[Untitled]

Item

- extracted text

-

The New England

Journal of Medicine

©Copyright. 1997. bx the Maxsjchusetf. Medical Societx

VOLUME 337

Si 1' 1 EMBER 1«, 1997

number

7 *; r

12

9j

^SIS IN U^??M

A TRIAL OF THREE REGIMENS TO PREVENT TUBERCI

§An

ADULTS INFECTED WITH THE HUMAN IMMUNOD ^^gNCY VpA

Christopher C. Whalen, M.D., John L. Johnson, M.D., Alphonse Okwera, M.B.,

M.S.,

Robin Huebner, Ph.D., M.P.H., Peter Mugyenyi, M.B., Ch.B., Roy D. Mugerwa, M.B., Ch.B.,

and Jerrold J. Ellner, M.D., for the Uganda-Case Western Reserve University Research Collaboration

Abstract

Background Infection with the human immuno

deficiency virus (HIV) greatly increases the risk of re

activation tuberculosis. We evaluated the safety and

efficacy of three preventive-therapy regimens in a

setting where exposure to tuberculosis is common.

Methods \Ne performed a randomized, placebocontrolled trial in 2736 HIV-infected adults recruited

in Kampala, Uganda. Subjects with positive tubercu

lin skin tests (induration, 2=5 mm) with purified pro

tein derivative (PPD) were randomly assigned to one

of four regimens: placebo (464 subjects), isoniazid

daily for six months (536), isoniazid and rifampin

daily for three months (556), or isoniazid, rifampin,

and pyrazinamide daily for three months (462). Sub

jects with anergy (0 mm induration in reaction to

PPD and Candida antigens) were randomly assigned

to receive either placebo (323 subjects) or six months

of isoniazid (395). The medications were dispensed

monthly and were self-administered.

Results Among the PPD-positive subjects, the in

cidence of tuberculosis in the three groups that re

ceived preventive therapy was lower than the rate in

the placebo group (P = 0.002 by the log-rank test).

The relative risk of tuberculosis with isoniazid alone,

as compared with placebo, was 0.33 (95 percent con

fidence interval, 0.14 to 0.77); with isoniazid and ri

fampin, 0.40 (0.18 to 0.86); and with isoniazid, rifam

pin, and pyrazinamide, 0.51 (0.24 to 1.08). Among

the subjects with anergy, the relative risk of tubercu

losis was 0.83 (95 percent confidence interval, 0.34

to 2.04) with isoniazid as compared with placebo.

Side effects were more common with the multidrug

regimens, and particularly with the regimen contain

ing pyrazinamide. Survival did not differ among the

groups, but the subjects with anergy had a higher

mortality rate than the PPD-positive subjects.

Conclusions

six-month course of isoniazid con

fers short-term protection against tuberculosis among

PPD-positive, HIV-infected adults. Multidrug regimens

with isoniazid and rifampin taken for three months

also reduce the risk of tuberculosis. (N Engl J Med

1997;337:801-8.)

©1997, Massachusetts Medical Society

"W" NFECTION with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

|

niost C0inn1011 human infection worldL wide. As the epidemic ol human immunode-A^ticiency virus (HIV) infection continues to

evolve, the risk of dual infection with HIV and

M. tuberculosis may be substantial in young adults,

especially in developing countries.1 HIV Infection

confers the greatest known risk for the development

of tuberculosis, both tor the reactivation of latent in

fection and for progressive primary disease.2 5 More

over, once active tuberculosis develops in HIVinfected persons, mortality is high, despite good

clinical and microbiologic responses to antitubercu

lous therapy.611

Pre\enti\e therapy has been proposed as a strategy

to control tuberculosis in I llV-infectcd popula

tions.12 l4 The potential benefit of preventive therapv

w as first suggested by observational studies of injec

tion-drug users,2-31516 but these were uncontrolled

studies of selected populations at high risk.17 Data

on the efficacy of preventivc therapy in HIV-sero

negative persons1^22 cannot be readily extrapolated

to HIV-seropositive persons, because of the con

founding effects of progressive immunosuppression

related to HIX infection and concern about an in-

From the Division oi Inlectionc Diseases. Department of McJkiiu

I nixcrsiix Hospitals <>t ( lexeland ami ( ase Western Reserxe 1‘mxersitx

'<<"•11 I . D I H . I J.l .i. ami the Department ol Eptdemiologx and

Biostatisncs. Case Western Reserxe Unixersitx K ( W > — all in ( kx'eland.

the Lgandan Ministrx ol Health, Xation.il Tuberculosis ami Leprosy Pro

gramme lAO >. the Joint Clinical Research Center r I’M .. and MakeiVie

I mxersitx < H D M — all in Kampala. I ganda; ami the ( enters tor Disease

Control and ITcxcntion. Atlanta iR.H • \ddrvss reprint requests to Di

Whalen at the Dept ol Epidemiologx and Bitistatistics. WG 49. ( ase West

ern Reserxe Cnixcrsitx. 109(10 | uclid Bhd . ( lexeland. OH 44106 4945

Other authors were I’ctcr Xsubuga. M R . ( h B . Ministrx o| Health.

Kampala; Michael \ |ccha. M D.. I mxersitx Hospitals of ( Icxcl.’.iu! an«l

( ase Western Reserxe Cnixcrsitx. ( lexeland. Harriet Mxanja. M B . ( h I!

M Med. Makcrcrc Cnixcrsitx. Kampala. ( issx Kuxo. M B._ ( h l’. . Joint

( limcal Research < enter. Kampala, and \nita Loughlin. M S.. John Mil

berg. M PH . and \ ukosaxa 1’ckoxK, M D . Ph D .'all of Cnnersitx Hoc

pitalsot ( lexeland and ( ase Western Rescue I nixcrsnx. ( lexeland

\oltiinc 337

Xu nt he i

12

801

I hc Xcu Enei.ind loiirn.il <>! Medicine

creased risk of drug toxicity in HIX’ infected per

sons.2’-4 Because of the relevance of preventive ther

apy to the strategy tor eliminating tuberculosis in

the United States and the potential benefit of pre

ventive therapy in targeted populations in resource

poor countries, in March 1993 the Uganda-Case

Western Reserve University Research Collaboration

began a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of three

regimens of therapy to prevent tuberculosis in HIVinfected Ugandan adults w ho had positive skin tests

with purified protein derivative (PPD). In October

1993 enrollment was expanded to include HIVinfected persons with anergy with respect to PPD

and Candida antigens, on the basis of new informa

tion suggesting an increased risk of tuberculosis in

HIV-infected persons with anergy.’4

METHODS

Study Design

The objective of this randomized, placebo-controlled clinical

trial was to determine the efficacy of three daily, self-administered

regimens of preventive therapy for tuberculosis in HIX' infected

adults. The trial was designed to obtain at least three years <>f fol

low-up data on all enrolled subjects, with annual interim anahses

to ensure timely detection of risks and benefits to the partici

pants. All subjects gave oral informed consent before screening

and enrollment in the study. The study protocol was approved bv

the institutional review board at the L'niversitv Hospitals of

(’leveland and Case Western Reserve L'niversitv and bv the L’gandan National AIDS Research Subcommittee.

Study Population

Between March 1, 1993, and April 20, 1995, Ugandan adults

IS years or more of age were screened for enrollment at live med

ical clinics and counseling centers for persons with HIX' tvpe I

(HIX' 1) infection in Kampala, Uganda. Enrollment of subjects

with anergy was begun in October 1993. In the PI’l) positive co

hort, enrollment in the isoniazid and isoniazid-plus-ntampin groups

was continued beyond the predetermined sample size to allow us

to screen and enroll subjects in the anergy groups. The study's

inclusion criteria were HIX' infection documented by enzymelinked immunosorbent assay, a PPI") skin test showing at least

5 mm of induration after 48 to 72 hours or anergy. and a Kar

nofsky performance score of more than 50.-; Anergy w as defined

as 0 mm of induration in reaction to both PPD and Candida an

tigens. Candida antigens were used for skin testing because teta

nus-toxoid and mumps vaccinations are not routinely used in

Uganda. Only one control antigen was used, to enhance accept

ance bv the subject. The exclusion criteria were the presence of

active tuberculosis, previous treatment for tuberculosis, use of an

tiretroviral drugs, a vv hite-cell count under 3000 per cubic mill:

meter, a hemoglobin level under 80 g per liter, serum aspartate

aminotransferase level over 90 U per liter, serum creatinine level

over 1.8 mg per deciliter (160 jzmol per liter), a positive urinary

(i human chorionic gonadotropin test, residence more than 20

km from a project clinic, advanced HIX’ disease, or the presence

of major underlying medical illness unrelated to HIX' infection.

