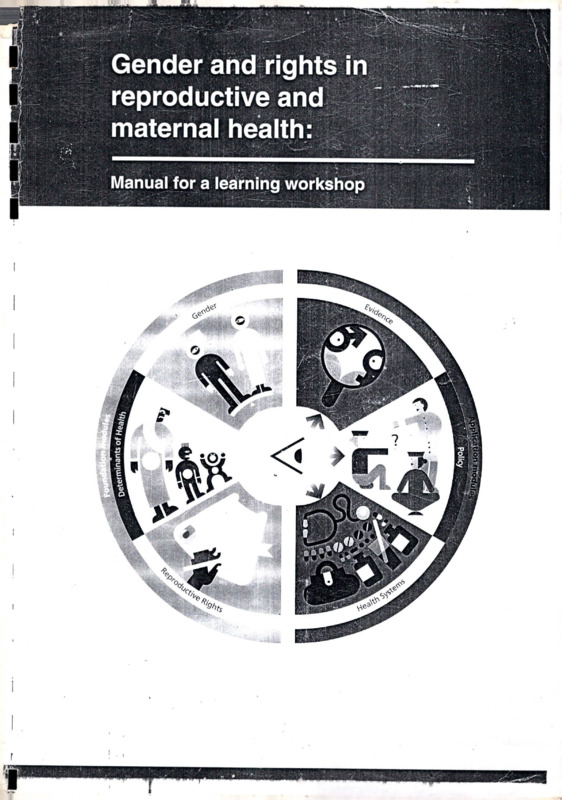

Gender and Rights in Reproductive and Maternal Health.

Item

- Title

-

Gender and Rights in Reproductive and

Maternal Health. - extracted text

-

Ja

,.IL JJIWiiLlll

■ >-•< ....

F/

■*•■!

i

■■’

;

.

,.

1

;■■

I

■

■

;i;

;>/

’

'■

<

■

.

■

, --

■ .

;.

'

1

'■••

>:

-'

■

■

' —

-

■'

areigy

■

-

■

■■.

.

■

■..

Manual for a learning workshop

•<

■

■

'

•'i-.. Is-,

■

■;_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ■

•ti

/

>

,

/

', <b

X

'■’I •g

I

£

I 42 io

c

co

.s

e

5

1

i o>

O

-

r

.. .,

o ■

.

Gender. and

.. ■ ■ nahts

a .. in.

reproductive and

maternal health.

Q

'

/

'

It-i

a

-?

\

10 J 14

+■

I

a

WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Gender and rights in reproductive and maternal health : a manual for a learning

workshop.

1. Maternal health. 2. Reproductive health. 3. Gender identity. 4. Women’s rights.

(NLM Classification: WA 310)

ISBN 978 92 9061 240 7

© World Health Organization 2007

lif

;

.

>■

•

•• -

RSI

1

■gg

ip

Ill

si

wi

All rights reserved.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do

not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part ol the World Health

Organization concerning the legal status ol any country, territory, city oi aiea, oi ol its

authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on

maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agieement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply

that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference

to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the

names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this

%es incurred as a

publication is complete and cc

result of its use.

Publications of the World He*

Health Organization, 20 Aver

2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; f

reproduce WHO publications,

or for noncommercial distribi

address (fax: +41 22 791 480i

Pacific Regional Publications

Publications Office, World HP.O. Box 2932, 1000, Manila

publications© wpro.who.int

Wi

Community Health Cell

Library and Information Centre

# 359, "Srinivasa Nilaya"

Jakkasandra 1st Main,

1st Block, Koramangala,

BANGALORE - 560 034.

Ph : 2553 15 18/2552 5372

e-mail: chc@sochara.org

Tess, World

41 22 791

nission to

ther for sale

he above

Western

i addressed to

stem Pacific.

1

■

Table of conV

Acknowledgements

Preface

Part 1. Learning modules

Objectives of the workshop

Workshop outline

Session 1:

Introduction to the cours

Session 2:

Maternal health: dimensk

Session 3:

Determinants of materna

Session 4:

Identifying gender and pc

underlying medical causes

Session 5:

A rights-based approach t

Session 6:

Engendering indicators....

Session 7:

Appling a gender and righ

functioning of a health cet

Session 8:

Health service delivery issi

Session 9:

Financing maternal health

Session 10:

Assessing policies and intci

gender and rights perspecti

Session 11:

Making change happen witl

Session 12:

Closing session

I

3

i

Part 2. Hand-outs

Session 1 Hand-out:

Session 2 Hand-out:

Session 3 I land-out 1:

Session 3 Hand-out 2:

Session 3 Hand-out 3:

Session 4 Hand-out:

i

I

Session 5 Hand-out 1:

Session 5 Hand-out 2:

Session 6 Hand-out 1:

Session 6 Hand-out 2:

Session 7 Hand-out:

Session 9 Hand-out:

Session 10 Hand-out 1:

Session 10 I land-out 2:

Session 10 Hand-out 3:

Session 11 Hand-out:

IL

The human tres

Definitions of sexual and reproductive

health and rights

Concepts for gender analy:■sis,

Gender and health analysis tool

Jasmine’s story

Gender and poverty dimensions of

medical causes of maternal mortality and

morbidity: Group exercises

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

A case study for analysing a reproductive

health intervention

Definitions of some maternal health indicators.

Developing “gendered” indicators

Guidelines for observation during visit

to health facility

Costing and financing maternal and

reproductive health services

Policy approaches to gender inequalities:

some concepts

I low different policies identify and

address gender inec|iialiiics

A framework for analysing policies

Making change happen within our own settings

57

59

62

66

67

69

74

76

78

80

82

S3

8-1

85

89

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

H4

4

3

a

»•

B

't

a

1

i

Acknowledgements

'This manual was prepared by T.K. Sundari Ravindran, with valuable contributions from

Jane Cottingham and Rashidah Shuib. The manual, developed for a 6-day workshop,

was condensed from the training curriculum for a 3-week workshop developed by

WHO Geneva, Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproductive health, a training

curriculum for health programme managers.

I

I

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable feedback on the shorter version

received from participants from 10 countries (Cambodia, China, Japan, the Republic

of Korea, the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic, Malaysia, MongoHa, Papua New

Guinea, the Philippines and Viet Nam) at the 5-day Regional Workshop on Gender

and Rights m Reproductive and Maternal Health from 28 November to 2 December

2005 held in Kuala Lumpur. These inputs have guided the development <)f this manual

for a 6-day workshop. The authors also express their appreciation to the Government

of Malaysia for hosting and supporting the workshop.

r

‘f

I

I

a

AA

-STfr

— aiiA-A

Preface

Globally, more than half a million maternal deaths occur each year, the majority of

them in developing countries. Within countries, it is the poor and disadvantaged who

suffer most. The majority ol these deaths arc prcvcniablc, even where icsoiik

:irc

limited.

Reducing maternal mortality has become a public health priority. Goal 5 of the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) calls lor improvements in maternal h< alih.

It also calls for a reduction in the maternal mortality ratio by 75% of the 1990 level

by 2015. To achieve this goal, a comprehensive approach to reproductive health

and improvements in service delivery and accessibility are needed. However, these

measures will not be sufficient by themselves.

