ASF SEMINAR RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

Item

- Title

- ASF SEMINAR RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

- extracted text

-

RF_L_3_A_SUDHA

j) Pedal' c. [4ecJjM-> Q^-f^

Sy£t<om'. T)m-eaj€y‘

_ c

e>p^lcmS

, A

i) Ccnornuu^'ccJn’ooo -

PEOPLE

- De vi^el UJe*<«oe/7

i) Meobaa.^A

/4o5lJJ^ Cq

,4^Aj^O

Asv

V

I4o=uAPm «vo

q.

^-ej'r&naj

/7-tl

/W

Gn

Cbr)£uJU-CLhcyn

hjs - 16-1/ /^jjr 2c>c>l, N H R. C .

~r^a-^

Wo v <

— Prbkcccj

z) A- (bncx^^ pcx-p<4

i-wu4>

r2

on

Pessf

/;

h

/f

I© "T,eetdn

IQ<cc>m l-fc

^)Tke

QrcM- /Probe© '‘

mQrv,

Icctlbej-^,

PeoJtST- lx) fc^jcJq.GL

^nSfc P^cm& A

»5

oil o c.q nnerch

Gvig^? —

t-g> kxLGuU^t Ccire Q<?

CU7

k>

- Hnenkd

BqcJt_£>TrGU)nc3/

b>

l4e4aJjb> G^v-e

JTC, (

rPe-d/ Ccj tas’uranQ-

LJ 0 wi’G^n^c

^CCe^si

—’

C&jY'e • P horyji'ov.

CaTf*

RFMH-fl fs

v

U^Y-e^cAseJ, Pr. /)vo(g .

CEU'npctJdr)

^5

o

*4^ve. l^-cojj-h

PI q h nJ

1^)

h

pnrim^ryy

— Dy.

*9 PeopJk

S’. 0u& Qfpqrcr^l

_pv,

Co Im muirJ

ip Ui<^e^xcJ

i' olc-a.

Atccz^ /» kedK)

y n

CK-|O p'Y OQC^)

(Irovry

SKxMi.

|4<-cjLH>»

UAJve^scJI

lo)

PcJadc l~^ru(y^>

<3 n

|^e_£U_^) Gcir^

'fe»

So^dLc VS.

f-btmah Pi'gtd' - A-cw Cha<+€/7,

l-Mmoun

Pt.

£ e^alb^. oJ

j>a^<-o|

—

KY>cdd-C^ xJ

|e>

— SqrhQ

C^pnopCciof)

l4e_cvLM _

’X

JRb' h> rtenW

ftincU**-.

3

Or^

UJorvie^'t

UJowierj'x

1

tjl^beJ Nefuftvt

■

1^* ^s.

«- Hehah-C„bt lUc.Jv.Vo'mH

Ife) G-S’ha.hJb’S hfn

q

vecJlis h’c-

$ Pepo 'fb

•ao) Repc*'

oy>

C Rt-

3

qpp/Stata

Batik of -My^ge -crn#/

Vz> HeoJU-h Ca-re' SerninQ*-Osp

rR.t

LjculcB

GY)

tleaJjH)

iQ Rl.

^checL-Uj)

O^V-CxI^qI

P*-e^en kk>1^« 1

l\ n-v*-^

lY)eeJ'z

G^Ye- — G»nnpc^,^n

c*>

- p <e>oe

+t> Ut-cJU-h Cq-r-e’ — Is !(_

T-

—

NoJicxnoj

A-C'cCx^

J)i< fir)

CenoJ uJln

5,

Py . Ro X/ i »

C© n $

o-o

Ptvj} 03

Joseph cA

0/Gv. Ay£ I© WojAh

T

2

co

%

5

S

•n

i

2

E

is

£

8

§

B

s

5

0100027

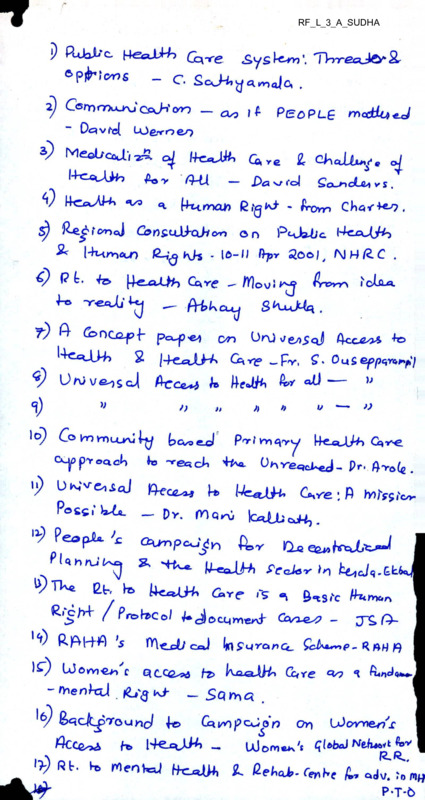

Public Health Care System: Threats and Options

(Concept paper for the mfc annual meet, 2003, draft)

C Sathyamala

The theme for the next Annual Meet, “Public Health Care System: Threats and Options”, is

being proposed at a time when the health care system in India is undergoing a radical

transformation. The massive expansion of the private medical sector, entry7 of private

insurance in medical care, introduction of payment (“user fees”1^1) for medical services in the

government sector are just three such changes we have witnessed in the last decade. The

rapidity with which these changes are taking place leads one to view such developments with

great trepidation. It could well be that in a matter of few years we will have installed the

American model of high-cost, profit-driven, technology intensive, unjust, inequitable health

care system in our country7. This view may perhaps be dismissed as being unnecessarily

alarmist, but there is certainly a general concern that soon health care is going to be out of the

reach of ordinary people.

The growing sense of disquiet many of us are experiencing is beginning to be voiced in

public fora with, surprisingly, the government and its agencies too joining in at the chorus. As

a sign of good "governance”2121, a dual system (one for the rich and one for the poor) is being

proposed to tackle the issue of equity in health care without in any w ay disturbing or altering

the process of disinvestment that has been set into motion. A high-technology based medical

service on par with what is available internationally elsewhere, is to be provided by the

private sector for the small section of the population that can easily meet the costs (and for

the purposes of earning foreign exchange) and a "minimum clinical package courtesy

World Bank (1993)3[31 provided by the government to be availed of by the poor if and when

they can mobilize sufficient resources to meet the direct service charges and the indirect costs

(transport, loss of wages) such care entails.

Concern not withstanding, among the critics there appears to be a tacit acceptance of the

nature of things to come and a tacit agreement as to the near impossibility of stopping or

reversing the relentless march of market forces. Depending upon one's current world view

and analysis, suggestions for ‘improving' the government's national health policy aim at

creating a space for the poor within the framework laid down by the state under the aegis of

the World Bank and Transnational Capital, without challenging the very frame work itself.

While at one level such a strategy7 may be taken to reflect a pragmatism of sorts, increasingly

it is being upheld as the most, and often the only viable alternatives under the given

circumstances. Could this be due to the near absence of a genuine pro-people movement in

the country to articulate the needs and aspirations of the marginalized from their perspective?

Is a different perspective possible? Are there other options which will place people’s need

centre-stage? How should mfc contribute to the development of such a perspective and help

evolve strategies that can translate into concrete demands difficult to coopt and make health

care a justiciable right for all? This should form the focus of the mfc annual meet.

