MEDICINE ETHICS

Item

- Title

- MEDICINE ETHICS

- extracted text

-

If

RF_MP_2_PART_1_SUDHA.pdf

■

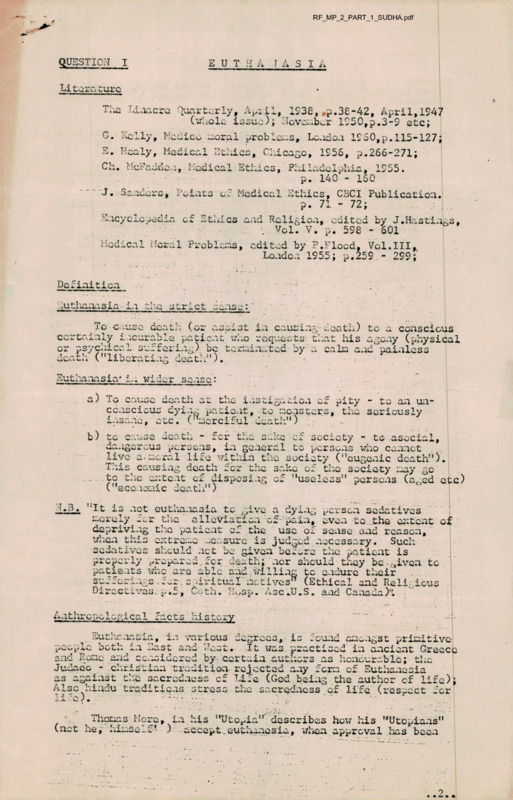

QUESTION

I

E U T H A I A S I A

Literp.turc

The Liaacro

Li.iacra Quarterly

Quarterly, AKril, 1938, .p.38-42, April, 1947

(whole issue); Hcvenbur 1950,p.3-9 etc;

G. Kelly, Medics uoral problems, London 1950,p.115-127;

E. Healy, Medical Ethics, Chicago, 1956, p.266-271;

Ch. McFadden, Medical Ethics, Philadelphia, 1955.

p. 140 - 150

J. Saiidai's, Points of. Medical Ethics, CBCI Publication,

p. 71 - 72;

Eacyclcpedia. e f Ethics and Religion, edited by J.Hestiar,s,

roo _

rm

■. Vol. v. p. 598

- '601

Medical Moral Problems, edited by ?.Flood, Vol.Ill,

London 1955; p.259 - 299;

Definition

■.

^utl^anasia-in the strict sense: '

To cause death (or assist in causing-death) to a conscious

certainly incurable patient' who requests that his agony (physical

or psychical.suffering) ba terhindtad by a calm

cahc and painless

death ("liberating death").

Euthanasia*in wider sansa:

a.) To cause death at the i.'.stigation of pity - to an un

conscious dyinr patient, to nens^ers, the seriously

insane, etc. ("nerciful death") ..

b) tc cause death - for the sake of society - to asocial,

dangerous persons, in general to persons who cannot

live amoral life within the society ("eugenic death").

This causing death for' the sake of the society nay go

tc the extent cf disposing of "useless" persons (at.,ed etc)

("eccieaic death")

"It is .lot, eutha.ia.sia ta ^ive a dyi.v; persen sedatives

reexaly _<r tlie allaviatian 'of paia^ avea to. ths extent, ei

depriving the patient of the use of sense and reason,

when this extreac ...ec.surc is judged necessary. Such

sedatives, should net be given before the patient is

properly prepared..for death; nor should they be ^iven to

patients who are able and.willing tc endure their

sufferings ..far, sniritudl' ncfives" (Ethical and Reli icus

Directives.p..5, Cgth.

Asc..U.S. and Canada)’’. ’

ZxathrcpGla■gical facts history

Euthanasia, in various degrees,, is found oiiangst primitive

people both in East and- West. It was practised in ancient Greece

and Roae and ccnsidered by.certain authors as honourable; the

Judaea - Christian tradition- rejected

- -----any

tomfcr:

of. Euthanasia

as against the sacrednes-s cf 'Life (God

(rr'A being the author of life);

Also hindu traditions stress the s acrodness of life (respect for

Li n).

^21;- ......

V. ... ' . f' /y-y :

■ -

’■

Jhi-... ..

..... . -

.

.

:*

Thoms Mere, in his "Utopia" describes how his "Utopians"

(not he,'hinsa1f’ ) accept.euthrnesin, when approval has been

•

9

• O» •

*

2

Frailcis Bucou, in his

out^sl^Stridufeg'ShS!?1'-113*1^ SUr0?“' tC ■•>12o<i fOT

--iorn society cuthaiiosia. in various

has been

G;:tc;lt cf-etgaaised disposal of’ the

uarit.-aa ...itier s Germany.

.

’^-Q1 t*ie oxtoat tc which this society •’s nnro^Htnri

With natqruiisrs, -thQ idea of collective ef^ici^cv

as lt <?*“ with the Sclents; the value of

t^Fto^t-'^

T^st ail, aad euthaaesia

1^“GC

t"P Juridical system under

~**+. **’^fc'r

7™r^ss«ca> Oa the other head., to the

t'l0C?^YVY‘'iiC-‘--a-SGCiGty PrcSGrves spiritual values,

■a--lcIcacy yields tc the respect due to the

-u......

qua person,' whether he is weak er stroi' -ec?~

eutha-icsia aever receives leca'v!

hlacft&vfoSrtj?1

270)

r3jocts ia U " ■

r..c . C;1 Cr;'cb-;r 17, l£50, the ?Ierld hedicdl Associatioi cctr'esed

o; aateeanl' aedccal assaciaticas of forty ..ae di^^ent

“ rcsclutica ^-ich called eutho-iesia’

l«iccl A^alatto-

VS

gniats tc be considered

1•

S£cigA. ccaseouences or accept,>ace cf euthanasia:

loarJg St^eFf^r^eSlS^LSs'S^it

t^lSd’158!^^??^?8"- dcvhati°^ I4 wral principles i's^li ely

iu4?F:,d ft ^thanesio.caa be justified in one case, it cZn be

“FlslV

act'-ure taoori.es wo invent, but "facts --ac_..t year^ nnowa tc the Whole :world" (Ststenant CBCI,~1953)

CM

~c ^3=rs uaatXcaod

^+.44_ 1

•? ,

n. Bciiaar. ai.v» 1 vp.■?

raa<ni-“o^

F®SXSCr?rc>in. England, shows that t^°

(A.‘Boiler*

c^??e;d!;r 7^0 than voluntary euthanasia

K..x.u.r, sna u^t..^^sc aactor, London 1251, p. 105 - 111).

2*

Sequences for the nodical profession in particular '

The practice af euthanasia would greatly lessen conhi^aice &FWt^^^^iniu^a;r.w!?° 'F Suavely ill sight readily

”-Vt?1- judge hrs case incurable and so

to’-Gi3^'7Z?7CF;a TIFF

By a- uaans uninportaat

the SlthFdFe'tscpn.

insdlised autbaaasia upon

3

The elevated coiiccptien c£ the dignity aad the high

seriousness of the physicians calling wore act easily gaiaed*

It was after ceaturies of ceaviaciag proof that the sole purpose

“paysiciaa was to proloag life aad relive paia that

^eaiciae

able to advaace* It was oaly after Law ao acre

deaaaded xarallxbilty ca the art of the physciciaa, but oaly

ti-at degree or skr^l, kaovledge aad care coruicaly possesed aad

excercised by the average reputable practioaer ia the locality,

0**01 itwas possible for neeiciae to iuprove the accuracy of

aiagaosis aad to better the uetheds of its treatoeat, aad that

ca—e about attar oaly oae develcpreeat - absolute coafideace that

w‘;?*-}ly aiu, or the physiciaa was to proloag life aad to

re^iee sufreriag. Mow there a-.e those who would assiga to the

physician a duty cf shortening it (Healy, r.2G9)

3.

Ccnscqucaca fcr

.C

co- tha patient

a) Suthanasia is bad medical practice. "The doctor oust

sustain hope fcr the incurable persen". There are eiiample.s

that an apparently incurable dying patient get curred; revealing tc a patient the fact that he is incurable nay

cause greater suffering and nay become an obstacle for

possible improvement.

b) Euthanasia is failing in true service. Tc assist a

person.in living up to the challenge of a very difficult

Situation (as an incurable illness is) may well be a

greater help tc the person th-n assisting him in escaping

_rom it. "Maa is net a more animal; pain is not the

greatest evil.

