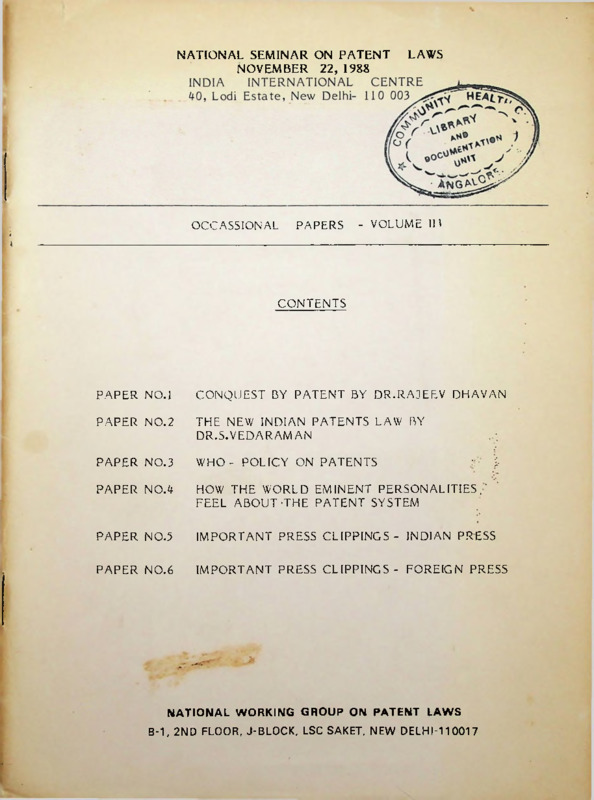

NATIONAL SEMINAR ON PATENT LAWS NOVEMBER 22, 1988

Item

- Title

-

NATIONAL SEMINAR ON PATENT LAWS

NOVEMBER 22, 1988 - extracted text

-

NATIONAL SEMINAR ON PATENT

NOVEMBER 22, 1988

OCCASSIONAL

PAPERS

LAWS

- VOLUME III

CONTENTS

PAPER NO.l

CONQUEST BY PATENT BY DR.RAJEEV DHAVAN

PAPER NO.2

THE NEW INDIAN PATENTS LAW BY

DR.S.VEDARAMAN

PAPER NO.3

WHO - POLICY ON PATENTS

PAPER NO.4

HOW THE WORLD EMINENT PERSONALITIES.'

FEEL ABOUT-THE PATENT SYSTEM

PAPER NO.5

IMPORTANT PRESS CLIPPINGS - INDIAN PRESS

PAPER NO.6

IMPORTANT PRESS CLIPPINGS - FOREIGN PRESS

;?

NATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON PATENT LAWS

B-1, 2ND FLOOR, J-BLOCK, LSC SAKET, NEW DELHI-110017

1

AjxiofML

PAP** "ol

COMMUNITY HEALTH CELL---------------------------39R V M-:.

i pi„n|, k-^„mnnn„i,

CONQUEST

BY

PATEL.

BY

RAJEEV

ONE

HUNDRED

DHAVAN '

LATER

YEARS

....

It is over a hundred years since the Paris Convention

was agreed by powerful nations in 1883.

Those that

defend the Convention visualise its history as a

linear development, with each change as an improvement

over what went before.

It is also possible, however,

to see the major changes that were proposed and accepted

as clumsy political compromises, each

in its own milieu.

to be explained

-The linear view is part of a

nineteenth century legacy which projects history as

progress.

The disaggregated view of events is essentially

cynical but also more hard edged in its emphasis on the

need to examine the more immediate context in whicn

historical changes occur.

The linear view concentrates

on the growth of ideas; whilst the disaggregated view

is more concerned with how these ideas were appropriated

and used as vehicles for social and economic action .

To combine both would be to learn the seeingly easy

lessons of history with unease.

If we have looked at

the discourse of ideas, it is because our cynicism has

not been fed with the availability of enough data to

fill out the context in which the discussion

* Director, Public Interest Legal Support &

Research Centre (PILSARC)

occurred.

In one sense, we can see the concept of 'patents' as

an ideological construct.

The justification for this

construct is the inventive genius of man; and, of course,

the duty owed to the inventor.

But, the inventor -

although an important part of the justification - has

long since ceased to occupy centre stage, either as a

subject or object of concern or even as a justification

for the vast apparatus of patent laws and policy built

ostensivly to protect his creativity.

The Paris Convetion

continues to honour his memory in a grand, but otheriwse

sad, gesture in Article 4 ter which reads

" The inventor shall have the right to be

mentioned as such in the patent"

With this obituary, the file on the inventor is closed.

His work and labour have been systematically appropriated

by powerful interests in society.

They are the real

actors in the drama even if the poor inventor

was the

sine qua non of the initial justificatory principle.

But,there is a vast difference in providing a just

recomepnse for creative genius; and finding a less absolute

business equity for someone who has either stolen or

appropriated the creator's work or simply footed the bill.

And,

so the argument shifts from creativity to business.

Unsatisfactory questions loom large in both areas, for

even creativity

is never individual but builds on what

went before and a great deal of inventive work cannot

really be personalised as exclusive.

The nineteenth century origins of the Paris Convention

1883 are apparent from its inclusion of just about

everything within the notion of industrial property.

Everything was to be treated as invention; and

Article 1(3) unabashedly includes "wines, grain, tobacco

leaf, fruit, cattle, minerals, mineral waters, beer,

flowers and flour".

shopping list.

And, this was only part of the

No nation could cope with such a list

or even pretend to enforce the law if all these were

included in the definition of patents.

Yet, if this

. part of the Convention has been ignored, it is because

it is redundant.

However, it remains an important part

of the rapacious principle that even common property

which belongs to all of us can be appropriated and

clothed with a patent right.

It is better to start

at the other end to being with the assumption that all

invention and discovery belongs to society, subject to

some reward for the discoverer or inventor.

Very

fundamental notions of property are at stake in this

discussion.

Yet, even those would become trivialised

if the amplitude of patent rights should extend to the

limitless excesses of the Paris Convention.

But, if the inventor and the absurd expanse of patent

ability have both exited from the scene, what we are

left with is hard business demands.

Industrialists

and businessmen who have either commissioned or bought

the product of Research and Development (R&D) claim

a price for it far greater than they paid-

It is the

complexity of the price demanded that needs to be de

constructed for more considered attention.

It should

not be overlooked that the R&D is subsidized by the

State in which the R&D work is taking place (through

tax incentives and tax deductions) as well as through

the under-payment of scientists and others whose future

claims are not part of patent law but contingent on the

generosity of the largesse of the patent holder. This is

assuming that the inventors can be identified.

And,

even then, they would be the first to acknoledge that

their genius is built on the cumulative endeavours of

persons in. the past and elsewhere in the world. In this

scenario, the claim for a patent is something like a

lottery.

Whoever gets there first gets the prize - not

just a part;

but all of it.

And, the question is whether

the prize (or the price, depending on how we look at it)

should be a world wide domination of a particular sphere

of economic activity; and for how long 1

There is a threat in all this.

The argument ersatz

inventors is that if they are not assured world domination

for an extended period of time, they will quit^. They will

stop research and development.

They will stop being inventive.

Or, they will simply become terribly secret.

This is not

a threat; it is a bluff even if there are times when we

tend to agree to take it seriously.

The inventors will

continue to invent although society must think through

less commercial ways in which their creativity can

be given support.