Before entry into the trial, all the subjects were screened lor active

tuberculosis bv a history taking and physical examination, chest

radiography, sputum microscopy with the Zichl-N’eelsen stain for

acid-fast bacilli, and sputum mycobacterial culture

Intervention and Randomization

The four study groups received placebo (250 mg of ascorbic

acid per day for six months); isoniazid I 300 mg per day for six

802

•

September 18, 1997

months); isoniazid <300 mg per day) and rifampin (600 mg per

dav i lor three months; or isoniazid (300 mg per day), rifampin

600 mg per day i. and pvrazinamidc (2000 mg per day) for three

months. Blocked randomization was used (in blocks of six) to as

sign eligible subjects to one of the study regimens. Sequentially

numbered, sealed envelopes containing the treatment assign

ments were drawn in numerical order by a data clerk. Subjects

with anergv were assigned only to the placebo and isoniazid groups

bv a se|varate, but identical, randomization process. Instruction

about HIX’ and tuberculosis and counseling on compliance were

given to all study subjects at enrollment and during follow-up

clinic visits. Study nurses dispensed the medication in prepack

aged envelopes containing one month of doses with oral and

written instructions. A team of five experienced home health vis

itors traced rhe subjects who did not keep scheduled appoint

ments and encouraged them to return to the clinic.

Assessment of Outcome

Hie primary outcome of the study was the development of tu

berculosis; secondary outcomes included adverse drug reactions

and mortality . The subjects were evaluated monthly during the

first six months of the study and every three months thereafter.

Active screening for tuberculosis was performed at all scheduled

and unscheduled visits by means of a standardized evaluation of

the symptoms and signs of tuberculosis; chest radiographs were

obtained every six months. If tuberculosis was suspected on the

basis of symptoms, signs, or the chest radiograph, three sputum

specimens were obtained for mycobacterial smear and culture.

Decisions to initiate antituberculous therapy for active tuberculo

sis were made by on-site investigators after reviewing the clinical,

radiographic, and microbiologic data.

( ases of suspected tuberculosis were referred for independent

review and classification by two ehest physicians who were blind

ed to the subjects' treatment group. Subjects were selected for re

view it they had at least one of the following: symptoms or signs

consistent with active tuberculosis, a sputum smear positive for

acid fast bacilli, a positive culture for M. tuberculosis, abnormal

findings consistent with tuberculosis on chest radiography, or

empirical therapy for tuberculosis. The reviewers independently

classified suspected cases of tuberculosis according to operational

definitions of the disease.-’'’ Definite tuberculosis was defined as

culture-confirmed disease (more than five colonies of M. tuber

culosis}. Probable tuberculosis was defined as a clinical illness

consistent with tuberculosis on the basis of at least two of the fol

low ing findings: results of chest radiography consistent with pulmonary tuberculosis, smear of tissue or secretions positive for

.Kid last bacilli, or a response to antituberculous therapy. Suspect

ed cases that did not fulfill the criteria for definite or probable

tuberculosis were not considered to Ise active tuberculosis.

During the treatment phase, the subjects were screened for ad

verse events at all scheduled monthly visits or unscheduled visits.

Medical of ficers recorded the type and grade of reaction with a

standard grading system for drug toxicity in HIV-infected per

sons.’ 1 he medical officers and study subjects could not be formallv blinded to the treatment because of the discoloration of

body fluids produced by rifampin; however, the medical officers

were instructed to perform the clinical examination and record

the findings without reference to the treatment code, and they

did not have access to the results of urinary testing. Mortalitywas

assessed through interviews with family members or review of

hospital records when available. Autopsies were not performed.

I hc date of death and reports of prominent symptoms at the time

of death were also obtained from family members.

Measurements

Demographic and clinical information was obtained through

standardized interviews and physical examination. At the time of

screening, venous blood was collected for enzyme linked immu

nosorbent assay testing lor HIX' I, complete blood and differen

tial counts (Coulter T540 svstem. Coulter Electronics, Hialeah,

/

THREE REGIMENS TO PREVENT TUBERCULOSIS IN UGANDAN ADULTS WITH HIV INFECTION

Fla.), and serum creatinine and aspartate aminotransferase meas

urements. HIX’ infection was documented by enzyme-linked im

munosorbent assay (Recombigen HIX’ 1 env and gag ELISA,

Cambridge BioScience, XVorcester, Mass.); 1 in 10 HIX-1-positive and l in 25 HIX’-1-negative scrum samples, according to

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, underwent confirmatory

testing bv HIX’-1 Western immunoblotting (BioRad Novapath,

Hercules, Calif). At the time of screening, all the subjects under

went Mantoux skin testing with 5 tuberculin units of PPD (Tu

bersol, Connaught Laboratories, Swiftwatcr, Pa.) and 0.1 ml of

Candida antigeif (Candida albicans allergic extract, Berkeley Bio

logics, Berkeley, Calif; 1:50 final concentration). After 48 to 72

hours, experienced observers recorded the results ol each skin test

in millimeters. Posteroanterior chest radiographs were obtained at

base line and at six month intervals during follow-up.

Before randomization, at least one sputum specimen was col

lected if the subject was able to produce sputum. All sputum spec

imens were digested, concentrated, and stained for acid-fast bacilli

by the Ziehl-Neelsen method at the Uganda Tuberculosis Inves

tigations Bac etiological Unit in Wandegeva. Sputum smears were

graded according to the number of acid-fast organisms seen on

light microscopy." Specimens were cultured for A/, tuberculosis on

Lowenstein-Jensen slants, incubated at 37°C in air, and examined

weeklv for eight weeks or until positive results were seen.

Compliance with the prescribed regimen was assessed by the

subject’s attendance at scheduled visits, urinary testing for isoniazid

metabolites (Mycodyn Uritec, DynaGen, Cambridge, Mass.), and

self-reports. Ninety-seven subjects in the three treatment groups

were randomlv selected for unscheduled tests for urinary isoniazid

metabolites performed at home between clinic appointments at the

beginning of the third month of preventive therapy.

Statistical Analysis

The intention-to-treat approach was used to analyze the data

for the primary and secondary end points of tuberculosis, adverse

drug reactions, and mortality. The incidence of tuberculosis w as

estimated bv the person-year method; the cumulative proportion

was estimated for adverse drug reactions and death. Efficacy was

estimated as the relative risk (with 95 percent confidence inter

vals) of tuberculosis in the treatment groups as compared w ith

the placebo group. The sample size was calculated separately for

the PPD-positive and anergy cohorts to achieve a power of 80

percent to detect a reduction of 67 percent in the incidence of

tuberculosis with an overall type I error of 5 percent. The sample

size was adjusted for expected mortality and losses to follow up.

The target sample size tor each treatment or placebo group was

410 for the PPI') positive cohort and 500 tor the anergy cohort.

A global test of significance was performed with the log-rank

statistic to compare the cumulative incidence of tuberculosis in

the treatment groups with that in the placebo group. The nomi

nal significance level, according to the Lan-DcMcts error-spend

ing function,-”' was 0.032 when adjusted for a second interim

analysis in which 47 of 56 expected events (84 percent) had oc

curred in the PPD-positive subjects. Three pairwise comparisons

were then made between each active treatment group and the

placebo group. The tvpe I error for these pairwise comparisons

was adjusted for multiple comparisons by using the nominal sig

nificance level from the global test to obtain an adjusted tvpe 1

error of 0.011 lor each comparison, preserving the overall, studywide tvpe I error of 0.05. A similar procedure was used to adjust

the significance level lor the subjects with anergy.

following reasons: active tuberculosis (smear- or cul

ture-positive; 185 subjects), HIV-seronegative or in

determinate (703), failure to return for skin testing

(28), PPD-negative (374), abnormal chest radio

graph (884), previous history of tuberculosis or use

of preventive therapy (96), poor performance status

(233), pregnancy (160), age greater than 50 years

(223), or residence more than 20 km from project

clinic (226). Information on the progress of subjects

through follow-up is available elsewhere.*

In both the PPD-positive and the anergy cohorts,

the treatment groups were balanced at base line in

terms of demographic factors, performance status,

and the results of laboratory tests (Table 1). During

follow-up, the numbers of subjects who withdrew

from the study, moved out of the study area, or

could not be located for unknown reasons did not

differ significantly among the study groups. The

mean number of scheduled visits, unscheduled visits

due to illness, and chest radiographs per person did

not differ significantly among the groups. Urine

tests for isoniazid metabolites were performed in

1754 subjects in the treatment groups (90 percent),

and 75 percent of the results were positive; the re

sults did not differ significantly among the treat

ment groups. Of the 97 subjects randomly selected

for a single spot check at home between clinic ap

pointments, 78 (80 percent) tested positive for iso

niazid metabolites. The subjects with positive re

sults on the spot test had a higher proportion of

positive tests at the regular monthly visits than the

subjects with negative tests (82 percent vs. 46 per

cent, P<0.001).

