REACH AND EVALUATION OF COMMUNITY HEALTH

Item

- Title

- REACH AND EVALUATION OF COMMUNITY HEALTH

- extracted text

-

RF_COM_H_49_A_SUDHA

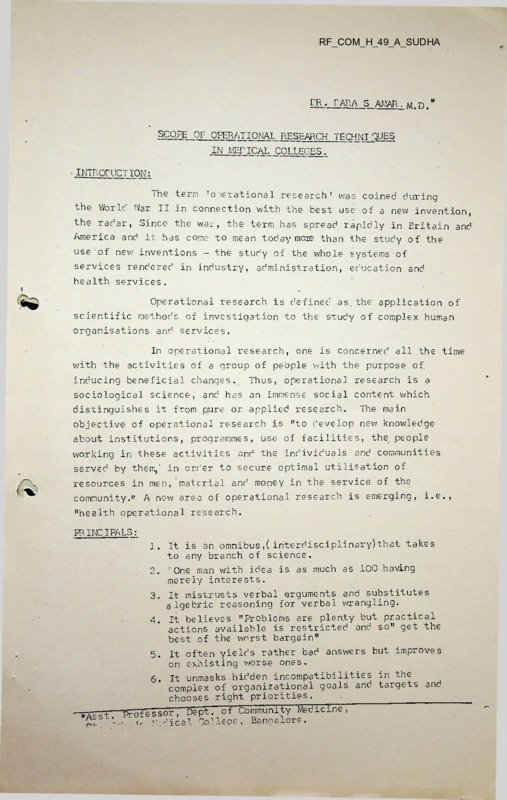

PR. PARA S AMAR. M.D.*

SCOPE OF OPERATIONAL RESEARCH TECHNI QUES

IN MEFICAL COLLEGES.

-INTROPUCTION:

The term 'operational research' was coined during

the World War II in connection with the best use of a new invention,

the radar, Since- the war, the term has spread rapidly in Britain and

America and it has come to mean today more than the study of the

use of new inventions - the study of the whole systems of

services rendered in industry, administration, education and

health services.

Operational research is defined as.the application of

scientific methods of investigation to the study of complex human

organisations and services.

In operational research, one is concerned all the time

with the activities of a group of people with the purpose of.

inducing beneficial changes. Thus, operational research is a

sociological science, and has an immense social content which

distinguishes it from pure or applied research. The main

objective of operational research is "to develop new knowledge

about institutions, programmes, use of facilities, the people

working in these activities and the individuals and communities

served by them,’ in order to secure optimal utilisation of

resources in men, material and money in the service of the

community." A new area of operational research is emerging, i.e.,

"health operational research.

PRINCIPALS:

^7

1. It is an omnibus,( iriterdisciplinary)that takes

to any branch of science.

2. ’One man with idea is as much as 100 having

merely interests.

3. It mistrusts verbal arguments and substitutes

aIgebric reasoning for verbal wrangling.

4. It believes "Problems are plenty but practical

actions available is restricted and so" get the

best of the worst bargain"

5. It often yields rather bad answers but improves

on exhisting worse ones.

6. It unmasks hidden incompatibilities in the

complex of organizational goals and targets and

chooses right priorities.

—pTSfessorT'Dep^ • °f Community Medicine “

. tr ?--dical Colleoc, Bangalore.

2

BIASES IM OPERATIONAL RESEARCH:

The procedure- to be adopted in operational research

differs according to the nature of the study. The usual procedure

adopted generally consists of the following phases.

1. Forru_ation of the Problem

2. Collection of relevant data, if necessary, by a

suitable sample

3. Analysis of data and formulation of hypothesis

4. Ferivlng solutions from the hypothesis or "model"

5. Choosing the optimal solution and forecasting

results.

6. Testing of solution, e.g., pilot projects

7. Implementing of the solution in the whole system.

COAWN OPERATIONAL RESEARCH TECHNIQUES:

I; Lingos Programming(L.P.) Often termed as an Optimization technique,

Linear Programme helps to achieve- the following:

a) To minimize the INPUT in terms of resources

b) To maximize the OUTPUT in terms of work done

c) To achieve an optimum "mix" of various resources

subject to constraints.

When the number of resources being studied to determine

the optimum "mix" (or proportion of each resource- to be- used) is

only two resources, then the 2-dimensional method may be employed as^'

described in the example. However, in reality, the number of

resources used arc- inevitably more than two in number.

For such

situations, there' are Linear Programming techniques that involve

multi-dimentional arrays. The- principle of calculation is simple

but the quantity of calculations to be cone becomes laborious and

time-consuming and therefore recourse to a computer is often

necessary.

Some examples of situations where- Linear Programming

techniques may be employed:1. Optimum 'mix' of various drugs in T.B. Chemotherapy,

keeping in view constraints of cost, availability,

potency, side-effects etc.

2. Optimum "mix' of medical/paramc-dical staff in a

Fepa^tment keeping in view constraints of salary

cost, job requirements, qualifications, experience,

patient needs etc.

3. Maximal coverage- with limited staff/other resources.

3

DR . DARA S AMAR

LINEAR : 'CGRAMMINJS (2-dimensional or

simplex method)

Problem:

Two types of protein foods (C± and C2) are being made for a

nutrition programme. C, is cheap.-but contains less protein

than C2 which is costlier. 'What-is the optimum mixture of

and C2 which will maximise the profit function(p) (profit values

measured in terms of grams of proteins).

P

=

2 x + 3y

(Where x and y are the respective number of units

of

each unit of

and CL,, to be mixed, given the condition that

has 2 grams of protein and C2 has 3 grams of

protein.

Thus we have to find out the optimum values of x and y that will

give the maximum value for p(profit) (i.e. maximum amount of

In other-words, for every unit of the cheap

protein).

food,

how many units of the costlier C2-food must be added, to get the

maximum amount of protein (i.e. what is the optimum proportion)

given the following constraints in 2 resources (c.g. two types of

raw material for

and C2.

TABLE OF CONSUMPTION OF MINIMUM RESOURCES

FOR C-j- and C2 foods

■

Units of Resources(R)

.

R1 = Material (.1)

’Minimum resources input per unit

o f Fo od C^

Minimum resources input per unit

of Food C2

Minimum total resources input

for 'x 1 units of Cl and 'y 1 units

of C2 (i.e. proportion)

= ^eriaF(2)

3

2

2

4

3x + 2y

2x + 4y

4

Constraints

(We cannot make just any type of proportion of

Cy and Cg (i.e. x & y) to give highest protein mixture because

of the following resource constraints)

material(i)

(1) The ceiling on

y

(i.e. Bl) for any proportion of

and C£

7 - i.e. 3x + 2y<_'(i.e. cannot exceed)

(i.e. x & y) is

7

(2) The ceiling on T2j) material (2)) for any proportion of

(i.e. x & y) is

e.

i.

and C?

.10

2x + 4y).£ (Cannot exceed) 10

Solution:

So we have 3 algebric equations :-

i.e.

i. 3 x + 2 y

ii. 2x

4y

i i i . 2 x 4s 3y

=

70

,Constraint Eouatrons

- io5

=

P

Profit function equation

Let us now plot the.constraint equations in a graph paper and

solve the profit function equation from the graph:

Graph Co-ordinates:

Eq.(i)

Let x coordinate be = 0

Eq.(ii) Let x coordinate be = 0

. * . 3x0 +- 2y = 7

2x0 +- 4y = 10

.-._y=7/2

• •. y = 5/2

Let y coordinate be = 0

Let y coordinate be = 0

3x + 2x0 = 7

.*

2x + 4x0 = 10

. x = 5

. ‘. x = 7/3

Co-ordinates for Eq. (i)

(xy) = (O,‘ 7/2)

)

(xy) = (7/3, 0)

j Eq. (1)

Coordinates for Eq.(ii)

(xy) = (0,5/2)

(xy) = (5,0

)

)

j Eq-

(11)

i- y axis.

