UNF/UNFIP PROJECT DOCUMENT

Item

- Title

- UNF/UNFIP PROJECT DOCUMENT

- extracted text

-

RF_COM_H_54_SUDHA

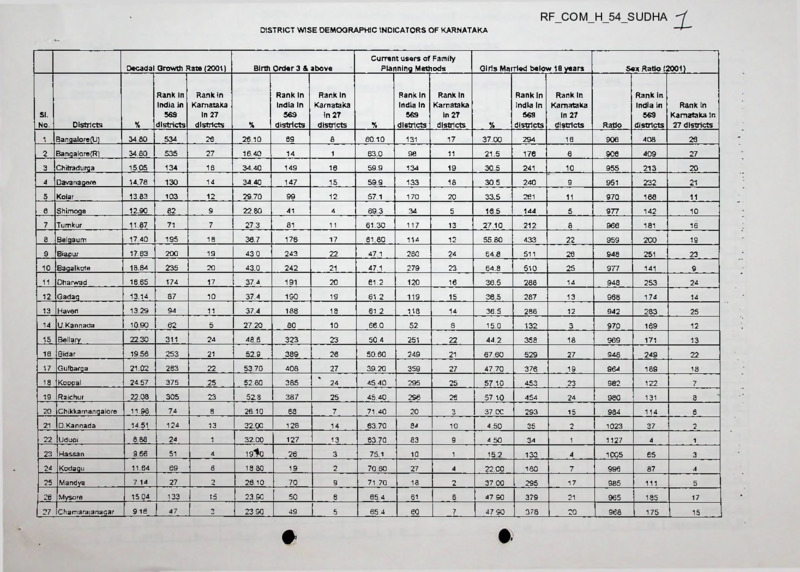

DISTRICT WISE DEMOGRAPHIC INDICATORS OF KARNATAKA

Decadal Growth Rate (2001)

Rank In

Rank In

India In Karnataka

569

In 27

districts districts

Current users of Family

Planning Methods

Birth Order 3 & above

Rank in

Rank In

India In Karnataka

569

In 27

districts districts

Girls Married below 18 years

Sex Ratio (2001)

Rank In

Karnataka

In 27

districts

Ratio

SI.

No.

Districts

%

Rank In

India In

569

districts

%

Rank In

India In

569

districts

1

Bangalore(U)

34 80

534

26

26 10

69

8

60.10

131

17

37.00

294

16

906

408

26

2

Bangalore (R)

34.80

535

27

16.40

14

1

63.0

98

11

21.5

176

6

906

409

27

3

Chitradurga

15.05

134

16

34.40

149

16

59.9

134

19

30 5

241

10

955

213

20

4

Davanagere

14.78

130

14

34.40

147

15

59 9

133

18

30.5

240

9

951

232

21

5

Kolar

13.83

103

12

29 70

99

12

57.1

170

20

33.5

261

11

970

168

11

6

Shimoga

12.90

82

9

22.80

41

4

693

34

5

165

144

5

977

142

10

7

Tumkur

11.87

71

7

27 3

81

11

61.30

117

13

27.10

212

8

966

181

16

8

Belgaum

17 40

195

18

36.7

176

17

61.80

114

12

55.80

433

22

959

2C0

19

9

Biapur

17.63

200

19

43.0

243

22

47.1

280

24

64 8

511

26

948

251

23

10 Bagalkote

18.84

235

20

43.0

242

21

47.1

279

23

64.8

510

25

977

141

9

Dharwad

16.65

174

17

37.4

191

20

61.2

120

16

36.5

288

14

948

253

24

12 Gadaq

13.14

87

10

37.4

190

19

61.2

119

15

365

287

13

968

174

14

13 Haven

13.29

94

11

37.4

188

18

61 2

118

14

36.5

286

12

942

283

25

10.90

62

5

27 20

80

10

66.0

52

6

150

132

3

970

169

12

15 Bellary

22 30

311

24

48 6

323

23

50 4

251

22

44.2

358

18

969

171

13

16 Bidar

19 56

253

21

52.9

389

26

50.60

249

21

67 60

529

27

948

249

22

17 Gulbarga

21.02

283

22

53 70

408

27

39.20

359

27

47 70

376

19

964

189

18

18 Koopal

24.57

375

25

52.80

385

24

45 40

295

25

57 10

453

23

982

122

7

19 Raichur

22.08

305

23

52.8

387

25

45.40

296

26

57 10

454

24

980

131

8

20 Chikkamangalore

11 98

74

8

26.10

68

7

71.40

20

Q

37 00

293

15

984

114

6

D. Kannada

14.51

124

13

32.00

128

14

63.70

84

10

4 50

35

2

1023

37

2

22 Udupi

6.88

24

1

32.00

127

13

63 70

83

9

4 50

34

1

1127

4

1

23 Hassan

9 66

51

4

19^0

26

3

75.1

10

1

152

133

4

1005

65

3

24 Kodagu

11.64

69

6

18.80

19

2

70 60

27

4

22. CO

180

7

996

87

4

25 Mandya

7 14

27

2

26.10

70

9

71 70

18

2

37 CO

295

17

985

111

5

26 Mysore

15 04

133

15

23 90

50

6

65 4

61

8

47 90

379

21

965

185

17

27 Chamaraianagar

9 16

47

3

23 90

49

5

65 4

60

7

47 90

378

20

968

175

15

11

14

21

U. Kannada

%

Rank In

Karnataka

In 27

districts

%

Rank in

India In

Rank In

Karnataka In

569

districts 27 districts

DISTRICT WISE DEMOGRAPHIC INDICATORS OF KARNATAKA

Complete Immunisation

Safe Delivery

Rank in

Karnataka

in 27

districts

Female Literacy Rate (2001)

Villages not connected with

pucca road (2000-01)

Estimated Coverage of safe

drinking water (2000)

SI.

No.

Districts

%

Rank in

India in

569

districts

%

Rank in

India in

569

districts

•/.

Rank In

India In

563

districts

1

Banaalore(LT)

