NUTRITION

Item

- Title

- NUTRITION

- extracted text

-

RF_NUT_3_SUDHA niv-T s \

ST. JOHN'S MEDICAL COLLEGE, BANGALORE

-

.

COMMUNITY HEALTH

Class

Roll No.

Semester

Subject

Date

Examination

A»'C7"Ri i I ON.

47/1,(First Floor)Su M.i<H< ? ••••

*

BANGALORE «

1

i-l'icxj2_<2‘2,.Q.. .2^, .

(

rruo-ek-el

fX-5-fti.

._rta

c-taJJtsL«vcit3 , <<sVi ^o- cJ

6 v^Clctao-s

«=>-/-> r> <-<c .J? (_^.‘ . .

2o<=»<=/’

a

'

pxAe --9.-<^tatt«=34

/taT ^civ<^o.o£Q

7yJs3^ta<oCZ&^|

7

, i-J-'>

rx-^?A7[ix.Q_.. c^RxaxsL-

S’ovTr><e_

^S^JiciAjQ..

,1-.

<ixn_j~jA_C.O-x’=£ z..

<t< . lZ^~^T.

o. ... ...

0--

S7_<^Ci

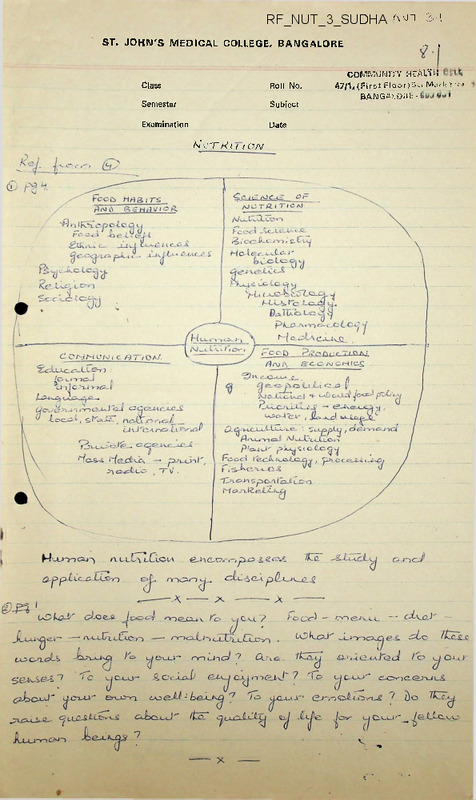

THE DISCIPLINES CONCERNED IJITH NUTRITION

/BIOCHEMISTRY /

/AGRICULTURE /

/PHYSIOLOGY /

/MEDICINE /

/ANIMAL HUSBANDRY /

/NUTRITION /

/ MICROBIOLOGY /

/PUBLIC HEALTH '/

/ECONOMICS /

/ANTHROPOLOGY /

/EDUCATION /

/DEMOGRAPHY /

/ SOCIOLOGY /

ZS „

c- 6

a « £ z

a m c <s

> Z?

*

(Courtesy

o 0

Basic Preventive Medicine by Deodhar Adranwala)w

Co

NO |

3-^-

COMMON,. < .. AL iH CtU

C

47/1, (First. Floor)St. Marks Road

BANGALORE-560 001

,

SO?.T= OBJECTIVES IN THE STUTY OF NUTRITION

At the beginning of any study it is well for the

student to set some specific objectives for himself. These

will not be the same for all individuals because students

begin the study with quite differing backgrounds of

knowledge and experience, and because their professional

interests are likely to vary widely. Moreover, it must be

anticipated that these will, in fact, change as the study

progresses and the student becomes more aware of the field.

Worthwhile goals are not fully achieved within the space

of a few months but should provide the basis for an

ongoing lifetime program of education.

The discussion that

follows will give the student some background for setting up

his own objectives with reference to personal and family

nutrition, and toward a professional career in the health

sciences.

Personal and family nutrition. Regardless of one’s

future professional career, the study of nutrition should first

be directed to onself. Physical and mental health are

essential assets to meet the exciting and sometimes arduous,

requirements of one's life work.

Those who expect to help

other people achieve better health through nutrition must

be enthusiastic and living examples of the benefits of the

application of nutrition knowledge.

Nutrition education applied to the individual also

reaches the family. This is especially important for young

men and women as they establish their own families. Within

the family the wife and mother is the principal decision maker

for the family's food.

She plans the menus, selects the

foods, and prepares them.

Although she makes every effort

to please her husband, her influence also molds many of his

habits.

The food habits of children are formed by the

prevailing attitudes and practices within the home.

Professional opportunities in nutrition.

Professional

people in any discipline related to health are engaged in

activities related to education, prevention, and therapy.

Nutrition education in schools.

Education of the

population holds promise of long-range benefits to the

greatest numbers. Teachers, nurses, nutritionists,

dietitians, home economists, and physicians assume varying

responsibilities for individual and group education.

.. . .2

The elementary and secondary schools afford the single best

opportunity for helping the child to establish attitudes and

practices concerning food selection that will lead him to a

more healthful, productive life.

Nutrition education

must

begin in the kindergarten and continue through the twelfth

grade if it is to achieve maximum effectiveness.

It is

the responsibility of the elementary teacher as well as

teachers of home economics, health, and physical education.

Nutrition programs for the public.

Voluntary and

governmental agencies together with industry are accepting

responsibility for nutrition programs. The researcher in

nutrition and food sciences is equally at home in the labo

ratories of a food company, a university, a hospital, or in

the public health field.

Nutritionists, dietitians, and

home economists, depending upon their education and particular

interests, are the experts who interpret a product for a

company; develop new uses for a food; advise mothers and

children concerning their diets in a clinic; serve- as

consultants to a public health team; supervise food service

in a college dormitory, industrial cafeteria, or hospital;

assist individuals and groups in dietary selection; and teach

in nursing schools, colleges, and universities.

Nutrition and health care.

The concern of today's

health worker is for the maintenance as well as the

restoration of health. Traditionally, health care has

been directed to the patient-that is, the horizontal individual.

Today, health care includes the concept of continuity of care.

The health worker soon learns that there must be concern

for the patient who makes the transition from the hospital

to his home. To implement continuity of care with respect to

nutritional needs, the patient may require counseling in the

proper choice of foods in the market, assistance in planning

for the best use of his food money, and practical suggestions

for food preparation with meaner facilities, or in the face of

physical handicaps.

FPOPLENS AM? REVIEW

1.

2.

What is your understanding of the following terms:

nutrition, malnutrition, foodstuff, nutrient, health, food,

nutritional care, primary prevention?

Industrial and economic developments have been a powerful

factor in the changing of our food habits.

List several

of these which have had an influence on our dietary habits

within your lifetime.

3

Objectives for the student.

To achieve the personal and

professional objectives the student should strive toward the

following behavioral changes.

1.

Shows the proper attitude and convictions relative

to the importance of nutrition in regulating one's own health,

that of the family, and that of individuals of the community.

2.

Knows the kinds of health problems arising from

poor nutrition that exist in his own community, the nation,

and throughout the world.

3.

remonstrates knowledge concerning the science

of nutrition:

a.

Functions, digestion, absorption, and metabolism

of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, minerals, and

vitamins.

b.

c.

The interrelationship of nutrients.

The nutritive requirements of individuals and

the variations that may be imposed by activity,

climate, stage of life cycle, and disease.

4.

Appreciates and understands the meanings that

food has for people and how these are related to economic,

psychologic, and cultural factors.

5.

Interprets the principles of nutrition in the

selection of an adequate diet:

a.

b.

By knowing the food sources of the nutrients.

By applying consumer information to the planning

of meals and the selection of food for quality

and economy.

6.

Uses opportunities for improving nutrition

through the education of individuals.

7.

Counsels people on an individual or group basis

by adapting nutrition information to specific health, socio

economic, and cultural needs.

8.

Knows where to look for reliable sources of

information and how to evaluate publications on food and

nutrition and the claims made through product advertising.

9.

Becomes familiar with agencies concerned with

nutrition and health in order to utilize their services and

contribute to their functioning.

SOURCE: FUNEAMENTALS OF NORMAL NUTRITION

NUTRAL

HISTORY

OF UNDERNBTRITION AND NUTRITIONAL

DEFICIENCY

DISEASE

I Factors influencing undernutrition and

J

nutritional deficiency disease:

'

•

i

i

•

j

j

j

•

AGENT Factors :----------------------------------------- —

Carbohydrates, protein, fat

Fat-soluble vitamins (1,D, and K)

Water-soluble vitamins (thiamin, niacin,

riboflavin,, B,, B

flecin,

pantothenic acid, and ascorbic acid)

Minerals (calcium, phosphorus, sodium,

potassium, chlorine, sulfur, magnesium)

Trace elements (iron, iodine, copper,

cobalt, man.

fluorine)

*

{

j

'j

•

J

j

j

ENVIRON! ■F.1ITAL Factor:

Geographic location (climate, season,

terrain, population density)

Agricultural development

Food processing, storage, distribution,

and preparation

Economic (individual and community)

Social (religion, laws, education,

culture, dietary standards-)

j

[

•

HOST Factors:—-■--------------------------------- —

Habits, customs, mores•

Age, race, sex

|

Nutritional. retirements in various

|

{

|

•

j

|

|

physiologic states (infancy and

early childhood', adolescence,

pregnancy and lactation, old age)

Psychobiologic characteristics

Patholo..ic states (interference with

ingestion, absorption, and utilization:

increased requirements or excretion)

[--------------------------------------------------T"

I

T~

Source of STIMULUS:

interactioru,of factors_______

IRE PATHOGENESIS PERIOD

Natural course of nutritional deficicncy]death

I Defect,

{

J Disability,,

} Chronic

'

state

i

| Illnes s

j short

y------>--------- }or long

jClinically

] manifest

] deficiency

CLINICAL .HCRIZQNJ disease

! Latent deficiency disease:

! evidence apparent,

signs and symptoms indefinite

J and nonspecific

|Potential deficiency disease:

} no clinical evidence^

| low storage of nutrients,

_ } borderline

Unsaturated but

functionally

unimpaired

•Recovery

i-------- ;

|

Saturajti'on:

'

F

]optimal state of j

| • nutrition

'

^"iNTSEACTIOTTSf

“

STIMULU^ and HOST

REACTION OF HOST

PERIOD OF PATHOGENESIS

CO

NVT 3-lf-

r"’=-Vuoooi

47/1,t

<£■

BANG'-^-“

NUTRITION

Nutrition is a dynamic process in which food is consumed and

utilised for growth and repair of the body.

