TEACHING AND TRAINING OF DEPARTMENTS IN MEDICAL COLLEGES

Item

- Title

- TEACHING AND TRAINING OF DEPARTMENTS IN MEDICAL COLLEGES

- extracted text

-

RF_MP_8_D_SUDHA

34 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

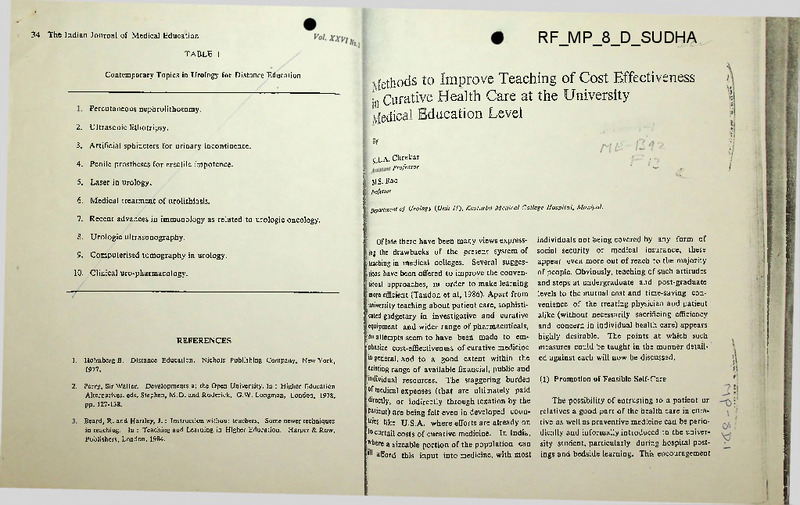

TABLE 1

Contemporary Topics in Urology for Distance Education

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

2.

Ultrasonic lithotripsy.

3.

Artificial sphincters for urinary incontinence.

4.

Penile prostheses for erectile impotence.

5.

Laser in urology.

6.

Medical treatment of urolithiasis.

7.

Recent advances in immunology as related to urologic oncology.

8.

Urologic ultrasonography.

9.

Computerised tomography in urology.

10.

Clinical uro-pharmacology.

\fethods to Improve Teaching of Cost Effectiveness

Jn Curative Health Care at the University

yfedical Education Level

*

K.L.A. Chrekar

.

'

Professor

J

M.s. Rao

jrtftssor

REFERENCES

1.

Holmberg B. Distance Education. Nichols Publishing Company, New York,

1977.

2.

Perry, Sir Waller. Developments at the Open University. In : Higher Education

Alternatives, eds. Stephen, M.D. and Roderick, G.W. Longman, London, 1978,

pp. 127-138.

Beard, R. and Hartley, J.: Instruction without teachers. Some newer techniques

in teaching. In : Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Harper & Row,

Publishers, London, 1984.

Apartment of Urology {Unit 11), Kasturba Medical College Hospital, Manipal.

' Of late there have been many views express: tag the drawbacks of the present system of

; (aching in medical colleges. Several sugges

tions have been offered to improve the conventional approaches, in order to make learning

'more efficient (Tandon et al, 1986). Apart from

university teaching about patient care, sophisti

cated gadgetary in investigative and curative

equipment and wider range of pharmacuticals,

;no attempts seem to have been made to em

phasize cost-effiectiveness of curative medicine

iio general, and to a good extent within the

existing range of available financial, public and

^individual resources. The staggering burden

°f medical expenses (that are ultimately paid

■directly, or indirectly through texation by the

Patient) are being felt even in developed coun

tries like U.S.A, where efforts are already on

to curtail costs of curative medicine. In India,

P'here a sizeable portion of the population can

’H afford this input into medicine, with most

individuals not being covered by any form of

social security or medical insurance, these

appear even more out of reach to the majority

of people. Obviously, teaching of such attitudes

and steps at undergraduate and post-graduate

levels to the mutual cost and time-saving con

venience of the treating physician and patient

alike (without necessarily sacrificing efficiency

and concern in individual health care) appears

highly desirable. The points at which such

measures could be taught in the manner detail

ed against each will now be discussed.

(1) Promotion of Feasible Self-Care

The possibility of entrusting to a patient or

relatives a good part of the health care in cura

tive as well as praventive medicine can be perio

dically and informally introduced to the univer

sity student, particularly during hospital post

ings and bedside learning. This encouragement

36

The Indian Journal of Medical Education

becomes important when facing disabling

or prolonged care problems like paraplegia and

urinary retention, poor control of bowel move

ments etc. after serious injuries to spine,

repeated urethral dilatations for stricture etc.

The patient or attendants could be taught to

pass a catheter up the urethra periodically to

drain the collected bladder urine, self-calibrate

the narrowed urethra in stricture cases, or

remove stool daily by insertion of a gloved

finger up the anus (Rao et al 1986). The

students specially require to be exposed to the

art of patient motivation and counselling rather

than to teaching attitudes under-estimating

the intelligence and willingness of the illiterate

patient group, for instance. Once learnt, the

patient or the attendant can perform these

manovers confidently under home conditions,

thereby cutting down on inpatient costs and

time usually taken up by chronic care nursing

problems alone. This would be far more effi

cient and less expensive on the long run than

indwelling catheter drainage for example.

Cancer, high blood pressure, heart and chest

disease patients could also be selected so that

considerable on us is transferable on an

individual basis to the patient or relatives for

home care.

(2) Promotion of Outpatient Curative Services

The next point at which cost effectiveness

could be taught is at the outpatient levels The

students can be instructed about proper sizingup of an individual patient’s clinical condition

and specific problems, allowing for his/her

selection for outpatient treatment in a sizable

number of cases, and consequent influence of

such attitudes on mutual patient and hospital

V°l-

Methods of Improve Teaching...37

costs, competition for limited hospita] v I

. jnformation from the treatment initially avoidable treatment failures. Short

etc. at such outpatient facility areas.

could be brought to the student’s term antibiotic therapy (e.g. 6 months instead

proportion of major and minor surged ■ '

This will help in bis or her adaption of former 18 months for pulmonary tuber

hernia repairs, circumcision, varico-ele^ culosis, single dose treatment for cystitis in

hydrocele operation, endoscopic pr0C£J? ■ "\us altered facility situations better in

'^■dividual career life. For example, ultra- woman etc.) combining both cost-effectiveness

etc. could then be performed without necesr

rapby at titnes could obviate need for and efficiency should be brought to trainee

ing patient admission (Kaye, 1985).

attention.

*^r radiological contrast studies.

