ONE DAY MEETING ON RIGHT TO HEALTH MARCH 15TH 1997

Item

- Title

- ONE DAY MEETING ON RIGHT TO HEALTH MARCH 15TH 1997

- extracted text

-

L

T

10

0

20

30

50

40

60

70

TSO

90

GHI

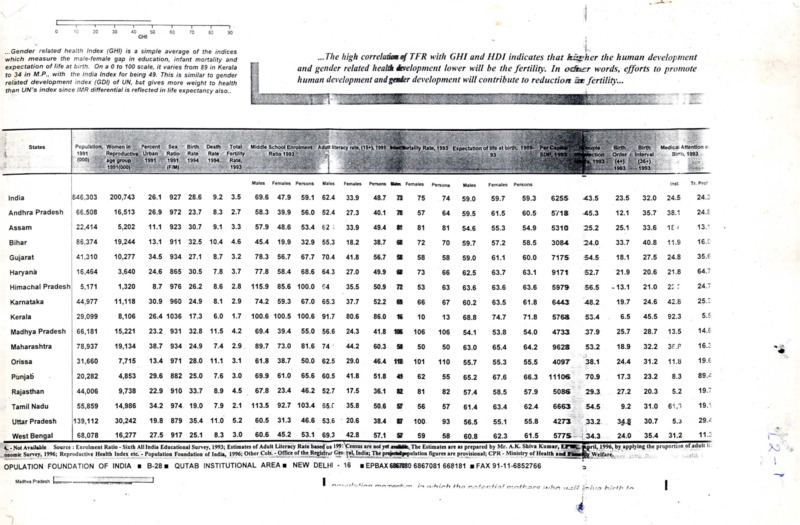

...Gender related health Index (GHI) is a simple average of the indices

which measure the male-female gap in education, infant mortality and

expectation of life at birth. On a 0 to 100 scale, it varies from 89 in Kerala

to 34 in M.P., with the India Index for being 49. This is similar to gender

related development index (GDI) of UN, but gives more weight to health

than UN’s index since IMR differential is reflected in life expectancy also..

I

Percent Sex

Urban Ratio

1991

1991

Birth

Rate

1994

Death

Total

Rate

1994

Fertility

Rate,

sz

. ■izz zz'

/

.

Population, Women In .

1991

Reproductive

(000)

age group

States

...The high correlation of TFR with GHI and HDI indicates that Richer the human development

and gender related health inelopment lower will be the fertility. In odhucr words, efforts to promote

human development andgader development will contribute to reduction an fertility...

Z

■

Middle School Enrolment

■/

,-r’‘

'

'

Adult literacy rate, (15+), 1991

Srs

ectlon

Order

Interval

Medical Attention a

Birth, 1993

. .v.... /7Z:/ZS

Males

Females

Persons

Males

Females

Persons

Females

Persons

Males

Females

Persons

Inst

Tr. Prof

1846,303

200,743

26.1

927

28.6

9.2

3.5

69.6

47.9

59.1

62.4

33.9

48.7

73

75

74

59.0

59.7

59.3

6255

43.5

23.5

32.0

24.5

24.:

Andhra Pradesh

66.508

16,513

26.9

972

23.7

8.3

2.7

58.3

39.9

56.0

52.4

27.3

40.1

71

57

64

59.5

61.5

60.5

5718

45.3

12.1

35.7

38.1

24. E

Assam

22,414

5,202

11.1

923

30.7

9.1

3.3

57.9

48.6

53.4

62

33.9

49.4

St

81

81

54.6

55.3

54.9

5310

25.2

25.1

33.6

18

13/

Bihar

86,374

19,244

13.1

911

32.5

10.4

4.6

45.4

19.9

32.9

55.3

18.2

38.7

62

72

70

59.7

57.2

58.5

3084

24.0

33.7

40.8

11.9

16.C

Gujarat

41,310

10,277

34.5

934

27.1

8.7

3.2

78.3

56.7

67.7

70.4

41.8

56.7

S

58

58

59.0

61.1

60.0

7175

54.5

18.1

27.5

24.8

35.6

Haryana

j 16,464

3,640

24.6

865

30.5

7.8

3.7

77.8

58.4

68.6

64.3

27.0

49.9

fit

73

66

62.5

63.7

63.1

9171

52.7

21.9

20.6

21.8

64.7

5,171

1,320

8.7

976

26.2

8.6

2.8

115.9

85.6 100.0

64

35.5

50.9

n

53

63

63.6

63.6

63.6

5979

56.5

-13.1

21.0

2::

24.7

' 44,977

11,118

30.9

960

24.9

8.1

2.9

74.2

59.3

67.0

65.3

37.7

52.2

61

66

67

60.2

63.5

61.8

6443

48.2

19.7

24.6

42.8

25/

Kerala

29,099

8,106

26.4 1036

17.3

6.0

1.7

100.6 100.5

100.6

91.7

80.6

86.0

16

10

13

68.8

74.7

71.8

5763

53.4

6.5

45.5

92.3

5.5

Madhya Pradesh

66,181

15,221

23.2

931

32.8

11.5

4.2

69.4

39.4

55.0

56.6

24.3

41.8

106

106

106

54.1

53.8

54.0

4733

37.9

25.7

28.7

13.5

14.6

Maharashtra

78,937

19,134

38.7

934

24.9

7.4

2.9

89.7

73.0

81.6

74

44.2

60.3

59

50

50

63.0

65.4

64.2

9623

53.2

18.9

32.2

se.p

16.:

Orissa

31,660

7,715

13.4

971

28.0

11.1

3.1

61.8

38.7

50.0

62.5

29.0

46.4

11B

101

110

55.7

55.3

55.5

4097

38.1

24.4

31.2

11.8

19. e

Punjab

20,282

4,853

29.6

882

25.0

7.6

3.0

69.9

61.0

65.6

60.5

41.8

51.8

45

62

55

65.2

67.6

66.3

11106

70.9

17.3

23.2

8.3

89/

Rajasthan

44,006

9,738

22.9

910

33.7

8.9

4.5

67.8

23.4

46.2

52.7

17.5

36.1

82

81

82

57.4

58.5

57.9

5086

29.3

27.2

20.3

5.2

19.7

Tamil Nadu

55,859

14,986

34.2

974

19.0

7.9

2.1

113.5

92.7 103.4

65. C

35.8

50.6

S’

56

57

61.4

63.4

62.4

6663

54.5

9.2

31.0

61.3

19/

Uttar Pradesh

139,112

30,242

19.8

879

35.4

11.0

5.2

60.5

31.3

53.6

20.6

38.4

87

100

93

56.5

55.1

55.8

4273

33.2

3!t8

30.7

5.3

29/

60.6 45.2 53.1 69.3

8.3 3.0

42.8

16,277

27.5_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

917 25.1

68,078

57.1 57

West Bengal_________________________

59

61.5

58

62.3

5775 -434.3

60.8

24.0

35.4

31.2

11.3

India

Himachal Pradesh^

Karnataka

46.6

jril, 1996, by applying the proportion of adult Ii

1993; Estimates of Adult Literacy Rate based

not -yet awirfiip The Estimates are as prepared by Mr. A.K. Shiva Kumar,

4. - Not Available Source : Enrolment Ratio - Sixth All India Educational Survey,

...

. 1 on 1991 yensus are

.

£. n

------- j..tr

—uu Index etc. - Population

— r—j-.:-------of

r »_

j:- innx.

r nUfinn figures are provisional;

onomic Survey, 1996;

Reproductive

Health

Foundation

India,

1996; Other r'nic

Cols. -- Offir*

Office nf

of th*

the Rwidr^r

Registrar Gen

Gen ral.