UH why user £^9 The word Tee’ means, a payment made to a professional person or to a professional or

public body in exchange for advice or services (concise Oxford Dictionary, 10th ed). Is the addition of "user’ in

order to camouflage the nature of privatisation of public services?

2l2' There is an entire chapter in one of Susan George’s book (will supply details later) which discusses when

and why the archaic word ‘governance’ was brought back into general usage by the World Bank.

3131 “Investing in Health Care”, World Bank, 1993

It is not sufficient to say that public health is under attack or that the public health care

system is being dismantled. There is need to spell out what exactly is being attacked and what

exactly is being dismantled. And most importantly, how exactly it is going to affect the health

of the poor because, the poor view with indifference (and once-in-a-way, with anger), what

currently exists in the name of public health services. When present, broken down and

vandalized buildings of sub-centres/PHCs in the villages and taluk towns; every cadre of

health personnel from the level of the inadequately trained village health worker to the doctor

at the district head quarters out to exploit their ignorance and capitalize on their misery and

helplessness; corruption from the top to the bottom of the ladder; anti-poor, casteist, sexist

(and in the last decade, communal) attitude of the individual medical personnel especially the

doctors, the 'leaders’ of the medical team; non-availability of medicines/equipment and poor

service in public hospitals, particularly at the district levels; anti-poor, anti-women

aggressions carried out by the department of population control - the poor have borne mute

testimony to what government health services mean at the ground level and are not going to

be impressed very much if they are to be informed that such 'services' are going to be

disbanded.

In any case today even from among the poorer sections of the population, the trend is to

'seek' medical care from the private sector when possible. It is only when there are no

options as in times of serious illnesses when the cost of care is too great, that the compulsion

to utilize government health services arise (which increasingly is turning to be no option at all

w ith the introduction of service charges in the public sector). The irony is that the observation

- people, poor people are spending money on medical care is being seen as a statement of

their '‘willingness" to pay for treatment costs. While this may be more a reflection of an

absence of other options than an exercise of real choice, studies on household expenditure on

health have seldom asked two additional critical questions, how was the money for payment

mobilized in the first place and what was the impact on the household economy as a

consequence of this4'41. Thus, while studies abound on household expenditure on medical

care, equal attention has not been paid to assess, for instance, rural indebtedness due to

disease and treatment costs. How ever one explains the whys of this lacuna, this 'short

sightedness' has worked against the interests of the poor. Studies such as these have

legitimized the notion of payment for ‘services’ and have cleared the way for introducing

"user fees" in public health services. Even here, contrary to the proclaimed objectives, the

introduction of fees is not to generate funds for the resource-poor public sector. The intention

is to wean away from the public sector to the private, that section of the population that is

currently using it but has any surplus at all to spend (if money has to be paid in either case,

why settle for what appears to be ‘second best'?5151). The intractable truth is that with its one

and only goal of‘maximizing profits’ at any cost, the private sector (and monopoly capital)

cannot tolerate any form of competition whatsoever.

We need to understand the move to phase out the state-owned secondary and tertiary’ referral

services in this context as a logical step for removing a major hurdle in the path towards

unfettered private monopoly in curative clinical services. Plans are also afoot to convert the

role of the government from a provider of even basic health services into a mere financier

who will, on behalf of the poor, ‘purchase’ the necessary services from the private sector.

This with an avowed intention of improving quality of care by encouraging competition

4t41 The other important questions are the proportion arid rate of illnesses for which medical care is not sought;

nature of such illnesses; gender, class, caste differentials etc.

5151 In many parts of the country, government hospitals are called dharm or charity hospitals because they did

not charge money

among the private providers, apparently the most effective way of achieving the stated

objective. In reality it could very well be yet another ruse to provide more government

subsidy to the already state-subsidized private sector.

We are situated in a time in history when India has seen more than fifty years of

Independence from direct colonial rule. We are also situated in a time in history when India

has become a seemingly willing subject to the neo-colonial rule under the conditionalities of

the Structural Adjustment Programme. In this period of fifty-five years, an entire generation

of the poor has taken birth and died without having had even the ‘luxury’ of two full meals

every day for the entirety of their life time. In stark contrast to their lives, they have witnessed

the fruits of development built on their labour being reserved for the comfort and enjoyment

of a small section of the population - the upper class and the upper caste. Today, it is no

accident that this very same small section is bartering away the country’s sovereignty’ and

future to buy a place for themselves amongst the global ruling class.

Fifty7 years is a long time to have laid open the true intentions of our country's ruling elite

towards its people. It is not chance but choice that we have millions of people living a life of

chronic starvation when there is food rotting in the godowns. It is not chance but choice that

has created the necessary’ pre-conditions for the dictatorship of transnational capital.

To take an instance, it is not chance but choices made over fifty years that has created a

burgeoning private medical sector over-running the health care system in the country For,

how else does one explain the fact that a private sector which accounted for only 20% of the

health services in the early eighties, is now providing more than 80%? Where did the doctors

currently stocking the private sector come from? Are they not the products of our educational

sy stem and policies and for most part subsidized by the labor of the poor (through indirect

taxes)? Can a critique of medical education be unconnected to a critique of the educational

policy in general? Why are we shocked when we observe the mandalisation and

communalisation of the medical community in utter disregard to the Hippocratic oath? Is not

the dual policy that is being proposed today regarding medical manpower been the norm

rather than an exception since Independence? The training of licentiates in the period

immediately following Independence may have been in keeping with the needs and resource

availability in the country at that time. But choice was made to train a ‘full fledged doctor

matching international standards. Today when we have a surplus of doctors trained to fit

international norms, can we justify the renewed discussion on licentiate course to provide

‘sub-standard’ personnel to take care of the needs of the poor? When we have an optimum

doctor-population ratio6161 why are we opening more and more medical colleges? Why is the

World Bank (1993) which has arrogated to itself the right to set the terms for our country’s

health care system silent regarding the presence of surplus doctors in the country or the fact

that Indian doctors form a substantial portion of the medical community in several western

countries? Why is the national policy (2001 draft) silent on this? Colonial legacy cannot be

the only reason, we have had more than fifty years to over tum it.

The theme for the annual meet should therefore have a historical perspective running through

it. We should re-examine the economic/political considerations and compulsions, that have

shaped the national health policy since Independence and where necessary its links to the

colonial past and ‘heritage’. Only then will the analysis of the new health policy under

Structural Adjustment Programme make sense.

6[6] ■

incidentally, what is the rationale for deciding what is an optimum ratio.

The theme will be incomplete without a discussion on the contribution of non-governmental

organizations (ngo). Historically, the ngo sector, previously called the voluntary' sector, has

contributed in critical ways to the shaping of the national health policy and programmes.

Initially in the role of the service providers, the emphasis was on setting up hospitals,

particularly in rural areas and in training manpower of all levels. Over the years, many such

organizations enlarged their perspective of individual care to include ‘communities' and

experimented with alternate delivery systems by, for instance, training village health workers.

Campaigning for policy changes, highlighting disparities and equity issues, generating critical

data, more often than not from a pro-people (poor, women) perspective, are some of the other

important contributions. However, the last decade has seen the emergence of questionable

priorities largely determined by the agenda of the funders. There has also been a moving

away from working directly with people to Tobbying’ and ‘advocating’ with policy' makers

as the most effective means of bringing about change. Over a period of time, the potential for

supporting people's struggles is being slowly frittered away and the poor are beginning to

view such organizations with cynicism and distrust.

