STREET CHILDREN

Item

- Title

- STREET CHILDREN

- extracted text

-

SDA_RF_CH_8_SUDHA

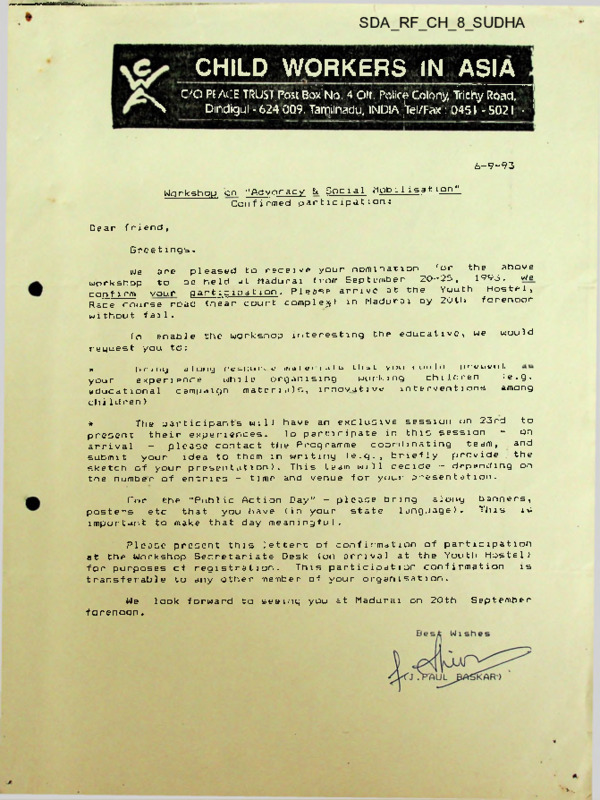

CHILD WORKERS IN ASIA

'•Mi?■•’■■■;••———-i

S

C'O PEACE TRUSr.Post Box No, 4 Oil. Police Colony, Trichy Road,

Dmdigul - 624 009. Tarpilnadu, INDIA flel/Fax : 0451 - 5021 • 1

6-9-93

Workshop on "Advocacy & Soc Lal Hob i 1 isat ion l

Confirmed participation:

Dear friend,

Greetings.

We

are

pleased to receive your nomination

for

the

above

workshop

to

be held at Madurai from September

20-25,

1993.

We

confirm

your

participation. Please arrive at the

Youth

Hostel,

Race course road (near court complejj) in Madurai by 20th

forenoon

wi thout

fail.

To

enable

the workshop

interesting

the

educative,

we

would

request you to:

*

bring

along resour<. e mulei ialu that you uuiiltl

prenwnl

your

experience

while

organising

working

children

(e.g.

educational

campaign

materials, innovative

interventions

among

ch i1dren)

*

The participants will have an exclusive session on 23rd

to

present

their experiences.

To participate in this session

on

arrival

please contact the Programme

coordinating

team,

and

submit

your

idea to them in writing (e.g., briefly

provide

the

sketch of your presentation). This team will decide — depending on

the number of entries - time and venue for your presentation.

For

the "Public Action Day" - please bring

along

posters

etc

that

you have (in your

state

language).

important to make that day meaningful.

banners,

This

is

Please present this lettert of confirmation of participation

at the Workshop Secretariate Desk (on arrival at the Youth Hostel)

for purposes of registration.

This particioation confirmation

is

transferable to any other member of your organisation.

We

forenoon.

look

forward

to seeing

you at Madurai

on 20th

September

COMMUNITY

HEALTH

No, 367 'Srinivasa Nilaya'

Jakkasandra, I Main

I Block, Koramangala

Bangalore-560 034

Phone : 531518

CELL

Ref. No. CHC :

Dear

Greetings from Community Health Cell

!

The two day workshop on Street Children which we conducted on the 6th and

7th July 1993 was the result of a request from REDS (Ragpickers Education

and Development Society)

for 'health input' to rag pickers of their

programmes.

I felt the need to equip myself with some communication

techniques and

teaching methodology,

resource persons were identified accordingly to

teach.

A

suggestion

from

Mrs.Indira

Swaminathan,

educational

psychologist who was one of the resource persons to include others who

are involved with street children in learning some skills along with me,

further led me to organize such a workshc^.

A visit was made to the following agencies whose addresses were available

with CWC to seek their suggestions and expectations for/from the

workshop.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

REDS (Rag Pickers Education and Development Society).

Bosco Yuvodhaya.

YMCA (Young Men Christian Association)

MAYA (Movement for Alternatives and Youth Awareness).

CWC (Concern for Working Children).

The aim of this workshop was to analyse the causes that force a child to

become homeless and to provide some knowldege and skills in tackling

their problems.

Since most of the participants have expressed the need to have regular

follow-up programmes,

it was decided that once a month,

half a day

programme will

be organised and the focus will

be on a particular

issue/problem. Resource persons will be idenfitied and invited according

to the need.

The follow up meetings will be hosted by turns in each one

of the interested agencies working with street children regularly.

We are enclosing a copy of the workshop report for further details.

Your

comments, suggestions, ideas and your participation in strengthening

the

informal networking is highly appreciated. We look

forward

to your

teams' ideas about this aspect as well.

With best wishes and regards.

Yours Sincerely,

S.J.CHANDER

Encl: A copy of the report of the workshop and list of participants and

------------- fehc-ir addresses-:---------------■---------—- ----------------------------------------------------------------------------'Society for Community Health Awareness, Research and Action'

Registered under the Karnataka Societies Registration Act 17 of 1960, S. No. 44/91-92

Regd. Office: No. 326, V Main I Block, Koramangala, Bangalore ■ 560 034

CIA «•!

■

/fy/h'

^Vbtccyj a.<J'(

(&,

/?<zj fLCcZcj^

^.A_dC

i^aA-

c/-

£-f

£

y^..a<y^^<^y.....'

:

y

yy^y^^y_yS.

T--------------------

£ - i/L ■ Sin^n. •

ictr^Ai r,

;

])C-\r^lc^xr>^yih

V-

SVcaa/

Uv’^...^e

l~> a-ta^zi h'^ ~ sfic Ooi i

/1//wZ?vwO

r

i

.., _..

■

C- W ' C •

'■.

C/^e

^VrAbtvVc-^

pJ.—----zy/^^'VV>T/*<

Peace

8-10--93

Dear Sir/Madam,

Greetings.

We are happy to send you the participant list

of

Advocacy

and Social Mobilisation

workshop

at

Madurai between 20-25th September 1993.

Thank

you

"for

your

participation

in

the

workshop and the Public Action Day.

Hope you could

take up Advocacy as a part of your work.

We

would

be happy if you could let us know how you are going

to

use the Advocacy methods in your activities

to

eliminate child labour.

Public Action Day

Regards.

Yours sincerely

J . PAUL.BASKAR

□n behalf\of Organising

Team

Off

Police

Colony,

Trichy ,

Road,

D1NDIGUL

624

009

TAMIL

NADU

INDIA

Grams ■

Peace

Phone :

91-451-5021

Fax

91-451-5282

CHILD WORKERS

South

IN ASIA

India Workshop on Advocacy and Soo i a1 Mob i1isat ion,

September 20-25, 1993

Name

Madurai

Organ isat ion/Address

Tel/Fax No

Nature of

Visit

Participant

1.

S.

Manmatha Devi

Child Relief & You

46, Poes Road,

Tenampet, Madras-18

451548

2.

G.

Shantha

DAWN, 48,Dharkar st

Virudhunagar 626 001

5303

•

A.

Aruldoss

Bosco Institute of

Social Work,

Tiruppattur 635 601

4.

K.

C.

Anan th

Selvakumar

MNEC,, 34-A Meyyappan

II st, Madurai-16

34185

■■

5.

S.J.

Chander

Community Health Cell

326, Vth Main I Block

Koramangali, Blore-34

531518

••

6.

S.

7.

