URBAN SLUMS

Item

- Title

- URBAN SLUMS

- extracted text

-

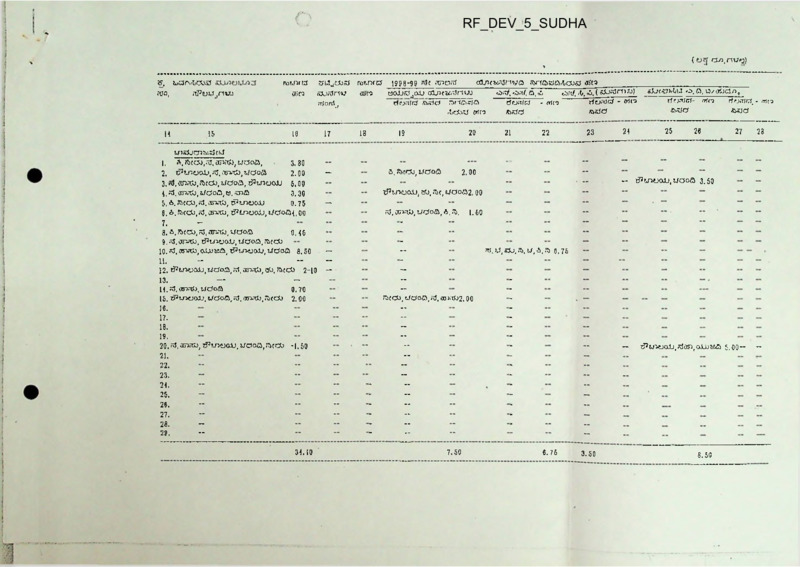

RF_DEV_5_SUDHA

(H-d.HUtj)

s, ijHrvt.c'un

alo,

aPeji.) ,hvj

H

1,

2.

15

w>«3Jo>ais;<tJ

a, RicOJ.a, an.Ui, unoa,

D3tnoodj,a,an.H),UBoa

rut-nra

xn

sUj&>a

auanu

nlontj

18

17

3.30

2.00

—

3,nJ.®sni,atcu,VQoa,rPusoou 5,00

l.H.on.Hi.Ucioa.B. asa

3,30

5, a.sicOJ,a.an.Hi, tJ’ineioAi

0.75

6. a.accb.H,chiH), tJ’tneolj,tJHoai,00

7.

S.a.atdi.a, ot-hj, uooa

0,<G

9. H. <mH>, tJiinooJj, uooa, atcb

10. H, anaU, olx-wa, tPrineoJj.Udoa 8.50

11.

_

12. iJ5vnt>alj,Mcfoa,M, an.tJ, S.i, >5(CO 2-10

13.

—

H.H. an.tfj, UcJoa

0.70

15. zT’t^xjodj, Mdoa.a. .m.H>, acd> 2.00

rowrtd 1398-99 ■">< anon

olntwdHva .t>nasa.Ga^a xn____________________________________

a>ra

BoJjayxij <xu> wdnw

os/, suf, a, <s

u>a/, .0, <6, (suaniw)

sixain u>, a, uzalicm,

tfrji’Tld siHcd aHCiaa

tfrjald - alto

rfcja/H - tries

rfcj.Tlcl- cries

rfrj.Tfcf. - .rits

.!)rt>a tries

atid

ssaci

aatd

Wd

18

20

19

21

22

23

25

27

23

zJ’u'XJoU.Han.aljjtiia 5.00—

-

26

2.00

i.S'dj.ncoa

—

tJ’tjstjai), UDoa 3.5Q

iJ’ineoJj, Hi, R>f, UOoa2.00

—

a, anH>, urdoa.a.ft.

1.50

•h. >j, au.r>. u, a..a 0.75

—

—

acct), ddofl, rd, et!:;tfj2.00

16.

17.

18.

19.

2O.H.mH>, tftnoaU.Ucioa.accO -1.50

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

24

—

-

34.10

7.50

6.76

3.50

8.50

asanfuss auonu - gjauy sSckarw

SKTiruS

5,^0.

atfau aSWcfc

I

vlorltJJXM

2

tf-nvif gdcBcS Mara

_

sae^rneAnoJsnco oao

SJX5tJ3j

3

£k^(COF

O-rt)

4

5 ’

RjQxe>/anKjrs

sjaaJrs

2-28

2-02

0-28

0-30

0-05

2-20

<x<r3

(Sod

roaRlejj

^ohS4

"diru AjOrd

6

7

150

50

218

134

35

1080

14

333

490

888

62

HOGlrCb

cuorlFcO S3,

8

9

10

750

250

1090

670

250

5400

70

1865

2450

4330

310

1010

450

120

590

320

130

2800

36

900

1200

2100

160

500

117

290

303

125

255

192

178

141

171

571

37

38

166

250

550

1496

585

1495

1515

625

1275

960

880

705

355

2585

185

190

830

1250

230

690

300

750

750

325

600

450

440

350

430

1300

95

100

410

750

6875

34225

17376

oS, ojO, •XJ3C3

11

12

13

300

130

500

350

120

2600

34

765

1250

2230

150

510

3oa

75700

300

160

2000

200

100

190

150

75

250

250

75

200

220

25

3150

20

1400

850

2260

160

400

20

60

150

750

60

20

30

215

1450

1330

110

550

200

806

285

745

766

300

875

510

440

355

425

1285

90

300

1000

20

250

1126

500

440

300

—

100

100

250

-

90

420

500

390

220

60

395

555

995

389

125

815

540

400

705

855

2585

185

190

830

640

16849

128811

3295

18049

tnSJcnaStiJ

I, <La3jOfcJ coL/^

2. sjjCr^o^F iTxinc^

3. njXTiodjraFo *< e\j mcarnj

4, <3, FlljQC'csJ FPC3fnJ

5. cjoeJ -ScFcJaj^ rrxafnj

6, ancjO £}<bcs; mdfHJ

7. aortSj maras

8. cnsjjrs. rnaraj

.9. SjoCuos^jra roa^eju

10. tsrSocjjXJo

H.CTiSUS, rrxarFS

12. zJoiA)3nv4

13.

fdgjfhJ

ll.Hr-ncnwsfj rr.cJERi

15.5ja4oJJ5zJJ rrxd

16. sdcj53Ju mcJfFu

17,33X30

maro 2

^°3

18. SFv-rtcu mOrO 2

c?5o3

19. wsDjWSjj ftx3ffJ

20. cnsxjrt-ncsne) ftjOfhJ 1 f3< mo3

21.rt3O2ju rvxnro

22.

eseJteojM/

23, cn-OHjrXjOaOcnWjj

2 4. ^o&iou «n^O

25. t>F^nctJF3HO

26, ojowx3r3joa

27, 53JJK)Hjajo3J3ja mclEr\f

28, M-ruecf nrx3c/ mc3F?tf

29.<OJ^^f o3jO eooux3

OJOC3U

lOrlxb

lOrLrt)

•

■

•

•

0-28

3-03

3-10

2-05

1-05

1-04

0-35

1-05

1-29

0-09

1-04

0-20

9-10

0-17

0-28

3-00

1-10

0-07

0-01

1-10

—

-0-30

29-01

*

3<

•

3 <5

3 mo

3

»o

17 mo,

3 mo

3 MO

•

•

11«°.

3 MO.

•

202

al. i7X)3C)rbs3

110

299

17«o.

3<i

•

•

3<^»

HMO

■ 17«o

HJ

.

3

MO

20

120

480

—

Zj.GJctfrlt/

2S(^«3X3-<3Q'35J9Cb

S&fcf

2j-P ( Z<C5

______ _________________

•=

roaajei)

rtoelai)

aSorlnl) ;S,

Zj, ZjO.

9?30

d,«o.

w^odj c^HjCO

rf-oy't? scSctjgJ ao?6dJ

sJ^od’zid

succor

6

7

8

9

10

13

3

5

12

2

4

11

1

1-25

1-15

2-10

1-30

10-30

3-20

2-10

3»o.

