COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT APPROACH FOR FAMILY WELFARE IN INDIA

Item

- Title

- COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT APPROACH FOR FAMILY WELFARE IN INDIA

- extracted text

-

RF_COM_H_71_SUDHA

Project "Enhancing nrenaredness formanas...f Enidemics in Bangalore" from Dr. Girish

:

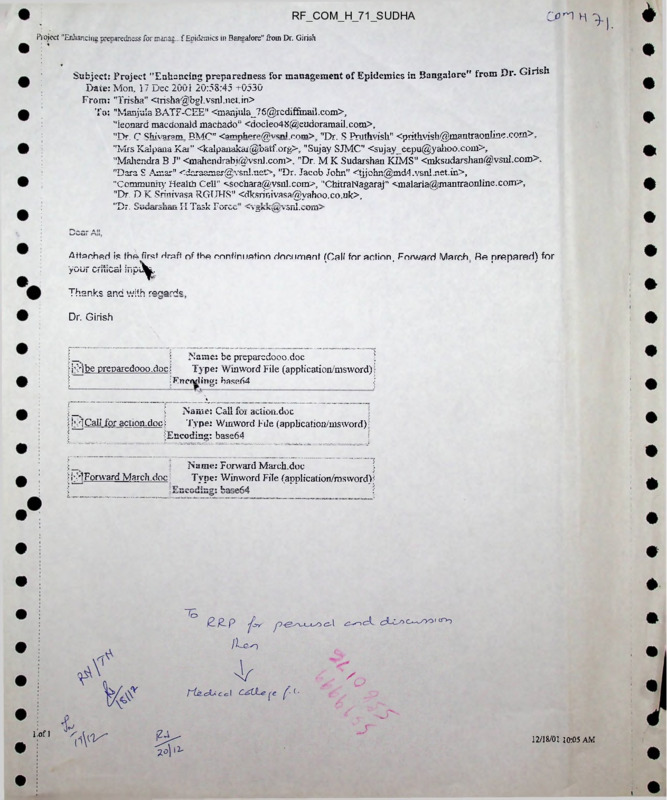

Subject: Project "Enhancing preparedness for management of Epidemics in Bangalore" from Dr. Girish

Date: Mon, 17 Dec 2001 20:58:45 -t-0530

From: "Trisha" <trisha@bgl.vsnl.net.in>

To: "Manjula BATE-CEE" <mar.jula_76@rcdiffinail.com>,

"leonard macdonald machado” <docleo48@eudoramail.com>,

"Dr. C ^hivaram BMC' <amnhpre@vsn1 c<->rn> "Dr. S Pruthvish" <prithiish@mantraonline.coni>,

"Mrs Kalpana Kai” <kalpanakar@batf.org>, "Sujay SJMC" <sujay_eepu@yahoo.com>,

"Mahendra B J" <mahendrabj@vsnl.com>, "Dr. M K Sudarshan KIMS" <mksudarshan@.vsnl.com>.

"Dara S Amar" <daraamar@vsnl.net>, "Dr. Jacob John" <tjjohn@md4.vsn!.net.in>,

“Community Health Cell" -ssochara@vsnl.com>, "ChitraNagaraj" <malaria@manrraonline.com>,

"Dr. D K Srinivasa RGTJHS" <dksrinivasa@yahoo.co.uk>,

"T>T.T T„„1. T?------ —1

x/i. o uuru oucm jl x laoniurvv

'y jruv^O roiu.cOrrt'

Attached is thA first draft of tho continuation document (Call for action, Forward March. Ra prepared) for

yo’uf critics! inpi^^.

Thonke

ond

. —....

.— u/ith ranarHc

Dr. Girish

•i

i

Name: be preparedooo.doc

i j</)be preparedooo.doc;

Type: WinWord File (application/msword);

iFncivling: base64

;

i

Name: Call for action.doc

i i'?>]CaIl for action.doci

Type: Wmword File (application/msword) ■

(Encoding: base64

!

H-IForward March.doc?

Name: Forward March.doc

Type: Winword File (application/msword):

1----r-aZA

Lofl

12/18/01 10:05 AM

Enhancing preparedness for management of Epidemics in Bangalore

<7 public health advocacy endeavour

be prey iireiooo

$ The city of Bangalore witnessed outbreak of

ti’ Gastroenteritis during the months of February and

Ij’ March 2001. During the consultation held by Of flee of

tif the Chief Health Officer, BIvfD it was decided to focus

on not just the immediate and short term but plan for

medium term as well as long term to combat: future

outbreaks. It was recognised that there was; a need to

initiate a systematic and co-ordinated effort at the city

level to monitor and forecast epidemics. Sanitsiry

$ vending of food and aspects of food hygiene: was

another key issue.

Adopting the “call for action’ and “marching forward’

to document the micro-epidemics and enhance the

preparedness of the health staff and heeilth care

facilities, the Core team has faciliiated the following

endeavours.:

a) Formaticon of the Epidemic Combat Task Force,

ECTF and the Joint Monitoring teams, JMT. The

perceived responsibilities and activities of the team

as agreed upon by the members lia.ve been

ir formulated.

b) Drafting the Epidemic Manual for die city cf

Bangalore.

% Effoits are currently on to delineate flic most

appropriate system for flow of information from the

different health care institutions ('Ihe Se ntinel

O J

u

Reporting Centres). This is necessary because the city

should be prepared to adequately respond to

outbreaks and ensure for its citizens a desirable A>

health status.

A preliminary planning interaction is scheduled on til

tire Tuesday, the 8th January 2002 at Juana Jyothi, “w

???Training Centre for Urban Affairs, adjacent V

Chowdiah Memorial hall, opposite Veidika Sablia,

Kodandaramapuram, Bangalore. Ihe agenda for til’

group discussion is finalising the Reporting formats, ti’

Flow of information, Case management stratejjies, til'

and Responsibilities of individual stakeholder.

tif

The major outcome of the deliberations would be to

arrive at the Calendar of events for the different a,

stakeholders. This would enable the city to anticipate S,

an outbreak aid appropriately respond to it.

□,

Concurrent efforts are on towards ensuring the Safe

vending of foods. Banning the vending is difficult;

conf.sca.ting and seizing the food snicks is

labourious. The lessons learnt from ihe ongoing

mcdel WHO-GOI project in Bangalore are' given

alongvrith.

More details of all the endeavour is available on ti’

request

til

Do not be part of the rumour.

o_>

tii

O >

tii

Cnii

,5x_-z

gfar

nJ'a 1A f*fin

O'G'^lt omi

w

Ij

1 ^?z7r>i'o-**<'>*r «««■/•

W**».*«*.

|

| In the wake of the outbreak of Gastroenteritis in the city during the months of February and March

I 2001 the Office of the Chief Health Officer and other concerned officials had scheduled an

I interaction with the facility from the departments of Community Medicine and Paediatrics from tne

I

Medical Colleges of Pangalore City, RWSSR officials, Superintendent of ED Hospital and select

j NGGs. The consultative group met on the if’ of March 2001 and 7"' of April 2001.The interaction

I focussed on the immediate, short term, medium term as well as long term plans to combat this and

future outbreaks.

The meeting analysed the existing situation as:

Reports in the media are usually the source ofinformation of the outbreaks.

The exact cause of the early outbreak in February 2001 could not be ascertained.

immediate measures undertaken included super-chlorination (apart from establishment of Help

fiiis siiH’ e fellb1.

cases being reported.

4. Enforcement ofSanitary vending offood needs to be publicised

5. A systematic and co-ordinated city level effort needs to be initiated.

1.

2.

3.

1

I

t t?o.o a r'TTfW.

I

I

I

a) Document the mici o-epidemics9 which precede the larger ones.