Muniyammal

K. Ponnusamy

8.

G.

K.

Mahalakshmi

Naien

CSED, Muthuchettipalayam

33V2, Vailuvar .street

Avinashi 638 654

9.

S.

Gnanaseelan

GUARDIAN, 2/92 Pudunagar

(Pol Thirumangalam 626709

10.

D.

Deva Anbu

Action for Child labour

3A,! CGE colony, Madras-41

11 .

Vinod Furtado

1,2.

D.

C.

13.

M.

•

Shunmugakani

i

20788 '

PRESS Trust

Shanmuga Sigamani nagar

Kovilpatti 627 701

PAPER, R.S. Va'iyampatti

Trichy Dist-621 315

11

PRERANA 1-5-139 Himagiri

complex T.B. Road, Raichur

584101, Andhra Pradesh

5125

11

Ganesan

Amalraj

RECD, Chatrapatty\

Sattur 626 203

884

>■

Antony Durairaj

TSSS,

Palayamkottai

627 002

72082

;?es

George

Pollachi

Caroline Wesley

The concerned for Working

Sreelatha Yegnweswar Children, 26/1 Vanthappa

Gardens, HAC II State

Deopanahal1i, Bangalore

16

Arasappan

Basco Antony

18.

572111/575258

30, Arunodhaya Arathoon

Salai, Madras-13

552557

Mythiri Serva Sava Samithi

94, Farm House 3rd Main st

7th cross Domlus Layout, Blore

561647

HOPE,

E—29 R.M.Colony,

Dindigul

RECO, 44, Chola Real Estate

Thrukokarnam Post, Pudukkotai'

Muthukumar

CRESENT,

P.O.Box 89,Pudukkottai

Santhi Nilayam, 9A Chairman

Amirtharaj st, East Shanmugapuram, Vilupuram 605602

S

Syed Mohideen

Society for Rural Service

Kuddiyatham road

Palamner Po

Chitoor 517408

!409

Victor Sahayaraj

REDS, 62A Sacr'ed Heart churi

compound, Bangalore 560 025

569209

LEAD, 8, I street, Sri rama

puram, Royar thoppu,Srirangam

62521

Nandakumar

25

Savarimuthu

PEACE Trust,

Trichy road,

Ramakrishnan

John Lawrance

POWER Society,

Asupathy raja

PEACE Trust

Babu

POLE

M.

26

28

R

D

Near Police colony

Dindigul—624 009

Periyar nagar Puthur

10

!9

Lakshm:

Kalpatty 605202

Plot No:5:

PARD

Madurai

55489

M.

C.

Lourdusamy

Pushpanathan

Dr.Ambedkar Service Society

□ ttump attu, S.Arcot 604 205

32.

K.

Raj end ran

CENTREDA,

33.

C. Selvin Theophlcus GKN, Malligai cross st

S. Jahsuva

Thendral nagar, Gomathipuram

C. Jeyabalan

Melamadai, Madurai

K. Raman

30.

R.

Padma mani

Nilakkottai

Progress Trust, 41 North Veli

st, III Floor, Madurai-1

35.

M.S.

Murugan

IRDT, 5D-1,Sudamani

Dharmapuri 636 701

36.

E.H.

Khanmajles

Under Previlage Children's

Education Programm, Plot 2&3

Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh

8010147801015

37.

Bindu Abraham

K. Kavitha

YUVA, 53/2 Narepark Municipal

School, Opp.to Narepark garden

Panel, Bombay

4143498,F:3889811

38.

Madhavi

UNICEF, 20,

Madras 18

450332/453437

39.

L. C.

Symon

ICCW, CLAP 182, North car st

Srivi11iputhur 626 125

40.

S.R. Bharathadevi

S. Logaguru

Women's wing, T.N.Consumer

Protection Counci 1,’ Madurai

41.

Mrs.

PREETHI 28,

Madurai-10

Ashok

Karikalan

st

Chitaranjan

82/208

road

West Ponnagaram

42.

P.

Ganapathi

20G, ;Kasthuri Nagar,

43.

A.

Perianayaga samy

Jeeva .Jothi, 2/88 South st

Poralur Post, Kai1imandayam

624 616 Anna Dist

24172

Melur

44.

S.

Che 11apandian

Chetana Vikas,

45.

K.

Aloyius Peter

Centre Radar, Arulanandar

College, Karumathur

(871)208

46.

K.

Pushpa

Equations, 168, Sth Main

Near Indiranagar club, Blore

582313

47.

G.

Vi jaya Kumar

Peoples Action for Creative

Jagadev Poor, Medak, A.P

Madurai

44791

48.

R.

49.

B.M.

Karthik

Kutty

50.

Bijaya Sainju

51.

Rosaline

52.

\

Binu Thomas

53.

T.

Y.

^^4.

Costa

Anbukarasi

Sakila Banu

Asha Krishnakumar

RATS Trust, 270-C Railway

colony, Madurai-1

Pakistan

Institute

Child Workers

of

Labour

in Nepal

270336

Commission for Justice & Peace

Box 5, Dhaka-1000 Bangladesh

417936

F.834993

Action Aid,

Bangalore-1

586682

MISS,

3 Rest House

road

Madurai-2

Frontline, The Hindu

Kasturi Bldgs, Mount

Madras-2

road

845435

835067

55.

C.

Devaram John

57.

E.

Vellaichamy

CHERU, Ve1labommanpatty

Anna Dist

6536

58.

J.

P.

Helen Manoharan

Manoharan

34A,

34185

59.

Ff.S.

60.

Jalaldin

CHILD No. 17, Jalan P-js

9/16 Banar Sunway 46150

Petal,ing Jaya, Selngor Malaysia

7363997

61.

Thaneeya Runcharden

CWA Secretariat 10/68 Tawanrta

House, Viphavadirenesit,

Bangkok, Thailand

513-2498

62.

Mohammed Farid

SAMIN Foundation PB 1230

Yogyakarta 55012, Indonesia

63.

S.

Aravalli

Gandhian Order Trust

1, New Pankajam Colony,

64.

A.

Rajagopal

41,

65.

Dr.M.

Rengan

•

Udayakumar

GKN,

■■

Madurai—20

SPEECH, 14,

Thirupalai,

RECD,

••

41977

56.

Abraham Renold

Observer

4557009

4552137

4548115

Jeyaraja Illam

Madurai-4

Meyyappan

list Madurai-16

Chatrapatty,

North Veli st,

Satur

42855

884

■■

t

,

••

Madurai

Madurai-1

Dept.of Eco.Tagore Arts Col

Pondicherry 8

i

i

„■

'

Andheri Hilfe-S.I

Sangi1xandapuram,

Office

TriChy

67.

Fr.Kulandai

68.

Kailash

69.

A.Joseph Raj

A.S.J. Aloysius

Socio Educational Trust

29B, Thattarmalai street,

Chengalput.

27295

70.

Ansalem Rosario

Mythri Sarva Seva Samiti

Bangalore

561657

71 .

Kavitha Rathna

Lakshapath i

The Concerned for Working

Children, Bangalore

572111

575258

Raj

Sathyarthi

SACCS, Mukti Ashram,

Ibrahimpur, Delhi-36

72.

S.

Alexander

REDS,

73.

V.

Surest

458, 8th South Cross st

Sri Kabaleeswarar nagar

Meelankarai, Madras 600 041

4926324

74.

Ossie

Human Rights Advocacy

Research Foundation, 5 Morison

IV st, Alandur, Madras 16

2349640

75 .

K.B.

Equations, 168, 8th Main, Near

Indiranagar Club, Bangalore

582313

76.

Suresh Dharma

Block Theatre,

Madras

,

450931

77.

Dr.Vidhyasagar

4-IIDS, 79, 11 Mkin.Road,

Gandhi nagar, Madras—20

78.

Prof.J eyaprakasam

Dept.of Gandhi an Thought

Madurai Kamaraj University

Madqrai

79.

Dr.L.S.

