PUBLIC HEALTH IN INDIA : CRISIS, CHALLENGES

Item

- Title

- PUBLIC HEALTH IN INDIA : CRISIS, CHALLENGES

- extracted text

-

RF_COM_H_49_SUDHA.

f'

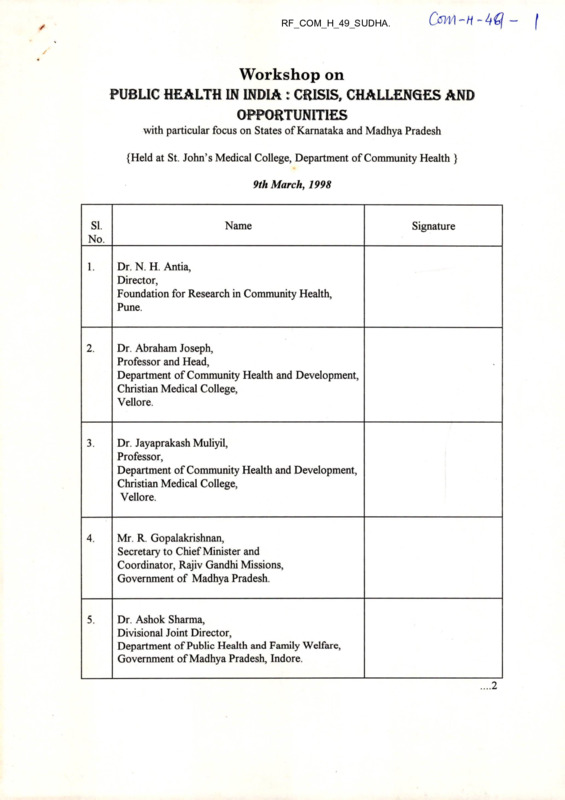

Workshop on

PUBLIC HEALTH IN INDIA : CRISIS, CHALLENGES AND

OPPORTUNITIES

with particular focus on States of Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh

{Held at St. John’s Medical College, Department of Community Health }

9th March, 1998

SI.

No.

Name

1.

Dr. N. H. Antia,

Director,

Foundation for Research in Community Health,

Pune.

2.

Dr. Abraham Joseph,

Professor and Head,

Department of Community Health and Development,

Christian Medical College,

Vellore.

3.

Dr. Jayaprakash Muliyil,

Professor,

Department of Community Health and Development,

Christian Medical College,

Vellore.

4.

Mr. R. Gopalakrishnan,

Secretary to Chief Minister and

Coordinator, Rajiv Gandhi Missions,

Government of Madhya Pradesh.

5.

Dr. Ashok Sharma,

Divisional Joint Director,

Department of Public Health and Family Welfare,

Government of Madhya Pradesh, Indore.

Signature

....2

: 2 :

SI.

Name

Signature

No.

6.

Dr. G.V. Nagaraj,

Additional Director of Health Services,

Government of Karnataka.

7.

Dr. S. Subramanya,

Project Administrator and Ex-Officio Additional

Secretary to Government,

Health and Family Welfare Department,

Karnataka Health Systems Development Project,

Bangalore.

8.

Dr. Murugendrappa,

Joint Director (Malaria & Filaria),

Department of Health and Family Welfare,

Bangalore.

9.

Dr. Mary Olapally,

Principal,

St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore.

10.

Dr. Dara Amar,

Professor and Head,

Department of Community Health,

St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore.

11.

Dr. M.K. Sudarshan,

Professor and Head,

Department of Community Health,

Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences,

Bangalore.

12.

Dr. D.K. Srinivasa,

Consultant - Medical Education,

Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences,

Bangalore.

.... 3

: 3 :

SI.

No.

Name

13.

Dr. J.S. Bhatia,

Professor - Health Management,

Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.

14.

Dr. Ravi Kapur,

Visiting Professor,

National Institute of Advanced Studies,

Bangalore.

15.

Dr. Jayashree Ramakrishna,

Additional Professor & Head,

Department of Health Education,

National Institute of Mental Health and

Neuro Sciences, Bangalore.

16.

Dr. Mohan Isaac,

Professor and Head,

Department of Psychiatry,

National Institute of Mental Health and

Neuro Sciences, Bangalore.

17.

Ms. Sujatha De Magry,

Director,

International Service Association,

Bangalore.

18.

Dr. Sukant Singh,

Consultant - Community Health,

Christian Medical Association of India,

Southern Regional Office, Bangalore.

19.

Dr. Pankaj Mehta,

Associate Dean and Professor and Head,

Department of Community Medicine,

Manipal Hospital, Bangalore.

Signature

.... 4

: 4 :

Name

SI.

No.

20.

Dr. C M. Francis,

Consultant,

Community Health Cell,

Bangalore.

21.

Dr. V. Benjamin,

Consultant,

Community Health Cell,

Bangalore.

22.

Dr. Arvind Kasturi,

Assistant Professor,

Department of Community Health,

St. John’s Medical Colege, Bangalore.

23.

Mr. As Mohammed,

Assistant Professor of Statistics,

Department of Community Health,

St. John’s Medical Colege, Bangalore.

24.

Dr. H. Sudarshan,

President,

V.H.A.Karnataka, Bangalore &

Honorary Secretary,

Vivekananda Girijana Kalyana Kendra,

BR Hills.

25.

Ms. T. Neerajakshi,

Promotional Secretary,

Voluntary Health Association of Karnataka,

Bangalore.

26.

Dr. Kishore Murthy,

Management Consultant,

Bangalore.

Signature

....5

: 5 :

Name

SI.

No.

27.

Dr. Ravi Narayan,

Coordinator,

Community Health Cell,

Bangalore.

28.

Dr. C. Siddegowda,

Additional Director - AIDS,

Department of Health and Family Welfare,

Bangalore.

29.

Dr. B.Y. Nagaraj,

Joint Director - TB,

Department of Health and Family Welfare,

Bangalore.

30.

Dr. S.M. Junge,

Joint Director - Leprosy,

Department of Health and Family Welfare,

Bangalore.

31.

Dr. G. Gururaj,

Head - Dept, of Epidemiology,

NIMHANS,

Bangalore.

32.

Dr. Gita Sen,

Professor - Indian Institute of Management,

Bangalore.

33.

Dr. Lessel David,

Danida Team Member.

Signature

...6

: 6 :

Name

SI.

No.

34.

Ms. Sangeeta Mookherji,

Danida Team Member.

35.

Ms. Victoria Francis,

Danida Team Member.

36.

Dr. Kris Heggenhougen,

Danida Team Member.

37.

Dr. Birte Holm Sorensen,

Danida Team Member.

38.

Dr. Bjarne Jensen,

Danida Team Member.

39.

Dr. Suresh Ambwani,

Danida Team Member.

40.

Mr. Esben Sonderstrup,

Danida Team Member.

Signature

‘A-

«•

—Z

Cow H

i /JL - * 4

IIl "

1! l-^ny G _LAV-'';m i ‘ f- '.

PACTORd i

r-r ■

■illlb

• Lack

i 1

in Formation

of

MiflBfilfRFS

. pjxaVALFNT

4

i

h

. PoftR

Pe.kcef>rion

• Poor

Health

. Lack

f'EHAVJOUR’

Risk

of

of

Risk.

6E£kiN<

behaviour.

EMPOWERMENT

/

• Health - Low PRioRiry,

:■

i

•

iNBQUALiTy - PiNANCML

• Q lai

rfvi

;• » .

[a

. IW bVSTR)AU&ATi6W

• cultural ' SHOCK'f£)

u • Ji

I

T

'I- i

• IjiJiiE POPULATION

]A

•

:L

Iw

8 t.

QuoaRAPHICAL ARfiA.

•Diverse

cultures.

• HIGH ILLirERACy,

• > 45a languages

^ialscts

• urgent need

• Poor aids AWAREtflSj • PERHAPS

l>kfcASE *.

• Behaviour .change bEPsvps ow Too MA^y

«

<

I

Jj .

k-

'• ’''

'•

ON<E

• MEt»'4AL CAR£

HCVv >

l> k.

H)V 4

I ?

If

I

i1 ;

'

• Social

1! ■ I ■'

‘' I

<

J- jI

I

.iMi ?

i W.r

C/n H/v

Crp’-

j

*

TO SINGLE* PAMiLJE^

fl

Ik 5

|b

Ii

J

ll

jJ^aNONli cA L

OF

. COST

- UNMAMAGAiilA

MANAGEMENT

4

OF

• Loss

MT

H. Ne

ti

*• I

<.

Income

m'reoT

l'+

. M vltFsector»al .

A.f PR.OACP

1

■i! ■

f

■

1

fe ll■4

rule

SPiA’-L

J ' '.

=

to

RVLE

TO

C WORK?

biVIIDE

1

■• < i

! '1 ■ i1'* ’

',

vjl’.^r

’ A BEARANT ATTfT. “

■

;

•■’. "I ;r : I

r„

«jjtLAy

LACK

r.H

oru

ZF

®f

1

TIME

i 1 Or™ ’ <4i®

, Mi |4 .;

■ «sP

w

tp»

■■■ h !