I

I

0 Set up a vigilant health inionnation gathering system utilising the sanitary health I

inspectors, health workers and Link workers with inputs from the local general I

I

practicitoners. nursing homes and hospitals. Lay reporting systems to be initiated. The I

mass media to be made a partner in the endeavour. An uniform, common, simple and II

I

comprehensible reporting format to be utilised.

I

❖ An. intersectoral emergency response team to assess the day to day situation and take

necessary intervention.

b) Enhance the preparedness of the health staff and health care facilities with proactive

support from the City fvledical Colleges.

b

Orient and sensitise the faculty at Isolation hospital regarding principles of

epidemiological investigation. Strengthen the available facilities including staff to

combat the epidemic.

o Make available module / protocol for standard case management and investigation at all

Offices of the MOH.

c) Immediately address the Hygiene and Sanitation of the street food vendors.

o Make available potable water and appropriate sanitary facilities at common street food

vending locations (FOOD COURTS).

♦ Orient and sensitise (Food Handlers; Food Inspectors') regarding hygienic food

handling and vending methods.

d) Undertake regular and frequent intersectoral meetings.

e) Delineate iong term solutions for water and sanitation problems.

Eiiiia.il cuts preparedness for management of Epidemics m Eangalorc

a nnhlic health advocacy endeavour

FOR W A* RD MARCH

Background:

In the wake of the outbreak of Gastroenteritis in the city during the months of February and

March 2001 a consultation was held by Office of the Chief Health Officer, BMP with the

faculty of medical Colleges in Bangalore City, BWSSB officials, Superintendent of ED

Hospital and select NGOs. The consultative group naa interactions and decided to rocus on

not just the immediate and short term but also plan for medium term as well as long term

pl2ns to combst future outbreaks.

The major lacunae in the existing reporting system was that it was not uniform nr complete If

not al! the health care settings, it did not cover even the major health care establishments in

the city. There was a need to initiate a systematic and co-ordinated effort at the city ievei to

monitor and forecast epidemics apart from publicising the enforcement of sanitary vending of

food and aspects of food hygiene

Adopting the call for action to document the micro-epidemics and enhance the preparedness

of the health staff and health care facilities with proactive support from the City Medical

Colleges and concerned NGOs a host of activities have been initiated.

The proposal to establish an Epidemic Management Col! for the city which has the

objective of not just to respond and function as the Information Ceil but also become a

barometer for the health status of the City.

The members drawn from multiple and broad based background constitute the health

intelligence input requirements in the City. When called for, due to an epidemic or out

break, they have overriding powers, enabling them to co-ordinate and execute the

p.scssssp' setion for s^idsmic control. The m.2’or h02lth coro institutions in ths citv to

bvCOiTiv Sentinel Surveillance Ui’iitS Shu the SysteiTi Of infonTiStiOH nOVv tO be

continuously monitored accoramg to a calendar of events.

2. The formotion of the Joint Inspection Teem, JIT 2nd the Epidemic Cornbet Tssk Force,

1.

Tho 5 JITc Aac.h comprising of a Deputy Health Officer of RMP and an Executive

Engineer each from tho Engineering departments of BMP and BWSSB would draw cut a

pioiocoi 1'01 inspection and rnoniioiing.

The FCTF comprising of the Zonal Health Officers of RMP, Additional Chief Engineers of

BWSSB and Zonal Chief Engineers of BMP would review the emerging situation and

take necessary action with technical support from the Medical Colleges, State and

National Institutions of Health, Professional Bodies and NGOs.

3.

A One-day workshop is to be scheduled on Friday, 21st December 2001 to arrive at the

consensus system that will be in place for the City with effect from 131 January 2002. The

convenors for the subgroups are as follows: Case Definition and Management Protocols

— Dr. Sujay, SJMC; Case 'investigation Protocols — Dr. Girish, MSRMC; Information

Dissemination - Dr. Mahendra, KIMS.

Enclosed alongwith is the name, address and contact for communication. The endeavour

is pan ot the Citizen - Government initiative to take Bangalore Forward.

Please do indicate your willingness to be a partner in the endeavour.

POLICY BRIEF

C.cw-> H - 3-1.

One oi the best ways to judge the well being of the

people of any nation is by examining the standards

oi health that ordinary people have attained.

Healthy living conditions and access to good quality

health care for all citizens are not only basic

human rights, but also essential prerequisites for

social and economic development. Hence it is high

time that people’s health is given priority as a

national political issue. The current health

policies need to be seriously examined so that new

policies can be implemented in the framework of

quality health care for all as a basic right. The

following sections first take a look at the hard

realities of people’s health in India today, and

examine some of the maladies of recent health

policies. Next the availability of various resources,

which could be utilised for an improved health care

system is discussed, finally followed by certain

recommendations to strengthen and reorient the

health system to ensure quality health care for

all. We hope these recommendations will be

Infant and Child mortality snuffs out the life

of 22 lakh children every year, and there has

Three completely avoidable child deaths

occur every minute. If the entire country were

been very little improvement in this situation

in recent years.'■ We are yet to achieve the

National Health Policy 1983 target to reduce

Infant Mortality Race to less than 60 per 1000

live births.-' More serious is the fact that the

rate of decline tn Infant Mortality, which was

significant in the 1970s and 80s, has slowed

down in the 1990s, (See graph below)

to achieve a better level of child health, for

example the child mortality levels of Kerala,1

then 18 lakh deaths of under-five children

could be avoided every year. The four major

killers (lower respiratory tract infection,

diarrheal diseases, perinatal causes and

vaccine preventable diseases) accounting for

over 60% of deaths under five years of age are

entirely preventable through better child health

care and supplemental feeding programs.-' The

most recent

estimate of complete

immunization coverage indicates that only

54% of all children under age three were fullyprotected.4

o

incorporated by political parties in their election

manifestos for the upcoming general election as

a demonstration of their commitment to public

health. Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, a national platform

working for people’s health, looks forward to such

a commitment from all political forces in the

countrv.

130,000 mothers die during childbirth every

year. The NHP 1983 target for 2000 was to

reduce Maternal Mortality Rate to less than 200

oer 100,000 live births. However, 407 mothers

die due to pregnancy related causes, for ever.'

100.000 live births even today.1 In fact, as per

the NFHS surveys in the last decade Maternal

Mortality Rate has increased from 424 maternal

deaths per 100.000 live births to 540 maternal

deaths per 100,000 live births.3

■ About 5 lakh people die from tuberculosis

every year18, and this number is almost

unchanged since Independence!19 20 lakh new

cases are added each year, to the burgeoning

number of TB patients presently estimated at

around 1.40 crore3 Indians !

•

India is experiencing a resurgence of various

communicable diseases including Malaria,

Encephalitis, Kala azar, Dengue and

Leptospirosis. The number of cases of Malaria

has remained at a high level of around 2

million cases annually since the mid eighties.

By the year 2001, the worrying fact has

emerged that nearly half of the cases are of

Falciparum malaria, which can cause the

deadly' cerebral malaria. The outbreak of

Dengue in India in 1996-97, saw 16,517 cases

1

such deaths might be prevented by tobacco

control measures2.

and claimed 545 lives3. Environmental and

social dislocations combined with weakening

public health systems have contributed to this

resurgence.

•

■

Diarrhea, dysentery, acute respiratory

infections and asthma continue to take their

toil because we are unable to improve

environmental health conditions. Around 6

every 5 minutes3!

lakh children die each year from an ordinary

illness like diarrhoea. While diarrhea itself

As a nation, today there is a need to look closely at

the deep problems in the health system, rather

than making exaggerated claims. There is a need

to recognize the growing health inequities, and

urgently implement basic changes in the health

system.

could be largely prevented by universal

provision of safe drinking water and sanitary

conditions, these deaths can be prevented by

timely administration of oral rehydration

solution, which is presently administered in

only 27% of cases3.