3<^

160

150

146

1000

900

700

600

300

400

300

200

300

200

300

200

•

1200

700

500

400

400

4000

2000

500

500

300

300

3200

•

228

700

3200

440

200

200

100

100

2000

500

200

440

•

101

272

420

65

200

195

230

18

410

610

1632

2463

386

1150

1000

1300

80

400

950

1463

186

650

600

800

40

210

682

1000

200

500

400

500

40

100

302

463

2439

1188

1251

200

500

1000

60

650

200

300

30

376

902

1026

113

8435

. 3122

466

436

829

1-00

0-25

1-10

5-25

226

205

32

1205

446

527

61

4010

1504

499

52

4425

1618

44-23

6018

36198

19546

3 MO

3 MO

125

240

3»o

•

80

410

30

100

100

180

96

1183

93

300

650

14 40

400

2300

300

900

450

960

476

6980

600

1500

162

1300

273

350

800

200

1200

175

550

250

500

275

3447

380

900

92

900

141

iJc-HyjXJjl

01X3^03'

1. «0«f. -i. ZPjG'jC), <T«3O JjOHjOU}

9 d tl melo(S)

3 jtfsJf kJo 3i -a, rf. n->cl/><S>

4.«o.a.

5 ooexOa^HO

6 ffinPOUo LPfiCHf

PtJd^re)

■

•

■

•

Y.'OCTin

8 tjxio'

»or5V

*

o.rffwC

cgcsWaSUg

io i_n<e> d^j

11 16 I 2

tTXllOfK), 2x5XJOj«s

]? Ll)53?v(15^&FjncJ

J3 tSSJCCS LT.otTrf

u tiocft • cnelnrS) dnci0tin^JLHJo{^

ajffnra

*

•

opaJr\

HJmrO

spztfrs

15,2j&ccj3 zJjxeS^p

16 SsJJ gtzxUsjj

ly.sij.'aaUsJj in«.)

is »JX> 'J5~. CJ CiPCLJ

io eior.cn’cialrC^

tb & w20. OorScnbis&J ■=> & wcf

iJoniz-ocD:

no

5-25

3-00

1-00

0-30

0-33

2-00

0-25

1-00

rO

2-10

tsa tb

7200

1140

310

200

300

500

-

830

1000

328

300

500

500

50

46

2017

606

63

2500

1000

57

218

16

2500

1000

202

34

3435

1122

16663

11814

8602

15882

300

640

200

1100

125

350

200

450

200

3533

220

600

70

400

132

225

300

125

300

300

840

210

650

110

350

125

500

200

5667

520

1310

17

500

100

100

425

105

225

125

250

200

261

60

80

19

500

100

90

1225

85

325

200

200

75

1052

20

16

* ■cdo.usiJajeJ

1.3 sit

riortcSiSUj

9 IJWj Xj ■ vfcf

3, SProlJ

Z.Kjouf njOi 95 o, ?S. 2J3^C3CJco^5(j

5, RSjOdJC^ Etticf rncJfKJ

6 <£. eZ>O. Uftfu

7. o. -A -Sri.

8.

o tari-no’ uiacrtf

10. uwlttnck ^#,86

U.nJjCwC^ (TX1OC&, bDjRju) CfXj

12. rnogj n^j.iXoccf lp^oo' cJaJ

13. ^ep^rDQW

14 tSnccf LP^otf.&tnrf-SS

15,«tf-P(O LPiertf «£Cl)Cb

•

• ,

•_

■

•

■

i5fLtT>

■

*

•

■

•

2-10

1-30

2-10

2-38

0-08

0-20

0-03

-

I1OO

•

3

rO

0-24

8-35

1-20

1-20

2-00

2-10

1-20

24

’ 256

135

_________

26-13

no

126

300

73

e o p n 'f ip ’ zi

G oon

o o p n '5 --o -H

e o fin 'J jp -c i

(ejef dn.rttfq)

alxrxDtlnz?

d.

stj^Fw

dbJud>a3

rjejxcJ

aSra

aiCQ

R5o,

ajonS

1998-99

al-nfWdrWQ R^s^sj<aA>c5o53 sn

RnoRJ

cjoUal^oU oUacddRin^j

tfORSd £>a3c5

sin

u

15

16

2.20

1. So. fttOJ, u, &<S, csrj

1.65

2. Si, nJCCl), OR}, ?JOoa

2.10

3, io. &csJt d^tnooU, Oag, UOoa

4, opg, do.

io. a css

2.20

KloWlOS&^.'CS.

5.

uooa, sj. s>eci>

6.

2.60

3.45

7. so.^<ao,o^,zjooa,-a,&<s

OF$

3.10

8. dJ. nJCCU, 15.

9. r’inoodj, So. R>rCj, io. a<S, CsJ 3.20

3.48

10. Or}, t/Ooft, io. acO, RkcU

2.96

11. Or}, eJOoa, do. &ccO

2.20

12. R>«3J,<W. StCb.O.’J

13. 15. &cO, ^Lraocdj.aJ. ar^o

0.64

3.19

14. d5. nJCCb, 15. ScO, UOoS, or}

0.50

15. TPUXJOlJ, 15(65 £>(O

0.85

16. doaoJLoO ?5(Oo

—

—

17.

18. BJaodJosJ acco

0.56

0.80

19. or}, uooa

0.85

20. doaod-uo &(Oo

—

—

21.

—

—

22.

—

—

23.

—

—

24.

26.

—

17

18

—

—

—

20

—

cdaf rL aj. ( aljRjrfVj)

- cdra

—

—-

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

rfejRJaS-

£>.3c5

&c3cJ

21

22

23

—

—

—

<35 ra '

dORJd - <35 ra

£^C5

24

—

25

£^d'Cf

26

27

28

—

—

UcSoa.SFj 8.50

—

UOoa, kJ. oowai. oo

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

Lj^toooa

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-

—

a>J(<v7i'Lt-2<J3, a. 15/ cCLxXo9

rfejafcs - aSra

—

—

37.32

19

<3R< tdaJ1, a. <6

^na^a<bcO5J dejrdd

.

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

A. R)., L/Ooa, r5. ayvdJ 6.76

—

—

—

—

RJOroaRl) ’

—

—

1.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

z< ?oooa, ?oooa 1.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—■

—

—

—

—

——

—

“

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

c^osFocf rtoacrf 1.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

W. ijKJKS

7.50

i .00

2 .50

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

' —

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

__

—

—

—

-6.75

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

—

8.50

—

S’ rGo

r>’.- ivy

n

ei'^v.72J 55c3rrJG> ctfRjo

*

2seJJoxj a5?uck>

jJoriy'-oco

f‘ /»¥••?. i

■■ -

Orx.VJli.JO

wr prOJO.'?

63_DOt53..t

5>O

*

•K«

&A>cr^r

*

coa'C

•

r \»aR»'oj

55/JrS3«J

ZuLJJ..

HOC^KkJ

oSortKx) S3 tt.

Zj.XjO

'□3C<

zdcJsmoii^rSc^

1 rfJFrrcjJ_.oc^ z^tfocctiio

ara;d/x

asos

y b’ozJsr. .

X fa>53 qcxijj

4

*

O^C.'

J ><“«i?

I’XinxJuZ- >OjJw ,

b RfuM-w

fi ry’FCfcj.

*

.OC? *

'

CtfOL?

7 oj53rrr>HJocy

mc5/xK»

X WO'FtxJ out.: .

cO?t> 6S.ICJ

9 & .o.rt lpwcu> ?c

*c7

<x.»_

tt7X_ijiis

*

o2k.

Hi

& .“»£•

o' .ej.d

anatf/b

lOnini'

e»o

I-1K

1

17

11-117

11

.‘4 or.

.';

O-i IX

.'4

1-9(1

.4 <6

275

64f.

)fi5(l

9K0

070

500

150

1000

3296

163$

1573

431

<■'••.•

XI

426

224

426

2723

—

r-'K’

l-l.c

‘>24

2o?

475

52

-

712

18

194

(‘IO

III)

225

1(10

50

75

22ii

Hun

125

Kf,o

♦ 49

Hl()

450

6011

250

260

10(1

-

285

-

.4 «_•

c>noc5r5

JO 3t'.»rLC751 <57

<!R5

385

.300

300

l-lll

I-1K1

. k5

90

418

265

213

♦ 18

,’<wo

91

f> 4 9

269

280

549

-

roOu'ijr*•

a^d/ACo)

J~IH

•”> )Ck> :v:>af nx

736

394

342

714

11 &Ftfcjj/-.n cW

l-lll)

171;

5111

♦ 40

917

8

12. ftccW? ETisrSe,

3-(111

soil

941

I8fl(i

975

885

1860

-

16

-

lX o>,.< 230)O

l-lll

‘M 5

1786

367

919

1723

-

63

14. EDru'-FrtriO TJcRJ^diiO

l-lll)

77

4 2H

262

218

397

-

23

15. WHJa5CD.dC5rDnC<

)-no

68(1

352

328

568

9

103

I i) rLocznoato’

2-iii>

139

250

1496

785

9

702

s-)ll

2B2

1529

75?

