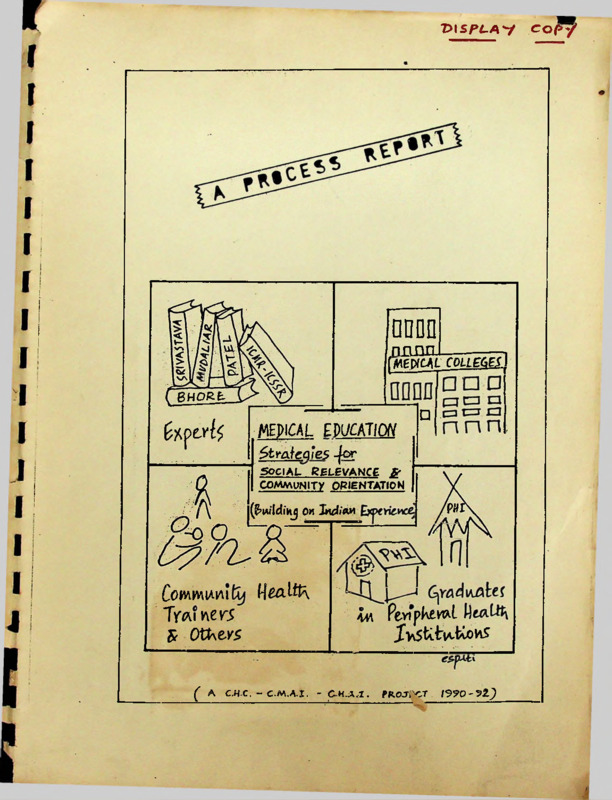

STRATEGIES FOR SOCIAL RELEVANCE

Item

- Title

- STRATEGIES FOR SOCIAL RELEVANCE

- extracted text

-

DISPLAY

□ODD

nnnnJ—------

(MEpfC^L COLLET

8HOR.E

□

WPICAL EDUCATION

faycrt$

Strategies -fa?

"1 SOCIAL RELEVANCE &

COMMUNITY ORIENTATION

(^wldihj On Ja^Iiah

Commiavu

Twiners

& Otke^

( A

^/PW

I

Health

I

w Pwpkzwi

iv^KtwUonS

C.H C. - C.M.A.I. - C H.A.t.

PROJT<T

l9?O-9±9

Cop/

CHC / MEP / 01

Research Project

Strategies for Social Relevance and

Community Orientation in Medical

Education : Building on the Indian

Experience

A PROCESS REPORT

Community Health Cell, Bangalore *

JUNE 1992

Sponsored by : Christian Medical Association of India (CMAI)

Catholic Hospital Association of India (CHAI), Christian

Medical College, Ludhiana (CMC-L),

*Society for Community Health Awareness, Research and Action

No. 326, V Main, I Block, Koramangala, Bangalore - 560 034.

MEDICAL EDUCATION PROJECT 1990-92

June 1992

A PROCESS REPORT

CONTENTS

I. Title

Page

II. Research team and 'supports'

A. Preamble

a) Medical Education reform

b) Some lacunae in the process

1

2

c) Disturbing trends (Diagram A)

3

B. Origins and Scope of the study and its linkages

a) Researchers

b) Sponsors

5

5

c) Other Linkages

d) Scope of Study

5

7

C. Basic premise of the Study

a) Recognising four sectors of innovation

8

b) Need fcr dialogue among sectors

9

c) Faculty development - a neglected issue

9

D. Evolving the objectives

a) The steps in the process

11

b) The original objectives

11

c) The 'Interactive response'

13

d) The Final Objectives

15

E. Methodology

1. Literature Review

16

2. Letters to Medical Colleges

17

3. Letters to Community Health/Development

Trainers

18

4. Survey of graduates with rural experience

19

5. Institutional visits

6. Meetings and Interactive Dialogue

19

21

7. Approaches - Orthodox and Interactive

22

2

2

F. Organisational Dynamics

a) The Research Team

24

b) The Advisory Group

25

c) Peer Group support

25

d) Project time and Process Schedule

28

e) Financial Support

29

G. Responses - Results - Findings

a) Literature Review

b) Medical College survey

30

31

c) Alternative Training Sector - Review

d) Survey of Graduates with PHC experience

41

45

e) Some overall general observations

49

H. The Project Process and outputs

a) Interaction with Individual colleges

54

b) Community Health Trainers Dialogue I and II

57

c) Participation in CMC Network

d) Concurrent Publication - Stimulus for Change

58

59

e) Final Publication

61

f) Towards a collective commitment-Medical Educators

Review Meeting, June 1992

63

I. Challenges for the Future

i) Factors promoting change

65

ii) Obstacles / Barriers to change

67

iii) Task for the future

69

J. SO WHAT - A reflection on the study

I

J

i) Strengths

71

ii) Weaknesses

71

K. In Conclusion

74

L. Acknowledgements

76

M. Reading List (will be prepared at the end of the

manuscript finalisation)

79

LIST

OF

TABLES

Page

I.

II.

Initiatives of the Researchers which

formed the background to the study

6

Graduate Survey Components

20

III. Research Approaches in Study

IV.

V.

VI.

23

Medical College Survey - Respondents

Statewise distribution and source

32

Medical College Strategies - Objectives

and curriculum structure

33

Medical College Strategies - Pre-clinical

Phase

34

VII. Medical College Strategies - Para-Clinical

Phase including Community Medicine

Teaching

Medical

VIII.

34

College Strategies - Clinical Phase 35

Medical College Strategies - Internship

Phase

36

X.

Pace Setter Colleges - Some Features

38

XI.

Pace Setter Colleges - Key Innovative

Strategies

39

IX.

XII. Alternative Training Sector

42

XIII. Alternative Training Sector - Key Ideas

44

XIV.

XV.

XVI.

Graduate Survey I - Skill development/

competence areas

47

Graduate Survey II - Curriculum Structure/

Framework

48

CMC Network Meeting - Areas of Discussions

58

LIST OF DIAGRAMS

A.

Disturbing Trends in Medical Education

4A

B.

Sectors of Innovation/ 'ontribution of

Sectors / The Need for Integration

8A

C.

Medical Colleges and Community Health

Trainers included in Study - a regional

distribution

45

LIST

OF

APPENDICES

A .

CHC-CMAI-CHAI-CMC Network-Project Linkages

1

A2.

CHC-CMAI Project Contract

6

B.

Resource Persons to whom initial project proposal sent

7

C.

Project Announcements in bulletins/journals/press

8

Dj.

Letter to Medical Colleges

9

D2»

Letter to Medical Colleges - II Reminder

10

E.

List of Medical Colleges contacted/responded

12

F.

Letter to IAAME Conference Participants

17

G.

Letter to Corrnnunity Health and Development Trainers

20

H.

List of Community Health and Development Trainers

contacted/responded

23

A. Salient Features of Institutional Visits

24

B. Meetings Linked to Project

25

J.

Medical Colleges included in Project Report

26

K.

Medical College initiatives with college code

28

L.

Project Schedule I

35

ScN.

M.

An overview of financial support for the project

40 & 41

0.

Reports / Publications from Medical Education Project

42

P.

mfc Anthology Handout, 1991

45

G.

Framework of Medical College based workshop on

project determined instruments

46

R.

Health Action Special Issue - June 1991

49

S.

Preliminary Communications from project at IAAME

Annual Conference in Bombay - January 1991 (Abstracts)

50

I.

