DOCTORS FORUM

Item

- Title

- DOCTORS FORUM

- extracted text

-

RF_MP_8_SUDHA

Jan. - Mar.

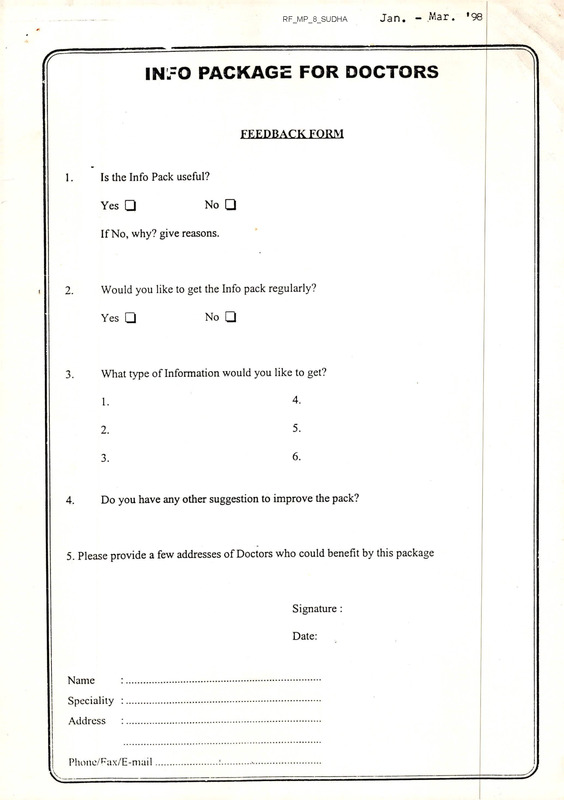

IN-=O PACKAGE FOR DOCTORS

FEEDBACK FORM

1.

Is the Info Pack useful?

Yes

No

If No, why? give reasons.

I

2.

Would you like to get the Info pack regularly?

Yes

3.

4.

No

What type of Information would you like to get?

1.

4.

2.

5.

3.

6.

Do you have any other suggestion to improve the pack?

5. Please provide a few addresses of Doctors who could benefit by this package

Signature :

Date:

Name

Speciality :

Address

Phone/Rix/E-mail

’98

SeptewbeJi, 1997

INTRODUCTION TO DOCTORS FORUM

■ 'J

I

/

’Re idea o(j (jOJi&ting a DOCTORS jyoUUM iit cV<bb4[ is gaiitiitg ivtoutc-ittim siitce

1996.

/

’Re pujtpose o(j de docto/is ^Jo/LUnt is to build up) cut ac.tioe K&twoxfe o(j sociaWy

in iJeahR. Oa/ie to cohte togeden to

conscious Docto/is, wHo a/ie open to new ideas

i

sHaxe ideas and expe/iiences.

'

tybl/r would like to build up and suppo/it a p/io|jessioiial gnoup o(y Docto/is wRo

could dink and act alteJinatiaely to p/ioiride national 4deald Oane, wHe/ie people

a/ie giilen p/iinte impo/itance. Special emphasis would be giiren to de a/iea 05 pneUentiUe

and p/ioivtotiUe Public d^ealtd cane.

Docto/is 2?o/iuivt is planning to take up de (jollowing initiatives.-

❖ 7b provide a platjjOKM. (yon de Doctons to silane tHein Views neganding tHein

pnofression and de bunning Heald issues o(y de countny.

❖

To send rn|jonM.ation Packages (yonDoctons as a pant o(y continuing medical education

especially (yon doctons wonking in nemote aneas.

❖

To debate and discuss about vanious RealtR policies and technologies emenging in

India and pnovide altennate suggestions.

❖

To collabonate witR the existing netwonk like rpD4. O^MDlF, MjJO'. etc. and

wonk togetRen fron a common cause.

In sRont, Doctons ^Jonum is a pnoactive and (jutunistic gnoup feon Doctons wRo could be

in de (yonefynont to take up RealtR issues and (yind solutions to public RealtR pnoblems in

India.

>ls a (yiJist step we a/ie seitdiitg you de (yi/ist [A&O

a pa/it o() cowtiituiug wedicaf. education.

4

DOO-TOlQS as

Kindly (jill in de (jeedbacfe fro/iM. and send you/t cohwents and suggestions.

"Ranking you in anticipation.

QAbl/I ^J/iiends

\

\\

\\

\\

\

73

■J

—

tk /cr-i^l /9/2s/ S rr

Pr'S

t>JcS

P

Co

sPjOljJcJL

______________ s' l i

K■cm

(i

Li'l

c^LiS'O

J

■!

INFO PACKAGE FOR DOCTORS

FEEDBACK FORM

1.

Is the Info Pack useful?

Yes

No

If No, why? give reasons.

2.

Would you like to get the Info pack regularly?

Yes

3.

4.

No

What type of Information would you like to get?

1.

4.

2.

5.

3.

6.

Do you have any other suggestion to improve the pack?

5. Please provide a few addresses of Doctors who could benefit by this package

Signature :

Date:

Name

Speciality

Address

Phone/Fax/E-mai 1

“INFO PACKAGE FOR DOCTORS”

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION TO DOCTORS FORUM

1.

LEAD ARTICLE:

The Scourge of Hepatitis - B

2.

NEW DRUGS/VACCINES:

WHO Announces Influenza Vaccine Formula - 1996 - 97

3.

LEGISLATION

Important Information for prescribers

4.

WOMEN DOCTORS WING:

Formation of IMA service/Women Doctors Wing

5.

ETHICS

The Doctor’s dilemma - social-Ethical issues related to AIDS.

6.

DECLARATIONS

Declaration of Standing committee of Doctors of the EC

7.

FACTS AND FIGURES

50 facts from the Regional Health Report 1996, WHO - SEARO

8.

BREASTFEEDING NATURE’S WAY

Baby friendly hospitals.

FEEDBACK QUESTIONNAIRE

/

€11}

THE SCOURGE OF HEPATITIS B

The occurrence of Jaundice has been known

for centuries but it is only in this century that

the various causes of jaundice have been

described. The rapid strides in medical

technology have led to elucidation of the

various types of jaundice. Previously we used

to classify jaundice into two categories medical jaundice and surgical jaundice, the

former implying a medical cause for the

jaundice which required no surgical treatment

and the later implying the need for some

surgical intervention for relieving the jaundice.

The commonest cause of medical jaundice is

viral hepatitis. The term has two facets a)

viral implying that it is caused by a virus and

b) hepatitis implying

that there is

inflammation of the liver. Viral hepatitis can

be either acute or chronic. Acute means a

process which is recent and chronic implies

that the hepatitis is more than 6 months

duration. Although a variety of viruses may

cause a hepatitis like illness, five well

characterized hepatotrophic virsuses, A to E,

are the most important causes of acute and

chronic viral hepatitis. These five viruses can

be divided into two major groups. The first

group consists of viruses that are feco-orally

transmitted and don't cause chronic hepatitis

i.e Hepatitis A & E, and the second group

consists of those viruses that are transmitted

through blood and can cause chronic hepatitis

i.e Hepatitis B,C and D.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus

that predominantly affects the liver, leading to

inflammation and cell death; in the long term,

some patients develop scarring of the liver

(cirrhosis) and, less frequently, liver cancer.

The spectrum of HBV infection ranges from

acute hepatitis, anicteric hepatitis, fulminant

hepatitis, a hepatitis with a predominantly

cholestatic picture, to chronic liver disease

with minimal acute manifestations. The

danger of HBV lies in the last presentation as

the patient is unaware that he/she is infected

with HBV and may unknowingly transmit it to

others. A few decades later the patient may

develop chronic liver diseases cirrhosis or

hepatocellular carcinoma. HBV shares its

transmission routes with the HIV (the virus

that causes AIDS).