Suffering accepted (from the hand of Gcd)

has an immense value fcr man" (cfr. points, p.72)

F-^adoKa.-itc-l questioa

A dectcr aces ict deal with j-aias or deseases but with

persons._ His vocation, to assist the person who need his help,

rs not United to assisting hin in recovering health or aliviatrng pain but ezteads to assisting the person, in the way he can

on., as well he in the eulfilLaaat of hia fuadaneatal task, which

nay lacnaae the duty to face suffering and approaching death.

(’-ily if the patient has the right to die can a doctor

assist hm oy causing death.

Jherefcra, the fundamental question is: has a aaa the ri^ht

to ana nis life under certain circumstances.

, ‘'?c C-7C, c“-} Give permission far murder; no private individual

or^puolic authority is allowed directly to take away or shorten

It-.o or an inacceat person. To do sc is an iafriagaaent of God's

-ooain over life and is this contrary to the natural noral

law" (Statement CBCI, 1253)

Things are cor r.an to be "used" and ccnseq-ently can be

dis^GGod of c.according to man's needs. Man is net a "thing" tc

be used aad <ccnsaquently cannot ba disposed of according to his

-iQQds ar wishes

per

hc_.< Man is a person.

Els being conscious free

izrplias a.i uricaaditiorjal1 task, the task to realise his true self

ia oxistia^ for the ether (Gad

_d, man), ia the concrete circumstances

ia which he fiads hiraaalf. This unconditional task implies;

aaci-ig the cbnlla-igcs af life tc the bast of one's

c-ie's abilities under

all cirausistaac-as*

HOTSS Off y.^EpiCAL ET^ICS^.

purpose of the proposed discussions is to focuss •

tr"e ££?ci~ic clnracter of an ethical approach

Pr5-Cfical Ttestxcas’ and ca the fundamental i isi^ts

implied in any moral judgement.

m.igr.ts

X=Ss£2Kli£;Ji

fi==£2B=3&iyEi)=£g=;£ys2isAL2=3IHI£§

Definition of Ethics

etymologically, the word ’u^.i

ethics’ refers to a) customs,

customs.

manners (ethos) and b) inclinations;

; tciideacies, attitudes

Thus1t1^ UCI? 'ethics' indicates: a science

o- hal-aving anu or attitudes revealed in these f--- ; of ways

briss of behaviour.

, .

Iu cur context, the term 'ethics' refers to- "t-’-n nb-?ir,cd

bai^ “

L

--a' likK; co"?

so

an piasigfcJt

-^trre os man a.id consequently to judgements> oa good

-ja ev.ll m maa'.s actions and attitudes.

J^c..^xes

■

■’

’

o

B ^'•plu.iatxon: Ethics is a pa.*-*.losophic *e:*.’loctioa oa beiap

i** tails world. This ref lacticon reveals

that this being is:

a*i Orwistia-' - at .-this world -‘ with others

73

eoyocc tho/ldoo •Uhi.rf' or 'i.V our btil - in God", - it un- J

cur being in this world, - 'the

niQi^aing.. o^. »/amaa anistenccr9 , - ■ hiie

aatidre or nan’'l«

■Hoc

Discovering the nature of man is discovering a task

» " h

-■*at gives meaning to our- beih^•g rree.

■This'task r man himself and can be described in

general .terms as 'ccnceras

.to*.-realisation", - "becoming ones1 true self

in existing at this world,, with others, in ’Gdd°".

This task

,-- is an unconditional task (duty), ■“ a task which

Jtan

man 'finds1 (objective idea1),

- a task" to which asaa exists"

(destiny).

It is in the light o.a a growing understanding of the

meaning of Znxian exists rec ;a:‘C Cy^soqucTtly of xa1 s -fundamental

task that we discern ‘ssod’ and evil9 in man’s actions and

attitudes.

gTHICS AHO SCIK E3

.

“ botV e£fct.ts t0

This 1'efi;

~ the true -latarc

W b= «^4:h

9

•

2

Therefore: Whereas ethics reveals- a task, - science deals

with the enperical consequences of man’s actions and attitudes.

Chorees- ethics uncovers the inportence'of man’s actions in

relation to his fundamental task (their ’’moral value”), science, in describing the empcrical consequences of actions and

attitudes, shows their ’usefulness’ with regard to desired goals.

For -b;ampie: varices scionces deal with marriage, - they

state the empericnl implications (physical, psychological,

social etc.) of certain ways of living. They teach hew certain

desired goals can be achieved, and undesired situations can be

avoided. Those sciences reveal the various possibilities

regarding e.g.: marriage. These sciences, however, cannot

reveal the meaning of married life, the ’idea’, or ’ideal’ that

must become reality, in the actions and attitudes described by

the sciences.

Ethics on the other hand, is concerned with exactly the

meaning of marriage, - with the ’values' to be realised in this

human encounter.

Ethics, -however, presupposes science• For, ethics is not.

a reflection on an abstract idea but on a concrete reality, e.g*

mrried life, in the concrete situation in which man finds himself.

Scientific research is needed to get a better knowledge of the

reality on which ethics has to reflect, that is: acts and

attitudes in which moral values are to become real.

Using a traditional terminology we could say: science

studies the ’’laws of nature”, i.e. the properties of things, how they will ’behave’ in given situations, - ”what will happen

if-.

Ethics studies tlx ’natural law”, ii.e.

.2* the ’nature of man’

- hew one should ’behave’ in a given situation in order to

realise the meaning of human existence in that situation.

ETHICS, A :ID .A ■ITl-mePQLOGY

(Scientific) anthropology is a scientific study of man,

describing^his attitudes, customs- his judgements and feelings

regarding forms of behaviour etc. As science it examines the

originand consequences cf these attitudes etc. As science how

ever, it does not judge those attitudes, judgements etc., in view

of a philosophic insight in the true meaning of human existence.

Anthropology is not ethics.

The conclusions cf anthropology, however, will be helpful

for- ethics in so far.they throw light on the human life on which

ethics reflects,

ethics' aid mgpal TEHOLCGY

Moral theology studies man; the meaning of life in the light

of religious traditions, e,g. in the light of the Christian

revelation:. - scripture and tradition.

The-insights cf moral theclogy, however, are'of yititcrest to

Ethics in sc far- as -a deeper knowledge of religious traditions

(Hindu, muslim,- Christian etc) gives‘Wider knowledge of facts

about man,- and nay direct and focuss our attention"i4 the philosop

hic reflection. The conclusions cf ethics, however, are not

dependent on traditional judgement cr specific religious experience.

..3e<

■>

- 3

JTzTCS AID ;; JTCAL ZT’HCS

. nodical ethics is ethics dealing with situations

Shc*rtc'1?» attitudes) typical for the acdical profession.

‘’Medical etnics" includes "nodical professional ethics",

tout is. t-at part or ethics tisat deals with questions concernr?tGuic-3.1 pro-GSsic-n gs such (e*3* rclatio-i to the

patient, colleagues, professional secrecy etc.)

ISDICAL STOICS

"FCSSrHC KADICIJE"

Forensic nediciae deals with legislation in nodical

natters. It studies the implications of existing laws and

evaluates legislation on medical matters in relation to the

common good.

forensic medicine differs in purpose and method irciu

etnxes as it studies legislation not'in relation to a philosophic

Hauerstoidxng of the meaning of life, but in function of the

CGtmoa good, unich is the yorpese of law.

Jhough ethics and forensic medicine differ in purpose and

netaad,

conclusions of forensic medicine are important for

at*mcs as tno lagisLi.ticn to which one is subject is a factor

tnat must oa tumen into account in deciding man’s duty in a ^iven

situation.

°

TRMISPLANTATICi-I - THE MORAL IbbUg

"As a result of medical progress, our technical

decisions may become easier, but moral problems,

on the contrary, will be increasingly significant•" (Dr. J.

Hamburger, 3THICS IN MTDICaL PROGRESS, Ciba Foundation Symposium,

p. 136). Transplantation is one such field. Hundreds of people

have been kopt alive or helped to live because of transplanta

tion of various sorts. Yet grave moral questions are being posed,

and one reason for heart transplants going out of vogue, at least

for the present, is precisely the ethical issue.

