COMMUNITY HEALTH FELLOWSHIP SCHEME - ANNUL COMMUNITY HEALTH FELLOWS WORKSHOP 2005. MARCH 6-8 AT NAVASPOORTJHI KENDRA, BANGALORE

Item

- Title

- COMMUNITY HEALTH FELLOWSHIP SCHEME - ANNUL COMMUNITY HEALTH FELLOWS WORKSHOP 2005. MARCH 6-8 AT NAVASPOORTJHI KENDRA, BANGALORE

- extracted text

-

RF_COM_H_90_SUDHA

c2o

v\—

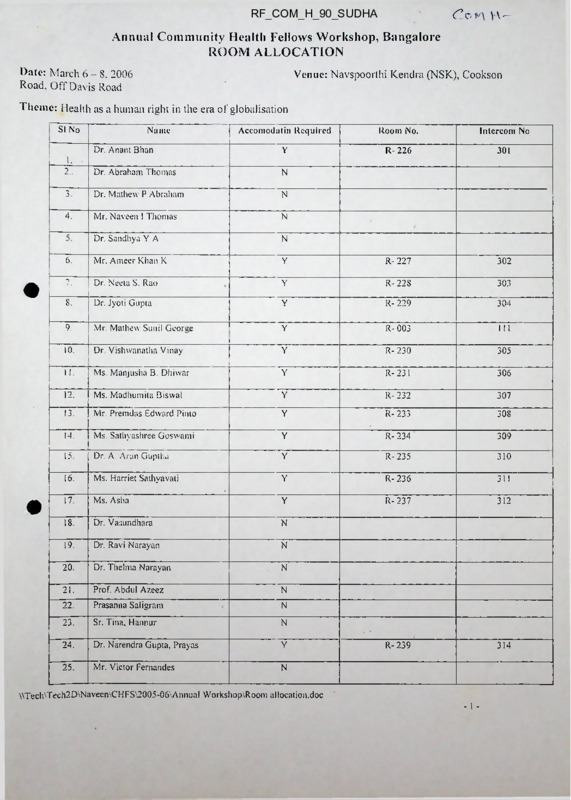

Annual Community Health Fellows Workshop, Bangalore

ROOM ALLOCATION

Venue: Navspoorthi Kendra (NSK), Cookson

Date: March 6 - 8. 2006

Road. Off Davis Road

Theme: Health as a human right in the era of globalisation

SI No

•

•

Name

Acconiodatin Required

Room No.

Intercom No

R- 226

301

Dr. Anant Bhan

Y

1.

2..

Dr. Abraham Thomas

N

3

Dr. Mathew P Abraham

N

4-

Mr. Naveen I Thomas

N

Dr. Sandhya Y A

N

6-

Mr. Ameer Khan K

Y

R- 227

302

7.

Dr. Neeta S. Rao

Y

R-228

303

8.

Dr. Jyoti Gupta

Y

R- 229

304

9.

Mr. Mathew Sunil Georoe

Y

R- 003

111

10.

Dr Vishwanatha Vinay

Y

R-230

305

11.

Ms. Manjusha B. Dhiwar

Y

R-231

306

12.

Ms. Madhumita Biswal

Y

R- 232

307

13.

Mr. Premdas Edward Pinto

Y

R-233

308

14.

Ms. Sathyashree Gcswami

Y

R- 234

309

15.

Dr. A. Arun Guptha

Y

R- 235

310

16.

Ms. Harriet Sathyavati

Y

R- 236

311

17.

Ms. Asha

Y

R-237

312

18.

Dr. Vasundhara

N

19.

Dr. Ravi Narayan

N

20.

Dr. Thelma Narayan

21.

Prof. Abdul Azeez

N

22.

Prasanna Saligram

N

23.

Sr. Tina, Hannur

N

24.

Dr. Narendra Gtipta, Prayas

Y

R- 239

314

25.

Mr. Victor Fernandes

N

.

N

\\Tech\Tech2D\Naveen\CHFS\2005-06\Annual Workshop\Room alloeation.doc

-1 -

COMMUNITY HEALT H CELL

Annual Community Health I'cllow Workshop, Bangalore

Date: 6lh to 8lh March - 2006

Venue: Nava Spoorthi Kendra, Bangalore

REQUISITION FORM FOR TRAVEL SUPPORT

NAME

ADDRESS

DETAILS OF TRAVEL EXPENSES

Mode

Date

Front

To

Amount

GRAND TOTAL (in Figures)

Rupees (in words):

Approved by:

Please attach supporting bills lor the claims mentioned above

Signature oC person

receiving the amount

C-O'M "Y 1 -

AGENDA ITEM NO. 5

Suggesting a global 'Right to Health campaign' by PHM

which could be launched at PHA-2

We thus find ourselves at a crossroads: health care can be considered a commodity to be sold,

or it can be considered a basic social right. It cannot comfortably be considered both of these

at the same time. This, I believe is the great drama of medicine at the start of this century.

And this is the choice before all people of faith and good will in these dangerous times.

- Paul Farmer

The context

The large scale weakening of public health systems, unchecked privatisation in various forms

and erosion of universal healthcare access systems are phenomena seen across the globe in

the current phase of liberalisation-hegemonic globalisation. The global health sector

discourse seems to be dominated by vertical, selective, urban and technocratic approaches, as

well as by 'public-private partnerships' of different kinds —at global, national and local

levels— as the preferred mode of implementation of services. Today there is an urgent need

for a process that will replace this dominant discourse by a 'Right to health and health care'

approach needed to achieve truly 'universal and comprehensive health care systems both in

developing and developed countries. To counter and reverse the current trend that

commoditizes health, there is thus a need to reach a strong global consensus on 'Health care

as a right', as well as a need to begin using the existing international and national provisions

that support this Right in an effective manner; we need to fight for strengthening public

health in an accountable manner. It is in this context that the possibility of launching a global

initiative to strengthen the 'Right to Health', with a focus on defending and operationalising

the 'Right to Health Care', is presented here below.

The justification

The majority of countries around the world (over 150) are party to the International Covenant

on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The General Comment 14 of CESCR, adopted in

the year 2000, elaborates on and goes into the details of the Right to Health and clearly

defines its broad characteristics, methods of operationalisation and current violations, and

suggests the means to monitor the implementation of this Right. We are nearing five years of

the launching of General Comment 14 —the most comprehensive internationally adopted

instrument that rules the understanding we ought to have of the Right to Health. However,

there is still a need to launch a global process that will raise the demands for the provisions of

GC 14 to be seriously implemented in all signatory countries. This stresses the paramount

importance of operationalising the 'Right to Health', and calls for reviewing, revisioning

and remissioning all global and national health sector initiatives in the light of the

overarching framework of health rights (such as, for example, MDGs).

A suggested content focus of the campaign

The 'Right to Health' framework provides us with an internationally agreed-upon consensus

structure based on which a strong argument should be constructed. However, within this

broad framework, we suggest that the campaign should, in its first phase, focus on the 'Right

to health care'. This is a burning issue in the context of current weak and weakening health

systems and it is amenable to actions from within the health sector. This, of course,

involves arriving at a broadened vision of health care, one that includes not only the entire

range of preventive, promotive and curative health services, but also services like nutritional

supplementation, ensuring drinking water quality, health related education and information —

all activities carried out with the primary and express purpose of improving health

comprehensively. It need not be emphasised that specific important aspects of this Right,

such as Women's right to health care, Children's health care rights, Mental health rights,

Health care rights of HIV-AIDS affected persons, Worker's health rights, The right to

essential drugs and other will be woven together, bringing diverse strands of the health

movement into a broad coalition that will work to strengthen public health systems and a

universal access to health care.

