HEALTH EXPENDITURES IN INDIA

Item

- Title

- HEALTH EXPENDITURES IN INDIA

- extracted text

-

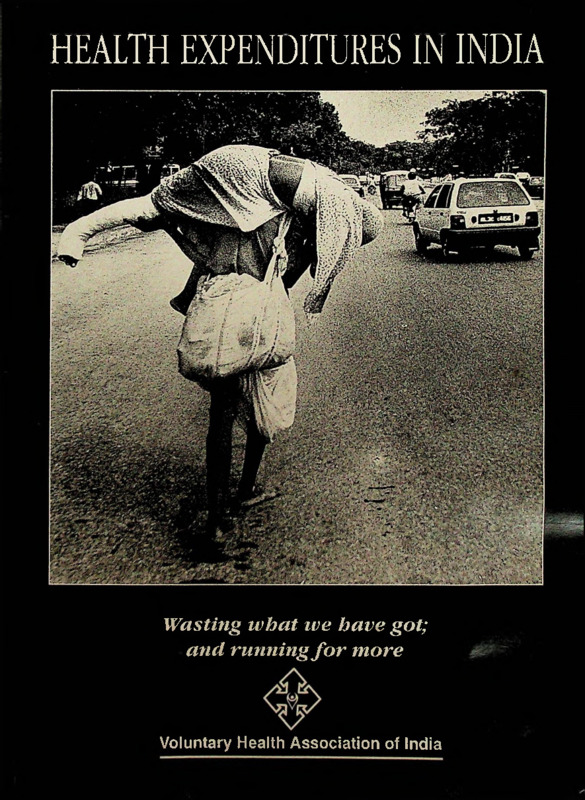

HEALTH EXPENDITURES IN INDIA

Wasting wbat ive have got;

and running for more

Voluntary Health Association of India

HEALTH EXPENDITURES IN INDIA

Wasting tvhat we have got;

and running for more

By

/

Dr. Bharat Jhunjhunwala

Voluntary Health Association of India

P

E

R

F

A

C

E

The considerable apprehension that we all had on the possible reduction of

financial allocation for the social sector was put to rest by the very encouraging

allocation of resources by the government in the recent budget. The present

government's seriousness ofpurpose to strengthen this sector is also indicated by the

fact that the country is willing to borrow moneyfrom International Institutions for

this so-called "non-profitable" sector.

For some time now, VHAI was looking into the current pattern of external

assistance to the health sector of this country and its utilisation. Unfortunately, the

findings of the study have revealed some startling facts. Across the board we see

extemely meagre utilisation of the assistance provided in the health sector. It is a

matter ofgreat shame and sorrow that on the one hand we find umpteen number

of Primary Health Centres and other health infrastructure are defunct due to

shortage of basic facilities and on the other, the valuable resources are being

squandered away.

Without putting the blame on any particular quarter we want to state as we have

done before through various other well-researched documents that the time has come

to clean up the Augean stables at the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. A

feeble

Ministry cannot respond to the challenges of health care of 900

million people.

Alok Mukbopadhyay

Executive Director

Chapter I: Still a Long Way to Go

There is no doubt that the health of the people of India has been improving since the

beginning of this century. The two most important indicators of health are the Expectation

of Life at Birth (in years) and Infant Mortality Rate (Deaths per thousand Live Births). Both

these indicators have shown a tremendous improvement during this century.

Table 1

Health Indicators 1901-1991

Year

Expectation of life

at birth

(Years)

Infant Mortality

(per thousand live

births)

1901

23.8

N.A.

1911

1921

22.9

204

20.2

174

1931

1941

26.7

174

31.7

161

1951

32.1

146

1961

41.2

N.A.

1971

45.6

138

1981

54.4

119

1991

61.1

86

Source

Health Information of India, 1992, Ministry, of Health and Family Welfare,

1993- Tables 2.10, 2.11 & 2.04.

The expectation of life has increased from 20.2 years in 1921 to 61.1 years in 1991. Similarly

the Infant Mortality Rate has fallen from 204 deaths per thousand in 1911 to 86 in 1991. These

are no small achievements.

However, there is still a long way to go. We are still far behind the world standards which

have been shown in Table 2.

