National Meeting to Discuss The Draft Code of Ethics For Research in Social Sciences And Social Science Research in Health

Item

- Title

-

National Meeting to Discuss

The Draft Code of Ethics

For Research in Social Sciences

And Social Science Research in Health - extracted text

-

0

National Meeting to Discuss

The Draft Code of Ethics

For Research in Social Sciences

And Social Science Research in Health

May 29-30, 2000

At the YMCA, Near Maratha Mandir Cinema, Mumbai Central, Mumbai

Organised by CEHAT, Mumbai

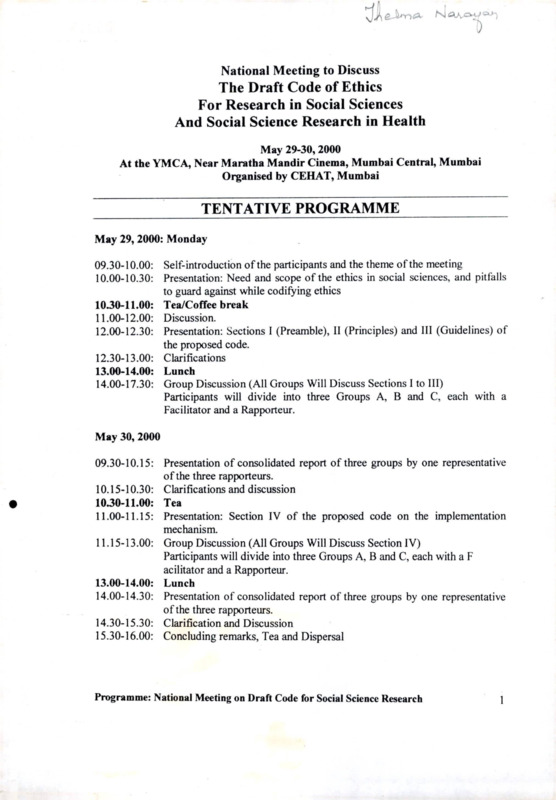

TENTATIVE PROGRAMME

May 29, 2000: Monday

09.30-10.00: Self-introduction of the participants and the theme of the meeting

10.00-10.30: Presentation: Need and scope of the ethics in social sciences, and pitfalls

to guard against while codifying ethics

1030-11.00: Tea/Coffee break

11.00-12.00: Discussion.

12.00-12.30: Presentation: Sections I (Preamble), II (Principles) and III (Guidelines) of

the proposed code.

12.30-13.00: Clarifications

13.00-14.00: Lunch

14.00-17.30: Group Discussion (All Groups Will Discuss Sections I to III)

Participants will divide into three Groups A, B and C, each with a

Facilitator and a Rapporteur.

May 30, 2000

09.30-10.15: Presentation of consolidated report of three groups by one representative

of the three rapporteurs.

10.15- 10.30: Clarifications and discussion

1030-11.00: Tea

11.00-11.15: Presentation: Section IV of the proposed code on the implementation

mechanism.

11.15- 13.00: Group Discussion (All Groups Will Discuss Section IV)

Participants will divide into three Groups A, B and C, each with a F

acilitator and a Rapporteur.

13.00-14.00: Lunch

14.00-14.30: Presentation of consolidated report of three groups by one representative

of the three rapporteurs.

14.30- 15.30: Clarification and Discussion

15.30- 16.00: Concluding remarks, Tea and Dispersal

Programme: National Meeting on Draft Code for Social Science Research

1

NOTE ON THE PROGRAMME

The programme given above is tentative, so it might undergo some change. In case you

have any suggestion, please do let us know the latest by May 25. The meeting will end

the latest by 4 (four) in the afternoon on May 30, 2000. For those who have requested

accommodation are booked at the YMCA International House.

Feedback

We made active efforts to collect feedback on the proposed draft code from researchers

and institutions across the country. The process followed by us and the comments

received are summarised in a feedback paper. Some of the presentation would cover the

feedback, and the participants are requested to address to the issues raised therein.

Session plan

The feedback contributed substantially in planning the discussion sessions of the

programme. Accordingly, the discussion would cover the following three major areas:

(a) The Need and Scope of the Ethical Code, and Pitfalls in Codifying Ethics in

Social Science Research: Many researchers have genuine concerns, and we must

collectively address to them. This process is intended for the good of social sciences

and research, and so we must collectively endeavour to convert good intentions into

appropriate code and its implementation mechanism.

(b) The Body of the Code: Sections I (Preamble), II (Principles) and III (Guidelines),

collectively constitute the body of the code. Each formulation needs to be examined

in detail by the community of researchers. We have therefore allotted maximum time

for discussion on this aspect.

(c) The Implementation Mechanism: From the feedback received so far it seems that

this issue would need detailed discussion and resolution of some of the dilemmas.

Indeed, it will have direct connection to the issues of scope and pitfalls discussed in

the first session.

Background Papers

We commissioned seven background papers for the meeting. They document some of the

issues and experiences in various fields, and some of them also elaborate the points

covered in the draft codes. We hope that participants would find them of use for

examining and analysing the guidelines.

Since the background papers are not commissioned for discussing the specific views of

the author, they will NOT be presented. However, during the group discussions the

authors will be available to the participants as resource persons.

Programme: National Meeting on Draft Code for Social Science Research

2

Some Relevant Code of Ethics

Although we have collected several codes of ethics (over 1000 pages) of different

disciplines and countries, it is not possible to provide a copy to all participants. Of course

we would keep a copy of all at the meeting for your ready reference.

In this collection we have given two sociological codes and one code on collaborative

research for your information.

Outcome

We know that adoption of a consensus code by the vast, dispersed and diverse social

science research community in India, is a process. The CEHAT and the drafting

committee are strongly committed to the gradual evolution of the most suitable code of

ethics for social sciences, its voluntary acceptance by the social science community and

its democratic implementation in a decentralised manner.

The CEHAT will be publishing the proceedings of the meeting and the code revised by

the committee based on the discussion we all will have at the meeting.

Programme: National Meeting on Draft Code for Social Science Research

3

Summary of Feedback Received on

The Proposed Draft Code of Ethics

Prepared by

The Secretariat of the Drafting Committee

National Meeting to Discuss

The Draft Code of Ethics

For Research in Social Sciences

And Social Science Research in Health

May 29-30, 2000

YMCA, Mumbai Central

Mumbai

Organised by

CEHAT

(Research Centre of Anusandhan Trust)

2nd Floor, BMC Bldg., 135 Military Road

Next to Lok Darshan, Marol, Andheri East

Mumbai 400 059. India

Tel: (91 )(22) 851 9420, Fax: (91 )(22) 850 5255

Email: cehat@vsnl.com

Summary of Feedback

Background:

The research for the drafting of the code was very daunting. We collected nearly thousand

pages of similar social sciences, psychology, medical and other research codes from different

parts of the world, and more material still keeps coming. Ten members of the drafting

committee and two members of the research secretariat at the CEHAT met twice to discuss

the drafts of the guidelines. The research secretariat was in contact with the members of the

committee between the meetings. The second meeting of the committee examined each line

of the draft and made numerous general and specific suggestions for modification and

redrafting of the code. This meeting also decided that all possible efforts would be made to

invite feedback and suggestions from the social science research community - individuals as

well as institutions. Accordingly, in addition to those invited for the May 29-30 meeting,

many more were sent the draft. Besides, as per the recommendation of the committee efforts

were also made to organise meetings for the presentation of the draft to researchers, teachers,

and students in six institutions (three from Mumbai, and three from outside) and one person

from the research secretariat had direct interaction with them.