It

|

Maternal mortality is like a litmus test on the status of women, their access to health

care, and the adequacy of health systems in responding to their needs. High maternal

mortality is a complex phenomenon, but all too often, it results from discriminatory

practices against girls and women. Women’s lack of power vis-a-vis men constrains

decision-making about their health needs. It also constrains the level of investment in

maternal health services and the quality of care women receive. Many studies indicate

that women’s low status is a major barrier to obtaining reproductive health services.

In other words, fundamental inequalities between men and women and the neglect of

women’s rights contribute to the morbidity and mortality of women. Poor women arc

doubly disadvantaged in their access to services, as well as in their access to and control

over economic resources.

It is crucially important to increase awareness of gender equality, to provide analytical

and practical tools for health programme managers and others to address gender and

reproductive rights. Moreover, it is vital to ensure both men’s and women’s participation

in these efforts.

This manual aims to achieve exactly this objective. It is based on the 3-week training

curriculum developed by WHO Geneva, Transforming health systems: gender and

rights in reproductive health, a training curriculum for health programme managers.

The longer course has been successfully conducted in various settings worldwide.

However, experience has highlighted the usefulness of a shorter workshop. The

course was thus condensed into a 5-day workshop to be conducted as a regional event.

It was hosted by the Government of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur from 28 November

to 2 December 2005. The workshop was expanded to the 6-day format presented in

this manual on the basis of the experience and feedback from participants in the Kuala

Lumpur workshop.

The manual is intended for use in facilitating a 6-day workshop on gender and rights

in reproductive and maternal health for health managers, policy-makers and others

with responsibilities in reproductive health. Other stakeholders working on advocacy

and policy and programme change in reproductive health, such as nongovernmental

organizations (NGOs) and international partners may also find it useful. Although

designed as a stand-alone course, it could be integrated with pre- or in-service

programmes on health systems, rights and gender.

1

|M

iSi;

Learning modules

t

■

'',!

'/

w

wR

it

B

i

I

0;bjv , -J—

t, ■

fH’r.

At the end of the wor..-s

•

,

; •

lie? pnf

be acquainted with the underlying gender,

social, economic and political

determinants of reproductive health;

have gained conceptual clarity on a rights-based and gender-sensitive approach to

policies and programmes for maternal health;

be

DC able

auie to

uo apply

apply the

the knowledge

knowledge and

and skills

skills gained

gained to develop strategies to address

gender and rights issues in maternal health within their own settings;

be able to review national maternal-mortality-reduction efforts and identify key

issues that need greater attention from a gender and rights perspective; and

have an understanding of gender- and rights-relatcd factors within the health

system.

J,

1

i

I

i

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

IF If

*

Hi

S’-

- J - - 4 •- ~ —

s

-

r

-;

3

-■W

(Jbjcciivcs

Participants will:

DAY 0 (a.m.)

Session I

()fficial opening and

• be introduced to each other,

to key facilitators and to the

objectives and structure of the

course

introduction to the

I'bi inat of activities

(ifticial opening

30 mins.

Brief ice-breaking exercise

40 mins.

Hxercise on expectations

course

20 mins.

Input on course: history,

objectives and structure

DAY 1 (a.m.)

Session 2

• gain a regional overview of the

topic and develop a common

understanding of the urgency of

addressing the problem

30 mins.

Input on dimensions of the MM

problem and key issues

30 mins.

Participants to read definitions of

sexual and reproductive health and

rights, followed by a discussion,

and summary by facilitator

1 h.

• be able to identify social

determinants of maternal health

and locate gender as one of

these, and be aware that it is

affected by and interacts with

other determinants

Introduction to gender concepts

and tool for gender analysis

f

1 h.

Spider s-web exercise and

subsequent discussion

lb. 30 mins.

• be able to analyse medical

causes of maternal mortality

and morbidity to identify their

gender and poverty dimensions

Exercise to identify gender and

poverty dimensions of medical

causes of maternal mortality and

morbidity

1 h. 30

mins.

• become aware that the

promotion or violation of rights

is easily identifiable and relevant

to everyone’s life

Participants work in pairs,

followed by large group discussion

45 mins.

• understand the relationship of

reproductive rights with human

rights

• understand the impact that

the promotion of rights or

violation of rights can have on

reproductive and sexual health

• be able to use a public-healthand rights-based approach for

identifying and solving problems

Brief input on basic concepts of

human rights and rights related to

safe pregnancy

Input, individual work and group

work interspersed with plenary

discussion

30 mins.

• be introduced to the concept of

“engendering” indicators

• have some exposure to

developing “engendered”

indicators

Input by facilitator

45 mins.

Group work to develop gender

sensitive indicators followed by

presentations and discussion

2h. 15

mins.

• be introduced to concepts of

sexual and reproductive health

and rights, and locate maternal

health issues within this broader

picture

Determinants of

maternal health

DAY 1 (p.m.)

Session 4

Identifying gender and

poverty dimensions

underlying medical

causes

DAY 2 (a.m.)

Session 5

A rights-based approach

to making pregnancy

safer

DAY 2 (p.m.)

Session 6

“Engendering”

indicators

30 mins.

Participants to share with their

partners experiences of their

encounters with maternal

mortality (MM) and morbidity.

Then some will share this with the

whole group. An attempt will be

made to identify associated factors

Maternal health:

dimensions of the

problem

D/XY 1 (a.m.+p.m.)

Session 3

I'iinc

t

i

4

I

!

I

Ih. 45 mins.

i

DAY 3 (all day)

Session 7

Applying a gender and

rights perspective to the

functioning of a health

centre (field visit)

I

DAY 4

Session 8

Health service delivery

issues

DAY 4

Session 9

Financing inaternal

health services

i

I

• become familiar with observing

and analysing various elements

of a health facility with a gender

and rights lens

Participants to visit health facilities

in small groups and carry out

systematic observation of the

quality of care, including whether

attention was paid to gender and

rights

3-4 h.

• understand what elements are

needed to make a health facility

address gender and rights

concerns

After returning from the field

visit, participants will report back

for a detailed discussion on what

they have presented

1 h. 30

mins.

• begin to look at health service

delivery issues through a gender

and rights lens

• understand gender and rights

issues within service delivery for

specific components of maternal

and reproductive health care

• be familiar with health systems

issues related to maternal health

from MDG Task Force report

Role plays: the health system

wheel exercise (modified to focus

on the relevant maternal health

issues)

1 h. 30

mins.

Input and participant seminars

1 h. 30

mins.

Input by facilitator, followed by

discussion

1 h.

Group reading of hand-out given

as homework, and discussion in

the plenary session

2h.

Brainstorming on what is a policy,

and on “gender and rights”sensitive policies

1 h. 30

mins.

Input on framework for analysing

and influencing policy

1 h. 30

mins.

• be introduced to strategies

and good practices in reducing

maternal mortality and

morbidity

Panel presentation by selected

participants

1 h. 30

mins.

• reflect on their role as

individuals in effecting change,

and address emotional and

psychological issues related to

making changes

Sharing of individual experiences

in making change happen and

summary input by facilitator

45 mins.

• apply what they have learnt

in the course to identify one

specific intervention that they

can implement in their own

setting

Briefing for working on one

specific intervention that they can

implement in their own setting.

Start and continue as homework

(making posters)

45 mins,

plus

homework

Group poster presentations

2h.

• Input session consolidating all

the modules

15 mins.

• Evaluation questionnaires to be

completed by participants

30 mins.

