LEARNING FACILITATION WORKSHOP 26™ TO 28™ JULY 2011

Item

- Title

-

LEARNING FACILITATION WORKSHOP

26™ TO 28™ JULY 2011

- extracted text

-

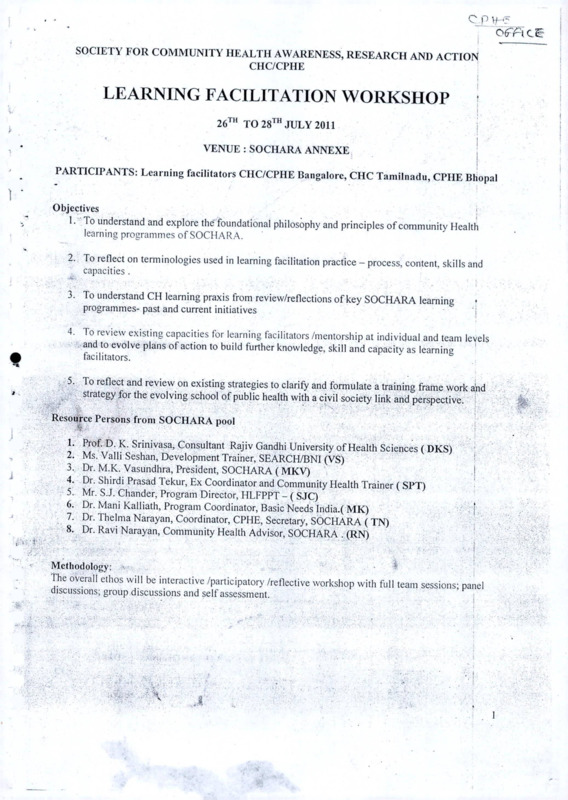

SOCIETY FOR COMMUNITY HEALTH AWARENESS, RESEARCH AND ACTION

CHC/CPHE

LEARNING FACILITATION WORKSHOP

t

26™ TO 28™ JULY 2011

>

VENUE : SO CHARA ANNEXE

PARTICIPANTS: Learning facilitators CHC/CPHE Bangalore, CHC Tamilnadu, CPHE Bhopal

Objectives

1. To understand and explore the foundational philosophy and principles of community Health

learning programmes of SOCHARA.

2. To reflect on terminologies used in learning facilitation practice - process, content, skills and

capacities .

3. To understand CH learning praxis from review/reflections of key SOCHARA learning

programmes- past and current initiatives

-i

4. To review existing capacities for learning facilitators /mentorship at individual and team levels

and to evolve plans of action to build further knowledge, skill and capacity as learning

5. To reflect and review on existing strategies to clarify and formulate a training frame work and

strategy for the evolving school of public health with a civil society link and perspective.

a .

Resource Persons from SOCHARA pool

1

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

J

t

’•

Prof. D. K. Srinivasa, Consultant Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences ( DKS)

Ms. Valli Seshan, Development Trainer, SEARCH/BNI (VS)

Dr. M.K. Vasundhra, President, SOCHARA ( MKV)

Dr. Shirdi Prasad Tekur, Ex Coordinator and Community Health Trainer ( SPT)

Mr. S.J. Chander, Program Director, HLFPPT-( SJC)

Dr. Mam Kalliath, Program Coordinator, Basic Needs India.( MK)

Dr. 1 helma Narayan, Coordinator, CPHE, Secretary, SOCHARA ( TN)

Dr. Ravi Narayan, Community Health Advisor, SOCHARA . (RN)

’•

Methodology:

•

The overall ethos will be interactive /participatory /reflective workshop with full team sessions- panel

discussions; group discussions and self assessment.

1

CM e

Date

26.07.2011

( Tuesday)

Time

Theme for the

day:

9.30 am 10.30am

10.3011 .QOam

1 LOO12.00pm

Programme ________________

THE PHILOSOPHY OF LEARNING FACILITATION

12.001.00pm

Session -II: Challenges in Learning Facilitation : Context,

Values and Conflict resolution. (VS)

1.00-2.00

2.00-3.00

___________ Lunch and Fellowship

________________

Session - III : Inspiration for Learning Facilitation ( RN)

(Exploring training resources/inspiration that provoked /supported

SOCHARA experiments ( An interactive session)

3.00-3.15

3.30-4.45

Tea Break

Session - IV Group Discussion -I

Identifying challenges from praxis in Bangalore /Chennai/ and

Bhopal teams. ( Check List)

_

_____ ______________ Staff Get together______________ ___

Assessing Training experiences

(Am I a good learning facilitator/field mentor/ mentor - A self

assessment and reflection) __________________

MANAGEMENT AND METHODS OF LEARNING

FACILITATION

4.45-530

(Home work)

J.

Theme for the

day:

27th July 2011

(Wednesday)

\

Il1

> Introduction

> Self Assessement ( Training facilitation Score)

Tea Break

i

Session -I : Exploring Building Blocks in Learning Facilitation

(RN)

( Dichotomies and Paradigms; content and process issues, skills,

and capacities)

I/

n

n

u

’1

■

. i

'■

9.30- 10.30

10.30- 10.45

10.45-11.45

11.45-1.15

1.15-2.00

2.00-3.15

3.15-3.30

3.30-4.30

!

4.30-5.30

Reflections on Day One - Key learning /more questions

Tea Break______________

1

Session- V : Learning facilitation - (RN)

Wliy/Who/What/How/WhenAVhere - Evolving a check list

Session VI: Exploring and understanding structure and frame

work- basic concepts-(DKS)

(Curriculum/Syllabus/ Objective/ Modules/ methods / assessment/

evaluation) ______

Lunch and Fellowship

Session VII - Challenges in Community based training

strategies for Health and Non Health Groups - ( SPT)_____

_________ Tea break

;

Session- IX: Civil Society School for Scholar Activists ( TN)

>

Strategies towards a school for scholar activist

Revisiting what we are doing with a new SPH Lens

Role and definition of a scholar activist

Group Discussion on SOCHARA - Website ( CLIC'team)-

J

2

■■

28th July 2011

(Thursday)

Theme for

the day:

9.30 - 10.30

10.30- 10.45

.

LEARNING FROM SOCHARA PRAXIS /FUTURE

( Reflections of Day Two)

lEgyJgarning / more questions)

o—•--------------------------Tea Break

H.45 - 1.15

Sess i onX

" ’

Fm—:------ — ----- -------- _

SSX—... -

1 • Health for Non Health Group - ( MK)

(Textual - Contextual)

2. Women’s Health Empowerment Training -(TN )

( Frame work/Manuals/Learning network meetings)

.1.15-2.00

zocPToo

3.00-3.15

335^4.00

■77—7— -------------- Lunch and FeHowship

Session X ( Contd)

---------- ------------- ----4. Lessons from interactive programmes- Life Skill

Educa .on and Joyful Learning series - (SJC)

(adapting learning to group/joyful learning series)

!

■

7;— ----------- ------------- Tea break

Setting individual and collective group goals

a* Bhopal Plan

b. Bangalore Plan

c. Chennai Plan

1

4.00-5.00

i

I

I

3

t Workshop (SOCHARA)

Leaning Facilitation

26tl,,27th and

L. 28th Jniy 2011

A - Background Papers and Documents.

- Ivan Urich

.h« W >•

toiu.

2. ThoHk.mrd.yori'tals- Stew-™

t Banking Edition enc k-Ridtin, i- <

4. Approacho to Training - k LU John s S.aks

onrros.ed Pi in Io Pre ire

5. Our ideas about Training

6. The learning model ■ Action- refk* .to?

7. Training and Learning

8. The individual in the Group

9 Do we listen?-A questionnaire

Ho,. o,« » aolos

11. Looking inwards - The

development , John Staley, SEARCH

12. A perspective on conflict

13. Managing conflict in an organization

14. Dealing with Conflict

S’. Our'appSeh to planning - A

s, E,„ra!1,, „d FoodSook- te. W- "

Workers Learn - David Werner and Bill

17. Planning a training program - from Helping

Bower

18. SEARCH training papers

a) Respect for other people

b) The conditions for learning

c) Leadership Quiz

. .

d) Solving problems and making ( ecisio

e) Elements of team work

f) Group discussions and meetings

g) Empathy and Sympathy

h) Feedback

i) Case studies - episode and cases

j) Setting goals

ciences.A statement of shared concern and collectivity

19. Education Policy for Health Sci

- iQQ1 (SOCHARA)

.

from Community Health Trainers dl®l°gue ^SOCHARA model ( from the trainers network

20. A Collective approach to 1 raining

Project)

i

4

B - BASIC READING LIST FOR SOCHARA LEARNING

FACILITATORS

1. Limits to Medicine - Medical Nemesis: The expropriation of Health, Ivan Illich Penguin

books

2. Pedagogy oi the Oppressed, Paulo Friere, Penguin education

j.

