in Kerala.

While talking of ECD, one might not forget that malnutrition

among young children remains as one of the most difficult

and complex goals. The effort, therefore, should be on

reducing malnourishment by reaching out to children in

the most curcial age group of under three years and

focusing on caring practices in the household, improving

access to health care and a safe environment, reducing

gender discrimination and enhancing the nutritional status

of the adolescent girls.

Recognise that the child's right to survival,

development, protection and participation i»

universal and with no discrimination whatsoever,

Ensure that every child is healthy, well nourished

and cared for and able to achieve full development

potential and active learning capacity, so as to

give the best possible start to life for the young

child.

Develop and mainstream community-based

approaches to ECD for children under three years

of age.

Enhance the capabilities of care-givers

Increase family and community participation

Strengthen ‘joyful learning' in anganwadis

Strengthen linkages between the anganwadi, the

primary school and the health care system

In Kerala, low birth weight among infants is an important

indicator of the risk of malnutrition. It is also emerging as

a major cause of chronic illness later in life, as well as a

factor in mental retardation. Therefore, better care of

adolescent girls and women, especially during pregnancy,

would be vital in improving the nutritional status of both

women and children. These pre-birth factors have to be

addressed to within child development and nutrition

programming of the State.

A child rights framework would, therefore, include a

strong networking between Governments and the civil

society, specially the women, the youth and local Govts.

And enabling and empowering them to identify their

own opportunities and design specific interventions that

are best suited to local realities.

Sub Regional Seminar on Innovations in ECCD,

Chennai - November 24-26,1999

Psycho-Social stimulation and child parent interaction has

a very significant implication for physical and cognitive

development of the child. Neglect of children, specially at

the age less than 3 years, has serious implications in terms

of over all development, readiness for schooling and