TUBERCULOSIS

Item

- Title

- TUBERCULOSIS

- extracted text

-

RF_DIS_5_PART_1_SUDHA

TUBERCULOSIS

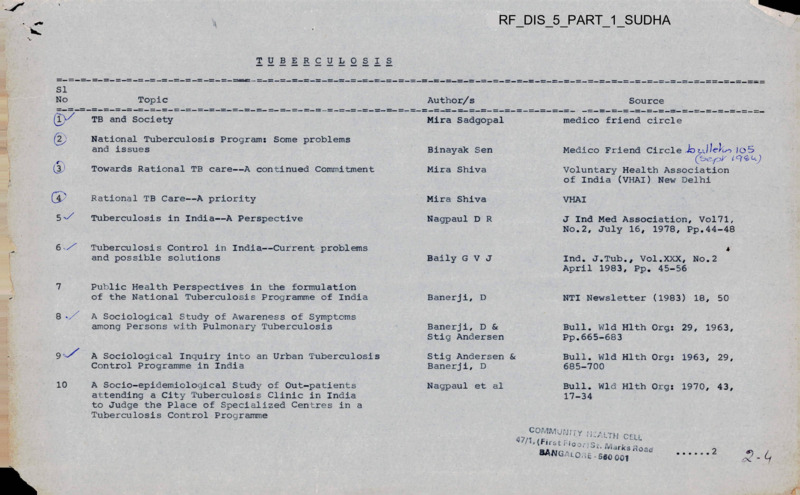

SI

No

(2)

(3J

7

8 •

Topic

Author/s

Source

TB and Society

Mira Sadgopal

medico friend circle

National Tuberculosis Program: Some problems

and issues

Binayak Sen

Medico Friend Circle Jo

Towards Rational TB care—A continued Commitment

Mira Shiva

Voluntary Health Association

of India (VHAI) New Delhi

Rational TB Care—A priority

Mira Shiva

VHAI

Tuberculosis in India—A Perspective

Nagpaul D R

J Ind Med Association, Vol71z

No.2, July 16, 1978, Pp.44-48

Tuberculosis Control in India—Current problems

and possible solutions

Baily G V J

Ind. J.Tub., Vol.XXX, No.2

April 1983, Pp. 45-56

Public Health Perspectives in the formulation

of the National Tuberculosis Programme of India

Banerji, D

NTI Newsletter (1983) 18, 50

Banerji, D &

Stig Andersen

Bull. Wld Hlth Org: 29, 1963,

Pp.665-683

A Sociological Study of Awareness of Symptoms

among Persons with Pulmonary Tuberculosis

/O'S

4

9 '■

A Sociological Inquiry into an Urban Tuberculosis

Control Programme in India

Stig Andersen &

Banerji, D

Bull. Wld Hlth Org: 1963, 29,

685-700

10

A Socio-epidemiological Study of Out-patients

attending a City Tuberculosis Clinic in India

to Judge the Place of Specialized Centres in a

Tuberculosis Control Programme

Nagpaul et al

Bull. Wld Hlth Org: 1970, 43,

17-34

COMMuTJj Ty 'h’ALTH CELL

(First Hoar)St. iVtarks Road

BANGALORE - seo ooi

2

2

SI

No v

Topic

Author/s

Source

11

Tuberculosis Situation in India—Epidemiological

Features

Chandrasekhar, P

& Kurthkoti, A G

National Tuberculosis Institute

Bangalore

12

Epidemiological Data of Tuberculosis

Seetha, M A

National Tuberculosis Institute

Bangalore

13

Tuberculosis in a rural population of South India:

a five-year epidemiological study

National Tuberculosis

Institute, Bangalore

Bull. Wld. Hlth. Org: 1974, 51,

473-488

14

Tuberculosis in a Rural Population of South India:

Report on five surveys

Chakraborty et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXIX, No.3,

July 1982, Pp.153-167

Incidence of sputum positive tuberculosis in

different epidemiological groups during five

year follow up of a rural population in South India

Gothi et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXV, No.2

April 1978, Pp.83-91

16

Prevalence, incidenceand suspect cases of

tuberculosis in a rural population of South India

Krishna Murthy, W

NTI Newsletter (1982) 19, 75

17

Tuberculosis Mortality rate in a South Indian

Rural Population

Chakraborty et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXV, No.4,

October 1978, Pp.181-186

18

Distribution of tuberculosis

infection and disease in clusters of rural

households

Nair SS et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XVIII, No.l

Pp. 3-9

Interview as a tool for symptom screening in

pulmonary tuberculosis

Radha Narayan et al

National Tuberculosis Institute,

Bangalore

19

3

3

■s=

SI

No

Author/s

Source

Srikantaramu et al

Ind. J. Pub. Health, Vol.XX,

No.l, Pp>3-8

Symptom Awareness and Action Taking of Persons

with pulmonary tuberculosis in rural communities

surveyed repeatedly to determine the

epidemiology of the disease

Radha Narayan and

N Srikantaramu

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXVIII, No.3,

July 1981, Pp.126-130

An operational study of alternative methods of

case finding for tuberculosis control

National Tuberculosis

Institute, Bangalore

Ind. J. Tub. Vol.XXVI, No.l,

January 1979, Pp<26-34

23

Evolution of the National Tuberculosis Programme

Gothi, G D

NTI Newsletter (1981) 18, 22

24 v/

District Tuberculosis Control Programme in

Concept and Outline

Nagpaulj D R

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XIVf No.4

Pp.186-198

Tuberculosis Control in Primary Health Care

Radha Narayan

J. Com. Dis.14(3):189-191, (1982)

A study of tuberculosis services as a component

of primary health care

Radha Narayan et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXX, No.2

April 1983, Pp.69-73

Primary Health Care - Evolution in India

Part II : The roots

Radha Narayan

NTI Newsletter (1982) 19, 71

Aneja et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXVII, No.4

October 1980, Pp.158-166

Topic

rrang"

20

21

25 '

27

28

An Operational Model of the District

Tuberculosis Programme

Feasibility of involvement of the Multi purpose

Workers in case finding in District Tuberculosis

Programme

4

4

SI

No

Topic

29

Training for Multi Purpose Workers in

District Tuberculosis Programme

Author/s

Source

Anej a K S &

Srikantan K

NTI News Letter (1980) 17, 78

30

Case-finding by microscopy

Nagpaul et al

WHO/TB/Techn. Information/68.63

31 \/

Potential Yield of Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Cases by Direct Microscopy of Sputum in a

District of South India

Baily et al

Bull. Wld Hlth Org. 1967, 37,

875-892

32

Tuberculosis—Case finding (summary)

Toman, K (WHO)

Geneva

Tuberculosis Case-finding and

Chemotherapy

33

Priority to sputum positive cases under

NTP—Rationale

Jagota, P &

Anej a K S

National Tuberculosis Institute,

Bangalore

34-^

The BCG Story

Mira Shiva

VHAI

35

Present Status of Immunization against

Tuberculosis (Review Article)