At the second interim analysis, in December 1995,

isoniazid alone was found to reduce the risk of tu

berculosis bv 67 percent in HIV-infected adults with

positive tuberculin skin tests, although there was no

significant difference in mortality among treatment

groups. Because the benefit of preventive therapy

with isoniazid satisfied conservative criteria for statis

tical significance, the study investigators and officials

at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

the funding agency for the study, concurred that pre

ventive therapv with isoniazid should be offered to

the subjects randomly assigned to the placebo group.

Tuberculosis

In the PPI') positive cohort, 138 subjects met the

criteria for new cases of tuberculosis after a mean

RESULTS

Between March 1, 1993, and April 20, 1995, 9095

subjects were screened and 2736 were enrolled in the

study. Of the 9095 persons screened for the study,

4306 did not complete the base line evaluation and

2053 were ineligible for the study. Persons screened

for the study were not eligible for one or more of the

‘Sec XAl’S document no 054 IS lor 2 pages of supplemental\ material

Order from XAl’S. e/o Microfiche Publications. P.O Box 3513. <>rand

C'cntral Station. Xe« York. XV 10163 3513 Remit in advance 'in I' S

funds onlvi S7.75 tor photocopies or S5 tor microfiche. Outside the l^s .

add postage of S4 50 for up to 20 pages, and SI.00 lor each 10 pages ol

material thereafter, or SI 75 lor the first microfiche and SO.50 lor cash mi

crotiche thereafter There is a SI5 imoicmg charge on all orders lillcst be

fore payment

Volume 337

X umber 12

803

I lie Xcw England Journal of Medicine

Table 1. Chakai ii rimk \ 01 ihi Sii py Si hik is.*

Characteristic

PPD-Positive Cohort

iMisiAZin,

■ \=464l

iMixiAZin

‘S = 556<

kii virix

is = 556i

I’lRAZIX VMIIM

Is = 462 I

,s - 525

51

50

91

51

29

91

29

29

91

54

29

91

51

50

90

14

22.1

14

22 6

15

22 5

14

25

25

2200

2500

2500

126

616

S9

125

645

SS

127

6S0

S6

n m 11:< i

Male M.-X i ".i i

Mean age ivri

Kamiitkkv performance

score

Bodv-mass indexj

1’1’11 skin test i mm ofindu

ration i

Previous herpes zoster or

thrush i

Absolute lymphocyte count

< per mm!i

Hemoglobin ig/htcri

Person-years of observation

C. ompletion of trial i’Vi

Anergy Cohort

Im >\l V.ll',

KII VMH.S.

ri v i ini

iMisivzin

. s 595

52

50

9(1

21 9

o

55

55

2200

2ooo

2ioo

12o

125

52"

S5

125

SO

so

*CJtcgoric.il x.ikies were compared by the chi square test lor honiogcncm . omiiniioii- x.ilucs were

compared by analysis ot\ anance. I’l’D denotes a tuberculin skin test unh punlicsl proiem slcni.urc.

•fThe body mass index xvascalculated as the Height in kilograms divides! In the sspiarc <■! the height

in meters.

\

follow-up of 15 months. Forty-seven cases of tuber

culosis (24 definite and 23 probable) were observed.

In this cohort, the cumulative incidence of tubercu

losis was greater in the placebo group than in the

treatment groups (P = 0.002 by the log-rank test)

(Fig. 1A). In separate pairwise comparisons of indi

vidual treatment regimens with placebo (Table 2),

the relative risk of tuberculosis with isoniazid alone

was 0.33, a statistically significant value. A similar ef

fect was found with the isoniazid and rifampin

group as compared with the placebo groups; the rel

ative risk was 0.40, but in this comparison, the effect

narrowly failed to meet the prespecified adjusted lev

el of significance. The relative risk of tuberculosis

with the three-drug regimen was 0.51, and the esti

mate of the effect was of borderline statistical signif

icance. The relative risks of tuberculosis in the treat

ment groups as compared with the placebo groups

remained unchanged for isoniazid and isoniazid

with rifampin in a proportional-hazards regression

model after adjustment for age, sex, body-mass in

dex, hemoglobin level, white-cell count, Karnofsky

performance score, history of HIV-related infection,

and presence of chronic diarrhea or weight loss. Af

ter this adjustment, the relative risk with the threedrug regimen decreased to 0.43 and was of border

line statistical significance (P = ().O3).

When the analysis was restricted to definite, cul

ture-confirmed cases of tuberculosis among the

PPD-positive cohort, the relative risk of tuberculosis

with isoniazid was 0.22 (95 percent confidence in

terval, 0.06 to 0.77) and with isoniazid and rifam-

804

•

September 18. 1997

pin, 0.14 (95 percent confidence interval, 0.03 to

0.62), w hercas the efficacy with isoniazid, rifampin,

and pyrazinamide was unchanged.

In the anergy cohort, 66 subjects met the criteria

tor the blinded, independent review after a mean of

12 months of observation. Nineteen cases of definite

(9 cases) or probable ( 10 cases) tuberculosis were de

tected. The cumulative incidence of tuberculosis was

similar in the placebo and isoniazid groups (P = 0.68

by the log-rank test) (Eig. 1 B). The relative risk of tu

berculosis in the isoniazid group was 0.83 (Table 2),

but the wide confidence intervals did not exclude the

hypothesis of no difference in incidence rates. In a

proportional-hazards regression analysis adjusted for

age, sex, body-mass index, hemoglobin level, white

cell count, Karnofsky performance score, historv of

HIX’-rclatcd infection, and presence of diarrhea, the

relative risk of tuberculosis in the isoniazid group as

compared with the placebo group declined to 0.75,

but the confidence intervals remained wide. The rel

ative risk of definite tuberculosis was 0.75 (95 per

cent confidence interval, 0.20 to 2.79).

Adverse Drug Reactions

A total of 304 adverse events were reported in 279

subjects during the course of therapy in all studv

groups, including the placebo groups. The frequen

cy of any reported adverse event in the PPD-positive

cohort was greater in the treatment groups than in

the placebo group, and it was greatest in the group

receiving the regimen containing pyrazinamide (Ta

ble 3). Treatment was discontinued in 43 subjects.

THREE REGIMENS TO PREVENT TUBERCULOSIS IN UGANDAN ADULTS WITH HIV INFECTION

PPD-Positive Subjects

O.IO-i

o

Placebo

5 0.08•o

co

_c

0.06

~

0.04-

E

0.02-

=

___ J

J

3RHZ

3RH

6H

O

0.00

0

2

1

Follow-up (yr)

Study

Group

464

536

556

462

Placebo

6H

3RH

3RHZ

288

280

104

306

109

282

87

88

Subjects with Anergy

0.10-1

o

c

<D

•u

0.08

Q

_C

0.06-

Placebo

<D

>

□

E

D

-6H~~

0.04-

0.02-

o

0.00-0

d

Mortality

2

1

Follow-up (yr)

Study

Group

Placebo

6H

323

395

The most common reason for stopping therapy was

the development of rash or pruritus (25 subjects),

followed by nausea and vomiting (8 subjects). The

frequency of rash increased from less than 1 percent

in the placebo group to 5.8 percent in the group re

ceiving three drugs (P<0.001 by chi-square test for

trend). No cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome were

reported. Arthralgias were more common in the

treated groups than with placebo (1.5, 2.8, 3.1, and

10.8 percent of subjects in the groups receiving pla

cebo, isoniazid, isoniazid with rifampin, and isonia

zid with rifampin and pyrazinamide, respectively).

Paresthesias were more common in the group receiv

ing isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide than in

the placebo group (6.5 percent vs. 2.4 percent,

P<0.001) but were reported with similar frequency

in the groups receiving isoniazid and isoniazid with

rifampin (2.4 and 3.1 percent, respectively).

Seven cases of clinical hepatitis w'ere detected by

medical officers during the routine evaluations. Of

the 1631 subjects whose serum aspartate aminotrans

ferase levels were measured during therapy, 65 had el

evated levels. Fifty-two of these subjects had peak ele

vations of 135 U per liter or lower. Of the 13 subjects

with values greater than 135 U per liter, 6 were subl jects with anergy who were receiving isoniazid; 5 were

. PPD-positive subjects receiving isoniazid, rifampin,

and pyrazinamide; 1 was a PPD-positive subject re

ceiving isoniazid; and 1 was a PPD-positive subject

I receiving placebo.

