NATIONAL PUBLIC HEARING ON RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE ORGANISED BY NHRC & JSA ON 16-17 DECEMBER 2004, NEW DELHI

Item

- Title

-

NATIONAL PUBLIC HEARING ON RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

ORGANISED BY NHRC & JSA ON 16-17 DECEMBER 2004, NEW DELHI

- extracted text

-

NATIONAL PUBLIC HEARING ON RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE

ORGANISED BY NHRC & JSA ON 16-17 DECEMBER 2004, NEW DELHI

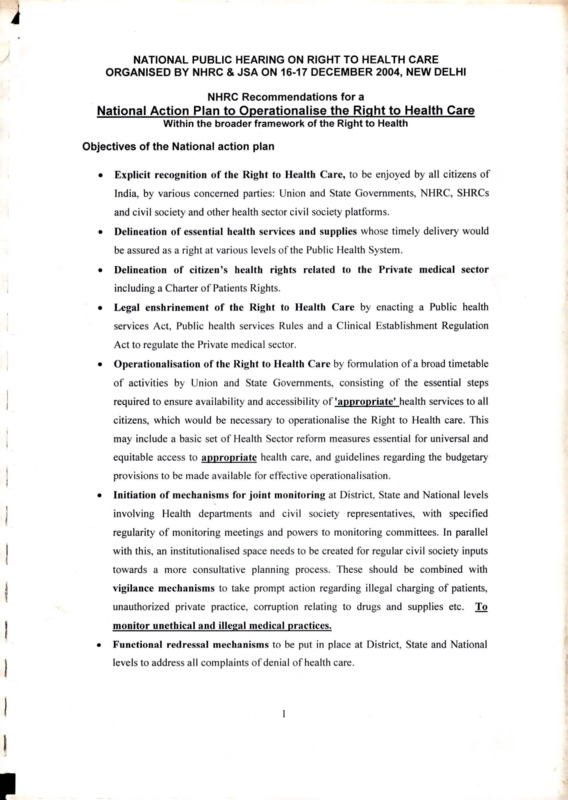

NHRC Recommendations for a

National Action Plan to Operationalise the Right to Health Care

Within the broader framework of the Right to Health

Objectives of the National action plan

•

Explicit recognition of the Right to Health Care, to be enjoyed by all citizens of

India, by various concerned parties: Union and State Governments, NHRC, SHRCs

and civil society and other health sector civil society platforms.

•

Delineation of essential health services and supplies whose timely delivery would

be assured as a right at various levels of the Public Health System.

•

Delineation of citizen’s health rights related to the Private medical sector

including a Charter of Patients Rights.

•

Legal enshrinement of the Right to Health Care by enacting a Public health

services Act, Public health services Rules and a Clinical Establishment Regulation

Act to regulate the Private medical sector.

•

Operationalisation of the Right to Health Care by formulation of a broad timetable

of activities by Union and State Governments, consisting of the essential steps

required to ensure availability and accessibility of’appropriate* health services to all

citizens, which would be necessary to operationalise the Right to Health care. This

may include a basic set of Health Sector reform measures essential for universal and

equitable access to appropriate health care, and guidelines regarding the budgetary

provisions to be made available for effective operationalisation.

I

•

Initiation of mechanisms for joint monitoring at District, State and National levels

involving Health departments and civil society representatives, with specified

regularity of monitoring meetings and powers to monitoring committees. In parallel

with this, an institutionalised space needs to be created for regular civil society inputs

towards a more consultative planning process. These should be combined with

vigilance mechanisms to take prompt action regarding illegal charging of patients,

unauthorized private practice, corruption relating to drugs and supplies etc.

To

monitor unethical and illegal medical practices.

•

Functional redressal mechanisms to be put in place at District, State and National

levels to address all complaints of denial of health care.

1

i

Recommendations under the action plan

Recommendations to Government of India / Union Health Ministry

•

Enactment of a National Public Health Services Act, recognizing and

delineating the Health rights of citizens, duties of the Public health system,

public health obligations of private health care providers and specifying broad

legal and organisational mechanisms to operationalise these rights. This act would

make mandatory many of the recommendations laid down, and would make more

justiciable the denial of health care arising from systemic failures, as have been

witnessed during the recent public hearings.

This act would also include special sections to recognise and legally protect the

health rights of various sections of the population, which have special health

needs: Women, children, persons affected by HIV-AIDS, persons with mental

health problems, persons with disability, persons in conflict situations, persons

facing displacement, workers in various hazardous occupations including

unorganised and migrant workers etc.

•

Delineation of model lists of essential health services at various levels: village /

community, sub-centre, PHC, CHC, Sub-divisional and District hospital to be

made available as a right to all citizens.

•

Substantial increase in Central Budgetary provisions for Public health, to be

increased to 2-3% of the GDP by 2009 as per the Common Minimum Programme.

•

Convening one or more meetings of the Central Council on Health to evolve a

consensus among various state governments towards operationalising the Right to

Health Care across the country.

•

Enacting a National Clinical Establishments Regulation Act to ensure citizen’s

health rights concerning the Private medical sector including right to

emergency services, ensuring minimum standards, adherence to Standard

treatment protocols and ceilings on prices of essential health services. Issuing a

Health Services Price Control Order parallel to the Drug Price Control Order.

Formulation of a Charter of Patients Rights.

•

Setting up a Health Services Regulatory Authority - analogous to the Telecom

regulatory authority- which broadly defines and sanctions what constitutes

rational and ethical practice, and sets and monitors quality standards and prices of

services. This is distinct and superior compared to the Indian Medical Council in

that it is not representative of professional doctors alone - but includes

2

Elements of Advocacy

e Public campaigns on right to healthcare

• Raising the budget / allocations

• Dialogue with parliamentarians

f Dialogue with civil society groups

e Public Hearings

/•Policy briefs and info packs

• Media use

• Legislative/ Constitutional changes

• Public interest litigation_______

Examples of monitoring

and advocacy from India

© Budget monitoring and advocacy (CEHAT)

e Right to healthcare campaign (JSA)

e Research support for right to healthcare

(CEHAT)

• Public hearings on denial of healthcare and

violation of health rights (NHRC, JSA)

Monitoring sex selection and advocating for

changes in and implementation of PNDT Act

(CEHAT, MASUM...)

• Regulation of the medical profession (CEHAT)

ai>

a^°r^t

2

representatives of legal health care providers, public health expertise, legal

expertise, representatives of consumer, health and human rights groups and

elected public representatives. Also this could independently monitor and

intervene in an effective manner.

•

Issuing National Operational Guidelines on Essential Drugs specifying the

right of all citizens to be able to access good quality essential drugs at all levels in

the public health system; promotion of generic drugs in preference to brand

names; inclusion of all essential drugs under Drug Price Control Order;

elimination of irrational formulations and combinations. Government of India

should take steps to publish a National Drug Formulary based on the morbidity

pattern of the Indian people and also on the essential drug list.

•

Measures to integrate National health programmes with the Primary Health

Care system with decentralized planning, decision-making and implementation.

Focus to be shifted from bio-medical and individual based measures to social,

ecological and community based measures. Such measures would include

compulsory health impact assessment for all development projects; decentralized

and effective surveillance and compulsory notification of prevalent diseases by all

health care providers, including private practitioners.

•

Reversal of all coercive population control measures, that are violative of basic

human rights, have been shown to be less effective in stabilising population, and

draw away significant resources and energies of the health system from public

health priorities. In keeping with the spirit of the NPP 2000, steps need to be taken

to eliminate and prevent all forms of coercive population control measures and the

two-child norm, which targets the most vulnerable sections of society.