>> riiing ior Distance Education : A Manual tor writers of distance teaching texts and

independent study materials, The international extension College 1979

4.

1 eaching for better learning - A guide for teachers of Primary Health Care staff, F.R.

Abbatt, World Health Organisation, Geneva, 1980

5. People in Development - A trainers manual for groups , John Staley , SEARCH, 1982

6. Helping Health Workers Learn - A book of methods, aids and ideas for instructors at

village level, David Werner and Bill Bovvers, The Hesperian Foundation, 1982

7. From development worker to activist- A case study in participatory training, Desmond A.

D’Abreo , Deeds, 1989

8. Community Health Trainers Dialogue, Oct 1991, CHC SOCHARA workshop report’

9. Enticing the learning - Trainers in development, John Staley, University of Birmingham,

UK, 2008

•

10. Learning programmes for Community Health and Public Health - Report of the

National Workshop — April 2008 (A CHC Silver Jubilee publication)

.

•’

’

..

.•

i

..

L

F

-■

5

t

■

•

■

4

-i

I

' 'II

1

Limits

> to Medicine

3

1

J

Medical Nemesis:

The Expropriation of Health

Ivan Illich

Penguin Books

i

OF WORLD CUtm

6 SHB1B.P. WADIAROAD.

BANGALORE-560 004.

} /it’ Recovery of Health

The Politics of Health

desirable to base the limitation of industrial societies on a shared

system of substantive beliefs aiming at the common good and

enforced by the power of the police. It is possible to find the

needed basis for ethical human action without depending on the

shared recognition cf any ecological dogmatism now in vogue.

This alternative^ to. a new .ecological religipn or., ideology©is

based "on an agree me nt... a bout ,bas.ic values and on procedural

rules'.

It can be demonstrated that beyond a certain point in the

expansion of industrial production in any major field of value,

marginal utilities cease to be equitably distributed and overall

effectiveness begins, simultaneously, to decl ine,.l£lhejndu st rial

modQ_oI..product:orr expands-beyond a certain stage and con

tinues to impingc-onThe autonomous mode, increased personal

suffering and social dissolution set in. Jn tKe interim - between

the point of optimal synergy between industrial and autonom

ous production and the point of maximum tolerable industrial

hegemony - political and juridical procedures become necessary

to reverse industrial expansion. If these procedures are con

ducted in a spirit of enlightened self-interest and a desire for

survival, and with equitable distribution of social outputs and

equitable access to social control, the outcome ought to be a

recognition of the carrying capacity of the environment and

of the optimal industrial complement to autonomous action

needed for the effective pursuit of personal goals. Political pro

cedures oriented to the value of survival in distributive and

participatory equity are the only possible rational answer to in

creasing total management in the name of ecology.

-bcJhc.resulLpf

political .action reirforciog^iL-elhi.caLawakeniiig^.P.cople will

i want to limit transportation because they want to move efficientI ly, freely, and with equity; they will limit schooling because they

• want to share equally the opportunity, time, and motivation to

? learn in rather (han about the world; people will limit medical

;

specific. goali^t^k.share,.! . ■■■ thei: use of legal and political

procedures that peri nit jm o- idu <!s and groups to resolve conincts'ansFng^rom their pursu;:i of dil'crcnt goals. Better mobility

will depend, not on some n -•.v

‘ ’.ind of transportation system,

mobility under personal

but on conditions mat ma-n personal

;

control more valuable. B-.m.'- learning opportunities will de

pend, not on more inferm.iim.'i about the world better dis

tributed, but on the limut; :; ^ of capital-intensive production

for the sake of interesting woi i mg concmions. Better health care

will depend, not on seme

tl'crapeutic standard, but on the

level of willingness and co i.;,m ncc to engage in self-care. The

recovery of this power dcpeiids .m the recognition of our pres

ent delusions.

The Right to Health

i

Increasing and irreparable damage accompanies present in

dustrial expansion in al •cLtors. In medicine this damage

appears as ialrogencsls. Ut; •..>. ™csisj- clinical when pain.^sickness, and death t^s.ult.frcn ricdicaj ern e ^it is social when .health

policies reinforce an ind.u;i.i;d organization that generates illheahh; it is cultural and symbolic when medically sponsored

behaviour and delusions.re./.i >ct. the vital autonomy of people

by unclermin mg. their compcience in growing up. caring Jor

each other, and ageing, oi when medical intervention cripples

personal responses to pa m disaoility, impairment, anguish, an^

death.

Most of the remedies row proposed by the social engineers

and economists to reduce ic.uogenesis include a further increase

of medical controls. Thes? so-called remcdies.generatc.-se.c.ondordcr iatrogenic ills on each cf the three critical levels: they

iatrogenesis self-rcinfoiciog.

render clinicai, social, anc <i-liitural

-i.c

cdccis

of the medical tcchnoThe most profound iat ogen

a

result

of

those

non-icchnical

functions which

structure are a ------- -.

support the increasing ii!,' litutionalizalion of values. The

technical and the non-tc. ! r.ical consequences of institutional

therapies because they want to conserve their opportunity and

power to heal. They will recognize that only the disciplined

limitation of power can provide equitably shared satisfaction.

The recover yof a u t o n q m

!

271

270

1

©

The Politics of Health

i i\e Recovery of Health

medicine coalesce and generat_c_a.jiew-kind-<of.’Suffefrngi.-^naes-

lion would tax medical technology am: professional activity

thclized, impotent, and solitary survival in a world turned into a

until those means that can t-c handloi i y layrncn were truly Y

available to anyone wanting access to ; em. Instead of multi- .

.1

plying the specialists who can gian*. an;. ■ ;ic of a variety of sickroles to people made ill by th<.:r work

id theii life, the new

legislation would guarantee the right oi people to drop out and

hospital ward. Medical nemesis is the experience of people who

are largely deprived of any autonomous ability to cope with

nature, neighbours, and drcams, and who are technically main

tained within environmental, social, and symbolic systems.

Medical nemesis cannot be measured, but its experience can be

1

to organize for a less destruct ve way <-i ;:fe in which they have

shared. Tlte intensity with which it is experienced will depend on

more control of their cnvironm-. iit In

.d of restricting access

the independence, vitality, and rclatedncss of each individual.

to addictive, dangerous, or useless dri.’;’,- and procedures, such' :

The perception of nemesis leads to a choice. Either the natural

boundaries of hutnairendcavour are estimated, rccogmzed, and

traTisfai^dJm^o.liikaJ

limits, or cojnj^ulsoiyjur-

legislation would shift the full burden of their responsible use

on to the sick person and his next of kii

Instead of submitting

the physical and mental integpip, of citi.-cns to more and more ; \

vival in a planned and engineered hell is accepted as the altern-

wardens, such legislation would recogu 'c each man’s right to

Until recently the choice between the

define his own health - subject only to limita'ior.s imposed by

ative to extinction.

A

i

politics'of voluntary poverty and the hell of the systems en

respect for his neighbour's rights. Instead of strengthening the ’ i

gineer did not fit into the language of scientists or politicians.

licensing power of specialized ps-ers and government agencies, i j

Our increasing confrontation with medical nemesis now lends

new legislation would give the nubiic a ' oice in the election of •!

new significance to the alternative: either society must choose

healers to tax-supported health jobs. Im'. . id of submitting their

the same stringent limits on the kind of goods produced within

performance to professional review orpa; izar.ons, new legisla

which all its members may find a guarantee for equal freedom,

tion would have them evaluated by the ionmunity they serve.

or society must accept unprecedented hierarchical controls3 to

provide for each member what welfare bureaucracies diagnose

as his or her needs.

