IDS BULLETIN Seasonality and Poverty

Item

- Title

- IDS BULLETIN Seasonality and Poverty

- extracted text

-

susstx

Seasonality and Poverty

SUMMARY

Seasonality and Ultrapoverty

Michael Lipton

The ultra-poor — a group of people who eat below 80 per cent of

(heir energy requirements despite spending at least 80 per cent of

income on food — are most vulnerable to seasonal fluctuations in

food supply and wage employment, and seasonally induced

nutrition and health risks Lowenergy intakes are linked with greater

seasonal instability, and seasonal fluctuations in employment are

also greatest for the ultra-poor. The poor in sub-Saharan Africa are

likely to suffer more in these respects than their Asian counterparts

because of their less developed irrigation and transport systems.

This influences the cropping pattern of African farmers. As

population pressure intensifies in Africa, public spending in support

of the farm sector is required to reduce the bad season impact on the

ultra-poor. Of particular importance are policies to support

migrants, provide rural credit and to manage common property

resources.

Women and Seasonality: Coping with Crisis and Calamity

Janice Jiggins

This article explores the contribution of female production, labour

and domestic domain services to the management of seasonal

stress, crisis and calamity, under the headings; switching tasks and

responsibilities ascribed by gender; diversifying household income

sources', changing the intensity and mix of multiple occupations:

household gardening and common property resources, food

processing, preservation and preparation; social organisation; gift

giving. It offersan analysis of adversity and calamity which pinpoints

the resilience of networks of female-headed households and raises

new questions concerning risk preference, probability assessment

and the valuation of female labour time.

Food Shortages and Seasonality in WoDaaBe Communities In Niger

Cynthia White

Data on WoDaaBe nomadic pastoralists in central Niger demon

strate that seasonality, through a coincidence of stress factors in the

dry and transition seasons, clearly does reinforce poverty in this

group. Although important, dry season hardship is merely a

symptom of more crucial political ano economic factors affecting

the WoDaaBe economy.

Household Food Strategies in Response to Seasonality and Famine

Richard Longhurst

Rural families have a range of strategies with which to cope with

seasonal and inter-seasonal fluctuations in food supply For landed

households the most important seasonal strategies include choice

of cropping patterns to spread risks involving mixed cropping.

cultivation of secondary crops, particularly root crops Other

seasonal coping mechanisms include sale of small assets and

livestock, drawing down of stored product and cultivation of

supportive social relationships. Off-farm income earning work

provides one of the best buffers against seasonal stress. If a bad

season stretches into a prolonged drought, or if there is a sudden

drop in purchasing power, then these activities are further

intensified, but families are forced into divesting resources; selling

productive assets, constricting food intake, and migration. If

investment in rural areas and food production recognised these

strategies the severe impact of famine could be avoided

Biomass, Man and Seasonality in the Tropics

Colin Leakey

Agricultural research linked to government policies to increase the

availability of biomass to provide food, forage and medicine requires

a re-think. In particular, by ignoring trees and gathered foods.

policies have not met demands for food in arid areas, and an

emphasis on increasing production per unit area has accentuated

seasonality of production by favouring selection of crop species

requiring longer periods of moisture availability. The use of plants

for medicines, stimulants and control of fertility also has important

seasonal effects, but has received minimal attention to date. The

classification of Raunkiaer, who distinguished plants on the basis of

their modes of protection and size of buds, enables an analysis

related to their effective use of moisture and temperature, so

providing a framework for linking the seasonal production of

biomass to human needs

Trees, Seasons and the Poor

Robert Chambers and Richard Longhurst

Trees play a significant role in poor people's seasonal livelihoods:

this has been a neglected subject due to interlocking biases against

understanding how the poor secure their incomes, and ignorance of

the multipurpose role of trees. Trees play an important seasonal role

through their physical characteristics: deep rooting with access to

moisture and nutrients year round Accumulation of stocks in the

form of wood and various beneficial environmental effects. Trees

seasonally stabilise, protect and support the livelihoods of the rural

poor and policies can be designed which reinforce this important

role

Seasonality In a Savanna District of Ghana — Perceptions of Women

and Health Workers

Gill Gordon

Households in a coastal district of Ghana aim to maintain a constant

supply of food by farming, fishing and trading. Trading in processed

foods is highly competitive in the rainy season. Many families

respond to adverse farming or trading conditions by temporary

migration. Seasonal stress reduces women's ability to care for their

children and make use of health services Village health workers

perceive their farm work to be of higher priority than their health

tasks at a time when demand for their services is greatest. This article

suggests measures to reduce the impact of seasonal stress on

households and health workers.

Access to Food, Dry Season Strategies and Household Size

amongst the Bambara of Central Mali

Camilla Toulmin

This article describes the seasonal variation in production and

household organisation in a Sahelian farming village. With the

loosening of domestic responsibilities, once tne harvest is stored.

the dry season offers a range of income-earning activities for the

individual to pursue. Those from gram surplus households can use

this period to build up private sources of wealth. Grain deficit

households must use dry season incomes to help them get through

the next farming season. This differential capacity to make use of the

dry season accentuates differences in household size and wealth

Seasonality and Poverty: Implications for Policy and Research

Richard Longhurst, Robert Chambers and Jeremy Swilt

There is great diversity in the way different groups of people are

affected by seasonality and cope with it. Greater understanding of

this diversity is required if policy and project interventions are to

strengthen the position of poor rural people. The damaging periods

of time can sometimes be very short, regularly crippling families in

their efforts to accumulate resources and protect their health. In

sub-Saharan Africa seasonality is clearly a major dimension of

adverse economic change, of declining food availability and

increasing instability in food supply. As a result seasonality has

become a more significant point of entry for analysis and action.

Policies are needed which strengthen seasonal coping mechanisms.

and reflect a decentralised and differentiated approach in timing and

targetting on the most vulnerable groups.

RESUME

Les Variations Salsonnleres et I'Ultra-pauvrete

Michael Lipton

Les ultra-pauvres — un groupe consommant moins de 80% de ses

besoins en Energie, bien que 80% de ses revenus soient consacres a

la nourriture — sont les plus vulnerables a la fluctuation saisonniere

des salaires. de I'approvisionnement en nourriture et aux risques de

same et de nutrition que cette fluctuation engendre. L'insuffisance

des rations alimentaires est liee a une plus grande instability

saisonniere. et la fluctuation saisonniere de I'emploi est plus

importante chez I’ultra-pauvre. Dans ce sens, le pauvre en Afrique

Sub-saharienne souflre probablement plus que son homologue

asiatique car ses systemes d'irrigation et de transport sont moins

developpes. Ceci influence les habitudes de culture des fermiers

africains. Comme la pression de la population s'intensifie en Afrique.

il devient necessaire d'allouer des fonds publics en aide au secteur

agricole pour reduire I'effet de la mauvaise saison sur les ultrapauvres. Des mesures en aide aux migrants, favorisant le

debloquement de credits pour le secteur rural et ('administration des

resources communautaires sont done d'une importance toute

particuliere.