At the same time, some other key social determinants of health adversely affected by policy

changes that are having negative impacts on the health of the poor —and where PHM

members are in a position to document and push for policy changes-can and will be identified

at the country level and taken up as part of the campaign. This focus could be broadened in

the subsequent phase of the campaign.

Possible organisational collaboration (networking)

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Right to Health is entrusted with the

responsibility of reviewing the status of implementation of this Right the world over. There

has been some communication with the present Rapporteur, Prof. Paul Hunt, who has shown

interest in the idea of such a global process. WHO has a division dealing with Ethics and

Human Rights, and there are persons in other divisions such as the Poverty and Health

Policies Division who also seem to be willing to lend support to such a process. Given our

aim to shift the focus of WHO towards a Rights-oriented approach, and given its global

potential to influence national health systems, we see WHO as an important collaborator in

such a process. Most countries have National human rights commissions or similar official

bodies, which we hope to involved to varying extents in monitoring the Right to Health.

Human rights groups have the potential to take interest in this issue, especially in issues like

access to care for HIV-AIDS affected persons. Of course, present strategic allies of PHM

will need to take a lead with us in the different countries helping us involve a broader range

of civil society organisations in this campaign (including women's organisations and

networks, coalitions of HIV-AIDS affected persons, trade unions of health sector personnel,

people's movements).

Suggested process to advance this discussion

To move towards a concrete campaign start-up process, we suggest a possible

sequence of activities as per below, which will be modified and refined based

on suggestions from the PHM global steering group and PHM activists across the

world.

a. During the upcoming PHM steering group meeting at Bangalore on 11-12 April,

a discussion is planned on the various aspects and feasibility of such a campaign. This will

provide the basis for concretising the next steps.

b. Sometime during the World Health Assembly in May, we plan a meeting co-organised by

the Poverty and Health Policies Division of WHO, PHM and other strategic allies, on 'Global

efforts for operationalising the Right to Health1. Paul Hunt will be invited to this meeting. In

this meeting, we will brainstorm on the possibilities of a Global Right to Health initiative,

and the possible roles of WHO, the Special Rapporteur on Health and of PHM and

other partners. At this point we foresee working out an outline of a larger event during PHA2 as suggested below. (Based on preliminary communications, it appears that both persons

from the Poverty and Health Policies Division of WHO and Paul Hunt are interested in such a

meeting).

Also during WHA, a PHM group will meet Dr. Lee and, while inviting him for PHA-2, we

will discuss this idea with him, since his endorsement is crucial for WHO co-sponsoring and

supportinng Regional consultations on 'Operationalising the Right to Health' in various WHO

regions and sponsoring the follow-up workshop on this during PHA-2 (as discussed below).

c. During PHA-2, we are thinking of having a well planned large workshop on 'Global action

for the Right to Health', involving WHO and PHM delegates from various regions and all

other partners who will have joined us by then.

Dr. Lee and Paul Hunt will be invited to co-chair this workshop, and there we will work out a

concrete outline of a 'Global Right to Health Campaign' focussing on ensuring widespread

social support, official recognition, delineation and operationalisation of the Right to Health

Care and Right to key health determinants. By then we will try to crystallise an agreement

among WHO, Paul Hunt and PHM to organise Regional events on the 'Right to Health' in

various regions of the world, which will be fed into by PHM country level reports or papers

and will be based on the stipulations in CESCR General Comment 14.

d. If such an agreement emerges, we plan to collaborate with WHO to organise a series of

Regional assemblies on 'Right to Health - Universal Access to Health Care', say from end

2005 to end 2006. Each regional assembly will be preceded by country level workshops,

wherever possible, involving national human rights bodies, to analyse the state of the 'Right

to health' in their country (based on GC 14 and national constitutional and legal obligations)

and to concretely delineate gaps in health rights, while raising the need for a mechanism to

address violations. The Regional assemblies will be attended by senior country health

officials, national human rights bodies and PHM delegations, and will discuss the

operationalisation of health rights and developing redressal and monitoring mechanisms in

each country.

e. This series of regional assemblies may culminate in some kind of resolution being adopted

al WHA-2007, calling for time-bound complete implementation of the Right to Health, and

putting in place mechanisms for monitoring and redressal of this right in all countries of the

world, while appealing for an end to all forms of violations of this Right based on a content

clearly defined by the CESCR general Comment 14. PHM partner organisations will use

this as a concrete opportunity to draw in many more organisations into their network, to

dialogue with their country governments, to engage with national human rights bodies and to

build a consensus on the need to end violations of health rights in various forms and to

reverse policies responsible for such violations.

The process will be used to try to shift the discourse from the preoccupation with globally

directed vertical programmes and privatisation-oriented measures, by talking about

widespread denial and violation of the Right to Health, by demanding a global consensus on

implementing this Right, and asking that all programmes and measures must now be critically

evaluated from a Health Rights perspective.

What can realistically be achieved in such a process?

There is no illusion that systematically raising the issue of'Right to Health' itself will lead to

actual complete implementation of this Right in countries across the globe. The universal

provision of even basic health services involves major budgetary, operational and systemic

changes; providing these in a definite Rights-based framework also involves major political

and legal reorientations; and such major changes cannot be expected in the near future, given

the political economy of health care in most countries of the world today.

However, we can expect and work for certain more achievable objectives, which will take us

towards the larger goal. Some such 'achievables' to be expected from a campaign may be explicit recognition of the Right to health care at country level; formation of health rights

monitoring bodies, with PHM and civil society participation in some countries; clearer

delineation of health rights at both global and country levels; shifting the focus of WHO

towards health rights / universal access systems and strengthening a group within WHO

to continue working for the same; bringing Right to health care into the global agenda and

making it a reference point in the global health discourse; and strengthening PHM networks

in various countries around a common, broad rallying point.

PHM organisation - PHM campaign; an iterative process of building both

An obvious and valid response to this suggestion may be that the development of PHM is

highly uneven in different countries, and that in many countries the PHM groups are not in a

position to take up such an activity. While accepting this situation, we also need to reckon

with the fact that PHM country circles, which were formed during or after PHA based on a

shared concern and broad understanding about health and the health sector, need to move

beyond communication and discussion to develop common advocacy activities, if they

are to develop further and to draw in more groups. Moving forward from the basis created by

the 'Million signature campaign' and the 'Health -Now! No to war, no to WTO' campaigns,

there is a need to develop shared effective advocacy initiatives at the country level. These

could directly engage with decision makers and could try to bring about certain changes in

the ground level situation based on people's awareness and initiative. A 'Right to Health'

campaign can be such a process, which can bring together existing and new PHM groups

towards defined country' level advocacy objectives, and hence can strengthen and expand the

PHM organisation while developing a common activity. Of course, assessing the overall

practicability, and ascertaining the existence of a minimum critical mass of PHM in a

substantial number of countries which is necessary to develop the campaign, is something

that would need to be done collectively by the People's Health Movement to concretely

evaluate the feasibility of this approach. Our appeal is that such a process of discussion

should be initiated, and that some first steps be planned to explore the potential of such a

campaign. If there is a basic consensus on taking this forward, then given the approaching

People's Health Assembly, we should make use of this major event to work out, crystallise

and plan the further process.

We are concretely asking Steering Group members to react to this so that the Secretariat can

give the green light to this exciting process. We ask you to respond before April 5th.