•

Table 2

Internationa 1 Comparison of Health Indicators, 1991

Country

Expectation of life

at Birth in 1991, (Years)

India

61

Developing World

67

Developed World

77

China

69

U.S.A.

76

Source : World Development Report, 1993-

1

It will be seen that India is not only far behind the developed world but even in comparison

to other developing countries.

Nearer home, Kerala has already achieved an Infant Mortality Rate of 17 deaths per thousand

live births. The Infant Mortality Rate for the best and the worst states is given at Table 3.

Table 3

Estimated Infant Mortality Rates

State

Infant Mortality

Rate, 1991

(Per thousand live births)

Expectation of Life

at Birth, 1981

(Years)

Best States

Kerala

17

68.5

Maharashtra

64

58.1

Punjab

66

62.8

Uttar Pradesh

105

46.8

Madhya Pradesh

120

50.2

Orissa

127

50.8

86

54.4

Worst States

All India

Average

Source : Health Information of India, 1992, Table 2.05, 2.12.

The Infant Mortality rate varies from a low of 17 deaths per thousand live births in Kerala

to a high of 127 in Orissa—more than 7 times. Similarly, the Expectation of Life is at a low

of 46.8 years for U.P. in 1980 against 66.5 years for Kerala. Thus, what has been achieved

leaves no place for complacency. We need to go much faster.

2

Chapter 2 : Utilisation of Funds

We have seen that the health scene leaves much to be desired. On ther other hand, a scrutiny

of various internationally funded programmes shows that the funds are not being utilised

well.

THE WORLD BANK

The World Bank has emerged as a major lender in the health sector. The World Bank has

two windows for lending. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(IBRD) lends at commercial rates of interest which the International Development Agency

(IDA) lends at—concessional rates of interest. The typical IDA loan has 40 years maturity

period and an interest cahrge of 0.75 percent. Bulk of-the World Bank assistance in the health

sector comes from the IDA window. Considering that the value of money would have

depreciated to about 5 percent in 40 years and the loans would have to be repaid at that

value, the IDA assistance is virtually like a grant.

The commitment and utilisation of assitance by the World Bank in Health Sector is given

in Table 4.

•

SI.

Lending

No.

Agency

1.

IBRD

Project

Table 4

000 US s

•

Year of

Total

Sanction

Committme nt 1991-92

Utilisation

Total Utli-

Total

sation uptc

percent

Utilisation

31.3.92

Utilisation

per year

Percent

Industrial Pollution

Control

2.

IDA

Sixth Population

3.

IDA

Seventh Population

4.

IDA

Child Survival and

Project

Project

Safe Motherhood

1991-92

124,000

6,022

6,022

4.8%

4.8%

1989-90

87,200

4,387

19,027

21.8%

7.3%

1990-91

63,400

4,942

8,530

13.5%

6.7%

1991-92

160,900

13,146

13,146

8.2%

8.2%

Source . External Assistance 1991-92, Ministry of Finance.

It will be seen that the utilisation per year for World Bank Assistance has been in the range

of 5-8 percent.

The IDA has sanctioned another loan for National AIDS Control Programme in 1992-93. The

exact figures are not available but the total amount is reported to be in the range of USS 100

million, or Rs. 320 crores. The utilisation of funds till January 1994 is given in Table 5. It will

be seen taht only 3.4 percent of the money available was claimed from the IDA.

The result of the poor utilisation of funds is that the World Bank has been

progressively reducing its committments to India (see Figure 1). The commitments

were between USS 2500 to 3000 million during 1984-85 to 1988-89- The utilisation

(in all sectors) was only around 61 percent. Thus, the World Bank reduced its

committments to around USS 2000 million to match with the ability of the

3

Government to use the funds.

COMMITMENTS V/S DISBURSEMENTS

f million

National AIDS Control Programme

SI.

No.

Description

1.

IDA Commitment

2.

Grants Released to

the States

3.

4.

1992-93

Amount

Percent

1993-94

(Upto January

1994-10.months)

Amount

Percent

70.0

100

73.0

100

11.43

3.56

16.3

5.1

2.9

0.82

4.0

Expenditures reported

Reimbursement claimed

from IDA

2.35

3.4

N.A.

N.A.

1.1

As a result, according to Dr Anthony Mesham of World Bank, the undisbursed amount has

marginally come down from USS 14 billion 3 years ago to USS 10 billion presently.