•

Active participation by Union Health Ministry in a National mechanism for health

services monitoring, consisting of a Central Health Services Monitoring and

Consultative Committee to periodically review the implementation of health

rights related to actions by the Union Government. This would also include

deliberations on the underlying structural and policy issues, responsible for health

rights violations. Half of the members of this Committee would be drawn from

National level health sector civil society platforms. NHRC would facilitate this

committee. Similarly, operationalising Sectoral Health Services Monitoring

Committees dealing with specific health rights issues (Women’s health,

3

Children’s health, Mental health, Right to essential drugs, Health rights related to

HIV-AIDS etc.)

•

The structure and functioning of the Medical Council of India should be

immediately reviewed to make its functioning more democratic and transparent.

Members from Civil Society Organisations concerned with health issues should

also be included in the Medical Council to conform medical education to serve

the needs of all citizens, especially the poor and disadvantaged.

•

People’s access to emergency medical care is an important facet of right to health.

Based on the Report of the Expert Group constituted by NHRC (Dr. P.K.Dave

Committee), short-term and long-term recommendations were sent to the Centre

and to all States in May 2004. In particular, the Commission recommended:

(i)

Enunciation of a National Accident Policy;

(ii)

Establishment of a central coordinating, facilitating, monitoring and

controlling committee for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) under

the aegis of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare as advocated in the

National Accident Policy.

(iii)

Establishment of Centralized Accident and Trauma Services in all

districts of all States and various Union Territories along with

strengthening infrastructure, pre-hospital care at all government and

private hospitals.

•

Spurious drugs and sub-standard medical devices have grave implications for the

enjoyment of human rights by the people. Keeping this in view all authorities are

urged to take concrete steps to eliminate them.

•

Access to Mental health care has emerged as a serious concern. The NHRC

reiterates its earlier recommendations based on a Study “Quality Assurance in

Mental Health” which were sent to concerned authorities in the Centre and in

States and underlines the need to take further action in this regard.

Recommendations to State Governments / State Health Ministries

•

Enactment of State Public Health Services Acts/Rules, detailing and operationalising

the National Public Health Services Act, recognizing and delineating the Health rights

4

of citizens, duties of the Public health system and private health care providers and

specifying broad legal and organisational mechanisms to operationalise these rights.

This would include delineation of lists of essential health services at all levels:

village / community, sub-centre, PHC, CHC, Sub-divisional and District hospital to be

made available as a right to all citizens. This would take as a base minimum the

National Lists of essential services mentioned above, but would be modified in keeping

with the specific health situation in each state.

These rules would also include special sections to recognise and protect the health

rights of various sections of the population, which have special health needs:

Women, children, persons affected by HIV-AIDS, persons with mental health

problems, persons in conflict situations, persons facing displacement, workers in

various hazardous occupations including unorganised and migrant workers etc.

•

Enacting State Clinical Establishments Rules regarding health rights concerning the

Private medical sector, detailing the provisions made in the National Act.

•

Enactment of State Public Health Protection Acts that define the norms for

nutritional security, drinking water quality, sanitary facilities and other key

determinants of health. Such acts would complement the existing acts regarding

environmental protection, working conditions etc. to ensure that citizens enjoy the full

range of conditions necessary for health, along with the right to accessible, good quality

health services.

•

Substantial increase in State budgetary provisions for Public health to parallel the

budgetary increase at Central level, this would entail at least doubling of state health

budgets in real terms by 2009.

•

Operationalising a State level health services monitoring mechanism, consisting of

a State Health Services Monitoring and Consultative Committee to periodically

review the implementation of health rights, and underlying policy and structural issues

in the State. Half of the members of this Committee would be drawn from State level

health sector civil society platforms. Corresponding Monitoring and Consultative

Committees with civil society involvement would be formed in all districts, and to

monitor urban health services in all Class A and Class B cities.

•

Instituting a Health Rights Redressal Mechanism at State and District levels, to

enquire and take action relating to all cases of denial of health care in a time bound

manner.

5

•

A set of public health sector reform measures to ensure health rights through

strengthening public health systems, and by making private care more accountable and

equitable. The minimum aspects of a health sector reform framework that would

strengthen public health systems must be laid down as an essential precondition to

securing health rights. An illustrative list of such measures is as follows:

1. State Governments should take steps to decentralize the health services by giving

control to the respective Panchayati Raj Institutions(PRIs) from the Gram Sabha

up to the district level in accordance with the XI Schedule of the 73rd and 74th

Constitutional Amendment of 1993. Enough funds from the plan and non plan

allocation should be devolved to the PRIs at various levels. The local bodies should

be given the responsibility to formulate and implement health projects as per the

local requirements within the local overall framework of the health policy of the

state. The elected representatives of the PRIs and the officers should be given

adequate training in local level health planning. Integration between the health

department and local bodies should be ensured in formulating and implementing the

health projects at local levels.

2. The adoption of a State essential drug policy that ensures full availability of

essential drugs in the public health system. This would be through adoption of a

graded essential drug list, transparent drug procurement and efficient drug

distribution mechanisms and adequate budgetary outlay. The drug policy should

also promote rational drug use in the private sector.

3. The health department should prepare a State Drug Formulary based on the health

status of the people of the state. The drug formulary should be supplied at free of

cost to all government hospitals and at subsidized rate to the private hospitals.

Regular updating of the formulary should be ensured. Treatment protocols for

common disease states should be prepared and made available to the members of

the medical profession.

4. The adoption of an integrated community health worker programme with adequate

provisioning and support, so as to reach out to the weakest rural and urban sections,

providing basic primary care and strengthening community level mechanisms for

preventive, promotive and curative care.

5. The adoption of a detailed plan with milestones, demonstrating how essential

secondary care services, including emergency care services, which constitute a basic

right but are not available today, would be made universally available.

6

6. The public notification of medically underserved areas combined with special

packages administered by the local elected bodies of PRI to close these gaps in a

time bound manner.

7. The adoption of an integrated human resource development plan to ensure adequate

availability of appropriate health humanpower at all levels.

8. The adoption of transparent non-discriminatory workforce management policies,

especially on transfers and postings, so that medical personnel are available for

working in rural areas and so that specialists are prioritised for serving in secondary

care facilities according to public interest.

9. The adoption of improved vigilance mechanisms to respond to and limit corruption,

negligence and different forms of harassment within both the public and private

health system.

10. All health personnel upto the district PRI level must be administratively and

financially accountable to the PRI at each level from the Gram Panchayat to the

District level. Adequate financial resources must be made available at each level to

ensure all basic requirements of health and medical care for all citizens.

•

Ensuring the implementation of the Supreme court order regarding food security,

universalising ICDS programmes and mid day school meal programmes, to address

food insecurity and malnutrition, which are a major cause of ill-health.

•

People’s access to emergency medical care is an important facet of right to health. Based

on the Report of the Expert Group constituted by NHRC (Dr. P.K.Dave Committee),

short-term and long-term recommendations were sent to the Centre and to all States in

May 2004. In particular, the Commission recommended:

(i)

(ii)

Enunciation of a National Accident Policy;

Establishment of a central coordinating, facilitating, monitoring and controlling

committee for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) under the aegis of Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare as advocated in the National Accident Policy.

(iii) Establishment of Centralized Accident and Trauma Services in all districts of all

States and various Union Territories along with strengthening infrastructure, pre

hospital care at all government and private hospitals.