- Abhay Shukla and Claudio Schuftan

8

Viewpoint

Pushing the international health research agenda towards

equity and effectiveness

Lancet 2004; 3&4:1630-31

David McCoy, David Sanders, Fran Baum, Thelma Narayan, David Legge

Peoples Health Movement,

c/o Community Health Cell,

Bangalore, India (D McCoy,

D Sanders. F Baum, T Narayan.

D Legge)

Correspondence to:

Dr David McCoy

davidmccoy@xyx.demon.co.uk

1630

Despite substantial sums of money being devoted to

health research, most of it does not benefit the health of

poor people living in developing countries—a matter of

concern to civil society networks, such as the People’s

Health Movement.' Health research should play a more

influential part in improving the health of poor people,

not only through the distribution of knowledge, but also

by answering questions, such as why health and health

care inequities continue to grow despite greatly

increased global wealth, enhanced knowledge, and more

effective technologies.

Previous Editorials in this journal, and other reports,

have already highlighted three important issues.2-* First,

that the 10:90 gap—whereby only 10% of worldwide

health research funds are allocated to the problems

responsible for 90% of the world's burden of disease,

mainly in poor countries—needs to be reversed. Second,

that greater emphasis should be placed on research in

the social, economic, and political determinants of ill

health, relative to clinical and biological research. Third,

that the barriers to the transfer of knowledge from

research into policy and practice need to be overcome.

The 10.90 gap largely represents a funding gap shaped

by commercial interests, and inadequate funds being

provided through the public budgets of poor countries,

development assistance grants, charitable foundations,

and non-government organisations who have an interest

and a mandate to invest in public or noncommercial

research activities that are orientated towards addressing

the health needs of poor people.

Part of the solution to addressing this overall deficit in

funding includes continuing with current efforts to

increase development assistance, hasten the cancellation

of unfair debt and reform unjust trade structures. But

we also need creative thinking and bold action around

new proposals, such as raising funds through an

international authority that is able to effectively tax

global corporate profits/ or applying levies against global

financial transactions (eg, the Tobin tax).6-7

With respect to research on the social, political, and

economic determinants of health, we draw attention to

three points. The first is the need for more research into

the effects of globalisation on poor health and growing

health inequities, and on the development of proposals

to reform the current global, political, and economic

institutional order. In addition to research on more

effective mechanisms for global resource redistribution,

research should focus on how health equity can be

protected from the market failures of economic

globalisation and the operation of transnational

commercial interests. Second, we want more research

applied to the question of why the cancellation of the

odious debt of many poor countries has not been

forthcoming, why many rich countries' development

assistance still falls short of the UN’s 0-7% gross

domestic product target,’* and why bilateral and

multilateral trade agreements continue to be

unfavourable and even punitive towards the poorest and

sickest people. Third, more research is needed into the

design and financing of systems and basic services and

into how these factors determine access to good quality

care and other health inputs (eg, water and adequate

nutrition). As health systems become increasingly

inequitable and fragmented, research on the drivers and

effects of the liberalisation, segmentation, and

commercialisation of health-care systems is essential.

These three points complement the call for more

research on why available and affordable technology and

knowledge are not used, for example, to prevent millions

of children from dying of diarrhoeal disease and acute

respiratory infections. Appropriate research would

indicate how the mainly social and political barriers to

application of existing technologies might be overcome.

This achievement could be aided by country' case studies

that combine an analysis of the political economy of

poverty and ill health together with the health systems

factors that help or obstruct access to effective health

care. Such research would bring together political and

social scientists, health economists, public health

professionals, ethicists, and civil society organisations.

To promote the transfer of knowledge from research

into policy and practice, several issues should be

examined. Presently, there is a research culture and

incentive system that encourages researchers to be more

concerned with publishing their results in academic

journals than with ensuring that their research leads to

improved policy and practice. Furthermore, policy

makers and programme implementers in developing

countries are either sceptical about the value of research,

or do not have the skills to appraise and use new

information? The scarcity of capacity in the public sector

has been further aggravated by the steady brain drain of

capable health professionals to richer countries or from

the public sector to the domestic private or non

government sectors (including the health research

sector)."’

These difficulties could be overcome by changing the

incentive system and allocating a greater share of health

research funding to academic and non-government

research institutions in poor countries that work closely

with policy makers, health managers, service providers,

and communities. This allocation of funding needs to

www.thelancet.com Vol 364 October 30,2004

Viewpoint

be complemented with more investment in developing

research capacity within the health systems of poor

countries.

Research geared towards practical health systems

development is also often qualitatively different from

research that is geared towards the imperatives of

academia and the medical industry. For example,

research on the efficacy of interventions in a controlled

environment is different from that on the practicability

of applying effective interventions in the real world.

More action research that involves service providers can

help to bridge the gap between research and

implementation, and ensure that research is embedded

within the day-to-day realities and constraints of under Figure: People's Health Assembly rally, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2000

resourced health-care systems. The use of participatory

research methods can also help poor communities will need to be exerted at all levels and by many different

shape health systems to meet their needs."1'

actors. The Peoples Health Movement is committed to

Research findings are also more successfully being increasingly influential.

implemented when researchers include mobilised Conflict of interest statement

citizen constituencies.1' Successful implementation is We declare dial we have no conflict of interest.

aided first by ensuring a vigorous community of civil Acknowledgments

society organisations with a mandate to keep a watch on D McCoy was funded by the Global Equity Gauge Alliance to attend a

health policy development and implementation; second, WHO consultation on health research that contributed to the final

production of this article.

by use of research funds to actively foster the capacity of

these organisations to change the commissioning and References

1

Peoples Health Movement, http://www.phmovemcnt.org (accessed

priority setting for research; and third, by including civil

Sept 21. 200-1).

society organisations in research production and 2 The Lancet. Kickstarting the revolution in health systems research.

Lancet 2004, 363: 1745.

’ encouraging partnerships that link them with academic

3

The Lancet. Mexico, 2004 research for global health and security

researchers.14

Lancet 2003; 362: 2033.

Finally, the imbalance in power between researchers 4 Global Forum for Heald) Research. 10/90 report on health research

2003-2004. Geneva. Switzerland: Global Forum for Health Research,

in rich and poor countries must be bridged. Many

2004. http://www.globalforumhealth.org/pagcs/index.asp (accessed

academic and non-government institutions in more

Sept 21, 2004).

developed countries benefit disproportionately from 5 Tax Justice Network. Declaration of the Tax Justice Network, 2003.

the meagre research funds that are focused on poor

http://www. taxjustice.net/e/e_declaration.pdf (accessed Sept 21.

2001).

health in developing countries. This imbalance is in a

6

Slecher H. Time for a Tobin Tax? Some practical and political

context where academic and research institutions in

arguments. Great Britain; Oxfam, May 1999. hltp://www.oxfam.

developing countries are struggling to gam their own

org.uk/what_we_do/issues/lTade/dowmloads/trade_tobintax.rlf

(accessed Sept 21, 2004).

funding and find it difficult to retain good staff.

7

Michalos AC. Good taxes: the case for taxing foreign currency

Practical ways of addressing the inequities within the

exchange and otiier financial transactions. New York: Duncan Press,

health research community might include mapping

1997.

out the distribution of research funds for health 8 Labonte R. Schrecker T. Sanders D. Mecus W, Fatal indifference- the

G8. Africa and global health Cape Town; University of Cape Town

problems between research institutions in rich and

Press, 2004.

poor countries, documenting the obstacles to the 9 Lomas, J. Using Linkage and exchange to move research into policy

at a Canadian Foundation. Health Affairs 2000; 19: 236-40.

development of research capacity in developing

countries and conducting in-depth case studies of the 10 Padaradi A. Chamberlain C, McCoy D, Ntuli A, Rowson M.

