National Public Hearing on Right to Health Care

Item

- Title

- National Public Hearing on Right to Health Care

- extracted text

-

RF_L_7_A_SUDHA.

L~

Programme

National Public Hearing on Right to Health Care

Jointly organised by the National Human Rights Commission and

Jan Swasthya Abhiyan

(New Delhi: 16-17 December 2004)

[Venue: Jacaranda, India Habitat Centre]

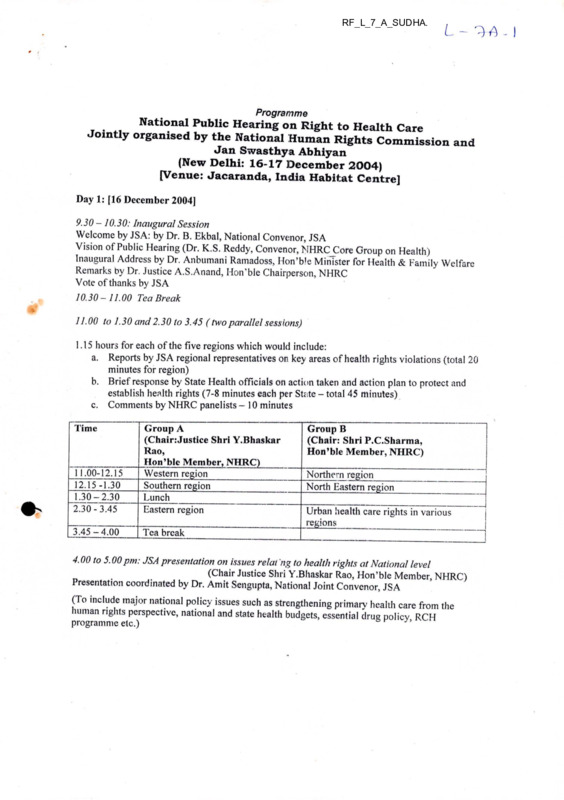

Day 1: [16 December 2004]

9.30-10.30: Inaugural Session

Welcome by JSA: by Dr. B. Ekbal, National Convenor, JSA

Vision of Public Hearing (Dr. K.S. Reddy, Convenor, NHRCCore Group on Health)

Inaugural Address by Dr. Anbumani Ramadoss, Hon’ble Minister for Health & Family Welfare

Remarks by Dr. Justice A.S.Anand, Hon’ble Chairperson, NHRC

Vote of thanks by JSA

10.30 - 11.00 Tea Break

11.00 to 1.30 and 2.30 to 3.45 (two parallel sessions)

1.15 hours for each of the five regions which would include:

a. Reports by JSA regional representatives on key areas of health rights violations (total 20

minutes for region)

b. Brief response by State Llealth officials on action taken and action plan to protect and

establish health rights (7-8 minutes each per State - total 45 minutes)

c. Comments by NHRC panelists - 10 minutes

12.15-1.30

1.30- 2.30

2.30- 3.45

Group A

(Chair: Justice Shri Y.Bhaskar

Rao,

Hon’ble Member, NHRC)

Western region__________

Southern region____________

Lunch___________

Eastern region

3.45-4.00

Tea break

Time

Tl.00-12 J 5

Group B

(Chair: Shri P.C.Sharma,

Hon’ble Member, NHRC)

Northern region

North Eastern region

Urban health care rights in various

regions

4.00 to 5.00 pm: JSA presentation on issues relat 'ng to health rights at National level

(Cllair Justice Shri Y.Bhaskar Rao, Hon’ble Member, NHRC)

Presentation coordinated by Dr. Am it Sengupta, National Joint Convenor, JSA

(To include major national policy issues such as strengthening primarv health care from the

human rights perspective, national and state health budgets, essential drug policy RCH

programme etc.)

- I

Day 2: |17 December 2004]

9.30 to 12.30: Parallel sessions on key health rights issues, 45 minutes each

(JSA presentation 20 minutes, discussion 15 minutes, panelist comments 10 minutes)

Group A: 9.30 to 11.00\ Session 1

(Smt. Reva Nayyar, Secretary, Women & Child Development to chair

Shri S.S.Brar, Joint Secretary (RCH), Deptt. of Family Welfare.

Women’s right to health care

Children’s right to health care

Session 2: 11.00 to 12.30: Shri Chaman Lal, Special Rapporteur, NHRC to Chair

Dr.P.K.Dave, NHRC Expert Group on Emergency Medical Care:Co-chair

(subject to confirmation)

Mental Health Rights

Health Rights in situations of conflict and displacement

Group B: Session 1 9.30 to 11.00: Shri V.K. Arora, Addl. DG, Health Services to chair

Dr. D. Banerjee, Vice-Chairperson, JSA-co-chair

Right to essential drugs

Health rights in the context of the Private medical sector

Session 2: 11.00 to 12.30 : (Dr S.Y.Quraishi, Additional Secretary

& Project Director, NACO to chair)

Dr. N.H.Antia, Chairperson, NHRC Core Group on Health: co-chair)

Health rights in the context of the HIV-AIDS

Occupational and environmental health rights

12.30-1.30

Lunch

1.30 to 2.15: Plenary presentation by ISA Rapporteurs [Dr. Vandana Prasad and Mr. Amitava

Guha] on the key health rights issues emerging from two parallel sessions

[Chair: Shri S.S.Brar, Joint Secretary' (RCH), Deptt. of Family Welfare to chair]

2.30 to 4.15: Towards a National action plan to establish, fulfil and monitor the Right to HealthCare

1. Statement by Mr. Paul Hunt, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Right to Health [Ms.

N.B. Sarojini to read oufthe Statement]

2. People’s actions to establish the Right to Health Care (Dr. Abhay Shukla, National Joint

Convenor, JSA)

3. JSA-NHRC joint presentation on a National action plan to establish, fulfil and monitor

the Right to Health Care (Shri Y.S.R. Murthy, Deputy Secretary (Research), NHRC and

Dr. T. Sundararaman, National Joint Convenor, JSA)

4. Responses from Union Health Ministry (Shri P. Hota, Secretary, Health & Family

Welfare)

5. Concluding remarks by Dr. Justice A.S. Anand, Hon’ble Chairperson, NHRC

6. Vote of thanks by Shri Y.S.R. Murthy, Deputy Secretary (Research), NHRC

National Public Hearing on the right to health care

Jointly organized by the National Human Rights Commission and Jan Swasthya Abhiyan

The programme on started on time with the welcome address delivered by Dr. Ikbal convener of

JSA. He welcomed the dignitaries and the delegates. Dr. Ikbal in his address mentioned this event

is an historical one as this is the first time a Human Rights Commission was collaborating with

civil society agencies in addressing a issue.

Followed by the welcome address Dr. Ikbal shared the vision of public hearing/. Dr. Srinath Reddy

in his address mentioned that right to health is a human right and denial of access to health care is

violation of human right. He mentioned the need for comprehensive primary health care approach

in meeting the health needs of citizens of this country. He also mentioned that the present

understanding that the public private partnership for the benefit of the poor needs a critical analysis.

Finally he said community participation is crucial in the success of any programme. He concluded

his speech by saying that the goal of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan’s Right to Health Care campaign is to

strengthen accessibility of public health services.