The profiteers will continue to

seek profits having lost only

an initial advantage,

with their loss being the gain of the world. And, yet

the argument is never about wholly taking away their

advantages; but, how much and to what extent ?

So,

let us return to the quest for world domination

as a prize of having got there first.

As things stand

at pressnt, they are not denied this world domination.

They always have the option to register their patent

in indidiual countries, with each country negotiating

its own terms through its laws.

other country first.

But, this is not acceptable

Someone else may get to some

to our patent holders.

Why enter into a race

can pre-determine the result "?

when you

The technique to do this

is the right to priority in the Paris Convention

(Article 4).

This is the twelve month edge : a patent, howsoever

incompletely, registeredn one country can be registered

in all the others.

And because the Convention decrees

the independence of each patent in each country, one

registration is not contingent on the others,

including,

perforce.

With the prospect of world wide domination assured, the

next task is to work out the obligations that are owed

to the countries who have permitted such domination. The

first question is whether any serious obligation is owed

to the country in question.

The Paris Convention started

off on the basis that no obligation was really due. The

patent holder could simply use his patent rights as an

import monopoly with no obligation to commercially work

the patent in that country.

The recipient country was,

thus, treated as a dumping ground for goods, processes and

technical information on

patent holder.

terms wholly dictated by the

This initial position was so untenable,

so unmistably absurd and so embarassingly one-sided that

the entire history of the Paris Convention for the last

hundred years has been taken up in correcting its absurdity.

But,this process has been slow and grudging.

The

suggestion that the patent holder should be forced

after three years to compulsorilylicense someone

was immediately undermined by allowing the patent holder

to wriggle out of such a demand by pleading justification

for his inaction for not working the patent in that country.

And/ the terms of the justification can be exasperatingly

wide.

The injunction Lnat two years after the compulsory

licence was granted, the patent should be revoked is

de-limited by the requirement of a generous examination

of whether the abuse of non-working has been rectified

by the compulsory licence.

In this way, the patent holder

has his way all the way, with a formal concession to the

recipient country that it can - in the ultimate analysis -

force the patent holder to actually commercially work the

patent in a country which he had hitherto simply used as

an exclusive import zone.

The ultimate success of the Paris Convention lay in

the fact that by creating terribly harsh sounding

restrictive concepts like compulsory licensing, revocation

and forfeiture, it gave the appearance that it was

taking a very tough line on patent holders.

The truth

was less harsh and much more pleasing for the patent holder.

With all the advantages of exclusivity, he was faced with

some widely phrased stumbling blocks which if kept low-key

and ambiguous were surely surmountable in any event he had

a wide choice of potential licencees on payment. The

Paris Convention appears to have made concessions to the

public in erest by mystifying both the discourse and the

need to define international objectives more clearly.

The fidelity of multinational corporations and the more

powerful nations to the Paris Convention rests on the

fundamentally uncanny truth that they Convention has

given away much less of the patent holder's right than

it appears.

One of the real difficulties with all these discussions

is that it is assumed that all the nations who are

signatories to any international agreement are, by and

large, equal'in their economic prowess and capacity for

technology. But,they are not. The result is that any

international convention of this nature works elliptically

to the advantages of the more economically and

technologically powerful nations of the world. The

assumption of equality is unfounded; but, as long as

it is made, the sharp division of the world

nations

eludes a formal description for the record.

But, we need to return to basic questions about nature

of the patent right.

Never has so much been claimed by

one entity for the work done by others.

reason why our starting point,

There is no

like that of the Paris

Convention, should be to create a mystical individual

property right around what is the collective creation of

society.

Having cheated society by isolating a social

creation as an individual right, we have conceded too

readily to the patent holder’s claim for national and

world domination in that sphere of activity.

The price

asked, and readily given, is too high as either a national

or global price.

The responsibility assumed by the patent

holder is too low, treating nations and socieites as

market dumps and manufacturing sweat shops.

The blackmail

to whithold future technology and start a trade war is

unconscionable; but, it helps to tell us what the debate

is really about.

The weaker nations are surely right

to

say that they will not pay the price, accede to the

blackmail or give up their right to be treated as more

than a market dump or a sweat shop.

Yet the more powerful

nations persis in their quest to divide the world into

an over-expanding number of finite monopolies.

The argument is not one of principle; but of greed. That

it is backed by the force of threats does not add to the

argument.

It simply unmasks it.

No. 1.1972

New Indian Patents Law

4dsi> a/4

S. Vedaraman

The New Indian Patents Law

The new Patents Act,' which was passed by the Indian Parliament in Sep

tember 1970, was on the anvil for quite a long time and evoked consider

able interest both in India and abroad. The passing of the Act has been

widely acclaimed, despite some criticisms in certain quarters concerning

the legislation. Naturally, divergences of opinion and criticisms are bound

to exist with such a complex piece of legislation as this, in which several

interrelated interests have to be reconciled and accommodated.

The Joint Committee to whom the Bill was referred by the Parliament

for a careful and detailed consideration not only received written mem

oranda from several individuals^ business organisations and other associa

tions, but also personally heard evidence given by as many as 35 associa

tions and individuals from both India and abroad, although the process

occupied the Committee for quite a length of time.2 The Parliamentary

Committee’s decision to invite memoranda and oral witnesses from all

areas of the world in a matter which concerned the Indian economy was

widely acknowledged. Dr. Hans Harms of the Federation of the Pharma

ceutical Industry of the Federal Republic of Germany had this to say: “I

find it both remarkable and an expression of exemplary fairness that you

have decided to study the opinion of organisations and experts of other

countries concerning the provisions under consideration. The very fact

that the Indian Parliament, before changing the existing patent law, is

thoroughly weighing the pros and cons, and for this reason has again

called in a Joint Committee, has been respectfully acknowledged in the

Federal Republic of Germany.”’

Before I proceed to explain the important aspects of the new legislation,

I think it will be useful to state in brief the fundamentals of the patent

system with reference to its legal, social and economic aspects, partie

s' Dr. jur.; Controller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks, Bombay, India.

1 The Patents Act, 1970 (Act XXXIX of 1970) (1970 The Gazette of India Extra

ordinary, Pan 11, Sect. I). The Act was passed by Parliament and received the assent

of the President on September 19, 1970, and is to come into effect shortly.

2 Joint Committee on the Patents Bill, 1967, C.B. Il, No. 2.19 (October 1969).

3

Dr. Hans Harms, Evidence Before the Joint Committee on the Patents Bill on Jan

uary 23, 1969.

Irdaranian

11 C

Vol. 3

ularly from the viewpoint of economically underdeveloped and develop

ing countries such as India.

Introdnctic

The material progress and advancement of any society depend on the

capacity of its individuals to apply their minds and to invent new pro

cesses, products and mechanisms for the enrichment and betterment of

the life of its people. The society receives with great gratitude the prod

ucts of invention which make human existence richer, more worthwhile

and less burdensome, end which in turn advance the frontiers of knowl

edge and open up new avenues of enquiry for breeding further inventions.

It is, therefore, imperative that the society should provide the necessary

incentive to stimulate new innovations and technical improvements, since

the desire for economic reward is an important factor motivating inven

tions. An invention which has been made but not disclosed or used is of

no economic benefit to the community. Various incentives have been and

are being tried, of which monetary plans, status recognition, inventor’s

certificates and the patent system are the most conspicuous. The monetary

plans include cash and bonus awards, profit sharing schemes and retire

ment funds. The status recognition is made, for instance, by means of

promotion to superior rank and increases in salary. Under the scheme of

inventor’s certificates, the right to exploit the invention vests with the

State, but the inventor has a claim for appropriate remuneration. Some

of the inventors might be content simply with the feeling of accomplish

ment of having their inventions recognised through publication in scien

tific and technical journals, though such instances might be few and far

between.