• Formal closing

45 mins.

• have an understanding of

the implications of different

financing mechanisms for

equitable access to pregnancyrelated health services

• be introduced to costing safe

motherhood and to innovations

in financing pregnancy-related

health care

DAYS

Session 10

Assessing policies and

interventions from

ii gender and rights

perspective

DAYS

Session 11

(p.m.) and

DAY 6 (a.m.)

Making change happen

within our own settings

I

DAY 6

Session 12

(a.m.)

•

Closing session •

• learn about the characteristics

of policies and interventions

that integrate gender and rights

concerns

• become familiar with a

framework for analysing policies

• consolidate what they have

learnt on the course

• evaluate the course from their

immediate perspective

■

Ww--------------- - ---------------------------------------

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

3

W ” ”

a

£

—r

5

■ *1

1

fil

It

1 j

‘f

Participants will:

be introduced to each other and to the key facilitators;

receive a brief introduction to gender issues;

learn something about the history and background of the course; and

be informed about administration and logistics.

|time: 2 hours]

a hand-out containing statements for the ice-breaking

exercise (see Box 1 below); and

a set of cards and pens for each participant.

I

There are *ree major activities to be covered in this session. The session should ideally be

toow anl t feVenffi8 b?°re

3CtUaI WOKsh°P StartS’t0

Plants to get to

know and to feel at ease with each other.

r

&

[time: 30 minutes]

Step 1: Facilitator’s welcome

[time: 10 minutes]

Welcome participants jand introduce yourself and other facilitators.

Brief participants on

the introductory activity.

I

I

Step 2: The human treasure hunt

[time: 30 minutes]

and talking to each other until tlJ

I

u PartlClpants move around ^eroom, stopping

sheets. The game can be stopped after about U)'

-vs

nthCSe Pe°ple °n

C

round out about the serous

f■ e C:SC'-:S5:Or-

- ; - .-kN ......................... .?re

l...> < x< ■_ oc .-..so

•a-.—>

c.m be drawn on, of reiponle?,™!

6

gender and rights in reproductive

.

•

.............-

r-

.

P1"1" emeprs. These

Manual tnrM—-------- • ■

I

r

I

I

'working woman (statement 5). Most would not h.ive h..d .. kind. ,,..

lt |lt , u|,.. u

male (statement 1), and so on. This f.n ilif.ncs the inm».|11< n. mi .(h<

..i ... ..J. ,

division of labour". Many women may not be engaged in acme spoils, and this < an be

used to introduce the concept of gender norms and roles. Mention that these issues will be

discussed in some detail during the next day’s sessions.

Box1. The human treasure hunt

(1) Find someone who had a male kindergarten teacher when s/he was growing up.

(2) Find one woman who is engaged in active sports.

(3) Find one man who takes an active role in his children’s school activities (for

parents).

(4) Find one person who has always had female bosses.

(5) Find two people whose grandmothers were working women.

(6) Find one person who has a woman employed as a driver or security officer in

his/her place of work.

ctivity 3: .

Step 1: Expectations

[time: 20 minutes]

Give each participant a card and a pen and ask them to write down their expectations for the

course. Pin these on to a bulletin board and go over them after mentally categorizing them.

Some of the categories of expectation that usually emerge are:

•

•

new information and skills;

group dynamics and learning processes; and

applying the information and skills gained on the course when back in the workplace.

Step 2: Introduction to the course objectives and structure

[time: 20 minutes]

This is an appropriate moment to introduce course objectives and content. These may

be presented in five minutes through a PowerPoint presentation. As you present the

content, explain at what point in the programme and how expectations about knowledge

and processes will be met. The facilitator of this session must be familiar with the course

content and methodologies as well as the timetable.

Fulfilling some expectations depends more on the participants than on die facilitators (for

example, Learning from each others’ experiences”). Some expectations are not likely to

be met. These may be about the content of the course, or extracurricular activities. It is

your responsibility to clarify which expectations the course cannot meet and to explain

that it is not usually possible to meet all the expectations of a diverse group. Bui it may

well be possible to accommodate some expectations - for example, a visit to a local

nongovernmental organization - even if these were not originally planned.

Step 3: Administrative and logistical matters

|time: 10 minutes]

Give information on logistics and administrative matters. You may include issues such as:

• who to talk to for which need: ideally, introduce the people responsible for logistics;

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

* »

it 4

A. A , A - A

w

■

A

m

A.

A - •« ■

a _

]

w

a

_

El

— . —.

T

.

—

7

la

•

•

•

tt

fc-

fc

f*

1

the resource room: what is available there (computers, printers, photocopier, telephone,

fax, e-mail, paper, additional reading matter), where it is and how it should be used;

per diem allowances and sponsorship, where applicable;

the physical location of the course venue in relation to other amenities such as banks,

travel agencies, restaurants, entertainment, and so on; and

any special health or diet requirements of the participants.

Go over the content of the course files with participants.

assignments and homework that will be a part of the course.

Explain the various

I

I

I

I

I

■f

I

fromTraiisjorniing health ^sterns:gender and rights in reproductive healths Opening module, various sessions. Geneva,

World Health Organisation, 2001.

8

IEAI

Workshop

Matemai h

> P -

I

I:

What participai

Participants will:

gain a regional overview of the topic and develop a common understanding of the

urgency of addressing the problem; afid

g

be introduced to concepts of sexual and reproductive health and rights, and locate

maternal health issues within this broader picture.

[time: 2 hours]

Materials

•

Hand-out: “Definitions of reproductive health and reproductive rights”

owerPoint presentation: Regional overview on maternal health issues

Flipchart for writing down 1key points from participants’ sharing of ideas on maternal

mortality and morbidity

How to run the session

i

level, and to become aware of the urgency of the issue. The second is an input prodding an

overview of the dimensions of maternal mortality and morbidity in the Region The third

Thfr H

tO in“OduCe C°ncePts of sexual and reproductive health and rights.

highlights the linkages between the goals of improving maternal health and promoting

sexual and reproductive health and rights.

! cavity 1

[time: 30 minutes]

Participants are requested to turn to their neighbours and share their encounters with

maternal mortality and/or morbidity. These may be their own experiences as health

providers, or as individuals, or based on what they have heard from colleagues, families or

community. This should take only about 10 minutes.

1

After 10 minutes, call upon participanls lo volunteer lo share whal lhey have discussed with

their neighbours. Write down on a Hipchart:

characteristics of the woman involved (age, socioeconomic status, parity, etc.);

cause of death — clinical as well as social;

•

place of death; and

•

whether the death could have been avoided.

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manua! for a Learning Worksho.

aa

R

a

n

:s

9

■«

M

Mi

ERB

1

»

Take about five examples and draw on these to highlight the human tragedy that maternal

mortality and morbidity’ represent. Note down the social determinants related to mortality

or morbidity in these examples (to discuss later in Session 3).

•/

|time: 30 minutes|

(Jive a PowcrPc )iiu presentation providing an overview of:

•

•

•

•

maternal mortality reduction in the MDG;

maternal mortality and morbidity rates and causes in the Region;

inequalities and differences across geographical areas and population groups; and

an agenda for action to change the situation.

An overview paper may be prepared and circulated as a hand-out if considered useful.

[time: 1 hour]

It is important to point out the link between maternal health issues and the broader concept

of reproductive health before finishing this session.