Loewenson R. Circulation or convection? Following die flow of

health-research funding policies and patterns of

health workers along the hierarchy of wealth. EQUINET- Network for

selected donor and international agencies.

Equity in Health in Southern Africa, 2003. http://www.gdnet.org/cf/

search/display.cfm?search-GDNDOCS&act-DOC&docnum-DOCl

Global conferences and summits on health research,

2980 (accessed Sept 22, 2004).

such as the two that are due in Mexico this November, by 11 Winter R, Munn-Giddings C. Action Research as an approach to

themselves are unlikely to substantially affect die

enquiry and development. In: A handbook for action research in

health and social care. London: Routiedge, 2001; 9-26.

challenges we present. The current pattern and use of

Martin K. de Koning K, eds. Participatory research in health- issues

health research shows the balance of prevailing global 12 and

experiences. Loudon: Zed Books, 1996; 1-18.

power, perspectives, and interests. Redressing 13 Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-based participatoryresearch for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

the

imbalance

will

require

consciousnessraising, mobilisation, and pressure at many different 14 Sanders D. Labonte R. Baum F, Chopra M. Making research matter;

a civil society perspective on health research. WHO Bulletin

points in the global health research system and in

(in press).

health-care systems more broadly. Pressure for change

www.thelancet.com Vol 364 October 30, 2004

1631

low Y\ —

Peoples’ Forum against ADB

Call for Action!

ADB and World Bank, Quit Asia! Quit India!

Mobilise against the Asian Development Bank Annual Governors’ Meeting

3-6 May 2006 Hyderabad

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is the third largest source of development finance in the AsiaPacific region, next to the World Bank Group and the Japanese Government. Every year, ADB moves huge

amounts of money across the Asia-Pacific region in a bid to foster rapid economic growth and market

capitalism. In 2004, the ADB’s total lending was US $ 5.3 billion which was used -to promote 64 projects

covering mostly road transport, communications, energy, law, economic management in the public policy

sectors Private sector assistance was to the tune of US S 807.2 million. The ADB’s largest borrowers in 2004

were China and India, each receiving USS 1.3 billion, about 24 per cent of the total lending. India is the fourth

largest shareholder in the ADB overall.

Despite its name, the management and operations of the ADB are greatly influenced by the USA and

the non-Asian capitalist powers. Although, Japan enjoys the most powerful status in the ADB, at par with the

USA, the non-Asians are powerful enough to manipulate the institution's directions to suit their own interests. In

promoting privatisation and private sector investments, the ADB routinely dole out lucrative contracts to favour

international firms and consultants.

Destructive and unaccountable

The ADB is an extremely secretive, non-transparent and unaccountable institution, despite its rhetoric

on good governance Its founding Charter of Principles provides the bank and its staff with immunity from local

and national laws. The ADB is thus not legally liable to communities, governments or individuals for any

wrongdoing, material harm or violation of rights.

Evaluation of ADB projects by independent researchers, citizen's groups, movements, NGOs and by its

own Operations Evaluation Department indicate that most ADB supported projects are poorly designed

implemented and managed. ADB does not facilitate public participation in development planning and access to

information while weakening local and national governance through undemocratic, non-transparent and nonconsultative methods of project implementation. ADB projects have continued to displace hundreds of

thousands of people across the region with little or no compensation, have resulted in negative environmental

and social impacts. The ADB, is therefore, charged with creating “development refugees" and “manufacturing

poverty" by the civil society organisations and movements.

The ADB, like the World Bank, has become the custodian of private investment and the promoter and

protector of corporate interests and profits. It follows the neo-liberal policy by imposing policy conditionalities the reform agenda and privatisation - on borrowing countries, and facilitates foreign companies to grab

contracts for research work, consultancy, project development, construction and management.

India Incorporated!

The ADB, in its Country Strategy and Programme (CSP) for India, 2003-2006, claims that the 10,h Plan

strategy is a sound one and is similar to its own poverty reduction strategy founded on pro-poor growth, social

development and good governance. India's strategy seems to fit well with the Banks! The CSP further says that

the most important role that India's development partners can play is in introducing international best practices

to strengthen fiscal and other structural reforms in the 10s' Plan' The Indian Government is playing second

fiddle by indicating that it looks to ADB, to play a leading catalytic role in supporting the next generation of

policy reforms. Since India can no longer access concessional loans from ADB, high risk loans at market rates

are taken for sectors focusing on high growth, reforms and private sector development.

During current CSP period, the ADB loans, starting from US $ 1.67 billion in 2003 is slated to increase

to US $ 2.05 billion in 2006, totaling US S 7.5 billion Projects financed by the ADB range from energy and

power sector reform and restructuring to road transport, water, irrigation, flood control, tourism, urban

development and administrative and fiscal reform. These projects are located across Jammu & Kashmir,

Uttaranchal, West Bengal and the North East, to Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Karnataka

and Kerala. The ADB’s array of policy conditions include, a) adopting legislations and regulations that favour

private sector involvement in key sectors, b) market-friendly restructuring, c) corporatisation and privatisation of

public enterprises and utilities, d) creating a flexible labour force, e) commercialization of agriculture and f) trade

and investment liberalization.

Mobilising against the Annual Governors’ Meeting

The ADB is holding its 39th Annual Governors' Meeting (AGM) from 3-6 May 2006 in Hyderabad.in the

State of Andhra Pradesh in southern India The Governors are the highest level of decision makers in the ADB.

Appointed by the ADB member countries, they are high-ranking national officials such as Finance Ministers or

Secretaries of National Treasuries. The current Chair of the AGM is Indian Finance Minister P Chidambaram.

Since 2000, peoples’ movements, communities affected by the ADB projects, progressive academics,

intellectuals, labour unions, activists and NGOs have used this opportunity to successfully mobilise themselves

at the AGM venues and protest against the institution and its development policies.

In 2000 and 2001, the ADB was shocked by the intensity of protests and strong messages sent to the

ADB by peoples' movements in Thailand and the US. The last AGM was in Turkey in 2005 where local

movements and organisations lent great support to the project affected and protest organisations that gathered

for the AGM.

In 2006, the eyes of the movements and struggles in Asia will be on Hyderabad and India. Peoples'

struggles against destructive development and oppressive economic and political structures are legendary in

India and particularly in Andhra Pradesh. Andhra Pradesh does not have any ADB supported projects, but it is

already a victim of the World Bank conditionalities - the power sector workers, the road transport workers, the

displaced tribals and the rural poor. In the recent past, the people of Hyderabad and Andhra Pradesh gave a

befitting reply to the Chandrababu Naidu Government that tried to foist a World Bank dictated reform agenda.

Thousands have marched in the streets of the city calling for a rejection of the World Bank's AP economic

restructuring loans. The Government that refused to listen to its people was comprehensively voted out of

power. The present Government, unfortunately, continues on the same path, eager to bring in foreign

investment at any cost.

The Hyderabad AGM offers us the opportunity to work with the groups in Andhra Pradesh; movements,

communities, organisations and activists in India and across Asia should come together and raise a collective

and unified voice against neo-liberalism. Whether through World Bank or ADB projects, the net impacts on

communities and societies are the same, especially on the poor, vulnerable and the marginalised, the workers,

dalits, tribals, women, peasants, the fishworkers or the urban poor, the hawkers and slum dwellers.

