R HEALTH PROMOTION MEETINGSEPORTS OF

Item

- Title

- R HEALTH PROMOTION MEETINGSEPORTS OF

- extracted text

-

ix)/Z

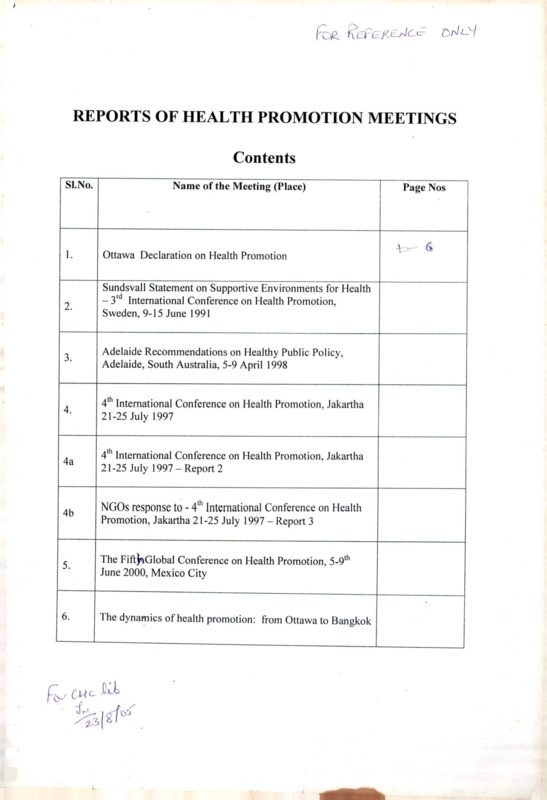

REPORTS OF HEALTH PROMOTION MEETINGS

Contents

Sl.No.

1.

Name of the Meeting (Place)

Ottawa Declaration on Health Promotion

Sundsvall Statement on Supportive Environments for Health

- 3rd International Conference on Health Promotion,

Sweden, 9-15 June 1991

2.

3.

Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public Policy,

Adelaide, South Australia, 5-9 April 1998

4.

4th International Conference on Health Promotion, Jakartha

21-25 July 1997

4a

4th International Conference on Health Promotion, Jakartha

21-25 July 1997-Report 2

4b

NGOs response to - 4th International Conference on Health

Promotion, Jakartha 21-25 July 1997 - Report 3

5.

The Fift^Global Conference on Health Promotion, 5-9th

June 2000, Mexico City

6.

The dynamics of health promotion: from Ottawa to Bangkok

L

Page Nos

T

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

The Bangkok charter for health Promotion in a Globalized

World, 7-llth August 2005____________________________

The 7th WHO Global conference on Health Promotion towards integration of oral health (Nairobi, kenya2009)._____

The 8th Global conference on Health promotion, Helsinki,

Finland, 10-14 June 2013. The Helsinki Statement on Health in

All Policies_________________________________________

9th Global Conference on Health Promotion Shanghai, 21-24

November, 2016. Shanghai Declaration on promoting health

in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

I

I

Sundsvall Statement on Supportive

Environments for Health

Third International Conference on Health Promotion, Sundsvall,

Sweden, 9-15 June 1991

The Third International Conference on Health Promotion: Supportive

Environments for Health - the Sundsvall Conference - fits into a sequence of

events which began with the commitment of WHO to the goals of Health For

All (1977). This was followed by the UNICEF/WHO International Conference

on Primary Health Care, in Alma-Ata (1978), and the First International

Conference on Health Promotion in Industrialized Countries (Ottawa 1986).

Subsequent meetings on Healthy Public Policy, (Adelaide 1988) and a Call for

Action: Health Promotion in Developing countries, (Geneva 1989) have

further clarified the relevance and meaning of health promotion. In parallel

with these developments in the health arena, public concern over threats to

the global environment has grown dramatically. This was clearly expressed

by the World Commission on Environment and Development in its report Our

Common Future, which provided a new understanding of the imperative of

sustainable development.

Third International Conference on Health

Promotion: Supportive Environments for Health the first global conference on health promotion, with participants from 81

countries - calls upon people in all parts of the world to actively engage in

making environments more supportive to health. Examining today's health

and environmental issues together, the Conference points out that millions of

people are living in extreme poverty and deprivation in an increasingly

degraded environment that threatens their health, making the goal of Health

For All by the Year 2000 extremely hard to achieve. The way forward lies in

making the environment - the physical environment, the social and economic

environment, and the political environment - supportive to health rather than

damaging to it.

This call for action is directed towards policy-makers and decision- makers in

all relevant sectors and at all levels. Advocates and activists for health,

environment and social justice are urged to form a broad alliance towards the

common goal of Health for All. We Conference participants have pledged to

take this message back to our communities, countries and governments to

initiate action. We also call upon the organizations of the United Nations

system to strengthen their cooperation and to challenge each other to be

truly committed to sustainable development and equity.

A Call for Action

i

I

I

1

A supportive environment is of paramount importance for health. The two are

interdependent and inseparable. We urge that the achievement of both be

made central objectives in the setting of priorities for development, and be

given precedence in resolving competing interests in the everyday

management of government policies. Inequities are reflected in a widening

gap in health both within our nations and between rich and poor countries.

This is unacceptable. Action to achieve social justice in health is urgently

needed. Millions of people are living in extreme poverty and deprivation in an

increasingly degraded environment in both urban and rural areas. An

unforeseen and alarming number of people suffer from the tragic

consequences for health and well-being of armed conflicts.

Rapid population growth is a major threat to sustainable development.

People must survive without clean water, adequate food, shelter or

sanitation.

Poverty frustrates people's ambitions and their dreams of building a better

future, while limited access to political structures undermines the basis for

self-determination. For many, education is unavailable or insufficient, or, in

its present forms, fails to enable and empower.

Millions of children lack access to basic education and have little hope for a

better future. Women, the majority of the world's population, are still

oppressed. They are sexually exploited and suffer from discrimination in the

labour market and many other areas, preventing them from playing a full

role in creating supportive environments. More than a billion people

worldwide have inadequate access to essential health care. Health care

systems undoubtedly need to be strengthened. The solution to these massive

problems lies in social action for health and the resources and creativity of

individuals and their communities. Releasing this potential requires a

fundamental change in the way we view our health and our environment, and

a clear, strong political commitment to sustainable health and environmental

policies. The solutions lie beyond the traditional health system.

Initiatives have to come from all sectors that can contribute to the creation of

supportive environments for health, and must be acted upon by people in

local communities, nationally by government and nongovernmental

organizations, and globally through international organizations. Action will

predominantly involve such sectors as education, transport, housing and

urban development, industrial production and agriculture.

The Sundsvall Conference identified many examples and approaches for

creating supportive environments that can be used by policy-makers,

decision-makers and community activists in the health and environment

sectors. The Conference recognized that everyone has a role in creating

supportive environments for health.