7

Spurious drugs and sub-standard medical devices have grave implications for the

enjoyment of human rights by the people. Keeping this in view all authorities are urged

to take concrete steps to monitor and eliminate them.

Access to Mental health care has emerged as a serious concern. The NHRC

reiterates its earlier recommendations based on a Study “Quality Assurance in Mental

Health” which were sent to concerned authorities in the Centre and in States and

underlines the need to take further action in this regard.

Recommendations to NHRC

NHRC would oversee the monitoring of health rights at the National level by

initiating and facilitating the Central Health Services Monitoring Committee, and at

regional level by appointing Special Rapporteurs on Health Rights for all regions of

the country.

Review of all laws/statutes relating to public health from a human rights perspective

and to make appropriate recommendations to the Government for bringing out

suitable amendments.

Recommendations to SHRCs

SHRCs in each state would facilitate the State Health Rights Monitoring Committees

and oversee the functioning of the State level health rights redressal mechanisms.

Recommendations to Jan Swasthya Abhivan and civil society organisations

JSA and various other civil society organisations would work for the widest possible

raising of awareness on health rights - ‘Health Rights Literacy’ among all sections of

citizens of the country.

8

LAW AND ETHICS

THE LAW

• a set of rules which governs the way people

behave

• the law creates corresponding rights and

obligations

ETHICS

• moral principles which guide behaviour

(e.g.: ethical guidelines for professionals Hippocratic Oath)

SOURCES OF LA W

Constitutional Law

SOURCES OF LAW

Constitutional Law

Statutory Law

Common Law

Customary Law

Personal Law

SOURCES OF LAW

Common Law

^fundamental rights ofcitizens

‘arose from Englishjudge-made law

^imported into India by the British under the

doctrine ofequity, justice & good conscience

★supreme law

Customary Law

Statutory Law

^developedfrom the customs ofa community

*in existence from time immemorial

(> 30 years)

*how State is organised

★laws made by Parliament/Legislatures

SOURCES OF LAW

Personal Law

^applicable to a person on the basis oftheir

religion

★originally applicable in all spheres, contract,

criminal andfamily and succession

★now primarily family and succession law

SEPARA TAION OF POWERS

Judicial Review

Organs ofState:

• Legislature (Parliament)=makes law

• Executive (Government Police,

Bureaucracy)^ implements law

• Judiciary= Reviews what laws are

passed and actions of the executive

1

JUDICIAL REVIEW

• India has a Written Constitution

TYPES OF LAW

• Constitution is Supreme Law

Criminal Law

• All laws have to be within it and

subordinate to it (intra vires)

*how State expects you to behave in

society

• High Courts and Supreme Court

decide whether law is constitutional

Civil Law

• Even a constitutional amendment has

to be intra vires (doctrine of basic

features/structure)

THE LEGAL RESPONSE...

• the evolving pandemic of HIV/AIDS has

given rise to legal responses

• more developed in USA, Australia - where

the pandemic hitfirst

• in these countries a wide variety of legal

responses arose

• in most developing countries the legal

responses are notfully developed and are

very much in the early stages

THE LEGAL RESPONSE...

• prescriptive (prescribes behaviour)

• proscriptive (punishes behaviour)

• human rights (protective of individual

rights)

• instrumentalist (promote behaviour

change)

• pedagogic (educative)

*how one must behave in private

relationships

THE LEGAL RESPONSE

The law has various roles

★deterrent

★normative/pedagogic

The law is *premised on various doctrines

★natural law

★human rights

Today we live in an era of the positivist state

- a body ofpersons authorised to make

enforceable laws

THE LEGAL RESPONSE

• Generally there have been two types

of legal responses

• These responses are diametrically

opposed

• They can be termed as the isolationist

response and the integrationist

response

2

ISOLA TIONIST v. INTEGRA TIONIST

isolationist

• mandatory testing

• confidentiality

breached

• discrimination if

HIV-positive

• ...leading to

isolation of HIV

positive person...

integratioinst

•voluntary testing

•confidentiality

maintained

*no discrimination if

HIV-positive

•...leading to

integration of HIV

positive

person...

ISOLATIONIST RESPONSE.

IN PRA CTICE, THE ISOLA TIONIST

STRATEGY

• further targets already marginalised

populations like sex workers, drug

users and men who have sex with men

• is violative of fundamental rights

• results in driving the HIV epidemic

underground

THE ROLE OF THE LAW...

• Right to health is recognised as a

fundamental right under Article 21 of the

read with Article 47 of the Constitution

• State is required to reimburse expenses for

open heart surgery as per rules

• However budgetary constraints have to be

considered while framing rules

(Vincent Panikurlangara; Surjit Singh; Ram

Lubhaya; cases)

ISOLATIONIST RESPONSE

PROBLEMS...

1. REQUIRES COMPULSOR Y REPEA T

TESTING OF HIV-NEGA TIVE

PERSONS (every six months)

2. ECONOMICALLY NOT FEASIBLE

3. IMPOSSIBLE TO IMPLEMENT FOR

THE WHOLE OF THE POPULA TION

IN A COUNTR Y LIKE INDIA

THE ROLE OF THE LAW...

• it is clearly necessary to opt

for either the isolationist

response or the integrationist

response

THE ROLE OF THE LAW...

• The law, especially in the

social sphere, must base itself

on a rational and scientific

understanding of the issue at

hand and not on prejudice,

myth or political opinion

3

THE LEGAL RESPONSE...

• 1986: Goa Public Health (Amendment) Act

-- espouses isolation

• 1989: Lucy D 'Souza's case challenges the

Act -- rejected by Bombay High Court.

However, the Act is no longer implemented

• 1989: AIDS Prevention Bill, 1989 - not

passed by Parliament

• 1997: Draft National AIDS Prevention &

Control Policy — espouses a rights-based

approach (approved by Cabinet in 2002)

THE LEGAL RESPONSE

• 2001: India signatory to UN Declaration of

Commitment on HIV/AIDS

• 2001/2: NGOs intervening with MSM and

CSW are harassed, raided - workers jailed

• 2002: Calcutta HC awards damages of Rs.

22 lakhs -- negligence ion blood transfusion

2002: Andhra Pradesh & Goa governments

consider mandatory pre-marital testing

• 2002: MCI Regulations fail to reevaluate

medical practice

• 2005: TRIPS -- impact on drug prices?

THE LEGAL RESPONSE

• 1997: MX v ZY — Bombay HC upholds right

of PWA to employment

• 1998: Mr. X v Hospital Z — Supreme Court

suspends the right of PWA to marry

(reversed in December 2002)

• 1999: Maharashtra & Karnataka legislators

table isolationist HIV Bills

• 2000: NHRC recommends rights-based

legal measures

• 2000/1: Bombay & Kerala HC injunct false

advertising of ‘cures’

PUBLIC HEALTH

CLASSIC DEBATE

Rights of the individual v. Rights of the Community

Individuals Rights

v. Public Health Interest

• Also raised in the HIV/AIDS Pandemic

• False Debate (No dispute that Public Health,

that is .Stopping further Spread of HIV is key)

• Paradox in the HIV/AIDS scenario is that

public health can only be enhanced by

protecting the rights of individuals infected and

affected

PUBLIC HEALTH

There exists a dramatic gap

between the identification and

existence of human rights and

the respect and enforcement of

human rights...

Domestic law seeks to bridge

this gap and empowers the

individual to assert and

vindicate his/her rights.