Come May 2006, let us give the ADB, the World Bank and all the other corporates who covet India's

resources and wealth, encroach upon the sovereignty of countries across the globe and in Asia, a unified

message:

Enough is Enough!

No to ADB, World Bank and the marauding corporates!

Governments listen to the voices of the peoples!

Peoples’ Forum against ADB comprises of the following groups from India and Asia:

•>

National Alliance of Peoples Movements, Narmada Bachao Andolan, Asia Pacific Movement on Debt and Development

(APMMD), Freedom from Debt Coalition, Philippines Rural Reconstruction Movement (PRRM), Karnataka Rajya Raitha

Sangha (KRRS), Equations. Nadi Ghati Morcha, River Basin Friends, Environment Support Group, ADB Quit Kerala

Campaign. INSAF. CORE. Urban Research Centre, Focus on the Global South. Citizens Concern for Dams & Development.

Delhi Forum, Samata, National Forum of Forest People & Forest Workers, mines minerals & People, Shaheen Centre,

Consumer Protection Forum, Water Initiatives, Consumer Protection Forum, Civil Society Initiative on IFIs (NE), Intercultural

Resources, NGO Task Force on ADB, Nagarika Hitharakshana Samithi, Balakedarara Hitharakshana Vedike, Anikethana

Trust, India Centre for Human Rights end Law (ICHRL), Palni Hills Conservation Council, National Fishworkers Forum,

Polavaram Project Andolana Samithi, Naga Peoples Movement for Human Rights, Movement Against Uranium Projects,

Centre for Environment Concerns, Aman Vedika, ITDS, Peoples Alliance Central East India, Japan Centre for a Sustainable

Environment and Society (JACSES), Center for Economic Justice, PAIRVI, Jharkhand Jangal Bachao Andolan, Bureau for

Human Rights. Adivasi Mukthi Sangathan. Peoples Movement in Subansiri Valley, Krishak Mukti Sangram Samithi.

Arunachal Citizens Rights. Indigenous/Tribal Peoples Development Center, Rural Volunteers Centre, Human Rights Tamil

Nadu Initiative.Parisava Badokidara Vedika, Human Rights Law Network, SAKSHI Human Rights Watch, Chatri, Jharkand

Labour Union. Dalit Women Forum. National Hawkers Federation, Net Work of Persons with Disabilities Organisation

(NPDO), Lok Raj Sangathan, Consumer Protection Council, Manthan Adhyayan Kendra, South Asia Network of Dams.

Rivers & People, Grassroot Options. FIMCOTN, Dwarf People’s Organisation. Chatn, New Trade Union Initiative. SEVA.

SABALA, National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights, Women's Collective, Bangla Praxis, Nagarik Udyog, Corporate

Accountability Desk of The Other Media, Chasma Lok Sath, National Centre for Advocacy Studies, Open Space. Peoples

Voice. Gangpur Adivasi Forum, Dalit Mukti Morcha, Plachimada Solidarity Committee, Pani Committee, Keselu Palu Group

(PNG). Uttaran, AOSED, Save Chara River Campaign, Gono Udyog Forum. Green Movement of Sri Lanka

Secretariat: 8-2-590/B, Road No. 1, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, INDIA,

Tel No. 91 40 55637974, Email: forumce: rdina'.iontaqmail.com

People’s Health Movement [ \ y

Coi^a \a-

CtUMEE

0» Hiv Aira Ai-ds

FREAKS5'

'•’

Ith

joc’ai.et y ?mi and political issue and, above all, a fundamental human

: .

■

ill

. ,!k:c are at the root of

\ ests working against

on I las to be opposed

•’.nd

priorities have

i • J w.x '.july cr-anged.

' political action. It is

ilso .

intervention

that requires ps pi. oriented health and medical

•• .

. ,

people inter-sectoral policies,

good governanc-?. people’s participation t,nd effective communication.They should

be rooted in internationally accepted human rights and humanitarian norms.

The special needs of women and children as infected persons, their dependents

and caregivers should be addressed.

In the current context, People's Charter on HIV and AIDS recognises the devastating

impact of war and conflict on health systems and how it amplifies the vulnerabilities

of people to HIV and AIDS.

People's Charter on HIV and AIDS draws upon perspectives of communities affected

and infected with HIV and AIDS and those vulnerable to the infection. It encourages

people to develop their own solutions and hold accountable local authorities, national

governments, international organisations and corporations to their promises and

responsibilities.

VISION

As stated in the People's Charter for Health: 'Equity, ecologically sustainable

development, social justice and peace are at the heart of our vision of a better

world - a world in which a healthy life for all is a reality; a world that respects,

appreciates and celebrates all life and diversity; a world that enables the flowering

of people's talents and abilities to enrich one another; a world in which people’s

voices guide the decisions that shape our lives'.

PERSPECTIVES

The AIDS pandemic is one of the greatest humanitarian crises of all times. I t has caused

death and misery, destroyed families and communities, derailed development and reversed

health gains achieved over decades in one stroke. HIV and AIDS is already wiping out

a generation in Africa.Two decades after it began its onslaught, the disease is still spreading

fast, gaining a firm foothold in all parts of the world.

HIV and AIDS spreads along migration routes charted out by globalised trade. Social

and economic distress due to conflict, war; disasters, skewed international trade and unjust

economic policies make more and more people vulnerable to the infection.

The landmark Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 promised Health for All by 2000 through

primary health care. Verticalisation, changing economic priorities, invasion of pri^^

interests into political decision-making and a lack of political will led to a total breakdown

of the public health and primary health care systems during the 1980s and 1990s.The

spread of HIV and AIDS also contributed to the non-achievement of these goals.

Poverty, hunger and ill health are increasing because of neo-liberal economic policies.

In this context, integrated, adequately-resourced health systems based on primary health

care and public health are urgently required.

Lack of sensitisation and training of health personnel have created negative attitudes

towards persons living with HIV and AIDS. Such attitudes and practices lead to stigma

and discrimination that impede interventions.

It is essential to ensure that health care is safe and that people undergoing treatment

at health care facilities are not exposed to HIV or other infections.

A CALL FOR ACTION

People and Social Movements

People’s Charter on HIV and AIDS

Mobilise and strengthen capacities of communities in health promotion,

prevention and care.

*

W

Empower women and youth as key players in HIV interventions.

Build alliances among positive peoples networks, women's movements, health and

social activists, trade unions, student groups, academics and other progressive

constituencies.

Intensify the campaign for equitable and universal access to anti-retroviral (ABV)

treatment through comprehensive primary health care.

Facilitate legal measures and mass campaigns to change intellectual property rights

regimes that escalate drug prices.

Oppose policies dictated by multilateral financial and trade institutions that disregard

people's right to health and health care.

Expose links between the spread of HIV and AIDS and the underlying societal

determinants such as poverty, war and displacement, and participate in efforts to

redress these injustices.

09 Health Professionals and Health Workers

Provide responsible care and quality treatment to persons living with HIV and AIDS.

Stop stigma and discrimination in institutions of care and treatment.

Respect patients' right to dignity and privacy.

Follow ethical and regulatory principles in drug trials.

^kProvide adequate preventive measures to avoid transmission of infection in health

care institutions.

Support People's Health Movement initiatives that address the larger social, political

and economic issues.

JJ| Governments

Develop and strengthen comprehensive approaches based on primary health care

to include HIV and AIDS interventions.

Enhance involvement of people and civil society in planning and implementation.

Ensure greater involvement of persons living with HIV and AIDS at all levels.

Ensure occupational safety of health workers.