.

Estimates of mental health show about 10

million people suffering from serious mental

illness, 20-30 million having neuroses and 0.5

to 1 percent of all children having mental

retardation2. One Indian commits suicide

With political will and people’s involvement,

ensuring good quality health care for every Indian

is possible!

Cancer claims over 3 lakh lives per year and

tobacco related cancers contribute to 50% of

the overall cancer burden, which means that

The growing inequities in health and health care are unjust!

The Constitution of India guarantees the “Right to

Life’ to all citizens. However, the disparities relat

ing to survival and health, between the well off and

the poor, the urban residents and rural people, the

adivasis and dalits and others, and between men

and women are extremely glaring.

.

The Infant Mortality Rate in the poorest 20%

of the population is 2.5 times higher than that

in the richest 20% of the population. In other

words, an infant bom in a poor family is two

and half times more likely to die in infancy,

than an infant in a better off family3.

•

A child in the ‘Low standard of living' economic

group is almost four times more likely to die

in childhood than a child in the better off ‘High

standard of living' group. An Adivasi child is

one and half times more likely to die before

the fifth birthday than children of other groups3.

•

A girl is 1.5 times more likely to die before

reaching her fifth birthday, compared to a boy!

The female to male ratios for children are

rapidly declining, from 945 girls per 1000 boys

in 1991. to just 927 girls per 1000 boys in 200116.

This decline highlights an alarming trend of

discrimination against girl children, which

starts well before birth (in the form of sex

selective abortions), and continues into

childhood and adolescence (in the form of worse

treatment to girls)3L2

>

Dalit Women are one and a half times more

likely to suffer the consequences of chronic

malnutrition (stunted height) as compared to

women from other castes. Children below 3

years of age in scheduled tribes and scheduled

castes are twice as likely to be malnourished

than children in other groups.

a

A person from the poorest quintiie of the

population, despite more health problems, is

six times less likely to access hospitalization

than a person from the richest quintile. This

means that the poor are unable to afford and

access hospitalization in a very large proportion

of illness episodes, even when it is required.

•

The delivery of a mother, from the poorest

quintile of the population is over six times less

likely to be attended by a medically trained

person than the delivery of a well off mother,

from the richest quintile of the population. An

adivasi mother is half as likely to be deliuared

by a medically trained person3.

.

The ratio of hospital beds to population in rural

areas is fifteen times lower than that for urban

areas14.

•

The ratio of doctors to population in rural areas

is almost six times lower than the availability

of doctors for the urban population14.

•

Per person, Government spending on public

health is seven times lower in rural areas,

compared to Government health spending for

urban areas.

These health and health care inequities are

increasing, and are deeply unjust — a just health

system would ensure that all citizens, irrespective

of social background or gender, would get basic

quality health care in times of need.

Public health being w<eakened, people’s health being undermined

the most privatised in the world. Only five other

countries in the world are worse off than India

regarding public health spending (Burundi,

Myanmar, Pakistan, Sudan, Cambodia6). The

W.H.O. standard for expenditure on public health

is 5% of the GDP. The average spending today by

Less Developed Countries is 2.8 % of GDP, but India

presently spends only 0.9% of its GDP on public

health, which is merely one-third of the less

developed countries’ average6 !

The XDA Government has recently claimed that

one of its signal achievements has been the

allocation of 6% of GDP to Health care. In reality,

the government spends just 0.9 % of the GDP on

Health care and the rest is spent by people from

their own resources. Thus only 17% of all health

expenditure in this country is borne by the

government — this makes the Indian public health

system grossly inadequate to meet healthcare

demands of its people, and makes the health sector

The consequence of this dismally low allocation,

which stands at the lowest levels in the last two

decades, (in contrast to 1.3% of GDP achieved in

1985). is deteriorating quality of public health

services. For example, Primary health centers

(PHCs), meant to serve the needs of the poorest

and most marginalized people have the following

shocking statistics:

•

.

k

o

•

o

Only 38% of all PHCs have all the critical

staff

Only 31% have all the critical supplies

(defined as 60% of critical inputs), with only

Source: 7

3

3% of PHCs having 80% of all cntical inputs.

In spite of the high maternal mortality

ratio, 8 out of every 10 PHCs have no

Essential Obstetric Care drug kit!

Only 34% PHCs offer delivery services, while

only 3% offer Medical Termination of

Pregnancy!

A person accessing a community health

center would find no obstetrician in 7 out

of 10 centers, and no pediatrician in 8 out

of 10!

Private health, care and essential drugs are increasingly unaffordable !

The dominance of the private sector not only denies

access to poorer sections of society, but also skews

the balance towards urban biased, tertiary level

health services with profitability overriding equity.

and rationality of care often taking a back seat.

.

Irrational medical procedures are on the rise.

According to just one study in a community in

Chennai. 45% of all deliveries were performed

by Cesarean operations, whereas the WHO has

recommended that not more than 10-15% of

deliveries

would

require

Cesarean

operations17.

A growing proportion of Indians cannot afford

health care when they fall ill. National surveys

show that the number of people who could not

seek medical care because of lack of monev

increased significantly between 1986 and

1995:5. The proportion of such persons unable

Due to irrational prescribing, an average of

63 per cent of the money spent on prescriptions

is a waste. This means that nearly two-thirds

of the money that we spend on drugs may be

for unnecessary or irrational drugs-1!

to afford health care almost doubled.

increasing from 10 to 21 % in urban areas, and

growing from 15 to 24% in rural areas in this

decade15.

The pharmaceutical industry is rapidly

growing...yet only 20% of the population can

access all essential drugs that they require.

There is a proliferation of brand names with

over 70,000 brands marketed in India, but the

2002 Drug policy recommends that only 25

drugs be kept under price control13. As a result.

many drugs are being sold at 200 to 500 p^ent

profit margin, and essential drugs have bSrr.e

unaffordable for the majority of the Indian

population.

Forty percent of hospitalised people are forced

.

to borrow money or sell assets to cover

expenses15.

•

Over 2 crores of Indians are pushed below the

poverty line every year because of the

catastrophic effect of out of pocket spending on

health care-'"!

HeaTtfc policy developments: since the 1990s- have critically:

weakened! the: health; system

;

The effectiveness of the public health system and

access to quality health care, especially for the poor

has worsened since the decade of the 1990s. due

to a variety of policy developments, at both national

and state levels:

•

Stagnant public health budgets and

decreasing Government expenditure on

capital investment for public health

facilities.

•

introduction of user fees at various levels

of public health facilities.

•

Freezing of new recruitments and

inadequate budgets for supplies and

maintenance in the public health system.

•

Contracting out health services or

privatisation of health facilities.

•

Encouragement of growth of private

secondary and tertiary hospitals through

tax waivers, reduced import duties.

subsidized land etc. which have led to a

further expansion of the unregulated

orivate medical sector.

Promotion of ‘Health tourism’ for foreign

visitors, while basic health services remain

inaccessible for a large proportion of the

Indian population.

Conducting occasional, expensive and

largely ineffective ‘Health melas’ instead

of upgrading the public health system as a

sustainable solution.

Deregulation of the pharmace^cal

industry, lax price controls on drugs— the

list of drugs under price control being

proposed to be reduced to 25 drugs

(compared to 343 drugs under orice control

in 1979.)

Many bulk drug manufacturing units have

closed down due to liberalized import and

dumping as a result of the implementation

of the WTO agreement and autonomous

economic liberalization policies. Due to

reduction of customs duty and increase ot

excise duty, imported drugs will become

cheaper while local drugs will become more

expensive.

