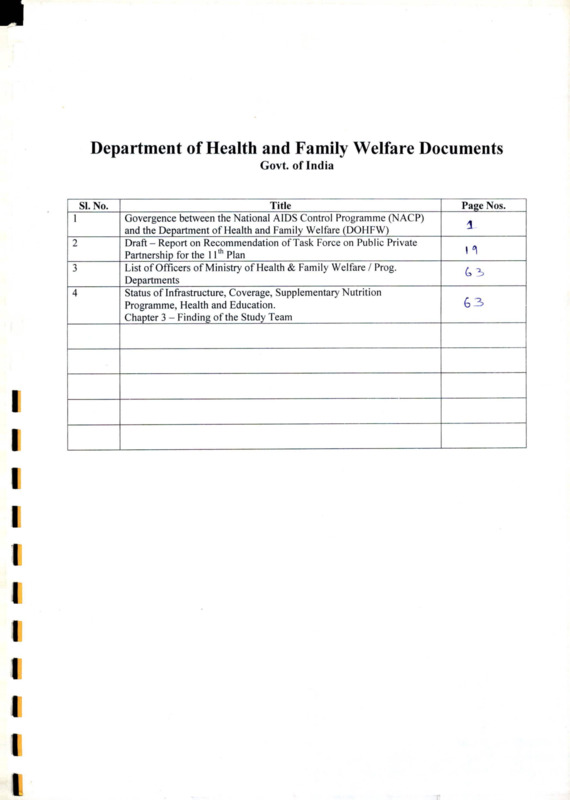

Department of Health and Family Welfare Documents

Item

- Title

- Department of Health and Family Welfare Documents

- extracted text

-

Department of Health and Family Welfare Documents

Govt of India

SI. No.

1

2

3

4

I

1

I

I

_________________________ Title_______________________

Govergence between the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP)

and the Department of Health and Family Welfare (DQHFW)______

Draft - Report on Recommendation of Task Force on Public Private

Partnership for the 11th Plan_______________________________

List of Officers of Ministry of Health & Family Welfare / Prog.

Departments___________________________________________

Status of Infrastructure, Coverage, Supplementary Nutrition

Programme, Health and Education.

Chapter 3 - Finding of the Study Team

Page Nos.

3

I °\

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 1 of 17

CONVERGENCE BETWEEN THE NATIONAL AIDS CONTROL PROGRAMME (NACP)

AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE (DOHFW)

1.

INTRODUCTION

1.1 The HIV/AIDS epidemic in India is complex, with intense focal epidemics among sub groups

(IDUs, Sex workers, Truckers, Men who have sex with Men) in some states, situations where

prevalence is over 1% in the general population, and low prevalence in some others states. In states

like Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Manipur, and Nagaland, prevalence

among antenatal women (based on sentinel surveillance data (2003) located in ANC clinics),

considered representative of the general population, is around 1.25%. Annexure 1 provides state

wise HIV prevalence levels from 455 sentinel surveillance sites, for the year 2003. NACO has

classified states as high prevalent, medium prevalent, highly vulnerable and vulnerable states

(Annexure 2). The index of vulnerability is based on extent of migration, size of population, and

poor health infrastructure. Among highly vulnerable states are: Bihar, Rajasthan, MP, UP,

Uttaranchal, Chhatisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa, and Assam. This includes all the EAG states of the

DHFW.

1.2 There is a pressing need to scale up prevention strategies based on factors of risk, vulnerability, and

impact, expand delivery of interventions and ensure that populations at risk and vulnerable groups

are reached. India is at a stage in the epidemic where all sexually active individuals must be offered

information and services on preventive interventions. Sexually active youth, particularly girls are at

high risk given the paucity of needs specific information and services. HIV/AIDS infection

prevalence is increasingly acquiring gender connotations. Sentinel surveillance data also show that

women account for more than half of all infections in rural areas (nearly 60%) and about two fifths

of all infections in urban areas. Sentinel surveillance sites are located mainly in either Antenatal

clinics or in STD clinics. Given the evidence that most STD clinic attendees are men, it can be

assumed that most women who are positive are also pregnant, a rather ominous portent for risk of

transmission to newborns, and a substantial justification to expand the number of sites offering

PPTCT.

1.3 Convergence between the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) with over a decade of

experience and technical competence in HIV/AIDS prevention and care interventions and the Health

and Family Welfare programmes (HFW) with its infrastructure, human resources and capacity

reach to every village and community is critical to ensure scaling up and effective service delivery.

1.4 Behavior Change, prevention/management of RTI/STI and condom promotion are the cornerstones

of HIV/AIDS prevention. All three areas have a significant degree of overlap with interventions in

the Reproductive and Child Health programme, since target groups and services fall in the same

arena. Other areas of prevention linked to HIV/AIDS interventions and which have implications for

services in the HFW are Voluntary Counseling and Testing, (VCTC), Prevention of Parent to Child

Transmission (PPTCT), and ensuring safety of blood and blood products. Comprehensive

HIV/AIDS Programmes include components of both prevention and care. VCTC and PPTCT are

two areas of overlap between prevention and care strategies. Areas of cross cutting importance that

need to be addressed in prevention and care strategies include: gender, private sector involvement,

and reduction of stigma and discrimination among health care providers and communities.

(Figure 1)

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

I

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 2 of 17

Prevention Strategies

Behaviour Change

RTI/STI management

Condom Promotion

Blood Safety

Harm Reduction

VCTC

PPTCT

Stigma

ovc

Care Strategies

Clinical Mgmt.-OI,

ARV

Home/Community

Care- nutrition

asepsis, psychosocial.

Referral Networks

strengthening,

Legal Support

2, CONVERGENT TECHNICAL STRATEGIES AND PROGRAMMATIC INTERVENTIONS

OF NACO AND HIAV

2 1 The National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) is the implementing agency for the NACP. At

the state level, State AIDS Control Societies (SACS) implement HIV/AIDS interventions.

Currently NACO and the SACS support about 900 NGOs for targeted interventions aimed at

reaching the so-called high-risk groups, (those with high numbers of sexual encounters increasing

possibility of transmission, such as Sex Workers, Truckers, Men who have sex with Men,

Intravenous Drug Users, Adolescents, Migrant men and women,). They also support behaviour

change communication aimed at the general population through variety of mechanisms. The reach of

the NACP to men and in urban areas is significant.

2 2 In the public sector, NACO and the SACS support RTI/STI management, VCTC, PPTCT, Blood

Safety, and several other interventions. However the reach of these interventions through the health

system is primarily through teaching hospitals and medical colleges, district hospitals and in the case

of the six high prevalence states, taluk hospitals as well. The SACS in the high prevalence states

(most of which are the ones with better health infrastructure and moderate to high care seeking) are

also active in implementing HIV/AIDS interventions.

2 3 The Department of Health and Family Welfare at National and State levels (with state specific

variations) supports a range of services for improving primary (including reproductive) health care at

community primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Community based interventions are pnmarily

provided by the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife located at the sub center. The coverage of the sub centre

is about 5000 (3000 in tribal areas) and covers about the area of three to four gram panchayats.

