ALCOHOLISM

Item

- Title

- ALCOHOLISM

- extracted text

-

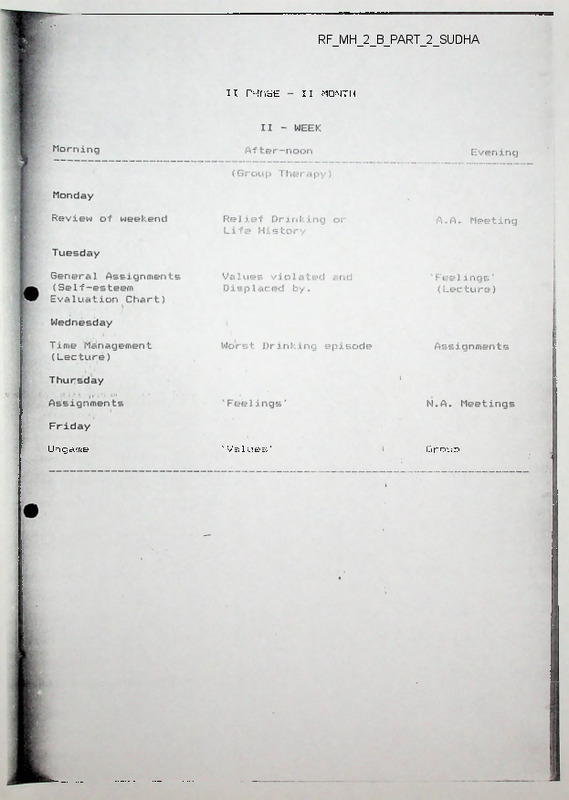

RF_MH_2_B_PART_2_SUDHA

II PHASE

Ungame

'Values'

II MONTH

Group

SEXUALITY

AND

RECOVERY

SEXUALITY

AND

RECOVERY

by

by

Barbara McFarland, Ed.D.

Barbara McFarland, Ed.D.

hzelden

First published November, 1984.

Your reason and your passion are the rudder

and the sails of your seafaring soul.

If either your sails or your rudder be broken,

you can but toss and drift, or else be held at a

standstill in mid-seas.

For reason, ruling alone, is a force confining;

and passion, unattended, is a flame that burns to

its own destruction.

Therefore let your soul exalt your reason to the

height of passion, that it may sing;

Copyright © 1984, Hazelden Foundation.

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication

may be reproduced in any manner without the written

permission of the publisher.

And let it direct your passion with reason, that

your passion may live through its own daily

resurrection, and like the phoenix rise above its

own ashes.

*

Foreword

ISBN: 0-89486-246-4

Printed in the United States of America.

Editor’s Note:

Hazelden Educational Materials offers a variety of information on

chemical dependency and related areas,. Our publications do not

necessarily represent Hazelden or its programs, nor do they official-

In writing this manuscript, I have primarily focused on in

dividuals who are heterosexual. However, in my professional

experience, I have found that gay couples I have treated have

also fallen victim to cultural stereotypes. Despite the fact that

the relationship might consist of two men or two women,

there often is still a dominant, or stereotypically “masculine”

partner and a more passive, stereotypically “feminine” part

ner. All relationships are based on certain expectations which

have been greatly influenced by our beliefs about what is ap

propriately masculine and what is appropriately feminine in

our culture. Gay individuals can still apply the principles and

ideas of this pamphlet to their own recovery.

* Reprinted from The Prophet, by Kahlil Gibran, by permission of

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Copyright 1923 by Kahlil Gibran and 1951 by Ad

ministrators C.T.A. of Kahlil Gibran Estate and Mary G. Gibran.

Perhaps another issue that needs to be addressed is that

often people are not in a committed relationship. However,

we do relate to members of the opposite sex most of our

waking day. Stereotypical attitudes can interfere in the

development of positive healthy work relationships, or friend

ships. Therefore, learning about one’s predispositions toward

sexual stereotypes can influence all relationships in a positive

and healthy direction.

Regardless of whether or not one is heterosexual or

homosexual, in a committed relationship or not, rigidly

adhering to one style of relating — dominant or passive — is

detrimental to the relationship and to the personal growth of

the individuals in that relationship.

Introduction

To admit that alcohol or other drugs have made life un

manageable is a beginning — one which is often a major

catalyst in getting a person into treatment. Usually by the

time someone enters treatment his or her life is a shambles, or

close to it. After all, the disease affects every aspect of a per

son’s life: psychological, physical, spiritual, and sexual. Yet,

sexual aspects of recovery are rarely dealt with.

Sex is uncomfortable for most people to discuss unless it is

in the context of a humorous anecdote or an off-color joke J

Consequently, sexual issues in recovery are overlooked com

pletely or only minimally considered as a treatment issue.

Perhaps this is due to an underlying assumption that the topic

should generally be limited to a discussion of sexual activity

or sexual performance, which is considered a private matter

best left alone.'1

Gender Identity

The physical aspect of sex is only one part of sexuality. The

other aspect — the one that is most critical and has a direct

impact on sexual performance — is what we will call “gender

identity.”

Gender identity is the way a person defines him- or herself

as masculine or feminine. There can be a cause and effect

relationship between gender identity and sexual expression.

People who are more accepting of all aspects of their sexuali

ty — their maleness and femaleness — are more able to be

sexually expressive in an intimate relationship.

In order to understand gender identity more clearly, let’s

look at the reentry of the recovering person from treatment

into normal life.' For both men and women, this reorganizational process, integrating sobriety into a life previously con

sumed by alcohol or other drugs, is deeply affected by their

ability to follow standards of sex-appropriate behaviors as

defined by our culture. The underlying assumption is that

such sex-typed behaviors are conducive to personal happiness

and allow men and women to function in the mainstream of

society. As a result of the women’s movement, it has become

increasingly evident that this assumption is wrong. Adhering

to rigid stereotypical behaviors, attitudes, and feelings blocks

personal growth and negatively affects the quality of a per

son’s relationship with self and others.

Stereotyped Roles

Despite the strides the women’s movement has made in

most areas, our culture has continued to perpetuate the vic

timization of both men and womeq by encouraging people to

accept stereotypical role behaviors.('The recovering male is en

couraged, to resume his role as head of household with all the

privileges and headaches inherent in that position.] By virtue

of his place in the labor market, he has the power and con

trol to make major decisions in the household. However, he

also assumes total responsibility for the economic security of

all family members, Given this role expectation, he must be

strong, aggressive, economically productive, and rational at

all times.’ One of the obstacles the recovering man often must

ft •

overcome is the repression of his feelings.

The recovering woman, on the other hand, is encouraged

to return home and resume her nurturing, caretaking, submissive/passive role of wife, mother, daughter, or employee.

The privileges inherent in her role are economic security and a

deep sense of emotional attachment, which are supposed to

give her a sense of purpose and belonging. One of the major

obstacles the recovering woman often must overcome is her

repression of her own internal resources — resources which

help her develop a degree of confidence in her ability to take

care of herself.

The man becomes an emotional cripple dependent on her

nurturance, and the woman maintains a childlike existence,

dependent on his economic power and decision-making skills.

Even lesbian/gay relationships Often take on the

dominant/submissive dynamic&HThis division of labor has

retarded the ability of men to be nurturers and caretakers, as

well as that of women to be decision-makers and bread

winners. As a result, neither gender is able to experience

other aspects of their full potential as human beings.

Even with single persons who are not in a committed rela

tionship, there can be a vague feeling of emptiness. Though a

woman may be working and economically self-sufficient, she

may miss the “status” and “strength” of a male/ The single

man, on the other hand, who has been taught to !be more in

dependent, often tends to look for nurturance in his sexual

encounters with women.

New Choices

There have been changes, but old attitudes die hard. People

are beginning to realize they have a choice. They can in

tegrate many aspects of masculinity/femininity (as defined by

the culture) into their personalities without feeling guilty or

ashamed.

Take, for example, how unusual it was a generation ago

for a man to go grocery shopping, diaper a baby, hug

8

another man, cry in public, cook and sew, or take care of a

sick child. It was quite unusual then for a woman to pursue a

career, pay alimony, be sexually aggressive, choose not to

have children, be athletic, make more money than her spouse,

or give up her children in a divorce.