The fact that the disparate ngo sector contains within it a section of the liberal vocal middle

class with little social accountability and no explicit ideology or long-term commitment has

made it a sitting duck for cooption. The dependence on external funding, be it domestic or

foreign, has meant that it is possible to manipulate and pressurize at critical times and shift

their attention from issues of people's livelihood to seeking means to protecting their own.

It is this vulnerability and the accompanying vacillation that makes the ngo sector attractive

to the World Bank (itself an ngo?) and the state who wish to bring into their fold the

dangerous potential for dissent and give it a shape in their own image. A calculated political

act of blurring the lines by clubbing all organizations irrespective of their political leanings

(right, centre or left)7171 under one umbrella term “non-governmental organizations'" was the

first step towards containing dissent, an act which went largely unprotested. However, that it

is still possible to channelize the not inconsiderable energy of the sector into a coherent

political force against oppressive policies has been amply demonstrated by, for instance, the

campaign against hazardous contraceptives, SDSP tests. The move to form a people's Health

Assembly being another such attempt.

MFC is uniquely placed to examine the contribution of the ngo sector to the shaping of

national health policy. Many of its members have been in the forefront at critical junctures in

reaching health care to the poor and the marginalized both in the literal and figurative sense.

With the rich experience and wisdom gained over the past thirty' years of intervention,

experimentation and participating in the political process to influence health policies either at

an individual level or as an organization, the discussion could be very rewarding if we bring

to it our own personal experiences. The strengths of the mfc are its non-sectarian approach

and a potential to critically examine an issue without taking anything as a given. Can we turn

this ability of ours to examine dispassionately, our several attempts at creating an alternate

world view in health care, the successes and failures of our 'projects' and question our own

thinking with the luxury of hind sight?

This decade is going to bring about cataclysmic changes, particularly when the WTO treaty

comes into effect in 2005. The “reforms”81^ that are being ushered in the name of

globalization are already beginning to be experienced with rising unemployment,

retrenchment of workers, and a shift towards insecure, casual labour and poor wages. Added

to this is the impact of privatization of public health care services, rising drug prices and

costs of treatment. These changes are going to have an adverse impact on the health of the

poor and lead to a rise in morbidity and mortality rates in the vulnerable sections of the

population.

Si

SA

commtmacafaon

odoptinq heolth promotion ond sociol oction to the

qlobol imbolonces of the 21st centurq

by PSv/tJ Wome-r

Democracy^ a

prerequisite

for a M EALTHY

SOCIETY

Why participation is essential - and how it

is undermined

he well-being of an individual or commu

nity depends on many factors, local to

global. Above all, it depends on the oppor

tunity of all people to participate as equals in the

decisions that determine their well-being Unfor

tunately, history shows us that equality in collec

tive decision-making—that is to say participatory

democracy—is hard to achieve and sustain.

Despite the spawning of so-called democratic

governments’ in recent

decades, most people

still have little voice in

the policies and deci

sions that shape their

lives. Increasingly, the

rules governing the

fate of the Earth and its

inhabitants are made

by a powerful minority

who dictates the Global

Economy. Thus eco

nomic growth (for the

wealthy) has become

the yardstick of social

progress, or ‘develop

ment,* regardless of

the human and envi

ronmental costs.

And the costs are horrendous! The top-down

‘globalisation’ of policies and trade—through

which the select few profit enormously at the

expense of the many—is creating a widening gap

in wealth, health and quality of life, both between

countries and within them. A complex of world

wide crises—social, economic, ecological and

ethical—is contributing to ill-health and early

death for millions. Increasingly, giant banks and

corporations rule the world, putting the future

well-being and even survival of humanity at risk.

Driven more by hunger for private profit than for

public good—the massive production of consumer

goods far exceeds the basic needs of a healthy and

sustainable society. Indeed, its unregulated

growth compromises ecological balances and

imperils the capacity of the planet for renewal.

Yet in a world where unlimited production and

resultant waste have become a major health

hazard, there are more hungry children than ever

before. According to Worldwatch’s The State of the

World, 1999, the majority of humanity is now

malnourished, half from eating too little and half

from eating too much!

Mahatma Gandhi wisely observed: ‘There is

enough for everyone’s need but not for everyone's

greed.’ Sadly, greed has replaced need as the

driver of our global

spaceship. Despite all

the spiritual guidelines,

social philosophies,

and declarations of

human rights that

Homo sapiens (the

species that calls itself

wise) has evolved

through the ages, the

profiteering ethos of

the market system has

side-tracked our ideals

of compassion and

social justice. Human

ity is running a danger

ous course of increas

ing imbalance. To

further fill the coffers of the rich, our neoliberal

social agenda systematically neglects the basic

needs of the disadvantaged and is rapidly despoil

ing the planet’s ecosystems, which sustain the

intricate web of life.

The dangers—although played down by the mass

media—are colossal and well documented. For

ward-looking ecologists, biologist, and sociologists

sound the warning that our current unjust, unCtrrmjnicaticn as if People lettered

healthy model of economic development is both

humanly and environmentally unsustainable.

Yes, we know that,’ say many of us who believe

in Health for All and a sustainable future. ‘We are

deeply worried.... But what can we do?’

There are no easy answers. The forces shaping

global events are gigantic, and those who accept

them as inevitable so impervious to rational

dissent, that many of us hide our heads in the sand

like ostriches. And so humanity thunders head

long down the path of systemic breakdown—more

polarisation of society, more environmental

deterioration, more neglect of human rights and

needs, more social unrest and violence—as if our

leaders were incapable of thought and our

populations anaesthetised.

What action can we take, then—individually and

collectively—to change things for the better, for

the common good?

The purpose of this background paper

The interrelated crises of our times—the ways that

globalisation, corporate rule, and top-down,

development’ policies undermine democratic

process and endanger world health—are discussed

in other background papers for the People’s

Health Assembly. The purposes of this paper are:

1.

2.

to examine the strategies used by the world s

ruling class to keep the majority of humanity

disempowered and complacent in the face of

the crushing inequalities and hazards it

engenders;

to explore the methods and resources whereby

enough people can become sufficiently aware

and empowered to collectively transform our

current unfair social order into one that is

more equitable, compassionate, health-pro

moting, and sustainable.

TOP.B

o,W,N

MEA5L1KL5 of

SOCIAL CONTROL

Disinformation

With all the technology and sophisticated

1

J means of communication now available,

V

how is it that so many people appear so

unaware that powerful interest groups are under

mining democracy, concentrating power and

wealth, and exploiting both people and the envi

ronment in ways that put the well-being and even

survival of humanity at stake? How can a small

elite minority so successfully manipulate global

politics to its own advantage, and so callously

ignore the enormous human and environmental

costs? How can the engineers of the global

economy so effectively dismiss the emerging risk

of unprecedented social and ecological disaster?

In short, what are the weapons used by the ruling

class to achieve compliance, submission, and social

control of their captive population?