167

155

8

13

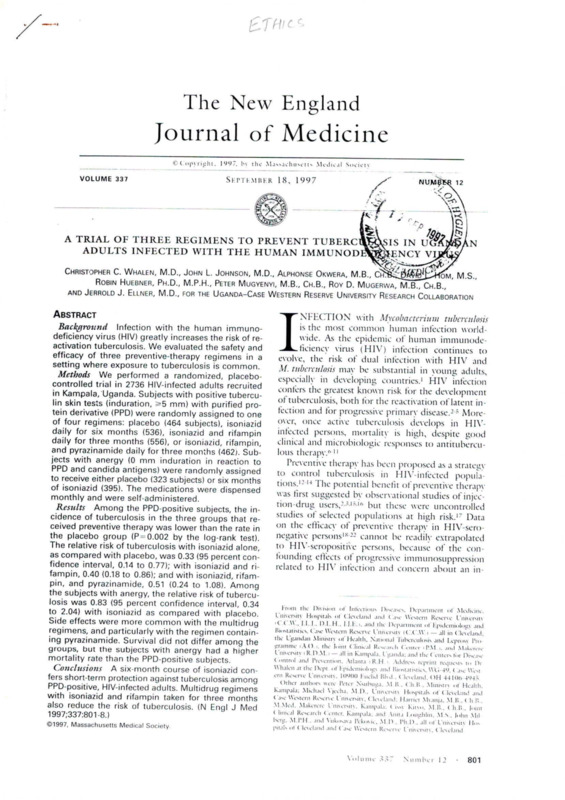

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Tuberculosis among PPDPositive Subjects (Upper Panel) and Subjects with Anergy

(Lower Panel), According to Study Group.

For PPD-positive subjects, the incidence rates of tuberculosis

in the groups receiving preventive therapy were lower than the

rate in the placebo group (P = 0.002 by the log-rank test). For

subjects with anergy, the incidence rates of tuberculosis did

not differ between the placebo and isoniazid groups (P-0.68

by the log-rank test). 6H denotes patients receiving isoniazid

for six months, 3RH patients receiving isoniazid and rifampin

for three months, and 3RHZ patients receiving isoniazid, rifam

pin, and pyrazinamide for three months. The numbers below

the graphs are the numbers of subjects at risk.

During follow-up, there were 399 deaths: 237

among PPD-positive subjects and 162 among sub

jects with anergy. The overall mortality rate was

greater in the anergy cohort than in the PPD-positivc cohort (P = 0.001). The proportion surviving at

one year was 0.78 in the anergy cohort and 0.90 in

the PPD-positive cohort (P = 0.001 by the log-rank

test). When the analysis was stratified according to

the presence of anergy, there was no significant dif

ference between placebo and each treatment with

regard to cither the mortality rate or the cumulative

proportion of deaths (P>0.2 by the log-rank test)

in either the PPD-positive cohort or the anergy co

hort (Table 4). Of the 66 subjects in whom tuber

culosis developed, 13 died, for a cumulative mortal

ity rate of 20 percent.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized, placebo-controlled clinical

trial of therapy to prevent tuberculosis in HIVinfected Ugandan adults, self-administered isoniazid

taken daily for six months reduced the risk of tuber

culosis by 67 percent in subjects with positive PPD

skin tests (induration, ^5 mm). This level of short

term protection was achieved with a minimum of

adverse effects. The cfficacv of isoniazid in this studv

Vo I u inc 3 3 7

N u in b c r 12

805

I hc Xcw England Journal of Medicine

Table 2. Ixcidi xii oi Defixiif or Probable Tubeiu itoms A( <ordixg io

Study Group axd Ri iativf Risk of Tuber< itosis.‘

Group

Definite or

Probable

Tuberculosis

Crude

Relative Risk

(95% Cl)

Value!

Adjusted

Relative Risk

(95% Cl)t

9

10

3.41

1.08

1.32

1 73

1.0

0.33 (0.14-0.77)

0 40 id 18-0 Soi

0.51 10 24-I OS >

0.01

0 02

0 OS

1.0

0.32 (0.14-0.76)

0.41 (0 19-0.89)

0 43 (0.20-0.92)

10

9

3.06

2.53

1.0

0 S3 iO 34 2 04 i

<) os

10

0.75 <0.30- I 89i

P

ML < >1

< AsFs

PPD-positive cohortH

Placebo

Isoniazid

Isoniazid, rifampin

Isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide

Ancrgy cohort

Placebo

Isoniazid

21

*CI denotes confidence interval The relative risk is as compared with the placebo group

fThc P sallies were determined with the Wald chi square Matisiic I hc nominal critical value was

0.011. adjusted for the second interim analysis and multiple comparisons with placebo.

{The relative risks have been adjusted for age. scs. white cell count, hemoglobin lesel. Karnobks

performance score, bodymass index, history of HIV related infection, and presence of chrome diar

rhea by Cox proportional-hazards regression anahsjs

§ The rate is the number of cases per 100 person vears

PPD-positive denotes a positive tuberculin skin test unit purified protein derivative

Table 3. Cvmltauxi: Ixcidexce oi- Aim km Evi xis, Gkade oi Ri.u nox ix Stldy

Sl BJECTS, AXD ErI-QI EXL Y OE DlSCOXI (XT Al IOX OF THERAPY ACCORDIXG IO STUDY

Group axd i hi Presexce or Abm x< i of Cui axeous Axergy.

Group

Cumulative

Incidence of

Reported

Adverse Events

Discontinuation

of Therapy

Grade of Reaction

Mil i>

M< >1'1 KA IF

MA FRF

number (percent)

PI’l) positive cohort*

Placebo

Isoniazid

Isoniazid, rifampin

Isoniazid, rifampin, pyra

zinamide

Ancrgy cohort

Placebo

Isoniazid

23 (5.01

60 i 1 1.2)

54 (9.7)

1 14 (24.7)

23 (5,0>

56 <10 4)

48 (8.6 >

101 (21 9i

22 (6.8)

31 (7.8)

22 (6.S)

29 (7.3)

0

4 (0.7)

o 11.11

12 (2.6)

0

0

0

1 (0.2)

13 (2.3)

26 (5.6)

0

2 (0.5)

0

0

0

0

1 (0.2)

3 (0.6)

•Pl’D positive denotes a positive tuberculin skin lest with purified protein derivative.

was similar to the efficacy of 71 percent found in a

randomized clinical trial of isoniazid in Haiti,-’0 but

the current study addressed some of the methodologic issues raised about the Haitian study.-’1 In

particular, the current analysis was based on a larger

number of cases of tuberculosis, with half the cases

confirmed by sputum culture. The incidence rates of

tuberculosis were lower in the current study than in

the Haitian study, perhaps as a result of the stricter

entry criteria used to exclude subjects with actixe tu

berculosis. Nevertheless, the consistent findings of

806

September 18, 1997

these two studies, in addition to the preliminary re

ports of other clinical trials,32-’-’ support the validity

of the observed protective effect. The duration of

this effect, however, remains to be established, since

variability in the annual risk of infection among

populations may affect the risk of tuberculosis after

preventive therapy has been completed, especially in

persons with advanced immunosuppression.

The current study extends previous observations

by evaluating the safety and efficacy of two multi

drug, three-month regimens, isoniazid and rifampin

/

THREE REGIMENS TO PREVENT TUBERCULOSIS IN UGANDAN ADULTS WITH HIV INFECTION

/

/

, paresthesias, were detected more frequently in the

treatment groups than in the placebo groups and

were more common in subjects receiving the regi

men containing pyrazinamide. Because medical offi

cers were not blinded to the subjects’ treatment as

P

Mortality

Relative Risk

Value

(95% cut

Rate*

Deaths

Group

signments, it is possible that this observed difference

resulted from detection or reporting bias. Nonethe

no. (%)

less, since these regimens arc intended to prevent tu

PI’D-positive cohort^

berculosis in asymptomatic or minimally symptomat1.0

64

(13.8)

10.2

Placebo

0 44 1 ic persons at risk, the treatment should not produce

0.9 (0.6-1.2)

58 (10.8)

8.9

Isoniazid

0.25

0.8 (O.5-1.2)

8.3

57 (10.3)

Isoniazid, rifampin

unacceptable side effects. Although the reported side

0.83

0.96 (0.7-1.4)

9.8

58 (12.6)

Isoniazid, rifampin,

effects

were not severe, they may have led to higher

pyrazinamide

rates of noncompliance or to the withdrawal of ther

Anergy cohort

22.3

1.0

76 (23.5)

Placebo

apy by physicians.