Above all, since the recommendations made by the second meeting of the committee

demanded very rigorous effort in redrafting, the committee had recognised that there would

not be adequate time for the members to reflect on and respond to the new draft. The

secretariat was thus instructed to circulate the proposed draft for discussion without

discussion within the committee. So this paper also contains feedback from some of the

committee members. Indeed, this situation also brings all participants on the equal plane for

discussing and learning about the researchers ethical responsibilities and rights, and for

making suggestions for appropriate modifications in the draft code. Needless to add, the

members of the committee would take all suggestions into consideration before finalising the

code within two months after the meeting.

21 out of 100 odd individuals who were sent the draft, responded. Of them, six did not offer

any substantial comments except for commending the efforts being made. So this paper

summarises responses from 15 individuals hailing from institutions (including NGOs) across

the country. The meetings organised at the six institutes were fairly well attended. Over 80

teachers, researchers and students listened to the detailed presentation of the draft made by

one researcher of the secretariat and participated in the discussion that followed. Most of the

meetings lasted for more than two hours. In each meeting one person took detailed notes of

the discussion. This paper also contains summary of comments received in these meetings.

Although it was not possible to cover every thing, we have tried to summarise and classify as

many comments as possible without making too many changes in the way they were

conveyed to us. However, you would bear with us in case inadvertently we have missed out

or misrepresented any comment. (The emphasis in italic, through out this paper, are added.)

Summary of Feedback

1

Please note that each paragraph is a separate comment received on the draft of the code

and the wording of each comment has been edited Therefore, under each section and sub

section there may be totally opposite and conflicting paragraphs of comments. Such cases

only show the differences existing among those who responded

SUGGESTIONS FOR MAKING ADDITIONS

Add glossary and explain terms such as non-maleficence, beneficence, autonomy, justice,

risk, non-exploitation, and so on.

Formulate and add guidelines on the relationship between researchers and their

organizations. They should also cover the complexities involved and the issues related to

ownership of data. Same way, we need guidelines for the relationship between institutions.

What happens when there is conflict between collaborating institutions? Who own the data,

or how do they share them?

Formulate and add guidelines on collaborative and action research.

Guidelines on the responsibility and accountability of the junior members of the research

team and students may be added.

The guidelines should also address the ethical issues involved in advocacy, using results of

the research in social sciences and health.

The guidelines should provide for sanctions/punishment for their violation. There is also a

need to formulate procedure for the probe into allegations of violation or approaches that

need to be taken if the code is violated.

GENERAL COMMENTS

Timing:

It is too early to formalise and finalise the guidelines. We should wait for more time.

Social science different from other sciences:

What is the demarcation between medical research and health research? Do we mean to

include clinical research in health research? This part needs clarification.

The document suffers from two deficiencies. At one level it is too general, and yet at another

level it seems to be influenced by the experiences in health research.

The idea of a discussion on the question of ethics in social science research is necessary.

However, before one draws; guidelines for social science research it is important to

understand the nature of social science and distinction between social sciences and other

sciences, like physical sciences, medicine and even health. The fact that social sciences deal

specifically with human beings as subjects imparts certain uniqueness to this field. There is

qualitative dimension, which cannot be ignored. While medical and health research also deals

Summary of Feedback

2

with human beings as subjects, there is a distinct difference since it is easier to draft

guidelines and codes of conduct in medical and health research. What imparts uniqueness to

the social sciences is that it is not value free and ideology plays an important role. It would

seem that this distinction has not got sufficient attention in this document.

The same principles cannot be applied to social science research and health research. It is

difficult to formulate detailed guidelines in social science research, and much has to be left to

the specific perspective and orientation of the researcher and the nature of the particular piece

of research. But this does not, of course, mean that there is no room for a discussion of ethical

questions. However, these have to be evolved in the context of specific disciplines keeping in

mind the fact that there is no such thing as a value free social science.

Hindrance to good research

Guidelines and Ethics Committee though essential, they should be such as not hindering good

research.

Power dynamics

This draft takes cognisance of the inherent power dynamics that govern relationships between

the students and faculty, the researchers and funders, the senior and junior members of a

research team and attempts to address the issues that may arise as a consequence of this.

It was strongly felt that ethics and ethical guidelines on their own cannot solve issues where

the researchers are mere small entities in a world of power and money. Ethics without

considering the role-played by power and money (essentiallyforeign agencies) may simply be

futile. These issues should be addressed. The autonomy of the researchers needs to be made

strong against conflictingforces.

Comprehensiveness:

The guidelines could be made less comprehensive. It should have an introduction giving all

relevant details followed by the guidelines.

In an effort to be comprehensive some issues about appropriate and rigorous methodology

and competent research management have been brought under the purview of ethics. For

instance, asking students or assistants to perform at a level beyond their training might also

be considered bad management, bad supervision or poor training, rather than primarily an

ethical issue. Though such issues have ethical implications, by bringing such issues in the

guidelines the focus on ethics might be diluted.

Cultural sensitivity and specificity

While ethical principles are universal, the procedures for application should be culture and

situation specific. Mechanisms for protecting participant’s rights such as consent forms are

developed in the UK or U.S.A, and are used in Indian field situations with disastrous

consequences, often defeating the purpose they were devised for;

As newer public health challenges emerge within the Indian context such as the HIV/AIDS

epidemic, there is a much greater need for debate and discussion on the ethical considerations

related to research in this area.

Summary of Feedback

3

Operationalising terms and phrases:

It is true that at some level all ethical principles are abstract and it may not be possible to

clearly operationalise them However, it may be useful to operationalise terms or phrases

such as 'existing knowledge', 'risk minimisation', 'adequate knowledge’, 'dignity', 'excessive

amounts of time' and so on.

Language and editing

Use term institute instead of agency. There are many such changes needed. Besides, these are

rules/guidelines, the terms specifying to what the operating parts are related to may be added

(e.g. adding terms as thereto, therein, etc.). There are some repetitions, which need to be

edited out.

Wider recognition and acceptance of code needed

Efforts must be made to get this code accepted by the funding agencies, journals, etc. This

code should also be accepted and respected by the international organisations andjournals.

SEPCIFIC COMMENTS ON

DIFFERENT SECTIONS OF THE GUIDELINES

SECTION I: Preamble

General:

The preamble needs to be made stronger, raise ethical issues and be more critical, and give

details in terms of the background. Moreover, the exclusion of medical research needs to be *

clearly spelt out. It should be more positive.

Purpose of the code maybe defined as:

(1) To improve quality, legitimacy and credibility of social science research. (2) To protect

researchers from pulls and pressures of vested interests and dominant social forces. (3) To

make research socially relevant so as to benefit a larger section of the society and to upheld —

human rights of the participants. (4) To evolve consensus for a need of ethical values among

social science researchers for guiding their research so as to maintain autonomy of social

science research.