2

r

Dimensions of Action on Supportive Environments for

Health

)

In a health context the term supportive

environments refers to both the physical and the

social aspects of our surroundings. It encompasses where people live, their

local community, their home, where they work and play. It also embraces

the framework which determines access to resources for living, and

opportunities for empowerment. Thus action to create supportive

environments has many dimensions: physical, social, spiritual, economic and

political. Each of these dimensions is inextricably linked to the others in a

dynamic interaction. Action must be coordinated at local, regional, national

and global levels to achieve solutions that are truly sustainable.

The Conference highlighted four aspects of supportive environments:

•

)

•

•

•

The social dimension, which includes the ways in which norms,

customs and social processes affect health. In many societies

traditional social relationships are changing in ways that threaten

health, for example, by increasing social isolation, by depriving life of a

meaningful coherence and purpose, or by challenging traditional

values and cultural heritage.

The political dimension, which requires governments to guarantee

democratic participation in decision-making and the decentralization of

responsibilities and resources. It also requires a commitment to human

rights, peace, and a shifting of resources from the arms race.

The economic dimension, which requires a re-channelling of resources

for the achievement of Health for All and sustainable development,

including the transfer of safe and reliable technology.

The need to recognize and use women's skills and knowledge in all

sectors - including policy-making, and the economy - in order to

develop a more positive infrastructure for supportive environments.

The burden of the workload of women should be recognized and

shared between men and women. Women's community-based

organizations must have a stronger voice in the development of health

promotion policies and structures.

Proposals for Action

The Sundsvall Conference believes that proposals

to implement the Health for All strategies must

reflect two basic principles:

i.

1. Equity must be a basic priority in creating supportive environments for

health, releasing energy and creative power by including all human

beings in this unique endeavour. All policies that aim at sustainable

development must be subjected to new types of accountability

3

■h

It

A

J

)

procedures in order to achieve an equitable distribution of

responsibilities and resources. All action and resource allocation must

be based on a clear priority and commitment to the very poorest,

alleviating the extra hardship borne by the marginalized, minority

groups, and people with disabilities. The industrialized world needs to

pay the environmental and human debt that has accumulated through

exploitation of the developing world.

2. Public action for supportive environments for health must recognize

the interdependence of all living beings, and must manage all natural

resources, taking into account the needs of future generations.

Indigenous peoples have a unique spiritual and cultural relationship

with the physical environment that can provide valuable lessons for

the rest of the world. It is essential, therefore, that indigenous peoples

be involved in sustainable development activities, and negotiations be

conducted about their rights to land and cultural heritage.

It Can be Done: Strenghthening

Social Action

A call for the creation of supportive environments

is a practical proposal for public health action at the local level, with a focus

on settings for health that allow for broad community involvement and

control. Examples from all parts of the world were presented at the

Conference in relation to education, food, housing, social support and care,

work and transport. They clearly showed that supportive environments

enable people to expand their capabilities and develop self-reliance. Further

details of these practical proposals are available in the Conference report and

handbook.

Using the examples presented, the Conference identified four key public

health action strategies to promote the creation of supportive environments

at community level.

1. Strengthening advocacy through community action, particularly

I

through groups organized by women.

2. Enabling communities and individuals to take control over their health

and environment through education and empowerment.

3. Building alliances for health and supportive environments in order to

strengthen the cooperation between health and environmental

campaigns and strategies.

4. Mediating between conflicting interests in society in order to ensure

equitable access to supportive environments for health. In summary,

empowerment of people and community participation were seen as

essential factors in a democratic health promotion approach and the

driving force for self-reliance and development.

4

Participants in the Conference recognized, in particular, that education is a

basic human right and a key element in bringing about the political,

economic and social changes needed to make health a possibility for all.

Education should be accessible throughout life and be built on the principle of

equity, particularly with respect to culture, social class and gender.

The Global Perspective

People form an integral part of the earth's

ecosystem. Their health is fundamentally

interlinked with the total environment. All available information indicates that

it will not be possible to sustain the quality of life, for human beings and all

living species, without drastic changes in attitudes and behaviour at all levels

with regard to the management and preservation of the environment.

Concerted action to achieve a sustainable, supportive environment for health

is the challenge of our times.

At the international level, large differences in per capita income lead to

inequalities not only in access to health but also in the capacity of societies to

improve their situation and sustain a decent quality of life for future

generations. Migration from rural to urban areas drastically increases the

number of people living in slums, with accompanying problems - including

lack of clean water and sanitation.

Political decision-making and industrial development are too often based on

short-term planning and economic gains which do not take into account the

true costs to people's health and the environment. International debt is

seriously draining the scarce resources of the poor countries. Military

expenditure is increasing, and war, in addition to causing deaths and

disability, is now introducing new forms of ecological vandalism.

Exploitation of the labour force, the exportation and dumping of hazardous

substances, particularly in the weaker and poorer nations, and the wasteful

consumption of world resources all demonstrate that the present approach to

development is in crisis. There is an urgent need to advance towards new

ethics and global agreement based on peaceful coexistence to allow for a

more equitable distribution and utilization of the earth's limited resources.

Achieving Global Accountability

The Sundsvall Conference calls upon the

i.

international community to establish nw

mechanisms of health and ecological

accountability that build upon the principles of sustainable health

development. In practice this requires health and environmental impact

statements for major policy and programme initiatives. WHO and UNEP are

5

f

r

urged to strengthen their efforts to develop codes of conduct on the trade

and marketing of substances and products harmful to health and the

environment.

WHO and UNEP are urged to develop guidelines based on the principle of

sustainable development for use by Member States. All multilateral and

bilateral donor and funding agencies such as the World Bank and

International Monetary Fund are urged to use such guidelines in planning,

implementing and assessing development projects. Urgent action needs to be

taken to support developing countries in identifying and applying their own

solutions. Close collaboration with nongovernmental organizations should be

ensured throughout the process.

1

The Sundsvall Conference has again demonstrated that the issues of health,

environment and human development cannot be separated. Development

must imply improvement in the quality of life and health while preserving the

sustainability of the environment. Only worldwide action based on global

partnership will ensure the future of our planet.

)

Document resulting from the Third International Conference on Health

Promotion* 9-15 June 1991, Sundsvall, Sweden

!

*Co-sponsored by the United Nations Environment Programme, the Nordic

Council of Ministers, and the World Health Organization

1

1

6

1

■

■>

Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public

Policy

Second International Conference on Health Promotion,

Adelaide, South Australia, 5-9 April 1998

The adoption of the Declaration of Alma-Ata a decade ago was a major

milestone in the Health for All movement which the World Health Assembly

launched in 1977. Building on the recognition of health as a fundamental

social goal, the Declaration set a new direction for health policy by

emphasizing people's involvement, cooperation between sectors of society

and primary health care as its foundation.