^al, TnrfiaIndia; T>»*

The projededpapulation

provisional; CPR

CPR -- Ministry

Ministry of

of Health

Health and

and TaiMi

OPULATION FOUNDATION OF INDIA ■ B-28 ■ QUTAB INSTITUTIONAL AREA ■ NEW DELHI - 16

Madhva Pradesh

■ EPBAX 68671180 6867081 668181 ■ FAX 91-11-6852766

Welfare.

I

□

J

/I

z-t

m

n-.r'tb.^rc’ '.jt/hn

\rrti

4

hsrfb

I

L.^

Ella, All, Allah, . AUM,

, SHREE, A to Z, That is that

In/TiTUTB of Health 0 ComPARiriVE fflEoicinE. Vogr Therapy

Cehtre

£23, 9th ‘A’ Main Road, 5th Block, Jayanacara

Bangalore, Karnataka, INDIA - 560 041

St: +91-80-6635256; FAX : +91-80-663-5175

Five Doctors & Professor Emeritus Around the World

Studied in Michigan & Bangalore Himalayas have evolved

VACCINES having Lasting'Curative' & 'Instant Relief' Value

1. Psycho-Spiritual % Mind-Space Vaccine, Scientifically &

Philosophically evolved for prevention & cure.

2. Edible Local Fresh & Tender Herbal Vaccines.

3. Dietary combination & MEDICINAL SECRETS OF FOODS observed

over centuries for preventive and lasting cure & relief.

4. AUTO Unit Vaccine, manufactured in one’s own body, at

each moment in blood, fluids, mind, cells etc.,

5. Highly-ground & ELECTRONICALLY CHARGED VACCINES Natural, Inorganic & Organic Chemicals - diluted as Oral

Drops, Tablets, etc., with ‘PUREST" vehicle.

For Every Disease & Symptoms

each time

We can & should aim & wipeout incurability

from Womb to Tomb & Beyond for generations

and correct GENES by Sound Electrons & Hygiene

Essence being brought-out in One World Book in all th e

languages at the same time, updated periodically.

Over 200 countries registering for training at

Bangalore.

Herambhaha, Ganapa, Brahma

Dr. H.R.B., SADA.A.

TOP_Q Graphics//e:\mallanna\hrb\bro 1 .doc

LS. 3

Forum Interview

Ethics and health

Zbigniew Bankowski

World Health Forum asked Dr Eilif Liisberg to talk to Professor

considerations that have guided the development of medicine

and public hea'tn and about their place in today's society.

Professor Bankowsk. medical ethics has been largely

dominated by the Hippocratic Oath. What were its

basic principles, and are they still valid in modern

society?

In mv opinion the Hippocratic Oath,

although formulated about 2400 years ago,

will be pertinent tor a long time to come. The

Oath itself is a very short statement and

nobody knows who really wrote it; it is probablv based on writings by Hippocrates and

others, so I would prefer to refer to the

writings rather than the Oath alone. The

Hippocratic writings placed certain obli

gations on doctors, such as beneficence,

non-maleficencc, and confidentiality, as well

as some prohibitions — for example, those

against euthanasia - which are still followed

today.

Perhaps at this stage i*. e should define what we mean

by ethics, as this is important for the rest of our dis

cussion.

Ethics is a branch of philosophy dealing with

the distinction between right and wrong, and

Dr Lnsberg. an interna: ?-•= public health consultant,

was previously EdUO' c V.jrid Health Forum His address

is 43 avenue du Lig-?- ’219 Le Lignon, Geneva. Switzer

land

WorldHea’^Forurr • I';.-: ':’ • 199:

the moral consequences ot our actions.

Nearly all philosophical systems include an

ethical component. Wc in CIOMS look at

ethics from this same viewpoint of right and

wrong. Then immediately other questions

arise: right and wrong for whom? where? and

when? Those who support relativism in ethics

say it depends mainly on the circumstances,

11V1 v<x, v/l

.4aviK, ------------------- a moral

whereas

others

hold the view that

ethjca} prindplc has universal value,

In some cultures there is emphasis on the family and

the wider circle beyond the individual. Do the Hippo

cratic writings have a different connotation in different

societies?

Looking at the development of medical ethics

from a historical point of view, we see that

our Western civilization is based on Graeco

Roman and Judeo-Chnstian traditions. Our

so-called Western culture is unified by these

common roots, which for medical ethics are

the Hippocratic writings. Other cultures have

different roots - the Chinese and Hindu

traditions, for example. The limited contacts

between civilizations in the past had little

effect on each ones traditions, culture, and

ethical principles. Recent intercultural debates

about ethical issues immediately bring to light

these differences.

115

f

Forum Interview

Have any of the other ethical principles been codified?

In Chinese medicine, for example?

Not as far as 1 know. 1 am in close contact

with the Chinese medical profession and the)

arc vcrv interested to know how we codify

our ethical guidelines, and are considering

developing ethical principles adeouate for the

needs of their society. For example, the pnnciplcs of informed consent and natural rights

arc valued differently, compared with Western

culture, but this does not mean that China has

no ethical rules - it certainly has!

Do you think it is possible to have a set of basic,

universally accepted principles in ethics?

Mv personal opinion is that, at present,, wc

iot reaay

reads to trv

universal

arc not

uy to

iu develop -a —

JCU.W...?

r— -- ", ’

"IOr

code

of ethics - not -specifically

heakh

or

mediwl

ethics, but

just ethics broadly

medical etnics,

uui jusu

7 -jspeak

ing.

ing It may take centuries to reach such a con

sensus. Still, there are already some pnr

pnnciples

which arc universally recognized. In most

basic principle not to

animal societies it is a basicj>nnciple

till

another of its species. This

is aa biological

mh diiuinvi

> is

.

instinct and, as we are animals, the pnnciple

applies to us too, though it is not accorded the

same importance by all human societies.

\fV 1MV1* «*•

----------------- y

vz

e

,

In the field of ethics, as with any controver

sial issue in society or between different

cultural settings, dialogue must come first

to share ideas and concerns about the

Issues inherent in the Interaction of health

and ethics, and to collaborate In devising

and applying means of resolving them.

I

A great step forward has been the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights which was

developed bv the United Nations after the

Second World War. Human rights are univer

sal in the sense that society accepts them as

such, despite cultural differences in that what

■r Professor Zbigniew

Bankowskl was born in

Warsaw. Poland, in 1925

and is a naturalized Swiss

citizen His medical edu

cation and postgraduate

studies were completed

in Poland where he

x i

acquired his M D and

Ph D at the Faculty ol

Medicine, Lublin He has

held several teaching and

research positions in

experimental pathology in.

the Polish universities o’

Lublm. Lodz and Warsaw

as well as in Pans and Tunis Between 1965 and 1972 he

was responsible for the coordination ol research and trau

ma programmes of the World Health Orgamzation.

Geneva Since 1975 he has been Secretary-General of the

Council for Internationa’ Organizations of Medica

Sciences (ClOMS) Geneva. Switzerland He is the authoof many scientific papers m the fields of radiobiology ano

cancer and numerous articles and reviews dealing wrth

bioethics, drug safety, and medical terminology

is a high pnonty in one society may be less .

important in another. Although it is certainly

feasible to develop a universal code of ethics,

there are substantial differences in values that

are dear to each of us, and we do not like

others to interfere. In the field of edtics, as

with any controversial issue in society or

between different cultural settings, dialogue

must come first to share ideas and concerns

about the issues inherent in the interaction of

health and ethics, and to collaborate in devis

ing and applying means of resolving them.