To Optimise P=(i,e. Max, amount of protein)

Substitute the co-ordinates

values in Equation(iii) consecutively

at points 0, A, B, C and find out the point where the P value is

maximal.

Point 0:

0+0

Point B:

Point A:

2x + 3y = P

2x7/3 + 3x0 = P

14

. • . P=-±y- = 4.66

= P

P =_0_

Point C:

2x + 3y = P

2x + 3y - P

2x0 + 3x5_= P

2

• • P =15 = 7.5

2---------:

2xi+ 3x2 = F

•' • p ~JL_

-----

.

2x + 3y = P

Maximal Value of P - 8 (occurs at point b)

Substituting Co-ordinates of E in Eq. (iii)

2x + 3y = P

2(1) + 3(2) = 8

Optimum Proportion of

and

=1 unit of

for every 2 units of C„

6

II. PERT/CPM NETWORK ANALYSIS:

T. PET-T - acronym for programme evaluation and Review Tcchnioue,

It is a network or a graphic plan of all events and

activities to be completed in order to reach an one’ objective.

The- essence- of PERT is to construct an Arrow Diagram (refer example).

The diagram represents the logical sequence in which events must

take- place.

It depicts sone activities that may be- performed

simultanc-usly and other activities that can be- performed only

consecutively.

It is possible with such, a network to gain the

following answers:a) Fetermin.'ng the probability of meeting specified

deadlines in your programmes.

b) Planning, scheduling and monitoring the project.

c) Determining the latest and earliest starting and

finishing time deadlines for individual activities

and workers, keeping in view the deadline- for

completion of the entire- project or programme.

d) Better and more- specific job descriptions in a

project (i.e. number, kind and sequencing of job

activities)

c-) Continuous timely progress reports,.

f) An ideal system for evaluating the- project.

g) PERT identifies trouble spots, often in advance,

and pinpoints responsibility.

2, CPM - acronym for critical path method.

This is the Longest

path in the- PERT'Network, in terms of time taken to complete- theactivities.

If any activity along this critical path is delayed,

the entire project will be- delayed. Whereas PERT, only provided an

in depth, time- - analysis of the project, CPM helps to determine

a time schedule- at minimum cost, i.e: it helps in calculating

the OPTIMUM cost that needs to be incurred if the project is.to

run at the- Optimum duration.

Thus PERT and CPM arc- tools in dealing with the- TIME

and COST analysis of a project.

Examples of PERT/CPM usage cover all activities of a

Medical College- extending from the administrative procedures to

•teaching time schedules, departmental programmes, laboratory proced-ures,"patient care systems, rural and urban health programmes,

planning for research projc-cts etc. A few areas that are'small enough

for PEIv/CPM trials:- a) An immunization camp b) planning for a short •

course/training programme c) organizing a new department d) upgrading

a unit (c-) movement of vehicles during a normal week of college work

7

•

r--l.■‘'•■nino

work tv

■

'.'chedulc- for

7

NETWORK-EASEF TIME ESTIMATES FOR VACCINATION

PROGR/tMME

Predecessor

Event

Successor

Event

1

2

1

3

2

V

3

4

4

4

Survey the population

'Prepare policies and pro

cedure for records and

re po rt s

te E.S. E.F. L.S. L.F.

( days )

17

0

17

0

17

5

0

5

52

57

8

Prepare estimates of

vaccine, equipment, vehicles

’ 8

etc. required

17

25

21

29

17

25

17

25

6

Procure vehicles on loan

from other departments and

got them into position

7

8

53

57

69

Got the forms printed

Plan public meetings

9

Plan strategy to obtain the

cooperation of community

leaders

Orient vaccinators with

respect to project, plans,

jobs, etc.

4

5

■2

2

Activity Fescription

10

Get the vaccinators into

postition

16

12

4

17

33

5

25

17

29

29

69

33

2

25

27

47

49

3

25

2

18

25

25

28

27

43

55

51

25

58

53

43

28

27

32

44

58

53

62

43

Z4

48

43

70

48

72

48

69

29

27

6972

68

72

69

33

49

69

72

72

72

5

5

11

12

Place an order for vaccine

Call tenders for equipment

10

13

11

14

Assign population and post

vaccinators

Receive vaccine

12

14

15

17

Give- contract for equipment

4

17

£=,

Toliver vaccine at FHC

2

15

16

17

Receive equipment

Feliver equipment at PHC

Conduct public meetings

Motivate community leaders

21

3

16

8

17

9

13

17

17

17

J-8

18

19

19

20

39

23

48

46

Help vaccinators to develop

rapport with the- community

Vaccinate

Review performance

10

11

S

32

72

42

83

62

72

72

83

83

91

83

91

Prepare project report and

submit

8

91

99

91

99

E.S.= Earliest Start; E.F.= Earliest Finish; L.S.--- Latest Start;

L.F.=Latcst Finish

70

9

III:

QUEING

THEORY

The above technique c'eals with questions relating

to the following

1. Types of Ques

2. Factors in Que formation

3. Minimizing Que lengths.

There are different types of Ques and each is governed

by such factors as Que discipline., Service capacity etc. The

following is a simple Que system based on the "First come - first

Serve" Easis. The formulae relate to the calculation of certain

important parameters in Que Control.

Example:

A given out patient department of a Hospital, functions

for 8 hours per-day(H'). Eased on a sample survey of this OPD, the

following figures were calculated

(A) Arrival Rate of patients joining the OPE Que =4

patients/hour

Number of doctors serving OPE '

.

=1

(S) Service Rate of patient(i.e. No.of patients ±5

patients/hour

that doctor sees in an hour)

. ’.(W) No. of patients waiting in Que at any

given moment

o

=

= __ A_

,

S(S-A)"

9

4 _ = A-_?

5/5-4)

.‘.Average waiting time per patient = '7

”’a~"

= 3 -2 - 0.8 hours

' 4 ’

or

48 minutes

.‘.Total No. of patients in OPD Area

(i.e. No. of patients waiting outside

+ No. of patients being seen by Doctor )=y

=

A

=

4

S _ A~ 5-4

Service time of Doctor (i.e. No. of hour^lhe

Doctor is actually

.at work).

Idle time of Doctor = (H-

j

—g—'

'= 4 patients

4 xS_g_4 hours

—-g-or

hours 20 mins.)

8-6.4

= 1.6 hours

or

1 hour 36 minutes

11

IV.

1.

MO'ITE CATLO SIMULATION .

.'leant to be- i

_or solving problems too expensive for

experimental solution and too complicated for analytical

treatment.

2.

Many real-life systems are so complicated that it is all

but impossible to transcribe them in mathematical equations

or to solve the equations even if they could be so trans

criber’. -'Therefore in such cases, a step by step verbal

description of the sequence of actions is often possible.

It is such situations that Monte Carlo Technical simulation

has been designed to handle.

In particular it provides simple

possible solutions for queing problems which are otherwise

intraitablc-.

3.

Monte Carlo simulation is a recent operations-research

innovation. The novelty lies in making use of pure chance

to construct a simulated version of the process uncer

analysis, in exactly the so.ne way as pure chance operates

the original system under ’working conditions.

4.

The essence of Monte Carlo simulation is to use random-number

tables to reproduce on paper the operation of any given

system under Its own working conditions.

5.

The selection

? such a random sample is the heart of

Monte Carlo method»

6.

One way of avoiding the tedium and fatigue of an enormous

number of trials is to resort to computer simulation.

7.

A moderately fast’ computer could simulate withing one

minute 100 trials, and a really high-speed one as many

as 5,000 trials.

8.

The accuracy of a Monte Carlo approximation improves only

as the- square- of the number of trials. To double the

accuracy of the estimate the number of trials, has to be

quadrup led; to treble it they must increase ninefold,

and so on.

9.

