SENIOR CITIZENS

Item

- Title

- SENIOR CITIZENS

- extracted text

-

*

,M

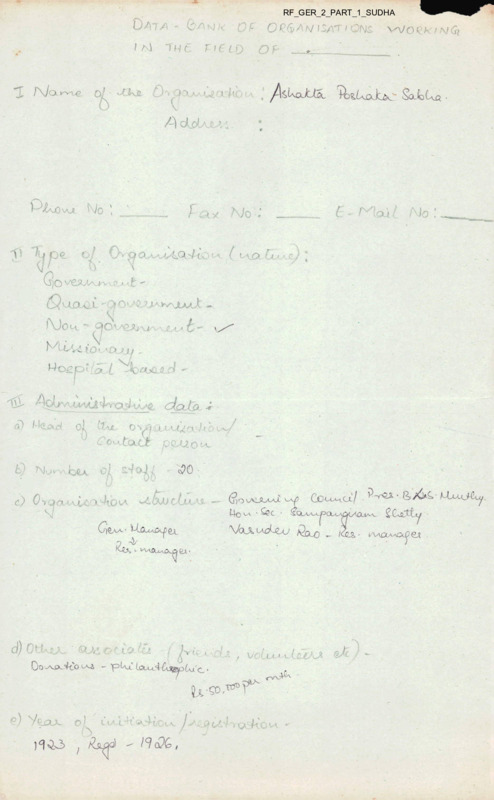

RF_GER_2_PART_1_SUDHA

Of-

D/iT/1 - 0/1nJ/<

'

TWC

fl^LD

ISAT) Qf\)£

WOQX//\/(j^

OP

0^ ^Kn. £N Q'2O^.-NQ'4\b

/A cUNl '.:,

*PZnOvM

Pay No :

O^. O'^^CUvuAGVAjOca

M

<? - N'alZ No .'

(. f-VQ

G}o ^Uzu^uCA -1 C^'-Pad ■ >O’ :' ' • ••■►•z'AAAzt -..

NJoa -

a6

V

NNu io^OAjj

'

^■oepr'51-t

11 Aclj-W. uvlx NrQ.jJ -u/<. O^sdj.

a) M(Nh

ol

o \ >Q ;■ i ! u/ O.' < O

vIajJ-

■' 1

Co^t^tN poXiciiA.

E'

N'jv'wtjCK.

M ■

e.) 0^vo<x<a.Ax^O<a <ZwLcZxv\£

£c

— 1■ t

SCvfiXty

MxJ^laoNj ,

~ /ia- p'V ZAOOSJi

(Si'OvALJM-aI ^aj19

!4o va. ■ Sec ■

(j'|QA'a- ‘

Cecv^cc’/

Ca-

NN

d) (Mmju '

0o-^cv4co

.' JV('. , .' -2 f \JCL'i..t^vleNu Nc N

- pki Gxu.44j^>Ui'ciTVxA^

Vejscx. o)

<'

NN v /^j?tzNoe^'o^ " N o)G t

) /^wd

.

MU<ue<y

<v/

/) > m. 0/.

'Vi |-£^;) -

■I '

■ u') 7\

() ^eseaxc-U.-

la) ^T><1aaaa v\a

V

<-u

Oofjj_rv\£,ct Ca4 lcj<A

u>Uk C>.b.cx. KlG/O".

(j

h Igl

a!

<

}.-• c |. z<,/

Vaj?qe I’

v^vW^OcJl f q OV2A MVV^AXA-tZ )

/O^’ fLtCU

-‘

v'' t/o b 6 m t< '.QU-& <

4'6 c’

0/. ecu^el . pepDl!. .SK

(.

h ^\ -hccu>.' "'

I

)■

/•

&0 .

T

t

C> DeXou^ foo^ / cLz) C<a

0 Vs<-D Ia£laaJ<>

, ^b32L( caJ

-

sp Z?^u(r(U

■

ci) A e

V V^' L ••' ■ ■•

/ SCmlXJL^

GaZa & boy S’

^C yz L\

i

Z c A XL- /

cu boys *

<^ed y ^^odoUjJ

z c^za^Aj^

O At

{ -

P’-vo'v'- (Xy/'U-'g

c) Z) t

Z ■

0/ /■uM.'/Zz

^out c.c

P 3 <_</ sXaa a I

0

-a

~

h) t Jl'JcG.'.'l-t -

fe.^

&X

pex

*911{ 1-

t

u

C. 4

ed C a C

CMC- ■

QW A! c—

3'3 >x

'

•

/\ •

Da u

5) Py^eji/cOtxA pCP^ixcap -* ■ v <

c) T>vKu|^^-^la

e,vi

I)

_ pe ct a. Z-< o

vAc p'.’.: v ■.■ .'<

0

prOtAA

I

(i , ( I Ca..

a.t

.' H

AA'»!jvv<—-«

uZ,

k? v :

s.

Due ■' VLO 4 ( '-

(?)

tu tv'/ 6t

f

•

«

ft c/<cu °

X-! p

.

’/■•'••<■■ 1 <-1

•

<: 7

a-

- VX vM.

9

7

■:

:--*M

■■

'• ■ j

■

'

' '

\

■

rue A^e 2F Q^C.

tb caU C4j-C

2(OTAP ^^^/o,/fe

■

dAte C cwtYics. Lb^

-

'5

- ABSOLUTeey FR^F //

^'bnp fe your

v OppaytA^'kvit^cs to YCj

Hon_to €NTeR

CO TOST

Li^tur^ 0^

<0

CAR^PULO/ W^o (3X^VVVpC^A4j>)^

V'<^ywvp'h>vvvi

A^evv^ OY^/vvisa.i^o-rvsf

2o

^zxTtd- r^zxw\ tb <24a£u/iZ/ tTf&t yow

2>0

K/owr p<U<- <^vvy <^rib>vbrAru dA>t6

---- bzXvV€£vv

CovvvOi t« yoWk WVWV — <&vvyM/a)kMXz

C^

Cd (996 A.f1 vvixvAca^tX ^wv4'A/b6^

i

tt^vr

. C£MAr H4€

L, For

*

rcc^d

C^

fv^Utk^z b^oiA^Le^-

—/ I

ltv6 SUn

&LI II

Uwz ACX)(dywwzl

| n

a

'2.&- uJwM/ dwt Iaw^ yCM/r 1jvt^whfU'

“

^V\ VWvvts (j’tfc ^9

OY ^^rw>t

-

Qw-w) or^'^

•fc^ 35

Uj.W

or h<M (io k 90) or kw^uA/uxi*,

tUe^o^ t

CMJ/o

r 6^/VUV SI vl’CVVU WwXZA/ f^h^|^S'fevtvA<1w

lvwileA> ''^(Tuv^^n7 <

PvvUc

\W^

- N^f

itowv no. '^'

■

, c^ do AM»t «2V«Kt ufsJljFC/ dC'VJY^' ’“ttw ^V^di/vC

to -cvvvviOW/.

, WVn Uv6 (XTwtosb ,Jw OCU^ yov*

jTO^.

/^v\^Gy’>r*A^'^ Is24^I

Wvlt

UV^V^***

Ruu^J

I*

2^

3^

0VV Iwu 'Vwzxitbv •

7PvA4 CArvde^

4

C|)e-W (x?

lix^ tioxA/CZovv 0^

-

-\

k

I-

'

'=81'^5^^

t !

k

'3a\'^>4^^

^vt)

^>'

<2^ <iil\?

c\

<^|b^

’^j vso^xh >3SX^\\J

(jgj9 <a3

o c&L^aDr^’

c&ji

3T

-

j

^) ^A-OoZO’fiu^C’to-j.^nLt

X

'

O"'J'Pc C*-*»yi V- -

- k_y

V

<a

&&C&J eD^^r^^ofpcxW

-^\lT~co^

QJ eP>J-i»W«»i'

6J ^e^Wcw-W^

"P c^v3 to- 3 <x_> V*u

0

J

C>=>

(^ '-^(‘[Z'S'C^

^W(U

^4

1U(

’

3

(5 ‘®l<er>

\ T^)

'^“o^u^nSU

jy_

7

.

. .xi^4^10^

D ex^5y^juo^®^

Q)

(^)

\

rSic^-^'

^T-X^3 j--\ vxCtX'-

^l-) O B~ Ca vtft

’

^q3o^3 clA^^-^Lj

' '

lCty 5^'ux’

(^1

\^3 e^^x.c^rVjy^^

EM^e3n^zU^u4^

@ ^ii^2537

,

1

CX’A- >

Uy^1

f

SU^G^

^X?^pV^tV(5<>^^)

I

g^zr^

Z?n^

'

^5^

Mj<^

< <zzo5

6?ez>

r

/57

^>s(j

r^9

^6^

y T^t^/

c

(Tynpuya <$ ■

I-

M-

-gfcjja .

J

^bjoC^e

r^JOejB ^05

Qooc?e

deSoJj

^J?Jte>e

^§^8,

- «Ax>§j<^ra<^

''La’s/y?? —^/Ls tSje^

A.

j^tAjjcracJbc^

_j3>9^> As^oijjj j4^j. =^0^

'o^j

3•

pSf^eQi&oci)

7j0r?dMu«sj:>

ps®r<4

fyocyij

C>

r

0|<iZ5$J,

/Arm^puTiYlCL

. |T SHt

y < V, k,

«^nc-'Q

P>.'^^url.

^o-LLi-

‘^'

—p

-J’

J

C'rZ C

S-J

y.

pfejtAjcpej /-x3P~]

Yats^^/zt^

^cFon'^f©^

3.' f.

o)X<r-4/la ■

Ms.

y tlVcx-l'C

^en.c/lct

Y^J^cu

r^j)c^xJy^

/i°

o

tocxo^

315

cd-k-xA ~ A^~

^-A

3]

^_|<w1vevvvvntRxo' cy , \J &n kautoJ'-^'tJ'am"r^ct-

_ "/'■a-j

D^^OO

\os£

o

/uoug ^ocvri po^b

5 6 00 SA

Q2AvY^3ve^>

SW 2.3

i\^t^'VCvQU^<^'T^CX

4/ 5?a^U^

<^-5>W ^’ST^ A ^ST

Xe-6o-LcJKLJ2- Z^CAV/rvL>«^

VKfctei ^%<xd >

t>^ jjcsc10^ C^cr^ , J\^KerJ<A

YcysTv ^\^\-s7we

■<(j Q.WJ

T

VqVVMJiUi,

D^Go

0<?|px^p

^1 "s’

/- A-R

Y"AdM Ntxa^v

Tv

V£7nKflTH iWr/Pa^m

PRAXIS.