C1OMS always encourages long debate along

ethical lines before surting to draw up any

normative guidelines.

An economist in Copenhagen once said in the Forum

that there was a contradiction in the doctors’ role to

do their best for individual patients and their social

responsibility to promote the common good (1).

What do you think about this dilemma?

This is a typical example of the conflict that

exists in ethical thinking, between the interests

and rights of the individual and the interests

Wjrit Health Forum • Volume 16 • 19u:

116

\

Ethics and health

and rights of the community. The interests of

individuals do not necessarily coincide with

those of the community - very often the

interests of the community are contrary to

those of the individual. Such conflict exists

and needs to be considered from all points

of new to sec if it is possible to work out a

compromise.

In health ethics, as with any ethical problem,

the first step is to initiate dialogue, to tty to

undersund what others are saying in order to

find a common denominator. I don t agree

with the relativist position that there are dif

ferent ethics: basic ethical principles are the

same for all, but the problem is that it means

different things to different people. If deci

sions about health in the community are

taken bv politicians and others, then the

medical profession has to say forcefully that it

has always been guided by ethical principles.

Medical ethics is at the root of the Hippo

cratic writings, and we in our particular societ)

are obliged to follow this same ethical code.

So you see the doctor as one who defends the rights

of his patients as individuals.

Yes! Doctors have a very special relationship

with their patients: the patient comes to the

doctor in hill confidence that he or she will be

helped; that creates a strong, intimate relation

ship between doctor and patient, whether it is

one person, a family, or a small community

group.

Doctors have sometimes found themselves in

difficult situations, such as assisting in capital

punishment or certifying that a person can tolerate

physical maltreatment or torture.

There is a UN Convention against torture to

which CIOMS contributed: we were

requested by WHO to draw up a code of

ethics for health personnel who might find

themselves involved in torture or maltreat-

mcnt of prisoners. It was a ver}’ controversial

issue and necessitated a long study. CIOMS

evolved six principles which were presented

by WHO to the United Nations; these were

Conflicts in medicine are inevitable when

one cannot satisfy the needs of all who

suffer.

adopted and included in the Convention.

They postulate that physicians and other

health workers are professionally trained

solely to maintain or improve the health of

those for whom they exercise professional

responsibility, and that it is unethical to use

their professional skills to allow any action

that may harm physical or mental health.

Of course, it is easier for physicians to take

a decision in line with their individual

conscience in a democratic society; in a totali

tarian one, a refusal to do what wras asked .

could very’ easily put them in danger. The

Convention came into effect only after twothirds of the Member States of the UN had

signed it but the UN has ven’ little authority

to enforce it. However, it does exist and is

there for anybody to refer to as an inter

national legal instrument.

As for the involvement of medical personnel

in the execution of a death sentence, I should

perhaps mention that the leading organization

for medical ethics is the World Medical

Association. The Association has developed a

very sensitive and well-elaborated declaration

and code of ethics which condemns the par

ticipation of physicians in capital pumshment.

Would you say that the Nuremberg trials of war

criminals after the Second World War were a major

breakthrough for ethical principles?

Certainly, as far as Europe and North

America are concerned. The atrocities which

117

Vko'lC Hsa':^ Forurr. • Volume 16 • 1995

\

(

Forum Interview

were committed shook our consciences. The

Nuremberg trials and the code which was

developed on this occasion with the involve

ment of the medical profession are an

1

VJe should not forget that in our everyday

lives we all have ethical choices — between

what is good and what is wrong.

cxtremelv important milestone. The Nurem

berg Code is the origin of informed consent

and is based on the ethical principle of auton

omy At first it was related only to experi

mental research on human subjects and now,

as vou know, it is integrated into medical

practice. But there is no doubt that this is a

product of our culture: informed consent is

not always applicable in other circumstances.

For example, in Africa a patient expects the

doctor to decide for him, and in Japan the

patient may not be told the results of investigallons or the diagnosis.

Can you explain the origin of the word bioethics ?

Although at CIONS wc arc resisting the

tendency to create new words, bioethics does

seem to have become a generally accepted

term. It was coined in the early 1960s in the

USA when there were many more people

with renal failure than dialysis machines avail

able, so doctors were obliged to take difficult

decisions about allocating treatment. Thus,

bioethics was introduced as a response to the

tremendous scientific and technological devel

opments which created hew situations for

(doctors with regard to their patients.

And health-policy ethics?

Health-policy ethics may be seen as an aspect

of bioethics concerned particularly with the

organization, financing and delivery o ea t

care; it is a concept developed by C1OMS

within the framework of its International

Dialogue on Health Policy, Ethics and Human

Values. Let me tell you how this came about.

In 1983 and 1984 the World Health Assemble

debated whether a spiritual dimension should

be introduced into all health programmes

coordinated bv WHO. There was much dis

cussion involving politics and religion so that

the issues became blurred. 1 discussed it after

wards with Dr Halfdan Mahler, who was at

that time Director-General of WHO, and

suggested that CIONS could take up the sub

ject This was the origin of our programme

of health policy, ethics and human values.

Professor Jack Bry ant was a key collaborator

in initiating dialogue on this programme

internationally.

Nowadays there is a lot of talk about training in

ethics. Looking back to my days in medical school

I remember we were just supposed to imitate the

way our professors and other doctors behaved.

Is it necessary to have special courses?

Several years ago UNESCO and V HO

studied how ethics was being taught in medi

cal schools: it was generally not obligatory in

Europe, more widespread in the USA, and

the developing countries usually followed the

European lead. 1 believe we should sensitize

the students - our future physicians - to all

ethical issues. Many medical schools teach

ethics in an integrated way as cases arise, and

the professors are sensitive to the need to

identify the related ethical question in clinical

situations.

I think that's how we learned but we didn’t know

it was ethics!

Exactly, and that is the best way to teach the

principles, without calling it ethics. The word

itself creates mystery, being heavy with emo

tional overtones. We should not forget that in

our everyday lives we all have ethical choices

— between what is good and what is wrong.

World Health Forum • Volume 16 • 1995

116

<

t

Ethics and health

Human rights and ethics^

fligion, political belief,

Organization, 1946)

-Eveo.o„e ba. .be ngb. ,o a

of himself and of his family, including

,

of uncmploymcnt, sick35X3. old age » o.be. lack of l.volibood in eireunnUnee. beyond

(A„"e"e'2°'j.em 1,

J Deefarenon «f

IMS)

•The Deel.ra.ion of Geneva of .be World

“E^itTrn^

-All research rnvolving human subieers should be condoned in accordance w,.b .hree

CIOMS, 1993)

Ethics is directly related to our behaviour, and

much more should be done to demystify it.

You once said that WHO had introduced a new

principle in health ethics - the equity principle or the

health-for-all strategy, which resulted from the 1978

Alma-Ata Conference. Could you explain its import■ ance?

that health for all is recognized worldwide

and has tremendous influence in both devel

oped and developing countries shows in my

opinion, the exceptional value of the World

Health Organization from an ethical point oi

\new.

Would you say that equity is a major target in health

(

development?

In the revolutionary health-for-all concept,

“air means all human beings. This statement

of equity has a ver}' strong ethical value

behind it: the justice of distribution - mat.is,

health services seen as something good which

should be distributed to everyone. The tact

Certainly on the global level, because it deals

with mankind as a whole. The global

approach for everyone’s benefit is veiy

important, and WHO’s promotion of health

for all has very' strong ethical connotations.