It is often an adequate substitute for the purely

mathematical formalism and enables us to predict not only

the number of customers likely to arrive during any stipu

lated period but also the very instants at which they do.

12

V. IWEFTOFA—COiHROL:

This is a technique in the- realm of

materials management. The technique helps to solve the- following

problems in the stores and purchase sections for Drugs, Stationary,

Instruments, linen, furniture, lab-reagents vaccines, catering

section etc.

a) Whether to buy all at once or at intervals (analyses demand)patterns

b) Whether to hold buffer stocks and if so how.much (considering

budget limitation, utilization rates etc.)

c) Calculating probabilities of shortage- of individual items in

stores and therefore making alternative plans.

d) How many orders to place per unit time (e.g. per month) taking into.)

consideration delays due to quotations, administrative- lag time ,1^

Delivery lag time etc.

e) Calculating Optimum quantity of goods to order keeping in view

that bulk orders cost less per unit than frequent small orders.

(Refer diagram below)

Optimum

Cost

C

?

i

T;

I

QUANT ITY

Optimum Qt-;

AT LAS idlL- E OPERATION RESEARCH TEC1I ' QUE

HEED TO BE APPLIED

13

Review of currently available literature

.Operations Research studies in the field of Health Services,

reveals a predominance of hospital bo see

*

studies.

However, even

those studies arc confined to a few’large hospitals only. The

following is a list of components in the Health Services system

provided by most medical colleges that may be subjected to

Operations research in order to improve their fur.ctioning.

Many

of these components have- already been studied and some others

are- in the process of being studied. However as mentioned

earlier, data on such studies arc limited.

1. Activity analysis of various categories of workers in the health

care system.

2. Studies towards determining the norms of work-load in terms of

quantum and range of services to be provided, population to be

covered etc., for different categories of health personnel at all

levels.

3. Studies on rationalization of staffing patterns keeping in

view the work-load.

4. Utilisation and maintenance of physical facilities, equipment

and vc-hi.clc-s in all the institutions of health care system.

5. Utilization of hospital beds.

6. Studies on waiting time problems in hospitals and health centres.

7. Studies for development of systems for indenting, storage and

retrieval of medicines and drugs (inventory control and materials

planning).

8. Studies for optimal scheduling and deployment of vehicles

(net work) for rural health services.

9. Studies for scheduling and deployment of vehicles for

emergency services.

10. Scheduling of patients in outpatient departments of hospitals

and health centres.

11. Scheduling of Operation Theatres.

/

12. Inventory control system for X-ray, Laboratory materials,

stores, blood bank etc. in hospitals.

13. Eic-t planning in hospitals.’

14. Studies' on allocation of resources in terms of beds, nurses,

Operation Theatre time etc. to different specialities.

15. Cost

analysis of health care activities.

16. Cost analysis of different hospital services.

Cost of training of different categories of health workers

including professionals.

14

18. Economics of scale- in hospitals, medical colleges and

schools for nursing anc’ other categories of health workers.

19. Cost-benefit analysis anc’ cost-effectiveness analysis of hospital

services.

20. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different training programmes.

21. Studies towards development of suitable management information

systems for individual hospitals and health care institutions.

22. Feasibility studies for introducing 'performance budgeting.

23. Studies in quality of health care services towards development

of standards for quality of health care.

24. Studies in quality of medical care in hospitals.

25. Patterns of private expenditure or health care services by

the population.

W

26. Studies on optimum span of control for different levels of health

services organisation.

SOME COR'CL' JSIOMS

1.

Operation Research is a betterment of exhisting "plans" and so

can be called a scientific criticism of exhisting organization.

So the Operation Research man has to be careful in putting his

ideas across and be very "TACTFULL".

2. Results of Operation Research must he done fast as it relates to

"exhisting and now" condition and not some future. Therefore it

is ever changing and dynamic.

3. Most of Operation Research is "Common Sense" and therefore

requires only basic mathematical reasoning (mostly algebra)

4.

To make use of Operation Research, it neecs "courage" as one

has to "change" age old so called "safe" traditional methods.

5.

Most of us use Operation. Research daily, without even being

aware of it.

*

EVALUATION - THE KEEP, ITS VALUE AND

METHOD

By Dr. Dara S Amar.

1.

'That is Evaluation?

Evaluation, in lay language, would mean the separation of the

most valuable from the less valuable and the value-less.

Evaluation measures

1.1 The degree to which objectives and targets are fulfilled

1.2 The quality of the results obtained

1.3 The productivity of available resources in achieving

objectives

1.4 The cost effectiveness achieved.

Evaluation makes possible the reallocation of priorities and

resources on the basis of changing health needs.

2.

Types of Evaluation:

2.1. Pre-evaluation: It is necessary to establish a baseline at

the beginning of a programme against which tc measure the

results.

2.2 Concurrent evaluation: Evaluation should not be left to the

end but should be made from time to time, so that if the

programme is not progressing successfully, modifications can

be made.

The programme moves thus:-

2.3 Terminal evaluation: The evaluation of the ultimate achievement

of the programme in terms of objectives and sub-objectives

fulfilled and the extent of planned activities carried out.

Evaluation may be approached from the following angle too:

2.4 Evaluation of structure and organization.

2.5.Evaluation of the Process

2.6.Evaluation of the results.

2

3. Tools usee1 for Evaluation:

3.1 Observation schedules

3.2 Records and registers

3.5 Health Examination

3.6 Discussions

3.3.Work diaries

3.4 Personal interviews

3.7 Questionnaires.

4. Provision for Evaluation in your programme :

The following provisions must be made at the stage of

planning itself.

4.1 Person responsible for evaluation should be specified.

4.2 Amount of time, the personnel can give for evaluation work.

4.3 The funds available for evaluation

4.4.Stages of the programme at whichevaluation will be done

4.5 Is there a provision in the planning, for making either

major or minor modifications in the programme, depending on

the "feed-back" from the evaluation.

5. The process of Evaluation :

A systematic procedure should be followed in evaluating any

programme. The theoretical concept of evaluation is relatively.

simple but its practical application can be very difficult,

too often, these difficulties have been used as excuses for not

starting, but the right approach ’ is to begin; for onee begun,

experience, techniques, and data grow rapidly.

It is better

to start even if only with the evaluation of a few aspects of

some activities of a programme, than never to have started at all.

The basic steps in evaluation are as follows:

i) Statement of objectives

'

ii)

Establishment of Easeline Data

iii) Measuring coverage and Uti

lization of services

iv)

Evaluating utilization of

Resources

v)

Evaluating Activities and Atti

tudes of the programme

staff and public

vi) Measuring effectiveness

of programme

vii) Measuring efficiency of

■ programme.

viii) Collection of Tata

ix) Analysis of Data

x) Presentation of Results

and Recommendation.

. . .3

3

5.1 Statement of objectives:

Since evaluation is related to and dependant on objectives,

the statement of objectives must be.sufficiently specific to be

measured.

In fact, the more- specific the objectives, the better

the evaluation.

Two levels of objectives are distinguished.

a) General objective (or aims) which may or may not be

measurable.

•b) Specific objective which are measurable.

General objectives only sc-t out the main intentions but not the

details.

edj; To provide preventive, promotive and curative health

services to the community.

Specific objectives set out measurable details.

The following

are the criteria for making specific objectives.

"primary

/*

vaccination" of all child-?5.11. A clear definition os what is to be attained; for example,/

*

Gn

before they are six months of age.

5.1.2.

A clear statement of the amount or degree of intended

attainment; for example, 100% of the children must

have primary vaccination before, each child is six

months old.

5.1.3

5.1.4

5.1.5

A clear statement of the time in which this degree of

attainment; is expected; for example, "between I July

and I September 1963".

A clear specification of the geographic location of the

programme; for examplej Eata Village.

A clear specification of the particular people, or the

portion of the environment, in which the objective is

to be attained; for example, the parents of all children

under six months of age should have these children vacci

nated .