Baily G V J

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXVIII, No.3

July 1981, Pp.117-125

6

The efficacy of BCG Vaccination - A brief

Report of the Chingleput BCG trial

Baily G V J

NTI News Letter (1980) 17, 108

37

Chemotherapy in National Tuberculosis Programme

Anej a K S

NTI Newsletter (1982) 19, 58

38

Drug Regimens

National Tuberculosis

Institute, Bangalore

Karnataka State Tuberculosis

Association, 3 Union Street

Bangalore

39

The problem of drug resistance under conditions

of drug chemotherapy

Baily GVJ &

Gothi GD

Proceedings of the 9th Eastern

Region Tuberculosis Conference

& 29th National Conference on

Tuberculosis & Chest Diseases

held in Delhi, Pp.367-371

5

V

5

SI

No

Topic

Author/s

Source

40

Short Course Chemotherapy in National

Tuberculosis Programme

Aneja K S

NTI News Letter (1979) 17, 43

41

Short Course Chemotherapy - Retrospect and

Prospect

Anej a K S

National Tuberculosis Institute,

Bangalore

42

Some Practicable short-course drug

regimens for chemotherapy of tuberculosis

National Tube culosis Institute,

Bangalore

43

Collection and consumption of self-administered

antituberculosis drugs under programme

conditions

Gothi et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XVIII, No.4

October 1971, Pp.107-113

44

Some observations on the drug combination of

INH + Thiacetazone under the conditions of

District Tuberculosis Programme

Gothi et al

Ind J Tub., Vol. XIV, No.1

December 1966, Pp.41—48

45

A concurrent comparison of an unsupervised

self-administered daily regimen and a fully

supervised twice wekly regimen of chemotherapy

in a routine outpatient treatment programme

Baily et al

Ind. J. Tub., Vol.XXI, No.3

July 1974, Pp.152-165

46

VHAI1s Role in TB care

VHAI

VHAI New Delhi

47

Voluntary Agencies and India’s National

Tuberculosis Programme

Debabar Banerji

VHAI New Delhi

48

Tuberculosis Special Issue

Health for the Millions (VHAI)

Vol X No.2, April 1984

6

I

</

1

r

■v

i

6

SI

No

Author/s

Topic

Source

= -=

49

What you should know about Tuberculosis

The Tuberculosis Association of

India, 3 Red Cross Road

New Delhi

50

Beat Tuberculosis

The Tuberculosis Association of

India and the Karnataka State

Tuberculosis Association

51

Diagnosis/ Treatment and Prevention of

Pulmonary Tuberculosis for General

Practitioners

The Tuberculosis Association of

India, 3 Red Cross Road

New Delhi 110001

52

Lectures on Tuberculosis for General

Practitioners

53

Blue Print for Tuberculosis Control in India

54

Planning of Research Studies (some general

considerations)

55

National Tuberculosis Program - Relative merits

of enhancing the efficiency of different

components of the treatment programmes

56

Effect of Treatment Default on Results of

Treatment in Routine Practice in India

Pamra, S P

The Tuberculosis Association of

India, 3 Red Cross Road

New Delhi 110001

-doNair S S

Ind J Tub Vol XVI, No.2,

April 1969, Pp.37-41

Ind. J. Tub., Vol., XXX, No. 1

Banerji, D

Proceedings of the XXth

International Tuberculosis

Conference (1969), Paris:

International Union against

Tuberculosis

J>.s

^0

COMMUNITY hTALTH

CELL

47yl-(^tF,00r)St.1War({3fioad

BAIJGA103E - 560 001

III

medico friend

circle

bulletin

MARCH

TB

I

1985

AND SOCIETY

Preamble

It is the first time in the last eleven years since

our inception that mfc has taken up a single dise

ase entity for discussion at the annual meet.

The disease selected—Tuberculosis'—was particu

larly relevant because of mJany reasons:

i. To begin with there is greater understanding

today of the multifactorial aetiology of the disease

where social factors more than biological are known

to have a significant impact on incidence, preva

lence, spread, diagnosis, m'anagement and control;

ii. Secondly unlike most of the national pro

grammes in India the NTP has developed on crucial

sociological perspectives derived from* relevant

field studies;

iii. In its approach in terms of integration with

general health services, choice of appropriate investi

gative technology, alternatives in chemotherapy and

other aspects it has shown a greater people/patient

sensitivity than most other programmes and a signi

ficant shift from the dependence on the industrial

aspects of medical care;

iv. Inspite of these salient features the case

finding and case holding performance is far from

satisfactory and these have becom'e a matter of great

concern for TB programme organisers and decision

makers,

v. The 1CMR/ICSSR Report while analysing

the drug situation in the country has highlighted the

shocking state of availability of anti-tuberculosis

drugs ('one third of minimal requirement’) when

vitamins, tonics, health restoratives and digestives

are being produced in ‘'wasteful abundance”;

vi. By its inclusion in the 20 point programme

the government has endorsed its relative importance

in the health scene of the country though whether

this step is part of a 'populist rhetoric’ or a nati

onal commitment towards control of the problem,

only time will tell.

It is in this context that the mfc decision to

relook at the whole situation of the TB problem and

its control in India as an exercise for 1984-85 is

significant.

Scope and Focus

The meet of over 110 friends from various

diverse backgrounds (ref mfcb 110 Feb 1985) with

its intensive small and large group discussions

highlighted that the subject was too large and too

important to be tackled in 16 hours of discussion

ano that rather than expecting a meaningful criti

que of NTP to emerge from So diverse a group —

what would really be more realistic would be to

accept the annual meet discussions as the initiating

of a process of critical analysis. This would be

followed up by further study, small group work and

field evaluation through 1985 from which would

hopefully emerge an mfc perspective on the problem.

This sense of realism was forced on the group after

the first session on “Expectations of the Meet” in

which participants were asked to raise issues and

questions for discussion.

Expectations of the Meet

The exercise identified a phenomenal range of

problems far beyond the scope of the meet:

1. Need to understand the organisational

structure and implementation of NTP and the devi

ations from ideal in the actual field situations.

2. Need to identify issues on which we should

put pressure on policy makers.

3. Need to discuss the range of non-pulmonary

tuberculosis and how it is viewed by the NTP.

4. Need to discuss childhood TB and how it is

viewed by NTP.

5. Need to study how NTP actually operates

at the PHC level and what are the components of

the services actually available at the community

(village) level.

6. How do non-allopathic systems view TB as

a problem1?

INSIDE

TB — SEP strategy

2

Towards a relevant

TB Control Programme

3

Subgroup reports on TB

5

AIDAN mfeeting report

7

involve other non health sectors like the education

department etc.?

30. Why is awareness building given such low

priority? Why is there no definite, researched and

evaluated communication strategy integrated into

NTP?

During the discussions at the meet some of

the above expectations were debated in greater detail

and some were not, either due to inadequacy of in

formation or time constraint. We report some of

the key areas of discussion. Decisions for follow

up study or action are given at the relevant places

in brackets. Wherever participants have commit

ted themselves to specific action this is indicated.

Where it is not indicated it means that volunteers

from members/subscribers/readers are welcome to

get involved. We also welcome any information, ,

perspectives, opinions on any of the questions

listed (get in touch with mfc office immediately).

7. How far can TB be considered an occupa

tional health problem because greater susceptibility to it after certain types of occupational ex

posure are well known?

8. Knowledge of cost factors in the range of

alternative regimens of chemotherapy.

9. Data on drug production, distribution and

availability in relation to total estimate of patients

and in the context of recommended drug regimes.

10. Identify genuine constraints in NTP

and false limitations accepted by programme plan

ners.

11. Identify genuine constraints and false limi

tations in TB programmes of voluntary agencies.

12. How far is TB actually integrated with

. general health services? Is there need for greater

integration or greater identity?

13. To develop guidelines for patients who

have already received treatment before — be it

inadequate or inefficient.

14. Role of voluntary agencies in NTP.

15. Role of private practitioners in NTP. Why

are they excluded from the plan?

16. Understanding of the social stigma' associ

ated with the disease and its effect on case finding

or holding and the measures to combat it.

17. The effects of the over emphasis and pres

sures of the family planning programme on PHC

functioning as well as NTP at PHC level.

18. What is the 7th plan policy decisions on

TB programme?