Growth implies increases in physical measures.

Development implies increase of intellectual and emotional

faculties.

Adequate nutrition which is vital for attaining optimum health

This diet

is ensured by providing every individual with a balanced diet.

contains proteins, fats, carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins and water in

proportionate amounts to provide adequate energy for growth and repair of

tissues.

Proteins (derived from the Greek work "protos" meaning to

come first), are complex organic nitrogenous substances containing carbon,

hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sulphur in varying amounts. Some proteins

also contain phosphorus and iron, and occasionally other

elements.

Protein rich foods are milk, meat, fish and eggs from animal sources and

pulses, nuts and beans from vegetable sources.

The recommended daily allowance for the Indian adult is one

gram per kg. of body weight.

This is increased in infancy, adolescence,

pregnancy and lactation..

Lack of protein and vitamin A can cause serious and permanent

defects in children especially.

These range from impaired mental develop

ment and blindness to death.

The reasons for lack of protein in the Indian diet are numerous:

1.

Lack of knowledge of the importance of proteins

2.

Lack of utilisation of locally available proteins

3.

Dietary restrictions

4.

Superstitions and some traditionally harmful customs.

(For example - In some rural areas pregnant women

do not eat green leafy vegetables or drink milk).

5.

Poverty

It was estimated that 10 - 15$ of the people in the world,

or roughly 20$ of the people in the developing countries, did not meet

their energy needs during the decade 1950 - I960, (they were undernourished).

The study was extended to estimate the incidence of protein deficiency as

data became available; this estimate was placed at between 25 and 33$

(Sukhatme 1966)..

What has since become clear is that protein deficiency is for

the most part the indirect, result of inadequate energy intake.

In other

..2

2

words, what diets lack is energy foods to avoid the body katabolizing

(Gopalan 1968).

the protein people do eat.

This finding is the opposite

of what has been reported in various studies of the subject, notably the

study on Protein Gap by the U.N. Committee on Application of Science and

Technology to Development (U.N. 1968) which has formed the basis for

international action.

The finding

that protein deficiency is indirectly caused by

low calorie intake is gradually being confirmed by a number of workers

and is also reflected in the recent writings of F.A.O. (1971).

Based on F.A.O. and W.H.O. Studies (1957 to 1965) and the

recommendation of the I.C.M.R. (1968).

Recommended.

Levels of Nutrient

Intake for the Pre-Social

Child and Adult in India (Approximations only):

% Prot./Cal

Concentration

$ Protein/

Cal Concentration

when NPU relative

to Eggs is 67

Age

Calories

Protein as

Egg in G

*

1-5 years

1,000

12.0

4.8

7.2

Adult Male

2,700

55.0

4.8

7.2

* Defined as average + 20$

Current evidence shows that if a diet has 5$ of its calories from

good quality protein, such as in egg or milk, the individual's needs for

protein will be met regardless of whether he is a pre-school child or an

adult man, provided he eats enough to meet his energy needs.

TABLE

IV

Distribution of households surveyed in India (Maharashtra

State) 1958 by calorie supplies per day per reference man.

CALORIES/per day/per reference man

Upto 1,500

$ Frequency

. 6.8

1,500 - 1,700

9.7

1,700 - 2,100

.14.7

2,100 - 2,500

16.5

2,500 - 2,900

16.6

2,900 - 5,500

12.9

5,500 - 5,700

9.0

5,700 - 4,100

5.5

4,100 - 4,500

5.5

4,500 - and over

5.0

100

by National Sample Survey 862 households.

3

"Since malnutrition (or the lack of a balanced diet) is the

outcome of several factors - social, economic, cultural and psychological

the problem can be solved only by taking action simultaneously at various

levels - individual'family, community, national and international levels.

Other measures to ensure people adequate nutrition are:

1)

Increasing food production

2)

Price control

3)

Prevention of food adulteration

4)

Fortification and enrichment of foods

5.)

Food aditives .

6)

Inventing cheap supplementary foods (e.g. High Protein Foods)

7)

Irradiated Food

8)

Nutrition education, and

9)

Population control

The Government of India is attempting to solve the problem of

malnutrition by implementing the following programmes on a national scale:-

Cro'iVc

1)

Applied Nutrition■Programme

2)

3)

School, Mid-day Meal Programme

National Government Control Programme

4)

Crash Programmes in Nutrition (For 0-3 years)

5)

Vitamin A supplement to facilitate growth and prevent

blindness.

Studies from the United States- and the developing countries

reveal the not surprising fact that as family size increases,

spending for food goes down.

per capita

As a result, corresponding diet inadequacies

and nutritional deficits are common.

FOOD CONSUMPTION PATTERNS BY STUDIES OF F.A.O.

Major Parts of India

Rice, Millets and other Cereals

Moderately High

Pulses, Fats and Oils

Moderate

Milk

Low.

Meat, Fish and Eggs

Very Low

India (Punjab) and Pakistan

Wheat, Rice

High

Milk and Pulses

Moderate ’

Meat, Fish and Eggs

Low

Cereals constitute upto 80$ Calorie Supplies

and upto 70$ Protein Supplies

Pulses constitute upto 10$ Calorie Supplies

and upto 20$ Protein Supplies

Food of Animal Origin constitute upto 4$ Calorie Supplies

Meat, Fish and Milk - 10$ Proteins

4

Malnutrition, especially, protein calorie malnutrition, is

widespread and is to be' feared not only because of its general debilitating

effect but especially because of the irreversible brain damage that

inadequate proteins cause.

Data from 24 countries indicate that the

prevalence of severe PCM (Protein Calorie Malnutrition) ranges from

0.5% to 5% and the prevalence of moderate PCM from 4% to 43%"The human brain reaches 90% of its normal structural develop

ment in the first four years of life.

We now know that during the

critical period of growth, the brain is highly vulnerable to nutritional

deficiences, deficiencies that can cause as much as 25% impairment of

normal mental ability.

Even a deterioration of 10% in the diet is

sufficient to cause a serious handicap to productive life.'.

irreversible brain damage.

This is

What is particularly tragic in all of this is,

that when such mentally deprived children reach adulthood, they are

likely to repeat the whole depressing sequence in their own families.

They perpetuate mental deficiency, not through genetic inheritance, but

simply because as parents they are ill-equipped mentally to understand

and hence to avoid the very nu ritional deprivation in their own children

that they themselves suffered.

In low income countries the high mortality rates among children

in large families and in families with close birth intervals, are in

part due to malnutrition.

The greater the sibling number, the greater

the likelihood of malnutrition among poor families.

Studies of pre

school children in Colombia, for example show that 52% of the children

in families in which there were five or more pre-school children were

seriously malnourished, whereas only 34% of children in families with

only one pre-school child were malnourished»

In Thailand, of the children whose next youngest sibling was

born within 24 months 70% were malnourished; of those in .families

without a younger sibling, only 37%.

Height and weight being affected directly by nutrition showed

variation in children according to family size. Even in high income

countries the children of the poorer families are larger at any given

age when the number of children in the family is small.

For example,

of 2,169 London day-school students, 11.25' years old, children from

one child families were about 3% taller and 17 - 18% heavier than children

from families with five or more children.

The difference in physical growth between children of small

and large families in Great Britain seems to affect mainly the poorer

social classes.

In the higher income classes boys in families with

5 or more children are taller at all ages than boys in small families;

the reverse is true for girls.

In the upper and lower manual working

..5

5

classes children in small families average 3-4% taller than those in large

families at 7 and 11 years of age and 114 to 2.8$ taller at 15 years.

Diet surveys carried out in India have shown that the average

Indian diet is ill-balanced with an excess of Carbohydrates and very little

protective foods like milk, meat, fish, eggs, fruit and leafy vegetables.

The Nutrition Advisory Committee has designed a diet from the

resources available required to give a total caloric value of 2,400.

Such a diet would cost, in I960 Rs.35 per month per adult.

Only 20$ of

our people in India can afford this.

Indian rural economy is not balanced, for while rural earnings

give only Rs.16 per individual per month, the same individual spends

Rs.20 in that month.

Only 70 crores of the total outlay of 361 crores of rupees is

provided for rural hospitals and health care in our 4th Five Year Plan.

The .top priorities of the health tasks are not always properly chosen.

The Green Revolution in India has lulled many into a state of

complacency.

While it is true that great progress has been made in

increasing food production, the increasing population h’s almost nullified

this increase, so that the per capita availability of food is only 446 gms.

(cereals and pulses) per day and a per capita availability of 120 ml. of

milk per day.

Yet India has the largest cattle population in the world -

most of the cattle being of poor quality, yielding little milk and serving

no useful purpose, yet consuming much fodder.

The economic advantages

would be considerable if these animals were permitted to be slaughtered

and much needed meat be made available for consumption and more leather

for foreign trade.

About 1/3 of the people have no objection to eating

beef.