I

A.

a)

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

PREAMBLE

Medical Education Reform

Medical Education and its social and community orientation have

been a subject for discussion and dialogue in India especially

since the Bhore Committee Report of 1946. During the last four

decades there has been much rhetoric and many exhortations; a

few concerted attempts by keen medical educators and institu

tions; some progressive recommendations by the Medical Council

of India ( 1 ) and other professional bodies, but little overall

change.

The Srivastava report in 1974 ( 2 ) sums up the problem and the

challenge very effectively when it states :

"Diagnosis of the Problem"

"The stranglehold of the inherited system of medical

education,

the exclusive orientation towards the teaching

hospital,

the irrelevance of the training to the health needs

of the community,

the increasing trend towards specialization and

acquisition of postgraduate degrees,

the lack of incentives and adequate recognition for

work within rural communities

and the attractions of the export market for medical

manpower

are some of the factors which can be identified as

being responsible for the present day aloofness of

medicine from the basic health needs of the people....

"The Challenge Ahead"

The greatest challenge to medical education in our

country is to design a system that is deeply rooted to

the scientific method and yet is profoundly influenced

by the local health problems and by the social, cul

tural and economic settings in which they arise......

We need to train physicians in whom an interest is

generated to work in the community and who have the

qualities for functioning in the community in an

effective manner".

2

2.

The last fifteen years, since the Srivastava Report have

however witnessed a growing spirit of introspection and an

increasing commitment towards serious reorientation of the

curriculum, to suit our own 'needs’ and 'socio-cultural

realities'.

The period since 1975 has been marked by significant develop

ments, of relevance to Medical Education.

At the national level, there have been the National Health

Policy and National Education Policy statements, the opera

tionalization of the Reorientation of Medical Education

(R.O.M.E.) Scheme, the 1982 Recommendations of the Medical

Council of India, and the development of the Health University

concept (3 ).

Within the medical colleges, there have been serious efforts

by a few to evolve community oriented training strategies

based on the MCI guidelines and sometimes going beyond it, but

within the overall stipulated "structure' and framework of

orthodox medical education that has been historically evolved

and is well entrenched. Their efforts have been interesting

but of limited impact due to many factors including inadequate

faculty response and the changing social/value ethos of the

medical college entrants. The absence of the concept of

'autonomy' in the medical education sector in the country,

preventing the development of experimental alternative curri

cula

is also an important factor.

Some medical colleges have been involved in networking around

various new directions including ’epidemiological orientation1,

the ‘alternative *

track concept, and the 'decision based app

roaches to evaluation/innovation' (3 ), Many have been par

ticipating in the annual deliberations of the Indian Association

for the Advancement of Medical Education. The efforts of the

National Teacher Training Centres for medical college teachers

in Pondicherry and PGI-Chandigarh have also been significant (9 ).

Outside the medical college sector, there has been experimenta

tion and reflections on alternatives. Key among these are, the

'Kottayam experiment' ( 6 ), the medico friend circle's 'Antho

logy of ideas' for an alternative (5 ), the JNU plea for a ’New

Public Health' (7 ), the Miraj Manifesto ( 8 ) and others ( 9 ).

A number of innovative community health oriented training pro

grammes for health personnel especially within the voluntary

sector have also developed and are of significance to Medical

and Nursing Education, even though they have evolved in a

separate 'universe'. Similarly outside the health sector, in

the development and informal education sectors there have

emerged a number of 'alternative training' experiments that

have pedagogical innovations relevant to medical education (10).

b) Some Lacunae in the Process

While there is much evidence therefore of the new spirit of

/

-3

3.

introspection and ‘innovation’, which could stimulate change

in the 1990s there are some features of these developments

that are not so healthy and could be considered lacunae

and even going counter to the emerging process. (11)

Firstly, there is not much interaction or dialogue between the

compartmentalised universe of government health services and

training centres, medical colleges - government and private

and voluntary7 agencies and other groups interested in alterna

tive medical education. Even within these compartments there

are divisions and inadequate networking. Groups are therefore

unaware of each others' efforts.

Secondly, there has been inadequate publication of the strengths

and weaknesses of these different initiatives. Even though

there is a growing mass of ‘grey literature’ - reports and

handouts and circulated papers, these are not accessible to

the 'serious' medical educators in India, who are therefore

not aware of the wealth of experience in the country itself.

Thirdly, the innovators within and without the system have not

subjected their own 'innovations' or 'reflections' to any type

of 'objective evaluation' or 'peer group assessment'. In some

instances, where this has been attempted, the results are not

available, fcr others to learn and reflect upon.

Fourthly, in the absence of this awareness of the diversity and

multifaceted experience in the country, there is a tendency

among medical educators to be carried away by 'ideas' and

'expert advice' that have originated in other countries - in

situations of different socio-economic-cultural conditions and

different educational systems. Some of the recommendations and

suggestions are therefore not adequately grounded in local rea

lities and experience.

Fifthly, there has been inadequate attention given to the tradi

tional systems of medicine and healing as well as the prevalent

health culture and folk health practices.

Finally, whatever the focus and orientation of existing medical

education - there are a growing number of young graduates who

have opted for work experience and work commitment to peripheral

health care institutions including those in remote rural and

tribal areas. This is most often without adequate preparation

in their education. Notwithstanding all the rhetoric in recent

years about Primary Health Care little or no effort has been

made to elicit feedback from these pioneers on what could be the

framework of a more relevant education geared to the professional

and emotional challenges.

c)

Disturbing Trends

Simultaneously, the 1980s have also seen the emergence of a large

number of disturbing trends in medical education and health ser

vices development in the country which may have far reaching

,

4

consequences on the concept of social/community orientation of

medical education ( 9 ) .

These include :

i) the growth of capitation fees colleges,

ii) the mushrooming of institutions based on caste and

communal affiliations,

iii) the privatization of health care,

iv) the mushrooming of private high technology diagnostic

centres and the concurrent glorification of high tech

nology through high pressure advertising in the media,

v) the unresolved and probably increasing problem of private

practice among full time teachers of medical colleges,

vi) the increasing ’doctor-drug producer axis' with ’vested

interest in the abundance of ill health1,

vii) the rampant corruption that seems to be accepted as

routine practice and the erosion of norms of medical

ethics without any debate,

viii)

the preoccupation of medical educators with illness care

and the disregard for 'medical education for health".

Taken together they are beginning to have 'an insiduous but

definitive effect on the focus end orientation of health service

development in the country as well as the nature of the manpower

education' investment of the state'. (See Diagram A)

t

5.

B.

ORIGINS AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY AND ITS LINKAGES

ORIGINS

The study arose out of an interaction between different groups,

each one with its own particular interest in health human power

education in general and 'medical education' in particular.

a)

The Researchers

The project coordinators had a long history of interest in

'appropriate medical education' arising out of internship

experiences in a Bangladesh refugee camp (1971) and Andhra

Cyclone Disaster relief camp (1977). The experiences of

'medical care in conditions of acute mass poverty' and

'disaster linked environmental realities' led to a process of

reflection on the relevance of large, high technology, teaching

hospital oriented medical education in preparing doctors for

the challenges of Primary Health Care. This interest led to a

decade of involvement with the community orientation of medical

education in a socially relevant medical college (St. John's,

Bangalore) in South India followed by the development of a

'grassroots' technical resources centre (CHC) to promote

community health action through voluntary effort in South India.

