NATIONAL HEALTH POLICY - 2001

Item

- Title

- NATIONAL HEALTH POLICY - 2001

- extracted text

-

RF_HP_2_B_SUDHA

4

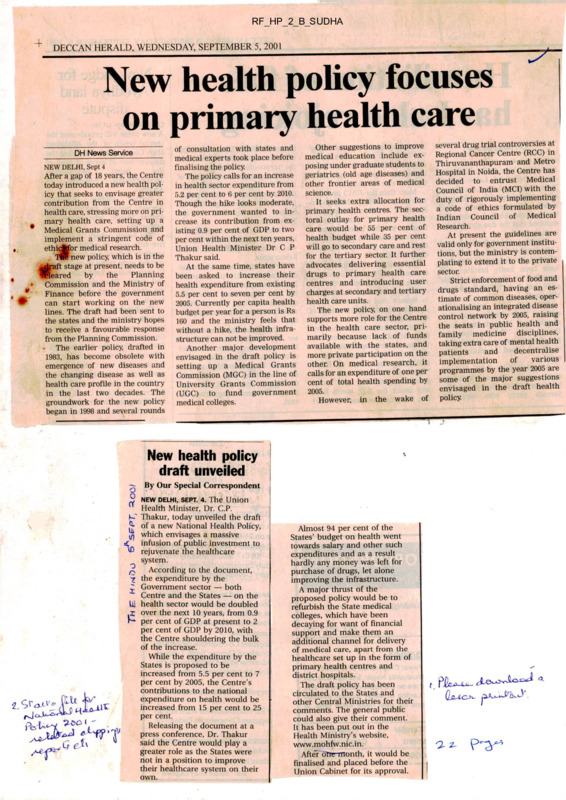

DECCAN HERALD, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2001

New health policy focuses

on primary health care

DH News Service

NEW DELHI, Sept 4

After a gap of 18 years, the Centre

today introduced a new health pol

icy that seeks to envisage greater

contribution from the Centre in

health care, stressing more on pri

mary health care, setting up a

* Medical Grants Commission and

implement a stringent code of

ethidfefor medical research.

TW-new policy, which is in the

^iraft stage at present, needs to be

Weared

by

the

Planning

Commission and the Ministry of

Finance before the government

can start working on the new

lines. The draft had been sent to

the states and the ministry hopes

to receive a favourable response

from the Planning Commission.

The earlier policy, drafted in

1983, has become obsolete with

emergence of new diseases and

the changing disease as well as

health care profile in the country

in the last two decades. The

groundwork for the new policy

began in 1998 and several rounds

of consultation with states and

medical experts took place before

finalising the policy.

The policy calls for an increase

in health sector expenditure from

5.2 per cent to 6 per cent by 2010.

Though the hike looks moderate,

the government wanted to in

crease its contribution from ex

isting 0.9 per cent of GDP to two

per cent within the next ten years,

Union Health Minister Dr C P

Thakur said.

At the same time, states have

been asked to increase their

health expenditure from existing

5.5 per cent to seven per cent by

2005. Currently per capita health

budget per year for a person is Rs

160 and the ministry feels that

without a hike, the health infra

structure can not be improved.

Another major development

envisaged in the draft policy is

setting up a Medical Grants

Commission (MGC) in the line of

University Grants Commission

(UGC) to fund government

medical colleges.

several drug trial controversies at

Regional Cancer Centre (RCC) in

Thiruvananthapuram and Metro

Hospital in Noida, the Centre has

decided to entrust Medical

Council of India (MCI) with the

duty of rigorously implementing

a code of ethics formulated by

Indian Council of Medical

Research.

At present the guidelines are

valid only for government institu

tions, but the ministry is contem

plating to extend it to the private

sector.

Strict enforcement of food and

drugs standard, having an es

timate of common diseases, oper

ationalising an integrated disease

control network by 2005, raising

the seats in public health and

family medicine disciplines,

taking extra care of mental health

decentralise

patients

and

of

various

implementation

programmes by the year —

2005I are

of the

major suggestions

some c—--envisaged in the draft health

2005.

However, in the wake of policy.

Other suggestions to improve

medical education include ex

posing under graduate students to

geriatrics (old age diseases) and

other frontier areas of medical

science.

It seeks extra allocation for

primary health centres. The sec

toral outlay for primary health

care would be 55 per cent of

health budget while 35 per cent

will go to secondary care and rest

for the tertiary sector. It further

advocates delivering essential

drugs to primary health care

centres and introducing user

charges at secondary and tertiary

health care units.

The new policy, on one hand

supports more role for the Centre

in the health care sector, pri

marily because lack of funds

available with the states, and

more private participation on the

other. On medical research, it

calls for an expenditure of one per

cent of total health spending by

New health policy

draft unveiled

By Our Special Correspondent

2 NEW DELHI, SEPT. 4. The Union

n Health Minister, Dr. C.P.

k? Thakur, today unveiled the draft

J* of a new National Health Policy,

111

which envisages a massive

infusion of public investment to

£

rejuvenate the healthcare

system.

o According to the document,

o

7 the expenditure by the

" Government sector — both

Centre and the States — on the

U) health sector would be doubled

over the next 10 years, from 0.9

. • per cent of GDP at present to 2

per cent of GDP by 2010, with

the Centre shouldering the bulk

of the increase.

While the expenditure by the

States is proposed to be

increased from 5.5 per cent to 7

per cent by 2005, the Centre’s

contributions to the national

expenditure on health would be

increased from 15 per cent to 25

per cent.

Releasing the document at a

press conference, Dr. Thakur

said the Centre would play a

greater role as the States were

not in a position to improve

their healthcare system on their

own.

£

it

Almost 94 per cent of the

States’ budget on health went

towards salary and other such

expenditures and as a result

hardly any money was left for

purchase of drugs, let alone

improving the infrastructure.

A major thrust of the

proposed policy would be to

refurbish the State medical

colleges, which have been

decaying for want of financial

support and make them an

additional channel for delivery

of medical care, apart from the

healthcare set up in the form of

primary health centres and

district hospitals.

The draft policy has been

circulated to the States and

other Central Ministries for their

comments. The general public

could also give their comment.

It has been put out in the

Health Ministry’s website,

www.mohfw.nic.in.

After dTre-month, it would be

finalised and placed before the

Union Cabinet for its approval.

t

health in India

Subject: health in india

Date: Thu, 06 Sep 2001 11:05:56 -0700

From: iiity <nity68@vsnl.com>

To: amit@corpwalch.org

CC: tnarayan@vsnl.com, sochara@vsnl.com

New health policy will widen inequities

KALPANA JAIN, TIMES NEWS NETWORK

DELHI: The new health policy, revised after a long gap of almost two

decades, will only increase the inequities in provision of health care. The

policy nor only suggests user charges ar rhe district-level hospitals bur

also a system of licentiate medical practitioners to meet the needs of

primary health centres.

Undoubtedly, the policy voices the right concerns on patents, medical

research and education, communicable diseases, ethics and women’s health.

It also seems to be interested in reviving the weakest health care link *

the PHCs, with its suggestion of additional 55 per cent of the current

ouulay for uhem. rhe secondary and rerniary sectors gen only 35 per cenn

and 10 per cent respectively.

But evenas it suggests to revive these sectors, the government does

express its ^n.ot-i-'ty to get nAdic^l doctors to work" the^e. ThereforA, i t

suggests encotiraging th-e practice of licentiate medical practitioners and

training oi paramedical peracanei tc provide health care in difficult

areas. Clearly, cue goverrnuent has different standards of care for the rith

ano che poor.