Hand out definitions of reproductive health, sexual health, reproductive rights and sexual

rights. These must include paragraphs 7.2 and 7.3 of the International Conference on

Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action and paragraph 96 of the

Fourth World Conference on Women (FWCW) document from Beijing. You may note

that the language of sexual rights is not used in the FWCW document. However, people in

the field talk about paragraph 96 of the FWCW' document as “the sexual rights paragraph”

because it is about applying human rights to the area of sexuality.

Participants should read the definitions and clarify any doubts. You then make the link

between reproductive and sexual rights and health and maternal health - highlighting how

one cannot be achieved without the other. Safe pregnancy and child-bearing depend on the

woman’s ability to decide whether and when to get pregnant and how many children to have.

I Ik y also depend on her ability to terminate unwanted pregnancies safelv, her access to care

following a miscarriage, and so on. A woman’s reproductive and sexual health throughout

her lifetime influences and is influenced by maternal health and overall health status.

I

10

a

»

w

* ■r H O’ k j k ■ Si

■i 3 i!

Participants will:

•

•

be introduced to gender concepts and to a gender-analysis tool; and

identify social determinants of maternal health and locate gender as one of these, and

be aware that it is affected by and interacts with other determinants.

[time: 2 hours 30 minutes]

■ i

Hand-out 1: Concepts for gender analysis

Hand-out 2: Gender-analysis tool

PowerPoint: Introduction to gender concepts and gender-analysis tool

Word document to project (overhead or LCD): Case study of a woman experiencing

maternal mortality or serious morbidity

a ball of twine or wool and a pair of scissors

This session consists of three activities. The first is an interactive discussion with inputs

from the facilitator on gender concepts and the gender-analysis tool. The second is a

participatory exercise known as “the spider’s web”. It involves reading out a case study of

a woman suffering from ill-health, and unravelling the factors that contributed to it. The

activity illustrates how so many factors are intertwined, using the analogy of the spider’s

web. The third activity is a whole-group discussion to help participants understand both the

links and the differences between sex, gender and other social determinants of health.

[time: 1 hour]

Step 1: Definitions

[time: 30 minutes]

Start with a brainstorming session on what participants understand by “gender” and write

their responses on a flipchart. Ask participants whether they know how “gender” differs

from “sex”, and elicit a few examples of such differences.

Distribute Hand-out 1 to participants and allow them about 10 minutes to read it individually.

It contains definitions of commonly used gender concepts: the gender based division of

' labour, gender roles and norms, access to and control over resources, and power. Clarify

any doubts or questions that participants may have.

Conclude this step wilh a summary I’owcrPoinl prcscnlafion wilh dclinilions of sex and

gender and of gender concepts given in Hand-out 1.

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

M

W''1WW

H

II

Step 2: Gender-analysis tool

|iimc: 30 minuics|

I )isliil)iiic I land out 2, which contains one gender analysis tool and also an example of how

the tool is applied to make a gender analysis of one health condition: malaria.

I ul up an overhead or PowerPoint slide ol the gender analysis tool (matrix) and take

participants through the matrix, (live enough time for questions and clarifications.

[time: 1 hour 30 minutes]

Step 1: Divide up the room before the session begins

The floor of the room is divided into five large squares or rectangles. One-half of the

room is assigned to three factors that women have in common with men of the same

social group: economic, sociocultural and political factors. These are marked on the three

squares or rectangles on the floor. The other half of the room is divided into two squares

or rectangles, marked “sex” and “gender”.

Floor plan:

SOCIOCULTURAL

ECONOMIC

POLITICAL

GENDER

SEX

Step 2: Briefing

[time: 10 minutes]

I

i

I'.xplatn that this session builds on the earlier session in which the various social determinants

of maternal health were identified after participants shared their personal experiences.

Explain also that it aims to show the interlinkages between different determinants of

maternal health, including gender. Get participants to stand in a wide circle around the

floor plan. As facilitator, you will be standing at the centre of the floor plan. You should be

facing the screen on which the case study will be projected.

i

Step 3: Case study

[time: 20 minutes]

Project the case study, which has the potential to provoke discussions on sex and gender and

social, cultural, economic and political determinants of maternal health. One example of a

< asc Sludv ispiv.-n in Hox

used here as an illustration.

i

I

I <

i"'.

y

I

Box 2: Jasmine’s story

Jasmine was only 20 years old when she died. The first of three daughters of a

poor agricultural labourerjasmine had studied only up to second standard. Her

father could not afford it. The school was two kilometres away from her street

and it was not considered appropriate for her to go unescorted. Her father also

thought that educating a daughter was like “watering the neighbour’s garden”.

When she was 16 years old, Jasmine was married to a rich man of the peasant

caste. She was his second wife. Jasmine’s father was only too pleased at his

daughter’s good fortune.

Jasmine bore two children in quick succession. The first was a girl and the second,

the much awaited male heir. This she did even before her nineteenth birthday.

Both the children were born at home. When her son was just eight months old,

Jasmine discovered that she had missed her periods for more than two months.

She did not want to be pregnant again because her son was sickly, so she talked to

a traditional midwife.

The traditional midwife suggested going to a private practitioner 10 kilometres

away for an abortion. Jasmine had never gone anywhere outside unescorted, and

she had to wait for a day when the midwife was able to come. Jasmine went there

under the pretext of having her son immunized. The private practitioner was

willing to perform the abortion, but her charges were unaffordable for Jasmine.

i

,

Jasmine returned home desperate. She attempted an abortion on her own,

inserting a sharp object into her vagina. Within a week, Jasmine became very

sick. When the pain started to become severe, Jasmine knew that she would need

medical assistance. However, she hesitated to ask her husband to take her to

the town hospital, because she did not know what explanation to give him. Her

relationship with him was strained; she had heard that he was “seeing” another

woman because Jasmine had become “sickly”. So Jasmine took some medicine

for fever bought from a local store, and kept quiet. A couple of days later, Jasmine

died of high fever without receiving any medical help.

J.

Demonstrate how the spider’s web exercise works with one or two examples. Stand at the

centre of the room with a ball of wool or twine. The participants take turns to read the

case study in parts, and after each sentence or each couple of sentences, you call out, “But

why?”

For example:

i

\'(icililalor:

Participant 1:

jasmine slopped schooling alter her second grade. Bui why?

Her school was three kilometres away from the village.

Facilitator:

Participant 2:

But why?

The village was a poor one, far away from the capital city.

'I’hc person giving this last answer has identified a reason that could be classified as economic

— the backwardness of the village, or as political — the village’s lack of bargaining power to

secure resources.

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

9

”T T

RD

13

r. M u

4

I

As soon as the participant identifies that the reason is that the village is powerless, the

facilitaU >r asks, “Sc > he >w wc mid yc m classify this I a ch >r?” The participant may say “economic”.

As s< >< m ns he < >r she says I his, l he perse m goes and siai ids in I he square marked “cconc >mic”.

I he lac 1111; 11 < >i, si a nd 11 ig al 11 ic cenl re wil 11 I Ik* ball < >1 I wine, he >kls < >nc end ol l he I wine,

and I brows I he ball lo I he participant standing in the “economic” square. You may probe

further, and ask “Can you classify it as any other factor?” Another participant may say

political . She or he should go and stand in the “political” square, and the person standing

in lhe “economic ’ square throws lhe bail lo her or him, while holding on lo the twine. Now

all ihrce arc linked b\' lhe (wine.