103 §

ore-

/

XKH, &

^V<cl\avixictti<4vx.G'

SA- Acxwa\

4©CaS'W post ^J-f

Sc-^io^cGtore^

3. p^uk

5fi,

.

33^

f,. c.

■

^01^ riAML”

Nf>LflKlflN(A^

Dl^r

xG

(_ IIko

kGLCa oq

OqH<

LG

- Rstr

p^fCfaj r^CC-QG ',3^—

;

4^

c^vx'

Pmj>r

)e>3g.

SJ-

Asi-^^

f’b'X^x^

Sevu^e^Gnft

g-6 oogZ

k|(E

Ho

PihioR-CSs

vA^-we oflME OK-ei*r<t^'r/£H

d RUGS

Po-S7 <?bOX

MO . -570

»

pe > •

\o t-

3^ Mb R_*ft

M m Ht Lio ^Wt^iP)

P> AW-^vq LNR.&-

d). ft 6H MkDAJTH W PH

/

XOGSUptP\vADE.

52

Rcj-m kt'HiuA.^

[_Rwur KTifibR^

■

3)V4nMOMjmyy\ ,

^LCttKXO^ ^^T^WRyg

LLVCtO pME ^7

s^<Lf £ 7y

rJ^^rH hdK.< SiOkcaK^

raec^fto^. o&-s.3^.

^>1 f<b_s

f^hapooh $!»vLv

^_U Aa-T

!S-c- VtO_a

T

£j ¥ObJ k\£>ia Ltx

C ui c tc_ w

VwvCL-'y

TUH l^U K.

^MVf TM KM Mr^iio

HiaH’LMS

WN &[ V< w NA yft. C M vo M1 'ft

CLt

K\G LIAM lAMei^V-VQ .T^

T^’D^JA

ho

\r

■

•JjfudAsRcLUji'crYt'

kahnda Jyo^' &Juco^'oi Soa'tW

S-C> PaUjai Qanciotne.

J

!

I

.V

.

• •*

f

.1 4

..7

4

. -j o3oj<3 o yAjO^CP- > ejdo^

A (3

~3 ■

«

—J

r

■pyt-d 332A

j_j 'dk'^ 3

6(3 2^3

c>

“

■

/^^odj 3i^W^ ”0^03 t coo R-i

I

G> op/^

C^) 6O"0 A l,S~~

I

5LOo <5

1 R-S

-gdd&oXA)^

’oooy

3ocd3x^

-^Sodjrc^T

2D

__ cftaic?

Vooo/p,^

c^e^^y^pcdjl

-^3^-0

B’oo

A

^(L

k>$>b h^ocj^ —

'-^°? & ~'~i tds

ckiySc^QX)

□ ( 4p#^/

^rG^(^>O<d,

'^fai-kdo

<E^0rX3j

t^Ah,

S.dk

3 3<50fO' jSia^o^od!

-

— s i5^£^

*-

~p

3&?jd)

F^ZO

3) A£^

cJuo^S'^

^3

^--G

^o^bo

’toAj Ji

®> 3" V

■eA^car^ ij'^3o

3odtLjU ts^L©

G|)

fk;cC$-'

. JU ^dj^3 ■ ‘

'

^3^8

j^ooS

(x)^, <j'Pu^ <5~ J

'"'

■6\jU

J ,

e

t5Lo6o

5

^bSV

G 2oP o^J

^7^

cP‘-^3 Ox2>

^zsD

c

r^'^ cxP'J aG-caJ^

<3>- C2>

-rSvyoLt cHr

3^5-

i3U:£^QjJ

4 A <3'0

6 0^6

3«3S^.

xi O \/Xl

^oJb cf.^o tSuJ^e^

YX5\&^-

ewT>e^

\ v<K "&e

\j <

v^Tfev.'A

tL

—<rC\

<<SJ^’Vs\^

S£S\^3\

(,-<^«,t4>^trffe

'3>- 5^^

t*

,<^>^ &0^^

Vi ii^y^'.A' <31..^*^-.'

^a^-^Ad^3 '

>r

-

^>L-

■W>&>'H£)

ptftfgft. ^>oep- rSo.^r^ <55063

60^43 O'

,J

WcP^eSAS, rftSsMio PiA)P ■

’S^Mf?)

sjM\Sb Aii<&

Cs^t'

\

^cjj

-’

&

oi^?- &^‘’B^g§! ^P’VW'' a&r^~

~M**

---------------------- -

■'"'•■7;.

OJJ

Io^q -

/ i

Z

3

i

•■J

DA’

1

<c\Q & 4 'Av^ i ~

' Q

UsT&£) 4

&<^jAd<!X '.

___ 1^ ' h

'SVt)

Vcv-j

s. *A\^

Va^^s

, v^\tV3V^-

x

-

^kaSV^\

<A^Ss v^tsi

■~V>VLt' >s&i

t

■

Vr\^^

o3^

-So^^V^

i’

L2j_.

VS

gp* ^>VA sJ-b^ ' r _ YCt

J

%<^b

ka^

■£

— t\e=t-i«s

^£i ■Kl^S \S <<

■"

~

m

v

<ng *.0^

A

<\^p

t

M^tWo ^4^,

cA

_

— & c 4.0 G^ •$□

—

0-&J li

c£ tS (v^ «£

(Vo75

'SC Q ^sc

,

&>V^ eA ,

CSi3 t ■^.■TS

'AA-^

-^.>

150 A~c Ci

f

^^Sg'V t aSa..

Vsi-v\V

V\\. V.

S«x^ tA-i A sjS <§\ ji

_

4 e>iOA^

%,

\5K\Sl<^§A 'V

Vx&d^^^CAj

^,xA3 ^S-A '. -

^44

^vVL J

--4^eS

5 ^(X

^yij C

m

■^CN ^r

-H 7r3

(^3

^^tk«S\Aa^X _

p. f < C)

.-A\^

o-3o^

\S

^5 vA.\ '\

ocosdi

A

-1

2,

.<v\

__ _

v^^_

&&I

o

<^3

<

gAJ

a.

•—.

%

\

J- f *'

lS)^<JD

^43^6

.—.-—-——-

'“'J

-

rijodj d-

c&tcl^

■■

£«<«

c^xW j$i4)*5

Q

9/ -5 ^)ox? - ^4>0

—

’■>/

(^) t^TD fe J

O

tjJVffOd

‘-J^/Ooaa-1 - so

•&&<>36 -- 6 /

3o/

^6 6bV-

-

M(eLjAj>

Uy

(<) $y3*3;o

co

*T- •

J

aJi c^(^f'j

l£

j Cb/f) iSjo 9 <5

<*<5si

(^

Q)^f

6b Z>L5«^^^J

J-OBfo

1

/P^y^fl^L

^3d«’ <^57

I

i

5? [

.

3<vh^

)

^OGO

K

.. ^

u:/y

I

I ‘

■ ^0

-7

/‘<-r5

P 0'6

^"U

'0

jfr)^

^GGG

<A'

AJ FS

C^8^<3^So^> ^iZ3A

iS^T //v x—->^

Qoy

oVys^

e>^z^? -3-5 tA’

p

7^5^,

%e/ A ©^

^'&<T;

'~z^^>^

£’ ^•.

T J

^3S^

y

0?

«9-3'^r^

o

^fj ■''j

•^■~y}(Jo

^3‘io

■% c^

*

^oU u

^vy^J<; g

/V

v

/

V>U -<■. CjJ CvJ^4)

"fc^k s^^kx k^jasi

/'nd.AWA-'' ■

31

p

ft /V

^<A K t ff^ -J

rr^

£,

rA

A//'.*» ^

\/ C n k«J

c

N

■

• 41 $

•

.

\

-D-

T)o cA cAft-^o c| Cj Lt>« — po^t

i

koxoJ acptM - 'TCjp

'’TiArr'Xux - &}• _

. s\ <9.. V)

sAi_>d*.rS

'

|W, , dVAA-5

^)^/cJU Jbo^ .

^AtfT,(jj

d

/»-J .

<2^

-b \A A.

1

C/aa A ''A1-1

w ' '

4. d ,?o X'-e

_ \J ,

V 0 O Vv CL -

jA TToa-ct^ .

•

o y e c ' o. x 1

M. ' -■'■<■

1

O- V \<

'K'

' \

., xC v-og J.

£><—.--

U & \< 5. ' 0 ' 0 S',

cdnaOi^D

16

©3j

6^(5

L

(e^(9.S1’&t>'d

f^x9

l^dr^

bob tr®

sip

b6

QOod^.

> ^ c5d^

----- ---

c^vJoli v-^

^O&J t3<oij«

oJU

cS

<cre

^V? t5cf£^<£J

r^o^d.'

'^?*

<15^^

(5>

o5^

% '^r<'<^r>

C2) Z-

| s 00 o -

^fr'TSU'V.Kj

cJ^tsr <<J

o5j O o

Ijo b o ■"^ -o

^TsW^cb

9^S d

l^vaju ^<3 d)

gL-cd^

\ .s^¥i?x

2^ rSj Q-')

ere qjc

.

^0 O»-0

S-c^O

2^c crO

■^-0x3

^>dd>

^cdLrfJ

-

I

•£6 B£_ ^no

S?ar)7~?oJU

-g^cdbB

ab (i^oA..

jr^(5l2jd

o^

^^ScS

3^3^

k

^-7-<r>'

5^9^ 3^

^©O^CTS A £?

7 U

SAeS

^°J ~8^

i

■i

^/

5>

y

s ?

7.

crx/

rS)

T

Q

£)

"G

qg

'S ■■*)

v

>>

g

Q

-a 4

9

<5 s

)

i

•o

,i) ^D

o

I

ae

*4)

*3“

«

P e

j| I

o

noo

I

J.

'T

3i i

y*^

Qy

o

D

O

C2O

\

IS oi

q)

'

9^

I

'it P -<3D

t!)

2

0

©) \

o g

'i

5 <8

a£ 1 1

QB

.& t

■§ -S

$ s

A

iy

3 -J

<

0

-£

o

&

G

io

p

/r

o

3 ?

3

f

®o o^A

&

!1

->3^ >

f~) R p)

*

C^CV)

Q$(

^>0

0

o

no

©

n

h

q/

O

°

2

2

3 hul

%

<tp1

I

2

©tj

9

i

Qj

&o

!

3^S t

O

P

C^

I

A A A F) H

!hl

Beta ;

vr

Luaju^

O^ SAc

<xC

.