80.

Thavath i ru.

Kundrakudi Adigalar

81.

A.

G.

P.

Ravi

Amalraj

Rengaraj

Peace

Trust,

82.

R.

V.

Jeyapandian

Sundararagavan

MNEC,

Madurai

Fernandes

Gopinath

Gandhidoss

P.B.No:15,

Sivagangai,

177 TTK Road

.

Resource

person

2449

412589

680044

Dept.of Social Work, Bangalore

University, P.K.Block, Palate

road, Bangalore 560 009

Resource

Guest

Thiruvannamalai Adheenam

Kundrakudi 623 206

Dindigul

16

5021

34185

Volunteer

83.

G. Mohammed Hussain

Andrews

Mrs. Merlyn

L. Lawrence

W. Albert

84.

M.

Muruga Periyar

GKN,

Madurai-20

M.I.S.S Madurai-2

85.

0.

Nandakumar

Chetana Vikas,

Madurai

86.

S.

Thomas

Centre for Peoples Movement

J 146 MMDA Colony Arumbakkam

Madras 6

■87.

"

V.

S.

Ch inniah

Thangavel

ROSE Lanthakottai,

Anna Dt 624 420

88.

S. Sekar

Alaghu Bharathi

RATS Trust 270/C Railway colony

Madurai-1

89.

J.

Peace Trust,

Trichy Road,

90.

M.S.

91.

T.

92.

C.

Paul

Baskar

Kadachenandal

44791

"

Vadugavur>Tk

Near Police Colony 5021

Dindigul-624 009

Organising

Team .

Asian Institute of Technology

GPO Box 2754, Bangkok 10501,

Thai 1 and

"

Rajkumar

The International Child care

Trust, "Bidisha", Anandagiri

6th street, Kodaikanal.

"

Kumaran

VENTURE, 1/19A, Anna Nagar

Narthamalai 622 101

Pudukkottai Dist

Shivakumar

PARD,

Rajasekaran

P.B.87,

Madurai 20

CH

Advocacy and Social Mobilisation

Towards

Elimination of Child Labour

A Brief Note on the

Issues mill Circumstances

Chihl Workers in Asin

Madurai, September 20 - 25,1993.

«* Nature of the Problem

Causes of Child Labour

< The Logic of Employing Children

Magnitude of Child Labour Incidence

»«♦ Working Children and Their Occupation

«* Some of the Main Points of Concern

u*

a.

Law on Employment of Children

b.

Hazardous Employment

c.

Wage Component

d.

Ltn iversulising Education

e.

Export - oriented Industrialisation and Competitive Devaluation of Labour

f.

Children Payingfor the National Debts

Workshop on Advocacy

Nature of the Problem

In the pre-industrial agricultural society of India, children worked as helpers and learners in hereditarily

determined family occupations under the benign supervision of adult family members. The workplace was an

extension of the home, and work was characterised by personal and informal relationships.

The social scenario, changed with the advent of industrialisation and urbanisation. The child had to workas an individual person either under an employer or independently without employing the benevolent

protection of his/her guardian. His/her work place is different from his/her home. He/she is exposed to

various kinds of health hazards emanating from the extensive use of chemicals and poisonous substances in

industries and the pollutants discharged by them. His/her work hours of work stretched long but earnings were

meagre. In most instances, employers maltreated and exploited him/her unscrupulously. His/her work

environment thus endangered his/her physical health and mental growth. In our discussions we arc largely

concerned with the economic exploitation of children and the consequences thereof.

Causes of Child Labour

Chronic poverty is responsible for the prevalence and perpetuation of child labour now. Nearly half of

India's population subsists below poverty line. In the countryside, the distribution of land is iniquitous. The

lower 50 per cent of the households own only 4 per cent of the land. As many as one-third of the rural

households are agricultural tenants and another one- third are agricultural coolies. In the cities, more than 40 per

cent of the population live in deplorable neighbourhood conditions and do not have access to regular income

earning opportunities. In such situations many families "push" their children to earn some income. The income

accuring from child labour may be a pittance but it plays a crucial role in saving the family from starvation or a

shipwreck. The spiralling inflation and rocketing prices of essential commodities have exacerbated the struggle

for survival to ultimate limits. Therefore, child labour amongst poor families is a part of the survival strategy

evolved by them.

The Logic of Employing Children

For a number of tasks, employers prefer children to adults. Children can be put on non-status, even

demanding jobs without much difficulty. Children are more active, agile and quick and feel less tired in certain

tasks. They can climb up and down staircases of multi-storeyed buildings several times during the day carrying

tea and snacks for employees of offices located in these buildings. They are also better candidates for tasks of

helpers in a grocer's shop or an auto-garage. Employers find children more amenable to discipline and control.

Children are cheaper to buy. The adaptive capabilities of children arc much superior to those of adults. Child

workers are not organised on lines of trade unions which can militantly fight for their cause. Then there are

crafts [zari/brocade work orcarpet weaving] in which highest degree of sophistication and excellence cannot be

achieved unless learning is initiated in childhood itself. Unless the fingers were trained at a very early age, their

adaptation later would be difficult.

Magnitude of Child Labour Incidence

A precise estimate of the overall magnitude of child labour in India is admittedly difficult on account of

the predominance of the informal and unorganised nature of the labour market, and also due to multiplicity of

concepts, methods of measures and the sources of data. However, it is conceded that India has the largest

number of world's working children of which South India has substantial proportion of them.

Based on the 1991 Census, an estimated figure of working children in the age group of 14 years and below,

is about 20.5 millions and it comprises about 2 per cent of the total population of the country. So many children

labour despite the Constitutional prohibition of employment of children below the age of 14 years and the

Constitutional mandate to have compulsory education of children upto 14 years. Thus, every third household in

India has a working child, every fourth child in the age group of 5-14 is employed and over 20 per cent of the

country's GNP is contributed by child labour. Some of the actively involved agencies like NGOs or UNICEF

claim that between 44 and 60 million children might be working in various sectors of the economy 1

The incidence of child labour is reportedly highest in Andhra Pradesh where it accounts for about 9 per

cent of the total labour force in the state. In fact, Andhra Pradesh accounts for about 16.2 per cent of the total

child workers in the country. Working children were largely found in lime- quarrying and various other

construction related activities and agriculture. Comparatively, less number of children were employed in the

industrial enterprises.

Tamil Nadu occupies the second position wherein 5 per cent of the total labour force were children, and

the incidence of child labour varies across districts of the state, in 1981, North Arcot, Salem and Madurai districts

accounted for a higher proportion [about 10 per cent of the total labour force] of child workers in the state; the

proportion was very low [less than 2 per cent] in Madras, Nilgiris and Pudukottai districts.

However, a recent study [1992] indicated that the incidence of child labour has grown substantially in all

the districts of Tamil Nadu apart from "traditional child labour areas" like Madurai, Sivakasi, Salem and North

Arcot. For instance the establishment of the "gem park" in Trichirapalll has proved to be attractive for many

entrepreneurs in the region; now, artificial gem cutting units have lured about 12,000 children to go for work in

artificial gem cutting units located in and around Trichirapalli and Pudukottai areas.

In Karnataka, the incidence of child labour is slowly becoming visible, and drawing the attention of the

policy makers. Though comparatively modest incidence of child labour in the state, a recent survey (1990)

indicated that contrary trend; it is now believed that about 4 per cent of labour force comprised of children below

14 years. These working children were largely found in the rapidly growing urban areas like Bangalore, HubliDharwad and Mysore wherein they eke out living in occupations such as ragpicking, hotel/petrol station boys,

zari/silk weaving [and sericulture] and various other manual labour tasks.

Working Children and Their Occupation

To derive a better understanding of the dynamics of child labour a quick review of some of the

occupations in which children are employed is discussed here. This section is only an example of the scenario

and the circumstances that are steadily evolving around us.