However. <t is one

hundred times as infectious as HIV . Its

potential to cause liver cancer has led to its

recognition as the second most impc riant

carcinogen (cancer-causing agent), after

tobacco. Several hundred million are infected

worldwide and these are the main reservoir of

HBV infection. The predominant moce of

transmission is parenteral i.e by infected

blood transfusions, contaminated syringes

and needles and unsterile instruments used

for surgery, Other nTodes of transmission are

perinatal and sexual. Inapparent parenteral

routes of transmission like use of shared

razors and toothbrushes, and contaminated

needles used for acupuncture, ear-piercing

and tattooing are also known.

An estimated 400 million persons worldwide

are known to be chronic carriers. One in ten

of these is in India, making this country the

second largest pool of the virus. The 40

million - 50 million Indians who carry this

virus form approximately 4% - 5% of the

general population. Various estimates place

the number of infected newborns who Vvill

become carr-iers at 1,50,000 - 4,50,000

annually.

SPECIAL PROBLEMS IN INDIA

The enormity of the problem in In^’a is

indicated by the above available data. Other

factors may compound or aggravate the

situation.

Probably the most important among thes^ is

the HIV. With an estimated 2 million carriers

of the HIV already in this country, Indic is

slated to become the largest pool of HIV in

•the world by the turn of the century. It is well

known that persons immunosuppressed by

HIV infection are more susceptible to other

infections. Since HIV and HBV shjre

transmission routes, high-risk populations will

also be common to the viruses. Data exists to

show a «symbiotic relationship between thqse

viruses ; the effect of HIV

infection

.........

—

on the

progress of HBV infection is not likely to be

favourable, though admittedly data are still

-----

I

lacking.

Coinfection or superinfection by the other

hepatitis viruses (A,C,D,E,G) all of which are

common in India - on a liver already diseased

by HBV can be further detrimental. Data on

such multiple infections with HBV and the C

d D viruses are already available and are a

cause for concern.

The effect of poor nutrition and alcoholism on

HBV liver diseases is not clear yet, though the

latter

is

an

established

liver

toxin.

Administration of antitubercular drugs - many

of which are known to damage the liver - can

also aggravate the condition. It is of course,

common knowledge that tuberculosis is

widespread in this country.

I

-

i

i

l

i

Finally, ignorance and poverty among the

populanon make it difficult to implerhent

barrier habits. It is believed that 30% - 50%

of the blood banks in the country do not

routinely test for the HBV; most of them are

also dependent on paid 'professional' donors

for their supply of blood. This forms a major

source of infection especially amongst the

ignorant who frequent these blood banks to

obtain blood on payment, out of a mistaken

fear among relatives that donating blood is

harmful to physical (including sexual) and

mental well-being. Unfortunately the same

populace is also likely to request blood

transiusion as a 'tonic'.

Preventive Measures

i

The concept of "universal precautions"

requires that all human blood and certain

body fluids be treated as potentially infectious

for HIV, HBV and other blood-bornJ

pathogens, and maximum precautions be

taken at all times when in contact with such

tissue.

Hands should be washed with soap and water

immediately after removal of gloves or other

protective coverings ; if handwashing is not

possible, an appropriate antiseptic cleanser

may be used, and handwashing done as soon

as possible. Any body surface that has come

in contact with potentially infectious material

should be washed with soap and water, or

flushed with water as appropriate.

A particular concern in India is the reuse of

razor blades by haircutters. It is advisable for

the customer to carry his/her own blade:

alternatively, it must be ensured that these

sharps are either disposed off or are

adequately sterilised before reuse.

Disposable / Sterilisable equipment :

All inexpensive equipment and accessories in

use in healthcare settings should ideally be

disposable. When such items are marked as

.sterlisable and reusable, the manufacturers'

guidelines for sterilisation should be adhered

to. Expensive multiple-use items

leg

endoscopes, ventilators, humidifers) should

be thoroughly cleansed mechanically and

sterilised as per the manufacturer's

guidelines, before reuse.

General Measures

Education : The single most important

measure initially is promotion of awareness

and dissemination of information. This should

be addressed both to the general public as

well as to high-risk groups.

Barrier precautions : Among healthcare

workers and emergency care providers

{firemen, ambulance personnel) at all levels,

and especially at the earlier levels in the

hierarchy where contact is more likely (labour

staff, primary healthcare workers, technical

staff, student and staff nurses, medical,

dental and paramedical students , resident

doctors) the use of hand gloves should be

made mandatory at all times when in contact

with biological specimens.

Blood Banking Practices :

Blood banks should be allowed to operate in

this country only if registered with central or

state-level regulatory authorities, who in turn

should enforce a phased replacement of

professional donors by voluntary donors, use

of disposable items for all collection,

transport, resting, storage, and transfusion

purposes, nesting of all collected blood for

HBV/HIV, and preferrably the hepatitis C

virus, use of sensitive third-generation tests

for markers of the above viruses.

In addition to the above measures, medica

professionals should be educated on the

judicious use of transfusion of blood and itc

products.

Vaccination :

Currently fe'e are two types of hepatitis B

vaccines avanaole around the world i.e the

first genera: on plasma derived" inactivated

HBV vaccmes and the second generation

’’genetical!', engineered or recombinant" HBV

vaccines. In the US and in most parts of

Europe the 'ecombinant HBV vaccines have

replaced the plasma derived HBV vaccines.

The plasma derived have been widely used

and have been shown to be safe and effective

but there is an unfounded fear about the

transmission of viruses as these are derived

from the b<ood of a person suffering from

HBV. These vaccines have a long production

cycle, require persons having HBV infection

and hence their supply may be limited. The

level of antibody persistence may vary with

the vaccine and the dose administered.

Recombinant DNA techniques have been used

for expressing hepatitis B surface antigen and

core antigen in prokaryotic cells. These

vaccines are totally synthetic and don't

require the use of blood pr blood products.

The recombinant vaccine, consists of the

purified antigen absorbed onto an adjuvant,

usually alum. Recombinant yeast hepatitis B

vaccines have undergoneextensive evaluation

by clinical trials. The results indicated that

this vaccine is safe, antigenic and free from

side effects (apart from minor local reactions

in a proportion

of recipients).

The

immunogenicity is similar to that of the

plasma-derived vaccine. Recombinant yeast

hepatitis B vaccines are now being used in

many countries. The advantages of the

recombinant vaccine is the unlimited supply,

as no blood products are involved and a

shorter production cycle.

The recombinant vaccine currently available

commercially in India is administered as 20microgram doses (10 micrograms in newborns

and children) at 0, 1 and 6 months. Dose

recommendations for the plasma-derived

vaccines vary from 3 micrograms to 20

micrograms at 0,1, and 2 months or 0, 1 and

6 months. Double the above doses is

recommended for immunocompromised

individuals (e.g in AIDS, and for patients with

chronic kidney failure undergoing dialysis); a

fourth dose is also recommended.

Who should be vaccinated ?

The immediate aim should be to vaccinate

high -risk groups. At the community leve ,this includes healthcare workers, emergency

care providers, and commercial sex workers.

It should be the responsibility of employers to

provide free vaccination to all healthcare

workers and emergency care providers. Such

vaccination should be provided preferably at

entry into training or employment. Catch-up

vaccination of senior personnel should be

done in a phased manner.