Les Femmes et les Variations Saisonnidres: Falre face aux Crises et

aux Catamites

Janice Jiggins

Sous les titres suivants. cet article explore la contribution que les

femmes apportent a I'organisation de la tension saisonniere. aux

crises et aux desastres, par leur production, leur labeur et leurs

services dans le domaine domestique; changement dans les travaux

et les responsabilites assignes par le genre; diversifier les sources de

revenu du menage; changer ('intensity et (association oes

occupations multiples; culture du jardin familial et resources

communautaires; traitement, conservation et preparation de la

nournture; organisation sociale, echange de dons II offre une

analyse des concepts d'adversile et de calamity qui cerne la

resistance des reseaux de manages ou la femme est chef de famille

et soulevent de nouvelles questions concernant les priorites vis a vis

des risques a prendre, les calculs de probability et revaluation du

temps de travail de la femme

P^nurie de Nourriture et Variations Saisonnieres dans les

Communautes WoDaaBe au Niger

Cynthia White

Une collection de donnyes sur les eleveurs nomades WoDaaBe dans

le centre du Niger nous montre que les variations saisonnieres par la

coincidence de facteurs de tension durant la saison seche et les

saisons de transition, renforcent trds clairement le niveau de

pauvretc de ce groupe Bien qu'importante. la privation causee par la

saison seche n'est qu'un symptome d'elements economiques et

politiques plus importants qui affectent I'economie des WoDaaBe

Strategies des Families pour la Production de Nourriture en

Reponse aux Variations Saisonniferes et a la Famine

Richard Longhurst

Les families rurales ont toute une syrie de strategies qui les aident a

faire ux fluctuations saisonnieres et mter-salsonmeres de l approvisionnement en nourriture Pour les menages proprietaires terriens.

afin de diminuer les risques. les strategies saisonnieres les plus

importantes comprennent le choix de I'echelonnement des recoltes

necessitant une culture mixte. la culture de plantes secondaires en

particulier de plantes a racmes. D autres mecamsmes saisonmers

les aident a faire face au probleme. tels la venle de petits biens et de

batail, la limitation des produits emmagasines el I'entretien de

relations sociales de soutien mutuel. Un travail salarie procurant un

revenu independent de celui de la ferme esl une des meilleures

garantie contre les tensions saisonnieres. Si une mauvaise saison se

prolonge pour devonir une secheresse ou qu'une baisse soudaine de

pouvoir d'achat se produise. alors ces activites s'intensifient encore

plus, mais les families sont obligees d'avoir recours a des moyens

dypreciatifs: vente de biens productifs. reduction des rations de

nourriture. migration. Si les investissements dans les secteurs

ruraux et de la production ahmentaire tenaient compte de ces

strategies. I'effet desastreux de la famine pourrait etre evite.

Biomasse, I'Homme et les Variations Saisonnieres sous les Tropiques

Cotin Leakey

II est necessaire de repenser la recherche agronomique associee

aux mesures gouvernementales visant a ameliorer (accessibility a la

masse biologique afin de fournir de la nourriture. du fourrage el oes

medicaments. En particulier. ces mesures en ne tenant pas compte

des arbres et de la nourriture rycoltee par la cueillette. n'ont pas

satisfait les besoins alimentaires des regions andes. et la

concentration des efforts sur I'augmenlation du taux de production

a I'unite a accentuy les variations saisonnieres de la production en

favorisant la selection d'especes nycessitant de plus longues

periodes d'humidity. L'ultilisation de plantes pour la fabrication de

remedes. de stimulants et pour le controle de la fertility a aussi des

effets saisonniers importants, auxquels. jusqu’a present, il n'a ete

porte qu'un minimum d'attention La classification de Raunkiaer. qui

eta blit une distinction entre les dilferentes plantes en utilisant leurs

modes de protection et la dimension de leurs bourgeons rend

possible une analyse basee sur leur besom effectif en humidite et

temperature, nous donnant ainsi un cadre de travail qui nous permet

detablir le lien entre les besoins humains et la production

saisonniere de masse biologique.

Les Arbes. les Saisons et le Pauvre

Roobert Chamber et Richard Longhurst

Les arbres jouent un rdle considerable dans les moyens de

subsistence saisonniers des populations pauvres- un sujet neglige a

cause de connexions complexes entre differents prejuges qui

empechent de comprendre la maniere dont le pauvre assure ses

revenus. et (’ignorance concernant les roles et usages multiples des

arbres De part leurs caracteristiques physiques, les arbres jouent un

role saisonmer important des racines profondes qui ont acces a

I'humidite et aux substances nutritives toute I'annye. une saison ou

ils produisent des fruits et une ou ils ensemencent des graines qui

s'etendent sur de longues periodes. ils contribuent a une

accumulation de stocks en bois. et ont bien d'autres effets

benefiques sur I'environement. Les arbres. au fil des saisons.

stabilised, protectent et soutiennent les moyens de subsistence des

populations rurales pauvres et des mesures peuvent etre prises de

mamere a renforcer ce role important.

Variations Saisonnieres dans une Region de Savane au Ghana —

Remarques faites par des Femmes et des Aides medicaux

Gill Gordon

Les families dans une region cohere du Ghana s'efforcent de

maintemr un approvisionnement constant en nourriture. par

('agriculture, la peche et le commerce. Le commerce d'aliments

transformes est extrymement competitif durant la saison des pluies

En reponse a de mauvaises conditions pour ('agriculture ou le

commerce beaucoup de families choisissent une migration

temporaire Pour les femmes, la tension saisonniere diminue leur

aptitude a prendre soin de leurs enfants et utiliser les services de

sante Dans les villages a une epoque ou la demande pour leurs

services atteint son maximum, les aides medicaux ont remarquy que

le travail de la ferme a priorite sur leurs devoirs concernant la sante

Cet article suggere des mesures pour reduire I'effet de la tension

saisonniere sur les families et les aides mydicaux

Acces a la Nourriture, Strategies de la Saison Seche et Dimension de

la Famille chez les Bambara dans le centre du Mall

Camilla Toulmin

Cet article illustre la variation saisonniere de la production el de

I'organisation de la famille dans un village fermier du Sahel Avec le

relachement aes responsabilites domestiques. une fois la recolte

engrangee la saison seche offre a I'individu un choix d'activites

salariees. Les membres d un menage ayant un surplus en gram.

peuvent mettre a profit cette periode pour accumuler des biens

Ceux qui ont un deficit en gram ooivent utiliser les revenus de la

saison seche dans I'attente de la prochaine saison agricole. Cette

inegalite dans leur aptitude a utiliser la saison seche accentue les

differences dans la dimension et la fortune des menages.