Attention of the student could be w

Optimal utilisation of the available hospital

focussed on the increased number of such c>

If the patient presents to the institution

beds and personnal resources by minimization

multiple disease problems, emphasizing

that can be treated at similar cost with.

of post-treatment time at which point a given

given period than otherwise possible with ( the trainee or student group on priority to

patient could be sent out to be looked after at

conventional method of hospitalization [ iStttly investigate and treat the entity immehome (or as an outpatient), could be high

undergoing the same procedures. Refre£ i,iiely threatening to that individual patient

lighted during bedside posting of students,

course and continuing medical education p becomes important. The message of avoidance

particularly the post-graduates.

grammes could also be effectively used t ^increased costs from further compelled, proimpart this message of choosing patients!; feejed hospitalization for treatment of any

(4) Projection of cost inputs towards patient

ambulatory care thus achieving cost-effect. Fecmplications resulting from wrong priority

care facilities adjusted to individual student

Jtfflsiderations causing delay in timely attention

ness without sacrificing efficiency.

career concerns

|wald then be brought in. Priority of attention

rnr.nj

•

-

pecifl men uc uiuuguu

(3) Cost-Reduction During Invesigation, Trch the vital body system e.

e.g. head thorex over

ment and Hospitalization

wthers in a multiple trauma case is an example

A post-graduate student wishing to start his

own private hospital or joining a new group

>'fsuch teaching.

requires to be given guidelines as to the optimal

Carrying out of as many of the reqoS

investment with cost-effective relevance to his

investigations for a given case at an outpace! Teaching judicious selection and usage o

uu future working enviroment. Many students

level (except

canhas

bealso

inculcs:

'------ ’ for

■ emergencies)

sdniss

an equally important bearing on

Mthougu a wide range cof are under the impression that with progress of

and demonstrated to the students ascou [eon-effectiveness.

t____________ .Although

for treatment of medical sciences and .growth of specialities,

buting to reducing inpatient costs. Diagnes pharmaceuticals areavailable

----tests for a specific disease entity or patr Various ailments, the students require to be cau one will expect prompt increased investment

iMUBj antibiotics

aunuivuvo costs towards the ultimate laudable goal of

should never be a habitual ritual, but sh« ‘honed about drug abuse (e.g. tonics,

cost-ineffective

providing efficient care, at his rapid command

be organised in as logical an order as poS ‘etc.) which in turn can create a tv.™

——

demand. Disillusionment

with the goal to obtain the maximal infon & risky situation for physicians & patients a i e. and affordabiljty

of providing soon

such follows,

services as

is

tion from the minimal number of procei The futility of prolonged antibiotic prop y axis

(preferably arranging the non-invasive (for overuse of combinations of such drugs withbefore the invasive), taking care to avoid tlfiont detection and simultaneous correction of

which are merely confirmatory to that obt» often underlying basic surgically treatable inble by others. Similarly, selection of invest fective disease results in bacterial resistance, as

tions which are economical and feasible ,a consequence of which costlier and a more

given situation and at the same time

----- provi-l

T 10xic compounds are repeatedly and compellingly brought into play for combating such

. JU __ 1....1,....-nj;nnr«nnrresnf an

limited by the slowly expanding resources of any

h

-M:___--------------------- agency. The pinch

public

or private financing

of this problem is being felt even in developed

countries. Therefore the postgraduate student

needs to be informed about rapid, cheep and

easily conducted methods ot investigations but

yet of proven bulk accuracy e.g. dip slide or

38

The Indian Journal of Medical Education

strip test for bacteriurea before resorting to

urine culture (Rao et al, 1984). The latter

facilityin this instance could be reserved for

those few patients in which the rapid testing

is anticipated to be fallacious.

The art of sensing feasibility of acquiring

capital expenditure equipment for one’s own

facility by combining demands with other

professionals or departments could be intro

duced to the post-graduate student at a suit

able point of learning activity (e.g. C.T. scan

or ultrasonography with radiology, laser source

equipment sharing with Ophthalmology etc.).

Both justification for wide range of use and

hence optimal cost-effective utilization of the

Ko/new equipment

attitude.

is reinforced by

(5) ’‘Balanced” follow-up care

I

1

Uie Training and Utilization of Paramedics

ifl Health Services of Bangladesh

The students, during their outpatienl..I

ing, could be exposed to the art of f0||^f

care balancing between “no-concern” or “A By

concern” attitudes in regard to nutn^t

Barua

out-patient visits or frequency of investigftl; p.C.

ll'IIO fellow from Bangladesh.

towards the goal of mutual patient/hov

cost-effectiveness. The students should

B.V. Adkoli

given opportunity to observe consults ' Asitt. Prof, of Educational Technology.

(teaching staff) making use of the dictapfe

telephone or postal correspondence fadfc

B.T.T.C., Jipmer, Pondicherry.

to the maximal mutual convenience and ad<

efficiency of the patients and themselves.

ABSTRACT

REFERENCES

1.

Kaye, K.W. Outpatient urologic Surgery.

Lea & Febiger, U.S.A., 1985.

2.

Rao, M.S., Achrekar, K.L., Manon, C. and Srinivas, V.

Clean, Non-sterile, Araumatic, Intermittent Catheterisation : Suitability under

Indian conditions for Short & Long-term, Urinary Retention Problems Antiseptic

83 : 179 ; 183 ; 1986.

3.

4.

The developing countries like Bangladesh are facing the challenge of providing

need based health services to a large population at a limited cost. Thus develop

ment of appropriate training programmes for different kinds of auxiliary health

personnel assumes great significance in the light of the countries’ commitment to

provide HFA by 2000 AD through primary health care approach. An attempt has

been made to examine the present situation and outline the curriculum of various

paramedical courses which provide basic support to the health care delivery in

Bangladesh.

Ind. J. Surg. 46 : 134-137 ; 1984.

One of the greatest challenges before the developing countries has been to develop cost

effective health services system according to the needs and requirements of the community.

Bangladesh is also committed to the goal of providing Health for All by 2000 A.D. through

Primary Health Care. As rightly emphasized by W.H.O., the development of appropriate

educational strategies has been considered to be the most important factors towards realization

Tandon, S.P., Vaidyanathan. S., Rao, M.S., and Natarajan. V. :

of this ambitious goal.

Rao, M.S., Agarwal. K.C., Vaidyanthan, S., et al Evaluation of a rapid screening

test for detection of bacteriuria in the urological outpatient service.

Application of Mastery concept of Urological Training of M.S. General Surgery

Postgraduate students

Ind. J. Urol. 2 : 76-78 ; 1986.

There is no unique model of training programme for particular health workers in the

developing countries. The approach to the problem should be independently explored by

each country in accordance with the local characteristics, needs and resources. The key word

[he Need for a Rose—(Re-orientation of

Surgical Education)

S.

Ananthakrishnan

Associate Professor of Surgery

hellfiirla/lnstitute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Pondicherry.

ABSTRACT

The current status of undergraduate training in surgery is largely unsatisfactory.

This article analyses the job requirements of undergraduates and the objectives of

surgical training. Lacunae in the existing system are focussed and suggestions are

made for ensuring considerable improvement, without the need for major additional

resources.

The Government of India has rightly appro

ved the need for a reorientation of medical

iucation in this country to make it more

Levant to conditions existing here and thus

hsborn the ROME scheme in 1977. Although

-c primary aim of this scheme was to ensure

stive involvement of the Medical College in

immunity Health problems and in direct

-livery of Health Care Service to the rural

’Pulation, the functioning in practice of the

•jeme has been largely unsatisfactory with

: ’-implied reorientation of medical education

V forthcoming satisfactorily.

The aim of the current presentation is to

- ”nt out certain gross deficiencies as noticed

by the author in the training of the under

graduate in the discipline of surgery and to

suggest remedial measures, within the existing

system keeping in mind the specific objectives

of the ROME scheme.

Task Analysis

An analysis of the job requirements of a

fresh undergraduate on completing bis training

reveals the need for him to function in one of

several roles, viz.

(i)

as a doctor working at the PHC,

(ii)

in private practice,

42

The Indian Journal of Medical Education

(iii)

(vi)

a general duty medical officer in central

or state governments, autonomous or

private undertakings,

Vol. XXVI No. 3 !

