WORDS LIKE FREEDOM

Item

- Title

- WORDS LIKE FREEDOM

- extracted text

-

■ Y

fe?;,,

3

..I

v

..

i'

i

./'■

■

J

l

o

.,y

/

• 1.

vg .,'fr,!'-ri':;- \‘: >

M

1!

:-'-^S.,.

.....

ii'-

>

■ T

I

^yi;

Ji

tw

4

.A

y

«

r^\v : ;.'v

JL

I

/---v YA-H

.1

U I HjswWJ^

'n' '‘fi

| A |

Ai

-

a ' >w .■'A

IMF

*ir ;3>

I * '■■ i'\

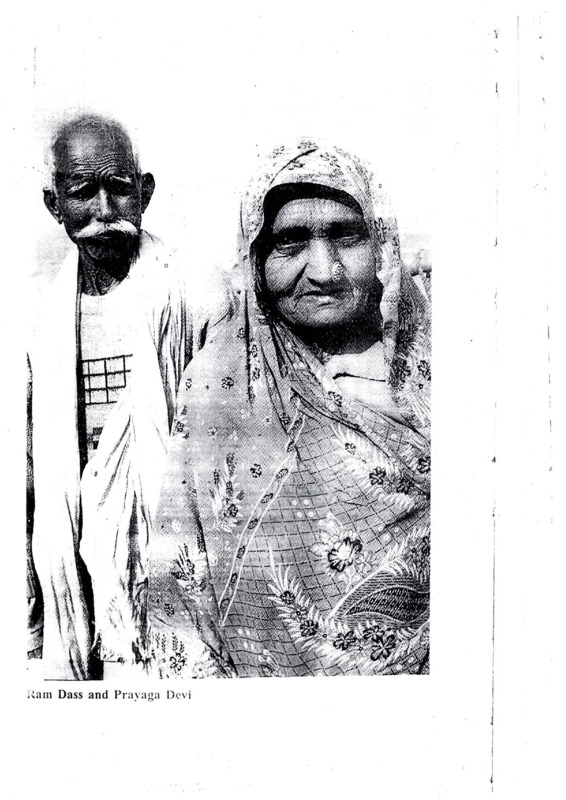

Ram Dass and Prayaga Devi

i

I

i

i

?

. *

.i’

t

1

Words | Like Freedom

"1

.. t

THE MEMOIRS OF AN IMPOVERISHED

INDIAN FAMILY: 1947-97

I

I

o

Siddharth Dube

A

I

I

i

I

I

I

!

HarperCollins Publishers India

I

i

!

HarperCollins Publishers India Pvt Ltd

7/16 Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

‘Siddharth Dube 1998

Published in 1998 by

HarperCollins Publishers India

We gratefully acknowledge Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund

for letting us use the extract on pages 2 and 3,

from An Auiobiogrciphy by Shri Jawaharlal Nehru.

O'ISBN 81-7223-305-1

o

This edition is for sale only in the

Indian subcontinent and South Asia.

Typeset in Times New Roman by

Mesatechnics

19A, Ansari Road

New Delhi 110 002

Printed in India by

Gopsons Papers Ltd

A-14, Sector 60

• Noida 201 301

All rights reserved. No part of this publication ^nay be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any

means, electronic or mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without prior permission of the publishers.

I

To my father,

Basant Kumar Dube,

an incomparably great and good person,

I

i

and to my brother,

Bharat, for so unwaveringly believing in me and in this book.

i

A

l

£ V\

i

I

Q •

O

Contents

■

i

I

t

i

1

A cknowledge merits

Introduction: This Naked, Hungry Mass

2.

The Slaves of Slaves

3.

Bombay I: 1949-52

4. Zamindari Abolition: ‘The vision of

a new heaven and a new earth’

5. Bombay II: 1954-62

6.

The 1960s

7.

The Messiah of the Poor: Indira Gandhi

o

8. Shrinath

o

9. Hansraj

10. Prayaga Devi

11. Puttu

12. Jhoku

13. The Poorest Families

14. The Land Still Belongs to the Richest Families

15. How The Poor are Subjugated, and

How They Fight Back

16. Why Political Democracy has not led to

Economic Democracy

17. Conclusion: The Perpetuation of Mass Poverty

Notes and references

Glossary

Bibliography

Index

xi

1

23

46

56

75

96

108

123

148

160

174

186

192.

212

223

239

255

258

268

270

277

■1

Acknowledgements

l

Many people inspired and supported me - imelleciually, emotionally,

and often in both ways - in the exhausting years I spent researching

and writing. I can only hope that with this book I give to them some

part of what they have given me.

My mother, Savitri, and eldest brother, Pratap, were, as always,

the most admirable, staunch and caring companions I could hope for.

In Baba ka Gaon, Ram Dass, Prayaga DevL Shrinath, Mata Prasad,

Hansraj, Ram Saran and Mata Prasad Maurya, Durbhe and Phoolchand

were by their bravery and goodness constant reminders to me of why

it was essential to vyrite this book.

I owe an enormous debt to Ashis Nandy, Amartya Sen and Scott

Thompson for their eaffy encouragement, without which I would not

have begun this project’

Saleem Kidwai and David Devadas: this book is theirs as much

as mine, for their affection, guidance and help, not least with the

unending translations from Awadhi.

My other dearest friends - Sohaila Abdulali, Tonuca Basu, Sheba

Chacko, Brinda Chugani, Rosemary George, Suzy Goldenberg, Shilpa

Hingorani, Inji Islam, Pichaya Manet, David Morrison, Rosemary

Romano, Sankar Sen, Jai Singh, Sailaja and Tarim Tahiliani, Nilita

Vachani and Kamala Visweswaran - made my life worth living with

their love and generosity. Siddharth Gautam magically appeared joyful and couiageous as always — when 1 desperately missed him,

For their friendship and support, I am indebted to Shoba Aggarwal,

Paul Desruisseaux, Robin Desser, Michael Dwyer, Gautam

•x • Words like

J

freedom

Khandelwal, Leena Labroo, Pankaj Mishra, Sanjay Pradlian, Arundhati

Roy, N.C. Saxena, Helen Saxenian, Jeremy Seabrook, Shashi Tharoor,

I

Indti Vacham. and Jafar and Rajat Zaheer; and to my editors Renuka

Chatterjee and Robert Molteno.

I am also extremely grateful to the United States Institute of Peace

foi the grant that underwrote much of this research, and to the Centre

for the Study of Developing Societies in Delhi for hosting me as a

visiting fellow

.1

I

o

o

/■

I

T ' ■ H

■I

■

o

I

o

1

A

1.

Introduction: This Naked,

Hungry Mass

‘My mental picture of India always contains this naked,

hungry mass. ’

Jawaharlal Nehru

India’s first prime minister

1

*

i

FROM 1919 to 1921, the central districts of Uttar Pradesh province

were swept by a fierce peasant revolt. At the height of the conflict,

thousands of impoverished peasants and landless labourers battled

with zamindar landlords and the British colonial government, allies

in exploiting the peasantry. The scale and ferocity of the revolt was

such that it captured newspaper headlines in distant Delhi, British

India’s capital. The peasants’ demands were radical. They sought

nothing less than an end to their exploitation and oppression: the

beatings and abuse by the landlords and their agents, forced and

unpaid labour, the extortionate rents and illegal taxes that impover

ished them. The province’s British governor-general, apprehensive,

warned of ‘the beginnings of something like revolution’.

*>?

2 • Words like freedom

o

Though the landlords and the British administration were for a

while in retreat, by mid-1921 they had used the police and army to

crush the ‘revolution’. The scores of thousands of landless labourers

and petty tenants w ho had joined or been inspired by the revolt were

once again condemned to brutal oppression and poverty. Their dreams

of freedom evaporated.

Drawn into the revolt on the peasants’ side was the young

Jawaharlal Nehru, already a leader of the Indian National Congress.