Followed by Dr. Reddy the Honrable Minister for health and family welfare Dr. Anbumani

Ramdoss delivered the inaugural address. Dr. Ramdass in his address said right to health care is*

un amental right. He referred to the constitution of WHO which says; that every one has the right

to enjoy health at the highest attainable standard. He also referred to the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights by the General Assembly of the United Nations, which says that all human beings

are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

\(

He referred to the WHO's definition of health and said health care is complex issue. He mentioned

the need to balance between the various aspects in health care, which include curative preventive

promitive. He also mentioned the determinants of health such as water, sanitation and nutrition He

said the rural population put together to with the urban poor constitute 90% of the population to

whom the health care is important, he pointed the need for changes in the health care delivery

system, he said he was particularly concerned about the quality. He mentioned about the doctor

patient ratio in India he said, even if we put together the practitioners of all system of medicine the

doctor patient ratio in India comes one doctor per 800 population. He said the hospital beds

available at present in the country, which is about one million barely sufficient. He justified the

need for public private partnership by mentioning that the public sector contribution in health care

is only 17/o, he emphasized the need for streamlining. Here he mentioned about the need for

accreditation of health care facilities that area available in the county and the need for health

regulatory authority. He also mentioned about need for essential drugs guidelines and said he is

concerned about particularly about the list not being available regarding the life saving drugs

While referring to private sector he mentioned about the need for checking quackery.

^delineatinfthTneeds 3''

reCOmmendations Put forth b> JSA't is commendable for the efforts

creation. He said he is also concerned about safe mother hood by which the MMR could be brought

down he said he particularly concerned that MMR is stagnant for the past three decades He said

that the prime minister is concerned about two key issues the health and education which are alike

Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. A summary of the book -Alcohol & Public Policy GroupPage 1 of 10

I

THE GLOBE

,

X ' G1 b a I A i c o ii o t P o H c y A M i.

■■■

Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. A summary of the bo

Alcohol & Public policy Group

Alcohol Policy and The Public Good, published in 1994, was a modern landmark in ah

policy. Here, with the kind permission of the editor of the journal Addiction, we repr<

summary of its successor. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity — Research and public pi

(Babor et al. 2003). The first part of the book describes why alcohol is no ordinary

commodity, and presents epidemiological data on the global burden of alcohol-relate

problems. The second part of the book reviews the scientific evidence for strategies

interventions designed to prevent or minimise alcohol-related harm: pricing and taxi

regulating the physical availability of alcohol, modifying the drinking context, drinkii

counter measures, regulating alcohol promotion, education and persuasion strategic

treatment services. The final Section considers the policy making process on the loca

national and international levels, and provides a synthesis of evidence-based strateg

interventions from a policy perspective.

Setting the policy agenda

The purpose of this volume is to describe recent advances in alcohol research that have direct

to alcohol policy on the local, national and international levels. Alcohol policies serve the inter

public health through their impact on drinking patterns, the drinking environment and the hee

services available to treat problem drinkers. Public health concepts provide an important vehh

manage the health of populations n relation to the use and misuse of beverage alcohol by hel

communities and nation states to design better preventative and curative services. Alcohol po

been implemented throughout histpry to minimise the effects of alcohol on the health and saf<

population but only recently have ese strategies and interventions been evaluated scientific.

No ordinary commodity

In many countries, the production and sale of alcoholic beverages generates profits for farmer

manufacturers, advertisers and investors. Alcohol provides employment for people in bars anc

restaurants, brings in foreign curre icy for exported beverages and generates tax revenues for

government. Alcoholic beverages a-e, by any reckoning, an important, economically embedde

commodity.

However, the benefits connected w th the production, sale and use of this commodity come at

enormous cost to society. Three imbortant mechanisms explain alcohol's ability to cause medi

psychological and social harm:

• (1) physical toxicity

• (2) intoxication and

• (3) dependence.

Alcohol is a toxic substance in terms of its direct and indirect effects on a wide range of body •

http://www.ias.org.uk/publications/theglobe/0 5issue3/globe0303_p3.html

12/22/2004

He also mentioned about the need to work towards checking the trend regarding HIV/AIDS in

India. He said there is need for legislative measures in checking discrimination against people

affected by HIV/AIDS.

He said his government is concerned about health that is the reason why the new programme is

being planned ie the rural health mission in 17 states, which are backwards. About the health

budget he said that the governement would increase from the present .9% to 2%.

Finally he said that the judiciary has created havoc in medical education and he would be interested

to discus the same with the chairperson of NHRC.

Justice Anand in his remark said that India is welfare state therefore it is the duty of the government

to provide health care for all its citizens. He referred to article 21, which talks about right to life and

argued right to health leads to right to life. He said without addressing the following three areas it is

difficult to achieve development; he referred to poverty, health care and education. He illustrated a

case where a patient in West Bengal was denied health care in many places. He also expressed his

concerned about the health indictors, though life expectancy has gone up but indicators such as

IMR and MMR being stagnated. Regarding access to essential drugs he said only 35%of the

population are accessible. Regarding health budget he said it should go upto 3-5%. The inagural

session came to an end by vote of thanks by Dr.Sarojini of Sama.

Living dangerously: The World Health Report, 2002

Page 3 of 3

"Legislation enables risks to health to be reduced in the workplace and on the roads, whether

the wearing of a safety helmet in a factory or a seat belt in a car. Sometimes laws, education

persuasion combine to dimiroish risks, as with health warnings on cigarette packets, bans on t

advertising, and restrictions on the sale of alcohol."

The report is particularly concerned with the increase in alcohol consumption in poorer, devek

countries: "All of these risk factors -- blood pressure, cholesterol, tobacco, alcohol and obesity

the diseases linked to them ard well known to wealthy societies. The real drama is that they r

increasingly dominate in low mortality developing countries where they create a double burde

of the infectious diseases that always have afflicted poorer countries. They are even becominc

prevalent in high mortality developing countries." |

The Globe (links to previous issues)

This issue of The Globe (link to index)

\

(Global Alcohol Policy Alliance|Alliance House

12 Caxton Streetj London | SW1H 0QS| Tel: 0207 222 40011 Contact Gapa

Copyright 2003

http://www.ias.org.uk/publications/theglobe/02issue4/globe0204_p3.html

Home

12/22/2004

L- ^^3

WESTERN REGION PUBLIC HEARING

ON

RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

29 JULY 2004

BHOPAL, MADHYA PRADESH

Recommendations from the Public Hearing

Legal Measures

Enactment of a State Public Health Act in each state, which would outline the

mandatory health care sen ices which must be made available to the people as a right at

various levels of the public health system. This act would specify which services and

standards of care must be made available at the community, sub-centre, PHC, CHC,

Sub-district and District hospital levels, as well as the preventive and promotive

measures that the government would undertake.

> Enactment of a Clinical Establishments Regulation Act in each state to ensure

minimum standards, adherence to standard treatment guidelines and ceilings for costs of

essential medical services in the private sector. For example, the Bombay Nursing

Home Regulation Act 1949 - Maharashtra, may be substantially modified and

improved to effectively regulate the quality of private medical services in the state.

> Private practice presently allowed to Government health care providers should be legally

banned, and those doing it should be promptly punished.

Independent Social Monitoring and Redressal System

> Preparing lists ofspecific services and supplies that would be guaranteed at all levels of

the public health system; wide dissemination and public display of these lists in all

relevant facilities.

> A system of regular independent monitoring of the functioning of the health care

system at all levels - encompassing state, district, city / town, block and community

levels. Representatives of state level health sector coalitions, social organizations

involved in health-work along with representations from the beneficiary population, in

conjunction with relevant health officials, should be entrusted with this independent

monitoring.