The cigarette ad that cries “You’ve come a long way baby”

is also making a statement about men’s sex roles. As things

change for women, they will also change for men. This can

be frightening to many people. Adhering to old sexual stereo

types seems comfortable, easier, and much safer. This is

especially true for the recovering person.

Because of the failure each feels in not having lived up to

cultural expectations while using alcohol or other drugs (being

the good wife and mother, perfect daughter or employee, or

the strong, rational husband and father, or productive

employee) recovering people often try desperately to succeed

with these sex-typed expectations. They may cling rigidly to

what they believe will alleviate guilt. Keeping mired in guilt

and trying to make up for past failures only increases the

deep sense of inadequacy. Letting go of these old attitudes is

a beginning of healthy recovery. What makes this letting go

difficult is related to the role alcohol and other drugs played

in the sexuality of the dependent person.

Sex Role Stereotypes and Chemical Dependency

Women have been divided culturally into the Good Girl

type and the Bad Girl type. The Good Girl is the “ideal”

woman — chaste, thoughtful, loving, selfless, kind, generous,

and highly moral. She is a paragon of virtue. The Bad Girl is

the opposite of this saintly creature. She is a tough, pro

miscuous, aggressive, selfish person who thinks and drinks

“like a man.” Women struggle with these bi-polar conflicts,

especially in the area of sexual feelings, since our society has

tended to view the expression of sexual desire as inap

propriate in a female, sometimes even immoral.

In order to maintain the Good Girl image and yet be sex

ually responsive to a partner, many women use alcohol or

other drugs to loosen up, to lower their inhibitions so they

can feel sexier to please their partners more. For the

chemically-dependent woman, this only escalates her disease.

Her drinking gets worse and her self-esteem plummets. She

has become the opposite of what society says she should be.

Having sex while intoxicated helps her deny her true feelings

about her own sexual expression. It’s a great excuse the next

day to look in the mirror and say, “I was too drunk last

night ... I really got carried away . . . oh, well, if I hadn’t

been drinking, I wouldn’t have done that.” She blames the

desire for sexual activity on alcohol or other drugs. That way,

she can still be a “lady” in her own mind. This helps preserve

the female gender identity of Good Girl, at least for a while.

Once into recovery, women are often faced with the dilem

ma of being “good” yet sexual, and must solve it without the

use of alcohol or other drugs. This is a major recovery issue

for women, one that is difficult to discuss because of the

social stigma which has been attached to women who show a

desire for sex. Chemically dependent women have an especial

ly difficult time because of the additional stigma associated

with the disease.

It is interesting that, for a man, the reverse occurs.

Culturally, a “real” man is sexually aggressive and selfassured, not promiscuous but a “playboy” — tough, strong,

and independent. This is the Marlboro Man, James Bond,

Dirty Harry. Culturally, a man who is sensitive, insecure,

emotional, or sexually shy is viewed with disdain. He is

something of an anomaly because of his “feminine”

behavior. What is acceptable for women is not for men.

In order to cope with this image, alcohol or other drugs

can give the man a dose of false courage, the machismo to

“stand tall” and to “bite the bullet.” It lowers his inhibi

tions, too, for different reasons, but the result is the same.

Affects on Sexuality

: Just as there are stages of the disease, there are also stages

of the disease’s effect on individual sexuality. Initially,

chemicals are often used to help a person feel more comfort

able with sex, and more sexually provocative. During the mid

dle stages of chemical dependency, they help the person cope

with conflicting feelings of gender identity and sexual expres

sion. Of course, in the later stages of the disease, sexual pro

wess and conflicting feelings of gender identity become less of

an issue, and the desire to drink or use other drugs becomes

the individual’s primary focus in life.

Alcohol and-other drugs eventually affect physical perfor

mance. For males this might mean difficulty with erection or

premature ejaculation. Many men dread not being good

enough in bed. Because of the stereotypes, most of the

responsibility for sexual initiative and creativity falls on the

man. This pressure can, and often does, lead to impotence.

For a woman, frigidity, shame, or embarrassment might

result from things she did while intoxicated. Because she is

ashamed of and often confused by her sexual feelings, she is

unable to communicate her sexual needs. Her self-hate in

creases, but alcohol or other drugs help her cope. These sex

ual self-images of failure have been embedded in the

chemically dependent person’s mind. Sobriety makes them all

t^ie more a reality.

1 For example, a sexual memory that may haunt a male

might be the painful recollection that during the last several

attempts at sexual intercourse he was unable to achieve an

erection. The ridicule, criticism, or even silence from his part

ner has diminished his self-confidence as a fully functioning,

competent, and desirable sexual partner. Alcohol or other

drugs would numb this fear, but in sobriety he may feel trap

ped unless he is willing to risk again.j (V)

A woman may hold on to the memory of how sexually ag

gressive she was and how her moral values deteriorated dur

ing her drinking or other drug use. These sexual images deep

ly affect her self-esteem. Alcohol or other drugs will numb

her self-hate, but sobriety can keep it alive unless she is will

ing to forgive herself.

In recovery both sexes need to transcend the male/female

stereotypes in order to shed their old rigid sexual images.

Sexual Recovery

■ These painful memories are difficult to shake because there

is nothing to replace them. Cultural pressures and the effects

of alcohol and other drugs on psychological and physical

levels of functioning play havoc with the development of a

healthy gender identity. In part, chemicals are used to help

the person be what culture dictates. This is how they promote

sexual deterioration in the chemically dependent person.

Physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects of recovery

are fairly easy to determine. Physically, abstinence from

mood-altering drugs and adherence to a suitable diet improves

the body. A.A. meetings, therapy, and working the Twelve

Steps of the A.A. program improve the psychological realm;

prayer and meditation improve the spiritual realm. But what

improves the sexual? What benchmarks or goals can in

dividuals look at in order to make strides in their sexual

recovery? Frequent sex is not the answer.

Recovery in the sexual sphere means the recovering person

must go through a process of self-examination. Specifically, a

recovering person can look toward experiencing five stages of

sexual growth. These stages are not rigid and regression is not

unusual.

Being all masculine, drinking or sober, makes a man feel he

has to prove something. While drinking, it can be how much

booze he can tolerate. While sober, it can be how he can

“beat” this problem on his own. All masculine means, “I

can handle anything.” Needing others is a weakness.

Being all feminine, drinking or sober, makes a woman feel

she has to have someone take care of her. While drinking, the

alcohol can keep her helpless and nonfunctional, pulling peo

ple in to take care of her. While sober, she may be getting

sober for everyone else so they’ll take care of her. All

feminine means, “I can’t handle anything without someone

helping me.”

A person can become trapped by personal boundaries of

stereotypical sex-appropriate behavior. These boundaries can

be a safe place to hide. For men, their softer side is denied,

feelings are taboo, and after a period of time, they become

emotionally crippled; their feelings are alien even to them.

This makes it especially difficult to be intimate.

For women, their self-sufficiency is often squelched, and as

a result, their real internal resources are yet to be tested. Be

ing stereotypically feminine keeps a lid on the female’s

strength and ability to master her own fate. Using only half

of one’s potential and abilities causes the other half to

atrophy. As men harden, they become increasingly dependent

on women to nurture them, to be emotional for them; as

women’s strength withers, they become dependent on others

to be taken care of, to be their anchor throughout life.

Breaking Out

STAGE ONE:

Awareness of Self as a Male/Female Person

This stage requires a deep self-analysis of how. the person

defines maleness or femaleness by cultural standards. Before

beginning, one must see how detrimental it is to be either “all

masculine” or “all feminine.”

12

Breaking out of these roles can create problems because the

status quo is being shaken at its very roots. In a stereotypical

relationship, a man reaching out for support can be met with

disdain by the spouse who is fearful her “anchor” is falling

apart. In her eyes, and in his eyes, too, he has to be strong to

take care of her. His move out of his traditional role may be

met with resistance by a spouse who does not want the

balance changed. She fears it means ultimately she must

change.

13

c

The same problem can occur with the recovering female

who asserts herself and wants to become more financially in

dependent by getting a job. The husband may feel threatened,

fearing she won’t need him as much. In his eyes, she has to

need him for economic support; he has to take care of her.