90.60

41

3

77.70

139

16

78.98

29

1

0.00

64

11

67.56

320

8

2

BangalorefRI

79 10

92

7

83 70

96

14

78 98

30

2

0 00

65

12

71.30

288

4

3

Chitradurga

53 80

233

21

88.40

65

9

54.62

261

15

0.00

58

10

72.62

281

3

4

Davanaaere

53 80

231

20

88 40

63

8

58 45

209

11

0.00

26-

3

72 62

280

2

5

Kolar

59.20

202

18

90 60

48

6

52.61

289

16

23 10

208

27

74 00

275

1

6

Shimoga

83 00

70

5

92.90

30

2

67 24

111

7

4 67

134

21

54.60

437

18

7

Tumkur

63.50

183

16

88.00

66

10

57.18

226

13

21.47

201

26

66.59

335

12

8

Belaaum

68 60

150

12

64 80

226

20

52.53

296

18

0.00

42

6

52 94

452

21

9

Biaour

50 10

253

24

53 20

315

22

46 19

360

21

0 00

20

2

60 42

402

15

10

Bagalkote

50.10

252

23

53.20

314

21

44.10

404

23

0.00

7

1

60.42

401

14

11

Dharwad

65.30

172

15

74.80

162

19

62 20

157

9

0 00

55

9

67 18

328

11

12

Gadaa

65 30

170

14

74 80

161

18

52.58

295

17

0 00

45

7

67 18

327

10

13

Haveri

65 30

169

13

74 80

160

17

57.60

220

12

000

28

5

67.18

326

9

14

U. Kannada

86.10

54

4

89.90

57

7

68.48

91

6

18.55

191

25

24 89

543

25

15

Bellary

54,00

229

19

52.60

320

23

46 16

381

22

0 00

27

16

Bidar

52.50

237

22

50 30

336

24

50 01

328

20

2.86

123

17

Gulbarga

47.70

262

27

25.30

494

27

38 40

471

26

0.65

18

Koooal

48.00

258

25

37.20

418

25

40.76

441

25

12 32

19

Raichur

48.00

260

26

37.20

419

26

36 84

484

27

20

Chikkamangalore

78 00

97

8

83.50

97

15

64.47

135

21

D. Kannada

91.50

38

2

86 00

78

13

77.39

22

Udupi

91.50

37

1

86.00

77

12

23

Hassan

69.70

145

11

92.80

31

3

24

Kodagu

79 40

90

6

94&0

17

25

Mandva

61.90

185

17

88 00

26

Mysore

69.70

144

10

92.70

27

Chamarajanagar

69 70

143

9

92.70^|.

Rank in

Karnataka

In 27

districts

%

Rank in

Rank In

India in Karnataka

569

in 27

districts districts

Rank In

Karnataka

In 27

districts

7.

'

Rank in

Rank in

India in Karnataka

569

in 27

districts districts

4

69 41

301

5

20

49 84

471

23

113

19

51 92

456

22

174

23

53.91

442

19

12.32

175

24

53.91

443

20

8

4.97

136

22

57.25

424

17

34

3

000

78

16

16 49

557

27

74.02

49

4

0.00

70

15

16.49

556

26

59.32

200

10

0.00

88

18

65.55

351

13

1

72.53

63

5

0 00

85

17

36 95

524

24

67

11

51.62

306.

19

0.00

69

14

58.65

417

16

34

5

55 81

246

14

0.00

67

13

68.16

315

7

33

4

43.02

419

24

_^P_oo_

53

8

68.16

314

6

DISTRICT WISE DEMOGRAPHIC INDICATORS OF KARNATAKA

Births registered

Deaths registered

Composite Index

Rani; in

Rank In

India In 569 Karnataka In

districts

27 districts

Rank In

Rank In

India In 569 Karnataka In

districts

27 districts

Rank In India

Rani; In

In 563

Karnataka in 27

districts

districts

SI.

No.

Districts

1

Sanqaiore(U)

86.87

145

19

91.17

42

18

75.19

73

2

Eangalore(R)

64.88

264

24

82 03

79

19

75.34

72

9

a

Chitradurga

93.84

82

7

95 11

23

9

73 98

84

11

4

Davanagere

50.56

316

27

32.27

371

27

65.43

173

21

5

Kolar

84.01

154

20

95.11

<b

1

71.92

106

16

6

Shimoga

93.84

88

13

95.11

29

15

80.37

29

2

7

Tumkur

90.53

119

18

94.66

31

17

73.97

85

12

8

Belgaum

93.84

80

5

95 11

21

7

68 75

135

18

9

Biapur

93.84

78

3

95.11

19

5

62.86

206

22

%

%

%

10

10

Bagalkote

54.77

307

26

34.95

358

26

54 71

299

26

11

Dharwad

93.84

81

6

95.11

22

8

73.03

96

13

12

Gadag

93.10

103

15

59 42

207

21

69 72

124

17

13

Haven

62.93

276

25

40 17

321

25

65.66

170

19

14

U.Kannada

93.84

85

10

95.11

26

12

76.11

61

5

15

Bellary

93.84

79

4

95 11

20

6

65.54

171

20

23

16

Bidar

91 10

115

17

95.11

18

4

60 55

230

17

Gulbarga

92.70

1C5

16

95.11

16

2

5831

255

25

18

Koppal

75.82

202

23

48 39

258

24

53 09

323

27

19

Raichur

93.84

77

2

95.11

17

3

58.34

253

24

20

Chikkamangalore

79.44

181

22

50 70

240

23

72.13

102

15

21

D.Kannada

93.84

86

11

95.11

27

13

78.77

41

4

22

Udupi

81.56

167

21

52.05

233

22

75.97

64

6

23

Hassan

93.84

89

14

95.11

30

16

81 55

25

1

24

Kodagu

93.84

87

12

95.11

28

14

80.06

30

3

25

Mandya

93 84

84

9

95.11

25

11

75.86

66

7

26

Mysore

93.84

83

8

95.11

24

10

75.70

68

8

27

Chamarajanagar

93.84

76

1

59.89

205

20

72.18

101

14

Source: National Population Commmission

HIN India Annex III - Project Budget

Implementing Partner:

Project Title:

WHO

Health InterNetwork, India Pilot

Start Date:

Completion Date:

Agency Project ID code:

IMIS Project ID:

UNFIP Project Reference No.:

07/01/01

12/31/02

Q

Revision:

(Explain reason for

revision, i.e„ "new start

date", "extension", etc.I

WHO-GLO-00-15OB

Project Budget

CCAQ

codes

UNDP

codes

Project

II

Object of Expenditure

Budge:

Work-rr.orins

Lines

011

11

040/060

030

330

030

12

18

15

14

1 Salaries

a

International Professionals

d

Consultants

c

National Professionals

d

UN Volunteers

e

Administrative assistants

Total

2 Travel

Evaluation

Other mission travel

16

17

21

21

22

810

820

32

33

600

45

45

45

49

830

79

620

640

350

=f)0

III

0

5,200

64,500

0

15,500

85,200

0

1

6

0

6

13

Year 2

USS

|

Wort-monlhs

0

1,300

21,500

0

5,200

28,000

0

3

12

0

12

27

Year 4

|

Work-monUts

USS

0

3,900

43,000

0

10,300

57,200

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

OSS

0

13,600

18.100

0

0

0

0

3 Contractual services

International

National

Total

183,200

183,200

0

131,000

131,000

0

52,200

52,200

0

0

0

0

4 Meetings and training

Fellowships

Seminars, workshops, meetings

Total

0

61,100

61,100

0

28,900

28,900

0

32,200

32,200

0

0

0

0

5 Acquisitions

a

IT equipment

b

Transport equipment

c

Other acquisitions

Total

237.400

2,500

1,100

241,000

237.400

2,500

1,100

241,000

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

10.000

18,100

12,700

40,800

600

9,800

6,300

16,700

9,400

8,300

6.400

24,100

0

0

0

___ 0_

0

719,000

535,200

183,800

0

0

7 Miscellaneous

Reporting costs

Supplies

Sundry

Total

8 Total Project Cost

99

0

4

18

0

18

40

|

WwA-monlhs

USS

4,200

85,400

89,600

6 Grants

Total

53

53

53

|

Year 1

8,700

99,000

107,700

Total

360

370

300

Total

4,500

9 Support Cost @ 5%

35,950

26,760

9,190

0

0

10 UNF Contribution Total

754,950

561,960

192,990

0

0

561,960

192,990

___ 0

0

11 Cost Sharing

0

12 Grand Total

754,950

Notes:

i

2

3

4

5

All line items should be rounded off to the nearest hundred dollar or nearest dollar, as applicable.