The Spirit of Alma-Ata

The spirit of Alma-Ata was carried forward in the Charter for Health

Promotion which was adopted in Ottawa in 1986. The Charter set the

challenge for a move towards the new public health by reaffirming social

justice and equity as prerequisites for health, and advocacy and mediation as

the processes for their achievement.

The Charter identified five health promotion action areas:

■» Op

•

•

•

•

•

build Healthy Public Policy,'

create supportive environments,

develop personal skills,

strengthen community action, and

reorient health services.

<$

QjQ_O-

f

V

These actions are interdependent, but healthy public policy establishes the

environment that makes the other four possible.

The Adelaide Conference on Healthy Public Policy continued in the direction

set at Alma-Ata and Ottawa, and built on their momentum. Two hundred and

twenty participants from forty^two countries shared experiences in

formulating and implementing healthy public policy. The following

recommended strategies for healthy public policy action reflect the consensus

achieved at the Conference.

Healthy Public Policy

Healthy public policy is characterized by an

1.

explicit concern for health and equity in all areas

of policy and by an accountability for health

impact. The main aim of health public policy is to create a supportive

environment to enable people to lead healthy lives. Such a policy makes

I'

u

y

health choices possible or easier for citizens. It makes social and physical

environments health-enhancing. In the pursuit of healthy public policy,

government sectors concerned with agriculture, trade, education, industry,

and communications need to take into account health as an essential factor

when formulating policy. These sectors should be accountable for the health

consequences of their policy decisions. They should pay as much attention to

health as to economic considerations.

The value of health

Health is both a fundamental human right and a sound social investment.

Governments need to invest resources in healthy public policy and health

promotion in order to raise the health status of all their citizens. A basic

principle of social justice is to ensure that people have access to the

essentials for a healthy and satisfying life. At the same time, this raises

overall societal productivity in both social and economic terms. Healthy public

policy in the short term will lead to long-term economic benefits as shown by

the case studies presented a this Conference. New efforts must be made to

link economic, social, and health policies into integrated action.

Equity, access and development

J

Inequalities in health are rooted in inequities in society. Closing the health

gap between socially and educationally disadvantaged people and more

advantaged people requires a policy that will improve access to health

enhancing goods and services, and create supportive environments. Such a

policy would assign high priority to underprivileged and vulnerable groups.

Furthermore, a healthy public policy recognizes the unique culture of

indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, and immigrants. Equal access to health

services, particularly community health care, is a vital aspect of equity in

health.

New inequalities in health may follow rapid structural change caused by

emerging technologies. The first target of the European Region of the World

Health Organization, in moving towards Health for All is that:

”by the year 2000 the actual differences in health status between countries

and between groups within countries should be reduced by at least 25% by

improving the level of health of disadvantaged nations and groups.”

i

'I

In view of the large health gaps between countries, which this Conference

has examined, the developed countries have an obligation to ensure that

their own policies have a positive health impact on developing nations. The

Conference recommends that all countries develop healthy public policies

that explicitly address this issue.

Accountability for Health

-1

r

The recommendations of this Conference will be

realized only if governments at national, regional

—

-__ and local levels take action. The development of healthy public policy is as

as

important at the local levels of government as it is nationally. Governments

should set explicit health goals that emphasize health promotion.

Public accountability for health is an essential nutrient for the growth of

healthy public policy. Governments and all other controllers of resources are

ultimately accountable to their people for the health consequences of their

policies, or lack of policies. A commitment to healthy public policy means that

governments must measure and report the health impact of their policies in

language that all groups in society readily understand. Community action is

central to the fostering of healthy public policy. Taking education and literacy

into account, special efforts must be made to communicate with those groups

most affected by the policy concerned.

The Conference emphasizes the need to evaluate the impact of policy. Health

information systems that support this process need to be developed. This will

encourage informed decision-making over the future allocation of resources

for the implementation of healthy public policy.

Moving beyond health care

Healthy public policy responds to the challenges in health set by an

increasingly dynamic and technologically changing world, with is complex

ecological interactions and growing international interdependencies. Many of

the health consequences of these challenges cannot be remedied by present

and foreseeable health care. Health promotion efforts are essential, and

these require an integrated approach to social and economic development

which will reestablish the links between health and social reform, which the

World Health Organization policies of the past decade have addressed as a

basic principle.

Partners in the policy process

Government plays an important role in health, but health is also influenced

greatly by corporate and business interests, nongovernmental bodies and

community organizations. Their potential for preserving and promoting

people's health should be encouraged. Trade unions, commerce and industry,

academic associations and religious leaders have many opportunities to act in

the health interests of the whole community. New alliances must be forged to

provide the impetus for health action.

i

Action Areas

The Conference identified four key areas as

priorities for health public policy for immediate

1.

action:

Supporting the health of women

Women are the primary health promoters all over the world, and most of

their work is performed without pay or for a minimal wage. Women's

networks and organizations are models for the process of health promotion

organization, planning and implementation. Women's networks should

receive more recognition and support from policy-makers and established

institutions. Otherwise, this investment of women's labour increases inequity.

For their effective participation in health promotion women require access to

information, networks and funds. All women, especially those from ethnic^

indigenous, and minority groups, have the right to self-determination of their

health, and should be full partners in the formulation of healthy public policy

to ensure its cultural relevance.

This Conference proposes that countries start developing a national women's

healthy public policy in which women's own health agendas are central and

which includes proposals for:

•

•

•

•

equal sharing of caring work performed in society;

birthing practices based on women's preferences and needs;

supportive mechanisms for caring work, such as support for mothers

with children,

parental leave, and dependent health-care leave.

Food and nutrition

The elimination of hunger and malnutrition is a fundamental objective of

healthy public policy. Such policy should guarantee universal access to

adequate amounts of healthy food in culturally acceptable ways. Food and

nutrition policies need to integrate methods of food production and

distribution, both private and public, to achieve equitable prices. A food and

nutrition policy that integrates agricultural, economic, and environmental

factors to ensure a positive national and international health impact should

be a priority for all governments. The first stage of such a policy would be

the establishment of goals for nutrition and diet. Taxation and subsidies

should discriminate in favour of easy access for all to healthy food and an

improved diet.

The Conference recommends that governments take immediate and direct

action at all levels to use their purchasing power in the food market to

ensure that the food-supply under their specific control (such as catering in

hospitals, schools, day-care centres, welfare services and workplaces) gives

consumers ready access to nutritious food.

Tobacco and alcohol

fl

The use of tobacco and the abuse of alcohol are two major health hazards

that deserve immediate action through the development of healthy public

policies. Not only is tobacco directly injurious to the health of the smoker but

the health consequences of passive smoking, especially to infants, are now

more clearly recognized than in the past. Alcohol contributes to social

discord, and physical and mental trauma. Additionally, the serious ecological

consequences of the use of tobacco as a cash crop in impoverished

economies have contributed to the current world crises in food production

and distribution.