At the individual level, patients needinc

multiple transfusions of blood or its products

(haemophiliacs, thalassaemics etc.); those

undergoing elective surgery or dialysis;

newborns of mothers known to harbor HBV ;

sexual partners of HBV carriers and intimate

contacts of patients with acute hepatitis B ;

inmates of institutions (mental homes, old-age

homes, handicapped-persons homes, prisons);

and individuals with high-risk behaviour

(intravenous drug addicts, alcoholics,

homosexuals , promiscuous individuals)

should be recommended vaccination.

All newborns should be vaccinated by

introducing this vaccine into the Expanded

Programme of Immunisation. The World

Health Organisation has recommended that

this be done by the year 1997; over 80

countries have already done so. The Indian

Academy of Pediatrics

----------------and the Indian

Association for Study of the Liver have

endorsed this approach.

Experience in countries in South-East Asia has

shown this results in a remarkable reduction

not only in the HBV carrier rate but also in the

prevalence of liver cancer, within a few years.

\ NEW

I

WHO ANNOUNCES INFLUENZA VACCINE

FORMULA FOR 1996/1997

A new composition of the influenza vaccine for the 1996 - 1997 season has been

/Ljrn

announced by an international experts meeting at the World Health Organization (WHO)

headquarters in Geneva. Scientists are constantly challenged to identify major newly emerging

strains of influenza viruses, so that effective vaccines can be formulated in time, Compared

of the

to last year's recommendations for the vaccine, one c.'

J.- three

2----- influenza vaccine

components has been changed.

Every February, the influenza experts advise the national health authorities and

pharmaceutical companies on the composition of the virus strains that should be used to

produce vaccines for the next influenza season.

Influenza causes epidemics worldwide every year. WHO strongly advises the use of

vaccine as a sound preventive measure against this potentially fatal disease. Special attention

should be paid to vaccinate the elderly, individuals with immunodeficiency, sufferers of

chronic diseases of the heart or lungs as well as diabetes.

adequate. However,

For the adult population one dose of inactivated vaccine should be adequate,

previously unimmunized children in these categories should receive two doses of vaccine,

with an interval between doses of at least four weeks.

"The degree of protection conferred by influenza vaccines varies depending on the age

of

and immune status of the vaccine recipient", explains Dr Daniel Lavanchy, in charge o.

WHO's influenza programme. "We believe that Up to 80 per cent of recipients will^be

circulating

protected against disease when there is a good match between the vaccine and f--**

,~**~2

strains. The severity of illness and the frequency of serious complications is reduced among

the remaining 20 per cent".

The latest formula recommended by WHO is:

n an A/Wuhan/359/95(H3N2)-like strain

n an A/Singapore/6/86(H 1 N1 )-like strain

s a B/Beijing/1 84/93-like strain.

This differs from last year's composition in that the first of these strains replaces an

A/Johannesburg/33/94(H3N2)-like strain.

As in previous years, the specific viruses used in vaccine manufacturing in each country

will need to be approved by the national control authorities.

!

.i

Press Release WHO/IO

Page 2

The WHO programme on influenza surveillance and control was established in 1948

Today, it involves 109 WHO-recognized National Institutes on Influenza in /9 countries, and

threeWHO Collaborating Centres for Reference and Research on Influenza at the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, USA), the National Institute for Medical Research

(London, UK), and CSL (Parkville,Australia). This fully operational network help§'WHO to

monitor influenza activity in all regions of the world and ensures that WHO receives

information needed to select the new variants of influenza viruses which will be used

used to

to

produce influenza vaccines for the next influenza season.

There are three main antigenic types of influenza viruses currently circulating among

humans all of which have a remarkable capacity to change their characteristics from year to

year. These are known as A(H1N1), A(H3N2) and B. Vaccines are, therefore, composed of.

two strains of type A and one of type B. With new strains continuously emerging, scientists

and pharmaceutical industry face an annual challenge to produce modified vaccines wpich will

be effective against the latest dominant strains.

Epidemics of influenza were reported between October 1995 and February 1996 in

“

__ j-iA—____ -J A

many countries

in rEurope, ki

North

America,

and Asia. After few rnr>r\rtc

reports in

in (Ir'tmrv

October 1 995,

influenza activity increased in November and reached a peak in December and, n some

countries, in January 1996. By February, influenza had declined in most countries. Influenza

A viruses have been widespread and caused moderate to severe epidemics affecting mainly

children and young adults. European countries and China reported predominantly influenza

most+ —

regions -of

A(H3N2) while influenza A(H1N1) caused epidemics in Canada,

C—--1-. Japan and1 —

the United States of America.

The first outbreaks of influenza A(H3N2) were reported in boarding schools in England

in September and October 1995. The disease spread in the United Kingdom and appearedI in

other European countries during November and December, causing epidemics across most of

Europe (Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece,

Hungary, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway; Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden and the United

Kingdom), Madagascar and the USA. Outbreaks of influenza A(H3N2) started in Beijing

towards the end of December and spread to six provinces in China during January. Isolates

of influenza A(H3N2) virus were also reported in Canada, Europe (Belgium, Ice and.ilreiand,

Italy, Poland, Portugal, the Russian Federation, Switzerland) as well as in Asia (Guam, Hong

Kong, Japan, Singapore) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand).

Influenza A(H1N1) caused a widespread epidemic in Japan in December 1 995, and was

the predominant virus in North America (Canada and the USA) and parts of Europe (Belgium,

southern France, and Switzerland). These viruses were also detected elsewhere in Asia

(China, Hong Kong, Israel, Thailand) and Europe (Finland, Germany, Italy, Latvia, the

Netherlands, Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the UK).

Sporadic cases of influenza B have been reported in North America (Canada and the

USA), in Asia (China, Hong Kong, Israel, Japan and Singapore) and in Europe Belarus,

Bulgaria, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, the Russian

Federation, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK). A few isolates in Oceania (Australia ^nd New

Zealand) have also been reported.

’’The WHO influenza surveillance network together with the influenza vaccine

manufacturers ensure that effective vaccines are available to the public in time to provide

protection against each season's influenza epidemic”, says Dr Nancy J. Cox, Director of the

WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza in Atlanta, USA. Ibis

joint endeavour represents a very successful collaboration between the public and private

sectors, in the interests of public health”.

For more information, please contact Valery Abramov, Health Communications and Public Relations,

WHO, Geneva, Tel. (41 22) 791 2543 or Fax (41 22) 791 4858. E-mail abramovv@who.ch.

Le^tSLAVoN < I

IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR PRESCRIBERS

As per a recent Supreme Court ruling, doctors of modern meo ••

registered under Indian Medical Council Act are permitted to prescriz-■e

ONLY allopathic medicines. Prescription or administration of non-allops:'. •

drugs (such as Ayurvedic, Unani, Siddha or Homoeopathic) shall renze

such doctors liable to prosecution under both civil and criminal

■

resulting in cancellation of registration and/or heavy fine and/or impns; • •

ment. Doctors of modern medicine prescribing non- allopathic dri.-z?

are liable to be considered as "quacks" per se without further evide- ' or argument.

Full text of the Supreme Court judgement and the opinion of law. • • from a leading hm of advocates can be obtained from MIMS by sene r z

a self-addressed, stamped (Ps. 2) envelope of the size of 24 cm x 16 c.m.

-------

Mims

I

fL -

!

I

I

F

I

-------- \

a

FORMATION OF IMA SERVICE DOCTOR’S WING

AND IMA WOMEN DOCTORS’ WING.

4

4

4

k

|

I

4

I

t

4

The Central Working Committee at'its meeting held in New Delhi on 2f th-26th

November, 1995, approved the formation of IMA Women Doctors’ Wing and IMA.