INTRODUCTION:

1. MEDICAL APPLIANCES:

These are mainly of two kinds:

i) homoveable a.g. dentures

replacements,

o -S* orthopedic

valvoB, etc.

a) Prosth□scs:

ii) Built-in

b) Artificial organs;

j machine, arti

i) Temporary o.g. hoart-lung

■P

-» A n ”1

IZ 1 H ’

ficial kidneys, etc.

so far nona are available

for human beings, though

an animal has boon fitted

with an artificial heart.

t z

ii) Built-in:

problem connected,

connected witn

with tne

tho use 01

of

There is no special moral proolom

■ - ■

J5''

to use any: c

off them io

is a morm'

moral1 'dothose, though the decision

cision that must bo guidod by moral values whice must be up

held in .all medical practico .

These are of throo sorts:

2. TRANSPLANTS:

a) iluto-transplants: io. thoso that take place within tho

•

11

"'

*

'

body of the person himself e.g. skin,

cartilage> bona.

.

t

~

rl 1T A

) Homo—'transplant»s; i«Q« those that take place from thu

body of one person to that of another.

These include: blood transfusion, organ

grafting o.g. of cornea, kidnoy, liver.,i

heart, otc«

c ) He to ro-t ransplant s:; i.o. those that take place from tho

body of an animal to that of a human

person o.g. sox-glands, organs (inci

dentally, the first heart transplant

over performed was that of a chimpanzee ’ s

heart to a 64-year old man, in 1964

in tho U.S.A.)

In the case of auto-transplants, wo could follow tho aciago:

“good modicino is good ethics". In tho case of hotoro-transplants, tho grave question of possible "personality changes

must bo considered o.g. Popo Pius XII stated that the trans

fer of an animal sex gland to a human Poing woulu have to be

rejected as immoral because of tho groat disturbance to froo» dom which would likoly follow. The integrity of personal lif'-and personal identity prevail over prolonging lifo or any other’

possible advantage afforded by such a transplant. Finally,

homo-transplants present more serious problems, and we must

now considor these separately.

Tho ethical situation changes with the

source for obtaining the organ to be trans

planted A

a) Cadaveric transplants: Thosoj involve tissues and organs^ removed

"from cadavers. It must be accepted that a

person has tho right to bequeath organs of his body for use

after his death o.g. corneas. This would be an example of love

J. HOMO-TRANSPLANTS:

2

for one's neighbour. In the case of a person who has not so

srMatiX“84°Sso?X ”S °x?oof:h?f p?0aeu=o

of presuming such consent, or acting without it le.g. as

happens in some teaching hospitals and. research centres), js

a violation both of the law and. of the rights of the relatives.

Since cadaveric transplants present fewer ethical problems,

doctors should work towards making their use increasingly

• feasible, medically. There are indications of better prospects

in this respect, especially with regards to the use o^ cada

veric lungs and livers.

11.is refers to tissues and organs removed

This

in"the course of ordinary surgical opera

tions e.g. when kidneys are removed in the case of urethral

cancer or the creation of a subarachnoid ureteral shunt. With

our present scientific know-how^ those present an advantage

over cadaveric transplants because cf the contractile nature

of the organ, while,at the same time, they do not involve the

ethical complications which are present in "living conor transplants” (see below).

b) "'Free transplants" :

This refers to tissues and organs

provided by living volunteer donors.

Cardinal ethical issues are involved hore since it touches upon,

two individuals, the donor and the recipient. One has to consider

the risks both to the donor as well as to the recipient.

c) Living donor transplants:

TWO SPECIFIC zdSAS THAT AkOUSE 3THICAL

REFLECTION.

a) Blood transfusion: This procedure has literally saved thousands

---------- of lives, has prolonged others and maoe pos

sible major surgical operations. It provides one of the best

ways in which a man can bo a good neighbour. Barring serious

accidents of typing, sterilizing and labelling, reactions are

rarely serious and they occur in not more than in about 5/o oi

transfusions. Th e overall mortality rate is probably not

higher than 3 in a 1000. However, it.is hard to bo sure of

avoiding the transmission of hepatitis, syphilis ana malaria

(in some parts of the world). Moreover, as wo learn more about

individuality in bloou groups, the developmentof a dangerous

sensitization is a risk always to be kept in mina. finally,

there is the danger of taming the procedure far too lightly:

"topping it off" or "giving a pint more just to ba on the safe

side", has sometimes, ironically, resulted in death.

4. HOMO-TRxiNSPLANTS

How does one act when the patient refuses

to accept transfusion for religious

or rather‘ reasons which

.

-'•

n

/(e.g.

_

—

, Vi ' n Witnssses,

- vt n a

S

not^modical

Jshovah's

are nou_ iiiuu-xuctA

^<.(5.

~11 4 — -P

---- -- f'lor

- - racial o bigots

. ~ \ o<

.

.

' -1

-•

__

~ TO 11

r> <-1 /-»<1 c? r\-yy

Q T. Q Q 1

who refuse to have blood from inferior

races or castes)

.

Should the doctor resopct the prejudices of parents, when

saving the life of the child is involved; or3 of an adult who

refuses to be transfused?

1) Many feel that the parents’ or patient’s wishes should be

t

11)

t

respected, because they are considering not merely their

physical welfare but their spiritual welfare and future

life - and, therefore, this takes one out of the realm

of medicinee No doubt one regrets being thus constrained.

Others feel that the refusal of the parents make it a

police matter, just as a proposed human sacrifice would.bo,

and they would consequently seek a court injunction to

carry on a transfusion» Strangely, the Courts oi Law

not speak with one voice on this matter. Among the various

reasons for authorizing a transfusion of a child Respite

the objections of the parents, is that the chil<x is not

yet free enough to choose its religious convictions, ana,

therefore, must be given a chance to live in oroer to

choose its convictions. In the case of a mother who neeaea

I

•*

-

3

-

a transfusion and. refused, it, the court ordered, it to be

done, because the mother had no right to sacrifice herself

and leave her seven-month child without her services. In

the case of adults, one reason for upholding transfusion

is that since an adult has come for medical treatment, and

Insists on it, he must accept the treatment advised and

recommended. In any event, in the case of anyone who refuses

a blood transfusion, the doctor who feels that he should not

respect the wish of his patient (croftho parent of his child

-patient) should seek a court order to do so.

/

) Organs from living donors: Two questions have to be posed and

answered;

1. Is the procedure justifiable medically?

2. Has the donor the right to mutilato himself?

In reply to the first qusstion,the major consideration revolves

around, the immunologic compatibility of the recipient with the

available donor-organ, dads are presently about 100 to 1 thau a

recipient will get a tissue type that exactly matches his own.

ttonce.tho doctor, who would like to do all ho can for his pationt

because ho has a deep and irrepressible concern for his patient s

needs, should bo careful to also consider more the immunologic compatibility of tho available organ than the need cf the patient

in itself. This would sometimes mean that a surgeon would oe c.n

strained not to transplant, since tho well-being of a parson is

to bo understood to bo more than a mere prolongation of life.

It is interesting to note that for kidney transplants, except i

in ths case of identical twins, probably no more than 15 patients

in the world have survived more than 3 years. The proceciure is

of unknown value in terms of the five-year or ten-year prognosis

(cfr. STHICS IN MEDICAL PROGRESS, p. 67)

.In reply to the second question,two points must be considered:

a) The risk to the patient. It has been calculated that the risk

of nephrectomy to the donor is as follows: 0.05% as a Post-*

operative accidental risk, and 0.07% as the risk of any kind

occuring later to affect the remaining kianey. However,, this

statistic must not be lightly interpreted,and physicians must

have a conscientious concern for the better procurement 0-J

organs which will obviate the necessity of risking a

b) The consent of the patient. Especially in this area when the

donation by a close relative, or twin, affects the saving

of a life, it is difficult to assess the genuineness of

consent. The donor can ba pressurised both by other members

of his family, who might oven consider him expendable(.) arid

by an innor oressurc exerted by his own social and religious

education concerning the value of self-sacrifice,^etc. Tie

doctor should be specially sensitive to freedom oi consent, •

Sometimes the help of a psychiatrist 1st oml^sted.

While it remains true that doctors should work towards pro

curing organs from cadavers, the question remains; within our

present limited options, can a healthy person donate one of his

heaUhy organs to’savo tbo life of anothor? Tho answr houIo

aoam to bo In tho affIrmatlvo. 'or, if »on°°uS.a???!Jtfor his

man can, in self-sacrificing love, lay o.own his life for his

friend" when this is an act of service to the other,

°o^d

also accept that he bee premitted to give a healthy orgqn to

save the life of his friend. However, in arriving at this

decision the following must bo considered:

1) Is thoro a proportionately gooo. reason.''

ii) Is there a reasonable’hopo of success.