119

• Voljw 16 • 199-

Forvm Interview

L

it

P

I

t

c

s

policy-miking will therefore vary from country to country.

TheCIOMSprogramme^rfonJ cor^er^ce lheld in

1OgUC

o^eS'eS to discuss in an international and intercultural context the ethtcal

Zb raised by health policy-making and policy dectsions.

The

of a na-n or a community isiu

social uses of the availableimed.ca

guides for people when choosmg goal ,T^on

. .

I

c

c

2

that strategy. Etl^ is the link

of the cho; that muSt

I

I

A

5

choices in accordance with accepted norms.

I

A strong recommendation of the At^^^^"CehrionshipabXeen health policy-making.

(

1

1

I

j

i

values across cultural and political lines.

The main means for implementing thh>

national, intercultural conferences with a g

nf intercogences, not

interaction of health policy-making,

WoiJd Health Forum • Volume 16 • 1995

/A-

A

Ethics and health

Do you think that all health ministries now think

in terms of equity when they analyse problems and

prepare their interventions?

It is difficult for me to know this, but it seems

there are wo aspects. One is the development

of guiding principles such as the health-ior-all

strategy-. The other is its implementation.

Policy decision-makers in many countries are

certainly moving in the direction of extending

services to those who have only limited or no

access to existing services. It is obvious y verydifficult to provide health services to all

human beings in the world, and the aims will

vary according to what is feasible and neces

sary for different countries or societies. For

me it is important to sec WHO, as a UN

specialized agency, working steadily to intro

duce equitable policies, following ethical and

moral principles which arc universally recog

nized. This is something which must not be

forgotten.

How do you see WHO's role in the ongoing

development of health ethics?

First of all I think it is important to continue

what was started, namely, to continue to pro

mote health for all - this is a unique role for

^TIO. The Organization is well placed to

convince politicians and to stimulate the politi

cal wdll for translating this commitment into

action. In my opinion WHO is doing this

ver}’ well because there are continually new

developments in global thinking in this field.

Another area is local action. “Think globally,

act. locallyn was the slogan of World Health

Da}’ in 1990 about the environment; I have it

displayed in my office as a reminder of the

importance of different levels in discussion.

Global thinking is health for all; local action

depends on local circumstances, and must be

adapted not only to varying economic,

financial, historical and traditional situations

but also to moral and ethical circumstances.

We are always urging that moral and ethical

aspects should be taken into consideration in

health policy-making, not just in order to

prevent abuses but because wc know from

The fact that health for all is recognized

worldwide and has tremendous influence in

both developed and developing countries

shows the exceptional value ol the World

Health Organization from an ethical point of

view.

experience that some apparently excellent

programmes were not implemented because

society rejected them for moral or ethical

reasons. It is important to discover whv and

try to find another way of presenting the

proposals or make alternative ones. Cultural

differences are central in international work:

we should always keep in mind that people

are different and we must endeavour to

understand them.

I believe CIOMS, with WHO’s cooperation, has

recently evolved a global agenda for bioethics?

Yes, CIOMS s long-term programme on

health policy, ethics and human values

culminated in a conference held at Ixtapa,

Mexico, in April 1994 on “Poverty, Vulner

ability, the Value of Human Life and the

Emergence of Bioethics . The participants

requested CIOMS to draft a declaration on a

global agenda for bioethics for adoption by

the conference (see pages 123-124). Partici

pants in the conference believed the time was

ripe for the establishment of a global agenda

for bioethics, and the Declaration of Ixtapa

constitutes a first step in that direction. The

world needs the moral affirmation and ethical

guidance that such an agenda can bring to the

health sector in all countries, and the partici

pants at Ixtapa and CIOMS welcomed WHO s

role as leader in the pursuit of such a goal.

121

Wo'ld Health Forum • Volume 16 • 1995

Forum Interview

Has the AIDS epidemic influenced the whole debate

on ethics?

No doubt about it. The AIDS epidemic is

stimulating everybody to do as much as pos

sible to sec that ethical values arc respected.

\Xrith a disease for which no adequate treat

ment exists, a diagnosis can be a death

sentence for the patient. It was previously so

with cancer. Now AIDS patients arc in the

same tragic situation. Top politicians arc

aware of the effects of this social problem and

arc looking for solutions which will be as

cthicallv valid in the USA as in Africa. Such

common ground is not easy to find.

Scientific progress in medicine and new devel

opments in therapy and diagnosis will most

likclv continue in the so-called “developed’

countries in Europe and elsewhere; but will

these advances be applicable to the people liv

ing in the developing part of the world - more

than 80% of our population? Often what is

affordable by cenain countries may not suit

others. Take drug treatment for HIV/AIDS

patients, for example. CIOMS was requested

by the Global AIDS Programme to develop

ethical guidelines relevant to the AIDS situ

ation on a global basis. In order to develop the

proper treatment and prevention strategies for

AIDS you need to study the target popu

lations, collect epidemiological information,

and test potential vaccines and drugs. Intercultural differences may mean that

Cultural differences are central in inter

national wort: we should always keep in

. mind that people are different and we must

. endeavour to understand them.

approaches developed in Europe or North

America are not easily acceptable in other

countries, sometimes for political reasons, yet

everything must be done according to ethical

principles.

122

In CIOMS in 1985 wc saw that two aspects

had to be addressed. The first was the formu

lation of ethical guidelines for epidemiological

study: this is when you identify the problem

and how the disease spreads, which is essen

tial basic information. The second was con

cerning research involving human subjects:

experimental vaccine testing, for example. The

U.S. authorities were particularly keen for

CIOMS to develop guidelines which would

be internationally recognized. These two sets

of CIOMS guidelines have been translated

into manv other languages and arc now

widely used (2,3).

I am concerned that although universal rights have

been formulated, less attention is paid to universal

responsibilities

It is true that if you say somebody has rights,

then they also have responsibilities. These

have not been defined up to now, but perhaps

sets of responsibilities of human beings as a

social group should be developed. Certainly

many people are concerned by what is really

needed now for mankind. Fifty years ago the

development of human rights was first priority. That was followed by the rights of differ

ent categories of society - patients, women,

children, etc. - which are good but, at the

same time, there must also be responsibility;

The constitution of many countries specifies

its citizens’ rights and also their responsibil

ities. In my opinion, this practice should be

followed internationally.

Because of social obligations?

Exactl}’. This is the social aspect of ethics: it is

about relations with other people. There is

nowadays a strong trend to look at everything

from the ethical point of view because

increased mass media exposure brings us all

closer to each other. Previously individuals

just considered their families, then their

villages, and then their countries, but now we

V>:'2 Hea'^ Forum • Volume 16 • 1995

Worlc

Ethics and health

t global igenda to' bloMUs:

. Bionics in .ho heahh

”lhe Declantlm el IMP"

shonld lx gnkM by .he following goner* accepted

hoe! of ho* ..e ,Mf lx =

' Q KX”»' i-1-1’ <o'Jl “ '"d““d ” ,l’c Dic,“ °

&htenfeeS.hoUldbeo«ocb«,effxient.CeeSSibk,.ffo.d«M^

and individuals s

. yhTXeipio. of

»

^Ta?^

XXXXSXXXX bo appiied across ah ^re,

. Effort should be made .o pronro.e and ^^“X^Xerging

national and international capacities for

•

^sterns may be practised that threaten

SKik ■he p™* of equity * non-discrindnaonx

. Efforts should be made .o devebp

"5 ”?eXXXS“K»ndemu»d.»gof d,e causes »d eireumsunces of

principles, acknowledging t

biXd^

bilateral and multilateral links between

their counterparts in developing countries.