(b)

involved in surgical management and

(i)

in taluk or district level hospitals,

(c)

(v)

as a postgraduate student,

(vi)

in teaching institutions and in

(d)

(vii)

other areas (migration abroad etc.).

be an active participant in national

programmes. The list is obviously in

complete and can be improved. /

recognise the nitural anxiety in patients]

and relatives -.-.garding surgical pro-!

cedures and c-.unsel them regarding Current Training Programme

the various indications of surgery,

Keeping in mind the job requirements and

objectives of undergraduate surgical training

to recognise, r»zord and appropriately

enunciated above it is obvious that the current

treat where feasible or refer where

system falls far short of the requirement.

required, Medi-zj-Legal situations met j

within day to cay practice.

Surgical education as at present carried out,

prepares him primarily only to function in a

transient role as a continuum to further post

graduation and does not lay enough stress on

other aspects to enable him to perform satis

factorily in the other roleimentioned earlier.

This lacunae continues to exist side by side

with the recommendations of the Medical

Council of India regarding undergraduate

medical education (MCI, 1977), a document

which in itself is quite vague.

.X

(e)

(f)

/ Objectives

The aim of training in surgery is to ensure

that the fresh graduate is able to :

(a) diagnose, order relevant and feasible

investigations and treat common simple

surgical ailments,

(g)

The Need for a Rose.. 43

Sept.-Dec. 1987

recognise anc refer appropriately

optimum time those surgical ailments]

which requit-, management at spec-1

ialised'centres,

I

to perform baeic and simple surgical

procedures commensurate with his

training and the facilities available e.g.

suturing of wounds, drainage of absces

ses, biopsies, minor operations etc.

I

The lacunae in the current system can be

listed as follows :

recognise that surgical intervention is j

but one aspect and probably a minw

one at that in the management of Pa' I

tients and therefore be aware of th' j

indications, contraindications and liHU'-;

tations of surgery,

(i) over-emphasis on rarer and more major

problems to the detriment of the

common surgical ailments seen at the

OPD,

(ii)

lack of adequate training on the impli

cations of surgery, and on the impor

tance of pre and postoperative manage

ment,

(iii)

total lack of contact with medico-legal

problems during the entire period of

surgical training as this aspect is left to

the department of forensic medicine,

(iv)

total lack of continuous contact, either

to provide first aid in appropriate situa-|

tions, and advise regarding transport j

with the patients or the relatives and

therefore an inability to appreciate the

anxieties and implications of surgery,

(v) minimal contact if at all with emer

gency surgical problems as the entire

duration of surgical posting is spent in

demonstrating ‘cold’ cases and the

students are available with the depart

ment for only a limited time,

(vi) minimal contact with actual operative

surgery. The last two are left generally

to be covered only during the short

interniship period in surgery and are

considered of no consequence to the

undergraduate surgical trainee,

(vii)

a total ignorance in the undergraduate

of the differences in facilities which are

likely to exist between teaching insti

tutions and areas where he may actual

ly have to perform as in PHCs etc.

This is a very important aspect and is

probably partly responsible for the

fresh graduate being reluctant to work

outside major teaching hospitals.

(viii)

complete avoidance of any training in

the effective domain with forms a very

significant part of the Doctor-Patient

relationship in surgery (Ananthakrishnan, 1981).

(ix)

no mention of the ethical implications

patients to major centres if required,

(h)

be aware

of the ethical principle*

44

The Indian Journal of Medical Education

Ko/. XXVI No. 3

of surgery—an area where the under

graduate is left in blissful ignorance.

an exercise is now being undertaken at JIPMER

which falls in the jurisdiction of the Central

University of Pondicherry.

Seasons for the Lacunae

In order to develop proper attitudes it is

necessary that continuous contact is encouraged

The reasons for the existing state of unsatis

between patients and their relatives and stu

factory affairs is obvious. Surgical training to

dents. It is necessary, therefore, to allot more

the undergraduate is at present considered as

responsibility to students, make them more

only the first step in the continuum progressing

active members of the team and encourage

from undergraduation to internship, to resi

them to actively involve themselves in the

dency, to postgraduation and to senior resi

diagnosis, investigations, management and

dency without really preparing him for fulfilling

follow up of patients allotted to them.

job requirements after graduation, were he to

so chose or be forced to do so, keeping in mind

the greater and greater difficulty in getting

Students must also be encouraged either

admission to post-graduate courses. Needless voluntarily or by compulsion if required to

to say an eight week pre-registration internship visit the wards and the casualty beyond work

period cannot compensate for the time lost ing hours to enable them to acquire some

during the entire three clincial years posting in knowledge regarding emergencies which usually

surgery.

tend to arrive after working hours. In the

final year, students allotted to individual units

must work full time with that unit for this

Suggestions for Improvement

purpose as is now being done only for the

department of obstetrics.

Keeping in mind the task analysis of the

fresh graduate and the objectives of training in

surgery it is necessary to completely recast the

curriculum of the undergraduate course in

surgery. However, this expectation is likely to

remain unfulfilled in view of known constraints.

The curriculum should be need based with

greater emphasis on common problems and

practical training rather than theoretical know

ledge. It should also ensure familiarity of the

trainee with facilities existing at the periphery

as opposed to major teaching institutions. Such

Undergraduates must be encouraged to

wash up and thus ‘passively’ assist operative

procedures especially those of a minor nature

like drainage of abscesses removal of lipomas,

cysts, biopsies, hydroceles, hernias etc. Active

involvement in this fashion is more likely to

evolve interest than mere observation as on

lookers.

The ROME scheme demands that a suitable

Sept-Dec. 1987

The Need for a Rose...45

More emphasis is to be paid in training

•me table be worked out by medical colleges

or posting of undergraduate students to Dis- both the undergraduate and the intern in

principles

of operative surgery. Details regard

rict Hospitals, Taluk Hospitals, subdivisional

jvel hospitals and PHCs for not less than 8 ing this have been discussed elsewhere and

will,

therefore,

require no repetition (Ananthareeks. Undergraduates posted in individual

•nits must therefore be encouraged to visit krishnan, 1984). It is necessary at all points

of training to ensure that the undergraduate

?HCs and peripheral hospitals in the vans pro,ided with the ROME scheme along with their understands the relevance of the training pro

:ef?ective surgical specialists. This will give cedure and the need for his active and useful

•hem an idea of the prevalence of actual surgi participation.

cal problems seen at the periphery as opposed

Co teaching hospitals and also give them an

dea regarding facilities likely to be available at

Teaching must be more problem oriented

Che periphery. Seeing consultants perform rather than subject based and appropriate

minor procedures under these conditions is like- efforts must be made to ensure this.

!|y to give them confidence to be able to do so

themselves.

| As is required for the interns in some insti

llations, undergraduates also should be required

to maintain diaries appropriately formulated to

ensure adequate participation on their part in

the activities mentioned earlier.

In conclusion, it appears that considerable

scope exists in improving undergraduate train

ing in the discipline of surgery and much can

be achieved in terms of results with negligible

or minimal additional resources.

46

The Indian Journal of Medical Education

Ko/. XXVI No.

REFERENCES

1. Ananthakrishnan, N. Doctor-Patient relationship—The neglected domain of

medical education. Indian Journal of Medical Education, 20-1-1981.

2. Ananthakrishnan, N. Is training for undergraduate medical students in opera

tive surgery adequate. Indian Journal of Medical Education, 23-1-1984.

3.

Medical Council of India—Recommendations on Undergraduate

Education. Medical Council of India, 1977, page 14.

4.

Rc-orientation of Medical Education (ROME) scheme—Background information,

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Department of Health) ME (Policy

Desk), 1977.

Medical

Survey of Existing Conditions in Dental

Departments of Medical Colleges in India

By

J. R. Sofat

Professor & Head of Deptt. of Dentistry,

(Mrs.) R- Sofat

Professor of Gynaecology & Obstetrics,

Dayanand Medical College, Ludhiana.