During these years there were many opportunities and initiatives

to reflect on 'appropriate medical education' as outlined in

■ Table I. It was these varied experiences, that led to the

evolution of the project so that the researchers could build on

all the past efforts.

b)

The Sponsors

The sponsors of the study - The Christian Medical Association

of India (CMAI) and The Catholic Hospital Association of India

(CHAI) are membership associations in the voluntary sector which

together network over 2,500 institutions in the country. By

virtue of their commitment to health care particularly focussed

on the 'marginalised and underprivileged' they are interested

greatly in all efforts to produce

more 'socially relevant' and

'community oriented' health professionals in the country. They

were therefore eager to associate and support the project as

soon as it evolved and they were contacted for support. The

detailed background to the evolution of this linkage is outlined

in Appendix A^ and A^.

c)

Other Linkages

The facilitation of the first network meeting of the four Chris

tian Medical Colleges by the CMAI and the invitation to CHC to

provide the 'keynote stimulus' led to an establishment of an

informal linkage between the researchers, the sponsors and the

four medical colleges of the CMC Network, who were all intere

sted in community oriented and community based education and

therefore agreed to participate as an ’interactive peer group' ,

in the evolving study (See Appendix Ap. These colleges, who /

6

I

6.

/

tabu

INITIATIVES

FORMED

OF

THE

THE

i

RESEARCHER’S WHICH

BACKGROUND

TO

THE

,

( 12 )

STUDY

YEAR

INITIATIVE

1972

Refugee Camp Experience

Making Medical Education

Relevant to the needs of

Society - Interns reflections

1973

DTPH Dissertation

Training Doctors for Community

Health Service (Trends in

Undergraduate Medical Education

in India)

1973-83

Community Orientation

of Medical Education

- SJMC, Bangalore

(various experiments)

Moving beyond the Teaching

Hospital

1977

MD - Term Project

(Interactive Evaluation)

The Kottayam Experiment :

Training Programme for

Community Nurses / Health

Supervisors

1982

Year of Travel and

Reflection with Commu

nity Health Action

initiators at the

Grassroots

Notes on a year of Travel and

Reflection in the context of

Social Orientation of Medical

College Educational Experi

mentation

1984

mfc Annual Meeting on

Medical Education Calcutta

Background paper (150 years

of Medical Education :

Rhetoric and Relevance)

Workshop for Rural

Bond Scheme Pioneers

(SJMC/CHAI/CHC)

Report of a Workshop for Rural

Bond Scheme Pioneers

1988

CHC Network - Sub

Committee on Medical

Education

Memorandum to the Health

University Committee of the

Karnataka Government

1989

Supportive stimulus to

Network of Christian

Medical Colleges

Keynote Address : Towards

Greater Social Relevance

Facilitation of first

dialogue of Community

Health Trainers in

India (VHAI)

Report on Proceedings of the

Trainers Dialogue

mfc Anthology - Medical

Education Re-Examined

(Planning Collective

Process)

3 Articles in Anthology inclu

ding Anthology of Ideas Alternative Framework of a

Curriculum (Compilation)

1990-91

PUBLICATIQK/REPORT

. .7

7.

/

were, already involved in innovations/experiments of various

types were interested to hear of the wide ranging efforts in

the 'keynote address' and evinced further interest in the

compilation of Indian experience.

d)

Scope

X.

The present study emerged through an interaction between the

three groups mentioned above, and the scope of the study evolved

as an attempt to explore and document all the 'innovations' and

relevant reflections in India so that a Researched Review Document

would be compiled, which would be practical, relevant, and use to

all those, who wish to explore medical education reform in the

1990's, building on the wealth of Indian experience.

Focussed primarily on the Indian experience and basing itself on

an interactive process which would be multipronged - including

literature review, individual and group discussions, field visits,

questionnaire surveys and other orthodox and alternative appro

aches the project study sought to put together

"a handy reference manual of local innovation,

an anthology of ideas emerging from local experience,

and a resource directory of local Indian expertise"

in community oriented and socially relevant medical

education and health training in India. (11)

After much deliberation the project researchers decided that the

key target group of the project would be "faculty of medicad.

colleges' who in 'groups' wish to reflect and experiment with

alternative/relevant ideas.

Other target groups were also identified during the process and

it was decided that as a 'lobbying for change' process a summary

document of the key findings and conclusions of the study would

also be sent to them as a complementary process in the follow up

of the project.

The researchers and the CHC team had already good contact and

linkages with the 'alternative training sector' and the 'young

graduates in rural centres' due to the nature of CHC work in

past years and this 'network' of linkages was used with great

advantage, for the evolving project.

8.

C.

BASIC

PREMISE

OF

THE

STUDY

The basic premises of this interactive study were that

Recognising Sectors of Innovation

a") There are atleast four sectors of innovation from which stimulus

for reforms in medical education can and have emerged (13 ).

i) The Expert Sector

Starting from the Bhore Committee Report of 1946 till

the recently circulated draft outline of the National

Education Policy for Health Sciences (Bajaj Report 1989) there have been a series of expert committees

in India offering ideas and recommendations of great

relevance to the Indian Situation.

ii) The Medical College Sector

A few medical colleges have made serious efforts to

operationalise some of the expert 'ideas' and reco

mmendations and some have gone further to evolve their

own community oriented training strategies. Much of

this reform is within the framework of 'structure' and

'function' stipulated by MCI.

The 'medical college' sector includes ideas and reco

mmendations put forward by professional associations

at their annual meetings and also covers much of the

materials that has been regularly presented and dis

cussed at the annual meetings of the IAAME.

The 'Expert Sector' and the 'Medical College Sector'

would together constitute what we would like to term

as 'traditional/orthodox expertise '. (Diagram B^ )

iii) *

'Voluntary

Training Sector

Since the 1970's a large number of innovative community

health oriented training programmes for health humanpo

wer has developed especially within the so called

voluntary sector. Many are geared to training or reo

rienting doctors and nurses (produced by the orthodox

system) towards community health oriented work. Many

others train 'lay people' (non-doctor, non-nurse) in

community health work. A large number of 'alternative

training experiments' supplementing these efforts have

also emerged in the development and informal education

sector. While these may appear to have developed in

a 'separate universe' there is growing recognition that

their approaches and methods have great significance

for professional humanpower education in the country (10).

9

DIAGRAM

DIAGRAM

B

CONTRIBUTION

OF SECTORS

m

BBB

|£xPER7S

COMMUNITY

HEALTH

ALTERNATIVE!

MEDICAL

education

EXPERIMENTAL

Parallel

CUR£f CUL.UM

TRAINEES S'

OTHERS

DIAGRAM

GRADUATES

IN

iv) The *

PHC

graduate1 Sector

There are a large number of young graduates of the

existing orthodox medical education system who have

worked in small peripheral rural hospitals, primary

health centres and community health projects and have

had to creatively adapt their own inadequate education

to the 'professional challenges' and 'emotional dema

nds' of community oriented health care. Most of these

'creative tensions' and 'appropriate responses' and

ideas are waiting to be systematically tapped and

explored.

The 'Voluntary training sector' and the 'PHC graduate

sector' would together constitute, what we would like

to term as the ’alternative

*

expertise. (Diagram

)

b) Heed for Dialogue Among Sectors

The second premise of our 'interactive study1 was that while the

above sectors of 'innovation' have, separately and taken together

a lot of interesting ideas to offer to all of us who seek to

reform medical education, there is inadequate documentation and

reporting and inadequate networking and hence this expertise

lies relatively unknown within sectors and between sectors.