(continued overleaf)

____________

123

VMd Health Four • Volume 16 • 1996

Forum Interview

t HIM WM lorbioMIcs: SWW blU» Declbrbl'bb bllOBDb (cohlmbb)

t

i

1

Human rights bodies

Such rights can be divided

I

1

l

into the foDowing categories:

1

I

<

_ gnceE"’

concerned with liberry, secunty, and private life.

,nd‘“lme nsl"s

i

Development banks

health, environment, poverty, and education.

i

Internationa! organizations

. Intergovernmental organizations engaged

tion to bioethical issues in

^]veinent of all concerned, including scientific

Emphasis needs to be placed on the full mvo vemento^

of

and lay organizations, in discusswns o

hou]d be sensitized to pressing

■ESSSS.s===sssxsst.

particularly in developing countries.

Source: BuUem of the World Health Organization, 1994,72:998-999.

■World Health Forum • Volume 16 • 1995

12*

Ethics and health

are all aware of what is happening all over

,hc world. And so ethics is now a main issue

in political debate. The aim of CIONS in the

10 years of its health policy, ethics and human

values programme was to sensitize health

nolicv-makers to the ethical issues. 1 he

I Jirector-General of WHO is convinced of

the imponance of ethics, and now some

Member States are saying that VTdO should

be more involved in this field and that its role

should be established at the highest level. To

me it is a measure of progress that we arc ab c

to bring health policy-makers from different

countries together to d.scuss eth.cal tssues for

a frank exchange of views.

WHO certainly has moral authority.

\cs and that raises an interesting point: the

moral authorin- comes from the fact that

.

as a public-health-oriented orgamzation, is devoted to helping the public at large,

which is an extremely ethical role. People

sometimes ask me why ethical issues need to

be discussed at all, because WHO’s role in

helping poor countries is by definition ethica .

This is certainly true, and because of its moral

authority the role of WHO in promoting dia-

If you say somebody has rights, then they

also have responsibilities.

loguc on the global agenda for bioethics is

crucial. The importance of intercultural

debate among like-minded people cannot be

emphasized enough. Dialogue, and yet more

dialogue, is the way forvs ard. ■

References

1 Mooney G. Conflicting ethics m health care World

heallh foru'T- 1987.8 516-517

Ethics and epidemiology international guidelines

Geneva CIOMS. 1991

3 International ethical guidelines for piomedica.'

research involving human subjects. Geneva. CIOMb

1993

125

Foru'r' • VolU^lC • 1995

L2

Point of View

1

Graham Evans

Health and security

in the global village

With the ecological stability of the world under threat, no country can

stand alone National security should no longer be viewed in a purely

military light but rather as a matter demanding cooperation between all

countries on a broad range of vital issues, not least those related to

health and the environment

Even political system has, or claims to

have, a final arbiter, namely a government,

which settles disputes and allocates

resources; this is the defining characteristic

of politics within the state. In international

politics, however, there is no single

government to regularize relationships

between the panicipating states.

Consequently, the concepts of self-help and

self-defence enjoy a much more legitimate

status than they do within the state; and

power becomes the ultimate arbiter.

Health care: in whose interest?

Formerly, health care was only a peripheral

matter among the concerns of politicians.

The author is Lecturer in International Relations,

Department of Political Theory and Government,

University of Wales, Swansea SA2 8PP, Wales

4ea

Fo’d-n

VO

14

1993

During the nineteenth century it was

introduced not for humanitarian reasons but

because industrialists realized that healthy

workers were more cost-effective than

unhealthy ones.

In general, health was considered important

only to the extent that it touched on matters

of national importance. In domestic politics,

health care provision became a function of a

particular ideological orientation and its

ability to impact on the political process,

whereas in world politics it has always been

intimately associated with the fabric of

security challenges to the state. In both

contexts, the spur was provided by

pragmatism, not idealism.

The issue of global health, like that of the

environment, has become more prominent

on the political stage as the dictates of

interdependence among states have imposed

themselves.

133

]

I

7

I

Point of View

Health practitioners and political scientists

now basically agree on the desirability of

removing inequities in health care,

particularlv in the context of North South

relations. S'et unless the questions of health

begin to impinge directly on states'

on a solid economic base. Security has thus

been regarded as an end-product of a

particular kind of policy-making, usually

involving arms races.

Security: the broad view

The health-for-all goals are bound

to remain beyond reach until

political will has been summoned

up, especially in the developed

countries.

conceptions of national interests, particularly

security, they arc likely to remain

unresolved. The health-for-all goals arc

bound to remain beyond reach until political

will has been summoned up, especially in

the developed countries. Success is only

likely to come if there is a clear recognition

that the security and prosperity of the

developed world arc at stake.

On its own, moralistic pressure cannot

be expected to bring about a transfer of

resources from the military to the health

sector. Even the so-called peace dividend

that many people expected after recent

events in eastern Europe and the former

Soviet Union has failed to materialize.

The potential dangers perceived by states

militate against change in this direction.

Yet expenditure on health care should now

be seen as a contribution to security rather

than as an alternative to it.

Security has always been the central element

. in international affairs, and the principal

instruments for achieving it have been

military and diplomatic. The ability to resist,

deter or overcome an opponent has

depended on visible military capability built

134

In the world of the 1990s, however, security

is no longer just an end-product resulting

from a perceived capacity for retaliation but

is a process reflecting a much wider view of

threat than that traditionally recognized by

governments of nation states.

Of course, the nuclear menace still exists,

but if we shift our focus from states to

peoples and from independence to

interdependence the nature ol the security

issue begins to look diflerent. People

cvervwhere face mam hazards, among them

AIDS, drugs, pollution, starvation,

population growth and environmental

degradation, which fail to appear in

traditional analyses. Military power has not

become unimportant, but its dominance at

the centre of things has been challenged.

Nature does not recognize international

boundaries, and the emphasis now is on the

connectedness and interdependence of

things. Thus, parallelling developments in

social medicine, the new strategic approach

is to embrace the whole picture rather than

isolated parts.

Security , as defined in 1982 by the Palme

Commission on Disarmament and Security,

requires physical and ecdiibmft well-being,

human rights, civil and political liberties,

a sustainable environment, and a programme

of social justice seeking the transfer of

resources from the North to the South. In

the field of strategic or peace studies, threat

assessment exercises, which previouslyfocused primarily on economic and military

capability, now also cover the larger

ecological and environmental dangers that

V.o'Id

Vo

14

1993

\

INDIAN SOCIETY OF HEALTH ADMINISTRATORS, (ISHA), BANGALORE

in Collaboration with

NATIONAL LAW SCHOOL OF INDIA UNIVERSITY, BANGALORE

One Day Meeting on RIGHT TO HEALTH - March 15, 1997

Venue: Committee Room:Di rector’s Office Building, NIMHANS

Health for All and the National Health Programmes: Major Issues

I.

Issues identified in National Health Policy for HFA.

Status of the population (around 1983).

Hea7 th

1 .

The high rate of population growth continues to have an

adverse effect on the health of our people and quality of their

lives.

Mortality rates for women and children below the age of five

2.

years, are very high.

3.

High infant mortality, around 129 per 100 live births.

4.

Extent and severity of malnutrition continuing to be high.

5.

Communicable diseases yet to be effectively brought

leprosy, TB continuing to show high incidence.

control

6.

under

Blindness continuing to show high incidence.