755

739

17 ^3o5.Jrrtr5o ^>cco53u£5ici

774

1421

14

94

22-1S

Shllf,

18631

9727

8904

12421

663

5547

289

Unini

19

iJorftZ/x^jx

1 nJ jr"$o3>J. n3r5«’~» . ?3n» . oSJCJ

rTjr.’V

,'i-(l I

n o5.

9 C5O'c’vn5p3 , i <JC<JFnJ

*,

DJjr?>/

?-9.7

11

I-ill!

X r^_

’

fl-117

X

’

II-| 4

$

X f\feflSlC5 a1*. 1 .FJmjC’.J On?

4 <OfC?

5 l3OUCt

H

iJ’OtJ TS'JUroS’jQj

O.UJCoF ITJUnTttChtf

gj£OC7 O7J.TFX“f

mQJJ7?

175

930

♦ 47

483

390

251

39 2

2134

lliil

1033

1595

445

94

341

14X4

731

703

r<«O

44

272

139

1XX

912

-

43

-

LfiO

94

bill

271

290

529

14

479

272

18

.-! (A>

')u7

1025

829

796

1386

232

7

r >- >

I'll

418

434

MO

138

279

24 8

241

452

37

-

4184

4113

570 4

1156

1438

wo

7 wd^alrorso. ri>—><xOor,?! .nirio

asanJ/’x

i-|4

x. udrprjrn.

2A/?.rY»

n-117

92

852

'48'1

x-xi!

)02«

X29 7

i oo exo. nwyi

,O.

t^CS^riicSftSS aL>/X:>tft/03

too

a?Jou .fsvj

nitorcs

cure

ni.t.cOs3

a<_>;yrW

alosS.

atcnfftS

MHix-'hi aS<‘ aitoal

<X)j>r«aSr(5ja a>rttt>st(<3,J,<3ftaS ales

osco

«o_uaS .oJu oft urteasrWj

tftaj uaf ,3 Z

-ftirf ,5 <3 (aoaJrftftjl

rSordCi

rSox(c3 toaSO

KiiSrf

.icOaS ain

14

5 on

A Svrt>. x5. Ct53ai> rfJt.nej0A.i-4 HO

M U.

D>ei « 75

t^Wtftdoa. to torsi

tj33._,a aSextsaaSj

3. 5(1

tSoalcS - oSro

sijcsn&bl

rfoaScS-

edjeJja,

oSn>

&aSO

22

17

<5-o> t-n»; ri^zrmoxj as ctnn

- wro

foaSQ

26

25

f5rOj; a5. cBa. ore.5. 00

a. ftiecift, aS ftjiaO, tj tJctooi 2. i>0 —

4.

o.8o

x5. cw«x>.

wii'j. al tftSFai.nn

7.

«,

9,

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

11.64

flPFtSj

<; »o

75

t-.i.'tJcioa U n! imai> 3 0(,

< 05

2. t?3tJ3c->oJ-’ a. Swr3>, aS anaJj, aS. tftsftaS

11 on

i<t./cSoa.aS on.uooai no

5. <1(1

a. R>c.. al, ariaij 1.50

rJStzsescou, VO'>ft>

■JftotJ 1; a,.

a K>,, TPinwaU

3. a. .t>cdj aS onaSj, tftc<oa. ti. tt>csj

KDj. rft.oS rJStft^ejalj t-tfttftcsoa

4. efcjj zJ

4. 50

;.looa tJ'hj-i , tft aS. art i.un

0.50

lu. tftOoa.aS. anK->. A. X>i. no

Uooa.fft lIDFBJ

II 5,1

2.50

<5 TbCCSj XPkDeJOftJ

X

2o. 55

27

—

to a ,?jc<o<a z> udoes

O.-54

5. tftSS.a FftoanaU

rfejaScS - osca

l). oil

it 75

1(1.00

6.00

28

(>W'j- (■

<X4Z^

TrcAP'

Bsnrus SjwiJ asanfow ajoa« - 3J1WU gcuarw

~DO-OG’Ja3X^) ESaJH

a,.Tifl,

Myodj ffifncu

anuu .BtJina awco

sU>U53d

m.ljfttf

1

2

3

4

5

nnFtfrs

0-20

,jvi(ssrt

oiansoj

IjUJj

noa;n>

JjOrfrtx) Sj,

0

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

3mo,

70

215

108

1395

215

920

130

530

376

70

270

363

373

256

62

370

211

112

203

248

334

860

135

1120

238

313

538

713

998

603

56

22

379

50

98

90

137

108

93

103

25

15

64

56

116

152

296

430

98

53

116

229

0-30

1-00

0-30

597

118

380

630

535

192

110

522

310

198

320

390

630

1450

313

2150

175

600

897

1120

1950

1150

170

615

162

16

115

131

110

308

32

80

56

81

117

167

185

376

111

1506

120

113

368

625

108

220

91

18

51

112

90

89

21

83

46

35

55

46

85

270

32

300

80

105

200

100

108

200

163

475

221

18

110

267

162

236

18

152

99

86

117

112

290

590

108

1030

237

257

359

677

962

617

302

81

53

397

190

58

87

81

149

644

34

592

239

228

539

677

1950

1150

24-12

3108

17370

9991

7379

5699

2588

51

100

20

60

80

173

309

500

131

500

400

1095

156

250

00

320

200

549

153

250

65

180

200

516

172

2(10

ISO

310

150

973

187

2935

1511

1391

1965

SS.So, -330

2j}O3(Rfrfcf

/

-----------------I. <S-n(noacnSjsDW

2, at/wlsja^ajorfu

3. tir3<sj_,mara

4,onrlaJu mairM

5.S5Jd^HDCDOUCOau mc3f^J

6,

z~nc5rrkj

Y.dLijSij rntitri

8,O^lC LDifFd

*

a.ensaco^ undca?

IQ , ZJr\j Sj j PJCrvf

11. eJ-ncGlsjj utJusJu mcdr^

12. ^o'&jjocass'j mcarnJ

13. usoatrano

14, 7tL/X53Jf tfjO

15. t9o

*biF5Sj

u maifKJ

16. sJjjfoodJXJj mc3fKj

17. roaj uarascd, sJjojfLPrtf

18. rrcj(dsiU/9 <uc

G5j^aaHjou

ig.woKkc^cf aJ<SD<tfo«j3

20.0013(0.0 roarffejj

21. s3oUo<i3Uj

22.^jtSO^ eneln<.%,aS^ ajaw/ OnJ

23.ajjaaosuSj roars

21.05^(550

dOOVjlO)!

1-00

'

0-17

0-07

0-19

’

0-18

0-25

0-25

’

r>.w>( sjoau)

0-25

5-00

0-11

0-06

0-03

0-32

1-00

1-00

i-io

3<4

tm.-tfrs

0-25

]-oo

rO.

nnaSA

U.M)

1-00

2-10

ru

rt>

3^

118

9083

4CT1MFSHC

1, siiym LDi(rt/ (Bqo

2.-aj%'O‘

cfn}

.1. "■>'>• Hn|

4.eJoa3cr;Pc3 fc((5XWo^ti)0 ajo.-yj

5. E6.)e_p^f rtjOLD

6. ^jCoSc/j cnelncft

cm,Tin

15.5,5

0-11

i-oo

riu

0-40

0-40

2-10

5-11

H«o.

rt>

SO

100

4

137

100

1

80

150

118

384

586

200

d,

RjO.

dcu-^jd-od

aj’oU4rlyb

B^tnccJ

orfra

efUjCSjd

djdd^

dod^

dra

»

1-1

15

16

1998-99 sit Fotod

c&w&drt&Q &r1Qs3aMjd dra

wodjsj^ojj cfl_n(2xjdrf^j

<Srtf. <ad, &. <A

cdd. r\ ot, ( djdriW)

dejxiuJ add

rfodd - dra

dcjrtcS - dra

rvCCd

add

&dd

17

18

19

dt$, udoa, sio. R>tco, to. acsj

1.46

d^, iido&, &mtx>M, to, ftcstf

4.93

daj, tide.?., c~wxj<xu, rd. R>tcl> 3.00

cjAoUmj' &<cb

0.03

—

_

—

—

_

_

—

—

_

_

do. SrdJ, d^: tJdoa, to. fttaf

o’o.accb.cf^, tJdoa.to. eicsi

—

—

—

—

20

21

22

—

_

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

23

du(£7>t>>Jed. a. 20/dXlnd

rfodd- dra

dudcS - dra

add

add

24

25

26

27

23

—

_

—

_

—

_

__

_

7.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

7.00

—

Zu. d. dd.d. d—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

LTidSddd

1.

