LEARNING FACILITATION WORKSHOP

Item

- Title

- LEARNING FACILITATION WORKSHOP

- extracted text

-

CLP

lC

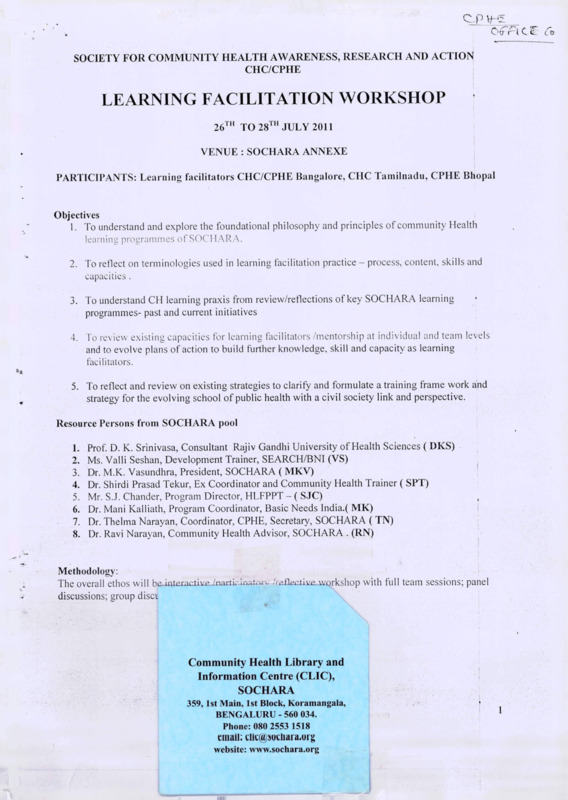

SOCIETY FOR COMMUNITY HEALTH AWARENESS, RESEARCH AND ACTION

CHC/CPHE

LEARNING FACILITATION WORKSHOP

26th TO 28™ JULY 2011

VENUE : SOCHARA ANNEXE

PARTICIPANTS: Learning facilitators CHC/CPHE Bangalore, CHC Tamilnadu, CPHE Bhopal

Objectives

1. To understand and explore the foundational philosophy and principles of community Health

learning programmes of SOCHARA.

2. To reflect on terminologies used in learning facilitation practice

capacities .

process, content, skills and

3. To understand CH learning praxis from review/reflections of key SOCHARA learning

programmes- past and current initiatives

4. To review existing capacities for learning facilitators /mentorship at individual and team levels

and to evolve plans of action to build further knowledge, skill and capacity as learning

facilitators.

*1

5. To reflect and review on existing strategies to clarify and formulate a training frame work and

strategy for the evolving school of public health with a civil society link and perspective.

Resource Persons from SOCHARA pool

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Prof. D. K. Srinivasa, Consultant Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences ( DKS)

Ms. Valli Seshan, Development Trainer, SEARCH/BNI (VS)

Dr. M.K. Vasundhra, President, SOCHARA ( MKV)

Dr. Shirdi Prasad Tekur, Ex Coordinator and Community Health Trainer ( SPT)

Mr. S.J. Chander, Program Director, HLFPPT - ( SJC)

Dr. Mani Kalliath, Program Coordinator, Basic Needs India.( MK)

Dr. Thelma Narayan, Coordinator, CPHE, Secretary, SOCHARA ( TN)

Dr. Ravi Narayan, Community Health Advisor, SOCHARA . (RN)

Methodology:

The overall ethos will be interactive /nartic.inatnrv /raflnc.tive workshop with full team sessions; panel

discussions; group disci

Community Health Library and

Information Centre (CLIC),

SOCHARA

359,1st Main, 1st Block, Koramangala,

BENGALURU - 560 034.

Phone: 080 2553 1518

email; clic@socliara.org

website: www.sochara.org

1

Lo

Ifeiso’

C4C

<

Date

26.07.20TT

(Tuesday)

Time___ _____________________ Program me

T

THE PHILOSOPHY OF LEARNING FACILITATION

Theme for the

day:

9.30 am > Introduction

10.30am __

> Self Assessement ( Training facilitation Score)

Tea Break

10.3011 .QOam

11.GOSession -I : Exploring Building Blocks in Learning Facilitation

12.00pm

( RN)

( Dichotomies and Paradigms: content and process issues, skills,

and capacities)

12.001.00pm

Session -II : Challenges in Learning Facilitation : Context,

Values and Conflict resolution. (VS)

1.00-2.00

2.00-3.00

____________ Lunch and Fellowship________________________

Session - III : Inspiration for Learning Facilitation ( RN)

(Exploring training resources/inspiration that provoked /supported

SOCHARA experiments ( An interactive session)

3.00-3.15

3.30-4.45

_______________________ Tea Break____________________

Session - IV Group Discussion-I

Identifying challenges from praxis in Bangalore /Chennai/ and

Bhopal teams. ( Check List)______________________________

____________________ Staff Get together_________________

Assessing Training experiences

(Am I a good learning facilitator/field mentor/ mentor - A self

assessment and reflection)______________

MANAGEMENT AND METHODS OF LEARNING

FACILITATION

4.45-5.30

(Home work)

27th July 2011

(Wednesday)

Theme for the

day:

9.30- 10.30

10.30- 10.45

10.45- 11.45

I

11.45- 1.15

1.15-2.00

2.00-3.15

____

3.15-3.30

3.30-4.30

4.30-5.30

Reflections on Day One - Key learning /more questions________

_______________________ Tea Break______________________

Session- V : Learning facilitation - (RN)

Why/Who/What/HowAVhen/Where - Evolving a check list

Session VI: Exploring and understanding structure and frame

work- basic concepts-(DKS)

(Curriculum/Syllabus/ Objective/ Modules/ methods / assessment/

evaluation)

_____________ Lunch and Fellowship__________________

Session VII - Challenges in Community based training

strategies for Health and Non Health Groups - ( SPT)

_________________ Tea break__________________________

Session- IX: Civil Society School for Scholar Activists ( TN)

>

Strategies towards a school for scholar activist

Revisiting what we are doing with a new SPH Lens

Role and definition of a scholar activist___________________

Group Discussion on SOCHARA - Website ( CLIC team)

2

IJ

28th July 2011

(Thursday)

Theme for

the day:

9.30-10.30

10.30- 10.45

10.45- 11.45

LEARNING FROM SOCHARA PRAXIS /FUTURE

PLANS

( Reflections of Day Two)

(Key learning / more questions)_________

____________________ Tea Break________________

Session VIII: Planning a learning program - An A- Z

Check list (RN)

11.45-1.15

Session X

Chairperson : Dr. M.K.Vasundhra

Exploring SOCHARA Praxis ( Principles / Learning)

Case studies:

1. Health for Non Health Group - ( MK)

(Textual - Contextual)

2. VVomen’s Health Empowerment Training -(TN)

( Perspective/Manuals/ToT/ Arogya Mela/ Evaluation)

3. Community Health Trainers Network - (RN)

( Frame work/Manuals/Learning network meetings)

1.15-2.00

2.00-3.00

________________ Lunch and Fellowship_________

Session X ( Contd)

4. Lessons from interactive programmes- Life Skill

Education and Joyful Learning series - ( SJC)

(adapting learning to group/joyful learning series)

3.00-3.15

3.15-4.00

____________________ Tea break

Session - XI : ( Group Discussions)

Setting individual and collective group goals

a. Bhopal Plan

b. Bangalore Plan

c. Chennai Plan

4.00- 5.00

Concluding session and winding up :

SOCHARA Plan - Finalizing Strategies: (To be reported at

AGBM)

3

i ■ •

1 i

Learning Facilitation Workshop ( SOCHARA)

26th, 27th and 28th July 2011

A - Background Papers and Documents.