Moreover, it wants to open more centres, which will require additional

staff as well. As it is, a large part of government money ooes into

salaries. The issue then is how far the additional allocation will he

useful for reviving PECs. It would he worth pointing out that for the

co,CCO PHCs supposed uo be functioning across the country, there is already

a sanctioned strength of 23, GOG doctors.

The PHCs are expected to take the macor disease load while also working at

their prevention. But with the current functioning, the burden spills over

to specialised and super-speciality centres. It is at this level'that the

government proposes a user fee, a suggestion which most likely will push

more into the hands of the private sector.

Source : rhe rimes of India, September 6, 2001

I

1 ofl

9/7/01

4

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.htm

1

DRAFT NATIONAL HEALTH POLICY - 2001

1. INTRODUCTORY

1.1 A National Health Policy was last formulated in 1983 and since then, there have been

very marked changes in the determinant factors relating to the health sector. Some of the

policy initiatives outlined in the NHP-1983 have yielded results, while in several other

areas, the outcome has not been as expected.

1.2 The NHP-1983 gave a general exposition of the recommended policies required in

the circumstances then prevailing in the health sector. The noteworthy initiatives under

that policy were

A phased, time-bound programme for setting up a well-dispersed network of

comprehensive primary health care sendees, linked with extension and health

education, designed in the context of the ground reality that elementary health

problems can be resolved by the people themselves;

ii. Intermediation through ‘Health volunteers’ having appropriate knowledge, simple

skills and requisite technologies;

in. Establishment of a well-worked out referral system to ensure that patient load at the

higher levels of the hierarchy is not needlessly burdened by those who can be

treated at the decentralized level;

iv. An integrated net-work of evenly spread speciality and super-speciality services;

encouragement of such facilities through private investments for patients who can

pay, so that the draw on the Government’s facilities is limited to those entitled to

free use.

1.

1.3 Government initiatives in the pubic health sector have recorded some noteworthy

successes over time. Smallpox and Guinea Worm Disease have been eradicated from the

country; Polio is on the verge of being eradicated; Leprosy, Kala Azar, and Filariasis can

be expected to be eliminated in the foreseeable future. There has been a substantial drop

in the Total Fertility Rate and Infant Mortality Rate. The success of the initiatives taken

in the public health field are reflected in the progressive improvement of many

demographic / epidemiological / infrastructural indicators over time - (Box-I).

A

Box-1 : Through The Years - 1951-2000Achievements

* i

•

_____

Indftatof

1951

1981

2000

Life Expectancy

36.7

54

64.6(RGI)

Crude Birth Rate

40.8

33.9(SRS)

26.1(99 SRS)

Crude Death Rate

25

12.5(SRS)

8.7(99 SRS)

IMR

146

110

70 (99 SRS)

demographic Changes

9/6/01 4:20 PM

1 of22

■ i t

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED natipnalhe^Jthpolic.hiiTi

1

Epidemiological Shifts

Malaria (cases in million)

75

2.7

: 2.2

Leprosy cases per 10,000

population

38.1

57.3

3.74

>44,887

Eradicated

L,

Small Pox (no of cases)

Guineaworm ( no. of cases)

>39.792

Eradicated

Polio

29709

■ 265

57,363

i 1,63,181

Infrastructure

I__________

SC/PHC/CHC

725

i (99-RHS)

Dispensaries &Hospitals( all)

9209

23,555

! 43,322

(95-96-CBHI)

Beds (Pvt & Public)

117,198

569.495

i 8,70,161

(95-96-CBHI)

Doctors( Allopathy)

61,800

2,68,700

5,03,900

(98-99-MCI)

Nursing Personnel

18,054

1,43,887

7,37,000

(99-INC)

1.4 While noting that the public health initiatives over the years have contributed

significantly to the improvement of these health indicators, it is to be acknowledged that

public health indicators / disease-burden statistics are the outcome of several

*

complementary initiatives under the wider umbrella of the developmental sector,

covering Rural Development, Agriculture, Food Production, Sanitation, Drinking Waiter

Supply, Education, etc. Despite the impressive public health gains as revealed in thej

statistics in Box-I, there is no gainsaying the fact that the morbidity and mortality l|teels • •• •

in the country are still unacceptably high. These unsatisfactory health indices are, in tuifi,

an indication of the limited success of the public health system to meet the preventive

and curative requirements of the general population.

1.5 Out of the communicable diseases, which have persisted over history, incidence of

Malaria has staged a resurgence in the 1980s before stabilising at a fairly high prevalence

level during the 1990s. Over the years, an increasing level of insecticide-resistance has

developed in the malarial vectors in many parts of the country, vvhile the incidence of the

more deadly P-Falciparum Malaria has risen to about 50 percent in the country as a

2 of 22

9/6/01 4:28 PM

file: 7.P /EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.htm

1

whole. In respect of TB, the public health scenario has not shown any significant decline

in the pool of infection amongst the community, and, there has been a distressing trend

in increase of drug resistance in the type of infection prevailing in the country. A new

and extremely virulent communicable disease - HIV/AIDS - has emerged on the health

scene since the declaration of the NHP-1983. As there is no existing therapeutic cure or

vaccine for this infection, the disease constitutes a serious threat, not merely to public

health but to economic development in the country. The common water-borne infections

- Gastroenteritis, Cholera, and some forms of Hepatitis - continue to contribute to a high

level of morbidity in the population, even though the mortality rate may have been

somewhat moderated. The period after the announcement of NHP-83 has also seen an

increase in mortality through ‘life-style’ diseases- diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular

diseases. The increase in life expectancy has increased the requirement for geriatric care.

Similarly, the increasing burden of trauma cases is also a significant public health

problem. The changed circumstances relating to the health sector of the country since

1983 have generated a situation in which it is now necessary to review the field, and to

formulate a new policy framework as the National Health Policy-2001.

1.6 NHP-2001 will attempt to set out a new policy framework for the accelerated

achievement of Public health goals in the socio-economic circumstances currently

prevailing in the country.

2. CURRENT SCENARIO

2.1 FINANCIAL RESOURCES

The public health investment in the country over the years has been comparatively low,

and as a percentage of GDP has declined from 1.3 percent in 1990 to 0.9 percent in 1999.

The aggregate expenditure in the Health sector is 5.2 percent of the GDP. Out of this,

about 20 percent of the aggregate expenditure is public health spending, the balance

being out-of-pocket expenditure. The central budgetary allocation for health over this

period, as a percentage of the total Central Budget, has been stagnant at 1.3 percent,

while that in the States has declined from 7.0 percent to 5.5 percent. The current annual

per capita public health expenditure in the country is no more than Rs. 160. Given these

statistics, it is nd surprise that the reach and quality of public health services has been

below the desirable standard. Under the constitutional structure, public health is the

responsibility of the States. In this framework, it has been the expectation that the

principal contribution for the funding of public health services will be from States’

resources, with some supplementary input from Central resources. In this backdrop, the

contribution of Central resources to the overall public health funding has been limited to

about 15 percent. The fiscal resources of the State Governments are known to be very

inelastic. This itself is reflected in the declining percentage of State resources allocated

to the health sector out of the State Budget. If the decentralized pubic health services in

the country are to improve significantly, there is a need for injection of substantial

resources into the health sector from the Central Government Budget. This approach,

despite the formal Constitutional provision in regard to public health, is a necessity if the

State public health services - a major component of the initiatives in the social sector are not to become entirely moribund. The NHP-2001 has been formulated taking into

consideration these ground realities in regard to the availability of resources.