True, riot squads have been increased, prison

populations expanded, and military troops de

ployed to quell civil disobedience. But far more

than tear-gas and rubber bullets, disinformation

has become the modem means of social control

Thanks to the systematic filtering of news by the

mass media, many ‘educated’ people have little

knowledge of the injustices done to disadvantaged

people in the name of economic growth, or of the

resultant perils facing humanity. They are uncon

scious of the fact that the overarching problems

affecting their well-being—growing unemploy

ment, reduced public services, environmental

degradation, renewed diseases of poverty, bigger

budgets for weapons than for health care or

schools, more tax dollars spent to subsidize

wealthy corporations than to assist hungry chil

dren, rising rates of crime, violence, substance

abuse, homelessness, more suicides among teenag

ers—are rooted in the undemocratic concentration

of wealth and power. Despite their personal

hardships, unpaid bills, and falling wages, ordi

nary citizens are schooled to rejoice in the ‘success

ful economy’ (and spend more). They pledge

allegiance to their masters’ flag, praise God for

living in a ‘free world,’ and fail to see (or to admit)

the extent to which the world’s oligarchy (ruling

minority) is undermining democracy and endan

gering our common future. And our textbooks and

TVs keep us strategically misinformed.

-40

People's Health Assentoly

One dollar, one vote: private invest

ment in public elections

One way ‘government by the people’ is

undermined is through the purchase of

public elections by the highest bidders. In

many so-called democracies a growing

number of citizens (in some countries, the

majority) don’t even bother to vote. They

say it makes no difference. Politicians, once

elected, pay little heed to the people’s

wishes. The reason is that wealthy interest

groups have such a powerful political

lobby. Their big campaign donations (bribes?)

help politicians win votes—in exchange for politi

cal favours. The bigger the bribe, the more cam

paign propaganda on TV and mass media. Hence

more votes.

This institution of legal bribery makes it hard for

honest candidates (who put human need before

corporate greed) to get elected. Democratic elec

tions are based on one person, one vote. With the

deep pockets of big business corrupting elections,

results are based on one dollar, one vote. This

makes a mockery of the democratic process.

The erosion of participatory democracy by the

corporate lobby has far-reaching human and

environmental costs. Hence the biggest problems

facing humanity today—poverty, growing in

equality, and the unsustainable plundering of the

planet's ecosystems—continue unresolved.

Sufficient wisdom, scientific knowledge and

resources exist to overcome poverty, inequity,

hunger, global warming and the other crises facing

our planet today. But those with the necessary

wisdom and compassion seldom govern. They

rarely get elected because they refuse to sell their

souls to the company store. Winners of elections

tend to be wheelers and dealers who place short

term gains before the long-term well-being of all.

To correct this unhealthy situation, laws need to be

passed that stop lobbying by corporations and

wealthy interest groups. In some countries, citi

zens’ organisations are working hard to pass such

campaign reforms. But it is hard to get them past

legislators who pad their pockets with corporate

donations. Only when enough citizens become

fully aware of the issues at stake and demand a

public vote to oudaw large campaign donations,

will it be possible for them to elect officials who

place the common good before the interests of

powerful minorities.

But creating such public awareness is an uphill

struggle—precisely because of the power of the

corporate lobby and the deceptive messages of the

mass media. To make headway with campaign

READ AGAIN-With MORE

feeding -the passage

l about the heroes of

XThe revolution. >

reforms, institutionalised disinformation must be

exposed for what it is. To accomplish this, more

honest and empowering forms of education and

information sharing are needed.

Schooling for conformity, not change

It has been said that education is power. That is

why, in societies with a wide gap between the

haves and have-nots, too much education can be

dangerous Therefore, in such societies, schooling

provides less education than indoctrination,

training in obedience, and cultivation of conform

ity. In general, the more stratified the society, the

more authoritarian the schools.

Government schools tend to teach history and

civics in ways that glorify the wars and tyrannies

of those in power, whitewash institutionalised

transgressions, justify unfair laws, and protect the

property and possessions of the ruling class. Such

history is taught as gospel. And woe be to the

conscientious teacher who shares with students

people’s history’ of their corner of the earth.

Conventional schooling is a vehicle of

disinformation and social controL It dictates the

same top-down interpretations of history and

current events, as do the mass media. It white

washes official crimes and aggression. Its purpose

is to instill conformity and compliance, what

Noam Chomsky calls manufacturing consent.’

For example, although the United States has a long

history of land-grabbing, neocolonial aggression

and covert warfare against governments commit

ted to equity, most US citizens take pride in their

‘benevolent, peace-loving nation’. Many believe

they live in a democracy for the people and by the

people, with liberty and justice for all’—even

though millions of children in the US go hungry,

countless poor folks lack health care, prison

populations expand (mainly with destitute blacks),

and welfare cut-backs leave multitudes jobless,

homeless and destitute.

Cbmrunicaticn as if Eteple fettered

-^1

the controlling elite. But to survive they need

listener support.

,-M-UP approaches

gOTT^to communication

j -o see through the institutionalised

I

disinformation, and to mobilise people

Vx* in the quest for a healthier, more equita

ble society, we need alternative methods of

education and information-sharing that are

honest, participatory, and empowering. This

includes learning environments that bring people

together as equals to critically analyse their reality,

plan a strategy for change, and take effective

united action.

Fostering empowering learning methods is urgent

in today's shrinking world, where people’s quality

of life, even in remote communities, is increasingly

dictated by global policies beyond their control.

Alternative media and other means of

people-to-people communication

There have been a number of important initiatives

in the field of alternative media, communication,

and social action for change.

The alternative press. While struggling to stay

alive in recent years, the alternative press (maga

zines, flyers, bulletins, newsletters, progressive

comic books) has provided a more honest, peoplecentred perspective on local, national and global

events. Some of the more widely-circulating

alternative magazines in English (often with

translations into several other languages) include:

The New Internationalist

Z Magazine

Resurgence

The Nation

Third World Resurgence

Covert Action Quarterly

Multinational Monitor

Also, there are many newsletters and periodicals

published by different watchdog groups such as

the International Forum on Globalization, IBFAN,

BankWatch, the National Defense Monitor and

Health Action International, among others. It is

important that we subscribe to and read (and

encourage others to read) these progressive alter

native writings.

Alternative community radio and TV. The role

and potential of these is similar to that of the

alternative press. Stations that do not accept

advertising are less likely to belong to or sell out to

People's Lfealth Asserrbly

Internet Electronic mall and websites have

opened up a whole new sphere of rapid, direct

communication across borders and frontiers. The

Web is, of course, a two-edged sword. The Internet

is currently available to less than 2% of the world’s

people, mostly the more privileged. And Instant

electronic communications facilitate the global

transactions and control linkages of the ruling

class. But at the same time. E-mail and the WorldWide-Web provide a powerful tool for popular

organisations and activists around the globe to

communicate directly, to rally for a common cause

and to organise international solidarity for action.

The potential of such international action was first

demonstrated by the monumental worldwide

outcry, through which non-government organisa

tions (NGOs) and grassroots organisations halted

the passage of the Multilateral Agreement on

Investment (MAI). (The MAI was to have been a

secret treaty among industrialised countries,

giving even more power and control over Third

World Nations.) The primary vehicle of communi

cation for the protest against MAI was through the

Internet.

Mass gatherings for organised resistance against

globalised abuse of power. The turn of the Cen

tury was also a turning point in terms of people s

united resistance against global trade policies

harmful to people and the planet. The huge, wellorchestrated protest of the World Trade Organiza

tion (WTO) summit meeting in Seattle, Washing

ton (now celebrated worldwide as the Battle in

Seattle’) was indeed a breakthrough. It showed us

that when enough socially committed people

from diverse fields unite around a common

concert^ they can have an impact on global

policy making.