Only 31% of rural population had access to potable water

7.

supply and 0.5% to basic sanitation.

8.

High incidence of diarrhoeal disease, other preventive and

infectious diseases specially among infants and children, lack of

safe drinking water, poor environmental sanitation, poverty and

ignorance are among the major contributory causes of high

incidence of diseases and mortality.

II.

Health Systems and Manpower issues.

1.

The existing situation has been largely engendered by the

almost wholesale adopting of health manpower development policies

and establishment of curative centres based on western models,

which are appropriate and irrelevant to the real needs of our

people and the socio-economic conditions in the country.

2.

The hospitais-based disease and cure-oriented approach

towards establishment of medical services, had provided benefits

to the upper crusts of society, specially those residing in the

urban areas, at tho cost of providing comprehensive primary

health care services to the entire population whether residing in

urban or rural areas.

1

3.

High emphasis on curative approach has led to neglect of the

preventive, promotive, public health, and rehabilitative aspects

of health care.

4.

Instead of improving awareness and building up selfreliance, the existing approach has tended to enhance dependency

and weaken the community capacity to cope with problems.

5.

Prevailing policies in education and training of medical and

health personnel have resulted in a cultural gap between the

people and personnel providing care.

6.

The various health programmes have failed to involve

individuals and families in establishing a self-reliant .

community. This is in view of the fact that the ultimate goal of

achieving a satisfactory health status for all our people cannot

be secured without involving the community in identification of

health needs and priorities and in implementation of the national

health programmes.

III. Medical Education

Keeping in view the above issues, the National Health Policy

called for the:

i.

Review of the entire basis and approach towards medical

education in the light of national needs and

priorities, and a restructuring to produce personnel of

required professional and social skills and competence,

motivated to achieve results, within existing

constraints.

ii.

A National Medical Education Policy which

a.

sets out changes in curricular contents and

training programme of medical and health personnel

at all levels.

b.

Takes into account the need for establishing the

extremely essential inter-re 1 ations between

functionaries of various grades.

c.

pro v1des guidelines for production of health

personnel on the basis of realistically assessed

manpower requirements.

d.

seeks to resolve existing sharp

imbalances in their availability.

e.

ensures that personnel at all levels are socially

motivated towards the rendering of community

health services.

i

2

regional

Immediate Priorities

IV.

The National Health Policy identified the following priority

areas to be urgently attended to:

i.

Nutrition; Raising the nutritional level of al 1

segments of population, on a time-bound bases, using

every possible strategy.

ii.

Prevention of food

quality of drugs.

adulterati on

and

mai ntenance

of

provision of facilities

i i i. Water supply and sanitation

together with health education for effective use

towards health and sustainability.

iv.

Environmental protection

v.

Immunization Programme

of target population.

vi .

Maternal and Child Health Services: to provide and

ensure utilization of all necessary preventive and

promotive services nearest to the door-steps of the

people, particularly anti-natal, intra-natal and post

natal care.

achieve cent-percent coverage

vii. School Health Programme to reach al 1

chi 1dren.

school

going

viii. Occupational Health Services to ensure outreach of

services to prevent and treat occupational hazards not

only in organized but also unorganized sector such as

agriculture.

i

ix.

Health Education: Vital for success of every scheme and

programme.

x.

Management information system for appropriate decision

making and programme planning.

xi.

Medical Industry - to ensure adequate availability of

life-saving and essential drugs and vaccines produced

within the ^country at affordable prices even for the

poor, using available technological and manufacturing

capability. *To bcvw

vaa cAxA/oy*

-to i'y^vXjz.

X i i. Health Insurance: to enable health for all, in all the

above dimensions to become an affordable proposition.

xiii. Health legislation

xiv. Medical research: with the basic objective of

transition of available know-how into, simple, low

cost, easily applicable, acceptable, appropr i ate

3

t

technologies, devices and interventions to suit 1 ocal

condition. thus placing the latest technological

achievements within the reach of health personnel,, even

in the remotest corners of the country, particularly

|

with regard to

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

xv.

Contraception

' Bli ndness

Leprosy

Tuberculosis

Other communicable diseases

Inter-sectoral co-operation for health

xvi. Monitoring and Review of Progress

In the light of the National Health Policy, the Fami1y

Welfare and Communicable Disease Control Programmes, were sought

to be strengthened, and additional Programmes were act i ve1y

initiated, prominent ones being the Nutrition-related programmes

for women and

children, Anemia

prophylaxis programme and Vitamin

t

A distribution, Immunization Programme,

Programme, National Blindness

Control Programme, and National Goitre Control Programme.

All

these programmes, specifically the Mother and Child Health

Programmes, Family Welfare Programme received a major boost in

made, However,

the decade 1983-93 with significant achievements made.

some- of the programmes such as Malaria Control Programme, T B

Control lagged behind the newer priority programmes.

Subsequently, however, following initiation of the national

reforms and restructuring process and other complex developments,

some of the major issues facing public health and family welfare

in India, affecting the implementation of all the Programmes are

as follows;

Reductions in outlays for health and social sectors (in real

1 .

terms)

2.

Reduced emphasis on health and social sector by the

government (as compared with industrial and other economic growth

sectors)

Inadequate recruitment of personnel at all levels in the

3.

health, system by all State Governments on the plea of financial

tightness.

Specifrca 1 1 y , gross inadequacy of male health

workers, lab technicians at PHCs, health supervisors, male and

female, and health educators is evident. Inadequacy is not merely

due to increased population; large number of vacancies caused by

retirement are not being filled. Almost every public health

programme depends on these critical front-line workers.

4.

In all States, the system of having Medical Officers of PHCs

as the leaders of the health team has, by and large, failed in

achieving community health objectives, with MOs largely confined

to a curative role at the PHCs/HCs. Resultantly, the paramedical

4

workers are unable to look to a leader for technical,

supervisory, and motivational guidance.

gu i dance.

In the present

framework, in every public health programme,

programme, the leadership of

the PHC/MO is critical for effective implementation.

5.

The issue of whether to have a non-medical leadership for

all non-curative/non-surgical aspects of public health and Family

Welfare Programmes, needs to be examined.

It had been suggested

in the late eighties, to have non-medical Community Health

Officers, as officers in- charge of the PHCs and Community Health

Centres, responsible for providing technical and administrative

leadership to all the public health programme manpower, and

getting the curative/surgical assistance of the medical doctors.

V.

Critical National Health Programmes

A.

NATIONAL MALARIA ERADICATION PROGRAMME

i

The NMEP in India after

a spectacular success during the

period 1958-65, due to a combination of setbacks showed a major

resurgence with its peak in 1976.

The annual incidence of cases

and deaths were reducedI from about 75 million cases and one

million deaths prior to 1958, to 0.1 million cases and no death

in 1965, and again with resurgence increased to 6.47 million

cases in 1976. Since then, with modification of strategies, and

fluctuating inputs for implementation of the NMEP, malaria has

•become chronically endemic in India, with epidemics from time to

time in certain pockets. The major problems and issues for

effective malaria control are;

Admi ni strati ve

1.

Low priority given to the Programme by the Health

administrators at National and State levels, specifically in the

contexts of: a) Low priority to health as such , and, b)

Increasing priority to MCH and Family Welfare, AIDS etc.

2.

Gross inadequacy of field personnel

control activities timely, which is the

programme.

to carry out malaria

key to sucess of the

Technical

a.

Mosquito Resistance to Conventional

insecticides.

3.