3 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED natjonalhealthpolic.html

1

2.2 EQUITY

2.2.1 In the period when centralized planning was accepted as a key instrument of

development in the country, the attainment of an equitable regional distribution was

considered one of its major objectives. Despite this conscious focus in the development

process, the statistics given in Box-II clearly indicate that attainment of health indices

have been very uneven across the rural - urban divide.

Box II : Differentials in Health Status Among States

Sector

Population

BPL (%)

IMR/

<5iMort-ality

Per 1000

per 1000

(NFHS II)

Live Births

(1999-SRS)

Weight \ MMR/

For AgeLakh

(Annual

% of

Report

Children

Under 3

2000)

years

Leprosy

cases per

10000

popula-tion

Malaria

+ve

Cases in

year

2000 (in

thousands)

(<-2SD)

India

26.1

70

94.9

47

Rural

27.09

75

103.7

49.6

Urban

23.62

44

63.1

38.4

408

3.7

2200

■

Better

Performing

States

Kerala

12.72

14

18.8

27

87

0.9

5.1

Maharastra

25.02

48

58.1

50

135

3.1

138

TN

21.12

52

63.3

37

79

4.1

56

Orissa

47.15

97

104.4

54

498

7.05

483

Bibar

42.60

63

105.1

54

707

11.83

132

i Rajasthan

• 15.28

81

114.9

51

607

0.8

53

i UP

31.15

84

122.5

52

707

4.3

99

I MP

37.43

90

137.6

55

498

3.83

528

Low

Performing

States

Also, the statistics bring out the wide differences between the attainments of health goals

in the better- performing States as compared to the low-performing States. It is clear that

national averages of health indices hide wide disparities in public health facilities and

health standards in different parts of the country. Given a situation in which national

averages in respect of most indices are themselves at unacceptably low levels, the wide

4 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED'nationalhealthpolic.htm

1

inter-State disparity implies that, for vulnerable sections of society in several States,

access to public health services is nominal and health standards are grossly inadequate.

Despite a thrust in the NHP-1983 for making good the unmet needs of public health

services by establishing more public health institutions at a decentralized level, a large

gap in facilities still persists. Applying current norms to the population projected for the

year 2000, it is estimated that the shortfall in the number of SCs/PHCs/CHCs is of the

order of 16 percent. However, this shortage is as high as 58 percent when disaggregated

for CHCs only. The NHP-2001 will need to address itself to making good these

deficiencies so as to narrow the gap between the various States, as also the gap across the

rural-urban divide.

2.2.2 Access to, and benefits from, the public health system have been very uneven

between the better-endowed and the more vulnerable sections of society. This is

particularly true for women, children and the socially disadvantaged sections of society.

The statistics given in Box-Ill highlight the handicap suffered in the health sector on

account of socio-economic inequity.

Box-Ill : Differentials in Health status Among Socio-Economic Groups

Infant

Mortality/l 000

Under 5

Mortality/l 000

% Children

70

94.9

47

' Scheduled Castes

83

119.3

53.5

Scheduled Tribes

84.2

126.6

55.9

Other Disadvantaged

I.1

i Others

76

103.1

47.3

61.8

82.6

41.1

Indicator

India

Underweight

' Social Inequity

2.2.3 It is a principal objective of NHP-2001 to evolve a policy structure which reduces

these inequities and allows the disadvantaged sections of society a fairer access to public

health services.

2.3 DELIVERY OF NATIONAL PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAMMES

2.3.1 It is self-evident that in a country as large as India, which has a wide variety of

socio-economic settings, national health programmes have to be designed with enough

flexibility to permit the State public health administrations to craft their own programme

package according to their needs. Also, the implementation of the national health

programme can only be carried out through the State Governments’ decentralized public

health machinery. Since, for various considerations, the responsibility of the Central

Government in binding additional public health services will continue over a period of

time, the role of the Central Government in designing broad-based public health

initiatives will inevitably continue. Moreover, it has been observed that the technical and

managerial expertise for designing large-span public health programmes exists with the

5 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED natipnalhealthpolic.htm

Central Government in a considerable degree; this expertise can be gainfully utilized in

designing national health programmes for implementation in \ arying socio-economic

settings in the states.

2.3.2 Over the last decade or so, the Government has relied upon a ‘vertical’

implementational structure for the major disease control programmes. Through this, the

system has been able to make a substantial dent in reducing the burden of specific

diseases. However, such an organizational structure, which requires independent

manpower for each disease programme, is extremely expensive and difficult to sustain.

Over a long time-range, ‘vertical’ structures may only be affordable for diseases, which

offer a reasonable possibility of elimination or eradication in a foreseeable time-span. In

this background, the NHP-2001 attempts to define the role of the Central Government

and the State Governments in the public health sector of the country'.

2.4 THE STATE OF PUBLIC HEALTH INFRA-STRUCTURE

2.4.1 The delineation of NHP-2001 would be required to be based on an objective

assessment of the quality and efficiency of the existing public health machinery in the

field. It would detract from the quality of the exercise if, while framing a new policy, it

is not acknowledged that the existing public health infrastructure is far from satisfactory.

For the out-door medical facilities in existence, funding is generally insufficient; the

presence of medical and para-medical personnel is often much less than required by the

prescribed norms; the availability of consumables is frequently negligible; the equipment

in many public hospitals is often obsolescent and unusable; and the buildings are in a

dilapidated state. In the in-door treatment facilities, again, the equipment is often

obsolescent; the availability of essential drugs is minimal; the capacity of the facilities is

grossly inadequate, which leads to over-crowding, and consequentially to a steep

deterioration in the quality of the services. As a result of such inadequate public health

facilities, it has been estimated that less than 20 percent of the population seeks the OPD

services and less than 45 percent avails of the facilities for in-door treatment in public

hospitals. This is despite the fact that most of these patients do not have the means to

make out-of-pocket payments for private health services except at the cost of other

essential expenditure for items such as basic nutrition.

2.5 EXTENDING PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES

2.5.1 While in the country generally there is a shortage of medical manpower, this

shortfall is disproportionately impacted on the less-developed and rural areas. No

incentive system attempted so far, has induced private medical manpower to go to such

areas; and, even in the public health sector it has usually been a losing battle to deploy

medical manpower in such under-served areas. In such a situation, the possibility needs

to be examined for entrusting some limited public health functions to nurses, paramedics

and other personnel from the extended health sector after imparting adequate training to

them.

2.5.2 India has a vast reservoir of practitioners in the Indian Systems of Medicine and

Homoeopathy, who have undergone formal training in their own disciplines. The

possibility of using such practitioners in the implementation of State/Central

Government public health Programmes, in order to increase the reach of basic health

6 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 P.M

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.htm

care in the country, is addressed in the NHP-2001.

2.6 ROLE OF LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS

2.6.1 Some States have adopted a policy of devolving programmes and funds in the

health sector through different levels of the Panchayati Raj Institutions. Generally, the

experience has been a favourable one. The adoption of such an organisational structure

has enabled need-based allocation of resources and closer supervision through the

elected representatives. NHP- 2001 examines the need for a wider adoption of this mode

of delivery of health services, in rural as well as urban areas, in other parts of the

country.