Dental departments of medical colleges are

in a state of evolution and are being ration

alised. Much has already been done to align

them in their due perspective but a lot yet

remains to be fulfilled. The standard regard

ing the staff members, their qualifications,

basic equipments, 'leds alloted to these depart

ments and teaching schedules differs from

place to place. Ttie Medical Council of India

(MCI) has prescribed some guidelines, but

these are either vague or not followed

uniformly. Since the inspecting teams have

no dental experts the setup of dental depart

ments is ignored altogether.1

Keeping these shortcomings and variations

in mind a survey was planned to assess the

salient features of the dental departments of

all the medical colleges of the country. The

heads of dental departments of all 1C6 medical

colleges were posted self-addressed and

stamped proformas to be filled and returned

to us. Thirty five replies were received in the

first instance. The request was repeated in

the same way to the remaining 71 medical

colleges after a gap of two months. Eighteen

tttore replies were received making a total of

53 replies out of 106 medical colleges i. e. a

50% response, which has been analysed and

reproduced below. Out of 53 responses, 5J

were from the dental departments of medical

colleges and 3 were from dental colleges/dental

wings looking after the dental needs of these

three medical colleges,

1.

TeachingMCI boolet2 recommends

15 days posting of three hours a day in

the department of dentistry in II MBBS,

1st and 3rd term.

The number of medical students

admitted to the 53 medical colleges

ranged from 50 to 200. On analysis of

data it was found that no dental teach

ing was done at one medical college, no

theory classes were taken at another two

medical colleges while in the rest of the

50 medical colleges both theory classes

and clinical demonstrations were taken.

The theory lectures of mostly 60 minutes

duration ranged between 4 to 30 and

these were conducted in 1st Profession

at 1 college, in 2nd Profession at 19

colleges and in 3rd Profession at

“ Volume XXIII No. 3 I

76 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

30 colleges. The clinical demonstration

of mostly 3 hours’ duration ranged

between 10 to 30 and these were con

ducted in 1st Profession at 5 colleges, in

2nd Profession at 29 colleges and in 3rd

Profession at 18 colleges.

2.

Examination in Dentistry :—MCI book

let2 recommends to include dental

diseases in Surgery paper II.

3.

4.

Considering only 50 dental depart

ments of medical colleges, the dental

departments were he'ded by Professors

at 23 places, Associate Professors/

Readers at 18 places Assistant Pro

fessors at 2 places, Lecturers at 6 plaees

and a Registrar at 1 place This showed

that MCI recommendation was flouted

at 9 places. There were 8 dental

surgeons/dental assistant surgeons in 7

medical colleges and obviously they

carried no teaching designations. There

Dental Radiographer :—One each was

available only at four places.

Though the staff recommendation

in dental" departments by MCI is barer

minimal, yet there were only 25 medical I

colleges where staff strength was accord

ing to its directive.

IV.

Sweepers

At least one sweeper was

available at every place, though he was

part-time at many places.

V.

Clerks cum Typists cum Receptionists:One each was available at 23 places

only,

{■/"

VI.

Nurses

24 Nurses were available at

18 places.

VII.

Pharmacists :—One each was available

at 2 places.

VIII,

Ward Boys/Ayas/M.N A.’s/Attendants/

Luscars :—30 of these were available

at 19 places.

One medical college admitting 100

students annually had only one teaching!

staff member with B. D. S. qualifications

and designated as lecturer, while another

medical college with 125 admissions was

headed by a graduate Registrar. Another

two medical colleges admitting 150

students had only two staff members

each with lecturers as heads at both the

places. Another medical college admit

ting 50 students annually had only one

teacher as a Professor.

Medical Interns :—They were posted in

dental departments only at 12 medical

colleges.

Teaching Staff :—MCI booklet recom

mends,3 1 Professor/Associate professor/

Reader, 1 Assistant piofessor/lecturer

and 1 Demonstrator for 100 annual

admissions of medical students.

IH.

Some glaring discrepancies were as I

under :—

On analysis of data, no question on

dental diseases ever appeared in theory

paper of Surgery or any other subject at

22 medical colleges while at 31 medical

colleges only one question or a short

note appeared.

5.

Survey of Existing Conditions 77

September-December 1984

were 36 house-surgeons in 21 medical

colleges only.

Dental Auxiliary StaffMCI booklet’

prescribes four dental technicians and

one store keeper-cum-clerk for 100

annual admissions in M. B, B. S. course.

The analysis of 53 dental depart

ments showed the availability of follow

ing auxiliary dental staff

I.

Dental Technicians :—A total of 61

dental technicians were available at

40 places.

II.

Dental HygienistsA total of 35

dental hygienists were employed at 24

places.

IX.

Chairside Assistants

able at 14 places.

(with 2 dentists) had a single auxiliary

staff in the form of 1 clerk, 1 clerk, 1

chairside assistant, 1 nurse, 1 techni

cian, 1 technician and 1 technician

respectively besides the assistance of a

sweeper at each place.

6.

Dental Casualty Service :—No dental

casualty services existed at 13 places out

of 53. At 34 places, a dentist was called

only when needed. Only at the remain

ing 6 places dental casualty services were

available round the clock on 8-hourIy

staff rotation duty. A dental unit/chair

was available only at 7 places of casualty

service while dental beds were reserved

only at three places in a number of 1, 2

and 2 respectively.

7.

Dental Ward

No beds were available

for dental department at 5 places, while

at other places the bed allotment varied

between 2 and 20 with an average of 6

beds at a place. At 22 places, the beds

were under the independent charge of

heads of dental departments thouah they

did not seem to have sufficient subordi

nate staff, like registrars/house surgeons/

nurses to look after these neds. At other

26 places these dental beds were placed

in the wards of Surgery (14 places),

E. N. T. (6 places), Medical (2 places).

Orthopaedics (I place), Skin (1 place)

and miscellaneous (2 places).

37 were avail

There was hardly a place where

’auxiliary staff was sufficient either

according to the directions of the MCI

or according to the desirability.

Some glaring discrepancies were

as under :—

One place admitting 100 students

annually and with 2 dentists in position

had no auxiliaries whatsoever. The

following places admitting 155 students

(with 5 dentists), 70 students (with 4

dentists), 125 students (with 4 dentists)

120 students (with 3 dentists) 145

students (with 2 dentists), 100 students

(with 2 dentists) and 100 students

8.

Equipment : —

a)

Dental Chairs and units needed in

dental departments were based on

the total number of dentists which

78 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

was 190 including 35 house surgeons

in 50 medical colleges. The number

or dental chairs and units was ade

quate everywhere except at 11 places

where these were deficient.

b)

c)

d)

e)

f)

Dental X-Ray Units:—These were

available at 38 places and there were

no X-Rav Units nt 15 places. At

28 places there was one X-Ray

plant each, at 6 places 2 X-Ray

plants each and at 4 places 3 X-Ray

plants each were avaik-.ble,

Volume XXIII A’o. J

motors, boyie’s apparatus and

amalgamator was available at only

one place each.

9.

Operation. Theatre with General Anaes-j

thesia ;—This facility was available at I

fixed times (mostly once a week) at 34

laces while 19 places had no such

facility.

10.

Post-Graduation :—Post-graduation was

available at 5 medical colleges. Four I

medical colleges had the facility of post

graduation in the specialities of Ortho

dontia, Public

Health

Dentistry,

Operative Dentistry and Oral Surgeryone at each place, while one medical I

college had post-graduation in two I

specialities i. e. Prosthetics and Oral >

Surgery.