1.05 (0.77-1.42) 0.77

23.5

86 (21.6)

Isoniazid

In this study, short-term survival did not differ

•The monalitv rate is the number of deaths per 100 person-years. Total

significantly between the placebo and treatment

placebo, 625;

person-years for the PPD-positive cohort were as follows:

I "

groups in either the PPD-positive or the anergy coisoniazid, 652; isoniazid and rifampin, 689; and isoniazid, rifampin, and

hort. If the survival benefit of preventive therapy is

pvrazinamide, 589. Total person-years for the anergy cohort were as fol

lows: placebo, 340; and isoniazid, 367.

conferred through a reduction in the tuberculosis•fCI denotes confidence interval.

related case fatality rate, then the use of isoniazid in

JPPD-positive denotes a positive tuberculin skin test with purified pro

i the PPD-positive cohort prevented 14 cases of tu

tein derivative.

berculosis and approximately 3 deaths, assuming a

I case fatality rate of 20 percent. Thus, a large, ran

domized clinical trial of preventive therapy would be

and isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide. These regreduction in

imens substantially reduced the risk of tuberculosis, , needed to detect a clinically

. important

.

the relative risk of cause-specific mortality from tu

but the reduction did not reach the conservative level

berculosis. However, the absolute difference in the

of statistical significance. These regimens were in

mortality rates observed in this study between PPDcluded in the trial because of the greater sterilizing

positive subjects receiving isoniazid and those receiv

activity of rifampin,-’4 with or without pyrazinamide,

and because of the potential for improved compli- j ing placebo may indicate important public health

benefits in terms of survival if preventive therapy is

ance with shorter regimens.19 In addition, fixed-dose

combinations of these drugs arc available. The slight ! used widely in HIV-infected persons. The concluditference in efficacy between the two- and three- i sions regarding survival arc limited, however, be

cause the average duration of follow-up was short.

drug regimens may be due to the greater frequency

The implications of the findings of this study deof adverse events associated with the use of pyrazin- ;

pendI on the setting and the target population for

amide and its possible effect on compliance.

preventive therapy. In the United States, where the

nreve

In this study, there was evidence of a small benefit

annual risk of infection and the incidence of tuber

of preventive therapy with isoniazid in subjects with

culosis

are in general low, preventive therapy in du

anergy, but the confidence intervals were wide and

ally infected patients is both a standard medical

did not rule out the null hypothesis. The reason iso

practice and central to tuberculosis control. In deniazid did not confer the same degree of protection

in the subjects with anergy is unclear. We speculate_• J vcloping countries, where dual infection is common

that subjects with anergy may be at greater risk than | and continued exposure to infectious cases of tuberculosis is likely, preventive therapy provides benefit

PPD-positive subjects for primary failure of preven

to the individual patient, at least for a short time,

tive therapy because of drug malabsorption’5 37 or

but the effect on tuberculosis control remains to be

other host factors associated with advanced disease.

established.

Alternatively, exogenous reinfection with progressive

primary disease may occur because of the more ad

vanced degree of immunosuppression.

Supported by .1 cooperative agreement with the ( enters tor Disease

Control and Prevention (ADEPT/H1V Related Tuberculosis Demonstra

The safety of isoniazid as preventive therapy in

non Project, l’78/< ( 1'506716 ()4) and by a training grant from the

HIV-seronegative persons may not be readily extrap

1-ogartv International Center at the National Institutes ot Health (AIDS

olated to HIV-seropositive persons, because of the

International Training and Research Program, TW 00011 -08).

enhanced drug hypersensitivity associated with HIV

IVc arc indebted to the following members of the study team: ad

infection.4-1’-24 In the current trial, no serious toxic

ministration — I., (iaiy. M. Kasnjja, S Kibende, M. Manning,

effects were reported with six months of isoniazid,

,4. Nakayiza, and P biasitje; eoanselors and interviewers —

and the rate of clinical hepatitis was similar to that

(>'. Hwamikt, K Kyariihanjja. and K. (ialiwanijo: data manajjeis

observed in HIV seronegative persons of similar

— P. Bajaneza, 11 (Iwatndde, .S'. Katabalwa. /.B. Mtikasn. M. ()dii\

(.’. Opit, (>'. Olupot, and A. litryaninreba; dispenses — A. Abenage.-’K Other side effects, such as rash, arthralgias, ami

Table 4. Mori ai ity Kvi e and Cvmllative Proportion

oe Dea ms A< <orbing to Stvdy Group.

<

<

4

4

<

I

Volume 337

Number 12

807

The New England Journal of Medicine

i

/

I

/

aL-yn and L. X'dcncmtt; drii'crs — E. Kanniva. H. Kalninera. (>'. I.iinnnuba. R. .\hikasa, and L. Orycma;filing—G. linkmva. /L Mnlyabintu, and R. Nansnbiuyu health educators — IV. Rajiindirire

and .\f. Mwanje; home health visitors — K. Kataliwa, M. Kato.

/. Mnlabbi, and /. Nakibali; laboratory — K. Edmonds, P. Kataaba. .S’. Kabcnqera. ]. Okiror, E. Piwowar, H.S. Tnanme, and R.S.

Wallis; medical officers — IV. Ruknln, F. Byckwaso, A. Gasasira,

P. Kyambadde, H. Lttzzc, A. Matceyja, F. Mnbiru, C. Mnkuht, and

R. Odekc; microbiolotiy — T Aisu, E. Hatantja, and A. Morrissey;

nurses—J. Kaynnjjirizi, C. Kiramba, M. Mnlindwa, G. Nalnjiwa,

A. Rivamncece, and G. Tnmnsiimc; radiology — A. Adongo and

E. Katcndc; study coordinator — P. Langi; and tuberculin skin

testers — G. Mpalanyi, P. blasozzi, S. Nyolc, and G. IV/inii’n. II?

are also indebted to S. Okivare, Ministry of Health; M.G. AhvanoF-dycgn, director, AIDS Information Centre; F. Engwait-Adatn.

head of the Ugandan National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Pro

gramme; and the clients and staff of the following organizations:

AIDS Information Centre; Joint Clinical Research Center, the

AIDS Support Organization, Mulago Branch; the Post-HIV Test

Club, Kiscnyi; Good Samaritan Counseling Centre; HIV/AIDS

Clinics of St. John’s, Rubaga, and Nsambya Hospitals, Kampala,

Uganda; Drs. E. Villarino, A. Vernon, P. Smith, and R. O'Brien

and Mr. L. Gcitcr of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

for their scientific contributions to the study design and analysis; to

Drs. T.M. Daniel and F. van dcr Kuyp for their independent review

of incident cases of tuberculosis; and to the subjects who participated

in the trial.

REFERENCES

1. Narain IP, Raviglione M(’, Kochi A. HIV-associated tuberculosis in de

veloping countries: epidemiology and strategies for prevention. Tuberc

Lung Dis 1992;73:311 21.

2. Schvyn PA, Hancl D, Lewis VA, et al. A prospective study of the risk

of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodefi

ciency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1989;320:545-50.

3. Schvyn PA, Sckcll BM, Alcabcs P, Friedland GH, Klein RS, Schoen

baum EE. High risk of active tuberculosis in HIV-infected drug users with

cutaneous anergv. JAMA 1992;268:504 9. [Erratum, JAMA 1992;268:

3434.1

4. Guclar A, Gatell JM, Verdejo I, et al. A prospective study of the risk of

tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients. AIDS 1993;7:1345-9.

5. Antonucci G, Girardi E, Raviglione MC, Ippolito G. Risk factors for

tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons: a prospective cohort studv. JAMA

1995;274:143-8.

6. Whalen C, Okwcra A, Johnson J, et al. Predictors of survival in human

immunodeficiency virus infected patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: the

Makercre University Case Western Reserve University Research Collabora

tion. Am J Respir Grit Care Med 1996;153:I977-81.

7. Pcrriens JH, Colebunders RL, Karahunga C, et al. increased mortality

and tuberculosis treatment failure rate among human immunodeficiency

virus (HIX') seropositive compared with HIV seronegative patients with

pulmonary tuberculosis treated with “standard" chemotherapy in Kinshasa,

Zaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:750-5.

8. Nunn P, Brindle R, Carpenter L, et al. Cohort study of human imnni

nodeticiency virus infection in patients with tuberculosis in Nairobi, Kenya

analysis of early (6 month) mortality. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992,146:849

54. ’

9. Chaisson RE, Schecter GF, Theuer CP, Rutherford GW, Echcnbcrg DF,

Hopewell PC. Tuberculosis in patients with the acquired immunodcticien

cy syndrome: clinical features, response to therapy, and survival. Am Rev

Respir Dis 1987;136:570-4.

10. Small PM, Schecter GF, Goodman PC, Sandc MA, Chaisson RE,

Hopewell PC. Treatment of tuberculosis in patients with advanced human

immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1991;324:289 94.

11. Ackah AN, Coulibaly D, Digbcu H, et al. Response to treatment, mor

tality, and CD4 lymphocyte counts in HIV-infected persons with tubercu

losis in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Lancet 1995;345:607 10

12. Pitchcnik AE. Tuberculosis control and the AIDS epidemic in devel

oping countries. Ann Intern Med 1990;! 13:89-91.