2.

3.

t.

5.

6.

3.69

2.56

7. dn}, ddoft, r^tnoaij

2.26

8. d?£, ddo<3

0.90

9. d^, udoa, co. acd>, >o. atsi

3.18

—

—

10.

r^tJTOQdj

11. cfaj, ddo-S, id.

2.12

—

12. cfj Seek, d^r iJdo&t zo. &<d

—

—

13.

—

14. cfj. fttdJ, •Jdo&l 20<a £>cd

—

—

16.

—

—

IS.

—

—

17.

18. efo£joJjjd &ccO, ddofi

2.00

zJdo&' cfafr to. Qcsj

—

19. tfj.

——

20.

—

21. tO. S)(COr ZJdoftt rj^t 20. fted

—

22. do. £>cdJf zJdo&r zoeftfixd

23. rd. ftcdj, zJdoQ, d^t 20. e>cd, rP^noodj

24.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

—

fj^nzeddd

—

__

_

_

_

—

—

60

—

—

—

10.00

—

—

—

—

—-

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

26.11

60

10.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

adddoS u3!tjooU2. 50

—

__

_

—

—

—

a. zJdoa,d. unt z^tnooJj 1.00

Ed. ^cdo.d.codj,

1.00 i. d<dJ, d. ddd, odjjzeas. 75

ddoa

—

—

—

?3. andjr t^tjaoodj dodrj 1.00

—

—

—

—

—

_

_

_

—

—

—

—

_

—

._

—

2Jdo<a, d. aPKl) 2.00

_

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

•—

—

-r—

—

—

7.50

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-- — .

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

■

7.00

6.75

—

—■

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

( utf ctn. rltty)

0, tjCSPiAdoa

Wo.

riPeiiJjrMj

U

15

stinrd

a>C3

sSjWrtV

Wob5_,

10

uft^sSctJ

1. ?d, UsSkj,

nJ. anrtfJ, A. n)ccO

t^rJcfo^w. ftcsJ

2.26

2. cfa£, zJcfoa, rPtneoJj, enosrf

nocd, A. atcb, to. atsd

4.18

3.

1. a. »cob, t^^u'ooa.to. ats

2.8o

5. i.St. ,to.atsf,cl?J,tJOoa

2.80

6. T^LDOOJj, CfR}, ZJCtoa, Rj. Uo5nJ, i. ft. 6. 60

1,tS.mjs5 ui&, tPtjooodj.nn^Wrljai o. 60

8. W ®tr>o aaWtn^cS

g.tfjoiJrf uiffi, tJOoa.u. acsf

0.30

10. Wo%no3e>Wcn/vd

11.

12.

13.

14.

16.

16.

17

rntjicd 1998-99 Wt nnaW

cVx-wKjrt'tfa anasjanicsosj wcs

afti

aoJjW^QJj ciLnctcKJrfiA)

aW. aW. a, o’j

attf. A, <4. ( SjWrtW)

SejwS Wto

a’owa - Wes

tfuWtS asci

anana

rvdjoti

aao

aad

afro

17

18

128

33.00

72

—

17.28

—

tu. zJcfo^c^.zJctoia.Rjc^jaJ 3.60

--

18.60

13.00

—

—

—

--

a. ti. o^, u, usoa

--

1.00

--

u>. rJooft, zf’tnejoJj did^

—

—

--

—

-—

—

2.00

__

—

—

—

--—

--

—

60

40

•

—

—

—

—

-

-

19

20

22

21

_

_

—

--

t., tJcfoa, tfj. a<ob

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

100

81.70

__

—

—

--

—

__

—

6.76

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-—

—

—

-14.74

__

—

—

24

25

26

23

27

_

Gf^, tJcJoft, A. RjfZ3J5j-8 00

—

-

28. SO

-A

—

—

106.20

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

<8

—

—

--

—

177

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

--

23

a. a. U/sscVj.

tfowts- cSro efown - «rj

awcf

usra

--

-

--

7.50

6.76

8.00

226

136.00

<5Z^_JL_<Tj F <2_> FCS’

T^FWS'

g..iW.

syai) sfficU

1

2

ojivu saeon sajcu

3

oZS•JOCS'V?

-

Z3 A G_)—/ 4 T±r'J dJ A •'_

cgc3 e E^r^Q-?

rS'-/4 Q_/

^<asrfl

asoa

rwajej)

a5o054

wsjCohJj

7

8

9

11 MO.

0-30

128

•

1-32

177

aPHirs

0-16

3«o

170

■

ll«o

3-36

103

■

60

1-20

17 MO.

•

*

4-00

264

•

Ueo.

2-00

177

<L>rtnc?rt Wow>o3e>,Lc3 39

•

3tw.

0-08

45

Frf<5'y003e>r<>c5

22

rO.

2-10

233

■

lOcbrU

1-00

450

•

2274

■

■

340

•

1250

•

1753

600

700

600

300

200

900

475

205

250

60

400

1250

12500

900

5140

9450

470

1000

1015

1000

500

330

1400

885

349

300

115

620

2250

20000

1700

8140

16000

2350

7995

57954

.xLn€5o3j

4

6

6

noarO

coonFGj S. W,

10

S, So, q3C

11

12

13

500

515

300

100

130

400

200

50

100

60

120

400

200

200

200

50

500

450

40

100

40

200

1225

400

315

400

200

130

500

410

144

50

55

220

1050

7500

800

3000

6550

1125

100

300

500

200

150

500

236

259

100

15

300

2250

20000

1700

8140

16000

2350

35105

22849

2475

2380 53099

jJoriV-QCOJ

l.wsve> Lrt

2, onJonSFSC?

3. u^fca^nef

{.soften

o^elntR.M^rDsSj

5. fCSjf hJo. ii.ia^uencJjFcJaicJ

6,rtof&ocscn'&i^no 1

aSoj

7, s5o3U(UjQF3nc5

3, r^UjajiTTij-^kJ aZkJG?

Q.rtQc&ocJcn&i^urfcJ 2 tie aSo3

10.rfcHs5u zi-ocw

ll.H<?BcausSu snsi.

12, CT>Ovt4SrtC<

13, 7x. -c£. ^F>C5,

H.AjSOj enelz>cS>,?S, "d. s5r!C csgco

15, cot/, 15. c2, <5-^,

16, aSooUHTi.jjbj rrxarFJ

17. asowaUSrfO

R55->re>

■

19-62

(otj

ti lodrvvdJd djno?jLnd

do.

d3od_d^j

14

sjinrd

dra

15

16

rnoSddd

1, rJdua doand)

2.

3.

4.

5. zpLnooJj, A. fbcdj, ?z>. &cd.

d. and),

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14;

15.

10.

17.

2.60

—

—

—

8.00

cful^cbd

djdrf^

dorf4

mtnrd 1998-99

anod

olnc-biddij'a drdbdCkbdod dra

dra

ooJud oJj crlJKtedddj

dd, <d/, a, d

Od .-L. <$. (djddi/j)

tf odd - odra

fbrt&d

tfodd - dra

rfodd add

add

ddbd

add

dra

19

13

17

—

_

_

—

—

—.

—

—

—

_

_

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

6.00

10. 60

20 '

21

_

—

—

—

—

—

— A.fb.d.

U. US^6.76

22

_

__

_

—

—

—

—

—

-_

_

__

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

_

_

_

„

_

—

6.00

6.

2.60

92

36.00

~

2.00

-d. d. anad.Zo ddoft

6.76

______

-

—

—

—

—

_

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-—

—

—

—

_______

_____

-"

___

„

7.04

432

129.48

5.00

—

28

28

27

A. fbedb.

1 .70

—

—

—

—

—

—

A. fb., d, ctnrdj. 3.30

15. & c d, Zp kDOOJJ

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

__

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

48

36.00

—

—

—

—

—

—*

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

5.00

M.tf^d,A.fbcdj —

da£,ddo<5

' „

10. duandrtd da^oJj^cO^d.