> An effective redressal mechanism at block, district and state levels for persons with

complaints regarding quality of health care, or those who have suffered denial in any

form. This mechanism should be transparent, should involve health sector coalitions and

social organizations, and should be independently reviewed on a periodic basis. A

department or position of Swasthya Lok Ayukta may be created especially to address

complaints and to ensure that rational guidelines are followed.

>

Budgetary Measures

Immediate doubling of public health-care expenditure by State governments and

further increase to at least 3% of the State Domestic Product in next five years in

keeping with provisions in the Common Minimum Programme.

1

Per capita allocation for public health care for rural areas should be increased and

made equal to that for urban areas.

> Immediate doubling of drug budget for rural health facilities.

>

Measures to improve functioning of the health system and attention to special groups

Standard Treatment Protocols should be implemented regarding care to be provided at

various levels of Health Care Facilities, so that the necessary quality is maintained.

> The full range of comprehensive health services should be guaranteed at all levels of

the public health system, these health services must be ensured as a right. In exceptional

cases of failure by the public system to provide any such health service to a patient, there

should be a mechanism wherein care may sought from designated private facilities

following standard treatment protocols. Such registered and regulated facilities could

give relevant care to the patient, and the state could reimburse them at standard rates,

ensuring that the patient is not deprived of any essential care at time of need.

> Guaranteed availability of essential drugs relevant to the level of service, in all public

health facilities. A mechanism to ensure that if any health care facility is unable to

provide any of the essential drugs that are supposed to be available at that level of health

care, the expenses incurred by the patient on this ‘outside prescription’ should be

promptly reimbursed. All health care providers in both public and private sector should

prescribe according to the essential drug list, and prescribe drugs by their generic

names.

> A comprehensive statewide policy to provide Primary Health Services to urban areas.

Adequate health services need to be provided in all cities and small towns. Expansion of

Urban health care infrastructure, especially of health posts and of outreach health

services keeping in mind the needs of the growing slum population.

> Filling of all the vacant posts and construction of buildings for Sub-centres and other

facilities.

> A new scheme to provide a Community Health Worker in every village or habitation of

the state should be launched. As part of such a scheme, in tribal areas the Community

Health Worker should be operative at hamlet level. For example, in Maharashtra under

the Pada Swayam Sevak scheme, the full potential of the Pada Swayam Sevaks (PSSs),

in tribal districts now needs to be realised by upgrading their role as has been done in

innovative projects. This may be done by ensuring substantially upgraded training,

integration of curative and preventive roles and preference being given to women in the

selection process.

> Regarding womenfs access to health care, availability of all services in a woman

friendly and sensitive manner at public health facilities must be ensured. This should

include assured round the clock maternity services at Sub-centre and PHC level; assured

emergency obstetric and neonatal care at CHC level; facility of diagnosis and treatment

of Reproductive Tract Infections and of infertility, and woman friendly, quality abortion

services. Simultaneously, quality health care for women beyond reproductive health

such as availability of services by women doctors; supply of iron tablets to all anaemic

women irrespective of being pregnant or not; care for victims of domestic violence, and

other services relevant to women’s health must be ensured.

> Training of staff to increase its sensitivity to groups with special health care needs like

women, children, old people, the mentally and physically challenged.

> Greater sensitivity towards mentally unwell, institutionalised patients, provisions for

proper counseling. Provisions for consent procedures, facilities for legal aid and

measures for rehabilitation and family contact.

>

2

>

All coercive measures, including incentives and disincentives for limiting family size,

which result in violations of human rights, must be stopped immediately.

The norms for maintaining quality of service during tubectomy operations must be

strictly followed. For any violation, of these norms responsible persons must be suitably

held accountable and punished. The ‘camp approach', which often results in poor

quality operative care and violation of various aspects of women’s rights, needs to be

seriously reviewed immediately.

>

The other recommendations are:

1.

Public Health facilities should guarantee a Health Centre within walkable

distance with qualified doctors and infrastructure.

2.

Facility to refer patients with serious ailments to specialized hospitals including

transport (Ambulance or Vehicles) with minimum facilities to give life sustaining

treatment during transit.

3. Drugs availability at reasonable rate within reach of common man

a) Supply of quality drugs

b) Ban of spurious drugs envisaging violation as grave crime entailing severe

punishment.

c) There should be a Drug Price control Policy,

Violators should be held

accountable, including penal action.

4.

Social responsibility of providing 10% of free service or service on nominal

charges fixed by the State should be made mandatory for all Corporate Hospitals

and Private Nursing Homes with regular accountability entrusted to a body

created by the State to monitor the system.

>

Visit of Mobile Hospitals with adequate infrastructure and doctors, at least twice a

month, to a village to treat the ailing people where there is no hospital facility and

refer serious patients to Health Centres or District hospitals.

>

To examine the children in all primary and middle schools regularly twice a year

and send report to DMs and/or Collectors, along with names and attestation of Head

Master and Sarpanchs of the village.

>

The diet specialist doctors should prepare a list of food articles available in local

area and prepare a chart showing the proportions of food articles to be taken by

3

children, young boys and girls, pregnant women, old citizens and women from

weaker sections, etc. for strengthening the nutrition of body and to end malnutrition.

This exercise should be made every year and published in local language, put up on

Notice Board of Panchayat offices, Schools and Hospitals of every village.

>

It should alsQ: publish that the parents should examine their children regarding their

hearing problems, vision, speech, etc. immediately they notice any one symptom so

that at young age itself the same could be treated.

>

The Gram Panchayats (full body) and recognized Non-Governmental Organisations

at village, taluq, and district levels should send quarterly reports about the

functioning of hospitals in their village stating presence or absence of doctors, the

period for which one is absent or no doctor is posted at all, including women

doctors, nurses, other medical staff of hospital and availability of drugs to the

District Medical Officer, Collector or Commissioner, Director of Medical Services

of the State and one to the Health Secretary.

>

A Monitoring body should be formed with Chief Secretary as Chairperson, Health

Secretary, Director of Medical Services and Secretary in-charge of Vigilance as

Members to scrutinize the reports and suggest action to be taken immediately as

time-bound programmes. The reports of Monitoring Committees should be placed

before the Assembly every six months for consideration of elected representatives.

4

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION AND JAN SWASTHYA

ABHIYAN

SOUTHERN REGION PUBLIC HEARING ON THE RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

HELD ON 29™ AUGUST, 2004 AT CHENNAI

KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN RESPONSE TO ORAL AND

WRITTEN TESTIMONIES

for the States of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Pondicherry

1. Access to Primary Health Care through the public sector health system

Primary health care is understood in a more limited way as services made available

through Sub-Centre (SCs), Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and Community Health

Centres (CHCs).

•

Pondichery received positive community response regarding the availability and

quality of primary health care services.

•

There were no complaints from Kerala though issues regarding essential drugs,

environmental health and trauma care were raised which come within a broader

understanding of primary health care(covered in item 5,6,7).

•

In Karnataka and AP the irrational siting of PHCs (possibly under political

pressure) made access to health care very difficult and sometimes impossible.

Some of the farthest villages were 40 - 50 kms away, and in other cases there

was no easy bus access to PHCs / SCs. In AP subcentres that were supposed to be

there were non-existent on non-functional. In Tamilnadu, Karnataka and AP

there were problems with regard to quality of care, referrals and staff attitudes.