Medical college based innovators know little of what each other

aredoing; the voluntary sector trainers have little dialogue

even among themselves; the graduates in the periphery are seldom

contacted for feedback; and therefore there is a 'gross' lack

of awareness of the wealth of experience available in the country

itself. Unless all these ideas, suggestions, experiments and

innovations are available together in some sort of compilation/

publication there is little chance of a cross fertilization of

ideas and for dialogue between the innovators and the enthusiasts

of all the sectors. It is now more than clear that any form of

alternative medical education or experimental parallel curriculum

can emerge only if attempts are made to bring the traditional

orthodox expertise to dialogue with alternative expertise and

evolve an integrated strategy and response to the challenges of

Appropriate Medical Education. (Diagram B^ )

c) Faculty Development - A Neglected Issue

The third premise of our study, which has therefore greatly

determined its focus and scope, particularly in the context of

the 'end products' is that the 'Faculty' of a medical college

are ’the Key to Change’ and that faculty development has been

the single biggest casualty in the Indian Medical Education

Scene. There has been a lot of rhetoric and some lip service

to faculty development but faculty development and training is

at the bottom of the priority list of medical college leadership.

Teaching in a medical college is still not considered an inde

pendent and important enough 'vocation' and tends to be still

relegated to a sort of 'appendage' skill or at best an unavoi

dable task.

>

10

I

10.

If reform in the 1990's has to have relevance, rigour and

collective commitment, then developing a core group of faculty

in every medical college committed professionally to medical

education is an urgent necessity and this study is primarily

oriented to that task.

We have tried to build some 'structure' and a framework towa

rds this 'faculty development process'. The availability of

faculty role models in the institution are crucial for inspiring

students towards more community oriented and socially relevant

vocations in medicine. This task can no longer be ignored.

Cal] it by v.’!:atever name, the need is for a

new treed of physician, who has a broad under

standing of human biology, who is imbued with

the ingredients of rural and peri-urban soci

eties ar.- their way of life, who can communi

cate effectively with the rstient's family

regarding t'r/ nature of the ailment, who car.

address himself to preventive aspects in the

hemes, who will be ar. effective leader of

health workers, and who will use his knowledge

to stimulate other community building programmes.

We need in effect, a social biologist.

Mass

public health and hospital patient care, however

well developed, cannot fill this gap.

Ramal ingaswarr.i,

1968

. .11

11.

'

a)

D.

EVOLVING

THE

OBJECTIVES

\

The Steps in the Process

The objectives of the study based on the premises described in

(C) evolved through an interactive process which consisted of

4 steps.

Step I

A project proposal was drafted in January 1990 and circulated

to the Advisory Committee, Peer group and a group of key

resource persons in the country.

(Appendix B)

Step II

Many ideas, reactions, modifications were suggested by some of

these resource persons and were considered by the researchers.

Step III

At the first meeting of the Advisory Committee in May 1990 all

these suggestions were considered and discussed. A modified

set of objectives, keeping in mind the existing limitations and

constraints available, especially of time framework were evolved.

Step IV

As the project evolved and the field visits and interactions

took place and feedback from respondents and peers came in some

of these objectives got further modified in terms of focus,

priority and significance. This symbolised the interactive

aspect of the action-research.

b)

The Original Objectives

The following were the objectives listed out in the first project

proposal circulated in January 1990 :

I. General Objectives

1. To Document and Review

a. Innovative and alternative experiments in medical

education in India since the 1950s.

b. Alternative Community Health training programmes

in the voluntary health sector.

c. Relevant alternative educational strategies in the

non-health sector.

.

in the context of social relevance and community orient- /

ation of medical education.

/

12

12.

2. To evolve a handy 'resource' book

and some tentative guidelines for social relevance and

community orientation in Medical Education, out of this

cumulative experience, the focus being primarily on

medical educators.

II. Specific Objectives

1. To document descriptively/analytically the recommendations/

key experiments / innovations and 'experiences' in appro

priate medical education in India since the 1950's

(Appendix A).

2. To review the key alternative 'training experiments' in

the 'Health and Non-Health' sectors in India, to determine

issues, perspectives, ideas and 'pedagogical innovation'

relevant to 'appropriate medical education

*

in India.

3. To build an 'Anthology of Ideas' from suggested changes/

reforms/reorientation in Medical Education from

a. a sample of medical graduates who have worked in

peripheral rural hospitals and community health

projects since the 1980's.

b. a sample of Community health project innovators and

community health trainers.

c. innovative medical educators.

4. To evolve a set of exploratory guidelines for curriculum

reorientation within the existing MCI recommendations

based on the above 'reviews' and discussions.

5. To formulate a curriculum outline for a year's pre-selec

tion foundation course for potential medical students

which is being contemplated by some medica colleges

basing the community health orientation and sensitization

strategies primarily on educational experiments in the

health and non-health sectors.

(The main goals of such

a course as envisaged at present is intensive community

health orientation and foundation as well as language and

learning skills, necessary for successful medical education

through a reoriented curriculum).

6. To prepare an annotated bibliography/resources inventory

of key books/papers/reports/manuals/studies/pedagogical

innovation and educational aids evolved from the Indian

experience and relevant to 'Appropriate Medical Education'.

7. To supplement the above objectives by the following

additional sub-objectives (if time permits)

a. A short review of Medical Education in Ancient and

Medieval India (Ayurvedic and Unani traditions) to

explore our own cultural roots and identify some

lessons from history.

13

13

b. A pilot survey of student 'ideals' and 'expectations'

in medical education.

c. A pilot survey of 'key policy makers' and 'medical

college administrators' for determining needs, requi

rements and organisational dynamics for pursuing

appropriate Medical Education.

d. A brief overview of 'ideas' and innovative programmes

emerging the world over in order to locate the Indian

experience in a global context.

Ill. The 'interactive response'

The interactive process was quite fruitful. The key ideas/

questions and suggestions that were offered by many peers

who received the first draft proposal were :

a. Whether such an exhaustive review would produce the

results commensurate with the efforts?

b. For whom will the resource book be? Medical Educators?

or policy makers? A focus may be useful.

c. In objective three, the curriculum outline should be

for a one year pre-selection/foundation course for

medical students focussing on

i) community orientation and social relevance

ii) adequate preparation of school leavers for a

community based medical education.

iii) necessary language, terminology and learning

skills.

d. The review of community health training experience should

be in order to formulate the sensitization strategy in the

foundation course and in the medical curriculum itself.

e. Data collection by personal visits to places and (meeting)

people identified through the first three methods of

review is

unavoidable, since one can actually get a

full idea of the experiment only by visiting their sites.

f. To involve the CMC's,a suitable mechanism needs to be

evolved.

g. Meetings no doubt would be needed. They can serve two

purposes

i) Data collection and clarification of issues and

ideas

ii) to facilitate a ferment in the direction taken

by the study.

Meetings aimed at the latter can be thoughtof as following

the study rather than being part of it.

h. It's too ambitious for one year.

Make it two years.

14

14.

/

i) Review of 'ancient medical education1 is useful only if

you have 'tentatively discovered something relevant for

today's scenario.

j) A specific review of the kinds of question papers set,

the kinds of questions asked in the viva should be done.

Examinations rule teaching and the problems of reforming

examination system is a must for any review of any edu

cation in India.

k) Some process must be started to critically review the

textbooks. Even Indian textbooks are lopsided, many

times the rationale of a particular approach is not expl

ained. This is especially true in surgery. The PSM text

book also needs critical review.