Variations Saisonnieres et Pauvrety: Consequences pour la

Recherde et la Politique a sulvre

Richard Longhurst. Robert Chambers et Jeremy Swift

II y a une grande diversite dans la maniere dont differents groupes

sont affectes par les variations saisonnieres et la maniere a laquelle

ils y font face II nous faut attemdre un plus haut degre de

comprehension de la nature de cette diversity si I'on veut que des

mesures et projets d intervention renforcent la position des

populations rurales pauvres Les periodes nefastes peuvent

quelquefois etre de tres courte duree, mais endommagcnt

regulierement les efforts portes par les families a ('accumulation de

biens et la protection de leur sante En Afrique sub-saharienne. il est

evident que les variations saisonnieres sont une dimension majeure

d'un changement economique defavorable. dun declin de la

disponibihte de la nourriture et d'une augmentation dans I'instabilile

de l approvisionnemenl. En consequence, les variations saisonnieres

sont devenues un point de depart plus significatiI pour une analyse

et une ligne d'action. II faut done prendre des mesures qui renforcent

les mecanismes saisonniers de defense et refletent une approche

decentrahsee et differenciee dans le temps ayant pour but les

groupes les plus vulnerables

RESUMEN

Estacionalidad y ultrapobreza

Michael Lipton

Los ultrapobres — un grupo de personas que consumen menos del

80% de sus requenmientos energeticos. pese a que gastan al menos

80% de su ingreso en alimentos — son los mis vulnerables a las

fluctuaciones estacionales de la oferta de alimentos y del empleo

remunerado. asi como a los riesgos sobre la nutricidn y la salud

inducidos por la estacionalidad. El bajo consumo energytico esta

vinculado a la mayor inestabilidad estacional y ademas las

fluctuaciones estacionales del empleo tambien son mayores para

los ultrapobres. Los pobres del subsahara africano esian expuestos

a sufrir mas que sus contrapartes asiaticos, a raiz del menor

desarrollo desus sistemas de riego y transporie Este hecho afecta el

Editorial

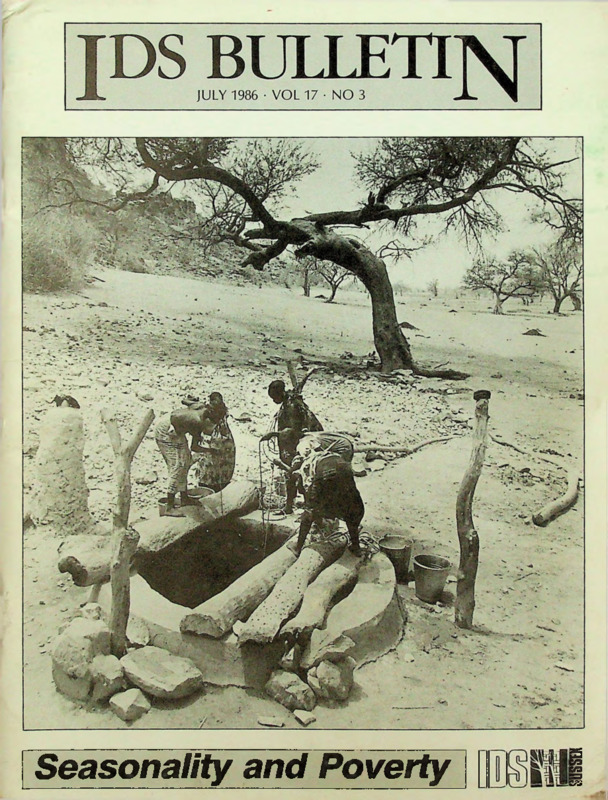

Rural poverty in developing tropical countries has a

seasonal dimension. There is a simultaneous prevalence

of sickness, malnutrition, indebtedness, hard work,

discomfort and poor food availability at certain times

of the year, usually during the rains. This period

before harvest — ‘the hungry season' — is one of

considerable stress for rural people, exacerbating their

poverty. Poor people are less able to cope with this

regular period of stress than rich people, who can

usually exploit it to their benefit. The difficulties and

stress experienced on a seasonal basis are, of course,

anticipated by poor rural people: they are a regular

event to be navigated each year. There are different

ways of coping — of moving resources around — in

ways that relate to productive activities and social and

demographic mechanisms. Some of these mechanisms

are described in this Bulletin. In calling this issue

‘Seasonality and Poverty’, the focus is on how

seasonality affects poor people, how they respond to it

and how development can assist them in the face of

these stresses.1

The seasonal problems of rural people vary between

different environments. They relate to the nature of

the local ecology and natural rhythms of plant and

animal growth, local production and income

generating activities and cultural patterns. The

reaction of individuals and communities in pastoral

areas will vary compared to those of, for example,

communities of cultivators. The overall wealth of a

community or a family could lift them above or

depress them below the critical level of livelihood

which determines whether seasonal stress leads to*

The papers in this Bulletin are des eloped from an IDS conference

held al Stafford House. Hassocks, Sussex on 13-15 February. I9S5.

and organised by Robert Chambers. Richard Longhursl and

Jeremy Swift. Acknowledgement is due to those attending the

workshop for contributions to the discussion and conclusions. They

were Caroline Allison. David Butcher. Robert Chambers. Alison

Evans, Catharine Geissler. Gill Gordon, Patrick Hardcastle Ccd

Hesse, Janice Jiggins. Colin Leakey, Michael Lipton. Richard

Longhursl. Penelope Neslel, Clare Oxby, Claudia Pcndred. Sara

Randall, David Salm, Jeremy Swift. Camilla Toulmm and Cynthia

White

IDS Buttenn. 19X6 >ul I7no.l Institute orDeidupnwiil Smdio. Sussex

constraints, preventing families from meeting sub

sistence needs without some loss of function. The

many and varied environments in which seasonal

influences operate are also described in the Bulletin.

Seasonal stresses are not the only contingency faced by

rural people and although regular, may be less severe

than the irregular unanticipated problems created by

variations in food and employment availability

between, rather than within years. Two or three poor

years of food production can often lead to famines, as

seen recently in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. A third

even more spasmodic and random contingency can be

that which strikes individual families tn the form of a

sudden death, an accident incapacitating working

members or a huge, although generally expected,

expenditure such as for a wedding or birth naming

ceremony. When these contingencies overlap, as they

can do for families at a certain stage in its life cycle,

inhabiting areas that are drought prone, then the

family is likely to be driven into deep impoverishment.

The context in which seasonal factors influence

economic development is clearly as important as the

nature of those seasonal forces. The contingencies

described above broaden seasonality beyond a narrow

definition and place it within this wider context. The

way in which people respond to stress and its corollary

— how development and policy can strengthen

people’s ability to withstand stress — requires this

wider definition. This suggests three levels of analysis

to seasonal problems, especially within conditions

seen today in sub-Saharan Africa. These involve the

examination of relationships between first, different

types of seasonal patterns and the importance of

particular types of significant elements; second,

regular patterns and irregular bad years which throw

regular seasons out of gear, and third, regular seasonal

fluctuations and those underlying the economy such

as long-term declines in food production, availability

of able-bodied workers in rural areas, degradation of

the environment, erosion of common property

resources and so on

The need to develop the links between seasonality per

sc and the other processes of impoverishment has been

reinforced by the experience of policy-makers and

researchers since the conference on Seasonality held at

IDS in 1978 pulled together case studies and focused

thinking more intensively on seasonal issues

[Chambers, Longhurst and Pacey 1981]. Policy

makers do regard seasonal phenomena and the inter

relationships between them as too important to

ignore, and believe that resources applied to

alleviating seasonal hardship would bring considerable

benefits. The argument for seasonality-related inter

ventions has often revolved around one of cost

effectiveness: that resources applied at specific times

of year will be more effective than strategies that exist

all year round, and that raising people above the

seasonal threshold will remove a constraint that will

encourage self sustaining growth

In proposing this argument it has sometimes been

difficult to see how interventions could be successfully

timed — switched on and switched off — in locations

where the administration of programmes and projects

is always difficult and where withdrawing services and

resources would be unacceptable to all concerned.