808

September 18, 1997

,

I

13. O'Brien RJ. Pcrriens JH. Preventive therapy for tuberculosis in HIV

infection the promise and the reality. AIDS 1995;9:665-73.

14. Goodgamc RW. AIDS in Uganda — clinical ami social features

N Engl J Med 1990;323:383 9.

15. Moreno S, Baraia Etxaburu J. Bouza E. et al Risk for developing tu

berculosis among anergic patients infected with HIV Ann Intern Med

1993.1 19.194 8

16. Graham NMH, Galai N, Nelson KE, et al. Effect of isoniazid chemo

prophylaxis on HIX' related mycobacterial disease. Arch Intent Med 1996

156:889 94.

17. Rcichman LB. Felton CP. Edsall JR Drug dependence, a possiblc

nevv risk factor for tuberculosis disease. .Arch Intern Med 1979;! 39:337

9.

18. Fcrcbce SH. (Controlled chemoprophylaxis trials in tuberculosis: a gen

cral review. Adv Tubcrc Res 1970;17:28-i06.

19. Hong Kong Chest Serv icc/Tubcrculosis Research Centre, Madras/

British Medical Research Council. A double-blind placebo-controlled clin

ical trial of three antitubcrculosis chemoprophylaxis regimens in patients

with silicosis m Hong Kong. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:36-41.

20. International Union Against Tuberculosis Committee on Prophylaxis.

Efticacv of various durations of isoniazid preventive therapy tor tuberculo

sis: five wars of'follow-up in the IUAT trial. Bull World Health Organ

1982.60:555 64.

21. (Comstock GW. Baum ( . Snider DE Jr. Isoniazid prophylaxis among

Alaskan Eskimos: a final report of the Bethel isoniazid studies. Am Rev

Respir Dis 1979;l 19 827 50.

22. I bc use of preventive therapy tor tuberculous infection in the United

States. MMWR 1990.39. RR Si:9 12

23. (Coopman SA. Johnson RA. Platt R. Stern RS. Cutaneous disease and

drug reactions m HIX’ infection. N Engl I Med 1993;328:1670-4.

24. Pozniak AL. MacLeod GA. Mahan M. Legg XX', Weinberg J. ’Hie in

fluence of HIX’ status on single and multiple drug reactions to antituber

culous thcrapv m Africa AIDS 1992:6:809 14.

25. Karnofsky DH. Burchcnal JH. I he clinical evaluation of chemothera

peutic agents in cancel. In: MacLeod (CM, cd. Evaluation of chemothera

peutic agents New York: Columbia University Press. 1949:191-205.

26. Bass JR Jr. l-arer I.S, Hopewell PC, Jacobs RE, Snider DE Jr. Diagnos

tic standards and classification of tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;

142:725 35 | Erratum. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:l470. |

27. AIDS ( linical I rials Group. Table for grading severity of adult adverse

experiences. XX'ashington, D.C.: Division ot AIDS, National institute of Al

lergy and Infectious Diseases, 1993.

28. International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Technical

guide tor sputum examination for tuberculosis by direct.microscopy. Bull

hit Union Against Tuberc Lung Dis 1986;61:1 16.

29. Lan KKG. DcMets DL. Discrete sequential boundaries tor clinical tri

als. Biometrika I983;7O:659 6.3.

30. Pape JW, Jean SS, Ho JL, Hafner A, Johnson XX'D Jr. Ertect of isoniazid

prophvlaxts on incidence of active tuberculosis and progression of HIV in

fection. Lancet 1993;342:268 72.

31. De Cock KM, Grant A, Porter JDH. Preventive therapy tor tubercu

losis m HIX’ infected persons: international recommendations, research,

and practice Lancet 1995;345:833-6.

32. Iialscv N, Cobcrly J, Atkinson J, et al. Twice weekly INH for I B pro

phviaxis. In. Abstracts of the 10th International Conference on AlDS/ln

icrnaiional Conference on STD, Yokohama, Japan, August 7-12, 1994:

167. abstract.

33. XX'adhawan D, Hira S, Mwansa N, Perine P. Preventive tuberculosis

chemotherapy with isoniazid among persons infected with human immu

nodeficiency virus. In: Abstracts of the Seventh International Conference

on AIDS. Florence, Italy, June 6-21, 1991. Vol. 2. Rome: Istituto Superiorc di Sanita, 1991:247 abstract.

34. l.ccoeur HF, rruffot-Pcrnot C, Grossct JH. Experimental short-course

preventive therapy of tuberculosis with rifampin and pvrazinamide. Am Rev

Respir Dis 1989;! 40:1189-93.

35. Peloquin CA, MacPhee AA, Berning SE. Malabsorption of antimycobactcrial medications. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1122-3. :

36. Berning SE, Hunt GA, Iseman MD, Peloquin CA. Malabsorption of

antitubcrculosis medications bv a patient with AIDS. N Engl J Med 1992;

327:1817-8.

37. Patel KB, Belmonte R, Crowe HM. Drag malabsorption and resistant

tuberculosis in HIX' infected patients. N Engl J Med 1995;332:336-7.

38. Comstock GXX', Edw ards PQ. The competing risks of tuberculosis and

hepatitis for adult tuberculin reactors. Am Rev Respir Dis 1975;! 11:573-7.

EDITORIALS

Editorials

The Ethics of Clinical Research

in the Third World

A N essential ethical condition for a randomized

Ik clinical trial comparing two treatments for a dis

ease is that there be no good reason for thinking one

is better than the other.1-2 Usually, investigators hope

and even expect that the new treatment will be better,

but there should not be solid evidence one way or the

other. If there is, not only would the trial be scientifi

cally redundant, but the investigators would be guilty

of knowingly giving inferior treatment to some partic

ipants in the trial. The necessity for investigators to be

in this state of equipoise2 applies to placebo-controlled

trials, as well. Only when there is no known effective

treatment is it ethical to compare a potential new

treatment with a placebo. When effective treatment

exists, a placebo may not be used. Instead, subjects in

the control group of the study must receive the best

known treatment. Investigators are responsible for all

subjects enrolled in a trial, not just some of them, and

the goals of the research are always secondary to the

well-being of the participants. Those requirements arcmade clear in the Declaration of Helsinki of the World

Health Organization (WHO), which is widely regard

ed as providing the fimdamcntal guiding priiicipfes of

research involving human subjects.3 It states, “In re

search on man |.ffr], the interest of science and so

ciety should never take precedence over consider

ations related to the w ellbeing of the subject,” and “In

any medical study, every patient — including those of

a control group, if any — should be assured of the best

proven diagnostic and therapeutic method.”

One reason ethical codes are unequivocal about in

vestigators’ primary obligation to care for the human

subjects of their research is the strong temptation to

subordinate the subjects’ welfare to the objectives of

the study. That is particularly likely when the research

question is extremely important and the answer

would probably improve the care of future patients

substantially. In those circumstances, it is sometimes

argued explicitly that obtaining a rapid, unambiguous

answer to the research question is the primarv ethical

obligation. With the most altruistic of motives, then,

researchers may find themselves slipping across a line

that prohibits treating human subjects as means to an

end. When that line is crossed, there is very little left

to protect patients from a callous disregard of their

welfare lor the sake of research goals. Even informed

consent, important though it is, is not protection

enough, because of the asymmetry in knowledge and

authority between researchers and their subjects. And

approval by an institutional review board, though also

important, is highly variable in its responsiveness to

patients’ interests when they conflict with the inter

ests of researchers.

A textbook example of unethical research is the

Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis.4 In that study,

which was sponsored by the U.S. Public Health Service

and lasted from 1932 to 1972, 412 poor AfricanAmerican men with untreated syphilis were followed

and compared with 204 men free of the disease to de

termine the natural history of syphilis. Although there

was no very good treatment available at the time the

study began (heavy metals were the standard treat

ment), the research continued even after penicillin be

came widely available and was known to be highly ef

fective against syphilis. The study was not terminated

until it came to the attention of a reporter and the out

rage provoked by front-page stories in the Washington

! Star and New York limes embarrassed the Nixon

administration into calling a halt to it.5 The ethical

violations were multiple: Subjects did not provide

informed consent (indeed, they were deliberately de

ceived); they were denied the best known treatment;

and the study was continued even after highly effective

treatment became available. And what were the argu

ments in favor of the Tuskegee study? That these poor

African-American men probably would not have been

treated anyway, so the investigators were merely ob

serving what would have happened if there were no

study; and that the study was important (a “never-tobe-repeated opportunity,” said one physician after

penicillin became available).6 Ethical concern was even

stood on its head when it was suggested that not only

was the information valuable, bin it was especially so

for people like the subjects — an impoverished rural

population with a very high rate of untreated syphilis.