2.7 MEDICAL EDUCATION

2.7.1 Medical Colleges are not evenly spread across various parts of the country. Apart

from the uneven geographical distribution of medical institutions, ,the quality of

education is highly uneven and in several instances even sub-standard. It is a common

perception that the syllabus is excessively theoritical, making it difficult for the fresh

graduate to effectively meet even the primary health care needs of the population. There

is an understandable reluctance on the part of graduate doctors to serve in areas distant

from their native place. NHP-2001 will suggest policy initiatives to rectify these

disparities.

2.7.2 Certain medical discipline, such as, molecular biology and gene-manipulation,

have become relevant in the period after the formulation of the previous National Health

Policy. Also, certain speciality disciplines - Anesthesiology. Radiology and Forensic

Medicines - are currently very scarce, resulting in critical deficiencies in the package of

available public health services. The components of medical research in the recent years

have changed radically. In the foreseeable future such research will rely increasingly on

such new disciplines. It is observed that the current under-graduate medical syllabus

does not cover such emerging subjects. NHP-2001 will make appropriate

recommendations in this regard.

2.8 NEED FOR SPECIALISTS IN ‘PUBLIC HEALTIU AND ‘FAMILY MEDICINE’

2.8.1 In any developing country with inadequate availability of health services, the

requirement of expertise in the areas of‘public health’ and ‘family medicine’ is very

much more than the expertise required for other specialized clinical disciplines. In India,

the situation is that public health expertise is non-existent in the private health sector,

and far short of requirement in the public health sector. Also, the current curriculum in

the graduate / post-graduate courses is outdated and unrelated to contemporary

community needs. In respect of ‘family medicine’, it needs to be noted that the more

talented medical graduates generally seek specialization in clinical disciplines, while the

remaining go into general practice. While the availability of postgraduate educational

facilities is 50 percent of the total number of the qualifying graduates each year, and can

be considered adequate, the distribution of the disciplines in the postgraduate training

facilities is overwhelmingly in favour of clinical specializations. NHP-2001 examines

the need for ensuring adequate availability of personnel with specialization in the ‘public

health’ and ‘family medicine’ disciplines, to discharge the public health responsibilities

in the country.

7 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.hiu.

2.9 URBAN HEALTH

2.9.1 In most urban areas, public health sendees are very meagre. To the extent that such

services exist, there is no uniform organisational structure. The urban population in the

country is presently as high as 30 percent and is likely to go up to around 33 percent by

2010. The bulk of the increase is likely to take place through migration, resulting in

slums without any infrastructure support. Even the meagre public health services

available do not percolate to such unplanned habitations, forcing people to avail of

private health care through out-of-pocket expenditure. The rising vehicle density in large

urban agglomerations has also led to an increased number of serious accidents requiring

treatment in well-equipped trauma centres. NHP-2001 will address itself to the need for

providing this unserved population a minimum standard of health care facilities.

2.10 MENTAL HEALTH

2.10.1 Mental health disorders are actually much more prevalent than are visible on the

surface. While such disorders do not contribute significantly to mortality, they have a

serious bearing on the quality of life of the affected persons and their families. Serious

cases of mental disorder require hospitalization and treatment under trained supervision.

Mental health institutions are perceived to be woefully deficient in physical

infrastructure and trained manpower. NHP-2001 will address itself to these deficiencies

in the public health sector.

2.H INFORMATION, EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION

2.11.1 A substantial component of primary health care consists of initiatives for

disseminating, to the citizenry, public health-related information. Public health

programmes, particularly, need high visibility at the decentralized level in order to have

any impact. This task is particularly difficult as 35 percent of our country’s population is

illiterate. The present IEC strategy is too fragmented, relies heavily on mass media and

does not address the needs of this segment of the population. It is often felt that the

effectiveness of IEC programmes is difficult to judge; and consequently, it is often

asserted that accountability, in regard to the productive use of such funds, is doubtful.

NHP-2001, while projecting an IEC strategy, will fully address the inherent problems

encountered in any IEC programme designed for improving awareness in order to bring

about behavioural change in the general population.

2.11.2 It is widely accepted that school and college students are the most receptive

targets for imparting information relating to basic principles of preventive health care.

NHP-2001 will attempt to target this group to improve the general level of health

awareness.

2.12 MEDICAL RESEARCH

2.12.1 Over the years, medical research activity in the country has been very limited. In

the Government, such research has been confined to the research institutions under the

Indian Council of Medical Research, and other institutions funded by the States/Central

Government. Research in the private sector has assumed some significance only in the

last decade. In our country, where the aggregate annual health expenditure is of the order

S of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.hur

1

of Rs. 80.000 crores, the expenditure in 1998-99 on research, both public and private

sectors, was only of the order of Rs. 1150 crores. It would be reasonable to infer that

with such low research expenditure, it would be virtually impossible to make any

dramatic break-through within the country, by way of new molecules and vaccines; also,

without a minimal back-up of applied and operational research, it would be difficult to

assess whether the health expenditure in the country is being incurred through optimal

applications and appropriate public health strategies. Medical Research in the country

needs to be focused on therapeutic drugs/vaccines for tropical diseases, which are

normally neglected by international pharmaceutical companies on account of limited

profitability potential. The thrust will need to be in the newly-emerging frontier areas of

research based on genetics, genome-based drug and vaccine development, molecular

biology, etc. NHP-2001 will address these inadequacies and spell out a minimal quantum

of expenditure for the coming decade, looking to the national needs and the capacity of

the research institutions to absorb the funds.

2.13 ROLE OF THE PRIVATE SECTOR

2.13.1 Considering the economic restructuring underway in the country, and over the

globe, since the last decade, the changing role of the private sector in providing health

care will also have to be addressed in NHP 2001. Currently, the contribution of private

health care is principally through independent practitioners. Also, the private sector

contributes significantly to secondary-level care and some tertiary care. With the

increasing role of private health care, the need for statutory licensing and monitoring of

minimum standards of diagnostic centres / medical institutions becomes imperative.

NHP-2001 will address the issues regarding the establishment of a regulatory

mechanism to ensure adequate standards of diagnostic centres / medical institutions,

conduct of clinical practice and delivery of medical services.

2.13.2 Currently, non-Govemmental service providers are treating a large number of

patients at the primary level for major diseases. However, the treatment regimens

followed are diverse and not scientifically optimal, leading to an increase in the

incidence of drug resistance. NHP-2001 will address itself to recommending

arrangements, which will eliminate the risks arising from inappropriate treatment.

2.13.3 The increasing spread of information technologt raises the possibility of its

adoption in the health sector. NHP-2001 will examine this possibility.

2.14 ROLE OF THE CIVIL SOCIETY

2.14.1 Historically, the practice has been to implement major national disease control

programmes through the public health machinery of the State/Central Governments. It

has become increasingly apparent that certain components of such programmes cannot

be efficiently implemented merely through government functionaries. A considerable

change in the mode of implementation has come about in the last two decades, with an

increasing involvement of NGOs and other institutions of civil society. It is to be

recognized that widespread debate on various public health issues have, in fact, been

initiated and sustained by NGOs and other members of the civil society. Also, an

increasing contribution is being made by such institutions, in the delivery of different

components of public health services. Certain disease control programmes require close

9 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhe'akhpolic.htir.

1

inter-action with the beneficiaries for regular administration of drugs: periodic carrying

out of the pathological tests; dissemination of information regarding disease control and

other general health information. NHP-2001 will address such issues and suggest policy

instruments for implementation of public health programmes through individuals and

institutions of civil society.