In plantations, child employment is a part of the family labour as a group. Parents do the main field work

and children mostly assist them, in plucking leaves, coffee berries or collecting latex or they do secondary jobs

such as weeding, spreading fertiliser/pesticides, take of nurseries etc. With their nimble fingers, many children

turn out as much work as adults.

A similar situation prevails in mining, quarrying and construction works where "family labour" is

encouraged through piece-rate system.

One of the main industries in which child labour is prevalent is bidi manufacturing in which children roll

bidies and assist the adult workers by cleaning and cutting the leaf and closing the ends. Generally, bidi rolling

is pursued as "home-based economic activity" in which women and children are engaged.

Employers do not pay adult wages to children arguing that the products do not come upto the required

standard of quality. There was sufficient indication to suspect a high incidence of tuberculosis among the bidi

workers and this, according to many medical studies, was starting at a tender age, very long hours of work,

excessive overcrowding and the peculiar posture during work which was an impediment to the healthy

development of the lungs of children.

In glass bangle industrial units children [mostly women and girls] are employed to join ends, sorting,

heating, engraving and packing. The decoration of bangles using liquid gold is extremely strenuous as they have

to work near a furnace. Cases of asthama and bronchitis or eye diseases are many.

-2-

The carpet weaving units utilise child workforce behind giant looms wherein they feverishly pick, warp

up wool as chief craftsman give instruction. The air is thick with particles of cotton fluffs and wool, and 40 per

cent of the children are asthmatic or have primary tuberculosis.

The situation is similar in handloom or silk weaving industry wherein the looms are set in dark and dingy

rooms. For long hours children sit in crouched positions thus affecting adversely their physical growth and

development.

Mining, quarrying, stone polishing or gem cutting units of various precious stones employ about 60,000

children in South India, all of whom work in miserable hovels. The work is done through middle men who

procure children for a pittance. The young gem cutters soon develop eye defects. Children are ruthlessly

retrenched with the first early signs of eye fatigue. Many are jobless in their teens.

In several write ups in newspapers and periodicals the position of children employed in the match and fire

works industry in Sivakasi and neighbourhood has been very much highlighted. It is estimated that about 60,000

children are employed in this area. There is an organised system to arrange for their transport from the

neighbouring villages and to bring them to the factory sites. The children have to leave their homes in the early

hours of the morning to catch the factory bus. An incredibly large number of them are jampacked into

ramshackle buses. Children actually start work from 7 in the morning and continue till 6 In the evening. In

between there Is a short noon break when most of them’ have their tiffins which they bring from home. Bedcause

the wages are determined on the basis of piece-rates fhey all work feverishly to maximise output. This results in

a complete neglect of their own requirements and many of the children were found rather frail and anaemic in

their looks. There is no medical assistance available to them. Despite their best efforts, the wages earned are low.

In recent times, we observe many children working in industrial units like machine tools, lathe/drilling

units and repair shops. Quite a few of them had joined the units as informal apprentices without wages but were

entitled to some "benefits'' like lunch and tea/coffee. They also repair old batteries and electrical appliances or

work in foundaries. Their service is generally procured by a contractor who obviously will not cover them under

any of the labour welfare schemes or ESI facilities.

Countless number of children are working in the unorganised and self- employed sectors in urban areas as

domestics, workers in hotels, restaurants, canteens, wayside tea stalls, shops and establishments, helpers in

service stations and repair shops, vendors, hawkers, newspaper sellers, shoe-shiners, ragpickers, collies and

casual labourers. Children in construction work are often hired along with their parents. With changing

worksites, families always have to be contened with make-shift housing structures. The work demands the

hardest physical labour which stunts the growth of the child and holds no promise or prospects for him/her.

The condition of children working in tea stalls and wayside restaurants is mostly bad. Most of these small,

improvised structures made of loose stones, bricks, mud, tin sheets, and gunny bags and cluttered with

paraphernalia leaving hardly any space for movement. With long working hours and meagre wage, the child

has most of the time to work and rest in the open, exposed to the vagaries of weather. He looks unclean, ill-clad

and barefooted.

Perhaps the most dangerous, demeaning and destructive self-worth is the job of scrap collectors or

ragpickers. The nature of their work and work environment is absolutely unhygienic. These children are largely

from dalit families residing in slums or abandoned in the streets. They develop several kinds of skin diseases;

while collecting rusted pieces, they may receive cuts on their on their bodies and become susceptible to tetanus.

Their contribution to the "recycling industry" is fairly large.

Our quick survey of the circumstances in which child labour persists indicate that there were practically no

enforcement of the legislations and no prosecutions in most parts of the country of existing laws pertaining to

working children. We also observe that the present institutional frameworks that attempt to ensure collective

bargaining in respect of working children are weak and inadequate. In areas where child labour is largely

observed [i.e., Sivakasi] we are convinced that a few token prosecutions were made periodically only to assuage

the genera! sensitivity of the people to the situation. But in all such prosecutions, the accused were Jet off with

very petty fines. This kind of situation clearly makes a mockery of law.

The recent incidences of "child trafficking" and "child bondage and slavery" remain new sources of

economic exploitation of children. It is now well-known fact that all sorts of labour "scouts" have sprung up with

the induction of increasing numbers of outside child labour. A number of children are "purchased/procured" by

unscrupulous middlemen and sold as per official affirmation, to equally unscrupulous exploiters of children.

In recent times, we have also come across instances of child bondage and slavery. One of the basic

condition of bondage is self-evident. Working children live in clusters and their parents had taken small loans

that are recoverable out of the wages of the children. These are all obviously "survival loans" yet this

transaction binds a child to the employer till the loan is "settled".

Some of the Main Points of Concern

Over the years, our concern on "child labour" has varied from rehabilitation, education to total abolition of

child labour through legislative measures. One finds supporters for legalisation of child labour as well as total

elimination of it. No one position [without understanding the socio-economic realities] is tenable. Many now

agree that a variety of intervention are necessary to challenge child labour practices. The proposed interventions

vary from rehabilitation, giving adult wages [minimum wages] to children, universalising non-formal education

for those non-schooling children, strengthening educational institutions, enrolment campaigns amongst the poor

households, lobbying for a total abolition of child labour and providing more "teeth" to the implementation

machinery of the state. These efforts require constant initiatives from all concerned and the NGOs have a

substantial role in such advocacy and social mobilisation measures.

a

Law on Employment of Children

The legislative endeavours to regulate child labour in India were almost negligible. The earliest piece of

legislation was the statutory protection of child worker in India was the Indian Factories Act, 1881. Probably the

colonial rulers were familiar with dealing in child exploitation during the industrial revolution in their home

country. They proceeded to prohibit children below 17 years to work in a factory employing 100 or more

workers. It also prohibited the employment of children above 7 years not to work for more than 9 hours a day

[with weekly holidays]. After about 10 years this legislation was revised allowing statutory protection to the

children was made to advance by increasing the minimum age to 9 years, restricting the hours of work to

maximum of 7 hours a day, and prohibiting night work between 8 pm and 5 am. Since then a number of

legislations were specifically made to cover the rights of the children as workers.

Obviously the experience of the last fifty years convince us that the provisions contained in the

Constitution as well as various Acts have not been complied with. Then we confront some of the issues : will

total ban on child labour work - will that be progressive or retrogressive ? Is the unemployment or

undermeployment among adults result directly from such a large working child population ? with raising adult

unemployment the family subsistence is very fragile, and therefore, children are forced to work and earn a

livelihood 7 why did we fail to implement universalisation of education despite a constitutional guarantee for it?

Instead of concentrating in the improvement of the situation in the area of payment of minimum wages

and implementing the constitutional duty to universalise education, we see various agencies and organisations

succumbing to the economic pressure and helplessness experienced in the enforcement of prohibitory provisions

in the employment of children and lower the age of the child further down to 14 years - this move lacks any

adequate justification!

b

Hazardous Employment

Whilst the legalistic arguments and preventive measures remain, one also observes the hazardous

circumstances in which children are employed. The working conditions are not only hazardous but retard their

growth and development, and highly susceptible to chronic diseases like tuberculosis, asthma, bronchitis etc.