The only lament seemed to be that many of the sub

jects inadvertently received treatment bv other doctors.

Some of these issues arc raised by Lurie and Wolfe

elsewhere in this issue of the Journal. They discuss

the ethics of ongoing trials in the Third World of

regimens to prevent the vertical transmission of hu

man immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection." All

except one of the trials employ placebo-treated con

trol groups, despite the fact that zidovudine has al

ready been clearly shown to cut the rate of vertical

transmission greatly and is now recommended in the

United States for all HIV-infected pregnant women.

I he justifications arc reminiscent of those for the

Tuskegee study; Women in the Third World would

not receive antiretroviral treatment anyway, so the

investigators arc simply observing what would hap

pen to the subjects' infants if there were no study.

And a placebo-controlled study is the fastest, most

efficient way to obtain unambiguous information

that will be of greatest value in the Third World.

1 hus, in response to protests from Wolfe and others

to the secretary of Health and Human Services, the

directors of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

and the Centers for Disease Control anil Prevention

Volume 337

X umber 12

847

EDITORIALS

controlled, if at all possible. That rigidity may ex

plain the NIH’s pressure on Marc Lallemant to in

clude a placebo group in his study, as described by

Lurie and Wolfe.7 Sometimes journals are blamed

for the problem, because they are thought to de

mand strict conformity to the standard methods.

That is not true, at least not at this journal. We do

not want a scientifically neat study if it is ethically

flawed, but like Lurie and Wolfe we believe that in

many cases it is possible, with a little ingenuity, to

have both scientific and ethical rigor.

The retreat from ethical principles may also be ex

plained by some of the exigencies of doing clinical

research in an increasingly regulated and competitive

environment. Research in the Third World looks rel

atively attractive as it becomes better funded and

regulations at home become more restrictive. De

spite the existence of codes requiring that human

subjects receive at least the same protection abroad

as at home, they arc still honored partly in the

breach. The fact remains that many studies arc done

in the Third World that simply could not be done in

the countries sponsoring the work. Clinical trials

have become a big business, with many of the same

imperatives. To survive, it is necessary to get the

work done as quickly as possible, with a minimum

of obstacles. When these considerations prevail, it

seems as if we have not come very far from Tuskegee

after all. Those of us in the research community

need to redouble our commitment to the highest

ethical standards, no matter where the research is

conducted, and sponsoring agencies need to enforce

those standards, not undercut them.

Marcia Angell, M.D.

REFERENCES

1. Angell M. Patients' preferences in randomized clinical trials. N Engl J

Med 1984;310:1385-7.

2. Freedman B Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med

1987;317:141-5.

3. Declaration of Helsinki IV, 41st World Medical Assembly, Hong Kong,

September 1989. In: Annas GJ, Grodin MA, eds. The Nazi doctors and

the Nuremberg (’ode: human rights in human experimentation. New York:

Oxford L’niversity Press, 1992:339-42.

4. Twcntv vears after: the legacy of the Tuskegee syphilis study. Hastings

Cent Rep 1992;22(6):29-40.

5. Caplan AL. When evil intrudes. Hastings Cent Rep 1992;22(6):29-32.

6. The development of consent requirements in research ethics. In: Faden

RR, Beauchamp TL. A history and theory of informed consent. New York:

Oxford L’niversity Press, 1986:151 99.

7. Lurie P, Wolfe SM. Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal

transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing coun

tries. N Engl J Med 1997;337:853-6.

8. The conduct of clinical trials of'maternal-infant transmission of HIV

supported by the United States Department of Health and Human Sen ices

in developing countries. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and

Human Sen ices, July 1997.

9. Whalen CC, Johnson JL, Okwera A, et al. A trial of three regimens to

prevent tuberculosis in L’gandan adults infected with the human immuno

deficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1997;337:801 8

10. I he use of preventive therapy for tuberculous infection in the Unites!

Stares: recommendations of the Advisors Committee for Elimination of'

Tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wklv Rep 1990;39(RR 8):9 12.

11. Bass JB Jr, barer LS, Hopexsell PC, et al. Treatment of tuberculosis ami

tuberculosis infection in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1994;149:1359-74.

12. De Cock KM, Grant A, Porter JD. Preventive therapy for tuberculosis

in HIV-infected persons: international recommendations, research, and

practice. Lancet 1995;345:833-6.

13. Msamanga GI, Fasvzi WAV. The double burden of HIV infection and

tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med 1997;337:849-51.

14. Angell M. Ethical imperialism? Ethics in international collaborative

clinical research N Engl J Med 1988;319:1081-3.

15. Protection of human subjects, 45 CFR § 46 (1996).

16. International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving hu

man subjects. Geneva: Council for International Organizations of Medical

Sciences, 1993.

17. Angell M. The Nazi hvpothermia experiments and unethical research

today. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1462-4

©1997, Massachusetts Medical Society.

The Double Burden of HIV

Infection and Tuberculosis

in Sub-Saharan Africa

I

r I ^HE World Health Organization (WHO) estiJL mated that by June 1996 14 million people were

living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in

fection in sub-Saharan Africa. Although it contains

only 10 percent of the world’s population, subSaharan Africa is home to about 65 percent of all the

world’s HIV-infected people. In several urban cen

ters, more than 10 percent of the asymptomatic

adults and about 15 to 30 percent of the women at

tending prenatal-care clinics are infected. A 1994 pa

per reported that in rural Uganda more than 80 per

cent of the deaths among men and women 25 to 44

years of age were attributable to HIV infection.1 The

reported risk of perinatal transmission of HIV is gen

erally higher in African studies (30 to 45 percent)

than in European and American studies (7 to 30

percent). Although the median length of time from

seroconversion to the appearance of the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is approximate

ly 10 years in the United States, it is only 4.4 years

among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya.2

The death of one or both parents from HIV in

fection has left many African children without so

cial, emotional, or economic support. HIV infection

has also put additional strains on the already over

stretched health care systems. The average annual per

capita expenditure on health is $11 for the region,

and in several countries it is less than $4. Many areas

lack essential drugs and medical supplies, including

antibiotics, antiseptics, and gloves. With the increas

ing privatization of the health care sector, many

health services (excluding prenatal care and other pre

vention programs) arc available — but at a price. Al

though mechanisms have been developed to waive

the fees for those who cannot afford them, these may

be difficult to implement when the majority of pa

tients arc poor. In fact, over 50 percent of the adult

patients admitted to the hospital in Africa arc infected

Volume 337

Number 12

849

r

t*F

The Xc« England Journal of Medicine

with HIX', and many of them arc unable to pay for

care. Given that HIV infection is most prevalent

among the economically productive age groups, pa

tients’ families suftcr tremendously because of the fre

quent illnesses and eventual death of those infected.

A secondary epidemic of tuberculosis is accompany

ing the rise in the number of HIV-infected persons.

WHO estimates that worldwide nearly 5 million peo

ple are infected with both HIV and tuberculosis, and

three quarters of them live in Africa.' Prevention oP

tuberculosis among those with HIV infection is a log

ical public health goal, given that such patients arc at

high risk for tuberculosis, which in turn is associated

with an increased likelihood of death. Long before the

advent of AIDS, preventive therapy with isoniazid was

show n to reduce the occurrence of tuberculosis signif

icantly among contacts of patients with active disease

and among those with conversion of a tuberculin skin

test to positive.4 Because of concern about the in

creased adverse effects of antitubcrculosis therapy in

HIX'-positivc patients, a number of trials have exam

ined the safety and efficacy of chemoprophylaxis in

this population. Placebo-controlled studies were car

ried out in Haiti, Zambia, and Kenya with varying de

signs and results. In the Haitian study, a 12-month

course of isoniazid significantly reduced the incidence

of tuberculosis among HIV-positive subjects with

positive tuberculin skin tests. However, about 40 per

cent of the new cases were based on presumptive di

agnoses of tuberculosis? In the Zambian study, a sixmonth course of isoniazid reduced the incidence of

tuberculosis among patients with positive tuberculin

skin tests? But in the study from Kenya there was no

effect of six months of therapy with isoniazid among

HIV-positive subjects, although the number who had

positive tuberculin skin tests was too small to permit

the effect of therapy to be examined in this subgroup/

In this issue of the Journal, Whalen et al. report,

that a six-month course of isoniazid among HIVinfected Ugandans with positive tuberculin skin tests

reduced the risk of tuberculosis by about 70 percent

after a mean follow-up period of 15 months.8 Isonia

zid therapv may have reduced the risk of tuberculosis

among subjects with anergy as well. This study also

adds to our knowledge of the role of preventive ther

apies that include drugs other than isoniazid, such as

rifampin and pyrazinamide. For the subjects who re

ceived a three-month course of isoniazid and rifam

pin, there was about a 60 percent reduction in the

risk of tuberculosis as compared with those given pla

cebo. The reduction in the risk of tuberculosis for

those given isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide was

49 percent. Alternative regimens arc needed for those

infected with isoniazid-resistant strains, and the short

er courses arc likely to improve compliance. However,

thev arc also associated w ith a higher risk of adverse

events and arc most costly. Although none of the

treatments in this study reduced mortality significant-

850

•

September IS, 1997

Iv, the sample size and duration of follow-up were in

adequate for this question to be examined.