Airotors 1—One or more were avail

able at 25 places. At 11 places there

was one airotor each, at 6 places 2

each, at 7 places 3 each and at one

place 6 ol these were available.

Ultrasonic Scalers

One or more

were available at 19 places. At 13

places there was one each, at 3

places 2 each, at 1 place 3, at

another place 4 and still another

place 5 were available.

Dental Laboratories

Dental labo

ratories for prosthetic and maxillo

facial piosthesis work were available

only at 29 places while we bad 67

dental technicians at 40 place out of

53 places. This showed that these

technically qualified people were

being used elsewhere.

Special EquipmentSpecial equip

ment like casting facility was avail

able at three places while cryosur

gery, endobox. diathermy, micro-

11.

Community Dental Clinics :—Community

dental service, either urban or rural,

outside the medical college campus was

available at 15 places out of 53.

12.

Commrnts/Suggcstions of Head of Dental

Departments :—Most of the heads of

dental departments had responded with

following comments/suggestions :—

I.

Present State

Detal departments

are in a bad shape and a lot of

improvement is needed for their

growth and development. Medical

Council of India and Dental Council

of India should be apprised of the

situation and requested for remedial

measures.

September-December

II.

III.

IV.

Survey of Existing Conditions 79

1984

Beds, Casualty and General Anaes

thesia Service :—At least 10 beds

under the head of dental department

and 2 days a week of general anaes

thesia service in the operation theatre

should be available for the dental

department. Adequate junior dental

staff and nursing staff should be pro

vided to look after the admitted

patients and also to look after the

casualty service. A dental unit,chair

should be provided in the casualty

centre.

Regional Repair Workshop :—There is

difficulty in getting the repairs,service

of the equipment. Regional workshops

are suggested at the de,ital/medical

colleges for this purpose.

Dental Specialities Staff and Regional

Ref rral Centres : —Many have

complained of such inadequate staff

that even the treatment of staff

and students of the medical college

could not be carried out satisfactorily

besides the commitment of teaching

and research. Dentul departments

should be uplifted in such a way that

these can have the facilities of all

specialities so that these departments

can render tl e specialised dental ser

vices rather than the present general

dentistry. There should be a minimum

of 5 post-graduates, one each in the

specialities of Oral Surgery, Perio

dontia, Prosthetics, Orthodontia and

Pedodontia/Operative Dentistry for

50 annual M. B. B. S. admissions. If

the number of admissions is more.

these specialists can have their own

sections with an assistant like registrar/

demonstrator and a house surgeon

accordingly. Once all specialists are

there, these deatal departments can

work as regional referral centres for

the patients of the area.

V.

Auxiliary Staff : —At least two dental

technicians, 2 hygienists, 1 radio

grapher. 2 receptionists/typists/chit

clerks, chairside assistants equal to

the number of dentists nnd 1 whole

time sweeper should be there for 50

MBBS admissions.

VI.

Curriculum ;—A uniform pattern is

needed so that medicos are given

adequate knowledge.

VII.

Examination in Dentistry; —For want

of examination in dentistry, attendance

in classes is erratic. Surgery paper

should carry at least one part with

three questions on dental diseases and

the head of dental department should

be the examiner for this part.

VIII.

Finances :—There should be suitable

annual budget for dental departments

for the purchase of equipment, drugs

and materials.

IX.

Post-Graduation

Post-graduation

should be allowed in the speciality

where the conditions laid down by the

authorities can be fulfilled, so that the

teachers in the medical colleges can

persue an active interest in their

specialities.

Survey of Existing Conditions 81

SO The Indian Journal of Medical Education

^^’uhune XXIII No

3

September-December 1984

references

X.

Attitude of Authorities : —Many have

complained of the callous attitude of

the authorities and they must be made

to wake up. The recommendations

of the MCI should be mandatory and

nothing should be left to the local

authorities. The inspection of dental

departments should be carried out by

dental inspectors and not by medical

inspectors who themselves know very'

little about the dental setup.

XI.

All India Annual Meet;—All the

teachers or at least heads of dental

departments must meet at least once

a year so that they can discuss about

their common interests and problems.

An all India body of dental teachers

of medical colleges is desired to be

formed.

XII.

Social and Preventive Measures: —

Social and Preventive dental measures

should be the responsibility of these

dental departments. Fluoridation and

defluoridation of water programme

which is a social health measure

should be got carried out by the heads

of these departments.

Discussion '■—"The basic objective of dental

departments of medical colleges is teaching of

dentistry to MBBS students, research, dental

and maxillofacial treatment of both outdoor

and indoor patients and help in the preven

tion of dental disease. All this is possible

only if we have sufficient staff, auxiliaries,

equipment, accomodation, beds, materials,

cooperation of concerned authorities and pro

per guidelines. Owing to the magnitude of

dental disease in the country, paucity of dental

manpower and urgent need for prevention, it

is all the more important that the dental

departments of medical colleges be well

organized. All clinical specialities have to be

developed so that these departments become

the centres of. referrals. If the graduate

medicos must have the working knowledge of

dentistry the curriculum should be laid down

and students be examined in the subject.

Dentistry should not be isolated as an outside

subject but should be considered as an integral

part of the other body systems. The existing

state of these dental departments is at such a

low ebb that no justice is being done to any

of the objectives of the department. It is high

time a committee of experts from these

departments is formed by the concerned

authorities so that available facilities are

reviewed and suitable recommendations are

made.

Summary :—Existing conditions in dental

departments of 53 medical colleges out of 106

in the country have been surveyed and analysed

in respect of teaching facililies, staff, casualty

service, dental beds, equipment, operation

theatre facilities under G. A., post-graduation

and community dental services. There are

many deficiencies in almost all the categories.

Comments of heads of dental departments

have also been reportad. Most of them feel

strongly about the need to reorganise these

departments.

Acknowledgement:—We are grateful to

heads of dental departments in various

medical colleges who responded to our questionaire. Our thanks are also due to our

Principal, Dr. N. Dube, for all his help,

guidance and permission to conduct this

study.

1.

Sofat, J. R. : Dental Departments of Medical Colleges for Teaching M. B. B. S.,

Indian Journal of Medical Education XXH, No. 3 : 12, 1983.

2.

MCI Booklet : Recommendations on Undergraduate Medical Education; P 17, 23,

April, 1977 corrected upto Feb., 1980,

Volume XXIll No. 1

22 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

TABLE

111

•

Is Trainin^)f Undergraduate Medical Students

in Operative Surgery Adequate ?

Percentages of Correct Responses in Therapeutic Nutrition Statements

Graduate

N=190

Post-graduate

' N = 67

Diploma Holders

N=23

By

N: Ananthakrishnan

Peptic ulcer

59

60

71

Kidney diseases

47

52

67

.■’

Diarrhoea

73

71

Anaemia

62

65

77

Fever

64

76

77

59

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Pondicherry.

75

Liver Disease

53

47

Heart Disease

67

71

80

Diabetes

32

32

45

ABSTRACT

The current procedure for practical training of the undergraduate student in

surgery is grossly inadequate. The deficiencies of the existing system have been mentioned:

Clear and concise objectives are suggested as also changes in the existing training

methodology which would ensure better training and a better utilisation of the available

time of without adding to the curriculum eliminating at the same time the impartment

knowledge outside the purview of the MBBS doctor.