Some interventions of this type are feasible and

include selective use of public works, services related

to specific farming operations and timing of educat ion

services. But generally the subject now needs to be

approached from the point of view of influencing

existing policies by seeking to incorporate an element

that will cope with seasonal stress — by spreading it

out, reducing it or by strengthening buffers that exist

to counter its worst effects. This approach — to

‘season proof development policy — inevitably leads

into more demanding research and policy territory.

but avoids the danger of relegating seasonally to an

interesting but intractable phenomenon.

Three themes in the Bulletin appear of importance to

the editor, with no apologies made for their

obviousness. The first is that already mentioned: poor

rural people have means of coping — up to a point —

with stress from expected seasonal events and

contingencies. The nature of these individual and

household level strategies is mentioned or described in

detail for different parts of the world in nearly all of

the articles in the Bulletin. This frequency of

examination of such strategies is important because

policies should build on what people do already if

poverty — seasonal or general — is to be reduced.

Second, the ownership of assets is an important means

of remaining independent of seasonal stress. Their sale

(or mortgaging) is a major instrument used by people

to cope but in so doing they run the severe risk of

becoming poorer as a result. Asset sale leads to further

accentuation of the unequal distribution of resources.

2

What assets are important is obvious in most cases,

less so in a few others. In physical form, they include

land, livestock, crops in store, dung, trees, household

implements and jewellery; social assets include

membership of occupational groups and foodsharing

networks. People make use of other resources by

diversifying income sources, often by intensive use of

natural resources. The wide range of uses made by

people of plants, trees, livestock and other animals is

evident in several articles. The natural environment

provides many seasonal buffers. Conservation of

natural resources and measures to reconstitute assets

after sale — or better to avoid sale in the first place

— are important.

Third, to counter seasonal poverty we must continue

to take a firmly interdisciplinary line and to exploit the

linkages that exist between our knowledge of natural

resources, economic phenomena and social relation

ships. Rural people look at seasons in a holistic

manner and so there is no reason why professional

outsiders should not do the same.

The bias in the Bulletin is towards articles that refer to

sub-Saharan Africa, but many carry important

implications for development in other parts of the

world, Michael Lipton, for example, reviews his

research on the poor and ultra poor from a seasonal

perspective and shows that reaction to seasonality is

one of many variables which distinguishes these two

groups. Differences exist in labour force behaviour,

demographic structure and asset and land character

istics. The ultra poor do have more unstable diets

seasonally than their poor counterparts; in terms of

labour supply, fluctuations are greatest for the poor

and the wage rate falls and fluctuates in a most

damaging way for them. Janice Jiggins examines the

means whereby women cope with seasonality,

reminding us that there arc considerable differences

within households in terms of suffering from

seasonality and response to it. Experience suggests

that harmful effects are often handed on from men to

women. Attention is drawn to the resilience of

women's social networks.

The two studies from the Sahel, by Camilla Toulmin

among the Bambara of Central Mali and Cynthia

White on the WoDaaBc in Niger examine strategics

adopted by those pastoral communities in response to

seasonality. Toulmin emphasises the importance of

off-farm income sources and also shows how lai ger

households are more able to withstand the negative

effects of seasonality. White shows how large-scale

animal losses by families in bad years used to be made

up, but new forms of development have ma e

pastoralists more vulnerable. As a result permanent

impoverishment can follow but policies cou

e

designed to mitigate this. Richard Longhurst reviews

the household food security strategies adopted by

households, with particular reference to northern

Nigeria. Such strategies include crop diversification

and mixed cropping approaches, the building up of

stores such as body fat, small stocks, and grain, short

or long-term migration, and the development of social

contracts between families and communities. The way

in which these seasonal strategies are extended in the

face of famine conditions is shown for other parts of

the world, including Rajasthan in India.

The research efforts of natural scientists often ignore

seasonal factors. The crops, trees and agricultural

systems that arc encouraged often do not help people

in meeting seasonal food supplies. Colin Leakey

proposes a revival of thinking along the lines of life

forms in relation to adapting to different climates and

hence seasonal production of biomass. On the same

theme Chambers and Longhurst show how trees have

been ignored as important seasonal buffers for the

poor: as sources of food, forage and incomes. Yet it is

clear that they play essential roles in alleviating

seasonal hardships.

The extent of migration as another seasonal buffer is

described in several articles. Gill Gordon’s case study

from Ghana shows the impact of migration on child

nutrition and health which previous work has shown

to be seriously affected by seasonal changes. She

makes suggestions for primary health care measures

which can provide for better child health in the wet

season.

The final article on the implications of seasonal factors

for research and policy indicates the need to think

carefully about location and target groups. Seasonality

needs to be integrated into development policy, but a

fair amount of‘fine tuning’ will be required so that

people do not become improverished either by

seasonal influences or by the very policies that are

designed to help them.

R.L.

Reference

Chambers, R., R. Longhurst and A. Pacey (eds.). 1981,

Seasonal Dimensions to Rural Poverty, Frances Pinter.

London

3

Seasonality and Ultrapoverty

Michael Lipton

I

The Distinction between Poor and

Ultra-poor

Ultra-poor people are those who live in ultra-poor

households. These are households with so little

income per consumption unit that — if they adopt

spending patterns (both among foods and as between

them and non-foods) typical of their household size,

composition and income — they are in a typical week

able to eat so little food as to be a significant risk of not

meeting their dietary energy requirement. In yearround or seasonally-spaced surveys, ultra-poor

households, as a proportion of all households in any

group, can be estimated by finding the proportion who

follow the ‘two 80 per cent rule’: i.e. the proportion

eating below 80 per cent of FAO/WHO (1973) weightadjusted dietary energy requirements, despite spending

at least 80 per cent of income on food. Although for

most low-income countries only 2-5 per cent of

persons, in typical surveys not carried out in acute

famines, either suffer from grade III anthropometry or

fall into severely undernourished groups [Bengoa and

Donoso 1974; Keller and Fillmore 1983] — and

although it is only severe undernourishment that is

linked to functional impairment [Lipton 1983] —

many more people are at risk of falling into such

groups if bad life events, years, and/orseasons overlap

or coincide. For most low-income countries, 10-20 per

cent of people appear to fall into these ultra-poor

groups, i.e. to follow the ‘two 80 per cent’ rule at any

given moment of survey; such people, and especially

their children, would be at quite substantial risk of

descending into the severely undernourished 2-5 per

cent, if their ultra-poverty were long sustained.

ultra-poor have sharply higher child/adult ratios; and

are especially likely to be landless, or (in semi-arid

areas) to operate below five acres or so. The ultra-poor

also differ in certain labour-market characteristics.

Although, even among the poor, lower income

induces higher participation in work, this does not

work among the ultra-poor, perhaps because they are

too often hungry or ill. Also the ultra-poor, being

more often dependent on casual labour than are other

groups, show higher unemployment — but the places,

years and seasons of substantially higher unemploy

ment feature only slight reductions in labour supply

(participation), and therefore somewhat lower real

wage-rates [Lipton 1983a, 1983b, 1983c, 1985b].