Whereas the proportion of staple cereals and starchy roots in

,the North American diet is estimated to be only 25%, and in the British

diet only 31%, in Latin America it is 54%, in Africa 66%, in the Near

East 71% and in the Far East over 73%.

Conversely, while the proportion

of animals products - milk, meat, eggs and fish - in the typical North

American diet reaches the exceptionally high figure of 40% and in the

British diet can be as high as 27%, the figure for Europe as a whole is

estimated as 21%, for Latin America 17%, for Africa 11%, for the Near East

9% and for the Far East 5%.

In only a few regions of the world are there adequate food

supplies.

These are the United States and Canada,'Australia, New Zealand,

Western Europe, parts of Argentina and parts of South East Asia,

regions have already utilized the means of increasing agricultural

...... 6

These

6

productivity, but only ten centuries in the world today produc i more food

than they consume.

The "dhals" which have a high protein content (vegetarian meat!)

take the place of animals foods in communities where it is consumed

(though in insufficient amounts).

IIowever, the body utilises only 40 - 60%

of the vegetable protein which forms the chief kind of protein (in contrast

to animal protein) that is consumed.

Certain essential amino acids like

Lysine and Methionine are also present in insufficient amounts in this

diet pulses.

According to a National Survev the average daily intake of

calories in India was 1890 calories with a daily protein intake of 53 grams.

Pregnant women, nursing mothers and growing children, ie. ;a

group constituting 60% of the population

*

proteins, vitamins and minerals.

lack adequate calories,

The result of this is seen in the high

incidence of low birth weight babies, still-births and fairly high

morbidity and mortality rates in children.

Health education for adequate nutrition

and balanced diet

needs to be given to all parents, teachers and health personnel.. Many

foods are freely available at reasonable prices and can be used to. supplement

the diet.

These (greens and fruits especially) are often locally

available or easily grown in the kitchen gardens, and found both in cities

or in rural areas.

The C.F.T.R.I. has also developed multipurpose food - which is

a blended flour of groundnuts and Bengal gram.

It is cheap, extremely

nutritious and can be used in a varietv o'7 ways. For children especially,

C.F.T.R.I. has a prepared mixture of wheat, groundnuts, and soya bean or

Bengal gram flour with skimmed milk powder.

More recently, using a machine, C.F.T.R.I. has extracted protein

from leaves and grass.

This process is still in the research stage.

It is interesting to note the view of Dr. P.V. Sukhatme "An insufficient amount of protein in the diet is held to be at the heart

of the problem of persistent and widespread malnutrition in the developing

countries.

However, when one examines the available data, the conclusion

is clear that what diets lack is not protein but energy foods to enable

the body to utilize the protein people actually do eat.

There is no

evidence that the quality and concentration of protein in cereal-legume diets

normally eaten in the developing countries is inadequate to meet protein

needs, provided energy intake is adequate.

essentially a socio-economic problem.

The protein problem is therefore

Production of semi-conventional,

,

cheap,- protein-rich foods using modern technology and distribution of

factory foods so produced through special feeding programmes as recommended

...7

7

by

the international bodies, will be a costly and inefficient method of

solving the problem".

Much can be continued to be said on the subject of nutrition, but

at the present time given the familiar family situation of providing

adequate nutrition two things must be emphasised:

1.

The use of locally available foods like green leafy

vegetables in the diet.

2.

Early recognition of nu ritional deficiencies and their

remedy by sound-dietary practices and use of food

supplements prepared by C.F.T.R.I.

A recent report says "Nearly one million Indian toddlers die

every year because they do not get enough to eat. Although these hapless

toddlers constitute 16.5$ of the population, they account for 40$ of

the total deaths.

One-fifth of the babies born in India never live

beyond the age of five years".

In a paper on Nutrition and Development, Gopalan points out that

apart from the one million small children

who annually fall victim to

malnutrition, many more die of diseases they would have either escaped

or survived if they had been better nourished.

The children would stand

a better chance if they were more sensibly fed from even the available

foodstuffs.

In a countrywide survey, the severely undernourished pre-school

children (17 - 18$

of the number surveyed) were 40$ lighter in weight than

they should be for their age.

About 14$ were 10 - 25$ lighter than normal

and 65$ were 26 - 40$ lighter than they should be.

Only 5$ were the

right weight for their age.

The question of wants also means that the use of resources may

go far beyond what someone from another social background might consider

quite adequate for survival or even for a good life.

It has been

calculated, for instance, that a child born in the United States is likely

to consume in the course of a lifetime 28 times as much as a child in

India.

TABLE

Estimated consumption per head in I960 in various countries

(U.K. = 100)

U.S.A.

Sweden

West Germany

Mexico

Taiwan

Ceylon

India

140

125

86

22

12

9

5

...8

8

Since nutrition is closely bound up with Agriculture, it is imperative

that the problem of malnutrition which is so serious in India be confronted

at "grass-roots" level. Three possible avenues are open:

1.

The growing of food crops to be encouraged, expanded and

2.

The storage, distribution and allotment of food to priority

given positive incentives.

groups (e.g. the vulnerable population) given due attention.

3.

Increased research and exploration of food from a) the sea and

use

b) of the protein containing vegetable foods like

groundnuts and soya bean.

The exact fishing potential of the ocean remains unknown. Indeed

fish farming as a serious, industry is still in its infancy in most parts of

the world.

The Northern Hemisphere is 61% water and provides 98% of the

world's fish supplies.

The Southern Hemisphere is 81% water but is supplies

only 2% of the fish.

The fisheries of the world could yield far more food -

and of a particularly valuable type - being of good protein content.

It is of importance and.interest to look to future trends in food

cultivation for both the rich and the poor countries.

The rich countries, with no greater rate of growth.in food production

but most of it coming from increases in productivity and with only half

the rate of growth in population compared to the developing countries,

improved their pei~ caput availability of food and were able to export

increasing quantities.

As a consequence, trends in the food supplies of the developing

countries have been somewhat more favourable than those in production

but this has taken place at the expense of the trading pattern between

the two groups of countries.

The Far East and Near East, which were

exporters of food before the War, are now importing 6 and 7% respectively

of their supplies.

Africa and Latin America are still exporting but on

a much reduced scale.

This unfavourable development has tended

to increase balance of payment problems and to accentuate the difficulties

resulting from the almost continuous decline since the Korean boom in.

world prices of primary commodities.

The situation is illustrated.by the

example of cereals; the less developed countries (excluding Mainland China)

which exported ten million tons of cereals before the War are now actually

importing nearly 20 million tons, and this largely to maintain their

current unsatisfactory level of diet.

Judged by these trends, the prospects

of stepping up the rates of growth to 3% in total foods and 3.5% in animal

foods over the years 1965 - 2000 seem bleak indeed.

Sine

we cannot take comfort from the past trends, we should

find out what are the possible sources of food supnly, what resources we

9

have and how we can exploit them to meet our future food needs. Never before

the planning of resources use and land use in particular has assumed so much

importance as at present under the heavy pressure of demographic growth.

TABLE

Rate of Growth (1958-63)

Population

Growth

Per Capita Gross

Domestic Product

(per cent per year compound)

Developed Regions

Developing Regions

2.5

Gross National Product is the value of total annual production of

goods and services supplied by all 'normally resident' individuals,

firms and government bodies.

If 'income' is restricted to income

derived from participation in production GNP also equals the annual

sum of their incomes, including net incomes from abroad.

Gross Domestic Product

Equals GNP minus net income from abroad.

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

47/1,(First Floor)St. Marks Hoad

' BANGAlOae-560 001

FOOTNOTES TO THS TABLE ON DAILY ALLOWANCES OF NUTRIENTS FOR INDIANS

-f-ColA w

1. Calorie s;

-A MrnYiclf

a)

Calorie allowance for heavy work does not include work under

special conditions like high altitude.

2.

Proteins:

a)

Adult allowance corresponds to 1 gm./kg. of dietary protein

of N.P.U. 65.

b)

Infant allowance during 0-6 months is in terms of milk proteins.

During 7-12 months,part of nrotein intake wil1 be protein in

the formof milk, and supplementary feeding will be derived

from vegetable oroteins.*

' Total daily protein allowance is

calculated from the ideal weight. Protein allowances during

infancy will be:-

0-3 months

3-6 months

6-a months

0-12 months

2-3gm-/:g.

1.2gm./kg.

1.3,gm./kg.

1.5gm./kg.

.

.

■

Allowances for children and alolescents have been computed using

body-weights as obtained in the well-nourished group and

ass'Uning N.P.U. of 50for the dietary proteins.

c)

• Calcium: In the absence of precise information on calcium

requirement of different groups, a range of allowance

has been suggested.

a) Calcium allowance for infants 0-6 months will be for artificially

fed infants. Calcium intake from breast milk will, however,

satisfy the needs of breast-fed infants up to 6 months.

• Iron:

a) This allowance of '30mg. iron is for adult woman during, her

premenopausal period. For the post-menopausal qoman,iron

allowance is the same as for man.

b)

c)

This allowance for preganat woman will be throughout pregnancy.

This allowance is for lactating woman who is not menstruating.

If a woman is lactating and also menstruating, her iron

allowance will be 35 mg./day.

Dietary allowance for Vitamin A is given in terms of retinol

('Vitamin A alcohol) and B-carotene. Either of these is used,

dependin- mon the dietary .source of vitamin. The factor to

be -ised to convert B-carotene to retinol is:

1 ng. of B-carotene

=

0 25 ug. of retinol.

If the diet conta ns both Vitamin A and B-carq.tenes, its-'

content can be expressed as retinol, using the following

formulae.

i)

Retinol content ug. = ug. retinol + ug. B-carotene ^>0.25

if the retinol and B-carotene content of foods are given as

ug. in the food composition tables.

ii) Retinol content, (ug.) = Vitamin A (I.U.) x 0.3 + B-carotene ■

_(I.TJ.) x 0.15 if the Vitamin A and carotene values are given

in terms of International Units.