Service Doctor s Wing and also accepted in principle the basic structure of the

Constitution of these Wing. It also decided that these Wings will become operative

from the date on which their membership reaches 1,000. This was approved by the

Central Council at its meeting held at Bhubnesawar on 27th-28th December , 1995.

The eligibility conditions and rates of subscription and admission fees of the two Wings

are as under:-

IMA Women Doctor’s Wing

4

a

■

I4

4

4

4

•

4

4

4

■

a

Eligibility : Any Women Life Member of IMA may be enrolled as Life Member of IMA

Women Docotor’s Wing.

Admission Fee: Rs. 30/- per member.

Life Membership Subscription Rs. 450/- per member.

4

■

■

4

4

4

4

4

4

4

A State Wing of Women Doctors’ will be formed on-enrolment of a minimum of 50

members of the Wing.

■

■

IMA Service Doctor’s Wing

■

■

■

■

Eligibility : A Life Member of IMA engaged in any type of service may be admitted as

Life Member of IMA Service Doctor’s Wing.

*

■

■

Admission Fee : Rs. 30/- per member

Life Membership Subscription: Rs. 450/- per member.

A State Wing will be formed on enrollment of a minimum of 50 members of the Wing.

All State and Local Branches Secretaries are requested to start enrollment of members

of these two Wings. Membership Application'forms may be obtained from IMA Head

Quarter.

■

■

4

s

K

■

a

■

■

IMA News

5

■

April, May, June, 1996

■I

I

fTHICS

\

1

The Doctor's Dilemma —

Socio-Ethical Issues Related to AIDS

- - r Him....... mu

............

Whether we like it or not, the pandemic of AIDS

has reached India, and according to postulation, the

epidemic peak with explosive outbreaks of HIV

positivity is yet to occur. In the medical profession

arc we ready to face the challenge ?

The uniqueness of HIV arises mainly out of its

four characteristics.

First, handling a HIV positive patient entails a cer

tain amount ofphysical risk of being contaminated.

Hfr Mcrtir

2. Hov) to confirm the diagnosis? ELISA for HIV

can be false positive, particularly among "Iovj

risk* people.

3. To avoid the risk ofcontamination can a su rgeon or

a gynaecologist routinelyperform preoperat'rve HIV

testing? What happens ifthepatient withhAds con

sent? What to do during an emergency surgery ?

4. Can a doctor refuse to operate or perfo. rm any

invasive procedure on a seropositive patient ?

Second, the long clinical latency means th.it ;uiybodv

could be seropositive without showing any signs and

5. Has a doctor the right to thrust a moraljudgement

symptoms.

on a patient (and his/her behaviour) and then de

Third, because HIV is also sexuallv transmitted, i

cide his/her professional attitudes accordingly?

there is a prevalent attitude of attaching a stigma of j

I 6. Ho-w does a doctor arrange the folia

'ozo up and treat“loose moral" to the infected.

ment

of

HIV

positive/AIDS

cases?

Fourth, as yet there is no cure for AIDS, and all

HIV positive^ have so far been seen eventually to

die due to AIDS or its complications.

8. Except under afev) circumstances a doctor is profes

sionally bound to maintain absolute confidentiality

about a patient and his/her condition. Should it be

follovoed in case ofHIVpositives?

Relating to the AIDS menace, the medical profes- i

sion has to come up with answers to a lot of ques- I

tions not only technical but also social and ethical, j

Let us look into the issues more closely.

However, disclosure may break thefamily and ruin

the patient. Hovo to prevent the social catastrophe

arising out ofdisclosure ?

Should the doctor inform the spouse about the

patient's seropositive status ? Nondisclosure may

spread the disease and may infect the spouse

9. Should a HIV positive denied social and zj•orbing

1. As in other biomedical investigations, a doctor connot '

rights ? What follovos is, if a doctor becomes

ask for HIV testing (e.g. ELISA) without the con- |

seropositive should he/'she be debarredfrom handling

sent ofthe patient - voluntary and Informed. More- ‘

patients ?

over, because of the consequences uj

•

tionassociai/dwithAIDS.pretestcouncellirigisman- ; .10. How to prevent iatrogenic AIDS ? How can a doctor raise the demand individually and collectively da tory. Ge vet; our busy practice, are we prepared/'

ofensuring aseptic procedures in medicalpractice ?

tuned to do this

i

91

39

•

i

7. Hovj to trace the source/route of transmission in a

specific case, in ord^r to preventfurther transmis

sion from the same source ?

The fear of physical risk and social contamina

tion virtually stigmatises a HIV positive into a so

cial outcast. What inevitably follows is discrimination-a HIV positive is denied his/her basic rightsthe right to live (in a community) and work and

what is important in the present context-right to

be treated.

Drug Disease Doctor

f*

I

I

1

Obiter dicta

92

1

•

Absolute quarantine of all HIV positives has been tried in different parts of the world.

But this has failed to contain the epidemic. Testing all persons for HIV is theoretically

possible but logistically impossible in a country like India. Even testing all persons be

longing to so called high risk groups is virtually not possible.

•

Large multi-institutional studies have indicated that the risk of HIV transmission fol

lowing skin puncture from a needle or other sharp object that was contaminated with

blood from a person with documented HIV infection is approximately 0.3%. The risk of

a similar type of exposure to hepatitis B is 20 to 30%.

•

The above mentioned risk, however small becomes a potential threat in Indian condi

tions. In most hospitals and pathological laboratories here, medical personnel draw

blood without wearing gloves and bloc J opill-ge and skin puncture are common

occurences. Anaesthesiologists almost never use gloves. Dentists all over the country

usually perform all outdoor dental procedures without wearing gloves.

•

Nosocomial HIV infection is a reality. In a reported incident in Soviet union 152 neo

nates were infected through use of contaminated syringes and needles. This is of par

ticular concern in the Indian situation Disposable syringes and needles are not only in

short supply in most hospitals, these are often reused after washing or boiling. There is

generally a casual approach to sterilisation procedures except in the operation 'heaters.

(Consider the daily morning activity in the •..•aids when almost all patients have their

blood samples taken.)

•

HIV infected persons have relatively greater number of viruses in their blood during

two stages - the initial post infection viracmic stage and much later during the symp

tomatic stage. During the initial phase of infection lasting tor an average of 2 weeks

(and a maximum of 8 weeks) the HIV infected is seronegetive. What follows is at this

time though the person is ELISA negative, he/she can transmit infection.

•

Ina hospital set up or even in a private clinic, unless spccificallv informed, a doctor may

have no idea as to which of his\her patients belong to the high risk groups. High risk

groups are those who are involved in high risk behaviour (sex workers, clients of sex

workers, intravenous drug users) and the se \ rho are being repeatedly treated with blood

or blood products (haemophilia or thalassaemia pudents).

•

The risk of HIV transmission from an infected doctor to his/her patient is extremely

small. Large multi-institutional studies have put the risk of acquiring HIV infection

from a doctor or a dentist during an exposure prone procedure at 1/1000000, which is

l/10,h the risk that a given unit of screened blood is HIV positive and l/100‘h the risk

of dying from general anaesthesia.

Drug Disease Doctor

39

T he number of HIV infected in this country is

steadily increasing. What happens doctor, if the

next patient in your clinic is HIV positive ?

What happens if the patient declares that he

is HIV positive ? Would you examine the patient

or would you refer him to some other doctor ?

What happens if the patient does not declare

or is himself unaware that he is HIV positive. Is

your system of patient handling such that you

yourself would not be contaminated and would

not transmit the infection to your other patients ?

If you are a professionally active doctor you

can hardly avoid handling a HIV positive. What

is most needed is a predetermined approachscientific, ethical, humane and bold.