Relative mosquito resistance to conventional i nsecti ci des

(currently DDT is the only one implicated since it has been

widely used). Resistance would emerge equally rapidly to other

insecticides also.

b.

Emergence of Drug resistant malaria parasite strains

4.

Haphazard, indiscriminate use of anti-ma 1 aria 1s by the

public, private practitioners, etc, has resulted in emergence of

malaria parasite strains resistant to conventional drugs.

Agai n

5

this is due to inadequacy of systematic malaria

treatment activities by the Government machinery.

c.

control

and

Community Participation in the Programme

Since malaria prevention is closely linked to lifestyle and

5.

peop1e’s action, community participation is critical for i ts

success. So far the Health officials at all levels, have been

1 east geared to mobilize community participation for success of

the Programmes.

d.

Lack of follow-up on alternative strategies such as

insectici de-impregnated mosquito bednets

6.

Inspite of promising results with field trials of

insecticide-impregnated mosquito bednets, there has been no

follow-up to assess its potential on a large scale and implement

the same.

e.

Leadership to the Programme at PHC and District level

Effective committed leadership at PHC and District 1 eve 1s,

is critical for malaria control, These two aspects have been the

weak links in NMEP.

Among the above issues, the most critical ones are ;

B.

a.

Gross inadequacy of paramedical and field health staff,

specifically lab technicians and male health workers.

b.

Leadership factors at PHC and District levels.

NATIONAL TUBERCULOSIS CONTROL PROGRAMME (NTCP)

This programme, which did not gain due priority so far, has

become critical due to emergence of HIV infection and AIDS, The

critical issues facing the TB control programme are;

TB is a silent killer

Being a chronic disease it does not cause epidemic cases or

1 .

deaths. Hence it does not catch the attention of the media and

administrators, consequently very low priority to this programme.

A major, shift in strategy

2.

There has been a major shift in the strategy of India’s TB

programme, under the aegis of international agencies, just when a

widespread awareness of the strategies of the original NTCP had

gained momentum. Worldwide, there have been major changes in

perceptions about TB treatment, particularly in the context of

the developed countries’ response to the HIV-TB linkage. As a

result, together with considerable World Bank funding for TB

Control, there has been a statergic shift, from domiciliary, self

administered treatment, to DOTS - a system of supervised

6

contact. Although i ts

chemotherapy by person to person contact.

was

not

studied,

it gained wide

effectiveness in

i n India

strategy

inabandoning

the

former

resulting

acceptance,

effectiveness

and

cost

benefits

DOTS has

a 1 together . Lately, the c . .

~ -----------been called into question by series of studies.

b.

Problem of Diagnosis at periphery

2.

Diagnosis at the periphery requiires sputum examination by

of being “dirty",

microscopy. Culturally sputum has a connotation

c~.

Besides

traditionally,

doctors

compared with blood examination.

.

are inot oriented

-. ----- to diagnosis of TB by simple sputum examination.

c.

Problem of prolonged treatment

3.

Due to need for prolonged treatment, patients tend to

d i sconti nue treatment or take irregular treatment, a situation

which is worsened by poor treatment organization at the

per iphery.

d.

Effective Drugs not available under in the TB programme

4.

Even though highly effective drugs for treatment are

a v a i 1 a b 1 e , they have not been utilized or misused due to cost and

other factors. For a long time, the available drugs under the

programme were of low effectiveness, and required very long of

treatment, which demoralised the patient and the staff. Since the

last eight years, availability of any type of anti-TB drug has

been very poor, particularly under the Programme. This has led to

a through demoralization of staff who are expected to diagnose

cases without the means to treat. Patients are demoralized due to

inability to afford on their own, and lack of drugs in the Govt,

setup.

Lack of effective and continued leadership to this programme

5.

at District Level.

The organization of TB Programme requires effective,

committed leadership and continuity of leadership at the District

level which is a weak link in the system.

Lack of clarity on the epidemiological linkages between HIV

6.

and TB

C.

HIV AND AIDS CONTROL PROGRAMME

HIV - AIDS poses a serious threat to the health of our

country, with serious implications for physical, mental, social

and economic health. The National AIDS Control Organization, WHO

and other agencies have estimated that about 30-40 lakh Indians

are currently HIV positive, which may increase to about one crore

(10 million or 1% of the population) in 2001.

The major issues

are as follows:

related to HIV-AIDS control and management

1 .

Inspite of widespread HIV-AIDS awareness large number of

people of' all social strata are still getting infected.

This raises questions regarding the outreach, i ntens i ty,

content, and nature of the AIDS educational programmes, vi sa-vis their effectiveness.

2.

The issues of stigma and fear related to HIV and AIDS are

causing serious constraints in containing the spread of

disease and in enabling HIV affected individuals and

families adapt to the problem, These issues have not been

tackled in the educational effort.

*2*

By the year 2000 approximately 10 lakh individuals will need

AIDS related inpatient, care. But the total bed capacity in

the Government sector is about six lakhs. A planned approach

to the problem of care; of HIV related illness, is critical,

considering the magnitude of the problem.

D.

FAMILY WELFARE PROGRAMME

a.

Political Commitment

The most critical issue is lack of adequate political

How critical is political

commitment to implement the Programme,

is

evident

from

the tremendous success

commitment for its success

achieved by Tamil Nadu in reducing the birth rate from 31 in 1981

to 24 in 1992, improved from, a ranking of 16th to 3rd in India,

and achieving one of the lowest decadal population growth rates

in India of 21% (next only to Goa and Kerala). All this was

achieved due to political

commitment of successive Chief

Ministers of the State. Family Welfare Programme currently

remains, a women’s Contraception Programme.

1 .

Family planning - perceived as the women’s responsibility

From the top management level of the Programme upto the

2.

peripheral health worker, the basic premise is that family

planning and avoidance of pregnancy/ childbearing, is the need

and responsibility of the womenfolk.

Interventions being

researched, put to field trials, and released for mass

application, are all

methods to be used by women,

and

consequently the massive IEC strategies in operation are also

spreading the message as if Family Welfare means contraception by

women.

Thus a psycho-social climate has been created in India,

that family planning is for the benefit of women and to be

practised by women.

Keeping in view the social psyche, which

treats women as second class beings, the Programme emphasis on

female contraception has created a climate of low priority for

family planning among rural and urban poor population.

This

emphasis has to change. Unless Family Planning is projected as a

need and responsibility of both spouses, as a means to economic

8

development of the family,

conti nue.

b.

the low priority in rural

Delay in mass production and

convenient new contraceptives.

distribution

areas wi11

of safe and

3.

The th ird critical, issue is that safe and convenient

contraception methods recently discovered and cleared for field

use, are not being manufactured in sufficient quantities for not

being distributed through government, PHCs and workers.

Particularly, the newer safe methods such as, Saheli which is

ideal for temporarily contraception by women independent of their

husband’s consent, is neither manufactured in sufficient quantity

nor distributed through Government agencies; similarly also other

contraceptives.

c.

Updating

methods

TEC

to d i ssem i nate

1 atest

safe

cont racept i ve

4.

Fourthly, the IEC strategies and content need to be rapidly

updated, to include the latest developments in contraception

technology (such as Saheli, upgradation of condoms quality in

recent times, etc). The updated IEC content needs to be

communicated down the line upto Health Educator and Health Worker

level, and to the masses through mass media.

5.

Lack of dissemination of scientific and authoritative

ev ide nee concerning safety of newly discovered contraceptive

methods.