Of all these schemes, experience has shown that the patent system —

stemming from the desire to obtain proprietary rights in commercially

valuable inventions — provides the most effective incentive to inventors,

industrial undertakings and other research sponsoring organisations who

derive from inventors the right to commercially exploit their inventions.

For this reason, the system of granting patents for inventions has come

to be universally adopted as the means for stimulating and encouraging

inventions and for establishing and promoting industries within a coun

try. Even the countries which had for some time abolished the system

were forced to reintroduce the same in view of its economic importance

to the evolution of inventions for the benefit of society.

A patent is a statutory grant by the Government to inventors and to

other persons deriving rights from the inventors, for a limited duration,

conferring on them the right to exclude others from manufacturing and

No. 1/1972

New Indian Patents Law

selling the patented article or using or imitating the patented process or

vending the resulting product.

The legal basis of the patent grant arises from the concept that the inven

tor is entitled to enjoy the fruits of his invention which resulted from

the exercise of his brain and skill. The patent docs not give him any posi

tive right with respect to his invention in the sense that the inventor does

not derive the right to work his invention solely from the patent grant,

but it docs give him the right to exclude others from making, selling and

using his inventions. But this right is to be subject to certain conditions

in the public interest. No patent legislation contemplates an absolute or

perpetual right of the inventor in his invention. For the sake of the public

interest and in order to promote the economic development of the coun

try, the legislation contains some restrictions on the patent grant such as,

for instance, a limited term of patent protection for the invention, the

requirement of compulsory working of the invention on a commercial

■scale, the licensing of the patent as a measure against abuse of the patent

monopoly by the patentee; and, in accordance with the public interest,

even the revocation of the patent for non-working, exclusion of certain

categories of inventions from the scope of patent protection, etc. Inven

tor’s rights must be recognised, but not without placing them in the

proper perspective. Society should not submerge the interest of the in

dividual inventor by denying him any right, nor should it allow him to

run riot by giving him an absolute right in his invention. The patent sys

tem, therefore, provides the necessary checks and balances on the public

and private interests in the invention: the interest of the inventor in his

creation on the one hand, and the social interest of inducing the inventor

to make the invention, the interest of the public in using the invention

once it is marketed and the interest of the Government in promoting the

economic development of the country on the other hand. As aptly put

by P. J. Michel, “Patent systems are not created in the interest of the

inventor but in the interest of the national economy. The rules and reg

ulations of the patent system are not governed by civil or common law

but by political economy.”'1

n

History of Indian Law

The Indian patent system had its origin in the “Act for Granting Exclu

sive Privileges to Inventors" of 1856,4

5 which provided for the protection

4 1 P. J. MlCIIEL, Introduction to the Principal Patent Systems of the World 15.

5 Act VI of 1856. See 2 Theobald's Legislative Acts of the Governor-General of India

in Council 397 (1868).

1'cd.tr.inhtn

IIC

Vol. 3

of inventions in India. Owing to certain formal deficiencies," this Act was

repealed in I 857, but the provisions of the repealed Act were later re

enacted with slight modification in 1859.’ The “Patents and Designs Pro

tection Act”' was passed in 1872 for the purpose of legally protecting

designs,-and an amending Act affording protection to inventors desirous

of exhibiting their inventions at exhibitions was passed in 1883.’ In 1 888,

the law contained in the three Acts of 1859, 1872 and 1883 was con

solidated into a single Act,1" which was subsequently revised and replaced

by the existing Indian Patents and Designs Act of 1911." This latter Act

has also been amended from time to time, one of the notable amendments

being the provisions introduced in 1952 relating to the compulsory licens

ing of patents in the field of food or medicines at any time after the seal

ing of the patent.'As may be seen, the patent system has thus been in vogue in India for

nearly one hundred' and fifteen years. But it has not led to encouraging

results in India since it is a developing country. It was obvious that the

patent law of a country such as India, which is in its developing stage

and which is being provided with a dynamic industrial base, should be

so designed as to enable the country to achieve rapid industrialisation and

to obtain, as quickly as possible, a fairly advanced level of technology,

giving inventors and investors sufficient inducement and protection

through patent grants while at the same time safeguarding its national,

economic and social interests. To this end the law required substantial

changes to provide for compulsory working of patented inventions for

the public advantage, compulsory licences, and licences of right to prevent

abuse of patent rights by patentees who use the system merely as a means

of securing an importation monopoly without exploiting the patented

invention by actually manufacturing within the country that granted the

patent and thereby promoting the interests of its national economy and

industry. The need for a comprehensive revision of the law relating to

patents in India to suit our country’s developing economy was, therefore,

6

Because the Queen had not given previous sanction, it was advised that the Indian

Legislative Council was not competent to pass rhe Act, and therefore, the Court of

Directors of the East India Company disallowed it.

7

Act XV of 1S59.

8

Act XIII of 1872, passed in the form of an Act amending the 1859 Act.

9

10

The Protection of Inventions Act, 1883 (Act XVI of 1 883), passed as a preliminary

to the Calcutta Exhibition of 1883 and 1884.

The Inventions and Designs Act, 1SS8 (Act V of 1888).

11

The Indian Patents and Designs Act, 1911 (Act II of 1911) (Calcutta, Supdt. Govt.

Printing, 1911).

12

Act LXX of 1952, adding Sec. 23CC to the Indian Patents and Designs Act, 1911.

No. 1/1972

Neu* Indian Patents Law

recognised soon after independence; and the /natter was the subject of

two Expert Enquiries, the first by the Patents Enquiry Committee” and

the second by Shri Justice Rajagopala Ayyangar.” Both the enquiries re

vealed that “the Indian patent system has failed in its main purpose,

namely, to stimulate inventions among Indians and to encourage the

development and exploitation of new inventions for industrial purposes

in the country so as to secure the benefits thereof to the largest section

of the public.”” The new Patents Act is based mainly on these studies,

although incorporating a few changes in the light of further examination

at various levels, particularly with reference to patents in the important

fields of food, drugs and chemicals.

I may now briefly refer to the salient features of the new Patents Law

in India.

General Principles oj Patent Grant

The Act recognises the importance of stimulating inventions and encourag

ing the development and exploitation of new inventions for the industrial

progress of the country. Section 83 of the Act enunciates the general

principles of patent grant and also broadly the general philosophy of the

Act in the following terms:

“(a) that patents arc granted to encourage inventions and to secure that the

inventions arc worked in India on a commercial scale and to the fullest extent

that is reasonably practicable without undue delay; and

(b) that they are not granted merely to enable patentees to enjoy a monopoly

for the importation of the patented article."

Principle oj National Treatment

The new Parent Act does not put any limitations or restrictions on for

eigners in the matter of applying for or obtaining patents in India.

Science and technology has no territorial barriers, and, as such, there is

no discrimination between nationals and non-nationals in any respect;

13

Patents Enquiry Committee 194S-1950, Interim Report (August 1949), Final Report

(April 1950).

14

N. Rajagopala Ayyangar, Report on the Revision of the Patents Law (New Delhi,

1959).