The results of the study from Uganda support the

administration of isoniazid as preventive therapy for

persons in sub-Saharan Africa who arc infected with

HIV and have positive tuberculin skin tests. Before

any such program can lx* implemented on a communitvwidc level, research on the operational and pro

grammatic questions is urgently needed. Is preventive

therapy feasible in sub-Saharan Africa? Is it cost effec

tive, as compared with other uses of scarce health care

dollars? The introduction of a program of preventive

therapy requires human resources, laboratory sup

plies, drugs, and transport facilities in order to carry

out voluntary counseling and testing for HIV infec

tion, to identify and exclude all those with active tu

berculosis, to perform tuberculin skin testing, and to

provide follow-up care. The exclusion of those with

active tuberculosis is important, since treatment with

isoniazid alone is insufficient and would lead to the

development of drug-resistant organisms. It is also

important to exclude people with liver problems at

base line and to terminate therapy among those in

whom hepatotoxicity develops during follow-up. In

one report, unsupcrv ised preventive therapy in Ugan

da was associated with poor compliance.9 On the oth

er hand, directly observed therapy for tuberculosis

given by nonmedical staff w as reported to be success

ful in a South African community,1" and a similar sys

tem could be instituted for preventive therapy.

A number of’ scientific issues still need to be ad

dressed. These include the question of how long the

protection afforded by preventive therapy lasts. The

protection afforded by 6 to 12 months of isoniazid

therapy is probably lifelong in the parts of the world

w here the risk of transmission of tuberculosis is low.

In sub-Saharan Africa, however, the duration of ef

ficacy may be much shorter because the risk of in

fection or reinfection is so high. The efficacy and

economics of providing long-term preventive thera

py or lifelong therapy and the risk of accelerating

drug resistance need to be examined.11 Given our

current state of knowledge, however, future studies

should not include a placebo group, since preventive

therapy should be considered the standard of care.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where there is little access

to antiretroviral drugs, preventive therapy for tuber

culosis may be the single most affordable interven

tion for the prolongation of a healthy life in HIVinfected persons. By preventing tuberculosis, these

regimens will also help reduce the transmission of

tuberculosis in African communities. Although we

agree with WHO that interrupting the transmission

of tuberculosis by curative treatment of infectious

cases should continue to be the priority for tuber

culosis programs,12 efforts need to be made to apply

these important findings about preventive therapy to

the community and the region where the study was

EDITORIALS

carried out. It is clear that African programs of tu

may lead to delusions. Negative symptoms involve the

berculosis and AIDS control will be unable to un , loss of normal functioning — the loss of will, range of

dertake this additional responsibility alone, since they

affect, pleasure, and fluency and content of speech,

rely largely on donor

<'

support. Extension of these proThe intensity of these symptoms and the residual dis

grams will be possible only through the cooperation

ability they cause may prevent people with schizophre

of many governments, pharmaceutical companies,

nia from beginning a career, completing an education,

and international agencies.

or enjoying a life that may once have been filled with

great promise. Rates of employment among people

Gernard I. Msamanga, M.D., Sc.D. i with schizophrenia rarely exceed 20 percent.

Muhimbili Medical Center

Schizophrenia is a chronic illness; less than 20 per

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

cent of patients recover from a single episode of psy

chosis and return to the lives they knew before. More

Wafaie W. Fawzi, M.B., B.S., Dr.P.H.

frequently, patients have repeated episodes, with dec

Harvard School of Public Health

rements in base-line functioning accompanying each

Boston, MA 02115

one; a few never recover from the first episode and

REFERENCES

continue to have pervasive psychotic symptoms.

For 35 years, the pharmacologic approach to schizo

1. Mulder DW, Nunn AJ, Kamali A, Nakiyingi J, Wagner HU, KcngcyaKayondo JF. Two-year HIV-1-associated mortality in a Ugandan rural pop

phrenia involved antipsychotic medication based on

ulation. Lancet 1994;343:1021-3.

D2 dopamine-reccptor antagonism. The dopamine

2. Anzala OA, Nagclkcrke NJ, Bwayo JI, et al. Rapid progression to disease

in African sex workers with human immunodefieienev virus tvpe 1 infec

hypothesis of schizophrenia was proposed in 1963,'

tion. J Infect Dis 1995;171:686-9. (Erratum, J Infect Dis 1996;!73:1529 ]

10 years after the first antipsychotic medication was

\ 3./ The HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis epidemics: implications lor TB control.

introduced. This hypothesis was based on the ob

Geneva: World Health Organization, 1994. (WHO/TB/CARG(4)/94.4.)

4. O'Brien RJ. Preventive therapy for tuberculosis. In: Porter JDH,

servation that all antipsychotic drugs had a strong af

McAdam KPWJ, cds. Tuberculosis: back to the future. Chichester, Eng

finity for a particular dopamine receptor (D2) and

land: Wile)’, 1994:151, 66.

that dopamine agonists, such as methylphenidate and

5. Pape JW, Jean SS, Ho JL, Hafner A, Johnson WD Jr. Eflcct of isoniazid

prophylaxis on incidence of active tuberculosis and progression of HIV in

dextroamphetamine, could produce a psychotic con

fection. Lancet 1993;342:268-72.

dition. Standard antipsychotic drugs differed only in

6. Wadhawan D, Hira'S, Mwansa N, Perine P. Preventive tuberculosis che

motherapy with isoniazid among persons infected with HIV-1. Presented

their side effects, not in their mechanisms of action.

at the Eighth International Conference on AIDS/Third STD World Con

Consistent

side effects were those associated with D2

gress. Amsterdam, July 19-24, 1992. abstract.

antagonism, most likely in the nigrostriatal dopamine

7. Hawken MP, Meme HK, Elliott EC. et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy

for tuberculosis in HIX'-1 -infected adults: results of a randomized con

tracts, which led to extrapyramidal symptoms of stiff

trolled trial. AIDS 1997:11 875-82.

ness,

tremor,

pseudoparkinsonism,

and akathisia. Sub8. Whalen CC, Johnson JL, Okwera A, eti ai.

al. A trial

nidi of three

uircc regimens

rcginiciis to

io

’

* 1

I

• j

rv

in Ugandan

adults infected

immuno

i JCCtlVCly, tnCSC Side eirCCtS were unpleasant, leading

iprevent tuberculosis

.........................

,......................

---: with the human

...... -.................

deficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1997;337:801-8.

j to cycles of noncompliance and relapse. Estimates of

9. Aisu f, Raviglione MC. t ar. Praag E, et al. Preventive chemotherapv for

40 percent rates of noncompli;

. iance among patients

Hl\ -associates! tulx'rculosis in Uganda: an operational assessment at a vol

untary counselling and testing centre. AIDS 1995;9:267-73.

treated with antipsychotic agents were not unusual;

10. Wilkinson D, Davies GR, Connolly C. Directly observed therapv for

when noncompliance was combined with the thera

tuberculosis in rural South Africa, 1991 through 1994. .Am J Public Health

peutic limitations of the drugs, rates of relapse were

1996;86:1094-7.

11. De Cock KM, Grant A, Porter JD. Preventive therapy for tuberculosis

! quite high.

in HIV-infected persons: international recommendations, research, and

Clozapine, the first novel antipsychotic drug to

practice. Lancet 1995;345:833-6.

appear, was introduced in the United States in 1989.

12. Tuberculosis preventive therapv in HIV-infected individuals. Wklv Ep

idemiol Rec 1993;68:361-4.

A conventional antipsychotic drug, such as haloper

©1997, Massachusetts Medical Society.

idol, produced its antipsychotic effects after binding

to 80 percent of dopamine D2 receptors; clozapine

produced an antipsychotic effect after binding to

less than 20 percent of D2 receptors. Hypotheses

Pharmacologic Advances in the

about clozapines principal mechanism of action have

Treatment of Schizophrenia

been hotly debated, but without resolution. Pro

posed mechanisms of action have focused, separateh

\ LTHOUGH medications have dramatically imand in combination, on other dopamine receptors

XJL proved the li\es of many people with schizophre

(DI and D4) and on clozapine’s effects on the sero