1. Health and the Right to Health - from Limits to Medicine - Ivan illich

2. The Hierarchy of Needs - Maslow and other models

3. Banking Education and Liberating Education- Pedagogy of the oppressed. Paulo Freire

4. Approaches to Training — ( EL), John’s Staley

5. Our ideas about Training

6. The learning model - Action- reflection

7. Training and Learning

8. The individual in the Group

9. Do we listen? - A questionnaire

10. How are we doing ? Widening evaluation

1 I. Looking inwards - The individual ( Values, Empathy and Feedback- from People in

development, John Staley, SEARCH

12. A perspective on conflict

13. Managing conflict in an organization

14. Dealing with Conflict

15. Approaches to planning

16. Our approach to planning - A questionnaire

17. Planning a training program - from Helping Health Workers Learn - David Werner and Bill

Bower

18. SEARCH training papers

a) Respect for other people

b) The conditions for learning

c) Leadership Quiz

d) Solving problems and making decisions

e) Elements of team work

f) Group discussions and meetings

g) Empathy and Sympathy

h) Feedback

i) Case studies - episode and cases

j) Setting goals

19. Education Policy for Health Sciences-A statement of shared concern and collectivity

from Community Health Trainers dialogue - 1991, (SOCHARA)

20. A tollective approach to Training - The CHC / SOCHARA model ( from the trainers network

Project)

4

i

4

11

B - BASIC READING LIST FOR SOCHARA LEARNING

FACILITATORS

1. Limits to Medicine - Medical Nemesis: The expropriation of Health, Ivan Illich, Penguin

books

2. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Friere, Penguin education

3. Writing for Distance Education : A Manual for writers of distance teaching texts and

independent study materials, The international extension College 1979

4. Teaching for better learning - A guide for teachers of Primary Health Care staff , F.R.

Abbatt, World Health Organisation, Geneva, 1980

5. People in Development - A trainers manual for groups , John Staley , SEARCH, 1982

6. Helping Health Workers Learn - A book of methods, aids and ideas for instructors at

village level, David Werner and Bill Bowers, The Hesperian Foundation, 1982

7. From development worker to activist- A case study in participatory training, Desmond A.

D’Abreo , Deeds, 1989

8. Community Health Trainers Dialogue, Oct 1991, CHC SOCHARA workshop report

9. Enticing the learning - Trainers in development, John Staley, University of Birmingham,

UK, 2008

10. Learning programmes for Community Health and Public Health - Report of the

National Workshop - April 2008 (A CHC Silver Jubilee publication)

t

5

t

4

7^

■ X " ''C

>

-j

’’

■

■■

i

. i

M

Limits

to Medicine

Medical Nemesis:

The Expropriation of Health

IvanlUich

i

)

j

Penguin Books

c-

i

1

>

The Politics of Health

desirable to base the limitation of industrial societies on a shared

system of substantive beliefs aiming at the common good and

enforced by the power of the pol.ee. It is possible o find he

needed basis for ethical human action without depending on

shared recognition of any ecological dogmatism now in vogue.

This alt^iv^Q- a^^PJeg^1 re^lRn, 9r

Xal

based -S^agreerpepL about basic values and on procedural

270

1

Ine Recovery of neumi

specificgoalsj^k-sharc..’

on their useofle^al and political

■^TU'rTTThat permit individuals and groups.to resolve conn^lShromSeir^m: ‘-mteent goals. Better mobility

depend not dn some m- kind of transportation system

Cut on conditions that make personal mobility under personal

control more valuable. Bern.; learning opportunities will de

pend not on more inform.mon about the world better disKibu’ted but on the Umitatmo of capital-intensive product.on

for the s’ake of interesting wotkmg conditions. Better health care

ihcrapcjlic standard, but on the

will depend, not on some iK'*: to engage in self-care. The

level of willingness and competence

recognition of our presrecovery of this power depends on the

t

TTmu be demonstrated that beyond a certain point in the

expansion of industrial production in any major field of value

marginal utilities cease to be equitably distributed and ovcral

effectiveness begins, simultaneously, to decline,Ifthemd^trial

mode of..product ion expands-beyond a certain ^ge and com

tinues to impinge on-the autonomous mode, increased perso

suffering and social dissolutiomset in. .In the interim bet

the point of optimal synergy between industrial and au’on°rnous production and the point of maximum tolerable industrial

hegemony - political and juridical procedures become necessary

(o reverse industrial expansion. If these procedures are con

ducted in a sp.r.t of enlightened self-interest and a des.re for

survival and with equitable distribution of social outputs and

equitable access to social control, the outcome ought to be a

recognition of the carrying capacity of the environment and

of the optimal industrial complement to autonomous action

needed for the effective pursuit of persona! goals. Political pro

cedures oriented to the value of survival in distributive and

participatory equity are the only possible rational answer to increasing total management in the name of ecology.

TMlSSSaSIXof ;>£>suijal au-tmtomy. wiTtlms bc.lhe reAulLp

political action reinfprcipg^aii_eLhica.LAwakeniiig..Ecop

. \ want to limit'.ransporution because they want to move eflic entI I |y freely and wiih equity; they will limit schooling because they

I want to share equally the opportunity, time, and motivation to

' learn m rather than about the world; people will limit medical

I' therapies because they want to conserve their opportunity and

power to heal. They will recognize that only the disciplined

I limitation of power can provide equitably shared satisfaction.

The recovery of autonomouj_agUfta^Ul^epen^jaat--00-<iaw

T

i

ent delusions.

I

The Right to Health

Increasing and irreparable damage accompan.es present mdustX expansion in all sectors. In medictne th.s damage

appears as iatrogenesis. Uttogenes^ ts clmtcal^hen pam

ness and deathjasultlrgm medical careak !S.social when W

no'licies reinforce an industrial o.rgamzatiop that generates dlheakh- it is cultural and symbolic when med.cally sponsored

behaviour and delusions resiricLihe s ital. autonomy of peop

£ un^SininniTr competence m growmg up. caring or

1

i

each other, and ageing, o. when medical mtervent.on cripples

personal responses to pain, disability, impairment, angmsh. and

I

^Most of the remedies now proposed by the social engineers

___ include

and economists to reduce iatrogenesis

include aa further

further increase

increase

: so-called rcmcciies.generaLe~se.c.ondof medical controls. These

---<hev

order iatrogenic ,11s on cac

eachh of the three critical levels:

levels, they

rente clinical, social, and cultural iatrogenesis self-rein forcing.

The most profound iatrogenic effects of the medical techno

structure are a result of those non technical functions whic^

j

j

|

support the increasing institutiomtlixation o va

technical and the non-teclmical consequences of institutional

27!

j

j

I

1

Tiie Recovery of Health

The Politics of Health

tion would tax medical technology and professional activity ’■ '

until those means that can be handled by laymen were truly ;

available to anyone wanting access to them. Instead of

•

plying the specialists who can grant any une of a variety of sickroles to people made ill by their work and their life, the new ■

legislation would guarantee the right of people to drop out and

to organize for a less destructive way of life in which they have

more control of their environment. Instead of restricting access^

to addictive, dangerous, or useless drugs and procedures, such :

legislation would shift the full burden of their responsible use

on to the sick person and his next of km. Instead of submitting

the physical and mental integrity of citizens to more and more j *

wardens, such legislation would recognize each man s right to ;

define his own health - subject only to limitations imposed by

^es^ct’fo/his neighbour's rights. Instead of strengthening^the

medicine coalesce and gen^ajc^Aew-km^Qf^u^

lhelized. impoicnt,.and solitary survival in a world turned into a

hospital ward. Medical nemesis is the experience of people who

are largely deprived of any autonomous ability to cope with

nature, neighbours, and drcams, and who are technically main

tained within environmental, social, and symbolic systems.

Medical nemesis cannot be measured, but its experience can be

shared. The intensity with which it is experienced will depend on

the independence, vitality, and relatedness of each individual.