1) The questionnaire survey should provide a lot of grassroot

relevant critical information on relevance of medical edu

cation. Irrelevance is being talked about but not docume

nted. This survey should be done very systematically.

m) An opinion survey of practicing physicians and surgeons

etc., in the cities may also yield important information

in documented form.

n) A survey of the knowledge and skill base of fresh graduates

should also be done.

o) Unless there is a specific bearing on medical education how

worthwhile would it be tc revievz non-health development sector

of training in the project review?

p) The goals and objectives are so broad based and comprehensive

that, one wonders whether all these can realistically be

attempted within a year?

q) Different medical colleges may be considering different

strategies in regard to the proposed foundation course. It

may be good to consider the possibility of working on two

or more possible formulations in this regard. For instance,

one medical college may like to devote two or three months

at the beginning of the first M.B.B.S., course after the

students have been selected. Another may prefer a shorter

or longer duration still as a part of the pre-clinical

course. A third group may be considering a pre registration

course of the type that we are thinking about in Miraj. A

fourth group may like to put all their prospective candidates

through such a course for orientation to all the health pro

fessionals. Can different scenarios be evolved indicating

the potential and limitations of each?

The pilot survey of key policy makers and medical college

administrators is a good idea but they are so evanescent

and so short lived in their official roles that one may

not gain much. Perhaps those figures who did play such a

15

15.

role in the past, who had thought a great deal about

the problems under search and who have the

me to

reflect might be more useful.

IV. Final Objectives

The first project advisory committee meeting was held on

12th of May 1990. The committee explored the various

dimensions of the project outline and considered all the

important suggestions and ideas listed earlier and then

decided that the Final objectives of the study would be

1. Document descriptively/analytically - Key recommendations/experiments/innovation/experience in Medical

Education (within Medical College Sector).

2. Review Key Alternative Training Experiments to

Identify issues, Perspectives, Ideas, Pedagogy

relevant to Professional Education.

3. To build Anthology of Ideas from sample of recent

Medical Graduates with Primary/Peripheral Health

Care experience.

Health services and systems of education

must be organised fcr the good of the

people and not to meet the personal needs

of a certain cadre of doctors for material

gain or scientific satisfaction.

Carl Taylor,

1970

.. 16

16.

E.

METHODOLOGY

The final objectives, were then realised by using a multi

pronged data collection methodology that included both

’orthodox1 and 'interactive' approaches.

1.

Literature Review

Identification of key experiments/innovations , experiences

and ideas was done through an extensive literature search

which included the following components.

a) Library Reference

While reference to several professional journals were

made, the key focus was on a detailed search through

the Indian Journal of Medical Education from the late

19601s to date.

Access to the St. John's Medical College Library was

very useful. In addition, a temporary loan of back

issues of the Indian Journal of Medical Education

from the Dept, of Community Medicine at St. John's

Medical College was a major time saving development

and is gratefully acknowledged.

b) Project Announcements in Bulletins and Journals

i)

Several professional bulletins and journals

published by. the 'voluntary' sector, as well

as a few daily newspapers -were contacted for

announcements about the project.

ii) Announcements and or letters to the editor

were carried by the following (See Appendix C)

The Hindu; The Indian Express; Health Action;

mfc bulletin; Health For the Millions; Economic

and Political Weekly; BMJ (Indian Edition).

Letters to the following received nil

response :

Indian Journal of Paediatrics; Indian Journal of

Community Medicine; Indian Journal of Medical

Education; Journal of the Association of Physi

cians in India; Journal of the American Medical

Association (Indian Edition); Indian Journal of

Public Health.

The announcements in bulletins, journals and newspapers

did not get much response. Three announcements got 1

response each, 2 of which were not from medical colleges

Some of the professional journals requested for adver

tisement charges and correspondence to waive this took

time.

>

17

17.

c)

'Online' Search with the National Medical Library was

planned, but not carried out.

d)

Literature Search

Some of the other methods especially library search,

field visits and 'peer' correspondence provided a large

number of references and materials that was beyond our

expectations and to a large extent was the primary

reason for the evolution of Phase II of the project.

e)

From Peers

Some 'peers' provided substantial information and we

would like to particularly record the lists and materials

from Dr. P. Zachariah (CMC-Vellore) , Mr. B.V. Adkoli

(NTTC, JIPMER), FRCH (Bombay), Dr. Abraham Joseph (CMC Vellore), Dr. M.J. Thomas, Consultant Psychiatrist,

Bangalore and Dr. Philip Abraham, Dept, of Forensic

Medicine (SJMC, Bangalore).

2. Letters to Medical Colleges

i) Letters were sent to the Deans/Principals and Professors

of Community Medicine of 125 Medical Colleges in the

country in June - July 1990. (See Appendix

& E).

ii) A reminder was sent to those who did not respond to the

first letter in January 1991. (See Appendix: D2) .

In some cases such as the colleges in Madras and Delhi,

the reminders were hand delivered and personally followed

up by a research assistant and a colleague-researcher.

iii) In addition a letter was distributed to all the parti

cipants of the IAAME annual conference in Hyderabad in

January 1991.(Appendix F).

iv) A second reminder was sent to all the colleges that had

not responded by March 1991.

v) Depending on the replies received from medical college

principals/professors further correspondence was carried

out to determine finer details of ideas and programmes

which were considered relevant for the project.

vi) The letters to medical colleges with two reminders

elicited response from 25 colleges (a 20% response).

Some colleges sent reports and other materials apart

from the letters of reply.

(Appendix e

)

The overall response to the methodology of sending out

letters to colleges has been rather poor in terms of

quantity and also in terms of quality i.e., relevance of

materials received to the overall project objectives.

/

. . 18

18.

While some colleges wrote brief paragraphs on the experi

ments, three just provided annual reports, three sent

'nil' responses. Useful material was received and or

collected from 8 colleges. These probably also represent

the key innovators in the country who have done substantial

work.

(Appendix M).

3. Letters to Community Health/Development Trainers

i) Letters were sent to a select group of Community Health

and Development Trainers in October 1990.(Appendix G

and H).

ii) Reminders were sent in January 1991 to all those did

not respond to the first letter.

iii) Many trainers sent annual reports and training reportsand further details wherever required was elicited

through ongoing correspondence.

iv) Informal discussions were also held with some of the

trainers with whom the CHC team had contact due to

ongoing CHC linkages.

v) The CHC documentation unit already had substantial

material on

a) VHAI Courses,

b) CHAI Courses,

c) SJMC, Fangalore - CHW Courses,

d) SEARCH, Bangalore Courses,

e) INSA, Bangalore, Training Programmes and

f) CHDP, KSSS Programmes.

vi)

Substantial material was received from JNU - Centre

for Social Medicine and Community Health; Deenabandhu

- ACHAN Training Centre; RUHSA, CMC-Vellore; CINI,

Calcutta; Behavioural Science Centre, Ahmedabad and

additionally from SEARCH, Bangalore and VHAI, New Delhi.

Communications and some materials were also received

from individual free lance trainers like Dr. Uma

Sridharan (Bangalore).

In general one could say that the material collected

earlier by CHC and also received from this sector

during the project was very detailed and qualitatively

more relevant, for community oriented medical education

than some of the materials received from the medical

colleges, strengthening one of our earlier mentioned

basic premises that dialogue with the alternative sector .

would be extremely beneficial to the progress of Medical/

Education in the country.