11. dj andrid di^ouc^cb^d.

—

otbdyjj

tfodd - dra

add

____

-

—

--

dra

A.fbccbd^ 5.00

7. di^ainod^ end 'Qcb^d.

8.

<ft cb OT^oJj^cb^aJ,

9. djondrfd sy)jO^oJJ<^dJ^cl.

—

25

•

6.76

uddd rt)<B

iPtnoolj,rfja,ij7a, rf^dod'da}, 5.00

340

94.43

3.00

6, fb<dJ, t/doft, xiauf —

cfej^ tJdua rJdoa.d.ooarrb

drfcb, io fbfd, rfn^ncQj

2. ttn^d una

0.14

—

—

—

3.

_______

ddoa.d.cmdJ

24

A. de dad, o'.). fbed) —

1.

4.

5.A.&(db zJsiu<a

23

duc^n.bd

d odd

add

i —

6.75

~~

5.00

48

36.00

B.-WUS s.nvti

a wo

sJjoau -

atjau <swct>

soennv

sewn <.tssr;o>

wejnsiew^JivxrM s>^

s?j;ea3„

r^,rri>

naxt»

im>..

IDOtf! .

TsJnJRlOld

nociasi

jaoriwj a. m

si s°. -asci

■aeoi.^nc'

| ouCOdJGMFnj Un

*

C^£JU .

2 HJX3F MO 5

a fOsJf rto 7 crajdcid'c'f

4 aJoJuJFdoGJ cnourf

5 m^oirici

ri pboJF^o ki .

vd3c<

7 fOxSfkjo

c?c3jtVx<3

8 mASU So .s> ,a.,& af3O

9 rtzJF Fdo 13

wdrfo£l?3anJ.i

ID aLnodcrPclrtfrlrf

<=rtn JfC>

il-|7

fflWtfP.

3-'!8

3-9S

15-37

0-33

11 a5«w.:ojU .55"^ .

12 Sj'&OJJ UXJe'Zxi CoOU^-1

13 rt)o.,Hf rtxQHkJO

U FdslF sjo ti tsaJjrt^cfij

15 d S

ibcfljrud cB3d

Ifl s3^Q(Cf £>ueJ cbdjr^j u>n? C^XjLJ.,

17 woJ_> s> , nx^FFrt rsGUr</><■&

1$} U 10 VFTi ,:J C^OirfJOGl

111 FtJ6uFH3O 71, l3crtJ>r-t.> jMDU

20 rvcn^as.o cdJrvor-f iJ.orc^r *dai>O>

2| 76~ncsS.)CXi.^

?T^.rtUCt.,

22 r^rsSjrzi.^

23 mouusd. .Focdt;..

94 sUrt'KlCiStf,, tfd WOf'.'i;

•>5 Fdasr foo ‘>ii 55.' rl/FC sr> ,n.£■

9fi roe>..rff tb'C^nS trioxl &j>kL>c1> cW

27 notfc

^..

*

rnaifR-,

28 aScroj »«t/>Oorf >,n<5c?cA

99 ccL/wlor5'?<toi

3f| CJOWrilrOJjFCn

| F^CCOGinOFvJ culTD^cC'^

31 rnocncd_icoa5fC< l2

*tf< “WC3<3 ■“^F^ K>cj.,fFji~ry^Fr^

.12 aoijon entbx.t icojjw.-ic: iJ rw<>~

33 OD.rGorJ rt;ogJ55 <xjr>O zT»»^o?'..‘^x7-_'n

2-0 4

an?n/u.

FtfUOFC)

anSA

?-2n

0-23

n-29

0-38

0-I7

l-2u

l-lh’

4-All

n-,32

l-IO

34 njCn.-FDf Fb'o

36 rLcui^iiO a?J.*»or> ‘ utoceff .I'.cjmojiO

3fi zrfoJU5jrv"5 afotJorr mc.V>cK) iou‘1 ».oo. locrpsicfl to£j

'17 tf s^^jji'JiF^'inc^ .vcnpcuio

1O& <0

38 cdoa

*

cncJ/xX

wfcj -0

.39 rsOf^nlFfXl.i <TVr£f;TTJ ^nl m/',.~~l)tTln

4l) -,v,.U.io’.r5.-: |n$r WO K}bl -.<••■

*.

•.J-' i.'AJF-’i

17 wo.

3<w

3wo

U7

6I«

92

3 wo.

'!il#

2ii3

475

Ilwo

3 wo.

rtj

1117

40

3119

951

K54

11533

7117

n‘27

3715

Mil

HK2

25DH

49ii

12011

1519 .

2226

638

221

<1-96

IK

’10

1-35

•>-no

A-25

3-mi

3-< 10

134

.194

6.;n

‘151

2’20

1145

31X5

118

l-HI

anair.

.13

llwo

153

1 ICO

ll^o.

It!)

Il^o • 1480

|-;^o

l?S

3CJ>O

no

fl97

3 wo

ins

II <6

n-in

l-HI

1 -hl

n-21

l-<iii

44

.3 wo

11 wo

/-<■>

121

fl37

27

36

■l«3

2B3

5«>

17 1

4KI

311

1X64

241

339

ISIIl

269

343

186

489

2038635

621

1265

381

469

87

318

18

h

84

109

69

125(1

1875

474

351

23 fl

590

746

1126

261

til

3.3

831

1234

1000

486

180

40

4 20

883

19

292

inno

76

91

1901

375

1145

16

810

395

823

200

200

350

2nd

46

800

3838

320

4

84

247

225

-

453

311

38

1000

52

41

12

92

94

180

345

1185

23

83

349

789

250

412

52

37

471

1083

100

200

200

335

3224

I25d

254

616

773

uno

277

no

47

!’K0

4 9(1

109

319

20no

HI

774

3/

375

I74K

31

44 2

633

933

200

25n

275

1604

407

398

.170

.1439

530

2832

liX

2-10

2-in

1-40

0-3M

IM

189

8611

4 IX

1036

,'Wlli

IXKIi

503

953

3m.

fi'in

|-|<l

5-il II

2-IHl

i3<i

•inn

6511

3-<H

.17(1

139

145

1190

.•|-nii

3U|

4-21

3352

8n5

12'Hi

.1271

15211

280

461

111

326

1185

?9«

IT

i’ll

43

S7

86

1170

76(1

ion

3 if.

|-il(l

3|B

XX

linn

7 69

|5.l

1 -Hi)

inn

-

303

227d

IS III

251.

ISV’

3 <6

*>

!!(?

6

24

147

489

319

3309

381

Ifl2

462

350

4H0

38

48

24

21

8

1000

19

20

375

15

13

170

200

200

50

152

16

. 30 U

1614

600

741

98

4177

144

2386

20

164

3000

743

100

819

600

i5.

LjC3Art>C»_>5j a3>_oiOU-'i3

350

K?C1U .ilVj

>33

^jnlrU.1

u

<jji'.r

17

l!»

2"

*!l

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

-

5.00

-

-

t5^3aa_Vo3 rbers? d’juicj<.'JU

2.

I V

OrJ, tJCo<3 tfj> un& ou>%A

3.28

CF^, ZJCO<Ej .52L». R). tJC ,K5 CtPHkl 5.38

CRj.2JOOt3.rrt 2J5J«;

173

128

ft? V

*•0 88

2.50

tPTJJCJO.U

cJOogO. Sjc&>ort

7.

K

10.

Orrt. tJOo<3 20. iOczJ. rfy> wj&

i.?n

CkJ Udo<3 tJ^wjcxkU. 20 <5cx>

a. 38

1.90

D'J. &cOJ Caj.

1.23

eWt tJCoa dj. R>ccb. meJ. zPld. 2,95

—

9 (7

KjcCJ L/Ooti

Rj crtiFrtJ tPtn

J 07

11. Dj JCjcOj, io Scarf. t?^eJc_)OJL'

12.

Dj JbccJj zFwxuaU

zJc^oiA 3 76

13

d3tjkjoJlj aJ^rcb ScD

M.

2.51

15. rPtncjodi

'i. on

n nn

irt. DJ JtfCJ. 10 tbc^'l

—

—

17

>i »in

18. Dj .tirOJ, io ftcsJ

•i.ftn

19. dj Jbccb, tocfi> CjcO

—

20. tfj K)ccij io. e>cort

•i 34

21. OR? ZJOoft

UOot3l X5‘

22. ORj 2JCoa rJ^WX-'tW.

—

—

23.