There is another reason why Jasmine stopped schooling - her father did not think educa tion

was necessary for girls. This would be classified as “gender” and the ball would pass on

from the person in the “political” square to the person identifying this factor and occupying

the “gender” square.

!

I

Tliis continues, until by the end we are left with a complex spider’s web of factors underlying

Jasmine’s death.

The activity should be conducted at a brisk pace, with each “But why?” following in quick

succession, the factors classified and a new participant coming into the web.

You should decide before the activity at which points you will be stopping to probe “But

why?” Restrict this to no more than 10 or 12 questions.

Step 4: Cutting the web

[time: 20 minutes]

\X hen the spider’s web is complete, challenge participants to find points at which they can

cut the web. What intervention could they make that would make a difference to Jasmine’s

situation? This could happen while the participants are still standing entangled in the web.

Facilitator:

Participant:

If you were a local activist, where would you cut the web?

Facilitator:

Participant:

If you were the nurse at the local clinic, where would you cut the web?

I would be sensitive to the ways in which gender influences women’s ability to

I would intervene to help Jasmine become economically independent.

prevent unwanted pregnancies. I would do all I could to ensure that women

seeking abortion services were not sent back home without receiving the

service.

/ 'iitiliLiloi

I'.n lit if ><1111

\i

II you were from ihc Dcparimcm of I Icalih of the national government,

when- would you cui the web?

I • would :idvo< ai<- lor liberalizing lhe laws on abortion.

I .

A'. <"1.1,

;||||< ||>

;,|1| answers, cut

Ii |>

|>;iiii(

i|);uii

cm her or him free.

l>=""'

14

3

i] a

After three

remrii io their senls for <lei.riefing and discussion.

a;

or four such examples,

Activity 3: Whole- r<

;i I 4

[time: 40 minutes]

i

Step 1: Participants give feedback

[time: 15 minutes]

i

Encourage participants to start by sharing their feelings about the <exercise. I low did they

feel when they were entangled? I low did it feel to cut the web atI specific points? What

lessons do they draw from the exercise? What do they think the erntanglement signified?

Participants usually share their feeling of being hopelessly trapped as the spider’s web

was being constructed, and feeling that they would never be able to unravel the problems.

Cutting through some parts of the web gives insights into possible actions that individuals

or groups can take - no matter how complicated a situation appears or at which level a

person is able to intervene: individual, community or national.

Step 2: Facilitator summarizes

[time: 25 minutes]

Where to start

I

Point out that the key to cutting the complex web may lie in starting with the woman herself.

This would create greater space for her to reflect on her situation, interact with others and

facilitate her empowerment, helping her see that change was possible.

Draw attention to the fact that in the spider’s-web exercise, many gender factors were also

classified as sociocultural: for example, the reason for Jasmine’s early marriage. This point

should be raised for discussion - that culture and tradition are not gender-neutral and may

become tools for discrimination against women. They are likely to be the parts of the

spider’s web that are the most difficult to cut through.

Economic, sociocultural and political factors that affect women’s health are so intertwined

with factors related to gender and sex that they seem to mesh into one. While it is important

to see these links, it is equally important to separate them out analytically so that we can

identify where it is most feasible and appropriate to cut the web.

• social

■■■•• r

Draw participants attention to the links between a social-determinants perspective and a

rights framework (introduced in the next module) in relation to health. Understanding the

social causes underlying ill-health also helps us identify the economic, sociocultural, civil

or political rights involved. Violating or neglecting these may underlie the health problem.

Addressing these violations or neglecl would create conditions to enable good health.

i

Adapted from Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproditctivc health. Mod/de 2, Session 4 Geneva IT'f-fO

200!.

d

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

'Mr

n 3

a

J-

n~ .i

..

'

I

c -

I

75

• !>•

»»•

m■■

J

r

I

Participants will:

•

be able to analyse medical causes of maternal mortality and morbidity to identify their

gender and poverty dimensions.

[time: 1 hour 30 minutes]

•

Hand-outs 1-4, each describing one situation of maternal morbidity

Flipcharts

Phis session starts with a small group activity in which participants explore a health problem

and identify gender and poverty factors underlying many medical causes of maternal

mortalin’ or morbidity.

|time: 50 minutes]

Step 1: Instructions for the activity

[time: 10 minutes]

Divide participants into four groups. Distribute I land-outs 1-4 with instructions for group

work. Each group does the same exercise but for different maternal health problems Their

main tasks are:

to analyse the reasons underlying a negative maternal health outcome; and

to identify and circle in red factors that are related to poverty; and circle in blue factors

that arc related to gender.

i

I

I

1

Step 2: “But why?”

[time: 40 minutes]

Starting with the statement written at the bottom left corner of a 1'arge sheet of paper

groups ask “But why?” They write the reason in a bubble next to the statement.

f

/6

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MAT

K-,''. J

for a Learning Workshop

■■

1

I

They keep asking “But why?” until the line of argument is exhausted. Each reason has to

flow directly from the one before, to be written in a bubble and to be clustered next to the

others. Then participants begin with the original statement and explore another reason why

the woman experienced a negative maternal health outcome.

Participants must give as many reasons as possible in as much detail as possible. Each circle

should contain a single specific issue. For example, “culture” is not acceptable as a reason:

the group must define what it is about the culture that is the reason in this specific instance.

For example, it could be that women arc expected to have sex whenever their husbands

want to.

The following is an illustration of how this exercise is done for a problem related to

infertility.

av -<

Afraid of

asking

husband

!

No

clinic in

the area

No money

Did not tell

health worker,

her symptoms

J

Did not go to

the clinic

1

Health workers

judgemental

Went to the

clinic, but

got no

treatment

Woman infertile

because of untreated

STI

No privacy

Health worker

could not diag<

nose

No drugs

Did not know

she had an STI

STI was

asympto, matic

No resources

Poor

ordering

system

[time: 40 minutes]

Each group in turn presents one problem and the chain of events. Ask questions after

each presentation, challenging participants to clarify their line of reasoning. Explain how

gender and poverty influence the health conditions. Each report and related discussion

should be completed within 10 minutes or so. The facilitator summarizes at the end of each

presentation and discussion.

New activity based on an exercise from WHO. Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproductive health.

Module 6, Session 3. Geneva, WHO, 2901.

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual fora Learning Workshop

f"”

J

«« •

■

77 1

17

Participants will:

•

•

become aware that the promotion or violation of rights is easily identifiable and relevant

to everyone’s life;

understand the relationship of reproductive rights with human rights;

understand the impact that the promotion of rights or violation of rights can have on

reproductive and sexual health; and

be able to use a public health- and rights-based approach for identifying and solving

problems.