If the ultra-poor are at much greater risk, especially of

lasting harm to under-fives, from undernutrition —

and if their conditions make a normal response to

investments or incentives, e.g. via raised workforce

participation, specially difficult, and appear to

mandate a ‘food first' approach — then the separate

identification of these ultra-poor households is crucial

for the success of targeted policies against poverty.

For example, in Kenya, areas with only slightly above

average incidence of poor people have, much greater

measured severity of poverty [Greer and Thorbecke

1986], probably indicating a much greater proportion

of ultra-poor (among the poor as a whole) than in

other areas. These very poor areas, at least a priori,

appear likely to be risky and unirrigated; the effects of

seasonality, in such areas especially, upon the ultra

poor therefore merits close attention.

II

There are quite sharp turning points in food behaviour

[Rao 1981; Lipton 1983a, 1985a; Edirisinghe and

Poleman 1983J as between the ultra-poor, who follow

the ‘two 80 per cent’ rule, and everybody else,

including the moderately poor. Only the ultra-poor

appear to maintain the ratio of food outlay — and

even of outlay on coarse, low-cost energy sources — to

income, when they become a little better off. Also the

tos Bulletin. I9S6. vol 17 no 3. Inslilulc of Development Studiev. Suvsee

4

Seasonal Differentiation

Very interesting inferences arc suggested by Dr.

Emmy Simmons’s work on three villages in northern

Nigeria [Lipton 1983a:42j. Non-poor households

thereshow no relationship of calories per consumption

unit to seasonal instability. Those with very low

income per consumption unit — who normally

average below 2,200 kcal per consumption unit per

day over the year — show some tendency to suffer

from greater seasonal variation as average intake

declines. For those who are at slight risk of

undernutrition, with intakes ofdictary energy between

2,200 and 2,700 kcal daily, this intake is very weakly

correlated with income per consumption unit; they

also show a strong negative link between low intake

and seasonal instability.

This suggests that the severity of nutrition risk among

the ultra-poor is linked to both hunger and seasonal

instability. However, it also suggests that the apparent

degree and indeed presence of caloric inadequacy

among moderately poor people — who seem at first

glance to have nutritionally borderline intakes of

calories — is really due largely to

choices,

corresponding to differences in requirements, rather

than to severe hunger (which one would expect to be

income-linked in its intensity within the group

counted as being at slight risk) or to average yearround income. The capacity to keep out of ultra

poverty may partly depend on adjustment mechanisms

which permit persons within a group, who have

relatively low average of intake to requirements, to

adjust more effectively in seasons when that intake

declines, because of falling intakes, rising requirements

or both. Such adjustment seems to work for the group

of persons at slight risk of undernutrition, but not for

the group at high risk, as the above relationships

indicate. Those at high risk overlap fairly closely, in

these northern Nigerian villages, with those following

the ‘two 80 percent rule’. A related finding in Matlab,

Bangladesh, is that landless mothers showed both

lower average dietary energy intake and greater

seasonal fluctuation than did mothers with land

[Chambers, Longhurst and Pacey 1981:59J.

What of seasonality in labour income, the largest part

of most poor people’s incomes? Age- and sex-specific

participation rates, real wage-rates, and unemployment

all tend to fluctuate seasonally, and to do so most

seriously for casual workers, females, and the ultra

poor. In the Indian National Sample Survey in 197778, adult female participation rates fell nine percent in

rural areas, but six per cent in urban areas, from the

July-September, 1977, seasonal peak to the AprilJune, 1978, trough; adult male rates fell by only

three per cent and one per cent respectively. These

comparative patterns are confirmed by State and

village data, especially for casual workers [Lipton

1983b],

There are interactions between seasonal fluctuations

in participation rates and in employment. The latter

are also worst for the poorest people, since these are

residual workers; in slack seasons, small farmers can

adequately supply their labour requirements with

family workers, and tend to lay off casual (landless)

employees first — especially women — so as to

minimise search and supervision costs of labour.

(Such employees are also likeliest to be under

nourished, and hence toshow low labour-productivity,

in the slack season.) In the 18 poorest households in

four villages in Gujarat, adult-days in the workforce,

as a proportion of all adult-days, fell from 38 per cent

(peak) to 32 per cent (trough); in the best-off eight

households in these villages, all with no participating

female workers, the corresponding proportions of

adult-days remained steady, at 43-45 per cent, from

peak to trough [Lipton 1983b:35]. These patterns are

broadly confirmed in northern Nigerian villages.

The policy implications, tn respect of building up

slack-season female employment (for example with

public works schemes), require caution. We find a

serious slow-down in weight gain, among children

aged less than 18 months, in the slack season in Shubh

Kumar’s study in Kerala, India — but this slow-down

happens only among children whose mothers are in

the workforce but outside the home enterprise, i.e. the

poorest, who must rely on casual employment rather

than self-employment [Kumar 1977], Indeed, extra

female income appears to assist slack-season child

nutrition only if earned in the family enterprise

[Kumar 1977:33],

Due to ‘disguises’ such as slack-season expansion of

cattle care and domestic work, unemployment

fluctuations are understated even in carefully collected

village-level data. However such fluctuations remain

significant, and affect the poorest worst, partly

because — as we have seen — in slack seasons

employees from poor households are ‘crowded out’ by

the self-employed on small-to-medium family farms.

This also happens in bad years; in the 1974-75

drought, in six villages of Gujarat, there was a fall of

55 per cent in family labour use from the previous

year’s level, but of88 percent in casual labour [Lipton

1983b:57]. However, generally, slack-season labour

supply (as measured by the workforce participation

rate) falls less than demand (as measured by the

proportion of participants finding employment), so

that real wage-rates fall alongside both (given that the

elasticity of labour supply is not much below that of

labour demand). Casual labourers, the most likely to

be in ultra-poor households, tend to experience most

acutely this seasonal conjunction of low employment,

participation, and wage-rate.

What compensatory seasonal policies might exist?

Irrigation, and seasonal compensatory employment

schemes like Maharashtra’s Employment Guarantee

Scheme, often appear to raise employed time most for

women, casual workers, and people from low statusgroups [Lipton 1983b:84-5]. Also, price compensation

may be possible. Matlab data show rice prices highest,

and household cereal stocks lowest, when seasonal

5

wage-rates and employment arc least, and this is

confirmed for Bangladesh [Chambers. Longhurst and

Pacey 1981:55. 89-90]. Modern varieties of cereals arc

often associated with some declines in the seasonal

variability of outputs, because they often do best in

irrigated conditions outside the main (rainy) cropping

season. The resulting price stabilisation across seasons

(which can be supplemented by public food grain

releases in seasons of scarcity, if output growth due to

modern varieties has permitted stockbuilding, as in

India) can reduce seasonal vulnerability for the poor

— which helps them even in parts of the country where

the modern varieties have not prospered, but can be

purchased, at less inflated prices than previously, in

slack seasons or bad years.

Ill

Is Sub-Saharan Africa Different?