This alters the balance in the relationship and requires the

male to see himself as more than just a paycheck and some

one in charge. In creating a more balanced gender identity,

the recovering person must understand that others may resist

this change and want to keep him or her in what is perceived

as a less threatening position.

Rewards

The rewards for struggling through this major shift in rela

tionship dynamics are immense. With equal, interdependent,

fully functioning partners there are no games or manipula

tions. There is no need to “win” or “lose” when there is

equality. This results in a deep respect for one another’s in

dividuality. The relationship becomes a place to relax, to

share, to let go, and to regroup; a place to feel a deep sense

of belonging and peace.

The recovering person and spouse are used to operating in

extremes. They both need to find a balance in gender identi

ty. Every human being has feminine and masculine traits. Our

culture has taught us to deny the opposite-sex trait. Healthy

sexual recovery requires that people integrate the other side

into their feelings, attitudes, and behaviors.

Can I be both masculine or feminine, depending on the situa

tion?

How do I treat members of the opposite sex?

What do I expect from members of the opposite sex?

As a man, do I view women as “sex” objects?

As a woman, do I view men as “marriage” objects?

Since this is the most critical of the stages, following are

exercises which will help generate some thoughtful answers to

the above questions.

Your Own Stereotypes

On a sheet of paper, write down the first name of a person

of the opposite sex you admire most. List the qualities you

admire (i.e. integrity, kindness, ambition, etc.) in this person.

How stereotypical are the qualities you’ve defined? Ask a

member of the opposite sex what he or she thinks of this list

and your perceptions.

Divide a sheet of paper in half. At the top of one side write

“masculine”; on the other side write “feminine.” List all the

traits that describe you. Share with someone of the opposite

sex who knows you well. Then share with someone of the

same sex who also knows you well. What kind of feedback

have you received about your masculine/feminine self

perceptions?

STAGE TWO:

Self-Examination

Awareness of How Others Perceive You as a

Male/Female Person

In examining your sexual self-awareness, consider these

questions:

How do I feel about myself as a man/woman?

How rigid am I in the expression of my gender?

How stereotypical are my attitudes, behaviors, and feelings?

How easily am I threatened by the unfamiliar?

How fearful am I of letting go?

This stage requires openness and willingness to see how

others perceive you as a man or woman, and how consistent

this is with your own perceptions.

Being able to receive feedback requires the ability to take

criticism. Chemically dependent people sometimes have dif

ficulty with this. Often perfectionistic and their own worst

critics, they typically balk at negative feedback from others.

In order to get in touch with others’ perceptions of your

15

sexuality, you must be willing to accept what may be painful

to hear. This feedback will be the basis for change.

As you work on this stage of sexual recovery, it’s impor

tant to move beyond the safe circles of friendships already

established. It’s imperative to relate to members of your own

sex. A heterosexual man will not usually try to dominate or

control another man. A heterosexual woman will not usually

try to play helpless victim to another woman. Interacting with

members of the same sex forces a person to be more honest

and less manipulative.

In getting feedback about your sexual self, first ask some

one of your own sex how he or she really perceives you.

Questions to consider include:

How do others see me as a man/woman?

How easy is it for members of the opposite sex to relate to

me?

In what ways do I relate to members of the opposite sex, i.e.,

aggressive, dominating, passive, dependent?

How comfortable am I with members of my own sex?

(Women have had much greater difficulty with this because

of the low status ascribed to women in our society.)

STAGE THREE:

Experimentation With Sex Roles

The last three stages are process stages which continue

throughout a person’s life, because, as sexual beings, we are

not static.

This stage involves crossing over the boundaries of stereo

types. Once you have achieved self-awareness and awareness

of others’ perceptions of you, take this information and start

experimenting with new behaviors, attitudes, and feelings.

For example, if you are a man, and you and others

perceive you as too intellectual, rational, and emotionally in

accessible, make a concerted effort to be more open by shar

ing feelings. One way to begin would be to start a daily jour

16

nal in which you record significant events and your reactions

to them. You might also record feelings you remember from

your dreams, and then see how they relate to what is happen

ing in your life.

You can also begin to separate your feelings about what

people do (actions) to you from what people say (words) to

you and decide which has the greater impact. This is another

step in raising awareness of your feelings. Recording these

reflections can be very helpful.

If, as a woman, you and others perceive you as too self

effacing, begin to practice assertiveness. A journal of reflec

tions can also be a powerful tool in raising awareness about

self-effacing behaviors. Therapy and A.A. discussion groups

are powerful springboards for this. Experimentation is pain

ful. During this time you will have to stretch yourself, take

risks, feel uncomfortable with new behaviors. But in riding

these feelings out you will be approaching balanced sexuality.

The key questions to consider during this stage are

How flexible am I?

How willing am I to change?

What sexual defenses have I developed?

What are my fears about my masculine side?

What are my fears about my feminine side?

STAGE FOUR:

Differentiating Between Sexual/Physical Needs

and Sexual/Intimacy Needs

Once you have become more comfortable in expanding

your gender identity, in being more spontaneous and fluid in

the expressions of both your masculine and feminine sides,

sex will take on a new dimension. No longer will sex be mere

ly a means by which you satisfy your physical needs. It will

become a vehicle through which true human intimacy can be

experienced. To someone rigidly fixated in the old sexappropriate behaviors, this intimacy can be terribly frighten

ing and, consequently, avoided.

17

0

The ability to give of oneself to another in the most in

timate of shared experiences requires unconditional self

acceptance as a sexual being. No side of that sexuality can be

repressed.

In sexual expression there is no game. No one should have

to do or be anything that isn’t consistent with the spontaneity

of the shared experience. One reaches out and gives to the

other all of oneself, not just those parts that seem to be ac

ceptable.

The key questions to consider during this stage are

What do I expect from my partner sexually?

Do I communicate verbally what my sexual needs are?

How do I show my affection for my partner outside the

bedroom?

What role does sex play in my relationship with this person?

How do I feel about initiating sex? What are the ways I do

this?

How do I feel about being creative sexually? How do I share

this with my partner?

Quality recovery is based on achieving a balanced lifestyle.

Although sexual aspects of recovery are often minimized, the

recovering person must take responsibility for this part of life

as a sober person. Open discussion of sexual issues, fears,

and doubts is critical to the restoration of healthy sexuality.

CONCLUSION

Integrating a program of recovery for sexual growth and

development only adds to the quality of sobriety for the

recovering person. Reexamination of what is comfortable and

familiar in terms of sexual self-definition is a painful and

often unsettling task. However, ignoring the sexual side of

one’s self inhibits a person from achieving a true sense of

balance in recovery.

STAGE FIVE:

Achieving Sexual Equilibrium

This is the stage of sexual self-actualization. It involves the

ability to be comfortable with oneself as a male or female in

everyday interactions and activities as well as in a sexual rela

tionship. It requires self-acceptance and acceptance by others.

Quality recovery should include the ability to be spon

taneous in the expression of the feminine and masculine sides

of our personalities, and the ability to be intimate by giving

of our sexual selves.

The key question to consider during this stage is this:

How willing am I to continually reevaluate myself as a sexual

human being?

iS

19

directions for

slings are natural

-U hl

They ore to be our friends,

Not our foes.

To be listened to as cues, signals.

To be cherished

As a part of us.

DIRECTIONS

Black stamps — Fear

Purpose: The purpose of THE STAMP GAME is to help players to

better identify, clarify ana discuss feelings.

Orange stamps — Guilt

Green stamps — Embarrassment

Leader: THE STAMP GAME requires that one person act as a

facilitator and not participate in playing the game.

Yellow stamps — Any form of happiness, such as joy,

warmth, love, etc.

Light Brown stamps — Confusion

Because this is an emotionally-charged game, the facilitator

must be a warm, caring person, comfortable with his own

feelings and the feelings of others.

■ Flayers: The game can be played with the facilitator and one

to six players. Groups with up to forty participants can play by

dividing players into groups of five, while the facilitator moves

among the groups. Co-facilitators may assist. (See enclosed

ordering instructions for additional stamps.)

Time Frame: A group of six players will take approximately 60

•to 90 minutes to play the game. Allow 90 minutes if feedback

(see “Extended Play") is utilized. THE STAMP GAME may be

ongoing in that participants may play a portion of the game

during each session. (See "Variations").