The objective might read, "To persuade parents of children

under six months of age in Eata village to have all these

children (100%) vaccinated between I July and I September 1963".

Sub-objectives might include the following:

I) "To carry out a house-to-house survey of the village

in order to list the names of all the infants under

six months,"

2) "To identify leaders especially among the women who can

assist with this survey."

The programme's success depends on accomplishment of the

sub-objc-ctivc-s . Sometimes a sub-objective.may not be

directly related to health.

If the objective were "To get

50% of the restaurants in a given locality to reach a speci

fied level of cleanliness in one year", one sub-objectivcmight be "To have restaurant owners buy new uniforms for the

staff".

’

4

542 Establichnc-nt of baseline- Tata:

4 Often termed as "pre-c-valuation", it measures the- current

Health Status and no-cds of the community so that those may be

comparer’ again at the- one’ of the programme in order to measure

the chances in health status and fulfillment of the needs of thccommunity.

The Health Status of the- community is usually studied by

collecting data on:-

i) Age/Sc-x distribution of population

ii) Mobility of population

iii) Socio-economic levels and factors prevalent

iv) Birth Bate

V) Bcath Rate

vi) Morbidity Rates

'

(

vii) K.A.P. Surveys.

The needs of the community may be ’

PERCEIVEP needs(i.e.

the people themselves perceive the need for the programme) and

PROFESSIONAL needs (i.e. what the- medical professionals believe

are the needs of the- community).

Lost often both the needs

arc- beyond the- capacity of the resources available for the

programme, Whereas the change in the Health Status of the

Community at the end of the programme, can be measurc-d quantitatively,

the measurement of the "fulfillment" of the needs is often quali

tative and therefore subjective. Nevertheless, ~n effort must

be made, since without the Easelinc- data, evaluation cannot begin.

5.3 Measuring Coverage- and Utilization of Services:

’

This is often referred as measurement of the "adequacy" of

the programme-.

The- three components measured here are:

i) Geographical coverage

ii' Population coverage

iii) Utilization rate of the programme services.

5.3.1

Geographical coverage:

This refers to the geographical

distribution of the- people- who make- use- of the- programme

services c-.g. Catchment area of a hospital.

If the

geographical area of coverage is large, it could mean

. . .5

5

i) Your programme is popular

ii) Your programme- .is more- of a specialized nature- which is

generally not available.

5.3.2

Population coverage:

This refers to proportion of the

whole- copulation, who are eligible for your programme services.

If your programme is specialized, the coverage is low (co. only

maternity services) but if your programme- is of a general nature

(e.g. Community development projects) the coverage is often 100%.

5.3.3

Utilization Rate: Not everyone eligible for your programme

service, will necessarily use- your services, therefore it is

necessary to measure the proportion of the _eli.q ibl e population

who make use of your services.

5.4 Evaluating utilization of Resources:

Resources are men, material, money and time. These

form the inputs that is consumed or utilized to produce thcoutput of the programme.

Merely because resources are consumed

rapidly, doc-s not signifiy that your programmes is progressing

equally rapidly. What needs to be evaluated or measured, are

the following criteria.

5.4.1

Quantity of Resources available/uscd.

5.4.2

5.4.3

Quality of Resources available/uscd.

Fate of utilization of resources in relation to

programme phascs/duration.

5.4.4

Eistribution of Resources

(The use of resources in measuring the EFFECIENCY of a programme

is denoted later)

Evaluation of resource utilization ar>4

its optimization

can be carried out using techniques in the realm of operations

Research, cost effectiveness studies etc, which arc beyond the

scope of this present paper.

5•5

5.5.1.

Evaluating Activities and Attitudes of

Activities:

staff one Public;

These arc- the number of items, of work (eg.

vaccinating children, making home-visits, registering births etc’)

The evaluation of the activities, to measure their usefulness

/time in terms of the/spent pc-r activity per worker, outcome of

activity, sequencing of activities etc. arc- termed as work study

analysis.

This is a specialized technique.

Another technique

6

that may be- usc-d is the 0 and M technique or the- organization

and methods evaluation which measures such matters as division

of work, delegation of authority, co-ordination, etc. Another

type of activity analysis which is incrc-asing/used

the

P.E.R.T./C.P.or programme evaluation Review Technique-/

Critical path method in Operations Tc-search. Retailed

reviews of the above techniques arc available in specialized texts.

5.5.2 Attitudes: This is most often ignored in any evaluation,

mainly because of its difficult and subjective nature. Thc-

tc-chhiques employed are usually in the form of questionnaires

that arc- framed to provide unambiguous replies and the method

of filling the qucstionaircs is through direct personal

interviews and discussions. However, unless the people are

well informed and sufficiently knowledgable on the matter, most

of the responses are guarded, generalized and do not reflect

true attitudes of the people. Though very difficult and subjective,

the technique of direct observation combined with the above.

technique, aids in arriving at a fair diagnoses of the changes

or otherwise of the attitudes of the- people towards .the

progress of your programme:

5.6

Measuring Effectiveness of the programme:

Very often, due to constraints on resources and often

due to faulty management, many of the objectives planned $•

*

at all or only partially so. Measurement of the EFFECTIVE TESS,

using the following proportion formula, often serves as a

rough guide to y>ur achievement.

prog?amm^ 1^or'Sft?ntn§t

**

accomplished

Effectiveness = No. of objectives actually achieved

No. of objectives originally planned.

To have an idea of the extent of individual objectives achieved,

the- percentage coverage of each objective may also be- calculated.

(3

5.

Measuring efficiency of the Programme:

This constitutes the most important factor for evaluation

of your programme, as far as your funding agency is concerned .

It relates your programme output to the money spent fortho

programme. However,.since money is not the on±y import.nt

consumable resource, the following proportion formula must beindividually calculated for monc-y, materials, men and time .'I

7

Efficiency i No. of objectives actually achieved.

Total cost (direct & indirect)

actually expended.

5.8

Collection of Tata: So far, we discussed WHAT data to collect

for evaluation of a programme. The following points constitute the

main criteria in the actual methodology of collecting the data:i) How should the date be collected

ii) When should the data be collected?

iii) From whom should the data be collected?

iv) By whom should the data be collected?

5.8.1.

How-------: This is usually in the form of a health

survey for which there are 4 approaches :

i) Using exhisting records/registers for gathering data.

ii) Using Questionaires containing unambiguous and well

structured questions.

iii) Personal interviews and discussions

iv) Health examination of individuals.

5.8.8.

When------------ ?: Two points to be remembered are

i) Season of the year: eg. If the base-line data ia collected

during an epidemic of choldra, the morbidity rate will be un

usually high.

ii) Evaluation procedure: Is the data gathering a continuous

procedure throughout the year or is it episodic?

It is preferable to collect basic data continuously (to overcome

problem(i)) but a more detailed data collection must be carried

out at predetermined intervals.

Thus the workload of the data

collecter is not- continuously overburdened.

5.8.3 From whom.--------?: Obviously, larger the number of sources

and people from whom data is collected, better would be the

evaluation. However, practical constraints in resources may

necessiate the employment of SAMPLING TECHNIQUES. Thus

"populations at risk" may be measured first due to the economy

achieved.

If, however, your programme is a unique- and

innovative type, then a group of matched CONTROL population .

must be simultaneously studied in order to claim the unique .

benefits of your programme.

.8

8

5.8.4: . By whom-------- ?: This is entirely dependant on the

resources available for your programme. A lot of project

leaders feel that an independant group of staff, not involved

with the programme, must do the evaluation in order to avoid

any biassed opinions. Though this method may be theoritically

sound, its practical implication can be often futile and

useless. The reason being that many of the project workers

"feel” that an "outsider" knows little about the actual

conditions of work and so his evaluation and recommendations

arc not always right.