SSA generally has more extreme seasonality, but less

inequality among the rural poor, than other

developing areas. Seasonality is generally more

extreme than in Asia in comparable semi-arid tropical

zones, partly because there is less irrigation in SSA,

partly because its porous, sandy soils retain less

moisture. Offsetting this, the tropical rainforests of

SSA may suffer from even less seasonality than

elsewhere, because these are in general less exploited,

at least than their Asian counterparts — and larger

proportions of rural people depend on rainforest

cultivation in Africa than elsewhere; but population

growth and shortening fallows render this compen

sation less and less important as time goes by.

Everywhere, water control seems to be less in Africa —

below three per cent of crop land is irrigated, as

against over 30 per cent in Asia. Moreover long

distances and bad transport systems impede seasonal

corrections by way of movements of inter-regional

(price-compensating) grain, and even of labour. At

least since 1960, experience suggests that African

climates are less predictable, more prone to greater

harshness in bad years, and more liable to successive

bad years, than Asian climates. All this reinforces the

harm done by a given degree of seasonal instability.

Moreover, in much of SSA, seasonal (and other)

variations impinge more directly on poor people than

is the case in South Asia, because a larger proportion

of poor people retain usufructuary rights over

cultivated land, and fewer have non-agricultural

employment income. Furthermore, tribal tenure

rights deny poor African farmers the ‘last resort’ of

their Asian counterparts in really bad times, vfz.

mortgage. For all these reasons it is not surprising that

African smallholders are much more prone to use

intercropping to reduce risks than are Asian

smallholders, and also to select crops with low

seasonal specificity (roots and tubers in many cases),

or low vulnerability to moisture stress (millet.

sorghum), as compared with their Asian counterparts

6

who try to select wheat or rice as main crops, soil and

water permitting.

However, population growth in sub-Saharan Africa

is eroding many of the differences — favourable and

unfavourable — between its regions and similar ones

in Asia. Slash-and-burn cultivation is less and less

possible. A growing proportion of rural people

comprises (a) landless or near-landless labourers,

residual employees if in agriculture and hence

especially vulnerable to seasonal and other fluctuations

in the demand for labour: (b) farmers with individual

claims on land rights, able to sell or mortgage land in

time of stress. Crop-mixes are shifting (with

urbanisation, food aid. and research biases) towards

maize, rice and wheat, with more specific dated water

requirements, and therefore more seasonal vulner

ability. than the older crops and mixed-cropping

systems.

As Africa's person/land ratio gets closer to Asia’s, the

’Africa-damaging’ differences in respect of vulner

ability to seasonal stress should also be reduced. But

the latter reduction requires public spending in

support of the farm sector, in response to the new

factor ratios. Such spending is constrained by urban

bias much more extreme than in Asia; by severe

shortages of funds for recurrent public outlays', and by

foreign and other pressures towards ‘price purist',

expenditure-reducing public-sector policies. Hence

there is rather little spending on the water

management. or even on the improvement of intrarural road systems, that might reduce seasonal

vulnerability in Africa.

Bad seasonal impacts on poor people, like other ‘agro

health’ issues, urgently need research on how to adapt

responses to rapidly rising person/land ratios. What

are the counter-seasonal options in the context of a

continent-wide shift from area-expanding to yield

expanding technology? The latter, in South Asia, has

actually increased the coefficient of variation of yearly

food output at national levels, but this is due to the

concentration of (rising) output in a few nearby areas.

dependent partly on irrigation but partly also on

rainfall, and therefore covariant. Increases in fertiliser

use. and most shifts towards modern seed varieties,

increase ‘worst-case’ output-pcr-year for any given

farm — even if that rather unimportant number, the

coefficient of variation of national output, goes up.

The damage done by an unexpectedly bad season

should therefore be reduced by this sort of researchlinked intensification. But neither the increases, nor

the improved levels of food reserves associated with a

shift to modern varieties, can be achieved without

substantial spending on agricultural research and on

input supply and delivery, in most areas probably

including at least micro-level irrigation systems.

IV

Some Possible Areas of Remedy

I should like to follow up the above remarks with

something which is at best a set of notes towards a

research agenda, that may stimulate others. The

question is: how can one reduce the extent to which

seasonality leads to increases in ultra-poverty? Several

forms of adaptation to seasonal stress, by people

already at risk, are possible.

First, food behaviour could be adapted. In an

unexpectedly bad season, it may become possible for

different groups of poor people to raise their ratios of

consumption to income, of food to consumption, or of

cheap (c.g. reserve-crop root) consumption to food. It

may become possible for the potentially ultra-poor to

escape their fate by adapting the timing of work, or of

meals, or the places of work, to reduce the amount of

calories required and/or to improve the conversion

efficiency of food into work, although experts disagree

about the extent to which individuals differ, over time,

in their metabolic rates per kg — or can adapt their

rates to increase food-to-work conversion efficiency in

times of nutritional stress; how much adaptation is

possible, among whom, for how long, and what

measures might be taken by individuals or societies to

improve benign adaptations to nutritional stress? It

may also be possible to improve the intra-family food

distribution in times of seasonal stress. Some of these

strategies are doubtless adopted by poor people

seeking to cope with bad seasons, but not all people

adopt the best strategies in each bad season; perhaps

some can learn from others, or can be helped by

outside systems to do so.

Second, households in seasonal stress may be able to

respond by adapting their use of factor inputs. Work

timing, duration, type, or search behaviour may be

adaptable between peak and slack seasons, or among

household members in seasons of nutritional stress. If

assets are owned, it may be possible at some cost to

shift probable income from assets into the more

stressful, or less secure, part of the year. Plainly, in

environments where there are no major long-term

trends of change, poor households are likely to learn

such adaptive techniques by themselves — they must,

to survive. But few environments are as static as this,

and indeed policy itself does much to change them,

often in ways that destroy traditionally learned

methods of seasonal coping. Also, many of the poorest

children do not at present survive seasonal stress; and

many of the more adaptable adults either migrate or

enrich themselves enough to reduce its impact, leaving

the burdens to fall on those who remain in the

potentially ultra-poor groups.

A third possible area of adaptation concerns seasonal

migration. Often, seasonal migrants are the poorest

and most oppressed of groups. Yet anti-poverty policy

has seldom made effective contact with them. Further,

Indian experience suggests that seasonal migration is a

major outlet for people — e.g. landless or nearlandless labourers moving from Bihar to the Punjab

for work — who would otherwise be much poorer;

policies that subsidised or otherwise encouraged

migration of labour, instead of mechanisation to

displace labour, could have major beneficial seasonal

effects. Problems of schooling and health for children,

whether they accompany the seasonal migrants or are

left behind, need careful attention, however.

Fourth, it would be worth looking at the possibility of

adapting methods of seasonal financial-cum-land

management. When a really bad year comes along, in

the most difficult seasons, many people are pushed

over into ultra-poverty by being compelled to sell or

mortgage the little land they have. Can alternative and

less onerous methods, at least providing some effective

competition against the small number of local

moneylenders, be found in such circumstances?