The AIDS pandemic has shown its capacity

to evolve and permeate all sectors of society. It is

useless to think that my patients cannot be HIV

positive, as they are all good and respectable

people. Complacency, indifference, denial and

a “business as usual” attitude threaten the

success of the struggle against AIDS.

It is obvious that neither does screening ex

clude all HIV positive nor is screening feasible in

all situations. What is feasible is strict adher

ence to standard procedures of asepsis in

medical practice - irrespective of who your

patients are.This is the only tenable method

of avoiding the transmission to your other

patients. There is no need to shun awav the HIV

positives if you adhere to the nonns of asepsis.

their fight against AIDS. Ultimately in the

end we all have to adapt to the situation of pro

viding optimal health care to the HIV positives

and AIDS patients without discrimination and

with due protection of their rights and dignities.

The quicker we reach the stage the better.

We must remind ourselves of the paradoxi

cal situation that if discrimination persists,

not only will people not volunteer for HIV

testing, but will also hide their HIV sta tus.

Discrimination arises out of misinformation

and ignorance. But that is not all. The relation

between knowledge and behaviour is far more

complex. But knowledge and awareness is the

p ria ma ry pre requisite for behaviour modification.

What follows is that our first task is to know about

HIV and its transmission. Only then can w; take

up the challenge to fight the epidemic.

In the fight against AIDS doctors arc speak

ing in the language of human rights and di >nity.

Measures to.protect human rights will not of

themselves guarantee an effective AIDS

programme, but denial of human rights is clearlv

incompatible with effective AIDS prevendoh and

control.

Today, it is important to realise that

social solidarity has now become

a public health goal, on which

the survival of entire societies

may depend.

— Carballo &. Bayer

r»

,

’I

Today in India, there are media reports oil" and

on of discrimination against HIV positive - in

References

the communit}’ and also in the health care set 1. Harrison i Princifies of Imemal Medicine, 13th edition 1994

ups. But the HIV positives and AIDS patients 2. HIVrisks in the health care organisation,Julie Louise Gerberding,

AIDS 1990, 4 (suppl 1)

are being treated the world over in general hos

3. Glohai AIDS: revolution, pa rudi^tn and solidarity,Jonathan Mann.

pitals, private clinics and in intensive care units.

AIDS 1990, 4 (suppl 1)

Why is the situation different in India ?

4. Social Cultural and Political Aspects, Manuel Carballo and Ronald

B«yer,AIDS 1990,4 (suppl 1)

Such avoidance reaction have occured all over

the world. But many doctors have also engaged 1 Asish Kumar Kundu

Drug Disease Doctor

I

39

93

A

Declaration of Standing Committee of

Doctors of the EC

The Standing Committee of Doctors of the European Community (EC) adopted the following Declaration concern

ing the practice of medicine within the Community at its Plenary Assembly Session held in Nuretnbtirg in

November 1967 (Charter of Nuremburg (original in French)). The text is as published in The Handbook of Policy

Statements 1959-1982, Standing Committee of Doctors of the EC.

1. Every man must be free to choose his doctor. Every man must be guaranteed that whatever a doctor’s ob ligations

vis-a-vis society, whatever he confides to his doctor and to those assisting him will remain secret.

Every man must have a guarantee that the doctor he consults is morally and technically totally independent and that

he has free choice of therapy.

Human life from its beginning and the human person in its integrity, both material and spiritual, mus^e the object

of total respect.

Guarantees of these rights for patients imply a health policy resulting from firm agreement between those responsi

ble to the state and the organised medical profession.

2. The aim common to the health policy of states and medical practice is to protect the health of all its citizens.

It is the duty of states to take all precautions to ensure all social classes - without discrimination - have access to all

the medical care they require. Every man has the right to obtain from the social institutions and the medical corps

the help he needs to preserve, develop or recover his health: he has an obligation to contribute materially and

morally to these objectives.

Economic expansion finds one of its principal human justifications in the advancement of resources allocated to

health; the medical profession intends to do all in its power to increase, at equal costs, the human and social effec

tiveness of medicine.

3. The unusual necessary contact between the doctor and his patient take account of the fact that these two partners

belong to one community, a condition of all health and social policy. But there must be reciprocal confidence

between the patient and his doctor based on the certitude that in his treatment the doctor holds in the highest esteem

and has consciously consecrated all his knowledge to the service of the human person. No matter what hi s method

of practice or remuneration the doctor must have access to the existing resources necessary for medical intervention; he must have free choice of decision bearing in mind the interests of his patient and the concrete possibilities

. offered by the advancements of science and medical techniques.

Doctors must be free to organise their practice together in a manner complying with the technical and sociaf need of

the profession, on condition that moral and technical independence be respected and the personal responsibility of

each practitioner maintained.

4. Whatever is method of practice the medical profession is one. These methods are complementary. They derive

from the same deontology although they may be submitted to different organisation conditions. Respect for moral

laws and for the basic principles of medical practice is assured by independent institutions, emanating from the

medical corps and invested, particularly under the highest judicial processes in the country, with disciplinary and

judicial power.

Every doctor lias a moral obligation to actively parucipate in his professional organisation. Through this organisa

tion he participatcs in the elaboration of the country’s health policy. Members of (he profession can and must fight

for respect of basic principles in the practice of medicine, on condition that the rights of the patient are.safeguarded.

5. Hospital equipment must be within the compass of its specific mission in the service of the whole population. Its

establishment is the result of a planned policy in which the public powers and the organised profession participate,

allocating to public power and private initiative fuller distribution of health establishments. It comprises, a variety

of establishments, graded and co-ordinated among themselves, meeting the task or several tasks given to t: prevention. care, rehabilitation, teaching, research.... The professional independence of the hospital doctor must be

guaranteed by unquestionable criteria of nomination and a statute assuring him stability of function, economic

independence and social protection.

‘Technical progress, the basis of our industrial civilisation and economic expansion which is its fruit have for their

natural end especially thanks to a health policy, to bring about full physical and spiritual development of man. of ail

men’.

[Rowe AJ et al: Philosophy

102

Practice of Medical Lillies. London: British Medical Association 1988. |

Issues in MEDICAL ETHICS

VOL.4 NOJ JUL-SEP 1996

facts

from the

Regional Health Report

10 countries make up the WHO

South-East Asia Region (SEAR)

— Bangladesh, Bhutan, DPR

Korea,

India, Indonesia,

Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri

Lanka and Thailand.

Population &

Socioeconomic

Situation

About 1.4 billion people live

in the WHO South-East Asia

Region. The 10 Member States

comprise 25% of the world’s

population and only 5% of the

world's land area.

Over the past 15 years the

Region’s population has grown by

367 million and is expected to

increase by another 380 million

during the next 15 years.

Population growth rates of

most SEAR countries have declined

since 1980-85. Three countries Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand

have annual growth rates lower than

the world’s growth rate of 1.57%

(1990-95).

Jw

The number of people living

in urban areas has increased from

almost 229 million in 1980 to 389

million in 1995, and is expected to

reach 460 million by the year 2000

and 641 million by the year 2010.

96

The average annual urban

population growth rate (1990-95)

is highest in Nepal at 7.07% and

lowest in Sri Lanka at 2.20%. The

Region contains four megacities Mumbai, Calcutta and Delhi in

India and Jakarta in Indonesia.

F

In 1995 there were a higher

proportion of children aged 0-14

years living in the SEAR countries

as compared with the rest of the

world; but lower proportions in the

adult (15-64 years) and elders (65

years and more). This trend is likely

to continue until 2010. The number

of elders in the Region is expected

to increase by 10.6 million during

1995-2000, putting a greater

pressure on the health-care and

welfare system.