19. TB and its relation to other respiratory

diseases occuring in certain occupational environ

ment.

20. How can NGOs support/complement/supplement NTP of government?

21. What is the method of collection, analysis,

feed back of statistics of NTP from field level?

What is the method of feed back from the centralis

ing agency to the peripheral delivery system?

22. Role of para medicals and community health

workers in NTP.

23. What are the legal rights of industrial

workers vis a vis TB?

24. What are the differences between NTP

performance in different states and regions and

the causes for such difference?

25. What are the present efforts in public

awareness building? What are the available media?

In what way can this be further promoted?

26. What is happening about drug resistance

in NTP?

27. In spite of the more holistic epidemiologi

cal understanding accepted today, why is NTPs

perspective severely clinical and curative?

28. Why/how can TB be seen as a social pro

blem to be tackled by society not as a medical pro

blem to be tackled by the health services only?

TB—a socio-economic-political strategy

From the discussions, it evolved that TB con

trol must be discussed in the context of a radical

reorganisation of society towards a more equitable

and just system* where the smallest and most vulner

able person is central and only this can secure some

stability t0 the health and welfare of the people.

In the strategy to achieve this society, all

interventions particularly those at the grass roots

must be through people’s movements and organisa

tions so that demands and decisions are the peo

ple’s free choice. In this strategy the process of

reflection and conscious action

(ie.f education)

is on all fronts: social, economic, political, cultural,

health and countering myths and superstitions; and

seeks to make the person/group/society self reliant

and confident.

Micro level action is primary but also sharply

limited. It must be linked to the wider reality.

Critical collaboration is necessary with people's

movements and wider political action. However,

there needs to be a high critical awareness of the

daneer of ‘over politicisation’ and a danger of the

sabotage of the people’s freedom by political con

flicts.

Within the context of the above perspective

we as a group endorse the following thought cur

rents, action and demands on the SEP front

1. A demand for the reallocation of resources

in the Union Budget. There should be more money

allocated for health and within the health sector,

the rural-urban bias should be eliminated (There is

need to study the funding of NTP, the cost alloca

tion, for detection, drugs^ and personnel as well as

the rural—urban bias.)

2. Each block and PHC should make it public

t0 the people as to what are the available and allo

cated resources for that area. All these resources

should be channelised for the benefit of all people

in a just manner.

3. Occupational (farming, wood gathering,

wage iabour) and seasonal constraints do not allow

the patient (most often an adult in the working age

29. Why has NTP in its planning not cared to

2

sations. People should be the axis when considering

the TB problem. There should not be an undue em

phasis on extraneous agencies such as doctors or

policy makers. Experts should be made answerable

to the people and crucial decisions should be made

by people. Conscious peoples organisations would

lead to socio-economic changes without

which

general health status or even TB situation would

not improve.

11. mfc members have to emphasise that the

socio economic factor is the most important aspect

in TB and for that matter in other communicable

diseases as well. As an organization we should work

to explode the fallacies accompanying the concept

of TB eg. TB Association of India pamphlet on

‘What should you know about Tuberculosis’ lists

poverty, over crowding, unhygienic living conditions

as legends about TB). mfc members who are already •

involved in organising people should develop a net

work for communication.

12. Nutrition, housing, environment at the

working place and amount of leisure determine resi

stance or susceptibility to TB. This means that only

a fundamental change in the socio economic struc

ture of society will help in the control of TB.

13. Whilst demanding a basic structural change,

we should also demand that existing peripheral

services are more effective. Voluntary agencies

should as far as possible not duplicate the effort of

the government.

In fact the government should be made respon

sible for delivering basic public health services

Whilst doing reformist work at grass roots

we

should ~ work towards basic

change

and contribute towards this change ideologically

and organisationally. Alternatives such as low cost

drug production should also be a simultaneous acti

vity.

14. Land reforms, the minimum wages act

and the right to work should be implemented

strictly. In Kerala these measures have greatly help

ed to reduce incidence of TB

15. To bring about the above mentioned socio

economic changes, a political change aimed towards

socialist society is inevitable.

Marie Tobin, Jansaut

Manish:: G’upte, Bombay

group) to go long distances for treatment regularly.

This reduces access to and availability of TB

treatment. Health services especially those for the

detection and treatment of TB should be handled

by para medicals and should reach the villages if

not the door steps of the people.

4. There should be the least dependence on

International agencies for funding and powerful

individuals in the first world who influence develop

ing countries— India is strongly so influenced.

5. Multinational corporations symbolise the

most centralised economic power and therefore they

should not be encouraged particularly in the drug

industry. However the local government interests

are always linked with that of the MNCs and there

fore just removal of MNCs will not eradicate

inequalities.

6. The profit motives of the drug industry

should be strictly monitored and kept in check by

a relevant drug pricing policy.

7. Doctors should correct their own miscon

ceptions about TB. They should realise that the

germ theory is inadequate to eradicate TB. They

should also get rid of the stigma that they harbour

about TB itself. When doctors harbour such stigma

they perpetuate and legitimise it. The stigma that

the doctor harbours reflects the value system that

most of us inculcate during our education which has

a certain bias. This stigma is particularly , com

mon in our attitudes to the poor, caste problem,

leprosy and TB and we need to fight against it.

8. Health problems cannot be solved by doctors

or government health departments. They can be

solved only by creating people’s organisations.

Health is an indicator of the quality of life and

TB should be seen in this perspective. Enhance

ment of health would therefore be much more

guaranteed if health issues are taken up as a part

of wider people’s movements, ie., trade unions,

rural organisations of the oppressed, feminist

groups etc

9. Health education should be aimed at infor

ming people on their right to be healthy and their

right to prompt, effective, inexpensive and safe

treatment when ill. Health education should also

highlight myths related to TB or illness in general

and show how many of them are used by the elite

classes to perpetuate ignorance.

10. A conscious effort at the grass roots level

is necessary to build decentralised people’s organi-

Towards a relevant TB Control Programme

Many of our members are involved at field

level in community health projects organised by

various non-governmental agencies in which TB con

trol is an itegral part. Based on their own field ex

periences and the discussion on the wider social

issues highlighted in the earlier report certain guide

lines were drawn up at the meet for all who are so

involved. These would help to ensure that their

involvement in the field of TB control would be

based on a clearer focus of the social reality in

which the problem exists. It is also an attempt to

internalise the ideas and positive experiences from

various case studies and projects discussed at the

meet.

mfc’s Bhopal intervention — First Report

A report entitled Medical Relief and Research

in Bhopal—the realities and

recommendations,

was presented by an mfc fact finding team at the

Bhopal convention of People's Science, Democratic

Rights and Environmental Protection Groups on 1718 Feb 1985 is available for sale at Rs. 2-00 each.

If you have not already received a copy write to

the mfc office requesting for copies for sale, pub

licity, lobbying and support.

3

2. The time period of each phase and the spac

ing of the drugs depend on factors such as — a.

accessibility to clinic and health centre;

b. infrastructure available; c. cost? d. availabi

lity of drugs; e. stage of disease—serious and nonserious patients; and f. knowledge of patient com

pliance.

Many regimes taking these factors into account

are already recommended from which a selection can

be made.

3. While the regime is being dispensed it is

essential to ensure: a. psychological reassurance of

the patient; b. maintenance of a satisfactory doctor

patient relationship; and c. tactful information to

the patient to increase his ability to identify toxic

effects.

4. The use of supportive therapy such as cough

mixtures etc., should be done in a rational way

taking care not to overuse/misuse supplementary

medication.

1. Broadly speaking TB control programmes

should ensure the following three crucial features:

(a) A link with socio-economic and developmental

activity

(b) A stress on health education and awareness

building at all levels

(c) A commitment to community participation in the

decision making process and project evaluation.