4

Indians need not accept poor health as their

inevitable fate! Many other developing countries.

’■vhich nave given a high priority to people’s health,

have achieved much better health outcomes

compared to India. As a country, we spend a higher

proportion or the GDP on health care compared to

these countries - but an overwhelming percentage

of this (83%) is private expenditure. As a result we

have a weak public health system with poor health

outcomes forcing families to spend a lot on private

medical care, which is expensive, and not always

appropriate, leaving us with ‘poor health at high

cost’! Here is how some other Asian countries are

doing in comparison with India...

Health Outcomes in Relation to Health Expenditures in some Asian countries10

Total Health

Expenditure

as % of GDP

L

Public Health

Expenditure

as % of total

Under 5

Mortality

Life Expectancy

Male

Female

India

5.2

17

95

59.6

61.2

Sri Lanka

3.0

45.4

19

65.8

73.4

Malaysia

2.4

57.6

14

67.6

69.9

Does India have tiie resources ta provide health care for all ?

As a country. Indians spend more on health care

than most other developing countries, but this is

mostly out-of-pocket spending. Health care

facilities have grown substantially, but these are

mostly in the private sector. The system is

producing more and more healthcare professionals.

but we lose them to the private sector, or to western

countries. To give some idea of the available health

care resources in India -

.

Compared to 11,174 hospitals in 1991 (57%

private), the number grew to 18.218 (75%

private) in 2000'7 In 2000. the country had

12.5 lakh doctors and 8 lakh nurses! At the

national level, there is one allopathic doctor

for every 1800 people, or one doctor from

systems including ISM and homeopathy for

SOO people. This means there are more

doctors than the required estimate of one

doctor for 1500 population-

•

Approximately 15.000 new graduate doctors

and 5.000 postgraduate doctors are produced

every year and one-fifth of them leave the

country for greener pastures-4.

o

We have an annual pharmaceutical

production of about 260 billion rupees--, and

we export a large proportion of these drugs

- Sadly, while our exports grow. 80% of our

people do not have access to all the drugs

they require.

In short, we have substantial health care

resources, but because of the privatised.

unregulated and inequitable nature of the health

care system, it is unable to ensure good quality

health care for a majority of citizens. Rather than

producing more doctors or setting up more private

hospitals, what we need is a reorganisation of the

health system, with substantial strengthening of

public health, greatly enhanced public expenditure.

regulation of the private medical sector and an

overall planned approach to make health care

resources available to all.

5

.What can be done as immediate steps ?

increased substantially, targeting the 5%

of GDP as public expenditure on health care

as recommended by the WHO.

. If the public health system fails to deliver

it should be treated as a legal offence.

remedy for which can be sought in the

courts of law. The public system must

ensure all elements of care like drug

prescriptions, diagnostic tests, child birth

services, hospitalization care etc. One way

to ensure this could be that in exceptional

situations, where patients who do not

receive these services from the public

facility they may be referred to seek them

from alternate facilities, which are

registered with the state agency. Such

registered and regulated facilities would

honour such referrals, for which the state

would reimburse them at a mutually agreed

rate. This would maintain pressure on the

public health system to provide all eleme^e

of care, and would ensure that the patiWt

is not deprived of essential care at time of

need.

o Various vulnerable and marginalised

sections of the population have special

health needs. There is a need for a range

of policy measures to eliminate

discrimination, and to provide special

quality' and sensitive services for women.

children, elderly persons, unorganised

sector workers, HIV-AIDS affected persons.

disabled persons, persons with mental

health problems and other vulnerable

groups. Similarly, situations of conflict.

displacement and migration need to be

addressed with a comprehensive approach

to ensure that the health rights of affected

people are protected. The People’s HetUfcb.

Charter deals with issues related to s'Wi

special sections of the population, and can

provide a basis for formulation of

appropriate policy initiatives, in

consultation

with

organisations

representing these social segments.

• Putting in place a National legislation to

regulate the private health sector, to adopt

minimum standards, accreditation.

standard treatment protocols, standardised

pricing of services etc.

. Adopting a rational and essential

medications-based drug policy. All States

must have an essential drugs and

consumables list and all the drugs and

consumables on this list must be under

price control. Further all state governments

must adopt procurement and distribution

The objective should be to make Health care a

Fundamental right and an operational

entitlement. This would require a National Public

Health Act, which mandates right to basic

healthcare services to all citizens through a

system of universal access to healthcare. The

Indian Constitution through its directive principles

provides the basis for the Right to health care, and

the Indian state has ratified the International

Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

which makes it obligatory on its part to comply

with Article 12 that mandates right to healthcare.

Universal access to healthcare is well established

in a number of countries including not only

developed countries like Canada and United

Kingdom. but also developing countries such as

Cuba. Brazil. Costa Rica and Thailand. There is

no reason why this cannot be made a reality in

India. Hence we need to set in motion processes.

which will take us towards the goal of universal

access to health care, in a Rights-based framework

and with equity.

Some immediate steps related to the health care

system that need to be taken include:

Making healthcare a fundamental right by

suitable constitutional amendment. The

formulation of a National legislation

mandating the Right to Health care, with a

clearly defined comprehensive package of

health care, along with authorization of the

requisite budget, being made available

universally within one year.

■ Significant strengthening of the existing

public health system, especially in rural

areas, by assuring that all the required

infrastructure, staff, equipment, medicines

and other critical inputs are available, and

result in delivery of all required services.

These would be ensured based on clearly

defined, publicly displayed and monitored

norms.

• The declining trend of budgetary allocations

for public health needs to be reversed, and

budgets appropriately up-scaled to make

optimai provision of health care in the

public domain possible. At one level adopting

a fiscal policy of block funding or a system

of per capita allocation of resources to

different levels of health care, with an

emphasis on Primary Health Care will have

an immediate impact in reducing ruralurban inequities by making larger

resources available to rural health facilities

like Primary health centers and Rural

hospitals. Simultaneously, the budgetaryallocation to the heaith sector must be

.

6

policies similar to what has been done by

the Tamilnadu State Medical Services

Corporation and hence ensure that

essential drugs in the list are actually

available in every facility.

i he state should introduce a new

community-anchored health worker

scheme, and implement it in a phased

manner with involvement of people’s

organizations and panchayati raj

institutions, in both rural and urban areas,

through which first contact primary' care

and health education can be ensured.

Integration of medical education of all

systems to create a basic doctor ensuring

•

•

a wider outreach and improvement ot

access to health care services in all areas.

All state level coercive population control

policies, disincentives and orders should

be revoked. Disproportionate financial

allocation for population control activity

should not be allowed to skew funding from

other important public health priorities.

Integration of medical education of all.

systems to create a basic doctor ensuring

a wider outreach and improvement ot

access to health care services in all areas.

Effective regulation of the growth of

capitation based medical colleges.

Conclusion:

What is needed is a major restructuring and

strengthening of the health system. This involves

two major ingredients: popular mobilisation for

operationalising the Right to Health Care, and the

political will to implement policy changes

necessary to transform the health system. Jan

Swasthya Abhiyan is today involved in the former

task, by reaching out to people across the country.

enabling them to mobilise for their just health

rights. It calls upon political parties, which

recognise people's right to healthy lives, to address

the latter task, and to perform their historic duty

by establishing and operationalising the Right to

Health care as a Fundamental right.

The persistence of unacceptably large numbers of

avoidable deaths, resurgence of communicable

diseases, declining quality of public health services

and unaffordable, often inappropriate private

^edical care need not remain the lot of over a

Wilion ordinary Indians. Recent policy changes of

privatisation, declining public health budgets and

pro-drug industry measures need to be replaced by

strong public health initiatives, with the active

involvement of communities and civil society

organisations.