4

THE ROLE OF THE LAW IN

HIV/AIDS

Domestic law should promote

effective policies that impede

HIV transmission while

assuring the dignity of each

individual living with

HIV/AIDS

5

SOURCES OF

INTERNATIONAL LAW (IL)

• Article 38, Statute of 1CJ

• Customary Law

• Treaties (interpretation by Vienna Convention)

• General principles of law

• Equity

• Judicial decisions

• The writings of publicists

• Ethical principles and considerations of humanity

• Soft law

Right to health under IL

• World Health Organization

• United Nations Charter

- Articles 55 and 56

• Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

(General Assembly Resolution)

- Right to standard of living adequate for the health of

himself and his family, including . healthcare (Article

25(1))

- Right to share in scientific advancements and its benefits

(Article 27(1))

• International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

1966

- Right to life (Article 6)

Right to health under IL

• International Convention on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights

- Right to highest attainable standard of health (Art. 12)

- General Comment No. 14, 2001:

• The obligations to respect, promote and fulfil

• Obligation to respect States to refrain from interfering with

enjoyment of right to health

• Obligation to protect States to make measures that prevent

third parties from interfering with the right to health, includes

duties of States to adopt legislation or take measures to ensure

equal access to health-care services provided by third parties

• Obligation to fulfil State to adopt measures towards full

realization of the right to health

Right to health under IL

• Other international instruments such as

CEDAW, CRC, Charter of Economic

Rights and Duties of States

• Regional instruments

• Therefore, right to health is a part of

Customary IL

■ Core obligations

1

Application of IL in national courts

IL in India

• International Customary Law

- Does not require to be domesticated

- Applied by national courts unless domestic law to the

contrary

• International Treaties

- Monism IL and municipal law part of the same system,

no need of legislation

- Dualism: IL and municipal law are two distinct legal

systems. IL can be enforced only when incorporated or

transformed into municipal law

- Treaty is law under domestic jurisdiction unless

there is contrary domestic statute

- Treaty can be used to interpret rights and

fundamental rights

• Article 51 (c), Constitution of India: The

State shall endeavour to foster respect for

international law and treaty obligations in

the dealings of organised people with one

another.

• Article 253, Constitution of India:

Parliament has power to make any law for

implementing any treaty, agreement or

convention with any other country, or

countries or any decision made at an

international conference, association or

other body.

IL in India

IL in India

• M. V. Elisabeth Harwan Investment &

Trading Pvt Ltd., Goa, AIR 1993 SC 1014:

Conventions to which India is not a party are the result of

unification and development of maritime laws of the

world, and can, therefore, be regarded as international

common law or transnational law rooted in and evolved

out of the general principles of national laws, which in the

absence of specific statutory provisions, can be adopted

and adapted by courts to supplement and complement

national statutes on the subject"

• Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, (1997) 6

SCC 241:

The international conventions and nonns are to be

read into [the fundamental rights] in the absence of

enacted domestic law occupying the filed when

there is no inconsistency between them. It is now an

accepted rule of judicial construction that regard

must be had to international conventions and norms

for construing domestic law when there is no

inconsistency between them and there is a void in

the domestic law.

2

CONSENT

CONSENT

• Medical consent is part of common law

• Consent is free when it is not caused by

• Principles of consent in common law are

set out in detail in the law of contract and

are applicable to consent in the medical

field

• “Consent is taken when two or more

persons agree upon the same thing in the

same sense. ”

• Coercion

• Undue Influence

• Fraud

• Misrepresentation

• Mistake

• (Section 14 of the Indian Contract Act)

(Section 13 Indian Contract Act)

CONSENT

• EXCEPTIONS TO CONSENT

• unconscious patient brought to hospital

^doctrine of necessity will permit doctor to

interfere with bodily integrity

Necessity not convenience

• acting out of necessity legitimizes an

otherwise unlawful act

CONSENT

• DOCTOR - PA TIENT RELA TIONSHIP

• relationship between unequals :

Doctors have *better knowledge

★larger experience

• Therefore the duty of the physician :

★is to provide honest information

• BASIS OF THE DOCTRINE OF

INFROMED CONSENT

INFORMED CONSENT

INFORMED CONSENT

“patient must agree to the risk to which s/he

may be exposed"

VAR YING APPROACHES:

• Expert approach= Doctor's right= UK

What sort ofrisks are to be disclosed ?

• Patient approach^ Patient's right= USA

How much information does the patient

require to have?

• Middle approach= Mix of both= Canada

Who should decide ?

• India = No approach= Common law

Dependant on the predilection ofjudges

Varying approaches in the US, Canada and

England;

• Can we leave it judges or should we have

a statute?

1

INFORMED CONSENT

ENGLISH APPROACH: Current medical

Practice

The test of whether to inform of the risks

(part of the general duty of care) and what

to inform was to he determined by the

Bolam test= current medical practice

INFORMED CONSENT

US Approach=Prudent Patient test

• Doctor must disclose all material risks based

on the prudent patient

(A risk is material when a reasonable person

would attach significance to)

Current medical practice may he ignored if a

substantial risk was likely and the right to

information was so obvious

• A doctor however has the therapeutic

privilege to withhold information if the

disclosure would result in serious adverse

psychological consequences to the patient

(Sidaway v. Board of Governors, England)

(Canterbury v. Spence, US)

INFORMED CONSENT

CANADIAN Approach=lVIodified objective

test: Mixture of Objective and Subjective

• The patient has a right to know all material

risks inherent in the procedure or treatment.

• A risk is material if in the circumstances of a

case, a reasonable person would have

attached significance to it - objective factors

• Risks are also material which are particular

considerations affecting the particular

patient constitute the subjective factors

INFORMED CONSENT

INFORMED CONSENT

• Consent for Blood transfusion

• Patient has a right to control her own

body and reject specific treatment, even if

such a decision may entail a risk such as

death.

• Risks relating to transfusion should he

explained to the patient

• Possible consequences of refusal should be

brought out

• Specific Consent should he taken

INFORMED CONSENT

HIV SCENARIO:

Consent for an HIV is a diagnostic test

• HIV7infection is not curable

• other diagnostic tests do not have lifeth reaten ing implications

• HIV test has life threatening implications

• knowledge of HIV-positive status itself

may led a person to untold trauma like

taking one’s life

• HIV test cannot he treated as any other

diagnostic test

• consent to another diagnostic test cannot

he taken as implied consent to an HIV test

• Specific consent for an HIV test necessary

• An HIV test must be preceded by informed

consent

2

TESTING

TESTING

HIV SCENARIO

When to test for HIV?

• Indicative of treatment

• Preventive measures for Mother to Child

Transmission

• Significant risk ofexposure

What is Confidentiality ?

• Confidentiality arises when there is :

• a confidential relationship, the nature of

which may be dependent on factors of trust,

knowledge and skill

• confidential information

PRl VA CY-SECRECYCQNFIDENTIALITY

• confidentiality arises when information

which has the necessary quality of

confidence about it has been imparted in

circumstances importing an obligation of

confidence.

• the duty to maintain confidentiality

emerges from common law principles.

• informed consent in the context of

HIV/A1DS implies conducting pre and

post-test counselling

• failure to perforin pre and post-test

counselling implies no consent

PRI VA CY-SECRECYCONFIDENTIALITY

• Privacy

the right of a person vis-a-vis the world

at large

• Secrecy

the right of a person vis-a-vis the state

• Confidentiality

the right of a person vis-a-vis

another person/s

Ethics and Practices

Indian Code of Medical Ethics:

“ Confidences concerning individual or

domestic life entrusted by patients to a

physician and defects in the disposition or

character of patients observed during

medical attendance should never be

revealed unless their revelation is

required by the laws of the State.