The perception of nemesis leads to a.choice,^‘^her dtenatural

boundaries of human .endeavour are estimated^recogmzed^a nd

transf^x^^

or^^^^Xsur'

vivliYn 1 planned and engineered.hellj’s^^te£asjhealurnative KTSfnction. Until recently the cho.ce between the

poiitics'of'voluntary’poverty and the hell of the systems en

gineer did not fit into the language of scientists or politicians.

Our increasing confrontation with medical nemesis now lends

new significance io the alternative: either society must choose

the same stringent limits on the kind of goods produced wnhm

which all its members may find a guarantee for equal freedom,

or society must accept unprecedented hierarchical controls to

provide for each member what welfare bureaucracies diagnose

licensing power of

specialized

government

agencies,

-ould

give the peers

publicand

a voice

in the election

of JJ

new legislation wc— w

healers to tax-supported health jobs. Instead of submitting their

performance to professional review organizations, new legisla- ;

tion would have them evaluated by the community they serve.

:

........ h

I

1

1

I

I

!

Health as a Virtue

as his or her needs.

.

.

In several nations the public is now ready for a review of its

heahh-care system. Although there is a serious danger that the

forthcoming debate will reinforce the present frustrating medicalization of life, the debate could still become fruitful if atten

tion were focused on medical nemesis, if the recovery of per

sonal responsibility for health care were made the central issue,

and if limitations on professional monopolies were made the

major goal of legislation. Instead of limiting the resources of

doctors and of the institutions that employ them, such legisla-

!

Health designates a process of adaptation. It is not the result

of instinct, but of anj^ojxQWO^yetxulm^

t0^S0.cialb:..c^L£d4^y. It designates the ability to adapt to

changing environments, to growing up and to ageing, to healing

when damaged, to suffering, and to the peaceful expectation of

death. Health embraces the future as well, and therefore in

cludes anguish and the inner resources to live with it.

Health designates a process by which each person is respons

ible, but only in part responsible to others. To be responsible

may mean two things. A man is responsible for what he has

done, and responsible to another person or group. Only when he

feels subjectively responsible or answerable to another person

will the consequences of his failure be not criticism, censure, or

3 The Honourable James McRurr. Ontario Royal Commission Inquiry into

Cru/Jdg/rrstToromo: Queen s Poorer. t968. 1969. t97t). On self-governmg

professions and occupations, see chap. 79. The grant,ng of ^Ho^nmen

is a delegation of legislative and judicial funcuons that can be justified only

as a safeguard to public interests.

2

273

272

----- - -4

■

.......uHlitiT"-....... jaiiifl

The Recovery of Health

The Politics of Health

punishment but regret, remorse, and true repentance.4 The con

sequent states of grief and distress are marks of recovery and

healing, and are phenomenologically something entirely differ

ent from guilt feelings. Health is a task, and as such is not com

parable to the physiological balance of beasts. Success in this

personal task is in large part the result of the self-awareness,

self-discipline, and inner resources by which each person reg

ulates his own daily rhythm and actions, his diet, and his sexual

activity. Knowledge encompassing desirable activities, com

petent performance, the commitment to enhance health in

others - these are all learned from (he example of peers or

elders. These personal activities are shaped and conditioned by

the culture in which the individual grows up: patterns of work

and leisure, of celebration and sleep, of production and pre

paration of food and drink, of family relations and politics.

Long-tested health patterns that fit a geographic area and a

certain technical situation depend to a large extent on longlasting political autonomy. They depend on the spread of

responsibility for healthy habits and for the socio-biological

environment. That is, they depend on the dynamic stability

of a culture.

The level of public health corTg§.po£ds tq^the degree to which

the means and responsibility for coping with illness are dis

tributed among the total population. This ability to cope can be

enhancedTJut never replaced by medical intervention or by the

hygienic characteristics of the environment. Iii.at_society which

can reduce professional intervention to the minimum will pro

vide the best conditions Tor-health. The greater the potential for

autonomous adaptation to self, to others, and to the environ

ment, the less management of adaptation will be needed or

tolerated.

A world of optimal and widespread health is obviously a

world of minimal and only occasional medical intervention.

Healthy people are those who live in healthy homes on a healthy

diet in an environment equally fit for birth, growth, work, heal-

ing, and dying; they arc sustained by a culture that enhances the |

conscious acceptance of limit- to population, of ageing, of in- J

complete recovery and ev<

eminent death. Healthy people

need minimal bureaucratic interference to male, give birth,

share the human condition, arid die.

Man’s consciously lived Lagility,Jncj.ivyu^^d^rdatedness make the experience of pain, of sickness, and of death an

^Tnte'gral pari of his life. The ability io ccpe with this trio autono

mously is fundamental to his health. As he becomes dependent

on the management of his mtimacy, he renounces his auto

nomy and his health must decline. The irue miracle of modern

medicine is diabolical. It consists in making not only individuals

but whole populations survive on inhumanly low levels of per

sonal health. Medical nemesis is the negative, feedback of a

social organization that set out to -improve.the

opportunity for each man to cope in autonomy andended by

i

destroying it.

5

4

j

4. Alfred Schutz. ‘Some Equivocations in the Notion of Responsibility',

in Collected Papers, vol. 2, Studies in Social Theory (The Hague: NijhofT,

1964), pp. 274-6.

274

•

i

1

“1

A/

•y?"

?

A

THE HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

I: ORIGINAL PROPOSITION

(ABRAHAM MASLOW)

Self actualization need

Esteem needs

MATURATION PROCESS:

REALIZATION OF

GENETIC POTENTIAL

Belongingness needs

Safety needs

Physiological needs

h

II: EXPANDED PROPOSITION - THE Y MODEL

(Y. YU)

GENETIC

EXPRESSION

GENETIC

TRANSMISSION

Self actualization

need

Esteem needs

Belongingness needs

Parenting

needs

Reproduction needs

Sexual needs

Safety needs

GENETIC

SURVIVAL

Physiological needs

7

III : GENETIC EXPRESSION CHANNELIZED

IN CONTRASTING SOCIETAL SYSTEMS

NEED

LEVEL

COLLECTIVISTIC INDIVIDUALISTIC

SOCIETAL

SOCIETAL

SYSTEM

SYSTEM

Self

actualization

Contributing

Personal

to community

development accomplishment full potential

Esteem

Primacy of

social esteem

Primacy of

self esteem

Belongingness Cohesion in

relationships

Self interest

through

relationships

Safety

Physiological

I

GENETIC

EXPRESSION

Unlikely

differentiation

GENETIC

SURVIVAL

Unlikely

differentiation

IV : REVISED PROPOSITION

(KUO-SHU YANG)

COLLECTIVISTIC

GENETIC EXPRESSION

DOUBLE Y MODEI^

GENETIC TRANSMISSION

INDIVIDUALISTIC

GENETIC EXPRESSION

CSA

Parenting

needs

CE

ISA

Reproduction

needs

C

CSA: Collectivistic

self actualization

ISA: Individualistic

Self actualization

CE:

Collectivistic

esteem

IE:

Individualistic

esteem

CB: Collectivistic

belongingness

IB:

Individual ictir

belongingness

1

Sexual

\ needs /

IE

IB

— Safety needs

Physiological needs

.i- XS

■WS ■

1

Chapter 2

j

j

f

Pedagogy

of the Oppressed

Paulo Freire

Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos

A careful analysis of the teacher-student relationship at any

level, inside or outside the school, reveals its fundamentally.

namitivc character. This relationship involves a narrating

Subject (the teacher) and patient, listening objects (the students):

The contents, whether values or empirical dimensions of reality,,

I

tend in the process of being narrated to become lifeless and

I

Penguin Education

r

petrified. Education is suffering from narration sickness.

The teacher talks about reality as if it were motionless, static,

compartmentalized and predictable. Or else he expounds on a

topic completely alien to the existential experience of the

students. His task is to ‘fill’ the students with the contents of

his narration - contents which are detached from reality, dis

connected from the totality that engendered them and could

give them significance. Words are emptied of their concreteness

and become a hollow, alienated and alienating verbosity.