6,7,3. -Thiamine, Riboflavin and Nicotinic acid;

The daily allowance of these three vitamins are related to

calorie intake.

The basic allowances per 1000 calories are.

Thiamine = 0.5 mg., Riboflavin = 0.55 mg., abd Niacin. = .6.6..mg.

niacin equivalents..

Niacin allowance includes contribution from dietar}’' tryptophan,

60 mg. tryptophan being equal to 1 mg. niacin.

Niacin equivalents in a diet are computed as follows:

Niacin equivalents (mg.) - Niacin content (mg.)

tryptophan content fmg.)

+

"

"6'0 ”

q- Folic Acid:

Dietary allowance of folic acid wil' be in terms of

free folic acid(L. casei activity) present in foods.

a) Folic acid requirements appears to be considerably increased

.durins: pregnancy.

Since the exact requirement is not known,

a range, rather than a single figure, has been suggested for the

daily allowance,of folic acid during pregnancy.

10. Vitamin Bt_q

.

Vitamin B12 is derived entirely from foods-of animal origin.

11. Vitamin D :

Since the exact requirement of Vitamin D is not known, an

arbitrary allowance of 200 I.U./day is made.. This

allowance is in addition to some amount of Vitamin D that

might be derived form exposure to sunlight.

12. Fat:

Since human requirement of fat is not known. no specific

allowance is recommended.

A desirable range for f at in

■ the diet is, however, indicated. Diet should contain at

least 15 gm. fat derived from '..vegetable oils like .sesame,

safflower or groundnut. Itis also desirable that calories

derived from fat in the daily diet sho”ld not exceed 30% of

total calories.

Daily Allowances of Nutrients for Indians

(Recommended b-r tHe Nutrition Exnert group in 1968)

i

Man

Woman

5

9

10

50

100

1

13

15

20

50

100

+2

50 150-300a7

4*

55a

0.4-0.5

20

750

3000

16

19

26

45 a

0.4-0.5

30a 750

3000

Pregnancy

'second half of

pregnancy)

40b 750

3000

lactation '’into

1 year)

30C1150

4600

tfadontary work

Moderate work

Heavy work .

2400

2800 '

3900

fcedentary work

Moderate work

iteavy work

1900

2200

3000

6

8'

3

7

•

/Z)^

■J A<rxZz>

cU'OtfO

'

2cro

I

—

3

4.

&

"7.

l<b

1

11

&

Infants

0-6 months

12.0/ 'g

1 wOmg./kg

2.3-1.3A<?.a

400

1200

300

1200

—

—

• 250

1000

0.6

0.7

3 “

300

400

600

1200

1600

2400

0.3

0.9

ICO

0.3

0.0

1.2

10

17

14

1.8-1.5/kg

’0.5-0.6

1200

17

12

20

0.4-0.5

. 1500

1300

2100

22

33

41

Adole sc- 13-15yrs.boys

girls

. ents

2500

2200

55

50

0.6-0.7

25 .

35

750

3000

1.3

1.1

1.4

1.2

16-15 yrs.boys

girls

3000

2200

. - — 60 ■

50

0.5-0.6

25

35-

’50

3000

1.5

1.1

1.7 . 21

1.2 14__

7-13

Children

"

1 year

2 years .

3years

4-6 years

7-9years

10-^.2 years

100Ag.■

.15-20

32>

^5

02.

30

25

0.2

14 50-50 50-100 ©.5-

2Z.c^=>

COMMON, i ’/ ... .-.uVH C LI

47/1,(First Floor )-A. Marks Road

BANGALORE-560 001

ASSESSMENT OF GROWTH AND NUTRITIONAL STATUS FT INFANCY AND CWLDHOOD

Pattern of growth

In the normal, adequately nourished child, rapid growth takes

place during the first year of life.

In different parts of India

the average birth weight is about 2,700 to 2,900g. Almost all

babies lose weight during..the first 3 to 4 days after birth and

regain- it by 7 to 10: days. After that, the. weight increases, by 25

to 30g a day for the .first 3 months, and thereafter less rapidly

(see table below).

The widely accepted formula that a baby doubles

its birth weight at 5 months and trebles it at I year does not

apply to all babies, and may be misleading. Babies with a lower

birth ’weight may' double their weight at 3 to 4 months and may be

four times their birth weight at 1 year of age. For example, a

baby with a birth weight of 2, 300g may double that at 3 months

and may weigh between 9 and 10kg at one year.

It is better to be

familiar with the weight gain pattern as shown in the table.

The length of a baby at birth is 43 to 50 cm and at 1 year of

age becomes one and a half times as great.

Thereafter it increases

as shown in the table below. The values in the table ape averages and

each child will differ gfrom another to a certain extent,- but as long

as the trend of the growth curve is maintained there is no cause for

concern.

Average weight and height increments during the first five' years

1-2 years

3-5 years

Weight increments per wee's

200g

150g

100g

5b-75g

ne? year

"2.5kg

3.0kg

Age

1st year

2nd year

3rd year

4th year

5th year

Length increments per year

25cm

12crj

9cp

7cn

6cm

Age

0-3 months

4-6 months

7-9 months

9-12 months

Several' Indian studies have' shown that the weight curves of many

children are excellent for the first 3 to 4 mcnths, with the birth

weight doubling by this age, but after this tpe curves tend to flatten.

This is because no, or insufficient, food is given to supplement

the mother's breast milk, which by itself is inadequate forthe baby

from about this age.

Assessment of malnutrition

It has to be remembered that a series oi readings is more

important than a single reading. Any weight ta :en has to be compared

with some reference standard, and by common consent the Harvard

growth c ’rves are used as reference standards. The concept of

centiles sho'Ld be understood before growth can be evaluated and

compared with a reference standard.

It is easier to -nderstand in

relation to height.

£

If 100 children of the same age are lined up from the tallest to

the shortest, the 50th wilt be in the middle and will represent the

median or 50th percentile.

The. tenth from the left will represent

the 10th percentile (90 children wil' be .taller than him) and the

90th from the left, the 90th percentile (only 10 children will be

taller than him). The lower the percentile, the more growth

retardation there is likely to be.

The same criteria can be applied to weight, and this, too, can

be represented as percentile curves. . It is preferable that the

reference standard for comparison should be from the same population

care, being taken to ensure that these children do not suffer from

nutritional constraints or suffer from infections. This, at the

present time, can only be found in the higher socio-economic gpoup

children. Work is already being done on this in different parts of

India and till such time as these norms are available and there is

agreement on y eir use, it is better to use an accepted standard

like the Harvard standard.

• •

Measurement of Growth - Parameters used

1.

Weight:

2.

Height:

3.

Mid-arm circumference:’ An easy and usef-I measurement.

The

middle of the upper arm. is measured while it is hanging relaxed

at the side of the body.

Normally, the arm circumference

increases rapidly from birth to 1 year. Between the 1st and

5th birthdavs, .it rema! ~s fairly constant in well nourished

children and can be used as an age independent method.

4.

Sad and chest measurements: At birth, the head circ nference'is

’ about 2 cm more than the chest circ inference, about 6-9 months

the two meas rements become eq al, after which the chest

circumference be dome's more than the head circumference. The

chest and head ratio is a (good indication of the nutrition of

the child.

5.

Skin folds: .Where skin fold calipers are available, measurement

of .skin .fold thickness is a useful measure of nutritional

status. The common "sites for skin fold measurement’are triceps,

biceps, subscapular, and suprailiac-regions.

GENER Al PR AC.TT bjjlER.S, COjRSE

PSS/ln 11 .

■

,

VlTfll'Ill'l Q

n i ->

jE“ Tr&oJ'rri er)!’’, dcrr-i^f-ol

CUs-td-

Pr&Y'G-.tnI'ferr')

fl. C&^j tA^efov’&J

oP

I,

fWT 3--f-

VEPlCJEl'jC.y

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL

„

47/1,(First F!oor)St. Marks Road

Xe.KoPHTHfiL.Pllf)

baNc.^ore-wouvI

lfS.&iGr>&,

!$>■

2.. Pre-fe

*~>K'crr->

Cjem)&e>l . —

Ofc>j e.c#yg

*

s

ly.CtmK'ol ,le>kr>ch'»C.6

*

it) improve

'p-r-csTa-rtxr^me.

P- Ps-rfocii o Peio5<S

i)

c^ieA. ZcKe^>5^5>7 .

//) JZ^, P^scJ^oa)

c^nci

.

&>hex&)

B. LL.9t^ oP PocoJly e^reutlpd>/<£

G + P&tKPi ce^Pc~x-> c>P Pao^-S

D.

v^: ce-s.

£. . IPzrffe^/Kiv'&J

u^n'P>

Pcrods.

Vt i^rvtur) Pc^cK'yi Aex>

-r-^lex/’e^-

P . £l<sL<-<.cea/rW>-7csy Z^<s^r<=wvt.<-»7e .

3» rdfi-nohltfL-

It

~c^^a>

JZ^be&u

cwoel

CAAe-rg.

I.

2.

WHO 7Xs

PartGs

3

it.

e

C.

7

9.

o

"

v^i zit

Rm. 7. C-! Cr->

T.6! (J)

)lc>~5

)^7&

"

i&ffi

Oe-H >975

n

2$(JZ)

£?e^/975

h

S.3(I)U^.

^7o

Ao^»ceJ' i , 79^7

//^o-X

McKyHlC

^c^cer

Ip.

II.

12.

^tuK^'her^-i cxxyci

2^-^J

Vai 7o yo/gr4-23©

/ci7’3>.

T-T^p MtA -r lh<>

7& : z^'//5 IH75.