The production and marketing of tobacco and alcohol are highly profitable

activities - especially to governments through taxation. Governments often

consider that the economic consequences of reducing the production and

consumption of tobacco and alcohol by altering policy would be too heavy a

price to pay for the health gains involved.

This Conference calls on all governments to consider the price they are

paying in lost human potential by abetting the loss of life and illness that

tobacco smoking and alcohol abuse cause.

Governments should commit themselves to the development of healthy

public policy by setting nationally-determined targets to reduce tobacco

growing and alcohol production, marketing and consumption significantly by

Creating supportive environments

Many people live and work in conditions that are hazardous to their health

and are exposed to potentially hazardous products. Such problems often

transcend national frontiers.

Environmental management must protect human health from the direct and

indirect adverse effects of biological, chemical, and physical factors, and

should recognize that women and men are part of a complex ecosystem. The

extremely diverse but limited natural resources that enrich life are essential

to the human race. Policies promoting health can be achieved only in an

environment that conserves resources through global, regional, and local

ecological strategies.

A commitment by all levels of government is required. Coordinated

intersectoral efforts are needed to ensure that health considerations are

regarded as integral prerequisites for industrial and agricultural development.

At an international level, the World Health Organization should play a major

role in achieving acceptance of such principles and should support the

concept of sustainable development.

This Conference advocates that, as a priority, the public health and ecological

movements join together to develop strategies in pursuit of socioeconomic

development and the conservation of our planet's limited resources.

Developing New Health Alliances

The commitment to healthy public policy demands

an approach that emphasizes consultation and

------------------------------- -----negotiation. Healthy public policy requires strong advocates who put health

high on the agenda of policy-makers. This means fostering the work of

advocacy groups and helping the media to interpret complex policy issues.

Educational institutions must respond to the emerging needs of the new

public health by reorienting existing curricula to include enabling, mediating,

and advocating skills. There must be a power shift from control to technical

support in policy development. In addition, forums for the exchange of

experiences at local, national and international levels are needed.

The Conference recommends that local, national and international bodies:

•

•

establish clearing-houses to promote good practice in developing

healthy public policy;

develop networks of research workers, training personnel, and

programme managers to help analyse and implement healthy public

policy.

Commitment to Global Public

Health

Prerequisites for health and social development

are peace and social justice; nutritious food and clean water; education and

decent housing; a useful role in society and an adequate income;

conservation of resources and the protection of the ecosystem. The vision of

healthy public policy is the achievement of these fundamental conditions for

healthy living. The achievement of global health rests on recognizing and

accepting interdependence both within and between countries. Commitment

to global public health will depend on finding strong means of international

cooperation to act on the issues that cross national boundaries.

Second International Conference on Health Promotion,

Adelaide, South Australia, 5-9 April 1998

The adoption of the Declaration of Alma-Ata a decade ago was a major

milestone in the Health for All movement which the World Health Assembly

launched in 1977. Building on the recognition of health as a fundamental

social goal, the Declaration set a new direction for health policy by

emphasizing people's involvement, cooperation between sectors of society

and primary health care as its foundation.

The Spirit of Alma-Ata

The spirit of Alma-Ata was carried forward in the Charter for Health

Promotion which was adopted in Ottawa in 1986. The Charter set the

challenge for a move towards the new public health by reaffirming social

justice and equity as prerequisites for health, and advocacy and mediation as

the processes for their achievement.

The Charter identified five health promotion action areas:

•

•

•

•

•

build Healthy Public Policy,

create supportive environments,

develop personal skills,

strengthen community action, and

reorient health services.

These actions are interdependent, but healthy public policy establishes the

environment that makes the other four possible.

The Adelaide Conference on Healthy Public Policy continued in the direction

set at Alma-Ata and Ottawa, and built on their momentum. Two hundred and

twenty participants from forty-two countries shared experiences in

formulating and implementing healthy public policy. The following

recommended strategies for healthy public policy action reflect the consensus

achieved at the Conference.

Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public Policy : Previous page |

1,2,3,4,5,6, Z

Healthy Public Policy

Healthy public policy is characterized by an

explicit concern for health and equity in all areas —-——-------- ----of policy and by an accountability for health impact. The main aim of health

public policy is to create a supportive environment to enable people to lead

healthy lives. Such a policy makes health choices possible or easier for

citizens. It makes social and physical environments health-enhancing. In the

d

pursuit of healthy public policy, government sectors concerned with

agriculture, trade, education, industry, and communications need to take into

account health as an essential factor when formulating policy. These sectors

should be accountable for the health consequences of their policy decisions.

They should pay as much attention to health as to economic considerations.

The value of health

Health is both a fundamental human right and a sound social investment.

Governments need to invest resources in healthy public policy and health

promotion in order to raise the health status of all their citizens. A basic

principle of social justice is to ensure that people have access to the

essentials for a healthy and satisfying life. At the same time, this raises

overall societal productivity in both social and economic terms. Healthy public

policy in the short term will lead to long-term economic benefits as shown by

the case studies presented a this Conference. New efforts must be made to

link economic, social, and health policies into integrated action.

Equity, access and development

Inequalities in health are rooted in inequities in society. Closing the health

gap between socially and educationally disadvantaged people and more

advantaged people requires a policy that will improve access to health

enhancing goods and services, and create supportive environments. Such a

policy would assign high priority to underprivileged and vulnerable groups.

Furthermore, a healthy public policy recognizes the unique culture of

indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, and immigrants. Equal access to health

services, particularly community health care, is a vital aspect of equity in

health.

New inequalities in health may follow rapid structural change caused by

emerging technologies. The first target of the European Region of the World

Health Organization, in moving towards Health for All is that:

"by the year 2000 the actual differences in health status between countries

and between groups within countries should be reduced by at least 25% by

improving the level of health of disadvantaged nations and groups."

In view of the large health gaps between countries, which this Conference

has examined, the developed countries have an obligation to ensure that

their own policies have a positive health impact on developing nations. The

Conference recommends that all countries develop healthy public policies

that explicitly address this issue.

Accountability for Health

(I

The recommendations of this Conference will be

1.

realized only if governments at national, regional

and local levels take action. The development of

healthy public policy is as important at the local levels of government as it is

nationally. Governments should set explicit health goals that emphasize

health promotion.

Public accountability for health is an essential nutrient for the growth of

healthy public policy. Governments and all other controllers of resources are

ultimately accountable to their people for the health consequences of their

policies, or lack of policies. A commitment to healthy public policy means that

governments must measure and report the health impact of their policies in

language that all groups in society readily understand. Community action is

central to the fostering of healthy public policy. Taking education and literacy

into account, special efforts must be made to communicate with those groups

most affected by the policy concerned.