In order to avoid such "discontent"

in the organization, a PART of the evaluation team must

consist of the project workers (actual field- workers and

NOT project lc-aders/consultants.')

so that a balanced opinion

and analysis is made.

5.9:

Analysis of Data:

Before analysis, the data must be

"collated" ie : checking of completeness of data and sequencing

and tabulation of the data collected. The work of collation

can go on simultaneously with data collection and not be left

to the end t

The amount and type of analysis required will depend on the

problem and complexity of the programme and can vary from simple

tabulation to complex analysis of multiple variants.

The

services of a statistician is often required.

6.

Presentation of Results and Recommendations:

The presentation of the evaluation report depends upon for

whom it is sent.

If it is to the project agency, then it must

contain all details but if it is for publication then-a lot of

summarization is required. The report should, however, generally

follow the criteria stated below.:

6.1 Be brief as possible

6.2 Results must be tabulated simply

6.3 Emphasize practical implications

rather than theoritical discussions

6.4 Emphasize improvisations especially

for field workers.

6.5 Make clear, practical recommendations.

6.6 Illustrations in the form o-f graphs etc.

should be used.

9

6.7 Figures in tables must not be repeated in the text.

6.8 The FORMAT of the report should be as follows:

- Summary of Report

- Aim of Evaluation

- Methods used for Evaluation

- Results in the form of tables/graphs etc.

- Discussion of results of evaluation

- Recommendations.

7.

Common difficulties in Evaluation:

7.1 Demands and needs often exceed resources and so evaluation

results are often discouraging.

7.2 Inadequate planning, especially for evaluation, before

start of programme.

7.3 Lack of expertise.

Evaluation requires expertise in such

fields as social medicine, statistics, sociology, social

psychology, economics, administration, computer science etc.

Qualified people are thus scarce.

7.4 Techniques and -terminologies in evaluation procedures are

strange to programme/projc-ct staff and so they are often

distrusting and uncooperative. Some terminologies have

forbidding names but are basically simple d-g. cost-benefit

analysis, network analysis, simulation, management audit,

resource allocation model etc.

7.5 Methodological difficulties.

For example, many health

programmes cannot be measured in quantifiable terms and

their benefit to the- people are often subjective, general

rather than specifig and have subtle effects that cannot

be measured.

7.6 Due to the pressure of day-to-day work of the programme,

the "demands" to analyse, record, compile, measure activities

etc. "seem" to be an additional burden.

HOWEVER IT MUST BE REMEMBERED THAT THE OBJECTIVE OF

EVALUATION IS NOT TO CONDEMN OR PRAISE, BUT TO SIMPLY STATE

FACTS SO THAT THE PROGRAMME MAY BE

SUITABLY MODIFIED TO

GIVE ITS BEST TO THE PEOPLE FOR WHOM IT SERVES.

<2. o m H <-+- < j

SOURCE : DEVELOPMENT COMMUNICATION REPORT

H£»KIWG A SPLASH:

- 1991/1

HO’J EVALUATORS CAN BE BETTER COMMUNICATORS

by Michael Hendricks

IF a tree Falls in the forest and one hears it, did it

make a sound ? IF an evaluation report Palls on someone’s

desk and no one reads it, did it snake a splash? Kone whatso

ever, yet wa evaluators still rely too often on long, JargonFilled texts to ”communicate” our analyses. Findings, and

reconmsndations. Ue can, and must do hotter.

Uhy? Becauso the only reason for doing evaluations is to

make that splash, to have that impact, to change situations in

s desired direction. Some call this ’’Speaking Truth to Power”

but what good is speaking Truth if Power isn’t listening ?

Unless wo help our audiences to listen, all our good works will

go for naught,

Ue can do batter in at least two ways. First, we can employ

mars interesting techniques to communicate our findings, thick

reports simply won’t work anymore, if thsy oeer did. Second,

we can remember a few guidings, principles to enhance all our

messages. Let’s first consider some better techniques:

FI HAL REPORTS

L’lf ua must produce Final written reports ( and surprisingly

often these reports are not required), then for everyone's sakeB

let’s make them:

-

shorter: no more than 15 to 20 pages per report, and

always with an executive summary?

-

more truc-to-liFe: perhaps including direct quotes,

personal incidents, short case studies, metaphors and

analogies, and especially photographs whenever possible?

-

mor® powerful:

using active voice and present tense,

Featuring the most important information first, and

using the sorts of graphics discussed beloujpnd

-

visually appealing : using modern graphics dsaign

principles, desktop publishing, and high-quality materials.

OTHER WRITTEN PRODUCTS

In addition to fins! reports, other written products can

be even more useful. Draft reports, for example, can be especially

effective, precisely because they are still subject to change. I

sometimes deliberately include material in a draft report that I

have no intention of including in a final report, usually to raise

sensitive or oven cantrovarsfai issues that are not receiving

enough attention.

- 2

Other written products include interim progress reports,

talking papers, question-and-answer statements, memoranda,

written responses to other speeches, press releases, "op ed"

items in newspapers, speeches, written testimony, newsletters,

and even articles in association or professional journals.

In

short, we evaluators have plenty of opportunities to present our

findings, but we must be more creative at using these opport

unities .

GRAPHICS

Using graphics is not a presentation technique by itself,

but they are so useful they deserve special attention. Pie

charts, historical timelines, maps, small multiples, and picto

graphs are an effective communication technique for several

reasons. They allow a large quantity of data to be displayed

and absorbed quickly, they reveal patterns not otherwise apparent

they allow easier comparisions among data sets, and they can have

a strong impact. Furthermore, we can use these graphics not only

for presentations to audiences at the end but also to help guide

our own analyses as we progress.

However, a book on "How to lie with Graphics" could easily

include sections on clutter, incorrect proportions (especially

by the gratuitous use of three-dimensional effects), an over

emphasis on artistic effects, broken or shifting scales, and

failuer to place findings in perspective or to adjust accordingly

Anjj of these errors could easily confuse or even mislead our

audiences, so graphics must be used carefully.

Two overall suggestions might be useful. First, remember

that selecting the proper graphics is not the first step in

moving from data to graphics. The first step is for you, the

evaluator, to determine your message. Uhat specific point do

you want to taake? A second suggestion is to maximize the amount

of "graphic ink" which presents actual data and to minimize the

amount which presents grids, titles and legends.

Unfortunately,

too may pgraphics are now cluttered with extraneous ink.

PERSONAL BRIEFINGS

Briefings are almost always more effective than written

reports for presenting evaluation findings, and they should

almost always be used. True, they can be risky, since a poor

presenter, poor selection of material, scheduling delays, audience

moods and external events can effect the presentation.

( I once

saw a single briefing interrupted three times by phone calls

from the White House). But the strong advantages to briefings

than offset these risks.

For example, briefings involve all relevant actors in a

common activity, allow these actors a much-needed forum for

discussion, and create a certain momemtum for action.

Most importantly however, briefings fit the way managers

normally operate. Managers rarely sit and read documents for

long strectches of time, so why should we ask them to change their

management s^yle for us ? Instead, we evaluators need to tailor

- 3 -

our communications to fit our addience’s

briefings vit very nicoly.

style, and personal

To plan an effactive briefings, limit the audience to a

select group, select only the most important information, pre

pare 6-10 large briefing charts (or overhead transparencies or

slides if you prefer), selsct a team of one presenter, one assis

tant, and oio high-level Hasten with the audience, study the

audience’s interests and likely questions, and practice, practice

practice-exactly as you plan tn present the briefing and using

a stop uatch.

To conduct an effective briefing, distribute materials in

advance, don’t overlook the lighting and seating arrangements,

immediately grab the audience’s attention, avoid using a micro

phone or notes, provide individual copies of ail briefing, this

means that the formal presentation should finish within 20 minutes

the remaining 40 minutes are for general discussion, the first

and most important purpose of a briefing.