Service delivery is through the sub center on fixed days, supplemented by outreach visits to the

coverage area. At the village level, the Anganwadi Worker (AWW) and/or the Traditional Birth

Attendant (TBA) often assist the ANM. With the advent of the National Rural Health Mission it is

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 3 of 17

expected that the ANM will soon be supported by a female community health volunteer (ASHA), and

assisted by the AWW and TEA. Thus the potential reach of the system will be to every community

and habitation. In addition to the public sector health system, the DHFW supports NGOs (through

the Mother NGO scheme) to implement a range of RH interventions (Safe motherhood, family

planning, adolescent health, RTI/STI management, child health, and male involvement) in areas

underserved or not served by the public sector system. While the DHFW through its flagship RCH

project does include enhancing male responsibility as a key intervention, the emphasis is on women

and children. Urban health is a component of the RCH 2 programme.

2.4 The following areas of convergence have been identified

for scaling up HIV/AIDS prevention

responses: RTI/STI management, Condom Promotion, Voluntary Counseling and Testing,

Prevention of Parent to Child Transmission, Behaviour Change Communication, Blood Safety,

Training, and Management Information Systems. In addition male involvement and ensuring

convergence of NACP and DHFW through strengthening urban health infrastructure and reach are

two additional strategies, which are common to the major areas identified above.

2.5 This paper provides a broad framework for action to address the major convergence areas. The

effectiveness of convergence of key interventions is dependent on several factors, but critical is the

operationalization of convergence within well functioning health systems and programme

management structures at all levels. RCH II has been designed to address reproductive and child

health interventions through a framework of health sector reforms at various levels. It is opportune

that NACO and DHFW jointly look for ways to improve reach, enhance access and coverage,

provide quality services, address synergistic intervention elements, and prioritize interventions

based on prevalence, infrastructure, current programme efficacy, and resources. It must be

emphasized that this framework is proposed at the National level and state level consultations with

key stakeholders are necessary to operationalize the plan in the context of state realities.

2.6 Section 3 provides substantive details on each convergence area, with a brief technical background

for each area, highlights current interventions of NACO and DHFW, identifies points of

convergence in order to reach groups and communities that are at risk and vulnerable, and defines

broad areas for operationalizing these strategies. Section 4 includes operationalization of

convergence and details institutional mechanisms to facilitate convergence. Section 4 is

supplemented by a matrix, which summarizes key convergence areas, primary responsibility, and

convergence aspects. Section 5 briefly discusses next steps.

3. OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES FOR CONVERGENCE

3.1

RTI/STIprevention and management

3.1.1

Background: RTI/STI has a severe impact on the reproductive health of individuals as well

as significantly enhances the risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV/AIDS. Women are

biologically more vulnerable to acquiring RTI/STI and consequences of STI in women are

more serious (ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, still births). Unequal gender

relations resulting in sexual coercion is more pronounced among women, and women often

have limited access to care. There is evidence that RTI/STI care is more often sought in the

private sector than in the public sector and in several places from untrained practitioners as

well as chemists. There is little published comparable and reliable data on RTI/STI in the

country. Efforts at programme planning have been based on micro studies conducted with

different methodologies, using varying criteria and for clinical and laboratory diagnosis.

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

3

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 4 of 17

3.1.2

DHFW strategies: The National STD control programme has been in place since 1946.

However, it was only in the RCH 1 programme, that RTI/STI management was includedion

a national scale. Many donor-funded programmes in states have also supported Rll/S

services through state health and family welfare programmes. While there are no formal

evaluations to assess the performance effectiveness of these efforts, anecdotal evidence

suggests that several lacuna hampered these efforts and they remained largely out of the

reach of women and men in need of services. Current policy guidelines stipulate that only

medical officers are allowed to prescribe RTI/STI drugs, thus limiting the reach of effective

RTI/STI services.

3.1.3 NACP strategies-. RTI/STI management has been attempted through several approaches:

a. NGOs working with High Risk Groups on targeted interventions are provided with support for

medical personnel, clinics, and Drugs for RTI/STI. In some instances NGOs collaborate with the

public health system or private providers to provide STI diagnostic and treatment services.

b. Annual Family Health Awareness Campaigns are held across the country. These are two week

campaigns which are period of heightened activity at the district level and below when the

machinery of the HFW system is expected to conducts house to house and group education, media

and advocacy events and promote care seeking for RTI/STI. Patients are referred to PHC and

above, where RTI/STI are treated using the syndromic approach. Annexure 3 provides details of

the achievements of FHAC from 1999 to 2003. Coverage increased from 100 districts to 572

districts.

.

.

c. NACO has provided support to establishing STD clinics at hospitals upto and including district

hospitals. By the end of fiscal 2004, NACO had supported 735 STD clinics in all medical

colleges and in most district hospitals. Each STD clinic includes a qualified STD specialist and

laboratory support for diagnosis and treatment of STI. NACO also ensures a continuous supply of

STI drugs. (Annexure 4 provides details of number of STD clinics in each state)

NACO

supported training of a range of HFW providers (MO, ANM, LHV, Laboratory

d.

technicians) in areas such as RTI/STI, universal precautions, nature and content of HIV/AIDS

programming, stigma and discrimination. Annexure 5 provides details of personnel trained.

3.1.4

Core Convergence Recommendations for RTI/STI:

From the above data it is clear that NACP interventions in the public sector system reach only the

district hospitals and are not programmed to be gender sensitive. Although Medical officers have been

trained in syndromic diagnosis, they are located in primary health centers and above. Current utilization

of PHCs is low. Thus the benefit of the knowledge and skills of the medical officers does not reach

communities in many parts of the country. The FHAC could do a good job of spreading awareness but

services are still provided at the district level, reducing reach. DFW interventions are also primarily

through medical officers. Grass roots workers such as the ANM in most areas are not empowered to

provide information and services for RTI/STI. There is little by way of health education at the

community level on RTI/STI, which highlights issues of risk and vulnerability, male responsibility, and

the use of condoms for dual protection. This varies from state to state and in high prevalence states,

awareness levels are high, but access to services remains low. One of the challenges that needs to be

taken into account while converging the programme into the DHFW programme is that the reach to

important core and bridge groups such as: “sex workers, men who have sex with men, men in the

general population, and youth. RCH II does include interventions to address youth, enhance male

responsibility, and health in urban areas and care must be taken to ensure that convergence mechanisms

address the inclusion of such groups.

a. Public Sector interventions from district to peripheral level for RTI/STI to be implemented

through DHFW, in line with the RCH II design document. RTI/STI prevention, management of

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 5 of 17

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

3.1

the client, partner notification, treatment, and follow-up are the key components of an RTI/STI

programme. Comprehensive RT/STI treatment will be provided at CHC and 24 hour PHC

(clinical and etiologic) and first line drugs at the PHCs.

RTI/STI control among High Risk Groups through NGOs with funding support for RTI/STI

diagnosis and treatment, to continue through NACO and SACS, but reporting also to HFW.

It is expected that ASHA will be provided with enough information/supplies to support health

education, prevention advice and treatment facilitation (through referral) at the village level.

Presently the closest possible site for services by trained personnel is the sub center level. The

ANM/Male MPW will be the frontline service providers for RTI/STI management, MO/SN/LHV

at the PHC level, and MO/Ob-Gyn. at the CHC/FRU level. It is expected that over time, with

strengthened Primary Health Care, laboratory based management of RTI/STI will be the norm

rather than the syndromic approach. At the CHC level, basic screening tests for RTI/STI will be

made available. At the district level, RTI/STI will be managed by STD specialists supported by or

linked through referral to high quality laboratory services supporting the full complement of

laboratory tests for RTI/STI.

At the community health centers and district hospitals, RTI/STI management has to be included in

protocols in Ob/Gyn and Medicine departments. Medical and paramedical professionals to be

oriented to risk identification and referral to VCTC.