The Conference emphasizes the need to evaluate the impact of policy. Health

information systems that support this process need to be developed. This will

encourage informed decision-making over the future allocation of resources

for the implementation of healthy public policy.

Moving beyond health care

Healthy public policy responds to the challenges in health set by an

increasingly dynamic and technologically changing world, with is complex

ecological interactions and growing international interdependencies. Many of

the health consequences of these challenges cannot be remedied by present

and foreseeable health care. Health promotion efforts are essential, and

these require an integrated approach to social and economic development

which will reestablish the links between health and social reform, which the

World Health Organization policies of the past decade have addressed as a

basic principle.

Partners in the policy process

Government plays an important role in health, but health is also influenced

greatly by corporate and business interests, nongovernmental bodies and

community organizations. Their potential for preserving and promoting

people's health should be encouraged. Trade unions, commerce and industry,

academic associations and religious leaders have many opportunities to act in

the health interests of the whole community. New alliances must be forged to

provide the impetus for health action.

Action Areas

The Conference identified four key areas as

Supporting the health of women

Women are the primary health promoters all over the world, and most of

their work is performed without pay or for a minimal wage. Women's

networks and organizations are models for the process of health promotion

organization, planning and implementation. Women's networks should

receive more recognition and support from policy-makers and established

institutions. Otherwise, this investment of women's labour increases inequity.

For their effective participation in health promotion women require access to

information, networks and funds. All women, especially those from ethnic,

indigenous, and minority groups, have the right to self-determination of their

health, and should be full partners in the formulation of healthy public policy

to ensure its cultural relevance.

1

This Conference proposes that countries start developing a national women's

healthy public policy in which women's own health agendas are central and

which includes proposals for:

•

•

•

•

equal sharing of caring work performed in society;

birthing practices based on women's preferences and needs;

supportive mechanisms for caring work, such as support for mothers

with children,

parental leave, and dependent health-care leave.

Food and nutrition

The elimination of hunger and malnutrition is a fundamental objective of

healthy public policy. Such policy should guarantee universal access to

adequate amounts of healthy food in culturally acceptable ways. Food and

nutrition policies need to integrate methods of food production and

distribution, both private and public, to achieve equitable prices. A food and

nutrition policy that integrates agricultural, economic, and environmental

factors to ensure a positive national and international health impact should

be a priority for all governments. The first stage of such a policy would be

the establishment of goals for nutrition and diet. Taxation and subsidies

should discriminate in favour of easy access for all to healthy food and an

improved diet.

The Conference recommends that governments take immediate and direct

action at all levels to use their purchasing power in the food market to

ensure that the food-supply under their specific control (such as catering in

hospitals, schools, day-care centres, welfare services and workplaces) gives

consumers ready access to nutritious food.

Tobacco and alcohol

)

»

The use of tobacco and the abuse of alcohol are two major health hazards

that deserve immediate action through the development of healthy public

policies. Not only is tobacco directly injurious to the health of the smoker but

the health consequences of passive smoking, especially to infants, are now

more clearly recognized than in the past. Alcohol contributes to social

discord, and physical and mental trauma. Additionally, the serious ecological

consequences of the use of tobacco as a cash crop in impoverished

economies have contributed to the current world crises in food production

and distribution.

The production and marketing of tobacco and alcohol are highly profitable

activities - especially to governments through taxation. Governments often

consider that the economic consequences of reducing the production and

consumption of tobacco and alcohol by altering policy would be too heavy a

price to pay for the health gains involved.

This Conference calls on all governments to consider the price they are

paying in lost human potential by abetting the loss of life and illness that

tobacco smoking and alcohol abuse cause.

Governments should commit themselves to the development of healthy

public policy by setting nationally-determined targets to reduce tobacco

growing and alcohol production, marketing and consumption significantly by

the year 2000.

Creating supportive environments

Many people live and work in conditions that are hazardous to their health

and are exposed to potentially hazardous products. Such problems often

transcend national frontiers.

Environmental management must protect human health from the direct and

indirect adverse effects of biological, chemical, and physical factors, and

should recognize that women and men are part of a complex ecosystem. The

extremely diverse but limited natural resources that enrich life are essential

to the human race. Policies promoting health can be achieved only in an

environment that conserves resources through global, regional, and local

ecological strategies.

A commitment by all levels of government is required. Coordinated

intersectoral efforts are needed to ensure that health considerations are

regarded as integral prerequisites for industrial and agricultural development.

At an international level, the World Health Organization should play a major

role in achieving acceptance of such principles and should support the

concept of sustainable development.

!

This Conference advocates that, as a priority, the public health and ecological

movements join together to develop strategies in pursuit of socioeconomic

development and the conservation of our planet's limited resources.

Developing New Health Alliances

The commitment to healthy public policy demands

an approach that emphasizes consultation and

—------------------negotiation. Healthy public policy requires strong advocates who put health

high on the agenda of policy-makers. This means fostering the work of

advocacy groups and helping the media to interpret complex policy issues.

Educational institutions must respond to the emerging needs of the new

public health by reorienting existing curricula to include enabling, mediating,

and advocating skills. There must be a power shift from control to technical

support in policy development. In addition, forums for the exchange of

experiences at local, national and international levels are needed.

The Conference recommends that local, national and international bodies:

•

•

establish clearing-houses to promote good practice in developing

healthy public policy;

develop networks of research workers, training personnel, and

programme managers to help analyse and implement healthy public

policy.

Commitment to Global Public

Health

Prerequisites for health and social development

are peace and social justice; nutritious food and clean water; education and

decent housing; a useful role in society and an adequate income;

conservation of resources and the protection of the ecosystem. The vision of

healthy public policy is the achievement of these fundamental conditions for

healthy living. The achievement of global health rests on recognizing and

accepting interdependence both within and between countries. Commitment

to global public health will depend on finding strong means of international

cooperation to act on the issues that cross national boundaries.

Future Challenges

i

)

1. Ensuring an equitable distribution of

resources even in adverse economic

-——------------------------circumstances is a challenge for all nations.

Health for All will be achieved only if the creation and preservation of

healthy living and working conditions become a central concern in all

'<)I

1

>

!

public policy decisions. Work in all its dimensions - caring work,

opportunities for employment, quality of working life - dramatically

affects people's health and happiness. The impact of work on health

and equity needs to be explored.

3. The most fundamental challenge for individual nations and

international agencies in achieving healthy public policy is to

encourage collaboration (or developing partnerships) in peace, human

rights and social justice, ecology, and sustainable development around

the globe.

4. In most countries, health is the responsibility of bodies at different

political levels. In the pursuit of better health it is desirable to find new

ways for collaboration within and between these levels.

5. Healthy public policy must ensure that advances in health-care

technology help, rather than hinder, the process of achieving

improvements in equity.