Recommendation 1.

•

The siting / distribution and physical accessibility of PHCs and subcentes must be

ensured. They should provide good quality services during the prescribed

timings. Indicators and mechanisms for monitoring quality of care need to be

developed and used. No money should be taken for services that are to be

provided free. The citizens charter for services at PHCs should be prominently

displayed and implemented. Staff vacancies need to be filled up and staff needs

such as quarters, toilets, water supply and electricity need to be ensured.

Adequate provision of medicines, laboratory equipment and consumables,

registers etc is a basic requirement. Maintaining staff motivation through good

management practices will help improve the quality of services and to foster a

relationship of mutual respect and trust between providers and people.

1

•

State and Central health budgets would need to be increased as per the National

Health Policy 2002 and the Common Minimum Programme commitments.

Distribution of the health budget between the primary, secondary and tertiary

levels of care would also need to follow norms, such as 65%, 20% and 15%

respectively.

2. Urban health care

There were several instances where the urban poor suffered adversely due to lack of

access to health care and to basic determinants such as lack of access to safe potable

water and sanitation.

Recommendation 2.

•

The urban poor should have access not just to family welfare services but to

comprehensive primary health care through health centres which cater to 50,000

people.

•

Provision of safe potable water and sanitation is necessary to prevent morbidity

and mortality due to water-borne diseases.

•

User fees in institutions like NIMHANS need to be reconsidered as they have

resulted in lack of access to care. Urban poor families including migrants often

do not have ration cards and BPL cards. Rural and urban poor patients coming

from other places do not carry all these cards (if they have them) when they come

to hospital in times of illness.

•

Corruption and rude behaviour in institutions like Kidwai Institute of Oncology

as well as in IPP VIII Centres need to be checked.

•

Pourakarmikas from Hyderabad Metro Water Works and those in other cities and

towns need to have access to basic preventive, promotive and curative care,

including safety gear and equipment.

3. Private sector health care

The case of death of a teenaged girl following treatment of gastroenteritis by a

private practitioner (with an unusual medical qualification) raised the need for:

Recommendation 3.

•

Regulation of the private medical/health sector by government and professional

bodies. Liability of practitioners and payment of compensation where death or

disability results from improper treatment or negligence.

2

•

Unnecessary surgeries such as hysterectomies

be curbed.

as was reported from AP should

4. Women’s access to health care and gender concerns

It was painful to hear testimonies from women about the poor treatment they received

even for ANC/PNC and family planning services and the lack of respect and privacy.

Recommendation 4

•

The camp approach should not be used for tubectomices / sterilizations. Good

quality , safe contraceptives need to be available in health centres at different

levels, with adequate facilities for screening follow-up and discussion about

possible side-effects. Patient feedback on quality of care should be regularly

taken and acted upon.

•

Medical and health care should be made available to women and children as close

to their residence as possible.

•

Privacy and respect should be ensured for women and girls during medical

examination and treatment.

•

The large number of hysterectomies at young ages taking place in AP without

adequate medical justification needs to be urgently looked into and curbed. The

commercialization of medical practice does not benefit persons or families and

requires social control.

•

There should be 24 hour PHCs functioning in every taluk for emergency obstetric

care and CHCs should have gynecologists and anesthetists. Due to the shortage

of anaesthetists medical officers with a 3 - 6 month training in aneasthesia could

be authorized to give anaesthesia.

5. Environment and Health

Strong testimonies were presented from Kerala, Tamilnadu and AP on the adverse

impact on human health resulting from exposure to toxins from industries / factories,

and pesticides. This problem exists throughout the country.

Recommendation 5.

•

The Department of Health at state and central level needs to have structural

mechanisms through which it can function along with other agencies likes the

pollution control board, ministry of environment and forests etc. to implement

regulatory and preventive measures, and to provide for occupational health and

safety, as well as access to medical care where environmental injury has

occurred. In short there is need for a public health response to environmental

health problems.

3

6. Access to Essential Medicines and rational therapeutics

The use of irrational and sometimes harmful, banned and bannable medicinal drugs

and preparations was raised as an issue of concern in Kerala. This problem exists in

all states.

Recommendation 6.

•

Rational drug' policies, essential drug lists standard treatment guidelines and

formularies need to be adopted in the public and private sector, and more

importantly they should be used and regularly updated.

Existing and new mechanisms for continuing education of medical practioners

and allied health professionals need to be actively used for this purpose.

•

Measures to increase consumer awareness and good pharmacy practice need to be

widely instituted.

7. Trauma Care

This came up strongly from Kerala, but is applicable in all states.

Recommendation 7.

•

With the rising number of traffic and other accidents early trauma care using

standard protocols need to be ensured through provision of infrastructure and

training. Preventive measures such as use of helmets and seat-belts should be

mandatory.

8. Mental Health

The following problems were experienced by groups working in the different states lack ol access to mental health care by rural poor due to centralized mental health

care available mainly in city and town based institutions; stigma, discrimination and

abuse; lack of medical and health personnel with adequate training in mental health;

non-availability of drugs; lack of public awareness about mental health

Recommendation 8.

•

Medical and psychosocial care ;and support for persons with mental illness should

be available in a decentralized manner. This will require adequate training and

continuing education,

Public awareness and sensitivity also needs to be

increased.

9. Public Health issues

Other public health issues raised included prevalence of Vit. A deficiency (AP);

discrimination faced by patients with AIDS who required surgery (AP); death of TB

patients due to lack of access to treatment (Karnataka).

4

Recommendation 9.

National guidelines regarding these public health issues need to be followed.

Increasing community involvement and feeling of community ownership of health

institutions and programmes would help in better outreach and quality. Training and

involvement of community health workers / social health activists would provide a

valuable link.

10. Follow-up and monitoring of implementation of recommendations arising from

the Public Hearings on the Right to Health Care.

Recommendation 9.

•

A mechanism needs to be established at state level for joint monitoring by the Jan

Swasthya Abhiyan and officials from the state department of health regarding the

follow-up of recommendations. They will report to the NHRC. NHRC officials

may also visit to observe and monitor the follow-up whenever necessary.

Accountability and communication with the local communities is of greatest

importance.

afc * * j|c * $ 9(c

5

NORTHERN REGION PUBLIC HEARING

ON

RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

26th SEPTEMBER, 2004

LUCKNOW, UTTAR PRADESH

Recommendations at a Glance

Recommendations by The Northern Region Public Hearing, NHRC-Jan Swasthya

Abhiyan:

Regulation and Monitoring

• Enactment of State Public Health Acts, which would outline the mandatory health

care services that would be guaranteed at all levels of public health system as a

right.

• Regulatory mechanism at state level to ensure the quality of private medical

services by implementing minimum standards standard treatment guidelines and

ceiling for costs of essential medical services.

• A system of regular independent review of the functioning of the public health

system at state, district and community levels. This review ,every 3 to 6 months

should involve JSA and other social representatives.

• An effective redressal mechanism for persons or communities who have suffered

denial of health care in any form .This mechanism should involve JSA and other

social representatives.

Strengthening public health system

• Tripling the public health budget in next five years, to increase it to at least 3% of

SDP as per the Common minimum programme.

• Allocation of adequate budget for drugs, which would involve at least doubling of

state drug budgets. Guarantee of essential drug at all levels.