2.15 NATIONAL DISEASE SUR\ EILLANCE NETWORK

2.15.1 The technical network available in the country for disease surveillance is

extremely rudimentary and to the extent that the system exists, it extends only up to the

district level. Disease statistics are not flowing through an integrated network from the

decentralized public health facilities to the State/Central Government health

administration. Such an arrangement only provides belated information, which, at best,

serves a limited statistical purpose. The absence of an efficient disease surveillance

network is a major handicap in providing a prompt and cost effective health care system.

The efficient disease surveillance network set up for Polio and HIV/AIDS has

demonstrated the enormous value of such a public health instrument. Real-time

information of focal outbreaks of common communicable diseases - Malaria, GE,

Cholera and JE - and other seasonal trends of diseases, would enable timely

intervention, resulting in the containment of any possible epidemic. In order to be able to

use an integrated disease surveillance network, for operational purposes, real-time

information is necessary at all levels of the health administration. NHP-2001 would

address itself to this major systemic shortcoming in the administration.

2.16 HEALTH STATISTICS

2.16.1 The absence of a systematic and scientific health statistics data-base is a major

deficiency in the current scenario. The health statistics collected are not the product of a

rigorous methodology. Statistics available from different parts of the country, in respect

of major diseases, are often not obtained in a manner which make aggregation possible,

or meaningful.

2.16.2 Further, absence of proper and systematic documentation of the various financial

resources used in the health sector is another lacunae witnessed in the existing scenario.

This makes it difficult to understand trends and levels of health spending by private and

public providers of health care in the country, and to address related policy issues and

formulate future investment policies.

2.16.3 NHP-2001 will address itself to the programme for putting in place a modem and

scientific health statistics database as well as a system of national health accounts.

2.17 WOMEN'S HEALTH

2.17.1 Social, cultural and economic factors continue to inhibit women from gaining

adequate access to even the existing public health facilities. This handicap does not just

affect women as individuals; it also has an adverse impact on the health, general

well-being and development of the entire family, particularly children. NHP 2001

recognises the catalytic role of empowered women in improving the overall health

standards of the community.

10 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.htm

1

2.18 MEDICAL ETHICS

2.18.1 Professional medical ethics in the health sector is a area, which h not received

much attention in the past. Also, the new frontier areas of research - involving gene

manipulation, organ'human cloning and stem cell research impinge on visceral issues

relating to the sanctity of human life and the moral dilemma of human intervention in the

designing of life forms. Besides these, in the emerging areas of research, there is an

un-charted risk of creating new life forms, which may irreversibly damage the

environment, as it exists today. NHP - 2001 recognises that moral and religious dilemma

of this nature, which was not relevant even two years ago, now pervades mainstream

health sector issues.

2.19 ENFORCEMENT OF QUALITY STANDARDS FOR FOOD AND DRUGS

2.19.1 There is an increasing expectation and need of the citizenry for efficient

enforcement of reasonable quality standards for food and drugs. Recognizing this need,

NHP - 2001 makes an appropriate policy recommendation.

2.20 REGULATION OF STANDARDS IN PARA MEDICAL DISCIPLINES

2.20.1 It has been observed that a large number of training institutions have mushroomed

particularly in the private sector, for several para medical disciplines - Lab Technicians.

Radio Diagnosis Technicians, Physiotherapists, etc. Currently, there is no

regulation/monitoring of the curriculum, or the performance of the practitioners in these

disciplines. NHP-2001 will make recommendations to ensure standardization of training

and monitoring of performance.

2.21 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH

2.21.1 Work conditions in several sectors of employment in the country are

sub-standard. As a result of this, workers engaged in such activities become particularly

prone to occupation-linked ailments. The long-term risk of chronic morbidity is

particularly marked in the case of child labour. NHP-2001 will address the risk faced by

this particularly vulnerable section of the society.

2.22 PROVIDING MEDICAL FACILITIES TO USERS FROM QA ERSEAS

2.22.1 The secondary and tertiary facilities available in the country are of good quality

and cost-effective compared to international medical facilities. This is true not only of

facilities in the allopathic disciplines, but also to those belonging to the alternative

systems of medicine, particularly Ayurveda. NHP-2001 will assess the possibilities of

encouraging commercial medical services for patients from overseas.

2.23 IMPACT OF GLOBALIZATION ON THE HEALTH SECTOR

2.23.1 There are some apprehensions about the possible adverse impact of economic

globalisation on the health sector. Pharmaceutical drugs and other health services have

always been available in the country at extremely inexpensive prices. India has

established a reputation for itself around the globe for innovative development of

original process patents for the manufacture of a wide-range of drugs and vaccines

within the ambit of the existing patent laws. With the adoption of Trade Related

11 of 22

9'6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalheakhpolic.htrr

1

Intellectual Property (TRIPS), and the subsequent alignment of domestic patent laws

consistent with the commitments under TRIPS, there will be a significant shift in the

scope of the parameters regulating the manufacture of new drugs/vaccines. Global

experience has shown that the introduction of a TRIPS-consistent patent regime for

drugs in a developing country, would result m an increase in the cost of drugs and

medical services. NHP-2001 will address itself to the future imperatives of health

security in the country, in the post-TRIPS era.

2.24 NON - HEALTH DETERMINANTS

2.24.1 Improved health standards are closely dependent on major non-health

determinants such as safe drinking water supply, basic sanitation, adequate nutrition,

clean environment and primary education, especially of the girl child. NHP-2001 will

not explicitly address itself to the initiatives in these areas, which although crucial, fall

outside the domain of the health sector. However, the attainment of the various targets

set in NHP 2001 assumes a reasonable performance in these allied sectors.

2.25 POPULATION GROWTH AND HEALTH STANDARDS

2.25.1 Efforts made over the years for improving health standards have been neutralized

by the rapid growth of the population. Unless the Population stabilization goals are

achieved, no amount of effort in the other components of the public health sector can

bring about significantly better national health standards. Government has separately

announced the 'National Population Policy - 2000’. The principal common features

covered under the National Population Policy-2000 and NHP-2001, relate to the

prevention and control of communicable diseases; priority to containment of HIV/AIDS

infection; universal immunization of children against all major preventable diseases;

addressing the unmet needs for basic and reproductive health services; and

supplementation of infrastructure. The synchronized implementation of these two

Policies - National Population Policy - 2000 and National Health Policy-2001 - will be

the very cornerstone of any national structural plan to improve the health standards in

the country.

2.26 AL TERNATIVE SYSTEMS OF MEDICINE

2.26.1 Alternative Systems of Medicine - Ayurveda, Unani, Sidha and Homoeopathy provide a significant supplemental contribution to the health care services in the country,

particularly in the underserved, remote and tribal areeas. The main components of

NHP-2001 apply equally to the alternative systems of medicine. However, the policy

features specific to the alternative systems of medicine will be presented as a separate

document.

3. OBJECTIVES

3.1 The main objective of NHP-2001 is to achieve an acceptable standard of good health

amongst the general population of the country. The approach would be to increase access

to the decentralized public health system by establishing new infrastructure in deficient

areas, and by upgrading the infrastructure in the existing institutions. Overriding

importance would be given to ensuring a more equitable access to health services across

the social and geographical expanse of the country. Emphasis will be given to increasing

12 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.htm

1

the aggregate public health investment through a substantially increased contribution by

the Central Government. It is expected that this initiative will strengthen the capacity o?

the public health administration at the State level to render effective service delivery.

The contribution of the private sector in providing health services would be much

enhanced, particularly for the population group, which can afford to pay for services.