Needless to say, in comparison to the overall utilisation the utilisation, in the health sector

was very poor. Taking the life cycle of a typical project at five years, the annual utilisation

should be about 20 percent. Against this, the utilisation in the health sector was around 67 percent and in all sectors it was around 12 percent.

A result of this non-utilisation has been that India has the unique distinction of being the

only country to be mentioned in the Annual Report of World Bank, 1993 where large loans

4

have been cancelled. To quote from the report: "The Bank is working closely with

borrowers to ensure more timely project start-ups and has adopted a more pro-active stance

towards project restructuring, cancellation and closure. This stance, for example, has

resulted in recent, large cancellations of IBRD operations (fifteen projects valued at $ 850

million) and redeployment of IDA funds (eighteen projects valued at S 379 million) in India”

(p 124).

According to Dr Mesham, the major difficulty in disbursements in the health sector was that

the State Government not understood the procedures for claiming reimbursement have. The

World Bank had been dealing with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MHF), which,

in turn, was communicating the procedures to the states, obtaining expenditure statements

and submitting to the Bank. Somehow, the process was not being understood by the States,

leading to poor disbursements. Reportedly, under pressure from the Bank, the Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare has recently agreed that the Bank may lend directly to the states.

THE UN SYSTEM

Two agencies of the UN sysjem having significant presence in the Health Sector are The

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

The UNFPA mainly funds programmes in the area of family planning and welfare. It held

a mid-term review of its programme for India 1991-95 in May 1993 with the Ministry of Health

and FAmily Welfare. According to the report submitted to the MHF for the review, the overall

performance of MHF appears to have been quite reasonable in 1992 with nearly 87 percent

utilisation of the Programme Allocations. However, there still were some projects which had

been lagging behind. The details of some of such projects is given in Table 6.

Table 6

•

UNFPA : Slow Moving Projects

SI.

No.

Programme

Allocation

1992

Actual

Expenditure 1992

Percent

Utilisation

1.

Monitoring Sterilisation

65

43

66

2.

Centres of Excellence

220

83

38

3.

4.

FW Area Project - HP

1935

1326

68

Study Tours

90

18

20

77

49

64

6

1

17

2

67

5.

Population Education

- Higher Education

6.

Programme Development

7.

Women Development

8.

Total Slow Moving

3

2396

1522

63

9.

Total, All Projects

11700

10259

88

Mission

(Haryana)

Although UNFPA assitance gives a better picture, it has to be seen under the backdrop of

reducing committments from the UNFPA. In 1990 the UNFPA allocation for India was US

$16.3 million. In view of the poor utilisation, UNFPA reduced its allocation to $ 11.2 million

5

in 1991 and $ 11.7 million in 1992. Moreover, UNFPA revises its allocations every six months

and provides more money to fast moving projects and takes away from slow moving projects.

IMPLEMENTATION PROBLEMS

While each project has a specific set of problems, there are many problems which are common

to all projects. These are refelcted at various stages such as project documents preparation,

project implementation and mid-course correction. The main prblem areas are given below:

1.

There is a considerable gap between the signing of a project document and its actual

implementation. This gap ranges anywhere betw'een six months to five years.

2.

At the time of implementation, all project components are not given equal importance.

Certain components get more preferene than others.

3.

Projects initiated by a particular person get affected if continuity in leadership is not

available. A new incumbent often would like to substantially or totally change the project

components.

4.

Projects initiated by the centre are often given to the state governments for implementation

whether the states are interested or not. State government preferences do not always

match with Central Government priorities.

5.

Too many projects sponsored by different donor agencies in a particular geographical

area often make it difficult for the state governments to absorb funds and to cope up with

workloads.

6.

Major projects, often measured in terms of budgetary allocations overshadow the minor

projects if taken up in the same state either by the same donor agency or by different donor

agencies.

7.

Inter-sectoral activities which call for coordination between various departments and

agencies often encounter difficuties in implementation. In most cases, it requires

herculean efforts to bring these departments together.

8.

Organisation structures and mechanisms created for speedy implementation of project

components, at times, become major hindrances. Too many committees, lack of clarity

on roles, functions and decision-making authority, and separate officers make the project

activities look different from mainstream activites.

9.