The outstanding characteristic of this narrative education,

then, is the sonority of words, not (heir transforming power,

‘.(•'our limes four is sixteen; the capital of Para is Belem.’ The

student records, memorizes and repeats these phrases without

perceiving what four times four really means, or realizing the

true significance of ‘capital' in the affirmation ‘the capital of

Para is Belem,' that is, what Belem means for Para and what

Para means for Brazil.

Narration (with the teacher as narrator) leads the students to

memorize mechanically the narrated content. Worse still, it

turns them into •containers’, into receptacles to be filled by the .

teacher. The more completely he fills the receptacles, the better a

teacher he is. The more meekly the receptacles permit them

selves to be filled, the better students they are.

Education thus bccom.es an act of depositing, in which the

students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor.

Instead of communicating, (he teacher issues communiques

4

i-

1

46

B'

1

and ‘makes deposits’ which the students patiently receive,

memorize, and repeat. This is the ‘banking’concept of educa

tion, in which the scope of action allowed to the students

extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits.

They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or

cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is

men themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity,

transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided

system. For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, men

cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through

invention_.and re-jnvention, through-the..restlessT"impatient,

continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in the world, with the

world, andwith each other.

In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift

bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable

upon those whom they consider to know nothing. Projecting

an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the

ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as

processes of inquiry. The teacher presents himself to his students

as their necessary opposite; by considering (heir ignorance

absolute, he justifies his own existence. The students, alienated

like the slave in the Hegelian dialectic, accept their ignorance as

justifying the teacher’s existence - but, unlike the slave, they

never discover that they educate the teacher.

IB

H

13

ii--

ft'

I

5. The teacher disciplines and the students are disciplined.

!

8. The teacher chooses the programme content, and the students

(who were not consulted) adapt to it.

9. The teacher confuses the authority of knowledge with his

own professional authority, which he sets in opposition to the

freedom of the students.

10. The teacher is the subject of the learning process, while the

pupils are mere objects.

It is not surprising that rhe banking concept of education

regards men as adaptable, manageable beings. The more

students work at storing the deposits entrusted to them, the less

they develop the critical consciousness which would result

from their intervention in the world as transformers of that

world. The more completely they accept the passive role im

posed on them, the more they tend simply to adapt to the world

as it is and to the fragmented view of reality deposited in them.

The capacity of banking education to minimize or annul (he

students’ creative power and to stimulate their credulity serves

the interests of the oppressors, who care neither to have the

world revealed nor to see it transformed. The oppressors use

their ‘humanitarianism’ to preserve a profitable situation. Thus

reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both arc

simultaneously teachers ^//z/students.

This solution is not (nor can it be) found in the banking

concept. On the contrary, banking education maintains and

even stimulates the contradiction through the following attitudes

and practices, which mirror oppressive society as a whole:

2. The teacher knows everything and the students know nothing.

3. The teacher thinks and the students are thought about.

4. The teacher talks and the students listen - meekly.

6. The teacher chooses and enforces his choice, and the students

comply.

7. The teacher acts and the students have the illusion of acting

through the action of the teacher.

The rG/5o/^/’e£rejo£liber^aj2i<UT_educatiom on the other hand,

lies in its drive_towards_reconciliation. Education must begin

with the solution of the_ teacher-studen_t_ conFradiction, by_

1. The teacher teaches and the stncicnis arc taughL

!

47

they react almost instinctively against any experiment in educa

tion which stimulates the critical faculties and is not content

with a partial view of reality but is always seeking out the ties

winch link one point to another and one problem to another.

Indeed, the interests of the oppressors lie in ‘changing the

consciousness of the oppressed, not the situation which op

i

presses them' (Simone de Beauvoir in La Pensee de Droite

Aujuurd'hili') for the more the oppressc'd-cim be led to adapt to

that situation, the more easily they can be dominated. To

achieve this end, the oppressors use the hanking concept of

education in conjum-tion with a paternalistic social action

apparatus, within which the oppressed receive the euphemistic

it I

I

r

I

rI

?

T

A'

T

I

II

i

I

1

j'W

1j

ill

' m

t/'-z-'Gc pvv’. M'dj) y

}48

/

/ title of ‘welfare recipients’. They are treated as individual

\

)

o

i

It

i

it '

cases, as marginal men who deviate from the general con

figuration of a ‘good, organized, and just’ society. 1 he op

pressed are regarded as the pathology of the healthy society,

which must therefore adjust these ‘incompetent and lazy folk

to its own patterns by changing their mentality. These mar

ginals need to be ‘integrated’, ‘incorporated into the healthy

society that they have ‘forsaken’.

The truth is, however, that the oppressed are not marginals,

are not men living ‘outside’ society. They have always been

iT

ZIdT -^lnside the structure which made them ‘beings for

inside

'others\~The solution is not to * integrate’ them into the structure

of oppcession, but to transform that structure so that they can

become^ ‘ beings fo r themsely^^Such _ t cans form a t i o rg^ f

course, would undermine the oppressorXd?Urpos^Xi-hSJlQfe.kh£ir

utilization..ofdhe. banking concept of education to avoid the

threat of student conscientization.

The banking approach to adult.education, for example, will

never propose to students that they consider reality critically. It

will deal instead with such vital questions as whether R.oger

gave green grass to the goat, and insist upon the importance of

learning that, on the contrary, Roger gave green grass to the

rabbit. The ‘humanism’ of the banking approach masks the

effort to turn men into automatons — the very negation of their

ontological vocation to be more fully human.

Those who use the banking approach, knowingly or un

knowingly (for (here are innumerable well-intentioned bank

clerk teachers who do not realize that they are seiving only to

dehumanize), fail to perceive that the deposits themselves con

tain contradictions about reality. But, sooner or later, these

contradictions may lead formerly passive students to turn

against their domestication and the attempt to domesticate re

ality. They may discover through existential experience that their

present way of life is irreconcilable with their vocation to become

, fully human. They may perceive through thenj-Qlations

ality that reality is really a process, undergoing constapUxausv ‘Tormatj^ii^ iFmen are searchers and their ontological vocation

is humanization, sooner of later they may perceive the contra

diction in which banking education seeks to maintain them, and

43

-’/.yt /

d/'-y rV! —

f'JJ

/hen engage thcmselvc in the struggle for their liberation.

But the humanist, revolutionary educator cannot wait for

this possibility to materialize. From the outset, his efforts must

coincide with those of the students to engage in critical thinking

and the quest for mutual humanization. His efforts musCbc

imbued with a profound [rust in men and their creativejpoy^er.

Trr^EiewrTFHs^

be a partner of the students injijg

relations with them.

The banking concept does not admit to such a partnership and necessarily so. To resolve the teacher-student contradic

tion, to exchange the role of depositor, prescriber, domesticator,

for the role of student among students would be to undermine

the power of oppression and to serve thecause of liberation.

Implicit in the. banking concept is the assumption of a

dichotomy between man and the world: man is merely in the

world, not with the world or with others; man is spectator, not

rc-creator. In this view, man is not a conscious being (corpo

consciente)} he is rather the possessor of a consciousness; an

empty ‘mind’ passively open to the reception of deposits of

reality from the world outside. For example, my desk, my books,

my coffee cup, al) the objects before me - as bits of the world

which surrounds me - would be ‘inside me, exactly as I arn

inside my study right now. Tins view makes no distinction

between being accessible to consciousness and entering con

sciousness. The distinction, however, is essential: the objects

which surround me are simply accessible to my consciousness,

not located within it. I am aware of them, but they are not

inside me.