Each line item should have detailed supporting justification and/or information.

Operating Expenses include bank charges, expendable office supplies, telephone lines/fax charges, freight, etc..

Training includes workshops, seminars, fellowships and similar activities.

’UNF Contribution Total" comprises cost sharing provided through UNFIP

Use this sheet for one agency. See "Project total" sheet for more guidance

Implementing Partner:

(Name of agency for this portion of grant)

Project Title:

Health InterNetwork. India Pilot

Start Date:

Revision:

Completion Date:

37621

Agency Project ID code:

IMIS Project ID:________________

|UNFIP Project Reference No.:

[

(Enter specific agency project number)

0

(Explain reason for

revision, i.e., "new start

date", "extension", etc.)

□

WHO-GLO-OO-1508

Project Budget

CCAQ

codes

UNDP

codes

°ro;ecl

II

Object of Expenditure

Si-dgc!

Worii-mont/is

Lines

011

040/060

030

330

030

1 Salaries

a

International Professionals

b

Consultants

c

National Professionals

d

UN Volunteers

e

Administrative assistants

Total

11.01

11 96

17.99

14,99

13.99

2 Travel

Evaluation

Other mission travel

e

242

15 99

16.99

Total

360

370

300

21.01

810

820

31.99

32.99

|

0

0

0

0

0

0

USS

Work-months

0

0

0

0

0

0

|

0

Year 4

USS

WorK'/nonths

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

5 Acquisitions

a

IT equipment

b

Transport equipment

c

Other acquisitions

Total

0

0

0

0

0

0

6 Grants

Total

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

8 Total Project Cost

0

0

0

3 Contractual services

International

National

21.02

21.99

Year 1

Total

Total

0

0

4 Meetings and training

620

640

45.01

600

45.02

45.03

49

830

79

350

wo

Fellowships

Seminars, workshops, meetings

Total

7 Miscellaneous

Reporting costs

Supplies

Sundry

52.99

53.01

53 02

Total

99

9 Support Cost @ 5%

0

0

0

10 UNF Contribution Total

0

0

0

11 Cost Sharing

0

12 Grand Total

_____0_

____ 0

___ 0

Notes:

1

2

3

4

5

All line items should be rounded off to the nearest hundred dollar or nearest dollar, as applicable.

Each line item should have detailed supporting justification and/or information.

Operating Expenses include bank charges, expendable office supplies, telephone lines/fax charges, freight, etc...

Training includes workshops, seminars, fellowships and similar activities

"UNF Contribution Total" comprises cost sharing provided through UNFIP

|

USS

Use this sheet for one agency. See "Project total" sheet for more guidance

Implementing Partner:

(Name of agency for this portion of grant)

Project Title:

Health InlerNetwork, India Pilot

37073

Start Date:

Completion Date:

Revision:

37621

Agency Project ID code:

IMIS Project ID:________________

|UNFIP Project Reference No.:

|

(Enter specific agency project number)

0

WHO-GLO-OO-1508

Project Budget

CCAQ

codes

UNDP

codes

Pro;«!

011

040/060

030

330

030

11.01

1 *96

17 99

14.99

1 Salaries

a

International Professionals

b

Consultants

National Professionals

c

UN Volunteers

d

13.99

e

230

242

15.99

16.99

2 Travel

Evaluation

Other mission travel

Administrative assistants

Total

830

79

350

500

400

Worh-monlhs

|

________Year 2

Wcrk-months

USS

|

________Year 3

USS

0

0

0

0

0

0

3 Contractual services

International

National

Total

0

0

0

0

0

4 Meetings and training

Fellowships

Seminars, workshops, meetings

Total

0

0

0

0

0

5 Acquisitions

a

IT equipment

b

Transport equipment

c

Other acquisitions

Total

0

0

0

0

0

0

6 Grants

Total

0

0

0

0

7 Miscellaneous

Reporting costs

0

0

0

0

0

0

8 Total Project Cost

0

0

0

9 Support Cost @ 5%

0

0

0

10 UNF Contribution Total

0

0

0

________ 0_

________ 0_

52.99

53.01

53.02

Supplies

Sundry

Total

99

11 Cost Sharing

0

12 Grand Total

_________ 0_

Notes:

i

2

3

4

5

Work-morJhsJ

0

31 99

32.99

500

0

0

0

0

0

0

Year 1

USS

0

21.01

21 02

21.99

45.01

45.02

45.03

49

520

540

|

0

0

0

Total

810

820

Total

Work-monlhs

Unes

350

370

300

___________ iy_______

II

Object of Expenditure

Budgei

All line items should be rounded off to the nearest hundred dollar or nearest dollar, as applicable.

Each line item should have detailed supporting justification and/or information.

Operating Expenses include bank charges, expendable office supplies, telephone llnes/fax charges, freight, etc...

Training includes workshops, seminars, fellowships and similar activities.

*UNF Contribution Total" comprises cost sharing provided through UNFIP

USS

(Explain reason for

revision, i.e., “new start

date", “extension", etc )

□

Use this sheet for one agency. See "Project total" sheet for more guidance

Implementing Partner:

(Name of agency for this portion of grant)

Project Title:

Health InlerNetworfc, India Pilot

Start Date:

37073

Completion Date:

37621

Agency Project ID code:

IMIS Project ID:________________

|UNFIP Project Reference No.:

|

(Enter specific agency project number)

0

WHO-GLO-00-15OB

Project Budget

CCAQ

codes

UNDP

codes

Object of Expenditure

Budget

011

040/060

11.01

11.96

1 Salaries

a

International Professionals

b

Consultants

030

330

030

17.99

14.99

13 99

c

d

e

230

242

15 99

16.99

2 Travel

Evaluation

Other mission travel

21.01

370

300

21.02

21.99

810

820

31 99

32.99

620

45 01

640

600

45.02

45.03

49

830

79

|

VVoriiunonr/is

Lines

~360

i

Total

USS

National Professionals

0

0

o

0

0

o

UN Volunteers

Administrative assistants

Total

0

0

o

o

0

0

0

0

Total

0

Contractual services

International

National

Total

o

0

o

4 Meetings and training

Fellowships

Seminars, workshops, meetings

Total

5 Acquisitions

a

IT equipment

Transport equipment

b

c

Other acquisitions

Total

6 Grants

Total

0

o

0

o

0

o

0

0

0

7 Miscellaneous

350

500

400

Reporting costs

Supplies

Sundry

Total

52.99

53.01

53.02

0

0

0

0

8 Total Project Cost

9 Support Cost @ 5%

10 UNF Contribution Total

11 Cost Sharing

12 Grand Total

Notes:

i

2

3

4

5

All line items should be rounded off to the nearest hundred dollar or nearest dollar, as applicable

Each line item should have detailed supporting justification and/or information.