Finally, it would be worth asking whether common

property resources, such as access to grazing, water.

thatch grass and fuels, arc — or can be rendered — less

'seasonal' than private property resources. Work done

by Jodha in Rajasthan confirms that common

property resources are a much larger part of income

for the very poor than for the better-off — but that

income from common property has been eroding

rapidly in the last 15 years or so [Jodha 1983]. The

analysis of common property management and

protection is among the many parts of our subject that

needs to take on a seasonal tinge, if the access of very

poor people to basic food requirements in difficult

times is to be safeguarded and improved.

These are admittedly scrappy ‘thoughts of a dry brain

in a dry season’. Perhaps there is an analogy between

seasonal studies and women’s studies. In both cases

the impact and effectiveness of social scientists will be

greatly reduced, if we make a little ghetto for seasonal

studies or women's studies. In the case of seasons, our

entire analysis of the economics, sociology and politics

of agriculture and the rural economy — and of its

relations with the city, about which I have said almost

nothing here — needs to be permeated with an

awareness that impact on the very poor matters most

in the seasons of greatest risk, and is somewhat less

important in the more well-favoured times of the year.

References

Bcngoa. J. M. and G. Donoso. 1974, ’Prevalence of protein

caloric malnutrition. 1963-1973*. PAG Bulletin, vol 4 no 2.

pp 24-35

Chambers. R.. R. Longhurst and A. Pacey (eds), 1981.

Seasonal Dimensions to Rural Poverty, Frances Pinter.

London

7

Edirisinghe, N., and T. Polcman, 1983, ‘Behavioural

thresholds as indicators of perceived dietary adequacy or

inadequacy’, Cornell International Agricultural Economics

Study No 17, Ithaca, NY

8

Lipton. M.. 1983a, ‘Poverty, undernutrition and hunger'.

World Bank Staff Working Paper No 597. Washington DC

— 1983b. ‘Labour and poverty’. World Bank Staff Working

Paper No 616, Washington DC

Greer, J., and E. Thorbccke, forthcoming. ‘Food poverty

profile applied to Kenyan smallholders’. Economic Develop

ment and Cultural Change

— 1983c. ‘Demography and poverty’. World Bank Staff

Working Paper No 623, Washington DC

Jodha, N.. 1983. ‘Market forces and the erosion of common

property resources’. Paper presented at the International

Workshop on Agricultural Markets in the Semi-Arid

Tropics. ICRISAT

— 1985a, ‘Possibilities of reduced dietary energy require

ments and of adaptation to low intakes: implications for

economics and for policy’, World Nutrition Society Conf.,

Brighton (mimeo)

Keller, W. and C. M. Fillmore, 1983, ‘Prevalence of protein

energy malnutrition'. World Health Statistics Quarterly,

vol 36 pp 129-67

— 1985b, ‘Land assets and rural poverty’. World Bank Staff

Working Paper No 744, Washington DC

Kumar, S. K.. 1977. ‘Role of the household economy in

determining child nutrition at low-income levels: A case

study in Kerala', Cornell University Occasional Paper

No 95. Ithaca, NY

Rao, V. Bhanoji. 1981, ‘Measurement of deprivation and

poverty based on the proportion spent on food: an

exploratory exercise’, World Development, vol 9 no 4,

pp 337-53

Women and Seasonality: Coping with Crisis and Calamity

Janice Jiggins

I

Introduction

Over the last few years, a great deal of evidence has

been amassed on the impact of seasonal adversities on

women, children and their families. Attempts have

been made to differentiate the varying impacts on

households and, within households, on women and

children in different income classes and to build

dynamic models of the ‘screws and ratchets’ which

push manageable seasonal stress toward the break

down limits of livelihood systems.

What is attempted here is an exploration of the

contribution of female production, labour and

domestic domain services to the management of inter

annual and intra-annual uncertainty, the steps in the

sequence of deterioration under accumulating stress.

and of the options open to women and their children

through and beyond the point of family disintegration,

when managing seasonalities becomes a matter of

individual physical survival.

The evidence of female mortality and morbidity rates,

from some areas at particular times, suggests that the

wastage of females may be countenanced in times of

acute stress as necessary to the survival of social

systems as a whole, however distressing at the level of

family survival. It establishes the extreme end of a

range of situations in which poor rural men and

women act and react to expected inter-annual and

intra-annual fluctuations, interspersed with shocks

whose advent is always latent but whose timing and

severity is unguessable.

The management of uncertainty is inherent in small

producers’ and labourers’ livelihood systems; not

surprisingly, these are characterised by flexibility, the

maintenance of a range of options to meet expected

fluctuations in resource endowments, entitlements to

food, work and income, climatic variation and the

unreliability of government services. If it is true that

the less flexible the livelihood system, the harder it is to

manage seasonal stress and sudden shock, then it is

important to understand how and what different

members of a household contribute to that flexibility.

Such an exploration leads to consideration of how

members of households assess probabilities and how

they express risk preferences. It has been fashionable,

for example, to assert that small producers prefer to

minimise risk by aiming for inter-annual yield stability

around the minimum necessary to meet subsistence

needs. The concentration on yield stability per se may

be diverting attention from a more dynamic calculus

in which household members complement each

others' contributions to livelihood stability across

seasons by maintaining the capacity to transfer

resources in and out of the sub-systems which together

constitute their livelihood

In some enterprises, one family member might be

happy to make a high risk-high pay off investment if

assured that failure could be covered, or another to

make a high input-low return investment if that return

were deemed essential but could be gained in no other

way. This calculus is likely to changeover time. As in a

commercial business, both risk preferences and

probability assessments are likely to become more

conservative after a run of bad years, as assets and

room for manoeuvre dwindle and as investments

made in the course of a run of good years have to be

paid for out of shrinking revenues.

As households head into the bottom of the cycle, it

becomes a fine run thing for many of them to maintain

the flexibility to ride out the bad years. The need to

concentrate time and effort on essential high inputlow return activities (such as fetching water from

distant river beds in the dry season), may absorb

household resources to the point of no return;

households here must enter into new livelihood

systems closer to the point of destitution, or

disintegrate.

It is because men and women make separate if

complementary contributions to the maintenance of

IDS Bulletin. I9S<>. vol 17 no 3. Institute of Development Studies. Susses

9

livelihood flexibility within the framework of expected

inter-annual and intra-annual uncertainty, that not

only the timing of a sudden shock but the gender of its

victim(s) is important. The death of children from

measles at the beginning of the agricultural season

might provide greater room to manoeuvre to a couple

seeking their daily living from an uncertain and

gender-ascribed wage labour market or, on the other

hand, remove essential labour at a critical moment

from a female household head farming on her own

account. The death of a husband for a relatively welloff woman in a tenant household might lead to her

forced acceptance of the position of unpaid

agricultural worker for her brother-in-law; the death

of the wife, on the other hand, might offer her husband

the opportunity for re-capitalisation of his farming

activities through remarriage and the acquisition of a

second dowry.

The options are various, the strategies complex and, it

seems, as yet we understand very little about how these

operate over time for households in different income

groups or for individual household members. The

following section explores briefly some of the ways in

which women are contributing to the management of

expected seasonal uncertainty and the maintenance of

livelihood flexibility. Sections III and IV attempt a

progression through time in the face of relentless

seasonal adversity.

II Uncertainty and Flexibility

Although neither the timing, distribution nor intensity

of seasonal stresses may be known in advance, their

advent and the range of probable fluctuation are

accepted as normal occurrences by the rural poor.