NGOs under HFW to include RTI/STI in their package of interventions, with referral or services

as appropriate.

Private providers (reached through Indian Medial Association (IMA) and Federation of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology-FOGSI ) to be part of RTI/STI management strategy for training and to ensure

appropriate reporting and notification, particularly in the case of sexually transmitted infections

and drug resistance surveillance. This will also need to be implemented through DHFW.

Voluntary Counseling and Testing Centers (VCTC)

3.2.1

Background: Voluntary Counseling and Testing is now acknowledged as an efficacious and

pivotal strategy for prevention and care for HIV/AIDS. Counseling is an important skill and is a

necessary part of interventions for several areas within Family Welfare, family planning, safe

motherhood, RTI/STI, and in dealing with youth. It is also more cost effective to integrate VCT

into sexual and reproductive health services, rather than support them as freestanding sites.

Counseling requires specialized skills and attitudes, space to assure confidentiality, laboratory

services for testing, adequate reporting systems.

3.2.2

DHFW strategies: While counseling is an important element of several reproductive health

services, counselors are not part of the health provider cadre. ANM, LHV and other providers

have been trained in basic motivation, interpersonal skills, but these are not dealt with in any

depth, nor are they geared toward attitudinal change. It has thus far formed part of an integrated

training package. In some states donors have supported separate training to improve counseling

and motivation skills of ANM and LHV (UNFPA through IPD projects, USAID in SIFPSA), but

only in selected districts.

3.2.3

NACP strategies: NACO and the SACS have established 650 VCTCs across the country with

about half of them located in high and medium prevalence states. They are primarily located in

medical colleges and district hospitals. Annexure 6 provides state wise details of numbers of

VCTC. Each VCT includes one male and one female counselor, and one laboratory technician.

NACO and SACS supply testing kits for these VCTCs. In the medical colleges, the VCTC are

located within the microbiology departments (with counselors reporting to the HOD,

Microbiology) and in charge of the Pathologist in a district hospital. Currently the view of the

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 6 of 17

State AIDS Control Societies is that VCTC utilization is low, particularly in the low prevalence states.

3,2.4

Core Convergence Recommendations for VCTC

The NACP will manage the VCTC in collaboration with the key staff of the facility in which

the VCTC is located. Youth information centers to be established with the VCTC to increase

access of young people to information and referral for services for a range of reproductive

and sexual health issues.

b. NACP will support the staff of VCTC and supplies required with DHFW will provide the

physical infrastructure.

c. It is proposed that the district VCTC function as a satellite center to coordinate, support and

supervise operations of the VCTC’s located in the CHC and 24 hour PHC. This internal

coordination is important for several reasons- to maintain quality of services at all sites, to

ensure uninterrupted supplies, link with PPTCT at district and CHC levels, and to enable

referral linkages of clients that test positive to appropriate centers.

d. VCTC’s will not function as sites for counseling of HIVAIDS alone. Counselors in VCTC,

particularly at secondary and primary health care levels should be able to counsel for family

planning, RTI/STI prevention, safe delivery, and male responsibility. A cadre of counselors

could be established who would serve the RH needs of women and men, including

HIV/AIDS, and the RH information and service for young people. It is hoped that this

measure will increase utilization of VCTC.

e. Expand the number of VCTC sites. The expansion should be informed by a rapid

assessment of VCTCs in low and high prevalence areas, and identify systems issues, human

resource training gaps, and logistics. The expansion is proposed in a phased manner, and

will be governed by the following: prevalence, physical infrastructure, human

resources, and community use of facilities. Fortunately the high prevalence states also

have better infrastructure and increased utilization (higher rates of antenatal coverage,

institutional deliveries, and overall increased care seeking behaviour). As a long-term plan,

(by 2012) it is expected that all PHCs will have VCTC facilities that will cover a range of

services beyond just HIV/AIDS counseling. The expansion process is proposed as follows:

Phase 1: (2005-2008) In the high prevalence states, district hospitals, all CHCs and all 24

hour PHCs will have Voluntary Counseling and Testing Centers, staffed by a full

complement of male and female counselors; separate space and laboratory back up. In

the low prevalence centers, VCTC could be located at the district level and at all CHCs.

In high prevalence districts within low prevalence states, the choice of whether 24 hour

PHCs could offer VCTC could be left to the state.

Phase 2: (2008-2010) All PHCs in high prevalence states and 24 hour PHCs in other

states will have VCTC.

Phase 3: (by 2012): PHCs, all CHCs and district hospitals, will offer VCTC services.

Expansion will be based on review of past experience, utilization and need.

f. Basics of Counseling for all cadres of staff (sub center to CHC) to be included in training

package, so that at the very minimum all staff have the skills to enable clients to understand

risk perception, motivate them to seek services, and finally be able to facilitate informed

referral.

g- Involvement of private providers and private laboratories, through IMA, FOGSI, and

pathologists Association, where testing takes place to ensure that their clients also are

counseled and their data is reported at district and state levels.

h. NGOs under HFW programme and NGOs working with High Risk Groups to include

information on VCTC functions and sites so that they can carry the message to the

community, and increase utilization as appropriate.

a.

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 7 of 17

3.3 Prevention ofParent to Child Transmission (PPTCT)

3.3.1

Background: Core PPTCT interventions need action in the community, and depending on the

package of services offered, at the levels of the sub center, Primary Health Center and at the

Community Health Center. PPTCT interventions for HIV positive women relate to a range of

services provided in the HFW system: antenatal, delivery, and postpartum care, abortion

services, VCTC, Management of STIs in pregnancy, Antiretroviral therapy based on current

policies- (currently Nevirapine), Family planning counseling and easy access to services,

Expansion of well baby clinics, high quality education and information provision on nutrition,

breastfeeding, RTI/STI, and HIV/AIDS, male involvement in MCH care, and linkages to

community based care and support programs for HIV/AIDS.

3.3.2

DHFW Strategies: DHFW per se does not implement PPTCT interventions. Currently PPTCT

interventions are being provided in selected locations through the health facilities of HFW.

However, training, supplies and logistics, and drugs are primarily supplied through NACO.

3.3.3

NACP strategies: Currently NACO is providing PPTCT services in 273 units across the country

of which 234 are located in high prevalence states. Annexure 7 provides details of PPTCT in the

country presently. They are primarily located at the medical colleges of high and low prevalence

states and at district hospitals only in the high prevalence states. They are located in the Ob/Gyn

department. A counselor, mostly female and one laboratory technician staff each PPTCT. Staff

of PPTCT sites (PPTCT team- Ob/Gyn, Microbiologist, Paediatrican, Staff nurse, and one health

educator) are trained for five days. Counselors of PPTCT are trained for a ten-day period.

Sensitization training of other staff in the facility where the PPTCT site is located is also

conducted.

3.3.4

Core Convergence Recommendations for PPTCT

a. The management of PPTCT sites should continue to be with the NACP, since all clients of the

PPTCT will need to be followed up for care and support. At the institution level, the PPTCT staff

will continue to report to the Head of Ob/Gyn. PPTCT at the district level will function as the hub

or satellite center to coordinate quality, supplies, reporting and facilitation of referral.

b. NACP will fund the counselor and laboratory technician in the PTCT and the supplies required for

the PPTCT programme. The PPTCT will be located in the Ob/Gyn department of the CHC and

will function through existing staff.

c. PPTCT sites should be expanded in a phased manner. Since PPTCT is a function of the obstetric

department, and since RCH II is focusing on improving/strengthening access and quality of

institutional deliveries, PPTCT can be implemented within the framework proposed for RCH II.