While all major projects have components of personnel to administer the project, posts do

not get filled in because of cumbersome rules, and at times due to blanket ban on

recruitment. What has been agreed at the time of project agreement is often over-ruled

later because of promulgation of general rules applicable to all departments.

10 Flow of financial resources is a major problem. Though budgetary sanctions are accorded

to all activities int he beginning, specific sanctions are required to spend money on each

activity. This results in considerable delay in flow of resources. Implementing agencies in

health and family welfare departments have hardly any authority or flexibility. Given this,

in recent times, state governments and donor agencies have, more often than not, created

flexible mechanisms outside the formal government structures to ensure regular and

timely flow of funds.

Source: UNFPA Mid-term Review Report.

6

Thus, the allocations for slow moving projects are gradually brought in tune with the actual

speed of expenditure. The importance of this fact is that if the utilisation was belter, UNFPA

may have been willing to allocate yet more funds.

The major problem faced by UNFPA was that the money had to often go through five

accounts to reach the actual user. For example, the money for school education project was

paid by UNFPA to the MHF, which paid to Ministry of Fluman Resources, whcih paid to

NCERT, which paid to the Slate Councils of Eduation Research and Training who were to

actually spend the money. The result was that often the State Councils were starved of funds

despite UNFPA having paid to MI IF. On one occasion the retirement of one person at NCERT

and the delays in appointment of the replacement had blocked the process for many months.

UNFPA has also not been able to obtain audited expenditure statements of the monies paid

by it. This was causing difficulty. Since all the money was first going into the Central

Government kitty, it could not be audited by and external' auditor.

In fact, one wonders if there is a need for a nodal ministry. In the above example, MHF came

into the picture only because it was the nodal ministry for UNFPA although the entire project

was being handled by the Education Ministry. The only explanation seems to lie in the fact

that MHF would not like to part with its 'influence' over UNFPA funds.

The result of this situation is that most MCH/FP projects are behind the stipulated time

schedule. UNFPA has suggested that it would like to drop "all projects pending for more

than 2 years”; and it has sought the assistance of MHF “to create a more responsive flow

of financial resources” (p 1-2 of Mid-term Review Report).

The various problems of implementation outlined by the Review are given in the box.

The UNFPA report goes on to mention that “there are several reasons for low expenditure

levels on projects: 1) New projects that are supposed to commence in 1992 could not begin

due to delays in government clearances; 2) Amount of expenditure incurred on on-going

projects was much less than estimated levels due to slow progress in implementation.” Thus,

the situation continues to be bleak if one looks at what could have been achieved by a little

more attention on the part of the Government of India.

The other important UN agency in the Health sector is UNICEF. Unfortunately, UNICEF office

was tight-lipped about discussing the problems. However, Health Ministry sources provided

a statement of the budgets and utilisation for the major UNICEF Scheme—The Expanded

Programme for Immunisation (EPI). UNICEF has an accounting system wherein the

unutilised budget of one year is automatically carried forward and added to the budget for

the next year. Hence, if some money allocated for 1991 was ultimately utilised in 1993, it

would appear in the budget of 1991,1992 as well as 1993- Precisely for this reason, the figures

give a correct picture of the funds available in any particular year whether by way of carry

forwards or fresh allocations.

7

Table 7

UNICEF : Funds Utilisation EPI

SI.No

No.

Year

1.

1991

2.

1992

1993

30,731

1991-93

113,973

3.

4.

Total

Utilisation

Amount

Utilisation

Percent

38,784

18,302

44,458

25,622

47.2

57.6

17,913

61,837

58.3

54.3

Budget

Amount

It will be seen that the utilisation of UNICEF funds has been in the range of 50-60 percent

only.

BI-LATERAL FUNDS

A large part of foreign funds comes through bi-lateral arrangements. The Aid and Accounts

Audit Division of Department of Economic Affairs publishers annual statistics of External

Assistance. The last year for which they are available are 1991-92. The details of projects in

the health sector are given in Table 8. All figures relate to grants, not loans.

The average rate of utilisation for 1991-92 was 7.8 percent for UK, 10.7 percent for Denmark,

24.5 percent for USA, 29.7 percent for Japan, and 64.0 percent for Norway. It must be

metnioned that these percentages have been calculated on the basis of total undisbursed

funds available as at 1.4.1991. This would include the amount to be utilised in subsequent

years. However, since break-ups for the amount budgeted for 1991-92 were not available,

the total amount has been used to calculated the percent utilisation. Nevertheless, they do

give us an overall feel of the situation.