It was felt that many of us who are working in

the field have already a sufficient rapport with the

community and the above could be integrated pri

marily by sensitising ourselves to these issues

Ensuring the above principles, certain specific

recommendations were made for practical imple

mentation during: A. Case Finding/Case Holding;

. B. Drug Regimes; C. Training of Workers.

A. Case Finding/Case Holding

1. There is need to have a rough estimate of

how many TB patients ought to be in the area and

work towards identifying at least that number.

2. Involve health personnel at all levels in the

programme and also all the cadres of the govern

mental health service be they MPWs, CHWs and

Dais. Local indigenous practitioners and traditional

healers should als0 be involved.

3. School health check ups could be done as

an additional focus for case finding as in leprosy.

School teachers and high school students should be

involved in general awareness building.

4. People’s organisations like organisations of

the rural poor, workers, trade unions and other formal

and informal groups in the community should be

sensitised to the problem and involved.

5. Malnutrition surveys and mantoux testing

could be adjuncts to case finding specially for

childhood. TB.

6. Patients who are on regular treatment or

have been cured should be actively involved.

7. The family of patients should be involved

in a positive way in the programe. Once they are

sensitised to the problem in a positive way (rather

than feeling a fear or social stigma) they can be

helpful in making the community aware and also

bringing patients from other neighbouring families

for treatment.

8. The socio economic difficulties of patients

should be assessed and transportation fare and other

small compensation for wage loss etc., should be

provided.

C. Training of Workers

1. First the present knowledge/myths/perceptjons existing in the particular area should be

studied;

2. The people should be taken into confidence

about the programme envisaged by the team and

their participation in decision making ensured.

3. Grass-root workers at village level to be

involved in the programme should be selected by

the community. The selection should be based

among other things on personal motivation and

stamina.

4. The training of grass root workers or CHVs

should be undertaken in appropriate size of the

group (10-15).

5. The content of the training should include

cause of disease; symptoms|: case holding; side

effects of drugs and their management; and motiva

tion of patients.

6. The training should be theoretical along with

practical field training. The methodology should

include.

a. use of available aids, modifying them to make

them more relevant and meaningful to the local

area; b. involve the patient and get him to talk

about his symptoms/difficulties etc., c. reinforce

the learning by continous on-the-job training; d.

older CHVs to be involved in training newer ones;

e. use simple laymen language and avoid technical

jargon; f. concentrate on training to communicate

effectively with patients and the community.

7. Periodic evaluations of the training pro

gramme should be undertaken eliciting feedback

from the CHVs.

8. Similarly an effective supportive supervision

plan and a system of continuing education in which

problems faced in the field are constantly identi

fied and discussed, should be included.

9. The CHVs should be trained to increase

community awareness of the existing NTP and the

availability of effective treatment as a right so that

B. Drug Regimes

There are several regimes which have been re

commended and are available in the existing litera

ture and also promoted by the NTI. Certain basic

principles to be followed before selecting the ap

propriate regimen are:

1. Technical — an intensive phase of two

bacteriocidal drugs and one bacteriostatic drug

followed by a maintenance phase of a bacteriocidal

and a bacteriostatic drug.

4

problem but as effective educators of their patients

in the preventive/promotive aspects of TB.

CHW training: There was a general feeling that

the existing governmental CHW training programmes

gave low priority and emphasis to TB control. The

lesson plans were limited and not integrated with

the rest of the training but given separately at DTCs

and PHCs.

From the experience of participants who were

involved in health projects in which/ training of

CHWs was being undertaken there emerged the

need t0 include certain innovative methods of train

ing to make the CHWs more effective in the field:

These included:— (i) participation of senior CHWs

in training; (ii) learning through doing;, (iii) decent

ralised and localised training; (iv) participatory

methods; (v) use of locally developed or regionally „

adapted AV aids and s0 on.

The group suggested that we in the mfc should

undertake to:

A. Review all available educational materials

and AV aids on Tuberculosis available from govern

mental and non-governmental sources and check

whether the points included in (1) above are present

and whether the social focus as identified in discus

sions exist.

(Anant Phadke agreed to study the TB Associ

ation Pamphlets for a start).

B. Review all available training manuals of

health workers (CHWs, MPWs, HAs) for the im

portance given, content, and focus of teaching of

tuberculosis.

(Marie D’Souza and Minaxi Shukla agreed to

undertake this exercise).

Based on the above two studies recommendations

can be made to policy makers, programme organi

sers and health educationists in the country.

Narendra Gupta,

Prayas.

demands for more regular drug supply and more

effective government health centre services can be

generated. In the absence of such a commitment

the programme of NGOs will become ends by

themselves duplicating the efforts of government

and supporting their inefficiency. In the long run

since voluntary agencies cannot build up parallel

structures to government health services, the catalyst

nature and the 'awareness of rights’ generation

nature of non-governmental voluntary effort should

be promoted.

Mona Daswani, Bombay

Sub-group Report

Para-professional training and community

awareness in TB

1. The objectives of health education of the

community should be to promote an understanding of

the medico-technological aspects of TB, the socioeconomic-political aspects, the rights and responsi

bilities of the patients and people, the common

beliefs and superstitions and demystification of all

aspects of the TB control programme.

2. The responsibility of providing this educa

tion and awareness is the joint responsibility of

government and non-governmental agencies. However,

it seems that one of the main reasons why health

education has not been given top priority in the

NTP is because of the field reality that the existing

services (even if they are geared up) cannot cope

with the increased demands of TB patients, if

awareness becomes widespread. There seems to be

no other reason why even after decades of NTP,

there is still no rationally formulated and researched

communication strategy. TB Associations have play

ed their role but their efforts seem to lack continuity,

technical competence or creativity and are predomi

nantly urban based.

3. Health education efforts should creatively

and competently involve all sections of the commu

nity not only as recipients of awareness building

efforts but also as promotors of ^further awareness.

While focussing on all sections particular interest

should be taken of policy makers, politicians and

community leaders including the functionaries of the

gram panchayat.

4. Improving the communication skills of all

categories of health workers from doctors all the

way to the community health workers should be an

important part of the strategy. At present this is one

of the most neglected areas in the existing curricula.

5. The science syllabus of schools does not

equip children with practical knowledge of common

diseases in India or for that matter for healthy

Sub-group Report

Tuberculosis in Medical Education

The group focussed upon the problem! of produ

cing a socially useful doctor in connection

with

tuberculosis, and the hurdles in the present medi

cal education system that have to be overcome in

this direction. The group itself was a small one and

represented five medical colleges only.

Preamble

1. The basic structure of present day medical

colleges and medical curriculum, propagates a

certain value system, which is predominantly exploitatory in nature;

2. We believe that propagating the attitudes

currently plaguing the fhedical system is a general

process, which involves the attitudes and practices

of faculty members, the expectations of our families

and society, and the ‘traditional’ role of a doctor

3. That medical education is incomplete in

itself, unless the social dimension of disease is stres-

living. There is considerable scope for incorporating

knowledge about TB in the science teaching of

schools. Schools could also become a focus

of creative involvement of school teachers and

children in health promotion.

6. There are a sizeable section of private

practitioners of non-allopathic systems who should

be involved in awareness building. They should be

involved not only in management of TB as a clinical

5

system into the teaching that unless one's clinical

judgement is backed up by labs, one is practising

'poor medicine'.

In fact, making a confident clinical diagnosis

with limited facilities available, is ‘good medicine’.