The agenda of the WTO summit in Seattle was to

further impose its pro-business, anti-people and

anti-environment trade policies. That agenda was

derailed by one of the largest, most diverse,

international protests in human history. Hundreds

of groups and tens of thousands of people repre

senting NGOs, environmental organisations,

human rights groups, labour unions, women’s

organisations, and many others joined to protest

and barricade the WTO assembly. Activists ar

rived from at least 60 countries. The presence of

so-many grassroots protesters gave courage to

many of the representatives of Third World

countries to oppose the WTO proposals which

would further favor affluent countries and corpo

rations at the expense of the less privileged. In the

end, the assembly fell apart, in part from internal

(^INDIRA 11 TOO THIN- WMX

disaccord. No additional policies were agreed

upon.

DOESH'T BET BNOU6H TO EAT.

^HER PARENTS

/that'* A «OOt> ANSWER . WHO HA* >

( an or ho r ome’wh/ boeent inoiaa,

Perhaps the most important outcome of the Battle

in Seattle was that, despite efforts by the mass

media to denigrate and dismiss the protest, key

issues facing the world’s people were for once

given center stage. It was a watershed event in

terms of grassroots mobilisation for change. But

the activists present agreed that it was just a

beginning.

-------------------

father

IS SICK.

.

( TMME »*

XL

The People s Health Assembly, with its proposed

People’s Charter for Health’ and plans for follow

up action, holds promise of being another signifi

cant step forward in the struggle for a healthier,

more equitable approach to trade, social develop

ment, and participatory democracy. For that

promise to be realised, people and groups from a

wide diversity of concerns and sectors must

become actively involved around our common

concern: the health and well-being of all people

and of the planet we live on.

EDUCATICN

fov

PARTFOTATIOH

ACTION for change

he term Popular Education,’ or Learner

centered education,’ refers to participatory

learning that enables people to take collec

tive action for change. Many community-based

health initiatives have made use of these enabling

methodologies, adapting them to the local circum

stances and customs. Particularly in Latin

America, methods of popular education have been

strongly influenced by the writings and aware

ness-raising praxis’ of Paulo Freire (whose best

known book is Pedagogy ofthe Oppressed}

Education of the oppressed—the method

ology of Paulo Freire

In the mid-1960s the Brazilian educator, Paulo

Freire developed what he called education for

liberation, an approach to adult literacy training,

(which proved so revolutionary that Freire was

jailed and then exiled by the military junta.) With

his methods, non-literate workers and peasants

learned to read and write in record time—because

their learning focused on what concerned them

most: the problems, hopes and frustrations in their

lives. Together they critically examined these

concerns, which were expressed in key words and

provocative pictures. The process involved identi-

ARE in

DEBT

6BT IWU6H

MOT SMOVOH

K rain. 7

HE« MOTHER

DOESN’T

BASA6TFKEO

<

hb a.

SHE HAS

O/AKMMEA

fication and analysis of their most oppressive

problems, reflection on the causes of these, and

(when feasible) taking action to ’change their

world’.

Learning as a two-way or many-way

process

With Freire’s methodology, problem-solving

becomes an open-ended, collective process. Ques

tions are asked to which no one, including the

facilitator have ready answers. The teacher is

learner and the learners, teachers.’ Everyone is

equal and all learn from each other. The contrast

with the typical classroom learning is striking.

In typical schooling, the teacher is a superior

being who knows it all’. He is the owner and

provider of knowledge. He passes down his

knowledge into the heads of his unquestioning

and receptive pupils, as if they were empty pots.

(Freire calls this the banking' approach to learning

because knowledge is simply deposited.)

In education for change, the facilitator is one of

the learning group, an equal. She helps partici

pants analyse and build on their own experiences

and observations. She respects their lives and

ideas, and encourages them to respect and value

one another’s. She helps them reflect on their

shared problems and the causes of these, to gain

confidence in their own abilities and achieve

ments, and to discuss their common concerns

critically and constructively, in a way that may

lead to personal or collective action. Thus, accord

ing to Freire, the learners discover their ability to

‘change their world’. (For this reason Freire calls

this a ‘liberating’ approach to learning).

Ctrnrunicaticn as if Pecple ottered

The key difference between typical schooling’ and

education for change' is that the one pushes ideas

into the student's heads, while the other draws

ideas from them. Typical schooling trains students

to conform, comply, and accept the voice of

authority without question. Its objective is to

maintain and enforce the status quo. It is

disempowering. By contrast, education-for-change

is enabling. It helps learners gain ‘critical aware

ness’ by analysing their own observations, draw

ing their own conclusions and taking collective

action to overcome problems. It frees the poor and

oppressed from the idea that they are helpless and

must suffer in silence. It empowers them to build a

better world—hence it is education for transfor

mation’.

examples of

health progranmes

have combatted

ROOT CAUSES of

POOR HEALTH

ommunity-based health programmes in

various countries have brought people

-^together to analyse the root causes of their

health-related problems and to take health into

their own hands' through organised action. In

places where unjust government policies have

worsened the health situation, community health

programmes have joined with popular struggles

for fairer and more representative governments.

The following are a few examples of programmes

where people’s collective ‘struggle for health’ has

led to organised action to correct inequalities,

unfair practices and/or unjust social structures.

£

that the poor often went without. Health workers

helped villagers organise to gain democratic,

community control of the wells. This meant more

water and better health for the poor. And it helped

people gain confidence that through organised

action they could indeed better their situation.

Another example concerns schooling. Villagers

know education is important for health. But most

poor children of school age must work to help

their families survive. So the GK communities

started a unique school, which stresses coopera

tion, not competition. Each day the children able to

attend the school practise teaching each other.

After school these same children teach those

unable to attend school. This process of teaching

one another and working together to meet their

common needs, sews seeds for cooperative action

for change.

Jamkhed, India. For over three decades two

doctors, Mabel and Raj Arole, have worked with

poor village women, including traditional mid

wives. These health facilitators have learned a

wide variety of skills. They bring groups of

women together to discuss and try to resolve

problems. In this way, they have become informal

community leaders and agents of change. They

help people rediscover the value of traditional

forms of healing, while at the same time demysti

fying Western medicine, which they learn to use

carefully in a limited way.

In Jamkhed. women's place relative to men's has

become stronger. Women have found courage to

defend their own rights and health and those of

their children. As a result of the empowerment

and skills-training of women, child mortality has

dropped and the overall health of the community

has improved dramatically.

TOPAY-J

Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK). GK is a commu

nity health and development programme in

Bangladesh that began during the war for

national independence. Village women, many

of them single mothers (the most marginalised

of all people), have become community health

workers and agents of change. Villagers collec

tively analyse their needs and build on the

knowledge and skills they already have. Re

peatedly health workers have helped villagers

take action to defend their rights.

One example of this is over water rights. In

analysing their needs, families agreed that

access to good water is central to good health.

UNICEF had provided key villages with tube

wells. But rich landholders took control of the

wells and made people pay so much for water

People's Jfealth Assembly

.

SOCIAL

DO

£

farm people leave

)

AWD MO

to c/n

h' rW L

M?1

The Philippines. In this island nation, during the

dictatorship of Fernando Marcus, a network of

community-based health programmes (CBHPs)

evolved to help people deal with extreme poverty

and deplorable health conditions. Village health

workers learned to involve people in what they

called situational analysis. Neighbours would

come together to prioritise the main problems

affecting their health, identify root causes and

work collectively towards solutions.