^Ox?

i^ <JuiAJL H9S '

tAOuLnjcv^ CrivAcbjckJ

' Dy - ■£ P7

No* 0^

:

5e> ■

(9^ycuzvU)Qzl by

KWQ^fe <tk£. tDvti

"Io cocLXitcouY vbka. koal4A. p^^^^vvortex

C^cxoLzol_3

Q’O Q'b ^

>t+ umolo o

' 1_’—'

Aj2jxJ4-R r ^v"e>zQ>x>kc)M.y yoJ'Vq |vyzco'I-u^ul cIxacI c-UAr^4tt’e_ iboydt ctxi ctv<£

UXml .^WcbcxL I. l\X)) iaac_ vvq-i-y'uzoLocy ^Jjo ctRjo vxLLxoeJoi

c

st* z v Pejoy^le-k I4ea I4& <A ’pexy^U^

/

Y\^J^ ^Ax

Q. A£xtbX'+<<o

rvAibrvvfo QJU

o toe., ZiVJLC

■

OOQXC-

L-

’

r^P

y • P-S-

LAP_ JLxDcLy^uX^

iol^<<tt1ci2_qL 4e<- Oc

-bKjL

^ro wt

7

^JajC.^

PYp/oc-t D(Ae_cJdY

rvvCAv (Xv^C/

AqJ»

U_Ay<Jj2jJ^Lctv

*CVC

n<vc4<\Bcisfe^t,

qJ^L*

olvLvvxclvJa

U>\Jb2^XO^^-A^

^OUL^uu^q

^cty^

C4

uu-C’^-C^

IatjuU

UclclPL

I

co >^v>

4o

to&^X

be cxxA^t •

y^Q-Co/ry by

OtKiLV

^LL^M-Olau. —

4 I »•(£)© ex - kw,

<Q»3o jo*

'I

£X^^XX«"vAj2A<r •

'

b\) ttub

*

<ot^ -^OQCS

Jd^Ce^oJ

)4e

UJ© vv\i24A *

—

) • 00 p'

oZi ‘ So

*

•

LOCL^

ell t>D KacU 4A

OciryxC^ V' <ccLl

<P^vx*aj^£1 Z^D

foo! co u-vyslc/^cf <L<_ 4«>ci

£

ebjxxv'dalLCLt.

[e^Apit

<_uCca VAzx^

^uaaoIcaa4 oia<£u_aj^ O-bo ud

e •Molpojsl die v4J^Lrwoo^

pI'VVATCO LC<5

©©<

LU-kihAQ^-

■ ~r^-

©Cbi CULW2O CcO

QXOUA)

glUto

CCoMXQot

AjOOlSX 4 YOlAA

r Lt\^J

<rvwtASlAA

>U?X_Q_

caoouqjZjqL’

WU2.

^COLpD

lll

lyva/oZg./'^-

rnii-vA

jtlvLA

caa-X_JzXjZ-X

0^

- LUQ>JL

OJcuUv. tc £Q.cvtU.vKC’w *

JM-X#

ev^U.

eo.

-t ^CCL

i’'vyo4o

^vla

p'^X'QAvt-vxj'vxA

^AaaX^Ca

Ox <JXlc

mAjQ

^Qxt-LC^i-GLA-L

CUaJ

pAscLilclpc^d

C>^ ^uj^aZca

clot

■ pQL^tiCL^a-L^LK

2a

t)Q_

cj^cCt

UaclxjaIlxj .

To^

a

°6

— jZax£4

'bJu+'rvM-Co LA_ '

CUoekA. 8c ^(XA-Cel-ekskevv

^ptLlJ^L c_ oluA-e-CUxcx

~f^ bt^cijJjo s.

-' fjicLQ'^'Y'o ~ lca^aa4-<lao./

*)A-CU:. (AAOIA d A-kdAc'-MJ

O-bX’v'C

’pyxi blovv^ 6^<xju-.lwe_^ vo'<h-c^

Vppzx.

OYob^xvu /"CoaqA-)

ol '+Aj2. pCLvk'cipCLLC+A

EtW

prj obltxvu KStitnO up tv VQCA-LsO ujo ^AfuJbxi •

.

t?CA^

^xjGJr

^€uA

11

o

«<

£

I

I

'!■/

I

---- ~l-^-=-------

^2COv^y^ —‘

::

CW-

(X4JL- eJCo4-OCV9 /J2.C

X<iZoJ

" tV1CM - N-lCtk^.-'sA otauy *

tvCctvI^-C.-C’'- t

*~ ^oXcs-icuix.

t>?

-___

__

Qn^xit vvAjLjLt —

p^Q^AOLAxjLr

^vtO vvCnP0

<- 1-J-odb'aJL

_gl

cj^AC uxC i£XkG^ ■

U>VkJM-J^cC

-* Zcs4

,/<LCLX7jlto3WM

CqaaaIc

v^o

^Oaaq, C£L<Q(LS

UjOvvtjLn.

y^zvC'

__

/oiaxc. -)<£6^A1V^ O^AdXz^

(SovJj<x

f f£W GQUA.

7

ootlv^kadLc

Qc,

wcKoaaJ^\4

c

jdoLUaJiDvv

VQ V^-vaJLi^JT

c

Cc v <9CA-AX-A£t(_

.

ig^SggTgi

^'^aSg' ^?R(5»

^Y'l'frmv

'P^ r5

‘

)- Li-tp e'^vvWxK,

^pUA^of aJ^cI^C;

22 Po£a>cb6i \

’“'Su3Lc/'Q^|

c

^t/vooU G GaclvcAX •

- CXo^-cA^uyc

USG'.

ouJUL£ccc£t

-Cuxl^ d

/bc^uO vc J3 Lva.

1

\

^J'3Oe.p)

V ^AXL

defect CC'-ttK*. Alccttclbt Z'GXt-v

.

*

zcLc-of . '-L

Cc^LcgI-

u^xaxccULujazv

M^XAl t

0v>

3 VVIO kA^ldA ”

>'

i3.

o

WLCA

k^A^x^tx-.

.^44-

'

_JI___ ______

/Luciy pdx^ p\

VLptOJUU

d vvU-ha4-&a

i;ux^

---- Pp X Afkd J, ug^vutui__________________

-—^'■ddZdnu. - 5?xx£uxxotd CojlaJla^

OaCp- cvu ex vA/a>.<<jN^ (j^vo m^U-

^^ VC <<A^^d ~YXuxy ■

1,-t

hjC €\ Pn(

__3*

\

wKxy '-u

JxmJdX. ^cto

I

/p>

—to——- Q^^uJjZ.Xx-^ <^yx^v -A

7

dutLei^v//.. .Zjzdu/uMU

VdLLo^QAJ, ■___________ ___

___________ _________________________________

_i./JUW7

5 vU^FUSd- fau.

(MedLed jP Uy —

1° Food

/pd tXuL ^A£xy jpecK

U' 'F<Z.ci-<£x.< Qpudj

dude

^WlcL^^vc

-cyo u

-/XuLx OpOA^J^JL

<1

. Io

^^cXpoJ z

A

fVoJ<o laccL Co UjLqe. ,

Jaycu^

D)CLv^CL,

!

'}/^-Ot,cAn^

Vyrp

GHC /

Xgcg

v\JL^JOm_QL

r-

Xd

'VvO L«.C

> X

k-L cC LUL-Lv

Co

olC-LUM^u Pl

Dcy<£2CL<S

</

OLzCa^)

/T)(

kj(L

Cccv\

^ict

w

□

'pc^iblsL,

7

v^oo

Do, JLqJc

tivoc^j

/

CcAx)

ole +Cul

CXcA^

Co vvfe. oGzj^-

C+7 C mjocc/J

MZ * “

UA

UJZ^

0/0 LOU xkc<CO<j2.Xy

X^A^yOc^A. Ca vCt-vxxg?

■ f'

Z?ST 0^ PoN^CT

Co^TAOJ

|. ZX.

ADOZ.^

A^ga of

H • GoDA&SWAX/;

^iVtkANANDA

'TkboJ

C>

U^ATKiAJ

tdcu^cx^ •

k/q/_y^^

(s)i^kT/\k^

^E/MOg-Z) >.

BG. Uiiu- s^'3i?>z

V coc CKcM^OLA^y c<>wcxCj ox z

N_^yOv'e_

o2 'D'r' 6)0pG}

^)~l / ^SoNl

DodboJe. ■

u

/

D koA-UAixd

I Q-j^ ui<vpAj £X^

_ T>d5L<su.t >4’-^y

eat 'g

S'^ OOCcQ .

Oko o. J"O

M^z-a^ccW"

eo^-v—;ry

■z f)v *?k£ArU. kcuX 1

HaaxIW. M

■-)'

v

a.

'TAoJj'Ge ^c<-'

NGrtt ocl^co

NM^a ,

JoJUcx^iaazJxi^ 1 felout, XHotxi 7

^jQAO-a-x/vO^^ '

Gcv^vOCX. lo'Y'Z

SGlDO^q .

fK-M. 5g ii«r?

if - Hr. gwAdux-vu^ VXawxa ■

GvAAQaJcve £.9yotAa.'^fo CuXxC

Cb^^aJL

No<^y cZq^Cto^ S^Bloct

Ju>. p<c^c<\ •'

0 0 C /1

Pk.Mo.

&• Dv.

}uctt^l \£Xk_G u_<_ £<. D~y- G

WIVA OZI^H/IA)AM/

lOALMKptx

Evft^vx.'Ae^t'cG

Z^Zod

nojc vG

V

“VC Llo^'G /

Qn'qCVov^G-

, <i

^uXiSlAaoXU

k-y> /

H^-O N ■ NJbcuolM. •

6’

m)Q>wjlaolL

KLou-aou^1£x ^Seocvi'au)

A^ocLDc^au^v

4£vc

i cot Lljy

Pic^cfcc U y

W cccAnlx uyyp cd .

PcM-vdLlGPjDp^d >

/<AD

y (/jl. CAyQc>c>-y<^^

V^i/ACL^

P- 0 > ?

O VA2

®'

- €(y.

'• SuoLa^lfcc Ea^tcccMXA '

J5XJ2.O TXa^cI^y ,

Ma DP yA /V>|^(3ciM/MOAJio^riohz?.