Increase access to basic services to people living with HIV and AIDS

Ensure easy, affordable and sustained availability of quality generic ARV and other

essential drugs.

Implement guidelines for transparent, scientific and ethical clinical trials.

Make nutritional inputs and psycho-social support part of HIV and AIDS care

Develop programmes for life skill education and women’s health empowerment

Promote traditional systems of medicine with enough resources.

Promote harm reduction policies and programmes for all vulnerable sections, including

sex workers, drug users, sexual minorities and street children.

[Tfl Corporates

Place people above profits.

Make available diagnostic and prognostic tests that are affordable.

Ensure the availability of ARV and essential medicines at affordable rates.

People’s Charter on HIV and AIDS '

Allocate adequate resources for public health.

^WHO and UNAIDS

Evolve a comprehensive approach that strengthens primary health care-and health

systems, with built-in indicators of progress.

Stop narrowly-focused vertical programmes.

Urge all governments to follow the UN's International Guidelines on HIV infection

and AIDS and Human Rights.

Include non-pnority countries in the 3x5 initiative.

Take appropriate action in ‘low prevalence countries'.

Start immediate action for sub-Saharan African countries.

Monitor the impact of trade agreements on health.

World Bank, International Monetary Fund and

World Trade Organization

Be accountable for social disasters caused by anti-poor macroeconomic policies.

Cancel debts of all poor countries, especially those identified as vulnerable to HIV

and AIDS.

Stop free trade agreements, privatisation of essential services, and the

commercialisation of health care.

Finance HIV and AIDS interventions with grants instead of loans.

Remove pharmaceutical patents that adversely affect availability of generic drugs.

Q.

a.

o

<u

Largely based on the People’s Charter for Health of the

People’s Health Movement.

1

Developed through an active participatory process involving

people from various walks of life, including persons living with

HIV and AIDS.

For more information contact:

People's Health Movement Secretariat:

CHC, 367, Jakkasandra 1st Main, 1st Block,

Koramangala, Bangalore - S60 034, India

Tel: +91 80 5128 0009; Fax: +91 80 25525372

Email: secretariat@phmovment.org

www.phmovement.org

Deigned by Books for Change. Bangaioto, India

lie’s Charter on HIV and AIDS

We call upon all individuals and organisations to endorse

and implement the People’s Charter on HIV and AIDS and

join the People’s Health Movement (PHM).

PHM has an active presence in about 100 countries.

The Rights Based Framework - Which Way To Go?

Anant Phadke

As a preparation for the discussion on 'right to health care’ in the forthcoming MFC meet,

in this note I would attempt three thingsI. To put the rights based framework in a larger, historical context so that there is more clarity

on the meaning of the issue of rights and human rights

II.

To argue that limiting ourselves purely in the rights based framework, without analysing the

political economy of health and health-care would not take us forward.

111. To locate the need and importance of a detailed discussion on right to health care in the

health-care movement in India.

I

Needs and rights

Let us begin with a simple, elementary question: why do we talk in terms of rights and not

in terms of needs? Food, water, health-care, education etc. are human needs in the modern world.

There are enough resources in the world to meet these basic needs of everyone. But this does not

happen because there are ■ huge wastages on preparations for wars, nuclear or otherwise;

• massive inefficiency in use of resources (for example use of individualised transport instead

of mass transport);

• mind-boggling creation of false needs like unnecessary medical interventions;

All this is basically a product of profit mongering and power mongering capitalist system. Add

to this, the greatest ever inequality in human history fuelled by the shameless greed of a few in the

new phase of globalization and complete sway of speculative finance capital. All this together

makes it impossible to fulfill even the basic needs of the vast-majority of the people inhabiting this

unique globe. Therefore, unless human needs are couched in the form of rights, these cannot be fulfilled

in our today’s society and there is a necessity to talk in terms of basic human rights, the fulfillment of

which has to be ensured by the state. This conversion of basic human needs into rights is not exactly a

very desirable thing. Our ultimate goal should be to build a society wherein basic human needs are

fulfilled without involving the language of rights.

Unlike animals, human needs change and expand. There is nothing like human rights, which

are valid for all times. The content of human needs and of human rights would develop as society

develops. For example, the content of‘Right to education’ would change as society develops.

Professional Rights and Human Rights

Today’s society is divided into various social groups whose interests are opposed to each

other- employers versus employees; landlords’ versus servants; people being benefited by

developmental project versus those displaced by it or suffering from it; men versus women, one

caste - group versus other etc. etc. Each of these social groups is competing with the other to gain

more wealth and prestige. Since resources are limited and especially in view of huge wastages,

inefficiencies, false needs mentioned above, they cannot suffice to meet all these competing needs,

the specific interests and needs of each of these groups have to be protected from others by

converting these needs into rights. In situations where interests of different groups are not opposed

to each other, there is no need to involve the discourse on rights. Thus generally we do not talk

about rights of mothers versus those of their infants. While rights of members of one foot ball

teams are guarded against those of the rival team members by the match referee, there is no

question of any rights of any team member within the team being pitted against those of others. The

point being made here is that the discourse of rights in today’s society is premised on opposed social

groups and their interests.

Human rights belong to a different category of rights. Out interest, needs as human beings, and

not as members of a particular class with particular interests also need to be protected from

violalions from the society in general. If I am old man, my interests, needs arise not out of

belonging to any professional group but arise out of my being an old person. Similar is the case of

not only groups like infants, pregnant mothers who have special needs but is also of many of our

needs as human beings and not as^part of a professional class. However, in today’s society human

interests take the form of interests of a professional class or are intrinsically bound by it. For example,

my interest as tenant-farmer lies in reducing the rent. 1 have to pay my landlord and the fulfillment

of my human interests as an old man partly depends on the protection of my interests as tenant

farmer. If the latter are violated, the former gets threatened. But nevertheless theses two have

different trajectories of development. My interests as tenant farmer are bound up with the existence

of tenant-land lord relationship. With the dissolution of this relationship my interests as tenant farmer will also disappear whereas, my human interests as an old man would continue in any

society.

Our long-term aim should be to build a society not based on antagonistic or opposed

professional interests but based on harmonious co-operative interests. In such a society, particular

class interests and rights will gradually wither away. There will not be a need for a powerful class

state to ensure that the rules of competition between opposed professional classes are observed.

However, there will be some contradiction between human interests of individuals and those of the

society as a whole. This is because the earlier Marxian vision of withering away of scarcity with the

unfettered development of productive forces no more seems to be realistic; energy and other natural

resources no longer seem to be limitless. Hence some amount of limited scarcity would continue, so

also the need to ration resources.' Even though complete plenty and hence a good bye to the

rationing of resources will never be achieved, if exploitation, inequality, ecological-sociaily

destructive use of resources is overcome, modern productive powers can reach a stagq when there

is less and less need to encroach on somebody else's needs in order to fulfill my needs.

To decide how much resources individuals would be entitled to from the common societal

pool would require the presence of a state power to ration the resources. The rights framework and

the state will be required to ensure the fulfillment of human needs of all. This state would not guard the

interests of any particular class or social layer. It would not be a state in the classical sense of the

word but will balance the human rights of individuals with those of the society as a whole. The

point is - the rights framework would be needed even after the withering away of class interests.