White stamps — Any feeling not listed above that player

SWild Card)

wants to identify, e.g., lonely, helpless.

3.

Ask participants to remember what it was like when they

were young children and teenagers growing up in their

fa nily. Then instruct them to pick up stamps which repre

sent the feelings they had as youngsters and adolescents.

4.

Explain that the stamps represent feelings, whether or not

people in their family were aware of them having these

feelings. Participants should select a number of stamps

representing the intensify of each feeling. Example: If a par

ticipant experienced a great deai of anger, he might take

5 to 10 red-anger stamps, compared to feeling a small

amount of fear, where he might take 2 or 3 black-fear

stamps.

Results: Players will be able to relate more honestly to others

when they have learned to express feelings. Players will begin

to respond appropriately to situations when they become

more aware of their reelings. As a result, players will become

increasingly more effective problem solvers.

Let participants know that they may not immediately iden

tity with a particular feeling and they are not required to

pick up any particular stamp color(s).

Setting: Game con be played on a large table or the floor

(more fun).

TO BEGIN:

1.

2.

Players sit in a circle.

Facilitator places stamps in center of circle, in piles accord

ing to cc'or and explains which colors represent what

Red stamps — Any form of anger such as rage, frustration,

irritation, disgust, etc.

Blue stamps — Any form of sadness such as

disappointment, loss, etc.

(This process usually takes approximately 5-8 minutes).

5.

When all group members have selected their stamps, in

struct them to arrange the stamps, in an order beginning

with the feelings expressed the most as a child, to feelings

shown next to the most, to those shown the least. Example:

the person who knows that he hid his anger, yet found it

easier to show sadness might position his blue-sadness

stamp(s) before his red-anger stamp(s). The person who

was afraid and showed that fear will have his black-fear

stamps in front of his orange-guilt stamps if he seldom or

never showed guilt.

There is no one correct way to position stamps; arrange

ment is left up to each player.

-2-

Abbreviated Topics:

2.

Feedback is given only in the form of offering stamps. To

give feedback players (one at a time) take stamps from the

community pile. These stamps represent what feelings they

believe the sharing player has not identified. Participants

place those stamps in front of the player's stamps and brief

ly explain to player their perceptions, e.g. "This is more

anger. I feel that there is more anger with your mom, but it's

too scary to share", or "this is more fear, I don't know what

it's about, I just sense more fear." Instruct group members to"

be as specific as possible, but to limit comments to 2 or 3

sentences. When sharing goes beyond 2 or 3 sentences,

the person giving feedback may be analyzing or intellectualizing, and should be politely asked to stop.

3.

The sharing player listens without verbally responding.

There is no dialogue regarding feedback. While the person

receiving feedback is not responding verbally, he acknow

ledges (agrees and accepts) feedback by picking up new

stamps and bringing them into his pile.

Feedback cannot be rejected.

The player receiving feedback reflects his openness (a will

ingness to reflect and consider feedback) by leaving

stamp(s) in front of pile.

THE STAMP GAME can be used as an integral part of ongoing

individual sessions or groups.

Participant may be asked:

— Pick up stamps that represent feelings you had this week.

— Pick up stamps that represent feelings you had today.

— Pick up stamps that represent feelings you had at school.

— Pick up stamps that represent feelings you had with a

particular person.

_ pick • ’p stamps that represent feelings you would like to

discuss.

Or participants may be asked to associate feelings to specific

si.cations. Pick up stamps that represent how you feit when

(Give example)

Examples:

— When your mom said she was leaving,

■ — When your dad didn't come to see you.

— After you said ‘no’ to your son.

Treatment professionals may suggest that families use THE

STAMP GAME (Abbreviated Topic Section) as a part of family

meetings.

Facilitators are encouraged to use stamps in a variety of situa

tions.

4.

Extended Play:

It is suggested that if facilitator is working with a person or

group over a period of time, clients may play the game more

than once. Often it is played first without the feedback com

ponent. At a later time, feedback can be included.

Feedback can be a vital part of THE STAMP GAME. Let

members know that feedback is optional, not required. Time

and players' familiarity with each other are the key factors in

whether or not this aspect of the game should be included.

1.

Feedback cannot be rejected.

Since the purpose of the game is to assist participants in

identifying and expressing feelings, it is not permissible to

offer feedback which removes a feeling, i.e. removing

player's stamps. Many times participants, in their desire to

protect another from his or her painful feelings, inap

propriately offer yellow-happiness stamps during feed

back. In order to facilitate changing this pattern,

discourage giving yellow stamps during feedback.

5.

When feedback is completed, move to next participant.

6.

Complete this extended version with a self-image or self

reflection exercise.

Feedback is given after each individual has completed

sharing his feelings in adulthood. To give feedback, other

participants reflect on what feelings they think the partici

pant had or presently has that he did not identify or share.

-5-

-6-

htemataalDrag

Carrol Ftep®

Reducing Vulnerability to

HIV/AIDS

In Drug Abusing

Populations

(The Affected, The Afflicted

and Those “At Risk”)

Through A Community Wide

Response

Global Illicit Drug Trends: 2000

Amphetamine Type Stimulants

Drugs of the 21st century?

Following dramatic increases in ATS abuse in early 1990s, markets in

Western Europe and North America are showing encouraging signs of

stabilization or decline

Globally, however, illicit supply and demand are still showing upward trend

In East and Southeast Asia, illicit production, trafficking and abuse are

rising. The region seems to be emerging as a prime source for both ATS

end-products and their chemical precursors. The danger of spread to other

parts of the world remains.

GLOBAL SCENARIO

High-High Risk=HIV

1.

134 countries have reported HIV till 1999

2.

Of these, 114 countries have reported IDU with HIV

Almost all HIV has underlying alcohol or other drug use (UNDCPUNAIDS document: Drug Abuse & HIV/ATDS- a devastating

combination)

Study of 10 million IDUs worldwide shows;

-

IDU is 7-22% of all drug use

1 in 10 IDU has HIV

UNDCP RESPONSE

1.

As a UNAIDS Cosponsor, UNDCP aims to reduce the vulnerability of

young people by carrying out projects that promote a healthy life-style.

2.

Having easy access to health services, developing life skills and being

educated about the health risks that come with drug abuse are the keys to

staying drug free - and free of HIV.

3.

A supportive environment is crucial

The Strategy’

•

Target, reach and bring about behavior change in a critical mass of

vulnerable population

•

.Aim for absolute coverage to reduce vulnerability

•

Reduce vulnerability through behavior change and reduction of risk

taking behavior

•

Bring about behavior change through sustainable innovative

community based, managed processes/ interventions

•

Improve capacities of care givers to bring about behavior change &

to assess coverage

The Challenges

> Create an enabling environment

> Identify, address & ensure appropriate capacity building to change

behavior

> Improve, expand and network available services

> Ensure absolute coverage

> Reach all HIV-IDUs among IDUs and reach all IDUs among Drug

Abusers

> Ensure that a critical mass of IDUs reached, change practices &

reduce vulnerability

> Deal with the family issues & reduce vulnerability

> Target the “at risk” effectively, “Innovative IEC”

NEWS FROM THE REGION

(ASIA - PACIFIC)

•

Only 3 Asian countries have HIV rates over 1% among 15-49 years old Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar

•

However such low rates conceal huge numbers

•

Sex trade and use of illicit drugs are extensive

•

So is migration and mobility within and across borders.

Myanmar

Population

43 million

Government Figures

25000 HIV infected

World Bank

700 000 HIV infected

Growing sex trade and mounting use of intravenous drugs

Battle

Socio-cultural

Taboo against open discussion of

sexual health

Social stigma attached to

HIV/AIDS disease.

Yunan

•

7% sex workers inject drugs

• Amphetamines use in sex work settings is emerging rapidly in the region.

•

Emerging evidence of the role of other drugs including alcohol as a

Go-factor determining risk.

Northeastern Region - India

7 NE states constitute < 3% India’s total population but have

30% of country’s total IDU population (approx: 200, 000)

Manipur

First case of IIIV detected in 1989

HIV among IDUs > 75% in 1997

Non-injecting wives of male HIV positive IDUs - 45%

(late 1997).

Sentinel Surveillance ANC 1.69%, Blood donors 1.3%

Estimated Drug Users 15-20,000.