In these sessions it became clear that inequality—

and the power structures that perpetuate it—

were at the root of ill health. Contributing to the

dismal health situation were: unequal distribution

of farm land (with huge land-holdings by

transnational fruit companies), cut backs in public

services, privatisation of the health system, and

miserable wages paid to factory and farm workers.

The network of community-based programs urged

authorities to improve this unjust situation. When

their requests fell on deaf ears, they organised a

popular demand for healthier social structures.

These included free health services, fairer wages,

redistribution of the land to the peasantry, and

above all else, greater accountability by the gov

ernment to its people.

The fact that the CBHP network was awakening

people to the socio-political causes of the poor so

threatened the dictatorship that scores of health

workers were jailed or killed. But as oppression

grew, so did the movement. The CBHP network

joined with other movements for social change.

Finally, the long process of awareness-raising and

cooperative action paid off. In the massive peace

ful uprising of 1986, thousands of citizens con

fronted the soldiers, putting flowers into the

muzzles of their guns. The soldiers (many of

whom were peasants themselves, acquiesced.

After years of organising and grassroots resistance,

the dictatorship was overthrown. (Unfortunately,

the overall situation has not changed greatly. With

persistent domination by the US government and

multinational corporations, gross inequities

remain and the health of the majority is still

dismal. The struggle for a healthier, more equita

ble society continues.)

Nicaragua. Similar to the

CBHP in the Philippines

under Marcus, in Nicaragua

during the Somoza dictator

ship a network of non-government community health

programmes evolved to fill

the absence of health and

other public services. Grass

roots health workers known

as Brlgadistas de Salud

brought groups of people together to conduct

community diagnoses of problems affecting their

health, and to work together toward solutions. As

in the Philippines, the ruling class considered such

community participation subversive. Scores of

health workers were ’disappeared' by the National

Guard and paramilitary death squads. Many

health workers went underground and eventually

helped form the medical arm of the Frente

Sandinista, the revolutionary force that toppled the

dictatorship.

After the overthrow of Somoza, hundreds of

Brigadistas joined the new health ministry. With

their commitment to strong participation, they

helped to organise and conduct national Jornadas

de Salud’ (Health Days). Their work included

country-wide vaccination, malaria control, and

tuberculosis control campaigns. At the same time,

adult literacy programmes, taught mainly by

school children, drastically increased the nation's

level of literacy.

As a result of this participatory approach, health

statistics greatly improved under the Sandinista

government. Since the Sandinistas were ousted

with the help of the US government, health serv

ices have deteriorated and poverty has increased.

Many health indicators have suffered. But fortu

nately, communities still have the skills and selfdetermination necessary to meet basic health

needs and assist one another in hard times.

Project Piaxtla, in rural Mexico. In the mountains

of western Mexico in the mid-1960s a villager-run

health programme began and gradually grew to

cover a remote area unserved by the health sys

tem. Village health promoters, learning in part by

trial and error, developed dynamic teaching

methods to help people identify their health needs

and work together to overcome them.

Over the years, Piaxtla evolved through three

phases: 1) curative care, 2) preventive measures,

and 3) socio-political action.

It was the third phase that led to the most impres

sive improvements in health. (In two decades,

child mortality dropped by 80%.) Through Com

munity Diagnosis, villagers recognised that a big

david wemer

Cbmrijriicaticri as if Pecple Mattered

cause of hunger and poor health was the unconsti

tutional possession of huge tracts of farmland by a

few powerful landholders, for whom landless

peasants worked for slave wages, 'fhe health

promoters helped the villagers organise, invade

the illegally large holdings, and demand their

constitutional rights. Confrontations resulted, with

occasional violence or police intervention. But

eventually the big landholders and their govern

ment goons gave in. In two decades, poor farmers

reclaimed and distributed 55% of good riverside

land to landless farmers. Local people agree that

their struggle for fairer distribution of land was

the most important factor in lowering child mor

tality. And as elsewhere, people’s organised effort

to improve their situation helped them gain the

self-determination and skills to confront other

obstacles to health.

The practical experience of Project Piaxtla and its

sister programme, PROJIMO, gave birth to Where

There Is No Doctor,’ ‘Helping Health Workers

Learn,’ Disabled Village Children’ and the other

books by David Werner that have contributed to

community-based health and rehabilitation initia

tives worldwide.

nefvyorfeang anol

COMMUNfCATfOMS

amon^.

$ S R tVT S

programmes anol movements

From isolation to united struggle

^n different but parallel ways, each of the com

1 munity initiatives briefly described above

-••developed enabling participatory methods to

help local people learn about their needs, gain self

confidence, and work together to improve their

well-being. Each forged its own approaches to

what we referred to earlier as education for

change.

At first community health initiatives in different

countries tended to work in isolation, often una

ware of each other’s existence. There was little

communication and sometimes antagonism

between them. But in time this changed, partly

due to growing obstacles to health imposed by the

ruling class. (Nothing solidifies friendship like a

common oppressor.) Programmes in the same

country or region began to form networks or

associations to assist and learn from each other. By

joining forces, they were able to form a stronger,

more united movement, especially when confront

ing causes of poor health rooted in institutional

ised injustice and inequity.

National networks in Central America and the

Philippines provided strength in numbers that

gave community health programmes mutual

protection and a stronger hand to overcome

obstacles.

In the 1970s, community-based health pro

grammes in several Central American countries

formed nationwide associations Then in 1982 an

important step forward took place. Village health

workers from CBHPs in the various Central

American countries and Mexico met in Guatemala

to form what became the Regional Committee of

Community Health Promotion.

This Regional Committee has helped to build

solidarity for the health and rights of people

throughout Central America. Solidarity was

particularly important during the wars of libera

tion waged in Central America (and later in

Mexico), when villages were subjected to brutal

and indiscriminate attacks by repressive govern

ments and death squads.

Learning from and helping each other

One of the most positive aspects of networking

among grassroots programmes and movements

has been the cross-fertilisation of experiences,

methods and ideas.

Central America. For example, in the 1970s, the

Regional Committee and Project Piaxtla organised

a series of ‘intercambtos educativus’ or educa

tional interchanges. Community health workers

from different programmes and countries came

together to learn about each other's methods of

confidence-building, community diagnosis, and

organisation for community action.

At one of these Intercambios, representatives from

Guatemala, in a highly participatory manner,

introduced methods of ‘conscientizacidn’ (aware

ness-raising) developed by Paulo Freire, as they

had adapted them to mobilise people around

health-related needs in Guatemala.

<

A

is?

Appropriate planning starts with PEOPLEf

Peqple's Health Assenbly

Likewise the village health promoters of

Piaxtla, in Mexico, introduced to participants a

variety of methods of discovery-based learn

ing, which they had developed over the years

(see below).