MerHr /■ /U H"=r"Cr>O<^ . lO^A-tccbn'

Ma-'LUx^ ^oc\qI/

0 CJOlA^. '

lo^

,

^/•O've. — Q C=> ,

CCA

CMC •

(Adclcccc

9' ■v4"v • K^C^tL<ypa^ct /Ha. 1

(SovaC5LKXx_ Po ^

(

3 0 3 /f2 • oCK P ’ S KPcO tec '-aC^CCC,

\ 0vA/\CA/C\XljOvAA£L

CU1(J

ZcjJoocla •

GZajO o /

W-Sca. I

Pos}- ■

A<cvvpu.(X-<\dAD^o<!kjC\ r

T^l- 5 a.7‘StQ'^C

to.

Hr .^Mgcca_j'<.

>'VX>L<v<ci1C'>' ■

l 4<cx4cv^l 7^\

<? IV IQ —

tc^-A^t/ixy

I

(^2^vvjc<^x2

(rduc cccko

C CvI-cj^aaA

^Wtte^LkAc^--

i^o • cj sz) M

^lov^ -0^ P^x

u« 0 YA \J

D> ' Eocbu

3G&S(/J

^C^cIaixcc (xte/

^vClx^ctecdv •

1\Jg '</! r ?CM B Gcfovcy y

ccfcu

^(XAxAcyx

Ct L<^) ■

Gtoo^y .

6oLu cxAe <<

DUcot>dN^y -

><? ; Nt6 . GaapUxa-iaaQoNaJI Aq_C

‘ PyOj' Q_<ut "DlACxXo V z

C<X<jl

QcL\jx.b C LL tcu+to

•

N, —zQc-Nol^z

No. /Gz H J cx

/

Z/^^jfoeL, J<OuyccvMx^tXS. ,

- 11-

0 J> • N-v . V e^Uc_cvL2xN,

Q Xjl ocvt'xNo 1[)<-AJ2-Nov j

0Csc3o<lxU^ '- VC^uix) ■

ZlcTtbw <& VA. DCsS<2uh7G(!y

£( D'e-A>€

No. s 71 z |7+tvGto^./

■ Dy . 6> • S ■ Ax-VOZ N ^XX^vnO-A z

No . £ 7 r P^txGtxvx^o

kAcLx,

&

e>-<Xc<^-

kN. ^vLi/Nvax^O—> NCux'J'^y •

D«-pt • c

cJ^-fx-^/

qLaxcLl'o<

k^jSjx J •^v k

>

N I NA (-+ a N r z

!Ao<va_-v xLcxxdz ■fe’lox^ •

IG- Dv> Vc^

krx^vvpVxu> &o>,

"0C<2~ DCvx^AXuAy

NWVZ3

£i

•J- P. NJ Ca^cX^ ) /2>! o

^(-Nl-tCLL<A^xGN

-' 7-S

17- Ox.g'YcLcUN^ ^<^77 UJCV

CCJOP/74 0^-4 z

MxWov^t SxaW+o^

(IzvaoIcQVazV ive^N-Rj^

,

i-WAju

Qc^a^Cc-- GxxAzy^Ulzi

i&. £)-y. GvowGu •

> •’

)^krvvxCA_^C>c<X z TKjl XJt^kXj^i

CotvecJ ■

\. <»

V

P Qjpjc VO-zOa^O^^ /

I

17^ k. M • A^vxnet^ oAix. Good z

TAxckjeuoN P©^ + y

G^lov^

— SfcDOCN.

1^ • Z) y, R. - Xc ^l^xPc/Hl^l^L .

DiAtcJCT

Vt vUCaX\Cc.v\0Lv MsaaoUa. ^OO G_

Go. <2_£UlcLv R) laa^dGiXo k •' J

No. Q AppAj^P0^ A^oXdua^

/S7o^2- —

<5(3 -

•

i y - G} • N-G.M<D^lZctl-\LvvaL^ •

C^^&AC ^C tVk UWVCA. R/q Uts^(^QJ>Jkb^

(2^) GVzCvcOzvXLA.

zl

/^O^ajlvU!A5

Z^UccaUgzVULM. IJUAXlt'

<2 *2>

G M£bC<. f Qcvv<c

f

1

• ZlvxVt Gx 6] CtA^JLO ix-> / Or* zAA/J

§4<-wG,v.\Jtk

Sni Lc /g ah VAC A ■

■ ^LiaojL

CaJSAS z

^v4>CUa_

pjL-

^VvUk VAzUX

-

' NlAJb ■ QjuJOzvvlt-kX.

Dl/ULUI'O'V 2

dAzCb_O<z

pouoxvc. \ot>u£Xy

Mol2>I , ©Id Q><-' tAA^CK>lAAOO^r)Cvlo<_ VclAoilX

(

- 3>& •

<X^3 ‘

. ^qIq VXAlX^v • \3 t P ’

Mo^/^vva^'vC-

^VaJ01z\J2.4AXJU ‘

Ao-V AUXAXxOc4-VV^.

G IolL- £ck<J

Otp- ^CO-Lvv^j^^x.<xkC F^O I , -J (Xy CLWAV’

’Cm.

lSc lo^e - Il

'

vk

(u_'VA-V> Vu.

L)<u>MLlcyo ia

O

. i ' j^a>a£kC| Xz<

^U\^G\O

tbvI'QP'V —

r~

<c

f

I

2oAAzvaAAas^6v KJ3

TiZo>ckaZ t_o<

>z/>u

JUJ \jQULj C<A-a£xJCE^X“ •

yv^A— c4^ l_v

Ls\l(Xj

<

C^WL

-j

"K—^vvAAW

k

1 ii'ldJd/J

K^yj^n

Ca VaAaaA/>V-]

W") .

(/|(

pb

(TVV^t) w<t^'

\ ir

\^r-ir^'

mJUj \j(U^ok

IvxjAJLv

V-v~VWl\

J^>

~Q^A,x/v~~

_

—*=?

^\a^v~~|<’

~£> XV (£

/AX' 0

t—r-OxA/.

___

'-^>_1£<

cCwiyUy

(^Vvx

A/S7

-—

a

Spc^<^A

T'

rZ 4-^.

Ju? '*■

d^zrr^

K/t^V-xj

M/

(W

■i

a

J

T

—

I

■

1

£._ ||

t*—;

--I

" i

Z

I

J

- -----r

I

t

t

—

I

1

1

■

' ‘ il'

•*—T

-

i’

'

/

.

J

I

■

-

2_

I

—

___ 1

If

—V

-[|

-+

I,

I

• 1/

'

<■

.J

r

j

7^ST_f\/AG)Aftj

k_iA ^7^

.Cg va

UC

'^e>uc<

<x cAaag-4-um

JnrpvAzk

4o

Kx) vw ■ Z-l • -S

cVg\J

____

z>

XA.vx^c(xtxJc\r/

ol

P<xxJ

g^

RJov 9^.

D

No co

V O Luca aJXLu

C€4

Cue

Uj?,XkQAAXQ O

c2

Cca^aD.

^vAP,A-^a}qG^<4

i

<XZJ^(X<JlU<G^x MjxZxl(p<. ^/cULAdxX-A

^jac-^jza^ - V?ajl 40

^P^lowod

X^clgU^qum^

^(AGQC^Uo

p<Cc c4-ca^jzA /

6)>O cyp

cyD

ZcuJ - CO&4-

COvVv^kO k^vC-Cjxd-LOvu

<g)/i)^-vxUxzIZ£d

vzfcuj^

O^ l-l t/A TH

vu<

vX>lajc4<_OiX

CbW

<

UUJJI

—' D CajZjxag^

23^

AJ^^ca^

--) C - o

^CUWAj^ y

GLcdA

<L

u4a. cjLcaoG> <)

WbfcQ>£5VAr<^ A - V Q-

ClihL ^(x^lLvxxa44 ^^poglouj

Jg<_ < k xi J

<xvlZXo

olxA CxLAr&xyvUk

CUCcA

^€^iAAXx{x<4^d ■•

U^V

^Q.aJ-1-C^

'l\W\X) VA^

AyZXLcAzy L£^

_____________

uud4 -

4e-Gy

B dccyi-________ __________________

ZVvC4^<OcZo tc)

2 kLct - JksLa~ 14-£^

/ I Q^cJxiZ^ z

6) V1QlAaa

’aJZ L

60 oc< CaXqjac

Co

O^A^clA/xy^/

^^GekOkoO

XX_.£OAZ

foGtATxCOt

CXaaJ

K>ST

J

GuAXtfc 7 6?UJUJVQLy

A ££ , •

t

JKo UAgXaJva^ Z

A

OcC£ZAJ2_

—______

V c-p-> P<X^RC’LgGL-('-

yPIruyggj j^YCto-AA.

— *

SQ

Pu LLoxj

z Pa^j

-----

'

kjAo-go

i

TouC Cq

0]h|g)

^G)0_i

j.

s

u^c4-G

cxUcGGJ

&)ouy Qiul4

✓AcJOo-v*) 1

.a aa C-^4

^Jmn5ik.4^

AMppoCa

hJu feoecAZI /_______

X)Cc(j> ) t^OcLtj

^VDcO-lCv / C

VAZ\GcXggV LbA-j-AO

.^7 /VazGGP_>G\--\AA,

^7

xS (1 \AA_p L_

/)^xGAZv>x^

w caaloZaxj iJ

txpx

i - ‘

mm

-?- NOI

T^vqa

GaMAG

Jo LtoKutJ

b

rVOa>CGM GAlj

. xO^A Cj^GA^xbi^

&xk

ZGl ■'WCGd o^v

___________ -

(ZZQ^

v

It CGi

Pop

7

T^3 WcMi---- €^7

h^YX

^0 Cajgg^^GjJ

»-WL

v\2.x^

cLg8> CU-A^ <JQ <a_/o

GaaCO vaa^O GU<g<gJ

OOcA^ CO caA

Ca^ujzJ.

-IK', i^j ) <-X- "

<aj vag Cy •

- 'C-Q 4

^CO wqc^aZc

IJ A< Lo&oJ-oc

^toJZu z Toctb fcCoc zfcu^cz __ _ __ _____ _

GjaI’IG A/ — jG^-MCX) C_>^‘CX>A^L^c,-v'<U -

A/’ €.

'Pfc <aaP/

GroboubG uc LccUz' tA/o

f^Z^o^xl l^-|^<eA

'cLacxAj?Z G^ ■

Co V^Vt^Cv,-) v-VA. G cxs/ < o LA>

~rr

----------------------------------------------

O^L^jO

4/Cax

-'-(cu^

~LuoX

<>VLpQzALu-M3 ,

<O<^ X

UpxMS-€v

CD VAZ'vV'X^ V-V t VC/ jgL-Zow

CLATVXXGxAL

<^S&<.cOu4- x fejc/<3

v^^xZgxLuL

LcccC ^>6

LWyL2

v4JUOUU£J

toCjgJUy

y

Ca^xQ^LjUj

0o

./)cv

■ (^X-gL- fa

^XAJ GQL'Uo

UlXALLZj.'