4^4

LARQH.

motTvation.

Inertia.

ib Care 4 event relat*z> prev*

I

J.

Ti»f

; SfeiHJw

F

i LE x i B) Lipy

PoftR

In FRASTJWCF

• Small

• Less ka Crass RotfT xv>port;

MU LTl SECTOAIAL

M r’

jWh ’

?»

NGO

C'f^)

ACUs C R £ t>) & i Liry

f

i

L6ST

DIVIDE.

'I ?' r

it;

'

h

ain-SSi

’4'd1 fiw

4,

htfi 4ij^drir

■t

I'

lib’'

It' ■

jww

WiR

hO

!• i grass

'I

i*11 r’lJ

’A-

f

&;

■'.

r,

AxS^MRcEs

.'/?

il.l'

- IWMte

Qurekfi

l/u Ul Ki

i ■ ■■

t

■

HIS

-b

77 M--, ■<-.".■ '

It"}

i

• i ■ MPliinr'

• HIGH’ M&TivATia k/ lySilS

i

• V, *

r’ ’r

|i

H

•More ;N H. P^o^aTM

-1

<HAN

CARE,

Health

pu/s

Mi ii i

I

1

W'pl’ fejiii '.PLUo N6O +

llilj >m

'•ji I

«si

lid'

ni'

iB

Wil

Wil

fl

.-r

'•

'»

i

'

.

-'3

n?- ■

nJ hi •

<1

V

i . If

r-

CAKE.

iv)l'.P)<Au

h|'l

Go

. ' ’. rj r»7 rina!..' ..

•

f

<

PAT1SMT.

Qo

bAS’zj>

.

Mt

"''GO «

G '’ '/N . G. LI.IM^

Imi'./• biSSASE. AVMAR&N2..

ao

N<?0

BlectioWic. *<8hi4

fix

NC&o).

l 'J.

!

i »! - ? r

Go

AGENT

'i

change hjv

op

v< ■

y

WHE^ CAN

IT ft£ EFFeCTl’vE/

■ '.

;.

I .

L j« i> l

?

i

• Commit hoent

i

i

equal

PartneremIp.

. OPTifOUM

FLExiBiL>TX

r-

» SELF- SUFFj’cjENCy _ (pf REcTlOf^)

► I

A

-Mr!-.

M Go

l.h

H ■•

s [ ■

Pl

N GT {,70 R K)N^

- V iyA L

- EXPBRJENCH’

•

PAz,o

POOR ^^TAlVABklTy

• JaaIoua^

• ^'VckJay^,

iH’ *:

CjOMMen

H

i -rv ,

Ci!

J::

I,!

• FLy

By wiSHT

oPERBToAs,

• lyf Rk tJONE tEsi Cs;<;>J+ DU Wtop.CLAIM

- NW>V ? N<0 -

• CORPORATE

NEC's. ? Cbarȣ.

I

14

* A-

h ■

?

cultured

'

z UNG LIS H

. Hi fl

.Local bMo-PMoaMt\

« Program

CHOICE -

? MONi Torino

. Target

groups

Lntens'ive

^^caToRa*

!

Focus

OA/ta

- CAPTIVE f P»SAbvA!VTAGED

• CsWi.

'

• PWA* 'MeSt^yu.

.

/f.

I

• E h->|>©tNer>nent - > blame others

Agencies

Life Piffkvlt.

1

i

X\ b E P£N DENCE

I

b- i

.

I &.

"

«

I

I

Visibility

PRo^'^TE

•

SUFFERS

.

Favouritism

.

Poor

I

z Promise/ 1.VRE

FROM

i

next

'

5 yr

GONSORT/t/M

A«<iste4

h/ACO

but.

?vacp ,

AASlsrRJb

NA\y

•!

•\

Vi

J»)an z We h^e.

WHO

e

id?

2»<5 NO a

-for

you

OR.

•PRobuirivrr^

ajcnc^

DO

A

©N£ o{

^xecuii'n^

ai v

Pay!

’’no

* PaRxJ/vSoM^M.*

(Be

1

I

■

-

but

PRobUcTrv/yy — /hfC£/vT/vfi

Poor

PONb/NcS AGEMCtC^

In The

CWAM^e TMe'sHi^

<

-

't

6vMbR«M».

PUA/fc>Al$

To Halt

ttMfa

.’a

Not

0^71/1 H — ■4^ --'

,'( V •

K

Uh*

■■

■*■■“'

(1'

4

•^*

\

\

V-.-...

4—imrvW-

/w.

.

._■,

-y -ftC.

I

7b e

C ©NTI NP<^

■i

o4 M

PicH c

IM

S <S> C( A- C-

h. bucnnoN^^

y ocr ri on n<~

It

I.

IO «

TP-A iFl »N 6

I

I

Dll/IOUftC

*

I

I ■

H<6>rt£ir

r»e

Pouieie

I

OF-

■J

P UH Lr lONftt* 4

■'

I

I

!

RHHfl-E>/2-/rar»0A/

I

IN

rfpu rnrtoAj

)

J

J

PoAme/^

/6/rr4>

.. 'Uv.ijrj.-... .:.

. PflLi-iftuVzr

w H? H ’

C f\«t

D ecisi oM

IN FOMec>

i

Q uat/ny

f= fA/ft/V 6/ftlL

1 *

Phz-z-inr ii/e

cftKe

I) ?P.0PH'ItR

3-) coftimo^

i TO Bf fo/Nri/Ma^

|NF£CTIOA/S TReATEJi

symptom control

!’

£fj Serious

iNPecno/^;

TRenreb

V

.

^yf-.'T^Sftyrar. -■

‘F \

Home*

I’

3b

$

I

B BSfB t-

’• c

-—4;-UatiX4U.^2XS*».-

tflRE.

|

I

I

V

M

U

*;i

t(

;

I

I

’ X

->!

\) pr U/ifK H1D5

Be/Nt,

2-) ro

Peer

ro

3j

ro

H

M

J

I

A|Oi faf

oibHir'j (/?Fspecr

FRotfips

OPTIf^ufYl comPofc*

HW<hieMB TO AIP5 l//CTI/v>i

:i

i•:

Hopi^

SMPROAT

I A-ND PfRiOA/flc

j

4 CHOICE

e-fAorioNnt-

st/ppoftr to

■'

fl.Nc>

i

i

I

CrtRF C-,>VEft.l

1

'

IaJO8K|?R

- (- OUNifi t-COft-

' PhiroKtL- cnns

£ <£u / pmenr

Pun cn ©/><; A(4

I:

VO LU

- re*

1 V A

COi^ Po ne f<(

op

Home- Cftne

X NVRA/N4)

“

c O VN 5

/N 6

Pasro^n-e

- SOC/^L- SCCPpOJ^r

Po A.r

IN Comc74?N^^hriO/</

WflrF/Mftc

shPPoaf

Rb“L^

S6>C/ftC- CO^^^P'

■ I

C0Srj>

I'toSpI F4-U

*7

i

^74

1/

Ji

j,-..

•

-J

/-

■xh ■

n.

ft&VhNThfoe*

nos f>/rA<JS*ri©A<

t

PF

*)

He

h^s 1 co /mtRo t/ the ou cnrioA/

o

WtiZ

(oM MUNirLj

14 pi f>

S')

FP-Of*

R e t> ucrioN

CO M rytc/Hir<i.

of

3ne»r»tn>

-:

I

<1

D/S nt>VftNTAC7EJ

peNiftu

OP TP EPtTMCAIr

V

HomC v nits

,i

1

i

m ftiNTentrHce

4;

VO L.U nF6ep-j

S')

S FK, Mb•'

A

’

4

|

I

A

r

C AHP

OP

,f .

. / - <.* >,<>*>•« <'

I

>,.w,

Ptf/AT^

co n c e^zt

0_e h©s p/c

Nee d

u PP&Kr

(n Pi O U P3

f^t=~ G, 11//<

- Tkavi rio/^frc.

gottT

DlSf/Vst?

PoLLBH

Nfi^fcs

; PKncncnc

/n dail<^

frwnrnNCG

TAiycK

- KFFP/N£|

- tMtg^cnoN

7

oH/WfO^

Henur^ i<iirsr*

- rsus/j^eii

^©r<oA/^ c.

c= ^r/N e>j

S ca ppo^r Oug/^t,

Petr#

v1'

L-

*b< "T

J

X.

(niveK £Q(»J

-

Aoz-f

0 •P ftfmitroag2J

CftAJRS7<

Aoti?

P e V^LO P&Zrt T'

jf^E’ H IV P°^* 7\Vlf

I

omr

J Msk

D I P de S5I0A/

op

rmeNr

t-O SS

*

shi r

u/m

im

AFiFo/M£iAc/ry

peer & &

N Co/MTpPtusO

^OU7

• -

Co/SPLlC)

T (.(.HL-’b

...