In several nations the public is now ready for a review’ of its

health-care system. Although there is a serious danger that the

Health designates a process of adapt:1.!:<; 1. It ’.s not the result

of instinct, but of anjAHo_n.Qn.i3iu>..}el. cu!- uj'idLy^KLpcd_i£a.GU.pti

alization of life, the debate could still become fruitful if atten

to^so.cially,ci^i(^lreali^y. Il designate:, the ability to adapi to

tion were focused on medical nemesis, if the recovery of per

changing environments, to gre wing up t-ttd to ageing, to healing

sonal responsibility for health care were made the central issue,

when damaged, to suffering, anc to the jx:aceful expectation of

and if limitations on professional monopolies were made the

death. Health embraces the future as \>cll, and therefore in

major goal of legislation. Instead of limiting the resources of

3. The Honourable James McRuer, Ontario Royal Commission Inquiry into

Civil Rights (Toronto: Queen’s Printer. 1968. 1969. 1971). On self-governing

professions and occupations, see chap. 79. The granting of self-government

cludes anguish and the inner resources tc I vc with it.

H

Health designates a process by which each person is respons

ible, but only in part responsible io others. To be responsible

may mean' two things. A man s responsible for what he has

done, and responsible to anotlc person >t group. Only when he

is a delegation of legislative and judicial functions that can be Justified only

feels subjectively responsible oi answet

as a safeguard to public interests.

will the consequences of his failcre be m : criticism, censure, or

272

i

Health as a Virtue

forthcoming debate will reinforce the present frustrating medic-

doctors and of the institutions that employ them, such legisla-

P

I

j

:>lc to another person

273

i

t'

■ ipic'

I

The Politics of Health

punishment but regret, remorse, and true repentance.4 The con

sequent states of grief and distress are marks of recovery and

heahng, and are phenomenologically something entirely diflerent from guilt feelings. Health is a task, and as such is not com

parable to the physiological balance of beasts. Success in this

persona! task is in large part the result of the self-awareness,

self-discipline, and inner resources by which each person reg

ulates his own daily rhythm and actions, his diet, and his sexual

activity. Knowledge encompassing desirable activities, com

petent performance, the commitment to enhance health in

others - these are all learned from the example of peers or

elders. These persona, activities are shaped and conditioned by

the culture in which t ie individual grows up: patterns of work

and leisure, of celebration and sleep, of production and pre

paration of food and drink, of family relations and politics.

Long-tested health patterns that fit a geographic area and a

certain technical situation depend to a large extent on longlasting political autonomy. They depend on the spread of

responsibility for healthy habits and for the socio-biological

environment. That is, they depend on the dynamic stability

of a culture.

The level of public beakh

degree to which

the means and responsibility for coping with illness are 1distributed among thejotal. population. This ability to cope can be

enhanced but never replaced by medical intervention or by the

hygienic characteristics of the environment. Ibat society which

can reduce professional intervention to the minimum wiU pro

vide the best conditions.for health. The greater the potential for

autonomous adaptation to self, to others, and to the environ

ment, the less management of adaptation will be needed or

tolerated.

A world of optimal and widespread health is obviously a

world of minimal and only occasional medical intervention.

Healthy people are those who live in healthy homes on a healthy

diet in an environment equally fit for birth, growth, work, heal-

j he Recovery of Health

ing, and dying; ’hey arc susnJ - - d by a culture that enhances the

conscious acceptance

iin.ii

popui.-tion, of ageing, of in

complete recovery and cvv ■minent death. Healthy people,

need minima) bureau-ratic uitcrfcrencr to mate, give birth,

!

share the human condition, and die.

(

Man’s consciously lived fraydity, jndividualitv^and^relaicdness make the experience of p--.n, of sickness, and of death an

Tfftegral pari of his life. The ability to copc with (his trio autono

mously is fundamental to his health. As he becomes dependent

on the management of his mtimacy, lie renounces his auto

nomy and his health

d-.< :iiic. The hue miracle of modern

medicine is diabolical It cot? : is in making not only individuals

but whole population - survive .m inhumanly low levels of per i

sonal health. Medical neme:.. is the negative feedback of a

social organization that set u-m to -improve.and^equalj.zc the J

opportunity for each man to c.ipc in autonomy and ended by

j

destroying it.

i

1

• ^A,!CrcdjSchutz- ,S<)rnc Hquivccations in the Notion of Responsibility1

'iQAdt CC'e^P

AaP/rS' V0L 2’ S,UdiCS ‘n S0™1 Theory

HaSuc: Nijhotr’

pp. 2/4—6.

274

j

r-i -

THE HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

I : ORIGINAL PROPOSITION

(ABRAHAM MASLOW)

Sei f actualization need

Esteem needs

I

MATURATION PROCESS:

REALIZATION OF

GENETIC POTENTIAL

Belongingness needs

Safety needs

Physiological needs

1

1

II : EXPANDED PROPOSITION - THE Y MODEL

(Y. YU)

GENETIC

EXPRESSION

GEN: 1 ;C

HtANSMISSION

Self actualization

need

Esteem needs

Belongingness needs

/ Parenting

/

needs

Reproduction needs

Sexual needs

— Safety needs

GENETIC

SURVIVAL

Physiological needs

7

III . GENETIC EXPRESSION CHANNELIZED

IN CONTRASTING SOCIETAL SYSTEMS

NEED

LEVEL

OLLECT1VISTIC INDIVIDUALISTIC

SOCIETAL

SOCIETAL

SYSTEM

SYSTEM

Seif

actualization

Contributing

Personal

to community

development

I accomplishment! full potential

Esteem

Primacy of

social esteem

Primacy of

self esteem

Relongingness Cohesion in

relationships

Self interest

through

relationships

Safety

Physiological

GENETIC

EXPRESSION

Unlikely

differentiation

Unlikely

differentiation

GENETIC

SURVIVAL

I

IV : REVISED PROPOSITION - DOUBLE ¥ MODEL

(KUO-SHU YANG)

GENETIC TRANSMISSION

COLLECTIVISTIC

GENETIC EXPRESSION

4-

CSA

Parenting

needs

CE

INDIVIDUALISTIC

GENETIC EXPRESSJCN

Reproduction

needs

CB

CSA: Collectivistic

self actualization

ISA. Individualistic

Self actualization

CE:

Collectivistic

esteem

IE:

Individualistic

esteem

CB: Collectivistic

belongingness

Individualistic

belongingness

1

Sexual

\ needs /

— Safety needs

Physiological needs

•

I

■

■

•

••••

i

Chapter 2

i

Pedagogy

of the Oppressed

A careful analysis of the tcacher-stu'icnt relationship at any

level, inside or outside the '.choc!, reveals its fundamentally

narrarivc character.

This rcia(i-./n:-H.involves a

narrating

Subject (the teacher) and patient, lisk-mng objects (the students).

The contents, whether values or empirical dimensions of reality,,

Paulo Freire

Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos

tend in the process of being narrated to become lifeless and

petrified. Education is suffer.ng from narration sickness.

The teacher talks about reality as if i: were motionless, static,

compartmentalized and predictable. Or else he expounds on a

I

.

topic completely alien to the existential experience of the

Penguin Education

.students. His task is to ‘fill’ the students with the contents of

his narration - contents which am detached from reality, dis

connected from the totality that engendered them and could

give them significance. Words are emptied of their concreteness

and become a hollow, alienated and alienating verbosity.

The outstanding characteristic of this narrative education,

then, is the sonority of words, i:ot their transforming power.

‘Four times four is sixteen; the capital of Para is Belem.’ The

.student records, memorizes and repeats these phrases without

perceiving what four times four -caliy means, or realizing the

true significance of ‘capital’ in t te Jiirmation 'the capital of

Para is Belem,' that is, what Belem means for Para and what

Para means for Brazil.

Narration (with the teacher as mnator) leads the students to

memorize mechanically the narrated content. Worse still, it

turns (hem into ’containers’, intc receptacles to be filled by the

teacher. 'The more completely he fills i!.c receptacles, the better a

teacher he is. The more meekly •he receptacles permit them

selves to be filled, the hcttersiudcris they arc.

Education thus bccom.es an act of depositing, in which the

students are the depositories and ilv icacher is the' depositor.

Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques

E?r-

r

h

B

•

;•

47

and ‘makes deposits’ •.vhfch the students patiently receive

memorize, and repeat. This is the ' banking' concept ofeduca.

tmn, in which the scope of action allowed to the students

extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits.