Primacy will be given to preventive and first-line curative initiatives at the primary

health level through increased sectoral share of allocation. Emphasis will be laid on

rational use of drugs within the allopathic system. Increased access to tried and tested

systems of traditional medicine will be ensured. Within these broad objectives,

NHP-2001 will endeavour to achieve the time-bound goals mentioned in Box-IV.

Box-IV: Goals to be achieved by 2000-2015

• Eradicate Polio and Yaws

2005

• Eliminate Leprosy

2005

• Eliminate Kala Azar

2010

• Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis

2015

. Achieve Zero level growth of HIV/AIDS

2007

• Reduce Mortality by 50% on account of TB, Malaria

and Other Vector and Water Borne diseases

2010

• Reduce Prevalence of Blindness to 0.5%

2010

. Reduce IMR to 30/1000 And MMR to 100/Lakh

2010

• Improve nutrition and reduce proportion of LBW

Babies from 30% to 10%

2010

Increase utilisation of public health facilities from

current Level of <20 to >75%

2010

• Establish an integrated system of surveillance, National

Health Accounts and Health Statistics.

2005

• Increase health expenditure by Government as a % of

GDP from the existing 0.9 % to 2.0%

2010

• Increase share of Central grants to Constitute at least

25% of total health spending

2010

• Increase State Sector Health spending from 5.5% to 7%

of the budget

2005

2010

Further increase to 8%

4. NHP-2001 - POLIC Y PRESCRIPTIONS

13 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhehlthpolic.hnn

1

4.1 FINANCI AL RESOURCES

The paucity of public health investment is a stark reality. Given the extremely difficult

fiscal position of the State Governments, the Central Government will have to play a key

role in augmenting public health investments. Taking into account the gap in health care

facilities under NHP-2001 it is planned to increase health sector expenditure to 6 percent

of GDP, with 2 percent of GDP being contributed as public health investment, by the

year 2010. The State Governments would also need to increase the commitment to the

health sector. In the first phase, by 2005, they would be expected to increase the

commitment of their resources to 7 percent of the Budget; and. in the second phase, by

2010, to increase it to 8 percent of the Budget. With the stepping up of the public health

investment, the Central Government’s contribution would rise to 25 percent from the

existing 15 percent, by 2010. The provisioning of higher public health investments will

also be contingent upon the increase in absorptive capacity of the public health

administration so as to gainfully utilize the funds.

4.2 EQUITY

4.2.1 To meet the objective of reducing various types of inequities and imbalances inter-regional; across the rural - urban divide; and between economic classes - the most

cost effective method would be to increase the sectoral outlay in the primary health

sector. Such outlets give access to a vast number of individuals, and also facilitate

preventive and early stage curative initiative, which are cost effective. In recognition of

this public health principle, NHP-2001 envisages an increased allocation of 55 percent of

the total public health investment for the primary health sector; the secondary and

tertiary health sectors being targetted for 35 percent and 10 percent respectively.

NHP-2001 projects that the increased aggregate outlays for the primary health sector will

be utilized for strengthening existing facilities and opening additional public health

service outlets, consistent with the norms for such facilities.

4.3 DELIVERY OF NATIONAL PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAMMES

4.3.1 NHP-2001, envisages a key role for the Central Government in designing national

programmes with the active participation of the State Governments. Also, the Policy

ensures the provisioning of financial resources, in addition to technical support,

monitoring and evaluation at the national level by the Centre. However, to optimize the

utilization of the public health infrastructure at the primary level, NHP-2001 envisages

the gradual convergence of all health programmes under a single field administration.

Vertical programmes for control of major diseases like TB, Malaria and HIV/AIDS

would need to be continued till moderate levels of prevalence are reached. The

integration of the programmes will bring about a desirable optimisation of outcomes

through a convergence of all public health inputs. The policy also envisages that

programme implementation be effected through autonomous bodies at State and district

levels. State Health Departments’ interventions may be limited to the overall monitoring

of the achievement of programme targets and other technical aspects. The relative

distancing of the programme implementation from the State Health Departments will

give the project team greater operational flexibility. Also, the presence of State

Government officials, social activists, private health professionals and MLAs/MPs on

the management boards of the autonomous bodies will facilitate well-informed

14 of22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D -EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpolic.lnni

1

decision-making.

4.4 THE STATE OF PUBLIC HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE

4.4.1 As has been highlighted in the earlier part of the Policy, the decentralized Public

health sendee outlets have become practically dysfunctional over large parts of the

country. On account of resource constraint, the supply of drugs by the State

Governments is grossly inadequate. The patients at the decentralized level have little use

for diagnostic services, which in any case would still require them to purchase

therapeutic drugs privately. In a situation in which the patient is not getting any

therapeutic drugs, there is little incentive for the potential beneficiaries to seek the

advice of the medical professionals in the public health system. This results in there

being no demand for medical services, and medical professionals, and paramedics often

absent themselves from their place of duty. It is also observed that the functioning of the

public health service outlets in the four Southern States - Kerala, Andhra Pradesh. Tamil

Nadu and Karnataka - is relatively better, because some quantum of drugs is distributed

through the primary health system network, and the patients have a stake in approaching

the Public health facilities. In this backdrop, NHP-2001 envisages the kick-starting of the

revival of the Primary Health System by providing some essential drugs under Central

Government funding through the decentralized health system. It is expected that the

provisioning of essential drugs at the public health service centres will create a demand

for other professional services from the local population, which, in turn, will boost the

general revival of activities in these service centres. In sum, this initiative under

NHP-2001 is launched in the belief that the creation of a beneficiary interest in the

public health system, will ensure a more effective supervision of the public health

personnel, through community monitoring, than has been achieved through the regular

administrative line of control.

4.4.2 Global experience has shown that the quality of public health services, as reflected

in the attainment of improved public health indices, is closely linked to the quantum and

quality of investment through public funding in the primary health sector. Box-V gives

statistics which show clearly that the standards of health are more a function of accurate

targeting of expenditure on the decentralised primary sector (as observed in China and

Sri Lanka), than a function of the aggregate health expenditure.

Box-V: Public Health Spending in select Countries

15 of22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED naiionalhealthpolic.lu:::

Indicator

I %Public

%Health

Expenditure to I Expenditure

on Health to

GDP

Total Health

Expenditure

%Population

with income of

<S1 day

Infant

Mortality

Rate/1000

India

44.2

70

5.2

17.3

China

18.5

31

2.7

24.9

Sri Lanka

6.6

16

3

45.4

UK

6

5.8

96.9

USA

7

13.7

44.1

Therefore, NHP-2001, while committing additional aggregate financial resources, places

strong reliance on the strengthening of the primary health structure, with which to attain

improved public health outcomes on an equitable basis. Further, it also recognizes the

practical need for levying reasonable user-charges for certain secondary and tertiary

public health care services, for those who can afford to pay.

4.5 EXTENDING PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES

4.5.1 NHP-2001 envisages that, in the context of the availability and spread of allopathic

graduates in their jurisdiction, State Governments would consider the need for expanding

the pool of medical practitioners to include a cadre of licentiates of medical practice, as

also practitioners of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homoeopathy. Simple

services/procedures can be provided by such practitioners even outside their disciplines,

as part of the basic primary health services in under-served areas. Also, NHP-2001

envisages that the scope of use of paramedical manpower of allopathic disciplines, in a

prescribed functional area adjunct to their current functions, would also be examined for

meeting simple public health requirements. These extended areas of functioning of

different categories of medical manpower can be permitted, after adequate training and

subject to the monitoring of their performance through professional councils.