Decades later. Nehru wrote about his experience:

As a result ol the externment order from Mussoorie I spent about

two weeks in Allahabad, and it was during this period.that I got

entangled in the Nisan (peasant) movement. . . Early in June 1920

(so far as 1 can remember) about two hundred kisans marched fifty

miles from the interior of Pratapgarh district to Allahabad city

with the intention of drawing the attention of the prominent

politicians there to their woebegone condition. I learnt that these

kisans were squatting on the river bank, on one of the Jumna

ghats, and, accompanied by some friends, went to see them. They

told us of the crushing exactions of the taluqadars, of inhuman

treatment, and that their condition had become wholly intolerable.

They begged us to accompany them back to make inquiries as

well as to protect them from the vengeance of the taluqadars who

were angry at their having come to Allahabad on this mission.

They would accept no denial and literally clung on us. At last I

promised to visit them two days or so later.

I went there with some colleagues and we spent three days

in the villages far from the railway and even from thepucca road.

That visit was a rex elation to me. We found the whole countryside

afire with enthusiasm and full of a strange excitement. Enormous

gatherings would take place at the briefest notice by word of

mouth. One village would communicate with another, and the

second with the third, and so on, and presently whole villages

would empty out, and all over the fields there would be men and

women and children on the march to the meeting-pl ace . . . They

i

b

<

I

Illi —■m

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 3

f

1

A

1

■ I

J

J

•i

E

r

I

were in miserable rags, men and women, but their faces were full

of excitement and their eyes glistened and seemed to expect

strange happenings which would, as if by a miracle, put an end

to their long misery.

They showered their affection on us and looked on us with

loving and hopeful eyes, as if we were the bearers of good tidings,

the guides who were to lead them to the promised land. Looking

at them and their misery and overflowing gratitude, I was filled

with shame and sorrow, shame at my own easy-going and com

fortable life and our petty politics of the city which ignored this

vast multitude of semi-naked sons and daughters of India, sorrow

at the degradation and overwhelming poverty of India. A new

picture of India seemed to rise before me, naked, starving, crushed,

and utterly miserable. And their faith in us, casual visitors from

the distant city, embarrassed me and filled me with a new respon

sibility that frightened me.

. . . Even before my visit to Pratapgarh in June 1920, 1 had

often passed through villages, stopped there and talked to the

peasants. I had seen them in their scores of thousands on the banks

of the Ganges during the big melas and we had taken our Home

Rule propaganda to them. But somehow I had not fully realized

what they were and what they meant to India. Like most of us.

I took them for granted. This realization came to me during these

Pratapgarh visits and ever since then my mental picture of India

always contains this'naked, hungry mass.

In January 1995, three-quarters of a century after the revolt and

almost half a century since India became independent, I travelled to

the area of the revolt in central Uttar Pradesh (UP) province. My

object was to write a memoir of one of the impoverished families who

had fought in that revolt and of their experience in independent India.

I had dreamt for many years of writing this memoir.

I was baffled by why poverty, hunger, ill health and a myriad

other deprivations were still ubiquitous in India nrany years after

Independence. The scale of poverty - the numbers of the ‘naked,

4 • Words like freedom

hungry majs’ — has worsened so much in the past half-century that

in 1997, even by conservative government estimates, the number of

people unable to afford a survival-level diet equals the country’s total

I

population in 1947 of about 350 million. This is the largest group of

impoverished people in the world. Even the proportion of desperately

poor people is not substantially lower in the 1990s than half a century

ago: at about 40 per cent of the population today in contrast to 50

pci cent at Independence. And though many of the most dramatic

I

manifestations of suffering long associated with India - bonded la

bour, large-scale epidemics, famines - have been largely controlled,

this commendable progress is eclipsed by the failure to ameliorate the

chronic deprivation and everyday hunger suffered by several hundred

million Indians.

Equally puzzling to me was the fact that though the country today

'' I

J’:

•I

I

1

i

boasts a huge economy, a major industrial sector, the world’s fourth

largest army and diverse national achievements, India’s record on rais

ing human welfare, ccPmpared to most other developing countries, is

miserable.1 Levels of hunger, illiteracy, excess mortality and other in

dicators of deprivation are today far higher in India than in China, the

Philippines or Indonesia. In 1947 living standards in China were much

the same as in India, but 50 years later were twice that of India’s. And

though 20 years ago severe poverty was as pervasive in Indonesia as in

India, only about 8 percent of the Indonesian population is today abso

lutely pooi, a proportion only one-fifth that of India. India’s scores on

human welfare are worse than every Latin American country but Haiti,

and appear favourable only in comparison to those of the most impov-

I

11

ci ished and strife-torn sub-Saharan African countries.

Why has such acute and pervasive poverty persisted in India

despite decades of fairly rapid economic growth, planned economic

de\ elopment and constitutional commitment to socialism? Did Nehru

betray the impoverished peasants’ faith in him, ‘the new responsibil

ity that seized him during the 1919 revolt? Did the Congress party

abdicate the many promises it made to the poor during the heady days

ol the nationalist mo\ cment ? Why have the sheer numbers of the poor

not ensured that India s parliamentary democracy would work to their

i

h r

■■'1'

B

I

[

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 5

e

I

■ 1

i.

I

)■

!

ii - I

y|" ■

11

■

•!

-;

■'!

■1

■’i

IIp;

P

. r•

f'i

■ i"

benefit? Why has the persistence of mass poverty not emerged as a

central political issue?

Thes<? questions were the beginning of my quest. Once embarked.

I decided to frame the book around the true experiences of an

impoverished family. I wanted to know, and to record for others, what

the poor felt, what they thought, how they viewed the world and their

own situation. History has almost always been written from the per

spective of the wealthy and powerful. Thus, though the poor have long

been a majority of India’s population, they are almost entirely absent

from the annals of Indian history, while there are scarcely any au

thentic records of their views and experiences. Y et, by sheer numbers,

the history of India’s poor is the history of India.

Moreover, very soon the generation of Indians who were adult

at the time of the country’s independence will have died. The unique

history of millions of people will vanish with the passing of this

generation of the Indian poor. They have been participants and wit

nesses at one of the modern world’s most extraordinary junctures: the

constitutional pledge by the government of one of the first colonies

to win independence that all its people were assured’democracy and

freedom from want. It is imperative that their history and their ex

periences in independent India be recorded.

What was the best way to truly represent in a book the views

and reality of the poor? To me, there seemed to be only one

satisfactory combination of methods. The first and most crucial step

was to interview at length generations of one family and to reproduce

. verbatim their life stories. The members of this family would tell

their own histories in their own voices. This was the most honest,

exacting and powerful way I could think of to reflect their views.

Because of my twin convictions that the poor or illiterate understand

their circumstances very well and that outsiders — however em

pathetic or skilled in research methods - can never comprehend

realities radically different from their own, 1 rejected outright the

option of placing myself as an observer-cum-narrator, or of writing

their story in the first person or as a novel. These convictions were

strengthened in writing this book. This family’s testimony is ample

!■

-'1

6 • Words like freedom

proof that they comprehend their situation just as clearly as the

educated and the well-off. And I could not have begun to grasp their

view of life had I not relied on interviewing them and reproducing

their testimony.

The second step was to place this family’s experience within an

analysis which explained two things: first, how the millions of other

impoverished Indian families had fared in this half-century; second,

the most important features and determinants of the many changes

that have affected India in these decades, in politics, agriculture, the

caste system and almost every other sphere. The need to locate this

single family’s experience within this broader context is self-evident.

Focusing on the story of one family ensures richness of detail and a

sense of continuity, but the scale and complexity of poverty in India

is sUch that a single family’s experience can never be ‘typical’. Also,

the situation of this family or of the poor overall cannot be understood

without analysing the patterns and determinants of politics, econom

ics and social change. For instance, just the most obvious questions

about this family — Why were they poor in 1947? Why are they poor

today? - require an explication of a huge range of issues. These

include, at the very least, the colonial political and land-ownership

systems, the caste system, the nature of the Congress party and post

Independence development policies, the depth of the independent

Indian state s commitment to equity and social welfare goals, the

nature of subsequent land reform efforts, the pattern of agricultural

and industrial growth, and national and provincial politics. Hence, this

book melds the singular voices of this family with broad analysis of

India’s ‘political economy’.