Thus, there is an inherent risk involved with a particular kind of occupation and this is not known to the working

child; as the tender age invites them to "play" and lead a normal life meant for a child - the working child cannot

be prevented from playing with explosive chemicals, glass, electricity or gases.

Now a days, children are sold to be engaged in immoral occupations like prostitution [or even begging] or

any other criminal activity. In such situations, the child learns to "survive" rather than picking up a skill.

c

Wage Component

One of the important reasons for the increasing employment of children in various occupations is that it is

the cheapest. In the absence of any strict legislative provision for payment of full minimum wages to children

and its implementation, their condition is becoming worse day by day. Most of the employers do not maintain

proper rolls of the children employed in the establishment as required under the provisions of the Factories Act

and the Employment of Children's Act. If they have, it is for the limited use to take note of the employees who

have reported for the work and of the quantum of production for the day. There is no register of workers. Thus,

enforcement of any legislation becomes totally difficult.

d

Universalising Education

The various pitfalls of the present educational system has tacitly supported the prevalence of child labour

practices. A meaningful educational pattern that would allow families to take care of economic needs [to

overcome the current poor conditions] and give functional education to the children is necessary. A fall in the

enrolment of the children at the primary school level indicates our government's disinclination to invest in

educational infrastructure and provisions.

e

Export-oriented Industrialisation and

Competitive Devaluation of Labour

The restructuring of the state, the worsening effects of economic crisis e.g., emphasis on export-oriented

industrialisation that would make Indian produces globally competitive; to achieve this manufacturers tend to

reduce wages and prefer children for meeting export prices. This is commonly known as "competitive

devaluation of labour". Many of the export commodities like carpets, silk, artificial precious stones require

"nimble fingers" for production; therefore, children are enticed into the labour market.

f

Children Paying for the National Debts

Here are some points for further inquiry and analysis.

India is now paying huge sums to service its debts. One result is that state spending on health, nutrition

and education has been cut back over the years. This means that the heaviest burden of debt crisis is falling on

the bodies and shoulders of children - and this falls mostly on poor children. Children have also been paying in

our country not only for the loss of opportunity to be educated - but also on nutrition, health and even in

minimum wages when they work [as wages tend to decrease at times of economic crisis]. But faced with many

short-term problems and pressures, governments are finding it difficult to find the resources.

The increasing military spending and expenses for purposes of "security" has risen multi-fold since early

1980s. These expenses together account more than the state budget for education, health and child development

taken together 1

In the long-term, no one seriously doubts the priority of investing in schools. It is well established, for

example, that education is strongly associated with lower child death rates, lower birth rates, better health and

nutrition, and higher income earning opportunities. In addition, economic returns from education are higher

than from most other kinds of investment. Yet we find reluctance on the part of the government to consider

universalising education as a priority.

-5-

The central thesis of our understanding is that children should be protected from the worst consequences

of the adult world's excesses and mistakes, whether we are talking about violence or war or about the cumulative

effects of economic mismanagement. Vulnerable sections like children should be protected by shifting the

balance of spending in their favour. Politically this is not an easy task to engineer a shift from in priorities from

urban to rural, elite facilities like airlines to rural bus routes, from prestigious educational institutes to humble

primary schools ....

The prospects for progress will remain gloomy while more than a quarter of our GNP are spent in debt

repayments instead of being invested in growth. There is also a growing recognition that more dramatic and

decisive action on debt is in the interests of our nation.

Without such action the crisis of non-schooled children, working children [a direct consequence of

non-schooling] will shadow over us in the future years to come I!

Workshop on Advocacy

In the past decade NGOs have attempted to communicate effectively with other members of the society,

state institutions and party organisations; however, they have experienced difficulties to initiate a dialogue and

meaningful confrontation. This advocacy and communication skill needs to developed to effectively challenge

child labour issues at various levels of the society (e.g„ policy-makers, industry, neighbourhood or household).

After more than a decade of grassroot level initiatives NGOs now explicitly recognise the need for a larger

advocacy to : (a) gain better insights into the macro issues that affect child labour situation; and (b) effectively

strengthen advocacy efforts at local and regional levels.

It is in this context that the workshop on "advocacy and social mobilisation" Is organised by the Thailand

based group "Child Workers in Asia” [CWA] at Madurai from September 20-25,1993. This workshop is organised

after a scries of preparatory meetings at sub-regional levels, and CWA will share its experiences in other nations.

What is Advocacy and Social Mobilisation ?

It is about motivating people to achieve their goals or a series of common societal goals. It is to facilitate a

large number of people to participate; this initiative is self-supporting. By analogy, it is a multi-level approach

attempting to capture the attention and resources of an entire society and enlists its active support at all levels;

the policy and decision-makers, the service providers, the media and education sectors, key non-government

partners in the programme areas, the community and all other concern individuals.

It is believed that changes can be induced by : (a) compulsory forces (e.g., policy changes, effective

implementation); (b) voluntary decisions stimulated by the provision of incentives, informationm, education and

skill training; and through awareness campaign to facilitate people to see their own situation in new ways and

make informed choices.

For CWA, this is the first workshop to be organised in India. Earlier it has organised a series of

workshops, seminars and training sessions in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Laos, Hong Kong,

some parts of mainland China, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Thailand. Over the years, CWA has developed a

training module on advocacy and social mobilisation, and has consistently stressed on advocacy at the household

levels as equal to government or policy makers.

At the Madurai Workshop, the first of its kind for those non-governmental organisations involved in

challenging child labour practices in south India, about eighty participants from all states are expected to take

part. This five day workshop is expected to provide a forum for exchange of information, experiences, skills in

advocacy and social mobilisation, and act together on specific issues of common concern. This will be facilitated

through an on-going process.

This workshop will focus on the tools, instruments and space that is available to bring about changes

which will facilitate progress and access to information, management and power for the most disadvantaged,

here grouped together as working children. These are working and action tools for all those who are required to

use strategies, persuasion and "aggressive" tactics in order to obtain the desired objective. Each participant will

be able to adapt them to the particular context and environment of his/her own activity - not only in the case of

politicians but also in the case of public service sectors, enterprises or any other decision-making group.

CH ?■<+

6-ft 7 3

M&pcU___

•

(>)

J/b” fy

&Of^mfMir'

__ 3>---- ■■>

,44-ax^-

/kf-

fo

/j^to^^C/pc zk>/fr/? ■___________ _________

7

/..........

.... . ..... .

— ■-■ . ........... ........

^0^7(x 0i~><A> Ja CCoL.

/ y

■

_____________________________________ ^i.^L-

—

........... v~................

/&L^ 2

A • oXa^

fa—. />*X>«- ■ #r—J/Co^-'

J* "

(T'/)J>Cj7<^'

__ _________

~~s>

/tZw/'y*?____ -

_______

_________ .___________ /Zcfr C/vr?^!____ & °- °j_________ ____________ ________________________________

*

______ _______

________ ,jp

^OzvCeoA,

&ZE&7

’

i^r

/■/eX’ffAd

C&<■?'?W J

X® c /g-r^

•

('hrvA^J

yg ^<- l/

V/

&WL. £?■___________

_s^LAg^.__ /ftJpg^L/______ a-

A^Axz^

TZTVTTTTTl

__ b CnraS-i.

~~l

''/[//v fitljM-e] &

• s>

__________

ftJtZkZv^ ■ —

ftf< (P^ &■ ft_______

'ft; y ? 11

^Jffi if O'** .

HA<-- S? <fl-^t^’_____ 6./-f

‘b-^/‘ '

__ ft, / trA-_______

__L.JI kc^ ft'J-’ft &>!'

/V» : /■

-ft

-

2&/1

jyvetfKe;-

<q

^ZdyA^c;

^/ t .'•-/

w

yrvie./^'

// "^ <

-

O-

/

'

f

//>-,

A? Ay zb

cg

Ce^w^-C^-

^MM--

kb lo^OVA

. 1

__________ '.____ _______________

r

■ ■■ --

'

-

bu ? '.--■

kksAA/^

2.