By and large. India today possesses the

humanpower, infrastructure, national financial

resources and appropriate health care know-how

to ensure quality health care for all its citizens.

This document focuses on the need for strengthening of the health care system, and certain immediate

steps required for this However, improvement of people's health requires equally importantly, provision

of other necessaiy facilities and conditions required for a healthy life, such as safe drinking water.

sanitation, food security, healthy housing, basic education and a safe environment. The People’s Health

Charter has dealt with these issues, and may be taken as a guideline tc develop effective policies and

improve people's living standard in order to achieve better health.

Published by CEHAT for JAN SWASTHYA ABHIYAN

7

Indian People’s Health Charter

> r?A /.■>■ •■

r^V. e - :cfr-

1 r. -;.

.

• -

■

■ ■

We the people of India, stand united in our condemnation of an iniquitous global system that, under the garb of

•Globalisation’ seeks to heap unprecedented misery and destitution on the overwhelming majority of the people on

this globe. This system has systematically ravaged the economies of poor nations in order to extract profits that

nurture a handful of powerful nations and corporations. The poor, across the globe, as well as the sections of poor

m the rich nations, are being further marginalised as they are displaced from home and hearth and alienated from

their sources of livelihood as a result of the forces unleashed by this system. Standing in firm opposition to such a

system we reaffirm our inalienable right to and demand for comprehensive health care that includes food security:

sustainable livelihood options including secure employment opportunities; access to housing, drinking water and

sanitation; and appropriate medical care for all; in sum - the right to Health For All, Now!

The promises made to us by the international community in the Alma Ata declaration have been systematically

repudiated by the World Bank, the IMF, the WTO and its'predecessors, the World Health Organization, and by a

government that functions under the dictates of International Finance Capital. The forces ‘Globalisation’ through

measures such as the structural adjustment programme are targeting our resources - built up with our labour.

sweat and lives over the last fifty years - and placing them in the service of the global “market' for extraction of

super-profits. The benefits of the public sector health care institutions, the public distribution system and other

infrastructure - such as they were - have been taken awav from us. It is the ultimate irony that we are now blamed

fcr our plight, with the argument that it is our numbers and our propensity to multiply that is responsible for our

poverty and deprivation. We declare health as a justiciable right and demand the provision of comprehensive health

care as a fundamental constitutional right of every one of us. We assert our right to take control of our health in our

own hands and for this the right to;

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

A truly decentralized system of local governance vested with adequate power and responsibilities, provided with

adequate finances and responsibility for local level planning.

A sustainable system of agriculture based on the principle of land to the tiller - both men and women - equitable

distribution of land and water, linked to a decentralized public distribution system that ensures that i^ine

goes hungry

universal access to education, adequate and safe drinking water, and housing and sanitation facilities

A dignified and sustainable livelihood

A clean and sustainable environment

A. drug industry geared to producing epidemiological essential drugs at affordable cost

A health care system which is gender sensitive and responsive to the people’s needs anc whose control is

vested in people’s hands and not based on market defined concept of health care.

Further, we declare our firm opposition to:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

>

"

<

Agricultural policies attuned to the needs of the 'market’ that ignore disaggregated and equitaoie access to food

Destruction of our means to livelihood and appropriation, for private profit, of our natural resource bases and

appropriation of bio-diversity

The conversion of Health to the mere provision of medical facilities and care that are technology' intensive.

expensive, and accessible to a select few

The retreat, by the government, from the principle of providing free medical care, through reduction of public

sector expenditure on medical care and introduction of user fees in public sector medical institutions, that

place an unacceptable burden on the poor

The corporatization and commericializarion of medical care, state subsidies to the corporate sector in medical

care, and corporate sector health insurance

Coercive population control and promotion of hazardous contraceptive technology which are directed primarily

ar the poor and women

The use of patent regimes to steal our traditional knowledge and to put medical technology- and drugs Mtond

our reach

institutionalization of divisive and oppressive forces in society, such as communalism, caste, patriarchy, and

me attendant violence, yvhich have destroyed our peace and fragmented our solidarity.

.-. the light of the above we demand that:

1

The concept of comprehensive primary' health care, as envisioned in the Alma Ata Declaration should form the

fundamental basis for formulation of all policies related to health care. The trend towards fragmentation of

health delivery- programmes through conduct of a number of vertical programmes should be reversed. National

health programmes be integrated within the Primary- Health Care system with decentralized manning, decision

making and implementation with the active participation of the community. Focus be shifted from bio-medicai

and individual based measures to social, ecological and community based measures.

The primary health care institutions including trained village health workers, sub-centers, and the PHCs staffed

by doctors and the entire range of community health functionaries including the ICDS yvorkers. be placed under

me direct administrative and financial control of the relevant level Panchayati Raj institutions. The overall

infrastructure of the primary health care institutions be under the control of Panchayats and Gram Sabhas and

provision of free and accessible secondary and tertiary level care be under the control of Zilia Panshads, to be

accessed primarily through referrals from PHCs.

The essential components of primary' care should be:

. Village level health care based on Village Health Workers selected by the community and supported by

the Gram Sabha / Panchayat and the Government health services yvhich are given regulatory powers

and adequate resource support

S

•

•

•

•

o.

Primary Health Centers and sub-centers with adequate staff and supplies which provides quality curative

services at the primary health center level itself with good support from referral linkages

A comprehensive structure for Primary Health Care in urban areas based on urban PHCs, hqalth posts

and Community Health Workers under the control of local self government such as ward committees

and municipalities.

Enhanced content of Primary Health Care to include all measures which can be provided at the PHC

level even for less common or non-communicable diseases (e.g. epilepsy, hypertension, arthritis, preeciampsia. skin diseases) and integrated relevant epidemiological and preventive measures

Surveillance centers at block level to monitor rhe local epidemiological situation and tertiary care with

ail speciality services, available in every district.

A comprehensive medical care programme financed by the government to the extent of at least 5% of our GNP,

o: wnich at least half be disbursed to panchayau raj institutions to finance primary level care. This be accompanied

oy transfer of responsibilities to PRIs to run major parts of such a programme, along with measures to enhance

capacities of PRIs to undertake the tasks involved.

the policy of gradual privatisation of government medical institutions, through mechanisms such as introduction

oi user fees even for the poor, allowing private practice by Government Doctors, giving out PHCs on contract,

etc. be abandoned forthwith. Failure to provide appropriate medical care to a citizen by public health care

institutions be made punishable by law.

o.

.-. comprehensive need-based human-power plan for the health sector be formulated that addresses the requirement

:or creation of a much larger pool of paramedical functionaries and basic doctors, in place of the present trend

towards over-production of personnel trained in super-specialities. Major portions of undergraduate medical

ecucation. nursing as well as other paramedical training be imparted in district level medical care institutions,

as a necessary complement to training provided in medical/nursing colleges and other training insututions. No

more new medical colleges to be opened in the pnvate sector. No commodification of medical education. Steps

to eliminate illegal pnvate tuition by teachers in medical colleges. At least a year of compulsory rural posting for

undergraduate imedical, nursing and paramedical) education be made mandatory, without which license to

practice not be issued. Similarly, three years of rural posting after post graduation be made compulsory.

6.

Ti'.e unbridled and unchecked growth of the commercial pnvate sector be brought to a halt. Stnct observance of

standard guiaeiines for medical and surgical intervention and use of diagnostics, standard fee structure, and

periodic prescnption audit to be made obligatory. Legal and social mechanisms be set up to ensure observance

of minimum standards by ail pnvate hospitals, nursing/matemity homes and medical laboratones. Prevalent

practice oi offering commissions for referral to be made punishable by law. For this purpose a body with statutory

powers be constituted, which has due representation from peoples organisations and professional organisations.