HU-

* y

-x

c Mir o p c

•{h ’.

t r\

I

IJ X N C

z_) Heep

ft C /?

TO

anticiPft-re

re ft ch

q)

$TftR.r«»l^i TO i-OP^MITti

inu l.t)Pt £" P«0 3£.fc^

1

i

f) £ NJievnccz**'-twf' *P^o

i- .

<■

V

i

I

DevEtoP

J

I'!

Is

<

I

]

■

s■

1’Y ‘hif!

COflNb,

h)

COQN iCLLINtj

0

M cr woAKj^t,

He^ti

4

Q Wi ,K SlAdj^Y^

GiROOPJ •

Public hbalj/-/

tbOC^T/ 0/\f

Cwi H

AajD TflA/Alz/vS,

^ SS CjES

B. CUA l L SA! SSS )

• S'C0/>6 OF

•

POVOCACy

PCLUOC PfFP c tai

FoQ Public mb a fry

7/laining,

Poli Gy

P P P Ad a cjjfs

•

to

STP-FAJG,7J.I&A/

OT^FA

7'<Q<9//V//y

^FFTCg

TAG,

• ^rP£SC co )rH

Ppl Qualietab

estabdsa,

school

Public pcacth (

of

m^tj -

2>ISCI Pc/AiAAy j

9

PmiL " 2 y&w

(■ouAse

(c/MKeb Yq f\

ZTATVATOAv Oaji \jC/LS

■ Basic U6> t ps,

»

/VOUCT/^A/

E xPcoajn6)

&.

Distance

^16 bC Qopeaj

---------- ■‘W

7~ A

jy^r. l>Wo.

(Pe^xfw

a

S'f&vgfi

G^i^ov) p Jl

CcWl

Pgprjposg op

A - Access

&•

c- r/AMA^HeAJT-

or-

£>A7A ^keMGRATOAS Tb

A/u/uyse Jut fuse Data at aoc4<

*

4Eu^C&

He ams op

&

G-Gmgaat/as^

?Acw bM

^ulck

deiPoAJse

GA^WAj0ees

• daeArsA oriury

• CjUAtga

z/o\/o4ue«GAjr

’ £MeA<xG/ocy fteAcr/©A>• NoTIUAT/oaJ .

•

/M90A.W A1I0A3 M6eas

• ZoCAK /OGGZ> op /A)9©<«At/«M

• Stats / n)At/oaj^c AJGsi).

He-tHoOS

op

Z>ATA OTlCl&Mod ftT

6euec.

CoNHuMiry

PuMiiive

• >J/

P.e£PoK)se

QoR

1

•

Accou^e^ry

/KJt(5A5Gc.roAA<

Quaut?

MAlOAi/^a.

If^oMvA-VOfQ

~CecH*D/qu6&-

2>cPFeAeAJT

«

CA?/A>6.

UlTM

I

*

C\.

X^oCAt.

CLocceafG^

«

l^^oANATlOf^ i

Pu&LIc

^eAixu

P^O^L£’ti£

b^bGl^tlFl&i

;

• PAT£AAamJUe

SYZTGN&

^>»AH/M€

*

^GACTH

£7AeAj&.TweAJiAJ&.

< i>eu6A0P/^^

JjDC/MJLy .

.

Dp

To

If^^oAHAriOfO-

C.OAAj^fjf

• bex&MiMMa <5^Gt^xiA-L.

p-eebMCK. swrens

K&SeAAO^

IHPCGHGAJte^

• £HPok5£A^^

«

^SALTIA

AesezwicH

III ■l1fllnB1iM,w|———

P£fLcep‘fioKis

ci/a?oaaa

PP Ao PA/OA1C 'Z’o

hcvori

Pop.

iM^wAvioti.

^D^ITopjf^c^

^o- of ^.ecoAZ>£ •

^oth bi/ieaffo^>

CoHHorf H^Gmecrofi.AL bM& 9^^

I5j (j ROUP 3

me

P£cerrTMi,l$/ir/ofJ irr tHB HeMrH

Hnp HoSfi-rAt- pynpot'y.

Pflfi/cpitytr Pkf jT/rsnrvnorJ To pe e/rcouMe-ej)

Pooiet- (,$ driver1 /nretioj t>F Trips, x MohW

Hepp THe^ TO tpermpy THerf. r/eePi, PPr PPior-ines

PF? IaJoPjc-OUT plfiri of PpiTlori za/ ficcof-p

iPrrH

With

THP SrtVPmo/J

to

Kfrf-rJkrPtt.Pi'-

$i>tt-PiN6- of

(VifMfteAS pF

PF-r

' HefirJff- l/J PLfrJrJlrJG' TO P-&Of> irJ J>eci5lO|M MfiXIAte' To CrJT><Jf£ pfifT vpfiTiir! OF rJ<rO,

TrJTFp.rJfiTK>rJAi. Pr'P fl-rref^es

P

- TO P-P^p PRt pt> Cn/^e up

PPoa-P P€\j. ppcrixirrei/ ^>pec\f:ic. PT^irH

pP&.t ir/jpeK KeMM> Pf-(r-

* ft trf 0^0

~

Of

^uTONotfw/

PeOfUc

Ho $f>rrftL5 ■•

c(pj &e

/w-use’ op po^e^

pet-P 7^ PeAI- ■

PPX

U5PP pee j:^$Tifvrio^s rfie-Hr

/AJ f&vrry /A/ seytuices

r>

op Ho$>f>rtALs

])& cerJ-rffir^^FP

1

Cduop 06 Dc/je ^y Co^T\TVT^& fEOftf

F^om T'Hf M&(6H&>ut-Hoop.

USZK pees

'fo e>e Ct^n-eJ>

pfirriz/rt

^fLfirfP, [(■<■■

frfijj)

i.

WAi/JT'eNA'f'JC&) '

fOptUS ^HoopD tPe

d

^ifAP^

rd Off ASM M&JArM^

f’lptiz. RfticwA,&ei-W.f

Pnp fcgLe-Aw).

*

Coaiai <Ja> i-ry ptSAot-fi Sysret'i

I

7>IS PW A^trAS-e-P

Pf- SAS.

(NlT<n-reP

M /Mx4<aV >Zy V&AAvCi^d-) yn ^1§C

* ."TT^

^U^or/ f

* C OhCcpkA&l^&k'Bn

2? /'rex/- AcJiviJ?

r^&ZaJi sy^k'p be&)<2£'K

4y pa^/\

b^ll\

^>k^- 'fvrivi oa^cJj^csn i/s.

Vis£a\

• Or^a^saJSsA ak fbcaX (jqajqJL ~

C£7MXVtu Zfee. y CjTCUM' po^c^aycjub

CjOIa^'cA' Igz/.

CjOCoJ- Iq<O(J2^ </Kejzjjjz

<*■ (i<Jjxc/Yy

40

‘A? C^cA-^^'

^Po

•

-l4?

*

(yij /e Co Ca^>

•

/UycJZcu __ / / - l^u^

/

ojjooa^m^

— /V)Zj2^/ */© TtAxZ^ 'tX

l>0Q/Il^AA’ trtu*’

t) hvixx^ ~/-o /xaJg

1/ fcc-s CZexvfi (5>i

y/l 6JX4^as^v

a^^YO^vi^(& (saJ- oA©

idjzxp/ V° T^'

]^Mc

c 6C-

4>e^cz

C^l^-pol^e^'^ &b*d<&(gjy

•

^C^-uiAiiSh-J a/^s^iiCi

J^cMs^i.,-i

PtJ't' ('ovd —

ppt Q^locdo

• G)ffi<^ /b

I/Ca loe^tr cJkjua.(uu < "

*

B

kM/).

V* 6) )<. K. pyc^eiL/~:

(j&UcJj 6CG'sfrfX

* ^JCdA^XX A?^o

&UA

EQUITY

Commitment to equity

Support for the “All” in

Health for All

* Benevolence

* Non-maleficence

* Justice

* Autonomy

EQUITY ORIENTED POLICIES

* Selection, training and deployment of health

personnel

* Reorienting training

* Selection and use of technologies

* Selection of populations

- greatest burden of ill - health

- disadvantaged and marginalised

* Gender sensitiveness

* Reduction of health disparities

environment: Determinants of

Health

* Physical

* Social

* Economic

* Political

environment : Hazards to

health

Chemical

* Microbiological

* Physical

*

*Local

*GlobaI

Con H

WARNINGS

SINCE 1975

GOVT. EXPERT

COMMITTEE - 1996

ON

Srivastava Report/

ICSSR - ICMR Report,

JNU / FRCH / VHAI/

CHC.