The Conference strongly recommends that the World Health Organization

continue the dynamic development of health promotion through the five

strategies described in the Ottawa Charter. It urges the World Health

Organization to expand this initiative throughout all its regions as an

integrated part of its work. Support for developing countries is at the heart of

this process.

Renewal of Commitment

In the interests of global health, the participants at the Adelaide Conference

urge all concerned to reaffirm the commitment to a strong public health

alliance that the Ottawa Charter called for.

EXTRACT FROM THE REPORT ON THE ADELAIDE CONFERENCE * HEALTHY

PUBLIC POLICY, 2nd International Conference on Health Promotion April 5-9,

1988 Adelaide South Australia

* Co-sponsored by the Department of Community Services & Health,

Canberra, Australia and the World Health Organization Regional Office for

Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark.

ll

1

)

New Players for a New Era

Leading Health Promotion

into the 21st Centurn

4th International Conference on Health Promotion

Jakarta, Indonesia 21 -25 July 1997

Conference Report

Ar

QA

} 2 1 DEC ’'Wft i!

MH

Table of Content

Foreword

Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion Report

Conference Format ..............................................

Structure of the Report.................. ’

..................

The Road to Jakarta ........................................................

Where Are We Now?........

. 1

Healthy Cities/villages/islands/communities

Health Promoting Schools .......................................................

Healthy Workplaces........................................................

Healthy Ageing

.................................................

Active Living/Physical Activity .................................................

Sexual Health.....................................................................

Tobacco free societies...............................................

Promoting women's health.......................................................

Health promoting health care settings

Healthy homes/families ...........................................................

.. 4

.. 4

.. 5

.. 5

.. 6

.. 6

.. 7

.. 7

.. 8

.. 8

The Road Ahead ......................................................

Healthy Cities/villages/islands/communities ...........................

Health Promoting Schools ...................................................

Healthy Workplaces.......................................................

Active Living/Physical Activity ...................................

Sexual Health.............................................................

Tobacco free societies...............................................................

Promoting women's health.........................................................

Health promoting health care settings .......................................

With Whom Do We Travel?

A Global Commitment

Partnerships and Alliances

The Global Healthy Cities Network

Global School Health Initiative

Healthy Work Initiative

Healthy Ageing Initiative

Active Living Initiative

Mega-Country Initiative

Health Promotion Foundations Initiative

Health Promotion for Chronic Health Conditions

Health Promoting Hospitals Initiative

Health Promoting Media Settings

)

Conference Conclusions

..........................

Tradition.........................................................................

Future

Evidence........................................................................

Partnerships

...........................................

The beginning of the future

The Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century

Special Statements

Statement on healthy ageing

Statement on health promoting schools

Statement on healthy workplaces ................

Statement on partnerships for healthy cities .

Statement of member companies and groups

. 1

. 2

. 2

. 4

. 8

. 11

. 12

. 12

. 13

. 13

. 14

. 14

. 15

16

17

19

19

19

20

21

21

22

23

23

23

24

26

26

26

26

27

27

28

34

35

36

37

38

Annexes

Annex 1 - Conference Programme ....................................................

Annex 2 - Conference Secretariat........................................................

Annex 3 - Conference Advisory Group ................................................

Annex 4 - List of Background Papers ..................................................

Review and evaluation of health promotion...................................................

Health promotion futures ........................................... ...................................

Partnerships for health promotion .................................................................

Other publications/ sources...........................................................................

Annex 5 - Follow-up Activities ..............................................................

Annex 6 - World Health Assembly 51 Resolution on Health Promotion .

Acknowledgments

. 39

. 66

. 67

. 71

. . 71

. . 72

. . 73

. . 74

. 75

. 76

78

il

1

Foreword

The Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion: ‘New Players fora New

Era - Leading Health Promotion into the Twenty-first Century’,

Jakarta, 21-25 July 1997

The spirit of Alma-Ata was carried forward in the Ottawa Charter developed at the First

International Conference on Health Promotion (1986) in Ottawa, Canada. The Ottawa Charter,

with its five independent action areas, has since served as the blue print for health promotion

worldwide. The subsequent Second and Third International Conferences on Health Promotion

in Adelaide, Australia (1988) and in Sundsvall, Sweden (1991), examined two major action

strategies of health promotion, resulting in the adoption of the Adelaide Recommendations on

Healthy Public Policy and the Sundsvall Statement on Supportive Environments.

The Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion was the first to be held in a

developing region. It provided the opportunity to exchange experiences, for developing and

developed countries to share and to learn from each other. In view of the major changes which

have taken place since the Ottawa Conference in 1986, it provided the opportunity to evaluate

the impact of health promotion globally and its priorities in today’s world.

It is essential to review and evaluate the impact of health promotion globally, to take

stock, to provide vision as to the most desirable future scenarios for world health and to try and

identify the approaches, partnerships and alliances which will be required to achieve the desired

goal.

Consequently, the Jakarta Conference had three objectives:

a)

b)

c)

>

to review and evaluate the impact of health promotion;

to identify innovative strategies to achieve success in health promotion; and

to facilitate the development of partnerships in health promotion to meet the global

health challenges.

Preparations for the Conference, which formed the central focus in 1997 of the WHO

Five-Year Plan for health promotion, served as a catalyst to stimulate action in capacity build

capacity for health promotion at local, national and international levels in both developing and

developed countries. A series of planned preparatory activities were carried out jointly with the

WHO Regional Offices and/or through WHO Collaborating Centers and NGOs in all regions,

including intercountry meetings, workshops, and consultations.

These preparations contributed to three major inputs, each addressing one of the

specific Conference objectives, namely: I) review and evaluation track; II) scenario/futures

track; III) partnership track.

I)

The review and evaluation track was developed following a global literature analysis of

all evaluated health promotion and education projects. Case studies, published or

unpublished, on successful health education and health promotion action were collected

and analyzed on a region by region basis through specially appointed focal points. The

overall state of health promotion research was reviewed. A number of WHO

Collaborating Centers held symposia on the effectiveness of health promotion and

prepared papers on health promotion evaluation and research. The results of these

efforts provided convincing evidence that health promotion strategies can develop and

change lifestyles, and have an impact on the social, economic and environmental

conditions, that determine health (a book with selected papers is available as part of

proceedings).

II)

The scenario/futures track provided a set of health promotion futures papers and

practical guidelines in scenario development. Guidelines for developing scenarios and a

global scenario for health promotion in 2020 were specially prepared. Detailed review

for health promotion futures in selected topics areas were also prepared, including health

promoting schools, workplace health promotion, tobacco free society, ageing and health

sexual health, women’s health, healthy cities, and food and nutrition.