1A

Will tho 1 damage1 caused to tho. donor be such as t

ill). Wil

from loading a normal human existence r

3iv)/ Has his consent been duly obtained?

4

5. TRANSPLANTS IN THE "TWILIGHT 101:71’ - 11V ‘ Nd PERSONS OR bEAL1

Wo said,above, that the procurement of organs grom cadavers

would obviate many an ethical difficulty. The question about thmoment of death has become a thorny^one in view of now procoduies

that can keep up certain physiological functions (heart beat,

respiration) even though irreversible brain datEago nas occuxed.

Physicians, lawyers, philosophers and thooioglans must apply

thoir minds to a re-defining of "the mament oi death .(Se- nOoOS

on EUTHANASIA for details about the criteria for determining thmoment of death).This will affect the determination of the con

dition of tho donor - is he -live or dead? But the central problem

of organ transplantation will romain, and wil- have to be sottl-d

by different and independent norms (see below).

Once again in this question, as in so many

otheis which wo have considered in cur course

we

realize that there are disturbing cases in

of Medical Ethics,

Lo find ready-made solutions by ostabwhich the doctor cannot hope to

should

guide himself by tho basic prin

lished standards. Tho dotor s'

ciple of concern‘for the person of the other. On the one hand,.teen,

he should beware lest " zeal for research.is carried to the P01^.

which violates tho basic rights and immunities of a human person ,

on the other, he must work out together with experts ±rom other .

specialities concerned with man (e.g. lawyers, philosophers, social

scientists, theologians),some moral guidelines.to assist him as

he treads tho paths of progress in medicine which ho hopes will be

to the bonefit of man. below is given, by way of oxamp-e, a seu o

PLuidelinos drawn up by two doctors with regard to transp-an ,.aui —

of organs (c?“ HaSmon L. Smith, ETHICS AND THE NEW MELICINE,p 121)

6> FINAL CONCLUSION:

1® Compassionate concern for tho patient as a total person is

the orimary goal of the physician and uho investigator®

2. Organ transplantation should have some reasonable possible

lity of clinical success.

.

J. Tho transplant must be uiidortaxen only with an accoptaD_o

therapeutic goal as its purpose®

4. Risk to the healthy donor of an organ, must be kept lew.,

but such risk should not be a contra-inciication to uno

voluntary offei1 of an organ by an inxcrmco. d^n^- .

5® There must be complete honesty with the patient and his

family, including every benefit of available general

medical knowledge anc. of specific information concerning

transplantation.

,

.

6. Each transplantation shoulu be conducted, under a protocol

which ensures the maximum possible addition to scientific

knowledge.

..

.

7. Careful, intensive, and objective evaluation of results

of independent- observers is mandatory.

8. A careful, accurate, conservative approach to the

dissemination of information to public nows media

is desirable

( urs. J.R• ElRinton and Sugeno D.Robiii)

Medical progress is going to throw up ma.n^ questions to

which’no preliminai’y system of medical ethics can proviuo

immediate and certain answers. 1’he ethical training of a docuor

then, cannot he limited henceforth to the teaching of a few

ready-made rules® To quote Dr. J « Hamburger once again:

”To produce doctors who> are strong men, who ara not only

honest and just in thought, but efficient in action,

-- -- j of the value of human

to develop-, in them an awareness

them

life; to convince id

-- that

’-I--’- their vocation is an ex■ '

1 and to -;t.he group

tensive obligation to the individual,

of facing the

such, it would seem ai'c the best means

;

over increasing difficuloios of medical ethics

(cfreETHICS IN MEDICAL PROGRESS,pn 37 )

•

•

__ —. —, H

4* Vs -n z-s fi I I

gnHctm

(Catholic

OSGAN OF THE CATHOLIC MEDICAL GUILD OF ST. LUKE, BOMBAY

Editorial Board

Dr. A. C. Duarte-Monteiro

Mgr. Anthony Cordeiro

!\lo. 86

Dr. Juliet D’Sa Souza

Dr. C. J. Vas

SUPPLEMENT TO THE EXAMINER

May 13, 1972

IN SEARCH OF A CHRISTIAN MEDICAL ETHOS

By Fr. Denis G. Pereira

Chaplain, St. John's Medical College, Bangalore

We must now explain the word ethos. An ethos is

time when codes seem outmoded and almost

“

~

’ .or from medical ethics.

’ \ and1 ethics seems to be little more different

from

a medical code,

/“^inoperable,

than a convenient way of

ol doing business, jwhi

jWhen Whereas a medical code provides the framework for the

secularism is making inroads into faith, and religious acceptable form of behaviour that would safeguard the

indifferentism is gnawing away at the

T entrails of reli- doctor, the profession and the rights of the patient ;

gious fervour

and medical‘ethics would represent the systematisation

ask • “Is there a Christian Medical Ethos ?” But, of moral judgements involved in making medical

■ in an age of searching — inexorable, rigorous, incisive decisions ; an ethos is the value-system that influences

and honest — this question must be asked by every the formulation of both code and ethics. The ethos is

sincere Christian doctor, if he is to find meaning in his the way a man experiences, sees, and relates himself

being both a doctor who is a Christian and a Christian to, the world and to his fellowmen—is his fellow-man

who is a doctor

a thing» an object, to be manipulated and used lor

About 20 years ago. at an international meeting of self-aggrandisement ; or, a rival over whom he must

Christian doctors at Tubingen, Germany, the question gain ascendancy, exercise control or wield power ; or,

was posed : “Is there a place for continuing to run a neighbour, his neighbour, one who makes an impeChristian hospitals?” Whereas some, among them rious demand on his love and respect one for whom

clergymen, challenged the propriety of having ‘Chris- he must care in his need, and for whose benefit he must

tian’ hospitals, the assembly came to quite the opposite strive to ameliorate the social and ecological conditions

conclusion at the end of the meeting. The assembly of living ?

.

. .

of Christian doctors felt that there are problems,

L seems obvious that in arriving at an ethos parti

mysteries, perplexities connected with healing, living cular to his profession, the doctor should consider not

1

------ -z—, only the existing code, but also the convictions and

and dying, to which secular medicine has

no answers,

and upon which the Christian Gospel ol the death and

and ethical behaviour of conscientious colleagues. But,

we may well ask, is this ‘medical ethos’ to be restricted

resurrection of Christ does throw light.

Is not this the perennial question we keep posing to to a lowest common denominator of accepted values?

ourselves : What difference docs it make that one is Can a doctor be satisfied with an ethos based on a

a Christian? Does his Christian faith make him a moral values (if

; one could truly

. speak of such), on

better, or different sort of, doctor than his non-Christian values determined by the utihty- , or, efficiency-, or,

regulate

a materialistic

colleagues, leaving aside their respective technical proJit-, principles that: so r”1form

competency or diagnostic skills? A Christian doctor society? Can an ‘everybody-does-it” principle

;

mst answer this question if he is to find the meaning the basis ol a justifiable medical ethos .1 Is there not

and relevance of his faith in his professional life, and room for a Christian medical ethos ?

accept courageously and cheerfully the challenges that

r-umcTTAv

an increasingly secular climate of opinion and attitude DIMENSIONS OF A CHRISTIAN MEDICAL

will inevitably pose to his Christian conscience.

.

ETHOS

When speaking of ‘difference,’ we must beware not

A Christian medical ethos must spring from the

to think in terms of ‘better’ or ‘worse’. The question, Christian faith. It must spring from the understanding

as C. S. Lewis rightly suggests in his book MERE the Christian doctor has of his vocation in the light of

CHRISTIANITY, is not whether being a Christian his faith. A Christian physician who models himself

makes you a better man than someone else who is not, on Christ—whom Christian tradition has given the

but, rather, whether being a Christian has made you singular title :

The Great

Physician —would

a better person than if you were not a Christian. To obviously have a set of values which he would not have,

use a commonplace medical analogy : to ask whether were he bereft of this faith.