SECTION II: Ethical Principles of Research

Provide definition of various terms such as “autonomy”, beneficence”, etc. and it would be

good to expand the first paragraph by giving some more information on what each of the five

normative principles actually mean.

Is there a prioritisation or hierarchy of principles? What to do when two principles are in

conflict with each other in a particular instance or on a particular issue?

II. 1 Essentiality

It is easy to state but practically difficult to achieve the requirement that the research should

be undertaken after giving adequate consideration to existing knowledge because it is still so

Summary of Feedback

4

difficult to access much of the available research. Access through Internet is limited to a few

journals particularly from developing countries. Lots of research from our country does not

get published due to the bias towards positive findings and lack of sufficient number of good

social science journals. Is the unpublished research covered under “existing knowledge”?

IL2. Precaution and risk minimisation

How much 'risk' in a research project is 'risky'? Whether and how to quantify this? More

importantly, if risk is involved, what ’safety nets' must be in place to manage the risk?

Perhaps every research study should have ways and means of anticipating and assessing risk

and also managing risk. What is acceptable risk, and what risks are definitely not acceptable?

What would be minimum risk and what would be maximum risk? Some of these may be spelt

out and shared with the participants of each research study. In some way this code may

specify risk in more concrete terms. Moreover, it is not necessary that all studies carry some

amount of risk.

11*3. Knowledge, ability and commitment to do research:

Some people argue that a badly done research is unethical. Is this code taking such position?

Who will decide the knowledge, ability and commitment of researchers?

The fist part of the statement “While research

as professionals” may be deleted.

Should research be done only within a researcher’s field of expertise?

II.6. Non-exploitation

Most research these days, is funded. So budgetary provision should be made for the payment

of some nominal fee to the participants. This is a regular practise in ethnographic work. The

idea being that, if knowledge is coming out of communities, then those communities have a

bigger right to the benefits and commerce of the knowledge than anyone else. What are the

criteria for compensating the respondent for “loss of income” if he/she is not gainfully

employed?

IL7. Accountability and Transparency

The code should define “reasonable length of time” (say range of three to five years) for

preserving research record.

The “public domain” should be clarified. It should not include the state/govemment

perception of “public domain”. The responsibility of adequate efforts to make the results of

the research public should be a part of the principle of totality of responsibility.

The effort to be transparent should not mean revealing the names of the participants.

How does one ensure public accountability? Clarity is essential for issues such as public

scrutiny and public audit.

The researchers are sometime forced to go ahead with studies they do not agree with. In such

situations, what can the researchers do as they need funds?

Summary of Feedback

5

IL9: Public domain

Is it realistic to bring out all research to the public domain? What about papers which are just

not good enough? Are they not rejected by journals during peer review? It might be good for

bad papers not to get into public domain and get quoted/used by others. The word “all”

should be reconsidered.

Why is it necessary to publish research? What was wrong in not publishing it?

II. 10. Totality of Responsibility

The paragraph mentions ‘products’, which are marketed. Are we talking about commercial

research? If yes, doesn't this take the discussion to a different plane altogether? Shouldn't the

document also then discuss the ethics regulating the commerce in health care work - profit,

charging fee, packaging and advertising, marketing, 'telesales' etc.?

SECTION III: Ethical Guidelines

IIL1. Integrity of Researcher

III.l.l

The studies done in one country could have implications in another country. Therefore, the

implications thus mentioned need to be left broad, or the second sentence may be expanded to

even an entire state, country or the world”.

III. 1.2

It will be good to have some rules regarding use of information in the NGOs. The whole area

of 'parallel publishing' which doesn't come under the purview of copyright is very sticky.

When issues such as the above are raised, such as misrepresentation, etc. it ends up being a

personal issue between two contesting individuals, both of whose integrity is eventually

compromised, and leaving behind rancour and bitterness. The issue of copyright and

ownership of data too need to be discussed.

III.1.2.

Expecting researchers to anticipate and guard against possible misuse and undesirable or

harmful consequences of research sounds very unrealistic. How can researchers actually

prevent people from doing what they want with the published papers? How will researchers

even know what is being done with their research all over the world?

IIL13.

This principle can be over-run by the state, especially when the research is undertaken by

public institutions or uses public funding. The state or its organisations (e.g. ICMR, ICSSR,

etc.) can, sometimes, legally usurp this principle, by claiming to act as the custodian of the

well being of its people.

There may be instances where research results need to be kept confidential. For instance

where the results may lead to harm to participants.

Summary of Feedback

6

The words fckto be kept confidential” may be replaced with 4twhen its findings are not shared

with the scientific community and participants of the research for scrutiny, discussion and

interpretation.”

in.i.4.

Split this guideline into two separate guidelines. Sensitivity is a very broad term. How does

one define it?

ni.i.6.

The last sentence should read,"

any other such practices”, instead of "other practices”.

in.i.7.

Instead of "historical" the word "old” will be more appropriate since only records of 100

years old can only be called as historical.

Researchers not only have the dutyjp protect historical records but to protect all records.

III.2. Relationship between Researcher

And Junior Researchers/Students/Trainees

in.2.6.

This guideline needs substantial change. One should not avoid usage of an available resource.

Suggestion: “A community may identified for long term interventions, provided the issue is

decided between the community and the researchers in a manner that is mutually beneficial,

and provided students are the owners of their own research.”

This guideline against using a community for constant and long-term resource should also be

made applicable to all researchers and institutions and not to just research by students.

Others

Details about ownership of data cannot always be laid down at the outset since it would

depend on the inputs of the student or junior.

What can be done if their seniors get scholarship in other countries on the basis of papers

done by students/junior?

Those junior researchers who are not in agreement with the philosophy and principles of a

certain research approach must desistfrom joining the research team right at the onset.

Students should be made to stretch their abilities to cover aspects of research such as

conceptualisation, formulation of innovative approaches, original analysis, and delegation of

work to them should not be merely task oriented.

The guideline sounds like allegations on researchers! A guideline on mutual respect needs to

be added.

Summary of Feedback

7

IIL3.Relationship between Researchers and Participants

HL 3.2.

Instead of saying 'should not' can we be positive and say what can be done.

This is very general and may be further specified. What is the bottom-line for 'harm' physical and mental?

Research should not be undertaken unless some actual anticipated benefit accrues.

Sometimes research may harm the dominant sections of society exposing their power and

manipulation. Such research may affect their physical, social, psychological well being,

though it helps the larger society. What is to be done?

When a researcher undertakes a study on certain critical issues, e.g. gender, the researcher

inevitably influences the participants. Would the implications of this be in consonance with

this guideline?

IIL3.4.

Add word ’’thereof (after ‘"reason”) at the end of the last sentence.

III3.5.

How does one decide what are ‘"unrealistic benefits”? What should be a reasonable benefit^

How does one compensate', actual compensation of the time, a certain percentage more than

the actual opportunity cost? What should one give to unemployed people? Anything given to

them would be excessive.

What is meant by excessive reimbursement? How much is excessive?