In some chapters, the family’s testimony is predominant, in others

analysis. Because the memoir is this family’s, I have not edited their

oral testimony beyond changes needed for effective translation or

clarification. Their views and emphases and criticisms are intact and

do not reflect my biases. If readers feel that this book is one-sided

or too harsh - for instance, in the antagonism towards the upper castes,

the landlords and orthodox Hinduism — they should remember that

its purpose is to mirror an impoverished family’s view of life.

I

!

I

r

I

I .J'

I

I

I

I

I

*

ir;

h

F

' I

1 "■

I

jI

Ih

B R

j-

■J

>

w iiI

HI*

'I

t

'

'1

nt<|

if'’"''

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 7

Similarly, in selecting which subjects to emphasize in the analysis,

I have followed the emphasis placed by the members of the family.

For instance, the issues of land reform and of the landlords’ violence

against the poor are persisting themes because this family considers

them to be central to their poverty.

Ram Dass

Ii

i

)

t

■

W ■o

♦i' ' • ■ I

f-n ■

■

fp

A'

i;it

I O’

AU

’i i

i■ ’ | J

hil. o

II

iA ■

1

r

3

At the centre of this chronicle are Ram Dass Pasi and his village of

Baba ka Gaon in the Pratapgarh district of UP province. Ram Dass

was born in the mid-1920s to a destitute untouchable family of landless

labourers, who were bonded to the village landlords. (The term ‘un

touchable’ is used in this book in references before 1949, when the

term and the social restrictions associated with it were declared illegal

under the Indian Constitution. The preferred term now is scheduled

castes, because these castes are enumerated on a government sched

ule.) Pratapgarh - located in the area of central UP known as Awadh

— was the vortex of the, 1919 revolt.

Ram Dass today, aged about 70, is a convivial man, self-assured

and open in demeanor. Apart from his unusual dark grey eyes, in looks

and dress Ram Dass is broadly similar to other poor north Indian

village men of his age - short (about five feet four), slight-framed,

strong-featured, mustachioed (a thick, carefully shaped bow of white

hair), most often wearing a muddied cotton dhoti, brown kurta, short

sleeveless jacket and cracked leather shoes. On special occasions,

particularly in the evenings, he dons either a yellowish or lilac turban.

Ram Dass’s father was from a village some 20 km to the north

of Baba ka Gaon, called Ranipur, in Sultanpur district, which was

part of the wealthy Amethi landlord’s estate. Baba ka Gaon is

Ram Dass’s nanihal - his mother’s village - but it became his fami

ly’s home because his mother moved back to her parents’ home once

her mother-in-law had died and her husband and father-in-law still

stayed away at work in Bombay for long periods. My father used to

go away for two years at a time and so where was my mother to go

for refuge but to her parents? Ram Dass and his elder sister were born

I

o

4

o

■I

I

h!.u

f//"1'

i

...

^ggs

wi‘

g?;:« ;■. u

■i

■ ?•

f

W?'

-

■K^

i

r

r

/

:■

'

1

'^■-

■

-

:'f

■

I

?■

j

.-!‘h

I

■y..

'■•

'■

•;<

I

«

ft x

iI

bi

I

0

11

■

I

X

4

■Il

11

Ram Dass Pasi

■|

I

r

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 9

I

h

>

I

i

■

• r'jf 1

in Ranipur, the rest of his siblings in Baba ka Gaon. In Bombay, Ram

Dass’s father worked as a labourer at the Khiljee Mills, a cotton

milling factory. He left Bombay in the early 1940s to return to Baba

ka Gaon. He died in 1973, Ram Dass’s mother in 1983.

Ram Dass was the second of five children. Only his youngest

sister, aged about 50, survives. Puttu is married and lives in Dehra

Dun, a prosperous UP town some 700 km north-west. She works as

a labourer in a tea plantation. She is childless.

Ram Dass’s elder sister, Prabha, died at the age of 40. Her

husband and three children live in a village in Sultanpur district. Ram

Dass says she died of some kind of paralysis. We had no money, so

where could we take her for treatment? So it was inevitable that she

would die. There was a doctor in Gauriganj, where she lived, and he

treated her, but these village doctors, what do they know about long,

lasting diseases. At that time no one used to do doctori dawai [West

ern, allopathic medicine].

Another younger sister, Bonda, died at the age of 25. She and her

husband lived in a village adjacent to Baba ka Gaon. She had two

daughters and a son.

Ram Dass’s only brother, Ram Tehel, died of tuberculosis at the

age of 22. When he fell sick, he was in Bombay with Ram Dass,

working as a daily-wage labourer in small factories. Because he was

ill I told him to go back home to the village. I bought him as much

medicine as we could buy. But he just withered away. Only one of

Ram Tehel’s children survived, and on his father’s death this son was

brought up by Ram Dass and his wife. Ka'alu, the son, now about 40,

works in a welding shop in Faridabad, a large industrial town on the

outskirts of Delhi. Kaalu has three daughters and a son, who live in

Baba ka Gaon with his wife.

There are 18 people in Ram Dass’s immediate family today,

including his wife, two sons and their wives, eight grandchildren and

four great-grandchildren. Ram Dass’s wife, Prayaga Devi, is a few

years younger than him. His sons, Shrinath and Jhoku, are aged,

respectively, about 45 and 35. The entire family lives in Baba ka

Gaon, apart from Jhoku, who works in Dehra Dun.

O'

o

I

■I1

1

'! ;v'': |w

10 • Words like freedom

1 'J)/WB'

!

■■''

-' i

o

Ram Dass says: My first child was Shrinath. I had 12 children

altogether, 1 girl and 11 boys. Apart from Shrinath and Jhoku, they

all died after reaching 4 or 5 years of age. The child in Dehra Dun,

Jhoku, is about number 8. The last two died at about the age of 7.

They died ofsmall-pox. They didn 7 survive even though we gave them

a lot of medicines. The earlier ones - I’m not a doctor, so how can

I tell what they died of? It was just not in my destiny that they live.

The history of Ram Dass’s family is inextricably tied to the

village of Baba ka Gaon — current population 500 — in the north-west

corner of Pratapgarh district. This is the heart of the vast Gangetic

plain, and at one of its meandering loops the Ganga passes just 60

km from the village. Baba ka Gaon is marked only on detailed maps

of Pratapgaih district, but is located nearly equidistant between

Lucknow, UP’s capital, and Varanasi, both about 150 km distant.

From eithei city, it today takes about five hours by bus to reach the

iiitted dirt track that leads to the village. Pratapgarh’ the district

capital, is two hours away. More convenient are the railway stops at

Amethi or Gauriganj, market towns in Sultanpur district, both about

an hour distant by jeep or horse-drawn cart.

Baba ka Gaon is about 4 km from the tarmac road that runs to

Pratapgarh town from Ateha, the closest market to Baba ka Gaon. To

get to Baba ka Gaon from this road, one must .turn left at the large

peepul tiee j km from Ateha. The peepul tree, towering, ancient, waxy

leaves glistening in the sunlight, has a broad cement base around its

circumference on which a simple Hindu shrine with a vermilioned

statue of the goddess Kali has been built of mud. A dirt track begins

here, cratered with potholes and ditches, running past small ponds,

airy groven of mahua and mango trees, and several small hamlets.

Everywhere there are young children - their ragged clothes and thin

bodies so brown with dust that they appear to have sprung straight

from the soil - herding cattle or goats, playing and screaming amongst

the groves, collecting sticks for firewood

--J, or dribbling back in twos

and threes from school.

The track climbs imperceptibly on the way to Baba ka Gaon,

entering the village at its eastern end. Baba ka Gaon is today shaped

'

; E:».. -,

□I iI

I

kg H

i®

ji

’I

■< 9

'iW •

1 4*

L

1

■ 'll

■ I'W

11

r

j

■11

Ij?’ LI

i I

kw

r -i

I

' k' tI

rI

; 1^0

■ dk!