II

Political economy and human rights

Protection of civil and political rights is in a sense one of the fundamental principles of the

capitalist society. If the market is to function properly, each buyer or seller in the market has to be

political independent and free. This political equality is no obstacle to the inequality generated by

the logic of the market i.e. the logic of the purchase and sale of different commodities, including

the sale of human labor power. Hence political equality has been guaranteed by constitution in all

capitalist countries. A fair degree of observance of civil and political rights in advance countries

has been quite compatible with great socio-economic inequalities in these countries. However,

people’s organizations/human rights organizations have to be vigilant and fight for consistent

observance of civil and political equality. This is because, though the rulers as a whole have agreed

to recognize political rights, some times individual money bags, blinded by short-term interests and

profits, tend to violate these rights. The altitude of the rulers towards political rights is thus

inconsistent, whereas that of the people’s organizations, civil rights groups is of consistently

upholding of these rights. The US government raises the issue of violation of political rights when

it suits its interests, whereas for us, its a matter of basic principle.

As regards the socio-economic rights, the position of the rulers is much more inconsistent.

Here, it is more of paying lip service to these rights. The rulers are wedded to the interests of

propertied people and not to the interests of the vast majority of the laboring population. Hence

they cannot afford to guarantee the socio-economic rights of the people - right to livelihood, water,

health-care, etc. But there are different sections within the rulers. If health-care becomes very

costly and thereby leads to the demand for higher wages, many employers would like health-care to

become a right to be fulfilled through public funds so that the their wage-bill would not rise an

account of spiraling health care costs. They may thus support the demand for health-care as a right.

But overall, taken together, the rulers are not in favor of granting socio-economic rights, whatever

may be the international declarations. Unlike the civil-political rights, granting the socio-economic

rights is not compatible with the existing social order, at least in the developing countries. When we talk

of fulfillment of socio-economic rights, we have to keep this is mind.

Since some leading United Nation’s organizations talk about economic, social rights also,

we can use these declarations to put pressure on our governments, and we can make some progress

in harnessing some of these rights. But we have to be clear that demand for complete fulfillment of

all the socio-economic rights is actually a revolutionary demand. Just appealing the rulers or

merely demanding from them the socio-economic rights is not going to make any substantial

progress in achieving these rights. Neither is it adequate to keep merely monitoring the violations

of these rights. We have to find out concretely, who would be opposed to our concrete demands

like right to food, right to essential drugs and to health-care, etc. We will have to strategise how to

overcome this opposition; to what extent the existing state can ensure fulfillment of which demand

and why. If we keep away from the political economy of socio-economic rights, we would be merely

indulging into a sterile repetition of nicely worded international declarations or making a list of various

rights or would be kept busy with mere monitoring of their violations. We also need to go into the

political economy of the concerned issue and reveal the forces, which would be in favor of or would

be opposed to this demand, put forward an alternative policy of how things can be done differently if

balance of power is changed. For example, in health care, we have to point out what are the siciopolitical obstacles in achieving the right to health care and how to struggle against these forces.

This point brings us to the third, last issue of my note- the need and importance of a detailed

discussion on the right to health care in the ongoing health movement in India.

Ill

What is our alternative?

The new challenging situation

I would argue that today we are in a challenging, somewhat fluid socio-political situation

and we have to make efforts to shape the changes in health-care policies. The rulers are

restructuring the world. The post-war strategy of state capitalism or welfarism in which the state

played a leading role in the economy, in which the provision of basic social services was

considered the responsibility of the state, is now being abandoned. In India, the Nehruvian path of

development is being left behind. Thanks to the Nehruvian model of state capitalism in India, there

was a relatively very rapid development after independence. But this development has unleashed

new problems, which cannot be solved by merely continuing the Nehruvian policies. The economy

needs restructuring.

The rulers are trying to restructure the economy with their trinity formula of Globalisation,

Liberalisation, Privatisation (GLP), which suits the rulers but spells disaster for the ordinary people.

We need to formulate and press for an alternative strategy of restructuring in opposition to the GLP

strategy. In the field of health-care it is not adequate to oppose the various elements of ‘GLP in

health care’ in a piecemeal manner. Nor can we demand going back to the Nehruvian era. Our

opposition should be based on an alternative plan for restructuring of the health care system in India.

‘Right to health care’ can be the rallying slogan, theme of this alternative framework. Thus the

direct, indirect privatisation of public health services should be opposed on the basis of an

alternative framework of Universal Health Insurance of which a very much reformed, efficient,

accountable, expanded public health services would be a part. Our alternative policy could be

‘reform the public sector and regulate the private sector.’ (Instead of giving a call of ‘Save the

Public sector’ it will be more appropriate to give a call - “reform and expand the public sector;

regulate the private sector'.) In our plan for reforming the public health services, by way of

example, on the issue of accessibility of Primary Health Care we can argue for * a much more important role for Community Health Workers and their much better

integration into the public health services;

• much more accountability of the health services to the community and to the patients;

• a more rational use of the PHC staff by introducing multi-tasking wherever possible.

The point is. the current system is obsolete, the rulers are restructuring it with their GLP

strategy and our opposition to it has to be based on an alternative policy, which goes beyond the

Nehruvian model of development. Whether one is part of the system or want to reform it or

revolutionise it. today, one needs to go into the debates about strategic, policy issues. MFC offers a

broad platform for such debates.

The MFC debates

In the earlier MFC - annual meets, we have discussed in some detail various policy-issues

ranging from medical education to drug policy to women’s health. The People’s Health Charter of

the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, of which MFC is a part, summarises our alternative on 20 crucial

aspects of a comprehensive alternative policy. Amongst us there can be differences of opinion

about some of these measures in this ‘twenty point programme’. But this Charter is an indication

that the Right to Health Care movement in India has not confined to a conventional ‘rights based

approach’ but has also involved itself in formulating alternative policies and'has time and again

pointed out specific changes in the current policies. We have thus not confined ourselves to merely

making a list of various health-rights of the people, but have argued for concrete policy-measures

needed to make health-care accessible to all. Now what needs to be done is to show concretely that

India has the resources to implement the various policy measures we have been arguing for. This is

necessary because officials, politicians say that they agree with the measures we have been

suggesting but say that “However, the state does not have the resources.” We need to work out at

least to a certain extant, how much funds would be required to institute the measures we are

suggesting and how the state can raise the resources to meet these funding requirements. This is

necessary to delegitimise the existing system and to move from a purely oppositional to a hegemonistic

politics. People will come forward to fight for these rights and there will be broader support to such

struggles if we are able to show that Indian economy has the resources, but the existing rulers are

not ready to harness these resources as this would involve harming the interests of those sections to

which they are wedded.

1 hope that the MFC meet would recognize the need to overcome the “there is no

alternative” (TINA) syndrome. Let us realise that policy-measures that we discussed in earlier

meets have acquired new significance as we have entered the era of restructuring of the economy

and society. In this new context let us revisit various policy measures we had debated. Let us

decide, how as part of the JSA, in this new situation we can contribute to pushing forward measures

which we had formulated earlier. MFC provides an open space for detailed discussions on the

content of various policy measures. Let us use this space more productively in the new situation.

The election results during the last few months have shown that people are expecting an

improvement in their daily lines. Emotional issues have been pushed back. The rulers are under

pressure to show results. In this fluid situation, policy - level interventions are likely to be much

more productive than hitherto. Now is the more opportune time to put pressure on the system, to

expose it. But we need to raise the quality and quantity of our efforts in this direction. Can MFC do

this?

2814 words

A statement from the People’s Health Movement prepared for presentation at

Making Partnerships Work for Health, a workshop at the

World Health Organization, Geneva, 26-28 October, 2005.

*

PHM identifies exploitation and marginalization of the poor as root causes of preventable

disease, malnutrition and death and in this and many other respects, women and children

are particularly vulnerable. This awareness guides all of our work including our position

on partnerships for health.