Sex Workers 1000

Total Population -1.8 million

The Scenario is comparable to Thailand whose ANC

1998 was 1.53%

& ■

A/"-'

.AC-Vvk. .

^cTiu'i7)fe_S <©£

L'.r:- iuered

Medical Services: v

❖

<•

❖

Doctor visits twice a week

Medications

Psychiatric consultations

Referrals/ testing

Therapeutic services: -

❖ Re-educative lectures

<• Activities

> Art therapy

> Therapeutic Games

> Energiser

❖ Group therapy

•> Individual counselling

❖ Follow up

❖ Home visits

❖ RPP (one month)

❖ Crisis intervention

❖ Family classes

❖ Marital counselling

v Counselling for children with specific problems

❖ HIV pre/ post counsel!ing

Extended services: -

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

❖

Yoga

Gym

AA / NA / Al-Anon Meetings

Bhajans

Sober Birthday celebrations

Vocational rehabilitation

Special programmes for recovering addicts

Community awareness programme

ACC anniversary celebrations

Celebrations of religious festivals

Programmes for trainees

<C

■

C£aj7£<

Supportive Features: ♦> Staff development programmes

❖ Weekly staff review meeting

Monthly ACC review meeting

❖ Documentation

<♦ Networking with other institutions

❖ Mobilising support groups

COMMUNITY MEETINGS

s programme starts with the community meetings.

used as a methodology to imparl value based thoughts.

RE-EDUCATIVE LECTURES

Disease Aspect

Disease concept

V Denial

J Dry drunk

J Relapse/warning signs

'z Psycho social factors. >

J Children of addicts and family violence

v Over coming grief

V Developmental task

J Powerlessness

J Human needs

J Surrender Vs compliance

J Emotional cost of dependency

J

Personality development

Assertiveness

Anger

Negative I positive feelings

Personality defects

Improving quality of life

J Self esteem

V Value

'C Hurt feelings

J

■/

V

V

v'

Recovery

V Problems in sobriety

V Facing challenge in life

V Building relationship

Medical issues

v'

v'

'■

Medical complications

Smoking

HIV/AIDS

Sexual problems

Coping: skills

✓

v'

v

Work Ethics

Financial Management

Time Management

Stress Management

Communication

•2 ■ reduction to AA

Steps of AA

Making amends

Resentments

Spirituality

Serenity prayer

J Slogans

J

/

/

<

''

' \ c V 'I..''

GROUP THERAPY IjgSiWES

/ Powerlessness

•/ Damages

/ Worst Drinking/ drug taking episode

S Insane And Aggressive behaviour

•/ Positive/ negative qualities

■/ Pleasure Vs pain

■/ Developmental stage

■/ Myths and misconceptions

✓ Tools of recovery

✓ Future risk situations

ACTIVITIES

Art Therapy

''

✓

'z

Problems in sobriety

Group art

Recovery tool box

1-ears

i aside Outside

Beauties in life

Therapeutic activities

Memory game - Ice call

- Anthakshri

- By default

flay modeling

Life skills activities

nmttnication

>

>

>

>

>

Dumb Charades

Guess what’s the good word

Chalk game

Trust walk

Pictionary

Self Esteem

>

>

>

>

>

>

Positive Strokes

Talents time

Tournaments

Self Esteem Envelope

Animals and Good points

Personal skills

Assertiveness

> Debates

Il

MH' '2-L. 3)

•AN

IDEAL ACTION

GENERATE

ENERGY

1.

Mind surrenders to Self

2.

Intellect fixed in Self

3.

Body active

AVOID DISSIPATION

1.

Anxiety for results of the future

2.

Worries of the past

3.

Excitement over the present

CONCENTRATION

Intellect directs mind to chosen action

CONSISTENCY

Intellect directs all actions to chosen ideal

o

CONTROL DESIRE AND EGO

DESIRE

Is the flow of thoughts towards an object or being

for fulfilling an unfulfilment felt within oneself.

MODIFICATIONS OF DESIRE

Desires fulfilled leads to greed (lobha), delusion (moha),

arrogance (mada), envy (matsarya) and fear (bhaya).

Desires interrupted give rise to anger (krodha).

EGO

Arises out of a feeling of :

I am supreme.

I only exist.

I am the doer.

Ego hurt gives rise to anger.

DESIRE/EGO

Causes mental agitations and inefficiency atwork.

INTELLECT

To reach the goals set by you, you need to make the

existing intellect available to you and also to develop

it. The intellect is made available through a process

called introspection. To develop the intellect further

you need to study and reflect upon Vedanta It is

available in the form of a book entitled "Vedanta Treatise".

GOALS TO ACHIEVE

1.

INDEPENDENCE

Examine the life of a plant, an animal and a human

being. The plant is most dependent while the human

is designed to be the least dependent on the world.

But man today is largely dependent upon the amenities

and facilities, the environment and circumstances of the

world You must shed this dependence, become wholly

self-sufficient and thus regain the dignity of a human

being.

2.

3.

HAPPINESS

It is the bliss of self-realisation. It is infinite, absolute

in quality and quantity. Once you enjoy the bliss of

the self within, the greatest joys of the body, mind and

intellect mean nothing to you. These joys are like the

waters entering the ocean.

KNOWLEDGE

Ignorance of Self projects this world. All the knowledges

acquired in this world are in the realm of ignorance

vis-a-vis the absolute knowledge of Self. The

knowledge of Self is pure knowledge compared to the

conditioned knowledges acquired in this world.

4.

LOVE

True love is universal, even, same to one and all. Love

in the purest form is everywhere, nowhere in

particular. It is regardless of caste, creed, colour,

community or country. It has no fixed location. It is

not concentrated in one form, it is realising oneness

with the world.

5.

POWER/STRENGTH

If you are selfish and egocentric in life, your power is

limited. Your actions are poor. Drop your selfishness

and ego, turn selfless you command real power and

strength. You become dynamic.

FUNDAMENTAL VALUES OF LIFE

1.

ACTION

Action is the insignia of life. Inaction is decay, death. ■

The first lesson in personality development is therefore

to be active.

2.

DIRECTION

What are you working for? What is the purpose of your

living? What is the mission of your life? Reflect on

these ideas. Fix an ideal, a goal, a cause for your

living. Let your actions be directed to that ideal.

3.

OBJECTIVITY

Is maintaining an impersonal attitude in life. Opposite

of being involved and entangled in the affairs of the

world. Look at the world as you would a picture on

the wall. Function in the world like an actor on the

stage.

4.

SENSE-CONTROL

Indiscriminate indulgence in sensual pleasures results in

the destruction of your personality. The senses are very

powerful. They distract you from your chosen path and

you lose your goal in life. Your intellect must keep

your senses under perfect control. Be a master and not

a slave to your senses. Besides losing your goal you

ultimately lose the very pleasure of the senses if you,

lack control over them.

5.

DUTIES, NO RIGHTS

The dignity of the human race is founded upon the

principle of obligatory duties, not rights. Develop the

art of giving, not taking. You have no right to claim

anything as yours. Your only right in the world is to

give, serve the society.

6.

CONSISTENCY

Having fixed a goal in life let all your actions flow

towards that particular goal. Keep your priorities clear

and use your sense of proportion and maintain the

consistency of purpose till you achieve the goal that

you have set for your life.

Dear reader,

This manual has been produced as one in a set of four manuals on:

Addiction Rehabilitation Programming; Community Action Against Drugs and

Alcohol; Drug and Alcohol Policy Development; Design, Implementation and

Management of Alcohol and Drug Programmes at the Workplace. The material

is first of all designed for use by the resource centres on drugs and

alcohol, under development in Southern Africa with support from the

Norwegian-funded ILO project RAF/89/MO5/NOR, "Establishment of resource

centres for rehabilitation, workplace initiatives and community action on

drugs and alcohol".

However, we hope that these manuals which are of a

rather universal nature will also be useful to other practitioners

concerned with the reduction of drug and alcohol problems anywhere in the

world.

Please note that this first version of the manuals is presented in

draft form. The manuals have been designed in such a way as to allow easy

additions, adaptations and modifications.