Ji follows logically from the banking notion of consciousness

that the educator’s role is to regulate the way the world ‘enters

into’ the students. His task is to organize a process which

already happens spontaneously, to ‘ fill ’ the students by making

deposits of information which he considers constitute true

knowledge.1 And since men ‘receive’ the world as passive

J. This concept corresponds to what Sartre calls the ‘digestive’ or

‘nutritive’ concept of cdu-. ■.iion, in which knowledge is ‘fed’ by the

teacher to the students to Till them out’. See Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘Unc

ideeTondamcntale de la pl;.aomiinoiogic de Husserl; 1 intentionality ,

Siiuaiiotis I.

I

1

I

1

I

3

t

I

I1

J

|

I

■i

|

i

1

|

|

|

I

'"5

i

I

1

50

51

endt es education should make them more passive stin. and

adapt them to the world. The educated man is the adapted man

b^^^s more7H^oTnje^^

’

whcsL tranqu^lny rests on how well men fit tlw wofd the

The more completely tne majority adapt to the purposes

which the dominant minority prescribe for them (thereby

depnvmg them of the right to their own purposes), the more

eas.Iy the mmonty can continue to prescribe. The theory and

practice of banking education serve this end quite efficiently

Verbabstic lessons, reading requirements? the methods for

evaluating ‘knowledge’, the distance between the teacher and

the taught, the criteria for promotion: everything in this ready-

to-wear approach serves to obviate thinking.

The bank-clerk educator does not realize that there is no true

security in his hypertrophied role, that one must seek to live

>w//i others in solidarity. One cannot impose oneself, nor even

merely co-exist wKh one’s students. Solidarity requires true

communication, and the concept by which such

an educator is

guided fears and proscribes communication.

Yet only throygh communication can human life hold

meaning. The teacher’s thinking is authenticated only by the

authenticity of thestudents’ thinking. The teacher cannot think

for h.s students, nor can he impose his thought on them

Anthemic.^km^^m^thaHs concerned about

^2HykyPlace

ivory-tower isolatioTTl^^”

™™«!ion7mt IS true that thought has ^ffi^TT'\^hen

generated by action upon the world, the subordination of

students to teachers becomes impossible.

Because banking education begins with a false understanding

o men as objects, it cannot promote the development of what

Fromm, m The Heart of Man, calls ’biophijy’, but instead

produces its opposite: ‘necrophily

While life is ehimictcfized-by growth in a structured lunctiomi! man

ner, the necrophilous person loves all that docs not’grow, all' tha't is

2. For example, some teachers specify i.uheir reading lisls lh,,

book should be -d from pages «0 to ! 5 - n„d do this ,o ’IJ!p

students’

mechanical. The necrophilous person is driven by the desire to trans

form the organic into the inorganic, to approach life mechanically,

as if all living persons were things. . . . Memory, rather than experi

ence; having, rather than being, is what counts. The necrophilous

person can relate to an object - a flower or a person - only if he

possesses it; hence a^threa£td his possession is a threat to himself;

if he loses possession he loses contact with the world. ... He loves

control, and in the act of com roll mg he kills life.

Oppression - overwhelming control - is necrophilic; it is

nourished by love of death, not life. The banking concept of

education, which serves the interests of oppression, is also

necrophilic. Based on a mechanistic, static, naturalistic,

spatialized view of consciousness, it transforms students into

receiving objects. It attempts to control thinking and action,

leads men to adjust to the world, and inhibits their creative

power.

When their efforts to act responsibly are frustrated, when they

find themselves unable to use their faculties, men suffer. ‘This

suffering due to impotence is rooted in the very- fact that the

human equilibrium has been disturbed’, says Fromm. But the

inability to act which causes men’s anguish also causes them to

reject their impotence, by attempting

■ ■ • to restore [their] capacity to act. But can [they], and how? One

way is to submit (q_and identify with a person,ot_£rc>iip~having

power. By this symbolic participation in another person’s Tile,~[mcn

Kave] iHeTnusToF of acting, when.m reality .[they] only submTto'and

become a part of those who act.

Populist manifestations perhaps best exemplify this type of

behaviour by (he oppressed, who, by identifying with charis

matic leaders, come to feel that they themselves are active and

effective. The rebellion (hey express as they emerge in the

historical process is motivated by (hat desire to act effectively.

The dominant elites consider the remedy to be more domination

....and repression, carried out in the name of freedom, order anrf

social peace (the peace of the elites, that is). Thus they can

condemn - logically, from (heir point of view - ‘the violence of a

strike by workers and [can] call upon the state in the same

breath to use violence in putting down the strike’ (Niebuhr’s

Moral Man and Immoral Society),

iI

b- •

52

Education as the exercise of domination stimulates the

credulity of students, with the ideological intent (often not

perceived by educators) of indoctrinating them to adapt to the

world of oppression. This accusation is not made in the naive

hope that the dominant elites will thereby simply abandon the

practice. Its objective is to call the attention of true humanists

to the fact that they cannot use the methods of banking educa

tion in the pursuit of liberation, as they would only negate that

pursuit itself. Nor may a revolutionary society inherit these

methods from an oppressor society. The revolutionary society

which practises banking education is either misguided or mis

trustful of men. In either event, it is threatened by the spectre of

1 •

reaction.

Unfortunately, those who espouse the cause of liberation

are themselves surrounded and influenced by the c 1 i ma tew h ich

gene7atesTt:he banking conceptt and often do not perceive^its

I

true "significance or its dehuniariizing pQwer• Paradoxically,

!

r

I

I

.!

-■

Il ■

:■

-

i

i

t h e n, t hey utili^ this very instnjmentpjalienat ion in what they

consider an effort to liberate. Indeed; some ‘revolutionaries’

brand as innocents, dreamers, or even reactionaries those who

would challenge this educational practice. But one does not

liberate men by alienating them. Authentic liberation - the

process of humanization - is not another ‘deposit’ to be made

in men. Liberation is a praxis: the action and reflection of men

upon their world in order to transform it. Those truly com

mitted to the cause of liberation can accept neither the mechanis

tic concept of consciousness as an empty vessel to be filled, nor

the use of banking methods of domination (propaganda,

slogans - deposits) in the nameof liberation.

The truly committed must reject the banking concept in its

entirety, adopting instead a concept of men as conscious beings,

and consciousness as consciousness directed towards the world.

They must abandon the educational goal of deposit-making and

replace it with (he posing of the problems of men in their re

lations with the world. ‘ Problem-posing' education, responding

to the essence of consciousness - intentionality - rejects com

muniques and embodies communication. It epitomizes the

special characteristic of consciousness: being conscious oj\ not

only as intent on objects but as turned in upon itself in a

53

Ja-sperian ‘split’ - consciousness as consciousness of conscious

ness.

Liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of informat io:,. Jt is a learning situation in which the

cognizable object (far from being the end of the cognitive act)

intermediates the cognitive actors - teacher on the one hand and

students on the other. Accordingly, the practice of problem

posing education first of all demands a resolution of the teacher

student contradiction. Dialogical relations - indispensable to

the capacity of cognitive actors to cooperate in perceiving the

same cognizable object - are otherwise impossible.

Indeed, problem-posing education, breaking the vertical

patterns characteristic of banking education, can fulfill its

function of being the practice of freedom only if it can over

come the above contradiction. Through dialogue, .the teacherof-thc-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist

and a new term emerges: teacher-student with studentstcachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches^

but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who

'n their turn while being taught also teach. They become joindY

responsible for ajrocess in which all grow. In this process,

arguments based on ‘authority' arc no longer valid; in order to

function, authority must be on the side q/Trcedom, not against

it. Here, no one teaches another, nor is anyone self-taught. Men

(each each other, mediated by the world, by the cognizable

objects which in banking education arc ‘owned ’ by the teacher.

The banking concept (with its tendency to dichotomize

everything) distinguishes two stages in the action oftheeducator.