15

Patents Enquiry Committee 1948-1950, Interim Report 165 (z\ugust 1949).

lie

Vol. 3

and all the provisions ot the Act are applicable mntatis mutandis to both

nationals and foreigners. Mow ever. Section I 34 of the Act provides that

where any country does not accord to the citizens of India the same

rights with respect to the grant of patents and protection of patent rights

as it accords to its own nationals, no national of such country shall be

entitled to any privilege under the Indian Law.

Inventions Not Patentable

The kinds of inventions which are not patentable are codified in the Act.

In the past, the question of patentability had been governed generally by

British precedents, but with the rapid expansion of technological devel

opments and the broadening of the area of inventions and discoveries, it

was considered necessary that there should be a specific provision in the

law concerning this matter. Section 3 of the Act stipulates that the fol

lowing are not inventions within the meaning of this Act and, hence, are

not patentable. As may be seen, the kinds of inventions included in this

Section are almost universally not patentable.

”(a) an invention which is frivolous or which claims anything obviously con

trary to well established natural laws;

(b) an invention the primary or intended use of which would be contrary to

law or morality or injurious to public health;

(c) the mere discovery of a scientific principle or the formulation of an ab

stract theory;

(d) the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance

or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known

precess results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant;

(e) a substance obtained by a mere admixture resulting only in the aggregation

of the properties of the compounds thereof or a process for producing such

substance;

(f) the mere arrangement or re-arrangement or duplication of known devices

each functioning independently of one another in a known way;

(g) a method or process of testing applicable during the process of manu

facture for rendering the machine, apparatus or other equipment more efficient

or for the improvement or restoration of the existing machine, apparatus or

other equipment or for the improvement or control of manufacture;

(li) a method of agriculture or horticulture;

(i) any process for the medicinal, surgical, curative, prophylactic or other

treatment of human beings or any process for a similar treatment of animals

No. 1/1972

New Indian Patents Law

or plains to render them free of disease or to increase their economic value or

that of their products."

Under Section 20 of the Atomic Energy Act of 1962, inventions relating

to atomic energy are already unpatentable. Accordingly, Section 4 of the

Patents Act of 1970 specifically excludes inventions in this field from

being patentable so as to make the Patents Act self-contained.

Search for Novelty

The Indian Patents and Designs Act of 1911 did not contain any specific

provision requiring the Controller to make a compulsory search to ascer

tain the novelty of an invention before its acceptance. Nor did the Act

deal clearly with the problem of what constituted anticipation. The new

Patents Act, however, removes this ambiguity and provides for a com

pulsory search, extending to prior publications not only in India, but also

in any other part of the world.10 The basis of this provision is that an

invention which is published abroad before the date of the corresponding

application for a patent should not qualify for the grant of a patent.

Accordingly, publications which are capable of constituting anticipatory

prior art include publications in India and elsewhere appearing before the

priority date. This brings the legal position in India, in this respect, in

line with most of the other countries of the world.

We are aware of the problems and difficulties in organising the search

system with the ever increasing volume of search material and the devel

opment of narrow fields of science and sophisticated technology. This has

rendered the examination of inventions more difficult than ever before.

However, we have been trying to organise and equip our Patent Office

adequately, not only for the purpose of fulfilling the statutory provisions

of the Act, but also to enhance the utility of the Indian Patent Office by

rendering it an effective instrument for diffusion of scientific and tech

nical knowledge.

Patentability of Inventions

in the Area of Chemicals, Food and Drugs

Section 5 of the Act provides that in the case of inventions relating to

substances intended for use as food, drugs or medicines, or substances16

16 Sec. 13(2).

I rd.Iranian

I

IIC

Vol. 3

products, particularly in the developing and underdeveloped countries,

would seem to he very revealing. I am referring to these matters just to

emphasize that the special steps taken by the Government of India

through this patent legislation were dictated by social needs and the

public interest, and that these steps arc supported by opinions held even

in the developed countries. The Government and the Parliament in India

have considered the views of all schools of thought regarding this issue

and have brought about a fair and reasonable compromise between the

extreme views, t’/z., total abolition of patents in these fields on the one

hand and a liberal protection of patent rights on the other, keeping in

view the interest of the patentee as well as the interests of the public at

large.

The term of grant for drug patents as laid down in the Act would thus

seem to be adequate to ensure a fair return to the patentee. Besides, this

shorter term of patent protection might also stimulate quicker and wider

commercial exploitation of patented inventions within the country,

thereby making available these common necessities in adequate quantity

and at reasonable prices.

Licensing Provisions

As I said earlier, one of the serious handicaps which India in common

with other countries has been experiencing has to do with patents which

are not worked for the benefit of indigenous industrial development but

which are merely held to secure a monopoly for importation. The Act

thus includes elaborate provisions to discourage abuse of patent rights.

Compulsory licences can be applied for at any time after the expiration

of three years from the sealing date of the patent. The provisions for

granting compulsory licences-' are more or less along the lines of the pro

visions contained in the statutes of the United Kingdom and other Com

monwealth countries. In order to obtain a compulsory licence an appli

cant has to prove one or more grounds (under Section 90 of the Act) and

satisfy the Controller as to his ability to work the invention and as to

certain other facts. The procedure in such cases is basically the same as in

the past. The new Act also provides for an appeal to the High Court

from the decision of the Controller in such cases.2’’ Involving as it does

protracted legal proceedings before courts of appeal, experience has

sho.wn that the provision relating to compulsory licensing has not

been, h.or is likely to be, very effective even under the new Act since

24 Sec.

X

25 Sec. 116(2)..’

No. 1/1972

/Vcu1 Indian Patents Law

the patentee can delay the actual grant of the licence by resorting to

judicial processes. By the time the case is finally settled, the patent itself

might already have expired. While this situation can be tolerated in

ordinary cases, remedial measures have to be found and provided for in

the vital areas of public interest. Accordingly, in view of their paramount

importance to public health and well-being, it was considered necessary

that the legal procedure for the granting of licences for food, drugs and

medicines be simplified. Because chemicals are directly related to the pro

duction of pharmaceuticals, apart from their general importance in the

context of industrial development, it is obvious that the granting of licen

ces with respect to such patents should be handled similarly. The statute

has, therefore, provided that all patents granted under the new Act in

the area of food, drugs, medicines and chemicals shall, upon the expiration

of a period of 3 years from the dates of their grant, be deemed to be

automatically endorsed with the words “Licences of Rights”,20 and that

any interested person shall, as a matter of right, be entitled to a licence

under such patents*27 subject, of course, to the payment of royalties. The

Controller may, before the terms of the licence have been mutually

agreed upon or decided by him, permit the prospective licensee to work

the patented invention on such terms as the Controller may, pending

agreement between the parties or decision by the Controller, think fit to

impose.28 This provision is intended to ensure that legal proceedings do

not delay the establishment of production in such vital fields as food,

drugs, medicines, and chemicals.

Provisions in the patents laws relating to the endorsement of patents as

“licences of right” are not infrequent. There is, for instance, a provision

for the endorsement of patents, at the request of the patentee or on ap

plication by the Government or a third party in the U.K. Patents Act.29

Even in the Model Law for the Developing Countries on Inventions

drawn up by BIRPI, similar provisions have been referred to.30 The sig

nificant difference in the recent Indian Patents Act, however, is that the

endorsement is automatic and statutory,31 although the effect of such an

endorsement is the same. Only recently, the Economic Council of Can26 Sec. 87(1).