We would like to invite

comments and suggestions on how to improve the content as well as the

presentation of these manuals. Ideas and additional elements, especially

copies of case studies for inclusion, would be most welcome. It is our

intention to collect such comments and feedback for a period of at least

one year and then commence the revision of the manuals. A register of all

those who have received copies of any of the manuals will be maintained

for the purposes of periodic mailings of elements for insertion and

eventual distribution of the revised version.

I take this opportunity to thank you in advance for your interest and

contributions.

Geneva, April 1992.

Yours sincerely,

Jon Wigum Dahl

Project Coordinator,

Vocational Rehabilitation Branch,

International Labour Office,

CH - 1211 Geneva 22,

Switzerland

9

•

Facilitating growth

The counsellor should never forget that her involvement is of prime importance

in shaping the group norms. Too exacting behaviour or being too passive can

both inhibit members. She needs to play her role with confidence and poise.

Basic rules that are set at the start of the group process may sometimes need

further strengthening. The counsellor can draw attention to die norms through

statements, observations, questions and display of appropriate non-verbal

behaviour. For example, to encourage member to member communication, the

following methods can be used:

-

Asking for the other members' reactions

Refusing to answer questions directly

Nodding, smiling, good attending behaviour and verbal reinforcements help

shape positive behaviour. The counsellor choosing not to react to low tone

conversations, late coming etc, will be noticed by members of the group. Not

attending to these can even be seen as non-caring. Unhealthy practices like

frequent interruptions or excessive criticism can grow on quickly and it is the

counsellor's responsibility to guard against them.

The counsellor should encourage feed back. When a member is criticised or

confronted, caring questions like, "How do you feel about what was just said?",

helps that member respond. When many suggestions or comments have been

made in response to one member's sharing, asking him, "What did you find most

helpful? How did you feel to receive so much?", helps members give appropriate

feed back.

The counsellor is a "model setting participant" in many ways. Displaying good

attending behaviour is quickly copied by the members. By giving support and

encouragement, the counsellor invites members to follow suit. The counsellor's

handling of conflicts by permitting expression of negative feelings and working

through them rather than suppressing them, helps members learn to do the same

even in real life situations.

•

Recognising the Group's Power

The primary therapeutic agent in a group is always the interaction between the

members and not die counsellor. As an effective counsellor, she recognises that

the group's power is more than her own and makes the group assume

responsibility to make the interactions. If the counsellor takes the responsibility,

the members would sit back and wait for the counsellor to make the interventions

as if watching a movie.

The counsellor needs to resist the urge to quickly intervene with the right

answers, and should wait for a discussion to follow and allow it to slowly steer to

a conclusion. The group values the decisions that they arrive at and does not look

for quick fix answers from the counsellor even if the solutions are just as, if hot

more effective.

10

Recording

The progress or lack of it among each member in the group and the counsellor's

impressions need to be recorded. This will help the treatment professional to see and

clarify the level of progress and plan further directions of progress. In case a

different counsellor takes over, she will be able to

-

assess the progress of each member

set specific goals for each member

identify- and help him plan to deal with negative factors so that they don't grow

stronger and interfere with the recovery process.

use those facts to give appropriate feedback to members.

Recording is thus extremely useful and clearly necessary. But for the "time-pressed"

counsellor, if recording needs a lot of time, it can become stressful and poor

compliance will result. To prevent this, recording should be structured, and carefully

structured recording will not take more than 10 minutes.

If 5 sessions are held in a week, a weekly recording will suffice. If the session is

once a week, recording can be done immediately. Group therapy initiated changes

may continue in-between these sessions also. Recording helps the counsellor keep

tabs on the issues discussed and maintain continuity between sessions.

The ultimate goal of group therapy is to aid self understanding and initiate change to

the maximum level possible in each and every member of the group. Three factors

contribute to this outcome.

1.

2.

3.

The skill of the counsellor.

The openness of the members who constitute the group

The (genuine) interaction between the members.

Therefore, the skill of the counsellor needs to be sharpened .periodically through

frequent self-assessment, clinical reviews with peers, openness to new techniques

and readiness to explore in directions suggested by group therapy research studies.

Tire counsellor has some control over the second factor also in the sense that through

a display of supportive care and concern, she can facilitate the group to become open

and honest in their sharing. This will lead to genuine "feeling level" interaction and

conflict resolution. To put it plainly, the counsellor even though a catalyst, is the key

player and her skill is of prime importance.

21.12iT3.biuays

i im

i

of sFct Influence

1

I 65.3%

| ACUlt

[ 69.2%

M-’C-P

I

I

I

|

I 1Q

I = . on,

I

I

I Unsuoervised

I 72.1%

I -------I 31.0%

I img inrofiTiauun

| UO.O7U

j

|

j Jobs

I

u.8%

Coping strateges and skills

To deal with a wide rance of dressers likely to be encountered in everyday life, the individual

reouires to acouire a wide range of coping and social skills. They may be cognitive or behavioural

Cogiitive skills- self assurance, cognitive restructuring cognitive detraction, self control etc.

Beha^cral skills - problem solving action throuc^r negotiation / compromise, withdrawal throuc^

*.

leaving^ avddng the dtuation, communication drills, assertiveness, social networking far)g^grt0 in

alternate activities relaxation

Practical performance skins and Survival skiiis ('Ahi ch may be considered :!aberranr in the wider

cun 11 m nuy; —eg. ng nriy run ni y iaai, reacting quickiy, weaii lerii ig physical harm etc. may ba very

•JSP C^’.’OS

9 noninfi efratpfar Th<=i rretinrih/ nf th® dTUG US?HO Child!r6in StUCf^jd hAd '/BP/ DOOT

adatxive cooing skills.

I /'ciaptiver Pro-social (%)

1 coping strategies and skiiis

1 Maj adaptive//inti social (%)

j xjcriPrsi v-sip.r.y Suq;c9>cs

I 88. r

. i31-3

1 Deai'nc with sadness

I 64 1

1 35 9

1 Dealing wim anger

| 65.5

I 59.a

| 34.5

1 ^n ■?

1

- --------- -------------

High Risk Behaviour

One of the major realizations from the study was that d ug use i abuse couid not be viewed in

isaaticri. m ug use iri child'ei ; for med just one of the many elements which cunti ibuted to tneir r.g'i

|

i

|

Delinquency and Criminal behaviour

7S% of the children interviewed had self reported Delinquent behaviour. This included ctcarincj,

rapes and self cirected agression. The delinquent behaviour p^ccfcrrsncntly' occurred in the

context of the peer gang (70.3%) but a significant prooortion of the decant behawour was

solitary.

Age inappropriate sexual behavior

Aoour hair ipr/oi of ihe children who were specifically assessed reported being sexuaiiy active.

ip<4

r«*y fry ermfry* \*4th ry=,-?rc' <=• sicnificsntlv taros nurW*s?,r of children r^QLitarlv Msitsd

crrrvnArnial sex workers

Thgrp

p nexus

street children end locel conmerciaJ sex workers. rrvanv of whom

abused alcohol and drugs. Children frequently acted as pimps or go — betweens in exchange for

money, crugs, sneiter or sexual fawurs.

The SESGJsIly setive children, hy end Jsrcje, reported having sex in intoxicated states and not usng

terrier contraception, despite knowledge of condom use and the potential for HIV and other

infection. Intoxication made them careless or daring. The other attributions for not taking

precautions were that they couiart care less, or that they dd not think it couid nappen to them.

cf beingsexually active[Pearson's correlation coefficient 11.003, cff=1, p= 0.00091] am.

33.40

ff-^sstrsoris

I 1 Had more druq use (71% vs 34%: 02=72.98. df=2: p=0.00001)

j 2. were uiqci i, i 5[iij vs 2»j|,i4j. i=u.*to. p=u.uu5;

’ 3 u?d t?-?

vs'f'G ^eers 'innsi

yre? f=2

7=9

! 4. Had lower education (1(31 vs 3(31: t=3.81: o=O.

* 6. Earned rnore ^Ps.42r20ivsRs 33(31]: t=2.2: p=0.029)

0.000001

KJCMCl dl Dcaiui

r'56%)? 2. Headache (41%): 3 Sfnrnach problems (29%): 4. Feyer and bodyache (28%): 5.