UJOO)

&

4 jxA

4y

^4<^v>clGasJ<\^f

CX'AA.d

I4v. c\! -jX.,

txUuJ-

CoeAJL

J A< "V W'V'V <7

U^^x.J4-6\

(ji®\rt

pP

, ©-o coLL

<Zx^uL/t<Ld •

v'V'^^yO^OCA-Ay

CiQx^\/\j^v\aJ izvx^y

Ze^.O CXJL-CZJ

•tU£>UL

CiQVj,

(0 _____

UXQ^JL

qJ&Lq-

'i-v

/

^PuXla.

JO/-L

EX£XCj-A£2.

4o^

IV^S 7" -

C^jclx

LA

4v\oty .

Uax.4< c

<£ Ovy 4AjL_.

b(Z

Uj^Lc Ul ,

4 Cxi

4^;

^O M uvd

\SQJCC{ __ vstlp^i ■

. "TtxJZ

-UXLJl

^(Xa^^a

CLp^y^zZod-^

^C)’u^\d

Jk£CLl 4-6<

•^-O

CAZA^AAy^4<7 U14W

Lcdaj

Com2Z£

'Hk-

Cc t-^dto4- y 4^ctyAAC£cX.

XA^VtAJLZ / ^-<JLx/v^Zu<a)/o^

^A-kc^)

i

V

</

7

I

kT—-l vc/caa

— LUxboX

■

.

Ciu vA-p-yV-:^ ( c L/L^

T^z GO)

(PcAd

tkrccAvO-O

ogCTgL

v6c tr

cy

Tcvc

VGdebeu

(jxcv^C-

^yyiAzv

XXcAA^<>cJjAjbJo<A^

4o

Ai

O0cv<x

1

<

Gm-

GXcK

Gxaz^ml

uULx'

(Xv U-OxxKd C D■ "X

r5^ UOd

Jb ojcla

^OcqaX

QbxLOJLAAOjJ

teocA^c^

XZaXcX

N ST

XvlCA

liaX T-cgv’XX

4<4<j 4<o

bvc Id

M;

zdX~ U^o

u^o

(X

vA I

€<

IVST

GM C

^'kjuxcAo

ClOtAAft, ■ b-Cb

Cx3mo-’g^-XclX

uk>oZX -

Haji.

b\.

ho 3^ —

.•'UJ lAJ

vz>^LGtcCAA,/Ag .

de J

AqaX

(j/OLA

ex

^

i'XA.Cc/Aci

i/A/VCv^^ Xlaq

VQ^LvajC. '

i/woyP

I

7/

,

JrQ Cva-VQ-

cJJC

UMOA

<

VO Xca^Xxv

cajq u-

taX|

^^TA/X- XA' LyjX

■jh-oJh*

U.:OcxXb

ojlX

AGx -feoxu-'c

g

ex ^pUu^

(X^h^j

^OLlct-o - cy3

3 ‘A\zvc> «4A^ ■

3-

l^ln ^/ FH I y

X)p,c rXK^/l T /^(O PP^,, 6)0 co NJ I P/4IU2

: cgl/4^ Mov£fV)G& %

Q/AT5

/)y. gPT,

'_____________________________

D^. -[-■KJ-bQ , ^°g •____________________________ _

(ADLCOQe ,

VgMug '. ^OVT ■ DGG|££fr

No. p£ VoouNjrecfes

—kX^Jt^ACLA,

AneMD&d

<aCJ.A\

Jpg.

:

Q

g>^ AKjl

KvocvaJ

Lty___________

ppP-Oa_> nazirely

gy

vA.caz<-'Ca>j

<& claz\qOv2_

zv xs^iz'- /< Jo oq

^QaiaqNcl-

^4~a'

J-vX'Q'V

JaAaJJZy VXAm^fi^A

aAxa.J<<A£

^tq

CO-uvu^zlcvl,

cu mgZZ GU A

Lbui *a3-£Lo CK£

tAAXLcrjtcJ

€■

^xCri

eH?rt- Aoo

v^erc^beX. ^iU-^CSL

U'ORW

JL/OO^

^0.411"

bAg,

VoG_z_aaJ-QO<z <■

A-AA ■■tU-£- ^OGMlb

___

S&~ •

-Haq/xJ’^ CcM-g

-

JJc

CZXV4!_ uu_cg_x& c

_

-» AcAcqk jplffw

to

F

COvacLucJ-

u^7-^aX^>4

ujl<4A-

XaPQolZ/__ 1 yrq Cm5uAj£

C^v\d

<!JLc< bexcugjz^v

J cr>

<tu^

’

Ltw

L

©IA

AJaa-x

I

1

Qo^.6^ ^<l£jq^ &jb*=fz

XfOa

^lZzvAClZX-

° .Ott • ThJH • PZaa-vv-Al^

-Cty£_ -3

^(AAAdajsa^'oJdAHx

C Poo i^

<^PT

vZolzaJ 'J-^c

^3nrOC^AVNA>vxJ>,

— _*

-2^)

<aAOC/S

cua ^oLtooux '

— C De-

3- £ZmcoXa^qJ-LL_______ CPoo I <3^________________

Zo^c 620^

■ Oc^o

^otouM

-t.

QLWV

CJplAA.

________________________

itoQ-Ctt 6p

AaJa O^^ot'Qi.

to

bo-

Gonz&acJ .'

— UgjUbcX-t oASUz^yg pLibs '_______________

)

■^C.'uCjUJ-S

' ' ’ bixACl O-AJ6

V^LlAa^J£oaX - <bouLz£

OAzJsuAfcty ob^_

i' Q> A cAgy QcaaJ

^etCAv^IfacdJU

&

>4<gdcU^- u^Luo^a^oo^

t?AyvJz-

'vCUaj><a • aHq

^X«oJbjC

5 -

/\cf c7a7Lc/-M2X/v

Q^OC(i^) .

Vo

Qa.lcx^tGv'W

/ULXCC*

i

I © -i-a

0?. C7J Cclaum

I O± £□ 4 (d + C/

3-

c2 f U +- Q ■>-(_;

$•

Uac, Ajtod

<j

-r- «^CVJCivGQ-O^.

6^4

-4jXA7^

v<

tA/VSL<2U-<ULvVZ^2.

cuc^sdeeJ

QyVA.

GtA

Liy

3700

Cjoa-V

>7xaJo<

TTO?- '3<C Lcx/>G-C©X_»5

|C3LC

co^^-qGa^I

vvxyvxoM.

CM>M2.

QJ^e_SUZ

3

ooUr

/j2xXA-<^po^r>J7o w

■XSLajZ'

°l ^<2

f ot s'-f-a ts

vxLo VXAC

5+&-^L|^

<Qt3-fUf3H

£ • U^lcl dlack^ / w UQP<£XAA^/ksjX^U-\<a41

...

t

<^2

(joLd . -

■Col3

f\/0 tx O-AyLCoJ

G

I ■ -SVo v^AO. c k Ctclve. / Uu©Lmi

'

-

-o2 4

WW^-^yU

<MQAJ2,

QLA.&&P-

^exyoZg.

cxAJcgjy Zo

(OpiActucT

Myowi 3o vi‘UjXj>eo)

XJOOV^V&Ayt

R.O^.fS

d)

COOJ2.

SEI

v

Ola/V^X

AXx_C

4 umoci.

,4.

^ro m

q<ve>tA'7 4o

kJLj

Zct

<£l 0

QUO IZV^CXA

'

J<p^<dXC

Cu\^ou^AAi<0 vt4> C

Cl

<3 S~ /

prozi^-<

<SC^«QJLL.^^

<Lx^

>&4- — Alla-^vcZv

XLej^4<bvv , U.

JzL<^

/) £0£&S

j)r^ gpj ^CG

z

GC<^.

Cl- c

>y. o<£ 4 >

^vo

COaaCJZJL

low

.xLU/LC-g- ~4£-^

C CaZ^UVX^Vx '/<O L<z' ,

o < x

F)

^3b2A^5k^<Ca^Ab k

(j^f

c<^

£©£_££

,

^lcqJ)

-x

b) >,Lo

&> VoLu-A>Lbbgx& ' ^pnotAA

'^.'"‘gL

gyp Uwe 4«Ae

cx tjj-cc tA^

JU:

vOLtL<^ cVLy)I

x

^->vAzvAWttc^

Ccvclr/

J6q

I

1

-/C UjCW

kA_p

Jbe_ s^4r.'Lv\ ,yJ

—^^ZZ”

vAiLOj W'

u\AjaJj^ «

<Cc>cctd

tSOVVM^zvC' VL

Ac

tA/kfZA^A^^X^Z

cvlq-

CLlovuL •

£ CaJ

-<-7

^AjxXxaj:

pye blouiz^

LEPROSY HOUSING PROJECT,

BETHANY COLONY, BAPATLA,

ANDHRA PRADESH, INDIA

Help the Aged

Urban Destitution/Health

AS/IND/122/EJ

OVERSEAS PROJECT INFORMATION

I

i

X

>

§

co

CXJ

’

1

MB

tWr-

L

i

I

K

Leprosy Housing Project, Bethany Colony,

Bapatla, Andhra Pradesh, India

Bethany Colony is a small settlement of leprosy affected families situated

on the outskirts of Bapatla in the state of Andhra Pradesh in Southern

India. The colony was first established in 1933, although it was not

until more recently that it began to take on its present shape of a

village, rather than merely a collection of huts.

Leprosy sufferers were originally drawn to the area by a large leprosy

hospital nearby. Once discharged from the hospital, they wre unable to

return to their own villages as they were ostracised because of their

disease and instead started their own settlement on derelict land next to

the main East Coast railway.

As time has gone by, homeless leprosy sufferers have continued to settle

at Bethany and some of the children of the -original settlers have grown up

as part of the colony. Although many of them do not suffer from leprosy

themselves, they are nevertheless bound by the stigma of the disease and

are unable to settle elsewhere as they are rejected by others.

Leprosy is a contagious disease, although the mode of transmission is not

decisively known. There are several kinds of leprosy which differ in

infectiousness and manifestation. Only a small proportion of people

infected with the leprosy bacilli actually gets the disease. However, for

those who do contract leprosy, regular drug therapy is essential to halt

the progress of the disease, render the patients non-contagious and to

ensure that they do not suffer the familiar progressive deformities.