3

CONFIDENTIALITY

Sometimes, however, a physician must

determine whether his duty to society

requires him to employ knowledge

obtained through confidence to his as a

physician, to protect a healthy person

against a communicable disease to which

he is about to be exposed. In such

instance the physician should act as he

would desire another to act toward one of

his own family in like circumstance.”

CONFIDENTIALITY

Courts have held disclosure not to be

permissible:

Held:

“ Victims ought not to be deterred by fear

of discovery from going for treatment

and free and informed public debate

about AIDS could take place without

disclosu re.”

CONFIDENTIALITY

IS DISCLOSURE PERMISSIBLE ?

Issue

Interest of the PLWHA to keep his HIV +

status confidential

v/s

Interest of the community, society, to have

knowledge of the the individual's HIV +

status

CONFIDENTIALITY

Courts have held disclosure not to be

permissible:

Held:

“ The persons receiving the confidential

information were not at risk of exposure

and therefore the disclosure was

unreasonable, unjustified and wrongful. ”

Jansen Van Vuuren

X v/s F; 11988| 2 All ER 414. QBD

Anr. v. Kruger

1993(4)SA 342

CONFIDENTIALITY

LARGER PUBLIC

INTEREST TO DISCLOSE

• In certain circumstances, disclosure

of information imparted in confidence

may be allowed ifpublic interest to

disclose outweighs public interest to

maintain confidentiality

Courts have held disclosure to be

permissible :

• Treatment/Interest of patient

Doctor to Doctor/ medical staff discussions

W v/s EdgeU & Ors,(\9M) 1 All ER 835 CA

• Statutory requirement/Notification

tauthorities

Hunter v/s Mann. (1974) 2 All ER 414 QBD

4

CONFIDENTIALITY

PRIVACY-SECRECYCONFIDENTIALITY

• Medical research approved by a

recognized ethical committee

• Partner Notification

• Public Safety/Administration of justice

Tarasoff v/s Regents of the University of

California, 17 Cal 3d 425

Held :

W v/s Edgell & Ors (1990) 1 All ER 835 CA

(i) At common law, the general rule is

that one person owes no duty to control

the conduct of another nor to warn those

endangered by such conduct;

PRIVACY-SECRECYCONFIDENTIALITY

PRIVACY-SECRECY

CONFIDENTIALITY

(ii) Exceptions arise where

(iii) Existence of a special relationship

between a doctor and a patient

(a) a special relationship exists between the

defendant and the injured part giving the

latter a right to protection, or

(iv) Duty to warn/protect the third party

(b) a special relationship exists between the

defendant and the active wrongdoer

imposing a duty on the defendant to

control the wrongdoer’s conduct

(vi) Duty to care to all persons who are

forseeably endangered

CONFIDENTIALITY

Mr. X v/s Hospital Z, (1998) 8 SCC 296

• Disclosure permissible to wife or

prospective wife as the fundamental right

of the right of the wife to lead a healthy

life outweighs the fundamental right of

the PLWHA’s right to confidentiality and

privacy

• the right which would advance the public

morality or public interest to be

advanced “AIDS is the product of

indiscipline sexual impulse ”

(v) Duty to warn patient’s family members

of a contagious disease

CONFIDENTIALITY

• Partner notification emerged as a public

health tool in the US in the 1930’s

• Rationale : allows identification,

treatment and education of individuals

who have been exposed to a

communicable disease

• Failure : Inspite of standard use of

partner notification for cases of syphilis

and gonorrhea and the existence of

effective treatment, the prevalence has

increased- CDC study

5

CONFIDENTIALITY

• Studies conducted in the US, reveal that

coercive HIV partner notification

programmes have failed.

• Recognition of the importance of public

health programs that encourage

voluntary partner notification

DISCRIMINATION

• Concept of discrimination is incorporated in

Articles 14, 15 and 16 of the Constitution.

These form part ofthe Fundamental Rights

Chapter (Part Hl) of the Constitution.

• Fundamental rights are available only

against the State (Article 12)

DISCRIMINATION

DISCRIMINATION

• Based on principles of natural

justice and equality

• Incorporates the American doctrine

of classification and the doctrine of

non-arhitrariness developed in

India

DISCRIMINATION

• a group can be divided into two classes ifthe

classification is based on an intelligible

differentia viz. an objective and rational

criteria

• the basis of the classification (the objective

criteria) itself must have a rational

relationship to the object of a statute

• The doctrine of classification is based on

the premise that equals should not be

treated unequally and unequals should not

he treated equally.

• Classification must satisfy the tests of:

(a) intelligible differentia - objective

criteria

(b) rational nexus - rational

relationship

DISCRIMINATION

• HIV status is certainly an intelligible

differentia to classify individuals into the

classifications of HIV-positive or HIV

negative

• whether or not classification on the basis

of HIV will satisfy the test of rational

nexus will depend on the facts of each

individual case

6

DISCRIMINATION

DISCRIMINATION

• MX v. ZYAIR 1997 Bom 406

• The doctrine of non-arbitrariness posits that the

statutes and state action must be fair, just and

reasonable (reasonableness doctrine)

• Reasonableness must be applicable to statute

(substantive reasonableness) and to state action

(procedural fairness)

• In India statute can be struck down as being

substantively and procedurally unreasonable

under Article 14 of the Constitution

DISCRIMINATION:

IN THE

HEALTHCARE SETTING

IS REMO VING AN HIV+

HEALTHCARE WORKER

FROM EMPL O YMENT

DISCRIMINA TION?

(employment scenario)

• The Bombay High Court held that actions must follow

the rigours ofArticles 14 & 21 of the Constitution and

followed the principles set down in School Board of

Nassau County, Florida et al. V. Arline, (1987) 480

U.S. 273

• In order for a person to be rendered incapable of

performing the job, s/he must be unable to perform the

job functions due to reported ailment, or pose a risk to

others at the time (“otherwise qualified” & “significant

risk”)

DATA ON TRANSMISSION FROM

HEALTHCARE WORKER TO

PATIENT

• CDC estimates risk of transmission from surgeon

to patient through stick or cut is between

I in 41, 667 and 1 in 416, 667

• CDC and AMA are currently reevaluating

policies in light of epidemiological evidence

showing that the risk to patients, even from

invasive procedures, is negligible

HIV-INFECTED HEALTH CARE

HIV-INFECTED HEALTH CARE

PROFESSIONALS

PROFESSIONALS

• For healthcare providers, risk is inherent in

every activity, including every medical procedure

Bradley v. University of Texas M.d. Anderson

Cancer Ctr.

• Significant risk must also be measured in the

context of the particular field of activity. The

acceptable risks in that field of activity would

establish risk threshold therefore comparative

risk must also be assessed

Bradley, a surgical tech, revealed that he was

HIVf. Soon after, the hospital reassigned Bradley

to another department. Bradley sued the hospital.

The Court held that Bradley posed a significant

risk to patients and that was sufficient reason for

him not to continue in that department.

7

HIV-INFECTED HEALTH CARE

PROFESSIONALS

• In India there have been no HIV/AIDSrelated decisions offering alternate

employment to healthcare workers but a

similar concept has been applied by the

Supreme Court

Anand Bihari v. Rajasthan S.R. T.C

Provision of Post Exposure

Prophylaxis (PEP) in Healthcare

Settings

DISCRIMINATION: EMPLOYMENT

• There is a common law duty for an

employer to provide a safe working

environment.