: Introduction

TABLE IV

Values Obtained on Chi Squere Test

Graduate and

Post-graduate

Graduate and

diploma holders

Post-graduate

and diploma

holders

n.s

3.161

2.662

Kidney Diseases

n.s

8.143

4.661

Diarrhoea

n.s

n.s

n.s

Anaemia

n.s

5.30*

3.501

Fever

Liver Diseases

3.421

n.s

4.04s

n.s

n.s

2.881

Heart Diseases

n.s

4.3 24

2.182

Diabetes

n.s

3.561

3.561

) Peptic Ulcer

.

Mark Ravitch of Pittsburg, USA, interna( tionally known surgeon, editor, historian and

I linguist is quoted as having stated that when

an editiorial or an article begins with a ques| tion (as this one does), the answer is always no

(Hardy, 1983). The question raised in this

article is very pertinent currently as different

universities tend to adopt widely divergent

approaches to this problem.

.

The Medical Council of India in its recomJ mendations

on

Undergraduate Medical

I Education merely states that the course of

| training in surgery including orthopedics

I should necessarily involve

I

(a) Practical instruction in minor surgical

■ techniques inculding first aid and

(b) A course of practical instruction in

common operative techniques including decom| pression, bandaging, splintings plaster etc.

'

Significant 1 at 0 10% lev I, 2 at 0.20% level,

3 at 0.01% level, 4 at 0 05% level,

The recommendations (MCI, 1977) do

mention that to achieve the above aims the

candidate should have one month clinical

clerkship in the casualty and emergency

services besides outpatient and inpatient train

ing in surgery. No definite guidelines are

available regarding the content of the course of

training in operative surgery of the methods to

be adopted in achieving the objectives of

training in that field.

Existing system

In the absence of any fixed guidelines and

well defined objectives, it is not surprising that

there is a wide variation in teaching the so

called “operative surgery” to underguaduates.

In some universities as in the university of

Madras, the subject assumes great importance

in view of the marked weightage given to

operative surgery in the viva part of the

examination in general surgery for the final

MBBS. Candidates have to undergo a seties of

—q

'

,24 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

Volume XXIII No.

1

'lectures on operative techniques of “Com agreement on the objMR/es and how to achieve

monly” performed surgical procedures in the them.

final year of the undergraduate training. The

It cannot be gainsaid that the aims of the

course usually consists of a series of theoretical

practical training in surgery should include

discussions on the indications, contraindica / (a) a knowledge of resuscitative procedures,

tions and procedures for performing various

first aid, splinting, treatment of abscesses,

surgical operations, supplemented by a short

sutures of wounds etc.

and variable period of observation of actual

operations in the operating rooms. In view of

(b) a familiarity with principles of surgery

the large numbers of students involved and the especially an ability to decide

limited period available for surgery in the final

(i) What to operate-i.e. the simple proced

year, this latter period of observation has

ures which an MBBS graduate can

necessarily to be extremely curtailed in scope,

safely be expected to perform in his day

duration and content. Demonstrations of some

to day practice,

of the operative procedures in cadavers is no

(ii) when to operate as a necessary

longer current primarily due to the shortage of

corollary of the above and

cadavers but also due to difficulty of any

worthwhile operative surgery demonstration on

(iii) most important of all which patients to

preserved bodies.

refer for surgery elsewhere. All these

three factors would imply in addition a

It is not surprising that in view of the above,

knowledge of emergency care, again

student compliance is minimal or nil and

that alone which is within the purview

the course is usually accepted as an unavoida

.--‘r of an MBBS graduate.

ble encumbrance with students taking recourse/-;to memorising a series of operations immedia-' /The course cf training should not include

tely prior to their examination in order to any reference to procedures which would be

satisfy the examiners.

outside the scope of a graduate doctor practis

ing in the usual environment in the country.

The lectures involve large groups of

students without in most cases even the facili

The list therefore should be curtailed to the

ties of Audio-visual aids.

Most of the barest minimum keeping in mind the above

operations described have not been even seen requirements. A list of procedures, knowledge

by the students and the instruments shown are of which could be considered absolutely essen

sometimes archaic and those not commonly tial for undergraduates is given below ;

used.

(a) sutures of wounds, drainage of

abscesses ;

Framing of objectives

Tn view of the lacunae, pointed out above,

it is necessary that strict and observable

guidelines are framed if necesseary by the MCI,

so that students, faculty and examiners are in

(b) tetanus prophylaxis

debridement ;

including wound

(c) venesection and establishment of a safe

and effective l.V. line ;

January-April

(d)

198

tracheostJ^ and emergency care of

obstructed- airway including principles

of airway maintainance in the seriously

ill patients;

(e)

emergency treatment and splinting of

common fractures ;.

(f)

treatment of common perianal condi-,

tions like fissures and piles ;

(g)

recognition of threatened or existing

intracranial hematoma and ? burr hole

exploration ;

(h)

recognition of intraabdominal emergen

cies and the need for referral to .

appropriate centres etc ;

(i)

minor operative procedures like vasec

tomy, circumcision, hydrocelectomy ? .

etc.;

More complicated procedures like herniorr

haphy, gastrjjejunostomy, appendicectomy etc.

which are often taught to the undergraduates

would really be outside their scope.

Is Training of Undergraduate 25

(ii) Training in “practical” surgery should

mainly be in the final year when an

adequate theoretical background would

already be present.

''(iii) There should be no need for formal

lectures with their inherent and well

recognised disadvantages.

(iv) Although the

disadvantages of

cadaveric demonstration are well

known and have been mentioned

earlier there might still be a limited

role for recourse to them for demons

trating procedures like, endotrachea]

intubation, tracheostomy etc.

(v) Finally, the most essential and most I

important part of practical surgical

training would entail a radical '

change in the schedule of undergra- 1

duate posting in surgery.

(a) The students in batches should be posted

full time in the various surgical units as is

being done currently for obstetrics during the

entire period of their final year posting in

A knowledge of the use of common general surgery. This naturally would include i

intruments would ofcourse be part of training out patient and inpatient training with the res

in the relevant procedures,

pective units, attending minor and major operative surgical sessions and also an exposure to

Methodology of training

emergencies with the concerned units on their .

With well defined and clear objectives, the emergency days. This constant exposure for 8

’ framing of a training schedule becomes very weeks would give an adequate opportunity of

much simpler and necessarily becomes more familiarising themselves with most of the ‘

need oriented. The suggested scheme is procedures mentioned earlier on the spot as it

elaborated below :

were, without need for theoretical classes.Since full time posting is already current in the

(i) The disproportionate credit given to

labour ward its adoption for other disciplines

operative surgery in the final MBBS should pose no problems. Since surgical

examination should be dispensed with management is a continuous process, constant

thus eliminating the need to memorise

exposure would ensure optium utilisation of the

and repeat little understood procedures. available period, besides fulfilling the needs of

26 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

Volume XXIII_No±. 1

article, the answer ^Be again as suggested by

“ essential.” practial training. Needless to say,

this would also ensure a sound basis for the Revitch is “no”. The training is certainly

post final examination, pre-registratiop. intern •defective but these deficiencies are largely

correctible if definite objectives are framed and

ship programme. ,

minor changes instituted in the training

To return, therefore, to the title of this programme.

REFERENCES

Hardy J.D. Is (almost) All Cancer Environmental. World J, Surg., 7: 176, 1983.

Medical Council of India—Recommendations on Undergraduate Medical Edu

cation—Adopted by the Medical Council of India, April 197 , page 14.

: jTJHe , ^2-^-.

VOLUME XXII Ho 1

50 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

\

What are the financial resources for Health 2000

Low

Income

China

1978

esti

mates

Upper

Middle

Income

Lower

Middle

Income

Higher

Income

z , Hc^-j

Z

■

6"/ -

L

.