Most countries showed a

steady GNP growth rate during

1992-94. The gross national product

(GNP) per capita in the Region

ranges from a low of US$170 in

Bhutan to a high of US$2110 in

Thailand (1993). India, Indonesia

and Thailand are included among

twelve major developing economies.

The amounts spent on health differ

among countries. As a percentage

of total income (in terms of GDP),

expenditures range from 2% to 6%

including both government and

private expenditures.

Data on burden of poverty in

1990 were available for six SEAR

countries (Bangladesh, India,

Indonesia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and

Thailand) which represented 95%

of the total SEAR population and

included 507 million people in

poverty - whose income or

expenditure level was below the

amount considered necessary to

afford a minimum, nutritionally

adequate diet plus essential non

food requirements. Poverty is also

widespread in some other SEAR

countries.

'S Literacy rates in 1995 ranged

from 40.9% and 14% for males and

females respectively in Nepal, to

100% for both sexes in DPR Korea.

Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and

India have the lowest female literacy

levels of between 14% apd 38%

respectively. Countries wi(h higher

female literacy tend to have lower

infant mortality.

9

Countries with low fertility

have a higher human deve opment

index (HDI) and gendcrirelated

development index (GDI). Only

one SEAR country (Thailand) has

HDI or GDI above 0.8, putting it in

a higher human development

category. Much progress remains

to be made in gender equality in

almost every country of the Region.

Efforts are to be made so that women

are able to participate in political

decision-making, to increase their

access to professional opportunities,

and improve their earning power.

Births, Deaths

and Life

Expectancy

ire

Since the 1970s, the

birth rates in the Region declined as

crude

a result of population control and

family planning efforts. They now

range from a low of 19.4 in Thailand

to a high of 41.6 in the Maldives.

Thb world average is 25 per 1000

population.

F Women had fewer children in

the past five years than before as

seen from the decline in the total

fertility rate (TER) for the Region.

CA facts from the

Stir Regional Health Report 90

During 1990-95, the TFRs ranged

from 2.10 children in Thailand to

6.80 children in the Maldives per

woman in the reproductive age

group of 15-49.

jfi

Life expectancy at birth

showed an increase for all SEAR

countries. During 1990-95 it was

below 60 in Bangladesh, Bhutan,

Myanmar and Nepal; it was

between 60 and 69 years in India,

Indonesia, Maldives and Thailand

and was 70 years or above in DPR

Korea and Sri Lanka.

K There has been a significant,

steady decline in the crude death

rate in the Region, now ranging

from 5.3 per 1000 population in

DPR Korea to 13.3 in Nepal. These

rates must, however, be viewed

with caution as death registration

systems in most countries remain

inadequate.

The infant mortality rate

(IMR) declined in all countries, but

Bangladesh, Bhutan, India,

Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal

still have unacceptably high rates

of 70 deaths or above during the

first year of life per 1000 live births.

DPR Korea, Sri Lanka and Thailand

have IMRs below or around 30 per

1000 live births.

Morbidity and

Mortality

Communicable Diseases

F Almost 7 million people in

SEAR countries die each year from

infectious diseases alone. Infectious

diseases are the leading cause of

death worldwide, killing at least

17 million people annually.

F Approximately 1.4 million

children under five die each year

from acute respiratory infections

(ARIs) accounting for more than

30% of deaths in undcr-fivcs.

Pneumonia is the leading cause

taking 90% of this total. Deaths

due to pneumonia could be signi

ficantly reduced by the use of

standard case management as

recommended by WHO ARI

Control Programme.

Tuberculosis still kills more

adults than any other single

infectious disease - an estimated 1.2

million people in the Region will

have died during 1995. 80% of

these deaths are in the most

productive age group 15-59 years,

thus affecting socioeconomic

development of countries. The

most effective way to stop the

spread of tuberculosis is by

curing it and the best curative

method known is directly observed

treatment short course (DOTS).

|F5 TB/HIV co-infection

is

present in many patients - by 2000

it is estimated to increase to

nearly 20% of all TB cases. The

proportion of TB deaths attri

butable to HIV in the Region will

also increase from 2% in 1990 to

14% by 2000.

F The total number of the

leprosy-afflicted in the Region is

more than two-thirds of the global

leprosy cases. Four countries Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and

Myanmar are among the top five

countries accounting for fourfifths of the global case load. Yet

multi-drug therapy (MDT) has

proven so successful that it is

expected to eliminate leprosy as a

public health problem by 2000.

F The Region has achieved a

high level of immunizing children

under one year against the six

immunizable diseases - diphtheria.

pertussis, tetanus, tuberculosis,

poliomyelitis and measles. By the

year 2000, ninety per cent of women

in the child-bearing age will have

been immunized against tetanus.

The Region has demonstrated

dramatic acceleration of polio

eradication activities, particularly

with the implementation of

national immunization da; in seven

SEAR countries. Health experts

are confident that they will be able

to eradicate poliomyelitis through

effective universal immunization

and adequate epidemiological

surveillance.

F A 70% reduction in the

number of reported diphtheria and

whooping cough cases has been

achieved as a result of the 90%

immunization coverage.

39

The total number of measles

deaths in the Regie n has

decreased by about 87% and the

number of reported cases has fal Ion

by about 67% as a result of about

80% immunization coverage.

r4 Five SEAR countries (phular,

DPR Korea, Maldives, Sr Lanka

and Thailand) have achieved the

target of no more than one neonatal

tetanus case per 1000 live births.

IK The pandemic of HIV/AIDS

has spread rapidly during he last

few years in the South-Eapt Asia

Region. It is estimated hat by

the end ofthe century, 8 to 10 million

men, women and children are likely

to become infected wit 1 HIV

accounting for over 25% of the

global cumulative infections. The

spread of AIDS/HIV is particularly

significant in India, Myauniar and

Thailand.

F The total number of curable,

sexually transmitted diseases

(STDs) in the South-Eas Asia

Region were 150 million cases in

1995.

r

Each year, approximately 14

million people are infected With the

hepatitis B virus, and it is est mated

that there are 80 million carriers, i.e.

CA fac*s ^rom the

vV Regional Health Report 90

more than 5% of the total

population.

Diarrhoeal diseases continue

to account for about 25% of underfive mortality in the Region, viz.

over one million children die each

year from diarrhoea. 90% of these

deaths are preventable.

Malaria still dominates the

disease pattern in the Region with

1.2 billion people living in

malarious areas, and at risk. The

overall malaria situation in the

Region has remained static over

the last twelve years - with reported

cases ranging between 2.5 and 3.1

million, and reported deaths

between 5000 and 7500. The

estimated numbers of malaria

cases and deaths are much higher.

The emergence of drug-resistant

malaria and its rapid spread are

posing a major threat to the Region,

and putting severe pressures on

the countries' scarce resources.

Dengue

and

dengue

haemorrhagic fever continues to

persist in several countries - an

estimated 400,000 cases with

8000 deaths were reported in the

Region during 1995. Tetravalent

live attenuated dengue vaccine

has been developed in Thailand,

with support from WHO, and

clinical trials of this vaccine in

children are under way. This is

the first time a developing country

has successfully carried out the

development of a vaccine for

human use.

RT

In India alone, there are an

' estimated 45 million microfilaria

carriers and 19 million people in

the Region are suffering from

filarial diseases, and approximately

500 million people arc at risk.

32 During 1995 there were an

estimated 21,000 cases of Jap

anese encephalitis with 4000

deaths in the Region. In the same

year, the number of meningo

coccal meningitis cases was

estimated to be 20,000 with 5000

deaths.