27 See. 88(1).

28 Sec. 88(4).

29 Patents Act, 1949, 12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6, c. 87, § 35.

30 BIRPI, Model Law for Developing Countries on Inventions 67 (Geneva, 1965).

31 The automatic endorsement applies only to food, medicines, drugs or chemica]

ever, according to Sec. 86 the Government may apply for endorsement oLpCi

ular patent as a “License of Right”, and in such cases the Controllei

investigation similar to that for “compulsory licences."

Il (

J.

OD

* <

ANO

OOCOM6NTAT1ON

uNH

.

ada, after four anil one-half years of study, has made a similar proposal

that all Canadian patents should normally become eligible for an auto

matic non-exclusive licence to manufacture in Canada 5 years after the

application for the patent?- We do not have, however, any information

concerning the result ol this recommendation. But, the special provision

in India?’ as may be seen, is limited to the vitally important sectors of

national health and welfare and does not apply in.other cases. Here again,

the endorsement is effected only after 3 years from the date of sealing in

the same manner as is the case for the compulsory licensing provision.

This is in keeping with the spirit of the Paris Convention.

In this connection, it has been questioned why the Controller should not

look into the technical competence and the financial ability of the appli

cant for a licence under an endorsed patent just as in the case of an appli

cation for a compulsory licence. Bur it may be pointed out that though

such questions would be relevant in the case of an application for a com

pulsory licence, in the case of'a patent endorsed with the words “Licence

of Right”, such requirement will be out of place. After a patent is en

dorsed with the words “Licence of Right", the licence is to be granted

as a matter of right, and any questions which may have the effect of

denying him the right to.a licence will be doing violence to the language

of the expression “Licence of Right”. After all, a licence under a patent

is not a manufacturing licence but only a legal protection against infringe

ment of the patent. It may be mentioned that in such important fields as

food, drugs, and medicines, the prospective manufacturer — be he either

the patentee or a licensee — will have to obtain a licence under the Drugs

and Cosmetic Act or the Prevention of Pood Adulteration Act, as the

case may be, and satisfy the Government that the products conform to

the required standards.

In this regard it is relevant to recall BIRPI’s commentary on Section 45

of the Model Law:

“There is a substantial diflerence between compulsory licences and licences of

right in that in the case of compulsory licences the applicant must justify his

request . . . and meet certain requirements . . . whereas this is not the case as

far as licences of right are concerned. This system may be specially attractive

to developing countries because once a patent is thrown open to licences ol

right it will no longer depend on the will of the owner of the patent whether

32 Economic Coincii oi Canada, Report on Intellectual and Indurtrial Property 91

(Ottawa, Information Canada, 1971).

33 See. 87 (providing for the automatic endorsement for patents in the fields of food,

medicines, drugs and chemicals).

No. 1 1972

t\’cw huiian Patents Law

the patent will be exploited in the country; anybody can obtain a licence, and.

on the basis of that licence, work the patented invention in the country.’’31

The effect of the provision in the new Patents Act is precisely as above.

If the Controller were to make any sort of investigation before granting

a licence, it would result only in delaying the grant ot the licence and

wotdd defeat the very purpose of the provision. In order to protect the

interest of the patentee, the statute, however, provides for an appeal to

a superior court of law on the question of the terms and conditions of

licences granted with respect to patents endorsed or deemed to be en

dorsed under the Act?3

It should be appreciated that the basic intention of these provisions is to

ensure that essential articles like drugs, medicines and food will be avail

able to the public in sufficient quantity and at reasonable prices, and at

the same time ensure a reasonable return to the patentee on his invention.

The patentee will have a period of 3 years from the date of the grant of

the patent in which to establish production in the country and to take

steps for making the patented products available to the public at a reason

able price. If this is done, there is no reason why anyone else should con

sider entering the same business in an attempt to compete with the pat

entee by securing a licence, even though one could be secured as a matter

of right. In other words, it can be seen that the provision regarding the

granting of licences under patents automatically endorsed will become

really effective and advantageously utilized only if the patentee fails to

discharge his obligation.

Royalties

Section 95(1) provides that in settling the terms and conditions of a com

pulsory licence, the Controller shall endeavour to secure —

“(i) that the royalty and other remuneration, if any, reserved to the patentee

or other person beneficially entitled to the patent, is reasonable, having regard

to the nature of the invention, the expenditure incurred by the patentee in

making the invention or in developing it anil obtaining a patent and keeping

it in force and other relevant factors;

(ii) that the patented invention is worked to the fullest extent by the person

to whom the licence is granted and with reasonable profit to him;

(iii) that the patented articles are made available to the public at reasonable

prices.”

The above provision, which contains the guidelines to the Controller in

the matter of fixing royalties and settling terms in granting a compulsory

3*1 Bl KPI, supra note 30, at 67.

35 Sec. 116(2).

licence, corresponds to Section 39(1)(a) of the U.K. Patents Act of 1949

and Section 69 ol the Canadian Act of 1935.:"'‘

However, in the case of patents relating to food, drugs and medicines, by

reason of their importance to public health and welfare, the statute pro

vides that the royalty and other remuneration reserved to the patentee

under a licence (granted as of right) shall not exceed 4"/o of the net ex

factory sale price in bulk of the patented article.36

37 Needless to say, 4%

is only the ceiling or the maximum royalty allowable, and each case will

be decided within this limit depending on its own merits. This statutory

ceiling, however, as already indicated, is applicable only with respect to

patents within this special field, viz., food, drugs and medicines, and does

not apply to other categories of patents, where the allowable royalty (in

the case of a compulsory licence) will be determined in light of the pro

vision in Section 95 (1) of the Act.

I would like to point out one important aspect in this connection, name

ly, that the maximum rate of royalty, viz., 4°/'o for patents relating to

food, drugs and medicines, is not arbitrary or without basis. The normal

practice in connection with licences granted under Section 23CC (inven

tions relating to food, drugs or medicines) of the existing Indian Patents

and Designs Act of 1911 has generally been to fix a royalty not exceed

ing 4°/o of the ex-factory wholesale price of the manufactured articles.

Even in cases other than compulsory licensing, the royalties allowed gen

erally were ranging between 2 and 5°/o of net sales in the field of medi

cines and pharmaceuticals.38 It will, therefore, be appreciated that the

statutory fixation of a ceiling on the royalty should not be a matter of

concern to anyone, since what the new law does, in cftect, is to give stat

utory effect to the existing practice, and then, too, only in the case ol

such essential items as food, drugs and medicines. This is intended to

enable the prospective licensee to know his maximum liability as regards

royalties and to assure a reasonable return to the patentee, while at the

same time guarding against high prices of products in the sensitive fields

of food, drugs and medicines.

Use oj Patented Inventions by the Government

The provisions relating to Government use of patented inventions are

contained in Section 100 of the Patents Act and arc basically along the

36 The Patent Act, 1935, 25 & 26 Geo. 5, c. 32,

66, 67.

37 Sec. SS(5).

38 Report of the Retene Rank of India on Foreign Collaboration in Indian hidittlty

(1968).

1 1972

.Vc^- Indian Paten:? Lazv

lines ol the provisions in Section 46 cl the U.K. Patents Act of 1949.

Similar provisions are also to be found in Section I 25 of the Australian

Act,3"

The use of a patented invention tinder this section is subject to the pay

ment of royalties in an amount agreed upon by the Government, or

its authority, and the patentee, or in the case of default of agreement, in

an amount to be determined by the High Court under Section 103 of the

Act. Thus, the interests of the patentee are fully safeguarded.