>y;

■

I

® h■

' I ■■

’

\

■iIt! fei

0 Fl H

/!

1

11■ f ■ K

■ ' T “if

1-J

i I

Ml I

i

■'ll Ih

'hrIh

iRia

f J I * •’

I

;•

‘

■

:

§I

ll4

HE

-'I

!

J

I'

■I

P

:i

I

' <' i EI-

«(■'

*

'' ■

oE

f

I-

E-*

r

Ba

ypjjgj

i

j

■

I

111 "'a' 'y j

I

J I

f

■

ill

’ -‘S’ »■

VaSmStA

I

-

•i

i«‘p

»{;

!

®:'fe i

J31 j

The Big Four - Ram Dass, Prayaga Devi, Shrinath, Hansraj

1/. .

. 11

rr

i

j

I

I

If:

I I

12 • Words like freedom

like a long, untidy oval. There are large trees and thickets of bamboo

everywhere. Seen from a distance, they form a copse of variegated

greens, making the village an oasis in the dusty summer months.

Outside, a patchwork of fields, broken by mud borders a foot high

and interspersed with clumps and groves of ancient trees, stretches

into the expanse of the Gangetic plain.

On entering the village, the track breaks into two, the one to the

right broad and sweeping, the other little more than a broken mud rut.

The broader track goes to the area that has always been the preserve

of the Brahmins and Thakurs, the upper castes. (The latter term is also

commonly used in UP to refer to the men of the Kshatriya caste.) The

houses on this side of the village are large — the size of colonial

bungalows - built of fired bricks, with tiled roofs. Their high walls

enclose courtyards and spacious rooms. Most have large amounts of

open space around them, where ancient trees grow. Ram Dass com

ments: The Thakurs each have half or one acre of land for their

houses. But people in my area don't even have space for a bed! The

buffaloes and bullocks tied in the courtyards are well fed. Outside a

■I

M I I

■ ill r

Jlk'

: 1 k; |

I

J '■

■ :

1

I

- I

k'

!

[ I

Ml

I®

?

in

Bl

gZifeT

asr

!

txuK

MpR'k

Baba ka Gaon

f:

■

!

18jl

i'

n!» •‘■pl

ri

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 13

particularly large home are parked a jeep and a tractor; another tractor

is in a shed near another large home.

Of the 100-odd families today in Baba ka Gaon, j:he upper castes

comprise 20 Thakurs and 3 Brahmins. All buFtwo of these families

live on this side of the village. Lower-caste people rarely venture here.

There are numerous'temples in this section of the village, most in

disrepair. Local legend maintains that there were once 52 temples in

Baba ka Gaon, all in the upper-caste area. Ofthe older temples there are

just eight left. The most important and best preserved is a simple ten- ■

feet-high structure, built of mud, open on all sides and painted white,

which sits under a magnificent peepul tree, virtually in the centre ofthe

village; this is the Baba ka Mandir, a shrine for an ascetic who made this

village his home many centuries ago.

I

Gt I

Bl

A world apart from the upper-caste area is the side of the village

reached by the rutted, narrow track. This poorer section is today

home to both the middle castes and the scheduled castes, as huts

have sprung up on the land that earlier divided the middle-caste area

from that of the former untouchables, who were forced to live at

some distance. Where the middle-castes houses are it was all jungle

till five or six years ago. Then during the land reform people began

to make houses there.

There are currently 41 families from the various middle castes.2

The scheduled castes total 35 families. This side is also home to 7

scheduled tribe families. (India’s indigenous communities are given

protective discrimination benefits similar to that accorded to the former

untouchables.) Two Thakur families moved to this area a decade ago,

as they owned large plots of land here.

The majority of homes on this side are small huts, cramped close

to each other, 50 of which would fit into the larger of the upper-caste

mansions. Generally, the homes of the middle castes are better than

those of the scheduled castes and the scheduled tribes. There are a

handful of larger houses made of brick and whitewashed. The best

homes belong to the two Thakur families; they are capacious, solid

and double-storeyed. The two Thakurs who you now see near my

house have movedfrom the upper-caste area because they owned land

r''

' r—.

Fr

.I

14 • Words like freedom

here. They moved only 12 years ago or so. They have also been

encroaching on other people's land.

The huts are poorest towards the very southern end of the village,

where untouchable families like Ram Dass s were once segregated.

Most of these huts have just one or two tiny rooms. The walls are

of brown mud and the roofs of thatch. Buffaloes and cows are tied

close to the huts or in the open courtyards of the bigger houses. Mangy

dogs and goats roam freely. But the huts and the small patches of land •

in front of them are spotlessly clean.

The men and women at this end of the village are visibly poorer,

thinner and shorter than on the upper-caste side. These are the tiny

but sinewy people who for a pittance load trucks, pull rickshaws and

work on construction sites in India’s cities and towns. In the village

they are dressed poorly in faded clothes; the older men in dhoti-kurtas

and the younger men in trousers and T-shirts, the women in sarees.

Their huts have few possessions - generally, a bicycle, a few utensils,

a charpai or two. a few religious posters and calendars, and sometimes

a radio. Their children are with few exceptions bone-thin and stunted.

I

!

■

i;?

■I

-

j

ii

;I

■

'

B .■■

■ F

i

Most are dressed in mud-covered odds and ends. Many of them are

visibly sick, with running eye infections, sores and boils. Flies settle

thickly along the eyes of the infants.

At this end of Baba ka Gaon is a large pond flanked by trees and

marshy land. The pond doubles in size during the monsoon, creating

a pretty island out of the low-lying land on one end. It brims with

a bewildering variety of water-fowl and wading birds — brown ducks,

white cattle egrets, grey herons, dabchicks, and more — who call

loudly, fly here and there, or poke diligently for food around the

marshy shore. Especially in winter, when migrating birds come from

distant northern lands, there is an air of excitement all day at the pond.

The birds are virtually unafraid of humans, as Baba ka Gaon’s vil

lagers have for several decades prohibited killing them.

Ram Dass’s family hut is amongst the last homes in this side of

the village. We built this hut in 1965. Earlier, it was a hovel. There

were two rooms. We all lived in one room. And in the other room we

used to keep the bullocks. The new hut stands on the site of the old

i

I

i

•■

•*'

■ •’'!? •• 3

>■■'■

!S: ■

1

Fw

I

I.

: I

I '-I

J.

!

I<

L

Ib

I

1

Pt!

I

I If]

■I

S'

I.

I; .

!

v

i

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 15

%

one. Built of mud and with a thatched roof of dried straw, it is

indistinguishable from the other small huts which crowd around it.

The path between the huts is narrow, just about broad enough to allow

a couple of people tolpass. At the edge of the path is a hand-pump.

A small verandah runs across the front0 of the house. Perhaps

20 feet long, the verandah is divided into two by a short wall. On

one side are housed the family’s two large, snowy-white bullocks;

on the other side is a single charpai. The eaves of the roof come

down very low, so that adults have to stoop sharply to enter the

verandah; the low caves keep out the rain and direct sun. Inside is

a small room, little more than a corridor, which leads to a tiny

courtyard, perhaps 12 feet long and 5 wide. The walls inside are

far higher than the low-slung eaves would suggest, perhaps as high

as 9 feet. There are three tiny rooms around the courtyard, each large

enough to hold only the equivalent of two charpais. One room is

a store, while the other rooms were built for Shrinath and Jhoku

when they got married. (Following village tradition, on the marriage

of their children Ram Dass and his wife began to sleep in the

verandah so that the couples would have privacy.) A kitchen, whose

entrance is raised about a foot higher than the courtyard, is where

Ram Dass’s wife sits and cooks and also serves food. Part of the

wall facing the courtyard has a brick filigree to let the smoke out;

this and the walls inside the kitchen are blackened with smoke.