33 At present, approximately 110

million people in the Region are at

risk of contracting visceral

leishmaniasis (kala-azar). Major

endemic foci have been reported

in border areas between India,

Bangladesh and Nepal. A dramatic

decline in kala-azar cases and

deaths is reported in India since

1994.

No plague cases have been

reported in the recent past from

Bangladesh, Bhutan, DPR Korea

or the Maldives. But natural foci of

plague exist in India, Indonesia,

Myanmar and probably in Nepal.

The reappearance of human

plague in India in 1994 after 27

years caused much concern,

necessitating regular serological

tests of rodents for predictive

surveillance and laboratory

diagnosis of plague in the Region.

Non-communicabie diseases

P5 In India alone, nearly 800,000

persons die from ischaemic heart

disease and more than 600,000

from stroke each year. A health

survey in New Delhi showed that

every tenth person aged 35-64

years suffers from ischaemic

heart disease, and every fourth

person has high blood pressure.

The most common neopl

asms in India are cancers of the

breast, uterine cervix, lip. oral

cavity and pharynx In Thailand,

liver cancer is the most frequent

malignancy among males (8000

new cases every year) and lung

cancer is second in rank

(4700 cases). These two cancers

account for 44% of all new

malignancies in men. In women,

cervical cancer is the most frequent

(5600 cases annually) followed by

liver cancer (3500), breast cancer

(3300) and lung cancer (2600).

These four cancers account for

52% of all malignancies in women.

^7 Diabetes mcllitus has a

prevalence of about 2% in rural

populations, but a prevalence of

3% and more in url an areas

suggests that urbanization and

affluent lifestyles could aggra

vate the risk of disease.

It is estimated that between 4

and 5 million persons ir India are

afflicted by a variety of severe

mental disorders at any given time.

However, facilities an< support

for the care of the afflicted are far

from being sufficient.

Smoking is attribJted to be

one of the main causes of cancers,

cardiovascular diseases and

respiratory ailments. 3very 10

seconds, somewhere in the world,

tobacco causes another death. It

has been established beyond

any doubt, that death rates for

smokers are two-to-three times

higher than for non-smokers of all

ages.

Other causes of Death and

Morbidity

RG

Accidents and injuries

constitute 9 - 10% of the total

mortality in India * with road

accidents accounting for the

maximum number of deaths.

RT

Some 585,000 maternal

deaths occur globally every year.

About 99% of these happen in

developing countries and 235,000

(40% of the total number) in

SEAR countries. A vast majority

of these lives could be saved with

simple available skills and local

technologies. Effective family

!

\

facts from the

Regional Health Report

..

a

planning, good antenatal care and

attendance of a trained midwife

during delivery arc some of the

crucial factors which could

significantly lower maternal

mortality.

£2 Protein-energy malnutrition

and the three micronutrient

deficiencies of iodine, vitamin A

and iron are the main burdens of

undemutrition in the South-East

Asia Region.

^5 The SEAR Region is home

to almost one-third of the

world’s blind persons. Much of

this blindness is avoidable and

curable. Cataract accounts for

nearly 70% of the total blindness

affecting 8 million persons.

Threats to health and

development from deteriorating

environmental conditions affect

everyone. The World Health

Organization ’s Health and

Environment Initiative aims at

mobilizing the national health

authorities to sensitize other

sectors such as environment,

agriculture, and municipalities to

include protection of health and

environment as part of their

development plansif.To address

urban environmentaT issues, the

WHO Healthy Cities Initiative

"strives to promote healthy living

conditions in urban areas with

local governments as key partners.

Health-Care

Infrastructure,

Approaches and

Resources

There are currently 42,774

health centres of various categories

and 164,337 subcentres operating

in SEAR countries providing a

range of outpatient and inpatient

services, and serving as first referral

points. In addition, more than

746.914 outreach sites, managed

by the community with technical

support from health centre staff,

have been established at the

community level in SEAR

countries.

^16 The WHO Regional Office

has successfully assisted Member

States in developing national

drug policies with a focus on the

availability of essential drugs for

primary health care. WHO

collaboration in the Region has

resulted in the establishment of

appropriate national drug

policies and programmes which

focus on the issues of rational

use, availability, accessibility and

affordability of essential drugs

as well as on their quality, safety

and efficacy.

R7 Many questions related to the

balance and relevance of human

resources still remain unresolved.

Newer problems of imbalances in

the types of health personnel and

their geographical distribution

are also emerging, and these need

to be addressed with care and

urgency. Considering the fact

that human resources for health

(HRH) utilizes up to 70% of health

budgets, some of these problems

lead to very costly imbalances. A

significant emerging factor which

contributes to the imbalance of

HRH in the Region is the increased

competition between the public

and private sectors.

The Challenges

Ahead

48 In 1978, health for all (UFA)

by the year 2000 seemed a

reasonably-paced, achievable

proposition. But now. with only

turn of

three years left before the U...

the century, many of the HFA

goals still seem rather distant

for the 10 countries of the SouthEast Asia Regy>n. The challenges

that lie ahead call for political

commitment, community nvolvcment, and a multi-sectoral approach

to health. A combination of these

three factors could well mcan a

healthier future for South-East

Asia.

^9 Sustainability is one of the

major challenges that governments

will have to face as the countries

move into the 21 st century. Muchof

the success of health prog rammes

is due to investment in terms of

financial and human resources by

countries, WHO, other UN (agencies

and bilateral donors, SEAR

countries will have to meet the

challenge of sustaining such

programmes on their own. Only

through vigorous programme

implementation will a significant

disease

impact be made on the cL

—-situation.

8U Population growthi will be

_ •accompanied by rapid

irbanizaL

tion in developing countries. The

urban population in SEAR is

expected to reach 43% of the total

by 2020. Countries will have to pay

serious attention to the needs of

urban infrastructure - sanitation,

safe drinking water, housing and

public transport - as well as to the

increase in demand for health

services. Providing accessible and

acceptable family planning

services will make a significant

contribution to the health of the

population as a whole.

j

•

'

’

zzJsbA World Health Organization

T-L.

p Regional Office for South-East Asia

v Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg,

New Delhi 110 002, India

MP

The National Law School - NOVIB Project on the Implementation of SocioEconomic Rights

Status and Implementation of the Right to Health in

the State of Karnataka: A Report

Report prepared by

Padmashree B.S

B.A.LL.B(Hons)

National Law School of India University

H

Towards a definition of the right to health

The conceptualisation of rights of individuals has been predominantly based on

the social and political institutions of the time, throughout history. Changes in

society brought about by the development of liberal humanist ideas and democratic

political practices, led to a gradual conceptualisation of rights for all human beings

Beginning with the magna carta, the Declaration of Independence of the United

States of America (1776) and the Declaration of the Rights of the Man in France

(1789), Libertyjustice, equality and human dignity became the essential attributes

of rights of human beings.

The modem concept of human rights, universal and inalienable, emerged from a

conjunction of moral, legal and political perspectives, defining the rights which must

be possessed by alLhuman beings, equally, embodied in the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights, 1948. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, has in modern

times, become the primary instrument which defines and protects rights which

must be guaranteed to every human being, one of the most critical aspects of this

conceptualisation of human rights being the capacity of all individuals to assert

these rights.

Therefore, any analysis on implementation of human rights must proceed at two

distinct levels. One, whether the rights are available an possessed by all human

beings. And second, whether the human beings have the actual capacity to assert

these rights which have been theoretically made available to them.

Subsequent to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in 1966, the United

Nations adopted two major Covenants, one defining civil and political rights1 and

the other, economic, social and cultural rights2. Both Covenants came into force in

1976. The popular consensus on the division of the two sets of rights is that it is

linked to a political division of the role of state in the society. While civil and political

rights are rights held against eveiyone else, economic and social rights impose

duties on governments.