Are we accepting the concept of reimbursement? It may influence the participants to give you

what you want.

There indeed is a dilemma about not giving anything in return to the participant when he/she

has spent 2-3 hours in interview. The foreigners introduced the idea of reimbursement/

compensation and now respondents demand that from us.

IIL4. Rights of Participants: Informed Consent

ni. 4.2.

Add the following:

""The briefing given to the participant should be such that the participant comprehends that:

(i) She/he is participating in a study, (ii) She/he has a right to refuse to participate, (iii) She/he

will not be denied access to any services/information if she/he refuses to participate in the

research study.”

Summary of Feedback

8

There is a need to devise simple and culturally appropriate consent procedures to protect the

rights of participants. The key issue here is the participants’ understanding of the consent

process.

If, after an evaluation, one found that members of the community participating in a research

did not know the objectives of the research, would it be ethical to terminate such a project

after an evaluation?

IIL4.4.

What does one do when funding agencies make it essential for researches to get 2-3 pages

long informed consent signed by the participant?

Some medical researchers strongly expressed their disagreement on the idea of not taking

written informed consent from the participants for the social science research in health.

Sometimes the funding agencies demand a proof of the fact that consent was taken in terms

of signed consent forms.

Should the participants be given a right to withdraw at any stage of the research, as such right

has the potential to jeopardise the entire research endeavour?

There may be problems in respecting participant’s right to get help. All researchers and

institutions may not have capacity and resources to provide for such help. What is the level

up to which the researchers and institutions should provide help?

in.4.6.

What length of time for interview or data collection from the participant is excessive?

IIL4.10.

Are children defined here as legal minors (under 18 years of age)?

How can one try to get consent of child who is too small? Maybe a cut-off year for those

children for their own consent is not needed could be specified.

Others:

For a longitudinal study, a community board with members from the participant group should

be set-up.

Research findings should be shared with the participants in a simple way (summary of

findings, in the language they understand). In the briefing given to participants for getting

informed consent, the promise to bring summary of findings to them may included.

IIL5. Rights of Participants: Privacy, Anonymity and Confidentiality

III.53.

Is it really possible to devise “appropriate methods to ensure privacy at the time of data

collection” in the kind of situation prevailing in Indian household and villages? People often

have different conception of privacy.

Summary of Feedback

9

IIL6. Data sharing and Secondary Use of Data

Restudy at different points of time to see the changes; or restudy with different purpose or

method of the same population is important to maintain checks on researchers arbitrariness

and sole propriety. Sharing of data is then important. If the data/notes are not shared for

scientific / study purpose, there is no mechanism left for verification and cross checking.

III.7. Reporting and Publication of Research

in.7.1.

There is a reference to plagiarism. It is important to list, to the extent possible, all things that

can be treated as plagiarism to facilitate understanding. Moreover, plagiarism is linked

formally to issues of copyright and its violation. However through the rest of the document

there has been no mention of copyright or about 'ownership' of information. In fact in many

of the activist circles there is a closely upheld view that knowledge is for everybody and we

don't respect proprietorship over ideas. What then constitutes 'plagiarism'? What constitutes

correct use of information and how to strike an ethical balance about use and abuse of

information without falling into the trap of saying that only copyright laws can regulate.

in.7.3.

Authorship credit based only on contribution towards writing may be unfair to those who

might have played extensive role in conceptualisation, analysis and interpretation. It should

be recognised that conceptualisation, formulation of innovative approaches, original analysis

and interpretation also constitute substantial contribution.

Many NGOs/institutions are involved in intervention/action research. In such research, the

authorship credit should also be given to key individuals who have participated at the

programmatic level in operationalising the intervention, but may or may not have directly

participated in writing or analysis.

in.7.4.

The research results conveyed may be truthful and honest, but the media could still

sensationalise them. What to do in such situation.

Others

Sometimes similar articles by the same author(s) are found in 2-3 journals.

The abstracts of studies should mention clearly the scale of the study. The content of paper

should match its title.

III.8. Role of Editors

Why should the guidelines for social science research include guidelines on the role of

editors?

The document vests the editors with tremendous and almost final responsibility in ensuring

the ethical norms adhered to.

Guidelines given here are too general^ they should be made specific.

Summary of Feedback

10

III.9. Role of Peer Reviewers/Referees

The document vests tremendous and almost final responsibility to peer reviewers and

journalists in ensuring adherence to the ethical norms.

Add guidelines laying down the qualifications required of those individuals who undertake

the peer review or act as referees. At least it should be stated that they should have sufficient

kno^dge of the issue of research to be reviewed. Or the researcher should accept to be peer

reviewer or referee for only those issues/topics of research for which he or she has sufficient

knowledge.

ni.93.

It may not always be possible to know about a potential or an actual conflict of interest at the

start of the review.

While the editors and peer reviewers should bring to the public notice the unethical research

malpractice and fraud, they should also ensure complete anonymity to those who provide sue

information to them (whistle blowers). This would not only protect team/institution members,

but would also encourage more people to come forward with information.

IILIO. Relationship with Sponsors and Funders

What to do when funders/sponsors lay down restrictions on publication of data or demand

that their permission must be sought? Often institutions sign an MOU with the

funders/sponsors to keep results confidential. Researchers need resources for their work, how

could the resist the pressure from funders and sponsors all the time? Would bringing research

results under the right to information legislation help to overcome such situations.

Summary of Feedback

11

Section IV: Institutional Mechanism for Ethics

[Many conflicting comments have come on this section, expressing scepticism to regulatory

implementation as well as making strong case for rigorous regulations. Some comments

suggest that the implementation of code should be left to the conscience of researchers. Some

would like to think and discuss more about the institution based ethics committee before

saying anything on implementation mechanism. Some have demanded central or national

ethics committee appointed by some authority or associations of social scientists or of social

science institutions. Some have stated that the “self-regulation ” might not work or hasn’t

worked (otherwise why the need for this code?) in our condition, so it is necessary to have

structures with definite powers to implement the code. It is also argued that if this code would

be followed by only those who have already been doing so (the ethical, the converted), then

what is the point in so much effort being made. It must have utility in regulating those who

are not ethical enough, and hence the needfor some universal implementation mechanism.]

IV.l.

If the purpose of the draft is to set the code of conduct for social science research and leave it

up to the individual researchers to self-impose them, the draft is fine. The draft, however,

outlines the role of the institution to enforce the code. In this connection, the issues discussed

are intricate and need a lot of thought.

Specifically the question of an Ethical Review Board/Ethics Committee (ERB/EC) brings up

the question of values and ideology in social sciences, and indeed the question of academic

freedom. The very idea of an ERB/EC in today’s context in India (and the world) seems

rather disturbing. In a situation where the very principles of academic freedom are being

eroded either by dominant and hegemonic groups or by the more impersonal but nonetheless

real forces of market, one has to be even more cautious when suggesting an ERB/EC. One is

not even going into the implementation of it and whether such an ERB/EC would in practice

be able to rise above the fray and be “impartial” is altogether another matter. Given that; the

agendas of social science and health and medical research are being increasingly set by

funding agencies and corporations, one wonders whether these ERBs/ECs will indeed be able

to interrogate the agendas of funders. Here we need to keep in mind our experiences about

professional bodies. National bodies like the ICMR, ICSSR, ICHR, etc. were set up with the

idea of protecting the autonomy of the profession and that of the researchers. However, their

autonomy has been seriously eroded over the last few decades and today, those bodies are a

pale shadow of what they were.