Operating Expenses include bank charges, expendable office supplies, telephone lines/fax charges, freight, etc.

Training includes workshops, seminars, fellowships and similar activities.

"UNF Contribution Total" comprises cost sharing provided through UNFIP

Use this sheet for one agency. See "Project total" sheet for more guidance

Implementing Partner:

(Name of agency for this portion of grant)

Project Title:

Health InterNetworfc. India Pilot

Start Date:

37073

Completion Date:

Agency Project ID code:

IMIS Project ID:

|UNFIP Project Reference No.:

(Explain reason for

revision, i.e., "new start

date”, "extension", etc.)

□

Revision:

37621

(Enter specific agency project number)

0

|

WHO-GLO-00-15OB

Project Budget

CCAQ

cooes

011

040/050

030

330

030

230

—^2

UNDP

codes

^oject

II

Object of Expenditure

BixJget

|

Work-norths

11.01

11 96

17.99

14 99

1 Salaries

a

International Professionals

b

Consultants

c

National Professionals

d

UN Volunteers

13.99

e

Administrative assistants

Total

2 Travel

Evaluation

Other mission travel

15.99

15 99

Total

IV

Year 1

Total

Work-tr,Orths

USS

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

|

0

Year 3

USS

VV<y><-n:on//)S

0

0

0

|

0

Year 4

USS

Work -norths

0

|

0

USS

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3 Contractual services

360

370

300

21.01

2 V02

21 99

810

820

31.99

32 99

International

National

Total

0

0

0

4 Meetings and training

600

45.01

45 02

4503

49

830

79

620

540

350

500

400

•

Fellowships

Seminars, workshops, meetings

Total

5 Acquisitions

a

IT equipment

b

Transport equipment

c

Other acquisitions

Total

6 Grants

Total

7 Miscellaneous

Reporting costs

Supplies

Sundry

Total

52.99

53.01

53.02

99

8 Total Project Cost

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

9 Support Cost @ 5%

0

0

0

0

0

10 UNF Contribution Total

0

0

0

0

0

_____ 0

____ 0_

____ 0_

0

n Cost Sharing

12 Grand Total

Notes:

i

2

3

■i

5

0

____ 0_

All line items should be rounded off Io the nearest hundred dollar or nearest dollar, as applicable

Each line item should have detailed supporting justification and/or information.

Operating Expenses include bank charges, expendable office supplies, telephone lines/fax charges, freight, etc

Training includes workshops, seminars, fellowships and similar activities.

"UNF Contribution Total" comprises cost sharing provided through UNFIP

*

HealthlnterNetworklndiaPilot

| Duration

TaskName

Projectworkplan

Finish

Start

Odays

Thu8/9/01

Thu8/9/01

Jul

August _

Septembe

Aug

Sep

Define and identify main stakeholders, reference sites and access poi

1wk

Fri6/15/01

Thu6/21/01

Conduct detailed needs assessments at sites and determine requirem

6wks

Fn6/22/01

Thu8/2/01

2

Developworkplan(includingworkshopwithkeystakeholders)

1wk

Fri8/3/01

Thu8/9/01

3

Health ResearchlnformationSystem

Odays

Thu12/13/01

Thu12/13/01

Network key research institutions related to tuberculosis and tobacco

18wks

Fri8/10/01

Thu 12/13/01

4

8/1 (

Develop processes and templates for dissemination of research (incli

6wks

Fri8/10/01

Thu9/20/01

4

8/1(>[T

8/1 h

Odays

Thu12/13/01

Thu12/13/01

Review and adapt system for developing integrated Virtual Health Lib

9wks

Fri8/10/01

Thu 10/11/01

4

Network medical college libraries in reference states with National M(

9wks

Fri 10/12/01

Thu 12/13/01

11

NetworkMedicalCollegeLibraries

Odays

Thu 1/3/02

Thu1/3/02

Establishcontentselectioncriteria.standardsandprocesses

4 wks

Fri8/10/01

Thu9/6/01

4

e-publishing of selected journals and other key information (national

17wks

Fri9/7/01

Thu 1/3/02

15

Userinterfacedevelopment

20wks

Fri8/10/01

Thu 12/27/01

20

Connectivityandinfrastructureataccesspoints

Odays

Thu 1/3/02

Thu 1/3/02

21

Establishtechnicalspecifi cations, standardsandprocess

2wks

Fri8/10/01

22

Establishconnectivity (hard ware,software, intemetconnectivity)

19wks

Fri 8/24/01

24

Training/development

Odays

Thu1/3/02

Thu 1/3/02

25

Developtrainingmodules

17wks

Fri 8/10/01

26

Conductimtialtrainingprogramsatsites

4wks

Ongoingprojectmanagementandsupport

Trainingupdatesduringpilot

Electronicpublishingofkeyjournalsandotherkey information.

•n-18/2

>0

( :

10/

8/1 (>D

4

8/1 (> n

Thu8/23/01

4

8/1

Thu 1/3/02

21

'8/24

Thu 12/6/01

4

8/10>y~

Fri 12/7/01

Thu 1/3/02

25

52wks

Fri 1/4/02

Thu 1/2/03

22

52wks

Fri 1/4/02

Thu 1/2/03

22

8wks

Fri 1/3/03

Thu2/27/03

28

||----- 1|—j 8/23

23

27

28

29

30

31

32

|

Pilotevaluation

Task

Task Progress

u

Milestone

RolledUpMilestone

Summary

RolledUpProgress

CriticalTask

RolledUpTask

CriticalTaskProgress

RolledUpCriticalTask

II

Split

ExternalTasks

Pagel

Projectsummary

th9'6

HealthlnterNetworklndiaPilot

Task

1)____ ___ u

Milestone

CriticalTask

II____ _____ 0

RolledUpTask

CriticalTaskProgress

RolledUpCriticalTask

0____ _______ I)

u____ _______ |]

Rolled UpMilestone

xz

Split

1

1

□__________ J

ExternalTasks

Page2

Projectsummary

■----- 1

e"wo:k :/ esting at Ni ’ Sanglore

‘

■ >• ■?':: TS TTTftft. "r.ftcTTSftwrk Bfeefcg aft NT;' IBte’t.g

ft Cm. /00'' 17.//:'. 8 +053C

Thelma 1

S Sadagopar. T

•• Sudha

msiO’” <socha~a@vsr.'.csm>,

■ <ss@'iT2.ac.iT>,

<-ti~die@bjr.vs~..--et.in>,

^©ir.dsg^r.e. -.orr.”’ <sic@indegene.com>

Dear all.

Thank you very much taking out the time fir the meeting and your valuable thoughts/ suggestions/ comments

Will keep you posted with the developments, which should move quickly now.

Best Regards,

Ranjan

-C-ghai Message -Pwvgdj x

"hursday, October 04, 2001 5:19 PM

;ago:= (E--=‘ ); V-mala Murthy (E-mail); Thelma Narayan (E-mail); S Sadagopan (--ma;:), i-.dha v.-.—. (

- ee t- "rernstworx-Yeeting at NT; 3angiore,

‘ -a '.gs-".-.