During the first, he cognizes a cognizable object while he pre

pares his lessons in his study or his laboratory; during the

second, he expounds to his students on that object. The students

arc not called upon to know, but to memorize the contents

narrated by the teacher. Nor do the students practise any act of

cognition, since the (fl>jccrTov.ard?TvMcirthat act should be

dirccled is the property ofdhc Reacher rather than a medium

evoking the, critical-rrJUr.tinn__Q£_Lp(h~~tcacher and students.

Hence in the name of the ‘ preservation ofculture and knowT”

ledge' we have a system which achieves neither true knowledge

nor true culture.

I

I

I

1

I

1

1

S

?

I

i

1

t

1

55

54

The problem-posing method does not dichotomize the

activity of the teacher-student: he is not ‘cognitive' at one point

and ‘narrative’ at another. He is always ‘cognitive’, whether

preparing a project or engaging in dialogue with the students.

He does not regard cognizable objects as his private property,

but as the object of reflection by himself and the students. In

this way, the problem-posing educator constantly re-lorm^his

reflections in the reflection of the students^ The students - no

longer docile listeners - are now critical co-;nvestigators in

dialogue with the teacher. The teacher presentsjhe material to

the students for their consideration, and re-examines his earlier

considerano.hs^dM.sludents express their own. The role o f the

' problem-posing educator is to erdate, together with the students,

the conditions under which knowledge at the icycl^of the doxay

is superseded by true knowledge* al the level of the logos)

Whereas banking educat ion anaesthetizes and inhibits creative

power, problem-posing education involves a constant unvc;hng

of reaIity. The former attempts tp maint.ai.n.1 he submersion af

consciousness; the latter strives for the emergence o! consciousness and critical intervention in reality.

'Studems, as t Key" are'increasingly faced with problems re

lating to themselves in the world and with the world, will feel

increasingly challenged and obliged to respond to that challenge.

Because they apprehend the challenge as interrelated to other

problems withmTnolafcorifext, not as a theorcdeal .question,

the resultmg^mprchTnsibn^tends to be increasmgly cridca! and

thus constantly "less" alienated^ Their response to the challenge

evokcs~nev7 challenges, followed by new understandings; and

gradually thestudents come to regard themselves as committed.

Education as the practice of freedom - as opposed to educa

tion as the practice of domination - denies that man is abstract,

isolated, independent, and unattached to the world; it also

denies that the world exists as a reality apart from men. Aullicn. tic reflect ion..CQ.n5 ide rs neither, abstract man nor the world

without~mcn? but men in their rHandrTs'wnii ghe WQ'r^^ Ihese

relations consciousness and world are simultaneous: conscious

ness neither precedes the world nor follows it. 'La conscience et

le monde sont dormes d'u/i meme coup: exterieur par essence d

la conscience, le monde est, par essence re lot if a elle', writes

1

Sartre. In one of our culture circles in Chile, the group was

discussing (based on a codification)3 the anthropological con

cept of culture. In the midst of the discussion, a peasant who by

banking standards was completely ignorant said: 'Now I see

that without man there is no world.’ When the educator re

sponded: ’Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that all the men

on earth were to die, but that the earth itself remained, together

with trees, birds, animals, rivers, seas, the stars ... wouldn’t all

this be a world?' ‘Oh no,’ the peasant replied emphatically.

‘There would be no one to say: “This is a world .

The peasant wished to express the idea that there would be

lacking the consciousness of the world which necessarily implies

the world of consciousness. ‘I’cannot exist without a‘not I’. In

turn, the ‘not L depends on that existence. The world which

brings consciousness into existence becomes the worldTTTKaf.

^nTciS^ngs'. Hence'thc previously cited affirmation of Sartre:

~L a consdTtce et le monde sont dormes d'un meme coup.'

As men, simultaneously reflecting on themselves and on the

world, increase the scope of their perception, they begin to

direct’ their observations towards previously inconspicuous

\

phenomena. Husserl writes:

In perception properly so-called, as an explicit awareness [Ge^/iren],

I am turned towards the object, to the paper, for instance. 1 appre

hend it as being tins here and now. The apprehension is a singling out,

every object having a background in experience. Around and about

the paper lie books, pencils, ink-well and so forth, and these in a

certain sense are also ‘perceived’, perceptually there, in the ‘field of

intuition’; but whilst I was turned towards the paper there was no

turning in their direction, nor any apprehending of them, not even

in a secondary wnse. They appeared and yet were not singled out,

were not posited on their own account. Every perception ol a thing

has such a zone of background intuitions or background awareness,

if ■ intuiting’ already includes the state of being turned towards, and

this also is a ‘conscious experience’, or more briefly a ‘consciousness

of’ all indeed that in point of fact lies in the co-perceived objective

background.

I

!

i

I

I

I

Thai which had existed objectively but had not been perceived

in its deeper implications (if indeed it was perceived at allU

3. See chapter 3. (Translator s note.'}

X

>

I

T>

f <"

5

!

I ■

I

i

5

56

begins to ‘stand out’, assuming the character of a problem and

therefore of challenge. Thus, men begin to single out elements

from their ‘background awarenesses’ and to reflect upon them.

These elements are now objects of men’s consideration, and, as

such, objects of their action and cognition.

Ill problem-posing education, men develop their power, to

perceive critically the way they exist in the world wjh

In whiditf\eyft iid tTemsdv^IIEcy-C.o me.t3-see.tbe..wo ddnoXas

iFstatic reality, but as_ajeality in process, in transformation.

Although the dialectical relations of men with the world exist

independently of how these relations are perceived (or whether

or not they are perceived at all), it is also true that the form of

action men adopt j££o jJ^rge_e^er^^

perceive themselves in the world. Hence, the teacher-student and

the stmder^teach^^ff^sim^HQ^QusTy^on^Jb^nselveFand

the” wo rid w i th ou t dichmomjz[ng t his refleetjony fro m _act ion,

a nd thus establish an authentic form of thought and act ion.

Once again, the two educational concepts and practices,

under analysis come into conflict. Banking education (for

obvious reasons) attempts, by mythicizing reality, to conceal

certain facts which explain the way men exist in the world;

problem-posing education sets itself the task of de-mythologizing. Banking education resists dialogue; problem-posing

education regards dialogue as indispensable to the act of cog

nition which unveils reality. Banking education treats students

as objects of assistance; problem-posing education makes them

critical thinkers. Banking education inhibits creativity and

domesticates (although it cannot completely destroy) the in

tent ionality of consciousness by isolating consciousness from the

world, thereby denying men their ontological and historical

vocation of becoming more fully human. Problem-posing

education bases itself on creativity and’stimulates (rue reflection

and action upon reality, (hereby responding^tojhe vocation of

men as beings who are authentic onjy when cngaged^inJnayiLy

and; creative transformation. In sum: banking theory and

p ract ice, as i mm o b i I izi ng and fi xa t i n g forces, fail to acknowledge

men as historical beings; problem-posing theory and practice

take man’s historicity as (heir starting point.

Problem-posing education affirms men as beings in the pro-

i

57

cess of becoming - as unfinished, uncompleted beings in and

with a likewise unhni: iicd realiiy. Indeed, in contrast to other

animals who are unfa.: .hed, but not historical, men know themselves to be unfinished; they arc aware of their incompleteness.

In this incompleteness and this awareness lie the very roots of

education as an exclusively human manifestation. The un

finished character of rr.cn and the transformational character of

reality necessitate that education be an ongoing activity.

Education is thus constantly remade in the praxis. In order

' to be. it must become. Its ‘duration’ (in the Bergsonian meaning

of the word) is found in the interplay of the opposites per

manence and change. The banking method emphasizes per

manence and becomes reactionary; problem-posing education

- which accepts neither a ‘well-behaved’ present nor a pre

determined future - roots itself in the dynamic present and

becomes revolutionary.