7. Emphasis is once again laid out on one

therapeutic regimen (ie., SM/INH/TA) for all TB

patients. The concept of suiting TB treatment to a

particular patient's background is not even

touched upon, eg., A labourer who can at

tend a TB clinic twice a week may be offered a

different treatment regimen compared to another

who can attend daily for SM injections. It is sur

prising that in spite of the fact that much of the

research work on alternative regimens of chemo

therapy emanate from India most of these well ac

cepted findings hardly find a place in medical edu- .

cation in the country.

Limitations of the discussion

We in our group were not able to touch upon

the following topics as regards medical education in

tuberculosis.

1. Research in tuberculosis and research prio

rity identification. Whether research and intervention

of a purely technological nature as is currently

practised by the NTI should be pursued or other

issues regarding socio-economic-political factors be

raised as well. Lack of research in communication

and education strategies which is a major lacunae,

also could not be discussed.

2. Continuing education of doctors about tuber

culosis; whose responsibility it is; and the form of

the continuing education programme. The group sug

gest that in light of the discussion a comprehensive

integrated model of teaching of tuberculosis should

be drawn up which can be tried out within the exis

ting constraints of the medical curriculum in India.

As a preliminary process to this effort a much wider

feed back from members in or of different medical

colleges should be obtained on their own experiences

of TB training in their education. This exercise would

establish a continuing link with the annual meet

theme of 1984 and probably could also be

featured in the Anthology of medical education under

preparatibn.

(Ravi Narayan, Vineet Nayyar, and Srinivas Kashalikar agreed to follow up on this along withf other

♦members).

Vineet Nayyar,

Vellore

fsed upon. It is for this reason, that many of our

senior colleagues (even those from NTI) believe in

purely technical or medical intervention for TB

control.

4. Priority of medical education as it stands

today, is directed towards the question of where is

the lesion? or what is the lesion? rather than how

was it caused and why? Our medical education does

not stimulate an average student to ask and seek

answers to social questions.

5. That trying to produce primary care doctors

in tertiary care centres is a major drawback in

itself.

Specific issues

1. We felt that the topic of TB as a disease is

* dealt with in a fragmented way, and is dealt with by

several departments in a medical college. It is for

this reason that the dynamic nature of TB as a

disease is ill understood, and problems in TB con

trol not even perceived. Some of us even passed

MBBS with the notion that TB meningitis is a dif

ferent disease from pulmonary TB and so on.

2. Specialised departments involved in TB

education cater to their own fields (perhaps a part

of the bigger problem of medical education in a

large set up). Attitudes of the faculty members are

built along the same plane. It is for this reason,

that physicians in the medicine departments absolve

themselves of the responsibility to teach about the

social aspects of TB.

3. Clinical medicine is glorified, while preven

tive aspects are looked down upon. Our system is

disease oriented and not health oriented. We look

at cavities and not at patients!

4. “Germ theory” of causation of disease is

propagated and medical intervention only is stressed

during undergraduate teaching. Even PSM depart

ments which undertake instructions in isociological

aspects of disease, have a narrow view of the dise

ase process. Most recommend medical interventions

as a solution quite like their own colleagues in clini

cal departments. Those that go a step further, preach

'better housing, more ventilation apd more food’

without understanding the deeper social aspect of TB.

Social action U almost never undertaken. Even

development projects which encourage incbme

generation schemes and other such social schemes

suppress a more basic question of unemployment in

society and so on.

5. Clinical teaching overemphasises

that

tuberculosis is a common problem and only classi

cal cases are shown to an undergraduate. This propa

gates the myth that being a common disease, it is

easy to diagnose and manage TB. Realities of TB con

trol are never dealt with or discussed so that an

average medical student at the end of his final year

(never recognizes any problems concerning tuber

culosis.

6. There are dictums laid down by clinicians

who teach that investigations are essential to make

a diagnosis. While this is largely true in places

where facilities are available, it introduces a value

An

Appeal

Thousands of innocent Tamils have been ren

dered homeless and jobless by the recent atrocities

and genocidal acts in Srilanka. Assistance, is parti

cularly required in the fields of food supplies, medi

cal supplies, clothing and so on. A group called

MUST—Medical Unit for the Service of Tamils-—

been formed in January 1985. They have requested

l _ '

1__ 1— 1-x__

A 1

us to put an appeal in- the

bulletin. AH

contribu‘

MUST,

tions and support may please be sent to

144 Choolaimedu High Road, Madras 600094,

India.

a

6

All India Drug Action Network

Report of The All-India Meeting on 30th & 31st Jan. 1985

The Drug Action Forum, Andhra Pradesh

had held a convention on Rational Drug Therapy,

which was attended by about 100 delegates. A spe

cial “Drug Information and communication cell” is

being prepared in the 7th Five Year Plan of Andhra

Pradesh and District Drug Advisory Committees

are being set up to advise the' authorities on the

Drugs-issue.

The AIDAN meeting was planned immediately

after the MFC meet. About a dozen groups from

different parts of the country had sent their repre

sentatives. First half of 30th January was spent in

reporting of what different groups have done during

last 6 months. It was nice to know that things are

moving forward on the Drug-Action front in differ

ent parts of the country. Special mention moist be

made of some of the activities:

J

Other groups in different areas have started

activities on the drug-front and building pressure

for implementing Government’s “Ban-Order” was

seen as an activity that would pick up in coming

days.

People io the Drug Action Movement

The Drug Action Forum of West-Bengal is

quite active. It had organized a protest-March to the

U. S. Consulate at Calcutta against the decision of

the American Congress to allow, under

certain

conditions, the export of those drugs which have

been banned in the U. S. The March was very well

attended. They have brought out a pamphlet in

Bengali with the title—“Are medicines meant for

the people or are people meant for medicines?” This

got a very good response. A calendar to spread this

n.essage has also been prepared and is being sold.

A convention was organized in Calcutta on 20th

January and was attended by 400 delegates represen

ting various organizations working in the people’s

Science and Health movements. The convention

adopted demands like: removal of useless, un

scientific, harmful drugs; ban the banned drugs,

reduce drug-prices, abolish brand names...etc.

. Mira Shiva reported that one political partyCPI-ML (Santosh Rana Group) has taken this ban

order as an action-plan and they had approached

AIDAN for relevant background papers. They have

decided to launch in different cities in India, hunger

strike until death, to pressurize the Government to

implement its own ban-order. This news caused a

lot of flutter and all of us would be keenly interes

ted to know what happens to this action-plan? and

its impact.

Steering Committee Report

Dr. Mira Shiva, the co-ordinator, reported

amongst other things about the recommendations

of the Steering— Committee set up by the National

Drug Development Council. These recommendations

have recommended a smaller span of price-control

on the drugs than what exists today. Only 95 drugs

and their formulations will be under price-control

if these recommendations are accepted. The mark

up for the drugs from this priority list is also sought

to be increased.

The KSSP had organized a campaign on oral

rehydration and irrational anti-diarrhoeals in 600 rural

units of KSSP. The KSSP is planning a state-wide

and then a nation-wide seminar on the drug-industry

•—“A decade after the Hathi Committee.”

This will lead to a rise in prices of all drugs—

both the price-controlled drugs and the decontrolled

drugs. This Steering Committee Report does not say

anything about irrational drug preparations in the

market. Coming a decade after the Hathi Committee

Report, this report is retrograde in character and

all of us must oppose it. It is likely to come before

the Parliament in the coming session.

The Arogya Dakshata Mandal has setup a few

“diarrhoea-centres” in Pune city slum's where slum

dwellers are taught the importance of oral rehydra

tion through demonstration. They are also publi

shing a two-volume book on Rational Drug Therapy.