I

|timc: 3 hours|

Hand-out 1 of the Universal declaration of human rights — this can be downloaded

from www.unhchr.ch/html/intlinst.htm

Hand-out 2: “A case study for analysing a reproductive health intervention”

Overhead or Word file for projection: Four quadrants

Flipchart or board to write on

PowerPoint presentation on the Right to Health and its application to maternal health

Essential reading as homework on the day before the session:

(a) Freedman I ,.P. Shifting visions: “delegation” policies and the building of a “rightsbased” approach to maternal mortality. Journal of the American Medical Women’s

Association, 2002, 57(3): 154-158 (enclosed)

(b) UNICEF. Saving women’s lives: a call to rights based action. UN Regional Office

for South Asia, 2000: 9-19

This session consists of three activities. The first is conducted in pairs to identify rights

violations, foDowed by a discussion with the whole group. The second activity is an

interactive input by the facilitator on the “Right to health and rights related to safe pregnancy

and delivery . In the third activity, participants work individually and in groups, interspersed

with facilitator inputs.

|liinc: 'IS ininulcs|

Slop 1: Working in pairs

|lllin

11H'

I ‘i llilliilh '.|

iH

i

• I' •' iHiii in

IS

i« in n\

-.I

lid l.ll.i

I ‘ ii n< i| • ini'. w • >1 I

I ’■l“

vul*1 ,l“ lc*c,c,’<c or access to anv human rights

"(Hx Miu.inon, in winch ihcy led a sexual or

OBNOE. Aro RIGHTS m REPROOUCTM ARD ETERNAL KEALTR,

L<»r„,„0 Wo,tehM

--

I

I

I

I

reproductive right was violated. These may be based on their own personal experiences or

on the experiences of others.

Ask each participant to spend two minutes alone recalling one incident when s/he felt

that a right was violated, and to share this with his/her neighbour. The person sharing the

recollection should try to name which rights she or he thinks were relevant to the story and

in what ways.

Step 2: Whole-group feedback

[time: 15 minutes]

Ask participants to volunteer to share stories about what they consider to be violations of

rights that impact on sexual and reproductive health, or about the violation of reproductive

and sexual rights. Some examples that have previously come up include:

the right to choose one's marriage partner, and not be forced into an arranged

marriage;

the right to use a contraceptive method of one's own choice without overt or covert

coercion from the health system;

the right not to be discriminated against in the labour market because of having

children;

the right to be informed when one's partner tests positive for 11IV; and

the right of health workers to be protected from HIV infection.

•

•

•

•

•

Step 3: The Universal declaration of human rights

[time: 15 minutes]

Hand out copies of the Universal declaration of human rights (UDHR). Participants take

five to seven minutes to read it individually. Tell them to skip the preamble and to begin

reading at Article 1.

Go over each of the rights listed on the board or flipchart and ask participants to identify

which article in the UDHR most closely addresses it.

[time: about 30 minutes]

Prepare a PowerPoint presentation on the right to health and rights related to safe pregnancy

and motherhood. The main points to be covered in this presentation include:

•

•

•

•

I

the meaning of the right to health;

the state’s obligation to respect, protect and fulfil individuals’ right to health;

application of human rights principles to maternal and reproductive health: some

examples of rights involved; and

an explanation of what the “value-added” is when a rights-based approach is adopted

. to sexual and reproductive health programming, with illustrative examples.

'’I,r

*

3

I

4;

ak

i

B

n

V(J]

i

I

[time: 1 hour 45 niinutes]

Step 1: A methodology for maximizing the public health and human rights

elements of policies and programmes

|time: 20 minutes]

Introduce participants to the following methodology.1 It attempts to maximize both the

public health and human rights quality of policies and programmes. There are four steps:

(1) Considering the extent to which a policy or programme represents good public

health.

(2) Considering the extent to which it is respectful of and promotes rights.

(3) Considering how to get the best balance between health and rights.

(4) Considering whether this is the best approach for dealing with the public health goal

that the policy or programme seeks to address.

This [overhead] chart helps you go through the steps:

Four quadrants: The quality of human rights and public health in a

programme

Excellent

c

A

D

B

Poor

0

Poor

Excellent

Sector explanations:

A: best case

B: need to improve HR quality

C: need to improve PH quality

D: worst case: need to improve both PH and

HR quality

vertical axis: human rights quality

horizontal axis: public health quality

quadrant A: optimal human rights and optimal public health

quadrant B: excellent public health, but human rights aspect needs to be improved

quadrant C: human rights aspect is fine, but public health suffers

quadrant D: bad public health and bad human rights

rh/s methodology is adaptedfrom: International Federation ofRed Cross and Red Crescent Societies and the Francois-Xavier

Ragnond Centrefor Health and Human Rights. The public health-human rights dialogue. In: Mann J.M., Gruskin S.,

(,rodin I. I., \nnas (>f. eds. I lea/fh and human rights: a reader. Xew ) brk, Routledge, 1999:46-53.

20

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

—___ __ .. .

________ _

*i

___ '__________________

T”’

The assumption is, generally, that in designing and implementing a health policy or

programme, quadrant A is where one would prefer to be. A programme or policy that is

respectful of rights, while still achieving its public health goal, is going to be better than one

that limits or restricts rights.

How do we use the chart to work through a policy or programme in order to maximize both

the public health and human rights aspects?

The first step: What makes a good public health intervention?

Mark the extent to which the policy promotes and is good for public health as i.a point 7

P

along the horizontal axis (see Figure 1 below). If the point lies within quadrant^, this

indicates good public health quality, and the further right the point, the better it is. If the

point lies within quadrant D, this indicates p<

poor public health quality, and the further left the

point, the poorer the quality.

Excellent

I,

I

c

A

D

B

Poor

0

Poor

Excellent

The second step: Consider the rights aspect of the policy

Consider the rights aspect of the policy and mark this as a jpoint Q

~ along

*

the vertical axis

(see Figure 2 below). If the point lies within quadrant C, this indicates good human rights

quality, and the further north the point, the better the human rights quality is. If the point

lies within quadrant D, this indicates poor human rights quality, and the further south the

point, the poorer it is.

Excellent

c

A

D

B

Poor

0

Poor

Excellent

Suggest that determining the human rights value of a policy or programme can be done

by considering each of the rights in the UDHR and determining for each right whether

it is positively or negatively impacted upon, or irrelevant. Ask participants to remember

government obligations as well as the Siracusa principles. Make it clear that sex-based

discrimination in the UDHR should be integrated across rhe various relevant rights in the

UDHR.

-■111

l

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

H

21

r - .3

The third step: Where public health and human rights intersect

I haw a vcriical line from P on the horizonial axis and a I

horizontal line from O on the

vertical axis. 1 he point of intersection of these two lines, R, gi

ivcs the quadrant in which the

policy lies for its public health and human rights quality (sec 1‘igure 3 below).

Excellent

I

e

A

D

B

Poor

0

Poor

Excellent

i

The goal is to be tn quadrant A or move towards it by working through the various aspects

or the policy.

d'JCtive

[time: 1 hour 25 minutes]

‘f

Step 1: Assessing the quality of public health

[time: 10 minutes]

G.VC each pamapant a copy of a case study of a health intervention with instructions for

analysmg its public health and human rights quality. The hand-out given here is an example

WMe the steps for analysis stay the same, you may wish to substitute this case study with

another.

]

Parac^ants complete the public health analysis of the intervention. They may discuss this

vnth their neighbours before reaching a decision.

Step 2: Whole-group discussion on public health quality

[time: 20 minutes]

After participants have analysed th<ie public health quality of the intervention, they move

into a whole-group discussion.

mtervend<C>nP‘mtS

qUeSti°nS’ Which are Iinked to the Pubhc health quality of the

What arc the reasons for focusing on this population?

22

111W

Ii

presumption that they are at a higher risk of being infected;

large number of sex partners from whom and to whom they could presumably

receive or transmit infection;

real or perceived lack of power to negotiate condom use with clients;

increased likelihood of having other STIs: assumption that they are more likely

than other people to contract HIV and spread it to others (their clients); and

politically expedient: looks like something is being done.