The 'voluntarism' underlies the document. This must be debated carefully so that the whole

terrain is laid out before the group. After all, the need to spell out the code has been because

there is the perception that voluntarism hasn't worked.

Some institutions might endorse the guidelines (and might network among themselves), but

many others might not. Besides, the commercial market research organisations are unlikely to

endorse the guidelines. It is possible that those not endorsing are doing lots of research and

lot of that is unethical. What could we do about that? For the code to be effective, all

Summary of Feedback

12

organisations and individuals doing any kind of social science or health research in this

country must implement the guidelines.

This code should be sent out to organisations doing lots of research but not making it public.

The results of all studies done should be brought under the right to information.

A central or national committee, appointed by a social science association or by social

science institutes, may be formed.

Localised body is more suited to our country due to diversity of culture and complexities of

problems.

IV.2.

What role would the ERB/EC play- educative, consultative or regulatory?

If there is a central authority created, then its role should be educational and consultative.

The institution should have administrative control over the ERB/EC, as without that the

recommendations of the committee may not be implemented.

Although the institution appoints the ERB/EC, it should be free from its administrative

control.

ERB/EC should have members from within the organization as well as outside. A layperson

' from the study population as well as a person from the legal community should be on the

committee.

IV.3.

The word “all” should be reconsidered. What about retrospective research based on records,

etc? Should they go to the Ethical Review Board (ERB) or Ethics Committee (EC)? If

everything came up for ERB/EC review, this would lead to a lot of delay in a busy research

institute or hospital.

At what stage or stages of research should the ERB/EC undertake a review? Would not

undertaking a review at all stages of research end up in the project bearing the time cost?

Should not the committee be given the maximum time within which it should complete its

review?

The ERB/EC should have power to impose sanctions/punishment on the institution and

researcher for foiling to observe ethics as given in the code.

What happens when the institution refuses to accept or implement recommendation of

ERB/EC? For instance, if the ECfelt that on ethical grounds a particular research should not

be undertaken but the organization feels that the project should be taken up?

Summary of Feedback

13

National Meeting to Discuss

The Draft Code of Ethics

For Research in Social Sciences

And Social Science Research in Health

May 29-30, 2000

YMCA, Mumbai Central, Mumbai

Organised by

CEHAT

(Research Centre of Anusandhan Trust)

2nd Floor, BMC Bldg., 135 Military Road

Next to Lok Darshan, Marol, Andheri East

Mumbai 400 059. India

Tel: (91 )(22) 851 9420, Fax: (91)(22) 850 5255

Email: cehat@vsnl.com

BACKGROUND PAPERS

1. Padma Prakash, "Ethical responsibility in social science publishing: Role

01

of editors, journalists and peer reviewers"

2. Radhika Chandiramani, Lesley Jane Berry', "Ethical issues in sexuality

13

research and intervention "

3. Neha Madhiwalla, "Ethical dilemmas in health research with women: A

32

case study of a survey and a qualitative study”

4. Madhukar Pai, "Ethics and epidemiological research: Some dilemmas and

difficulties in the Indian milieu"

42

5. Sandhya Srinivasan, "Ethics in medical research in India: An overview”

53

6. Tejal Barai, "Ethical issues in social science research: Some basic

69

concepts”

7. Lester Coutinho, "What good will come about from your research?: Some

reflections on the ethics in doing ethnographic research in health"

83

BACKGROUND PAPER: 1

Draft Not To Be Quoted

Ethical Responsibility in Social Science Publishing

Role of Editors, Journalists and Peer Reviewers

Padma Prakash

It is common sense that ethical codes of conduct cannot be effectively implemented in

isolation. No one sub discipline or even a sub-discipline can hope to either evolve or put

in place ethical guidelines for its practitioners. On the other hand, universal guidelines are

more often than not observed in the breach. For, codes of conduct may be enforced in

several different ways. One, is to conscientise the members of the profession to observe

the rules, second, is to effectively police the system, and a third is to create links with

associated disciplines or community of practitioners who together can form a network of

conscience keepers. Journals and publications play this supplementary role in ensuring

adherence to codes of ethics, even as others play a role in evolving and implementing a

code of conduct for their own profession and trade.

It is hardly necessary to point to the crucial role that publications and journals play in the

disseminating of the products of research. In so for as the process of research today is

increasingly enriched by, even dependent upon, the articulation of the findings of

research and their communication, to the rest of the academic community, to the people

at large, there can be no research without its publication .

Journals are portals through which research activity and one might say by extension, the

research community finds a voice. The primary and major responsibility for ensuring that

ethical norms are followed in the social science research, lies with the researcher/s. All

others who are touched by the research and are involved with any stage of it- institutions,

journals, peer reviewers, editors, popular media- may play only a secondary role. Given

this, the ethical responsibilities of editors of research journals is a reflection of the level

of understanding of ethical responsibility within the research community. Having said

that, it needs to be stressed that the disseminating medium of publication of research

results plays an important supportive role. Journals and their editors can be seen to be

conscience keepers for ethical research. However, in so far as they are also members of

the press, their conduct must adhere to the codes of conduct of their profession. Journals

play an important role expanding and fine tuning ethics in research and in journalism.

Editors of academic journals are doubly accountable. There are however severe

limitations to this role. Should they for instance, be whistleblowers? Should journals

become a clearing-house for ethical misdemeanours? Given that they are the portals

through which all research must pass in order to be accredited and acknowledged, should

journals and their editors attempt to locate, separate and make complaints about and keep

track of unethical conduct?

Background Papers

1

Essentially, the role of academic journals is to nudge researchers and research institutions

towards ethical conduct. Journals cannot take on the responsibility of policing social

science research. Firstly, they neither direct nor administer research. They are players

only at the last phase of research. Secondly, their project is different—it is not the creation

of knowledge, but its dissemination. While the manner in which the knowledge

accumulation takes place is of importance, the journal's concern is with its readers, its

contributors and with the expansion of knowledge base in the discipline/s. Thirdly,

material published in a journal has to satisfy many criteria and not just in matters of

ethical conduct of research. Fourthly, insofar as they receive a wide range of research

contributions, they may be able to keep a finger on the pulse of research and its conduct

.But this role is entirely dependent on their interaction with and their significance for

researchers and research establishment. A journal of repute may be better able to play to

play this role than a new journal or that has not for one reason or other gained a large

readership in the academic community. This may be facilitated by creating a consensus

among research journals on such issues as ethics in research. [See sections of the code]

I: Norins of Publication

In India journals which are not run by professional associations are few . The latter are

bound by the codes of conduct of the association as much as by publishing ethics. To that

extent it is easier for these journals to formulate norms and procedures that ensure that

unethical social science research does not get published and disseminated. However,

independent journals need to evolve codes, which draw from several disciplines. While

these may not clash, the application of one set of 'dos and don't s' may not be advisable

for another. Papers are accepted for publication on the basis of a number of criteria,

which are different for different journals. But in all circumstances the decision rests with

the journal.