• Provision of adequate infrastructure including buildings, equipments ,vehicles and

maintenance for all public health facilities. Filling of all vacant posts at various

levels.

• Women are often denied access to health care because of insensitive attitude of

health staff and inadequate facilities. Keeping this in mind .availability of ad

health services for both reproductive and non reproductive health needs to be

guaranteed women friendly manner at all public health facilities.

• Universalisation of ICDS, including strengthening of child health related

services. Guarantee of immunization, nutritional supplementation and other

essential preventive child health services. Ensuring school health services and

mid-day meals.

•

•

•

•

A comprehensive statewide policy to provide primary health services to urban

areas. Expansion of Urban Health care infrastructure, especially of health posts

and of outreach health services.

A new scheme to provide a community health worker in every village of the state

should be launched. This should effectively involve communities,Panchayats and

local organizations.

Regarding mental health, much greater sensitivity towards mentally unwell,

institutionalized patients , provisions for proper counseling and measures for

rehabilitation and family contact.

All coercive measures for limiting family size must be stopped immediately. The

tubectomy camp approach, which often results in poor quality operative care and

violation of various aspects of women’s rights, needs to be reviewed.

State level recommendations:

Recommendations for Health Sendees in Delhi

Uhere are three over-arching issues applicable to all public health institutions:

a. With Delhi being a city-state and the national capital with a historical

development of multiple local bodies there is a multiplicity of providers. The

respective roles of Govt, of India, Govt, of Delhi and the local bodies need to be

clearly spelt out and well coordinated.

b. There is a need to rationalize and integrate the functioning of the public health

agencies. The Dr. Pattanayak Committee had given its recommendations for

restructuring the health services of the Municipal Corporation o Delhi in 2001-02

but it has largely been ignored. There is a need to consider its implementation.

c. Health personnel (including doctors) need to be in position through regular

appointments and their performance should be ensured through administrative and

community regulatory mechanisms.

2. Strengthening of Primary Level Institutions

a. Peripheral areas lack institutional coverage; these areas require special attention

and should be expanded

b. Equipment and infrastructure backup should be available in dispensaries and

PHCs including laboratory support and emergency backup sen ices

c . Vacant posts of personnel should be filled up, their allocation rationalized and

regular attendance and performance ensured

d. The Maternal & Child Welfare Centres and Family Welfare Centres should

provide full range of primary gynaecologic and paediatric sen ices.

e. The sub-centre network should e expanded in rural areas that should be linked to

the respective PHCs.

f. Public health programmes and personnel need to be reorganized/restructured and

these institutions need to integrate with the local curative institutions.

g. Involvement of local communities (through Local Health Committees, for

example) in local level planning and implementation of services; the departments

of health, water, sanitation and social welfare should be involved and accountable

to these local committees.

3. Secondary Level Hospitals

a. 100 bedded hospitals and 30/40 bedded colony hospitals should have full range of

secondary level services operational from its inception; hospitals like Sanjay

Gandhi Hospital, Mangolpuri took more than 10 years to develop all services the present new hospitals are in a similar state.

b. The secondary level institutions should be linked with the local primary level

institutions with a proper referral mechanism.

c . Secondary level specialty services and requisite equipment and supplies should be

available.

d. Rational prescribing practices should be implemented.

e. Special emphasis needs to be given on environmental and occupational health

problems

4.1 ertiary Level Hospitals (all agencies)

a. The above measures will decrease unnecessary overload at this level.

b. Adequate supply of drugs and supplies, based on rational drug formularies,‘should

be available.

c. Internal medical audit mechanisms should be instituted.

5. With strengthening of these three levels we should

«

be able to ensure that social security

services like CGHS, Railways and ESIC should not be sending their patients to private

corporate institutions.

6. a. Reporting of notifiable diseases and medical certification of deaths should be strictly

implemented by all institutions (government and private) and private practitioners.

b. Public should have access to information about availability of services at each level,

availability of beds at a point of time; other linkages like networking of blood banks are

also necessary.

7. a. Independent monitoring of health services through social audit

b. Grievance redressal mechanisms within each agency providing public health services.

8. There are 4 state level medical colleges and one national apex institute (ARMS) There

should not be any more increase in medical colleges. The content of medical education

needs to be appropriate for operationlising the public health services as detailed above including raining for managerial roles, a public health perspective and rational

therapeutics. Training of field workers need to be strengthened.

Recommendations for Health Services in Himachal Pradesh

•

•

•

Rationalization of staff

Filing up of all vacant posts

Contract system be abolished

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Free diagnostic tests and no user charges

Each PHC should have a lady doctor

Per Diem system for different trainings be removed.

Incentive for trained birth attendant for promoting safe deliveries

Basic facilities at sub centre level be ensured

Separate and independent IEC Bureau be established with trained staff in health

education.

Work load of Anganwari workers should be decreased.

Recommendations for Health Services in Uttar Pradesh

•

Establish, adopt, recognize health as a fundamental right of all citizens including

vulnerable, displaces, slum dwellers and poor.

• The Primary Health care system should be made accountable to Panchayats in

rural and urban areas including JSA.

• Privatization or commercialization of health should be totally banned and

regulated by the state.

• Poor, marginalized, deprived, migrant and other vulnerable groups should be

accorded identity, accessibility and availability of health care system free of cost.

• Indian system of Medicines should be treated at par with modern medicines and

should be mainstreamed.

• Social security to senior citizens, children, disabled and women should be

specially provided.

• All the policies related to health, child development and women empowerment

should be seen in totality and not in isolation.

• All forms of user charges should be removed and health care should be provided

free of cost.

• The denial of health care and negligent care should be made accountable to

people and arrangement of redressed should be in place.

• The essential drug list should be made public and state should ensure the

reasonably quality and adequate essential drugs to all health facilities.

• The incentive and disincentive in family planning programme should be removed.

• Two child norm and coercive population policies should be removed.

• Government should honour the “Health for all goals and adopt the PHA charter

EASTERN REGION PUBLIC HEARING

ON RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

RANCHI

11 OCTOBER , 2004

Recommendations:

The public hearing on the denial of right to health care that was held in Ranchi on the 11th

of October, heard a number of cases of denial from the five states of Bihar, Jharkhand,

Chhattisgarh, Orissa and West Bengal.

Of the over 70 cases presented orally and about 150 cases submitted in writing, there

were a few recurrent themes.These included

a. High degrees of illegal fees and denial of treatment if these are not paid - in

public health facilities.

b. Poor quality of service in many public health facilities.

c. Absence of any services in remote tribal areas.

d. Denial of right to safe drinking water.

e. Lack of food security and malnutrition related illness.

f. Expensive, irrational drug prescription along with lack of availability of essential

drugs in public health facilities.

g- Lack of emergency obstetric care services and safe abortion services

h. Lack of emergency services for a wide variety of emergencies - notably

accidents, burns, snakebites.

i.

Lack of referral transport system to access emergency services.

J- Poor access to sterilisation services and poor quality of sterilisation services.

k. Weak public health response to epidemics and sudden increase in infectious

deaths in certain areas.

After listening to the testimonies the panel has decided to take cognisance of only a

small part of them as individual human rights cases . Though the other individual cases

are also heart-rending the panel thought it more useful to pursue the systemic causes

behind these failures. For these systemic issues that underlie the denial of the right to

health care the panel makes the following 15 recommendations which are forwarded to

the state governments for implementation.