They do, i. is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or

. cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is

men themselves who are filed away through the lack ofcreati’vity,

transformalior., and knowledge in this (at best) misguided

system. For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, men

cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through

'nygntioa-aud. reHnv^tion^EEu^^

5. The (eacl-cr disciplines and (he students are disciplined

I

i tZl!eaC,’Cr

< VJ I I I Jy J y.

3. The teacher th nks and the students are thought about.

4. The teacher talks and the students listen - meekly.

^<len<S

•7h-IuPh'dCllCr aC,:' -T !i,e S‘'jdenlS hi,Ve lhe illusi011 of acting

tlu ough the action ol the teacher.

6

SJhe teacher chooses :he programme content, and the students

(who were not consulted) adapt to it.

9. The teacher co.nfu.ses rhe authority of knowledge with his

own professional authority, which he sets in opposition to thireedom of the students.

,

continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in the world, with the

world, and with each other.

In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift

bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable

upon (hose whom they consider to know nothing. Projecting

an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the

ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as

processes of inquiry. The teacher presents himself to his students

as (heir necessary opposite; by considering (heir ignorance

absolute, he justifies his own existence. The students, alienated

like (he slave in the Hegelian dialectic, accept their ignorance as

justifying the teacher’s existence - but, unlike the slave, they

never discover that they educate the teacher.

The ro/hc/ili.bertarian educatjon,_On_thc other hand,

hes in its drivejowardsjec oncih'ation.'Education mus'(~bcgin

with the solution of the teachcr-studenTconFradicibon7j)V

reconcil^

so (h';ll bo.’j^7rc'

simultaneously teachers ira/studcnts.

'

This solution is not (nor can it be) found in the banking

concept. On the contrary, banking education maintains and

even stimul..tes the contradiction through the following altitudes

and practices, which mirror oppressive society as a whole:

1. The teacher teaches and the students are taught.

2. The teacher knows everything and the students kno w nothing.

hi£ Cboicc‘

10. The teacher is lhe subject of the learning

process, while the

pupils arc mere objects.

|

I

‘

|

j

I

|.

i

i

It is not surprising that the banking concept of education

regards men as adaptable, manageable beings. The more

students work at storing the deposits entrusted to them the less

lhey develop the critical consc.ousness' which would msult

Iron, then- mtervent.on in the world as transformers of that

«orld. lhe more c.mplute'y they accept the passive role im

posed on them, the more they tend simply to adapt to the world

•is it is and to the fragmented view „f reality deposited in them.

re capacity ol banking education to minimize or annul the

students creative power and to stimulate then- credulitv serves

he interests of the oppressors, who care neither to have the

word revealed nor to see it transformed. The oppressors use

hetr humamtartamt,n to preserve a profitable situation. Thus

•ey react almost mstmcttvely against any experiment in educatmn whtch smnulates the crit.cal faculties and is not content

with a partial vtew m re; lity but ,s always seek,ng out the tics

wmchhnk one point to another and one problem to another

Inoced. the mte.-ests o‘' the oppressors lie in -changing the

umsetousness ol the oppressed, not the situation which oppresses them (Simone re Beauvotr in /m

thC <’PP'CSSCdbe '«! >0 adam to

■h. t stluatton, the more easily they can be dominated' To

"US eih’ 'llc '^Pressors use the banking concept of

...mat,on m uon.ttm. ;ton with a ptttcrnalisuc social action ,

apparatus, w.thm which the oppressed receive the euphemistic (

■!

I

I;

■4r

r

■

i

•

■;’j.

:t

ii

A/Au'j’

^^8

/

I

1 ;

rs

i

i'

■

H.

i

a

' (AriW.-U

'IaaJWJ '^9 /7

to

'yV-Xi

''

m

iJjW,

7 ^(y-r^

C^AVJ'i ■:

title of ‘welfare recipients’. They are treated as individual^

cases, as marginal men who deviate from the general con

figuration of a ‘good, organized, and just’ society. The op

pressed are regarded as the pathology of the hea.thy society,

which must therefore adjust these ‘incompetent and lazy’ folk

to its own patterns by changing their mentality. These mar

ginals need to be ‘integrated’, ‘incorporated’ into the healthy

society that they have ‘forsaken’.

\

The truth is, however, that the oppressed are not marginals,

, arc not'men living ‘outside’ society. They have always been

inside - inside the structure which made them ‘beings for

, o t hers’. The solution is not to ‘integrate’ them into the structye

of oppression, but to transform that structure so that they can

become ‘beings for themselves’. Such transformation, of

course, _wouTd Amjermine the oppressors’ purposcs; hence lheir

utilization.of-XhcJ^nking' concept of education to avoid the

threat of student conscientization.

The banking approach to adult.education, for example, will

never propose to students that they consider reality critically. It

will deal instead with such vital questions as whether R.oger

gave green grass to the goat, and insist upon the importance of

learning that, on the contrary, Koger gave green grass to the

rabbit. The ‘humanism’ of the banking approach masks the

effort to turn men into automatons - the very negation of their

ontological vocation to be more fully human.

Those who use the banking approach, knowingly or un

knowingly (for there are innumerable well-intentioned bankclcrk teachers who do not realize that they are serving only to

dehumanize), fail to perceive that the deposits themselves con

tain contradictions about reality. But, sooner or later, these

contradictions may lead formerly passive students tn turn

against their domestication and the attempt to domesticate re

ality. They may discover through existential experience that their

present wayoflifeisirreconcilablewiththeirvocation to become

» fully human. They may perceive through their relations with re

adily that reality is really a process, undergoing constant trans-

'' fomdtiQnt If men arc searchers and their ontological vocation

is humanization, sooner of later they may perceive the contra

diction in which banking education seeks to maintain them, and

' 7..

42

Zhen engage thumseh-. in the struggle for their liberation.

But the humanist, : . Jutfon.iry educator cannot wait for

this possibility tc mate.'ta.izc. From the outset, his efforts must

coincide with those of the students to engage in critical thinking

and the quest fcr mutual humanization. His efforts must be

imbued with a profound t rust in men and their creative poxyer.

To achieve tEis, he rm.sLbe_.^^a.rt_ner of the students in hjg

relations with thcr.

The banking concept roes not admit to such a partnership

and necessarily so. To risolve (he teacher-student contradic

tion, to exchange the rol: of depositor, prescribcr, domcsticator,

for the role of student among students would be to undermine

the power of oppression and to serve the cause of liberation.

Implicit in the bard ng concept is the assumption of a

dichotomy between m.?. : and the world: man is merely in the

world, not wii/i the wor.d or with others; man is spectator, not

re-creator. In this vic>% man is not a conscious being (corpe

conscienie)} he is rathe: the possessor of a consciousness; ar,

empty ‘mind’ passively open to the reception of deposits of

reality from the world c; ? ide. For example, my desk, iny books,

my coffee cup, al- the <r ucts before me - as bits of the world

which surrounds me •- .‘•culd be ‘inside’ me, exactly as I am

inside my study right mw. This view makes no distinction

between being accessib;/. to consciousness and entering consciousness. The cistint:. >n, however, is essential: the objects

which surround me arc i.nply accessible to my consciousness,

not located within it. 1 am aware of them, but they are not

inside me.

)i follows logically i.:u:: the bat.king notion of consciousness

that the educator's role to regulate the way the world ‘enters

into the students. H.- 1 isk is to organize a process which

already happens s )on(ai usw, (i, ‘fill’ the students by making

deposits of :nfor:Tiati()i. which he considers constitute true

knowledge.1 Aid since ircn ‘receive’ the world as passive

1. This concept corrcsp;

> to what Sartre calls the ‘digestive1 or

‘nutritive’ concept <»f cd

if-n, ir •.shich knowledge is ‘fed’ by the

teacher Io the sludcats in Hi; tl em 'in*. Sec Jean-Paul Sartre, * Une

idec'tondamcntak. d-. .a

.icnkt-.c. i<,gic de Husserl: rihicniionaliic’

Sifi/aiions I.

i

i

I

5

4

I

4

4

I

I

I

■i

1

•1

■4

■I

50

entities, education should make them

more passive

still, and

adapt them to the world. Tim crh.