Phase 1 (2005-2008): All district hospitals and CHCs to offer PPTCT, regardless of prevalence.

Phase 2 (2008-2010) In high prevalence states, 24 hour PHCs, should also offer PPTCT.

Phase 3(by 2012 years): 24 hour PHCs in all states to offer PPTCT services, based on

prevalence, utilization, and need.

d. At the community level, ASHA/ANM will be trained through health education and motivation

among women and men for risk perception, risk identification, facilitation in accessing VCTC,

and thus identifying positive women in need of PPTCT. Para medical and medial providers at the

PHC level will also be trained in similar areas to facilitate referral to PPTCT and enable follow

up.

e. Positive women will be followed up through pregnancy by ANM/ASHA and encouraged to opt

for institutional delivery in district or CHC/FRU.

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 8 of 17

f. PPTCT programmes should establish linkages with the Integrated Management of Neonatal and

Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI) component of RCH II, to address issues of infant feeding, nutrition,

and infections.

g. All providers would need sensitization on issues of stigma and discrimination, so that positive

women do not fear institutional deliveries. PPTCT teams should be specially trained in areas of

infection prevention, and stigma and discrimination attitudes, as well as the specific technical

aspects of PPTCT

h. Institutions to be strengthened to adopt universal precaution measures and waste management.

Delivery kits to be made freely available under the PPTCT programme.

i. Orientation and sensitization of private providers (through IMA, FOGSI, Indian Health Care

federation, Hospital forums and associations) and involvement of private hospitals in VCTC and

PPTCT as appropriate.

j. NGOs supported by DHW and NGOs working with high-risk groups to be provided with

information on location of PPTCT sites and encouraged to facilitate referral and follow up.

3.4 Behavior Change Communication

3.4.1

3.4.2

3.4.3

3.4.4

Background: Changing individual and community behaviour is critical to HIV

prevention In order to impact the epidemic it is necessary to target behaviour change

interventions at the individual level to increase knowledge, enhance risk perception, and

develop safe sex skills. These are primarily through interpersonal communication and

small group discussions and peer education. Such efforts at the individual level need to

be reinforced by community level interventions to increase understanding of a supportive

environment to reduce risk and vulnerability, and influence societal norms. Messages

that are targeted to sexually active individuals include: postponing age of sexual activity,

using condoms correctly and consistently, decreasing number of sexual partners,

increasing STI and TB treatment seeking and prevention behaviors.

DHFW strategies: HFW has not integrated HIV/AIDS messages in BCC material till

date. However, in the past few months, efforts are on to integrate HIV/AIDS prevention

messages in some initiatives of the HFW department- wall calendar and diary for 2005 of

the MOHFW includes HIV/AIDS messages. Adolescent health education and life skills

programmes have included HIV/AIDS content quite substantially, especially in the

adolescent friendly health clinics, piloted by MOHFW.

NACP strategies: At the National level, NACO frames guidelines for IEC activities

countrywide and undertakes multimedia campaigns along with political and media

advocacy. NGOs working with high-risk groups for targeted interventions develop their

own BCC strategies. SACS in each state have mass media campaigns and other activities

for general population- varied across states and school AIDS Education programmes.

Core Convergence Recommendations for BCC

Create a mechanism to ensure that the leadership for developing BCC strategies and

programmes for DHFW and NACP is vested with one authority.

Joint (NACO, DFW) behaviour change communication strategy to be developed based on

commonality of target groups, and tailored for reach of general as well as high-risk

populations. This needs to take place at state level as well between State AIDS Control

Societies and State IEC bureaus.

3.5

Condom promotion

3.5.1

Background: Currently the male condom is the most widely available effective protection

•8

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and the ... Page 9 of 17

I

method against HIV and other STI. Condom distribution can be through free or social marketing

channels. They could be through community based distribution systems, depot holders, health

facilities, pharmacies, and village stores. For any scaled up prevention response it is important

to improve access and availability of condoms to all communities (rural and urban) and groups.

3.5.2 DHFW Strategies: In the family welfare programme, male condoms are promoted as a method

of contraception. In order to improve the use of condoms as a contraceptive, several initiatives at

social marketing and distribution through government and NGOs are being undertaken. Thus

DFW is the repository of substantial experience in promoting condom use as well as condom

procumbent and distribution. However the use of condoms as a method of dual protection has

not been promoted so far. About 25% of the overall condoms procured are distributed as free

supplies with 75% being programmed though social marketing agencies. Of these 25 %, over

three quarters are channeled to NACO for distribution to HRG through NGOs.

3.5.3 NACO strategies: Currently NACO procures and supplies condoms to the NGOs working with

HRG. Primarily NACO and the SACS obtain their supplies through the DHFW. NGOs also

directly access social marketing agencies. NACO and SACS ensure hat there is adequate supply

of condoms in STD clinics, VCTC, and Ob/Gyn clinics. SM condoms are made available at

outlets situated near state highways and in areas where TI projects are underway. NGOs are

encouraged to use a mix of free and SM approaches.

3.5.4

Core Convergence Recommendations for Condom promotion

Create a mechanism to ensure that condom programming for NACP and DHFW is managed

within a single entity to provide leadership and direction. This integration will greatly facilitate

streamlining the condom promotion strategy between the FW and HIV/AIDS programmes.

Joint development of a strategy on condom procurement and distribution to meet the needs of

sexually active women and men as a contraceptive method, as a method of dual protection and to

meet the needs of high-risk groups.

Condom supplies for NGO s involved in TI to be through NACO and SACS.

HFW to promote condoms as dual protection method through improved distribution channels.

Pilots to promote female condom use among general population as well sex workers both as a

contraceptive and barrier method.

3.6

Safety of blood and blood products

3.6.1

Background: In addition to ensuring blood safety, other strategies to reduce transmission

include: reducing the need for transfusions, educating and motivating low risk individuals to

donate blood.

DHFW strategy: Currently blood banks are located at state and at district levels. Stringent

guidelines for blood banks are in place. In the RCH II programme, DHFW has planned blood

storage centers at FRU level. However the procurement of blood will be primarily from the

blood banks certified by NACO, so quality control appears to be taken care of.

NACP Strategy: NACO has been involved in developing a blood safety policy and guidelines

for blood banks. Annexures 8 and 9 provide state wise details of blood banks supported and

strengthened by NACO respectively.

3.6.2

3.6.3

3.6.4

Core Convergence Recommendations fro Blood Safety

It is recommended that this policy be continued so that stringent quality controls are maintained at

the district levels, and high quality blood is available at secondary levels of care.

file ://C :\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr. .. 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t...

Page 10 of 17

Training

3.7

DHFW strategies: In RCH 1, Medical Officers, Staff Nurses, Lady Health Visitors and ANMs

were trained for periods of between 4 to 6 hours (depending on job profiles) in the area of

HIV/AIDS and RTI/STI. In RCH II, four core committees are currently reviewing the content of

training for each level of provider.

3.7.2 NACP strategies: NACO, SACS (and partner agencies- NGOs) have developed modules for

training in a range of areas- prevention, universal precautions care and support, PPTC 1 tor all

providers. These have been implemented separately from the HFW trainings.

3.7.1

3.7J

Core Convergence Recommendations for training

NACP to designate an officer to coordinate with the groups responsible for ongoing module

development for RCLIII and ensure that HIV/AIDS training inputs cover all areas of concern

adequately.