Miss Buxom is healthier or not than Mr. Pehlvan

1. The Concept of healing :

To a great degree, the

because she takes Multivits and he does not, is a mean- formation of a Christian ethos would depend on whether

ingless question. The real question is whether there is a Christian concept of healing. It is to be

Miss Buxom is healthier because of the Multivits than noted that a very specific sign of the Kingdom of God,

she would be without them. Hence, we should be mentioned in the Gospels, is the healing of the sick,

asking ourselves whether the right understanding and Even the forgiveness of sins is linked with the healing

living of Christianity makes better persons of us or not. process. “Go, sin no more. Your faith has made you

In the same way, would it make a difference to the whole” (where ‘wholeness’ refers to total well-being,

doctor’s understanding of his role and mission in life which is an adequate definition of health). Is it too

that he has accepted the challenge of the Gospel, much of a surprise, then, to note that the ultimate

through a personal commitment to serve his ailing injustice is described, among others, in terms of refusal

neighbour after the example of Jesus Christ? Obvi- of health-care : “I was ill and you did not come to

ously, we are speaking not of the nominally Chris- my help” (Mt. 25, 43) ? A Christian doctor through

tian doctor but of one whose vision of Jesus, the his work of healing shares in the mission of Christ ;

Great Physician, brings him to see his calling to be a he proclaims the Good News through his ministry of

doctor as a mission ; of one who takes seriously such- healing, thus extending the frontiers of the Kingdom of

like sayings of Jesus to his disciples (among whom he God, or, if one dislikes the triumphalistic overtones,

counts himself) : “You are the salt of the earth. . . makes the kingdom more present among men. In

you are the light of the world.” Such a doctor would this ministry, he is God’s instrument, doing God’s

legitimately be expected to ask : Ts there a Christian work of redemption. Both his personal life, then, and

his dedication

dedication to

to his

his healing

healing function,

function, must

must proclaim

proclaim

medical ethos ?’

his

ATa

70

SUPPLEMENT TO THE

EXAMINER

May 13, 1972

the presence of God.

Besides, he will accept the the right spots, and on responsible persons in public

obligation, before God, for the health of the individual office, to ensure that health-justice is provided for those

for his total health as a person, and, through him, for all who, in his Christian conscience he feels, must be

those who need his care. He is, in a word responsible cared for, and when such care can only be provided

to God, and responsible for his fellow-man’s health, by public agencies. To give an example : concern

and is bound to provide the best ministration he can in for the rights of the unborn, in the face of liberal aborthe situation.

tion legislation, must make Christian doctors want to

This last phrase may sound like a pious cliche, but, do something about getting a different sort of social

as a Christian, a physician must ask : “Before God, legislation (that would, for instance remove social

what is the best ministration in this situation ?” In stigmas like illegitimacy) passed, and about working

other words, can one rest content with the status quo for the setting up of counselling services for distraught

of current medical practice and accept the ‘non-choice’ women seeking abortion and Homes where, they may

approach that characterizes so much of today’s medical be helped to have their babies with dignity and without

services? Is the Christian doctor — and, by extension, “fears.”

the Christian medical institution and the Ghurch(es)—

The Christian vision of man, as it is worked out in

to view his medical mission as meaning ‘to provide the the community of believers, must further influence the

best care to those who come to him,’ or, must he go development of a Christian doctor’s ethos. This

further and assume responsibility for those, too, who understanding of man will bring special light to bear on

do not come because they are either ignorant, or can’t some problem-situations, such as those which come up

afford the fees, but are in fact most in need of his care ? in genetics and human reproduction, medical experiOur Christian concern must determine the way we mentation and the dying-event. Further, it will affect

fix our priorities. A pediatric Mission-hospital in one’s dealings with one’s patient, and the respect due

Africa had an excellent record of service and of care to him coupled with the obligation of not taking adprovided to every child that was brought to it. At the vantage of his helplessness to feed one’s greed. It will

same time, during the 50 years of its existence, the determine the nature of the medical secret, the obligainfant mortality rate in the area served by the hospital tion to respect the conscience of the patient, and his

remained at around 282 per thousand births. While right to know the truth about his illness.

providing excellent care to the children, brought to the

2. Other dimensions : One could bring within the

hospital, its authorities had failed to provide basic, scope of his Christian ethos the doctor’s obligations

life-saving care to the numerous children that were to, and relationships with, his colleagues, especially

dying of ‘neglect’ in the surrounding area. It’s excel- the junior doctors who have to set themselves up. Too

lent doctors were too busy saving a few at the expense many doctors enter into a rat-race for patients, and

of the many. In terms of costs, one could say that the bigger practice, at all costs! Not merely professional

cost of saving one child on whom, say, the equivalent decency, but effective charity — really caring enough

of Rs. 500 was spent, whereas, if the same amount was for one’s colleagues, and their welfare, as to want to do

diverted towards providing even basic medical care, something about it —■ should determine right relaten children instead of one could have been saved, tionships. Is “group practice” a Christian answer ?

was, in fact, Rs. 500 plus 9 deaths. We need specialised Or, entrusting part of one’s burgeoning practice to a

hospitals and specialist doctors and excellent care ; junior colleague ? Each Christian doctor must find

but we also need to think in terms of the greatest good his Christian answer to the demands of love in his own

for the greatest number. It is a case, therefore, not of life situation.

“either-or” but of “both-and.” Incidentally, in the

Still another dimension is the Christian doctor’s

above mentioned case, the infant mortality rate was relationship with his own family. His absorption in

brought down to 78 per 1,000, within five years, through his work, whatever the motive he professes, may make

the action of a concerned pediatrician, newly arrived, him not care enough for those for whom he is obliged

who requisitioned the services of 15-year old girls, to care.

Further, living as he does in an underfrom the local mission school, to provide the basis of developed country, the Indian Christian doctor cannot

health education and health care. (This is a line of absolve himself of the obligation of thinking in terms of

thought and action

that GPs.,

with a large

and com- the needs of the country and the community, in fixing

.

.

J

fortable practice, could fruitfully consider). We need whether he is going to specialise or be a G.P., whether

constantly to re-evaluate our <concept of “service” in he will practise in the town or in the mofussil, whether

the light of the Christian imperative of “caring. he will serve in the country or go abroad (to get jobPerhaps we ’would find plenty of which to be ashamed satisfaction, or to ensure the security of himself and his

in our “service.

”’

family).

This is an ethical decision from which the

•

The Christian’s one guiding law is that of love, which doctor cannot escape, for, in fixing his “priority,” he

someone has paraphrased as meaning : “to care is determining the measure and quality of his service

enough about others as to want to do something about and charity.

To be, in India, an U.S.-qualified

it.” How does one “care enough” in a Christian way neurosurgeon, may mean that one restricts one’s service

especially when we know that needs will always exceed to a microscopic minority, composed in the main part

resources ? There are no ready answers, but we must of those who live in the larger metropolitan centres,

keep asking ourselves the question, often an agonising and who can afford the fees. Of course, the country

one. One suggested criterion for helping us fix our needs specialists — but the decision to be a specialist,

priorities is that of the “Poor.” The “poor” are not or not, must be taken in accordance with his Christian

necessarily the poor in any simple economic sense, but vision of the demands of love in his life-situation,

rather the neglected, the ignored, the rejected, the dropFinally, his Christian ethos must make him care

outs of society, those who are not cared for and to whose enough for himself, giving himself the time to relax

rcare no prestige is attached. Where there is a pioneer- and to pray, to build up the resources of his faith, so

ring need to do this, because nobody else will give that the frustrations of growing in age may not make

ennui' *to

others.

.attention to it, then it is a Christian calling. As Chris- him a_ cause

---------of

r--------1----tians our particular, though not exclusive, concern is

Conclusion : The Christian doctor, indeed, must

to care for those who are not cared for ! Each Chris- keep searching for a '’specifically Christian medical

■tian doctor must listen for this specific call of God, in ethos.

His, faith, which he must ever strive to keep

the secrecy of his heart, to such service within the alive, must make him view his task not merely

’ / as a

.'framework of existing situations.

iprofession 1but' as a calling, a mission, i.e., a °‘being sent

Another aspect to this ‘service’ must be considered, forth’ to carry out, in its total sense, the healing work

It is not always, nor only, a question of what a Christian of Jesus. While loyally giving ear to the teachings of

t doctor should do in terms of individual service. Prac- the Church’s Magisterium, he must remember that he

ideally speaking, much, in a developing country, has too is a partner in listening, and active sharing, in the

to be undertaken by Governmental agencies. The process involved in making moral decisions relative to

Christian responsibility of the doctor, then, would also complex medico-ethical problems.. He must be prezconsist in exerting himself to bring pressure to bear on pared to, and, in fact, conscientiously ask, the daring,

May 13, 1972

SUPPLEMENT TO

THE

EXAMINER

71

if upsettino-, question : '‘What more does God expect That is the risk involved in the search ! But the search,

from me?” ’ “Am I really caring enough so as to fix the in Christian tension, must go on and the Christian

right priorities according to the mind of Christ whose doctor must be prepared to act according to his Christian

minister of healing I am, and to the promotion of whose insights. A medical ethos based on such Christian

kingdom I must dedicate myself?” Many questions Searching will certainly make a difference—hopefully,

are unanswerable, or are not immediately answerable, for the better !