.

is the ad.iptcd ma11n■ ,

because he is more 'fit ’ fSFTEe xvo'rld

thiFwHSgnr^ii suited'

)

4

have created and how Iit tl^^y^-^iT.... — C

which (n.1°re.C°mP,etCry.lhe

to th; purposes

wh.ch the dommant mmonty prescribe for them (thereby

depriving them of the right to their own purposes), the more

sdy the minority can continue to prescribe. The theory and

VerhT,

2 edUCati0n serve fhis end quite efficientIv.

Verbafistic lessons, reading requirements,2 the methods for

the L hS l-n0W.,edgC’’ the dis,ance between the teacher and

he taught, the enter,a for promotion: everything in this readvto-wear approach serves to obviate thinking.

The bank-clerk educator does not realize that there is no -rue I

secur.ty m his hypertrophied role, that one must s^k to Z

others m sohdartty. One cannot impose oneself, nor even

merely co-ex.st with one’s students. Solidarity requires true

communication, and the concept by which such an educator is

guides fears and proscribes communication.

Yet only through communication can human life ho'd

meanmg. The teacher’s thinking is authenticated only by the

uthentic.ty of the students’ thinking. The teacher cannot fhink

for his students, nor can he impose his thought on them'

itlcnuc dtmking^ thinkin^tha£ is concerned abom

g«20Uake place in ivory-tow^^rj^Z^3’

IS true that thought has mcan7np"r^i----generated by action upon the wor'd

WhCn

or

jxs xs

c„„no,

Because banking education begins with a

.. i

>■

false undersianding

romm, in rhe Heart of Man, calls ’biophily’ but in-teid

Produces us opposite: •necrophily.

'

J

While life is characrcriZed-by growth in a im-,..

or-.

students.

„„„„ |o,„

P b

10

.

.......................................

do this 10'help'their

51

meclbmical. I he necrophilous person is driven by ihe desire to trans

form tl.e ow.nic into the inorganic, to approach life mechanically

as tf ad i.vtn,, persons were things. . . . Memory, rather than experi

ence; having, rather than being, is what counts. The necrophilous

person can relate to an object - a flower or a person - only if be

possesses it; hence a threap to his possession is a threat to himselfif he loses possession he Joses contact with the world. ... He loves

control, and in the act of controlling he kills life.

Oppression - overwhelming control - is necrophilic; it is

nourished by love of death, not life. The banking concept of

education, which serves the interests of oppression, is also

necrophilic. Based on a mechanistic, static, naturalistic

spatialized view of consciousness, it transforms students into’

receiving objects. It attempts to control thinking and action

leads men to adjust to the world, and inhibits their creative

power.

When their efforts to act responsibly are frustrated, when they

find themserves unable to use their faculties, men suffer. ‘This

suffering due to impotence is rooted in the very fact that the

human equilibrium has been disturbed’, says Fromm. But the

inability to act which causes men’s anguish also causes them to

reject their mipotence, by attempting

djv-J.

■ ■ ■ to..rcstorc ftheir] capacity to act. Buf can^heyVam’rhnw? One

way is to subnriUfl.aixLidenfify with a person,or group h7v^

p-ower: By lhls symbolic participation in another person We'TTen

WFFiTTiru^,,,, mactipg,. whenJocality [they] onlyJubmVibTnd

become a part of those who act.

Populist manifestations perhaps best exemplify this type of

behaviour by the oppressed, who, by identifying with charis

matic leaders, come to feel that they themselves are active and

effective. The rebellion they express as they emerge in the

histoneal process is motivated by that desire to act effectively

fhe dominant elites consider the remedy to be more domination

...and repression, carried out in the name of freedom, order and

social peace (the peace of the elites, that is). Thus they can

condemn-logically, from their point of view - 'the violence of a

strike by workers and [can] call upon the state in the same ' T.

breath to use violence in putting down the strike' (Niebuhr’s

V;

Moral Man and Immoral Society).

I

■

52

53

I

■I

. t--

Jr

11

Education as the exercise of domination stimulates the

credulity of students, with the ideological intent (often not

perceived by educators) of indoctrinating them to adapt to the

world of oppression. This accusation is not made in the naive

hope that the dominant elites will thereby simply abandon the

practice. Its objective is to call the attention of true humanists

to the fact that they cannot use the methods of banking educa

tion in the pursuit of liberation, as they would only negate that

pursuit itself. Nor may a revolutionary society inherit these

methods from an oppressor society. The revolutionary society

which practises banking education is either misguided or mis- ■

trustful of men. In either event, it is threatened by the spectre of

reaction.

Unfortunately, those who espouse the cause of liberation

are themselves surrounded and influenced byjhe climate which

generaTes the banking concept, and often do not perceive its

true significance or its dehum anizin g power. Pa rad oxica Uy,

‘this very instrumentpjfa)jen£tion in whatThey

consider an effort to liberate. Indeed; some ‘revolutionaries’

brand as innocents, dreamers, or even reactionaries those who

would challenge this educational practice. But one does not

liberate men by alienating them. Authentic liberation - the

process of humanization - is not another ‘deposit’ to be made

in men. Liberation is a praxis: the action and reflection of men

upon their world in order to transform it. Those truly com

mitted to thecause of liberation can accept neither the mechanis

tic concept of consciousness as an empty vessel to be filled, nor

the use of banking methods of domination (propaganda,

slogans - deposits) in the name of liberation.

The truly committed must reject the banking concept in its

entirety, adopting instead a concept of men as conscious beings,

and consciousness as consciousness directed towards the world,

'■‘hey must abandon the educational goal of deposit-making and

-cplace it with ihe posing of the problems of men in their re

lations with the world. ‘Problem-posing’ education,responding

to the essence of consciousness - intentionality - rejects com

muniques and embodies communication. It epitomizes the

special characteristic of consciousness: being conscious oj', not

only as intent on objects but as turned in upon itself in a

.

Ja-sperian ‘split! - cnn-jciousncss as consciousness o/consciousness.

_Libera^c<h)cim2n consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of jnformafio:-. Jt is a learning situation in which the

cognizable object (far from being the end of the cognitive act)

intermediates the cognitive ac:<>rs - teacher on the one hand and

students on inc oilier. Accordingly, the practice of problem

posing education first .d’all demands a resolution of the teacher

student contraciction. Dialogical relations - indispensable to

the capacity ol cogmn-.c actors to cooperate in perceiving the

same cognizable object - arc otherwise impossible.

Indeed, prohlern-pusing education, breaking the vertical

patterns characteristic of banking education, can fulfill its

function of being the practice of freedom only if it can over

come the above contradiction. Through dialogue, the teacherol-thc-students and the studerus-of-the-teacher ccasc to exist

and a new term emerges: teacher-student with studentsleachers. The teacher <s no longer merely the-one-who-teaches

bjH_onewho_is_h mselijaught in dialog^T^The'students ~vho

taught a IsoTeach, They become iohhiv

P1()ccss jn which all grow. In this process,

arguments based on ’authority’ are no longer valid; in order to

function, authority must be or. ihe side o/freedom.’not anahist

it. Here, no one teach..-; anothei, nor is anyone self-taught. Men

teach each other, mediated b:. the world, by the cognizable

objects which in bankim. ecucat.on arc ‘owned ’ by the teacher

(he banking conrept (with its tendency to dichotomize

everything) distinguishes two stages in the action ofthe educator.

During the first, he cog rizes a cognizable object while he pre

pares his lessons in !>;$ study or his laboratory; during the

secund,.he expounds to r is students on that object. The students

are not called upon t. know, but to memorize the contents

nariatcd by the teacher. Nor do thesiudenls practise any act of

cognition, sine;.- the ojjectjov.irds which tfiaf act should h7

y.-rectcd is tliejjr.opern ja_f.jhc tJaZteTTher than Fmedium

jjXE'admhC-CnticaLre:iciUauii_>LhtHhTcachcr and students

Hence in the iiirme of ihe ‘ pre-.ervaIior^FTnKnTTnTIT3^rledge’ wc have a rystem which achieves neither true knowledge

nor true culture.

$;

4

.7

?■:

i

!