However, in the context of the responsibilities which a welfare state as

sumes, it is necessary to ensure that the existence of patent rights does

not hamper its development programmes or its welfare activities. There

fore, for this purpose and in order to ensure that a scarcity of the pat

ented article, including drugs and medicines, does not arise and lead to

high prices, the Government is vested with powers of an enabling nature

whereby it can make use of or exercise arts’ patented invention merely for

its ow n purpose. Under this provision (Section 47 of the Act) the Gov

ernment can import patented drugs and medicines if they are merely for

its own use or for distribution in any approved medical institution, with

regard to the public service that such institution renders. It is the inten

tion not to go beyond this limited use, even when the circumstances so

warrant in the interest of the common good. Under this section it is also

provided that use for experimental purposes of patented articles or pro

cesses, as well as the articles or products made by a patented process or

a patented machine or apparatus, will be exempted from infringement

actions.

Tn this connection, I may refer to the observations made by the U.N.

Secretary General in his Report on the Role of Patents in the Transfer

of Technology to Developing Countries. The report says —

“In spheres of production vital to the national interest and the development

of special resources, or to public health, limitations on patentability er pro

vision for limiting the scope of the patent grant by special working or com

pulsory licensing in the public interest are natural, as is evidenced by the

inclusion of such limitations in the legislation of many countries."10

Appeals

Under the provisions of the Indian Patents and Designs Act of 1911,

appeals from decisions of the Controller were to lie in the majority of

39

40

Patents Act 1952 (Act 42 of 1952).

U.N. Si.cRiTAitY-Gr.xi.itAL, The Role of Patent? in the Tiansfer ol Tcibnology

Under-Developed Countries 22 (1964).

1 IC.

Vol 3

cases with the Central Government." Under the new Act, however, in

all cases appeals from the decisions, orders and directions of the Con

troller will lie only with the High Court, which is the highest court in

each state in India.'• 1 he normal judicial process in accordance with the

rule of law is thus assured to parties in all proceedings under the Act.

International Arrangements

As regards reciprocal or Convention arrangements, in the past such recip

rocal arrangements for the mutual protection of inventions have been

limited to only the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth countries.1'

The new Act has removed this limitation and enables the Government

to conclude bilateral or multilateral arrangements or treaties with any

other country or countries for the mutual protection of inventions."

Conclusion

From what I have stated above, it should be clear that the main object

of the Act is to promote research and inventions and to accelerate the

indigenous industrial growth and, through a well-regulated patent sys

tem, to prevent the exploitation of a monopolistic patent position. The

Act is also calculated to make our country free from continued external

dependence as regards the supply of materials and machinery. As 1 have

already clarified, the Act seeks to accord equal treatment to both nation

als and non-nationals in all respects, and to provide to them or their

licensees ample opportunities to commercially work their inventions with

in the country; and if they make the best use of these opportunities there

should be no necessity to have recourse to any of the special provisions

in the Act in order to ensure that patents are not used in such a way as

to retard the economic development of the country.

The new Patents Act is the result of a detailed study of the economic

conditions of the developed as well as the developing countries of the

world with reference to their laws relating to patents, and has been de

signed to suit the special needs of our country. It has been the subject of

careful consideration at various levels before enactment, including two

expert committees, a Parliamentary Committee and the Parliament itself

more than once. The enactment has been widely welcomed by different

sections of the public and industry in India.

4 1 Secs. 5 (2), 9 (3), 16 (5), 17 (6), 43 (4).

42

See. 116(2).

43

The Indian Patents and Designs Act, 1911, Sec. 78(A).

44

Sec. 133(1).

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

EB77/INF.DOC./3

ORGANISATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTfi

6 November 1985

occasional-

EXECUTIVE BOARD

r/o 3.

Seventy-seventh Session

Provisional agenda item 14

POLICY ON PATENTS

Information paper on WHO patents policy

The Thirty-fifth World Health Assembly requested that progress in

implementing the WHO policy on patents be reported periodically. WHO

agreement forms have been adapted to facilitate the achievement of the

objectives of the Organization in the most common funding situations.

No significant change has occurred in the number of patents held or

applied for, though WHO’s use of its interests in patents held by

research institutes is beginning to be reflected in concrete

arrangements with industry for the making available of health-related

products in the public interest.

1.

Introduction

Pursuant to a recommendation of the sixty-ninth session of the Executive Board,the

Thirty-fifth World Health Assembly (May 1982), in resolution WHA35.14, decided that it should

be the policy of WHO to obtain patent rights or interests in health technology developed

through WHO-supported projects where such rights and interests are necessary to ensure

development of the new technology, and to promote its*wide availability in the public

interest. This information paper updates a report on the early progress made in implementing

the new policy, which was considered by the seventy-first session of the Executive Board^

and the Thirty-sixth World Health Assembly.3

2.

General provisions

2.1 The implementation of resolution WHA35.14 is being increasingly linked with the growing

collaboration between WHO and industry, as partners in promoting the development and wide

availability of health technology. In most cases, patent rights in themselves, that is to

say the patents or other forms of industrial property and applications actually owned by WHO,

are of little direct benefit to WHO, which lacks the facilities and resources to exploit

them. On the other hand, they may be essential to an industrial enterprise interested in

collaborating with WHO, in order to protect the often substantial investment required to

develop and market useful technology.

2.2 Whenever a research project results in useful technology that may be patentable, the

first question that has to be answered in accordance with resolution WHA35.14 is whether or

not patent rights are necessary for the technology’s development and wide availability. The

basic answer is that, if the technology can be perfected and made widely available at a

relatively low cost, patent rights may not be necessary and the interests of the Organization

may best be served by placing the technology in the public domain. Where, however,

development involves considerable investment and commercial risk, patent rights should be

sought.. Normally, this question cannot be answered at the outset, and the first steps in the

patent protection process have to be taken in order for the rights to be safeguarded. The

1 Resolution EB69.R7.

Document EB71/22.

Document A36/6.

EB77/INF.DOC./3

page 2

protected rights can be abandoned later before substantial costs are incurred or they can be

continued, where necessary, until taken over by an appropriate non-profit entity or

industrial partner.

2.3 The specific provisions agreed between WHO and collaborating enterprises vary from case

to case, but they are designed to reconcile two general interests: the interest of the

Organization in ensuring that the finished products of the technology, and in certain

circumstances the technology needed to make that product, are available to the public health

sector on preferential terms, particularly in developing countries, and the interest of the

enterprise in obtaining a reasonable return on its investment.

2.4 The Organization has recently revised its standard "Technical Services Agreement"

covering WHO-funded projects with research institutions. Previously there were two

alternative forms of this agreement; one of them vested the patent rights initially in the

Organization, and the other vested the rights initially in the research institution, with WHO

retaining a patent interest in the form of free availability of the rights to it or its

nominees. The Organization will continue to ensure that it retains patent rights in

justified cases, particularly where it is providing most of the funds or intellectual input

for the research; but, for other cases, the agreement no longer attempts to specify the

patent interest to be accorded to the Organization if a useful invention should materialize.

Instead, if and when the research results in an invention, the parties are placed under an

obligation to negotiate an agreement covering the exercise of the intellectual property

rights granted to the research institution. Such an agreement will be based on the

attainment of the following objectives in the following order of priority:

(1)

the general availability of products resulting from the project;

(2) the availability of those products to the public health sector on preferential

terms, particularly in developing countries; and

(3) the grant to each party of additional benefits, including royalties, account being

taken of the relative value of each party’s financial, intellectual and other

contribution to the research.