•

Education of Undergraduate Medical Students

In Radiology*

By

S. Chawla

39

Number of

Countries

Average annual

300\

per capita income (USS)

1330

Population in

1976 (million)

1

28

28

17

400

300-700

, 1000—2500

3450

930

244

378

79

P. Panag

480

270

And

Principal and Medical Superientendent,

Lady Hardinge Medical College & Associated Hospitals,

New Delhi and Professor of Radiology,

University of Delhi,

Assistant Professor,

GNP in 1976

(5 billion)

220

372

170.6

% GNP allocated

for health,

public sector

0.77

0.78

0.64

Average per

capita health

expenditure

1.2

3.1

4.5

Total health

expenditure

S billion

(public sector)

1.7

2.9

1.1

4.8

2.7

Total estimated

private health

expenditure

$ (billion)

6.8

4.4

19.2

10.8

Total estimated

public+private

health expenditure

(S billion)

8.5

Not

known

5.5

24.0

13.5

Estimated ‘Abso

lute poor' %

45

—

15

8

5

S. Bhardwaj

Associate Professor,

Lady Hardinge Medical College,

New Delhi

ABSTRACT

Source : World Health Forum 1981 Vol. 2 No. 1, Lee M Howard.

Knowledge of radiology is essential for practice of medicine, hence it must

form an integral part of undergraduate training. The students at this level

do not need exposure to the details of specialised radiological techniques.

However, training in underlying piinciplcs, importance, judicious usage and

limitations of radiological procedures is essential. The curriculum content

can be rationalised to ensure coverage of appropriate topics. Integration

of teaching in radiology with pre-clinical, para-clinical and clinical subjects

would be the most effective methods of training. This could be achieved by

including discussions and demonstrations of radiographs and slides etc.

with the body systems taught in these disciplines The faculty from the

department of radfology if and when possible could be directly involved in

these teaching sessions. During the clinical period, attachment of small

groups of students to the department of radiology would be very useful.

The students could observe and participate in the routine procedures being

carried out in the department./

• Based on background paper prepared for a meeting oj the international cemmisshn on Radiological Education

held m Barbados in November, 1982.

52 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

The graduate in medicine is not expected to

be a specialist in radiology but he or she is

expected to have some knowledge about the

modalities of imaging so that he can practice

medicine effectively.

In brief, the educational obj.-ctives for

education of undergraduate medical students

in radiology should be as under:-

'GLUME XXII No 2

it would be worthwhile to delete some topics

which are of less practical importance from

various subjects and the time thus saved could

be effectively utilised for giving mote clinical

training, more emphasis on behavioural

sciences, paediatrics medicine and diagnostic

radiologv. How to achieve the objectives laid

down above ?

Probably the best method would be to

The graduates should know the physical integrate radiology with other subjects. •

principles underlying all imaging techniques

In the pre-clinical years, teaching of

including radiologv, ultrasound, CAT and

special

procedures including contrast anatomy and physiology can be supplemented

by appropriate radiographs showing the normal

examinations

skeletal system, card io-vascular system, gastroin

2.

Some understanding of the biological effects

testinal tract, the vascular system and the bron

of radiation, radiation protection and adverse

chial tree etc. Normal movements of the heart

reactions to contrast media and their

can be shown on real time scan and imaging of

management.

organs by radionuclides and perfusion studies.

3. The importance of the judicious usage ofThese will not only enhance their understan

various imaging procedures, when and how ding by visual impact but the students will also

to requisition them, supplying of proper realise the relevance of learning these subjects

clincal history and detailed findings of the for their clinical work.

physical examinations.

In the para-clinical years, especially for

4. He should be able to understand and

subjects

like

pathology,

microbiology

appreciate the report given by the radiolog

radiology

would be

of help.

When

ist and also the inherent limitations of the

pathology of an organ

is being taught

various procedures.

then along with the gross specimens and

There is a dearth of trained radiologists in the histology slides. X-rays of the same part or

the developing countries due to their migration organ, normal as well as the radiographs sho

to affluent countries and the lure of private wing specific changes that the particular

practice. Moreover, most such countries can pathological process causes in the radiographs

not afferd to have diagnostic radiologists in or changes on ultrasound and nuclear imaging

small hospitals and primary health centres. can be shown. This will make the study of

Thus very few radiologists arc available in these pathological processes more interesting as their

countries for the large population attending implication in actual practice can then be

appreciated.

Government and Semi-Government hospitals.

1.

Since the modern system of medicine

depends a great deal on imaging techniques,

Similarly in microbiology, radiological

changes caused by bacterial and viral infections

MAY-AUGUST 1983

EDUCATION OF UNDERGRADUATE MEDICAL STUDENT...53

in various body organs and systems can be

demonstrated.

In forensic medicine, various types of frac

tures, effect of trauma on the heart, lungs, soft

tissues and perforation of the gut etc. can be

shown radiologically, to make the subject come

alive for the students.

In order to achieve this goal, very close

cooperation is required between the faculty of

radiology and pre and para clinical faculties.

The problems which can arise are the length of

time allotted to radiology out of the tight

schedules of the various specialities and the

reluctance of the radiology department to spare

so much time of the faculty.

imaging in isolation without correlating with

actual patients or without emphasis on the

clinical relevance.

Z^ThT students

are also posted

in small

batches to the radiology department during

their clinical posting. This period is found to

be useful for students learning because :i)

They watch and participate in the routine

procedures being carried out in the depar

tment;

ii)

they observe the

procedures;

techniques of special

iii)

they study the x ray films from teaching

files of the department;

In may not be possible to spare a faculty

member from radiology department, each and iv)

see the practical applications of radiation

every time a lecture or practical demonstration

protection measures;

is arranged. However, simple radiographs can

be shown b the teachers of these disciplines v)

understand the value and limitalions of

themselves supplemented by teachers from

radiological procedures and other imaging

radiology department to give a few demons

techniques;

trations of imaging at the end of teaching of

eaeh system before the next part of the vi)

attend the clinco-radiological conferences

curriculum is started.

held by the department;

In the clinical years is India, about 20

lecture demonstrations are given to the final

year students. These do serve some purpose but

the number of students in a class are so large

that not every student can see the lesion or

retain his interest. In our experience, showing

radiographs to undergraduate students is more

effective than projection of slides.

Small batches of students or integration of

imaging in various seminars and in integrated

teaching will be more benificial than teaching

vii)

learn interpretation of routine rediographs

and gross abnormalities of various structures

and organs;

viii)

learn the cost effectiveness of various

procedures as related to the yield of infor

mation. z -

Here, a great deal depends on the faculty of

the radiology department, how much time they

can spare out of their routine work, teaching of

post-graduate students and research, for under-

54 -THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

graduate teaching. Individual attention is

required, if they want the student to develop

interest in the fascinating world of radiology.

Ability to recognise and interpret radiologi

cal signs and analyse and correlate them with

the clinical findings can only be achieved if

more time is spent near the viewing boxes by

the students supervised by the faculty and

'^^ME XXII ■ No 2

students are encouraged to follow-up their

cases to get the final diagnosis

In our experience, the response of the

students is directly proportional to the enth

usiasm of the faculty. Many undergraduate

students decide to take up radiology as a

speciality after their posting in the radiology

department.