OTHER TECHNIQUES

All evaluators use written reports and personal briefings

to present our findings. But how many of us use less traditional

techniques that may be even better at feeding our findings into

ongoing decision-making?

I once worked for the Inspector Gerwral{IG) of the US Depart

ment of Health and Human Ss;vices, helping to supervise national

level evaluations. The IG, as part of his normal routine, regu

larly held one-on one private lunches with the Secretary and other

top agency officials. Naturally, we wanted him to discuss our

evaluations at these lunches, but it was unrealistic to expect him

to carry along a progress report.

So we began providing the IG with one pocket-sized index card

for each of the evaluations which might bo relevant for his

luncheon partner. Because these cards were convinient, the IG

looked at them on the uay to lunch, and he usually found ways to

interject our information into the discussion. As a result, top

agency officials routinely discussed the IG’s evaluations, not

just an special occasions.

Carefully selected comments at relevant meetings or ’'chance”

hallway encounters can also be useful, and more modern methods

include videotaped and computerized evaluation presentations.

The US Food and Drug Administration, for example, uses computer

graphics to present captivating on-acreen slide shows. In addition

to allowing professional uipos, fsdes, and other transitions, this

program allows an evaluator to build text charts line hy lino,

make the bars of a bar chert grow, and add th® slices of the pie

one by ono. This technique also allows an audience to view the

message over and over, and at his or her leisure.

With these different presentation techniques in mind, let’s

now consider six guiding principles for using these technique most

effectively!

k -

Remember that the burden for ©FfectivRly communicating

out Findings is on us, the evaluators,not on our audiences.

It is out responsibility to convey our messages, and it is

our Failure when this dogs not occur.

“

As thoreau would say” Simplify, Simplyfy." Our typical

audience is usually very busy and balng pulled in many=

different dicectiona, so wg need to para ruthlssaly to

reach our few points. IF thesa create interest, we can

always Follow-up with moro dataila.

—

Know the audience. Go ths homework nocasoary to learn

their backgrounds, interests, concerns, plans, petpeeves,

etc. even somathing as simple as selecting examples From

the home region of a key atiduencs member can help maintain

interest in s report or briefing.

-

Be action-oriented. Bur audiences are rarely interested in

background knowledge; they almost always want information

that will help them right now. Often this requires ub to

offer the time effective rueuwmendations For actions by

taking th-a time to establish a receptive

*

environment and

than carefully develop, present, and Follow-up on our advice

Use multiple communication techniques. Bather then limit

ourselves to one technique or another we can produce several

written products, gibe a personal briefing, develop a Screen

Show presentation, produce a videotape,otc- all filled with

powerful graphics and helpful recommendations.

-

2a aggressive. Instead of waiting for the audiences to

request information, we must actively look for chances to

present cur Information. This implies that we will communi

cate regularly and frequently, appear in person if at all

possible, and target multiple reports »nd briefings to

specific audiences and or issues.

In conclusion, w evaluators can be nnormoualy useful in

many diffarnnt way®, but only if our findings have an lapact. Hou

w© communicate our findings is often the dif Forans

'

*

between creat

ing - tiny oaoripple or making a us-up.er -sel-ssfi.

SCORE SffFT FOR W STUDY 'IF VALUES

DIRECT!QNS :

1 • First make sure that every question has been answered.

Note: If you have found it impossible to answer all the questions,

you may give equal scores to the alternative answers under

each question that has been omitted; thus,

Part I.

for each alternative.

(b) must always equal 3.

The sum of the scores for (a) and

Part II.'2-4 for each alternative. The sum of the scores for the four

alternatives'under each question must al ways equal 10.

2. Add the vertical columns of scores on each page and enter the total in

the boxes at the bottom of the page.

3.

Transcribe the totals from each of the foregoing pages to the columns

below. For each page enter the total for each column (R, S,T, etc)

in the space that is labeled with the same letter. Note that the order

in which the letters are inserted in the columns below differs for the

various pages.

-------

Page

j

Totals

Theore

tical

Economic

I

Aesthetic

The sum of

i

the scores for

each row must

eqial the

figure given

be low.

’olitical

Reli

gious

(X)

(Y)

(T)

(z)

(R)

(Y)

24

24

JSocial

------- ------

PART 1

(R)

(T)

(x)

(z)

(s)

(s)

■ (T)

(S)

(X)

(Y)

(R)

(z)

(I)

21

Page 7

(Y)

(T)

(s)

(z)

(R)

(X)

60

Page 8

(T)

(z)

(r)

(Y)

(x)

(S)

50

9

(R)

(s)

(t)

(X)

(Y)

(Z)

4»

(s)

Page 3

(R)

(z)

Page 4

(X)

Page 5

Page 2

(Y)

21

Part H

Page

24»

Total

Correction

Figures

FINAL TO TAI

+2

-1

-4

-2

+2

-5

240

......

-2 -

4.

Add the totals for the six columns.

figures as indicated.

5.

Check your mark by making sure; that the total score for all six columns

equals 240. (Use the margins for your additions, i'f you wish).

Add or substract the correction

A

1- Extent of inequality in the world today;

a. In 1850, 3/4 of the world's population possessed 5/8 of the

world's wealth.

In 1975, 2/3 of the world's population possessed l/S of the

world's wealth

b.

Whence came this uneven distribution of the world's resources?

"The tilting of tne balance in favour of the West has come about

in the last 130 years. ......through the gun, through colonial plunder,

slave trade, slave labour, child labour, racial discrimination, the

creation of a dispossessed proletariate, and the destruction of the soul

and life-style of many peoples."

(S. Rayan)

c. The growing gap between the rich nations and the poor had

already been pointed out by Barbara Ward in the 1950's but the gap

continues to widen;

"Today'85% and tomorrow 90% rot in misery to make pcssible the

economic comfort of 15% today and 10% tomorrow"

,

( Heder Camara)

d. The result of this inequality is the ABSOLUTE POVERTY of

millions in the "fourth" world:

- 1/3 to 1/2 of tho t wo billion human beings in Asia, Africa

and Latin America suffer from hunger and malnutrition.

- 1/5 to 1/4 of their children die before their fifth birth

day, and millions of those who do survive lead impeded lives, due to

brain damage, stunted physical growth and sapped vitality due to

undernourishment.

- The life expectancy of the average person is twenty years

less than his counterpart in tho affluent world; that is, he is

denied 30% of the life-span of one born in the developed nations;

he is condemned at birth to an early death.

- 800 million of those people arc illiterate and, despite

continued expansion of educational opportunities, even more of their

children are likoly to be so.

e.

Julius Nyerere, President of Tanzania, has warned the rich

nations: "Poverty is not tho real problem of tho modern world, for

we have the knowledge and tho resources wbioh will enable us to over

come poverty.

The real problem of tho modern world, the thing which

creates misery, wars and hatred among men, is the division of mankind

into rich and poor".

f.

It is not so much the question of some having more to eat or

better clothes to wear, while others cannot provide even the basic

requirements; it is rather tho power that this wealth gives to some

to dominate, to oppress and to exploit the others.

in so .doing,

the rich and powerful justify themselves: "We deserve this wealth

and power: we have put our God-given talents to use and have worked

hard.

If the rest of the world is lazy, shiftless and ignorant,

!'•_ can't help that."

-22.

Extent of inequality in India today:

a. While we often and with some justification, blame all our

problems on the greediness of the affluent, developed nations, the

same ever-widening gap between the "haves" and the "have-nots"

appears here even

bo Within'our population of upwards 600 millions of people,

roughly 250 million live below the "poverty line", that dividing

line that demarcates bare minimum of survival for an individual.