THE FAMILY DOCTOR

(An Eulogy)

By Dr. Fred Noronha

jT is perhaps no exaggeration to say that no greater the family he treats, he often can and does detect the

] honour, responsibility or obligation can fajl to the presence of an unwholesome environment or unhealthy

lot of a medical practitioner than to become a Family trait or attitude on the part of one or other member of

the family. It is not uncommon for an alert Family

Doctor. For such an assignment, he needs not only

Doctor to avert or nip in the bud, by his timely interthe scientific skills of his profession, but also human

understanding, courage, wisdom born of experience and vention,, an abnormal situation. Many a conscien

tious Family Doctor has saved an emotionally insecure

emotional maturity if he is to provide this unique service

child from future tragedy, effectively diverted a floundetn his fellow-men. The Family Doctor is not a mere .

~ .

r • r

healer of disease, he is also a friend, confidante and rmg adolescent from the path of delinquency,, successneaiei ui uiacaou,

Mo

(Art q fully advised againstt a b—

hazardous

marriage, averted

counsellor to the family he treats. He is, in iact,

’ ’•

suicide in a depressive, restored an alcoholic to sobriety,

privileged person.

In his traditional role, he not only •

1 an elderly patient to lead a happier life despite

endeavours to prevent and cure disease, whether ol

his

disabilities

and performed a hundred and one in

body or of mind, but also enters into a more personal

relationship with every member of the family. To tangible services which his unique relationship with

only

him, each of them is a person and, he attempts not c’y th6 Family made possible.

The Family Doctor is often faced with the sadder

to consider the physical and psychological problems of

f medical oractice. Few problems

aspects of medical practice. Few problems are more

pmpSfA'cSte

di.lra.ing tb.n .ho.e printed b, the p.iimi wiih

incurable or fatal disease. With tact, and deep under

„"E11ieu..,dgrp£ —

standing of human nature, the Family Doctor knows

have a beaung on ic o-ives them inteffi- when, what and how much to say about the illness,

him, on the health of his fam ly Hegives^intem

Doctor has

gent and humane care wi

, y p

<

..

.

often succeeded in bringing warmth and cheer to the

standing. For lum,

PaUent is mot;a mere collectmn

situations He d

to

of interesting signs an

V I

,

L emotions draw heavily on his humanity, mature judgment and

ordered function, ise

g

RnHv mind and intuitive talent on such occasions and be careful to avoid

but a complete person, mac

B

• a ^misanthrope unnecessary psychic trauma both in the patient as well

soul

He really cares

hj P^r eve“u^ as in his relations by avoiding words and actions which

could never be a good Family Doctor even though he

ntiall introgenic> An indiscreet remark, a

might be a bn lan lagnos ician.

solemn bedside conference or an ominous frown For

A dedicated Family Doctor brings to the ailing patient Examples could each of them cause untold harm to

and his anxious family a feeling of confidence and

anxjous patient of his relatives. Yet he, owes a duty

security. Illness often creates problems for the patient tQ

patjent to encourage him to prepare himself for

and members of his family such as, interruption ol daily deadl both in the material as well as in the spiritual

domestic or occupational activities, financial embarrass- piane When death occurs, there are the survivors stricment, fear, anxiety or depression. Moreover, illness ^.en w|th grj,ef who also need his attention. Often, he

sometimes profoundly alters personality or constitutes necd not do or say much in such a situation, His mere

i threat not only to the patient s bodily integrity, but presence and a few consoling words may help lighten

also to his status in society. A person in such situations their sorrow and feelings of helplessness.

often seeks the help of another on whorn he can rely

rj.Ee essendai difference between the family Doctor

as a trustworthy friend. The Family Doctor fulfils and his other colleagues lies in the former’s professional

the need admirably.

attachment to the family he treats . He is above all,

The Family Doctor’s grasp of the patient’s personality, a personal physician to the members of the house-holds,

background, hereditary traits, environment etc.,, places and his service is personalized.

From this relationship

him in the unique position of being able to know his there flows a two-way traffic between the Family, and

■ '

patient in his totality,

a fact which enables him to the doctor. Genuine affection, mutual respect, loyalty,

evaluate symptoms more accurately and intelligently, confidence and trust in the doctor on the one hand, and

early.

An early diag- concern,...

sympathy, professional integrity

and often to diagnose an illness

i

,

. on the other.

nosis generally implies less suffering, speedier• cure and Such is the foundation on which a most fruitful doctor

less expense to the patient.

patient relationship thrives.

Strange are the psychological attitudes which some

Some people, unaccustomed to the ministrations of a

patients adopt when ill. Some appear to take a secret Family Doctor, might conclude that such an entity does

delight in illness and resent anything that threatens not exist save as a figment of one’s imagination. The

their invalidism ; others refuse to face facts or bellittle fact is that changing patterns of society and a variety

their symptoms ; others again, try to adjust their dis- of other circumstances are creating an atmosphere in

torted personalities to the environment by one or other which the Family Doctor can no longer function qua

of those devices known to psychologists as “mental Family Doctor and may soon face extinction. On the

mechanisms,” and so on. These phenomena are not other hand, since no other system of medical care can

susceptible of solution by the use of precise scientific fully and satisfactorily replace this unique institution

methods, but require profound experience of human it seems reasonable to expect a resurgence of the Family

nature and some degree of maturity to probe beyond Doctor in future albeit in a new garb.

The family

surface motivation and behaviour, see accurately and Doctor of the future will, like his predecessor be a nondeeply the problems of another human being and tackle specialist and very human General Practitioner who will

them satisfactorily.

care for his patients and not merely treat them. He

One often hears of tragedy stalking unnoticed, in will of necessity, be equipped with superior training and

certain families, merely because its roots were not knowledge, and adapt himself to an entirely new pattern

detected early enough or not at all. The Family of society. He will steer clear of all those influences

Doctor has a grave responsibility in such situations, which tend to turn him into a superb technician fit only

Fitted for the task by training and practical experience for the practice of a soulless medicine and preserve the

as well as his intimate association with the members of truly humane character of his noble profession.

72

SUPPLEMENT

TO

EXAMINER.

THE

May 13, 1972

(’"'’I III O

and association with the activities of the Guild. She

vJVJfiLuLz

1>L VV O

a|so referred to dedicated work of Dr. Menino De

Our column ‘Guild News’ was held over for want of Souza in several spheres, civic, academic socio-cultural,

space in the past three issues. A brief account of some and political, particularly in “fund-raising” for several

of our activities during the last quarter is given here:— charitable and educational causes. His Eminence, in a

very eloquent reply, thanked the Guild for their greet

Annual Mass

ings, and good wishes. Tracing his associations with

The annual Thanksgiving Mass to celebrate the feast the Guild from 1938, he congratulated the Members

of St. Luke was held at the St. Xavier’s College Chapel

for maintaining a high standard which was due in large

on Sunday, 17th, October. The Rt. Rev. Dr. Simon

measure to the Presidents and the Committees. He

Pimenta, Auxiliary Bishop of Bombay was the celebrant said he was particularly happy to read the Guild

and preached a very impressive homily. The frater Bulletin regularly since 1949 ; Stressing that the bul

nal repast followed at the college cafeteria. Welcom letin was indeed ‘an accomplishment,’ he exhorted

ing Bishop Pimenta, Dr. A. C. Duarte-Monteiro, our members to see that it appeared uninterruptedly. Dr.

President said that in keeping with the past tradition

Menino thanked the President and Members of the

the Guild took the first opportunity to invite c—'"' Guild for their felicitations and good wishes. He said

new Auxiliary—representative of our Patron—as Chief he followed very keenly the activities of the Guild and

Guest. His Lordship then spoke in glowing terms of

congratulated the Committee for the progress they

the good work Bombay Catholic doctors were doing; he had made in recent years. He said Dr. Duartc-Monsaid he was happy to be admidst them and offer teiro, who was Guild President for four long years

prayers foi' the living and the deceased members at the was greatly responsible to give it a ‘new look’ and a

Thanksgiving Mass. Dr. C. J. Vas, Hon. Secretary c

“good shape.” Dr. C. J. Vas, the Secretary then pro

proposed the vote of thanks.

posed a vote of thanks.