PUBLIC HEALTH

SYSTEM

(GOI / MHFW)

(CRISIS^

IN

PUBLIC

HEALTH

SECUNDERABAD

MEETING - August 1997

EXPERT ARTICLES

-1990S

Public Health Crisis and Challenges

EPW/NMJI

HA/HFM/Lancet

Malaria Report

(CHC/VHAI)

ICHI Report

(Network of Public Health

Professionals

Govt./NGO/ICMR/NPs)

opinion

polls

BANGALORE

DIALOGUE - MARCH

1998

Public Health

Crisis/Challenges/Opportunities

(Dialogue with Danida Health

Sector Mission)

CRISIS IN

PUBLIC

HEALTH

SYSTEM

BREAKDOWN

POLICY

PRIORITY

AND

FINANCING

CRISIS

IN

CRISIS

IN

PLANNING

CRISIS

IN

HUMAN

RESOURCES

DEVELOPMENT

’ CRISIS OF DATA /

HEALTH

INFORMATION

>

PUBLIC

HEALTH

(Dimensions)

CRISIS

IN

RESEARCH

AND

PROBLEM

ANALYSIS

<

CRISIS IN

SOCIETAL AND

SOCIAL CONTEXT

CRISIS IN

ENVIRONMENTAL

CONTEXT

PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM BREAKDOWN?

SHORTAGE OF WORKERS / DOCTORS

REDUCTION IN BUDGETS

OVERBURDENED HEALTH WORKERS

(ANMs - EXPLOITATION)

CORRUPTION / SCAMS / MISUSE OF FUNDS

POLITICAL INTERFERENCE

DECISION MAKERS WITHOUT PUBLIC HEALTH

COMPETENCE / ORIENTATION

CENTRALISED TOP DOWN PLANNING

CENTRE / STATE RESPONSIBILITY

- AMBIGUITY

• INADEQUATE / UNREALISTIC PLANNING

Source : Secunderabad Meeting - August 97.

MARKET ECOKOMY IN HEALTH

*

TOP DOWN PROMOTION OF

TECHNOLOGICAL FIXES!

*

MARKET INTERESTS IN DECISION MAKING

*

INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC HEALTH

COLLABORATION / COOPERATION

Often becoming subservient to:

* AGENDAS OF VISITING CONSULTANTS

* RESEARCH PRIORITIES OF COLLOBORATERS

* “GUINEA PIGS” for Research

* FUNDING AGENCY CONDITIONALITIES!

* GRANTS TO LOANS!!

*

ILL HEALTH EFFECTS OF NEO-LIBERAL

ECONOMIC POLICIES

(From Solidarity to exploitation!!)

Source: Secunderabad meeting - Augus: 1997.

HEALTH LOBBY

NETWORKS

•HEALTH POLICYCELL

IN MH & FW___________

- Interdisciplinary

- intersectoral

- Apex body to translate policy

into action

FOCUS ON

* Equity

* Sustainability

* Health as Right

* Gender Sensitivity

* Health central to

Decentralization

STRENGTHEN

PUBLIC HEALTH

EXPERTISE

* Indian Health /Medical

service

* staff college for health

policy

makters/administrators

* New short courses

* Reorient PSM

I

HEALTH PRIORITY i

HEALTH BUDGET T

DEPOLITICISE PUBLIC

HEALTH

CHALLENGES

MONITOR EFFECTS OF NEP

ON HEALTH.

>

CONTINUING

EDUCATION

OF

HEALTH TEAM

ANMs

Other Paramedicals

Nurses

Doctors

SOME

CENTRAL

LEVEL

OPPORTUNITIES

9?

VOLUNTARY

SECTOR

◄—

NEW PARTNERSHIPS

FOR HEALTH

PRIVATE

SECTOR

HEALTH AND

EDUCATION

SECTOR LINKAGES

*

Folk media strategy

* Community based media

approach

* School based Health

Programme

* Youth involvement in

National Health

Programme

OPINION POLL

MARCH 199S

b

STATE / NGO

INVOLVEMENT

CELL

PANCHAYATRAJ

AND

HEALTH CARE

AREA

HEALTH PLANNING

DISTRICT / TALUKA

>

INTEGRATED

HEALTH

INFORMATION

SYSTEM

*

REGIONAL

DISPARITIES

*

RATIONALISATION

OF MIS

*

STATE

HEALTH

PLANNING

CELL

IMPROVING

PRIMARY HEALTH

CARE

INTER

SECTORAL

COORDINATION

* MISSIONS

* APPROACHES

* STRATEGIES

4

STATE

LEVEL

OPPORTUNITIES

ENHANCE

FORECASTING/EPI

DEMIC

SURVEILLANCE

*

HUMAN RESOURCES/

COMMUNITY BASED

*

ANM-CMEs/ Updates

*

ESSENTIAL DRUGS

SUPPLIES

*

HEALTH ACTION

SUPPLIES

PRIVATE SECTOR

- Recognition

- Involvement

- Regulation cost &

quality

- Reorientation

PUBLIC HEALTH

ORIENTATION

Orientation course

Short courses

CMEs

Reorient PSM_______

Public Health Training

Institute/Network

4-

HEALTH WATCH

(OMBUDSMAN)

Enhancing

Accountability to citizen

- Watchdog/countering

* corruption

* commerciali sation

* political

interference

* Market Strategy

-

HEALTH LOK AYUKTA!

PUBLIC HEALTH IN INDIA: CRISIS, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

(with particular focus on States of Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh)

Group I

Group II

Public Health Education &

Training

Health Information System &

Public Health Research

1) Dr. D.K. Srinivasa (Chairperson)

2) Dr. Abraham Joseph (Key discussant)

3) Dr. Murugendrappa

4) Dr. B Y. Nagaraj

5) Ms. Sujatha de Magry

6) Dr. M.K. Sudarshan

7) Dr. Dara Amar

8) Dr. Sukant Singh

9) Danida Team Member

10) Danida Team Member

1) Dr. R.L. Kapur (Chairperson)

2) Dr. Jayaprakash Muliyil (Key discussant)

3) Dr. G.V. Nagaraj

4) Dr. Ashok Sharma

5) Dr. G. Guru raj

6) Dr. Ravi Narayan

7) Mr. As Mohammed

8) Dr. Gita Sen

9) Danida Team Member

10) Danida Team Member

Rapporteur : Dr. A.R. Sreedhara (CHO

Rapporteur : Dr Denis Xavier (CHC)

Group HI

Group IV

Decentralisation in the Health

Sector (including Panchayatraj &

Hospital Autonomy)

Coniniunity Participation &

Communication (including IEC)

1) Dr. J.S. Bhatia (Chairperson)

2) Dr. N.H. Antia (Key discussant)

3) Mr. Gopalakrishnan

4) Dr. S. Subramanya

5) Dr. C.M. Francis

6) Dr. Mary Olapally

7) Dr. Kishore Murthy

8) Dr. H. Sudarshan

9) Danida Team Member

10) Danida Team Member

1) Dr. Mohan Isaac (Chairperson)

2) Dr. Arvind Kasturi (Key discussant)

3) Dr. C. Siddegowda

4) Dr. S.M. Junge

5) Dr. Jayashree Ramakrishna

6) Dr. V. Benjamin

7) Ms. Neerajakshi

8) Dr. Pankaj Mehta

9) Danida Team Member

10) Danida Team Member

Rapporteur : Mr. Murali (CHC)

Rapporteur : Dr. Rajan Patil (CHC)

Z

/

H

Workshop on

PUBLIC HEALTH IN INDIA : CRISIS AND CHALLENGES

: with particular focus on States of Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh

{Held at St. John’s Medical College, Department of Community Health }

9th March, 1998

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS

SPECIAL INVITEES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Dr. N. H. Antia, Director, Foundation for Research in Community Health,

Pune/Mumbai.

Dr. Abraham Joseph, Professor and Head, Department of Community Health and

Development, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Dr. Jayaprakash Muliyil, Professor, Department of Community Health and

Development, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Mr. R. Gopalakrishnan, Secretary to Chief Minister and Coordinator, Rajiv Gandhi

Missions, Government of Madhya Pradesh.

Dr. Ashok Sharma, Divisional Joint Director, Department of Public Health and

Family Welfare, Government of Madhya Pradesh, Indore.

Dr. G.V. Nagaraj, Additional Director of Health Services, Government of Karnataka.

Dr. S. Subramanya, Project Administrator and Ex-Officio Additional Secretary to

Government, Health and Family Welfare Department, Karnataka Health Systems

Development Project, Bangalore.

Dr. Mumgendrappa, Joint Director (Malaria & Filaria) , Department of Health and

Family Welfare, Bangalore.

PA\R TICIJPA NTS

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

Dr. Mary Olapally, Principal, St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore.

Dr. Dara Amar, Professor and Head, Department of Community Health, St. John’s

Medical College, Bangalore.

Dr. M.K. Sudarshan, Professor and Head, Department of Community Health,

Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangalore.

Dr. D.K. Srinivasa, Consultant, Medical Education, Rajiv Gandhi University of

Health Sciences, Bangalore.

Dr. J.S. Bhatia, Professor, Health Management, Indian Institute of Management,

Bangalore.

Dr. Ravi Kapur, Visiting Professor, National Institute of Advanced Studies,

Bangalore.