• There is a corresponding right of the

employee to a safe working environment

Recoxnmendations for Post Exposure

Prophylaxis (PEP) in Healthcare

Settings

-prompt management of exposure site

• In public healthcare institutions, PEP

should be made readily available for

healthcare workers

-evaluation of source & healthcare workerfor the need

for PEP

-baseline HIV test of exposed healthcare worker

-2 drug regimen - 2 NRTIs with possible use of Pl

• Healthcare workers should be trained

about allfacets of PEP

COMPENSATION FOR HIV CONTRACTED AT

THE WORKPLACE

• healthcare workers infected on the job couldfile suit

under common law for damages on the ground that the

employer had faded to provide a safe working

environment

■ hi India, healthcare workers are not covered by the

H 'orkinen 's Compensation Act

• Courts in other jurisdictions have considered such cases

for damages

» James r. Nolan

-initiated as soon as possiblefbefore 36 hours)

-4 week regimen to be completed

-follow-up with counselling, testing & medical

evaluation

Discrimination :

Healthcare Delivery

Setting

DOES REFUSAL TO PROVIDE

MEDICAL TREA TMENT TO A

PERSON LIVING WITH

HIV/AIDS AMOUNT TO

DISCRIMINA TION?

(healthcare delivery)

8

EXAMPLES OF HIV/AIDS-RELATED

DISCRIMINATION IN DELIVERY OF

HEALTHCARE SETTING

• refusal to treat

• inappropriate treatment

• physical isolation in wards

• early discharge

• delays in treatment

• conditional treatment

• prejudicial comments & behaviour

Duty to Treat

• Under Article 21 of the Constitution of India the

right to life and liberty includes the right to

health

• By law, State healthcare institutions/providers

are obliged to provide medical treatment to al!

persons in emergency and non-emergency

situations without discrimination

PUBLIC & PRIVATE HEALTHCARE

• According to National Sample Study, National

Councilfor Applied Economic Research 60 80% of healthcare is sought in the private sector

for which households contribute 4 - 6% of their

income

• Given the sheer numbers of HI V+ persons in

India, this will place an increasing burden on the

private healthcare system to provide treatment

for HIV+ persons

Duty to Treat

• There is a common law duty for doctors to

care where there exists a professional

relationship between the doctor & patient

according to the standard of care

• IVhere the person requiring medical

treatment is a stranger to the doctor and

there is no established professional

relationship, the doctor will not be liable

for refusing to treat the person

REFUSAL TO TREAT

• Private healthcare institutions/providers are not

obliged to treat persons except in an emergency

situations and until the patient can get other

medical help

(Parmanand Katara v. Union of India AIR 1989

SC 2039)

REFUSAL TO TREAT

• In the US, under the American Disabilities Act

(ADA), HIV is now recognized as a disability

• Disability under the ADA is defined as "an ...

impairment that substantially limits one or more

of fan individual's! major life activities”

• A person who is HIV+ is disabled and cannot be

denied medical treatment

(Bragdon v. Abbott)

9

MEDICAL TREATMENT

• In other jurisdictions where anti-discrimination

legislation exists it has been held that treatment may

be reasonably refused on several grounds:

- if a professional lacks the the skill appropriate to

render competent care, s/he may legally refuse to

treat the person and lawfully refer the patient

elsewhere

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Medical treatment is denied for the

following reasons:

»fear of occupational exposure

»lack of resources to provide adequate

treatment and protect oneself

significant risk posed to the healthcare provider

during the course oftreatment

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE

Risk of acquiring HIV infection from patients is

a function ofseveralfactors:

nature of the exposure

likelihood that the person is infected,

if so then:

viral load, stage of HIV infection

efficiency of the virus infecting the exposed

person

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE

• Latest CDC data on occupational exposure shows that

paramedical staff are actually more prone to

occupational exposure that physicians and surgeons

» out of 52 reported cases of occupational

exposure sero-converting to HIV: 19

laboratory workers, 21 nurses,6 physicians,

2 surgical technicians

» out of 52 cases: 45 percutaneous injuries

(puncture/cut) of which 41 involved hollow

bore needles

» out of 52 cases: 47 - HIV infected blood

OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE

• Epidemiological data suggests that the risk of

transmission through occupational exposure is

exceedingly low in low prevalence settings

• San Francisco General Hospital study of

surgical personnel showed cumulative risk of

0.125 per year (high prevalence setting - 10%)

(1 infection among staff every 8 years)

Prelimina.ry Recowniendations

• Development of anti-discrimination legislation

which covers the the private healthcare sector

• Development of welfare legislation which covers the

healthcare sector

• PEP be made readily available to all healthcare

workers at least those working in high prevalence

settings

10

An overview of

In health there is freedom.

Health is the first of all liberties.

Health and

Human Rights

Henri-Frederic Amiel, c.1850

Needs and Rights

Human Rights

Human rights are proposed entitlements that should

belong to every human being. Human rights are

ideally supposed to:

• Be mandated by international standards;

• Be legally protected;

• Focus on the dignity of the human being;

• Protect individuals and groups,

• Oblige states and state actors;

• Not be waived or taken away;

• Be interdependent and interrelated;

• Be universal.

In reality, rights are not always realised in this form!

i

Needs

Rights

& May or may not be met, not

obligatory

& Enforceable, once given

cannot be reduced

Identified by the provider

& The holder of rights has a role

in the negotiation

& Are fulfilled out of a sense of

benevolence of the provider

h Are fulfilled because the

holders have an entitlement

May be reduced according to

the dynamics of the situation

& Once given may not be

reduced, but are open to

expansion

Needs and Rights

Needs

& Lack of fulfilment becomes critical

only when a large section is

affected

& If the provider does not meet

needs, there are no direct

consequences

Needs do not directly confront the

system, may remain unmet if not

translated into rights

& Based on passive recipients, does

not lend itself to political

mobilisation

ffir1

Rights

& Violation of rights of even one

individual is a wrong

& There are consequences for duty

holders if rights are violated

& Confronts the status quo, once a

right is recognised, it is more likely to

be fulfilled

& For a right to be recognised requires

political mobilisation, hence rights

have the potential for political action

The Needs based approach and the Rights based approach ...

“When Ifed the poor, they called me a saint.

When / asked why they were poor, they called me

a communist. ”

- Archbishop Camara

1

Levels of obligations

Uaiied iMations

regarding Human rights

Three types or levels of obligations on States parties: the obligations

to respect, protect and fulfil.

The obligation to respect requires States to refrain from interfering

directly or indirectly with the enjoyment of the right to health.

The obligation to protect requires States to take measures that

prevent third parties from interfering with article 12 guarantees.

Article 25.

(1) Everyone has the right to a standaril of living adequate for the

health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing,

housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security

in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other

lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

Finally, the obligation to fulfil requires States to adopt appropriate

legislative, administrative, budgetary, judicial,promotional and

other measures towards the full realization of the right to health.

International Bill of Rights'

United Nations Declaration of

Human Rights

Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights

Covenant on Economic,

Social & Cultural Rights

The UN Declaration of Human Rights is supported by two binding

Covenants. These Covenants define the specific rights & responsibilities

of signatory Nations to uphold human rights.

Ml

(ESC rights were) “a response to the abuses and misuses of

capitalist development and its underlying, essentially uncritical,

conception of individual liberty that tolerated, even legitimated,

the exploitation of working classes and colonial peoples.

Historically, it is a counterpoint to the first generation of civil and

political rights, with human rights conceived more in positive

("rights to") than negative f’freedom from") terms, requiring

the intervention, not the abstention, of the state for the purpose

of assuring equitable participation in the production and

distribution of the values involved."