Toothache (27%): 6. Skin problems (26%): 7. Burning sensation while passing urine / sores on

genitaiia (15%); 8. Tinging ana numbness of hands & feet (10%) and 9. Accidental injuries to

iXXjy cd'iCi liD'OS \ tW'/oj.

ThG use of solution was significantly related to occurrence of Tiro1’re

* and

^possible

peripheral neuritis) [Fisher’s Exact Test- p= 0.003]. possible S.T.D.s (Burning sensation while

passnq urine / sores on genitalia) [ Pearson's - 8.4. df=1. p= 0.0002]. stomach problems [

Pearson s —14.6, df= 1, p= O.uuOlj and neadache [ Pearson s—4.5, df= 1, p= 0.03],

qoz.

Deliberate self-harm and self-mutilation

6eif muniauon , specincairy scan n can on and siashingtnemseiveswilh sharp oqects, especially

had an anaesthetic effect.

Some cniicren reported incidents wien other chiicren kiiied themsebes by fiingng tnemseives

Gender and Drug Abuse

Tne data regarcing gri chiicren is much more sketchy. This is partly because most of the

pejj iicipdui'iy organisations in the study' had a greater street preserice amctfig trie ixys. Aso ooys

oUnumbcr grls on the street This is not to detract tan the feet that a significantly large lumber of

gd oh’ld'en fend up r*^

the

rnn<~K5 Af.hich often jnnh irfe mo cr h

*n

Fr^m key informants via? learnt that the of rls stav in their o.m

«ma.ll hws). some of the grls enter into informal "marriages?1

25

with some of the dder tors while ethers are gven shelter bv various adults Almost invariably these

gri criicren are suqect to physical ana sexua abuse. A large proportion are engagea in commercial

&ca vvut k. vvi i«j its wimfiyiy ot ui iwtiiingly. Ti ie use of aicohoi and ini taiai it u uys is. w,i y I iiy i ai i kji ig

rv ri; nf

cvicienr-c. haMnn i m

iobs or establish’no marrieoes and ferries. and seme of the

older hovsdo. Thecirls reportedly have no such choice. Sickness ill health (phyacal and emotional

) are high. Some gris die as a consequence of illegal abortions, most others due to a combination

of pool null ilia i ai id excessive drug use.

Access to resources affects a chilcfs ability to learn drills, change attitudes and perceptions,

decrease some of the stresses.

The chiicren studea had very iittie access to neaitn care education, age appropriate leisure activity.

AJciiiui laliy ti iey were naiui aiiy suspicious of the very structures that the State has erected to take

2

hosr'sjt^i” rathe

**

than having to go to the Juvenile j-iome.

^rrcs^ a? the children ^meve then 90%) h^d been been abused, vidated and evrdc4ed l*w ooheernen

at some time in their short lives and understandably wanted to have nothing to do with the Police.

Vvith respect to Health Services it was quite ciear that tne chiicren:

i.

O ilm utilized ti iw tAibtu ig siaie ii i&tiilieu i icfcuih btiMuei, couiu i id aiiuiu pi iVaile ii kajUc* uait; al iu

Most of th?? can no

ha'jrv’ been dsM^ooedh^ adults for adults rareh? reennnized issues of

chilcten nor dd they accommocfete the valid needs of the chikten. Health and welfare agencies (esp.

Governmental) nave nxea rules ana acmssion criteria which exclude unaccompanied minors from

tiitai

viutsb. t<_zi iiiua ta i n ivuivcun I ciLRd i cui auilMiies ae pJQiiy ui iuca^luoj py i i sai I8u ts-a 11

Childrsn mistrust

values and alien *?

^hsmse^.

dement

vltA^S,

ssrvicss. Addoscsnt childksn tend to reject adjlt

more w’th their Deers, so that it is dfficult for them to submit

themselves to a health care system controlled try adults.

2.

Tlie childen on theii pail rarefy identified health as a maju concern. They often regarded

themselves as invulnerable, focused cn the here and new and not on long term consequences. Their

mor^nalt^tion frcm.tho rest of sccieh-' reinforces the bdiefthst no one cares - the present is s!l they

have to look forward toj

The reluctance to seek helo may also stem from the fear that acfrnittinq to illness miqht make them

afferent rrom peers or cause employers to look for healthier employees,

72.2% of ilie children assessed wanted to stop their drug use but51.S% wanted nothing to do

with establishment structures.

3.

Chiicten also lack informcticn abo< it exiting resources and often pick uo misieadino or erroneous

information. This is a function of what information they trust and who they trust as information

providers. For example 95% of tne chiicren assessed in the Bangalore study had picked up their

iilicii d ugs sdoy u u 11 ii leil peet S. Tl lis is I efiwuied in ii ieii I teip seeking choices.

al icwieuye ai.

jji

*

.-ni vwhm • v zu vt ci’iC viiuCii vii mid vvotii>vM iO Stvp i.i'iCn' di Uy U3C, Scud toCy’ 5’«cid mCVCT tf’iCG tO

Advice and treatment related to Drua Abuse

Avajiaanry

mu FJiJ. pdi us ui u it; utx.ii in yH lei t; cii t; p Ln/uap is im duviue di id u eati I ra ii i tacUtXj’ lO Di uy Abuse.

Oraan’z?t

*ons

(fijnded in laroE? n-ypassjre hv th4? Mnistrv of Social WeKsre).

Access billtv

iviost of these organizations oo net acmit, nor provide care to chiicren. On the other hand, most of

the organizations dealing with children and especially street children are acutely aware of the

Specificity

Furthermore, most of the chug de-addetion centres deal specifically with the treatment of drug abuse

ano some are only centres for detoxification. And going by currently available information, none of

ilie cks-aiiiciion ceiities have u eain ei ii and rei laLiiiitiiui i piogain i fcss iakxed to tile i equi fci i lei its

ios° infwssQr

soyt pnri concentrate their efforts in gettino ha^k onto the streets where they

retaose auicktv.

treatment metea

ca uu ei i cm i hied ii t sui i uui idi igs dui I h laied by adults Will 11iisiCr ies Oi u ug aouse ai io

Referral throuch the r^t.^rnn^nrpi .qudrprns (Juwenile Justice Act)

At ieast in Karnataka and specifically in the citv of Bangalore. cfruq usina chilrten are hardv ever

referred under me provisions or tne juvenile justice Act to ue-aodction centres for treatment.

v vi ufe uctia li ut i : Juvei me rxi i

on frhc. <3TA»=t-=: Affocfrb.v~&/

i icx rfveuidi^'e cit u le lii i k; oi" v.i iiii iy. it it> li ic e/djrn ieiice ui

tn <=£ax/ ojtsde th1? ambit of th

* 3 Gn^^nrrwantai .h Men’!© care

systems. Aid it is these children v.ho are at Greatest risk for drug abuse delinquency and sexual

higi risk oenaviour. Paradoxically, it is this group of children who are in geatest need of

intervention that the organs of tl ie Juvenile Justice Act manage to overlock.

Referral thro roh the !cn Gcy-.'ernrnenta! Systems

It is then left to the N.G.O nehA.ork of chilcken’s agencies'Ahich maintain contact wth the

affected chilcfren and get some of them to care facilities.

Thougi the prodem of street cniicren is net realty nan they nave oy and large been ignored oy

policy i uakers and were fa a faiy iime suusui i ssd ui idd die rubric oi working umfaen ". oiitfa.

welfare and in 1993 introduced a orant-in-aid scheme for N.QOs working with street children.

vvniie most or tnese n.u.U's have an effective street presence the/ are usually CMarw.neimea Dy

rpfprrai

ifoc; tn th#=> H©-ackfchon se

vces

*

in th© reacn.

Netvuork 8c Outreach

A i effective way of L/ypa^i iy these difficulties is to fm ni broad < letv-jm ks 01 oi ganizatiof is offering

different setMces. Erug abuse is a cempfex heterogenous prcbfaii and is the concern of nut only

the specialist in addiction medcine but a'so impinges cn the concerns of a variety of

professionalsv'.orkinci in other areas. Those'Acrkina in the areas of Inroad community

develoomenial work as well as those werkinq wth wemer. and chikfen are likelv to come ud

against a ug acuse reared problems as impedments in tne smooth running or tneir progammes.