Reaching across the Pacific. An early step

towards more global networking took place in

19??, when an educational interchange was

arranged between community health workers

from Central America and the Philippines. A

C

'--- l.\ / /

’A

team of health workers from Nicaragua,

Honduras and Mexico visited a wide range of

community-based health programmess, rural

and urban, in the Philippines. In spite of

erished populations. So the world's nations en

language barriers, the sharing of perspectives and

dorsed the Alma Ata Declaration, which outlined

sense of solidarity that resulted were profound.

a revolutionary strategy called Primary Health

Social and political causes of ill health in the two

Care (PHC), to reach the goal of Health for All by

regions were similar. Both the Philippines and

the Year 2000. The vision of PHC was modeled

Latin America have a history of invasion and

after the successful grassroots community-based

subjugation, first by Spain and then by the United

health programmes in various countries, as well as

States. Transnational corporations and the Interna

the work of barefoot doctors’ in China. It called

tional Financial Institutions have contributed to

for strong community participation in all phases,

polarising the rich and poor. And in both regions,

from planning and implementation to evaluation.

the US has backed tyrannical puppet governments

that obey the wishes of the global marketeers in

Health for No One? We have entered the 21st

exchange for loans and weapons to keep their

century and are still a long way away from 'Health

impoverished populations under control.

for AIL’ If our current global pattern of short

sighted exploitation of people and environment

Participants in the Latin American-Philippine

continue, we will soon be well on the road to

interchange came away with a new understanding

‘Health for No One.' The current paradigm of

of the global forces behind poor health. They

economic development, rather than eliminating

became acutely aware of the need for a worldwide

poverty, has so polarised society that combined

coalition of grassroots groups and movements to

social and ecological deterioration endangers the

gain the collective strength needed to construct a

w'ell-being of all. But sustainable well-being is of

healthier, more equitable, more sustainable global

secondary concern to the dictators of the global

environment.

economy, whose all-consuming objective is

GROWTH AT ALL COST!

It has been said that Primary Health Care failed.

But in truth, it has never been seriously tried.

Because it called for and the full participation of

the underprivileged along with an equitable

RIMARY

economic order, the ruling class considered it

subversive. Even UNICEF—buckling under to

|

| ealth for All? The United Nations estab

accusations by its biggest founder (the US govern

-iJ

-I lished the World Health Organization

ment) that it was becoming ‘too political’—en

|

I (WHO) in 1945 to co-ordinate interna

dorsed a disembowelled version of PHA called

tional policies and actions for health. WHO de

Selective

Primary Health Care. Selective PHC has

fined health as ‘complete physical, mental, and

less to do with a healthier, more equitable social

social well-being, and not merely the absence of

order than with preserving the status quo exist

disease.’

ing wealth and power.

•fho life and death of

Primary Health Care

But in spite of WHO and the United Nations'

declaration of Health as a Human Right, the

poorer half of humanity continued to suffer the

diseases of poverty, with little access to basic

health services. In 1987, WHO and UNICEF

organised a watershed global conference in Alma

Ata, USSR. It was officially recognised that the

Western Medical Model, with its costly doctors in

giant ‘disease palaces,' had failed to reach impov-

The World Bank’s take-over of health planning.

The kiss of death to comprehensive PHC came in

1993 when the World Bank published its World

Development Report, titled ‘Investing in Health.'

The Bank advocates a restructuring of health

systems in line with its neo-liberal free-market

ideology. It recommends a combination of privati

sation, cost-recovery schemes and other measures

that tend to place health care out of reach of the

Cfenminicaticn as if Etecple bettered

poor. To push its new policies down the throat of

poor indebted countries, it requires acceptance of

unhealthy policies as a pre-condition to the grant

ing of bail-out loans.

In the last decade of the 20th century, the World

Bank took over WHO’s role as world leader in

health policy planning. The take-over was pow

ered by money. The World Bank’s budget for

’Health’ is now triple that of WHO’s total budget.

With the World Bank's invasion of health care,

comprehensive PHC has effectively been shelved.

Health care is no longer a human right. You pay

for what you get If you are too poor, hungry and

sick to pay, forget it. The bottom line is business as

usual. Survival of the greediest!

vision is to advance towards a healthy global

community founded on fairer, more equitable

social structures. It strives towards a model of

people-centred development, which is participa

tory, sustainable, and makes sure that all people’s

basic needs are met.

The IPHC is not just a South-South network for

underdeveloped countries, but also includes

grassroots struggles for health and rights among

the growing numbers of poor and disadvantaged

people in the Northern overdeveloped’ countries.

For the last two years the Third World Network

and the IPHC have worked closely together in the

preparations for the People’s Health Assembly.

QwHAT po you SEE HE.RE?)

Cc^ALfTli^NS for tho

health a nJ uell-teirg

HUMANITY

^w'imary Heath Care as envisioned at Alma

I ^ZAta was never given a fair chance,—and

I

globalisation is creating an increasingly

polarised, unhealthy and unsustainable world. —

In response, a number of international networks

and coalitions have been formed. Their goal is to

revitalise comprehensive PHC and to work to

wards a healthier, more equitable, more sustain

able approach to development. Two of these

coalitions, which have both participated in organ

ising the People’s Heath Assembly, are the follow

ing.

MJ

VTethodologies

of

EPUCATipN for CHA

The Third World Health Network (TWHN)

based in Malaysia, was started by the Third World

Network, which has links to the International

Consumers Union. The TWHN consists of progres

sive health care movements and organisations,

mainly in Asia. One important contribution of the

Network has been the collection of a substantial

library of relevant materials, their lobby for

North-South equity and the promotion of net

working between Third World organisations.

The International People s Health Council

(IPHC) is a coalition of grassroots heath pro

grammes, movements and networks. Many of its

members are actively involved in community

work. Like the TWHN, the IPHC is committed to

working for the health and rights of disadvan

taged people—and ultimately, of all people. Its

/

ne of the most rewarding activities of the

IPHCwvas a post-conference workshop

hekf in Cape Town, South Africa, on

Methodologies of Education for Change. Health

educator/from Africa, Central America, Mexico, /

North America, the Philippines and Japan—most

with many years of experienced- facilitated group

activities. Each demonstrated Zome of the innova/

tiye learning and awareness/aising methods they

xlse in their different countjnes. The challenge oj

/ the workshop was to d<

or adapt methods of

education for action to icet the new challenges

of today’s globalised afid polarised world. /

From micro to ma/ro, local to global/ways

of making and uciderstanding the links

The Cape Town Workshop participants agreed

that a global gradroots movement need/ to be

mobilised to he/p rein in the unhealthwand unsus

tainable aspects of globalisation.

/

To do thisyeaming tools, methods, Znd teaching

aids mus/be developed to help ordinary people

see the l/nks between their local p/oblems and

Etecple's Hsalth. Asserrbly

/

s

:1

This emphasis on medically-driven pro

grammes is reflected in the internal organisa

tional structure of many ministries of health

and WHO itself: such arrangements reinforce

the tendency towards vertical technical

approaches and militate against implementa

tion of comprehensive PHC.

□

I

A

Health care continues to be an instrument of

social control.

Overtly unethical behaviour and human

rights violations by health personnel are,

z

unfortunately, not only a disgraceful part of

health history, but persist, particularly in

situations of war and political oppression.

However, health care as an instrument of

social control is much more subtle and

widespread. Central to this is the mystifica

tion by the health professions of the real

causes of illness, which is often attributed to

ill-considered individual behaviour and

natural misfortune, rather than to social

injustice, economic inequality and oppressive

political systems. Examples of such individualised

and conservative approaches range from the

promotion of family planning, in isolation from

social development, as a means of population

control, to oppressive forms of health education

that neglect the social determinants of certain

lifestyle’ factors linked to ill-health.

values

and suggested

acfaon

he vision of the Peoples’

Health Assembly is of an

accessible, affordable, equitably distrib

uted, appropriate and sustainable health system,

based on the principles of comprehensive PHC

and responsive to its users. Mechanisms for

popular participation in the health system should

ensure its accountability and also contribute to the

movement for participatory democracy in society

at large.