3>t'K T~

27. 2?7-5«4 /97<

7^<aL<^

^ .' 3«>Z-3/e 7972,

7^cp.

rte<A n, 3-7)^ J5 (HUtl)

i3.

fit. V H f) I

HiAl^tl^^na.1 Bl't^-3 ct«e»o o^-yd. Y»7euyi^ 7R .

3chem& —P-ropK^C^t ba C-pjOiXn &}' ^It^cLr-i^ry

by

16.

VtF R /7e^t

c>Mtr»cy

*

z /-axrjily P/cM7rn»» jF^e»yvrw

iz>oee.

*

JB-«^7>e "W P!^-o

'M.F tr?pbvmal'Ryi, MCH tla-Z

SlRGib MPSSiv-R.

7r?<f?

a/

* a/

i^>^^>eb'c\(A)

pde^ eJze^ek. t*->&-S

fke-P'fr9>r inshKu^e. Pb

@

oJoK^cxIly

IniKc^fe- Pse-ld KroJs <&■> PA& kiS<£. &P

dot>££ <as <=<. possible- rnethodlb.-eoAY^oni^<e^Jblondioe-SS> .ie+jmlKnej...fyarrrty&.-A.ue^-t oe £.■?-> c y.

ft) S uami/-?a/Lr> ef ej (l^7c>)

Pootj e

-r crop erf (/7>€zptf-A©©/

cA//<sfv’fi^r? ^//

z?

*

•J-lden.ltSr mlSc-thlCi)

.&.frcrr->

*crCl~Soli^ble^_p>&ptx

€) yj'nOeLin/ P&dely

—p

^ejOTje/^zr, c/ K»9.

de.vslapeeL (Pyp-cj^^jrnCYKXrt^

^t>

”

(jej'l>)

Y<r P daC^ r>oPpfyord^cje. o-<iy

Single- ma.^siYC dose^ianiPfcexd' lySOSoma.1 injury

*

iz.yocKc^ c^f e-rTZ-'.-j /vt&so noK 't-^c-yce^ed

^) £>-t

G Q

/

LJcA/er' d.iSpe-'-isjed o^>d oil So)<-ibl£ prepr” &>

- 3&sf'

c. sPo-re^g. &P v'iP.

Vt'P> p! oy-Y'&^-t O-r-aJly .

&) ^a'kr:A^K<K $■ G ■ ? 7 7o

of

~“ S&rixrr;

m!

ZcrTS-iS

od^erYC- p^e-doc. Is\cl&

e>cct^uced

7

Y-e\^s

erredly o.^d JM.

cjiPlj&^7

esil Soluble,

fnokloienAYK^Ked. e.htld>^r> e Vif" P 5ej» >

**

u

7«CTOyl<y. oFml SeJ^blit. k?ZZ? cnr».^y.

c^eLe- ey^ict

t-~crr"

FH

rneonlPo

,

!&ds

O-^d- Cue-^ sKl!

J) r&rKS-i'^.^.n

A

sj^o’o.

ft erredly cxS tfx. OLrj^lG- eAoSG-— t-e,r&!^' oP Ar,cjcm V/Fti

prC-Kc(?<Pr^^k

2s

ohi/drer') bjho

Goooo/^^ cP VPP p^/m'tPbAc, (few/ <^<srp-<ej)

Zfexc^ eAo^e of /A/2.

>e/feny/ ete&J&Afe .

<S‘S'<% °f d&z>^z ob>&on.b>e.eA. ecn&l

of &/&&& ■>=•«e»dl .

g>, S^r^czTg^g^ M>tprk>.)

P>&t<A SKiA.y

—JPo/olence. of X*®oe><5/S

<xz-?et S/fate

^iCrftpi'C-arAfly T-ectxxeetfi Un’/^u? Z^r^dx-.

dr

coe.r&.

^)

t^p&cK^^A. Locidsrit.

oLt>ir07^

P>

*?

<6

f^jCS forcesek .

0°!^) ^-> ^ub~So.r^p>/G

Sormurry )PPP AsJv’e/S hitjh Par

Pe^tdneA

«X7<51 /A-?ZZ by C^bfen^P 7S^

rfo n^M Ca^^9 of ^Sr>oiKr>^cJa\.cte^

rrterm/l^o

op f'f&ick sfa<Ay chAd'^f

bisf Pep! Ab &/tohACy eJx

£*

oP YiAbmCr^ P Ai> b& efiv'^rj

earjC-G,

(jj -ho-)

TREfJTf^EtiT

J&c-hjr>ieyiA.e- fG-

_ The,

ex. cJ^i'Icl. tS k>e>&p^<^h'‘&a<A. h//#>

u^ue^s-----

xencpInP-’O.lmib. 7h.e. fe>He>L^<>>Cj

p J^-»pY'e>.

■Sy.hI «ar- / / €>Q CsG'li IU\

Pbn cevr»h<^> Ct.K^> /Ofc^l i/ eropvro X. 4?

R&cCYmm') W&feY rtl'Scifol^

Pre~p& Y'eK.K'CYf^

//) C>>!

T^e-eJ^te^k &cheeLu.!c_

—““cAjCcJ^ly crr-> Tjie^pnosis

SC-c-crrtcA. (A<xy

*

/^tor

/» di&cAav’^g. LLneL^-y !/

*>

Ove-s

I

ZZ>./4Jft^r rntSCib/e j It^l

loCfOfDO IU /ail ^ol^tfcmJ.aY'A /

/ac^^° t L>/aii sd^t’r’enn j&

* ■?

^.esrp^oo )

I-yr-

i ,

,

/4>C

OP^>

*

J

tt

/a^aJ>

E^piancJPnr'y VTo/e-S.*

a^~>

2.. l^-perrs

f

.O C>luK&y'> e>P

cmly iP a-tn lM pYepe^o Pe>-y

Gf'l^J&rbtC QreaS

ke^p

io

R. (jtRfBOo lip) sA«tm/«1 4>&-

r>&P

. Lknpi>od tb

nritSctblc pyep&vexPPemo

he^cLy-^P-t'oJf

3. Oral Co-Et/i&K

pre^araKtrrS

a>P V^Ltq*

>?. ?9 »7C.y be

C^k>chtLT&g-X F&r ertl SdM/Tbn® . V,^ P. oCAfo.fi rmo-y A?e.

pla.ce. df -xt/cx? y/ poJrndG'-te.

Q- Oil Coin lions

YtK P- shcrulei-

never foe. ir->jC.cJk A. trf because >^£y

aye. -reloK^rel y tr> elective., lh<2- ri.tcf.mon

^Icro^ly, i£ af cJI, P-rcrm 4A e t^o'jec-Kcsm ^,/f&. .

O bj&c/i^

—'

w «ed

0 "Zp hcjr~ dckf^e. /esi‘en->s.

it) To -r&-p'se.r->> ^>h>

he><Ay ^Tcry^c,.

Ufo-^JiaJ’&ek. Cx^onr^

or csrriiz&i'a^

Vit' P ftiSAopy uiiotle

KcoXrrx^ok' e/ PC-tyi —

Xe^oph&tdrrito.

rrta.y

be- preoipite^feek

Other Pa.c.Kfrs J& b& c.tm^i

I. 7r^eo/r>^er>/^shcruld r^oT b&. e>le.t&ye<£ . rOeltxy P&~ &r<£.r-> c^e. nLexy

aTs)i.^fes <X2. oryr^p

cbe^neyioo o.re >e re-a-o> b!e rrtoy nnoke all lhe

CpUPPe^orje^.

beK^e-O-ra ^r^ht’ <ajoeH bflir}ej.ruz--or> .

ri.. £i^re cc^ndLlt^moe PoJkr^^ To trie^opcmtA. Io a-nlibt'o/it-o—undiejilyiny jeettopthalm70. sAeru/eZ be. Cori^ibLtrteefi e-op\

SoPioJ Circ.Lf.mstoy) cgra Coe. LrtcliccJ^e.

miscible prepr^ rxre especially CrnpcsrtcLriT in Ctxrjeo cf V'crmiK^

It- UneUstlyCriq Ccmdbi^cms need riGCtrcn^9

, P£rfr bluK^lf Or>Al d/SoJeA^

rrle^t i rlakvirai^ -!^f)ba./Mc£, ir>Fe.c.Kcm S. Cnpes/gitrems .

CdNTiZOL.

Pr./£v'£K7'ioiS

C-ot^TRo L.

Pf&aFZMrtgs

(rfHo)

- C-e>ul.dL. J^<si^s__ K-k^o^ .rnouLn^ cshyszcK'’<e s

cL^p&r-icLi^->Ci csv-3 S.ezc»M‘J^ aP pf-rcJoicm. Sm'o eecnamc 5i/tia^d

e*-v r<zslc

*.biitPy

&f husno<si cuoe\ per>c^oc-cctl^ ve^>cu'fce^/ ?fec-^no/ensp\c<

*l

Obiecfi ^c P - fe> c-erryLvol blt<->

ccx-t-cogj/y ye /expect

’/V""#,.

d

]ma

flw

o^r-> cL Lik'e-^ (< 5>

?

*

)

73 icnprcsr^

Afeed c rtKc n o ten'll

Ohj^cKv^. S2 -

..

rcicr>-&-

■pv^-v'es.lG-dK C'f'f-) fc.c\!

iii) p!0^3 mo. o-r^ck

faVe-v-

e.en-3

v'i^xmC-o. £ •SfaKm

of- /c^c> 0.1'"

h e. i) P>c-c^^e^>c.y cf >^e Kv>ilcL

>•) (zLt'iS-i'cxry ccjLe^./^

.

•£> ,

&£>£>£. PRo&filf)riME&

P£Kie>P/c.

Xr-?