•

Why not focus on testing clients?

•

•

Is there likely to be pre- and*post-test counselling?

What test is likely to be used? How accurate is the test given at six-monthly intervals

likely to be?

Will all sex workers be tested? Which sex workers arc likely to be identified?

What happens to sex workers once they are found to be infected?

•

•

If their sex workers’ cards are removed, are these women likely to find other

sources of financial support immediately? Why do women generally engage in sex

work? Will this need go away if they are found to be infected? Will revoking their

cards impact on sex workers’ ability to use health and other services?

Does this approach in any way control the clients’ rate of transmission to these

women?

Given the health commissioner's concerns, is this approach likely to be effective in

preventing heterosexual transmission?

Put up your [overhead] transparency of ‘Tour quadrants: The quality of human rights and

public health in a programme”. What is the level of consensus among participants on the

public health quality of the intervention? Call out at each point beginning with O along the

horizontal axis of the chart, running your pen along the axis. Ask participants to raise their

hands when they think you have reached the quality of the intervention. Mark this point on

the horizontal axis. Let this point be P.

Step 3: A rights analysis using the UDHR

[time: 10 minutes]

Now ask participants to carry out a rights analysis of the intervention using the UDHR.

Are any of the rights being restricted? If yes, are these restrictions valid under the Siracusa

principles? Participants work individually, consulting with their neighbours if they want to.

Make it clear that sex-based discrimination, which a gender analysis would reveal, is included

in this analysis.

I

Step 4: Whole-group discussion on human rights quality

[time: 20 minutes]

Facilitate a discussion in the large group on the human rights quality of the intervention.

I

I

Rights to be considered and discussed include Articles 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 20, 21,

2.2, 23, 25, 27 and 29. While many of these rights may not be immediately relevant to the

example provided, a discussion will allow consideration of the proposed intervention from

a rights framework.

i

I!

II

GENDER AND RIGHTSJN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

h

A

1

I

a

I 23

-

Sn5iXenSoS

d io

at

If ■’«

1

hUman ri9hts -‘-sect for

[time: 10 minutes]

and T.

] tranS^rCnCV of “Four quants: The quabty of human rights

he co

f “a

P -w marked on it. Deterge

the consensus for the human rights quality of the intervention. Call out at each point

beginning with O, along the vertical axis of the chart, running your pen along the axis’

Ask parents to ntise their hands when they think you have rcLhed the quality ofThe

intervention. Mark this point Q on the vertical axis.

*

Draw a vertical line through point P and a horizontal line through point Q. Mark the

quadLt “L" WR°' rdS

!? ’^htheCaSe

ln thC hand'°Ut> thiS P°int R is

to “

mterV£ntiOn iS °f P°Or Pubhc heal* - weU as poor human

Lhl quX

Step 6: Discussion: How to move towards quadrant A

fume: 15 minutes]

Focus the discussion on 1what specific changes would be needed for this intervention to

move towards quadrant A.

*

How can we make the public health objective re:

spond to the problem in a manner that

is as targeted, precise and gender-sensitive as possible?

How can we make the response to the problem more effective?

™se ™ f™p™“ ””ly°'

d“ '■

“d"“ -e

'

ta™“„>"proins

»>

”d d“™df ■>»

d“ ” d" P“b“' “«■ vAy »f

I articipants may propose a number of different options. You can discuss each of these

in relation to whether they are of a better public health and human rights quality *an

*e “ample. Anonymous voluntary testing and counselling sites available to the generd

p pulaaon, including sex workers, and the promotion of condom use are usually ten as

£“””sh“ ”d p“Mc

H“^ *” -Ib'

*»

Policies and programmes that respect rights are ;

actually better and more effective. Human

nghls and public health concerns arc not incompatible.

24

I

..........

r

>1

Considering human rights in the design, implementation or evaluation of health policies and

programmes is a useful way to determine whether existing health policies and programmes

promote or violate rights (especially gender equality) and to judge their effectiveness.

Public health decisions are often made for political expediency, without consideration of

their effects on human rights, and even to some degree their effect on public health.

U)h!>

•

People working in public health have a responsibility to look at whether human rights

are promoted, neglected or violated by actions taken in the name of public health.

•

The links to the government that exist for anyone working in public health, whether

as an agent of the state or because they receive government funding, impose a dual

obligation to promote and protect health, as well as to promote and protect human

rights.

•

People working in public health have the power to decide to restrict rights, so this

responsibility has to be taken seriously.

Health policies or programmes that violate rights have long-term negative

consequences in that they make it harder for people and communities to trust any policies

or programmes.

J.

Adaptedfrom Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reprod/tcfire health. Module 5. Sessions I, 2 and I Genera,

U'/HO, 2001.

'Ji

GENDER AND RIGHTS |NJREPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

’f- 7

3

W

^4

a

D

I 25

■= r-

f

Participants will:

•

•

be introduced to the concept of “engendering” indicators; and

have some experience with developing “engendered” indicators.

|time: 3 hours]

•

•

Hand-out 1: “Definitions of some maternal health indicators”

Hand-out 2: Instruction for group work on “engendering” reproductive health

indicators

PowerPoint presentation on “engendering” indicators

Indicators to monitor maternal health goals: report of a technical working group, Geneva,

8-12 November 1993. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1997

1 hete ate thtee activities. 1 he first is a brief discussion in the large group to identify

definitions of some commonly used maternal health indicators. The second activity is

an input session by the facilitator. The third is a group activity to evolve “engendered”

indicators to monitor some reproductive health programmes.

[time: 45 minutes]

Step 1: What is a health indicator?

[time: 15 minutes]

Begin by defining what health indicators are, and give some examples. A health indicator is

usually a numerical measure that provides information about a complex situation or event.

\Xlien you want to know about a situation or event and cannot study each of the many

factors that contribute to it, you use an indicator that best summarizes the situation. For

example, to understand the general health status of infants in a country,

country, the

the key

key indicators

indicators

are infant mortality rates and the proportion of infants of low birth weight.

Ask participants to tell you the difference between rates and ratios, and explain these

conccpis if ncccssarv.

’6

““------------- itr - J

UHNIJIIH ANO NIUHTtf IN IWHOOUOTIVfl AND MAT.ANAL HEALTHi Manual for a Loarnln0 Work8hop

I

I

I

An indicator is a rate or proportion when the numerator is included in (he population

defined by the denominator.2 For example, the literacy rate in a population has literate

persons in the numerator and total population in the denominator.

An indicator is a ratio when it is an expression of a relationship between a numerator and a

denominator in which the two are usually two separate and distinct quantities.3 For example,

the population sex ratio has as numerator the number of males in the population, and in the

denominator the number of females in the population.

Elicit from participants the definitions of some commonly used maternal health indicators.

You may choose so'me from Hand-out 1.

I

[time: 30 minutes]

I

Provide an input on the meaning of “engendered” indicators and ways in which indicators

may be developed or modified to capture the gender dimensions of maternal and

reproductive health.

[time: 2 hours 15 minutes]

I

Step 1: Group work

[time: 45 minutes]

Divide participants into four groups. Each group is given a hypothetical reproductive health

project for which they must develop indicators (Hand-out 2).