7

A rational drug policy be formulated that ensures development and growth of a self-reliant industry for production

of ail essential drugs at affordable prices and of proper quality. The policy should, on a. priority basis:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

8

•ij

Ban ail irrational and hazardous drugs. Set up effective mechanisms to control the introduction of new

drugs and formulations as well as periodic review of currently approved drugs.

Introduce production quotas & price ceiling for essential drugs

Promote compulsory use of generic names

Regulate advertisements, promotion and marketing of all medications based on ethical cntena

Formulate guidelines for use of old and new vaccines

Control the activities of the multinational sector and restrict their presence only to areas where they

are willing to bnng in new technology

Recommend repeal of the new patent act and bnng back mechanisms that prevent creauon of monopolies

and promote introduction of new drugs at affordable pnces

Promotion of the public sector in production of drugs and medical supplies, moving towards complete

self-reliance in these areas.

Medical Research prionties be based on morbidity and mortality profile of the country, and details regarding the

direction, intent and focus of all research programmes be made entirely transparent. Adequate government

funding be provided for such programmes. Ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects be drawn up

and implemented after an open public debate. No further experimentation, involving human subjects, be allowed

without a proper and legally tenable informed consent and appropriate legal protection. Failure to do so to be

cunisnabie by .aw. All unethical research, especially in the area of contraceptive research, be stooped forthwith.

men ianc mem who. without their consent and knowledge, have been subjected to experimentation, especially

wit.n nazarcous contraceptive technologies to be traced forthwith and appropriately compensated. Exemplary

carnages to oe awarded against the institutions (public and pnvate sector) involved in such anti-people, unethical

una illegal oractices in the past.

All . aercive measures including incentives and disincentives for limiting family size be abolished. The right of

famines anc women within families in determining the numoer of children they want should be recognized.

Concurrently. access to safe and affordable contraceptive measures be ensured which provides people, especially

me:'., the ..miity to make an informed choice. All long-term, invasive, systemic hazardous contraceptive

• c.-:inogies such as the mjectables (NET-EN, Depo-Provera. etc.), sub-dermal implants iNorplanti and'anti

■.

.tv -.accmes shouid be banned from both the public and private sector. Urgent measure be initiated to shift

• . tins of contraception away from women and ensure at least equal emphasis on men's responsibility for

■n:.-.:ception. Facilities for safe abortions be provided nght from the primary health center level.

'..court be crovided to traditional healing systems, including, local and home-based healing traditions, for

svsiematic research .and community based evaluation with a view to developing the knowledge base and use of

■ -,ese svstems Mong with modern medicine as part of a holistic healing perspective.

9

11.

Promotion of transparency and decentralization in the decision making process, related to health care, at all

levels as well as adherence to the pnnciple of right to information. Changes in health policies to be made only

after mandatory' wider scientific public debate.

*

12.

Introduction of ecological and social measures to check resurgence of communicable diseases. Such measures

should include:

.

.

.

Integration of health impact assessment into all development projects

Decentralized and effective surveillance and compulsorv notification of prevalent diseases like malaria,

TB by all health care providers, including private practitioners

Reonentation of measures to check STDs,/AIDS through universal sex education, promoting responsible

safe sex practices, questioning forced disruption and displacement and the culture of commodification

of sex. generating public awareness to remove stigma and universal availability of preventive and curative

services, and special attention to empowering women and availability of gender sensitive services in

this regard.

13.

Facilities for early detection and treatment of non-communicable diseases like diabetes, cancers, heart diseases,

etc. to be available to all at appropnate levels of medical care.

14.

Women-centered health initiatives that include:

.

.

.

•

15.

Child centered health initiatives that include:

.

.

•

.

16.

Awareness generation for social change on issues of gender and health, triple work burden, gender

discrimination tn upbringing and life conditions within and outside the family, preventive and curative

measures to deal with nealth consequences of women's work and violence against women

Complete maternity benefits and child care facilities to be provided in all occupations employing women,

be they in the organized or unorganized sector

Special support structures that focus on single, deserted, widowed women and minority women which

will include religious, ethnic and women with a different sexual orientation and commercial sex workers;

gender sensitive services to deal with all the health problems of women including reproductive health,

maternal health, abortion, and infertility

Vigorous public campaign accompanied by legal and administrative action against sex selective a'oo^Bns

including female feticide, infanticide and sex pre-selection.

A comprehensive child rights code, adequate budgetary allocation for universalisation of child care

services

An expanded & revitalized 1CDS programme. Ensuring adequate support to working women to facilitate

child care, especially oreast feeding

Comorehensive measures to prevent child abuse, sexual abuse and child prostitution

Educational, economic and legal measures to eradicate child labour, accompanied by measures to ensure

free and compulsory quality elementary education for all children.

Special measures relating to occupational and environmental health which focus on:

.

•

•

.

Banning of hazardous technologies in industry and agriculture

Worker centered monitoring of working conditions with the onus of ensuring a safe and secure workplace

on the management

Reorienting medical services for early detecuon of occupational disease

Special measures to reduce the likelihood of accidents and injuries in different settings, such as traffic

accidents, industrial accidents, agricultural injuries, etc.

17.

The approacn to mental health problems should take into account the social structure in India which makes

certain sections like women more vulnerable to mental health problems. Mental Health Measures that procure

a shift away from a bio-medical model towards a holistic model of mental health. Community support 8s ccmm^Jty

based management of mental health problems be promoted. Services for early detection os integrated management

of mental health problems be integrated with Primary Health Care and the rights of the mentally ill and the

mentally challenged persons to be sale guarded.

18.

Measures to promote the health of the elderly by ensuring economic security, opportunities for appropnate

employment, sensitive health care facilities and, when necessary, shelter for the elderiv. Services that cater to

the special needs of people in transit, the homeless, migratory workers and temporary settlement dwellers.

19.

Measures to promote the health of physically and mentally disadvantaged by focussing on the abilities rather

than deficiencies. Promotion of measures to integrate them in the community with special support rather than

segregating them; ensuring equitable opportunities for education, employment and special health care including

rehabilitative measures.

20.

Effective restriction on industries that promote addictions and an unhealthy lifestyle, like tobacco, alcohol, pan

masala etc., starting with an immediate ban on advertising, sponsorship and sale of their products to the

young, and provision of services for de-addiction

10

Constituents/of theJADFSWASTHYAABHIYAN

Fhe uan Swasthya Abhiyan at the national level is the coalition of the networks of voluntary organizations

and peoples movements involved in healthcare deliver.- and health policy, who made themselves a part of

ihe Peoples Health Assembly campaign in India in the year 2000, and have continued to participate in this

process. These national networks have numerous constituent organisations, which implies that a tew

hundred organizations are involved directly in the national process. Beyond these networks, several hundred

other organizations have been involved at state, district and block level activities across the country. The

networks that constitute the National Coordination Committee of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan are:

-•

3.

-.

=•

o.

S.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

I-.

15.

16.

17

IS.

19.

20.

21.

All India Peoples Science Network

All India Democratic Women’s Association

All India Drug Action Network

Asian Community Health Action Network

Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti

Catholic Health Association of India (CHAI)

Chrisuan Medical Association of India (CMAI)

Federation of Medical Representatives and Sales Associations of India (FMRAI)

Forum for Creche and Child Care Services (FORCES)

Joint Women’s Programme

Medico Friends Circle (MFC)

National .Alliance of People's Movements (NAPM)

National Alliance of Women’s Organisations (NAWO)

National Federation of Indian Women (NFIW)

Ramakrishna Mission

Voluntary Health Association of India (VHAI)

Association for Indian Development, India (AID-India)

Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India (BFPNI) National Resource Groups:

Centre for Ena.uiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT)

Centre for Social xMedicine and Community' Health, Jawaharlal Nehru University

Community Health Cell (CHC)

ihe representatives of ail the above organisations constitute the National Coordination Committee of JSA.

which is the national decision making body of the coalition. N.H. Antia is the Chairperson and D. Banerjee

bs the Vice-Chairperson of JSA. National organisers of JSA include B. Ekbal as Convenor, Abhay Shukia.