2^00, aoa

lU

P (jg

oP

•

e7g?,.<7

rz-rrst fsv'dx.mrrs <£.^

££■■)

£>

**

SvCAy

.c/?z7et<«2^r7

<» rx»finr>>^>«k

— ^-rcs^A^h A<g«si//A

PsFf-

))

.

<S

&y

k&.v’ <sks> perwib}^

^y^Zfe»<>7

^cL^CeJ"!«-»">

rdoJ'ively

£.h^e\p.

-c^

*

Pe

FbRT) r/C^T'lO/'f

Y'&h/cle. /^v-

^hcruld. htex'rC. PoUcusCo^ cJ^&^ye^l^rcLoK co ■.

/. Z^^sessst.

/too > vC-o^o,/^ Ccr>v9u/»

*<s^

tx-rf

KA P fa/KfLcofa

*

<3>

™

*

4?>

^oyPu/^A^

2..

Jyle>f rttfuch^n'AK'ayt^ Co pe.'fr.ccxpf'K^ eke>-<.'ly .CcmSMaftlaoa

3.

P&z^&k S^cnj-ldL shffiy> no err^e^oochay&cl'&iioK & <&&> ViPfiod^

if. izzcoroerrot'a. h & &o< bd'fy C>P Pcf ACexKanm C^r-» Co ei^Ct steal Seed&.

1- l~G>-yPPiritik. —

Fo-yP^Cc-Pern ~S fi,Dp

&/ cJUeJaffee! pRrnmek m>Hr.

PH milk ypcroet/c^cJo ^t-<pp^Ce.£^

L>^>

pycr^vc>.r-rin^.^

hcK'^CSiO£jQ !*&&7L. J-ys-rK'^Cn<ok c.g,z2^g<.Zs —

*n

P!esx

Jroc^'T^e^ r-'^eol j 'y/'re> p>^.rr>ix-&o

!<-e^>>oe-l5.

/S>rrt^le>.Kee! -rt'C-&~s.

<so-7«sl CcTjAfeet VI"ce

/!\J^ Vtp'/).

— PrcfJ&.cJ^Im

Gri^t C>!^y>noje\ (l6!

J^ye^^pen^ei^-y — Tmeo.!^ C^n> Stef^

o !X^> JLr'c^

g^y

P-e.^e^yiiRn ezyf_eJl^-^l‘' e.'we.o

<^t&n

!^.&

Ruoil&cH.

^uj>y&o A^KaAawcoA/Jjx 57% GuyereA ^4% ^mih'AQ

C^wdxie^J Lcop Ictiaj 'iOC£3Y-n-&. ^ycriAps)

1-wK'fa'c^Kcrm ef^ rlcmo^pd^j ucon ^luiKt-rrteMe — pi)c>!'

PPcRcpy^&^> • fCo>-ix?<a^v-v«gt co cLCe.^ hy 95?a a!

! Acruv.

!^ot^i

vtht'ei& .

eHy Co ^<2-is>u.

?. Shekel b^. c<b/e^ Fa

>^~s

3. P/l r-'Ce/e)

. McH

Potx^s

y3»e y-e

^es>Kj

/?zyx-> gA^/^gtyy

ixJ&fJCAarS

rruji^oF o.ll

b&-

F^a,

haye.

)F>K Ft

/cttfzy/^y

oP-A^ti

s ^y>ple^>t.cYik^Kor) scFa^xe.

— »<<e^.X&.A>Ze. fioot Zv-u^t'A'>£> Z>-e. p>erpL,tlAn-6oeJf.

'

—

—

1-ea.Fj

fo&- Ctr>CXG^>£.et

VCKvC^^i'e‘£> c>F

^c>

et&rt/p-i

O~^icL ma.$s> rnedU'ez. SkcHpcCh-e

inUcpe^L .j2e&£..eff' pvtuP

PoinF^

L Pocgx.1 ■sesiA-v'ce^o of VrFP J Cok^Pes^z^s.

'

>

v

2. Prt>eFucK'O>~>/SKcrr^j&.JpyR.y2^y^P'^>-> oF

3. OpS-e-iizd ’s^tP^tP'Cir-icJ /TnStfdsZo c/ yOMq

cFHai'^n.

Rich

V>T^p.

Pnimed ^cn^y&e^>

Fe>&P£>

^?®A-3o-Ao

Z^X/fc -

en» •

e>

^ceZ^rv-Lt'

*e->i'

£ce>~7&^>

Z-eVe-x—6-/o<a^»ri

R&o/ e

‘yt«./<e^ok'n

Ghee

plc^h ^cr^-<c-e^>

,

(^ejj(PeKnoi)

^>pCnc\.e.h> 6.ero

/^rz?»y<=<-xj^ _-246 ~H Ci>

z®Z'*

Cc»'

.)

*pAsnpk-

2/7"4»3

- if:^"-2aT>

trilz-

/O -^UUL‘'->

Oxt^a? -35

Rt^pe. /cnnTi^. ho-^3Z

Qc’.hbe^e. — 2/ 7

Vetf. Scrurc&o - & G^Ypf'e^e Pravr)

Gnr&Z-n leo^SOUrcas

P-rne^-i'ciJ/'h }j3-eeJr)/f^-ckb^hj'/Gtolkh)'J5pcs~>cs-e.h

i)Fo)' e>>

PiAult'

Chu'lck

eLitih

ii) £o.y<^<s. piec&o]ycuv'eecC. ,

8 Cevrofcrig.) ckoy

15<x>-/&tz>^y

>•

=

v

/oo <J»

cpsCertS

HPsgjyg

posgs ox--'

mPake.

liver shares.

ii>)

Kf

\C<c/2x^/'g~>r>

lens&o

5uysyo/o»?eo^

CcsTo/fe^oZ C^ ,9^^/ milk.

JS^^-cAve./^ rax^e X/'/O

S<x.ppk^e4- sPeA. be

S&.rii»UL£>

Pmhlrc.

M-eeJfa Probfe-m

TP>cJLjXX .

I mUhcrs-> coses of j&h'ncfaett cLuji k tftfi

E-^Yjim^Ye.^

PoT>e»-/t/ae>e> Ke^e^farncJacec^ c.CL>o&ojyr

So-S©/^,

P>e-t5ch-> o&) eb>lfa<r^(chje^ciesJ)

LOcs^

A^o-wo/a^ 7e^>nifae,<iM, F)7‘t

Qihor .

£S££ X-jcU-ck)

Pr'evaJsnae^

^/j/yrcrp-cA) .

/^e^gxsA. ■

,

J^fe^Y&K'crr-i tAsi fa tlCH r F~P 5ej»v»ceo

Z. h.ojcfa l.u

of VitP tn

f\loj^er>->o.l k^ Aftznto P Z^ro p^>y 7Ckxj'S

oil cmallyy^^M^

/^»euvu>>>e Pcv~

P>e.^&nKi'cm op &h'r~»ckf'>&ss i>j CA;/d»or> (/?7<p)

/97o-7<r

Z9 cL»s^e.>fe/Z©Mjfe{> Tfe 974/j^S^o

S- lt O '^) ~ti

<3^.

Se/Severn o/pe^&s-i <zy

Pe^<

exg - S/'cJ’e. h-lt

*

K-t'Ken^ O-^y'c&TS

cvigl.<y? t>?

I

Urbcx-O

tJe/Ax>e. CJCnfc.es?

C-hilck

Hfbc^i F~.PCenPe

! FP IteaJK Z?ss£

l4cr?pJ'bJ& .

7^7»/y Ff-eymes

Gr®^?^y?ex/

— Sped Pic.

.

, ,

t,

lU ]

LUvlPHtJ ?

cJ^o^z^> Pcn^

.

-a<ey?sei/^cL c^.m^ •

/'t'U ^yee^»>.

_ __ L.___

Gv/B- SAcn^ sAei/A' AZ^r af

.

Afe>g\//A

caJtem •

Pie^~> <2cLla.coJ4ertn o-rtd.

P-rokflje^rm^ esf Viy pi 7^^ -3< /?cJv. <^p>ey>hylmekir pctyon^

^‘vcA./tACx/fcno - ^<ase/tz>e 5ucnvews//2ei?e«a^c/ Su-B^yS

Racef-'eX^ — ii-k ild.

i4^-f,))t~, Pee cn'el^Q

PePCf/^ ~

PROS.

I.

MG'S

13Pr4&LP7D£SH - fiov’*Af-jy^o»7®c

recL

p^t^'oeLi'a

7_9-75 .

r^c^SSj'ys. <Jo«e y7ro^_«w»

»e_^Z&r5

*

-~P)ll 0—6 yr c/->»/eV>-ey> ^/ve^o ZoCjcero/L> _ 77^

*7?

£<xpsulc

—ZL^uoZn.-A?uA^feesi /hvertA&'fa hlMEP. S^Ff'..

— 6‘5%>

cJniltA. fZ^op^l ^-!^i'>^~> fp_&.c

*.ch-ed-

.

^?. Xz/Oo.A/gS/^ — /■'e-r-t'c’cL-ic. m&uooi'rc- ctose prar^'fanx^

5 (pezr 2yx>) „ CsypSct/eo

^.LeJzh !\P. Ytf f^.cx^

Qo !l> 'iacaplygj^y) e^cjg.faJ'e - cx.ctmrt 6/Annua.l^ jby

!e>c>too& cAiM>eo

Cc?XE»n42js(. .

li.-h^r

*.5-r^no

Z?e^

• PHILIPPINES -C-E& U

C^ fZ>'f’crv~i~r)CJZ-^ <5^ ^7c».va^

r>n&.vkeeily

3. y-r

*

pii^P

e.^(ipTL

3 Shre>J'<eefi

0 S. LeJchjfa

ft) P^hh'c. healfP

Pcvfre^JK.cneJ o.c.K-y4V<a^&

Coo^ Tt^ j£jSpec/fve^ie^»o a>/

<f ■ £<- SGLWOaX

- S<4 ck y -

^yoJ^Q/ut^t

^/yQ_.