III)

The third input was on building partnerships for which a series of five papers were

prepared outlining the possible way forward, including one on partnerships for health in

the 21 st Century, and a working paper on partnerships for health promotion. Also, a

series of six specific issue papers were prepared for review at the conference as part of

the health promoting school global initiative.

The Jakarta Declaration confirmed the five action areas of the Ottawa Charter:

•

build healthy public policy;

•

create supportive environments;

•

strengthen community action;

•

develop personal skills;

•

reorient health services.

Research and case studies from around the world provided convincing evidence that health

promotion is effective and confirmed its continuing validity and relevance. It placed health

promotion at the centre of health development. In calling for a global alliance it widened the

emphasis to include all sectors of society to work together for the health and well-being of all

peoples and societies. The Jakarta Declaration set out the global priorities for health promotion

as we enter the new century - health promotion is a key investment.

The success of the 4 ICHP is due to the active contribution of many, the host country, WHO,

HQ and the Regional Offices, WR Country Offices, WHO CCs, UN, IGOs and NGOs.

Special gratitude is extended to all; to the countries, institutions and bodies whose support

enabled the Conference to take place and assistance to be given to many participants who

would otherwise have been able to attend. We are most grateful to all who have contributed to

this collective global effort.

Since the Jakarta Conference there has been active follow-up. In May 1998 the World Health

Assembly (WHA) has passed the first ever Resolution on Health Promotion confirming the

priorities as identified in the Jakarta Declaration and to report back to the WHA in two years

time on the progress achieved. This challenge has now to be met.

Dr Desmond O’Byrne

Chief, Health Education and

Health Promotion Unit (HEP)

World Health Organization

Dr Ilona Kickbusch

Director, Division of Health Promotion,

Education and Communication (HPR)

World Health Organization

!

Fourth International Conference

on Health Promotion

Report

Conference Format

J

The Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion (4ICHP) took place in Jakarta,

it was the first in the series to be hosted by a country from the South, with a majority of

participants coming from the South. But this was not the only thing that made 'Jakarta'

unique. It was the first conference of the four to deal with three different but intricately

connected themes:

•

The Conference was to review critically the

achievements in the area of health promotion

First Truly Global

since the adoption of the Ottawa Charter;

•

The meeting was to explore possibilities and

Health Promotion

commitments towards the involvement of new

players in partnerships and alliances for

health promotion;

•

It was to formulate the challenges that are ahead of us, as well as the responses and

strategies which health promoters in their partnerships and alliances could employ.

These objectives made the conference very much a working

Achievements

meeting. Plenaries provided food for thought, to be

expressed in a daily symposia series. Morning plenary

Partnerships

sessions were followed by 'Leading Change' symposia in

which insights on new work styles, health promotion skills,

Strategies

the economics of health promotion, ethical conduct, new

technologies and much more were shared. In this report, 'Leading Change’symposia will

not be reported on, as they were conceived to be training-like sessions; information on

sessions can be obtained through their facilitators. Further, networking time was scheduled

every day in order to facilitate further exchange around themes felt important to participants;

every late afternoon participants were found all over the conference venue, involved in

debates. The core of the conference process was found

in ‘Partnership in Action’ symposia, which will be

reported on below.

Indonesia Day on

The centre of the programme was constituted by

Health Promotion

Indonesia Day, during which the host country’s health

promotion policy was unveiled and national and local health promotion programmes were

presented. Indonesia has committed itself formally to the theme of the conference, and

presented an overview of the most innovative health programmes in the country.

The commitments formulated around the above-mentioned themes were ultimately reflected

in the Jakarta Declaration, the development of which was a continuous participatory process

throughout the conference.

1

d

1

Structure of the Report

Rather than following the structure of the conference, this part of the report takes a more

evolutionary perspective. The next section describes developments that made a 4ICHP on

/Vew Players for a New Era' timely. It contains a review of political and scientific advances

in the field.

.

The 'Where are We /Vow?'section takes stock of the current state of health promotion in

settings, contexts and stages of life. 'The Road Ahead' takes an overall view of health

promotion challenges in the new era, supplemented by findings of a second set of Symposia

on contexts and settings. Partnerships are dealt with in the subsequent section. ‘With Whom

do we Travel?’. The ‘Conclusion’ deals with health promotion tradition, future challenges

evidence of health promotion working, and partnership issues.

Throughout the report, the global commitment to health promotion in the next millennium

will become obvious. In ‘A Global Commitment’ representatives of some of the major

political global constellations will be presented.

The Road to Jakarta

‘Jakarta’ should be viewed in the context of a health promotion development process that

was started with the adoption of the Ottawa Charter in 1986. This conference was followed

in 1989 by a conference in Adelaide dealing with Healthy Public Policy. The third

international conference on health promotion dealt with Supportive Environments for Health

and was organised in Sundsvall, 1991.

The Fourth Conference is not only

significant because we are on the brink of

Dynamic forward-looking

the next millennium (a symbolic threshold

j

.

.

which stimulates the imagination), but

development

also because the world seems to be changing at an ever increasing pace.

Neither of the above developments can be separated from the context of Primary Health

Care (Alma Ata, 1978) and the rejuvenated strategy Health for All by the Year 2000. These

major initiatives constitute a strong global commitment to public health.

Particularly globalization of communication, trade, and norms and values was referred to

by many as being the most recent challenges. The WHO/SEARO Regional Director (Dr

Uton Muchtar Rafei) said during the very

first plenary session that ‘the New Era has

already begun. ’

Two leading policy makers also took stock

of the advances of health promotion in the

changing context of their countries. Mr I

Potter (Assistant Deputy Minister for Health) demonstrated the Canadian commitment to

working on prerequisites for health (particularly the distribution of wealth), and the need for

intersectoral collaboration in the development of healthy public policy. And even though

economically adverse conditions abound, health promotion has been growing. Hungarian

Minister for Health Dr M. Kokeny also dealt with economic and political changes He

explained that the launch of the Ottawa Charter, in 1986, came both too early and too late

for his country. Because of a deteriorating economy, health promotion at that time was not

Globalization of

communication, trade 9

norms and values

2

perceived to be feasible; once the former socialist block (1990) had disappeared, it seemed

that health promotion could no longer claim a place on the political agenda. Yet, in spite of

a decrease in GDP and the actions driven by market forces, health promotion is back on the

agenda. Health Promoting Schools and Healthy Cities are very much integrated in the

Hungarian health domain.

Mr J. Mullen, of the 'Private Sector for Health Promotion', suggested that indeed the

conference was a landmark, acknowledging the important contributions that the private

sector has already made and will make in the future. He showed that the private sector is

already collaborating intensively with the health sector in a number of regions. Further

global partnerships can be developed, he asserted.

A review of the effectiveness of alliances and partnerships for health promotion presented

by Prof P. Gillies (Health Education Authority, London) examined evidence of the success

of health promotion. Two approaches to the study were chosen: a literature review using

.

bibliographies of peer-reviewed

Significant behaviour change. journals, and snowball sampling

through a network of global focal

Yet: more emphasis on

point consultants who were asked to

provide further case studies.