• Joint finalization of areas of training with respect to content, duration, mix of knowledge and

skills, for all cadres of health and community workers.

• NACO and DHFW to jointly develop a specific plan to train staff of PPTCT and VCTC to

ensure that these functions include other HFW elements as well.

. Finalized modules to be shared with private sector and NGO partners supported by HFW and

NACP.

•

3.8

Management Information Systems

3.8.1

DHFW strategies: As part of the RCH II programme a Management Information System is

being designed. An Integrated Disease Surveillance Project is also underway. Both these

systems will essentially capture data on an ongoing basis at all levels for programme

implementation and ongoing monitoring. Small and large scale surveys such as the NFHS and

District level HH surveys are also conducted periodically.

NACP strategies: The nationwide sentinel surveillance system captures data on an annual basis

from about 455 sites across the country. In addition, VCTC, blood banks and PPTC serve as a

reporting base. Programme supported NGOs also report on STI treated, condoms distributed and

coverage of high-risk groups.

3.8.2

3.8.3

Core Convergence Recommendations for Management Information Systems.

• Joint working group to review data needs, assess ongoing sources, and finalize requirements to fit

into RCH II MIS, so that all facilities report service performance on RTI/STI, VCTC and PPTCT

as part of routine reporting, while maintaining confidentiality.

. State and national level surveys (NFHS III, DLHS) designed to provide information on KAP

related to RTI/STI/HIV/AIDS

• Research and prevalence studies to assess nature of STIs to develop suitable management

protocols and assess antibiotic resistance patterns. Need to explore linkages with integrated

disease surveillance programme.

• Mechanisms to ensure periodic reporting on STI/HIV/AIDS by private providers

• Include NGO reports as part of district level reporting.

3.9

Male involvement: The case to promote male participation in improving reproductive and

sexual health for women has been articulated in several documents and is being implemented

IO

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t...

Page 11 of 17

through several community-based initiatives. However, the reach of programmes of the DHFW to men

is low. NACP on the other hand, (given that men are the predominant target group in the general

population) has significant experience in approaches to reach men, through condom promotion,

STI clinics, and mass media. In RCH II, it is proposed to provide gender sensitization training

for all providers. Specific BCC interventions will implemented to increase demand for male

contraceptive methods, male RH services, and to heighten awareness about men’s responsibility

in support of women’s sexual and reproductive health.

Core Convergence Recommendations to improve male involvement

• Ensure that NACP and DHFW training include male responsibility as a key area

• BCC strategies for both NACP and DHFW to address the area of male responsibility and shared

action for improved women’s RH as a major issue- includes partner notification, drug

compliance, safe sexual practices and condom promotion.

3.10

Strengthening urban health services to improve convergence: Urban health particularly among

the poor presents a special challenge to the DHFW. While overall health indicators in rural areas

may be better than in rural areas, they mask significant disparities. The reach of the poor to good

health care is limited, and they are often served by the private sector, poorly regulated and

offering care of questionable quality. Given the increase of slum populations, migrants, and

street children, and that these groups are identified as high risk groups for HIV/AIDS, it is

essential that their access to the services such as RTI/STI, VCTC, PPTCT. condom promotion

and BCC interventions be improved.

The NACP supports several targeted interventions in urban areas, primarily through NGOs, and

targeted at marginalized, high-risk groups, and not often general population based. NACP also

support STI clinics, VCTC and PPTCT in large medical colleges/teaching hospitals. However

primary and secondary health care facilities in urban areas are not as clearly structured or

organized as in rural areas. RCH II proposes a two-tier facility - an urban health center for a

population of 50,000- to address primary health care needs of the population, particularly the

vulnerable, and a second tier (mix of private and public sector) to serve as referral sites.

Core convergence Recommendations to improve reach of urban health

• Strengthening urban health infrastructure, including training of urban providers will have

benefits for urban RCH and NACP.

•

Involvement of urban private sector practitioners in training programmes, through

involvement of IMA and FOGSI. .

• Referral information on sites where RTI/STI, VCTC, and PPTCT are available to be

widely disseminated to both general and high risk populations through NGOs, private

sector, and IEC efforts.

• UHC and Referral sites to offer a range of RCH services without discrimination and in an

equitable manner to general populations and populations at risk.

4. OPERATIONALIZATION OF CONVERGENCE

4.1

Of the key areas identified for convergence, RTI/STI management for the general population

could be integrated within the DHFW. VCTCs and PPTC still need to be managed by

NACO and the SACS to retain focus and ensure referral linkages to care and support. In the

area of blood safety, it is recommended that NACO continue to ensure safe blood supplies at

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t... Page 12 of 17

district levels, and that blood storage units at secondary levels of care procure supplies from the

district. In the areas of behaviour change and condom procurement/distribution, it is

recommended that the leadership for the programmes be entrusted to one entity to ensure

overall guidance of both areas for Health, Family Welfare and the National AIDS Control

Programme. Male involvement needs to be woven into all components. Strategies to

improve services in rural areas must be replicated/adapted for urban areas. Joint working

groups are recommended at national and state level to ensure that the training plans and

monitoring and reporting systems of the DHFW and NACO (and corresponding groups at the

state levels) are well coordinated, reflect shared concerns and are synchronized at the

delivery levels.

4.2

Recommended Institutional Mechanisms

4.2.1

At the National level a NACP-HFW convergence committee is to be set up at DHFW to

provide policy inputs and oversight to the convergence between NACP and DHFW. The

Convergence Committee will be chaired by Secy, HFW and co-chaired by Project Director

NACO.

4.2.2

At the National level, two joint working groups are visualized comprised of technical and

programme mangers from NACO and DHFW. They include:

1. Joint working group on convergence of RTI/STI, VCTC and PPTCT into DHFW

infrastructure and services. (NACO/DDG/MH)

2. Joint working Group on Training and MIS. (NACO/DC Training, and CD, Statistics)

Broadly the roles of the JWG are to review quarterly performance from each state and jointly

review and prepare a report on performance coverage and quality. Reporting formats would be

developed in conjunction with existing formats or those proposed for larger programmes so that

programme managers at state and district levels are not burdened. It is expected that the NACPHFW Convergence Committee, which meets every quarter, will obtain reports from each of the

National JWG, provide feedback and serve as a problem solving mechanism.

4.2.3

It is recommended that at the state level, a similar mechanism be set up, so that the state and

central level review and monitoring, and information needs and flow are co-ordinated.

4.2.4

At the district level, NACO is considering the appointment of a convergence facilitator who

could ensure coordinated inputs between those programmes directly implemented by

NACO/SACS, between various NGO managed programmes, and finally between those

interventions that depend upon the DHFW resources for effective operationalization. In

addition this individual would follow up on the training plan for the district as well as the

MIS to ensure that there is convergence. This individual would report to the SACS and to

the CMO at the district level. At the district level, the District Health Mission (where all

other programmes of HFW are integrated), will include a sub- group to review HIV/AIDS

and HFW convergence in the major service areas (RTI/STI, VCTC, PPTCT) and NGO

functioning.

5.NEXT STEPS

As pointed out initially, this paper is only a broad framework for actions on convergence. The

framework needs to be validated at state level to ensure that there is ownership of the issues between the

State AIDS Control Societies and the Departments of Health ad Family Welfare. While RCH II is the

focus of convergence since it is due to be launched fairly soon, and there has been significant

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t... Page 13 of 17

decentralized planning and design, it is emphasized in this document. However there are several other

programmes and partners that also need to be viewed through the lens of convergence to ensure

appropriate and effective local responses to HIV/AIDS.