3.

Patent rights

As of 15 October 1985, there have been 10 inventive efforts resulting in 16 patent

applications filed by or on behalf of the Organization, of which four applications concern

one particular invention and four other applications concern a related group of inventions.

Of the 16 applications, one was rejected, six have been abandoned, six have been granted

(one of which - a certificate of utility - has expired), and three are still pending. Of the

five patents which the Organization currently holds, two concern inventions which are not

actively being pursued (Drug delivery system and Tubal occlusion method); two involve the

same invention, which is currently undergoing toxicology testing (Steroid synthesis); and

one involves an invention (Long-acting esters) which is currently being tested and which is

covered by a first-option agreement with a commercial enterprise, which contains provisions

facilitating the making available of the product to the public sector. A list of WHO’s

patent rights is set forth in an annex to this information paper.

4.

Patent interests

4.1 In addition to the Organization’s patents and patent applications, WHO holds a

considerable number of interests in patents obtained by research institutions funded by it.

The term "patent interest" is used to refer to the right to demand a licence under a patent

or the transfer to WHO of certain patent rights.

4.2 In cases where there is a potential for further development of the subject of the patent

into a useful health-related product, WHO has exercised its interest in the related

intellectual property rights so as to ensure the wide availability of the product in the

public interest, in particular for developing countries. Two cases in which WHO has recently

exercised its interests are for a malaria vaccine and a fertility predictor. In the case of

each enterprise selected by the research institute to develop the product concerned, WHO has

concluded an agreement which contains provisions facilitating the making available of the

product to the public health sector, in particular of developing countries.

EB77/INF.DOC./3

page 3

5.

Consultations with other international organizations

5.1 The Secretariat consults appropriate services of the World Intellect^_1 Property

Organization (WIPO) as the need arises on relevant issues of intellectual property law in

order to best protect the interests of the Organization and the public sector. It also

follows certain aspects of the work of WIPO which are of particular interest to the

Organization, such as improving industrial property protection of biotechnological inventions.

5.2 The Secretariat also has provided information to the United Nations Industrial

Development Organization (UNIDO), at its request, in order to assist that organization in

developing its own patent policy.

EB77/INF.DOC./3

page 4

ANNEX

LISTING OF WHO PATENTS AND PATENT APPLICATIONS

Filing date

and country

Inventor &

programme

Subject

Current status

1.

'10.4.1979

USA

Decker

(HRP)1

Electro

coagulator

Rejected

2.

3.5.1979

USA

Heller

(HRP)

Drug delivery

system

Pat. No.

4 261 969

3.

20.7.1979

USA

Nakamura

(HRP)

Spermicides

Abandoned

4.(a) 4.8.1979

France

CrabbG

(HRP)

Steroid synthesis

(anordrin)

Certificate of Utility

No. 79-20926 expired

(b) 15.4.1980

USA

Crabbe

(HRP)

Steroid synthesis

(anordrin)

Pat. No.

4 309 565

(c) 29.7.1980

FRG

CrabbS

(HRP)

Steroid synthesis

(anordrin)

Abandoned

(d) 14.8.1980

UK

Crabbg

(HRP)

Steroid synthesis

(anordrin)

Pat. No.

2 061 278

5.

20.11.1979

USA

Buckles

(HRP)

Barrier

contraceptive

Abandoned

6.

16.12.1980

USA

Hoffman

(HRP)

Improved tubal

occlusion method

Pat. No.

4 359 454

7.(a) 29.1.1981

USA

Archer et al.

(HRP)

Long-acting esters

(certain cycloalkyl

derivatives)

Abandoned, since covered

by United States patent

No. 4 507 290 on longacting esters

(b) 7.4.1981

USA

Archer et al.

(HRP)

Long-acting esters

Pat. No.

4 507 290

(c) 19.5.1983

UK

Archer et al.

(HRP)

Long-acting esters

Abandoned, since now

covered by EPA^

(d) 31.1.1984

EPA2

Archer et al.

(HRP)

Long-acting esters

Pending

8.

3.12.1982

USA

Bone

(CFNI3/

FHE4)

Haemoglobin

screening device

Abandoned

9.

20.12.1984

UK

Rickman & Reed

(TOR)5

Microscope’

Pending (original 20.12.83

filing allowed to lapse;

immediately refiled)

10.

2.7.1985

CrabbS et al.

(HRP)

Testosterone

Pending

esters

1 Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human

Reproduction (HRP).

2 ••

’

European patent application** (application submitted pursuant to the

Convention on the Grant of European Patents, 1973).

3

Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute (CFNI).

Division of Family Health.

Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR).

HOW THE WORLD EMINENT PERSONALITIES

FEEL ABOUT THE PATENT SYSTEM

In the words of Sir William Holdsworth :

" The foreign patentee acts as a dog in the Manger, sends

the patented articles to this country but does nothing

to have the patented articles manufactured here. He

commands the situation and so our industries are under

our own law starved in the interest of the foreigner."

Sir Robert Reed was more outspoken

:

" Nothing can be more absurb or more outrageous than that

a foreign patentee can come here and get a patent and

use it, not for the purpose of encouraging industries

of this country but to prevent our people doing other

wise what they would do.

To allow our laws to be used

to give preference to foreign enterprise is to my mind

ridiculous".

Sneaking of the American Patent System, while giving

evidence before the National Economic Committee

Mr. Langer said :

" We are doing business abroad and we want to protect our

article, so that German or English manufacturer is not

able to copy it immediately and go into comoetltion with

us.

In other words, it is a great selling point for our

goods to have a protected export markets."

Patents were, therefore, admittendly taken by foreigners,

not in the interests of the economy of the country granting

patents or with a view to manufacture there, but with the

main object of protecting an export market from competition

from rival manufacturers.

In spite of this grossly apparent misuse and abuses of the

patent System, the system continues to exist, as Edith Penrose

aptly puts i t :

" partly because the custom is old and firmly established,

partly because of the pressure of the vested interests and

partly because the ideals of "International Co-ooeration",

"non-discrimination" and similar laudable sentiments have

been influential in shaping the thoughts of lawyers and

Statesmen" .

The exploitation and abuses of the patent system by

foreigners, who do not work the patents commercially in

the country of grant but use them merely as a means of

ensuring a monopoly of importation, has not escaped

criticism even in advanced and developed countries.

Speaking of the position of patents in USA, Floyd L. Vaughan

Savs :

" It is a contravention of our patent law and an economic

in justice to the American manufacturer to allow a foreigner

to take out a patent in this country merely for the purpose

of reserving the United States a market for his patented

"'-oduct which is manufactured abroad exclusively.

It means

the expulsion of all other would be inventors and competitors

from the industry covered by the patent and at the same time

the building up of the industry in other countries, all to

the detriment of the United States".

IT WAS NATURAL THEREFORE, FOR INDIA TO SHAPE ITS POLICY

ON SIMILAR LINES AND ADOPT ITS LEGISLATION IN ORDER TO

COUNTER THIS TENDENCY OF FOREIGN PATENTEES.

S mt. I nd i r a _G andhi at the World Health Assembl y

a t Geneva on 6th May, 198 1 said :

"

My idea of a better ordered world is one in which

Medical Discoveries would be free of Patents and

there would be no profiteering from life or death".