As in much of rural India, there is an air of immutability about

Baba ka Gaon. Most sights seem to date back centuries. The mud huts,

rudimentary ploughs, the thick wooden wheels on the bullock carts,

barefoot old men in muddy dhotis, women with their sarees pulled

over their faces, dusty children herding goats - all these say that time has stood still, that nothing has changed.

But Baba ka Gaon has changed substantially. Ram Dass says: If

you had come 50 years ago you would have found the village very

different. The village was half the size then. There are about 100

houses now in the village. There were far fewer then, about 60. Every

family has split into several families. As the families increase the

number of houses grow.

4

o

o

16 • Words like freedom

The road to Baba ka Gaon was earl ier along the same route, but then

it was a little path as broad as two poles. The bullock carts would have

to go through thefruit tree groves. There weren ’(goodroads but at least

they could be used all the time apart from the monsoons. The Thakurs

would ride horses and their women would be carried in palanquins.

The village could not be reached during the monsoon till about

four or five years ago because the path would be washed away. There

would be waist-deep water in many parts! For weeks we couldn ’t even

get to the closest markets. Because of the new, higher road at least

the bullock carts and jeeps can always get within 3 km of the village.

There were no water taps 50 years ago, nor were there any hand

pumps. There were only three wells that we scheduled castes could

use. The upper castes each had their own wells next to their houses.

If the water in our wells finished, we could take waterfrom the wells

that were owned by some of the middle castes.

There are today many bicycles in the village, almost one in each

home. I had seen cycles as a child when going to Pratapgarh orAmethi.

I bought an old bicycle for Rs 30 when I came back from Bombay in

1962. Then in about 1975 I bought Shrinath, my eldest son, a cycle so

that he could use it to go and study. I bought that onefor Rs 105 as it was

second-hand. New ones used to cost about Rs 150 then. Now they cost

Rs 1200. The cycles used to be very strong then, like everything else.

I’ve never bought a radio. I’ve never been rich enough to buy a

radio. Shrinath has never bought one either. But now he has a small

one, which his brother Jhoku bought him from Dehra Dun. About half

the families in the village now have radios.

But I listen to Shrinath's radio or to someone else’s. I get all my

information from the radio or from talking to others! I’m an unedu

cated man.

According to official records, electricity has been supplied to

Baba ka Gaon since 1993. But the reality is that because the villagers

refused to pay the large bribe of about Rs 3,000 demanded by the

linesmen, only ten families in Baba ka Gaon have electricity connec

tions. Hence, though the village and the adjoining fields sport electric

poles and wires the village is still not electrified.

7’

j

hj,

•*

Iw

I

", 1P

t it

I fill

>t

'

•J

OR

< kH”®1

yv.

> lb ; i/ii1■

'i

n. r . -

I

I

I

I

I1

j.

I

j

i

r 3

i

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 17

11

'

t'’ 1:

r

Eight of the houses with electricity also have black-and-white

televisions. Three of the Thakurs and one Brahmin have televisions;

the rest belong to middle-caste families. The two tractors and single

jeep in the village belong to the Thakurs. So do three of the four tube

wells for irrigation; the fourth belongs to a middle-caste family.

If Baba ka Gaon has changed substantially in the past half-cen

tury, the area and towns surrounding it have been transformed. The

roads to the towns were earthen. They had holes in them, and water

would collect after even a small rainfall. If it rained hard the roads

would be unusable. There were no cars. There has been a government

bus line since the 1950s. As the road became better there were more

buses. The proper road - levelled with small stones but not tarred

- didn 't come this side of the river. So we would walk to Gushannath,

>v J ' -

cross the Sai river by boat, and then catch the bus to Pratapgarh. It

I .fa]

■

■. -i 4:

’ ■

■■

:

J-'

I 11

L;

MK

' 11

111

1 W

- li

■ -

■i'

r.

J .

J!

f

■I'i

1

it

I i.

11. ’

I

!

i

?

I

I

I,

v.

i-

■

would take over three hours, but even today it takes nearly as long

because the buses keep stoppingfor passengers! The tarmac road has

been 20 years in some places, 10 in others. Now even the villages are

being linked by road!

In the past, wealthy landlords would use horses, palanquins or

bullock-drawn carriages. The poor would walk or go bn crude bul

lock-carts. The 20-km journey to Amethi, a nearby market-town and

the seat of the landlord’s estate in which Ram Dass’s father was born,

would take over two hours on foot, slightly more by bullock-cart. The

pony-carts of today didn’t ply then because the rutted dirt road could

only be managed by bullocks.

Today, the bicycles and bullock- and pony-carts mingle with the

rare government and private bus, the occasional jeep-taxi, and some

times with tractor-drawn buggies. Most of the roads are cratered with

deep potholes.

Pratapgarh used to look like what Gauriganj is today. In Ateha,

there was only one brick house — that of Noor Khan — the one on the

corner, which now has the post office. The rest of the houses were

mud and thatch hovels, like those of us poor people.

Because there were so few people, the bazaars were also little.

There were just a few mud huts and a small weekly bazaar. They just

o

o

• i:-T; IP

•i .f

I I

18 • Words like freedom

used to sell local produce, clothes, and utensils. What else was needed?

At that time no one had money to buy cement or bricks to make houses;

it’s not like today where everything is available.

Pratapgarh, the district capital and formerly the seat of a large

zamindari estate, some 50 km away, is now a typical north Indian

town: dirty, congested with all manner of traffic, lacking the most

basic municipal services. Any charm that it might once have pos

sessed is now obliterated. There are innumerable shops, catering to

almost any modern demand, be it photocopies, car repairs or video

movies. Outside the town is the grand mansion of the Pratapgarh

rajas, surrounded by mango orchards. Pratapgarh’s population today

is about 30,000.

Gauriganj, the jumped-up village that Ram Dass compares to

Pratapgarh of half a century ago, is in neighbouring Sultanpur district,

but only 20 km<away from Baba ka Gaon, making it the closest large

market. Gauriganj is still little more than a village today, boasting

just one long road of shops and another shorter one with a hawker’s

market. There is a tiny railway station. The open sewers are choked

with excreta and plastic bags. People defecate and urinate wherever

privacy permits, the men most often along any convenient wall. A

single fall of rain turns the roadsides and open markets into a

quagmire of filth.

Ateha is the closest large village to Baba ka Gaon, about 5 km

away. It is built at the junction of several roads. Centuries ago, Ateha

was reputed to have been a fortified town, but there is nothing to show

this today. There are some fine large houses, and an attractive mosque

as well because of the large number of Muslims living here. The roads

are potholed and cut by streams of blue-green sewage.

Amethi was better than Gauriganj. People there looked richer.

The traders were more reputed for their wealth. But even so, there

was nothing in Amethi then; now it is a big town. It was totally barren

and now look at all the shops. Amethi, some 20 km from Baba ka

Gaon, became a household name across India when it became the

pocket borough of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. The town

itself is no different to Pratapgarh — just smaller and, if possible, even

J :

I

iI

j

A

j

ji

kJ | ■

I

•

I

: v

■'Ji

f jIi ’ J

•

■

-A.

I

I

T

■ii:

T [

J

.■ I|

i

I .

r

: !•

'

I ■ :I;

I

:1

1I

f

.

.k. j.

' ' •

i

'i r ;i

*i ii«

-v-jt

■ * i*

•l

■

1

"!-

h: diI ",

' ■! !W

: ||| i jtt

J A; IS *' is -i:

'kJ

1 LJJJ >'

•

Ilk"

■' .1

■•

J '

k'

aI "

11 ■1 P'

■

f

)t Bi

I'

4'. .

1i1

messier and more choked with bullock-carts, tractors, jeeps and

innumerable people. Its growth has been rapid because of the influx

of government funds for the district. The handful of older buildings

- including a mosque, a college and a few large homes belonging

to traders - have been far outstripped by scores of new brick

buildings, weakly built but two storeys high, that have gone up in

every direction, seemingly without licence or planning. One positive

legacy of its years as the constituency of a prime minister is the grand

railway station.

’

j

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 19

r h'

■

j :|

I ? • IT' -

;I •

I

4 n

If

' '

f

■:

■

|

IB i

■1

J

ii

f

I- ■ V

■f''

!