Role and

DHFW

Functions

of Role and

NACP

Functions

of Convergence

mechanisms/aspects

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

13

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t...

Page 14 of 17

14

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t...

Area

of

Convergence

-Primary

Responsibility- -Support to HRG-NGOs to

RTI/STI

integrate RTI/STI management continue, Service delivery

at all levels in public sector whether directly through

NGOs or referral to public or

system

-Increase

private

sector private sector.

involvement in high quality -Ensure that all STI service

RT/STI treatment- IMA and data and special studies are

provided to JCWG to enable

FOGSI

-Broadly RCH II strategies reporting at the Convergence

should be followed-At PHC committee level.

level, first line drugs to be

offered,

-District, CHC and FRU to

comprehensive

offer

etiological and lab based

treatment. At district level,

linkages with STD referral labs

to be strengthened.__________

-Infrastructure (space) to be Primary responsibility—

VCTC

increase VCTC sitesprovided in facilities where

expansion in phased manner

VCTC are located.

-Support to ensure referral -NACP support for staff and

supplies,

from other departments

Youth

Friendly

-Overall supervision by head -Include

of facility, in collaboration Information Centers at CHC

with Ob/Gyn, STD, Paed, and and PHC

other

-VCTC to serve

other depts.

-Frontline

providers

to counseling needs.

motivate community at risk for -Cadre/of counselors to staff

the sites.

VCTC

PPTCT

BCC

Page 15 of 17

-At National level,

NACP and DHFW to

set up a JCWG group

to monitor access of

RTI/STI services for

general population and

for HRG. Report to

HIV/AIDS

Convergence

Committee.

-Training of providers

(public, private and

NGO) and lab techs

within purview of

DHFW.

-DDG-MH/NACO

-JCWG

to review

functioning of VCTC

through periodic state

reports.

Report to

HIV/AIDS

Convergence

Committee

-Training of providers

of DHFW at all levels

to include elements of

risk

protection,

motivation for testingthrough DHFW

-NGO

training

facilitated by NACP,

but modules jointly

developed.

NACO/DDG-MH

-Overall supervision by head Primary Responsibility to -JCWG to obtain data

on

functioning

of

ensure functioning PPTCT

of facility

-Located

in

Ob/Gyn -Expand PPTCT sites in a PPTCT and review

performance

department, managed by HOD phased manner

for

all

-Ensure non discriminatory -NACP to support once -Training

counselor and lab. Tech. And providers to• include

practices

attitudinal as well

supplies for PPTCT.

-Ensure universal precautions

technical skills, and

-At the community level,

universal precautions.ANM/ASHA follow up of

DHFW

VCTC clients testing positive

-Private sector through

for ANC, and motivate for

IMA and FOGSIPPTCT

DHFW

NACO/DDG-MH

-All messages for HFW to -Messages for HIV/AIDS -BCC strategy/division

include HIV/AIDS prevention highlight appropriate service for NACP and DHFW

single

and care and support as provision through public and under

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

I

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t...

Condom

Promotion

Training

Reporting

Blood Safety

appropriate

-Ensure that NGO programmes

also use message content as

defined___________________

-Enhance condom use for dual

protection

-Female condoms to be

a

promoted

as

contraceptive/barrier method

Primary Responsibility for

training

of all

service

interventions

(except

VCTC/PPTCT) to be within

DHFW

-Support training content and

technical support for VCTC

and PPTCT training

private health system

-Ensure that NGOs highlight

service access in addition to

prevention messages._______

-Condom promotion key to

prevention

-Female condoms to be

a

promoted

as

contraceptive/barrier method

-Support training in terms of

content and technical support

-Primary responsibility for

training VCTC counselors in

a range of issues including

HIV/AIDS, which include

safe

motherhood,

family

planning

and

childcare.

PPTCT staff training also to

be

conducted

by

NACO/SACS.

Page 16 of 17

management.

Condom procurement

and distribution for

FW and NACO under

single entity.

-NACP to coordinate

with groups working

on RCH II modules to

ensure

HIV/AIDS

content for all workers.

-Joint Working Group

to be instituted to

review and ensure that

HIV/AIDS messages

and content for training

are tailored to each

level of provider

-Ensure that training

modules are shared

with NGO partners of

DHFW and NACP.

-Develop protocols and

guidelines for key

services-Ensure dissemination

of

protocols

and

guidelines to NGOs

and private sector.

DHFW MIS to capture service -Ensure that VCTC, PPTCT, -NACP to coordinate

data- RTI/STI, VCTC, and and sentinel surveillance data with RCH II MIS

convener

(CD,

is reflected in district MIS.

PPTCT

Statistics to ensure that

-MIS to include HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS indicators

indicators

are

included in MIS for

-Support sentinel surveillance

RCH

II.

data collection

-Joint Working Group

to review RCH II MIS

and

ensure

that

reporting of RTI/STI,

VCTC, and PPTC is

also included.

-Surveys (NFHS III

and DLHS )to include

information

on

HIV/AIDS as well.

Maintain quality of blood -Primary Responsibility to

taken from blood banks to assure safety of blood at

blood storage centers at banks at district level and

above

secondary levels of facilities.

IG

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr ... 9/3/2007

Areas of convergence between the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) and t... Page 17 of 17

NACO and the DFW jointly constituted a six member Task Force in late December, 2004 to identify areas of

convergence and develop an operational plan by January 31, 2005.

file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\Desktop\NRHM%20-%20for%20pr... 9/3/2007

1^-

DRAFT REPORT ON RECOMMENDATION OF TASK FORCE ON PUBLIC PRIVATE

PARTNERSHIP FOR THE 11™ PLAN

The Planning Commission constituted a Working Group on Public Private Partnership to

improve health care delivery for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan

(2007-2012) under the

Chairmanship of Secretary, Department of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India with the

following members:

1.

Secretary, Department of Health & Family Welfare, New Delhi

Chairman

2.

Secretary (Health), Government of West Bengal

Member

3.

Secretary (Health), Government of Bihar

Member

4.

Secretary (Health), Government of Jharkhand

Member

5.

Secretary (Health), Government of Karnataka

Member

6.

Secretary (Health), Government of Gujarat

Member

7.

Director General Health Services, Directorate General of Health Services,

Member

New Delhi

8.

President, Indian Medical Association, New Delhi

Member

9.

Medical Commissioner, employees State Insurance Corporation, New

Member

Delhi

10.

Dr. H. Sudarshan, President /Chairman, Task Force on Health & Family

Member

Welfare, Government of Karnataka, Bangalore

11.

Dr. Sharad Iyengar, Action Research & Training in Health, Udaipur,

Member

Rajasthan

12.

Executive Director, Population Foundation of India, New Delhi

13.

Dr. S.D. Gupta, Director, Indian Institute of Health Management Research,

Member

Member

Jaipur

14.

Ms. Vidya Das, Agragamee, Kashipur, District Rayagada, Orissa

Member

1

Dr. C.S. Pandav, Centre for Community Medicine, All India Institute of

15.

Member

Medical Sciences, New Delhi

Dr. V.K. Tiwari, Acting Head, Department of Planning & Evaluation,

16.

Member

National Institute of Health & Family Welfare, New Delhi.

17.

Dr. A Venkat Raman, Faculty of Management Sciences, University of

Member

Delhi

18.

19.

20.

21.