A Vigilance Mechanism must be build up in each state health department with

assistance and in coordination with the police department. This vigilance should

be proactive and not only responding to complaints. Its focus should be to prevent

Hegal charges in public health facilities, and private practice inside public health

facilities or in public hours.

2. All public health facilities should have display boards that state what are the legal

user fees if any , declare that payments other than these are illegal and inform

where to register a complaint in this regard.

1.

1

3. Vigilance also needs to be exercised against unnecessary referrals to nursing

homes, clinics, diagnostic services. To be effective on this the state governments

have to issue orders disallowing public health staff from referring to nursing

homes, clinics or diagnostic services where they have a monetary advantage or

commission..

4. Monitoring structures for health programmes should be established/strengthened

at the district and block levels with the inclusion of panchayat representatives and

civil society partners who are active in advocacy work.

5. Monitoring structures for CHCs, civil hospitals and district hospitals should be

established by either strengthening existing patient welfare societies or creating

them. These would also have vigilance functions.

6. Independent of the above two there should be a grievance redressal mechanism

where those who have been denied quality care- in the private or public sector

can go to for registering their grievance and seeking relief.

7. All areas which have had no doctor for over an year and all those areas which

have had no nurse/midwife for over an year should be publicly notified as

medically and paramedically underserved and a special package of measures must

be undertaken to provide some temporary relief and access to care for these areas.

( eg visiting doctor- pvt or public, mobile clinic. NGO, etc). This special package

adopted may be made in consultation with all interested parties especially the

States^should have a transparent non-discriminatory transfer policy such that

8.

doctors and other paramedical staff serve by rotation in difficult areas. During

such service in difficult areas a special package of measures including financial

incentives to support such doctors should be adopted. These two steps are critical

to address the problem of lack of doctors in difficult rural areas.

States should have a state drug policy and /or adopt a state drug action p

9. which ensures that the states formulate an essential drug list and all the drugs o

this list are available at all public health facilities without interruption, and that

the prescription and use of irrational, expensive drugs and the use of hazardous

and banned drugs is curbed in both the private and public sector. This would also

need to specify better drug information to both the patient and the prescribers.

10 The state should adopt a time bound action plan/road map by which e: cn ica

gaps in the provision of good quality emergency obstetric services,sterilisation

services, safe abortion services, and basic surgical emergency servicesf burns ,

accidents) can be provided in a network of referral centers such that there: is at

least one such center per eveiy 100000 population. This action plan should be a

detailed publicly stated commitment and should have an year by year milestone,

so that even if the entire plan would take ten years to implement, the monitoring

committees and the public would know whether each year, that year s goals are

being achieved.

11. The most immediate measure for closing specialist gaps in the referral center

would be transferring of surgeons and gynaecologists and anaesthetists so that this

norm for the provision of emergency and referral level care is met in as many

facilities as possible. In the absence of a transfer policy well-qualified specialists

2

languish in peripheral centers losing their skills while key facilities, which needs

their services, go without them.

12. The governments may publicly notify what are the services it would be providing

at the level of the habitation, at the level of subcenters,at the level of PHCs, CHCs

and district hospitals along with quality indicators. This should be accompanied

by similarly graded standard treatment protocols. This is essential for public

knowledge and for monitoring. This will also help prevent unreasonable

expectations from the public - for certain services may be available only at the

district or block level and not at every PHC as may be expected. But this needs to

be publicly notified.

13. The governments should set up a medical services regulatory authority- analogous

to the telecom regulatory authority- which sanctions what constitutes ethical

practice and sets and monitors quality standards and prices of services - both in

the public and even more importantly in the private sector.

14. A Public Health and Health Services Act that defines the rights of food security,

safe drinking water, and other determinants of health and the citizens’ rights to

enjoy them along with the rights to medical services that are accessible, safe,

affordable needs to worked out. This act would make mandatory many of the

recommendations laid down above and would make more justiciable the denial of

health care arising from systemic failures as had been witnessed during the public

hearing.

15. Implementation of the Supreme Court order regarding food security and the need

to universalise ICDS programmes and mid day school meal programmes remains

a priority that this panel also endorses.

3

RECOMMENDATIONS OF

NORTH EAST REGIONAL PUBLIC HEARING ON

RIGHT HEALTH CARE

GUWAHATI

DATE: 28th NOV 2004

Budgetary Measures:

1. The state Health budget on Health budget on health care to be doubled with

immediate effect.

2. The drug budget for PHC and CHC in the state should be doubled.

3. In the pre monsoon season, extra stocks and inventory of all essential medicines

to be made available in government hospitals in rural areas to deal with possible

disruption in supply.

4. Contingency plan to deal with healthcare arising during and post flood situation

in the state with special staff assigned for such work.

Legal Measures:

1. Enactment of a State Public Health Act in each state, which would outline the

mandatory health care services which might be made available to the people as a

right at various levels of the public health system. This act would specify which

services and standards of care must be made available at the community, sub

centre. PHC, CHC, Sub-district and District hospital levels, as well as the

preventive and promotive measures that the government would undertake.

2. Enactment of a Clinical Establishment Regulation Act in each state to ensure

minimum standards, adherence to standard treatment guidelines and ceilings for

costs of essential medical services in the private sector.

3.

Private practice presently allowed to Government health care providers should be

legally banned, and those doing it should be promptly punished.

4. Policy for primary health care in the state should be adopted and implemented.

1

5. Standard Treatment Protocol for treating of all common ailments should be

prepared and enforced.

6. The clear and distinct regulatory act for private nursing homes should be made.

7. Public hearing should be organized on a regular basis in all the North Eastern

State in every district of Assam.

8. Private practitioners should have a uniform and affordable rate to make medical

treatment accessible to all.

Measures to improve functioning of the health system and attention to

special groups:

1. Standard Treatment Protocols should be implemented regarding care to be

provided at various levels of Health Care Facilities, so that the necessary quality

is maintained.

2. The full range of comprehensive health services should be guaranteed at all

levels of the public health system, these health services must be ensured as a

right. In exceptional cases of failure by the public system to provide any such

health service to a patient, there should be a mechanism wherein care may be

sought from designated private facilities following standard treatment protocols.

Such registered and regulated facilities could give relevant care to the patient,

and the state could reimburse them at standard rates, ensuring that the patient is

not deprived of any essential care at time of need.

3. Guaranteed availability of essential drugs relevant to the level of service, in all

public health facilities. A mechanism to ensure that if any health care facility is

unable to provide any of the essential drugs that are supposed to be available at

that level of health care; the expenses incurred by a patient on this “outside

prescription” should be promptly reimbursed. All health care providers in both

public and private sector should prescribe according to the essential drug list,

and prescribe drugs by their generic names.

4. A comprehensive statewide policy to provide Primary Health Services to urban

areas. Adequate health services need to be provided in al cities and small towns.

2

Expansion of urban health care infrastructure especially of health posts and of

outreach health services keeping in mind the needs of the growing slum

population.

5.

Filling up of vacant posts and construction of buildings for Sub centres and

other facilities. A new scheme to provide a community Health Worker in every

village of the state should be launched.

6. Regarding women’s access to health care, availability of all services in a women

friendly and sensitive manner at public health facilities must be ensured. This

should include maternity services, pre natal and neonatal care etc.

7. A scheme for community Health Worker in every village should be launched.

8. Urban Health care infrastructure should be expanded and PHC services should

be made available in all towns and cities. Emphasis should be given to slum

dwellers.