This is the bottom 40 per cent, another 250 million live just

above the"poverty line" of human survival, the remaining 15-20

per cent, in an ascending pyramid represent the wealthy, dominant

classes with power, position and quality education: the raw mate

rial for further exploitation of the others.

c. In rural India, the top ten per cent own 50^ of the land,

while the bottom 50 per cent own 4^,; top ten per cent get 1/3 of

annual income of the nation,while the bottom 50^ get less than

this amount for all of their numbers. 0.1^ of the population owns

more than half the wealth of the area.

d. The poor are organised, without political power, and are

taken advantage of. A slum dweller admits: "Even to get a

sweeper’s job, we have to pay a bribe of Rs.200/-"

e. The very poor (bottom 40 percent) have less than Rk-,4j/- per

month to spend.

Most cannot read or write.

A

1- Extent of inequality in the world todays

a. in 1850, 3/4 of the world's population possessed 5/S of the

world's wealth.

In 1975, 2/3 of the world's population possessed l/S of the

world's wealth

b.

idhence came this uneven distribution of the world's resources?

"The tilting of tne balance in favour of the West has come about

in the last 130 years. ......through the gun, through colonial plunder,

slave trade, slave labour, child labour, racial discrimination, the

creation of a dispossessed proletariate, and the destruction of the soul

and life-style of many peoples."

(S- Rayan)

c. The growing gap between the rich nations and the poor had

already been pointed out by Rarbara ijard in the 1950's but the gap

continues to widen:

"Today 85% and tomorrow 90% rot in misery to make possible the

economic comfott of 15% today and 10% tomorrow"

(Heder Camara)

d. The result of this inequality is the ABSOLUTE POVERTY of

millions in the "fourth" world:

- 1/3 to 1/2 of the two billion human beings in Asia, Africa

and Latin America suffer from hunger and malnutrition.

- 1/5 to 1/4 of their children die before their fifth birth

day, and millions of those who do survive lead impeded lives, due to

brain damage, stunted physical growth and sapped vitality due to

undernourishment.

- The life expectancy of the average person is twenty years

less than his counterpart in tho affluent world; that is, he is

denied 30% of tho life-span of one born in the developed nations:

he is condemned at birth to an early death.

- 800 million of these people arc illiterate and, despite

continued expansion of educational opportunities, even more of their

children arc likely to be so.

e.

Julius Nyerere, President of Tanzania, has warned the rich

nations: "Poverty is not tho roal problem of the modern world, for

we have the knowledge and the resources which will enable us to over

come poverty. The real problem of the modern world, the thing which

creates misery, wars and hatred among men, is the division of mankind

into rich and poor".

f.

It is not so much the question of some having more to eat or

bottc-r clothes to wear, while others cannot provide oven the basic

requirements; it is rather the power that this wealth gives to some

to dominate, to oppress and to exploit the others.

In so .doing,

the rich and powerful justify themselves: "We deserve this wealth

and power: we have put our God-given talents to use and have worked

hard.

If the rest of the world is lazy, shiftless and ignorant,

w. can't helo that."

-22.

Extent of inequality in India today:

a. While we often and with some justification, blame all our

problems on the greediness of the affluent, developed nations, the

same ever-widening gap between the "haves" and the "have-nots"

appears here even

b. Within'our population of upwards 600 millions of people,

roughly 250 million live below the "poverty line", that dividing

line that demarcates bare minimum of survival for an individual.

This is the bottom 40 per cent, another 250 million live just

above the"poverty line" of human survival, the remaining 15-20

per cent, in an ascending pyramid represent the wealthy, dominant

classes with power, position and quality education: the raw mate

rial for further exploitation of the others.

c. In rural India, the top ten per cent own 50% of the land,

while the bottom 50 per cent own 4%; top ten per cent get 1/3 of

annual income of the nation,while the bottom 50% get less than

this amount for all of their numbers. 0.1% of the population owns

more than half the wealth of the area.

d. The poor are organised, without political power, and are

taken advantage of. A slum dweller admits: "Even to get a

sweeper's job, we have to pay a bribe of Rs.200/-"

c. The very poor (bottom 40 percent) have less than ft.--.40/- per

month to spend.

Most’cannot read or write.

1.

ro our findings differ according to the section of town we

come from? Why might this be so?

2.

How does this "minimum monthly income" compare with the incomes

of the families we met during our house survey last time?

3.

Dr> the families we met then exceed the number of members of

the "model" family of four we have used on this survey? What

would this mean with regard to their minimum monthly needs?

4.

Jhat may be the consequences when minimum monthly requirements

and income do not meet? Cutting corners? family insecurity?

undernourished and underclothed children? etc.

5.

What are some of the possible consequences of family insecurity?

quarrels? drunkenness? indebtedness bnat becomes chronic? etc.

6.

Who is to blame for so many people in our community living

under or just on "the poverty line"?

7.

Where does your family shop? What type of rice does your

family buy? What typo of cloth? How much rent?

How much

entertainment goes into your miscellaneous expenses?

8.

Was this a new experience for you, or have you iften done

the shopping in the past?

9.

How did you go about choosing the market and the different

shops?

10.

What did you learn from this experience?

D

1.

ro our findings differ according to the section of town we

come from? Why might this be so?

2.

How does this "minimum monthly income" compare with the incomes

of the families we met during our house survey last time?

3.

Do the families we met then exceed the number of members of

the "model" family of four we have used on this survey? What

would this mean with regard to their minimum monthly needs?

4.

What may be the consequences when minimum monthly requirements

and income do not meet? Cutting corners? family insecurity?

undernourished and underclothed children? etc.

5.

What are some of the possible consequences of family insecurity?

quarrels? drunkenness? indebtedness boat becomes chronic? etc.

6.

Who is to blame for so many people in our community living

under or just on "the poverty line"?

7.

Where does your family shop? What type of rice does your

family buy? What type of cloth? How much rent?

How much

entertainment goes into yuur miscellaneous expenses?

8.

Was this a new experience for you, or have you often done

the shopping in the past?

9.

’ l-pw did you go about choosing the market and the different

shops?

10.

What did you learn from this experience?

FOR RESTRICTED USE ONLY

ALLPORT

;

VERNON

: ‘LINDZEY

STUDY OF VALUES

Part I

DIRECTIONS k A number of controversial'statements or questions with two

alternative answers are given below. Indicate your personal preferences

by writing appropriate figures in the boxes to the right- of each question.

Some of the alternatives may appear equally attractive or unattractive to

you. Nevertheless, please attempt to choose the alternative that is

relatively more acceptable to you

*

For each, question you have three points

that you may distribute in any of the following combinations.

1,

If you agree with alternative (a)and disagree with (b), write 3 in

the first box and 6 is the second

box, thus

2.

If you agree with (b); disagree

with fb.) , write

3.

If you have a slight preference j,

for /a) over (b), write

4.

If you have a slight preference'for (b) over (a), write

Do not write any combination of numbers except one of these four.

Th: rc is no time limit, but.do not linger over any one question or

statement, and do not leavc’out arfy of the ouestions;unless you find

it really impossible to make a decision. .

BEHAVIOURAL SCIENCE CENTRffi ST.’XAVIER'S COLLEGE, AHMEDABAD 380 009

2

1. The main object of scientific research

should be the discovery of truth rather

than its practical apolications.

(a) Yes; (b) No.

2. Taking the Bible/Ramayana/Koran as a

whole, one should regard it from the

point of view, of its ■beautiful

mythology and literary.style rather

than as a spiritual revelation.(a) Yes; (b) No.

3. Which of the 'following men do you think

should be judged as contributing more

to the progress of mankind ? .

(a) Aristotle; (b) Abraham Lincoln.

4.

Assuming that you have sufficient

ability would you prefer to be;

(a) a banker; (b) a politician?

5.

Do you think it is justifiable for

great artists to be selfish and

negligent of the feelings of others^

(a) Yes; (b) No.1 , ,

6.

Which of the following branchesof

study do you expect ultimately wijl

prove more important for mankind ?!

(a) Mathematics; (b) Theology

7.

Which would you consider the moie

important function of modern leaders?