The Catholic Hospital Association of India

(CHAI) held a two-day workshop on “towards a

people oriented drug policy” during its 41st Annual

National convention from 23rd to 26th November,

1984 at Bangalore. About 500 delegates from dif

ferent parts of the country listened to the different

paper-presentations about drug policy in India and

went back with idea of implementing rational drug

policy at least in their own hospitals.

Mira Shiva had convened an emergency meeting

of the Co-ordination Committee of AIDAN in

Delhi on 26th. November to discuss this report and

to give our response to it in a meeting convened on

29th November by the Ministry of Chemicals and

Fertilizers to discuss the “New Drug Policy.” A

note containing our criticism of these recommenda

tions and our positive suggestions was prepared and

Mira Shiva conveyed this to the officials during the

meeting on 29th November.

The Lok Vidnyan Sanghatana is continuing its

campaign against irrational over-the-counter drugs.

The Bombay unit of LVS has m'ade available plain

aspirin, paracetamol, Chlorpheniramine maleate in

a plastic packet along with a proper label, as an

alternative to Aspro, Anacin, Coldarin etc.

Action-Plan:

1. Action-plan in the coming few months

would concentrate on forcing the Government to

7

•

I

RN.27565/76

mfc bulletin: MARCH 1985

implement its own order banning 18 categories of

drugs. Mira Shiva has prepared a list of brands be

longing to these 18 categories of drugs. This1 list

would be improved upon by rechecking it and ear

marking those brands which sell the largest. This

improved list would be printed in thousands and

made available to doctors and Chemists through

different voluntary organizations and they would be.

requested to stop using, selling these brands.

One specific form of action-plan was suggested

during the discussion—After making available, the

list of brands belonging to those 18 categories of

drugs banned by the Govt, the action-group would

go round the city in a Morcha and would request

. doctors to throw away the samples of medicines

bearing these brands into a ‘'Zoli.” Chemists would

also be requested to throw away some medicines as

a token and to return the rest of their stock to the

drug-companies. This “Zoli” containing these

“banned brands” would be publicly burnt at a pro

minent place in the city.

2. A short summary of A I D A N’s criticism

of the Steering Committee recommendations would

be published and different groups should give ade

quate publicity to this criticism in their respective

areas. These recommendations are quite likely to

be kept before the parliament in the coming session

in the form of a New Drug Policy. It is necessary to

raise our voice at that time and compel the Govern

ment to desist from taking this retrograde step. A

summary of the Steering Committee Recommenda

tions and our criticism of it would be available with

Mira Shiva, Co-ordinator, AIDAN, C-14; Commjunity Centre, S.D.A. New Delhi-110016.

?

3. Court cases:

a) E. P. Forte—

Delhi Science Forum has agreed to launch a

fresh case in the Supreme Court about E. P. forte.

b) Depo-Provera—

Dr. C. L. Zaveri, a gynaecologist from Bombay

has filed a case in Bombay-High Court against the

Drug-Controller of India for not allowing him to

import Inj. Depo Provera. Considering the imiportance

of this case, Wpmen’'S Centre of Bombay and

Medico-Friend-Circle, have with the help of the

Lawyer’s Collective in Bombay, applied in the Bom

bay High-Court to be allowed as co-petitioners on

the side of the Government of India. It may be re

called that the Board of Inquiry set uj> by F. D. A.,

U.S.A, has recently given its verdict ruling out

the use of Depo-Provera as a contraceptive in general

Editorial Committee :

kamala jayarao

anant phadke

padma prakash

ulhas jaju

dhruv mankad

abhay bang

editor: ravi narayan

Regd. No. L/NP/KRNU/202

use. This notorious contraceptive is, however,

sought to be imported in India.

A broad-front of different women’s groups and

Science-groups is being formed to oppose the intro

duction of injectable contraceptives in India. Material

about the hazards of these drugs would be circulated

and a public-campaign would be launched against

its introduction.

Besides these co-ordinated efforts, there would

be local initiatives and its hoped that in 1985, the

Drug—Action—work would strike deeper, wider

roots and would create a much stronger public opi

nion against the irrationalities in the drug-^tuation

in India.

—An ant Phadke, Pune

URGENT

We need urgently contributions and donations

to support mfc’s studies/investigations in Bhopal and

publication of our team's reports for professional

and public awareness (cheques/DDs in favour of

'medico friend circle—Bhopal Fund’)

We are counting on you!

FORM IV

(SeeRule 8)

: Bangalore 560034

1. Place of Publication

2. Periodicity of its

publication

: Monthly

: Thelma Narayan

3. Printer’s Name

(Whether citizen of India?)

: Yes

Address

: 326, V Main I Block

Koramangala

Bangalore 560 034

Thelma Narayan

4. Publisher’s name

Yes

(Whether citizen of India?)

326, V Main I Block

Address

Koramangala

Bangalore 560034

: Ravi Narayan

5. Editor’s Name

Yes

(Whether citizen of India?)

326, V Main I Block

Address

Koramangala

Bangalore 560 034

Medico Friend Circle

6. Name and address of

50 LIC Quarters

individuals who own the

University Road

newspaper and partners

Pune 411 016

or share holders holding

more than one percent

of the total capital.

I, Thelma Narayan, hereby declare that the particulars

given above are true to the best of my knowledge and belief.

THELMA NARAYAN

Signature of Publisher

10-2-1985.

Dated

Views and opinions expressed in the bulletin are those of the authors and not necessarily

of the organisation.

Annual subscription — Inland Rs. 15-00

Foreign ; Sea Mail — US $ 4 for all countries

Air Mail : Asia — US$6; Africa & Europe — US $ 9; Canada & USA — US $ 11

Edited by Ravi Narayan, 326, Vth Main, 1st Block, Koramangala, Bangalore-560034

Printed by Thelma Narayan at Pauline Printing Press, 44, Ulsoor Road, Bangalore-560042

Published by Thelma Narayan for medico friend circle, 326, Vth Main, 1st Block,

Koramangala, Bangalore-560 034

^ 2-

■/

•

$2^

;•

TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAMME REVIEW

INDIA, SEPTEMBER 1992

•X

I

“^1

2

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE NO

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

INTRODUCTION

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA

ORGANIZATION OF THE PROGRAMME

CASE FINDING AND DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT

PROGRAMME MANAGEMENT

8.1 CASE NOTIFICATION

8.2 SUPPLIES AND TRANSPORT

8.3 SUPERVISION, MONITORING AND EVALUATION

8.4 EDUCATION AND TRAINING

9. PRIVATE SECTOR

10. RESEARCH

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

11. SITUATION ANALYSIS

12. RECOMMENDATIONS

3

7

8

9

14

19

22

26

26

27

28

30

31

32

33

36

ANNEXES

1.

2.

3.1

3.2

4.1

4.2

5.1

5.2

6.1

6.2

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS

INSTITUTIONS VISITED AND PERSONS INTERVIEWED

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

MAP OF INDIA

PRESENT TREATMENT PRACTICES

GUIDELINES FOR TREATMENT ORGANIZATION

COORDINATION WITH OTHER PROGRAMMES

VOLUNTARY HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS

EPIDEMIOLOGY REFERENCES

GENERAL REFERENCES

37

38

42

49

51

53

56

58

59

60

I

v>

1^17

1752—

3

TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAMME REVIEW - INDIA, 1992

1.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Government of India, recognizing the magnitude of the problem of

tuberculosis, the limited progress achieved by previous control activities

and the expected increase in incidence as a consequence of the HIV epidemic

has decided to give priority to tuberculosis control. In support of this

decision the Government requested WHO to carry out a joint programme review

together with other interested parties, A Steering Group was designated to

coordinate the evaluation of the programme, as a first step to formulating a

project for possible external assistance.