The function—punctuated by recorded music re

Biennial Meeting

After breakfast, Members assembled at the College freshments, and ,variety

. of

t ~games for young and old—

ChaFr. proved

J^ovc^r to be

berquite

qijite an

^enjoyable

Council room. The retiring President was in the Chair,

enjoyable one_due primarily to

The Biennial report printed for the occasion reviewed

efforts of^ the office-bearers^ and assistance, of

the”activities of the Guild for the two years April 1969 Drs- Terence Fonseca, Miss Carole Duarte-Monteiro,

Duarte-Monteiro,

and

to March 1971. Tlie

The audfted

audited Statemem

Statement of

of Accounts,

Accounts, benzyl

Ucnzy!

Duarte-Monteiro,

and young

young Fonseca.

Fonseca,

as well as the Report were duly approved and adopted. This may henceforth turn out to be a regular feature

to -enable members

with

At the elections that followed, following Members cons- of the Guild,

*"

x- their families

meet

at

a

get-to-gether

during

X

’

mas

Season,

and orga

tituted the new Executive Committee :—

Dr. Juliet De Sa Souza, and Dr. Eustace J. nise sports, games, or X’mas-tree for children.

De Souza were elected President and Vice-President

respectively; Drs. C. J. Vas, (Mrs.) F. de Gouvea Pinto, FIFTH ASIAN CONGRESS FOR CATHOLIC

(Mrs.) J. N. F. Mathias and Terence Fonseca, were

DOCTORS

re-elected while Drs. Olaf Dias, Miss Charlotte de

(Bangkok—1972)

Quadros, Miss A.C.’Duarte-Monteiro, and F. Pinto de

The Fifth Asian Congress of Catholic Doctors will

Menezes were elected as new Members. Messrs. C. N.

Dr

A.

C.

ta

k

e place in Bangkok, early in December this year.

de Sa & Co. were re-appointed auditors, L.. x*. —

Duarte-Monteiro thereafter

thereafter thanked

thanked the

the retiring

retiring com

com-

recalled that on the occasion of the IV Asian

Duarte-Monteiro

mittee

for

their

assistance,

and

dedicated

service

Congress

held in October 1968, the assembly had

mittee for their assistance, and dedicated service

rendered during the two years that elapsed. He recal/ authorised the Catholic Physicians Guild

led that he was President for four years, and he felt of Thailand to organise and play host for the V Asian

happy to hand over the Guild to his successor in a very Congress.

■ • An unique feature of the filth Congress is that plans

good shape, judging from the activities

undertaken,

arc formulated to include it in the First

Ecumenical

financial oiauiuiy,

stability, juuuamy

solidarity cio

as enow

also relationship

llliauviai

iviauvnoiuu with

vn-cx*

.

.

the Junior Guild. He then vacated the Chair in favour Conference of the Catholic Organization and the

of the new Pr^identV^

ed all members for electing her unanimously, and as sored by the Asian Regional Executive Committee 01

sured them that she would maintain the high tradtions the FIAMC (International Federation of Catholic

referred * to the Medical Organisations) and the EACC (East Asian

established by her predecessors. She

S’

Duarte-Monteiro

Christian Conference), although with a separate prodedicated service rendered by Dr.

who gave a ffresh

1 1life,

’p full

r ” ofr vigour and colour to St.

A Tentative Agenda of the Fifth Asian Congress is

Luke’s Guild. The meeting terminated with a prayer

outlined here. Further particulars of the First Ecume

and vote of thanks to the Chairs.

nical Conference, as well as of the Asian Congress of

Cardinal Gracias and Dr. Menino de Souza. Catholic Doctors will be given in our subsequent issues.

Felicitated

Tentative Agenda.

A special function—Tea-party—was held in the Subjects for discussion

Junior Gymnasium Hall, St. Mary’s High SchoolI

’

—

- * - - — Status and Bylaws (as amended and

1.

F.I.A.M.C.

approved by the Convention 1970).

Mazagon to

felicitate

our

Patron, His EmiE

(fl) Membership problems (National Organization

nence, Valerian Cardinal Gracias, on his Episcopal

Silver Jubilee, an also Dr. Menino De Souza on his and Fees).

being the recipient of Papal Knighthood. This

(6) Regional Executive Committee problems (Meet

funciion was fixed for the 23rd October last, the 71st ings, cost for travelling, duties and obligations).

birthday of His Eminence. Unfortunately he was not

2. (fl) How does the work of your organisation

in town, as he had to attend all Sessions at the Synod benefit from F.I.A.M.C.

of Bishops from 30th September to 6th November.

(6) How can Catholic Medical Organisations in

On his return after five weeks he was caught—to put Asia benefit from one another.

(c) Closer relationship

between Doctors, Nurses, and

it in his words—“in the stream of deep anxiety for the

rela

future,” The Indo-Pak conflict and circumstances that Para-medical workers.

followed. Despite the fact that, 2nd of January hap- ~ 3. Closer relationship among Chirstian Medical

other func- Organisations in Asia.

paned to be a day when there were several

j

(a) Joint Regional Conference ?

tions in the city, St. Luke’s Medical fraternity mustered

(Z») Joint National Conference ?

quite a good strength with their families and children,

(c) Joint National Committee ?

in the nature of a large Family Gathering. The Presi

(rf) Joint Activities of National Level ?

dent Dr. Juliet De Sa Souza, gave expression of the

feelings of joy of Members, and offered felicitations on 4. (a) Election of Regional Executive Committee

behalf of the Guild to the Cardinal and chevalier for Asia.

De Souza. She referred to our Patron’s keen interest

(Z») VI Asian Congress—Where ? When ?

.

-■

3-

.

.

.

.

-

I

She

KHedi cal

U|

ORGAN OF THE CATHOLIC MZDICAL GUILD OF ST. LUKE, BOMBAY

Editorial Board

No. 83

Dr. A. C. Duarte-Monteiro

Dr. Thomas C. da Silva

Fr. Anthony Cordeiro

Dr. C. J. Vas

SUPPLEMENT TO THE EXAMINER

October

16,

1971

EDITORIAL

Our attention was drawn to the following comments that “the Hippocratic oath prohibits euthanasia, the

in favour of ‘mercy-killing’ in ‘The Times of India’ belief being that as long as there is a spark of life a

under the heading “Human vegetables” (Current man must be kept alive,” he concludes that there is

Topics, May 4th): “Thinking and talking about the certainly another side to the problem, and that the

unconventional may be distasteful to most people but issue needs to be openly debated in a calm manner.

this is an essential activity for man, the social and It will not be out of place to reproduce here what “The

intellectual animal. Twenty years ago free and open Himmat” writes in an editorial entitled “Of life and

discussions about sex or abortions were taboo, but Death,” wherein it compliments Pope Paul’s firm stand

thanks to the efforts of trend-setters such of the hypo on abortion and mercy killing :—

“The Vatican is to be complimented for its clear

crisy surrounding them has been stripped away. Eu

thanasia (or mercy-killing) is another subject which is enunciation on abortion and euthanasia. In a letter

mill considered by confirmists to be unmentionable.” to the International Federation of Catholic Medical

™In support of his plea, the critic lays stress on the Associations’ meeting in Washington, the Pope said :

views of Lord Ritchie-Calder, the noted British science ‘Abortion has been considered homicide since the first

centuries of the Church and nothing permits it to be

populariser and professor :— ,

_

“As a result of mental illness or degenerative diseases considered otherwise to-day.’

‘

" j some unfortunate people turn

such as multiple

sclerosis

tuin

for pUtting those who suffer from incurable or

inLu

zxnrujjva; when advanced age compounds then

their pajnfui diseases to death, His Holiness says :-j- ‘With

into zombies;

disabilities, they become little better than human vege out the consent of the sick person, euthanasia is mur

tables ...”

der. His consent would make it suicide.’

The learned professor poses the following question :—

Indeed a society where one satisfies one’s desires

“How merciful is it to keep them alive with all the

without any responsibility for the consequences, and

resources at the command of the modern medical prac

where the laws are created to encourage this irres

titioner ?”

ponsibility, cannot be considered a mature and civilised

Obviously the critic has considered man only from

the socio-intellectual viewpoint, disregarding the ethico- society.