:~z •"aeting at ths National TubercTosis mstitute, 3anga;:;m :

,-.'6C 2S CV

'

^’'.csrS;';''2:ng of the scops of the pilot.

' repsrstory ''3.x: steps.

:c;rg c*

and resource persons for different project compor.3’: s

4o:~er matte”.

tsk’-c 'cm/ara : me meeting

-<s"i an

j-’ .■

• T enders wou^d be joining iater

Ranjan Dwivea:

°rcject Manager- KeaSt”. nierNetwork India Project

•Aoric Health Organization

Rm 530 'A‘ Wing, \iman Bhawan, New Delhi

a

HEALTH INTERNETWORK INITIATIVE

TECHNOLOGY ADVISORY WORKSHOP

Date:

October 10-11, 2001

Venue: Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization

525 Twenty-third Street, N W.

Washington, D C 20037

USA

The Health InterNetwork Initiative

In September 2000 UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, launched the Health

InterNetwork as a partnership to bridge the digital divide in health. Led by the World

Health Organization, the Health InterNetwork (HIN) brings together international

agencies, the private sector, foundations, non-governmental organizations and country

partners under the principle of ensuring equitable access to health information. The aim

of the initiative is to improve public health by improving the information environment of

health personnel, health-care providers, researchers and scientists, and policy makers

The core elements of the initiative are content, connectivity, and capacity building.

The Health InterNetwork site will help users find, organize, and share information for

public health. The information itself is produced and managed by different content

providers around the world Users will be able to access statistical data, scientific

publications and information for health policy and practice, as far as possible in their own

language. In addition, the site will make available a range of health information

technology applications such as geographical information systems and epidemiological

tools, as well as courses and training offered through distance learning. Particular

attention will be given to the production and publishing of local and regional healthrelated information that is currently unavailable electronically.

1.

Objectives of the Technology Advisory Workshop

The overall goal is to review technology options and provide recommendations for the

development and deployment of the Health InterNetwork site.

1.

Examine user scenarios, requirements, architecture, hardware and software

platforms, development process and software tools and resources,

knowledge/content management, connectivity implications and other technologyrelated issues which will impact site development and use.

2.

Consider implications, risks and potential cost and time requirements for

recommended options.

3

3.

Issues for Discussion by Workshop Participants

User and content requirements - Characteristics of the data in each content area,

global and local user requirements, and language implications.

Processes - Syndication of content from major content providers; publishing of local

content; authentication processes for restricted information; search, retrieval, and

display requirements, meta-data in building community and collaborative

environments; site architecture, navigation, and user interface design; development

options and associated implications, risks, and costs; updates and maintenance

issues.

Hardware options - Server platform, user devices, hardware options and

constraints; maintenance logistics; costs, risks, and implications

Software options - user device operating system, internet browser, email package,

office suite, proprietary and non-proprietary design tools; knowledge management

tools; search engines; databases; scalability; developer’s toolkits; management

interfaces; proprietary and non-proprietary applications for public health, authoring,

distance education, statistical packages, logistical support of health services

operations, peer-to-peer interactivity, etc; security

Connectivity - Constraints at country level e g. spectrum of options to access the

functionalities limited by existing telecommunication infrastructure, service level of

local ISP, and last-mile issues.

Technology resources - Identification of companies, experts, international and

national organizations, key national partners, academic institutions who could

contribute to HIN project

4.

Participants List - tentative

(See attachment)

5.

Background information on the Health InterNetwork Initiative

(See attachment)

HEALTH INTERNETWORK INITIATIVE

TECHNOLOGY ADVISORY WORKSHOP

Date:

October 10-11, 2001

Venue: Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization

525 Twenty-third Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C 20037

USA

The Health InterNetwork Initiative

In September 2000 UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, launched the Health

InterNetwork as a partnership to bridge the digital divide in health. Led by the World

Health Organization, the Health InterNetwork (HIN) brings together international

agencies, the private sector, foundations, non-governmental organizations and country

partners under the principle of ensuring equitable access to health information. The aim

of the initiative is to improve public health by improving the information environment of

health personnel: health-care providers, researchers and scientists, and policy makers.

The core elements of the initiative are content, connectivity, and capacity building.

The Health InterNetwork site will help users find, organize, and share information for

public health. The information itself is produced and managed by different content

providers around the world. Users will be able to access statistical data, scientific

publications and information for health policy and practice, as far as possible in their own

language. In addition, the site will make available a range of health information

technology applications such as geographical information systems and epidemiological

tools, as well as courses and training offered through distance learning. Particular

attention will be given to the production and publishing of local and regional healthrelated information that is currently unavailable electronically.

1.

Objectives of the Technology Advisory Workshop

The overall goal is to review technology options and provide recommendations for the

development and deployment of the Health InterNetwork site.

1

Examine user scenarios, requirements, architecture, hardware and software

platforms, development process and software tools and resources,

knowledge/content management, connectivity implications and other technologyrelated issues which will impact site development and use.

2.

Consider implications, risks and potential cost and time requirements for

recommended options

2

3.

Outline strategy for site design, development, hosting, and testing, including phases,

timeline, milestones, priorities, partners, and options.

4.

Generate list of technology-related resources (products, corporations, institutions,

and individuals) for planning and resource commitment and to involve in follow-up

activities

2.

Proposed Content Areas

The particular strength and added value of the HIN site will be the rapid access to quality

assured public health information from multiple sources, as well as support for local and

locally/regionally-produced information - no site offers these features today. Earlier this

year a working group identified five content areas for the Health InterNetwork.

Content areas

Statistical

Data

Scientific

Publications

Information

Collections

Distance

Education

Numerical

information sets

- can include

raw, analyzed,

validated data

Peer-reviewed

primary

scientific

literature, and its

reviews and

indexes

Professional

and continuing

education and

training

packages

ICT tools for

public health

policy and

practice

Official

(international

organization,

national

government)

data and

statistics

Published

scientific

research (may

be priced)

Courses and

training products

for health

professionals at

all levels

Communication,

networking, and

publication tools

inc.

communities of

practice

applications

Epidemiological,

statistical,

program data

from different

sources

Major databases

(eg.

bibliographic,

evidence

compendia), text

books and

manuals

Information

packages.

created for

specific public

health

audiences and

purposes

Policies, reports.

guidelines,

protocols.

reference

material, and

authoritative

health

communication

material

' Gray" literature

and other

publications

Programmed

instruction

products

Public health

work

applications

(eg

Geographical

Information

Systems,

statistical

packages,

training and

diagnostic tools.

telemedicine)

Health IT

Applications

3

3.

Issues for Discussion by Workshop Participants

User and content requirements - Characteristics of the data in each content area;

global and local user requirements; and language implications.

Processes - Syndication of content from major content providers; publishing of local

content; authentication processes for restricted information, search, retrieval, and

display requirements; meta-data in building community and collaborative

environments; site architecture, navigation, and user interface design, development

options and associated implications, risks, and costs; updates and maintenance

issues.

Hardware options - Server platform, user devices, hardware options and

constraints; maintenance logistics; costs, risks, and implications.