The review of the national tuberculosis programme (NTP) of India was

carried out by a team representing the Government of India (GOT), the World

Health Organization and the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). '

The purpose of the review was to evaluate present policies and practices,

analyze their adequacy to reduce the tuberculosis problem and recommend

organizational, technical and administrative measures to improve the

programme.

The review team analyzed the available documents including

epidemiological data and reports of previous evaluations of the programme,

discussed with officers of major institutions involved in disease control and

in training, and made field visits in three States (Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh

and Tamil Nadu) to assess the programme at the State, District and peripheral

levels.

The burden of tuberculosis in India is staggering by any measure. More

thaN half of the adult population is infected. About 1.5 million cases are

notified every year and there are probably well over 500 000 tuberculosis

deaths annually. Recent trends show that the programme is not having a

measurable impact on transmission and appears to function far below its

potential.

The Government of India formulated the NTP in 1962. The major objectives

were to prevent tuberculosis through BCG vaccination; to diagnose

tuberculosis cases among symptomatics and provide efficient treatment, giving

priority to sputum positive patients; and to implement these activities as an

integral part of general health services. The District was the basic unit for

the NTP organization.

At present, organization of the general health system has been extended

to reach the community level with primary health services, The tuberculosis

programme is integrated into the general health services, and treatment

services are provided at the levels where medical staff is available.

However, the population growth and the proliferation of public health

services has made many Districts unwieldy for supervision by the tuberculosis

team which is based in a single District Tuberculosis Center. Further,

monitoring and training are mainly under the responsibility of the National

Tuberculosis Institute (NTI), the State TB officers playing only a minor role

in these important areas.

&*

_! '

Human and financial resources are provided by GOI and the States to cover

most of the needs of the programme and current policy is to provide free

diagnosis and-'treatment. Currently available data do not allow analysis of

the adequacy or efficiency with which these resources are applied, but

preliminary indications^ and overall TB programme performance point to the

need for substantial improvements. If the programme is to operate as intended

and begin to make a significant impact on the disease, increased funding will

be necessary, emphasizing the need for improvements in programme

effectiveness and efficiency.

*

4

Th« pieswit

structure St national level requires strengthening

to

lea^erihip in redefining policies, effectively assisting States and

supervising prograaae implenientation, retraining staff involved in TB

activities, administering funds, and procuring supplies. The States, which

provide health services, need also to assume their responsibility in TB

programme management, and will require reorganization and training of the

public and non government health institutions involved in TB control.

There is little coordination between hospitals and primary health

institutions in rural areas, and between the different services providing

tuberculosis care in most urban areas, to ensure the management of

tuberculosis patients until cure.

Improvements in the methods and management of case -finding must take

place. In spite of the recognized priority of bacteriological diagnosis and

cure of sputum positive cases to reduce the problem of tuberculosis, a large

proportion of human and financial resources is currently used to treat cases

diagnosed only on clinical and radiological evidence. This practice is common

both to the NTP and to private practitioners and is reflected in medical

college curricula. Bacteriology is not sufficiently used to confirm medical

diagnosis and criteria for initiating treatment in sputum negative cases are

not well defined. As a result of not identifying correctly smear-positive and

smear-negative cases, and newly diagnosed and previously treated patients,

some patients may be treated with inadequate regimens. Sputum microscopy

examinations are carried out with insufficient standards and microscopy

laboratories are inadequately equipped. A TB laboratory network assuring

equipment, training and quality control is not in place.

Rationalization of treatment is required. There are currently too many

alternative treatment regimens and the conventional regimens are of

unnecessary long duration and low effectiveness. Short course chemotherapy

regimens of higher cost-effectiveness are slowly being implemented but

insufficient priority has been given to ensuring effective treatment of

infectious patients, particularly during the initial intensive phase of

chemotherapy.

The present system of recording and monitoring patient identification an

progress during treatment to ensure health service concentration on achieving

cure of infectious cases is seriously deficient. The present system does hot

allow the systematic evaluation of the results of treatment at health

facility or block level. Neither does the registration systetn permit the use

of cohort analysis of patients to assess cure rate a? the main indicator of

programs efficacy.

Drug supplies are occasionally interrupted by lack of timely funding and

of buffer-stocks-. Additionally; the quality of the drugs supplied is not

controlled. The extensive network of multipurpose health workers (MPHW) has

not been sufficiently utilized at the community level to prevent defaulting

and achieve treatment completion.

The present training system relies mainly on the National Tuberculosis

Institute (NTI) courses. The state-level demonstration and training centres

do not function. District Tuberculosis Centres (DTCs) are not adequately

prepared to provide in-service training for dissemination of policy and

standards. It does not make adequate use of training institutions and NGOs at

the State level to transmit current policies and procedures. The curricula,

at medical colleges do not stress the basic principles of TB control and

there is no systematic continuing education for medical practitioners.

5

In spite of extensive national experience in both operational and basic

TB research, alternative methods to correct the extremely low proportion of

cases diagnosed with bacteriological confirmation and of patients completing

the prescribed treatment and cured have seldom been implemented. The

findings of previous programme evaluations have not always been applied to

improve existing programme procedures, nor has adequate use of the results of

research and programme evaluation b.een made.

Nonetheless, the basic strengths of the India TB programme are

considerable. The objectives on which the programme was established thirty

years ago - integration, decentralization, free services, priority to

treatment of infectious cases - are still valid today. They provide a sound

basis for revitalization of the national TB strategy. In addition, the

tuberculosis control programme can relatively easily build on its strengths:

a well defined structure which provides services within general health care

in an integrated manner; a basic managerial unit at District level with

Central and State Governments providing support for diagnosis and treatment;

experienced training and research Institutions; and, a general health care

system extended to the community through multipurpose health workers. An

updated and strengthened programme can expect to reduce the magnitude of the

problem by about half in each 10-15 years with the consequent savings in

lives, human suffering and more effective use of financial resources. This

will require a political commitment, initial investment and strong

leadership, plus the rapid development of an efficient national model to

serve as training ground and provide operational experience to programme

managers at all levels.

recohh£ndatiohs

1.

The structure of the National Tuberculosis Programme should be

strengthened by 1) establishing an apex policy making authority and an

executive task force with managerial functions to impLement programme

reorganization, and 2) upgrading the central tuberculosis control unit in

the Directorate to provide strong leadership and enhance the efficiency

and effectiveness of the National Tuberculosis Programme.

2.

The quality of patient diagnosis should be improved by 1) using three

smear examinations to detect infectious cases among symptomatics before

deciding on patient treatment, 2) ensuring the quality of microscopy with

adequate equipment, training and quality control, and

3) establishing criteria for diegnosis by radiological and clinical

methods.

3.

National and state tuberculosis programme resources should be directed to

ensuring cure of tuberculosis patients, giving priority to infectious

cases of tuberculosis by 1) adopting short-course chemotherapy, 2)

establishing criteria for treatment completion, cure and discharge from

medical care, and 3) ensuring an uninterrupted supply of drugs of good

quality.

4.

The current NTP system of registration and notification should be revised

to emphasize the cohort analysis of treatment results (completion and

cure, transfers, defaulters, died, treatment failures) as the main

indicator of progr^Jume effectiveness.

5.

Policies should be developed to ensure decentralization of treatment

services closer to the community level to enhance access to care and

patient compliance to recommended therapies.

6.

Pilot projects should be implemented at block level to test the

feasibility and results of different technical and organizational

6

strategies to be adopted by the tuberculosis programme -- i.e., to test

the capacity to implement recomaendjitions 2-5 above.

7.