—

—

24.

—

—

25

—

—

26.

cW.zJOo#

1 31

27. CfJ

-—

28.

—

—

29.

—

30 CfJ &fOJ. ^unc’-xXD CP. Die?

-31. DJt3CUJJE3 Kic Co. Frti .AlH M

—

32.

—

—

33.

-—

34. .

-35

—

■ —

. . ■.

36.

•—

37. DJC3OJLU5J rOfOJ O«?

—

—•

38

—

*>

CRj

39 0*6301 OoJ ".■CC'

--4(1

—

—

—

-—

—

—

—

-—

.•ill

-—

—

—

—

—

-—

----—

—

--...

ivx’J

(1 75

-

-

—

—

—

________

i

■

.

l"

fi

R

7

’ 9

If)

U

13

12

asia;r,

3-00

360

20 40

10(14

976

-

-

2040

HDA

3-25

.%<!

31100

2050

1850

IO00

1000

1900

<3. aJ3^ tioGt ft>oc3 djsViO^cn.jiu uzD&tsi shifted) ’

4-30

460

3300

17 65

1535

1000

1000

1300

44. r-fjc4>o3L>/53r S3,3. SoskncSrG'x.fikj mgvsjM

2-30

160

950

600

450

189

100

89

450

-

450

35

50

-

n-is

14

101

60

41

-

-

101

1)0-06

12501

(14259

33474

30 785

28056

9038

27165

41. KJr^ojuoca.

tJ

42. tfiFS-'SS^'oSSrfcf ucnsSt-a

45. OJjiEiccIjl/sOJ

4(i ent's;., l/w

■i'2so( Smmoa&.oCJ)

'

0-13

’

■

3<&

llew

189

22

4A. <4 4

33?

911.27

3. Oil

23

24

26

26

5.00

27

28

(ot/ dJ5.

o'Uudbs5

roared

<35 cd

KK).

Klon34

mmfcf 1998-99 sic nnasi

oOLn(«^Jrfy<a

cdrCf. <5\. oj

<35 cd

tooUaJjOJj cCLrcc'&iFdrteb

rfejfdcJ rfcjFdd asJcf

rbna

Sj<^rx>c0o5

ftcJcf

airs

<^cf. A co. (x&rtr-l&j)

airs

tfoaicJ - <s5cd

aad

a.a.a

rfotfcJ - s5cd

cx>_)( qZTDrvlxl

rfejaJcJ- <25cd

asicf

etfra

H

15

18

16

17

2.50

6.50

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

_

204

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

101.00

—

-—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

21

20

19

22

23

25

26

27

23

_

__

__

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

— •

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-

21

OD^2S ?3r5c5

1, rJOca, A. 3),

2. =. &ccij, c^, Ucioa

c.

■ —

z.

—

o.

—

C

—

7.

»

~

—

$.

—

1G.

IL

12.

—

—

-

I-

—

IL

—

Is, L^zJcioa, arj^jr-<c>2

zJcfoa

U. Su. tJdoa, c*r}, zJc5o<5, A. &ccb

17.

is.

is. 2 3-oVsj wa

—

--

2.53

7.51

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

0.97

—

—

20.04

204

101.00

d^,?Jr5oarBj. ijf A.

c^tdc&exsd

2.50

1.00

—

—

—

__

—

—

—

_

—

~

__

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

1.50

—

—

—

—

, G^tJctoa, A.Sxcb

—

—

—

—

—

cfjd.

—

A.

—

—

—

5.00

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

_

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

iji/J, oJ ozLjc5Fc5c5r2 6. 75

—

—

—

—

—

6.76

_

—

—

—

e'HDFUS’

tf,Kio.

SdCdCtfH^

M^JaU alMdi

28^Ip5TiCX)3 3^exnO’J5J0dd &53C?

dJiVtJ gdtticf alrtid;

ajitstrdj

a.^ttor

3

<

6

12

jLocsjrf

rcamtu luUJj

rfodstU

aSorfal) 3d,

sd, odo. •Qdd

8

7

8

9

10

11

12

17«°.

118

387

128

116

22

194

120

270

1302

421

660

116

689

287

1019

1421

220

96

1303

666

3748

435

618

137

2976

309

944

386

460

95

601

238

871

1414

201

89

1112

696

3602

376

460

126

2800

497

1689

388

800

96

660

160

1200

1390

342

60

1900

360

1480

276

323

220

2080

80

300

200

86

223

166

120

160

60

40

160

60

260

480

580

2020

96

366

890

5610

66

76

42

1676

16319

14889

14114

5106

11989

13

crj^xnteTjrfci

tforft/ncOi

■

l.rfSrfVSn} LPA(ftf-l

KDH^rs

2.t?nand cn.TJdOjWj

rtenra

-3. 'a.o&cn^Jrfcf

snnJrs

4. to zine sorted

6. ■£. &, Kind, o^mcnojjra.tm

6. du&ousi

7. itelntad.d spofl, tooi^id, -.SKftfl. a>sf ioa «d

8. ^nsXjooadrtd 6 iptf

o.53jC>oU3Sjdsnu4 ,3 KjPjpa1 cnuwrtrici'

lO.aj&fcirtf RJc5Jvtfo$d Snit^pcT

11. Stuaj5ndrO?5, rt, no. is, SddaJUa

12. rP dsJjFtfrfcf, w5tfuocli3-)53eJt

Ftfo, 113

13. B'jSPnKloclKjr-fd

»a <6

14, SWOJ-PndCCdrdrdCd

15,rLncdrOoLlsr>«'J,i:Soaa wcnHrf

jg. lines sml'j

17. wi^o murd, CDwMKlrtd 6 KJe^pcr '

iS.-oo&crWrfd,Y/.0.

3 nt cBo3

0-20

1-00

1-00

6-30

6-36

1-00

0-20

3-00

4-00

20-00

2-29

1-20

0-12

7-26

347

464

84

29

385

202

1184

136

161

42

927

679

2246

807

1000

210

1190

626

1890

2836

421

186

2416

1250

7360

810

978

262

6776

67-01

5094

31208

1-26

2-20

1-06

3

mo

•

6

76

477

119

—

30

407

209

570

1286

19 '

19. daonn unitin' -2

5KDHJS tS-WU KMXLWWJ SUon.j -

s,atonv

M^piCPlx/aSosncSO asci

—

b; ^°.

M^odj al.’CcU

rfodal)

rttattfoo

8.WJ scStBQ aSKOi

.J-rO

S>03

slonl4

d. do. •Qdd

crfoddJ d.

fcJddonl

—----- —------------------------------------------------------------------- — —— ————

1

—

3

4

6

6

7.

— — —— —

—

dod«Locbt

A

2

-------------

8

9

10

11

396

6043

3006

1200

3948

6423

1769

1667

3000

1082

6000

634

1002

4688

4674

3192

816

4660

630

926

866

1638

10625

1734

1730

10200

1586

2628

774

1965

3660

122

1092

4361

1617

205

2936

1606

624

2064

3342

921

818

1572

668

2661

281

637

2398

2436

1696

439

2406

326

494

462

803

5569

918

042

6382

835

1389

428

1002

1879

68

689

2288

868

190

2708

1440

676

1884

3081

848

749

1428

614

2349

263

466

2190

2239

1497

377

2166

305

431

403

736

5066

816

790

4818

730

1239

346

963

1681

64

603

2073

749 .

317

3001

1476

192

606

2013

969

953

1050

365

1600

346

362

2306

2969

1500

471

2260

295

360

665

1106

5036

865

12

----- ---------

13

tnjz-fddUjj

—

1. <3. <S. snelncft, ar>aiji.Jsr>i7u

2;Jtfo3r do. 4g, tfdU<Ddr~fd

3.Rj5jf do. 4g, tJoGpdnd

4.dJdcdjd LnAcrc/ tddjdj

5. r»orLnoddd«tj

6. ddcuocS, dciaaid

7, -ao. -M. drfd

S.cnsZctfjdddd

9. ctj-wtLo c ariodri d

.TSenrS

10.OTrfnsjS«d,ertnd 2 sJtaSod

■

11. daeortSrfcf

12..cndjda> uxi/xR)

la.Mrijqfalcf

H.rCrfr ttio. 30,31, m.tJcrl>cOs3?tfa<Va

HDFtfrs

dcnfd

■

anMr\

•

dmcb

•

lo.fCSjr ™o,aa,39,40 SBtftlotg

•

ia.»oiJcc3aOsJrfci

17. ,biejr1(ddJL dcd?<nQd

rmdr\

18. SBaJotg, to. -ottf. <5 H.f-dsJrsJo. i

lOrLtV

IS.nJslr KJo. 21,uslrfon'e> 2 fdc cGo.3

20. itslrao, 23.8^4slJjm^e.T}, u. eS.-fl. rf, 1]

21, dncducdjd

22. wodcdddddd ,100

dn?