Amit Sengupta, Amitava Guha, Thelma Narayan and T. Sundararaman as Joint convenors, with Vanaana

Prasad and N.B.Sarojini as National secretariat members.

Jan Swasthya Abhiyan presently has state units or contacts in the following states:

Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh,

Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Rajasthan, Tamil

Nadu. Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal.

11

B. Ekbal,

National Convenor, JSA

Abhay Shukla

National Secretariat, JSA

Amit Sen Gupta

Jt. Convenor, JSA

Ph: 0471-2306634(0)

e. 2, j. ekbaLh~vsnI.com

Ph: 020-25451413 / 25452325

e-mail cehatounf2vsnl.com

Ph: 011-26862716/ 26524324

e-mail: ctddsEtZvsnl.com

Amitava Guha

Jt. Convenor, JSA

Thelma Narayan

Jt. Convenor, JSA

T. Sundararaman

Jt. Convenor, JSA

Ph: 033-24242862(0)

e-mail:

guhaamitava 2hotmail.com

Ph:080-5505924 / 5525372

e.mai]: socharaftZvsnl.com

Phone: 0771-2236104. 2236175

e-mail:

sunaar'2@ 123india.com

Sarojini

Member, National Secretariat

Vandana Prasad

Member, National Secretariat

Ph: 011-26968972 / 26850074

e-maii: samasaro@vsnl.com

Phone: 0120-2536578

e-mail: chaukhat@vahoo.com

SRS Bulletin. Government of India.1998

Planning Commission. Government of India. Tenth Five Year Plan 2002-2007. Volume II.

international Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro. National Family Health Surrey (NFHSII) 1998-99. India.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. RCH-RHS India 1998-1999.

5. National Crime Records Bureau. Ministry of Home Affairs. Accidental Deaths and Suicides In India

2000.

6. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2003.

7 International Institute for Population Sciences. Facility Survey. 1999.

8. Misra. Chatterjee, Rao. India Health Report.Oxford University Press. New Delhi.2003

9. Morbidity and Treatment of Ailments. NSS Fifty' second round. Government of India. 1998.

10. Changing the Indian Heaith System - Draft Report, ICRIER. 2001

11. Shanff Abusaleh. India Human Development Report.Oxford University Press New Delhi.

12. Duggal.Ravi. Operationalizing Right to Healthcare in India. Right to Healthcare, Moving from Idea to

Reality.

CEHAT Mumbai.2003.

13. National Coordination Committee for the Jana Swasthya Sabha. Health for All NOW. 2004.

14. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence.Directorate General of Health Services. Ministry/ of Health and

Family Welfare. Health Information of India 2000 &2001.

15. National Sample Survey Organization. Department of Statistics.GOI.42nd and 52nd Round.

16. Census of India 2001: Provisional Population Totals.Registrar General and Census Commissioner GOI.

17. Pai M et al. A high rate of Cesaerean sections in affluent section of Chennai, is it a cause for concern?

Nat Med J India. 1999.12:156-158.

18. TB India 2003. RNTCP Stats Report.Central TB Division.DDHS GOI.

19. Heaith Survey and Development Committee. GOI 1946 (Bhore Report)

20 Mahal A www-woridbank.org

21. Phadke A. Drug Supply and Use. Towards a Rational Policy in India. Sage Publications New Delhi.

22. Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers.

1.

2.

3.

12

PROPOSAL FOR HEALTH CENTRES & MATERNITY HOSPITALS UNDER

LP.P.-VIII BANGALORE EXTENDING THE PROJECT TO 11 CITIES OF

KARNATAKA STATE.

A.

INTRODUCTION

The proposed Project is an extension of India Population Project-VEH, Bangalore,

to other Cities of Karnataka State. IPP-VIU is an IDA assisted Project. It provides IDA

with the opportunity to extend rapid but targeted assistance to the most vulnerable groups

through an agency which is already implementing the Project satisfactorily.

The special features of the Project are that:

a)

To assist the Govt, of India (GOI) in expanding the coverage of Family

Welfare (FW) and Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) services to

previously unserved urban slums.

b)

To act as a vehicle to improve the quality of services to be delivered to the

urban poor.

c)

Increase the demand for family welfare services by substantially

improving the participation of Private Voluntary Organisations and

Communities in the design, delivery and supervision of family welfare

services to be delivered to the slum communities by IEQ activities.

d)

Institute Innovative Scheme, under which investments in Female

Education and Vocation training, nutrition, awareness, environmental

sanitation through community participation, would be supported.

e)

In all 11 Cities, Health Centres are proposed on the basis of one Health

Centre for 50,000 population. Out of the 50,000 population around 20-30

thousand are expected to utilise the Health Centres facilities. In the case

of Hubli-Dharwad and Bhadravathi, the number of Health Centres

proposed is on the basis of one Health Centre for 40 thousand populations.

This is because the population is scattered and will not avail the health

facility if the distance is more than 3-5 K.M. from their residence.

,

..2..

g

GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

The goals set for various indicators under the National Health & Family Welfare

Programmes for the year 2000 to be attained in the Project Area are follows:

1.

Infant Mortality Rate

<60

2.

Perinatal Mortality Rate

<30-35

3.

Pre-school child mortality (1-5 years)

< 10

4.

Maternal Mortality Rate

<2

5.

Crude Birth Rate

<21

6.

Crude Death Rate

<9

7.

Effective Couple Protection Rate<%)

>60

8.

Pregnant Mothers receiving Antenatal Care 100%

9.

Immunisation Status (%)

a) TT for pregnant women

b) TT for school children

c) DPT (children 3 years)

d) Polio (infants)

e) BCG (infants)

100

100

85

85

85

Institutional deliveries (%)

95

10.

As per the National Health Policy, the services would be taken nearer to the door

steps of the people ensuring full participation of the community in the process of Health

Development.

..3..

The specific objectives of the project are to:

a) Improve maternal and child health, and

b) Reduce the fertility among the urban poor.

These objectives would be achieved by undertaking activities in five broad areas:

a)

Expanding service delivery to slum populations through improvements in

outreach services using volunteer female health workers selected from slum

communities, and upgrading of existing and construction of new health

facilities.

b)

Improving the quality of family welfare services provided to slum

populations, by upgrading the supervisory, managerial, technical and inter

personal skills at all levels of new and existing medical and para-medical

workers through pre-service, institutional in-service and on-the-job-recurrent

training; and increasing the availability of drugs, medicines and other

appropriate health supplies.

c)

Increasing the demand for family welfare services

through an expanded

programme of information, education and communication (DEC); increased

participation of the slum community through their representatives and groups

in the preparation and implementation of various project.

..4..

activities and the increased participation of Private Voluntary Organisations

and Private Medical Practitioners in the delivery of family welfare services to

slum communities.

d)

Strengthening the management and administration

of municipal Health

Departments through appropriate upgrading of Management Information

Systems (MIS), EEC, training, civil works, and audit and accounting functions,

as well as integrating and/or strengthening co-ordination of health services with

the provision of environmental sanitation and water supply services.

e)

Supporting Innovative Schemes which cover a range of additional services

including supplementary nutrition, creche programs, environmental sanitation

drives, education jind skill training programme for females, especially

adolescent girls, Non - Formal School and RCH interventions.

C.

Services to be delivered

Promotive and preventive health services specifically family welfare and maternal

and child care services would be delivered to the urban poor through a network of Health

Centres / Referral Health Centres of the Municipal Corporation.