4

-

/mw/i

223

6

_________________________________________

ch-^V^Lh-e^.0^ '

f

- ■ L

J

R ClAj^eiL^'___________________

(wy

.

^z

’

■ gr

1 CH-b-

/■?</

^c/

__ . , /z^A

/

(?)

~2'r'S

0^3

[k2>(2 i

/U^ACt’

»

?3o

2>, f~-r-Q

Zv<

fyz'\< j-3/^c^y^—•

'vy

^L,

22.^

o2>fii^n bs'S

/^ /rf' '

.

‘5^7 /2) a>

<^V

£■ 6/ '6^2

CH S-S"

CITY

•THE TIMES OF INDIA, BANGALORE______________ 6p

'__________________

Street children expose lacunae in Juvenile Justice Act

Bv ALLADIJAYASRI

BANGALORE, April 1:

A little boy who was unhappy

J at home ran away to the city to

-seek his fortune. Bowled over

” by the magnificence of the great

buildings and fine people, opti

mism swelled his little heart, and

he thought, soon he too would

be as fine as they. Night fell, and

meeting a small group of street

children who were retiring for

the night on the footpath, the lit

tle boy settled down with them.

Along came the two police

constables, who rounded up the

sleeping children, marched

them off to the police station.

where they were beaten soundly

and locked up for the night.

The little boy was initiated

into the lifestyle of the street

child —illiterate, scrounging in

.the garbagefor ameal. theliving

symbol of society's rejects, and

worse still, a sitting target for

“the action arm of the law" -the

police. It would only be a matter

of time before his dreams are

buried under the mounds of gar

bage that would dominate the

next few years of his life, as he

runs for cover whenever a po

liceman is sighted.

This was a play staged by

street children at a workshop to

discuss the lacunae in the Juve

nile Justice Act. 1986 (JJA). or

ganised by the city forum of the

»

seven NGOs working for street

children last week.

The theme of the workshop

was to critically review the pro

visions of the Act, and to suggest

changes to convert it from a wel

fare legislation into an instru

ment of empowerment of chil

dren. for the protection of their

rights, since India has acceded

tp the UN convention on the

rights of the child in December

1992.

It is estimated that about 4.2

lakh children live on the streets

of Bombay. Madras, Calcutta,

Hyderabad. Bangalore and

Kanpur, and contrary to com

mon belief, most of them are

neither rootless nor unattached.

Nearly 89 per cent of them live

with parents or family. While

about 58 per cent of the street

children work for a living, 47 per

cent of these are self-employed.

as vendors, shoe-shines, news

paper hawkers, parking lot at

tendants and so on.

Nearly 90 per cent of the

street children are exposed to

dirt, smoke and other pollutants

and health hazards. Those who

are not exploited by parents and

employers are. as demonstrated

by the play, vulnerable to har

assment by the police and occa

sionally. the municipal authori

ties. If the former round them

up for crimes not committed by

them, on charges of vagrancy,

gambling and street brawls, and

pack them off to remand homes,

the latter harass them by confis

cating their shoe shine kits, or

shooing them away from the

streets.

At the workshop delegates,

representatives of NGOs from

Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Pune,

Madras. Madurai and the city.

besides lawyers and experts.

were of unanimous in the view

that the Act should make a clear

distinction between a juvenile

delinquent and a neglected child

to bring about the changes in the

Act.

Seeing a bigger role for NGOs

in handling delinquents and buf

feting them from the brutal as

pects of contact with the police,

the participants recommended

sensitisation of the police, parti

cularly in the middle and lower

ranks, since they deal directly

with street children and crime.

While most street children who

commit crimes are not afraid of

punishment, they dread being

sent to remand homes without

exception, they pointed out.

Ms Rita Panicker. of Butter

flies. Delhi, who conceded that

in recent years seniorpolice offi

cers were increasingly identify

ing themselves with the cause of

street children in major cities

where their numbers was grow

ing, however, felt that the com

pulsion to sensitise themselves

to the circumstances of the

street child was not evident

down the line.

There has been an occasion

when the street children in the

jurisdiction of a particular police

station were taken in on the pre

text of giving them identity

cards, and kept locked up all day

without food or water, and then

whisked away at night to be re

leased about 25 km away from

their "home" on the streets. Ms

Panicker said.

The principle causes of child

abandonment, neglect, abuse

and exploitation, which are the

main reasons for a child to turn

to the streets, could be directly

linked to the persistence of rural

and urban poverty. Said UNI

CEF programme officer Mr

Gerry Pinto: "A child left on the

streets to fend for himself or

herself may resort to thefts,

other criminal acts and prostitu

tion for subsistence. The child,

thus, becomes an expert in the

art of survival, and a growing

anti-social stance is fostered in

him or her. by resentment and

distrust of the society, which has

rejected it in the first place”.

This is where, delegates said,

the chasm between the legisla

tion of the JJA and its imple

mentation became obvious. Ms

Ved Kumari, faculty of law.

University of Delhi, who poin

ted out that since the delinquent

actions of children were forced

by circumstance rather than the

result of a hardened deviant

strain in their'Character, it was

necessary to make the distinc

tion between tuielinquent child

and a neglected child, regardless

of whether a crime had been

committed or not.

The Act covered the majority

of poor children, but left the im

plementation of infrastructural

obligations Jo the discretion of

the state governments. Under

the Act it was left to the state

governments to establish the

various agencies for implement

ing these obligations, and thus

non-implementation was more

the rule than the exception, she

argued. v

Most of the provisions focus

on institutionalisation, project

ing it as the prime measure for

dealing with children. This is

?ga>nst the principles laid down

m the UN standards minimum

rules for administration of juve

nile justice (also known as the

Beijing rules), which gives this

option as a last resort Ms Ved

Kumari said.

Another alarming fact is that

a special chapter on treatment of

special offences against chil

dren, although included in the

Act, remains unimplemented in

the absence of an enforcement

mechanism, she said.

According to Ms Indumathi

Chiplunkar, member, juvenile

welfare board, Pune, and repre

senting Action for the Rights of

the Child, the interface between

the police and the NGOs. is la

ced with antagonism and con

flict of interests, particularly

since the police regard street

child as illegal, requiring institu

tionalisation.

The JJA, on the other hand,

operates o ■ the premise that in

stitutionalisation is the last re

sort, particularly in the case of a

delinquent child, who might be

guilty ofcrime. To sensitise the

police to the needs and compul

sions of street children, she sug

gested the involvement of

NGOs as agencies creating the

social and intellectual bridge,

where the various facets of gov

ernment policy and functioning

could be examined to apply to

the actual and assumed needs of

the children.

Until the political process

evolves a mechanism that direct

ly relates to the marginalised

groups, and responds directly.

the NGO would remain a neccessary intermediary presence,

she pointed out.

• GH %-G

REPORT OF THE TWO DAY WORKSHOP ON STREET CHILDREN

Dates

6th and 7th July

Venue

Community

Health

Cell,

367,

Nilaya

I

Main,

Jakkasandra,

Koramangala, Bangalore 560 034.

1993

I

Srinivasa

Block,

Subjects dealt

with

Psychosocial and health problems

Communication technics and approach

methodology

Resource persons

Dr. Shekar Sheshadri

Child Psychiatrist.

(NIMHANS),

Dr. Shirdi Prasad Tekur,

Coordinator,

Community Health Cell.

Mrs. Indira Swaminathan

Psychologist) .

Organisations

presents

No.

of

participants

(Educational

REDS

l.

(Ragpickers Education &

Development Society).

2.Bosco Yuvadaya.

3.MAYA,

(Movement

-for

Alternative

and

Youth Awareness).

4.Montford Sisters (Asha Deep) Street

Children Programme.