In order to ensure that the leprosy patients at Bethany are able to

receive the treatment they require, a clinic has been established in the

heart of the community, making it easily accessible to the villagers.

Leprosy patients from the surrounding area also receive treatment at the

clinic. The clinic is managed by the villagers themselves, following

appropriate training in the various skills required. Records are carefully

kept and patients are monitored to ensure regular drug therapy. As there

are no quick, visible results from the drugs, health education is vital to

make certain that leprosy sufferers persevere with their treatment.

continued

1

One of the main problems facing the Bethany villagers is that they

encounter great difficulty in securing employment outside the colony

because of other people’s fear of leprosy,

Instead they have to beg in

order to gain some form of regular income, Groups of villagers travel to

the large towns on begging trips of several weeks, returning to Bethany

when circumstances allow. Prolonged absences from Bethany mean that those

suffering from leprosy may not be able to keep up the regular drug therapy

they require.

In order to try and provide the means of earning a living for the Bethany

villagers as many jobs as possible have been created within the village,

although not sufficient yet to put an end to begging for everyone. There

are limitations on the extent of labour which can be created for people

with leprosy. Manual disabilities resulting from leprosy cover a wide

spectrum and some jobs are therefore not suitable for leprosy patients.

In spite of this, however, all jobs at Bethany are done by the villagers

themselves. These include office work, weaving, shoemaking, animal care,

as well as work in the school, the kitchens and the village shops. Over

100 women are employed in the weaving workshops, working in shifts to make

beautiful bags which are in great demand.

Two Bethany men have recently been appointed as Managers to be trained in

the administration of the colony, and another colony member is to be

trained in social work later in the year.

Jacky Bonney, a British nurse who earlier worked at the nearby hospital,

is the Administrator of the Colony. She wrote in a recent letter to

Help the Aged, ’’The long-term vision of all Bethany’s work being handled

by Bethany people is beginning to take some physical form and I can hope

that a vision may become reality”.

A large number of the people living at Bethany are elderly and many of

them suffer from severe disabilities, such ■as deformed limbs and

blindness, caused by many years of untreated leprosy. They are unable to

travel to the towns to beg because of their disabilities. Those with no

family support are left destitute and have to rely on meals and free

medical aid which are supplied at Bethany for elderly and Infirm people.

A few of the elderly people perform simple tasks in return for the food

and a little pocket money.

The vast majority of the families in Bethany live in very flimsy

dwellings, many of which have encroached on land which belongs to the

railway. Some of the dwellings are situated just two or three metres from

the main Madras to Calcutta railway line. The area is regularly hit by

cyclones which sometimes destroy the Bethany dwellings, leaving the

villagers homeless.

Because of the stigma attached to leprosy, the

villagers have nowhere to seek refuge when their homes are destroyed.

In spite of their depressing situation, there is a great community spirit

amongst the Bethany villagers, who have made repeated attempts to improve

the standard of their housing.

In 1981, after protracted negotiation,

they obtained from the local authority the right to 13 acres of land on

which to build proper houses. However, the land they were given was

unsuitable for the contruction of housing as the ground was very uneven.

continued

2

The Bethany villagers could not afford to have the land levelled

themselves and therefore approached the local government for financial

support, which they managed to secure.

In addition to paying for the land to be levelled, the government also

agreed to contribute towards part of the cost of providing proper housing

for the Bethany villagers, although it has been left up to the villagers

themselves to find the remainder of the money required.

Since the traditional main source of income for the people of Bethany is

from begging and this provides mere subsistence, the villagers are unable

to donate even their time for the labour of building the new housing.

However each family is giving a small sum of money each month towards

labour costs, and those who are able to work are doing so at a lower rate

of pay than imported labour.

In order to make up the remainder of the money needed to pay for the

construction costs of over 300 houses, approaches have been made to

charitable organisations for financial support.

Locally-based charities were unable to help, but Help the Aged has

provided £14,754 and HelpAge India has also agreed to make a sizeable

contribution to the programme.

Although Bethany Colony comprises all age groups, the combination of the

grants from Help the Aged and HelpAge India make up 14% of the full amount

of money required. This is commensurate with the percentage of elderly

people who will benefit from the new housing at Bethany.

For further information, please contact:

Dee Sullivan

Press Officer

May 1987

3

4

DISASTICRS

aBfAHTTEE

Secretariat:

9 Grosvenor Crescent

London SW1X 7EJ

Tel: 01-235 5454

Telex: 918657 BRCS G

Fax: 01-245 6315

IfiHl wa W MMW

INFORMATION SHEET

Six British charities launched a major appeal on June 24 for

victims of war and drought in Mozambique. The Disasters

Emergency Committee is appealing for funds for programmes in

Mozambique and support for refugees from Mozambique in

neighbouring countries.

Background

A tragic combination of war and natural disaster has brought the

people of Mozambique to the edge of catastrophe. They are now

suffering homelessness and destitution on a massive scale. The

Mozambique Government estimates that, of a total population of 14

million, a third of the population is directly affected.

Parts of the north of the country can be reached only by air.

other districts remain inaccessible. The focus of rebel activity

shifts constantly and almost all the country's ten provinces have

been affected.

War has forced people to flee their land and homes leaving crops

untended. The conflict is regarded as part of a larger security

crisis throughout the southern African region. Civilians have

also been the object of attack, as have the country's essential

services, key economic installations and transport networks.

According to UN figures, 484 health posts have been destroyed

since 1982 and safe drinking water is available to only 13% of

the population.

Apart from displaced people within the country, over 460,000

people have crossed into neighbouring states in search of food

and safety.

Increasing numbers of refugees are arriving in

Malawi, many in poor health. Since January more than 7,000

refugees have arrived along the Mazoe river in Zimbabwe.

\CONT.

BRITISH RED CROSS • CAFOD • CHRISTIAN AID - HELP THE AGED • OXFAM - SAVE THE CHILDREN FUND

-2-

Tropical cyclones and drought have also taken their toll on the

country’s resources. The province of Zambezia, once considered

the country’s ’’bread basket” is now one of Mozambique’s most

stricken areas. From 1979-1984 the country was hit by drought

for five years in a row and drought again struck southern

provinces this year. Harvests of maize and rice, staple crops in

Mozambique, have fallen sharply. The collapse of the country’s

market economy has been a disincentive to farmers to produce more

than subsistence needs and has also contributed to the disastrous

drop in food production.

The Country

Mozambique is a large country bordered by Zambia, Malawi,

Tanzania, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe with 2,470 km of

coastline on the Indian Ocean. (See map). The largest city is

the capital, Maputo, (formerly Lourenco Marques) on the coast.

The climate is tropical in the north and sub-tropical in the

south. Mozambique gained independence from Portugal in 1975.

Needs

The Mozambique Government has established a major relief effort

through the Department for the Preventon and Combat of Natural

Disasters (DPCCN) but much more help is needed. The UN Food and

Agriculture Organisation (FAO) conducted a crop assessment

mission in March/April 1987. Their provisional estimate of food

aid required for the year to April 1988 is 674,000 tonnes, plus

tonnes, The UN system has also

other food requirements of 90,000 tonnes.

identified urgent requirements in other essential areas:

★

★

★

Health

Water Supplies

Agriculture

Transport

The UN system set up a special emergency office in Maputo and

earlier this year launched an appeal to governments for US$ 244

million. The British Government has offered £31 million both as

emergency aid (including up to 30,000 tonnes of food) and help

for long term development) through voluntary agencies and

government channels

Disasters Emergency Committee

DEC agencies have been present in Mozambique for a number of

years through international networks, local partners and field

offices. In

T response to the

’

*

‘ ‘

'

‘have stepped up

growing

crisis

they

relief within Mozambique and for refugees over the borders.

The following gives a summary of the work of each agency for the

people of Mozambique, Further details can be obtained from

individual agencies.

\CONT.

-3-

BRITISH RED CROSS, 9 Grosvenor Crescent, London, SW1X 7EJ,

Telephone 01-235-5454

The British Red Cross supports its sister society the Mozambique

Red Cross; both are part of the International Red Cross

movement. Red Cross action in Mozambique includes a prosthetics

programme for war amputees, among them children, and distribution

of relief supplies to 40,000 displaced people in Zambesia and

125,000 people in urban areas. A British Red Cross delegate is

in Mozambique identifying priority needs. The British Red Cross

has chartered a ship to carry medical supplies, food and tents up

the Mozambique coast.

It has already shipped out clothes for

10,000 people. The Red Cross network also helps refugees from

Mozambique in all five neighbouring countries.

CATHOLIC FUND FOR OVERSEAS DEVELOPMENT, 2 Garden Close, Stockwell

Road, London, SW9 9TY, Telephone 01-733-7900.

CAFOD works through Caritas Mozambique, the Catholic Church

agency for relief and development and one of the

longest-established agencies in the country, and is able through

national, regional and locally-based organisations to reach

communities not targeted by the government - for example,

displaced people who have no ration cards. Relief goods are

brought in mainly from Zimbabwe and distributed through Caritas'

local network of parishes. The main recipients are the old, the

sick, children and pregnant and breast-feeding women. CAFOD also

provides funds for programmes to help Mozambican refugees who

have fled to neighbouring countries.

CHRISTIAN AID, 240/250 Ferndale Road, London, SW9 8BH,

Telephone 01-735-5500.

Christian Aid funds the relief and development work of the

Christian Council of Mozambique (CCM) which works with the

Government's Department for the Prevention and Combat of Natural

Disasters (DPCCN) in the provinces of.: Maputo, Gaza, Inhambane,

Manica and Sofala. Food, seeds, tools, blankets and soap are

brought in by road or sea to Maputo and Beira. Through its

sister organisation Christian Care in Zimbabwe, CCM buys food and

other supplies for direct delivery to Tete province. In

co-operation with other Christian Councils and agencies in the

region, CCM is extending its programme to reach other northern

provinces and in June 1987 appealed for USD4.5 million.

Christian Aid contributed £350,000 to these programmes in 1986/87

and will be a major donor to following phases. It has provided

an administrator for six months to work for CCM. Christian Aid

also supports emergency programmes in all the five neighbouring

countries with Mozambican refugees.

\C0NT.

-4-

HELP THE AGED, St. James’ Walk, Farringdon, London, EC1R OBE,

Telephone 01-253-0253

Help the Aged has a Zimbabwe based representative and from

1982-1986 provided drugs for distribution through the Christian

Council of Mozambique.