Problem-posing education is revolutionary futurity. Henceit is prophetic (and, as such, hopeful), and so corresponds to the

historical nature of man. Thus, it affirms men as beings who

transcend themselves, who move forward and look ahead, for

whom immobility represents a fatal threat, for whom looking at

the past must only be a means of understanding more clearly

what and who they arc so that they can more wisely build the

future. Hence, it identifies with the movement which engages

men as beings aware of their incompleteness - an historical

movement which has its point of departure, its subjects and its

objective.

The point of departure of the move men t lies in men themselveTTBuTsTncc men do not exist apart^ from_the world, apart

froni^reality^llic^jrioscinent must begin^with the men-world

re 1 a t io ns h i p. Acco rd i ng I y, t he po i n t o f departure m us t a ly^iys

Ik with nienjn the ‘here and now’, which constitutes the si.luation within which they arc submerged, from which they emergc,

aiidjji which they intervene. Only by starting frorn Uiis^imation

- which determines their perception of it — can they begin%to

nTo^JiLjdb-lhis...authentically they mus,t jyerce.ive their state

not its fiH.cd.and unalterable, but merely asJiniiting - and-therc_f< > rc challenging,___

Whereas the banking method directly or indirectly reinforces

I

I

II

1

!

1

1I

I

1

iI

I

I

I

I

I

i

|

!

A

I

a ) |?

(u.

1

I

»

I

*

pea^g^^i-

59

53

i•!

men’s fatalistic perception of their situation, the problem

posing method presents this very situation to (hern as a problem.

i

interests of (he oppressor No oppressive order could permit the

or magical perception v/hich produced their fatalism gives way

oppressed to begin to question: Why? While only a revolu

tionary society c?.n carry out this education in systematic terms,

the revolulionatj. leaders need not take full power before they

to perception which is able to perceive itself even as it perceives

can employ the method.

reality, and can thus be critically objective about (hat reality.

leaders cannot utilize the banking method as an interim measure,

As the situation becomes the object of their cognition, the naive

In the revolutionary process, the

A deepened consciousness of their situation, leads men to

justified on grounds of expediency, with the intention of later

apprehend that situation as an historical reality susceptible of

behaving in a genuinely revolutionary fashion. They must be

transformation. Resignation gives way to the drive for trans

revolutionary - that is to say, dialogical - from the outset.

formation and inquiry, over which

■

I

men feel themselves in

control. If men, as historical beings necessarily engaged with

other men in a movement of inquiry, did not control that move

ment, it would be (and is) a violation of men’s humanity. Any

situation in which some men prevent others from engaging in

the process of inquiry is one’ofxdolencc. The means used are not

1

important; to alienate men from their own decision-making is to

change them into objects.

This movement of inquiry must be directed towards humani

zation - man’s historical vocation. The pursuit of full humanity,

however, cannot be carried out in isolation or individualism,

but only in fellowship and solidarity; therefore it cannot unfold

in the antagonistic relations between oppressors and oppressed.

No one can be authentically human while he prevent others

from being so. The attempt to be more human, individualisti-

cally, leads to having more, egotistically: a form of dehumaniza

tion. Not that it is not fundamental to have in order to be

I

human. Precisely because it is necessary, some men's having

must not be allowed to constitute an obstacle to others' having,

to consolidate the power of the former to crush the latter.

Problem-posing education, as a humanist and liberating

praxis, posits as fundamental that men subjected to domination

i

must fight for (heir emancipation. To that end, it enables

teachers and students to become subjects of the educational

___ process by overcoming authoritarianism .and an alienating

intellectualism; it also enables men to overcome their false

I

I

I

Is

I

I

■g

i

f

perception of reality. The world - no longer something to be

I

described with deceptive words - becomes the object of that

transforming action by men which results in their humanization.

Problem-posing education docs not and cannot serve the

<

I

i i

.1

<

; Approaches to 1 rammg

I

> In tm years lime I may haveforgotten the content but I will remember the approach.

This section is directed mainly towards trainers. The section sets out four approaches

-to tramingandTearning, .with their characteristics

and their advantaged disadvan

________________________

. . ■ ,lg

all perspective for people who have training ■

tages. The purpose is to provide an over; „

x

responsibilities, and a rationale for the experience-based approach of this manual.

members also. If members "I

Course trainers may want to offer the material to course

’ ; it will add perspective to

become familiar with the approaches and their characteristics

understanding or us

their experience of their own course, and will increase their

l..

y;

methodology.

■ If

topic js offered to coe.e members, it is best dealt wrth after th ee 0^4 weeks,

by which time members will be able to relate jt to the.r own expe,ence ol Jte cow.

The information and ideas can be conveyed through a short presentation: do n|st g,ve a ■

continuous lecture (see page 158).

The short questionnaire Our Ideas about Training (page 163) can be used to opln up the j

.■7?

is light-hearted in style, but it will help members to g

. _i__ 4.mlp nf th^i trainer.

and the ro,e ortlWner

When we consider the education and training of adults as development workerjs\ we can

lit

four

identify four different approaches, each with advantages and disadvantages.. (The

_

approaches can be illustrated with a simple diagram which has two axes.'

The first axis has Theory as one extreme and Practice as the other. I he seconji axis has . |

»

Content as one extreme and Process as the other? The two axes produce tout

|

quadrants each representing an approach to training. Please refer to die diagram on die |

next page.

I

paI

1 Academic

<3

In the first quadrant which lies between Content and Theory, the approach can ■be|

ThJ .

4

described as ‘academic’. The main tool here is ‘teaching’. The purpose of academic^

teaching is to convey information and to pass on theoretical unders tan ling.

; I

characteristic method is the lecture, supported by individual reading and the writing of,J

■

I

'^3

■

I After Rolf P. Lynton and Udai Pareek. Training for Development, Taraporevala.

t

y\hat a group is^g

^~e. observe

*

observe ho v the group isS

working or discussing, we are focussing on the process.

1

156

I.

i i

1

1

I Approaches to Training

«T’V

SaysvThe goals are contained in a syllabus or curriculum. Appraisal is by means of

Jexafninations, usually written and competitive. The principal roles are lecturer or

er, and student or pupil.

I fth

Vfhc approach assumes that education is an intellectual process o; acquiring knowledge.

j|s|M'wledge-ia -to-be- passed-frorm those-who ‘know’ (the teachers), to those who xlorft

students), who are ‘ignorant’. A further assumption is that when students acquire

:§qiowlcdge they are then able to transform it into effective action in the ‘real world’.

'I I

■

giving attention

and importance to

Content

11 1

i'M i.

I

aJi Ii

Activity

Academic

•'vy

^giving attention

giving attention

and importance

to Practice

and importance

to Theory

giving attention

and importance to

Process

The formal education systems, with their schools and universities, fall in this quadrant.

These systems are usually individualistic and competitive. Authority and responsibility

for the learning process and for appraisal lies mainly with the teachers and lecturers.

The approach is attractive to teachers and lecturers because it ensures they have higher

T status? Furthermore, the process of teaching is predictable, and normally remains

f within the teachers’ control.

■ The approach is useful for disseminating information and strengthening theoretical

• thinking. But on its own it may not lead to .better professional’practice or more

,• effective development work. Too many practising workers attend academic courses,

■ listen to lectures, acquire a lot of information, pass exams, and gain qualifications —

■ and then carry on working as before, without any improvement in effectiveness or in

the quality of their work. The links between academic learning-and practice are weak.

■■ Practitioners need an approach to training which emphasizes change in practice.

r

Iw

Action-Reflection

Laboratory

.

J'f

3. There are parallels in development work: the worker who 'knows', the 'villagers’ who do not know, and the top-down

one-way communication.

157

I

'n

■rt

§I

1I

I

II

' ji

I

h.'.

The principal academic method, the lecture, is also inefficient. If a lecture goes on,

without a break, for more than 20 minutes (as most do) it is said that students carry

away only 40% of what they have heard and half of that has been forgotten one week

later. Confucius is supposed to have said, What we hear, we forget.’