In order to achieve such a vision the following

broad types of action are suggested:

Advocate atnationaland international levels for

prioritisation ofand investment in health.

There is accumulating evidence that investment in

the social sectors has not only contributed to social

development but has also often led to economic

Etecple's Health Asserrtoly

icy'

/

da\id w erner

development. The Good Health at Low Cost

examples of Cuba, Sri Lanka, China, Costa Rica

and Kerala State in India demonstrate that a

commitment to broad-based, equitable develop

ment, with investment in women’s education,

health and welfare, has a significant and sustain

able impact on the health and social indicators of

the whole population. To realise the equity essen

tial for a healthy society, evidence suggests that a

strong, organised demand for government respon

siveness and accountability to social needs is

crucial. Recognition of this important challenge

informed the Alma Ata call for stronger commu

nity participation. To achieve and sustain the

political will to meet all people’s basic needs, and

to regulate the activities of the private sector, a

process of participatory democracy—or at least a

well-informed movement of civil society—is

essential: analysts have noted that such political

commitment was achieved in Costa Rica through a

long history of egalitarian principles and democ

racy, in Kerala through agitation by disadvan

taged political groups, and in Cuba and China

through social revolution. ‘Strong’ community

participation is important not only in securing

greater government responsiveness to social

needs, but also to mobilize an active, conscious

and organised population critical to the design,

implementation and sustainability of comprehen

sive health systems.

Good Health a+ Lovy Cost

■ . Wespite the dismal living conditions and health

11 situation in many poor countries, a few poor

states have succeeded in making impressive

strides in improving their people's health. In 1985,

the Rockefeller Foundation sponsored the Good

Health at Low Cost’ study to explore why certain

poor countries with low national incomes managed to

achieve acceptable health statistics. More specifically,

they asked how China, the state of Kerala in India. Sri

Lanka, and Costa Rica attained life expectancies of

65-70 years with GNPs per capita of only USS3001,300.

Upon completing the study, the authors determined

that the increased life expectancies were due to a

reduction in child and infant mortality rates (IMR) in

the four states and were accompanied by declines in

malnutrition and, in some cases, in the incidence of

disease. These remarkable improvements in health

were attributed to four key factors:

co:

co:

co:

co:

political and social commitment to equity (i.e. to

meeting all people s basic needs):

education for all. with an emphasis on the

primary level:

equitable distribution throughout the urban and

rural populations of public health measures and

primary health care:

an assurance of adequate caloric intake at all

levels of society in a manner that does not

replace indigenous agricultural activity.

The importance of factor one. a strong political and

social commitment to equity, cannot be overempha

sised. While the course of action may vary, equitable

access to health services necessitates breaking down

the social and economic barriers that exist between

disadvantaged subgroups and medical services.

Of the four regions investigated. China was the most

exceptional in terms of equality. Whereas in the other

three states, the decline in IMR was largely due to

better social services (improved healdi care coverage,

immunisation, water and sanitation, food subsidies

and education). China’s improvements were rooted

in fairer distribution of land use and food production.

The population was encouraged to become more selfsufficient. rather than to become dependent on

government assistance.

While all four regions developed cooperative,

community-oriented approaches to resolving prob

lems and meeting basic needs, in die 15 years since

the Rockefeller study, China has had the most success

in maintaining Its advances towards ‘good health at

low cost’.

Source: Werner, D. and Sanders, D. (1997) Questioning

the Solution: The Politics ofPrimary Heath Care and

Child Survival. Palo Alto: Health Wrights, p. 115.

Concerted action should be taken to persuade

individual governments to invest in health. WHO

needs to be lobbied to assume a stronger advocacy

role. It should take the lead in analysing and

publicising the negative impact that globalisation

and neoliberal policies are having on vulnerable

groups. It should spearhead moves to limit health

hazards aggravated by globalisation, including

trade in dangerous substances such as tobacco and

narcotics. It needs to strongly assert health as a

Human Right and publicise and promote the

benefits of equitable development and investment

in health. The extent to which WHO and govern

ments play such roles will depend on the extent to

which popular mobilisation around health occurs.

Communities have to be active and organised in

demanding these changes.

Demystify the causes ofill-health and

promote an understanding ofits social

determinants.

Since health'and ‘medicine' have become virtually

synonymous in the popular consciousness, it is impor

tant to communicate the evidence for the fact that illhealth results from unhealthy living and working

conditions, from the failure ofgovernments to provide

health-promoting conditions through policies that

ensuregreater equity. It then becomes obvious that

health problems are the result of structural factors and

political choices and that their solution cannot lie in

health care alone, but requires substantial economic

reform as well as comprehensive and intersectoral health

action. Mechanisms to disseminate this message,

including the use ofthe mass media, must be identified

and exploited.

Advocate andpromote policies and

projects that emphasise intersectoral

action for health.

Government health ministries and international health

agencies need to be pressed to engage as partneis Mth

the sectors, agencies and socialgroups critical to the

achievement ofbetter health. Policy development must

be transparent and inclusive to secure broader under

standing and wider ownership ofhealth policies.

Structures involving the different partners need to be

createdat different levels from local to national, or

within such settings as schools and workplaces. The

priority should be to focus on geographical areas with

the greatest health needs and involve communities and

their representatives at local level. Subgroups with

responsibility for health, within local, provincial or

nationalgovernment (e.g. health committees oflocal

government councils) should bepromoted and should

have links to the above structures. This has occurred in

some ofthe Healthy Cities projects in both industrial

ised and de veloping countries. Currently the Brazilian

law requires differentgroups to discuss the health

policies to be promoted, and includes community and

consumerparticipation.'

The VM-iraliTrtf-im of Ffeelth Chre and the Cballen^ cf Ifealth fcr All

Infersccfora! action fo

traffir accidents

flw the early 1970s, Denmark had the highest rate of

■ child mortality from traffic accidents in Western

I Europe. A pilot study was started in Odense.

Forty-five schools participated in an exercise carried

out with accident specialists, planning officials, the

police, hospitals and road authorities, to identify the

specific road dangers that needed to be addressed. A

network of traffic-free foot and cycle paths were

created as well as a parallel policy of traffic speed

reduction, road narrowing and traffic islands.

Following the success of the pilot study, the Danish

Safe Routes to Schools Programme has been imple

mented in 65 out of 185 proposed localities and the

number of accidents has fallen by 85%. Accidents

can. and must, be avoided. It is the responsibility of

each one of us, but many initiatives can and should

come from local authorities.

Source: Walking and Cycling in the City. WHO. 1998E.

p. 64

A process of engaging the public in a dialogue

about public health problems and in setting goals

for their control can both popularise health issues

and become a rallying-point around which civil

society can mobilise and demand accountability. It

can also create the basis for popular involvement

in implementation of health initiatives.

Actively develop comprehensive, community-based

programmes

Most programmes addressing priority health

problems start from a health care or services

perspective. While curative, personal preventive

/-■'•J

1

if

and caring actions are very important and still

constitute the core of medical care, comprehensive

PHC demands that they be accompanied by

rehabilitative and promotive actions. In address

ing priority health problems comprehensively, by

defining and implementing promotive, preventive,

curative and rehabilitative actions, a set of activi

ties common to a number of health programmes

will be developed as well as a horizontal infra

structure.

The principles of programme development apply

equally to all types of health problems, from

diarrhoea to heart attacks to domestic violence.

After the priority health problems in a community

have been identified, the first step in programme