Not all journals are entirely peer-reviewed. This may be because journals may have on

their core staff, professionals from various disciplines. Or it may be because the

periodicity of these journals and the number of papers they receive is such as to make the

peer review process for all papers impossible. It could also be because, they include

sections devoted to current affairs, where peer review cannot be a norm.

The time period between the receipt of a paper in a journal and its publication varies

widely among journals and for disciplines depending on various factors including

periodicity of the journal. It may be as little as two weeks or as long as a year. It is not

widely known that the publication of an article is dependent on a number of factors: its

topicality, its shelf-life, length of the paper, subject of the paper, and so on. However, the

time between the submission of a paper and its processing is determined by fewer factors

and typically, an author gets to know the status of a paper within three months.

It is important to recognise that most academic journals are short staffed! Like a teacher

confronted with a pile of term papers, editors too resort to ways and means of making

Background Papers

2

their work faster and more interesting. One practice followed universally is that the

inarguably better presented and very evidently, better organised paper first from the lot of

papers received more or less at the same time. It is important to remember this, because

editors/peer reviewers are not infallible, nor can they play god. However codified are the

norms of ethics, there is room for slippage.

Several considerations operate when processing a paper submitted for publication.

How interesting is the topic of research? Is it of relevance—to the discipline, to society?

What purpose is it supposed to serve? Is the construct of the hypothesis mischievous,

deliberately biased? How good is the work being presented. Is it academically rigorous?

Is it scholarly? Has there been adequate literature survey? Does it academically, reinvent

the wheel? Ethical issues pop up within all these considerations. It has been said many

times that bad research is also unethical. So a paper rejected for lacking rigour may well

have not followed ethical practices. On the other hand all research that follows ethical

norms may not necessarily be found acceptable by a journal for other reasons.

Can a review process for publication spot fraudulent research? This issue has come up for

much discussion following the publication of Alan Sokal's article and his attempt to

’expose' what has been called the lack of academic rigour in social science publishing.

[See EPW issues of 1999. Website: www.epw.org.in]

II: Ethical Issues

Plagiarism

The term originates from the Latin word 'kidnap'. In the broadest sense plagiarism deals

with the lifting of text/data from a source without crediting the source. However, the

issue of plagiarism abuts on issues of copyright. Codes of several professional bodies

have very specifically dealt with plagiarism and have defined it in different ways.

A journal or a publishing house plays a crucial role in ensuring that authors do not get

undeserved credit for work that is not their own. In due process, plagiarised text is not

very difficult to identify. Normally, in any journal or publishing house, the manuscript

submitted for publication is read by a person who is in touch with the work in that field.

Even so, while plagiarised writing may be relatively easy to spot, it is far more difficult to

spot plagiarisation at the research end. Has the data been lifted from earlier documents?

Have arguments evolved and presented included in the text without acknowledgement?

These sort of details are far more difficult to spot. And with the rapid expansion of

academic activity and the number of sub disciplines it has spawned, this could be a

problem.

One way to deal with it is to send the manuscript to more than one referee, so that the

likelihood of plagiarised text coming to light is enhanced.

Background Papers

3

What is the responsibility of the journal and its editors? Other than sending the paper

back to the author, does the journal pursue the matter and make the information known

generally? Does the journal inform the author of the reasons for rejecting the paper-that

the journal has recorded that material has been lifted from other source without

acknowledgement? Does it inform the original author of the attempt to plagiarise if her

address is available? In other words, apart from ensuring that plagiarised material does

not appear in its pages, can the journal ensure that the paper does not appear anywhere ?

Should it take on this role at all?

For the present there is little the journal can do but to inform the author of the paper the

reasons for the rejection. But there is no supervisory body to which it can send a general

alert. Nor do professional associations in India have a ’clearing house’ or adjudication

process for such issues. Nor is it possible to send information to the original author

systematically or routinely. And then again, the journal has insufficient information to sit

in judgement. For instance, it could possibly emerge that the first author had in fact lifted

from the second paper, but due to a combination of circumstances, the first got published

earlier. For this there has to be a process that compares the two papers and arrives at a

decision. We do not as yet have such a process in place.

Sometimes though, especially in periodicals, which have sharp deadlines to keep,

plagiarised papers do get into print. What happens then? Usually, such a paper is spotted

within weeks of publication.

And the journal may be informed of it either by the original author or by another reader.

In such a case there would be copyright violation and the journal itself stands to be

charged with it [see below on copyright].

For the present, one can only state that if plagiarism is not as common as it could be it is

only because ethical considerations do operate at the level of research. Several

professional associations charge their members with responsibility of ensuring that they

do not plagiarise. For instance the American Psychologists Association warns its

members:

6.22 Plagiarism: Psychologists do not present substantial portions or elements oj

another's work or data as their own, even if the other work or data source is cited

occasionally

.... Psychologists take responsibility and credit including authorship credit, only

for work they have actually performed or to which they have contributed.

[... 6.24 Duplication Publication of Data: Psychologists do not publish, as

original data, data that have been previously published. This does not preclude

republishing data when they are accompanied by proper acknowledgement.

[Code of Ethics, American Psychological Association: Ethical Principles of Psychologists

and code of conduct]

The American Anthropological Association admonishes its members not to ” deceive or

knowingly misrepresent (i.e. fabricate evidence, falsify, plagiarise) , or attempt to prevent

Background Papers

4

reporting of misconduct, or obstruct the scientific/scholarly research of others."[Code of

Ethics of the American Anthropological Association, June 1998]

The American Sociological Association has this to note:

14 (a) In publications, presentations, teaching, practice and service, sociologists

explicitly identify, credit and reference the author when they take data or material

verbatim from another person's written work, whether it is published, unpublished

or electronically available.

(b) In their publications, presentations, teaching, practice and service,

sociologists provide acknowledgement and reference to the use of others' work

even if the work is not quoted verbatim or paraphrased, and they do not present

others' work as their own whether it is published, unpublished, or electronically

available. [ASA Code ofEthics]

Copyright

' t was first promulgated in 1911 and subsequently amended in

The Indian Copyright Act

1957 incorporating the requirements of the Berne Convention, which India signed in

1927. A separate treaty under UNESCO was signed by the US and the former Soviet

Union in 1952 which granted protection of only 25 years in contrast to the Berne

convention which ensured protection to the author for her lifetime plus 50 years. The

Indian act ensures protection to the author for her lifetime and 60 years after. With the

signing of TRIPS in 1994, these conventions became infructuous. Amendments in the act

in India in 1992 have been made including the right to formation of societies for

monitoring copyright violations. While plagiarism is not mentioned directly in the act, it

is covered in section 13(3). The problem is the issue of plagiarism has not come up for

open discussion in the Indian academic community. This does not mean that plagiarism

does not occur both in the mass media and in the academic media.

Today with the expansion of the media and seamless communication, it is far more

difficult to monitor such offences as plagiarism. There is an urgent need for academic

journals in India to get together on this and several other issues impinging on academic

freedoms and unfreedoms.