A medical officer or treatment organizer and a laboratory supervisor,

with the necessary transport, should be added to the existing

administrative structure at the sub-district level (about 500,000

population) to strengthen tuberculosis programme management and to

facilitate decentralization of supervision.

8.

Training materials must be developed to reflect the proposed changes in

programme policies and procedures. The current training infrastructure

will need to broaden the scope of its training capabilities by utilizing

state training facilities, medical colleges, public health institutes and

tuberculosis-oriented voluntary agencies to augment training efforts.

International and national training opportunities should be made

available for the different levels of tuberculosis programme staff.

9.

Operational research must be carried out as an integral part of the

revised tuberculosis programme to evaluate programme performance, improve

delivery of services, problem solving and obtain baseline epidemiologicax

information to measure reduction in the risk of infection.

t

7

INDIA - TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAMME REVIEW 1992

2. INTRODUCTION.

A review of the national tuberculoai* progranae was carried out fro*

9/1/92 to 9/17/92 as a collaborative effort of the Government of Indi* (GOI),

the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Swedish International Development

Agency (SIDA). The purpose of the review was to evaluate present policies

and practices, analyze their adequacy to reduce the tuberculosis problem and

retommend organizational, technical, and administrative measures to improve

the programme.

The assessment included:

1.

2.

3.

4.

An overall description of the current programme achievements and

problems,

An analysis of the tuberculosis burdep, the programme resources and

the programme structure,

Specific discussion of the leading Issues facing the programme and

their underlying causes, and

Recommendations for the next steps to improve the programme.

■

i reviewed information relating to the

At the central level the team

magnitude

or

tne

cuoercuxuaxs

problem

in the country and epidemiological

gnitude of the tuberculosis

trends,

structure, policies, technical norms and procedures

trends, programme

programme structure,

relating to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment, drug supply and logistics,

supervision, monitoring and evaluation, education and training coordination

with other programmes and research. Meetings were held with the Min stry o

Health, major referral facilities in New Delhi and voluntary organizations.

Following the review at the central level, the review participants

divided into thfee teams to assess tuberculosis control activities at the

State and District levels through facility visits and interviews with

responsible staff in three selected States (Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Uttar

Pradesh). Then the teams reconvened in Delhi for discussion of t e rev ew

development of principal recommendations for^

findings, conclusions and (

submission to the Government of India, A draft summary of the conclusions

of Health at the end

and main recommendations was presented to the Secretary

of the review.

is attached in Annex 1, and a list of persons

A list of participants

contacted and Institutions visited as part of the review is in Annex 2.

This document summarizes the findings of the review. Background

information on India can be found in Annex 3.1.

8

3. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ADGHS

BCG

CHC

DGHS

DHO

DOT

DTC

DTO

DTP

EPI

GH

GNP

GOI

GP

H

ICMR

IMA

IMR

MBTC

MG

MCE

MO

MOH/FW

MPHW

NGO

NRR

NT I

NTP

PHO

PHI

PPD

R

RC

RI

• RS

S

T

TAI

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR GENERAL OF HEALTH SERVICES

BACILLI CALMETTE & GUERIN

COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTRE

DIRECTOR GENERAL OF HEALTH SERVICES

DISTRICT HEALTH (MEDICAL) OFFICER

DIRECTLY OBSERVED TREATMENT

DISTRICT TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAMME

DISTRICT TUBERCULOSIS 'OFFICER

DISTRICT TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAMME

EXPANDED PROGRAMME OF IMMUNIZATION

GENERAL HOSPITAL

GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

GENERAL PRACTITIONER

ISONIAZID

INDIAN COUNCIL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH

INDIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

INFANT MORTALITY RATE

MASTER BOOK OF TREATMENT CARDS

MYCROSCOPY CENTRE

MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH

MEDICAL OFFICER

MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE

MULTI-PURPOSE HEALTH WORKER

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION

NET REPRODUCTIVE RATE

NATIONAL TUBERCULOSIS INSTITUTE

NATIONAL TUBERCULOSIS PROGRAMME

PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE

PERIPHERAL HEALTH INSTITUTIONS

PURIFIED PROTEIN DERIVATIVE

RIFAMPICIN

REFERAL CENTRE

RISK OF INFECTION

RUPEES

STREPTOMYCIN

SHORT COURSE CHEMOTHERAPY

SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY

STATE TUBERCULOSIS OFFICER

STATE TUBERCULOSIS TRAINING AND DEMONSTRATION

CENTRE

THIOACETAZONE

TUBERCULOSIS ASSOCIATION OF INDIA

TRC

TUBERCULOSIS RESEARCH CENTRE

VHAI

VOLUNTARY HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF INDIA

X-RAY CENTRE

see

SIDA

STO

STTDC

xc

KT

9

4. TUBERCULOSIS IN INDIA

Prevalence of Infection- A number of studies over the past 30 years, mainly

in rural Mnithirn India, have shown the prevalence of infection among

children 0-9 y«ari old to b« between 3.IX and 11.2X (Table 1). In the early

1960s, mor® than 50X of tha population 20 years and older was infected with

ft. tuberculosis

most infections occurred before 15 years of age. By the

late 1960s there wa« no evidence of change in this pattern. Since that time,

there is no clear evidence of substantial changes in prevalence of infection

among children beyond that which might have been expected from secular

trends.

Tabic I. India: Prevalence of tuberculosis infection among un-vaccinated

children 0 to 9 years old and estimated annual Risk of Infection (RI)

RI

Year

Location

Source

4.9X

1.0X

1961

Tumkur

NTI

9.6X

2.OX

1969

Tiruvallore

TRC

10. IX

2. IX

1983

Bangalore

NT!

10.4X

2.2X

1984

Dharmapuri

NTI

3. IX

0.6X

1985

Bangalore

NTI

9.OX

1.9X

1989

Kadambatmur

TRC

11.2X

2.3X

1989

Thiruvelangadu

TRC

6.7X

1.4X

1989

North Arcot

TRC

Prevalence of

infection

----- - ------ 1------------------------------------------

Annual risk of infection. The intensity of disease transmission in the

community is beet reflected by the annual Risk of Infection (RI) which

represents the probability of a previously uninfected individual becoming

infected with tuberculosis during a one year period.

RIs calculated from prevalence studies presented in Table 1 range from

0.6X to 2.3X. These data are difficult to interpret because methods vary

among surveys but they qlearly indicate wide variation within limited

geographical areas and provide no clear evidence of a substantial decrease of

the risk of infection over the last 30 years. This stagnant situation is

substantiated by two recently published studies conducted in rupal areas of

Southern India. One showed that the RI decreased from 1.0X in 1961 to 0.61X

in 1985, equivalent to an average decline of 3.2X per year. The other study

showed no decrease in the risk of infection between 1969 and 1984 (RI of 1.7X

in both y^ars). These results would be consistent with a poorly functioning

programme which Would be creatipg chronic cases of tuberculosis and drug

resistance."

Because most adults were infected in their youth, a small decrease of tne

RI would not have any rapid impact on the prevalence of infection in the

adult population. It is safe to estimate that at least 50X of the population

above the age of 20 years is infected and will remain at risk of disease and

death from tuberculosis for their lifetime. A conservative estimate is that,

currently, the RI for India is still between IX and 2X.

Disease prevalence. The Sample Survey of tuberculosis conducted between

1955-58 remains the major source of information used by the NTP to anticipate

10

the tuberculosis situation in the country. The survey showed wide variations

in prevalence of disease among persons aged 5 years or more (sputum-positive

tuberculosis by smear or culture), ranging from a low of 229/100,000 to a

high of 813/100,000. The overall prevalence was 398/100,000.

In 1960-61 and in 1972-73 surveys conducted by NTI showed the prevalence