TECHNOLOGY POLICY STATEMENT OF GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

TO DEVELOP A SELF-RELIANT INDIA :

Extracts from Technology Pol icy ’ Sta temen t of

Government of India 1981 :

" The Government of India's Technology Policy Statement

1983 declares that "Our own immediate needs in India

for the attainment of technological self-reliance a

swift and tangible improvement in the condition of the

weakest sections of the population and the speedy deve

lopment of backward regions".

It further adds that

"Our future depends on our ability to resist .the imposi

tion of technology which is obsolete or unrelated to our

specific requirements and of policies which ties us to

systems which serve the purpose of others rather than our

own, and on the success in dealing with vested interest

in our Organisations ; governmental, economic, social and

even intellectual, which bind us to outmoded systems and

insti tu tions" .

EXTRACT FROM WIPO DOCUMENT NO.WIPO'IPL/

BM/4 DATED DECEMBER 3, 19 85

In considering the role of industrial property

in economic development, an initial clarification

needs to be made concerning the nature of the

industrial property system.

The industrial property

system does not exist in order simply to grant legal

protection to various facets of technology.

Rather,

the industrial property system is more correctly

perceived as an instrument of public policy whereby

legal protection is granted to various facets of

technology in order to promote certain social and

economic objectives, which typically include the

disclosure and dissemination of technology, the

stimulation of investment of resources in technology,

and the establishment of a framework for the deve

lopment and exploitation of technology".

lHPoR7M7'PHES..$ C.LI Pf/A/Gs-

____ __

„

--------------------------------- =---------- ----------------------------------- oeZ/^7oV/|t PfrrEK HQ 5

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY - OCTOBER 29,

Tailoring Patents Law to Suit MNCs

BM_________ ________________________ __________________

The prime minister’s tirade against indigenous technology which is

geared to import substitution serves advance notice that he is

ready to fall into trap of the Paris Convention on patents and the

GATT provision for protection of intellectual property.

CONCERNED scientists and technologists,

legal luminaries and social workers and even

some enlightened business interests have

woken up to the grave and imminent danger

that has emerged on the horizon to Indian

R and D and the contribution that Indian

scientists and technologists can and must

make to socio-economic development with

some measure of self-reliance. The)' had

been watching helplessly but with con

siderable dismay for quite some time the un

folding of official policy which had tended

more and more to strangulate Indian

R and D, open the doors wide for foreign

technology and capital to take up comman

ding positions in the Indian market and

overwhelm step by step domestic production

capabilities in several critical areas. What

they had not still bargained for, however, was

that the government led by Rajiv Gandhi was

getting ready to revise the well-tested policy

on patent protection and join the Paris Con

vention on patents which the government

had so far rightly refused to do. It is being

suggested that the government may take this

‘bold’ step by the middle of December this

year. The ground for this, according to some

well informed sources, is being prepared at

a rather hectic pace. These apprehensions

have been strengthened by the extension of

the so-called Rajiv Gandhi-Reagan Science

and Technology Initiative under which

transfer of high technology to India from

US is being regulated and managed. The

seminar being organised by the Federation

of Indian Chambers of Commerce and

Industry in the last week of November this

year with the active association and par

ticipation of the World Intellectual Property

Organisation (WIPO) is also considered

ominous in this context.

It is freely admitted by concerned high

officials that, though the pressure on India

for straightaway joining the Paris Conven

tion on patents has been somewhat relaxed

considering the sensitivity of the Indian

public on this score, the pressure for amen

ding the patent law of 1970, which had been

adopted in the teeth of the opposition of

multinational corporations and the

developed countries has been greatly inten

sified. What is being demanded is that pro

duct patents in particular should be reintro

duced across the board and the provisions

in the Indian law on compulsory licensing

and licence of right for manufacturing

patented products by the application of pro

cesses developed in India should be diluted.

This would amount to conforming with the

Paris Convention on patents without

formally joining it. It is quite on the cards

that these demands on India will find strong

articulation and support at the proposed

FICCI-WIPO seminar. A committee appoin

ted by the government last year to advice

whether or not to join the Paris Convention

is also about to submit its report and may

well be expected to reinforce the demands

and suggestions of WIPO for amending the

Indian patents law of 1970. This is how the

ground is meticulously being prepared to

force India to accept the line laid down by

WIPO on the patents issue.

The multinational corporations, on their

part, have drawn up a comprehensive plan.

of concerted action on the patents issue in

the wider frame of the protection of intellec

tual pioperty rights through the Uruguay

round of GATT. The round has on its agen

da a specific GATT provision for the pro

tection of intellectual property as an urgent

and pressing issue.

The representatives of multinational cor

porations from the US, Japan and western

Europe adopted in June this year a com

prehensive working plan to aclueve their aim

in the GATT round. They have demanded

the adoption of a code similar to the stan

dards or subsidies codes under GATT

auspices in order to sanction “effective deter

rent to international trade in goods where

there is an infringement of intellectual pro

perty provision”. What they are seeking is

an “effective enforcement mechanism”

under GATT system for countries which do

not join the Paris Convention on patents and

do not amend their national patent laws and

procedures to conform to the norms of the

Paris Convention for the protection of

intellectual property rights. The multi

national corporations have come down par

ticularly heavily on the provision for com

pulsory licensing for production of goods

which enjoy patent protection but are not

actually produced in the country. What is

being demanded is that a patent will be

deemed to have been worked by the patent

holder by only exporting the patented pro

duct and not necessarily producing it in the

concerned country. This demand goes

beyond even the Paris Convention which

allows licensing of production of a patented

product to a third party in the event of the

non-working of a patent. Multinational cor

porations are also seeking to further extend

and refine the scope of patent protection to

1988

REPORTS

high-tech areas such as the ‘layout design’

of a semiconductor chip or biotechnology.

These demands, if accepted and enforced

through the GATT mechanism, will hit the

developing countries, notably those, among

them India, which have acquired" and

developed scientific and technological

capability for finding alternative processes

for the production of patented products. The

import-substitution effort of the developing

countries is sought to be choked through the

patent system and the GATT provision on

the protection of intellectual property. The

multinational corporations are clamouring

for concerted action by the signatories to the

GATT code on protection of intellectual pro

perty against those who may choose not to

become party to the code.

What all this adds up to is that the

multinational corporations backed by the

governments of the developed countries are

demanding that the developing countries

strangulate their own R and D effort and

dismantle their production capabilities

which result in import substitution and

which compete with multinational corpora

tions and exports of the developed countries

to the developing countries. The moves of

the ruling establishment in India, encouraged

and supported by compradore business

interests and a section of the corrupt

bureaucracy with close links with multi

national corporations, to review and revise

the patent law of 1970 have, therefore,

caused grave apprehensions among Indian

scientists and technologists and all those,

among them some enlightened business in

terests, who stand for self-reliance and want

to strive to break the foreign stranglehold

on socio-economic and technological

development of the country.

The public affirmation by the prime

minister that the import substitution effort

in technology has been “one of the biggest

mistakes" has come as a shock to these sec

tions. Coming in the midst of mounting

pressure and open arm twisting by the

developed countries, in particular the US the

prime minister’s stand portends ill for Indian

R and D and technology. Rajiv Gandhi

chose to deliver his dictum on technology

policy and its aims in his characteristic hec

toring style on the occasion, ironically

enough, of presenting the 1987 Shanti

Swarup Bhatnagar awards to Indian scien

tists. It is a pity that the Indian scientists pre

sent on the occasion did not have an oppor

tunity to refute his extremely dangerous