..5..

The services planned to be provided by the Maternity Hospitals and Health Centres are listed

below:

Health Centre

Maternity Hospital

Health & Nutrition Education

Yes

No

Knowledge of vaccine

preventable diseases &

diarrhoea

Yes

No

Family Planning

Yes

Yes

Antenatal Care

Yes

Yes

Normal Deliveries

No

Yes

High Risk Deliveries

No

Post Natal Care

Yes

Yes

Immunisation of Mother & Child

Yes

Yes

Nutritional Care of children

upto the age of five

Yes

No

Medical check-up and followUp of school-going children

Yes

No

Treatment for minor ailments

Yes

Yes

Nor surgical care for children

needing specialist attention

No

Yes

Minor gynaecological procedures

No

Yes

Laboratory Tests: Basic

No

Yes

Service.

Promotive

Health Care

refered to major hospitals

..6..

Family Planning

Counselling and advice on appropriate

method

Yes

Yes

Supply of Condom/Oral Pill

Initial

Subsequent

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Check up & insertion of IUD

Yes

Yes

Sterilization

No

Yes

M.T.P

Yes

Yes

Domicilliary follow-up of

Acceptors

Yes

No

The Health Centre will refer to the Maternity Homes pregnancies and cases

requiring gynaecological procedures, sterilization and M.T.P and attention by

Paediatrician.

The Maternity Hospital, in tum, will direct cases with major complications

requiring surgical intervention such as Caesarean Section, children with congenital

abnormalities to appropriate hospitals.

New Health Centres and renovation of existing centres is also part of the proposed

project. Actions will be initiated after rapid low cost base line survey by consultants.

D.

The Outreach Programme.

The Outreach Programme will be operated by each Health Centre with three

ANMs and ten Link Workers. The Link Workers will be selected from the slum dwellers

and will report to ANMs. They will be given requisite training by the specifically trained

Officer under I.P.P. - VIII. They will be paid a monthly honorarium of Rs.500/-.

..7..

The job responsibilities of the outreach workers are:

LHV

ANMS

Link Workers

1.

Detection of Antenatal cases

Yes

Yes

Yes

2.

Regn. of Antenatal cases

Yes

Yes

No

3.

Antenatal Care & Post Natal Care

Yes

Yes

Yes

4.

Immunization

Yes

Yes

No

5.

First aid services for mothers

and children

Yes

Yes

No

6.

Health Education

Yes

Yes

Yes

7.

Nutrition Education

Yes

Yes

Yes

8.

Motivation of cases for FP

Yes

Yes

Yes

9.

Depot Holders for Condoms,

Oral Pills and ORS Packets

Yes

Yes

Yes

10.

Supervision & Training of

Link Workers

Yes

Yes

11.

Referral to next level

H.C.

H.C.

ANM

12.

I.E.C. activity

Yes

Yes

Yes

The'outreach programme will provide different MCH & FW services according to

predetermined schedule at places in/or close to slums such as anganwadis, community

hails or other places owned by the Corporation/CMC.

The additional recurrent cost of the outreach programme is to be estimated.

..8..

E.

STAFF PROPOSED FOR A HEALTH CENTRE

1)

2)

3)

4)

F.

Lady Medical Officer

Lady Health Visitor

Auxiliary Nurse Midwife

Link Workers

-

1

1

3

10

JOB FUNCTIONS OF FIELD STAFF

The field staff will conduct Eligible Couple Survey in their allotted population.

The L.H.V. will have a population of 5000 in addition to supervision of the work of

A.N.M.s and Link Workers. Each A.N.M. will have a populatioon of 15,000. Each

Link worker will cater to a population of 5000.

They will prioritize the Eligible Couples according to the parity and age for F.W

Coverage.

They will register 100% Ante natal cases preferably in the first trimester.

They will ensure 100% immunisation of all pregnant, mothers and infants in

their juridiction

They will assist the Anemia Control Programme through distribution of FS

Adult and Children tablets.

They will ensure small and healthy family by acceptance of O.P.CC, IUD and

sterlization in their area.

They will conduct outreach programmes such as Antenatal immunization clinics,

awamess programmes, well baby show, clean hut competition. Health Check up Camps

in the slums.

They will identify innovative schcmes( to be conducted through NGOs), like

Creches Non Formal School, Vocational Training, Male Participation in H & FW

Programme.

The Health Centre Staff will identify and select Link workersf Selection Criteria

enclosed Annexure) They will conduct the relevant I.E.C. activities to create demand for

the FW & MCH programmes.

JOB FUNCTIONS OF THE LMO

She will be the overall responsible for effective implementation of FW & MCH,

RCH activities etc in the jurisdiction of the Health Centre to achieve the goals and

objectives. She will submit the periodical reports as per the norms.

G.

H.

EQUIPMENT /FURNITURE /DRUGS/ CONSUMABLES

Procurement of necessary modem equipments and replacement of unserviceable

equipments is proposed for all New Health Centres and existing U.F.W.C.s. Similarly

furniture will also be provided for New Health Centre and existing U.F.W.Cs. Drugs

and consumables is also to be provided for all New Health Centres. Partial support of

drugs will be provided for the existing U.F.W.Cs. (Details are given in Annexure)

H.

CIVIL WORKS

New Health Centre construction is proposed in all the 11 cities. The centres will

be located as close 'as possible to the slums . Building Plans approved for IPP-VIII

Bangalore will be utilised for the cities where Maternity Homes / Health Centres is

proposed. The tenders for all works will be advertised in National newspapers (NCB)

by EPP-VUI Office Bangalore. Thereafter evaluation will be done at the project office in

Bangalore, by for technical and financial bids.

One representative from each City will be a member of the evaluation committee,

where the lowest evaluated responsive bidder will be awarded the work order from the

Central Project Office IPP-VIII Bangalore. Supervision of work will be done by the

Engineering Department of the beneficiary City. Payment of bills will be made by

Project Co-ordinator IPP-VIII Bangalore after receipt of bills duly certified by concerned

CMCs & Corporation Commissioner. M/s. TOR Steel Research Foundation India who

are already appointed for quality control will be authorised to function as consultant for

quality control at five stages of civil construction for the beneficiary cities. Health Centre

Type design A,B & C, and type design for 12 bed maternity home is shown in annexure

will be utilised based on the availability of sites/area.

J.

TRAINING

All Medical, Paramedical Staff of Maternity Homes/ U.F.W.C.s/Health Centre., are to be

trained in the aims and objectives of I.P.P. - VIII also the implementation of programme.

The training will be taken up by the IPP-VIII Training Centre at Kodandaramapura,

Bangalore. For training Link Workers, each city will identity three persons (trainers)

who will be trained at Bangalore. Thereafter for Link Workers, training will be done at

the city level by these trained trainers.

The areas in which training is to be provided are:

1.

Management Development, Planning, Programming.

2.

NGO participation strategies.

..10..

3.

Monitoring & Supervision

4.

Communication, Motivation, and providing quality care.

5.

Clinical Update

6.

Health Care & FW Update

7.

Promotive and preventive Health Care & Family Welfare.

8.

Re-orientation practical training for Laboratory Technicians

9.

Maintenance of Stock Records & Collection & submission of periodical

reports.

10.

Orientation on Extension Approach, field training.

11.

Male Participation.

12.

Training Methodology

The training centre will be utilised for the training programmes. The cost of

training will be met out of the budget allocated to individual cities.

K.

I.E.C.

One community development officer is proposed for each city to co-ordinate,

I.

E.C.

and Women Development activities. Materials already produced by the IPP-VUI

Bangalore will be made available to all the cities. Budgetary provision is made to prepare