/

19

19.

4. Survey of Medical Graduates with work experience in Peripheral

Rural Hospital and Health Care Projects (14)

i) A preliminary proforma was developed by the researchers

after a group discussion with a few (10) doctors who had

worked in peripheral rural hospitals and were presently

faculty of St. John's Medical College, Bangalore, that

had a rural placement scheme as well as gave preference

in PG and staff selection, to those with rural experience.

ii) The proforma was circulated to the same group and further

developed incorporating their feedback. (Appendix I).

iii) This was pilot tested on 10 postgraduate students who had

oeripheral health care institutional experience and then

finalised.

iv) The pre tested questionnaire was distributed at the post

graduate entrance examination of one college that gives

specific preference to candidates with rural experience

(Examinees were requested to stay back if they qualified

to be in the sample).

v) The questionnaire was distributed to eligible respondents

in another college by one of our advisory committee member

and also at the medico friend circle annual meeting in

Sevagram in September 1990.

vi) Ke explored the possibility of identifying eligible

respondents from three other medical colleges who have a

rural bond scheme and two colleges who have contacts with

rural medical officers. Due to some delays in the

receiving the lists, the survey was ended in June 1991

and responses received by then only were included in the

final report as a pilot study.

(See separate report - 14)

vii) The questionnaire was fairly extensive with 38 different

sub-sections. Table II lists out these components of

medical education on which feedback was elicited.

5. Institutional Visits

i) Visits were made to seven institutions who were identified in

the process of the ongoing project as having programmes of

significance. The field visit opportunities were utilised for

interactions with staff and wherever possible with a group of

interns who had experienced most of the innovative programmes

being studied.

ii) The objectives of the field visits were to observe innovative

programmes wherever feasible and to have informal discussions

with faculty and interns regarding various programmes and

initiatives of the respective institution. This onsite visit

and informal discussion helped us to identify the strengths and

20

20

TABLE II

GRADUATE

SURVEY COMPONENTS

( 14 )

Pre-Clinical

Other Skills___________________

1. Anatomy

2. Physiology

27. Basic Nursing

Procedures

3. Biochemistry/

Biophysics

4. Biostatistics

28. Communication

5. Sociology

6. Psychology

7. Others

29. Management

30. Training of Health

Workers / Other Personnel

31. Any other skills

Para-Clinical

8. Pathology’

9. Microbiology

10. Pharmacology

11. Forensic Medicine

Clinical

32. Internship Training

33. Selection Process

34. Teaching Methodologies

35. Curriculum Structure

12. Medicine

36. Examination System

13. Surgery

37. Any aspects of content/

process environment or

base of teaching

14. Obs. & Gynae

15. Paediatrics

16. PSM/Community Medicine

17. Psychiatry

18. Dermatology

38. Measures to enhance

social/emotional

preparedness for

C.H. Work.

19. Ophthalmology

20. ENT

21. Radiology

22. Anaesthesiology

23. Dentistry

24. Orthopaedics

25. Medical Ethics

26. Others

• 21

21.

weaknesses of various programmes, as they emerge in the

field operation with trainees - a dimension seldom

explored adequately in college annual reports or published

reports.

iii) The institutions were :

a) Christian Medical College, Ludhiana;

b) Christian Medical College, Vellore;

c) Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha;

d) St. John's Medical College, Bangalore;

e) King George Medical College, Lucknow;

f) All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi; and

g) JIPMER, Pondicherry

iv) The visits were linked to other meetings (incidental

opportunity!) and or specially planned in the context of

the project. In two cases it was in response to the

institutional need.

v) Appendix lglists out the salient features of the insti

tutional visits.

vi) Due to a certain degree of inadequate planning, lack of

initial standardization and some logistic, communication

and time schedule problems the field visits though very

meaningful and productive were not of an adequate

'standardised methodology' to allow for inter college

comparisons among the innovators.

vii) However since the research team who visited the college

and observed programmes and interacted with faculty,

interns or students were the same in all colleges and

the method of informal individual and modified focus

group discussion was used, some observations and

conclusions could be drawn from the field visits about

the overall process of medical education reform and many

of the problems and obstacles to change as well as the

diversity of experiences.

viii) All the colleges in the original protocol could net be

visited but the 'seven college field visit1 was a very

relevant experience and definitely gave additional

perspectives that was not possible to get from reports

and correspondence.

6. Meetings and Interactive Dialogue

i) To increase the interactive nature of the project, links

with peers were maintained not only through correspondence

but also through meetings. Some of these were comple

mentary to the project and some organised in the context /

• 22

22.

of the project. Other meetings to which CHC researchers

were invited as participants or resource persons listed

were also utilized to explore ideas and innovations

towards an appropriate medical education.

ii) Some of the meetings helped to clarify issues and ideas

and others just to stimulate further on different aspects

of the challenge.

iii) The key meetings are listed in Appendix

.

iv) From the very beginning it had been decided that the study

would have a strong interactive component and the resear

chers would use every available opportunity for discussion

with peers interested in medical education alternatives.

These would be discussions at individual level as well as

in groups during meetings and dialogues specially called

for the purpose or opportunities utilised at ongoing

meetings/visits related to other topics and occasions.

v) This interactive dimension of the project was emphasised

and operationalised as follows :

a) Many discussions with the Advisory Committee were

not just organisational but interactive in the

context of them being senior peers. Several issues

were raised and explored.

b) Discussions with peers with relevant experience

during visits t'o CHC and/or Bangalore or elsewhere

were held whenever possible.

c) Correspondence with peers and contacts throughout

the study.

d) Three reports were sent out to all our contacts

in November 1990, May 1991 and January 1992. Some

peers responded to ideas and project developments

mentioned in these reports.

7. Approaches - Orthodox and Interactive

As a general policy of the project, and keeping in mind CHC1s

own approach and commitment to networking, the approach to

research was a combination of ‘orthodox1 as well as interactive.

(See Table m ).

While ‘Orthodox1 approaches helped to standardise procedures

and bring in the required rigour the interactive approaches

helped to increase the sense of participation and involvement

among respondents as well as often helped to tap the ‘affective

domain' as much as the cognitive in the data collection process

.. 23

23

Very often we could find out what people felt about things not

only what they thought. Many negative impressions and often

more reflective responses were picked up by this method. Also

different perspectives on the same programme especially from

'organisers' as well as 'participants' were explored. All

this would not easily be possible through ar. objectivised

standardised questionnaire. Since our study was not 'quanti

tative' in its assessment of the situation (not how much?) but

was trying to find out the range of 'what/where/why of medical

education reform'. This combination of methods helped to get

a wider qualitative impression of the diversity of innovations.

Table III

Research

approaches

irt

the

Orthodox / Classical / Established

Study

Interactive

* Literature Review

* Peer Group correspondence

and meetings.

* Letters to Colleges

(with reminders)

* Field visits to colleges

and Group discussions

with faculty/interns

* Letters to Trainers

(with reminders)

* Questionnaire Survey

(Graduates)

* Correspondence with

College respondents and

Community Health Trainers.

"The purpose of medical education is not to produce

Kobe! Prize Winners but to provide doctors for

health services, who will meet the health needs of

the country in which anc for which they are needed."

WHO Regional Committee for South East Asia.

24.

F.