Netwjrks prodde tlie pcteitiai fa abroade range of iriterveitiei at lows cost, aixoackn

In addition to lona-standng concerns aver the deleterious health, lead. and pharmacdodcal effects

or sunstance anuse, new urgency now exists for tne oewefopment of effective intervention strateges

it I it« u dt la i laaot i of duquii ed it 111 Hi luusiiuia iuy

'.jf ui uw pciytxi uy n jtf ctv« iuu^» u trj

I'-ri-.-.-3-b5rirc h/r<ral|v r.-ry’j u-p

rnode^t results anH

treatment pains are often lost due to hi<±i rates of relapse.

r: tf.ft!(j i un«s a

dturi ricuiv^ io ucaiiny ii iu\iuuais aftts they nave deveiofjed such an

Prevention strategies: Possible Interventions

to the

*=nt«rn

^6^

^fFrrts

has been concetiualized in terms of suoptv and demand reduction models and as primary,

.ention. tach encompasses a afferent aspect of prevention, ana nas

enforcement aoendes. ceitic'darY with respect to the irterdction of duos bv governmental agencies

;-.rtments. Demana reductioTi efforts, on the otner hand, are conceptuajized as

Supply Reduction

The NDPS Act which regulates Drug Policy in India has a number of defects. To Start with it

drects its attention to the lesser of tne harms. All ever the world, as in Inda, there are

say lifica; illy mm e deaths associated with tl le use of aicohtjj ai id tobacco than tliet e ai e illegal

drug users. Yet the NDPS ".ct focuses cs«clusivety on the illegal efrugs.

..r-vrf.H/--’ '> '

. .r.!

-h .Ter "H-,-? r; imr.i-v-

r-rirv-i'H'nJ r

ir-v? £ho USO CSstflblijOn cLn.d rTSn.’jfect’jrC? Of

j<- eAT1*' 5'??tion. i o to n^ke

ileoal cfruos especially ilScit narcotics

*? rv unr-rtk’d-?. Failinc that to certain dug use by increasing the social econcmic and opportunity

tc

costs of usng ixiying and selling illicit dugs. in effect, this ensures limited availability at sewereiy

Leoa ocntrcss used to Gupprcus die u^.;i of selected drugs produce unai'iLicipcitcd

igrcicd)

the acidtional costs of ociicing this subterranean economy falls on the tax payer.

2.

F

Legal markets in analogous substances (legal dugs) are protected.

i ; ■. -u.. v

i;.i uvu-'i e is ii Mue li'njie iikeiy.

'"i

•“ r c r - c’cc

•/

• • r.r -

irp rv»rs»r5f'--c< - h •ftafpvw-w onr! i&riji-stfirjn X^-r^JS

nv '< • c’ fc-nocrs ana costs of process ng ana pro^ctrcicn are escalated.

fi.-c. r.< . r ,• .-'I 'i

nr- !r >rqr rJ Qf scien^!^r

S? <Ch < leoal

i!!eoa!

classification. Recreational it. : :d - alia iiiq d ugs need to be rationally classified accordng to their

addeuve potential and icncj term neam rratc in such a dassfi cation, cigardtes are the most harmful

c.; li’ic Ltcau of ij r..i;

if. '• cs id ii"rii <-i';dicy to cause laigte in ham not oily to the user

?:«ccoc':> e^’caticria’ ryocran" of modest trooortions and some restrictions on smoking

In G

li. s^iificant reductions in alcohol related liver

“.G- :.i.

cfrtaK ctstns nav- ?? -r,' ~ r ■ ■ -

r.-... limiting

siity ana controlling price to favour

,c

’H 91.T‘tl 'deS'A^SCh

31 H

' ’

A'A.:; : A. cucfthe infon-naUondscrirrination

••. *:i -■• "c r,-;

passive recipients or factual

Lisi SAk-c.' L'.-c'7.jr,73 invoke

■'

■ ’ ■ a~

■’.... and

Chapter in Textbook: Curriculum for IAS Staff College

Children with a Substance Abuse Problem

Vivek Senegal, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry,

wi ivicnidi J Jgm.LL .

> nt and juvenile < ' •».

iot ii'

u>o uie longer-range

r.r.v NimdrnmA()■,i jS> violent crimes

unemoiwment. 'those problems carry costs in lost proiictivitv. '

...enmyui me ooncis mat i iuu society luyetii^. zxivaxmiiu >*MMy

'

'

'■

i ■ ? fr-n

- -Mid a

mi tne social cost due to alcohol abuse in

Karnataka conservatively estimated the cost due to reduced industrial productivity caused by aicohai related

-<--—*--4 ---------- 1

to

approximaiely Rs. 691 crores per year (Senegal, 1988).

' ‘r=dwith cfriin ahnssrt<M„.,nr>nt is that while many effective strategies exist

ThecM?-

iiiu aoainence, long term maintenance oi ausunenue ^-.avuiang t elapse is a greatei w^all

challenge.

A Crit;c-i

Art '

'

'

-i

Transition

'.->1 starts vtaretta mater tncus is m ctpvpinnng seif-identity, a nhf'spwhich is

marked by cframatic cnanges ana re-adustments. This results in nav stresses and anxieties, wtnich

characteristically increases vulnerability to peer pressure. This is also a stage for practicing new roles. From

early childiood, youngsters practice adut rdes, throu^i pretend play. During adolescence this drifts to actual

behaviour. After 10 years of age the pre-adolescent beg ns experimenting with a range of new "adult"

behaviours, and for many child-on, regardess of culture and throuc^iout the world, cigarettes, alcohol and

other d-ugs have become a normal part of coming of age.

The social task of adolescence is increasing autonomy from parents and a ccrrespondng increase in reliance

on peers for validation and drection. Conformity to the peer g-oup increases rapidy during pre and early

adolescence when it peaks and then gadualiy declines. Adolescents typically assess themselves and their

behaviours through the reactions of their peers; acceptance by peers is critically important and more than

at any ether age, rejection can be devastating.

This is also the final stage of intellectual development. There is a shift from concrete operational thinking to

formal cperaionai or abstract thinking which is much more fiexibie. Vvhiie'on the one hand this sophisticated

reasoning capability allows the adolescent to think hypothetically and deal with proposition and theory, this

also invariably results in tensions and confrontations with authority figures and institutions. Adolescents are

able to begn que^ioning rules that had previously been taken for granted and this is also a period when

alternative life styles are considered or experienced.

Risk taking increases during adolescence. Exploring any new behaviour, naturally involves risk taking but

adolescents also appear to engage in risk taking just for the exhilaration of the dare. Adolescents also want

to impress their peers but are not yei. adept at assessing risks. They frequently assume that if they engage

in any behaviour several times without negative consequences the perceived risk goes down.

There is also thetenctency to exaggerate based cn imredate experience, which allows risksto be minimized.

Adolescents have a sense of ‘invulnerability’ - an attitude that "it went happen to me”. Since adolescent

tnougrt is mere anchored in the here and now/ than is adur thougnt, they are iess concerned with the far off

future Given their immedate time orientation, tine immedate gratification of need, for example the satisfying

and pleasurable short term effects of smoking may outweigh the potential longer-term negative health

consequences.

Aso some risks may seem more immedate than others. The risk of losng status with peers, being rejected

or ridculed or thoucht immature or inexperienced may seem more dangerous or aversive than the possible

risks of taking a drink or accepting the offer to take some ether dug.

Adolescent Drug Abuse :

Is defined as the frequent use of alcohol or other dugs during the teenage years or the use of dcohd ar other

dugs in a manner that is associated with problems cr dysfunction. This definition reflects the recognition that

a relatively large number of teenagers try alcchd and other dugs without becoming involved in the frequent

use of those substances or developing dug related problems.

Because of the rapid changes they are ©periendng adolescents are at risk for developing sdcstance abuse

more quickly than are adults. The initiation of subdance use and early stages of abuse have their root in

adolescence althouch the patterns that are characteristic of adult substance abusers are relatively rare in

adolescents. The precise point along the use/abuse continuum at which use becomes abuse is arbitrary.

Criteria for substance abuse involve a) a pathologcal pattern of use, b) impairment of functioning in work and

social relationships, c) physical and emotional deficits.

To wait to intervene until this point with the adolescent would be irresponsible. There is no widely accepted

consensus as to when substance becomes abuse, and for chilcten and adolescents - especially young