Software options - user device operating system, internet browser, email package,

office suite; proprietary and non-proprietary design tools; knowledge management

tools; search engines, databases; scalability; developer’s toolkits; management

interfaces; proprietary and non-proprietary applications for public health, authoring,

distance education, statistical packages, logistical support of health services

operations, peer-to-peer interactivity, etc, security

Connectivity - Constraints at country level e g spectrum of options to access the

functionalities limited by existing telecommunication infrastructure, service level of

local ISP, and last-mile issues

Technology resources - Identification of companies, experts, international and

national organizations, key national partners, academic institutions who could

contribute to H1N project.

4.

Participants List - tentative

(See attachment)

5.

Background information on the Health InterNetwork Initiative

(See attachment)

UNF/UNFIP Project Document

Health InterNetwork (India Pilot)

12 June 2001

World Health Organization

HIN India

Health InterNetwork (India Pilot)

Project document

1.0

CoverPage

• Project title:

Health InterNetwork (India Pilot)

■

Project number:

WHO-GLO-00-150B

•

Project purpose:

To test scalable, sustainable approaches to bridging

the digital divide in health information and the gaps

between health research, policy and practice

■

Duration:

18 months

•

Expected start date:

1 July 2001

■

Location:

India, 2 states: Orissa - Deogarh district;

Karnataka - Bangalore rural district

•

Lead UN agency:

World Health Organization

(WHO country office, New Delhi)

•

UN cooperating agencies

UNDP and UNICEF country offices in India

■

Non-UN executing partners:

National: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Ministry of Information Technology, National

Tuberculosis Institute, Tata Institute of Social

Sciences, Bharat Electronics Ltd., private

corporations (e.g. NIIT, TCS, Indegene Life Systems,

2 Streams Media), and NGOs (e.g. Sochara)

International: Harvard Center for International

Development and MIT Media Lab, Cornell

University, BIREME, Collexis Corp., Projecl.net Inc.

■

Total budget:

USS 754,950

■

UNF funding:

USS 754,950 (inch 5% programme support costs)

■

Summary project description:

- Facilitate an Internet-based network of health

service providers, researchers, and policy makers in

the tuberculosis and tobacco control programs

- Provide and test content, connectivity and training

options to enable optimal use of this network

- Enhance the capacity of local research institutions

and medical libraries to support and scale up the

Health InterNetwork

7

World Health Organization

HIN India

I.

2,0

Background and Analysis

Problem Statement/ Challenge/ Context

The Health InterNetwork Project

In September 2000, the UN Secretary-General launched a public-private initiative

to bridge the digital divide in health. Led by the World Health Organization, the Health

InterNetwork brings together international agencies, the private sector, foundations, non

governmental organizations and country partners under the principle of ensuring

equitable access to health information. The aim is to improve public health by facilitating

the flow of health infonnation, using the Internet. Health information - relevant, timely

and appropriate - must become unrestricted and affordable worldwide, so that all

communities can benefit from this global public good.

The focus of the Health InterNetwork (HIN) is on improving the information

environment of health personnel: professionals, researchers and scientists, and policy

makers. The core elements of the project are content, connectivity and capacity building.

I. Content: to deliver effective public health services

An Internet portal will provide a shortcut to high-quality, relevant and current

infonnation on public health. Users will be able to access statistical data, scientific

publications and information for health policy and practice, as far as possible in their own

language. In addition the portal will make available a range of infonnation technology

health applications such as geographical infonnation systems and epidemiological tools,

as well as courses and training offered through distance learning. Particular attention will

be given to the production and publishing of local and regional public health information

that is currently unavailable electronically.

II.

Connectivity: for information and communication

Starting on a small scale with 6-8 pilot projects and rolling out over a 7-year

period, the Health InterNetwork seeks to establish and equip up to 10,000 Internetconnected sites. The logistics of supplying, delivering and installing hardware and

software, Internet connectivity and providing maintenance will require working with non

governmental organizations and corporate and local private sector partners.

III.

Capacity building: to create an enabling information environment

Finding, evaluating, using and managing information is a significant challenge in

public health settings all over the world. Health InterNetwork training will concentrate on

building the skills needed to put infonnation into action: 1) infonnation access and use in

daily work, 2) basic computer and Internet skills, and 3) hands-on training to use

specialized public health tools.

3

World Health Organization

HIN India

HIN India pilot

India was selected as the one of the first HIN pilot countries because it has several

priority public health programs as well as valuable skills and resources that would

contribute to the development of the global Health InterNetwork project. Each HIN pilot

focuses on a particular facet of the overall Health InterNetwork. In the HIN India pilot,

the focus is on the gaps between health research, policy and practice.

Gaps between health research, policy and practice in India

These gaps exist throughout the world and have to be addressed to ensure that

relevant research reaches citizens in the form of effective, up to date health care.

Dr C.P. Thakur, the Union Minister for Health and Family Welfare, has

highlighted the gaps in the health research, policy and practice in India. In his 2001 status

report on TB in India, he points out that, as an example, most of the significant research

on the cure and control strategy for tuberculosis was carried out in India. Pioneering

research from the Tuberculosis Research Center, Chennai, and the National Tuberculosis

Institute, Bangalore, included:

the effectiveness of ambulatory treatment of tuberculosis, the effectiveness of intermittent

treatment regimes, the necessity of direct observation of treatment (DOT) by a trained

individual who is not a family member, the usefulness and practicability of AFB

microscopy as a diagnostic tool among patients reporting to health facilities and the

crushing burden of disease of tuberculosis on our society.

However, while several other countries benefited from these findings, India was

among the last countries to introduce this key life-saving research into its own health

policy and practice.

Regarding tobacco-related morbidity, the WHO Director-General observed last

year that it was in India, in 1964, that the first link between oropharyngal cancer and

chewing tobacco was identified. Studies from eastern India were the first in the world to

link palate cancer to the chewing of tobacco. Yet again, while other countries were able

to act decisively on this research, the tobacco control program in India is still in its

inception.

The implications of these gaps between health research, policy and practice must

be considered in the context of the magnitude of the two public health problems

discussed above - tuberculosis and tobacco use.

The burden of tuberculosis

In the 2001 report on tuberculosis, the Directorate General of Health Services in

India presents the effect of the disease on the country and its people, despite there being a

cure for the disease.

4

World Health Organization

HIN India

Everyday in India more than 20 000 people become infected with the tubercle bacillus.

more than 5 000 develop the disease, and more than 1 000 die from TB. India accounts

for nearly one third of the global burden of tuberculosis and the disease is one of India's

most important public health problems.

Tuberculosis is a major barrier to social and economic development. The direct and

indirect costs of tuberculosis to the country amount to Rs. 12 000 crore (US $3 billion)

per year. Every year, more than 17 crore (US $170 million) workdays are lost to the

national economy on account of tuberculosis, at a cost of Rs. 700 crore (US $200

million).

Every year, 300 000 children are forced to leave school because their parents have

tuberculosis, and 100 000 women lose their status as mothers and wives because of the

social stigma of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis kills more women than all causes of maternal

mortality combined (TB India 2001).