‘Social Capita!’\n studies

Following a validated search

protocol, 16 randomised controlled

trials, 15 comparison studies, and 12 pre-post test evaluations were found. They generally

reflected a narrow focus on behaviour change alone, although some highlighted process

and policy development outcomes. The focal point consultants provided a further 46

examples of health promotion alliances and partnership programmes. These were

predominantly from developing regions in the world.

Significant health behaviour change has been reported. The concept of 'social capital' would

potentially add a crucial dimension to the understanding of social influences on health, and

would take into account the broader contexts in which health is produced. The approach

would focus attention on the mechanisms connecting people with public'institutions and with

power at local level. The idea of social capital may therefore have much to offer to health

promotion research in future, particularly those studies that aim to understand and evaluate

the impact of alliances or partnerships for health promotion.

3

J

Where Are We Now?

The Monday series of Symposia was to take stock of health promotion developments in a

number of settings, contexts and stages of life,

important for the further development of the

Settings, contexts and

realm. In this section these developments are

being summarised; a conclusion will lead into

stages of life

responses to future challenges in these areas.

1

)

J

1

Healthy Cities/villages/islands/communities

Being started as a health promotion demonstration project in the European Region of WHO

in 1986, the Healthy Cities initiative is now an established global movement. Three case

studies were presented, from Kuching (Malaysia), Queensland (Australia), and Samoa.

One of the very first agreements the participants established was that 'Healthy City' is the

catch phrase for a wide variety of health promotion programmes related to larger scale

contained living arrangements. Therefore, healthy islands, communities, and villages -in

spite of their unique social and geographic set-ups- would all fall under the one slogan.

The approach has become an umbrella for many other setting approaches, e.g. in schools,

hospitals and market places. It

Link ideas, visions, political contributes to the establishment of high

quality

physical

infrastructures,

commitment and social

psychosocial

environment,

and

sustainability

of

health

action.

It

entrepreneurship to health

effectively combines the 'art' and

'science' dimensions of public health, linking ideas, visions, political commitment and social

entrepreneurship to the management of resources, methods for infrastructure development,

and the establishment of procedures to respond to community needs. Intersectoral work is

an integral part of the movement, with many partnerships already in place.

Nevertheless, further strategic considerations and evaluations on capacity building

(including political commitment), process development and implementation and outcome

measures will be as crucial in the future as they are now.

Whatever the size of the target population (be they inhabitants of mega-cities or of small

islands), the importance of action at the local level is identified as essential.

V

Health Promoting Schools

Schooling is of course one of the best investments in the future. National and international

experiences now show that schools provide also the best opportunities for investment in

health. Examples from China, India, Russia, USA, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, most

European countries including

Romania, Zimbabwe, Thailand,

The best investment in the

Samoa, Australia, Brazil, and Sri

Lanka showed the immense

future

potential that schools have in

comprehensive health promotion. Collaboration between schools and local health services,

with parents and local communities, with teachers also becoming aware of health issues,

4

!

with pupils, through intergenerational activities, and with professional sports associations

or the food industry shows that the concept is easy to apply, stirs the imagination in and

beyond schools, and has both direct benefits as well as longer-term health benefits. Some

direct benefits are improvement of the overall curriculum and active student participation in

both curricular and extra-curricular activities. Also, Health Promoting Schools offer a

comprehensive package of behavioural and structural interventions that is most appropriate

for children in school-ages. Even children not in school, as evidence from Samoa and India

demonstrates, could well be reached through the programme.

The major strength of, Networks of Health Promoting Schools, is its network building, the

designation of national focal points, involvement of experts in the field of school health, and

the mobilisation of resources at a regional level.

Healthy Workplaces

Workplace health promotion until quite recently seems to have been a largely European and

North-American approach. The Conference created an excellent opportunity to take stock

of experiences elsewhere in the world.

Two models were considered innovative. A German example was used in more than

seventy organisations, nationally and internationally. This 'Health Circle Approach' is based

on the availability of problem-solving tools

6 If you can’t manage

at the management level, but employees

- 4

,

decide on need and feasibility of

SaTety, you can t manage interventions during eight work-time

anything ’

sessions. The approach connects with

J

.

future-oriented management, is flexible and

yet broad in its scope, and is easily implemented on the work floor as it is precisely there

where the programme is designed in operational terms.

Another model was that of accident prevention in Scandinavia, starting at the workplace,

but extending to every setting of everyday life. The assumptions were that

•

if a company cannot manage safety, it cannot manage anything;

•

all accidents can be prevented.

The approach involved industry, the municipality, and the community.

Several other examples were presented during the session, demonstrating that workplace

health promotion is a global effort. A notable programme was presented from Shanghai,

where a number of factories engaged in innovative approaches to enhance the health and

well-being of workers and their communities.

Successful workplace health promotion requires the following:

The support for programmes by company leadership and top management is

essential;

•

'Investment in workers' health is a good investment' is a message that has to be

communicated to businesses more unequivocally.

•

The community around the workplace must be involved in a coalition with an interest

in workplace health promotion; incentives are part of the coalition formation.

•

Mental health and stress prevention among workers merits special attention.

Healthy Ageing

Ageing has become a development issue: An ageing population should not be considered

a burden on society, but as a challenge and an opportunity. The vast majority of old people

5

are independent and in good health. They are productive

(though not only in economic terms) and contribute to their

Ageing is a

communities in a variety of ways.

The healthy ageing message can best be heard by

development

establishing networks. Such networks are interdisciplinary,

issue

flexible, informed, and dynamic. Synergy creates an

enhanced approach, much better than isolated projects by individual organisations.

Evidence now shows that health promotion action could lead to, e.g. sustained or increased

levels of physical activity leading to decreased levels of cholesterol and morbidity.

Active Living/Physical Activity

Accumulated scientific evidence shows that daily moderate activity enhances health

Physical activity contributes to mental health, and to the reduction of risks related to e g'

obesity. Modern lifestyles, however, make it increasingly difficult and provide less and less

incentive for people to remain physically active.

Active living should start at an early age, and schools offer in that respect more effective

efficient and equal opportunities than any

other setting to get young people interested in Activity good for mental

physical activity, and enjoy it.

.

Experiences so far suggest three pathways to

health

successful development and implementation of active living programmes;

•

A sound scientific base, providing valid assessment tools, social and clinical

diagnoses, and trends in active living;

•

Development and evaluation of community interventions, including the joint

development of behavioural components, policy development, and the creation of

appropriate facilities;

•

Effective dissemination and communication of information both to professionals and

the general public.

Sexual Health

Sexual health has increasingly become a key public health issue. The HIV/AIDS epidemic