The bi-laterial donor agencies are virtually disgusted with the state of affairs. In the opinion

of one donor, the situation in India was “the worst that I have seen".

The main problem repeated by the donors was that it took a tremendous amount of energy

to get anything done through the Health Ministry. In the words of one donor, the MHF was

the bottleneck between the donor and the state governments, which were the actual user

of the funds. According to him, “the relationship between the MHF and the state

governments is no mystery. The MHF wants to control the funds. The state governments

incur the expenditures and submit statements to the MHF. The Health Ministry consolidates

them and submits to the Donor. The Donor gives money to MHF which, in turn, re-imburses

the state government. The whole process gets stuck in the bureaucracy. We want to release

money to the states directly but the govenment would not let us.”

Then there are problems at the level of sanction also. Here the Department of Economic

Affaris (DEA) of Ministry of Finance comes into the picture. Any foregin assistance proposal

from MHF has to be routed through the DEA. Thus, initiation of a project requires yet another

stage. The state concerned approaches the Donor for funds and prepares a scheme. It sends

to MHF, which sends to DEA for approval. The whole process takes anywhere from 6 months

to five years! This can be seen most visibly in the bi-lateral grants fro USA. Most projects have

been negotiated and re-negotiated for over 3 to 4 years (see Table 8).

8

•

Table 8

Bi-lateral Grants in Health Sector, 1991-92

U.K.

Utilised in

1991-92

years of

Sanction

Amount

Authorised

upto

31.3.92

Amount

Utilised

upto

31.3.91

Amount

Available

in

1991-92'

Amount

Percent

3

4

5

6

7

8

18.0

0.2

7.8

17.9

17.9

1.4

1.4

0.2

7.8

SI.

No.

Scheme

1

2

1.

Orissa Family

welfare II

1990

Sub Total U.K.

18.0

MILLION POUNDS

• U|

I?'"-

■ A

_____________

DENMARK

Utilised in

1991-92

years of

Sanction

Amount

Authorised

upto

31.3.92

Amount

Utilised

upto

31.3.91

Amount

Available

in

1991-92-

Amount

Percent

3

4

5

6

7

8

205.0

92.5

42.5

0.5

0.5

NA

14.8

10.6

4.2

0.0

0.0

Health Care Project

M.P. I&II

NA

250.4

188.0

62.4

13.8

22.1

4.

Health Care

Project T.N., I & II

NA

223.3

152.0

71.3

18.7

26.3

5.

National Programme

for Eradication of

Leprosy

NA

81.5

28.6

52.9

0.0

0.0

Health Care & Family

Welfare Project,

Chandigarh, I & 11

NA

SI.

No.

Scheme

1

2

1.

National Programme for

Control of Blindness

I&II

NA

2

Health Care and

Family Welfare Project,

New Delhi I & II

3.

MILLION D KR.

6.

Sub Total Denmark

11.8

7.2

4.6

0.0

0.0

786.8

478.9

307.9

33.0

10.7

Presumably thisfigure includes amounts to be spent on subsequentyears. However,

since no break-up of amount budgettedfor 1991-92 has been give separately, the

totalfigure of balance amount available has been given.,

9

U.S.A

SI.

No.

Scheme

1

2

1.

Family Planning

Communication &

Marketing Grant

2.

Bio-medical Research

Support

3.

Contraceptive

Development and

hiproductive

Immunology

4.

Child Survival

and Health Support

1985 & 88

1986

1988 & 89

5.

Vaccine ImmunodLignostic Development

6.

Private Voluntary

Organisation for

Health

Sub-Total U.S.A

years of

Sanction

3

Amount

Authorised

upto

31.392

Amount

Utilised

upto

31.3.91

Amount

Available

in

1991-92*

Amount

Percent

4

5

6

7

8

Utilised in

1991-92

MILLION USS

1983

17.5

3.0

14.5

1.2

8.3

1985

1987- 88

9.3

0.9

8.4

0.0

0.0

3.2

0.2

3.0

0.01

0.3

41.1

22.2

18.9

8.0

42.3

1989

4.0

0.3

3.7

0.2

5.4

1987

6.5

0.5

6.0

0.4

6.7

81.6

27.1

40.0

9.81

24.5

Source : External Assistance 1991-92, Aid Accounts and Audit Division, Ministry

of Ftnace.