The Revised National Tuberculosis Program (RNTCP) has made a significant

impact on the burden of disease related to tuberculosis. Currently the program covers

more than one third of the country and 80% of the patients treated are being cured of the

disease compared with the 25% cure rate of a decade earlier. However there is still a lot

of effort needed to combat the disease and 'unless urgent action is taken more than 40

lakh (4 million) people in India will die of tuberculosis in the next decade'.

The tobacco threat

Tobacco has been established to be a risk factor in over 25 diseases, the first links

to cancer having been identified in India as mentioned earlier. In her address at the

International Conference on Global Tobacco Control Law in New Delhi, the WHO

Director-General Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland stated:

Today in India, tobacco kills 670,000 people every year. If unchecked and unregulated,

by 2030, tobacco will kill 10 million people each year. Seventy percent of those deaths

will occur in the developing world, with India and China in the lead. If nations do not act

individually and together, in the next 30 years, tobacco will kill more people than the

combined death toll from malaria, tuberculosis and maternal and child diseases. Every

tobacco related death is preventable. That is our message. That is our challenge.

The Framework Convention was introduced as a new legal instrument negotiated

by WHO, its member countries, and partners, including UNICEF and the World Bank, to

deal with the problem of tobacco use in a comprehensive manner.

The Framework Convention is expected to address issues as diverse as tobacco

advertising and promotion, agricultural diversification, product regulation, smuggling,

excise tax levels, treatment of tobacco dependence and smoke-free areas.

The Framework Convention process will activate all those areas of governance that have

a direct impact on public health. Science and economics will mesh with legislation and

litigation. Health ministers will work with their counterparts in finance, trade, labour,

agriculture and social affairs ministries to give public health the place it deserves.

5

World Health Organization

HIN India

Where are the gaps between health research, policy and practice?

There are several factors that contribute to the disjoint between research, policy

and practice. For instance, one important reason why research is not effectively utilized is

that it is often not perceived to be relevant to the priority health needs of the country. A

comparison of medical research carried out in India (as reflected by published literature)

with the country's healthcare needs (as reflected by morbidity and mortality statistics)

showed that there was a considerable mismatch between the two (Subbiah Arunachalam

1998). In addition the variability in reliability and validity of health research further

reduces its perceived utility.

The main objective of the Health InterNetwork project is to address the digital

divide in health information. Policy makers, researchers, health practitioners, information

scientists and librarians identified reasons for the current disjoint between research,

policy and practice in the context of the HIN project, access to research, dissemination of

research, and the environment for communicating research using information and

communication technologies.

I. Access to health research

India accounts for 23% of the global burden of disease from tuberculosis but only

for 5-6% of the world’s research output in this area as seen from papers indexed in three

international databases, viz. PubMed, Science Citation Index and Biochemistry and

Biophysics Citation Index over the ten years 1990-1999'. To improve the relevance of

health research the value of developing country research has to be recognized and

promoted.

In addition, access to these international databases is expensive and difficult.

Equitable and effective dissemination of health research information has to be ensured.

Currently in India it costs USS 12 to get one full text journal article from an international

database. It can take up to four months for a copy of this article to be delivered by surface

mail from the National Medical Library which has the single largest collection of

scientific and medical journals, both national and international, in the country. Most of

these journals are currently only available in hard copy.

Even when the research information is available it is often not in the form most

useful for the different stakeholder groups in health. Very few people, other than

researchers, read through multiple page reports or articles on research protocols and

findings. The appropriate formatting of research information is therefore crucial to

enhance the utilization of research for health policy and practice.

II.

Dissemination of research

There are various efforts related to dissemination of health research in India.

However, a huge amount of (valuable) unpublished information lies around in research

and medical institutions as raw or partially analyzed data. There is also considerable

6

World Health Organization

H1N India

duplication of effort across public, private and academic sectors involved in health care

and very little coordination between them.

Various agencies, donors, private and academic institutions all commission

research related to tuberculosis and tobacco control in India. However, there is no

network in the country to coordinate these efforts or to make this information available to

health policy makers, practitioners or other researchers. The flow of research information,

both international and national, leaves much to be desired and it can take several months

and even years for data to be analyzed and disseminated, all this reducing the perceived

utility of research for policy and practice.

III. The environment for the communicating health research using information and

communication technologies

Information and communication technologies offer cogent solutions to some of

the problems related to the access and dissemination of health research. These solutions

include tools for structuring health information networks, facilitating electronic

publishing, building searchable databases of local research, and enabling Internet-based

exchange of health information. However, these solutions have significant resource

implications and have to be situated in the larger social and political environment of the

country.

Infrastructure

An e-readiness assessment was conducted in five states that were initially

proposed for the Health InterNetwork India pilot. An e-readiness assessment tool

developed by the Harvard Center for International Development and the MIT Media Lab

(http://www.readinessguide.org ) was used for this purpose. The assessment showed that

even slates that were considered to be at the forefront of the information technology

revolution, in India and internationally, still faced many of the environment-related

problems outlined in the UN Administrative Committee on Coordination (ACC) 1998

statement:

The information technology gap and related inequities between industrialized and

developing nations are widening: a new type of poverty - information poverty - looms.

Most developing countries, especially the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), are not

sharing in the communication revolution, since they lack:

• affordable access to core information resources, cutting edge technology and to

sophisticated telecommunication systems and infrastructure;

■ the capacity to build, operate, manage, and service the technologies involved;

■ policies that promote equitable public participation in the information society as both

producers and consumers of information and knowledge; and

■ a work force trained to develop, maintain and provide the value-added products and

services required by the information economy.

Inequity

7

World Health Organization

HIN India

In addition to addressing these basic infrastructural issues care has to be taken that

the introduction of new technologies does not exacerbate existing inequities or create new

ones not only on an international level, but also within the country. For example, only 22

people in 1000 have telephone access in India and less than 2 in 1000 use the Internet. Of

Internet users in India more than 75% are males under the age of 30 from the higher

educated strata in the country (Eddie Cheung 2001). Facilitating equitable access has to

be paid particular attention when considering the use of technology in the health system

where professionals higher up in the health system hierarchy, like doctors and policy

makers, are predominantly male while the majority of the countries community health

workers are female.

Building up the basics

In considering the far-reaching and creative solutions offered by infonnation and

communication technologies, it is therefore important not to lose track of the foundations

on which these solutions must rest.

At a meeting to plan the Health InterNetwork India, Professor S. Vijaya, a

researcher currently working on genetics and tuberculosis at the Indian Institute of

Science, emphasized the importance of starting with the basics, and building up the

foundation of health research, policy and practice system in the country:

Research information needs to be compiled and made to reach the medical community as

well as the policy makers. In another 5 to 10 years, we should be able to see it making a

dent in the manner in which medical students are taught. I do believe that if we in India

can ensure that every medical graduate will come out and treat every TB patient he or she

sees with the standard, (current) WHO prescribed regimen of anti-TB drugs, we can

dramatically reduce the incidence of both TB as well as drug resistance.

I find the possibility exciting that we too, like some of the developed countries can make

a dent in our TB control programme without waiting for that miracle new drug that

everyone promises.