CP Rights and ESC Rights

Civil and political rights have been traditionally asserted

by the US and Western capitalist states ('First

generation rights')

Economic and Social rights were upheld to a much

greater degree by the erstwhile socialist states ('Second

generation rights’)

& These two types of rights need not be dichotomised, but

we should be aware that ESC rights are ‘Rights of the

poor and marginalised' and attack more directly at

exploitative structures

*You can kill a man by making him a

pavement dweller, just as surely as

you can kill him with a gun.”

2

,

strengths of the Rights approach

& A slogan like 'Right to Health Care' can be comprehended, at a

basic level, by anyone; the rights language has a strong

universal appeal

'if Empowers individuals, communities and organisations,

enabling them to demand particular health services

& Focuses on functional outcomes, and measures all policy

declarations in terms of what people actually receive

if Health services become understood as important public

goods, distinct from commercial services to be purchased in the

market

'Difficulties in taking a Rights

approach in the Health sector

No specific strong 'pressure group’ for Public health

& Consumer extremely vulnerable at the time of service delivery

Personalised nature of doctor-patient relationship

& Many quality related and technical issues involved

'it Health is a usually 'Off occassionally 'ON' priority

& A major group centrally involved - health care providers may

have strong sectional interests, resistance to change and attitude

of technical arrogance

How can we develop an understanding of

Human Rights in a “structural” context?

While ESC Rights are universal, their violation is very

much focussed on the poor and marginalised.

Addressing these rights would require an analysis of

structures - who is oppressing whom in the present

structure, and what kind of alternative social structure

are we demanding?

Strengths of the Rights approach

if Rights lend themselves to expansion and universalisation;

certain rights become a precedent for establishment of others

& The rights approach naturally strengthens the claims of the

most disadvantaged and vulnerable sections

if Rights once granted cannot be easily reversed though

policies and funding priorities may change

if The rights approach talks in terms of obligations and

violations, thus placing the responsibility to deliver on the

system.

Some limitations of the Rights approach

& May range people against the local providers like the ANM but may leave the

policy makers and global actors unscathed

Demand for rights may be partly met by introducing tokenistic reforms, an

attempt may be made to co-opt this demand as 'good governance’ without

making broader structural changes

& Rights are progressively realised; hence details of policies and implementation

need to be monitored and supported, which may require pro-people experts to

work with the system’. Danger of divide between the ‘experts' and the people

& Larger context of globalisation-liberalisation sets limits to public

expenditure and the possibilities of realising the right to health care

The movement for these rights has to he a collective activity

based on communit)’ and social mobilisation.

The Rights framework offers one way to anchor, broaden and

guide such mobilisation. But the Rights approach cannot

substitute for social mobilisation, nor can it avoid discussing the

real barriers to achieving rights in theform of existing social

and economic structures.

Struggles for social justice have been waged since times

immemorial. The Human rights framework is one more weapon

which can be used by the oppressed in their struggles for a new

society.

3

Exercise

Health is a reflection of a society's

commitment to equity and justice.

Health and human rights must prevail

over economic and political concerns.

& In your opinion, how does the striving for rights

by people throughout history relate with the

modern framework of human rights?

What is the relevance of this today?

- People’s Charter for Health

4

1

WHAT ARE ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS

•

Fair, safe working conditions;

•

Right to seek and choose work;

•

Right to form, join and act in trade unions;

•

“Social Security”, including government assistance during old age and in times of unemployment, and money or other help

for people at other times when they need assistance in order to live their lives with dignity;

•

Assistance and protection for families;

•

Equal marriage rights for men and women;

•

Adequate standard of living for everyone, involving adequate clothing, housing and food;

•

High standard of health and health care for all;

•

Satisfactory primary education for all and increased opportunities for further education;

•

Right to participate in the cultural life of the community; and

•

Right to benefit from scientific progress;

South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre/Asia Pacific Human Rights Network Training Session - July 2002

B-6/6, Safdarjung Enclave Extension, New Delhi 110029. India

Ph: +91-11-619-2717 Fax: +91-11-619-1120 Email: rnairsahrdc@hotmail.com Home Page: http://www.hrdc.net/sahrdc

2

UN COMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS

Mandate - Monitor the extent to which State Parties comply with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights; and

•

Formulate and provide general guidance to States on how to understand and comply with their obligations under the

Covenant;

•

Procedures - State Party must submit progress report to CESCR within two years of ratification of Covenant;

•

State Party must submit progress reports every five years;

•

CESCR assesses the performance of each State Party by examining the State Party reports as well as information from

NGOs and other UN agencies;

South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre/Asia Pacific Human Rights Network Training Session - July 2002

B-6/6, Safdarjung Enclave Extension, New Delhi 110029. India

Ph:+91-11-619-2717 Fax:+91-11-619-1120 Email: rnairsahrdc@hotmail.com HomePage: http://www.hrdc.net/sahrdc

3

HOW CAN NATIONAL IINSTITUTIONS (NI) PARTICIPATE IN THE WORK OF THE CESCR

In Their Own Country

•

Provide information and expert advice on economic and social conditions.

•

Provide information and advice to legislatures and legislators;

•

Prepare an alternative or “parallel” report to submit to the CESCR supplementary to the State Party report;

•

Annual report card on the performance of their country;

•

Urge to governments that annual budgetary planning respect the State’s obligations under the Covenant;

•

Lobby assistance from courts, tribunals and NGOs to prevent and remedy violations;

•

Develop friendly and cooperative relationships with members of public service;

•

Develop ties with the media to publicise and disseminate information and educate the public;

•

Develop communication networks with other National Institutions and NGOs to share knowledge and work on the same

problem from various directions;

South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre/Asia Pacific Human Rights Network Training Session - July 2002

B-6/6, Safdarjung Enclave Extension, New Delhi 110029. India

Ph: +91-11-619-2717 Fax: +91-11-619-1120 Email: rnairsahrdc@hotmail.com Home Page: http://www.hrdc.net/sahrdc

4

HOW CAN NATIONAL INSTITUTIONS PARTICIPATE IN THE WORK OF THE CESCR

Working in Conjunction with the CESCR

•

Provide information to formulate List of Issues identifying areas of concern with respect to a State’s fulfilment of its

Covenant obligations and serving to structure and guide the formal review session;

•

Provide information for the Country profile to help CESCR prepare for its review of Country record, in the form of

newspaper clippings, newsletters, or reports from the NGO or other National Institutions;

•

Participate in the Pre-Sessional Working Group (PSWG) by sending information about a State Party’s implementation of

the Covenant, submitting questions for the List of Issues, and making oral presentations at the PSWG meeting;

•

Shorter National Institutions/ NHRC briefs that do not amount to full reports provide valuable insight to the CESCR by

pointing to gaps or misleading data in a State’s periodic report;

•

National Institutions may submit a written statement, no more than 2,000 words, to the CESCR about its State’s periodic

report;

•

National Institutions may submit a detailed “alternative”, or “parallel” or “shadow”, report mirroring the State’s report;

•

National Institutions may make oral presentations during CESCR Sessions;

•

National Institutions may stay in the Conference room during CESCR review proceedings and advise the Committee on

follow-up questions during breaks;

•

National Institutions may publicise outcomes of the proceedings through the media;

South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre/Asia Pacific Human Rights Network Training Session - July 2002

B-6/6, Safdarjung Enclave Extension, New Delhi 110029. India

Ph:+91-11-619-2717 Fax:+91-11-619-1120 Email: rnairsahrdc@hotmail.com HomePage: http://www.hrdc.net/sahrdc

Engendering health

T.K. SUNDARI RAVINDRAN

THE term ‘gender’ is often used as synonymous with ‘sex’, male and female. Though the

two are indeed synonymous according to English language dictionaries, the term ‘gender’

has over the past three decades evolved into a concept different from ‘sex’. Ann Oakley

and others used the term gender in the 1970s to describe those characteristics of men and

women which are socially determined, as against ‘sex’ which describes biologically

determined characteristics. This distinction between sex and gender provides a useful

analytical tool for focusing attention on differences between women and men which are

socially constructed.