In 1987 the charity granted £60,000 for

emergency relief - cloth, seeds, pullovers and blankets distributed by the Zimbabwe - Mozambican Friendship Association

(ZIMOFA) and Oxfam. Five thousand blankets have been shipped

from the UK. Help the Aged has also made grants totalling nearly

£40,000 to relief organisations in Zimbabwe, Christian Care and

the Drought Operations Committee, to help elderly Mozambican

refugees. The Charity has also employed an epidemiologist to

study the needs of elderly Mozambicans and identify appropriate

projects for it to support.

OXFAM, 274 Banbury Road, Oxford, 0X2 7DZ, Telephone Oxford (0865)

56777

OXFAM opened a permanent office in Mozambique in 1983 and is

involved in development programmes particularly in the north.

Since 1984 OXFAM has funded substantial relief programmes and in

1986 the escalation of the war led to a sudden increase in the

scale of operations, with £5.3 million allocated (in cash and in

kind) over the first few months of 1987. OXFAM works through the

agencies of the Mozambican Government, particularly the relief

department, and has concentrated on provision of clothes, seeds

and tools to the destitute in the provinces of Zambezia, Niassa

amd Tete. An airlift is being organised (with Norwegian Redd

Barna) to carry urgently needed supplies to remote areas, and a

trucking operation is being organised in association with Band

Aid.

THE SAVE THE CHILDREN FUND, Mary Datchelor House, 17 Grove Lane,

Camberwell, London, SE5 8RD, Telephone 01-703-5400

The Save the Children team of seven expatriates and 20 local

workers has been working in Mozambique for three years.

It has

concentrated its £1.4 million programme of emergency aid in

Zambezia, one of the worst hit provinces. This includes food,

cooking utensils, seeds and farming tools and the transport to

deliver those essentials to displaced families and those willing

to look after lost or orphaned children.

In addition SCF’s

long-term development work, essential to the rebuilding of the

country’s shattered economy, is running at well over £300,000 per

annum.

Save the Children plans to spend money from the emergency appeal

on the running costs of 25 trucks being shipped to Mozambique for

emergency aid.

See over for details of how to make payment.

/CONT.

•

\

If you would like to contribute to the Disasters Emergency

Committee appeal for Mozambique, you may do so in any of the

following ways:

directly at any bank, post office or main building society

- by credit card, by telephoning 01-200-0200

- by sending a cheque or postal order to this address:

Emergency Appeal for Mozambique

PO Box 999

London EC2R 7LD

4

MOZAMBIQUE

*•

TANZANIA

I

I

J

NIASSA ’

ZAMBIA

MALAWI \

Lichinga

f

CABO DELGADO

I

I

I

I

I

I

NAMPULA

Nampula •

’ ZAMBEZM

■

<■

I

-

SOFALA

ZIMBABWE

k. *'-

Beira

<

1

INDIAN OCEAN

MANICA \

"'x'

I

I**-*.

f

.

r

r

! J■

GAZA

v? I ?. INHAMBANE

’

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

fAPUT9;

MAPUTO

'SWAZILAND

■

250

500 km

Help the Aged

THE TIME TO CARE IS NOW

St. James’s Walk London EC1R OBE

Telephone: 01 -253 0253

Telex: 22811 HELPAG G

Patron: HRH The Princess of Wales

■

Help the Aged is a national charity dedicated to

improving the quality of life of elderly people in need

of help in the UK and overseas. We pursue this aim

by raising and granting funds towards community

based projects, housing and overseas aid.

MOZAMBIQUE

The situation in Mozambique continues to worsen as the combined effects of

war and drought drive more people from their homes, forcing many of them

to abandon their livelihoods and all their possessions. Over one-third of

Mozambique’s fourteen million people are severely affected. Elderly

Mozambicans are particularly vulnerable as the family support system on

which they are dependent is breaking down under the effects of this

destabilisation.

Over the past five years Mozambique has suffered a serious economic

decline brought on by years of drought and MNR attacks on key industries,

road and rail transport. Food production and essential services have been

disrupted, resulting in widespread shortages of food, clothing and other

basic items such as soap.

Recent visitors to Mozambique report that guerilla activity is increasing

in the northern provinces of Mozambique. In Tete province it is becoming

very dangerous to travel by road, and villagers in some northern areas are

so terrified of rebel attacks in the night that they walk up to twenty

kilometres to sleep in the nearest towns. There is little food in the

area, and villagers have to eat their cash crops to survive.

Within Mozambique itself there are four million displaced people but no

organised transit camps; those forced to leave their homes head for refuge

in the ’secure’ towns. People with relatives in towns stay with them - in

some cases there are up to three families living in a house built for one.

Of the million or so Mozambican refugees in other countries some 80,000

are in Zimbabwe, 40,000 in camps. A fifth camp is being planned in the

S OU th .

Chairman Peter Bowring

Director General John Mayo OBE

o

R?

x

Company limited by guarantee

Registered in England No. 1263446

Registered Charity No. 272786

Cathy Squire, Help the Aged’s Asssistant Desk Officer for Disaster

Response, returned last weekend from a visit to the Zimbabwe camps for

Mozambicans to assess the situation. She reports that the camps are very

isolated and that conditions are poor. The land may not be used for

farming, and efforts to create an economy through skills training are

severely limited because the locality is poor and there is not a large

market for products. Some refugees work on the local commercial farms for

starvation wages. Refugees who have been in the camps for some time are

relatively well cared for, but the resources are inadequate to cope with

the daily new arrivals. In the northern camp of Mazoe River Bridge up to

forty refugees cross the border daily seeking shelter and security.

Describing the conditions of the new arrivals at Mazoe River Bridge, Cathy

said, ’’The children were very thin and almost all of them had chest

infections, colds and coughs. There were significant numbers of elderly

refugees, and most of them were sitting around listlessly as there is

nothing for them to do. As it is winter the nights are extremely cold with

temperatures approaching zero. In many cases whole families have only a

single blanket and have to sleep on the ground.”

Kamil Piripiri and his wife Fania Sumbereru are both over 65 years of age,

and lived in the Tete province of Mozambique as peasant farmers. Their

two children who are married with families also live in the displaced

people’s camp in Nyamatikiti, northern Zimbabwe. Kamil and Fania left

Tete in 1983 because of drought, hunger and the war. As peasant farmers

they used to grow maize, sorghum and groundnuts. In the camp they grow

tomatoes, paw-paw, and other green vegetables and fruit to supplement

their daily diet of maize porridge (Sadza) with beans or with fish

(Kapenta). They would like to return to Tete when the government of

Mozambique is ready for their resettlement. They would need farming tools

such as a hoe, axe, and spade, and seeds for at least the first year.

They want to live independently of their children who have their own

families to support.

Help the Aged has employed an epidemiologist on a short-term contract to

study the needs of this group and to identify appropriate projects for the

Charity to support. Help the Aged has a representative based in Zimbabwe,

and from 1982 to 1986 provided drugs for distribution through the

Christian Council of Mozambique. In 1987 the Charity has granted £60,000

for emergency relief - cloth, seeds, pullovers and blankets - distributed

by ZIMOFA and Oxfam. 5,000 blankets have been shipped from the UK

directly to the Mozambique Ministry of Health. Help the Aged has also

made grants totalling nearly £40,000 to relief organisations in Zimbabwe,

Christian Care and the Drought Operations Committee, to help elderly

Mozambican refugees with shelter and clothing.

In 1963 the Disasters Emergency Committe (DEC) was set up to provide

British aid agencies with a channel of co-operation for emergency relief

overseas after large-scale disasters. Help the Aged joined the DEC in

1986 as an associate member.

’ * x

xx \ on 24 June 1987 with a four minute

The DEC launched its Mozambique

appeal

broadcast after the BBC ’’ 9 O’clock News’, and the ITN ’10 O’clock News’.

On 25 June the appeal will also be broadcast after Radio 4’s ’World at

One’ programme. The name of the appeal is ’Emergency Appeal for

Mozambique’, and the Post Office and all main banks will accept donations

for it.

2

Help the Aged’s share of the funds will be used for immediate relief

programmes, such as the provision of food, clothing, seeds, soap and

blankets for elderly Mozambicans. The Charity plans to support public

health programmes and hopes to assist income-generating projects for

communities supporting elderly people. Help the Aged will also support

programmes through Mozambique’s Ministry of Health.

For further information, please contact:

Dee Sullivan

Press Officer

24 June 1987

3

I

Help the Aged

THE TIME TO CARE IS NOW

St. James’s Walk London EC1R OBE

Telephone: 01 -253 0253

Telex: 22811 HELPAG G

Patron: HRH The Princess of Wales

£0^Help the Aged is a national charity dedicated to

improving the quality of life of elderly people in need

of help in the UK and overseas. We pursue this aim

by raising and granting funds towards community

based projects, housing and overseas aid.

T:ete

^)3ne

MOZAMBIQUE,.^

Background

Over one-third of Mozambique's fourteen million people are seriously

affected by war and hunger. Ten per cent of the population is over

fifty years old. Many people are destitute, having been forced to flee

their homes, are suffering from malnutrition and have little or no

clothing.

The economic situation in Mozambique has been poor ever since the 1983-4

drought, but the sudden deterioration over the last six months is not

principally due to drought but to the escalation of the South Africanbacked Mozambican National Resistance (MNR) activity. The rebels have

been active mainly in the districts north of the Zambesi river, but

especially in the districts bordering on Malawi. This consists of

widespread attacks against population centres and sabotage. Villagers are

attacked, crops and homes burnt, local government workers, teachers and

health workers killed, and wells poisoned by dumping dead bodies in them.

Villagers are forced to leave their villages and congregate in and around

urban areas. Many have fled to Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Chairman Peter Bowring

Director General John Mayo OBE

I

Company limited by guarantee

Registered in England No. 1263446

Registered Charity No. 272786

MNR guerillas systematically target key food and other industries, and

disrupt road and rail transport with mine and rocket attacks ,

Agriculture employs nearly 85% of the labour force and provides the buik

of exports. The major products are cashew nuts, shrimps, cotton an

maize Industry accounts for only 10% of national income and is

concentrated i^ agriculture processing and textiles, particularly in the

Maputo region. Exports are mainly agricultural, but the largest s^gle

foreign currency earner has been remittances from miners working in South

I^icI? Aspite falls from this source following recent repatriations.