I

I

I

i

iI

54

The problem-posing

55

method

does

not

dichotomize the

Sartre. In one - fl’ our culture circles in Chile, the group was

discussing (based on a codification)-5 the anthropological con

cept of culture. I > the midst of the discussion, a peasant who by

banking stand;;: Is was completely ignorant said: ‘Now I see

activity of the teacher-student: he is not ‘cognitive’ at one point

and ‘narrative’ at another. He is always ‘cognitive’, whether

preparing a project or engaging in dialogue with the students.

He does not regard cognizable objects as his private property,

but as the object of reflection by himself and the students. In

that without m.-n there is no world.’ When the educator re

sponded: ’Let'.- say, for the sake of argument, that all the men

this way, (he problem-posing educator co ns (a n t !y re- fo r m.s_.'-i is

on earth were to die, but that the earth itself remained, together

reflections in the reflection of the students. The students - no

with trees, b rds. animals, rivers, seas, the stars ... wouldn’t all

longer docile listeners - are now critical co-investigators in

this be a world?’ 'Oh no,’ the peasant replied emphatically.

dialogue with the teacher. The teacher presents the material to

‘There would be no one to say: “This is a world’’.’

the students for their consideration, and re-examines his earlier

consideralj_QnsjLSdb£.sl uden t s ex press their"ownTThe role of the

lacking the consciousness of the world which necessarily implies

problem-posing educator is to create, together with the students,

the world of consciousness. ‘ I ’ cannot exist without a‘not I’. In

the conditions under which knowledge at the level of the doxa'-.

turn, the ‘not !' depends on that existence. The world which

is superseded by true knowledge, at the level of thcifceavp

brings ccnsciom ncs;s mto existence becomes the. world‘s ifiaT

The peasant wished to express the idea that there would be

Whereas bankingeducation anaesthetizesandinhibitscrcative

consciousness. I once the previously cited affirmation of Sartre:

power, problem-posing education involves a constant unveiling

of reality. The former attempts to inaint.ain.the submersion of

conscience et le monde sont dormes d'un meme coup.'

As men, simultaneously reflecting on themselves and on the

, ■■ consciousness; the latter strives for the emergence of con-

world, increase the scope of their perception, they begin to

sciousness and critical intervention in reality.

'^’'Students, as" (Key are increasingly faced with problems re

direct their observations towards previously inconspicuous

X

phenomena. I lusserl writes:

lating to themselves in the world and with the world, will feel

increasingly challenged and obliged to respond to that challenge.

Because they apprehend the challenge as interrelated to other

problems wiFfiinTldtafcbnlext, not as a theoretical question,

t he resul: i n g co m pre liens io n lends to be increasingly crihcal and

thus constantly less alienated..Their response to the challenge

evokes new challenges, followed by new understandings; and

gradually thestudents conic to regard themselves as committed.

Education as the practice of freedom - as opposed to educa

tion as the practice of domination - denies that man is abstract,

isolated, independent, and unattached to the world; it also

denies that the world exists as a reality apart from men. Authen

tic reflection considers neither abstract man nor the worldwj t hou fmen t but men i hTFTc i r reTaTtonT w ft h t h e worTcT.'1 n I hose

relations consciousness and world arc simultaneous: conscious

ness neither precedes the world nor follows it. 'Lu conscience et

le monde sont dormes d'un meme coup: exterieur par essence a

la conscience, !c monde est, par essence, rclatif a ellc\ writes

.

In perccp’.ion pru >erly so-called, as an explicit awareness [Geiva/jren],

I am turned love rds the object, to lhe paper, for instance. I appre

hend it as being il is here and now. The apprehension is a singling out,

every object laving a background in experience. Around and about

the paper lie hoc ks, pencils, ink-well and so forth, and these in a

certain sense an. ilso ‘perceived’, perceptually there, in lhe ‘field of

intuition'; but -..hilsl I was turned towards the paper there was no

turning in the r > irection. nor any apprehending of them, not even

in a seconda y : nse. They appeared and yet were not singled out.

were not posii.d an their own account. Every perception of a thing

has such a zone "f backgrounrl intuitions or background awareness,

if 'intuiting* already includes the state of being turned towards, and

this also is a ‘conscious experience’, or more briefly a ‘consciousness

of’ all indeed that in point of fact lies in the co-perccived objective

background.

That which l ad existed objectively but had not been perceived

in its deeper implications (if indeed il was perceived at all)

3. See chapter 3. (Translator's note.')

I1

i

I

j

if

57

56

begins to ‘stand out', assuming the character of a problem and

therefore of challenge. Thus, men begin to single out elements

from their ‘background awarenesses' and to reflect upon them.

These elements are now objects of men's consideration, and, as

such, objects of their action and cognition.

1£ problem-posing education, men develop their power, to

perceive critically the way they exist in the world w/A

Tn whiditheyfi r^'t¥emseRSutiey-C.o me.tL-see.the.wo.ddxoTas

Although the dialectical relations of men with the world exist

independently of how these relations are perceived (or whether

of the word) is found in the interplay of the opposites per

or not they are perceived at all), it is also true that the forrn of

manence and chan:'..\ The banking method emphasizes per

action men adopt is2.0

perceive themselves in t~he world. Hence, the teacher-student and

- which accepts neither a ‘well-behaved’ present nor a pre

Hcc^ siTrwTfaneously ph Jhemsefves and

Once again, the two educational concepts and practices

under analysis come into conflict. Banking education (for

manence and becomes reactionary; problem-posing education

determined future •

rcois itself in the dynamic present and

becomes revolutionary.

Problem-posing education is revolutionary futurity. Hence-

it is prophetic oind. a- s.ich, hopeful), and so corresponds to the

historical nature of

. .'.n. Thus, it affirms men as beings who

obvious reasons) attempts, by mythicizing reality, to conceal

transcend themselvc . who m-we forward and look ahead, for

certain facts which explain the way men exist in the world;

whom immobility rept•. sents a fatal threat, for whom looking al

problem-posing education sets itself the task of de-mytbiologiz

the past must only he a means of understanding more clearly

resists

what and who they arc so that they can more wisely build the

ing.

Banking

education

dialogue;

problem-posing

education regards dialogue as indispensable to the act of cog

future. Hence, it identifies with the movement which engages

nition which unveils reality. Banking education treats students

men as beings aware of their incompleteness - an historical

as objects of assistance; problem-posing education makes them

movement which has its ooint of departure, its subjects arid its

critical thinkers.

Banking education inhibits creativity and

objective.

domesticates (although it cannot completely destroy) the i/i-

The point of dep.j tore of -he moyement lies in men them-

tentionality of consciousness by isolating consciousness from the

world, thereby denying men their ontological and historical

sclvcs7~BuTTnce men do not exist apart fron]_the world, apart

vocation of becoming more fully human. Problem-posing

education bases itself on creativity and'stimulates [rue ref.eetion

and action upon reality, thereby responding to the vocation of

rclationshij).^Accordmgly, the point of departure must always

be with mcnjnjhc 'here and now’, w h jch co ns t i t u t es t lie silua-

men as beings who are authentic only when engaged in inquiry

fron}_je;diUL..HK:.am ■.e.r.cnt, tnus^_begm__yvi(h the men-world

;ir- submerged, from which they emerge,

Thdjn which they intervene. Only by starting from this situation

practice, as immobilizing and fixating forces, fail to acknowledge

- which determines their perception of it - can they begin to

mave^.To_do .ihjs. aut lien deal ly they mus.t .perceive their state

men as historical beings; problem-posing theory and practice

_noUis.faLQd.and unalterable, but merely as limiting.- and-there-

take man's-historicity as their starting point.

Problem-posing education affirms men as beings in the pro

_f< ircchallenginiL.

and creative transformation. In sum: banking theory and

i

reality necessitate that education be an ongoing activity.

Education is thus constantly remade in the praxis. In order

andthus establish an authentic form of thought and action.

I

finished character of m.:n and the transformational character of

to be, it must /.•ccrv/;l'. Its ‘duration’ (in the Bcrgsonian meaning

the world without dichotomizing this reflection froQTaction,

!

education as an u.xdus vely human manifestation. The un

astatic reality, but as a_reality in process, in transfonrjttion.

t he students-teachers

!

cess of becoming

.. ui)Cin;:-:;cd, uncompleted beings in and

with a likewise un: ■ -iud rcaiuy. Indeed, in contrasij_o other

animals who are uij : : .bed, bnt not historical, men know :hem

selves to be unfinished; they arc aware of their incompleteness.