9. Malaria is a major problem in the state. Special action plan to deal with malaria

in the north east states with emphasis on vector control and ecological measure

along with universal availability of anti malarial drugs.

Independent Social Monitoring and Redressal System

1. Apart from the above steps, a system of regular independent monitoring of the

functioning of the heath care system at all levels should be taken up.

2. An effective redressal mechanism at block, district and state levels for persons

with complaints regarding quality of health care and for those who have suffered

denial of health care in any form.

3

> Enactment of a State Public Health Act in each state, which would outline the

mandatory health care services which must be made available to the people as a

right at various levels of the public health system. This act would specify which

services and standards of care must be made available at the community, sub

centre, PHC, CHC, Sub- district and District hospital levels.

> Enactment of d Clinical Establishments Regulation Act in each state to ensure

minimum standards, adherence to standard treatment guidelines and ceilings for

costs of essential medical services in the private sector. For example, the Bombay

Nursing Home Regulation Act 1949-Maharastra, may be substantially modified

and improved to effectively regulate the quality of private medical services in the

state.

>

The clear and distinct regulatory act for private nursing homes should be made.

> Public hearing should be organized on a regular basis in all the North Eastern

States and in every district of Assam.

> Private practitioners should have a uniform and affordable rate to make medical

treatment accessible to all.

4

The Urban Health Services in India: Towards Prevention of Human Rights

Violations

[Submission at the National Human Rights Commission Hearing,

National Level, New Delhi, 16th December, 2004]

An Overview

The focus of public health services planning and development in post

Independence India has been,

rightly, the rural populations. The urban

population even today constitutes less than 30% of India’s people and the urban

health indices show a better profile than the rural. Yet several large and small

studies have demonstrated the inadequacy of our State and society in providing

basic and comprehensive health services, so essential for the Right to Life, to

this relatively privileged population. All regional hearings organised by the JSA

and NHRC on the Right to Health Care have provided evidence of violation of the

right in urban people. While each state and region has its own special features, a

national overview and some common issues are being highlighted.

•

Urban areas constitute a wide diversity by size of population and land

area, condition of amenities and health care services. (Tables in

annexure).

Water,

sanitation,

housing

and

other

environmental

dimensions become greater problems as concentration of people on land

increases.

•

Disparity of economic and social status is more marked in the urban areas

as compared to the rural. 40-60% of all urban citizens live in the slums or

unauthorised colonies with poor socio-economic status, poor housing and

low standards of amenities. The health status indices of the different

sections demonstrate a direct correlation between socio-economic status,

the health of the poor even showing worse figures than the rural in some

instances.

•

On the other hand, the urban areas have the highest concentration of

health services, both public and private.

•

Public services in urban areas are relatively low at the primary level,

especially in' terms of community outreach. The secondary and tertiary

services are more highly developed; all secondary and tertiary institutions

are situated in urban areas. Private services are high at all three levels.

The secondary and tertiary hospitals serve both the urban and the rural

people.

•

The lack of focus on the planned development of a ‘comprehensive health

service system’ in urban areas has been officially recognised atleast since

the 1980s, with the Krishnan Committee report of the central government.

•

Major lacunae that clearly exist today are the following:-

•)

Lack of access to services by the poor.

")

Physical mal-distribution of services and mal-distribution of resources

within the health services. The lack of peripheral services, multiple

authorities providing services and overlapping responsibility of the

institutions and agencies, as exemplified by Delhi’s health services,

leads to overcrowded hospital OPDs and wards. While rationalising of

existing infrastructure has been repeatedly recommended, no action

has been taken in this direction.

iii)

Major weaknesses in functional quality of the public services exist

because of the load on them, with a user profile that has lower

resources to supplement the services provided than the private sector

users. Nevertheless these cannot be reasons to excuse the kind of

violation of rights of the citizens and of the patients coming to the

institutions. Evidence of gross misinformation, negligence, poor social

interaction by doctors abounds. The rude, aggressive behaviour of

paramedics and other staff of health institutions with those who come

to these institutions in times of crisis for some solace can only be

called criminal.

iv)

While our focus is the provision of services by the public sector, impact

of the private sector on the pubic services needs to be recognised. The

private sector issues largely pertain to services in urban areas where T

they too tend to concentrate. The issue of free land to private

corporates without their fulfilling the obligations in the contract are

issues of urban governance. Public funds being siphoned to support

the private sector through the social insurance (CGHS, ESI etc.),

instead of going to strengthening of public services, are issues of

concern. The private services also set up models of engage in greater

practice of over-medication and prescribing of unnecessary medical

interventions which, besides adding to costs also bring in iatrogenic

diseases due to the side-effects etc., which adds to the burden on the

public health services

The Presentations in the Session

1. Mr S.J.Chancier, Community Health Cell, Bangalore, presents conditions

from the Southern region, focusing on the issues of barriers to access to

services of the urban poor.

2. Dr. C. Sathyamala, Epidemiologist, presents data from a recent study that

highlights the impact of economic conditions, and that the poor still rely upon the

public services despite the problems they face.

3. Dr. Kamla Ganesh, Retd Professor of Obs. & Gynae, and ex-MCH adviser to

the Delhi govt., presenting findings of her excellent investigation into the

reasons for maternal deaths of women coming to the IPP-VIII MCH centres for

ANC/delivery. Basically highlights the institutional flaws and the need for support

to health care personnel in performing their duties.

4. Dr. Sanjay Nagral’s presentation on the Mumbai and Maharashtra situation

and the impact of public private linkages in terms of access and the quality of

services.

5. Dr. Rajib Dasgupta, Centre of Social Medicine & Community Health, JNU,

presents the recommendations.

Recommendations for Preventing Human Rights Violations by the Urban

Health Services in India

1. Rationalising the struc ture of health services

•

Almost all large urban centres suffer from the problem of multiplicity of health

service delivery agencies. The respective roles of state government and local

bodies as health service oroviders in urban areas need to be clearly defined.

Should local bodies be confined to primary health care services only? The

general trend is that local bodies are resource-constrained and therefore the

‘burden’ of secondary and tertiary health care institutions are borne by the

state governments. Secondary and tertiary care institutions are/will almost as

a rule be located in urban centres and also act as referral units for the

general/district health services. That argument will de facto imply that urban

local bodies confine themselves to the primary level only. Though the

Bombay Municipal Corporation operates services at all level including medical

colleges that is an exception than a rule as the financial health of the

organisation supports such endeavours.

•

Recommendations of Committees appointed so far - Krishnan Committee,

Pattanayak Committee- to rationalise and integrate existing public health

agencies need to be adopted

and

implemented. The Pattanayak

Committee was appointed in the aftermath of the Dengue Epidemic in

Delhi to restructure the services of Municipal Corporation of Delhi. It

essentially recommended reorganisation of the services on the basis of

municipal wards and suggested changes for personnel and services to

that effect. It also recommended strengthening of certain key

public

health institutions like Infectious Diseases Hospitals. Epidemiology Units

and Public Health Laboratories for epidemic forecasting and better

management of outbreaks, particularly of infectious diseases.

•

Public health programmes operate vertically in most urban areas. Though

Ward Health Units exist in some cities/towns, rarely do they deliver

integrated comprehensive services. What is delivered is (as is common in

the rural system also) selective primary health care or programmes in

campaign/mission mode like Pulse Polio. There is a need to integrate and

rationalise the manpower and services.