Performance Factors of Attempt and Non-Attempt'

Holding Medical Students — An Indepth

Interrogatory Study (Part-I)

By

H. Saran

A. K Malhotra

W. C. H. Cum Lecturers

R. N. Srivastava

Prof. & Head,

Department of Social and Preventive Medicine,

M.L B. Medical College, Jhansi

Introduction :

The medical science is expanding very fast

and the day is not far off when it will^pbse a

challange to the top level amongst/planners

engaged in the delivery of medical' education.

Recently, it has been observed that the

knowledee in medical science doubles every

7-10 years. It is a bitter truth that the

majority of medical teachers are still untrained,

unab'e to impart ^their full talent, skills and

knowledge to their future on-going generation.

The medical/institutions, in general, are

following the tradational way of teaching/

training m spite of tremendous adancements

made /in the educational methods and

techniques in the past few years (Srivastava

at all, 1982) neglecting the interest of the

medical students (Saran at al?, 1982).

The facts that the medical students are

selected through a tough competitive exami

nation usually with their past brilliant

scholastic performances can not be denied.

Majority of these students experience one or

more failures during the medial career,

However, only a few get through unspotted'

though all reside in the same socio-educational atmosphers, why is it so ? Have the

eminent medical educationists ever thought

about it ? The answer at the most of the

time would be, no. It not only creates a

burden on parents/Governments but also

mental set back amongst the medical students.

A drastic change in the selection method

of medical teachers, initiation of teachers

training programme for medical teachers with

some attractive incentives, adoption of recent

advancements made in the educational

methods/techniques by the medical institu

tions, teaching by and restricting strictly to

the well pre-planned lesson objectives/plans

and provision of due place to the interest/

mental status of the students during teaching/

training may provide some solution. Recently,

Saran at al-*,4,5,6, reported the various per

formance factors of medical students responsi

ble for obtaining different scores m the

Septembtr-December

Dental Departments of Medical CoSgcs

for Teaching M.B.B.S.

By

J. R. Sofat

Professor & Head of Dental Deptl , Dayanand Medical College, Ludhiana

The prevalence of dental disease is very

high in India. Periodontal or gum disease

alone afflicts 90% population. With change in

life style resulting in modern living the occurence of dental caries has risen from 50-70%

in fifties to 60-90% in seventies. The incidence

of oral cancer related to typical Indian habits

with high figures of 40-50% of all diagnosed

cancer as compared to western figures of 1-3%

also poses a serious challenge. It can be

summed dental disease affects approximately

the entire population.

One dentist for 4000 population is the

need as pointed out by Bhore Commission in

I9J5 and one dentist for 80,(00 population

with a mere 9000 dentists in the country is

what we have attained. Since the majority of

dentists are concentrated only in cities, this

ratio will be still worse if one seas only rural

India This number is no doubt far below

need and it is no wonder the ailing public

seeks relief from unqualified practitioners. It

is not practical to reach the target of dentist

population ratio at the existing number of

dental colleges in foreseable future. It is

regretted that Government has not evolved

any specific programme for the promotion of

dental care. There is no mention of such a

programme in the 6th Plan which has the

outlay of Rs, 18,000 crores for the health

care.

The only solution for India is to launch a

massive compaign at community level in pre

ventive dentistry. Despite relatively huge

man power of 1,33,000 dentists in USA there

is a growing realisation that preventive

measures are the only solution to tackle the

problem of dental disease in that country The

limited dental manpower in India will not be

sufficient to treat even a small percentage of

the quantum of existing dental disease. Due

to this magnitude of dental disease, paucity of

dental manpower and urgent need for preven

tion, it is suggested that medical men be given

some dental responsibilities through better

dental teaching at the level of undergraduate

medical education. May be we can incor

porate preventive dentistry with preventive

medicine whose infrastructure is much better.

Dental departments of Medical Colleges are

in a state of evolution. With better under

standing between the Dental Council of India

and the Medical Council of India these dental

department are much better now than ever

before. Since the position of Head of the

Dental Department in medical colleges has

been upgraded to the level of Professor (in

1976) the prestige of the dental profession

has been enhanced. Consequently a sizeable

number of dental experts usefully employed.

These dental experts are performing a notable

role in dental education and research. The

1983

Dental Departments of Med cal- Collegs ...13

dental departmen^k of medical colleges are

being rationalizetSFMuch has already been

Recommendation of M. C. I. to be specific :

done to align them in their due perspective but

a lot yet remains to be fulfilled. The standard

regarding the number of staff members, their

qualifications, basic equipments, beds allotted

to these departments and teaching schedules

from place to place. There are still places

where no teaching designations are given to

staff and dentistry is not taught to MBBS

students. The Medical Council of India has

prescribed some guidelines but these are either

vague or incomplete or not followed uniformly

Since the inspecting teams have no dental

experts the set up of dental departments

is ignored altogether

All recommendations of the Medical

Council of India (M. C. I ) in respect of

dental departments, should be specified for

100 MBBS admissions and should be varied

in proportion to the numbet of admissions.

The minimum recommendations should be

mandatory and nothing should be left to the

discretion.

Teaching : The booklets published by

M. C. 1. contain no mention of the dental

curriculum to be covered during teaching of

M. B. B S. students. The curriculum must

be laid down specifying curriculum. The

following curriculum is suggested :

The following observations need thoughtful

probing and remedial measures at the hands of

the authorities concerned :

(1)

Introduction to dentistry and its

various branches. Aims of teaching

dentistry to M.B.B.S students.

Basic Objective :

(2)

Norms : Anatomy and Histology of

teeth and gums.

Deciduous and

parmanent teeth with their numbers

and dates of eruption and their func

tions.

The dental department is primarily con

cerned with the teaching of dentistry to

MBBS students, the treatment of maxillofacial

and dental outdoor and indoor patients and

conducting research. Teaching dentistry to

medical students is to help the medical teachers

turn out a basic doctor equipped well with

knowledge to treat a patient as a whole in

cluding dental ailments.

This is specially

applicable in remote areas where no dental

expert is available. Besides, the medical

graduates are expected to give first aid dental

treatment in cases of emergencies including

maxillofacial injuries and to decide about the

cases which need referral to the specialist.

Above all, they help the dental profession to

spread out dental health education which is so

important in the’prevention of dental disease.

(3)

Dental Health education :

(a)

Local and systemic ill effects of

diseased teeth.

(b)

Fundamentals of oral hygiene.

(c)

Rules for better dental health.

1 (4) Common

06

dental diseases such as

dental caries, periodontal disease,

malocclusion, oral infections, halitosis,

abnormal growths and non-healing

ulcers due to malposed and sharp

teeth ind ill fitting dental appliances

14 The Indian Journal of Medical Education

Volume XXII No. 3

■ September-December

Dental Department of Medical Colleges ...15

1983

(a) Oral menifestations of systemic recommendatioi^^ar any theory class. This ; units, with the

completement of each that medical teachers in medical colleges except

the tutors, residents, registrars and demons

disease and role of oral diagnos is not the oppertune time for teaching the ■unit of 30-50 beds as :

tician in the overall diagnosis subject and consequently does not serve much

trators must possess the requisite recognised

I

(a) Prof./Associate Prof./Reader. —1

of systemic disease.

postgraduate qualification in their respective

purpose. ■

■

(b) Asstt. Prof./Lecturer.

—1

subjects. But under the heading “Qualifica

(b) Systemic menifestation of oral

tions for Dentistry” on p. 25 the qualifications

Dentistry is like a super-speciality to the

(c) Chief Resident/Tutor/

disease (focal infection).

recommended for the post of Lecturer is only

undergraduate medical student. The student (■

Registrar.

—1

B.D.S. This is a gross anomaly and is not in

(6)