Many of the differences in men’s and women’s roles and responsibilities, norms and

values guiding appropriate behaviour and access to and control over resources, have less

to do with the fact that they were born male or female or that women alone can be

impregnated and bear children, and more with how society expects women and men to

behave. These in turn are derived from patriarchal ideology - a system of ideas based on

a belief in inherent male superiority. This ideology typically includes the belief that male

control over property is ‘the natural order of things’.

What do we mean by ‘engendering’ health or a gender perspective on health? The very

term suggests that it is not the same as focusing on women’s health, or even more

narrowly on health conditions exclusively experienced by women as a consequence of

their biology.

Traditional frameworks for analysing women’s health have often concentrated on the

childbearing years, and especially with health problems related to pregnancy and

childbearing. Besides their special health needs that are different from those of men due

to biological differences, women are also exposed to all the health problems that affect

men throughout their lifecycle. Thus malaria, tuberculosis, occupational and

environmental health hazards - all these impact women’s health needs too. In fact, since

infections such as malaria and hepatitis become life-threatening conditions for women

during pregnancy, they are issues of special concern.

A gendered perspective on health includes, besides examining differences in health

needs, looking at differences between women and men in risk factors and determinants,

severity and duration, differences in perceptions of illness, in access to and utilisation of

health services, and in health outcomes. ‘When considering the differences between

women and men (in health status), there is a tendency to emphasize biological or sex

differences as explanatory factors of well-being and illness. A gender approach in health,

while not excluding biological factors, considers the critical roles that social and cultural

factors and power relations between women and men play in promoting and protecting or

impeding health.’1

1

Why do we advocate engendering health? Few would disagree with the view that health

is a product of the physical and social environment in which we live and act, which is in

turn affected by the global and local environment: social, cultural, economic and

political. It is also widely acknowledged on the basis of studies conducted in diverse

settings that inequalities in health across population groups arise largely as a consequence

of differences in social and economic status and differential access to power and

resources. The heaviest burden of ill-health is borne by those who are most deprived, not

just economically, but also in terms of capability, such as literacy levels and access to

information.

Substantial evidence exists to indicate that in almost all societies women and men have

differing roles and responsibilities within the family and in society, experience different

social realities, and enjoy unequal access to and control over resources. It therefore

follows that gender is an important social determinant of health. Gender differences are

observed in every stratum of society, and within every social group, across different

castes, races, ethnic or religious groups.

Men and women perform different tasks and occupy different social, and often different

physical, spaces. The sexual division of labour within the household, and labour market

segregation by sex into predominantly male and female jobs, expose men and women to

varying health risks. For example, the responsibility for cooking exposes poor women

and girls to smoke from cooking fuels. Studies show that a pollutant released indoors is

1000 times more likely to reach people’s lungs since it is released at close proximity than

a pollutant released outdoors. Thus, the division of labour by sex, a social construct,

makes women more vulnerable to chronic respiratory disorders including chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, with fatal consequences? Men would in turn be more

exposed to risks related to activities and tasks that are by convention male, such as

mining.

Differences in the way society values men and women, and accepted norms of male and

female behaviour influence risk of developing specific health problems as well as health

outcomes. Studies have indicated that preference for sons and the undervaluation of

daughters skew the investment in feeding and health care. This has potentially serious

negative health consequences for girls, including avoidable mortality. On the other hand,

social expectations about male behaviour may expose boys to a greater risk of accidents,

and to the adverse health consequences of smoking and alcohol use.

Patriarchal norms which deny women the right to make decisions regarding their

sexuality and reproduction expose them to avoidable risks of morbidity and mortality, be

it through sexually transmitted infection resulting from coercive sex, or death from septic

abortion because access to safe abortion has been denied by state legislation. The practice

of unsafe sex by large sections of men who are aware of the health risks cannot be

explained except in terms of gender norms of acceptable and/or desirable male sexual

behaviour.

2

Because men and women are conditioned to adhere to prevailing gender norms, their

perceptions and definitions of health and ill-health are likely to vary, as is their health

seeking behaviour. Women may not recognise the symptoms of a health problem, not

treat it as serious or warranting medical help, and more commonly, not perceive

themselves as entitled to invest in their well-being.

Finally, because women and men do not have equal access to and control over resources

such as money, transport and time, and because the decision-making power within the

family is unequal with men enjoying privileges that women are denied, women’s access

to health services is restricted. They may be allowed to decide on seeking medical care

for their children, but may need the permission of their husbands or significant elders

within the family to seek health care for themselves. Restrictions on women’s physical

mobility, common in many parts of India, often makes it imperative for women to be

accompanied to a health facility by a male family member.

In many instances, biologically determined differences between women and men interact

with socially constructed behaviour to the disadvantage of women. This is best illustrated

in the case of sexually transmitted infections. Women are biologically more susceptible

to contracting a sexually transmitted infection than men. This is because of the shape of

the vagina and a greater mucosal surface exposed to a greater quantity of pathogens

during sexual intercourse, since the quantity of seminal fluid is far greater than the

vaginal fluid involved. Further, women with a sexually transmitted infection are more

likely to be asymptomatic and therefore less likely to seek treatment. Untreated and

undiagnosed sexually transmitted infections are the cause of chronic infections and

numerous long term complications suffered by women, including infertility and cervical

cancer.

There are other factors which compound women’s vulnerability because of the way

society expects women and men to behave. For a majority of women, high risk activity

can simply mean being married. Social norms which accept extra-marital and pre-marital

sexual relationships in men as ‘normal’, and women’s inability to negotiate safe sex

practices with their partners, are factors that make it difficult for women to protect

themselves from sexually transmitted infections. A study of STD (sexually transmitted

diseases) clinic patients in India (1992) indicated that a third of the women, all in

monogamous married relationships, were infected by their husbands, while the majority

of the male patients were infected by commercial sex workers and casual sexual partners.

Not a single man was infected by his wife? Men’s unwillingness to use condoms further

accentuates women’s risk. For example, in a study of the prevalence of and risk factors

for HIV infection in Tamil Nadu, India (1994-1995) covering a population of about

97,000, less than 2% of married men were found to be condom users? The stigma

attached to visiting an STD clinic together with other barriers such as lack of time, money

and decision-making power discourages women from seeking treatment.

3

deconstruct and reconstruct the normative premises of science (which is cognitive,

experimental and rational) and the law (which is practical and rational).22

Thus, by applying these definitions feminists are not only intervening in the classical

political arenas of the state and the market, but also challenging the dominant normative

forces which have the power to determine the limits and possibilities of transforming

contemporary societies. With this understanding, the boundaries and goals of the feminist

project will be clarified, and the theoretical and methodological instruments which should

be applied in the domains of analysis and action can be made more precise. Gender and

sexuality: fusion vs distinction

"An important barrier in our efforts to understand gender relations is the

difficulty in comprehending the links between sex and gender."

i

Given the significance of Cairo and Beijing for the feminist women's health movement, it

is important to discern what the implications are for the future. An important part of this

process is to explore the conceptual and political challenges that emerge in the face of the