•. >;

I

r

■

■

TfJ;.-

p■

J

St ■■

>J

I ■

I

pl

ill

Rh I

It

1

sBiFl If

■

MH h'K*'

' II 1

I :f

■

| Wt

''j'- ■'.'Jj

f"

I :■ ■

■t

■'

Why did I choose Ram Dass and his family out of the many million

impoverished families in India? And why Baba ka Gaon, Pratapgarh

district or UP province?

India’s size and social diversity mean that no one region, province

or district can be typical. As I was picking just one area, I took pains

to ensure that this area would not be unusually rich or poor, but would

approximate the average. An obvious candidate was UP. With its

current population of roughly 150 million, the province is home to

about one-sixth of India’s people. The northern, Hindi-speaking belt

of which UP is the major constituent also contains the largest aggre

gation of the poor within India. In addition, for several decades the

proportion of the absolutely poor in UP has been close to the national

average. Within UP, I chose Pratapgarh because it is a fairly average

district, neither unusually prosperous like the province’s western

districts nor as poor as the southernmost districts that border Bihar.

Apart from being quite representative of India’s development

experience, both UP and the area around Baba ka Gaon have been

at the epicentre of modern India’s emergence. From the early years

of this century, the Indian National Congress flourished in the United

Provinces of Agra and Awadh, as UP was then known, and the

province became the core of the nationalist struggle. Mahatma

Gandhi first enunciated his programme of non-violent aggression to

achieve independence in Allahabad in 1920, 75 km from Baba ka

Gaon. Allahabad was the birthplace of Jawaharlal Nehru. The demand for a separate homeland for Muslims, culminating in the

20 • Words like freedom

creation of Pakistan, was led by UP’s Muslims. The province became

even more crucial to national politics after Independence in 1947,

as the introduction of universal suffrage gave populous UP one-sixth

of the seats in Parliament. Seven of India’s 12 prime ministers have

come from UP, five of them - Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira

Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and Vishwanath Pratap Singh - elected from

constituencies within about 100 km of Baba ka Gaon. Rae Bareli

and Amethi, the pocket boroughs of Indira, Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi,

border Baba ka Gaon. What better site than UP and Baba ka Gaon

to come to grips with understanding why the Congress, Nehru and

his political dynasty, and independent India’s politics, have failed

to emancipate India’s poor?

Why choose Ram Dass and his family out of the half-billion or

more impoverished Fndians? Much as in my choice of province and

district, I made every effort to ensure that the family I chose would

be fairly representative of the Indian poor.

The vast majority of impoverished Indians are of low or lowermiddle castes, along with indigenous tribes ’and Muslims of low

status. Three-quarters of the Indian poor live in rural areas.3 Most are

artisans, landless agricultural labourers or farmers with plots too small

or infertile to meet their families’ subsistence needs. Generally, the

less land they own the more vulnerable they arel to labouring for others

at exploitative wages or renting land on adverse terms. In urban areas,

a large proportion of the. poor are recent migrants from their villages,

seeking relief from their poverty. On arriving they compete against

each other and the growing number of resident poor for any kind of

job: begging, pulling rickshaws and carts, working as porters, labour

ing at construction sites, quarries or road construction, cleaning toilets

and sewers, or working as menial help at roadside eating places.

Generally illiterate and without appropriate skills, their employment

prospects are so bleak that the luckiest are those who end up as

domestic servants or as manual workers in factories. The migrants are

generally men, who leave behind their families in the village. Only

the most desperate of families move entirely to urban areas, with

every able adult and child taking up whatever work they can find. But

is

Iw

If

Ir"'

!

I

I

■

■ J

• ■ j

•

I

r ’

ill

yd | -

. fMb:-j

Uli r ;

I: ?4' |||

• • v|

1 ■J

li!

■ II

‘.'■i

■

.'.'j

.■•yy

■

-0

ii

IU.I

u

i •

1 V.1

u-t

•J'

■ i;. ? ‘

■

I

■'

■

y .

,

.

A-' ;

■3

• I

.!

■ ■

=

I :' i

' fW;

Introduction: This naked, hungry mass • 21

Iiwi®1"

i f■

ill

■ 1.1 If ■

■ fei-i

-

■ tit'' ■

I ■

p.T;

■

.

■'

f

J- ■

1

1

;i I ■'

cI

■

f

I

.

A •

T’’

I'--

t

T'4

-

is ■ Str

J.:

.'

>■

r

■

.

■

>:

im

1 ■

11 . i

•J' '

J

i:

■

■

..

L I

L

I

■

v;

&

r

i;i

r

■-.1

•k

• I

■ ®!'

11

V... i < it

"

Tii’ i! '■

■

.

whether single or in families, the migrants often find that because of

high unemployment rates and low wages there is no relief from their

poverty. Crowded into the hutments and slums that now dot every

Indian town and city, or surviving on the pavements, they discover

that living conditions in the urban areas are often as harsh as the

deprivations of the villages they fled.

Ram Dass’s family is in many ways ‘typical’ of this vast

multitude. They live in a rural area. Like large numbers of the rural

poor, his family until recently owned no land at all and survived

primarily by working for wages as agricultural labourers. They are

of an ‘untouchable’ caste, who have always comprised a large and

disproportionate share of the Indian poor. For aeons there was not

one literate person in Ram Dass’s family. Members of his family

have generation after generation fled to urban areas to seek work.

Some now live there permanently.

Ram Dass’s family is also representative of that small percentage

of the poor who progressed in this half-century from intense depri

vation to being above the threshold of absolute poverty. I focused on

a relatively mobile family for two reasons. The less weighty reason

was to avoid the accusations that would have followed — to the effect

that I was exaggerating India’s failures - had 1 chosen a family that

was still direly impoverished. (Of course, such charges are entirely

misplaced because extreme deprivation is the common fate of at least

40 per cent of India’s population.) The more important reason was

because the experience of Ram Dass’s family testifies that even

families that rise above the threshold of absolute poverty still remain

trapped in want and oppression.

There were other compelling (and beguiling) reasons to choose

Ram Dass’s family. Ram Dass and Prayaga Devi, his wife, are amongst

the few surviving poor people of their age in Baba ka Gaon or in the

other villages I visited in the area. They are both still fit with their

memory and senses undiminished. Both lived through the last two

decades of British colonial rule, witnessed Independence and a full

half-century of India’s sovereignty. They are amongst the few remain

ing witnesses of the history of the Indian poor in the past half-century.

’ I

.1

22 • Words like freedom

Moreover, Ram Dass was one of the few poor people in the area

who knew of the 1919 Awadh revolt and, even more important, that

his family had participated in the revolt. (He was born half a decade

after it.) Another unexpected bonus was that a branch of Ram Dass’

family lives in Amethi, the pocket borough of former prime minister

Rajiv Gandhi, presenting an opportunity to compare whether the

decades of being a ‘VIP’ constituency had benefited the poor there

in comparison to those in Pratapgarh.

Ram Dass, Prayaga Devi, their two sons, their eldest grandchild

and Ram Dass’s sister are the core of this memoir. Their vision of

life, their view of independent India, and their life stories are por

trayed here. Like the millions of other impoverished Indian families,

they suffer hunger, disease, the death of young children, illiteracy and

every other conceivable deprivation. As untouchables, they dispropor

tionately experience the cruelty sanctioned by the Hindu caste system

against low castes. Landless, they are exploited and abused by the

landlords they are bonded to. The members of this family speak of

these things, they convey what it means to be poor.

They also talk of their unremitting struggle for survival and for

social and political emancipation: their efforts to save their children (

and to educate them, the fight to acquire some land, their inspiration

by radical leaders of the untouchables. They'speak of their achieve

ments, of the gradual changes in Baba ka Gaon, and of why the vast

majority of the village's people are still impoverished and oppressed.

They assess the politics and policies of independent India: the Congress

party, universal suffrage, land reform, local self-government and

progress on alleviating poverty. They enunciate their criticisms of such

national icons as Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and leaders

like Indira Gandhi. They speak of their betrayed dream that India’s

independency wpufd liberate them from poverty and subjugation.