Trade has fallen sharply in recent years, having been severely disrupted

by outdated equipment and by MNR activity destroying the country s

transport system. Agricultural production has also dropped qui e

dramatically since 1981 due to droughts and MNR activity. Food shortag

cause malnutrition, and the health services are unable to respond

adequately

Supplies of many commodities - soap, clothing, seeds an

Sols food, trucks - are scarce and difficult to distribute to areas in

need ’even when available, because of the danger of terrorist attacks

X; XL «« . direct cause ol th. present fn.ln. .nd th.

»

.» many thousands of people having to flee their homes.

for relief agencies operating in Mozambiflue are exacerbated by the fact

that MNR activity is directed at them. The overall situation is further

aggravated by the drought in the southern provinces of Gaza, Inhambane an

Maputo.

Over the past five years Mozambique has suffered a serious economic

d"LSby «uee..=i». y«= »£ drought and flooding, by . lath

“Xt managerial staff and inadtnoate o.plt.l investment and

above all by war and foreign destabilisation. If stabili y

restored the country does have the resources to achieve steady growth.

But any real progress will depend on peace, and the prospects for that in

the immediate future are less than favourable.

*, one million are refugees in

Of the five million people seriously affected,

other countries -- mainly

mainly in

and Zambia

Zambia - and four mill!

in Zimbabwe,

Zimbabwe, Malawi

Malawi and

are displaced within Mozambique, mostly in Sofala Zambesia

Tete^

Manv of the displaced people are living in transit camps. Conditions

in these camps are poor, with most people sleeping in the open and many

suffering from malnutrition and disease.

Help the Aged in Mozambique

representative based in Zimbabwe, and since 1982 has

Help the Aged has a

provided the following assistance for Mozambicans in Mozambique:

1982

15 tonnes of used clothing donated to Ministry of

Health for distribution

1983

Consignment of drugs to Christian Council of

Mozambique for Minsitry of Health

1984

Consignment of drugs to Christian Council of

Mozambique for Ministry of Health

2

1986

Consignment of drugs to Christian Council of

Mozambique for Ministry of Health

The Charity has also assisted displaced Mozambicans in Zimbabwe:

1984

£4,000 to Christian Care for general relief programme

1984

£2,000 towards setting up the Drought Operations

Committe

1984

£12,000 for general relief spent through the Drought

Operations Committee

1984

£20,000 for general relief spent through the Drought

Operations Committee

In 1987, Help the Aged has provided the following:

£10,324 on cloth, sewing kits and blankets purchased in Zimbabwe

to be distributed by the Zimbabwe-Mozambican Friendship

Organisation (ZIMOFA) in Tete

5,000 blankets to be shipped from the UK (about 4,000 already

gone)

£15,076 spent on pullovers purchased in Zimbabwe, which Oxfam

will distribute in Niassa

£10,000 spent on seed for Tete which will be distributed by

ZIMOFA

£20,000 contributed to Oxfam’s seed programme in Niassa

Because of the problems of communication it has been difficult to assess

the numbers of affected elderly people there are. Often they are the

’hidden refugees’ and go unrecorded by other agencies. Help the Aged has

recently sent a representative to Zimbabwe to assess the actual numbers

and situation of elderly Mozambicans.

The problems of distribution to those in need which are caused directly by

MNR acitivites mean that Help the Aged works very closely with other

agencies operating in the area, such as Oxfam and ZIMOFA.

For further information, please contact:

Dee Sullivan

Press Officer

11 June 1987

3

fA17.

Werner & Bower cauiion us that there is often a sting in the tail when pe^.e

advocate community p articipation:

Participation

as a way for

people to gain control

Participation

as a way

to control people

How can we get them A

to do what we want?^/

jr why not through ^

I

'community

i

participation'? We

\ can get international

funding!

/

X

ZnowcanA

/ we ge a \

fairpnce

\

\

,or OU^

grain?

J

Xwhv not join\

/ together, rent \

a^ck.and

transport it

/

to market /

ourselves?,/

I 1 /

/X \JM.

/But what will

lothing-X

the landif we

. owner sa/^. _

stick

^y^together^

Source: Werner and Bower, 1982:6-13

r*“ *

111 ■5

5 5H

d

^ri

Hs- O'l

2^ =5

§

co

o

c

x

ft

-5

rtI?

L

t“

a

~ £0^

s^ ri

<-4n

4^4

■ >e§R

^4s

/^TAy<xJ^xc

Hefi-UTH CEZ-L

dbMMONiiTj

y3b~+j S'WUVa/acv Uzdfcx^

y 2T 6{ctlAc^ kivavucu.u^olct

B A-tx) <\iVco

f^T PIN

fc

O

...

-<-Lin^

ejite j-i=>

Lu-Caj?

^^CWul

Lt»-<_A—

v ofRxL^J

r

4 ii

^'-4-^

--

•

-‘

■

cHc's UXJwac>o

4^C44zA. UxJtC y/^zn^ ’

I"

(jwl'

<?

---k^v^c.

6>Gi_

CpuAtvch*

■'‘■h?

(f^»"

- 9

jr5UA^4

'IkfiAJl <O

4PK

-^kttxVO

(Mie cc

LO

A. Cxd2^AzUXXt

Lvixd (nJtsk)

cHc-

O

I

Tiw. c^M

IAUX

Ac a^l

a^- J- Ia^rvUseJU

Lj4^

Tf^v cu>44

KJ U^x1^

bi>$V C^vzvcl

fo

‘T jS

w-

t „A

(I

^a.

ct^°

Ika-

Backpage

74

WHAT earlier promised toemerge as a stable coalition

the centre and in a few crucial states, it has been

has now started displaying cracks. The current fra

unable to place Article 370, Uniform Civil Code, what

gility ol the National Democratic Alliance owes little

to speak of the temple at Ayodhya on the agenda, even

to the self-activity of the opposition parties; they con

if on the backburner. Its preferences about swadeshi

tinue to be mired in a morass of self-delusion and

stand sidelined in the frenzied search for foreign capi

squabbling. The problem is entirely an internal one.

tal and the rush to meet WTO guidelines; the commit

The BJP, principal partner in the NDA, appears cor

tee to review the Constitution ignores it and makes clear

nered. And contrary to expectations, the strains have

that the basic structure will remain unaltered: even

been created not by a minor partner misbehaving and

national pride has been given a go by, if the supplica

demanding more than its due share, but by its ideologi

tion displayed during the Clinton visit is any indication.

cal fountainhead, the RSS.

None of this can go down well with those who

For nearly a fortnight, instead of debating the

believe that they live by valuesand principles. Worse,

implications of the much touted millennium budget,

those faithful deputed to keep the party on ‘the straight

the Parliament was caught in a logjam. The opposi

and narrow’ themselves seem to have been corrupted

tion stalled all proceeding demanding that the Gujarat

by the lure of power.

government revert its decision allowing government

Is this because the basic relationship between

servants to take part in the activities of the RSS. Though

the BJP and the RSS is altering? If in the past the BJP

the central government pointed out that it had no con

appeared dependant on the RSS, not just for ideologi

stitutional locus standi in the matter; that the RSS was

cal coherence but for dedicated cadres duringelections,

ahighls respected.non-political,soqio-culturalorgani

the situation today seems to have been reversed. The

sation: and the RSS leadership itself clarified that it had

BJP, by reinventing itself, enlarging its social catch

not sought the revokation of the ordinance listing it as

ment and engineering effective coalitions, has grown

a pioscribed organisation tor government servants —

from a 8% party to one garnering close to a quarter of

no one took these clarifications/protestations seriously.

the vote. The ability to dispense patronage and collect

Even the constituents of the NDA - the DMK.

funds has provided it relative autonomy from the RSS.

TDP and Trinamul Congress - made evident their

The RSS, on the other hand, like most ideologi

displeasure. Finally, the government had to relent.

cally rigid cadre-based organisations seems to be fac

Seniorparty functionaries were despatched to Gandhi

ing difficulty in renewing itself. Its ability to attract

nagar to make the state government see reason. The

fresh cadres, particularly from among the ‘suitable’

matter was resolved, but the government lost face.

young remains suspect, despite claims about the phe

More than ever before, the schism between the BJP

nomenal growth of the shakhas. Its efforts at social

and the RSS came to the fore.

engineering by opening up leadership positions to the

It has been evident for some time now that far

OBCs has often boomeranged. Rememberthe ‘revolts’

from beingjubilantabout the BJPcoming topowerfor

of a Kalyan Singh ora Shankersinh Waghela.

the third time, the RSS leadership appears extremely

Yet, it cannot quite afford to fundamentally rock

uncomfortable with the actions and pronouncements

the boat. It is still unlikely that any other regime would

of its ideological and organisational offspring. For

be more favourably disposed to it; the chances of a deal

years, and through some ratherdifficulttimes, the RSS

like the one with Indira Gandhi in 1980 remain low.

has held firm to its worldview. Over time, those sym

So all it can do is to fester in anguish, episodically

pathetic to its Weltanschauung have grown in numbers.

inflicting pinpricks through a Murli Manohar Joshi,

It has even acquired legitimacy in the eyes of the

the flavour of the season. The recent elevation of

modem, urban middle class, more specifically those

K.S. Sudarshan as the Sarsanghchalak makes clear

belonging to the upper caste-class strata. •

that the RSS is unwilling to live with its marginali

It now faces the discomfiting situation of many

sation. If anything, it will seek to reassert itself. Clearly

of its favoured formulations being sacrificed at the

we have interesting, and dangerous, times ahead.

altar of pragmatism and coalition dharma. Despite

being in power (though through a surrogate) both at

Harsh Sethi

Ageing

r

we ourselves may want to revise later in the light of

disagreements or new evidence.

Just as the critique ofessentialism has come full

circle, raising several uncomfortable questions for

social scientists, the emphasis on action research that

has been so much a part of the anthropological criti

que since the 1970s has rebounded on the academy.

The need to promote multi vocality ordialogue within

participant observation or the need to rethink ways in

which anthropologists could help and repay people

with whom they lived and studied led to the promo

tion of advocacy and development anthropology. The

latter had the additional benefit of creating full time

employment as anthropologists promoted themselves

as virtuous ‘bottom up’ members of‘top down’ teams.

Increasingly, however, the idea of proactive

research is being taken away from the universities

and placed within the domain of NGOs and consult

ants. Research that directly feeds into development

projects is seen as action research. From the point of

view ot society or funders, there are many advantages

to research being funded outside universities. For one,

NGOs are often able to identify new issues, when aca

demics are bound by the conventions of their field or

by whatever theory is fashionable at the moment.

Environment comes to mind, for instance, as a good

example of a field where academic research has

piggybacked on activist research. Other examples

include feminist research, philanthropy and urban

planning. NGOs are also often quicker to produce