As an answer to the above question posed by the

moral, and even the rational one. The Catholic view

point considered from the latter angle, teaches us to Professor, above referred to, we publish in this issue a

by the Chaplain of St. John’s Medical

respect human life, which is the basis for civilisation. talk given

_

Fortunately, in the same comments, while pointing out College, Bangalore.

EUTHANASIA

♦

By Fr. Denis Pereira, Chaplain, St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore

“Death” says Francois Mauriac, “is that terrible

ec r^EATH in America,” says a recent article in NEWSL/WEEK, April 6, “is no longer a metaphysical mys thing that happens to other people.” In a world

tery or a summons from the divine. Rather it is an frenzied with the pursuit of pleasure and comfort, ob

engineering problem of death’s managers—the physi sessed with its egotism, “death is an affront to every

cians, the morticians and statisticians in charge of citizens’ inalienable right to life, liberty and the pur

supervising nature’s planned obsolescence. To the suit of happiness.” (A. Toynbee speaking of ‘Death as

nation that devised the disposable diaper, the dead are being un-American’). But for the Christian, and the

only a bit more troublesome than other forms of human man of faith, death is not the end but a stage ip. living—

waste.” And a little later, quoting an American the process of dying is in reality the art of living mean

psychologist, the article goes on to say : “The dying ingfully in and through the process of dying. Death

no longer know what role to play. Most of them are is the gateway of eternal life. It is the moment at

already old and therefore worthless by our standards. which we ratify the fundamental options we make in

There’s simply no place for a human death when the life. If‘to live is to choose,’ then to die—if that death

dying person is regarded as a machine coming to a is human and meaningful—is also an act of choice in

simple words, a truly human death is one in which one

stop.” (Kastenbaum)

It would seem clear from the above that any dis ACCEPTS to die. This is what Dr. Elizabeth Kublercussion of euthanasia must necessarily be preceded by Ross, in her book ON DEATH AND DYING hints

ao-reement on a proper philosophy or theology, of at when she quotes one woman, who finally bowed to

death. What does death mean to us ? Is it ‘a machine the sentence of death after steadfastly refusing to ac

coming to a stop?’ Does it merely provide ‘a bit more cept the fact of her impending death, as saying: “I

troublesome form of human waste?’ or is it

in the think this is the miracle. I am ready now and not

eyes of us doctors, the great enemy against which we even afraid any more.” She died the following day.

must fight with all our resources, backed by patiently It is to be noted, however, that the acceptance of death

acquired knowledge,” and if so “is it reasonable that we is not to be taken to mean that the person has the right

should be indignant, that we should indulge in barren to impose death on himself, to ask another to shorten

irritation, before this inescapable condition of human his life, or to place in another the power to end it I We

have no right over life, even though we may have at

existence ?”

times a right to die ! And this brings us to the ques

tion of euthanasia.

♦ Talk to St. Luke’s Medical Guild, Bangalore, on April

Etymologically, the word EU-THANASIA means

22, 1970.

58

SUPPLEMENT TO THE

EXAMINER

October 16, 1971

dying well But that is not what it has come to mean

patient, in the doctor, in the lawyer, in the priest, in all

in legal* or medical parlance. From its original mean who share a responsibility for life.

ing of “dying well,” a perfectly innocuous and healthy

2. Man has a right to his own dignity as a person

philosophical value, it has come to mean “easy dying,” even in approaching death. Therefore, once the rea

which is not the same thing, for this implies medical sonable means to keep him in life have been exhausted,

intervention to cut short the process of living in order he is not bound to destroy his dignity by expecting to

to accelerate or rather induce death. Other words be kept alive without being able to live, to think, and

used to describe it are “mercy-killing,” “merciful to feel as person. No one is bound to ask for medica

release,“voluntary. euthanasia” or “easy death” tion that would prolong the agony of death. The same

(which, incidentally, is the name ol a society started in principle is valid for the community; its members are

England in 1935 to push euthanasia legislation through not bound to prolong the agony for a human being-.

Parliament), and “the termination of life by painless

3. There will always be complex situations and

means for the purpose of avoiding unnecessary suffer borderline cases where a clear moral judgment can

ing.” It is easy to see how ‘mercy killing’ can turn not be formed within the short time available . In this

into ‘convenient killing’—but let me not anticipate.

case we have to respect those who, animated by the

A. EUTHANASIA in the strict sense means : “to first two principles, make a genuine effort to bring

cause death (or to assist in causing death) to a conscious, about the best decision even though they may fail to

certainly incurable patient who requests that his agony find it there and then. Yet the effort itself was good

(physical or psychical suffering) be terminated by a and the resulting situation should be accepted as the

calm and painless death.” Here we can distinguish only reasonable one in the circumstances.” (L.

between ‘direct euthanasia’, i.e. where the assistance is Orsey^S.J.)

rendered intending death. This is murder, or co

4. “I would urge that we promote the idea of bene

operating assisting in suicide, or both, and is never mori, a dignified death, in the dying patient. There is

allowed. And we can speak of ‘indirect euthanasia’ no need to prolong the dying process, nor is there any

or the administration of treatment {e.g. to alleviating moral or medical justification for doing so. Eutha

pain) with as a side effect, the acceleration of death. nasia, that is the employment of direct measures to^fe

This last would better not be called ‘euthanasia’ at all. shorten life is never justified. ‘Bene mori’ that i^J

J. Fletcher calls this antidysthamasia’ (not prolonging allowing the patient to die peaceably and in dignity

the process of dying). “It is not euthanasia to give always justified.” (J. R. Cavanagh)

a dying person sedatives merely for the alleviation of

[JV.R.—This conclusion presupposes (1). that all con

pain even to the extent of depriving the patient of sense cerned act in accordance with the will of the patient; (2).

and reason, when this extreme measure is judged neces that the patient is dying. The dying process is the time

sary. Such sedatives should not be given before the in the course of an irreversible illness when treatment

patient is properly prepared for death, nor should they will no longer influence it. Death is inevitable.]

be given to patients who are able and willing to endure

B. EUTHANASIA IN A WIDER SENSE: Eutha

suffering for spiritual motives.” (Directives Catholic nasia in a wider sense is less complicated to deal with

Hospital Association, U.S. and Canada). It is ob ethically. It includes:

vious from this directive that the person must be helped

(a) To cause death, at the instigation of pity, to an

to live meaningfully through the process of dying. unconscious dying person, to monsters, the seriously

The real problem is: to what extent must a doctor/pa- insane, etc.

tient prolong life? Always and at any cost ? We

(Z») To cause death, for the sake of society, to a socould perhaps be helped if we d

‘

distinguish

between cially dangerous person, to persons, in general, who

‘Prolonging life’ and ‘prolonging the biological process cannot live a moral life within society (the so-called

of dying’; or to put it in other words, we could visualise ‘eugenic deaths’). This causing death for the sake of

cases in which the prolongation

life may'

“ r „ of

, biological

i

society may go to the extent of disposing of “useless”

not really be living meaningfully, whereas acceptance persons, the aged, etc.

of death may be^ living this moment as a human being’

One can easily see, especially in the light of the Nazi

even though biological life is shortened (of course with atrocities of World War II, how fraught with terrible

out being directly terminated, which is plain murder consequences the admission of such a principle woulc

even if done with the consent of the patient.)

be ! “From a purely medical point of view shortening

Take the case of a dying person who is ready to die or taking the life of a patient for the relief of pain is

and wants to die. He is suffering. He is surrounded unnecessary. Moreover, it is a confession'of professional

by medical apparatus. He has hardly any contact failure or ignorance” (Dr. Graham). Further, “the

with his environment, his friends, his family. His practice of euthanasia would lessen the confidence of

children are kept away, and visitors not allowed. patients in their physicians, for the patient who was

Would not a doctor be justified in instructing the gravely ill might readily fear that his physician would

nurse to take away the instruments and allow the chil judge his case incurable and so administer poison to

dren to be with the father even if this may well mean end his life” (Healy). One could imagine the con

an earlier death? Indeed, this may well be the best fidence one would have in confessional practice if the

way to help a person to live—through the process of priests were sometimes justified in betraying the con

dying meaningfully, even though the duration of the fessional secret. And lastly, as B. Bonhoeffer who was

process is shorter. Keeping a person alive is not neces himself executed in a German prison camp, put it:

sarily helping him to live, for living means more than ‘•‘we cannot ignore the fact that precisely the supposedly

i.:/

/

’ survival.

.........................................

■’

'

biological

And in this case the

duty

of living worthless life of the incurable evokes Irom the healthy,

1 ----- well. (The question- as to

■