Dr. Jayashree Ramakrishna, Additional Professor & Head, Department of Health

Education, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore.

: 2 :

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

Dr. Mohan Isaac, Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry', National Institute

of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore.

Ms. Sujatha De Magry, Director, International Service Association, Bangalore.

Dr. Sukant Singh, Consultant, Community Health, Christian Medical Association of

India, Southern Regional Office, Bangalore.

Dr. Pankaj Mehta, Associate Dean and Professor and Head, Department of

Community Medicine, Manipal Hospital, Bangalore.

Dr. C.M. Francis, Consultant, Community Health Cell, Bangalore.

Dr. V. Benjamin, Consultant, Community Health Cell, Bangalore.

Dr. Arvind Kasturi, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Health,

St. John’s Medical Colege, Bangalore.

Mr. As Mohammed, Assistant Professor of Statistics, Department of Community

Health, St. John’s Medical Colege, Bangalore.

Dr. H. Sudarshan, President, Voluntary Health Association of Karnataka, Bangalore

and Honorary Secretary, Vivekananda Girijana Kalyana Kendra, BR Hills.

Ms. T. Neerajakshi, Promotional Secretary, Voluntary Health Association of

Karnataka, Bangalore.

Dr. Kishore Murthy, Management Consultant, Bangalore.

Dr. Ravi Narayan, Coordinator, Community Health Cell, Bangalore.

Dr. C. Siddegowda, Additional Director - AIDS, DHFW, Bangalore.

Dr. B Y. Nagaraj, Joint Director - TB, DHFW, Bangalore.

Dr. S.M. Junge, Joint Director - Leprosy, DHFW, Bangalore.

Dr. G. Gururaj, Head, Dept, of Epidemiology, NIMHANS, Bangalore.

Dr. Gita Sen, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.

Dr. Lessel David, Danida Team.

Ms. Sangeeta Mookherji, Danida Team.

Ms. Victoria Francis, Danida Team.

Dr. Kris Heggenhougen, Danida Team.

Dr. Birte Holm Sorensen, Danida Team.

Dr. Bjarne Jensen, Danida Team.

Dr. Suresh Ambwani, Danida Team.

Mr. Esben Sonderstrup, Danida Team.

Io

PUBLIC HEALTH IN INDIA: CRISIS, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

(with particular focus on States of Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh)

Date

9th March, 1998

Venue

Department of Community Health, St. John’s Medical

College, Bangalore - 560 034.

Facilitation

Society for Community Health Awareness, Research

and Action (CHC), Bangalore in collaboration with

Department of Community Health, St. John’s Medical

College.

Objective

Interactive workshop with Danida Health Sector

Identification Mission

Timings

9 am to 5 pm

Programme

9.15 - 9.45 am

Session I

: Introduction to Workshop

Chairperson

Welcome

: Dr. V. Benjamin

: Dr. Dara Amar, SJMC

Self Introductions

Expectations of Workshop

: Dr. Ravi Narayan, CHC

: Mr. Esben Sonderstrup,

DANIDA Health Sector Mission

9.45-10.45 am

Session II

: Introduction to Theme

I. Crisis & Challenges of : Dr. Ravi Narayan

Public Health in India an overview

II. Core Values in Public : Dr. C.M. Francis

policy

Health

A

reflection

III.Clarifications / comments : Participants

■

2

■

10.45-11.00 am Tea

11.00-12.45 p

Session III

: Group Discussions:

Identifying Opportunities

Group I

: Public Health Education and

Training

Chairperson

Key Discsussant

: Dr. D.K. Srinivasa

: Dr. Abraham Joseph

Group II

: Public Health Research &

Health Information System

Chairperson

Key discussant

: Dr. Ravi Kapur

: Dr. Jayaprakash Muliyil

Group III

: Decentralization in the

Health Sector (including

Panchayatraj & Hospital

Autonomy)

Chairperson

Key discussant

: Dr. J.S. Bhatia

: Dr. N.H. Antia

Group IV

: Community Participation &

Communication (including

IEC)

Chairperson

Key discussant

: Dr. Mohan Isaac

: Dr. Arvind Kasturi

{Each group will have a mix of participants from governmental, non

governmental and. academic/research backgrounds and some

members of the Danida team (see separate list)}

12.45-1.30 pm

Lunch and Fellowship

: 3 :

1.30 - 3.30 pm

Session IV

: Identifying Opportunities for

Strengthening Public Health

Sector

Chairperson

: Dr. C.M. Francis

{A member from each group will present key ideas & suggestions from

that group, followed by clarifications and. interactive discussions with

all the participants}

3.30 - 3.45 pm

Tea

3.45 - 5 pm

Session V

: How could DANIDA assist at

Central & State levels : with

special reference to

Karnataka and Madhya

Pradesh (Wrap up)

Chairperson

: Dr. N.H. Antia

Vote of Thanks

eSOnn h

...iyi

THE PUBLIC HEALTH CRISIS IN INDIA

1.

PREAMBLE

The Re-emergence of Mai ar i a as a significant public health problem in the country' since the

1970s and the increasing occurrence of outbreaks and epidemics especially in the 1990s, is

leading to an urgent reappraisal of the countrys public health policy and a deeper understanding

of the larger ‘public health crisis that has been evolving in the country' over the last two decades.

Some elements of this crisis arc:

LI

The Socio-Epidcniiological Imperative

There is a growing concern (hat the ‘situation analysis and ‘problem solving processes

in the past, with regard to communicable diseases control strategics have focused

predominantly on the techno-managerial aspects and less on the important socio-cconomiccultural-political context of the problem.

There is therefore urgent need to strengthen these dimensions of problem analysis

and solution so that a more comprehensive, effective, sustainable strategy is evolved

to tackle the challenge of Malaria.

1.2

fhe Political Economy of Health

There is a growing concern in health planning and health policy circles that the ‘market

economy often drives policy decisions more significantly, than rigorous socioepidemiological problem analysis. In National health programmes supported by

International public health cooperation and collaboration, this also means that approaches

and priorities arc often promoted that arc at variance from the recommendations of

National expert committees and technical evaluation reports. These distortions taking

place primarily because International public health linkages are themselves getting market

determined.

It is therefore important to understand the political economy of health in rz National

and International context before evolving strategies /programmes.

1.3

The challenge of Deccntralization

There is a growing concern that the country lias reached the limits of National, centralised

planning and with the recognition of the great diversity in situations and challenges at

regional and state levels there is need for a more concerted effort at decentralised

planning with a flexible framework that responds to regional needs and disparities

in the health care situation. This is even more relevant to National disease control

programmes especially when a disease like Malrria shows a diversity and locality in

its epidemiology .

1

1.4

The need to move Primary Health Care beyond rlictoi ic to grassroots initiatiy es

at community level

There is a growing concern that inspite of a National commitment to Primary Health

Care and to integrated, comprehensive health care approaches, National health

programmes arc loo vertical, too top down and inadequately integrated into the basic

health services structure. This also menus that policy alternatives or thrusts such as

Decentralization and Panehayatraj; community participation; community based

approaches; involvement of general practitioners and the NGOs (both voluntaiy sector

and private sector), inter sectoral coordination; and equity issues; arc included in the

formulation of strategics but remain rhetorical and not adequately translated into actual

guidelines for action.

There is therefore need to promote community based approaches that ultimately

strengthen the health infrastructure at the j’rassrouts.

1.5

The Threat of the New Economics

There is a growing concern that larger economic issues be they corruption at all Icxcls

of the delivery system or the more recent trends towards privatization and

commercialization and cutbacks in governmental expenditure on welfare is leading to

a continuous worsening of the general health infrastructure and human power situation

in the country affecting the sustainability and effectiveness of health care programmes.

This is much more than just an infrastructural development or ‘adminislrative/managcmcnt

lacunae issue and there is need to address this matter urgently since it alfccts all health

and welfare programmes in the country.

The effects of the new economic policies need to be monitored carc/ully and the

distortions in the planning process produced by market forces need to be countered.

1.6

he Urgent need for Right of Information

There is a growing realisation that health and development programmes in the country

have failed to make the impact they were expected to, because of the failure to generate

and sustain an awareness creation and educational process that would enable and empower

the people and particularly the more marginalised sections of the community to access

and utilize the services available and actively participate in the development and decision

making processes for the further evolution and growth of such strategics. Without the

spread of‘critical information leading to inadequate public participation programmes

. have floundered on inertia and red-tape. There is therefore need to support a process

of demystification linked to the Hight of information.

1.7

The need to Widen the Dialogue and Participation in the Planning Process

In the light of all these background concerns and emerging needs for cHcclivc policy

responses, and keeping in mind the urgent need to widen the dialogue and participation

in the planning process, we have reviewed the Malaiia situation and are oflcring certain

complcmcntary/supplcmcnlary comments and suggestions in all those areas where wc

feel (here is need tor newer perspectives and alternative approaches. We have drawn

upon the resources of a wide network of individuals/gioups who constitute an altcrnalisc

sector eager to share their experiences and perspectives with the mainstream plaiming

process.