JAPAN

SI.

No.

Scheme

1

1.

2.

years of

Sanction

Amount

Authorised

upto

31.3.92

Amount

Utilised

upto

31.3.91

Amount

Available

in

1991-92*

Amount

Percent

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Regional Cancer

Centre Madras

Regional Cancer

Centre (Grand Aid)

Sub Total Japan

1988

641.0

609.8

34.2

34.2

100.0

1989

616.0

13.0

603.0

154.8

25.7

1257.0

622.8

637.2

189.0

29.7

10

Utilised in

1991-92

Utilised in

1991-92

years of

Sanction

Amount

Authorised

upto

31.3.92

Amount

Utilised

upto

31.3.91

Amount

Available

in

1991-92-

Amount

Percent

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Family Welfare PP II

Eradication of

Leprosy

Sub Total Norway

NA

NA

215.0

10.0

170.7

2.4

44.3

7.6

33.2

0.0

74.9

0.0

225.0

173.1

51.9

33.2

64.0

03.03.94

SI.

No.

Scheme

1

1.

2.

HGL

\OO

7? <

f

library

ANO

M\ BOCUMcNTATION

> ox

> 'r-

J r".

Chapter 3 : Suggestions

It is too much to expect this quick study to be able to come to any 'conclusions'. However,

this much can be stated that a problem does exist. The main difficulty seems to be that health

is a state subject under the Constitution. Thus, all programmes relating to health have to be

implemented by the state governments, or at least have their positive concrurence and

support. However, the international donor agencies have to primarily deal with the Central

Ministries of Health and Finance. In the words of Mr. R.K. Ahooja, former Jt. Secretary in

Ministry of Health, "the donors have no direct access to the state governments." Thus, "the

states do not understand the procedures.” This was the same remark as made by Dr Anthony

Mesham of the World Bank. The result is that the International Health Division of Ministry

of health is overburdened with gening the communicaton established between the State

governments and donors. The whole system gets slowed down here. The norms are set by

the Central Ministries and the State Governments have no say in it. There is no flexibility

at the state level. Any problem has to be sorted out with the donors only through MHF, and

gets stuck there. One of the donors explicity stated that the problem was that MHF was

unwilling to relinguish its influence and control over the funds.

The second major problem duly emphasised by Mr. Som Nath Som, Advisor (Health)

Planning Commission, was that according to the procedures set by MHF, the State

governments had to first incur an expenditure from their own funds and then seek re

imbursement from the donors. Often the States have had a problem of liquidity. They do

not have the funds to spend initially. Then, due to inadequate understanding of the

procedures often the expected re-imbursement does not take place due to non-adherence

to the norms. This makes the States hesitant to put in their own money. As a result the money

available from the donors does not get utilised.

Dr BbaratJbunjbunwala did his Ph.D in economicsfrom University ofFlorida in

1973- He taught at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore from 1973 to

1979. In this period be lived in a slum for two years and was active in the Trade

Union movement. He has been a free-lance consultant since then. Presently, he is

editing Legal News & Views, a Journal which aims to assist the NGOs.

12

The Voluntary Health Association of Ind ia (VHAI) is a secular, non-profit

federation of over 3000 organisations working in the field of health and

community development. VHAI strives to make health a reality for all,

especially the unreached and the oppressed.

VHAI fulfills these objectives primarily through training and by provid

ing information to the target groups. In support of its objectives, VHAI

also develops and distributes appropriate educational aids to the

organisations serving at the grassroots. Linking up these organisations

through its newsletters and journals also constitutes an important

activity of VHAI.

’

Tong Swasthya Bhavan, 40, Institutional Area

South of IIT, Near Qutab Hotel, New Delhi110016 INDIA

Phones : 652953, 655871, 665018, 668071, 668072

■

Voluntary Health Association of India

.ii. 7 i'k s

VHAI researches into and campaigns on relevant and important health

issues to ensure that a people-oriented health policy is brought about

and effectively implemented. VHAI also works to sensitise the large

public towards a scientific attitude to health.

- Media

2836.pdf

2836.pdf

Position: 1049 (12 views)