Although the international human rights system has its own limitations, it

remains a framework—one of the few—within which we may attempt to address the

issues of definition, injustice and abuse of human rights and fundamental freedoms

^he International Covenant on Civil and Politicsl Rights(ICCPR).

international Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rightsf ICESCR).

fit

by governments at the global level. The discussion on human rights also provides a

focus for many of the moral and philosophical dilemmas we face in contemporary

society, and the process of determining norms which can be applied to all human

beings so that they may live with integrity and respect is one which challenges US

today in the face of the disintegration of many social and political institutions.

With this background on human rights, it is essential to locate a framework within

which to view the individual's right to health.

Right to Health in the Universal Declaration of Hu:inn? Rights, 1948

The provision pertaining to right to health is contained in Article 25 of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights, which states as under.

Article 25

(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well

being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical

care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of

unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or lack of livelihood in

circumstances beyond his control.

(2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All

children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social

protection.

Right to health as in the international Covenant on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights, 197Q.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural rights, in its Article

12, recognises right to health as:

Article 12:

(1) the State Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone to

the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental

health.

(2) The steps to be taken by the State Parties to the present Covenant to achieve

the full realisation of this right shall include those necessary for:

(a) The provision for the reduction of the stillbirth-rate and of infant

mortality and for the healthy development of the child;

(b) The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene;

(c) The prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational

and other diseases;

(d) The creation of conditions which would assure to all medical service an 1

medical attention in the event of sickness.

The Wprld Health organisation and Right to health

According to the World Health Organisation, health is a

’state of complete physical, mental and social ivell-being and not merely

the absence of disease or deformity”.

This definition can be said to be the embodiment of the concerns of all human

rights instruments of the century, recognising that health is fundamentally a

function of the every society.

From the foregoing International provisions, and the Who definition, it becomes

possible to define an individual's right to health as his right to a complete physical,

mental and social well-being and not just a right to curative services.

This Right to Health is no doubt a right belonging to the category of social and

economic rights, and therefore, this definition of the World Health Organisation

envisages active participation and responsibility of the state in ensuring that health

is a part of the overall development process of the nation'3

The role of the state in ensuring the right to health

The Declaration of Alma Ata, and various other doctrines that have been built

up by member states through the World Health Organisation and other

international agencies embody a number of fundamental principles for health

development. Among these are :

1. The responsibilities of governments for the health of the people

2. The right and duty of people individually and collectively to participate in the

development of their health;

formulating Strategies for Health for all by the year 2000, World Health

Organisation, Geneva, 1979, Pg.l 1

4 Formulating Strategies for Health for all by the year 2000, World Health

Organisation, Geneva, 1979, Pg. 11

3. The duty of the governments and the health professions to provide the public

with relevant information on health matters so that people can assume

responsibility for their own health;

4. Individual, community and national self-determination and self-reliance in

health matters;

5. The interdependence of individuals, communities and countries based on their

common concern for health;

6.

More equitable distribution of health resources within and among countries,

including their preferential allocation to those in greatest social need so that the

health system adequately covers all the population;

7.

Emphasis on preventive measures well-integrated it curative, rehabilitative and

environmental measures;

8. The pursuit of relevant bio-medical and health services research and the speedy

application of research findings;

9. The application of appropriate technology through well-defined health

programmes integrated into a country wide health system, based on primaiy

health care and incorporating the above concepts;

10. The social orientation of health workers of all categories to serve people and

their technical training to provide people with the service planned for them.

The Alma Ata Declaration, further states that atleast the following should be

included in the primary health care:

Education concerning primary health problems and the methods of preventing

and controlling them;

n

Promotion of food supply and proper nutrition;

ci

An adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation;

Maternal and child health care, including family planning;

11

Immunisation against the major infectious disease;

[i

Prevention and control of locally endemic diseases;

L!

Appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries; and ,

II

Provision of essential drugs.

To achieve this goal of Health for all by 2000, the role of the state is crucial in the

context of ensuring basic health standards.

The World Health Organisation Document on 4 Formulating Strategies for health

for all by the year 2OOO*5, lays down certain referral guidelines for formulating

national policies, strategies and plans of action in order to achieve successfully the

goal of Health for All by 2000. A perusal of the same in the light of those adopted by

us in this regard, may shed light on the aspects over-looked and may also help

assessing our present position.

,

To sum up the major points, a national plan of action has to be:

□

A inter-sectoral master plan, including the action to be taken in all sectors

involved, to give effect to the policy. It indicates what has to be done, who has to

do it, during what time frame, and with what resources. It is a framework

leading to more detailed programming, budgeting, implementation and

evaluation.

n

Each country has to develop its health policy as part of overall socio-economic

development policies, in the light of its own problems and possibilities,

particular circumstances, social and economic structures, and political and

administrative mechanisms.

□

Primary health care forms an integral part of the country’s health system, of

which it is the central function and main agent for delivering health care. It is

also an integral part of the overall social and economic development of the

community. For primary health care to succeed, it will require the support of the

rest of the health system and of other social and economic health sectors

concerned.

□

The introduction of strengthening of the development processed needed to attain

health for all, will require unequivocal political commitment. It will most likely

have to be set in motion by political decisions by the government as a whole,

permeating all sectors, at all levels throughout the country and not merely by

the ministry of health or the health sector alone.

□

The overall social goal of health for all has to be broken down into more concrete

social policies aimed at improvement of the quality of life and maximum health

benefits for all. If the gap between the ’haves’ and the ’have nots’ is to be

reduced within and among countries, there will be a need in most countries to

formulate and put into effect concrete measures for equitable distribution of

5 WHO, Geneva, 1979.

resources. In many countries, this wil] imply the preferential allocation Qf health

resources to those in greatest social need as an absolute prioritVi as a step

towards attaining total population coverage.

11

Measures have to be taken to ensure free and enlightened community

participation, so that notwithstanding the overall responsibilities of the

governments for the health of their people, individuals, families, and

communities assume greater responsibility for their own health and welfare,

including self care. This participation is not only desirable, it i$ a social,

economic and technical necessity.

11

In developing health strategies, each country will have to take into account its

cultural and social patterns and its political system.

The W.H.O also recognises that, most countries are dealing with all these

aspects of planning, but not in a systematic and inter-related manner. The initiation

of a more systematic process may start with any of the above-mentioned steps,

subsequently leading to the remaining step being carried out in a systematic and

interrelated manner. Thus, there could be many possible entry points to the country

health programming process.

^7

The National health Policy, 1983

As a signatory of the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978, the Government of India is

committed to taking steps to provide Health For All by 2000 AD. In 1983, the

National Health Policy which aims at achieving this goal by 2000 AD, laid down the

specific goals to be achieved by the year 2000 AD as:

1.

Reduction of infant mortality rate from the present level of 125( in 1978) to

below 60 in 2000 AD.

2. To raise the expectancy of life at birth from the present level of 52 years to 64 tjy

the year 2000AD.

3. To reduce the crude birth rate from the present level of 32 per 100 population to

21 per 1000 by the year 2000 AD.

4. To reduce the crude death rate from the present level of 12 per 1000 population

to 9 by the year 2000 AD.

5. To achieve a net reproduction rate of one by the year 2000AD.

The National Health Policy lays down specific goals to be realised by 1985, 1990 and

2000, such that by the year 2000, the above mentioned could be achieved. In 1983,

this Policy was evolved by the Ministry of Health and Family welfare and approved

by the parliament, and it was sought to be implemented through the sixth and