Recently engineered contraceptives such as Saheli,

Depoprovera, Nor-plant, Birth Control Vaccine, are proven by

international and national trains to be safe, convenient and

highly advantageous to physical and mental health of women, in

comparison with the risks and burdens of repeat chi 1d-bearing’ and

care. Inspite of clear, scientific evidence available and the

WHOs statements to this effect, GOI and State Governments have

not communicated professionally acceptable (scientific) data to

all their doctors down the line, and to the public at large,

through newspapers, journals of the Ministry, and audio visual

media. As a result, a number of NGOs with hardly any appreciation

of the issues involved, and many with their own hidden agendas,

create adverse publicity for valuable contraceptive methods, thus

virtually throttling .Government’s efforts.

The Governments,

Central and State, should ensure adequate publicity for

scientific information on the benefits, statistically proven

risks as well as precautions, to prevent or neutralise undeserved

adverse publicity.

d.

Lack of IEC emphasis and clarity

temporary contraceptive methods.

on safe and acceptable

IEC efforts, through mass media (TV and radio continue to

emphasize only sterilization operations which are either feared

or rejected by several sections of the population.

Regular IEC

9

on safe and accessible temporary methods which can be practised

by women in their own, is needed, if Family Welfare has to reach

the unreached families so far.

e.

Ensure Availability of contraceptives right upto village

level

6.

There is need to ensure availability of safe and acceptable

contraceptives right upto PHC and health worker level,

appropriately trained to handle the same.

In case of orally

self-administered ones, products like Saheli could be socially

marketed through fair price shops other village shops, bang 1e

sellers in rural areas, and other innovative woman to woman

approaches.

The effort for wide spread availability of all types of

convenient contraceptive methods for rural population, should go

hand in hand with IEC effort.

7.

Need to promote vasectomy to dispel myths, popularize

noscalpel vasectomy, and train adequate doctors in the

procedure

Tubectomy, being an intra-abdominal operation carries far

women, as well as chronic pain and other

risk to health of women,

debilitating complications

comp 1i cat ione for women, causing many women to

hesitate or refuse.

refuse. Vasectomy, which is now modified to a

subcutaneous and safe procedure, should be effectively promoted

and doctors right upto peripheral level trained in the procedure.

more

8.

Need for people-friendly

and follow-up services

Family

Programme

pre-operati ve

The entire family welfare machinery needs to be geared up

for an integrated people-friendly approach in providing Family

Welfare services. This implies adequate prenatal care/preoperative care to correct anemias, make the person fit for

surgery, and post-operative follow-up care for complications.

For effective implementation, these aspects should be monitored

as part of the PHC/District/State Family Welfare performance.

9.

Role of Financial Incentives in Promotion of Sterilizations

Inspite of a number of studies and expert opinions that

incentives are not critical factors in accepting Family Planning,

ISHA’s interactions with eligible couples show that stoppage of

financial incentives for sterilization in some States has been a

• major barrier to Family Welfare Programme in recent years.

Our

interactions in Maharashtra State show that rural women

undergoing tubectomy are now compelled to go for work to the

fields the very day following tubectomy, for economic reasons,

thereby going in for life-long abdominal pain and other

complications.

Thus the image of tubectomy and Family We 1 fare

Programme itself has been tarnished.

10

It needs to be understood that financial incentive is not

the primary factor to induce acceptance of sterilization, but

lack of financial compensation would seriously retard the

programme. Though it is termed as "incentive” in Family Welfare

jargon, in reality it is the compensation for loss of daily

wages.

This is essential for the family food during the period

when the mother has to take rest.

There is urgent need to review the decision on "incentive”,

and to fix a compensation level equal to wages for the period of

rest required.

To avoid misuse of cash by family members,

equivalent in grain and essential commodities could be provided

for.

10.

Target setting and Family Welfare monitoring to be refined

to included the dimension of parity of acceptors.

Decade after decade, planners and experts are emphasizing

the need for quality of target achievements, and not merely

quantity. Since sterilization needs to be accepted after two, or

maximum three children, to achieve a demographic impact.

Mere

target achievement by doing sterilization of couples with four or

more children, does very little for demographic change. Therefore

targets fixed should be linked to parity of acceptors. Similarly

also, monitoring and corrective actions should take into

consideration parity of acceptors.

11

INDIAN SOCIETY OF HEALTH ADMINISTRATORS, (ISHA), BANGALORE

HEALTH FOR ALL: SOME RECOMMENDATIONS TO ACHIEVE THE GOAL

The Indian Society of Health Administrators, chose the theme

of Health for All by 2000 AD for its first annual conference in

1980. Recommendations were made. r

We need' to review how far these

recommendations have been implemented at

- various

.

--- ; 1 eve 1 s .

1 .

The present allocation of financial resources for the health

system being inadequate in absolute and relative terms and in

comparison with other countries, the conference recommended that

1.

The allocation both by the centre

increased substantially forthwith.

ii .

Studies be

I

undertaken to determine the

the optimum

increase, taking into consideration, the

the economic

situationi of the country and the possibilities of

and the states

be

mobilizing funds for health efforts.

2.

Given the fact that the financial resources (inspite

larger mobilization of funds) will continue to be inadequate

the foreseeable future, recommended that

of

in

i.

there should be intensive training programmes for

health personnel at all levels in order to equip them

with

modern

management

techniques

for

better

utilization of funds, and

i i.

priorities must Ibe assigned in the distribution of

funds for those programmes which are more cost

effective in bringing about better health to larger

sections of the people, viz., health education,

nutrition, immunization

immuni zation programmes, eradication and

control programmes and water supply and sanitation.

2

As the country is still lagging behind in the matter

of

production, distribution and proper utilization of drugs

and

pharmaceuticals to ensure the availability of essential drugs at

feasible costs,

recommended that the country identifies low cost effective

drugs essential for primary health care, produces them in bulk

quantities and Iensures proper distribution (with distribution

systems at the periphery)

4.

FFree supply of drugs and services being neither feasible

nor

desi rable,

recommended that the beneficiaries

according to their capacity to pay.

12

be charged for

them,

5.

The judicious development of appropriate

respect to types and numbers being imperative,

manpower

wi th

recommended that steps to be taken to train

i.

one community health volunteer for 1000 population or

for each village, where the population is less than

1000.

ii .

village level worker, as needed depending on the 1 oca 1

conditions, and

iii. other identified health personnel such as multi-purpose

workers, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dentists,

laboratory technicians and health inspectors, as per

the recommendations of the committees which have

considered these needs.

Since school teacher form a large body of persons who can

6.

influence the young minds for better health,

recommended that

i.

school teachers be given training in health education,

covering all school teachers by 1990.

ii .

the syllabus for training of school teachers (B.Ed, B T

and other similar courses) should have the theory and

practice of health education, and

iii . The school curriculum for the age groups 10 to 15 years

should include "Health Education in effective manner".

7.

Health being multisectoral and there is

coordination of all programmes of primary health care,

need

for

recommended that the departments of health at the center and

the States should coordinate the activities of all implementing

departments, such as Industry, Agriculture, Education and Health.

Community participation is essential if primary health care

8.

is to succeed. To ensure the involvement of the community at all

stages of planning, implementation and evaluation,

recommended that health committees

i.

be formed at various levels (Village, Block, district,

State and linked to the National Development Council);

ii.

should include elected representatives of

and various health functionaries, and

13

the

people

iii. at the village and block levels, they should include

local practitioners of medicine, school teachers,

representatives of women’s organizations and leaders of

the local community.

91Voluntary agencies have an important role to play in primary

health care and in order to ensure their participation,

recommended that

i .

voluntary agencies

their efforts;

ii.

they be involved in health activities