ORGANISATIONAL

DYNAMICS

To operationalise the methodology, five components of the

Organisational dynamics of the project are outlined. These

include :

a. The Research Team

b. The Advisory Group

c. Peer Group Support

d. Project time and process schedule

e. Financial support

The related organisational dynamics were evolved, step by step

as the project took concrete shape. Modifications and changes

were made in response to various constraints and contingencies.

The following are the salient features of each of these orga

nisational components as they evolved during the two year

project, a second year phase II being added to the initial one

year phase I time framework, due to the response and ongoing

dynamics.

a)

The Research Team

There were two primary researchers whose background expe

rience has been outlined earlier.

During the second year Dr. Thelma had to coordinate

another Evaluation Study and Dr. Shirdi Prasad Tekur of

CHC provided additional support as a research associate.

Right through the project we tried to identify suitable

research assistants to join the team on a full-time basis.

Out attempts were unsuccessful because there were very few

research-oriented people interested in medical education

per se, or adequately experienced for this 'interactive

*

sort of project.

The research team therefore tried to involve other members

of the CHC team for specific tasks and various other

contacts were enlisted for short-term assignments (See

Acknowledgements) .

Another problem was that much of the material collected or

compiled was such that it was not possible to delegate its

analysis or assimilation to research assistants. Most of

this had to be done by the primary researchers themselves.

During the second year a request was made for a middle

level staff member from the participating medical colleges

(who would be willing to support the project on a sabattical)

to join the research team. Inspite of some scouting around .

25

25.

/

such a possibility could not be operationalised.

project had to be completed by the primary team.

Thus the entire

The Research team were based in CHC utilising all its facilities

but much of the compilation/analysis was done from a home based

office by the researchers.

b)

The Advisory Group

A small advisory group with 4 resource persons was formed.

included :

These

1) Dr. C.M. Francis - Previously Dean of St. John's Medical

College and Kottayam and Calicut government medical

Colleges and presently Director, St. Martha's Hospital,

Bangalore.

2) Dr. P. Zachariah - Professor of Physiology of CMC-Vellore

and Coordinator of the MMC - Miraj Medical College Project

(when on Sabbatical).

3) Dr. V. Benjamin - Previously Professor, Community Health

and Development Department of CMC-Vellore and presently

Training Consultant to CMAI, New Delhi.

4) Dr. George Joseph - Previously Professor, Centre for

Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi and presently Executive Director, CSI Ministry of

Healing in Madras.

The resource persons were selected for their consistent interest

in the challenges of reorientation of medical education and for

their previous track record in supporting and being part of medi

cal college innovations. They also represented perspectives in

medical education from the different types of experience, viz.,

pre-clinical teaching, community medicine teaching, administra

tion and research. This greatly enhanced the overall planning

of the study.

The advisory committee met formally approximately every quarter

(refer Appendix-L). In addition, since two of the members were

Bangalore based and the two others visited Bangalore fairly

frequently, there were many opportunities for informal inte

raction with the researchers. Some support was also available

through correspondence and in the final phase many of the initial

outputs/reports of the project were intensively reviewed in a

special review meeting in October 1991 and thereafter indivi

dually as the occasion arose.

c)

Peer Group Support

Institutional Linkages - Formal and Informal

The project proposal had envisaged that collaboration and support

from other institutions and associations to widen its scope, as

well as to ensure that it would be of significance and relevance/

• 26

27.

Z

to a larger number of people and initiatives in the 1990's.

It had also been decided to request every collaborating

institution to nominate one of their faculty/staff members

to participate as a peer group member of the study.

This linkage was explored with CMAI, CHAI and VHAI; the three

CMC's - Vellore, Ludhiana and Miraj; St. John's Medical College,

Banoalore and the National Teacher Training Centre, JIPMER,

Pondicherry.

Ultimately as the two year project evolved the following

linkages were established :

1) Formal

i)

CMAI (New Delhi) and CHAI (Secunderabad) co-sponsored

and provided financial support for both Phase I and

Phase II of the project, with CMAI providing the major

share of Phase I support.

ii)

CMC-Ludhiana provided some financial support for

Phase I of the project and offered peer group support

through their Principal, Dr. Alex Zachariah.

iii)

CMC-Vellore, St. John's - Bangalore and Miraj Medical

Centre offered peer group support through their

nominees Dr. Abraham Joseph, Vice Principal and Head

of Department of Community Health, Dr. Prem Pais,

Associate Professor of Medicine and Asst. Medical

Superintendent and Dr. Kalindi Thomas of the Depart

ment of Community Health respectively.

2) Informal

V.’hile these formal linkages were established, the 'inter

active methodologies' of the ongoing project led to the

development of informal links and contacts with some of

the faculty/members of a larger number of institutions

and initiatives. Some previous links already established

by CHC were strengthened including

a) Voluntary Health Association of India, New Delhi

b) Informal evolving network of Community Health

Trainers in India

c) Foundation for Research in Community Health, Bombay

d) medico friend circle (Bombay - Pune)

e) Centre for Social Medicine and Community Health,

(Jawaharlal Nehru University), New Delhi.

f) National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore

28

28

Some new ones also emerged including

i) Network of Christian Medical Colleges

ii) NTTC, JIPMER, Pondicherry

iii) Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences,

Sevagram, Wardha.

iv) King George Medical College, Lucknow.

v) Centre for Medical Educational Technology,

AIIMS, New Delhi.

vi) NHL Municipal Medical College, Ahmedabad

vii) Indian Association for Advancement of Medical

Education

viii) A.P. Health University

ix) Osmania Medical College and Social Paediatric

Unit, Nilufer Hospital.

3) Individual Peer Support

Informal peer group support was also sought from a large

number of people often in their individual capacity as well.

(Appendix—P). A wide circle of contacts was established

through this process.

While the 'individual approach' was probably more fruitful

than the 'institutional approach', at the end of the project

one cannot but feel that the overall interactive process was

not as productive or active as we had initially hoped.

d)

Project -time and Process Schedule

The project time framework can be divided into three phases, as

it evolved since the idea was first conceived in February 1989

by CHC.

A Pre-project phase from February 1989 till March 1990

when the idea evolved into a project proposal and the

sponsors and linkages were identified (See Appendix - L).

Phase I from April 1990 till June 1991 when the objectives

were clarified by an interactive process, and then opera

tionalised through a multidimensional methodology. Data

collection was initiated and completed by June 1991 (See

Appendix - L).

Phase II from July 1991 till June 1992 when the data was

analysed and compiled into a range of definitive outputs.

This phase was also marked by the beginning of a collective

dialogue and lobbying process which will end in the Medical

Educators Review Meeting in June, 1992, the finale of the

Project (See Appendix - L).

/

29

29.

iv) Phase III has not been thought of since CHC, CHAI and

CHAI, the project partners are convinced that any further

commitment to the 'evolution1 of an appropriate medical

education must be based in a specific medical college or

a group of medical colleges and cannot continue to be a

pre occupation or thrust of any of these three organisa

tions any longer. The attempt to bring together Indian

experiences and provide some stimulus for medical educa

tors fits in with the catalyst role of all three orga

nisations, (to stimulate/support a process towards more

relevant health professional education'). Now the

initiative has to be carried further by a medical college

group or a collective/network of colleges. It is hoped

that the June 1992 dialogue will explore this aspect among

other issues discussed in the meeting.

e)

Financial Support

The pre-project phase and the first 3 month's of Phase I were

supported from the resources of the CHC, CMAI, CHAI and

CMC-Ludhiana were partners and co-funded Phase I. Phase II

was co-funded by CHAI and CHAI.