23. Mj3o^ snv4

24. cf-rtcdduorfo 7 dud.] 8

ioa

26. tf.n(d.djodo irJo^ptf d.ndoL>od)t»

2fl,L/ou$ waidi-a, tJCOodSddd

27. do^oJjrnofoRjrid, W. 0. da} 3dcdo3

28. v.oijwdorn'yjeo(31^rld1 W. 0. daj 3 aJod '

29,tJjo<K> endn<?t>, v/.o, cf^.3 010^,2^47

3O.tV>cs> epttocfb ,314,2 y^tf.3 Hit «fo3

31. uredpia.’Sricf , Sj:cU3Sr(ci

32. enrttoafirte

33. nJsJrrso. 32, aJjawjnct), snrftCo^

34,ddfdo. 7. tfbcdoGj

35.MSJC njo. 23,tf6<fCog

3-08

26-03

9-02

2-19

16-30

19-26

2-00

0-27

7-06

0-30

16-00

1-00

1-10

9-02

3-24

2-16

3-00

6-20

1-06

3-02

1-36

6-15

1-30

ifl-00

3-20

4-10

2-18

3-00

8-16

0-20

1-16

4-10

2-26

3«o.

11£

3o5

rtf

3

wo

rij

3

3«o.

neo.

rt)

66

1014

468

197

624

1169

360

228

294

211

800

89

200

698

696

616

136

760

106

166

160

206

1860

289

273

1660

240

438

129

359

600

20

189

716

252

78

1448

264

59

365

849

202

414

600

21

700

89

166

1108

866

890

179

730

116

200

1194

1276

949

2978

3661

598

200

1350

696

2700

100

496

4680

650

1000

350

900

1066

160

2500

440

OOH

3000

500

950

275

806

1000

1175

940

802

166

1680

220

375

210

273

3090

429

OOO

2620

415

678

149

250

1495

62

200

2000

380

35

200

1000

500

1496

737

000

(otf dn.

ludrvvdd

BJWJfUj

JDWFCJ

c6ro

aS co

?0O,

aJosS^

M3

16

17

1998-99 dr ?mdd

cOjacw^rft^a ^dada<vdjd adra

woJUsJ^odJ olnc?^rH;b

cdd. <da/_ a. «□

edd. oj. o5. (djdnvj)

Rjn&Sd

&dd

rfOdd aSra

rfodd - edra

rvdOoS

©dd

dra

19

18

21

20

22

23

-•—

*<vKl

tfcxud- adca

s>sJcJ

25

24

cd. a. io

rfodd - fidra

s»so

27

—

—

28

i

1

26

tnj^dcdy^

UdOft, A. s>, JO. C\ tfjO. Wi' l^LH.

2.50

2. da}, tJdoa. dj. £>. d, io e>, x$j\ ua, d. d, 6. 46

3. d^t Udoa, A.

dnua, 3 rtn, t <0. exsfll. 05

—

A.d^.Udoa, A. n»cc&, t>vtJdo<a

5.50

5. d^, ddoa, A. a, 10. a, T^tnooU, t±/a, J-nil. 62

—

1.

6. — c?df - .esd/acrf^ ^Juo'

7. &$, Ud°a, A. ft, dn. tnf tJjavxSu

8.d^(udoa,iota a>cd.

9. d^, Udoa, A. n>,Hi. d, &n, ua, TpvnooJJ

12.

13. cs.tj, uooa, *

. a, ». a, tPuxxuj

1.50

14.uaj, Lfooa, a. a., *

;, >j,a. a, <<y>t7xaj

15. C^, i. a, rfjitn, u. a, 3. rto, t>. 1J&0&

8.50

6.10

31.

32.

33.

34.

35. ■

-

”

-

-

-

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

A.^(dO,daJ,t/doa

1.00

d;g,zJdoa(?oca> acd

1.00

daj, Udoa, andadc^

1.00

•

—

—

—

—

—

-

—

—

—

14.50

0.76

2.70

—

_

— ooHa, eno. rV2(altdJ. tJ. 6.75

dcSrtQCGlFd^, cJdoa 1.00

cJrfr zJdoa, rfja w^bt A. R>d. 50

8.45

3.58

i.oo

10. tlntfsJ Lr-a

U.d^UdocS,A,Sc,tfja ?_jaa

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

—

—

—

—

.

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

t odja(e>/dd3fddoa 1.00

d

*

d^,2Jdoa, T^tncxxu d)dej 1.50

__

_

__

__

—

__

—

—

—

_

—

-

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

— •

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—-

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

--

—

—

—

_

—

—

—

--

- ._

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

__

—

—

2

3

36.KfK!rKfo. 24 tfBe.Tfocf

37. rtfsJrWo, 29 ojuaodlnci),

38. Uzrttrtrtcl, u.

iJ H afo

39. awcmWrld

40. wstalcfrtfrfcf

41. sXj)C>o3j;3ju

•

•

■

42. cnr\rt)<3o

43,aV)ts3octJjd

44.5r?incftJ) slr-lcJ

45. snoxWcJcnwjmcSrKj

40.003 c/ui^ro rfco<2

47.^owKDttftneVxft,i3, <X tf. 2 aSo3

48. aModjffXlrxlb, 13. <3nf. rf. 2 o6od

49.10. <30.

cndew af.^cf '

GO.tjcC. rf. sljcJ vucjdnsoa

61. rf. «o‘. dnj OT^dotfUo

62. tfoskndnnaJX) 2 «Io3

63.ul™. Orfcf

64. WOrOo, 21, tfBoTfo^.Tncra,

56. nISr KJo, 21,ae>O‘VotS (<T3,%no3e>AcJ)

56. tfoOUidsnirBoO

jO.jrl( Shilled)

67. enHCTWWrfcf, 15. <O.Tf. a 2 Oo3

58. <4)osUl c3t®>

69.«cl)oc33 ^nrj

lOrtxV

•

60. cjtjrocrwtfrtfrfcf, rf-««30Uor-fo

6I.™cnoalfKJrtcf

Riepre)

02.eoiJfc3d<3slrf0 rs5o3;3 sdV_,

a5enr&

63. CDioodtcIjCJ Ftftsn Oom

RJepfC)

64.4V)C<at rnOJO O^rsO tf-o. sj

ajcnrC)

13

11

12

300

140

760

1000

700

302

1867

300

400

62

408

300

100

600

926

600

196

1264

0-10

1148

191

612

636

62

201

371

170

4571

2399

769

2172

688

4096

2180

1916

506

3038

1694

1444

476

148

898

422

400

3125 2826

1087 6960

2839

232 1675

835

740

1000

680 3482

1810 1672

2068

42

189

163

352

200

306 1815

905

860

842

824 6408

2814 2694

2896

930

326 1966

1035

666

398

330

122

728

349

116

699

329

370

360

39

218

120

98

108

218 1302

698

604

600

79

24

139

60

69

69

229

188

417

167

21

126

69

57

42

30

29

12

72

42

456

179 1074

578

498

79

212

474

262

217

100

38

229

129

107

3066 114968

7133

6796

7825

668

290

263

604

, 104

’ 816 3790

1819

3118

1971

208

101

416

216

199

20

104

50

88

54

66

16

162

—

245-32

26864 168298

33066

66651

7

6

4

2-00

0-30

6-26

5-00

4-06

2-00

8-07

3-02

6 -12

0-18

3-00

6-20

8-10

1-00

1-07

0-20

2-10

0-16

0-38

0-14

0-10

4-13

1-92

0-25

2-10

1-07

—

—

<e-<e-

1

8

9

ID

83220 75078

69681

275

1018

100

606

1186

1327

600

910

106

274.

180

167

48 .

62

302

400

28

62

86

176

28

66

19

24

218

400

96

162

48

74

3000

6163

—

64

'688

84

648

131

3321

2170

1838

'1

20

—

43.