This memoir is a record of their experience and understanding of

these developments. It is also an insight into why, despite their own

efforts and the coming of Independence and democracy, Ram Dass’s

and many millions of other Indian families are still impoverished and

possess only a grudging measure of social and political freedom.

R !■; j

- u

,

1

i is

| r

Jt

■

j 'T1 8 r«!:

; f IL Lf4

•I'; i Ji

'

J '• fij

.

O ’sL

' I: if f

■.••I

Ha

I

L Vi v r-

' I’1

i

r ■

■

I

.■ ji

4

II

r ■

■■

;'

I

h

p

i

■■■J

2

The Slaves of Slaves

f

i

i

I.

■

- L 1

J:

&

W• ' i

i ■

Oil

'7

■If

K

ft

'bjBfiii

«i i

'"■I'-"

r 1

JI

J

! •

•■J fed

it

'. 11

I ;■ |

Jr ' L Ji1 '

I 4

I' ' ;\ II 11

i

it

I-®

I

■h

i i

i

■

•

I

;

■J. '

RAM Dass was born in the Pratapgarh village of Baba ka Gaon six

or seven years after Nehru’s visits to the district - in 1927 or so. He

has only a hazy memory of his parents telling him about the revolt

against the exploitative rule of the taluqadars and zamindars, the

mighty landlords of the region. He knows that his parents and several

other relatives participated in the two-year-long struggle but remem

bers little about their involvement. He does not know about Nehru’s

visits to Pratapgarh nor of how the landless and the poorer peasants

were eventually betrayed by Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and other lead

ers of the Indian National Congress. But Ram Dass’s recollections of

his childhood and youth testify to the oppression and misery that

Nehru glimpsed in his brief weeks in Pratapgarh.

The zamindars were the slaves of the British but we were the slaves of

slaves. Because of this we were so poor. We had only our miserable

earnings from our labour for the zam indars. We would slave all day

long for them and then get to eat a handful of grain at night. Our

zamindars were Thakurs. There were three Thakurfamilies who con

trolled this village. They shared ownership of the entire village audits

J..

• •

o

o

o

o

!®'.- ' ■

<<'1

24 • Words like freedom

lands. They were rich and powerful people. They had about 800 acres ■

of land between them.

Because of the zamindari system, we had no land at that time.

Everything was in the control of the zamindars. Everyone used to work

for them. Even the land on which we built our houses was theirs. The

administration was theirs, the land was theirs, everything was theirs.

The zamindars would never work. They had to do nothing at all. They

would just sit and eat!

Each of the zamindars had groups ofpeople dependent on them,

and they would either give us land to plough as sharecroppers or

give us work as field labourers. We were bonded by tradition. We

were like slaves, we would only work for one family. They gave us

loans and then made sure that we were never free of the debt. At that

time we were giving the zamindars Rs 10 for renting a half-acre field

for the year. My family could sometimes afford to rent an acre or

so. What would we earn? Nothing! There was no irrigation and

productivity was low. But the zamindars would pay just quarter of

a rupee in rent to their overlords — the zamindars of Rajapur and

Rampur - on a half-acre, even though we paid Rs 10 to them. They

would give us land on either a rent or a sharecropping basis. The

terms were up to their whims. They would give it to you for a year

or two and then they would take it back, saying that they wanted to

cultivate it themselves. Sharecropping was half of the threshed grain

- you didn ’t share the husks. But then the zamindars started

demanding half the husks too. They could demand anything they

wanted because they owned all the land. Today a fraction of what

you produce is enough to pay the rent. Then more than half of what

you cultivated was not enough.

It was only sometimes that my family could afford to rent land

from the zamindars. But even then we would need to work as labourers

for them as we were so poor and the rent so high. The rest of the time

we would do their field labour and be paid for the days they gave

us work. For a day of hard labour they would give us one or oneand-a-half kilograms of grain. You took that back to eat with your

family. And that wasjust one-and-a-half kilos - which an adult man

•1- ■ I

b I

f ij

I

i ■ * ■

fc i

.1

’I

if

I f ■ ■’

Ii- ■

.

r.

? - ■

f• I

11 Li

■ fl

■

■)

4 r

I

O'. ■,

■J -

J-1.1'"'

fi

■

.1I sI

■ ®

if

Hit =

Hif1

■ 'fc

S' .■

■

•

■

FT'

'fr

ii

f.- " ' ’ ':' ’ '

K:V .... . I .■; _

The slaves of slaves • 25

I 'W-

III"

I j;?

Ii

fS

f: i ; ■

■ >■■

I

II

1!

I

t

, I I'

L

'■

'

'''

'

I"

.

!

.

.

1 I

i'

t *

It f

■'f!

t

d'-: |

'

I

■■! f y

:

' :

Lfew

- ■ H ■

•'i

-

</ i

. ' -i

i: i

■ •

:

:l

•

■

■

|' ' h' '

cl If.'

.!• ■ji"

i ih

if 'S »■ £•

r I .;i; :-j

?

'i' i Ip:

:>J iff- :

ii ai'ift

PF

ill. a feW; 's. '

V^

IfeVi

t

IbH " '

if

■ ‘B

: i;.'

hi ri;:

I b

■■■

k

wfc -

'■ li •

f l -S ■'.1

it'!

■■'

could eat by himself! We would have to think what to do with this

little bit offood: should we feed ourselves or our families or pay our

debts? So how much could a person save, what portion of this food

could they forgo eating so that they could buy clothes?

The zamindars could do anything. They could beat us, thrash us,

torture us! How could we have gone to the police? None of us poor

people ever went to the police. Ifwe had, the Thakurs would have told

us to get out of the village and they would have just kept all our

possessions. Anyway, the police also belonged to the zamindars! The

zamindars ’ attitude was: 'Obey my orders or leave my village. ’ You

had to do what they wantedyou to do, and ifyou didn ’t, you had to run

away. If we uttered a word, they would take off their shoes and beat

us. If we didn’t understand their orders properly, they would beat us.

And that’s how time passed, my ancestors ’, my parents ’, and mine. We

had tofinish workingfor them and only then could we do our own work.

We had to finish theirfields before we could work on the land we had

rented from them. Sometimes when we rented land, we would have

planted the crops, tended and harvested them, and then the zamindars

would come and take away the harvest! Or they wouldput their horses

and bullocks in our field to graze. They would harass us in every

possible way. And we couldn ’tfind refuge because they even owned the

houses we lived in. Ifyou can’tfindprotection in your own home, then

where can you go? And ifthey were passing byfrom a distance and you

didn’t get up from where you were squatting, they would shout to you

to come to where they were and then they would thrash you.

There were some zamindars who were kind. Not everyone was

bad. The kindness was only in the way they treated you, not in how

much they paid you. If some zamindar oppressed you too much, the

kind ones would try to stop that harassment. And the kinder ones

would not exploit you as much with the begar and hari [forced, unpaid

labour and ploughing, respectively]. Others would make you labour

the whole day and not even give you food after that! Not just the

zamindars but all the members of their family would harass us. Ifyou

spoke to one of the upper-caste children not only would the child hit

you but one of his elders would come and hit you. ‘Hai! Give the

V

| i

Fl ■.fin

I

o

o

• £

!H

kk

If

j

If

26 • Words like freedom

damned creature a few blows!' Some villagers who were harassed a

lot would just run away al night to their relatives or to a city. They

would leave stealthily, because the zamindars wanted us to labour for

f5

them and wouldn 7 let us go.

Whoever is powerful, it is normal to be afraid of them, especially

those who have you at their mercy. We were scared that they would

beat us up or hit us because we were poor and depended on them.

How could the poor fight the zamindars? How could people who have

11 •

1

■

I

., .• I.

1

'-■1

T - .I I

I

J

‘ i-

' IM

■

k

*

.... * | S

• -j

■• ■ : - ■

••■N

-rfj

? !;

'rf

: • ■ '■

. •

...