In this incorn pie (cm

.md this awareness fie the very roots of

..

Whereas (he banking method diicctly or indirectly reinforces

--

-

■■

■^6-

-

53

t

!

i

men’s fatalistic perception of their situation, the problem

posing method presents (his very situation to (hern as a problem.

As the situation becomes the object of their cognition, the naive

or magical perception v/hich produced their fatalism gives way

to perception which is able to perceive itself even as it perceives

reality, and can thus be critically objective about that reality.

A deepened consciousness of therr situation leads men to

apprehend that situation as an historical reality susceptible of

transformation. Resignation gives way to the drive for trans

formation and inquiry, over which men feel themselves in

control. If men, as historical beings necessarily engaged with

other men in a movement of inquiry, did not control that move

ment, it would be (and is) a violation of men’s humanity. Any

situation in which some men prevent others from engaging in

the process of inquiry ts one of violence. The means used are not

important; to alienate men from their own decision-making is to

change them into objects.

This movement of inquiry must be directed towards humani

zation - man’s historical vocation. The pursuit of full humanity,

however, cannot be carried out in isolation or individualism,

but only in fellowship and solidarity; therefore it cannot unfold

in the antagonistic relations between oppressors and oppressed.

No one can be authentically human while he prevents others

from being so. The attempt to be more human, individualistically, leads to having more t egotistically: a form of dehumaniza

tion. Not that it is not fundamental to have in order to he

human. Precisely because it A necessary, some men’s having

must not be allowed to constitute an obstacle to others’ having,

to consolidate the power of the former to crush the latter.

Problem-posing education, as a humanist and liberating

praxis, posits as fundamental that men subjected to domination

must fight for their emancipation. To that end, it enables

teachers and students (o become subjects of the educational

process by overcoming authoritarianism an.d an alienating

intellectualism; it also enables men to overcome their false

perception of reality. The world - no longer something to be

described with deceptive words - becomes the object of that

transforming action by men which results in their humanization.

Problem-posing education docs not and cannot serve the

59

interests df (he pressor. No oppressive order could permit the

oppressed io he/m to i|’.cstion: Why? While only a revolu

tionary society <■.'.!• curry out (his education in systematic terms,

the revolution;!!>■ leaders need not take full power before they

can employ the method. In the revolutionary process, (he

leaders cannot ■.' Iizc the banking method as an interim measure,

justified on grounds of expediency, with the intention of later

behaving in a miiinely revolutionary fashion. They must be

revolutionary that is to say, dialogical - from the outset.

f?-.) I

f

*■

\ 02)

Approaches to 1 raining

> In ten years time I may have forgotten the content but I will remember the approach.

This section is directed mainly towards trainers. The section sets out four approaches

to training and learning, with their characteristics and their advantages and dijsadvau-

tages. The purpose is to provide an overall perspective for people who have 'training

responsibiliues, and a rationale for die experience-based approach of this manhal.

j

Course trainers may want to offer the material to course members also. If

become familiar with the approaches and their characteristics it will sth! pei^cc.; w .•

their experience of their own course, and will increase their understanding of its

wtTwtology.

Li Ifthe topic is offered to course members, it is best dealt with alter three or fou. wecto.

by which time members will be able to relate it to their own experience or th? course.a |

The information and ideas can be conveyed through a short presentation: do nbt give

I

continuous lecture (see page 158).

-7:

be used to open up the ■

The sshort

____ questionnaire Our Ideas about Training (page 163) can

H

topic beforehand.

The questionnaire is light-hearted] in style, but it will help mepnbers to

mptions about training and the role of thd trainer. |

clarify and question some of their assur

When we consider the education and training of adults as development workers,, we can

ch with advantages and disadvantages. The four ..y

identify four different approaches, ear

„

,

approaches can be illustrated with a simple diagram which has two axes.'

and Practice as the other. The second axis has

The first axis has Theory' as one extreme

- - -------------i

Content as one extreme and Process as the other? The two axes produce tour g

quadrants each representing an approach

approach to training. Please refer to die diagrpi on the

I

I

next page.

ffii Academic

I

6®

In the first quadrant which lies between Content and Theory, the apptoath can be-3

described as ‘academic’. The main tool here is ‘teaching’. The purpose oil acadoinic-^

teaching is to convey information and to pass on theoretical understanding. Ihc..^

characteristic method is the lecture, supported by individual reading and tliekvritin

die wrmng of.

Jam

I

I.

CV<Ud.UUl..uUZ,^.v...

:

2

1. After Rolf P. Lynton and Udai Pareek. Training for Development, Taraponevala,

': or the subject When we observe what a group .s4

2. In training the content’ refers to the substance, the task the topic

focussing on the content When we observe hoj// the group is/J

working at, or listen to what a group is discussing, we are f

working or discussing, we are focussing on the process.

'

156

14

r7 /

i /

J SffWmi-.vfc.'iE

SFf

& iPWgBFMtaw iraryrown

.

Approaches to Training

gays-. The goals arc contained in a syllabus or curriculum. Appraisal is by means of

^exvnninat’ons, usually written and competitive. The principal roles are lecturer or

j teschcr, and student or pupil.

T

Pf(’'

assumes that education is an intellectual process of acquiring knowledge.

‘S iO be Passed from th°se who ‘know’ (the teachers) to those who don’t

'ignorant’. A further assumption is that when students acquire

’bey arc then able to transform it into effective action in the 'real world’.

f«

1.I

4

;‘l||

•f"'

giving atte? Lion

and importance to

Content

Academic

i

Activity

. •C giving attention

pxpnd importance

to Theory

giving attention

and importance

to Practice

jh;

<. .> •

hl

‘‘il

Laboratory

11

n; a

1

'1

Action-Reflection

i

giving attention

and importance to

Process

’ • ! ’ !|;S

The formal education systems, with their schools and universities, fall in this quadrant

These systems are usually individualistic and competitive. Authority and responsibility

. for the learning process and for appraisal lies mainly with the teachers and lecturers.

• The approach is attractive to teachers and lecturers because it ensures they have higher

; status? Furthermore, the process of teaching is predictable, and normally remains

■ within the teachers’ control.

i The approach is useful for disseminating information and strengthening theoretical

; tanking. But on its own it may not lead to better professional’practice or more

effective development work. Too many practising workers attend academic courses,

listen to lectures, acquire a lot of information, pass exams, and gain qualifications —

and then carry on working as before, without any improvement in effectiveness or in

t.'.c quality of their work. The links between academic learning and practice are weak.

Practitioners need an approach to training which emphasizes change in practice.

' i'W

i

w

■f

f

Hii

••i'

one-Ty toT™nStiondeVelOP,,nent

Wh° ''<n0WS''

157

'Vi"aSerS' Wh° d° nOt

and ,h0 ,OP-down

I

1

The principal academic method, the lecture is also ineffiripnr TP

i

•ita. bral, f„

,hm io

±

" J* r,"d' 8“‘

».y onl, «% of wb„ hl„ he„d „,d Wf of Jtas b J * ■

W;

ater. Confucius is supposed to have said, ‘What we hear, we forget.’

■

1

IS Activity

™uvitv°?r

C°,1!Cn'

,r"’r:in ■ ,iCS

Pr!,CticC- ™S aPPxoaEh

If

called

ofte a f ’ j PU''PT 'S l° tC

Impr°Ve Practical skilJs- This is the ^d of learning

often found in traditional societies.

*°

■is x

■“?