•

—VtLQko all c/n/lt^Lnt^)

__ capsule

ZLclIcK ID VJT fj 4- I40 ID

l4osp.-^e-cm'ck PtZYX'^i^J

laS^cA

^.£.______________

Per? &YeJiA.Qj&>ct

P^O^i -TO^rMYi e.. (jQc/jyC- Vir-FL^e-!*>&£■ Ceryne^l cl&owtf')

i) Pe-Ve^-) fra>.l

Cc«-rex>o ^0%^

.

.

*

y<Zs^h/kcJrnft

-

v) ffra^olt^o'l'

f/d X- M \f/-

NOT/ZlT/c^!

fZ£.UF)8lLWnOfiJ

&■■ VfenXco.Za.siAJamy'

"

C<e/-?/ne.5 4/7

Pre^o.le^tc.& oP Yi'F P

CJ-iilcA. Ccx.r&

&>

PxscA

chiAt

*

/46> '/z7/c

.^<^s

*

y eu'cpis

- 2.^Z"7t>

^p&^- q%O'7°?6

$/xckAe-^ y >) Dernan&facJ’fcrr’)

beat's

em a. scJccK><

Grt'o^cAe^Hri~^l /&^^eAj2.T£ / G^euZP

eJorfeut

VfrP duef.

P&cxA 3upp/&^>e^>P Car?Stefa

^~O —&Q

3cr&c> iD oFofen>e

.

NuP-r'l'Fcrr-} p-eLmce^Kar^ j

Mc^ch'^e^^

Rjzov'.lfo-------- ------------------------- ----------

E-^tc^ e>? Eeeclesvj Cm ^^ophfl’/cJrrnek .

______gxryta/y^z ■$,_ cff Jit

C~/<^z>>3y%

ckilt)>e+>_____________

On ouaL»?>»»‘a»^....

-.h^M.hthdo^.

.

...C<s-nj. ^€/ia9^ ____

3.

B,^Spo^

Lk._

/e>9

cm cU

Z547/ ...

Ufl

/_ __754.0__ Z/7 « ~2

go

&

£-vp)L.t>nri

I.

iScX'S^. h'r->e. ^Si^-ny&y ,

3..

Gx^evt’cs Pw

public. hjzeJpi p'fdffolfGrn .

J^ Opc^oJ'eormeJ &‘fip^clr>

e&v ■

t)J Ptt'ol a-z^ccesJ <s^pec.f>rvC^i^'&&

yC>>€ v»Je-Qce et^

^~in >eeJ

rnie< &y ViK

^)p> — /?&/ex^>eQ-

! Co&p b&>d-rb

CZM^

VOLUNTARY HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF INDIA

C45 SOUTH EXTENSION PART 2 NEW DELHI-110049

NUTRITIONAl BLINDNESS ANO VITAMIN A

HAI - 240

VITAMIN

AREAS

shaded parts of Map)

Bihar

Bangla Desh

Orissa

FDIET SOURCES

OF VITAMIN A

Andhra Pradesh

Tamil Nadu

Spinach • Carrots

Mango • Papaya

Pepper and Fruit or

Vegetable

Yellow or green on

the inside

EXTENSION PART 2 NEW DELHI-110049

NUTRITIONAL BLINDNESS^Dry Eye or Xerophthaln^) IS PREVENTABLE

TREATMENT

X-0

Night blindness : the child

stumbles in the dark.

Some brown pigmentation may be

seen around the edge of the

cornea.

X-1

The white of the eye is dry.

If in doubt, hold the eye

open for half a minute.

White triangular patches that look

like milk powder or white paint

may or may not be seen on the

outer side of one or both eyes.

(Bitot's spots)

X-2

The cornea is dry.

It looks hazy.

It has lost its shine.

Eyesight is now in danger. Both

eyes are usually in danger at

once.

For rapid effect, give Vitamin A

in watery solution by intramus

cular injection immediately. Also

give some protein-rich food. (3)

X-3

The cornea ulcerates,

the iris prolapses, or the

whole cornea melts

(Keratomalacia)

TOO LATE

Partial sight can be saved tn only

a few.

j

As well as treatment as for X-2

above apply local antibiotics by

injection, atropine eye drops or

ointment, pad and bandage.

X-4

White patches and scars

cause permanent blindness.

TOO LATE

The child is left blind, totally or

partly. Usually both eyes are

affected.

NIL

Only a few

corneal graft.

Green leafy vegetables, eaten

daily,and oral Vitamin A, 200,000

units in oil (as capsules or liquid)

every 3-6 months prevent the

disease. Newborns, until they are

5 Kg. or have doubled their

birthweight, only need quarter of

this dose. (1) (2) (3)

are

suitable for

DOSE

SOURCE

40 Gms or 2 large

spoonfuls daily of

spinach or green leafy

vegetables.

OF

SUPPLY

Seeds are obtainable locally, or by mail, from Pestonjee P Pocha, Seed

Merchants, 1 A Middle Road, Pune, Maharashtra.

Concentrated liquid Vitamin A is obtainable free from the District

Medical Officers in Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu,

Karnataka and Kerala, and commercially from Anglo-Frehch Drug Co.

Eastern Ltd. 28Tardeo Road, Bombay 34 W8. High dose capsules are

obtainable from Seamless Capsules Ltd. Box 2262 Bombay-400002.

■raton ki goli' con

taining Vitamin A

200,000

units

by

mouth, twice yearly,

in oil, as high dose

capsule or concentrated liquid, 2 ml teaspoon

supplied= 200,000 units.

Vitamin A aqueous injection (2 ampoules=200,000 units) is

available from U S Vitamin and Pharmaceutical Corporation

India Ltd. 43 Dr V B Gandhi Marg, Bombay-400001.

200,000 units of aqueous Vitamin A, by

intramuscular injection, immediately, and

not repeated for 3 to 6 months, except

on doctor's order ; combined with rice,

dal and green vegetables daily.

RECORDING OF MASSIVE VITAMIN-A DOSES

Record as immunisation by writing the date given

8

"Zfjo -

AAW'

/<r&

' -HI

L

■

DPT TRIPLE

1^7^-

IT 1 Nfc J

£

or record on the growth or weight chart by writing

a large’A’ opposite the month when it was given.

COMMON SITUATIONS LEADING TO NUTRITIONAL BLINDNESS

POSSIBLE ACTION

PROBLEM

Infection such as measles

whooping cough

diarrhoes

tuberculosis

typhoid

Green leafy vegetables are not available in the village.

Green leafy vegetables are available.

1.

Treat the infection

2.

Do not starve the child (except in early typhoid). Advise or give

extra food, including green leafy vegetables daily. Explain why.

3.

Protect the child for the next 3 to 6 months by giving him 200,000

units of Vitamin A by mouth, in oil. Explain why.

1.

Make seed packets available for starting a small garden of green

leafy vegetables. Use waste water from the house, and protect

the garden from goats and chickens. Start many such gardens.

2.

Give 200,000 units of Vitamin A by mouth, in oil, to prevent dry

eye in the meantime.

1.

An aide or another mother can demonstrate to mothers, how to

feed green leafy vegetables, and how the children like them. Keep

spinach for demonstration.

2.

Teach all staff a simple slogan to teach mothers, such as

greens every day’

3.

Take help of school teachers, village doctors, leading men and

women, and shopkeepers.

But they are not fed to the child.

'eat

PROBLEM

POSSIBLE ACTION

Night blindness only, or conjunctival signs (the white of the eye only is

dry) is present among some children in the community. Village people

will be able to gather for inspection, those who complain of night blind

ness.

Vitamin A in oil (retinol palmitate) given by mouth, in a high does of

200,000 units has been found the most effective treatment. Village women

and schoolteachers or dais can be trained to give all affected children

the Vitamin A, and repeat it every 3 to 6 months. The oral route is

best for slower abserption, and the oil aids absorption from the intestine.

Absorption takes several days.

The central dark cornea is hazy and dry.

Vitamin A is urgently needed in a rapidly absorbed form. High dose

aqueous injection of 200,000 units of Vitamin A is recommended by in

tramuscular injection. This will take effect in a few hours. Use anti

biotic eye ointment to prevent ulceration.

Paramedical staff, village leaders village doctors and village parents do

not, recognise the disease.

Use the eyes of children with night blindness to teach diagnosis and

treatment and prevention. Use posters and coloured Pictures also.

High dose Vitamin A is not available

Use Vitamin A and D capsules each containing 10,000 units of Vitamin

A, until high dose capsules or liquid can be obtained. These capsules

are widely available in chemists shops throughout India.

Also use liquid Paraffin eye drops to lubricate the eyes till the Vitamin

A takes effect.

REFERENCES

(1) Gopalan C (1970) Am. J Clin Nutrition 23 p 35—51

(2) Pereira S et al (1971) Arch Dis Childhood 46 p 525-527

(3) Pereira S et al (1967) Am J Clin Nutrition 20 p 297-304

(4) Pereira S (1975) personal communication

PHYSIOLOGY OF VITAMIN A

INTAKE

ABSORPTION

is from vegetables in

the form of carotene,

or from animal sources

as retinol

is with the help of fat

or oil in the diet, and

of the bile salts, in the

small intestine

STORAGE

TRANSPORT

ACTION

PATHOGENESIS OF VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

POOR INTAKE

POOR ABSORPTION

POOR STORAGE

NO PROTEIN CARRIER

DAMAGED EYE

refugees

war

poverty

ignorance

dietary customs

famine

crop failure

infections

withholding food in illness

insufficient solid foods

for weaning

feeding programmes

relying on unskimmed

milk containing

no Vitamin A,

diarrhoea

sprue

no fat in the diet

obstruction of the

bile ducts

inadequate stores built

up in the liver, due to

poor intake and absor

ption.