By doing so wc hope that the voluntary sector would have contributed to the development

of some complementary strategics for action, to tackle the Malaria situation in the years

to come and actively supplement the efforts of the NMBP by the evolution of more

indigenously determined responses to problem analyses and problem solving.

Source: TOWARDS AN APPROPRIATE

MAIuARIA CONTROL STRATEGY

Issues of Concern 6< Alternatives

for Action

(A VHAI/CHC PUBLICATION)

Cor^}A 14-^. .t 7-

ISSJliSAiW HECOifMENDAJ'JONS

* * * * *

1. STRENGTHENING THE SOCIO-CULTURAL-ECONOMIC-POLITICAL

DIMENSION OF PROBLEM ANALYSIS

We recommend therefore that Health Economists must be actively identified and involved

in situation assessment and programme planning so that decisions about choices and alter

natives, and effects, are based on more rational economic and socio-cultural indicators.

However , we would caution that the 'economic’ criteria should not supersede other crite

ria and costs should not become the determining factor at the cost of social need and eq

uity issues. The plea is for 'economics’ to be an important complementary part of the

planning process but not the central core.

There is therefore an urgent need to respond to this lacunae and we suggest the fol

lowing:

♦

Behavioural science, approaches and socio-anthropological and socio-economic/health

economic research competence must be urgently built into the 'problem analysis’ and

'problem solving’ structures at all levels.

♦

Well planned, multidisciplinary operations research must be initiated and a more wholistic

effort strongly rooted in the social sciences must be encouraged.

♦

From Action research, practical, realistic operational guidelines can be evolved on all the

above areas and these then incorporated into the planning process, the training process and

the action process at all levels.

2. HEALTH EDUCATION

Creating awareness and building up a knowledge base amongst communities are the com

monly accepted forerunners to the involvement of communities and building up their ca

pabilities to act collectively and individually towards a common goal. Although the need

for the same clearly comes out of all the planning manuals, the commitment to this activity

is not adequately visible in terms of the time, manpower, efforts or budgets earmarked for

the same.

It is suggested that:

♦

There must be a quantum jump on the manpower, effort, time, resources and budgets allocation for Health Education.

♦

The most vulnerable and high risk groups are usually illiterate and have no access to radio

or television. In view of this, socially relevant and low cost alternatives addressing these

particular target groups should be used. Folk artistes, ilinerarant performers and street

theatre artists can be used to pass correct and specific messages to entertainment starved rural communities. These artistes can be employed under various employment

guarantee schemes or tribal development plans.

♦

Posters and videos do have their role but cannot be allowed to overshadow the other

forms of communication mentioned above because of the irrelevance to the most vulner

able and deserving section of the community.

♦

Teachers and school children need to be specifically targeted for specific health education

as the long term effects on their action potential are the most beneficial and effective.

♦

The Government has in recent years produced many useful booklcts/pamphlets, videos and

other useful health education materials. These are however used only within the govern

ment system. There is urgent need to make them available freely on a much more open

basis to all groups outside the government system who wish to be involved in Awareness

building.

♦

Communication centres within the voluntary7 sector may be encouraged to use these mate

rials, adapt them to local/regional needs, translate them into the local vernacular and work

on alternative approaches to communicate the key messages and facts in other interactive,

low cost ways.

3. DISTRICT PLANNING / DECENTRALIZATION

There is a growing realisation that the regional disparities / differences are so wide and the

development process including health service development so diverse that planning at re

gional level and at district level particularly is not only necessary but also relevant.

The whole renewed development and emphasis of the Panchayatiraj concept and structure

also emphasises the urgent need and opportunity for this.

Finally the concept of involving the grassroots community in the planning process now

considered to be more relevant, favours this shift as well.

To support this shift of emphasis, we suggest the following action :

♦ The urgent development of capacities and capabilities to undertake district planning.

♦ The urgent training/orientation of Health Centre staff particularly Mos in the ability to

make local plans based on local data and to involve the panchayat/community in the plan

ning process.

♦ The urgent training/orientation of emerging panchayat leadership to participate meaning

fully in the health planning process.

♦ Community level plans could be a short term goal to support the long term goal of district

plans.

L

4. LOSS OF PUBLIC HEALTH SKILL / COMPETENCE

The health programmes in India is being greatly affected by the crisis of “Public Health” in

the country, marked primarily by the increasing disregard of ‘public health competence’

and public health perspectives in health policy and health care decision making.

At Central and State levels there is increasing marginalisation of technical leadership with

public health competence, by their clinical counterparts and both these groups by lay gen

eralist administrators. Decisions that therefore need sound epidemiological and technical

background are now being increasingly taken by those who are not adequately qualified to

do so. Specious arguments based on management/economic/or other extraneous factors

are therefore being allowed to modify policy planning process.

This is further compounded by the inadequate support to public health training in the

country' whose growth in quantity, quality and diversity today are totally out of context of

the large needs in the country.

It is therefore suggested that:

Serious effort be made to strengthen public health training in the country;

Ensure that key decision makers in health care services and policy making bodies have

public health competence and orientation;

Encourage existing Public Health and Preventive and Social Medicine/Community Medicine/Community Health courses in the country to be more field oriented in their priorities

and skill development; and

Build inservice training and continuing education programmes for all categories of health

personnel in public health skills/knowledge including communicable disease control focuss

ing on national programme related issues.

5. CORRUPTION / POLITICAL INTERFERENCE IN POLICY DECISION MAKING

While techno-managerial and some epidemiological causes of programme inadequacy

and/or failure have been constantly highlighted in all evaluation/reviews/studies of the

‘implementation gap’ in national health programme - two extraneous factors that are im

portant, known to most researchers, experienced by most programme planners and pro

gramme implementors but inadequately tackled or even described because of the difficult

nature of the problem are the following:

a) Corruption manifested particularly at the time of tender, bulk purchase, appointments, and

transfers. These involve bribes and pecuniary benefits to decision making leadership. Of

ten there are well developed systems with the collections shared by a larger section of the

system.

3

b) Political interference in decision making at all levels even to the point of disregarding

technical expertise. This is the bane of Indian Public life today. The involvement of lob

bies of drug companies, insecticide manufacturers, irresponsible trade unionism, staff and

all sorts of extraneous influences seem to be at play when variances from policy statements

and actual realities are discovered by evaluators/researchers.

While these are part of a larger problem, we suggest:

A policy of greater transparency in decision making involving tenders and contracts asso

ciated with drug/pesticide purchases from the private companies.

A greater sharing of information / with increasing emphasis and legal sanction to right of

information. These will go a long way to allow consumer groups and social activists to

play the necessary7 watchdog role on the system particularly in these aspects.

6. INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC MEALTII COLLABORATION

Many major public health problems in India, are serious global problems as well. It will

require concerted national efforts, strengthened by regional collaborative efforts and the

resource support and linkages of international funding agencies and international Public

Health co-operation.

In the present global scenario and the evolving market phenomena, there is a growing dan

ger that funding will get linked to marketing of specific products or approaches at the cost

of a more integrated / comprehensive strategy.

We suggest that the international project linkages, project funding, should primarily

o

Strengthen national capacity to deal with ‘.he problem.

o

Build national infrastructure especially trained and skilled multidisciplinary manpower.

Be rooted in approaches/strategies responding to local needs and socio-economic-culturalpolitical realities of the country and arising primarily out of local experience.

a Prevent national strategies/projects becoming subservient to the priorities/needs of inter

national funding agencies, institutions and resource persons whose understanding of local

socio-epidemiology is often rather limited and who may inadvertently promote the re

search, training and programme agendas of their own institutions/agencies rather than be

ing supportive of local expertise.

a Ensure that projects/linkages are transparent and subject to collective peer group dialogue

and interaction among all those who are seriously involved and interested in the public

health problems in the country.

Source . Towards An Appropriate Malaria Control Strategy

Issues of Concerns and Alternatives for action

(A VHA1 / CI-1C PUBLICATION).

cS.0

K <4-6.11

STA TE OF PEOPLE'S HEAL TH IN HAENA TAKA

The Voluntary Health Association of Karnataka in collaboration with the

Government of Karnataka and the Voluntary health Association of India has

brought out a report entitled the '■State of People's Health in Karnataka’. It was

in response to the needs of the people interested in health of the people of the

State to have a reliable source of information. In 18 chapters contributed by

knowledgeable resource persons, the book deals with various aspects of public

health and health care services in the State and compares it with the situation in

India and the neighbouring states. The book has brought out a number of

recommendations to improve the health of the people.

Regional disparities

The northern districts are backward in health and development. It is necessary

to pay special attention to the people of the area, to enable them to catch up with

the more developed districts. 1It is also necessary to have a more equitable

distribution of health care.

Community Participation

The community must be organised to take action for health. The people and

peoples’ representatives (under Panchayat Raj and Municipalities Act) must be

trained to plan and take decisions. The health functionaries must accept the

rights of the people to plan, make decisions and ensure the implementation of

the plans.