■

“t

ti

H Activity

! ft

•gj

The second quadrant lies between Content and Practice. This approach can be called

‘activity’. Its purpose is to teach and improve practical skills. This is the kind of learning

__ __

often found in traditional societies.

Those who have acquired skills from their elders in a previous generation ‘pass them

>n. An obvious example is children who learn adult roles and

down’ to the next generation.

Ld grandparents. Anomer

Another is the

me young person learning a bimi

sldll

skills from their parents and

craft from an older practitioner

who

has

the

required

expertise

and

experience.

:actitioner

who

has

the

required

expertise

and

experience.

or

lies are. «-V»o

the apprentice, tliA

the nr»^rirp

novice, rbp

the intprn

intern, nnd

and the

the dl^Cinle.

disciple.

Typical learning roles

the

‘

master

’

,

the

demonstrator,

the

instructor,

and

the

expert.

The

Teaching roles are t

methods include observation, instruction, copying, and practice under supervision.

1

. *

*

.

.a

i

i'll •“

f* •

A •^T ft Cl

IA

Training-on-the-job, field placements, coaching, secondment and counterparts are

refinements of such methods.

-■&

■

i

aj

f

x

> gL'

y-'" ‘

: J

V

B||gf

IB

Confucius is supposed to have said, What we see, we remember.’ The approach leads

to the learning of whatever skills, procedures and expertise have been expounded or ■I

Remonstrated, but it may not go further. It assumes that whatever apprentices have

1 ihvB?.

tire regul:

regular demands of the .]

seen or been told will enable them to) deal, not only with rhe

job, but also with unfamiliar and unexj:pected challenges. But those who follow and rely A

•I IS

qn regular and routine procedures may find they lack the theoretical understanding or

the insight to deal with situations outside their previous experience. And many of the2

situations we encounter in development work will be outside our previous experience. |

It has been said that practice without theory is blind.

• . I ii

I'flt

1

i

<■

- Despite its limitations ‘activity’ is long established and widely rec(:ognized as the

simplest way to train the staff of organizations. Much of the training conducted by

yoluntary development agencies and NGOs follows this approach. One advantage is

that it is cheap. Another is that it does not require’any specialized training facilities or

^taff.

tylany development workers have been inducted into their work through ‘reading the | ! wir

flies’, or ‘sitting with colleague X’, or ‘going on visits with Y’, or ‘seeing how Z does

the work’. Such induction may allow the newcomer to ‘get the feel’ of the job and get

started; but later he or she will be faced by new and greater demands, and may end up

by resorting to trial and error methods and repeating the past mistakes of others.

Some training courses combine the academic with activity, so that

t— the two

—

approaches then complement and inform each other.

I

!

I

158

S.w

11'

■■

6.1 Abproachet to Training

i

H 'fhe third approach emphasizes Process and Theory, and is known as ‘laboratory’

; ^training. This is represented in die third quadrant of the diagram.

I

f''

'• - -

J' | Laboratory

■

. ..The name laboratory is used because there are parallels with the working of a scientific

'^laboratory. One parallel is the experimental nature of what takes place. Individuals or

t 'groups try tilings out and observe what happens. For example, they may take new

brisks, express hidden feelings, practise new roles, experiment with new behaviour, and

explore how they are relating to others and how others perceive them. Another

parallel with a laboratory is the separation of the work from the rest of the world.

Attention can then be concentrated on the task or process under study, and what is

’.not relevant can be left ‘outside’. This makes it easier to focus on particular factors,

l^trace their effects, and draw conclusions.

^..Another name which is sometimes used is ‘unstructured’.

P;i

I

-• The approach is essentially person-centred and group-based. The task of the group is

"to. observe and study the way the group is functioning while this is actually happen'■ ing. The task of the individual is to examine his or her own behaviour and personal

role within the group, and the impact that he/she is having on others, again while

'.actually engaged with the group. Attention is therelore on the present moment. This

a; .

wS'lji

is often referred to as ‘working in the here and now’.

The reference points, and the data for study, come from within the group itself.

Outside forces, back home situations, and formal designations are all left outside the

‘laboratory’. There is little or no external accountability. The learning is the concep

tual understanding and insight which comes from this experience, together with

increased self-awareness, improved sensitivity, and enhanced skills in relating to

• r.

I

S'

others.

• The role of the trainer, typically called a facilitator here, is to help members to focus

on the way the group is working, and on the issues facing the group. He/she also

’ helps individuals and the group to examine and understand experiences within the

group. The ‘methods’ include group dynamics, sensitivity training, personal growth

laboratory, T-groups, community change laboratory, and group relations conferences.

■ji-'

If the focus is mainly on the working of the group, rather than on individuals, then

the dynamics of participation, decision-making, leadership, power, authority and

conflict are all likely to be examined, along with other dimensions. These are all central

issues in any organizational or community setting, and development workers need, not

only to recognize them, but be able to work with them.

If the focus is mainly on individuals within the group then the members become, more

aware of themselves and how they are perceived by others, understand more about

1

>

159

Ih

also centrahin development work.

The approach assumes that a person’s inner psychological realities are relevant to

learning and to their work in die outer world. It makes more explicit the link betwe^i

the assumptions, aspirations, values, etc of die inner world, and the roles, dcasiom

making, leadership, and action of the outer world. It also assumes

".nit

4«e»ee

'»» "™

tag » te

at P^0P

‘

°f '“■'kl"S

when they return home.

’ The learning has a deep and lasting quality, which is often personal to the learner,

o«

■'^

1

H-4

he

s^-.l 'th!

mdivrdual who joins such a training group may be expected to disclose mom o

him/herself, and to receive more feedback, than in other approaches. Feehngs are

often exposed. The experience can be exciting and challenging; it may also have

disturbing and even painful moments. Some people say that if learning is to be effective

1

li

it should disturb us!

handle effectively, and requires trained facilitators.

ig

Such training can be difficult to

■

,

------—

gS

Teachers and trainers who are used to a morei conventional academic approach may

■ I,

.predictable

and

complex.

find this approach open-ended, unj

.ally offered to those who want to increase their own

.This kind of training is usui

own skills. It is particularly helpful in situations and

awareness and improve their

are systemic disparities in power, such as community and ||g

professions where there

and youth work, prison and probation services, and managedevelopment work, social

Many develonment workers who have experienced such training have gained ||

ment. Many development workers who have ex[

«eatlv improved the quality of their work with others

others. It

important insights and have gready

Sa

.

___

. .

is especially useful for those with responsibility for training.

i|

wt

lvJf

I®

III Action-Reflection

,iaisiaata:iKa!m!lil^^

,

Finally there is the quadrant which lies between Process and Action. Training here |||

consists mainly of providing course members with alternating opportunities for action

and reflection’. They experience an action, and then they reflect on it. They work at a tas -

|| |

|, j

which is related to some aspect of development work, and then they flunk about the g ;•

process. What happened? How did it happen? Why did it happen? How is it relevant.

4

1

P Rj

IM

w

w

The approach is also referred to as experience-based or experiential. Learning arises ||

w%

from the direct experience of the course member, but that experience has to be g

f'l

analyzed. Simply doing something is not enough. We need to look at ourselves in e

process of doing it. Experience that is not analyzed and reflected, upon is like food ,|g

we eat but which passes through our system undigested — it does us no good.

!

T(. •; ‘IT” ’

'

The basic tool for the approach is alternations which reinforce learning. Action is

followed by reflection, group events alternate with individual work, personal invo ve- J||

160

“CBi

I !

1I

'W-T'r':/’-

i

o

’ ---- ----------6^ I Approaches to Training

»ent alternates with impersonal analysis and input. We move

fcthe general. We do something and then talk about it between the specific

•lt tice2C

t0 bUild UP tbeOry- 8nd und«3tand th. and vice versa. We

eery by putting it into