The overall budget of the project was Rs. 4,52,400/-, for the

2 year phase. The detailed break-up of the project grant and

related details is shown in Appendix-N.

Some of the other CMC's were invited to consider the possibility

of co-funding the project but there were organisational/policy

issues that came in the way of a broader consortium of funding

putting a heavier burden on CHAI and CHAI than initially planned.

Their gesture in taking joint responsibility of seeing the

project through was most welcome and is appreciated.

The best way to avoid large scale migration

is to train doctors to work in the conditions

that prevail in their own country.

For most

developing countries this means a curriculum

overwhelmingly geared towards Primary Health

Care in the rural areas.

Earthscan (1978)

I

30

G.

RESPONSES - RESULTS - FINDINGS

The outcome of the study in terms of responses, results and findings

may be discussed under the following subheadings

a) Literature Review

b) Medical College Survey

c) Alternative Training Sector Survey

d) Graduates Survey

e) Some overall general observations/findings

a) LITERATURE REVIEW

i)

The literature review lead to the identification and

compilation of over 750 references on key Indianexperience

in Medical Education which has been arranged into a

bibliography (arranged alphabetically). While the main

source was the Indian Journal of Medical Education, arti

cles from other Indian Journals and articles on Indian

experience in WHO/foreign journals were also identified.

All the personal communications and unpublished reports

and papers received by the researchers during the phase

of study have also been included.

ii)

Some WHO sources as well as a large number of references

on more recent community/primary health care oriented

innovative experiments in other countries was also

collected. We also identified some key papers on issues

and directions from foreign sources. Just a few key

foreign papers have been included in the bibliography,

though the main focus is on Indian experience.

iii)

40

key titles were also identified and an annotated

bibliography (stimulus for change) was prepared as a

basic collection for a medical education cell of a

medical college.

iv)

A key aspect of the literature review was a thorough

study of what the ’experts' committees have said about

Medical Education and a detailed compilation of reco

mmendations from Bhore (1946) till Draft National

Education Policy for Health Sciences (1989) under

different sub headings/aspects of medical education.

This 'ready reckoner' would help medical colleges to

locate their own organisation and structure and curri

culum framework against the key recommendations of the

expert committee all of whom were focussed on both

social relevance as well as community orientation.

The literature review also identified a large number

of ideas/innovation within medical colleges and within

31.

other sectors of innovation mentioned in ChapterC which \

were not identified by surveys and interactive methods.

All this forms parts of Volume I of the Faculty Resource

Manual which is expected to be a concrete definitive

output of the two year project (See later Chapter H (e)(v).

b) MEDICAL COLLEGE SURVEY

i) 25 colleges responded tc our project related letter (which

included two reminders). Out of the 125 colleges in our

sample this meant a 20% response.

ii) While we cannot conclude that the non-respondents are

necessarily non-innovaters, we could identify only 7

more colleges from the literature review, who had

reported innovative programmes in 'literature' but had

not responded to our letter. This brings the total upto

32 (25.6%).

iii) Table IV shows a statewise distribution of the 'respon

dent' colleges including the sources of identification.

7 colleges, one each from seven states visited by

researchers is also shown.

iv) Recent •guestimates' of the health ministry and planning

commission are that the number of medical colleges as

of 1992 are between 160-170. Most of these are of recent

origin, mostly 'capitation fees' colleges in the states

of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Tamilnadu. Since most are

not recognised by MCI they have not begun to appear in

official statistics. For our survey we restricted our

selves to the 125 which were listed in a guide-publication

on medical colleges for entrants in 1990.

(

)

We did not try to get details of these newer colleges

partly because they were difficult to get through other

sources and partly because of our assumption that they

were too new, and too preoccupied getting established to

initiate experiments or initiatives in social/community

orientation.

v)

Tables v-IX list out key ideas/and innovations that were

identified through the materials sent by medical colleges;

collected during field visits; received from peers; iden

tified through literature search; or already available

with CHC in its pre-project collection.

The ideas are divided into five groups

- General Objectives and Curriculum contents

- Pre-clinical Phase

- Para-clinical Phase including Community

Medicine (PSM) Teaching

- Clinical Phase

- Internship

32

32

TABLE

IV

Medi cal College Survey

(Sample

l

125 j

Respondents - Statewise Distribution and Source

Stat e

ho. in

Sample

Responded

to Survey

From

Litera

ture

Revi ew

Vi sited

Total

(D)

(E)

(B + C)

(A)

(B)

(c)

1.

Andhra

9

2

1

2.

Assam & North

East

4

-

-

3.

Dihar

9

-

-

4.

Gujarat

6

1

1

-

2

5.

Haryana

1

-

1

-

1

6.

Himachal Pradesh

1

-

-

-

-

(1 )*

-

3

-

-

7.

Janimu/Kashmi r

2

-

-

-

-

8.

Karnataka

10

2

-

1

2

9.

Kerala

6

1

-

-

1

10.

Madhya Pradesh

6

-

-

-

-

11. Maharashtra

16

7

2

1

12. Orissa

3

-

-

-

-

-

13. Punjab

*

(1)

9

5

2

1

2

14. Rajasthan

5

1

-

-

1

15. Tamilnadu

13

4

-

1

4

16. Uttar Pradesh

9

1

1

1

2

17. West Bengal

7

-

-

-

-

18. New Delhi

4

2

1

1

3

3

2

-

1

2

125

25

7

7

19.

Other Union

Territories

*

(2)

32

* Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad and LTM Medical College,

Sion, Bombay were visited by the researchers incidentally.

Not included in formal field visits.

33

33.

Totally about 50 strategies/innovations have been

identified which taken together, collectively represent an

evolving framework of an alternative medical curriculum

within the existing MCI determined framework.

It is important to clarify here that since the letter

was an openended survey it helped to get a qualitative

assessment of the range and diversity of innovative

strategies. But what percentage of these respondents

TABLE

V

Medical College Strategies

Objectives and Curriculum Structure - General

1. Defining Institutional Objectives

2. Defining Intermediate (Departmental) and

instructional objectives

3. Development of Medical Education Cell with

adjunct faculty

4. Faculty Training Programmes in medical education

skills

5. Selection Procedures other than academic merit

(Psychological / Social skills / leadership /

value orientation)

6. Curriculum development including

integration,

i)

identification

ii)

of core abilities,

prioritization

iii)

(curriculum planning committees)

identifying

iv)

skills

7. Examination Reforms

objective

i)

examinations

restructuring

ii)

assessment towards HFA/PHC

priorities

8. Faculty/student involvement in Medical Education

feedback/research

9. Tutorial system

10. Student electives

11. Student involvement in Research

12. Regular faculty meeting/facuity-student meetings

curriculum

i)

issues

Social-Societal

ii)

issues

13. Student nurture programme/curricular/extracurricular

14. Rural Bond (Placement) Scheme

15. Continuing Medical Education for alumnus/others

(for further details including colleges involved

refer Appendix J & K)

/

/. -.34

34.

TABLE

VI

Medical College Strategies

Pre-Clinical Phase

1.

2.

Foundation Course for entrants

Community-based orientation programmes

3.

Introduction of New Subjects

i) Behavioural Sciences ii) Ethics

iii) First Aid

iv) Nursing

v) Integrated Growth

and Development

4.

Clinical Orientation in pre-clinical phase

5.

6.

Humanisation of pre-clinical practicals

Samaritan Medicine

7.