Equity with quality

The quality of care, Governmental, Voluntary or Private must be acceptable.

There has to be equity, with health for all.

Value-based education

The education of all health personnel must be value-based with competence

and commitment and the training must be close to the people to be served. The

practice must be ethical.

Public Health

It is essential to have a public health approach, with improvement in the

environment, reduction in pollution of all kinds and health awareness among all

the people, leading to health action. Lifestyles must be healthy. There is need

for improvement in the quantity and quality of water supply and proper disposal

of waste.

chc/msword/c:/nagaraj/peokar.doc

Nutrition

Malnutrition must be corrected. This is especially important in the early

formative years.

Alternative Systems of medicine

All recognized systems of medicine should be supported, leaving the choice and

utilisation to the people.

Special needs

The special needs of the vulnerable groups such as the tribals, urban poor,

women, children, elderly, disabled and other disadvantaged persons must be met

urgently.

The special needs of the girl child and women during adolescence, reproductive

age and later must be met.

Mental health

Mental health care needs to be integrated with primary health care.

Rational Drug Use

The efforts to have an essential drug list and formulary appropriate for each

level of use and expertise must be supported.

The supply of essential drugs through a revamped Government medical stores

and supply system must be strengthened.

Information regarding Rational Drug Use must be disseminated widely among

all prescribers and users through well-thought out campaigns.

Voluntary Organisations

Karnataka has a large number of voluntary organisations involved in health and

development. Government should see them as equal partners. They should be

seen as innovators, issue raisers, trainers and enablers of people to take action

for better health.

The book is available with

Voluntary Health Association of Karnataka,

#60, Raj ini Nilaya,

2nd Cross, Gurumurthy Street,

Ramakrishna Mutt Road, Ulsoor,

Bangalore - 560 008.

v

chc/msword/c:/nagaraj/peokar.doc

I?

I;

Tiru ^<4 'UUrl

REPORT

OF

r

THE EXPERT COMMITTEE

ON

PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEiM

I

SOVERNMENT OF INDIA

M1NISTRYOF HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE

NIRMAN BHAVAN, NEW DELEU-110 Oil.

I

JUNE. 1996

t

Annex -1A

LISI OI- rilE MEMBERS OE THE EXPERT COMMITTEE

1.

Prof. J S Bajaj, Member,

Planning Commission.

Chairman

2.

Dr Jai Prakash Muliyil,

Deplt. of Community Medicine,

Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Member

r

3.

Dr Ilarcharan Singh, Ex-Adviser (Health),

Planning Commission.

4.

Dr N S Deodhar, Ex-Officer on Special Duty,

MOH&FVV, 134/1/20, Baner Road,

Aundh, Pune.

Member

Dr K J Nath, Director,

All India Institute of Hygiene &

Public Health, Calcutta.

Member

5.

6.

Dr K K Datta, Director,

N1CD, Delhi.

Member

Member-Secretary

List of the officials who assisted the committee

1.

Dr. Prema Ramachandran,

Advisor (Health),

Planning Commission

2.

Dr. Dinesh Paul,

Deputy Advisor (Health),

Planning Commission

3.

Dr. A C Dhariwal,

Joint Director,

N.I.C.D., Delhi.

4.

Dr. S P Rao,

Chief Medical Officer,

N.I.C.D.,Delhi.

ii

phsanncx.iloc

<So

H Ms -' 4-

CONTENTS

Description

SI.No.

1.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

2.

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER

1.0

2.0

Background

Introduction

Page

Nos.

1-20

21

22

CURRENT STATUS OF PUBLIC HEALTH

SYSTEM IN INDIA

3.

History

Federal Set-up

Union Ministry of Health & Family Welfare

Department of Health

Department of Family Welfare

Department of Indian System of Medicine and

Homoeopathy

'3.7' Function

3.8 Department of Health

3.9 Computerisation

3.10 Medical Education, Training and Research

3.11 International CO-operation for Health and Family

Welfare

3.12 Facilities for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled

Tribes under special component plan

3.13 Directorate General of Health Services

3.14 Functions of Department of Indian System of

Medicine and Homoeopathy

3.15 Department of Family Welfare

3.16' Planning Commission

3.17 State Level

3.18 District Level

3.19 Community Health Centre/Primary Health

Centre/Sub-Centre

3.20 Observations, Suggestions and Overview

3.21 State Level

3.22 District Level

3.23 Community Health Centres

3.24 PHC/Sub-centre Level

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

43

44

44

45

45

45

46

48

49

50

51

51

53

58

60

63

64

65

66

66

72

72

73

74

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM

INCLUDING INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT

SERVICES

4.

General Introduction

Notification System

Diseases that are notifiable

Legal Provisions for Notification

Reporting Agency

Defects in Notification

Epidemiological Units and Investigations

Public Health Laboratories

Isolation and treatment facilities

Quarantine Administration

Anti-Mosquito and anti-rodent measures at Ports

and Airports

4.12 Collection and dissemination of Statistics

4.13 Observations, Suggestions and Overviews

4.14 Institutional Supprt Services

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

4.5

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

4.10

4.11

76

77

78

78

79

79

81

81

82

82

83

83

96

99

STATUS OF CONTROL STRATEGIES FOR

EPIDEMIC DISEASES

5.

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

5.5

5.6

5.7

5.8

5.9

5.10

5.11

General Introduction

Malaria

Kala-azar

Japanese Encephalitis

Dengue

Diarrhoeal Diseases including Cholera

Poliomyelitis

Measles

Viral Hepatitis

Strategy for Control of Epidemic Diseases

Observations, Suggestions and Ovendews

103

105

109

110

111

112

113

114

114

114

116

EXISTING HEALTH SCHEME

6.

6.1

6.2

6.3

6.4

6.5

6.6

6.7

6.8

6.9

6.10

Rural Health Service Scheme

Health Manpower in Rural areas as on 31.03.95

Health Manpower in Tribal areas as on 31.03.95

Training of professionals and para-professionals

Village Health Guide Scheme

Mini Health Centre Scheme of Tamil Nadu

Rehbar-i-Sehat Scheme in J & K

Child Survival and Safe Motherhood Scheme

Universal Immunisation Programme

Suneillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases

ii

118

123

123

125

126

128

129

129

130

131

6.11

6.12

6.13

6.14

6.15

6.16

6.17

6.18

6.19

6.20

6.21

6.22

6.23

6.24

6.25

6.26

6.27

6.28

6.29

7.

Testing of Oral Poliovaccine

Oral Rehydration Therapy for Diarrhoea control

among children

Programme of Acute Respiratory' Infection

Iron Deficiency

Vitamin A Deficiency

Safe Motherhood Services for Pregnant Women

Care of Newborn and infants

National Malaria Eradication Programme

National Leprosy Eradication Programme

National Tuberculosis Control Programme

National Filaria Control Programme

National Guineaworm Eradication Programme

National AIDS Control Programme

National Kala-azar Control Programme

National Programme for Control of Blindness

National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control

Programme

National Diabetes Control Programme

National Cancer Control Programme

Observations, Suggestions and Overviews

135

135

136

136

137

139

144

145

146

147

148

150

150

152

154

155

157

NATIONAL FAMILY WELFARE PROGRAMME

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Family Welfare Programme During the First

Seven Five Year Plans

7.3 Observations, Suggestions and Overviews

8.

131

133

161

161

177

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND SANITATION

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Constitutional Obligations for Environmental

Health and Sanitation

Water

Supply

8.3

8.4 Sanitation

8.5 Hospital Waste Management

8.6 Drinking Water Quality- Surveillance - Legislation

and Standards

8.7 Operation and Maintenance

8.8 Industrial Waste Management and Air Pollution

Control

8.9 Air Pollution control in India

8.10 Observations, Suggestions and Overviews

in

183

185

186

187

191

191

192

192

195

198

EPIDEMIC REMEDIAL MEASURED - ROLE OF

STATE AND LOCAL HEALTH AUTHORITIES

9.

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

9.5

9.6

9.7

Introduction

State Health Directorates

Municipal Health Authorities

District Health Authorities

Primary Health Centre Infrastructure

Panchayati Raj System

Observations, Suggestions and Overviews

201

201

202

203

203

204

204

CURRENT STATUS OF HEALTH

MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEM AND

ITS ROLE

10.

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Evolution of HMIS in India & its current Status

10.3 Current Status of HMIS implementation in

10.4

various states

Observations

206

206

211

211

REC COMMENDATION S

11.

11.1 Short Term

11.1.1 Policy Initiatives

11.1.2 Administrative Restructuring

11.1.3 Health Manpower Planning

11.1.4 Opening of Regional Schools of Public Health

11.1.5 Strenthening & Upgradation of the Departments

of Preventive and Social Medicine in Idetified

11.1.6

11.1.7

11.1.8

11.1.9

11.1.10

11.1.11

11.1.12

11.1.13

11.1.14

11.1.15

11.1.16

11.1.17

11.1.18

Medical Colleges

Reorganised functioning of the Department of

PSM in Medical Colleges

Establishment of a Centre for Diseases Control

Primary' Health Care Infrastructure in Urban

Areas

State Level

District Level

Establishment of a supervisory’ mechanism at.