■h'“ 'u“s “ * p'™““ s“““" ■»“

»

ow .» *. „„ e„eI1Oo„. An obv,ou, „„pfcwho fam

S •-W

om their parents and grandparents. Another is the young person learning a skill 4 ™

Tvoie3! 1

a"

Practitioner who has the required expertise and experience I'ill

Typtcal learning roles are the apprentice, the novice, the intern, and the Me' " W

method8 .r° “ arC *C master’> the demonstrator, the instructor, and the expert 'Che

?ra mnt o”' h

t pT"10?’ inStrUCd0n’ c°Pying> and Ptactice under supervision

c“cu”6 ““d”“ -

U-;L

I IQ

« mb

Confucius is supposed to have said, What we see, we remember.’ The approach leads T ■

deXn t^b

Pr°CedUreS and eXpertise have b-n expounded o J 1

demonstrated, but it may not go further. It assumes that whatever apprentices hav

V"

eno b

to d

them tQ

not ody

PP^ nces h„

, :

.

job, out also with unfamiliar and i

• •

unexpected challenges. But those who follow and rely

IVilSht toVe0! tinehP-0CedUreS may fmd

the the^'Tending or

me insight to deal with situations outside their previous c

‘

b

experience. And many of the

situations we encounter in development work will be outsidfe

c.de our previous experience,

experience.

t has been said that practice without theory is blind.

sXn^^ itS limitations ‘activity’ is long established and widely recognized as the

voluntaryXXr1"

Staff °f Organi2ations- Much of the training conducted by |

0 -tary development agencies and NGOs follows this approach. One advantage is «

Ut cheap. Another ts that it does not require any specialized training facilities or |

1

i:

p

f

1

O:

Many development Avorkers have been inducted into their work through A.Am.- r- H

rhe work’ “h "1

W‘th Y’’ °r ’-4 how Z does ff' f W

: >. C-’

started b ’ I '

may

the newcom« to ‘get the feel’ of die job and get fib

by resortinv tXr

TX

demands> “d may end up

•

I

Some tra

311

zePe2UnS

P«t mistakes of others

?ome training courses combine the academic with activ.ty, so that the two' 1M

approaches then complement and inform each other.

158

it'

6.1 ApfirocrJic'. h Trenina

/'•third approach emphasizes Process and Theory, and is known as ‘laboratory

.Cl. i-vjig. This is represented in the third quadrant of the diagram.

P,Tl

,|S;

Laboratory

' .The name labota'ory is used because there are parallels with the working of a scientific

'•horatory. One narallcl is the experimental nature of what takes place. Individuals or

r .groups try things out and observe what happens. For example, they may take new

'Tdts. express hidden feelings, practise new roles, experiment with new behaviour, and

ih,-.,. nrc relating to others and how other percci-.’e mem. Another

r.' Tcl ’•.'irl'. .i 1..moratory is the separat’on ot the work trom the rest of the v.oiid.

Ar.er.rion can then be concentrated on the task or process under study, and what is

:?jt rJc- ant can be left outside’. This makes it easier to locus on particular i ’.ctors,

.trace their effects, and draw conclusions.

Another name which is sometimes used is unstructured .

The approach is essentially person-centred and group-based. The task of the group is

• to. observe and study the way the group is functioning while this is actually happen' ing. The task of the individual is to examine his or her own behaviour and personal

. :oie within the group, and the impact that he/she is having on others, again while

• .actually engaged with the group. Attention is therefore on the present moment. This

is often referred to as ‘working in the here and now .

The reference points, and the data for study, come from within the group itself.

Outside forces, back home situations, and formal designations are all left ‘outside’ the

laboratory’. There is little or no external accountability. The learning is the concep

tual understanding and insight which comes from this experience, together with

increased self-awareness, improved sensitivity, and enhanced skills in relating to

others.

• The role of the trainer, typically called a facilitator here, is to help members to focus

on the way the group is working, and on the issues facing the group. He/she also

■ helps individuals and the group to examine and understand experiences within the

group. The ‘methods’ include group dynamics, sensitivity training, personal growth

laboratory, T-groups, community change laboratory, and group relations conferences.

! If the focus is mainly on the working of the group, rather than on individuals, then

rhe dynamics of participation, decision-making, leadership, power, authority and

conflict are all likely to be examined, along with other dimensions. These are all central

issues in any organizational or community setting, and development workers need, nor

only to recognize them, but be able to work with them.

If the focus is mainly on individuals within the group then the members become more

aware of themselves and how they are perceived by others, understand more about

159

' 'f

I

I

T

Tii

■y

y

:'!H

r

• x

.........................

...................

' •

' ■

■•

•

""■•

................... *................................ ....

also central in development work.

The approach assumes that a person’s inner psychological realities are relevant to

learning and to then work in the outer world. Tr makes mow explicit the link between

the assumptions, aspirations, values, etc of the inner world, and die roles, decision

making. leadership, and action of the outer world. It also assnm,-; rl-.ar people can

translate their experience and learning in the •'■•..hoia:, tj.' mu ■ :?-.v wms ot work.iw

when they return home.

’ The learning has a deep and lasting quality, which is often personal to the learner. I he

individual who joins such a training group may be expected to disclose more ol

him/herself, and to receive more feedback, than in other approaches. Feelings are

often exposed. The experience can be exciting and challenging; it may also have

disturbing and even painful moments. Some people say that if learning is to be effective

it should disturb us!

Such training can be difficult to handle effectively, and requires trained facilitators.

Teachers and trainers who are used to a more conventional academic approach may

find this approach open-ended, unpredictable and complex.

This kind of training is usually offered to those who want to increase their own

awareness and improve their own skills. It is particularly helpful in situations and

professions where there are systemic disparities in power, such as community and

development work, social and youth work, prison and probation services, and manage

ment. Many development workers who have experienced such training have gained

important insights and have greatly improved the quality of their work with others. It

is especially useful for those with responsibility for training.

|W Action-Reflection

>

rr/yif

B

W'

■■■■•

lj

;I

sitW

If

i

IIit

a

i|

fl

ii

Ps»3£jc*jEy:i

Finally there is the quadrant which lies between Process and Action. Training here

|

consists mainly of providing course members with alternating opportunities for ‘acdon

and reflection’. They experience an action, and then they reflect on it. They work at a task

which is related to some aspect of development work, and then they think about the

process. What happened? How did it happen? Why did it happen? How is it relevant?

?, ,

||

I

I

BJ

The approach is also referred to as experience-based or ex[iperiential. Learning arises

from the direct experience of the course member, but that experience: has to be |||

nalyzed. Simply doing something is not enough. We need to look at ourselves in the

V:; I.

P

The basic tool for the approach is alternations which reinforce learning. Action is T

we eat but which passes through our system undigested — it does us no good.

with individual work, personal involvefollowed by reflection, group events alternate

?

160

1

F’’: I

£

.

.*r.r

■■

W

’

-

■

-.... ---- --------------------------

0. / Ap{)rnach's !;> Training

■'t

“rnaCes with lniP^sonal analysis and input. We

move between the specific

ife r S,ner‘" We ■' romerhiog a„d then [aJk abput it,■ and vice versa. We

12“ . .................. <l“p<'’“v.-d„„d„,emdai

: by putting it into

— v.ieory

pl"

““

”™b“

...thev

T..

have just

jTPt had and rhe

'■

’ey have

■'X Z

Z •WCCS

up supporting and interactive roles as much

ng opportunities, facilitators,

-.J course

......

:

....... .

own experi-

„d ™8te. Th.

p[ora, „ „.ope„^ ”pl”“ » “ s haring

.1 ■» W.«ch ,!slTO! th„ ,„u„g „d ,

_

<j- >7- attitudes,

: J as knowled^'

■'iX 15 1101 for knowing more, but for behaving differently.’5

§ A climate in the

group Wh,ch euoormges explo,,^ „d

thinking, is more important than

J.y in development work are

j - b„ipmm

f

dive™n,

"Z1" ””nd

with many Udons. Whafto ^n

TaT

co think/

h,nk 15 taken to be a

“ UnderStand and d-'

potent learning than how

The learning from this approach i

is often deep. Confucius is supposed to have said

What we do, we know.’ Research

> suggests that we remember 80—90% of what we

discover and do for ourselves.

I

-

?

process; greater

relationships;

•.....

listening and

into the dynamics nfnntnnnm

j

• • ’ conthct’ and change; a clearer insight

participation. Such outcomes LTdem^0^^ dn; a?d an lncreased commitment to

subversive.’

‘ dcmocraac> developmental, and — to some —

i. 4. Lynton and Pareek. page

I £““aX;"""",r“ •*—- —■

161

Th= dIc ■“ “ - •

It is the events and methods which contributed to

are included in this manual.

sz:

the action-reflection approach that

> .. the action and rcjlection method has emphasised our own nJeehngSj behejs, opinions, slrenglhs

and weaknesses. This method increases creativity and self confidei

'.nee.. I(. addresses the iv/iole human

being...

> .\r0t a day has passed without some exercise, simulation, role play case study or mih f,//

course by refection and shanng. Yes, by now we all refect in our Lp J ertLedhs^o