Dr. K.B. Singh, Technical Adviser, European Commission, New Delhi

Member

Shri K.M. Gupta, Director, Ministry of Finance, New Delhi

Member

Shri Rajeev Lochan, Director (Health), Planning Commission, New Delhi

Member

Joint Secretary, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, New Delhi

Member

Secretary

The Terms of reference of the Working Group were as under:

To review existing scenario of Public Private Partnership in health care (Public,

C)

Private, NGO) in urban and rural areas with a view to provide universal access to equitable,

affordable and quality health care which is accountable at the same time responsive to the needs

of the people, reduction of child and maternal deaths as well as population stablization and also

achieve goals set under the National Health Policy and the Millennium Development Goals.

(ii)

To identify the potential areas in the health care delivery system where an

effective, viable, outcome oriented public private partnership is possible.

(iii)

To suggest a practical and cost effective system of public private partnership to

improve health care delivery system so as to achieve the goals set in National Rural Health

Mission, National Health Policy and the Millennium Development Goals and makes quantitative

and qualitative difference in implementation of major health & family welfare programmes,

functioning of health & family welfare infrastructure and manpower in rural and urban areas.

(iv)

To deliberate and give recommendations on any other matter relevant to the topic.

2

DEFINING PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP IN HEALTH

Public-Private Partnership or PPP in the context of the health sector is an instrument for

improving the health of the population. PPP is to be seen in the context of viewing the whole

medical sector as a national asset with health promotion as goal of all health providers, private or

public. The Private and Non-profit sectors are also very much accountable to overall health

systems and services of the country. Therefore, synergies where all the stakeholders feel they

are part of the system and do everything possible to strengthen national policies and programmes

needs to be emphasized with a proactive role from the Government.

However for definitional purpose, “Public” would define Government or organizations

functioning under State budgets, “Private” would be the Profit/Non-profit/Voluntary sector and

“Partnership” would mean a collaborative effort and reciprocal relationship between two parties

with clear terms and conditions to achieve mutually understood and agreed upon objectives

following certain mechanisms.

PPP however would not mean privatization of the health sector. Partnership is not meant

to be a substitution for lesser provisioning of government resources nor an abdication of

Government responsibility but as a tool for augmenting the public health system.

THE ROLE OF THE PRIVATE SECTOR IN HEALTH CARE

Utilisation of Hospital Services

I

I

•I

I

i

8,000

7,000

6,000

5,000

■ Private

4,000

3,000

2,000

1,000

Source Pearson M, Impact and Expenditure Review, Part II Policy issues. DFID, 2002

Over the years the private health sector in India has grown markedly. Today the private

sector provides 58% of the hospitals, 29% of the beds in the hospitals and 81% of the doctors.

(The Report of the Task Force on Medical Education, MoHFW)

The private providers in treatment of illness are 78% in the rural areas and 81% in the

urban areas. The use of public health care is lowest in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The

reliance on the private sector is highest in Bihar. 77% of OPD cases in rural areas and 80% in

urban areas are being serviced by the private sector in the country. (60th round of the National

Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) Report.

3

"v

*

■ I

10i82

i(

X0'

.0^

)*

i

The success of health care in Tamil Nadu and Kerala is not only on account of the Public

Health System. The private sector has also provided useful contribution in improving health ca

provision.

Studies of the operations of successful field NGOs have shown that they have Produced

dramatic results through primary sector health care services at costs ranging from Rs. 21 to Rs.

91 per capita per year Though such pilot projects are not directly upscalable they demonstrate

promising possibilities of meeting the health needs of the citizens by focused thrust on primary

healthcare services. (NSSO 60th Round)

India: Percentage of Hospitalizations In The Public and Private

Sector Among Those Below The Poverty Line, According To State

100%

0)

□)

(U

4-»

c

0)

o

u.

CD

Q.

;J

__

80%

—,

60%

..

40%

20%

0%

/

/

// /

/

/

/

/

/

/

States

Public Facilities

Private Facilities i

Source Pearson M, Impact and Expenditure Review, Part II Policy issues. DFID,2002

While data and information is still being collated, the private health sector seems to be the

most unregulated sector in India. The quantum of health services the private sector provides is

large but is of poor and uneven quality. Services, particularly in the private sector have shown a

trend towards high cost, high tech procedures and regimens. Another relevant aspect borne out

by several field studies is that private health services are significantly more expensive than public

health services - in a series of studies, outpatient services have been found to be 20-54 /o higher

and inpatient services 107-740% higher. (Report of the Task Force on Medical Education,

MoHFW.

Widely perceived to be inequitable, expensive, over indulgent in clinical procedures, and

without standards of quality, the private sector is also seen to be easily accessible, better

managed and more efficient than its public counterpart.

4

Given the overwhelming presence of private sector in health, there is a need to regulate and

involve the private sector in an appropriate public-private mix for providing comprehensive and

universal primary health care to all. However there is an overwhelming need for action on

privatization of health services, so that the health care does not become a commodity for buying

and selling in the market but remains a public good, which is so very important for India where

1/3 of the population can hardly access amenities of life, leave alone health care.

In view of the non-availability of quality care at a reasonable cost from the private sector,

the upscaling of non-profit sector in health care both Primary, Secondary and Tertiary care,

particularly with the growing problems of chronic diseases and diseases like HIV/AIDS, needs

long term care and support.

OBJECTIVES OF PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

Universal coverage and equity for primary health care should be the main objective of any

PPP mechanism besides:

> Improving quality, accessibility, availability, acceptability and efficiency

> Exchange of skills and expertise between the public and private sector

> Mobilization of additional resources.

> Improve the efficiency in allocation of resources and additional resource generation

> Strengthening the existing health system by improving the management of health within

the government infrastructure

> Widening the range of services and number of services providers.

> Clearly defined sharing of risks

> Community ownership

REVIEW OF EXISTING SCENARIO OF PPP

POLICY PRESCRIPTION

Public-Private Partnership has emerged as one of the options to influence the growth of

private sector with public goals in mind. Under the Tenth Five Year Plan (2002-2007), initiatives

have been taken to define the role of the government, private and voluntary organizations in

meeting the growing needs for health care services including RCH and other national health

programmes. The Mid Term Appraisal of the Tenth Five Year Plan also advocates for

partnerships subject to suitability at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels. National Health

Policy-2002 also envisaged the participation of the private sector in primary, secondary and

tertiary care and recommended suitable legislation for regulating minimum infrastructure and

quality standards in clinical establishments/medical institutions. The policy also wanted the

participation of the non-governmental sector in the national disease control programmes so as to

ensure that standard treatment protocols are followed. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Government of India, has also evolved guidelines for public-private partnership in different

National Health Programmes like RNTCP, NBCP, NLEP, RCH, etc. However, States have varied

experiences of implementation and success of these initiatives. Under the Reproductive and

Child Health Programme Phase II (2005-2009), several initiatives have been proposed to

strengthen social-franchising initiatives. National Rural Health Mission (NRHM 2005-2012)

recently launched by the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India also proposes to support the

development and effective implementation of regulating mechanism for the private health sector

to ensure equity, transparency and accountability in achieving the public health goals. In order to

tap the resources available in the private sector and to conceptualize the strategies, Government

of India has constituted a Technical Advisory Group for this purpose, consisting of officials of

GOI, development partners and other stakeholders. The Task Group is in the process of finalizing

its recommendation.