Severe liver cirrhosis

severe protein lack in

the diet as in

kwashiorkor or marasmus

when cornea is already

damaged due to viruses

of smallpox, measles,

or

other

neglected

infections.

When the eyelids can

notclose.

•

IS YOUR CHILD BLIND IN THE DARK?

“Is your child blind in the dark ? Feed him more

green leafy vegetables and give him Vitamin A

twice yearly."

This poster is available at cost from

Voluntary Health Association of India.

It is available in Hindi, Bengali, Oriya, Telugu, Tamil,

Kannada and Malayalam.

It is printed on stiff paper, size 45 cms x 57 cms in

4 colours.

Copies of the above poster and of this brouchre on Vitamin A and Nutritional Blindness are available at

cost plus postage from :

VHAI Community Health Programme.

VOLUNTARY HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF INDIA

C 45 South Extension Patt 2, New Delhi 110049.

Printed with the kind assistance of Christoffel Blindenmission, D614 Bensheim Schoenberg, Nibelungenstr 124, W. Germany.

'Pcfsex’u/wc^ oT Pets&i 2W Z££zJo^t/wj

rh

■

veK‘- °< kr«/e«„^ .

Social Medicine

St. John’? Medical CoJkgK 'S'^

8ANGA t,OR7.560a?<

e.u.u->c

47/1,(First FlodrlSc. Marks Road

BANGAfcQRE - 560 001

QApSU

XjU^-4

4c

.jJayeW;

,^)3ibtc_

-0-s<a4

O'fcU

BANGALORE - 560 001

f• 1 V

ca-Li-

Q

ifefe

^ncUo

>■< A..A_A_

L^jl"

H/:

CaJT'

17-S

112 -2,

IS.7

22-1

H7- 7

21 • 6

/22- 7

t^-

<• f^s

US-1

127'3

2b^

127' 2.

Sif-'SZb-o

/£?’ L

3d-0

133'/

S.7-Z

123-3

/^7>D

!3S ■ <T

>^3'^

Hf-Z' 7

'oP6

D

2S-S

^■1

H>i ' 7

/L^'3

•

33'6

37

/£7 ■ o

^3- o

133-

4-4- S-

^’•2

/^3T- D

^•7

5^-2

/a-T

S "'

JZb-b

COMMUNITY health CELL

«7/1» (First Floor) Si, Marks

BANGALORE - 5uO 001

V7-^'

47/1.

rrvst. Warks

,.560 001

bAMGAlO3‘--suu

MALNUTRITION

Malnutrition has been defined as "a Pathological state r .suiting from

a relative er absolute deficiency or excess if one. or mere es '.ntiaJ

nutrients, this state being clinically manifest:.- ?r d:tzctur nly by bio

chemical, anthropometric nr physio logical tests".

Four forms

malnut 'ition hove been distinguished. (l) Undernutrition s This is the c ndition which results ijhcn insu ’“ici' nt fis eaten ever an extended pericd of time. In extreme cases, it is c.lled

starvation. (2) ( vernut rit ion • This is the pathological : c

resulting

from the consumption of •■xna;sivo quantity of f.: . -wsr -.n c>- ondei ■. nriod

of time.

The high incidence of obesity, atheroma

md diabetes in western

societies is attributed to overtiutritinn. (3) Imr."lance = It is the

pathological state resulting from a dispropert i .n among essential nutrientswith or without the absolute deficiency of any nutrient. (4) Specific

deficiency ' It is the pathological state resulting from a relative cr

absolute lack of an individual nutrient.

Classification of Nutritional Diseasea s

The UHO Expert Committees on Nutrition (1962, 1971) proposed the folio,

ing classification of nutritional diseases s

Nutritional Diseases :

HYPOALIMENTATION s

1.

Prot --.in-calorie Malnutrition (PCM)

(a) Kw-a^qrkor

(b) •'lutritigiu.i marasmus

(c) Severe PCM, Ui,nuaiifj_eci

(d) Moderate PCM, u, ~r,QCipieci

(e) Other PCM.

(f) Malnutrition, unspecific

(g) Nutritional dwarfism

3.

Vitamin deficiency

(a) Vitamin A deficiency

. (b) Thiamine deficiency

(c) Niacin deficiency

(d) Aribcflavinosis

(e) Deficiency of other 0 complex

vitamins

(f) Ascorbic acid deficiency

(g) Vitamin 0 deficiency

(h) Sprue

(i) Vitamin k deficiency

(j) Vitamin

deficiency

2. Mineral deficiency

(a) Iodine

(b) Eluorine

(c) Selenium

(d) Calcium

(c) Others

Co) Essential fatty acid defier

(b) individual amino acid .

defies, riricy

(c) Other stutuo nnd unsptciri-o

HYPERALIMENTATION ;

FOOD TOXICANTS •.

(a) Obesity

(b) Hypervitaminnsis A

(c) Caretenaemia

(d) Hypervitaminos is D

(e) Fluorosis

(f) Other

(a) Lathyrism

(b) Epidemic dropsy

(c) Aflatuxicosis

COMMUNIS •IEALTH CELL

Marks Road

■ . 5 60 001

Diseases of the Bleed end Blood Organs ’

PERNICIOUS AN.iEPlA 8

(a)

Subacute combi sed de : ..aeration

NUTRITIONAL DEFICIENCY .INmEWIA :

(a)

(b)

Iron deficiency anaemias

Other deficiency an-'.r'ias (folic acid, vitamin 3 , vitamin B ,

. . x

12

6

protein)

INDICATORS OF I 'LNL’TR£~1 - L

It will be useful t bear in mind the following "indicators of malNutrition" while assessing he nutritional status

well as evaluation

of nutritional programmes in a community.

(l) Statistical;

(2) Anthror jmotric ?

(a) the mortality in the nge-group

under one year (especially 6-12

months)-

(b) the mortality in ttvu age group

1-4 years.

(c) the ratio :-f deaths of children

Jess than'5 years r.f age to

total deaths.

(3) Clinical;

'(a) the weight of the newborn.

(b) the percentage of newborn

weighing less than 2,500 grams

(c) tho height and .weight of

children aged up to 5 years

(d) the average weight of 7-year

old children entering school.

(e) The index weight/height is

regarded as a simple and

reliable.indicator of tho

nutritional status of preschoo'l

children in a community. An

index of 0.15 has. been used as

a dividing line between well—

nour;~hed and mal-nourishcd

children.

(A) Di.etar.j'. Examination--

(a) the number of cases of mal

(a)

nutrition admitted annually

in hospitals and hca1th centres. (b)

diagnosis pF indivi dual nutrition

al deficiency diseases.

(c) the proportion of pregnant women

with less than 10 g of haemoglobin

per 100 ml of blood in the last

trimester of pregnar;cy«

Intake of calories, proteins

and other nutrients 8

Studies of dietary habits.

Degrees of flalnutrition;

While studying malt.ijhr.tion ininfancy and childhood with special .

reference to kwashiorkor, Ccn>ez(l955) was able to draw up the following

classification by assessing the percentage of underweight in relation to

average

(l) First Degree Malnutrition-

Weight between 85 and 75 per cent of

the theoretical average for the age

(2) Second Degree Malnutrition;

Weight between 75 and 60 per cent of

the theoretical average for the age

(3) Third Degree Walnutrition?

Weight below 60 per cent of

the-th»OTgtj_cal..waKt!rage--fOT the

age.

ST. JOHN'S MEDICAL COLLEGE, BANGALORE

ti eJU-ix

Cflass

Roll No.

Semester

Subject

Examination

Date

4

US o<-( d. 4 <s_cc(LtU

47/1«(Fi;

' 56,0 001

Cu^jclo-^ cc

dzi

i-^-xXZGMy

er^oerrv^ t”?.

(C&

7o. ~ £o. %

GjOws-j ~Pc^>-As^

Itji /- ? cu^-x©.^/ _cSh.

<aS<3J'g_ U.LdmjS'

,|t-uutC^v XeXped

vM-CUd_L«-sai'

<tz/e^d^,y

Ocue^ _ c_ roXto-. .^'S.JUuseJLs

4

2

, '

__ <

,y<J. >>iCwJcLk_Ky

kk. iCLg.

c^p’

C'fecx.v^. _JU4_a_Xvu2L

<S c.'g ifcaji

•*

. ieo-v-j

.jan'gjedka,-

' <aJo-r e' P-vXstcD. <

CJ~ ^ZX2-C^-Q.

e^_iffe ..

* -a e-Col<Lci_u^7

tlSj^ 1^^

^.0^,

-<eo^ "• •

r

•k

C^L-d<dLuXZM. c“ ^<-c

C-3- ~L eycJ©_C£

*M

C

NUTRIT5OM

AMD

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

'•

aoad

MRS. MANGALAM

TT is said that a man is what he eats. A diet

A sufficient in quantity and adequate in its

rWPition content is the foundation of good

health and well being. It is also an important

factor in raising productivity. Therefore, nutri

tion cannot be separated from health and any

nutrition programme will possess a health com

ponent. One might argue and say that nutrition

will not take place in the absence of an adequate

purchasing power for our people. True, but we

cannot wait until a reasonable standard of living

is achieved. This is because nutrition is the very

basis for achieving an improved economic status.

The objective of nutrition in any Primary Health

Care Programme is not only to prevent malnutri

tion but also to promote positive health.

As correctly said by Dr. David Kerner, if

we all took more care to eat well, to keep our

selves, our homes and our villages clean and to

b^-ire that our children are vaccinated, we could

st^l’most sicknesses before they start.