We start with a simple observation. Partners in any endeavour must genuinely share

a common goal. If they do not. the interaction is not a partnership and its precise nature

must be made clear for its real value and the real risks it may pose to public health, to be

properly evaluated.

With that in mind, we look first at interactions that are called ‘public private

partnerships’, because they are increasingly portrayed not just as a possible

arrangement - but as an innovative and unavoidable policy paradigm - to address

global health problems.

The Cuenca Declaration, issued at the Second People’s Health Assembly in July 2005 in

Ecuador, states: “We oppose public-private partnerships because the private sector has

no place in public health policy making”. We will elaborate on this here.

The extraordinary power of the private sector, and in particular of transnational

corporations (TNCs) and pharmaceutical houses under the neoliberal, corporate-led

globalization process, has been identified as the major obstacle to achieving social and

economic justice and therefore, also, Health for All.

TNCs already exert enormous power over governments and International Financial

Institutions (IFIs). Through PPPs, they are becoming major players in many areas of

public policy making, including health.

Let us clarify some fundamental democratic principles. All citizens are involved and

concerned in health matters as individuals (including employees and Chief Executive

Officers of TNCs). However, until recently it has been considered an unacceptable

conflict of interest to include TNCs as decision makers in public policy.

WHO has always interacted - and often collaborated - with private sector and other non

state actors. What is currently subsumed under the term partnerships with the private

sector includes such diverse activities as corporate donation, sponsorship, research

collaboration, negotiation or public tenders, and contracting out of selected health

services. It also includes global health alliances, such as GAVI, GAIN and the Global

Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria which involve high level policy interactions between

UN agencies, corporations, and private foundations which propagate a business

philosophy.

Many of these interactions are not fundamentally new; others are social experiments.

Some, such as the outsourcing of public health services, the funding of international

public health and UN agencies through corporate charity and the GAVI style health

alliances are highly problematic.

What is new - and of serious concern in most current PPPs - is that industry is

invited as a ‘full partner’ in decision making processes on public issues.

Today, the UN Secretary-General’s Report on Enhanced cooperation between the United

Nations and all relevant partners, in particular the private sector, states that it offers to the

private sector through engagement in governmental processes “opportunities to have its

voice heard.”1'11

PHM argues that, in terms of both process and outcome, these developments are

incompatible with democratic decision making, economic justice, emancipatory

development, human rights including the right to health - and therefore the

achievement of Health for All.

A second simple observation is that TNCs have a legal obligation to make a profit for

shareholders. The raison d'etre of private companies is completely different from

that of organizations and groups working for Health for All and the meeting of

people's basic needs for health as a human right.

We have only time to present tlie briefest summary of some of the risks to public health

that this difference implies.

Public private partnerships:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Allow private interests to set/influence the public health agenda.

Sacrifice broad public health goals of prevention of disease, protection and

promotion of health, and tackling of the underlying social and economic

determinants of avoidable disease and death.

Prioritize technological interventions, cosmetic and unsustainable, which generate

profit for a minority.

Favour short term, vertical approaches and privatization of essential public

services rather than horizontal, comprehensive and sustainable public services.

Provide legitimacy to corporations' activities through association with UN

agencies (blue-washing); blur roles and real interests.

Compromise public agencies, including UN agencies, and make them ‘call the

tune’ for private interests of a tiny privileged minority rather than for 6 billion

people.

1111 UN (2005). Enhanced cooperation between the United Nations and all relevant partners, in

particular the private sector. Report of the Secretary-General, A/60/150,10 August, para 20

As a policy paradigm, then, the PHM regards PPPs as fundamentally flawed. It thus

follows that the actual evaluatiqn of the effectiveness of particular PPPs in practice is of

limited interest. PHM cautions that almost any project can demonstrate "effectiveness"

within a narrow context using a specific set of indicators - if enough money is thrown at

it by powerful actors, over a short space of time.

Evaluations of selected PPPs have been undertaken - though few of these have

considered risks and harm in the widest sense - and the results have been variable. PHM’s

conclusion is that PPPs arc ideology-driven rather than evidence-based. If one takes

privatization of health services as an example (as this is prominently promoted through

PPPs), no serious studies have yet shown that privatization of health services is either

efficient or effective. A wealth of evidence exists, however, to show that national,

universal, publicly run and funded health services are significantly cheaper and produce

far better health outcomes.

So what kind of partnerships does PHM recommend? PEIM promotes a broad based

holistic approach to health which involves common struggles in a spirit of solidarity.

Individuals and groups with whom WHO could work as partners need to share

goals and represent people's interests in terms of their right to health.

This would include health workers, public service workers, trade unions, teachers,

community workers, indigenous people's movements, landless peasants' movements,

community groups, solidarity movements, public interest NGOs, civil society

organizations, social justice political parties, professional associations and many more.

We support solidarity between groups and organizations serving the public interest

within, across and beyond the health sector in order to address the major determinants of

preventable disease, malnutrition and death because it is through such arrangements

that human rights and the right to health, which only some of us enjoy, have been

won.

We must never forget that these rights have been won painfully and slowly, with much

suffering and loss of life for the poor - and against formidable obstacles in the form of

powerful, private interests.

We cite as examples the efforts undertaken by various groups working in solidarity

towards Health for All to address the lack of food and water, bearing in mind that:

a) these two factors together account for well over 60% of preventable disease and death,

b) mothers and children are always the primary victims in times of shortage, and

c) that women are largely responsible for the provision of these daily essentials.

• Access to water and to essential services has been won through partnerships

between public sector workers, their unions, local community groups and health

workers in countless places the world over, most notably in Cochabamba, Bolivia.

• The struggle for food sovereignty, critical to adequate consumption of high

quality food, is the joint struggle of landless peasants' movements’, opponents of

liberalization of the agricultural sector, and the tremendous worldwide movement

for social and economic justice that has been meeting at the World Social Fora.

Such solidarity struggles involving collaboration between public interest groups confront

the formidable and overwhelming power of TNCs that are behind the neoliberal

restructuring of our world and increasing poverty and inequality - the first causes of poor

health.

Referring now to this meeting at the World Health Organization:

Why are agencies and organizations with public responsibilities adopting these

arrangements? For the simple reason that, today, the private sector is considered the

only untapped source of funds. The term PPP encompasses essentially the hope to

access funds of corporations and some hyper-rich. Under neoliberal economic regimes,

public sector budgets have been slashed and tax bases destroyed. These developments are

themselves the result of the influence of TNCs on governments and the international

financial institutions.

The solution to this problem is not for public bodies to go knocking at the doors of

the private sector, nor of the foundations of celebrity philanthropists from industry. The

solution is economic justice, including an adequate tax base, both nationally and

internationally, to cover all public services, as well as proper funding of public

institutions such as WHO through regular budgets so that it may fulfill its international

responsibilities unimpeded by corporate interests.

In relation to ‘Making Partnerships Work for Health’, we urge the World Health

Organization to keep to the founding principles set out in its Constitution. In particular

the following parts of the preamble:

"Informed opinion and active cooperation on the part of the public are of the utmost

importance in the improvement of the health of the people."

"Governments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples which can be fulfilled

only by the provision of adequate health and social measures."

The PHM urges WHO to claim its rightful place as the international health

authority and to ensure, with governments, accountability to the people, not to private

interests - in all matters of health. Our message is simple: Work with the people, for the

people!

Together, we can achieve Health for All.

*: For reasons beyond PHM control, the statement was not read at this workshop.