Step 2: Reporting back

[time: 1 hour 30 minutes]

One person from each group reports back to the whole group on:

•

•

•

•

•

the reproductive health project under consideration;

indicators to be used and their definitions;

the attempt made to bring gender and rights dimensions into one or more of the

indicators;

mode of collection of information on these indicators; and

how often the information will be collected (for example, census inft )rmati< >n is collected

‘once in a decade).

Each presentation should last no more than 10 minutes and may be followed by a

l()-minute discussion. Some of the indicators that may emerge from each of the groups

are outlined below.

2 LastJ.M. et al. A dictionary ofepidemiology. New } ork, Oxford University Press, 1995.

1 Ibid.

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workahop

• f -i

it

T

n■

27

K

a te

1

V

propoi l ion ol Icmale adolescents reporting condom use (this may be further relined,

for example, to specify regularity of condom use, .access to condoms, or whether a

condom was used in their most recent sexual encounter);

15-1 y-year-olds as a proportion of all abortion-related obstetric and gynaecology

admissions; and

proportion of women in the 15-19 age group who have had one or more children or

are currently pregnant.

•

percentage distribution of maternal deaths by place of death;

proportion of women who died at home or on their way to’ the hospital because the

hospital” was too far away;

•

percentage distribution of maternal deaths in hospital, by time between admission and

death; and

proportion of women reporting a delivery complication who delivered in a health

facility.

•

percentage distribution of all women using contraceptives, by method used;

proportion of women and men ireporting that they were given adequate information

on the various contraceptive options available;

proportion of contraceptive users who are men;

proportion of contraceptive users reporting at least one follow-up contact with the

health facility or health worker; and

proportion of satisfied users at the end of X months following acceptance.

proportion of clinic users who are aware of the symptoms of one or more RTIs/

STIs;

f

number (and/or proportion) of clients seeking treatment for RTI/STI;

•

proportion of clients (by sex) whose partners have also sought treatmentproportion of those diagnosed with an RTI/STI who completed treatment (reasons

for not completing treatment: cost? access? quality?); and

proportion of those who completed treatment who are cured of the problem. '

i

I

I

Which of the indicators addressed above had the potential to address the gender/rights

dimensions of the issue? For example, in the Adolescent Reproductive Health project

"Hormauon on condom use should be collected from both girls and boys. In addition to’

finding out the proportion of girls aged 15-19 who are currently pregnant or have had a

I..Id, the proportton of boys aged 15-19 who have either fathered a child or arc responsible

lor a current pregnancy could also be an indicator. This information may be collected by

I

rccofosHn'lW Id

CUrrCntIy P'68”3" ab°Ut

agE °f

father' Antenatal

rccotds tn health centres could routinely collect data on the age of the father.

In the Safe Motherhood project, a gender/rights dimension may be added to the indicator

.Ik dtstrtbutton of maternal deaths in hospital by time duration between admission and

28

I

r

I

death This can be done by asking about reasons for delay. Similarly, reasons for non-use

o a health facility by women reporting a deliver}' complication would give insights into

whether gender-based discrimination, through the lack of access to resources and power or

through roles and norms, played a role in this delay.

To add a gender dimension to indicators for the Family-Planning and RTI/STI programmes

indicators should be analysed by the sex of the respondent. Finding out reasons for nonuse of any contraceptive method, or non-use of health services for RTI/STI from both

women and men could also help bring out the role of gender in this.

I

J.

I

Adapted from Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproductive health. Module 4, Session 6 Geneva, WHO,

2001.

0

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

-r

ip w w w w

—

w

4 4

J

32-

•J

«

K

29

‘f

Participants will:

•

•

become familiar with observing and analysing various elements of a health facility with

a gender and rights lens; and

understand what elements are needed to make a health facility address gender and

rights concerns.

[time: 4 hours 30 minutes]

Hand-out: "Guidelines for observation during visit to health facility"

Tliis session consists of two parts. The first activity is a visit to a health facility The second

is a whole-group discussion and a detailed summary by the facilitator.

|time: 3 hours|

Step 1: Preparation

Before the session begins, give participants instructions as described in Step 2. If available,

distribute brochures about the health facility and the services offered so that participants

begin to familiarize themselves with the services offered by the clinic.

Step 2: Instructions for the activity

[time: 10 minutes]

Divide participants into four groups and distribute the hand-out. The hand-out will give

clear instructions on what to observe and how to present the information when reporting

back.

Explain that each group will visit one specific health facility. The group’s task consists

of observing, and when needed, interacting with clients/patients and health providers to

gal her details about the quality of health services, and the extent to which gender and rights

issues have been taken into account when planning for the delivery of health services. In

particular, rhev must observe the following elements of quality of care:

30

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual lor a Learning Workshop

- ------------

kA

-------------- -----------------------w>

1*1 IM

‘

V'

VI Ht! H

----- ..... .

.

" ■

I,

client—provider interaction;

information/counselling for client; and

essential supplies, equipment and medication needed, plus norms and standards.

•

Tell them they have approximately two-and-a-half hours for the visit and then they must

write up a group report for presentation to the class the next morning [30 minutes].

I

Step 3: Reporting back and discussion

[time: 1 hour 30 minutcs|

The reporting-back session takes place on the same afternoon as the visit. I -ach group in turn

has approximately 10 minutes to present its findings. The presentation should highlight:

a general description of what the group observed about the health facility and its internal

and external environment, staff presence, workload, and so on;

what was present and what was missing in terms of quality-of-care elements listed below;

and

what needs to be done to make the clinic and the health facility address gender and rights

concerns.

•

I

•

After each presentation, make sure you allocate sufficient time for discussing gender

and rights issues.

What are the gender- and rights-relared aspects you identified in the service/clinic you

•

visited?

•

•

•

•

How do gender and rights impact on the internal and external environment, staff

presence, workload, and so on? For instance, are there separate toilets for men and

women? Are there any separate rooms for consultation and counselling? Are the

women accompanied by their husbands? If yes, does this mean there is gender equality?

In terms of service providers, are there more female than male workers? If yes, whv?

What does this show? Usually reproductive health (RH) services are dominated by

female workers. Could this also influence men’s access to these services?

It is also important to raise issues related to rights, such as privacy and confidentiality

and whether these are maintained during the consultation. If the consultations take

place in separate rooms, we may assume there is privacy, but what if the personal

medical dossiers are not kept locked and anyone who walks in can easily read them?

Another issue is informed consent and whether people arc informed about the health

examination or the treatment they may undergo. This is also linked to a person's right to

information and self-determination. People should obtain sufficient information about

the medical examination they are undergoing or a treatment they may have to follow in

order to make an informed choice. Information, education and communication (IEC)

materials in the waiting rooms and consultation rooms can also help raise people's

knowledge and information about specific health issues.

Time may also be a constraint for people to access services. For instance, different

opening times for specific services may be an extra burden for women who may have

to come back several times to the clinic to obtain different services.

9 -~

5

r i -

5

*“•-

Uk- ' -J

V •

/

GENDER AND RIGHTS IN REPRODUCTIVE AND MATERNAL HEALTH: Manual for a Learning Workshop

«■

a 4

3- m

w

5

I

’ •

—

31

£ )'

o S

£■

TVv \SO.

i. U J

vi5

2?

O

J <

It is important to highlight that gender and rights aspects are not obstacles, but that they

help improve (he quality ol health services. Summarize some of (he main gender and