(a) to bring about the accomplishment

of practical goals; (b) to enceura^e

followers to take a greater interest

in the rights of others.

8.

When witnessing a gorgeous ceremony

(ecclesiastical or academic, inductbyi

into office, etc.), arc you more im^psed; (a) by the colour and pageantry of

the occasion itself; (b) by the inference

and strength of the group?

k>

total

a .

9.

Which, of these character traits'do you

consider the more desirable? (a) high

ideals and reverence: (b$ unselfishness

and sympathy.

10.

If you were a university professor arid

had the necessary ability, would you

prefer to teach: (a) Pbetry; (b)

chemistry and physics?

11. If you should sec the following news

items with headlines of equal size in

your morning paper, which would you

read more attentively? (a) RELIGIOUS

DIFFERENCES WITHIN ANY COMMUNITY:

(b) GREAT IMPROVEMENTS IN MARKET

COWITIONS.

12.

Under circumstances similar to those

of Question 11 ?. (a) SUPREME COURT

RENDERS DECISION: (b) NEW SCIENTIFIC

THEORY ANNOUNCED.

13.

When you visit a cathedral/temple/

mosque are you more impressed.by a

pervading sense of reverence and

worship than by the architectural

features, (a) Yes; (b) No.

14.

Assuming that you have sufficient

leisure time, would you prefer to

use iti (a) developing your mastery

of a favourite skill; (b) doing

volunteer social or public service

work ?

At an oxponiticti, do you chiefly like

to go to the buildings where you can

see: (a) new manufactured products;(b) scientific.(e.g. chemical)

apparatus?

- . ■'

16. If you had the opportunity, and if

nothing of the kind existed in the

community where you live, would you

prefer to found: (a) a debating society

■ or fprium; (b) a classical music Club

(Sarigeet Sammelan)

15.

- 4 -

17. The aim of the r.qligious orgariiiMtJdns

at-the present’ timeshopld be: (a) to,

'*

,......br^ng.^ur;,alia'uist-iQ-7’-a'ncl charitable’’ :

tendencies; (c) to encourage spiritual

worship and a sense^of communionwith

the. "highest

18.

i

'

If you had some, time to spend fn at

waiting room, and there were only two v/

magazines.to choose from, would you

prefer: (a) SCIENTIFIC AGE; (b). W ..

AND ADECORATIONS?

.

:

,

’■ ■

\

•. •

Would you prefer to hear a series of.

lectures on: (a) the comparative.merits

of the forms of:government in Britain.

and in the

*

United States; (b)' tAe'

A. parative development |f the great

-t~" religious '.faiths?

:

7'f ' . ?

19.

20; Whioji of the following would yotiicd’ri

aider the more important function b<5f

education? ; (a) it^ preparatidn>,'.fo^rt.W/i

practical .achievement ;and f irKifdii’ai

'! reward’s (b) its preparation fpr

..

‘ participation in'community activities

ajid Riding!less .fortunate persons,

21. Arc you more interested in reading

v-accounts -of *

thi "lives -and' works-of

. men such as:(a). Alexander, Julius

’

Caesar, and Ashoka; (c) Aristotle;

Socrates, and ^adhakrighnan

22. Are our modern industrial and scien

tific devrlppment's signs of a greatc:

degree of civilization•than those

■ attained by- any previous society, the

Greeks, for example? (a) Yes; (b) No, ‘

23.■ If you were'engaged in an industrial

organization (and assuming salaries to

be equal), would you prefer to work;

(a) as a counsellor for; employees;

(b) in an administrative position?

- 5 I

24.

Given your choice between two books

to read, arc you more likely to select:

(a) THE STORY OF RELIGION IN INDIA:

(b) TH1. STORY OF INDUSTRY IN INDIA:

25.

Would modern society benefit more from:

(a) more concern for the rights and

welfare of citizens; (b) greater knowa

ledge of the f mdamcntal laws of human |

behaviour.

-—

26.

Suppose you were in a position to help

raise standards of living, or to mould

public opinion. Would you prefer to

influence: (a) standards of living;

(b) public opinion?

27.

Would you prefer to hear a scries of

popular lectures on: (a) the progress

of social service work in your part of i—

the country; (b) contemporary painters? I

'

’

'■

28.

,111 the evidence that has been im- ■

partially accumulated goes to show

that the universe has evolved to its

present state in accordance with

natural principles, so that there is

no necessity to assume a first course,

cosmic purpose, or God behind it.

(a) I agree with this statement;

(b) I disagree

29.

In a paper; such as the New York

Sunday times, arc you more likely to

read: (a) the re"! estate sections

and the account of the stock market;

(b}-the section on picture galleries

and exhibitions?

30.

Would you consider it more important

for your child to secure training in

(a) religion; (b) athletics?

TOTAL

|

- 6 Part .II

DIRECTIONS: Each of the following situations or questions is followed

by four possible attitudes or answers. Arrange these answers in the

order of your personal preference by writing, in the appropriate box

at the right, a score of 4, 3, 2, or 1. .-.To the statement you prefer

most give 4, to the statement that is second most attractive 3, and

so on.

Example: If this were a question and the following statements were

alternative choices you would place:

4

in the box if this statement

appeals to you.

3

in the box if this statement

appeals to you second best.

2

in the box if this statement

appeals to you third best

1

in the box if this statement

represents your interest or

preference least of all.

You nay think of answers which would be preferable from your poin+ of

view to any of those listed. It is necessary, however, that you make

your selection from the alternatives presented, and arrange all four

in order of their desirability, guessing w^en your preferences are not

distinct, if you find it really impossible to state your preference,

you ray omit the question. Be sure not to assign more than one 4,

one 3, etc., for each question.

I

1. Do you think that a good government

should aim chiefly st—(kerie-iber- to give

your first choice 4, £,tc.)

a. more aid for the poor, sick and old

b. the development of manufacturing and

trade

i

c. introducing *

st

high

ethical principles ;

into its policies and diplomacy

d. establishing a position of prestige

_dj

and respect among nations.

In your opinion, can a man who works

in business all the week best spend

Sunday in

a. trying to educate himself by

reading serious books

b. Trying to win at golf, or racing

c. going to anorchestral concert

d. hearing a.really good sermon

b

J~~'

3. If you could influence the educational

policies of the public schools of some

city, would you undertake—

a. to promote the study and participa

tion in music and fine arts.

b. to stimulate the study of social

problems

c. to provide additional laboratory

facilities

d. to increase the practical value of

courses

4. Do you prefer a friend ( of your own

sex) who—

a. is efficient, industrious and of a

practical turn of mind.

b. is seriously interested in thinking

out his attitude toward life as a

whole

possess Qualities of leadership and'

c.

organizing ability.

shows artistic and emotional sensiti

d.

vity

5.

If you lived in a small town and had

more than enough income for your needs,

would you prefer to—

a. apply it productively to assist

commercial and industrial development

b. help to advance the activities of

local religious groups

c. give it for the development of scienti

fic research in your locality

d. give it to the. .Family 'frlfare Society

TOTAL

.- o -

6.

When you go tothe theater, do you,as

a rule, enjoy most—

a. plays that treat the lives of great

mon

b. ballet or similar imaginative neT-for~ances

c. plays that have a theme of human

suffering and love <

d. problem plays that argue consis

ts ntly for some noir.t of view

7.

Assuming that .you are a ">an with the

necessary ability, and that the

salary for each of the following

occupations is the same, would you

prefer to be a —

a. mathematician

b. sales manager

c. religious preacher

d. politician

8.

If you had sufficient leisure and

money, would you prefer to—

a. make a collection of fine sculotures or paintings

b. establish a certr for the care

and training of the feeble-minded

aim

c.

at a membership of Parliament

or a sent tn the Cabinet

d. establish a business or financial

enternrise of your own

9.

At an evening discussion with intimate

friends of your own sex, are you more

interested when you talk about—