S.Carmalite Sisters.

16

(list enclosed with addresses).

Mr.

Chander, CHC team member welcomed the participants

and

the

resource persons to the workshop.

The introductory session

was

started with an affirmation game.

Each participant should add an

adjective to his or her name while introducing oneself.

(example

active

Anthony).

The next person should repeat the

names

with

the

adjective

of

as

many people

who

have

already

finished

introducing

themselves.

This is what all about the

affirmation

game.

This

helps

injA recollecting

the

names

of

the

other

participants as well as gives a positive image to oneself.

The

first

session of the workshop was handled by

Dr.Shekar

on

psycho-social problems and the factors that influence during

the

developmental

period

of a kid from birth to the stage

where

a

child

actually

becomes homeless or street

child.

The

social

role

models in the families, social pathology of

the

families,

social environment and the role of media were some of the

factor

discussed

that

influence during the developmental period

of

a

child.

Anxiety, weeping and sadness were some of

the

internal

behavioural pattern that leads to aggression was described as

an

example of the psycho-social condition of these children.

Approach

in handling these children and methods of studying

the

case

history

of

these children were some

more

of

the

areas

discussed.

Giving

an

unconditional

positive

regard

to

the

children

was

discussed as an approach and

problem

focused

or

narrative

with

minimal

questions as a method

of

inquiry

was

suggested.

Dr.Shirdi

Prasad Tekur had a discussion on health

problems

and

its

causes

during

the

afternoon

session.

Discussion

on

prevention of some of the health problems caused by poor personal

hygiene and poor nutrition created an awareness in educating

the

children.

Diarrhoea, scabies, intestinal

worms,

tuberculosis,

leprosy, STD and cuts and wounds are some of the health

problems

which were dealt in specific.

The

second day's programme focused on

communication

techniques

and

approach

methodology

by

Mrs.

Indira

Swaminathan.

She

emphasised

the

need to move away from

the

usual

predominance

given

to dialogue and

conversation as a means of

communication

to

one

where there is more emphasis on

rhythmic

conversation,

songs,dance

and

games were some of

the

communication

methods

applied

and

tested.

Puppetry was introduced

as

a

means

of

understanding, different role models in the community and to give

them skills in the use of puppets.

The

participants

were

asked

to

observe

the

application

of

communication techniques and approach methodology with the street

children at REDS programme

by Mrs. Indira Swaminathan during the

afternoon

session.

There was a discussion about

the

practical

session

in order to identify the advantages of

non-conventional

methods in effective interaction with the children.

The

following

are

some of the

advantages

participants on the non-conventional methods.

method eliminates the

1.

Learning

non-conventional

with the facilitator.

2.

It attracts the children very easily.

3.

It helps

team building

identified

shy

by

the

feeling

in no time.

The following are some of the expectations by the participants to

be

met through the further follow up programmes.

Communication

skills,

hygiene, introducing chiId-to-chiId programme,

managing

conflict,

psycho-social

problems,

teaching

methodology

and

importance

of skill training.

-2-

The

participants were asked to answer

workshop

and

the

answers

are

as

a)

Regarding the definition of

are working with.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

b)

c)

before

the chiIdren/people with whom they

the reasons

that force a child

to become

homeless.

No family love

Irresponsible parents

More than one parent

Death of parents

Alcoholic parents

Quarrelsome family atmosphere

Forced to go to school

Want of freedom what the child wants to do

Unnecessary harassment

Regarding

the

methods

which were

already

adopted

organisations in handling the street children.

1 .

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

the

Street Children

Unauthorised slum dwellers

Asteriks

Unshaped Diamonds

Thrown out of the society

Ragpickers

Unloved or uncared street children

Regarding

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

-few questions

follows.

by

the

Counsel 1ing

Psychotherapy

Physical fitness training

Providing shelter

Fellowship gathering

Saving scheme

Education

Medical aid, and

Skill training.

The

workshop

concluded

with

the

further action to be taken regarding

participants'

feedback

and

the follow up programmes.

gh

g-9-

Cl (

The goal;.of-post-independence elementary educational policy

was to universalise elementary education on the basic pattern

by the-Constitution.8 In quantitative" terms, it meant radically

increasing the.number of schools and student enrolment to ensure.

that all children in the age-group 6-14 years were in school by

1960.

In part, to meet some of'the staggering costs involved

in creating and maintaining the required facilities, and.in order

to provide a liberal, vocational, citizenship training, the goal.

was to transform the entire elementary school system to the Basic

pattern as far as the qualitative side was concerned.

The hereculean task that- confronted those responsible for

implementation was to ensure, within a decade, extraordinary

quantitative and qualitative- reforms. All of this was to be

achieved within the limited resources that the nation could

provide which was always far less than even the minimum educational

requirements. The problem lay not merely in ensuring universal

provision of schools, universal enrolment.and retention of children

in the age-group .6-14 years.. What wqs especially unrealistic

about this policy was that universal elementary education was

expected to be achieved-as early as 1960, and that too of the

utopian qualitative order explicit in Basic education.

Such a

perspective on educational change ignored what was then widely

known about the Economic, social and political constraints on the

educational system.

These factors, limited the capacity of the

educational system to make a quantum leap on both quantitative

and qualitative fronts simultaneously.

The realities, however,, could not be avoided.

By 1959, a year

short of the Constitution's target date, the results of the First

All India Educational Survey were available.

It indicated that

only 83.1 per cent had access to - primary school facilities and

50.3 per cent of the' rural habitations were served by a'middle

school or section.

As in colonial India, the major problem was'

retention of children enrolled in Standard I. In 1950-51 for every 1,00 children enrolled.’in Standard I, there were 38 in

’

Standard TV and 12 in Standard VII; in 1961, the situation .had

deteriorated in that the proportion in Class IV was down to 33.

And consequently, only 42.2 per cent, of all the children, in the

age-group 6-14 years were enrolled at the time when it was ex

pected that all of them would be in elementary school*

.

’

..2

COMMUNITY health cell

47/1. (First Floorj St. Marks Road,

Bangalore - 560 001,

" •-“'Tito—crospect-s- ’of" Basic education becoming the new elementary

education pattern looked even bleaker (Table 3.1)•

TABLE 3.1

PROGRESS IN BASIC SCHOOLS BETWEEN 1950-1960- .

BASIC SCHOOLS/ENROLMENT

’ 1950-51

1960-61

Junior Basic Schools- (approx.

I-V)

1,400

25,866

Proportion of Junior Basic

Schools to the total number

of primary schools-percentage

.7

7.8

Senior Basic schools (standard

VI-VIII)

351

14,269

Proportion of senior basic

schools to the total number

of middle schools-percentage

2.6

28.7

.9

15.5

Students in junigr and senior ..

Basic schools as percentage of

.all students in primary and

middle schools ■

SOURCES: India, Ministry of Education, Education in India

1950-51, India, Ministry of Education, Education in India, 1960

61, Primary schools in U.P. have not been included as Basic

schools though they have been classified officially as Basic.'

At about the time of independence’,■ the U1P. State Government

overnight declared their primary schools to be Basic Schools

a change of nomenclature was the only result.

Despite liberal financial grants from the Central

government which took a keen interest in promoting Basic

education, the results were not promising. Even by 1960, the

majority of. elementary students were being educated in traditional

institutions. It was abovious that it would take many decades

for .Basic education, to .become the national pattern.

As far as the qualitative aspects were concerned, the results

were more disappointing. The majority of new .Basic schools or

elementary institutions converted .to the Basic patterns showed

little qualitative difference from the numerically large but

equally dismal traditional counterparts. The only striking dif

ference was that the * former spent one-third to one-rhalf of'the

school,day on craftwork, which was mostly limited to spinning';

The disenchantment was complete when it was discovered soon

after independence' that in practice. Basic schools were not only

nowhere near the goal of self-sufficiency, but ironically were

more expensive to set up and maintain than their literary

counterparts.