44.

45.

46.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

22

23

—

—

-—

—

—

--

—

24

25

26

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

.. —

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

27

28

_

4 0.

41.

42.

4 !.

46.

49.

50.

21

.

—

~~

—

—

—

—

—

—

-—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

84.88

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

_

—

__

—

__

_

—

—

— ZJ.

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

eta}, iJcfo<a, A. £>ccU

ma

—

—

—

—

—

—

1.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

1.00

1.50

0.50

1.00

13.00

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

--

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

6.75

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

-—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

•

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

12

3

1

5

6

8 •

7

9

II

10

12

13

36.d5Jrdo. 21

2-00

191

1118

612

636

300

300

37.dsfrdo. 29 aUfloJlnd), dMddocJ

0-30

62

201

170

HO

100

131

36. ’Jsrthddd, a, <anJ. rf |[ do

39. odlndl^drfd

6-25

0-00

769

371

1571

2399

2172

760

600

3321

688

1096

2180

926

2170

1-05

2-00

8-07

3-02

0 -12

0-18

3-00

0-20

3-10

1-06

1-07

0-20

2-10

0-16

0-38

0-14

500

148

1087

232

680

12

306

821

326

122

116

39

218

21

69

3038

1915

UH

100

1000

10. wddddr-fd

11. dJsaodjdJL ddd

700

600

196

1251

276

1018

100

666

1186

910

271

1836

12. QWlMo

13. Antd-JC d jd

H.C.-tf-pdiJi ddd

4 6. d-idKxljdcnedmcfrd

16.dud rfui/i rfcod,

17. djo?2.>.7TidmdnctV>, u, <.7rt/. rf. 2 dod

43.®'MalJtrxlnf.%, W. •artf. tf. 2 dod

19.».«ao. <aaf. tndtM dojd '

50. wd. rf, skid tnJ^ddHjj

Si.o’.ud. dnj

'

(nl^dd^tj

52. tfJS<ndnn<r>J 2 dod

63.Ar,.drld

Ol.ddrdo. 21, tfCxdocJ, <mdAt

OS.drfr do, 21,tfCxrtloig (iVTwiodC><t>d)

‘

5<j. tfjdJ>dn>Arl6od r/jj>ddJjJk>r1( Shifted)

57.0>W<nxddrld,u. £>nt. <J 2 dod

68.dejdJL dtm

69.Mdood3 ddd

io,l„6

60.u^CTOJddrld,rf.z>cddjodrj

•

,

01.7,mi„drdr1d

dcnrd /

02.Mot3td4dddd ,dodd tm;

63.cnittodc^oCj nJ<«oi

O4.nntf&d rys&jti

vSj\

dcnro

irJmro

rtfvnrO

0-10

1-13

1-92

0-26

2-10

1-07

—

—

o-io

216-32

•

•

•

•

•

3-i

3 "5

3 i

3 S

21

898

6960

1676

3182

362

1816

6408

1905

728

699

218

1302

139

117

120

1691

176

<22

3126 2826

710

836

1810 1072

103

189

966

850

2811 2694

930

1036

398 .330

329

370

120

98

001

098

79

229

09

12

60

188

2839

1000

2068

200

812

2890

665

319

360

10 8

600

59

167

12

67

30

196

29

166

212

100

7133

208

1819

199

60

83221) 76078

72

12

179 1071

171

79

38

229

3066 11958

■ 101

668

816 3790

101 / 116

104

20

678

202

129

7826

290

1971

216

64

20801 168208

302

1867

300

106

62

108

>327

600

106

180

18

302

28

86

28

167

62

400

62

176

66

217

107

6796

601

3118

208

88

19

218

96

48

8000

64

81

56

16

21

loo

162

71

6163

09081

33000

56661

688

162

648

UjocSh -

a.vnrsjcr

S,So.

aiddj

gdftfd aiaJcb

istpsncJjssxmsrosncu &&&

djxJEJdj

a^ccar

4

5

3

12

dorfK'jxiM

sjdjtjrtv

ricdafJ

riofidtu

6

atorirtj s3.?&.

?J. ?jO,

8

0

10

11

579

2246

309

944

388

460

96

601

238

497

1689

388

809

95

669

160

1290

1390

385

202

1184

135

161

<2

927

807

1000

210

1190

526

1890

2836

421

186

2415

1250

7360

810

978

262

5776

270

1302

421

650

116

689

287

1019

1421

220

96

1303

666

37 48

435

518

137

2975

89

1112

595

3602

375

460

125

2800

342

60

1900

360

1489

275

323

229

2080

2020

56

76

42

1876

6094

31208

16319

14889

14114

5106

11989

7

13

12

cnanaxlrfd

l.rfbj^JK; b&Afrf -1

sDajfs

2.Md'3r-d OTtiddUg

-3. 'Qo&cnKjdU

4.Miln<tfdrfd

5. &. A. ddd, u^KncooJUrHid

S. dj&aUsfj^md _,

ajtnrb

sjwtfr\

to,W

7. Ajdntdjd

tooijvl,..ssfa. ad ioa a

3. tndaxifidrld 5 yitf

9. djidolJd.jdJTidj ,3 ;!(yd unowarld'

lO.asawd desndod

11. Sft„dj<ndrd;5,d.do. jj, ftdddag

12. rP jdjddd, acW uocltndd, kJ. So, [ < g

13. eTjSPndocJddd

:.-a a

H, naiolnKJodKJdd

[6. rtntdrOodsn V _,, doa.a ucndri

16.21/X& ZW/j

n.LDSit^o dtJrd.cninMdrid 6 dtyic# '

ig. ■5oacndrld,W. O.daf 3 d< asod

|9. rfandKj Lnicrtf -2

1-25

2-20

1-05

-

17 MO.

118

387

128

115

22

19{

120

3

0-20

MO

1-00

5-30

6-35

1-00

0-20

3-00

<-00

20-00

2-29

1-20

0-12

7-25

57-01

317

464

84

90

,

871

1414

201

6

80

300

76

477

119

—

200

85

223

166

120

180

570

1286

60

40

19

95

160

60

260

480

580

-

366

=90

5610

30

407

209

SnJirijiS S.nwi! SSJntwf xkjoau - cLnwif

S, ;tto,

Mrjau iitnlcu

?/iy»3>eAnw.>s.n'.t> msi.-.f

iJJrJcWW ,r,1W>

SUWCfd,,

m.t;(toc

,J-<O

HoHnb d. w.

d.rlo, -q-W

rW3;iff»

;.,i.uu

nlo;-(

nlonl

?.:r.fnlon1

6

7.

8

9

10

11

12

13

66-^

396

6043

3005

1200

3948

6423

1709

1607

3000

206

2935

1606

024

2064

3342

921

818

1572

508

2661

190

2708

1440

676

1884

3081

848

749

1428

614

317

3001

1476

192

606

2013

969

953

1060

78

1448

264

69

866

849

202

414

600

1194

1276

949

2978

3661

698

200

281

687

2398

2486

1695

439

2406

326

494

462

803

5509

918

942

5382

835

1389

428

1002

1879

08

689

2288

808

263

406

306

1600

346

21

700

89

156

rfodM)

--- -_---- — l.«a. rf. oielocnj, erwdLn^snV

2:<SsJr So. 46, tfslxjiSrfd

a.ssr so. 4o,jjog;.-atftj

•

l.cOtgcriyzf Ln4fn/ .Oci>Sj

S.rfo.'toocJrtfcO«»3

s. sdtwod, gsasKJ

7. -^o. m. rfritf

a.cn^.ctJj&Sr-fd

3. cnwrtncsTwjSrftJ

10.SrtnSsJ«o,er5nd 2 ScSod

rxnnirs

nltjjfb

•

11. dSKOG^rid

12. cndorta nxln<Ri

13.Ml4jd.tic!

H.SSr So. 30,31, nTiScrOdbedSSOtf

Enn)r\

•

16.SSr So,23,39;40 tfCXSorg

16.tfoiJcd,cfSdc4

17. wejr1cdiiju dcd.mad

18. tfOdoiJu. .j.Tf. rf

H.SsJrSo. 7

IS.WSr do.24,wSrJorjC; 2 Sc S03

20. ddtdo.23, sdcslJbsijCfn},is. rOS, rf. H

21.nln(djftijCj

22.«od<dtddr4rj ,100 fjQ cfnj