Prevention programmes need to address all sections rather than target only

•

the poor. Urban local bodies, and their personnel, are oriented largely

towards slum populations. However, public health cannot be bought ‘off the

shelf and urban local bodies will have to address all sections of the

population more comprehensively rather than adopting a sectoral approach. It

means that non-slum areas get ignored this is reflected in various house-tohouse campaigns. Vector breeding is actually often higher in better-off

households that have more containers.

•

Support services like blood banks, ambulance services and hearse van

services should be networked with all level of institutions for efficient

functioning and reduction of response time.

2. Strengthening of Primary Level Institutions :

•

Peripheral areas of towns and cities (generally populated by poorest

segments) often lack institutional coverage; these areas require special

attention and institutional coverage should be expanded.

•

All health posts should provide outreach services to slum and slum like

areas through ANM and MPW.

•

Monitoring primary health services should be included as a responsibility

of the Ward committees.

•

New guidelines on the role and functioning of the health post system in

view of an integrated and decentralised primary health care programme

need to be developed and implemented uniformly across all the Municipal

bodies in the state.

•

Equipment and infrastructure backup should be available in dispensaries.

•

Vacant posts of personnel should be filled up, their allocation rationalised and

regular attendance and performance monitored and support provided against

the inherent medical and legal hazards of the occupation.

•

Maternal and Child Health Centres / Family Welfare Centres should provide

full range of primary gynaecologic, obstetric and paediatric services; special

emphasis needs to be given to emergency services and institutional deliveries

whenever indicated.

•

There is a need to train and integrate dais who operate in lower income

groups of urban areas with the formal primary health care system.

•

Public health programmes and personnel need to be reorganised/restructured

and these institutions need to integrate with the local curative institutions.

•

Communities (through Local Health Committees, for example) should be

involved in local level planning and implementation of services; the

departments of health, water, sanitation, education and social welfare should

be involved and accountable to these local committees.

•

The experience of contracting of service delivery to private agencies and

NGOs, e g. School Health Services, immunisation services, IEC field

campaigns

and

cremation

ground

services

should

be

reviewed;

comprehensiveness of services, coverage, follow-up, cost-effectiveness and

sustainability should be some of the criteria on which the ‘new’ services are to

be evaluated.

•

Birth and death registration procedures should be made transparent and

citizen friendly.

3. Strengthening of Secondary and Tertiary Level Institutions

•

Primary and secondary level services need to be available and accessible to

prevent overload of tertiary hospitals, that is almost a rule across urban

centres of India. These institutions should be linked with the local primary

level institutions with a proper referral mechanism.

•

Secondary level speciality services and requisite equipment and supplies

should be available.

•

Rational prescribing practices should be implemented. Experience of Delhi

and other cities where efforts have been made in this direction should be

reviewed and lessons drawn.

•

Adequate supply of drugs and other consumables, particularly, live saving

drugs and equipment must be ensured. The purchase procedures should be

transparent. The model of Tamil Nadu Medical Supplies Corporation can be

adopted.

•

Special emphasis needs to be given on environmental and occupational

health problems.

•

Social security services like Central Government Health Services (CGHS)

and Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) and other employee

medical benefits in public institutions should not refer patients to the private

corporate hospitals and instead should integrate and network with secondary

and tertiary level public institutions. This will allow public funds to be used for

strengthening of public services rather than be siphoned off to private

services. It will also build pressure for the strengthening of public institutions.

4. Institutional Structures and Procedures for Constant Monitoring and

Strengthening

•

Clinical auditing of deaths of patients can go a long way in making the

services sensitive to their own weaknesses in patient management

practices. This should be made mandatory and brought back as a live

practice so as to improve medical care and prevent negligence.

Grievance redressal mechanisms must be available within each institution

and for public health services as a whole. Measures for informing users of

the services about the mechanisms must be a responsibility of the

institution and the health services.

Social audit mechanisms must be instituted to make the services

responsive to community needs.

Co-ordinator. Dr. Ritu Priya, Centre of Social Medicine & Community Health,

JNU.

Health of the urban poor in Karnataka

Areas of concerns

By S.J.Chander

Community Heath Cell

Introduction

AT least 22 per cent of Karnataka's urban population lives in insecure and unhygienic urban

slums. In September 1999, the Karnataka Slum Clearance Board (KSCB) identified 2,322

slums in the State with a population of around 23.79 lakhs, which is 17 per cent of the total

urban population. Bangalore alone accounted for 362 slums with a population of 5.9 lakhs.

This appears to be an underestimate of the actual figures.

In 1993 itself the National Sample Survey, 49th round estimated the slum population was at

32.2 lakhs, making it around 23 per cent of the total urban population in the State. The same

study estimated the population of Bangalore's slums at 10 lakhs1. Bangalore

experienced an exponential growth of slums in the 1990s, from 444 slums in 1991 with a

population of 1.12 million, to 763 slums with 2.2 million in 1998-99 with a population of,

about 20 per cent of the city's population. The most recent data, from the 2001 Census, lists

733 slums in Bangalore. (The Hindu, June 3, 2003)

The present health care services made available for the urban poor are family welfare and

family planning oriented. The word Primary Health Care has been used inappropriately by

many agencies including the government and voluntary organization. Their understanding is

no way close to the definition for Primary Health Care that the World Health Organization

(WHO) gave during the Alma Ata declaration in 1978.

It is presumed that urban poor do not lack health care facilities, as most of the health care

facilities are concentrated in the urban areas. This may be true but the question for which one

must find an answer is to what extent these facilities are really accessible, available and

affordable to urban poor. The present model excludes the important elements such as water

and sanitation, Health education in the Primary Health Care Approach that the WHO

advocates. Treatment of minor ailment is also inadequate and unsatisfactory which is one of

the eight elements of Primary Health Care specified by WHO. Recent interaction with some

of the community members revealed that some of the urban health centers do not have anti

rabies vaccines and treatment for tuberculosis. The health problems faced by the urban poor

are largely due substandard living conditions and lack of health awareness. Alcoholism and

Tobacco are another major problems, which takes away limited economic resources available

for the families. The problem of alcoholism not only takes away the resources, it constantly

causes psychosocial problems in the families. Unless these issues are addressed satisfactorily

improvement in the health status of the poor cannot be achieved.

1 Karnataka Housing Revolution, Parvathi Menon in Frontline Magazine. Vol 19, Issue 13 June - July 5,2003

1

Substance abuse, exploitation by unqualified providers (quacks), and use of hazardous

biomass fuels for cooking have direct health consequences that are often overlooked.

Alcoholism

Alcoholism is another major problem that puts pressure on the limited income of

the urban poor. The survival of the alcohol industry to a large extent depends on the poor.

The major portion of the income that the man earns goes in for alcohol, depriving the families

the money for nutritious food and educational needs. One of the serious consequences of

alcoholisms is violence, particularly against women. Do we need more studies to confirm to

get into action?

Water and sanitation

The urban poor not only suffer from inadequate water supply and sanitation, they also suffer

from poor quality of services that area available to them. One fifth of all urban households

lack access to water supply and 60 percent of urban households live without access to

sanitation. In slums, 40 percent of households are without access to safe drinking water, and

90 percent without access to sanitation. Per capita daily consumption of water in Class I cities

is less than 142 litres, reaching a low of 50 litres in some cities.3

Recently, Jansahyog a (Bangalore based voluntary organization) collected water samples