Sub-district level

Community- Health Centres

PHC/sub-centre level

Village level

Prevention of Epidemics

Upgradation of Infectious Diseases Hospitals

Water Quality Monitoring

Urban Solid Waste

iv

213

213

216

216

217

217

218

218

218

219

219

219

220

220

221

221

224

224

224

v

11.1.19

11.1.20

11.1.21

11.1.22

1 1.1.23

I 1.2

11.2.1

1 1.3

Inter-sectoral co-operation

Nutrition

Decentralised uniform funding pattern

Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs)

Involvement of ISM & Homoeopathy

Long Term

Broad set-up of Ministry'

Funding

o

225

225

226

226

227

227

227

228

12.

ACTION PLAN FOR STRENGTHENING OF

PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM

229

13.

ACKNOWLDGEMENT

23S

14.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

239

15.

ANNEXURES

i-lii

v

Cor^i H LhC|.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

E-1.0 INTRODUCTION

India is a large country with around 900 million population in 25 states

ami 7 Union Territories. I listoricallv Irmlia had a rich public heath system as

evidenced from the relics of Indus Valley civilisation demonstrating a holistic

approach towards care of human and disease. I he public health system

declined through the successive invasions through the centuries, intrusion of

modern culture and growing contamination of soil, air and water from

population growth. With the establishment of British rule and the initiation

of practice of Western medicines in India strong traditional holistic public

health practice in India went into disuse bringing disease-doctor-drug

orientation. The so-called modern public health practice of the advanced

European and industrialised countries was primarily set up around

cantonments, district and State Headquarters in British India.

E-l.l Bv the time India achieved independence socio-political and economic

degradation reached to an extent where hunger and mal-nutrition were

almost universal; 50% of the children died before the age of five, primary

health care was very rudimentary or non existent and the state of public

health was utterly poor as evidenced through life expectancy at birth around

26, infant mortality rate 162, crude death rate around 22, maternal mortality

rate around 20. Only 4.5% of the total population had access to safe water

and onlv 2% of the people had sewerage facility. Number of medical

institutions were few and trained para professionals like nurses, midwives,

sanitary inspectors were barely skeletal in numbers. The picture on the

nutrition front was very grave. Food production, its distribution and

availability of food per capita were all unsatisfactory. MCH services, school

health services, health care facilities for the industrial workers, environmental

health were all far from satisfactory.

V

E-1.2 Under the Constitution, health is a slate subject and each state has its

health care delivery system. The federal government's responsibility consists

of policy making, planning, guiding, assisting, evaluating and co-ordinating

the work of various provincial health authorities and also supporting various

on-voing schemes through several funding mechanisms. By and large heall r

care delivery system in India in different states has developed following

independence on the lines of suggestions of the Bhore Committee which

recommended delivery of comprehensive health care at the door step of the

population through the infrastructure of primary health centres and sub

centres. During the last eight 5 year plans following independence a large

network of primary health care infrastructure covering the entire country ras

been established. In addition, several national health and disease contio

programmes were initiated to cover a wide range of communicable diseases

namely, malaria, filaria, tuberculosis, several vaccine preventable diseases Ime

diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles etc. and to also cover some

important non-communicable diseases like iodine deficiency cnsort ers,

1

PHSl'ind! j\)C

conlio’ of biinciness, cancer, diabetes etc. The progress was periodically

rcvic’.ved through con.stitution of several committees like Mudaliar

Committee, School Health Committee, Chadha Committee, Mukherjee

Committee etc.

To provide more thrust on Hie improvement of

environmental health and sanitation the responsibilities pertaining to water

supply, s-nutation and enviroiimcntal related issues were tran.sferrcd to the

concerned ministries of Urban Development, Phiral Development and

Environment and Forests.

Major initiatives were taken up in our efforts to

reach Health for /ch by 2001) A.D. on the lines of policv directives enunciated

in National Health Policy. Eighth plan starting in 1992-93 clearly emphasised

that the health facilities must reach trie entire population by the end of Sth

plan and that tire health for all paradigm must not only take into account the

high risk vulnerable group i.e. mothers and children but also focus on the

under privileged segments both within and outside the vulnerable group. All

tiie efforts put through the last four and a half decades following

independence made significant dent in the improvement of health indices

viz. IMR 74 (1994), water suppiv urban area 54.9%, rural area 79.2% (1993),

sanitation urban area 47.9% (1993), rural 14% (1994), crude death rate 9.2%

(1994). expectation of life at birth Male 60.4% (1992-93) and fernale 61.2%

(1992-93). Significant number of doctors and para medical staff are available

and the food productions have been raised from 50 million tonnes in 1950 to

1S2 million tonnes in 1993-91 increasing the per capita availability even in

spite of large population growth from 394.9 gm in 1951 to 474.2 gm in 1994.

E-1.3 In spite of this significant development and impressive growth in

health care, enormous health problems still remain to be tackled and

addressed to.

Though mortality has .declined appreciably yet survival

standards are comparable to the poorest of the nations of the world. Even

within the country wide differences exist in the health status in the states like

Bihar, Orissa, Madhva Pradesh, Rajasthan to that of Karnataka,- Maharashtra

and Punjab which have done exceedingly well in terms of quality of human

life. Major problems facing the health sectors are, lack of resources, lack of

multi-sectoral approach, inadequate 1EC support, poor involvement of NGOs,

unsatisfactory laboratory support services, poor quality of disease

surveillance and health management information system, inadequate

institutional support and poor flexibility in disease control strategy etc.

E-1.4 In the background of the above and also in the light of the observations

in recent times following review of the rural health services, national

programmes like malaria, tuberculosis, UIP etc. concern has been expressed

that whether our efforts will succeed in achieving the goal tor reaching

Health for. All by 2000 A.D. In fact experts are of the opinion that Health tor

All bv 2000 A.D. is not a distinct possibility. It may have to be revised

backwards by a decade or two. The concern has been further compounded

follo’A’ing the recent outbreaks of malaria and plague indicating poor

o

response^ capability of the existing public health system in meeting the

caoabilitv

emergent challenges of the modern days particularly die threat posed by ne^,

A

J

o

phsi'uinl tio<*

emerging and re-emerging human pathogens.

In this context, the

Government of India constituted an expert committee to comprehensively

review the public health system in the country under the chairmanship of

Prof. J.S. Bajaj, Member, Planning Commission to undertake a comprehensive

review of (a) public health system in general and the quality of epidemic

surveillance and control strategy in particular, (b) the effectiveness of the

existing health scheme, institutional arrangements, role of states and local

authorkies in improving public health system, (c) the status of primary health

infrastructure, sub centres and primary health centres in rural areas specially

their role in providing intelligence and alerting system to respond to the

science of outbreaks of disease and effectiveness of district level

administration for timely remedial action and (d) the existing health

management information system and its capability to provide up-to-date

intelligence for effective surveillance, prevention and remedial action. I he

committee had four meetings in addition to interaction between the members

of the expert committee.

The summary of the observations and

recommendations suggested by the committee are summarised here.

E-2.0 PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM IN INDIA

E-2.1 Federal Set up

The federal set up of public health system consists of Ministry of

Health & Family Welfare, the Directorate General of Health Services with a

network of subordinate offices & attached institutions and the Central

Council of Health & Family Welfare. The Union Ministry of Health & Family

Welfare is headed by a cabinet minister who is assisted by a Minister of State

It has three departments namely, Department of Health, Department o

Family Welfare and Department of Indian Systems of Medicines. The

Department of Health deals with the medical and public hea th matters

■ including drug control and prevention of food adulteration throug i

e

Directorate General of Health Services and its supporting offices. Director

General of Health Services renders technical advice on all medical and pu ic

health matters and monitors various health schemes. Director General of

Health Services also renders technical advice on family welfare programmes.

The functions of the Union Ministry of Health and Family Wellare are to cany

out activities to fulfil the obligations set out in the 7th Schedule of the Article

246 of the Constitution of India under Union and Concurrent hs .

The federal government has set up several regulatory bodies for

monitoring the standards of medical education, promoting training and

research activities namely, Medical Council of India, Indian Nursing Council

Pharmaceutical Council etc. In addition to the Union Ministry of Health &

Family Welfare, Planning Commission has a Member (Health) o the rank of a

Minister of State who assists the Ministry of Health in formulation of plan

through advice and guidance and the expert guidance is also available for

monitoring and evaluation of the plan projects and schemes.

3

phstinal.doc

E - 2.2 S t a I c 1 c v c 1

i iic Stale governments have full authority and rcsponsibililv for ail the

Health services if' their territory. The State Ministry of Health & Famiiv

Wehaie H headed by a Minister of Health C Family Welfare either of a