Simultaneous publication/submission for publication:

Several professional associations in the west have specific cautions against simultaneous

submissions. The ASA Code of Ethics for instance is the clearest in this regard and

stipulates:

16.01(b)ln submitting a manuscript to a professional journal, book series or

edited book, sociologists grant that publication first claim to publication except

where explicit policies allow multiple submissions. Sociologists do not submit a

manuscript to a second publication until after an official decision has been

received from the first publication or until the manuscript is withdrawn.

Background Papers

5

This is the norm with regard to publication in the print media in general everywhere in

the world including India. However, in India, the notion has clearly not caught on.

Sometimes, though not rarely, authors submit papers for publication to two journals,

without mentioning that information in either submission. This is a serious offence and

must be considered to be so because it can lead to simultaneous publication of the paper

leading to copyright infringement problems.

However, there is genuine confusion among academics on this matter. Is it incorrect to

submit material for publication to two publication, one a condensed version and another

the longer paper? Is it wrong to offer a paper to two publications one of which, is a small

circulation journal with possibly a specialist readership?

There can be few blanket rules here. Overall simultaneous submissions are to be avoided.

However, there could be an extraordinary reason why a paper or a part of it be submitted

for publication to two journals. It could be because the publication of the full paper may

take some time in an academic journal, while the content of the paper needs to be

available for wider dissemination immediately, either through the mass media or through

specialist journals or as a pamphlet. In all these cases, the author should inform the editor

of the circumstances and seek permission, which may be given at the discretion of the

editors in the interest of wider dissemination. Ways and means may be sought to

overcome copyright problems. But in any case it is the responsibility of the author to

inform the editors of the act of simultaneous submission.

Authorship and Publication Credit

Currently while some journals prescribe the manner in which authors names should be

presented, there appears to be no norms for ensuring, at the time of publication, if indeed

credit for work has been apportioned justly in the taxonomy of contributors in a particular

article. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (Vancouver Group) has

recommended norms for scientific authorship. But even this is not followed. There has

been much debate about this issue in the pages of scientific journals. Some years ago,

when the issue of by lines in scientific publications came up for much debate, the Lancet

conducted a review of its published contributions and found that only about half satisfied

the Vancouver Group criteria.

Ensuring that correct credit is given is important because as the Lancet pointed out during

these debates, this is an issue of accountability. It is a question of, "who stands behind the

word". Some journals in response to the anxieties of the scientific community instituted

certain norms. The British Medical Journal, The Lancet and the Annals of Internal

Medicine seek statements from the contributors on the nature of actual contribution of all

the authors listed. The BMJ also asks for a guarantor to "ensure the integrity of the

research".

Authorship has received considerable attention in several codes. Most professional

associations stipulate that credit, including authorship credit should be given to all who

have contributed (for example the ASA Code of Ethics). However, this may open to

Background Papers

6

discussion. CEHAT’s own internal code stipulates that authorship be given only to those

who have actually contributed to the writing of the paper. The proposed draft code sets

out the issue in broad terms and strikes a good balance, by including the proviso that all

those who have contributed, including those who have worked for short duration etc

should be properly acknowledged.

The Indian academic community appears unaware of these issues. Authorship norms vary

among institutions. More often than not, authors are listed on the basis of seniority in the

department rather than on the actual work done. Unless journals ask, as the Lancet does,

for details of contributions of individuals, it is impossible to right a wrong in this matter.

For example, it is well known and accepted that if a paper uses the work of a student,

then the student should be the main author. This is not universally followed. Since this is

easy enough to determine because of citations of the research work of the student, what

should journal do in these instances? Currently in the absence of such codification in

professional associations, journals have no grounds for suggesting a change in the order

of authors’ names. Ethical guidelines as are being evolved must incorporate

recommendations on this count so that it is possible for journals to ensure adequate credit

is given to researchers.

These above are patent and obvious problems for dealing, which there is sufficient

documentation and even codification. Just what procedure one adopts can only be left to

the journal. There are however a number of other issues which impinge on un-ethics, but

may well get dealt with if the academic standards sought by the publication are stringent

enough.

There are other issues with regard to indifferent research, which impinge on ethical

practices.

Ill: Lack of Rigour Affecting Ethical Conduct and Reporting

Issues with regard to data

The data base in any dissertation, especially in one which is an empirical exercise,

determines by and large the quality of the analysis.

Poor data may be a result of genuinely poor research expertise. But insofar as poor data

may give rise to misleading information and understanding, it must be regarded as a

matter of ethical consideration.

Editors/refrees cannot ignore the following:

1. Random sampling which is not in fact random and is deliberately biased

2. Either too many discrepancies within the body of data gathered or too few, matching

all the expectations of the study perfectly.

3. Use of old or obsolete data for comparisons, when later sets are available

Background Papers

7

4. Inappropriate time frames for gathering data . eg data on illness episodes draw on

only in one season used as universal data and overall conclusions drawn.

This is poor research, which is also unethical.

Informed consent

Often papers do not indicate whether or in what manner the population under study has

been informed about the study. Nor if the researchers have ensured that people concerned

donot have any objection. This is perfectly within the contours of a good paper, which

does not necessarily state that each and every ethical norm has been observed. This being

the case, while it is important to ensure that the work submitted for publication has

abided by the norms of ethical research, it is difficult to be certain that it has. The best a

journal can do is to look for associated indicators of good ethical practice, (see below).

However, papers do sometimes that the issue of obtaining consent from a population or

group under study has not even been considered. Then it is useful in the interest of ethical

research that the journal seeks information about it. Whether or not research that violates

some norms of ethical practice should be accepted for publication on the strength of its

research content, for the new understanding that it brings to bear on a certain area of

study is an issue that needs to be discussed within the community of academic journals.

IV: Check list for Editors/Refrees

In considering a paper for publication, it is not always possible as we have seen to find

out, leave alone ensure that norms of ethical practice have been respected. While a ethical

guidelines may make the task easier, researchers are not bound to submit any assurance

that the research has been conducted as per the norms of ethical practice obtaining in the

profession/department/institution. But it is often possible to look for indicators of good

practice, and editors often do. For example, papers coming from certain institution

prompt a more positive reception than others, often perhaps because the institution has a

reputation for undertaking good research. If journals have a check list which covers some

of the major considerations in ethical research, this may over a period of time encourage

research institutions to not only adopt ethical guidelines but also to codify norms and

practices for the institution with regard to the conduct of research and its presentation.

The check list is however just that--it is not a decider. A first such check list is given

below

1. Has any attempt been made to disseminate the results of the study to the study

population?

2. Has care been taken to ensure the harm 1has not accrued to the population as a result

of the research?

11 There are many definitions of'harm' in the different codes. Essentially, as far as journals are concerned

they need to ask if any immediate and visible harm done because of the study.

Background Papers

8

3. Does the institution under which research has been conducted has in place an research

ethics committee of any kind? Is it operational?

4. Are peer review processes in place in the institution. In particular, is publication

submitted for publication subject to peer review?

5. Has the paper taken adequate care to ensure that the participants in the study have not

been identified by the use of markers or other means?2

6. Have the people affected by the research understood and consented to the research?

Or, does the institution have the practice of obtaining such consent for its research?