5

REVIEW OF PPP IN THE HEALTH SECTOR

, the Centre as well as the State Governments have initiated a wide

During the last few years, J.-------- 1--------------' ’) arrangements

variety of public-private partnership

arrangements to

to meet

meet the

the growing

growing health

health care needs of the

populatronT^der fivebasic mechanisms in the health sector:

Contracting in-government hires individual on a temporary basis to provide services

Contracting out- government pays outside individual to mange a specific function

>

Subsidies-government gives funds to private groups to provide specific services

>

Leasing or rentals-government offers the use of its facilities to a private organization

>

Privatization-government gives or sells a public health facility to a private group

>

An attempt has been made here to encapsulate some of the on-going initiatives in public

private partnerships in selected states.

A. Partnership between the Government and the for profit sector

1. Contracting in Sawai Man Singh Hospital, Jaipur

• The SMS hospital has established a Life Line Fluid Drug Store to contract out low cost

high quality medicine and surgical items on a 24-hour basis ms'de the hosprtai.

a9ency

to operate the drug store is selected through bidding. The successful bidder is a propne y

agency, and the medical superintendent is the overall supervisor in charge of monitoring he

store and it's functioning. The contractor appoints and manages the re™neratl°" °f ‘he st^

from the sales receipts. The SMS hospital shares resources with the drug store such as

electricity water- computers for daily operations; physical space; stationery and medicines.

The contractor provides all staff salaries; daily operations and distribution of medicine,

maintenance of records and monthly reports to SMS Hospital. The SMS Hospital provides a

medicines to the drug store, and the contractor has no power to purchase or sell medicines

himself. The contractor gains substantial profits, could expand his contact and gam

popularity through ULFS. However, the contractor has to abide by all the rules and

regulations as given in the contract document.

. The SMS Hospital has also contracted out the installation, operation and maintenance of

CT-scan and MRI services to a private agency. The agency is paid a month y rent by

hospital and the agency has to render free services to 20% of the patients belonging to the

poor socio-economic categories

2. The Uttaranchal Mobile Hospital and Research Center (UMHRG) ia

among the Technology Information, Forecasting and Assessment Council (TIFAC), the

Government of Uttaranchal and the Birla Institute of Scientific Research (BISR). The motive

behind the partnership was to provide health care and diagnostic facilities to poor and rural

people at their doorstep in the difficult hilly terrains. TIFAC and the State Govt, shares the funds

sanctioned to BISR on an equal basis.

3 Contracting out of IEC services to the private sector by the State Malaria Control Society in

GufaralHs underway in order to control malaria in the state. The IEC budget from various

pharmaceutical companies is pooled together on a common basis and the agencies hired by-the

private sector are allocated the money for development of IEC material through a special

sanction.

Himachal Pradesh; Karnataka; Orissa (cleaning work of Capital Hospital by Sulabh International),

Punjab; Tripura (contracting Sulabh International for upkeep, cleaning and maintenance of the

G.B. Hospital and the surrounding area); Uttaranchal, etc.

5. The Government of Andhra Pradesh has initiated the Arogya Raksha Scheme in collaboration

with the New India Assurance Company and with private clinics. It is an insurance scheme fully

6

funded by the government. It provides hospitalization benefits and personal accident benefits to

citizens below the poverty line who undergo sterilization for family planning from government

health institutions. The government paid an insurance premium of Rs. 75 per family to the

insurance company, with the expected enrollment of 200,000 acceptors in the first year.

The medical officer in the clinics issues a Arogya Raksha Certificate to the person who

undergoes sterilization. The person and two of her/his children below the age of five years are

covered under the hospitalization benefit and personal accident benefit schemes. The person

and/oor her/his children could get in-patient treatment in the hospital upto a maximum of Rs. 2000

per hospitalization, and subject to a limit of Rs. 4000 for all treatments taken under one Arogya

Raksha Certificate in any one year. She/he gets free treatment from the hospital, which in turn

claims the charges from the New India Insurance Company. In case of death due to any accident,

the maximum benefit payable under one certificate is Rs. 10,000.

B. Partnership between the Government and the non-profit sector

1. Involvement of NGOs in the Family Welfare Programme

•

The MNGO (Mother NGO) and SNGO (Service NGO) Schemes are being implemented

by NGOs for population stabilization and RCH. 102 MNGOs in 439 districts, 800 FNGOs,

4 regional Resource Centers (RRC) and 1 Apex Resource Cell (ARC) are already in

place. The MNGOs involve smaller NGOs called FNGOs (Field NGOs) in the allocated

districts.

The functions of the MNGO include identification and selection of FNGOs; their capacity

building; development of baseline data for CAN; provision of technical support; liaison,

networking and coordination with State and District health services, PRIs and other

NGOs; monitoring the performance and progress of FNGOs and documentation of best

practices. The FNGOs are involved in conducting Community Needs Assessment; RCH

service delivery and orientation of RCH to PRI members; advocacy and awareness

generation.

The SNGOs provide an integrated package of clinical and non-clinical services directly to

the community

•

The Govt, of Gujarat has provided grants to SEWA-Rural in Gujarat for managing one

PHC and three CHCs. The NGO provides rural health, medical services and manages

the public health institutions in the same pattern as the Government. SEWA can accept

employees from the District Panchayat on deputation. It can also employ its own

personnel by following the recruitment resolution of either the Government or the District

Panchayat. However, the District Health Officer or the District Development Officer is a

member of the selection committee and the appointment is given in her/his presence. In

case SEWA does not wish to continue its services, the District Panchayat, Bharuch would

take over the management of the same.

2. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi and the Arpana Trust (a charitable organization registered

in India and in the United Kingdom have developed a partnership to provide comprehensive

health services to the urban poor in Delhi’s Molarbund resettlement colony. Arpana Trust runs a

health center primarily for women and children, in Molarbund through its health center ‘Arpana

Swasthya Kendra’. As contractual partners, Arpana Trust and MCD each has fixed

responsibilities and provides a share of resources as agreed in the partnership contract. The

Arpana Trust is responsible for organizing and implementing services in the project area, while

the MCD is responsible for monitoring the project. The MCD provides building, furniture,

medicines and equipment, while the Arpana Trust provides maintenance of the building, water

and electricity charges, management of staff and medicine.

7

MfISSiW

PHC There has been redeployment of the Govt, staff in the PHCs, however some do remain in

deputation on mutual consent. The agency ensures adequate stocks of essential drugs at all

times and supplies them free of cost to the patients. No patient is charged for diagnosis, drugs,

treatment or anything else except in accordance with the Government policy. The staff salaries

are shared between the Govt, and the Trust.

Gumballi district is considered a model PHC covering the entire gamut of primary health care preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative

Similarly in Orissa, PPPs are being implemented for safe abortion services and social marketing

of disposable delivery kits. Parivar Sewa Sanstha and Population Services International are

implementing the Sector Investment Plan in the state.

4 The Government of Tamil Nadu has initiated an Emergency Ambulance Services scheme in

Theni district of Tamil Nadu in order to reduce the maternal mortality rate in its rural area. The

major cause for the high MMR is anon-medical cause - the lack of adequate transport facilities to

carry pregnant women to health institutions for childbirth, especially in the tn ba areas. This

scheme is part of the World Bank aided health system development project in Tamil Nadu. Seva

Nilayam has been selected as the potential non-governmental partner in the scheme^ This

scheme is self-supporting through the collection of user charges. The Government supports the

scheme only by supplying the vehicles. Seva Nilayam recruits the drivers, tram the staff, maintain

the vehicles, operate the program and report to the government It bears the entire operating cost

of the project including communications, equipment and medicine, and publicizing the service in

the villages, particularly the telephone number of the ambulance service. However, the project is

not self-sustaining as the revenue collection is lesser than anticipated.