■ H

11

pf

:

The Persian terms zamindar and taluqadar originally referred to

a large range of intermediaries between the ruler and the cultivator

who played a role in revenue collection. Under the British, however,

they became synonymous with landlord. The terms were essentially

interchangeable across India, though in Awadh taluqadar referred

to the grander zamindars', zamindar is used here to cover both senses.

Awadh’s agrarian system had by the 1900s reached an intensity of

exploitation of the peasantry in great part because of comparatively

recent developments, dating back to the late 1850s. The British East

■

kk'l

nothing to eat fight?

Ram Dass’s family had been subjected to this poverty and oppres

sion for as long as he and his parents could repall. Aeons ago the

untouchables were thought to have been the original and privileged

inhabitants of fche Gangetic. plain. But that past was legend. The real

past, the one his family recalled, was of their being condemned to the

base of an exploitative social order.

Describing Awadh of the 1920s, Nehru wrote:

It was, and is, the land of the taluqadars - the ‘Barons of Oudh ’ they

call themselves - and the zamindari system at its worst flourished

there ... In the greater part of these zamindari areas [Bengal, Bihar

and the United Provinces of Agra and Awadh] there were many

kinds of tenancies - occupancy tenants, non-occupancy tenants,

sub-tenancies, etc. ... in Awadh, however, there were no occu

pancy tenants or even life tenants in 1920. There were only short

term tenants who were continually being ejected in favour of

someone who was willing to pay a higher premium.

b

■-K f

.. . ■

i-; ■

’■ I

. ki

p |

>1 U

"ilk

: L'sl

1In

,'i Ju

If .

■ I bl

■

l|ira

■Jal i

. M:

U

i: 1

■

j aw

i PrTr'

The slaves of slaves • 27

■wT r'' ’

■

"R T.

I1:

India Company annexed the kingdom of Awadh - the largest of the

Mughal successor states, in area and population substantially greater

than most European nations - in 1856. Shortly after deposing the

kingdom’s Nawab rulers, the British Crown (which in the meantime

had claimed the Company’s Indian possessions) settled absolute pro

prietary rights in land on the larger of the zcunindars, who combined

the role of local chief and hereditary revenue-collecting intermediary.

This strategy of coopting dominant local chiefs as junior partners and

collaborators in their rule had already served the British well in

establishing a Pax Britannica in the areas that they had annexed over

the preceding century. But, as in those areas, the vesting of land

proprietary rights with the chiefs fissured Awadh’s rural society.1

•

■

' 'i

LT.;'.

''

■

i

Til

■ . .

i

’ t'

■

i ■■

T--

s'I j

■

■; $

;• •'? i

J

■ ijr

pp'

•

’■!!'

;

j

r

J

■ . I K

■I

- h* I

•$.,

r-?

••

■'

•

.

i

f-'’ HI"

: ;||h-vIW ■■ ■

'■

.

■

V

■

-

'■

•p

f-pl

T ,,L

: If "

'' ' ; :

,.,

? ,;' A

*

' 'l; lbitr-

ffl

'1

. j'M 'f-i1 ■ •

11,li'j

J!

F1j;. ,gi,l

A ■ ■

illI i ■ 1

■

"‘if’'

■

"I an

pb'b

. i-

The disruption occurred because though the larger zemindars had

during the waning years of the Nawabi often raised themselves to the

position of de facto rulers of petty principalities, they were not landlords in the European sense of owning extensive landed estates.

Under the Mughals and in the successor kingdoms, there was little

notion of private ‘ownership’ of land. In practice rights to land were

shared between peasants, who enjoyed hereditary occupancy rights

that often approached de facto ownership, and village zamindars, who

typically raised revenue from the peasants in their village and had a

limited power to alienate land. Land was seldom sold or purchased

as a commodity, and so long as the peasant paid the taxes and dues

levied on him, he could not be evicted by anyone and typically could

even repossess land on paying arrears. It was only on a small pro

portion of the cultivated area - the ‘home farms’ - that the village

zamindars had an untrammelled right of ownership. The larger, elite

zamindars rarely owned home farms, deriving their wealth from a.

share of the land revenue.

But to the British, logic and custom demanded that there be a clear

owner of land, that this owner pay the land revenue, and that the

owner’s rights on the land be extensive and permanent so that he could

work the land profitably. Rural Awadh, like most other parts of village

India, was remade in the image of the contemporary English coun

tryside. The zamindars’ right to collect revenue from a given area was

L

i

ih"

bte

•. I

■J

I<

■

Lt

28 • Words like freedom

elevated into the absolute proprietary right of landlord. Not only did

ownership of the vast bulk of cultivated land shift to the zamindars,

but their power and wealth multiplied as the British soon made them

the owners of inhabited sites, fallow and barren land, groves and

orchards, water sources, river crossings, markets and roads. These

landlords became the linchpin of the colonial order in Awadh, pros

perous and loyal allies of the British.

Awadh was soon a paradise for landlords, a trend common to

most of India during the century-and-a-half of British Company and

Crown rule. In Awadh, some 200 large estates emerged. These land

barons, like the Rajas of Amethi, Kalakankar and Pratapgarh, whose

estates lay close to Baba ka Gaon, controlled scores of villages and,

in some cases, thousands of acres of cultivable land. Next in the

size of their estates were several thousand middling landlords. These

included the wealthy landlords of Rajapur and Rampur, kinsmen who

shared ownership of Baba ka Gaon as well as independently owning

several other villages.

Below the large estates were thousands of village landlords. Some,

such as the Thakurs of Baba ka Gaon, were ‘under-proprietors’ of the

larger landlords, who left it to the village worthies to extract labour

and exorbitant rents from the peasantry. But even the latter group were

in effect powerful landlords, as they generally had absolute control

over the land they rented from the larger landlords, which they did,

most often at a low rate fixed in perpetuity. Thus, the Thakurs of Baba

ka Gaon were in essence owners of about 850.acres of land which

they leased from the Rajapur and Rampur landlords and then rented

at vastly higher rates to tenants.

In this agrarian order, the landlords, great or small, elite or village,

did not play a produbtive role in either cultivation or exchange. They

took no part in agriculture beyond renting out their land or having

it worked by labourers. But even if the landlords did not add a paisa

to the agrarian economy, the British were unflinchingly committed

to them: the landlords had become their trusted intermediaries in

revenue collection, policing and administration. The British faith was

stated eloquently by a senior British administrator - soon to become

s ’I

1

;

I ■

I

■ '« k ,

.■ ■, I

LI j

M I

!

■ V;

mi > ji’,/

■I

.• ; ;

■ ■ Hl

•• J I tjV

■

I

: i Jw

V

’, >■.:'Mi

f

- r •T

Lt-;

■'.

'

■

■

•f. 3 '. :

■ N

i J ' . ;-1J f ■

i'l/M

' Iv

'/.Mb.--' m

:

... I'

MV

I !aa

' 'pl ■Ml

I Si?

^'1 :■■

' IW

I.’

I

I

' fe iff

’‘ISw

I-inf

fl

I .

«iiW

• •ES

I

i

’'IM

■S1

‘V> ■

'■'1

< i1

J’’*

..

Im

■ f

:T :

I'U .

!

! 11 f

J, >

■ q t

I ■ <

' 1 £ • r!

I

J |.1

I

' I'

' I ; -g

£1 J) IB ■

*■ ■■■Bi '

«

-1I

W

R<l

■ ■ t

-I

i

j

' <1.

ft ' VW

1

T

I

i'l

I i:Ji

|

1

N

Iw

w

. ? fl : r ...

•'t <■■■ .

; I ; ■

u

i

'1

I

t

■ ,f

The slaves of slaves • 29

the Governor-General of the province - Harcourt Butler, who as

serted, ‘For political purposes the Taluqadars are Awadh. In times of

peace, and still more in times of civil disorder, their voice will be the

voice of Awadh,’3

In turn, Awadh’s landlords, like chiefs and princes across India,

did not fail the trust put in them. They curried favour with the British.