‘ ‘ ‘ of exclusion:: as a thumb rule which gives some indication, who has been

7. ■Principle

excluded in the study? Which population group has been deliberately included? Is

there a reasonable explanation offered for this?3

8. If the research is independently done, outside institutions and is privately fimded, has

the author offered information on ethical considerations followed? Or has the funding

agency adopted codes of conduct for research?

9. Language: Does the paper use abstruse and convoluted language or jargon when the

same would have been conveyed in simpler language?4

5

10. Are there too many gaps in referencing ? Are the citations incomplete?

V: Popular Press

The paper would be incomplete withoutt some reference to the popular press. There is a

wider gap between the popular press and the academic terrain, and presents far more

issues, which need to be discussed in both communities of professionals.

Many of today's senior journalists in the press are academics who by their training and

more often than not, their years of work, are as much members of academic community

as they are professional journalists. This puts a double burden of responsibility on them.

And there are manifest tensions between the immediate objectives of the academic

community and the press. An accepted norm within natural science and technology

disciplines is that 'discoveries' and research outcomes are not revealed to the 'general'

public before they are presented to the relevant academic community either through

2 The Code of Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (Code formulated by the Tri-Council

Working Group) in Canada for instance specifies: "Researchers should not publish any part of their

research that could lead to inadvertent identification of individuals." Other codes also specify such

practices. The draft code suggests : "III.5.6...As far as possible the publication should give only the

relevant information and avoid giving markers that might lead to the possible identification of the

participants."

’ The Tri-Council Code suggests that" women should be represented in proportion to their presence in the

population affected by the research" which rule may apply to other groups and communities within the

study population.

4 Language is used sometimes to cover up indifferent research and lack of rigour and is a good rule of

thumb, though it cannot be a decider. Also since the business of a journal is dissemination, there is reason

to be sensitive to convoluted language.

5 Incomplete referencing should prompt a doubt in the editor's/refreee’s mind that the author may not know

the work cited very well. This also applies to text which is incomplete or in obvious ways misquoted.

Background Papers

9

papers presented at seminars or published in disciplinary journals. In the social sciences

this distinction is not so clear. In fact on the face of it there seems to be very little room

for observing such a practice.

However, it must be stressed that the publication of research outcomes of social science

research, and especially in health and health care, which has not been subject to peer

review or the scrutiny of the population under study can be harmful, misleading and may

even be dangerous and certainly unethical. Journalists and editors working in the popular

media have a special responsibility to ensure that there has been adequate opportunity for

research results to have received peer attention.

It may be noted here that there are cautions here for the researcher as well. For instance,

the Code of Ethics of the American Anthropological Association states that

anthropologists in publishing their work "are not only responsible for the factual content

of their statements but also must consider carefully the social and political implications of

the information they disseminate. They must do everything in their power to insure that

such information is well -understood, properly contextualised, and responsibly utilise_d"

(emphasis mine).

The draft code also suggests "III.7.4 ...Researchers who choose to do so [publish or

disseminate their research results in the popular media] have a special responsibility to

ensure that the ethics in research are not disregarded and the results of research have been

afforded a peer review. Journalists and the media that publish these research results have

a responsibility to publish the results truthfully and honestly".

This is an important part of the code and needs to be widely emphasised. Especially with

the growth of social science research especially in health, especially impinging on policy

affecting the lives of people which do often need wider dissemination even before they

are published in academic journals.

The draft guidelines puts great weight by dissemination of research results to the affected

or involved population and social scientists in their capacity as journalists and editors in

the popular press need to acknowledge that if the study population has not been told the

research outcomes, then the research may not deserve the kind of publicity which will

accrue from its publication in any form in the popular press.

With the easy availability of international academic journals on the world wide web,

there is an increasing tendency, especially in health and medicine, to cull information

from published academic papers. It is best in fact to allow for discussion to develop

within the academic community on particular papers before reporting the research in the

popular press (unless of course if there has been a press conference and even then

journalists should check if there has been adequate peer review). In the event of there

being an urgency to report the research, then it is imperative that the journalist should

conduct an independent 'peer review' of sorts eliciting the opinion of other academics in

the field. Today with modem means of communication, this is not at all difficult.

Background Papers

10

Similar cautions should be exercised in writing up interviews. Cross-checking facts/data

with the interviewee is necessary in all disciplines not only in the natural sciences and

technology.

There are today in India associations of journalists specialising in science or in

environmental issues. But have done little towards clarification of some of the issues

mentioned above.

VI: Role of editors in cyberspace

Between the time this paper was commissioned and now I have come to realise that the

vast new communication media opening up through the internet is completely uncharted,

with few signposts. There is very little in the form of legislation and copyright laws are

being tested severely. In social sciences there at least three academic social science

journals which are entirely on the internet. While they have processing norms for papers,

giving that the medium allows for a more rapid turnover and response rate, it gives rise to

a number of problems in publishing. These are only now being even defined. Moreover,

there is little clarity on the norms for individual researchers to 'publish’ papers, articles

and even books on the internet on their personal web pages. Who governs this kind of

publishing? How does the process of peer review apply here? Is this sort of publication

itself in a manner of speaking, an opportunity for peer review? How do copyright laws

apply? We need to recognise the fact that may make it more difficult to process. And

while copyright laws are being evolved and codification is under way, it will take a while

for norms and conventions to develop.

VII: What Needs to be Done?

Evidently, there is an urgent need to formulate code/s of ethics for academic publishing.

A first step is in fact to build a consensus for evolving such a code. The code of ethicshowever rudimentary- evolved by the various press associations could be a starting point

and may in fact play a lateral role in reviving interest in strengthening a code of conduct

for journalists as well.

An attempt must be made to create a space for communication among academic journals

and their editors. So far academic journalism in India has been at a rudimentary level.

Indian social science journals do not as a rule attract serious academic attention abroad

for many reasons. One of these reasons is the uneven quality of academic presentations in

these journals. If good, ethical and effective social sciences as academic disciplines are to

grow, then social science journals need to review their performance. With increasing

research output within India and on India and South Asia, there is a potential for

specialist academic journals. Without a forum such as this, it would be very difficult to

emphasise and encourage rigour in academic research.

Background Papers

11

Moreover, it must be kept in mind that in India there is a tradition of remarkable

academic research in social sciences being undertaken by groups and bodies and

individuals who have no affiliation to large academic bodies and who may be part of

activist and political groups. While such research has played an important role in the

continued vitality of the social sciences, there has been much discussion about its

academic rigour and such issues as bias. This is a significant tradition, which often

challenges dogmas and dominant paradigms within academic circles. If academic

journals are to allow space for these while at the same time not fall into the trap of

publishing ’biased’ research or studies without adequate rigour, then we need to have a

forum for discussing such issues and arriving at broad guidelines.

In conclusion, it should be apparent that codes, guidelines and norms do not in

themselves make for good, ethical research. To quote the Tri-Council Code

Good ethical reasoning, like good reasoning in research, must be more than a matter of

mechanical and dogmatic application of rigid rule to fact situations. Ethical reasoning

requires thought, insight and sensitivity. As in research peer judgement is important. In