4.5.2 NHP-2001 also recognizes the need for States to simplify the recruitment

procedures and rules for contract employment in order to provide trained medical

manpower in under-served areas.

4.6 ROLE OF LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS

4.6.1 NHP-2001 lays great emphasis upon the implementation of public health

programmes through local self Government institutions. The structure of the national

disease control programmes will have specific components for implementation through

such entities. The Policy urges all State Governments to consider decentralizing

implementation of the programmes to such Institutions by 2005. In order to achieve this,

financial incentives, over and above the resources allocated for disease control

programmes, will be provided by the Central Government.

16 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpoi

4.7 MEDICAL EDUCATION

4.7.1 In order to ameliorate the problems being faced on account of the uneven spread of

medical colleges in various parts of the country, NHP-2001. envisages the setting up of a

Medical Grants Commission for funding new Government Medical Colleges in different

parts of the country. Also, the Medical Grants Commission is envisaged to fund the

upgradation of the existing Government Medical Colleges of the country, so as to ensure

an improved standard of medical education in the country.

4.7.2 To enable fresh graduates to effectively contribute to the providing of primary

health services. NHP-2001 identifies a significant need to modify the existing

curriculum. A need based, skill-oriented syllabus, with a more significant component of

practical training, would make fresh doctors useful immediately after graduation.

4.7.3 The policy emphasises the need to expose medical students, through the

undergraduate syllabus, to the emerging concerns for geriatric disorders, as also to the

cutting edge disciplines of contemporary medical research. The policy also envisages

that the creation of additional seats for post-graduate courses should reflect the need for

more manpower in the deficient specialities.

4.8 NEED FOR SPECIALISTS IN ‘PUBLIC HEALTH* AND ‘FAMILY MEDICINE/

4.8.1 In order to alleviate the acute shortage of medical personnel with specialization in

‘public health’ and ‘family medicine’ disciplines, NHP-2001 envisages the progressive

implementation of mandatory norms to raise the proportion of postgraduate seats in

these discipline in medical training institutions, to reach a stage wherein 'A th of the seats

are earmarked for these disciplines. It is envisaged that in the sanctioning of

post-graduate seats in future, it shall be insisted upon that a certain reasonable number of

seats be allocated to 'public health’ and 'family medicine’ disciplines. Since, the 'public

health' discipline has an interface with many other developmental sectors, specialization

in Public health may be encouraged not only for medical doctors but also for

non-medical graduates from the allied fields of public health engineering, microbiology

and other natural sciences

4.9 URBAN HEALTH

4.9.1 NHP-2001, envisages the setting up of an organised urban primary health care

structure. Since the physical features of an urban setting are different from those in the

rural areas, the policy envisages the adoption of appropriate population norms for the

urban public health infrastructure. The structure conceived under NHP-2001 is a

two-tiered one: the primary centre is seen as the first-tier, covering a population of one

lakh, with a dispensary providing OPD facility and essential drugs to enable access to all

the national health programmes; and a second-tier of the urban health organisation at the

level of the Government general Hospital, where reference is made from the primary

centre. The Policy envisages that the funding for the urban primary health system will be

jointly home by the local self-Govemment institutions and State and Central

Governments.

17 of22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED natipnalheal'thpolic.htm

4.9.2 The National Health Policy also envisages the establishment of fully-equipped

‘hi'b-spoke’ trauma care networks in large urban agglomerations to reduce accident

mortality.

4.10 MI N I AL HEALTH

4.10.1 NHP - 2001 envisages a network of decentralised mental health services for

ameliorating the more common categories of disorders. The programme outline for such

a disease would envisage diagnosis of common disorders by general duty medical staff

and prescription of common therapeutic drugs.

4.10.2 In regard to mental health institutions for in-door treatment of patients, the policy

envisages the upgrading of the physical infrastructure of such institutions at Central

Government expense so as to secure the human rights of this vulnerable segment of

society.

4.11 INFORMATION, EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION

4.11.1 NHP-2001 envisages an IEC policy, which maximizes the dissemination of

information to those population groups, which cannot be effectively approached through

the mass media only. The focus would therefore, be on inter-personal communication of

information and reliance on folk and other traditional media. The IEC programme would

set specific targets for the association of PRIs/NGOs/Trusts in such activities. The

programme will also have the component of an annual evaluation of the performance of

the non-Govemmental agencies to monitor the impact of the programmes on the targeted

groups. The Central/State Government initiative will also focus on the development of

modules for information dissemination in such population groups who normally, do not

benefit from the more common media forms.

4.11.2. NHP-2001 envisages priority to school health programmes aiming at preventive

health education, regular health check-ups and promotion of health seeking behaviour

among children. The school health programmes can gainfully adopt specially designed

modules in order to disseminate information relating to ‘health’ and ‘family life’. This is

expected to be the most cost-effective intervention as it improves the level of awareness,

not only of the extended family, but the future generation as well.

4.12 MEDICAL RESEARCH

4.12.1 NHP-2001 envisages the increase in Government-funded medical research to a

level of 1 percent of total health spending by 2005; and thereafter, up to 2 percent by

2010. Domestic medical research would be focused on new therapeutic drugs and

vaccines for tropical diseases, such as TB and Malaria, as also the Sub-types of

HIV/AIDS prevalent in the country. Research programmes taken up by the Government

in these priority areas would be conducted in a mission mode. Emphasis would also be

paid to time-bound applied research for developing operational applications. This would

ensure cost effective dissemination of existing / future therapeutic drugs/vaccines in the

general population. Private entrepreneurship will be encouraged in the field of medical

research for new molecules / vaccines.

4.13 ROLE OF THE PRIVATE SECTOR

IS of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealthpohc.htn:

1

4.13.1 NHP-2001 envisages the enactment of suitable legislations for regulating

ninimum infrastructure ar 1 quality standards by 200 . in clinical

establishments/medical institutions; also, statutory gui lines for the conduct oi clinical

practice and delivery of medical services are to be developed over the same period. 1 he

policy also encourages the setting up of private insurance instruments for increasing the

scope of the coverage of the secondary and tertiary sector under private health insurance

packages.

4.13.2 To capitalize on the comparative cost advantage enjoyed by domestic health

facilities in the secondary and tertiary sector, the policy will encourage the supply of

services to patients of foreign origin on payment. The rendering of such services on

payment in foreign exchange will be treated as ‘deemed exports’ and will be made

eligible for all fiscal incentives extended to export earnings.

4.13.3 NHP-2001 envisages the co-option of the non-governmental practitioners in the

national disease control programmes so as to ensure that standard treatment protocols are

followed in their day-to-day practice.

4.13.4 NHP-2001 recognizes the immense potential of use of information technology

applications in the area of tele-medicine in the tertiary health care sector. The use of this

technical aid will greatly enhance the capacity for the professionals to pool their clinical

experience.

4.14 ROLE OF THE CIVIL SOCIETY

4.14.1 NHP-2001 recognizes the significant contribution made by NGOs and other

institutions of the civil society in making available health services to the community. In

order to utilize on an increasing scale, their high motivational skills, NHP-2001

envisages that the disease control programmes should earmark a definite portion of the

budget in respect of identified programme components, to be exclusively implemented

through these institutions.

4.15 NATIONAL DISEASE SURVEILLANCE NETWORK

4.15.1 NHP-2001 envisages the full operationalization of an integrated disease control

network from the lowest rung of public health administration to the Central Government,

by 2005. The programme for setting up this network will include components relating to

installation of data-base handling hardware; IT inter-connectivity between different tiers

of the network; and, in-house training for data collection and interpretation for

undertaking timely and effective response.