3.0

Relationship to UNF/UNFIP Programme Framework and Project Criteria

In 1998, ACC expressed profound concern at the deepening maldistribution of

access, resources and opportunities in the infonnation and communication field and

committed the organizations of the United Nations to assist developing countries in

redressing these alarming trends.

Through establishing new connectivity and infrastructure in developing countries

the Health InterNetwork responds to the ACC commitment to address the growing

inequities related to information and communication resources. In addition, the India pilot

aims to support priority health programs for tuberculosis and tobacco control where the

ultimate beneficiaries are the 'poorest of the poor1 who invariably bear the greatest burden

of these problems.

8

World Health Organization

HIN India

4.0

National/Government Commitment

The Government of India is firmly committed to the use of information and

communication technology for health. In 1986 the Indian Medlar Centre was set up as a

joint project of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National

Informatics Centre (http://indmed.delhi.nic.in) to facilitate access across the country to

national and international bio-medical information. More recently, there have been two

major initiatives planned by the national government that correspond to the Health

InterNetwork objectives.

An expert committee on the Application of Information Technology in Medical

Education in India in its report dated January 2001, recommended that the following

projects be implemented through the Ministry of Health,

* School of Health Informatics at the Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of

Medical Sciences, Lucknow,

■ Developing the use of IT for research, teaching and patient care at the

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh,

" Knowledge network on Medicinal Plants and National Centre for Training and

Technology Transfer at the Regional Research Laboratory at Jammu,

■ Developing a National System of Flealth Research Information al the ICMR.

On March 22, 2001 the Prime Minister of India launched a national scheme for

linking 23 government medical college libraries. The scheme, with a budgetary provision

of over USS200,000, provides basic infrastructure, connectivity, and training to one

medical college library each in of 23 States. The libraries will be networked to share the

resources of the individual libraries as well as of the National Medical Library located in

Delhi.

The Health InterNetwork pilot will integrate with these national priority programs

and will thus also provide a means of integration between the individual national

programs.

Prerequisites and policy

The processes for logistic and policy procedures for implementation of the project

are in place. Representatives of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Indian

Council of Medical Research, Ministry of Information Technology, National Institute of

Communicable Diseases, and the National Informatics Centre are key members of the

core team formed to facilitate planning, implementation and evaluation of the HIN pilot

project. The pilot project has evolved from discussions in the core team and the direct

involvement of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The pilot will be coordinated

through a full time project manager in the office of the WHO Representative to India with

support from the HIN task force based at the WHO headquarters.

9

World Health Organization

I-IIN India

Integration and sustainability

The project responds to the needs of the government and integrates with the

government plans for ICT and health. The government has earmarked complementary

funding that augurs extremely well for the sustainability. For each component of the pilot

project a focal point has been identified from key governmental institutions to facilitate

project ownership, implementation and integration with the larger national infrastructure

and capacity building efforts.

5.0

Process followed in Project Identification/Formulation

In his announcement at the 2000 Millenium Assembly, the UN Secretary General

Kofi Annan described the Health InterNetwork in the following terms:

This network will establish... 10,000 on-line sites in hospitals, clinics and public health

facilities throughout the developing world. It aims to provide (tailored) access to relevant

up-to-date health and medical information...

The equipment and Internet access, wireless where necessary, will be provided by a

consortium... in co-operation with foundation and corporate partners.

Training and capacity-building... is an integral part of the project. The World Health

Organization is leading the United Nations in developing this initiative with external

partners.

Following this commitment from the Secretary-General, an inter UN agency

meeting was held in Geneva to define the specific objectives of the project. A small HTN

task force began working on the project at WHO, Geneva, with financial support from the

UN Foundation of USS 734,000. It was decided to develop the project up on the basis of

6-8 pilot projects conducted during the first year. India was selected as the first HIN

pilot country because it has several priority public health programs as well as the skills

and resources that would contribute to the development of the global Health

InterNetwork.

Over the next couple of months, meetings were held in India with key

stakeholders in health and information and communication technology in the country

(including the government, local UN agencies, NGOs, research institutions, policy

makers, health service providers, researchers, and the private sector) to discuss options

for the pilot project focus and scope. In addition, through a questionnaire the information

needs of over 600 policy makers, health service providers, researchers were assessed.

(The results of this assessment and other project related information is available on the

project development web site at www.hin.org.in).

10

World Health Organization

HIN India

Based on these inputs a draft project plan and logical framework were drafted

and circulated to some key experts and stakeholders. The consultations on this draft were

used to build up this proposal including the logical framework (Annex 1).

6.0

a.

Related Past and Current Activities

Lessons learned from past approaches to resolve the problem

There have been some very successful experiences related to the use of

information and communication technologies for development in India and there are four

main lessons to heed.

I.

Focus on need-based content

Mr Arunachalam, who coordinates an innovative, useful and used telecenter

project in rural Tamil Nadu advises, "The first thing we should do is to shift our focus

from the technology part of IT to the information (or content) part. (People's) information

needs are different. It is only on the basis of their current needs and how they get those

needs satisfied (that) one can think of meaningful technological interventions."

Dr C.A.K. Yesudian, head of the Department of Health Services at the Tata

Institute of Social Sciences, also emphasizes that the key to the success of the FUN India

project will be an in depth understanding of the needs of the main stakeholders involved

in the project. In addition he notes that this understanding would need to inform building

up the capacity of local institutions to meet these and future needs past the project phase.

II.

Aim for broad access and resource sharing

Capacity building cannot be confined to central institutions. 'When resources are

limited and the population to be served is very large, then considering community-based

access (to affordable and appropriate technology) and resource sharing is the only choice.

That is precisely what Sam Pitroda did, when Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi called for his

help in improving telecom services in India. Thanks to Pitroda’s plan, today virtually

every town in India has a public telephone booth within a short distance from where one

can make local, national and international calls' (Subbiah Arunachalam 1999).

III.

Use local solutions

Dr Ashok Jhunjhunwala of the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, noticed

that if telephone coverage had to move from 1 per cent of Indian homes to 15 to 25 per

cent, the transition would cost an astronomical sum, way beyond the means of a

developing country. The only solution was to get rid of the expensive copper wires,

which need to be hooked to every home wanting a phone connection. The problem

identified, Dr Jhunjhunwala went ahead to make the breakthrough 'wireless local loop'

technology, that also enables Internet access. And at less than half the price of similar

methods developed elsewhere (Shobha Warner 1997).

11

World Health Organization

HIN India

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science and Bharat Electronics Limited who

are developing the cost-efficient, local language and Internet enabled Simputer have also

made significant advances in this respect.

IV.

Foster an enabling environment

Mrs S.L. Chinnappa (who was responsible for developing the Indian Medlars

Centre, bringing Medline to India, and developing library databases for several key

institutions in India) noted that,

WHO while starting a Health Information Network in India should ensure right from the

beginning, that the best practices of sharing, exchange of ideas and reciprocal contracts

are fostered among the participating institutions - whether Governmental or non

governmental - it should truly be a collaborative network. There should be very low or no

regulatory barriers to join the network.