J. "C

CxS

O±? CI1CX*U

U-AiJ-.-J

Cl L, ,-. V > *1

1X

—.... .........

.-—••■

•* •

-- -■

■expectations on both the quantitative and qualitative fronts..

The problem that could no longer be avoided was whether the

country could afford an education which was expected to be

qualitatively superior and cheaper, but in practice turned out to

be neither. And this too when the universal complaint of Union

and State ministers of education was that elementary education

was being starved of funds, and that even the bare minimum as

far as bulding; equipment and teachers’ salaries could not be

provided.

Long before the 1964-66 Education Commission pronounced

its terse epitaph on Basic education-11 No single stage of education

need be. designated as Basic education"-it had been an open secret

that it had been moribund for a long time.^ In 1965, the Union

Minister of Education, M.C. Chagla, stated in parliament that he

agreed "as Dr. Zakir Husain said the other day, it has become

a vast mockery."10 This merely reflected what had long been the

prevailing view but had hitherto been rarely acknowledged

Officially.

Why did Basic education fail to develop as the new system of

mass elementary education? The overwhelming consensus of offical

and non-official opinion, then, as even now, was that this great

experiment failed due to inadequate implementation.

The reasons

forwarded include apathetic and agnorant administrators, poor

quality of teachers and teacher training resulting in lifeless

traditional classroom teaching, inefficient craft teaching in

Basic training caliches and scheels, inadequate resources for land,

buildings, craft equipment and materials, truncation of the

Basic course into

*A major problem, and one which is even more serious today,

was that government officials were constrained to discuss their

views freely since it was considered heretical on their part to c

criticise government policy. A dim view was taken of the tren

chant comments, submitted by R.r, Singh, who was the Education

Advisor to the Ministry of Community Development in the mid

fifties, on Basis education policy end its implementation.

junior (primary}and senior (minddie) stages, the absence of sen

ior basic schools, and the lack of articulation with higher levels

of education. ~ The more populist strain of critcism also

perceived in its failure the. successful machinations of the

powerful elites of Indian society.

In some cases they were

also held .partly responsible' for the rural masses' apathy and some

times hostility towards Basic education.

...

—3

Explicit or implicit in all these accounts with very few

exception was that Basic education

no$ "th$ p©aX point in .

tha development of world educational thought." as one of its more

-•repEMch.^3

’That: was rarely questioned-and when questioned not

developed into a comprehensive radical critique-was whether

the record of poor implementation resulted from attempting to

implement the unimplementable. Inadequate implementation was

merely the inevitable.consequence of a misguided effor to insti

tutionalise a conceptually unsound model of mass elementary

education.-

At no time in the past thirty years or in the foreseeable

future could the fundamental principles of Basic education be

impletmented an a mass scale.*

It was theoretically deficient as

a model of mass element'ary education in that it set out utopian

objectives which were impossible to meet. Moreover, it could

not respond to the national and.constitutional imperatives to

expand elementary education rapidly.

Its structure precluded it

from tackling creatively the problems confronting the traditional

educational system, and in fact exacerbated the fight against

illiteracy.

BASIC EDUCATION-THE INEVITABLE FAILURE OF A CONCEPTUALLY

INAPPROPRIATE MODEL OF MASS ELEMENTARY EDUCATION

The following discussion delineates various aspects of this

case. Each aspect begins with a frief statement, and the argu

ment is then devloped arid explained in detail.

i.

The objectives and content of Basic Education could not

be

*It should be noted tha^^prior to independence, thre is

documentary evidence to prove that at least in the state of Bom

bay, the educational establishment and those in charge of imple

menting Basic education knew that it was not possible,, despite

concertand conscientious attempts, to implement it on a mass A

level.

This realisation was based on the poor record of the

experimental Basic schools begun in the state.

reconciled with a high pupil-teacher ratio and a system of shift

• or part-time instruction, but was designed and could only be imple

mented with a low pupil-teacher ratio and full-time schooling

This not only precluded lowering the costs of schooling when it

was implemented, but effectively undercut the ability- of the new

model to tackie enrolment and dropout problems which were the

major deficiencies of the existing traditional system.

Basic education was to provide the all-round training required

for the new citizen o£ India. It was to inculcate a level of

skill in the central handicraft chosen which would enable a pupil

at the completion, of the eight year course to pursue it as an

occupation. The curriculum suggested by the Zakir Husain

Committee Report for the seven- years that it envisaged as neces

sary for meeting the objectives of Basic education, included

among other subjects, mother-tongue, mathematics, social studies

. .5.

■-arrci~<K— science.- These were to be correlated as much as,

possible to the central handicraft, and the physical and social

environment, in order to establish the foundations in the nations'

youth for the evolution of a new type of man-one who was non-violent,

upheld the dignity of manual labour, had occupational skills in

the craft, and was an aware and active citizen who would help

in the •.reaonstru.Qtipn. of ..the- nation. ■

■

.....

‘-.iy

- ■.

-

- b.

t

■

.

En.-short, the Basic curriculum a was conceived., to be a far

.richer curriculum than the traditional curriculcun-and one which

was not.and could not.be modifed substantially by later reports

on Basic education.

This was not surprising given that its

objectives were more. ambitious-"the' creation of a new type of mans

While in its implementation, practice varied from schools to school, ■

the curriculum was richer if -in. notihing .else in that the Basic

s.chool.gaye a^eentr'al position, to .the teaching .of craft-,, and

emphasised cpummunity-and •-other, practical: .activities.

The implications of such a curriculum, as far as .the number.

of students a teacher could possiblv handle, were clear, The.

Zakir Husain Report, suggested that the teacher-pupil ratio should

not exceed is30 since a...larger number of students would not make

it possible for the "teacher to discharge his heavy and responsible

duties efficiently.",15. Weighed by similar and.other, considerations

■pSr fPX" example - the, necessity, of specialist; t&achcrs. at ..the. middle

schools stage, the; 1-944 S.grgent Report. suggested/a-is 30 ratio.in

punier- .Basic, (.primary) schools and.. 1:25'..inSenior-. Basic (middle)

schools,

The. 1950 ■ Kher Committee, on the ways and Means of. Finan-

P-PSk EducatiSnal- Deyglopipent in-.I^dia while strongly advocating

the. guick change-over,--of - the nation's?academic.schools to thel .■

•Basic - pattern,., with " great;.reluctance ". aggeed that financial

■popsi.a®rations .necessitated-.that the-teachertpupil ratio should

be 1:40 instead of 1:30 "though from, the educational point of

view the change'would be most undetrable.'-" •'16 However, it recom

mended-that this was 'to' be reviewed at’the - end of five 'years, and

that the 1:30 ratio was to be restored earlier if possible.

The low pupil-teacher ratio that was advocated was not

merely a consequence of the enriched curriculum and craft which :

was. central to the concept of Basic education. ■ --.-.Such-an- uneconomic

rat io .was also the consequence. of a. superior. pedagogy-;which:was.;-

expected of -Basic teachers than.traditional.pedagogues.

For at-

the he art of Basic educ ation was thq. notion-th at the craft and the natural and social enylrpnrpeht ,.lwhich-. -f ormed.the-basis - of . the

curriculum,- werg. to be taught, in... an < integrated manner as far as

possible.

More^tyer,'--the'Concept of an enriched curriculum precluded

any notion of shrtening the school-day, having joart-time

■classes or using the shift system. This Could not be done

without affecting, adversely.-the: object iv-b's? of thsv R'asit'''prc.grsnne. .-r- £r.-d •

-.could:?;theg shne-'fcachebe "bs'e'd--to

1 tgaoh. fftwbe c.l.asses.;,;(-dbublethhi^‘'^d^m^t-*,!^,:^®At'-the ..-.working hours. .of elementary. sqhpp.l--> t^achers.-i.-XPo-hh^UU'^ibbptablo

. level, • The< implication^ -of /the -qoncppt.:.o± Sasic' edubati-on