4.16 HEALTH STATISTICS

4.16.1 NHP-2001 envisages the completion of baseline estimates for the incidence of the

common diseases - TB, Malaria, Blindness - by 2005. The Policy proposes that

statistical methods be put in place to enable the periodic updating of these baseline

estimates through representative sampling, under an appropriate statistical methodology.

The policy also recognizes the need to establish in a longer time frame, baseline

estimates for : the non-communicable diseases, like CVD, Cancer, Diabetes; accidental

19 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED nationalhealihpolic.hu'-

1

injuries; and other communicable diseases, like Hepatitis and JE. NHP-2001 envisages

that, with access to such reliable data on he ir 'idence of various di

es, ’ ' public

health system would move closer to the objective Lf evidence-oased policy making.

4.16.2 In an attempt at consolidating the data base and graduating from a mere

estimation of annual health expenditure, NHP-2001 emphasis on the needs to establish

national health accounts, conforming to the ’source-to-users’ matrix structure. Improved

and comprehensive information through national health accounts and accounting

systems would pave the way for decision makers to focus on relative priorities, keeping

in view the limited financial resources in the health sector.

4.17 WOMENS HEALTH

4.17.1 NHP-2001 envisages the identification of specific programmes targeted at

women’s health. The policy notes that women, along with other under privileged groups

are significantly handicapped due to a disproportionately low access to health care. The

various Policy recommendations of NHP-2001, in regard to the expansion of primary

health sector infrastructure, will facilitate the increased access of women to basic health

care. NHP-2001 commits the highest priority of the Central Government to the funding

of the identified programmes relating to woman’s health. Also, the policy recognizes the

need to review the staffing norms of the public health administration to more

comprehensively meet the specific requirements of women.

4.18 MEDICAL ETHICS

4.18.1 NHP - 2001 envisages that, in order to ensurethat the common patient is not

subjected to irrational or profit-driven medical regimens, a contemporary code of ethics

be notified and rigorously implemented by the Medical Council of India.

4.18.2 NHP - 2001 does not offer any policy prescription at this stage relating to ethics

in the conduct of medical research. By and large medical research within the country is

limited in these frontier disciplines of gene manipulation and stem cell research.

However, the policy recognises that a vigilant watch will have to be kept so that

appropriate guidelines and statutory provisions are put in place when medical research in

the country reaches the stage to make such issues relevant.

4.19 ENFORCEMENT OF QUALITY STANDARDS FOR FOOD AND DRUGS

4.19.1 NHP - 2001 envisages that the food and drug administration will be progressively

strengthened, both in terms of laboratory facilities and technical expertise. Also, the

policy envisages that the standards of food items will be progressively tightened at a

pace which will permit domestic food handling / manufacturing facilities to undertake

the necessary upgradation of technology so as not to be shut out of this production

sector. The policy envisages that, ultimately food standards will be close, if not

equivalent, to codex specifications; and drug standards will be at par with the most

rigorous ones adopted elsewhere.

4.20 REGULATION OF STANDARDS IN PARAMEDICAL DISCIPLINES

4.20.1 NHP-2001 recognises the need for the establishment of statutory professional

20 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

1

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED naiionalhealthpolic.htm

councils for paramedical disciplines to register practitioners, maintain standards of

training, as well as to monitor their performance.

4.21 OCC1 PATIONAL HEALTH

4.21.1 NHP-2001 envisages the periodic screening of the health conditions of the

workers, particularly for high risk health disorders associated with their occupation.

4.22 PROVIDING MEDICAL FACILITIES TO USERS FROM Q\ ERSEAS

4.22.1 NHP-2001 strongly encourages the providing of health services on a commercial

basis to service seekers from overseas. The providers of such services to patients from

overseas will be encouraged by extending to their earnings in foreign exchange, all fiscal

incentives available to other exporters of goods and services.

4.23 IMPACT OF GLOBALISATION ON THE HEALTH SECTOR

4.23.1 NHP-2001 takes into account the serious apprehension expressed by several

health experts, of the possible threat to the health security, in the post TRIPS era, as a

result of a sharp increase in the prices of drugs and vaccines. To protect the citizens of

the country from such a threat, NHP-2001 envisages a national patent regime for the

future which, while being consistent with TRIPS, avails of all opportunities to secure for

the country, under its patent laws, affordable access to the latest medical and other

therapeutic discoveries. The Policy also sets out that the Government will bring to bear

its full influence in all international fora - UN, WHO, WTO. etc. - to secure

commitments on the part of the Nations of the Globe, to lighten the restrictive features of

TRIPS in its application to the health care sector.

5, SUMMATION

5.1 The crafting of a National Health Policy is a rare occasion in public affairs when it

would be legitimate, indeed valuable, to allow our dreams to mingle with our

understanding of ground realities. Based purely on the clinical facts defining the current

status of the health sector, we would have arrived at a certain policy formulation; but,

buoyed by our dreams, we have ventured slightly beyond that in the shape of NHP-2001

which, in fact, defines a vision for the future.

5.2 The health needs of the country are enormous and the financial resources and

managerial capacity available to meet it, even on the most optimistic projections, fall

somewhat short. In this situation, NHP-2001 has had to make hard choices between

various priorities and operational options. NHP-2001 does not claim to be a road-map

for meeting all the health needs of the populace of the country. Further, it has to be

recognized that such health needs are also dynamic as threats in the area of public health

keep changing over time. The Policy, while being holistic, undertakes the necessary risk

of recommending differing emphasis on different policy components. Broadly speaking,

NHP - 2001 focuses on the need for enhanced funding and an organizational

restructuring of the national public health initiatives in order to facilitate more equitable

access to the health facilities. Also, the policy is focused on those diseases which are

principally contributing to the disease burden - TB, Malaria and Blindness from the

category of historical diseases; and HIV/AIDS from the category of‘newly emerging

21 of 22

9/6/01 4:29 PM

1

file: D EMAIL RECEIVED natibnalhealthpolic.hi::’.

diseases’. This is not to say that other items contributing to the disease burden of the

country will be ignored; but only that, resources as also the principal focus of the public

health administration, will recognize certain relatiye priorities.

5.3 One nagging imperative, which has influenced every aspect of NHP-2001. is the

need to ensure that ‘equity’ in the health sector stands as an independent goal. In any

future evaluation of its success or failure, NHP-2001 would like to be measured against

this equity norm, rather than any other aggregated financial norm for the health sector.

Consistent with the primacy given to ‘equity’, a marked emphasis has been provided in

the policy for expanding and improving the primary health facilities, including the new

concept of provisioning of essential drugs through Central funding. The Policy also

commits the Central Government to increased under-writing of the resources for meeting

the minimum health needs of the citizenry. Thus, the Policy attempts to provide

guidance for prioritizing expenditure, thereby, facilitating rational resource allocation.

5.4 NHP-2001 highlights the expected roles of different participating group in the health

sector. Further, it recognizes the fact that, despite all that may be guaranteed by the

Central Government for assisting public health programmes, public health services

would actually need to be delivered by the State administration, NGOs and other

institutions of civil society. The attainment of improved health indices would be

significantly dependent on population stabilisation, as also on complementary efforts

from other areas of the social sectors - like improved drinking water supply, basic

sanitation, minimum nutrition, etc. - to ensure that the exposure of the populace to health

risks is minimized.

Suggestions on the draft policy are welcome. Kindly mail your suggestions to acabopw nb.nic.in within

30 days.