Among the range of possible responses, seven which

tend to be particular to women are outlined here in

brief.

Switching Tasks and Responsibilities ascribed by

Gender

In many rural societies, specific tasks and areas of

responsibility are ascribed by gender. Where these are

rigid, it might be that households — particularly low

income households — find the management of

seasonalities harder than in societies in which there is

some scope for men and women to take over each

other’s tasks and responsibilities as need and

opportunity arise. Contrast the following two

examples. In an area of Tanzania in which only

women cook and carry water, dry season water

carrying absorbs a great deal of female labour time.

Men welcomed a proposed village water facility

because, they said, ‘Water is a big problem for women.

We can sit here all day waiting for food because there

is no women at home’ [Wiley 1981:58J.

(i)

10

In contrast, a Javanese case study reports greater

scope for a more flexible response to gender-ascribed

tasks and seasonal opportunities; ‘Men, for example,

sometimes stay at home to babysit and cook a meal

while adult women and girls are off harvesting, or

trading at the market’ [White 1985; 132].

In a study of the pastoral Orma along the Tana River

in Kenya, Ensminger (1985) presents data which show

only slight variation in the amount of time spent on or

in the pattern of male and female activities between the

seasons, except that, in the dry season, women do

slightly less work such as cooking and milking and

men spend more time in stock-watering and well

digging. Although young girls may take on some of the

tasks associated with (male) herding, in general — at a

time of maximum nutritional stress — men’s dry

season work increases somewhat whilst women’s

leisure time increases. Asking why there arc ‘relatively

few age/sex cross-overs of labour allocation between

seasons’ (page 14), Ensminger finds that her data do

not satisfactorily support explanations based on

reproductive rationality, differential physiological

efficiencies, social reproduction needs nor redistri

bution.

Indeed, it would seem that it is partly the social

perception of the scope for switching rather than

‘objective’ assessments of capacity or returns which

determines how flexible households can be in

assigning seasonal labour tasks. In a study of labour

market behaviour in South India, Ryan and Ghodake

(1980) attempt to relate the effects of season, sex and

socioeconomic status and speculate that differential

labour market opportunities would support the

economic rationality of skewed intra-household food

distribution toward adult males but, as Schofield

(1974) points out, we simply do not know if this

presumed rationality leads to food being seasonally

distributed independent of the task and sex of the

operator:'.. . are women fed more when weeding and

men when ploughing? In this case, commonsense

would suggest that available food is so distributed to

the workers that the non-work force section bears the

brunt of seasonal variation in food supplies’

[Schofield 1974:26],

Where male and female farming are partially

separated within the household livelihood system, the

answer to the question of the intrahouschold pattern

of income and food distribution in relation to

women’s labour productivity, as Jones (1982) has

demonstrated for a Cameroonian case, may lie in

calculations of the intrahousehold rate of compen

sation rather than market opportunity costs.

Another factor may be the degree to which own

account production is the main livelihood source. One

study in Cajamarcan in the Andes found that in

landless households depending on non-farming

income-generating activities for the major part of their

livelihood, a ‘flexible sexual division of labour [in

agriculture] appears to be required by economic

necessity', whereas in landed households, agriculture

is predominantly a male activity [Deere and de Leal

1982:88],

(ii) Diversifying Household Income Sources

It is common in development studies to see female

income referred to as supplemental and for it to be

subsumed within estimates of household income.

Neither practice seems particularly helpful. For

growing numbers of households headed by women,

women’s earnings form the main cash source; in

households where male and female responsibilities arc

separated, women are obliged by the terms of their

marriage contract to find the cash needed to fulfill

their assigned responsibilities; amongst the poorest

households, women’s earnings may form an equal or

larger share of household income; a greater portion of

the income accruing to women than to men tends to be

spent on household welfare and consumption needs.

For all these reasons, in terms ofseasonal analysis, the

sex of the income-earner and the intra-household

distribution of income and responsibility is thus likely

to be more important than total household income as

an indicator of the household’s capacity to maintain

itself in the face of seasonal adversity.

Women in Rwanda combining farming with child care.

Changing the Intensity and Mix of Multiple

Occupations

There are good records of women manipulating the

intensity of performance and the mix of occupations

associated with their multiple roles in order to cope

with seasonally urgent tasks. In general, it would

appear to be their domestic domain roles which are

squeezed rather than production or income-earning.

though, as one would expect, the balance of net

advantage may be different for women in households

in different income classes [for a Philippines example

see Illo 1985:85-7], For example, surveys among

primary school children in the Mochudi District of

Botswana during the ploughing season showed that

nearly one third of primary school children were

caring for themselves without adult help in the month

of February whilst parents were absent at the lands

[Otaala 1980]. Cooking may be reduced to once a day

or every two days during peak farm labour periods or

staples substituted by snack foods which can be eaten

raw [Bantje 1982a. Table 2; Jiggins 1986]. Ryan and

Ghodake [1980] note for four South Indian villages

that it is the hours women work in the domestic

domain or as unpaid farm family labour which tend to

fluctuate seasonally rather than the hours of waged

work.

(iii)

A number of studies do, in fact, show that women

make careful judgements of the balance of advantage

between, for example, maintaining food stocks and

converting a portion to beer-brewing and selling as the

agricultural season progresses [see Saul 1981 on

sorghum beer-brewing in Upper Volta] or between

allocating their labour to food production and

processing for domestic consumption or to marketing

[see Kebede 1978 for the balance between onset (the

‘false banana’) production and the chircharo system of

trading among the Gurage in Ethiopia],

There is, further, growing evidence of the close

correlation between female income-earning and child

bearing: the higher women’s income, the lower the

number of pregnancies [Evenson 1985:27], The causa!

relationship appears to be mediated through the

monetisation of women’s time. If we have evidence

that changes in agriculture lead to an increase in

women’s time input with no increase in — or even loss

of control over — their income, then we can expect

that the adverse seasonalities associated with maternal

and child health will, in fact, be exacerbated and may

be contributing to the kinds of family breakdown

outlined in Section IV.

11

(iv) Household Gardening

The domain of the household garden provides a

further clement of flexibility in the livelihoods of those

with access to land. Studies from Grenada.

Zimbabwe, West Africa, Jakarta. South East Asia and

Peru emphasise the importance of household gardens

under women’s care as a source of early-maturing

varieties of staples to carry families over the hungry

season till main crops mature, as reserve sources of

plant materials should main crops fail, as conservation

sites for special or preferred varieties and as testing

grounds for new varieties or practices [Brierley 1976;

Callear 1982; Eijnatten 1971, Evers 1981, Ninez 1984.

Stoler 1978]. A study in Kalimantan in Indonesia

recorded an average of over 40 different species of

vegetable, spice and fruit crops in household gardens

[Watson 1985:198]. Local cultigens, semi-wild and

protected wild species, together with small stock and

poultry, may add to the diversity and richness,

constituting a complex biological coping mechanism

responsive to intra-annual and inter-annual climatic

and labour time variations, meeting specific seasonal

end-uses which cannot be provided by field crops.

however abundant [Jiggins 1986].

(v) Food Processing, Preservation and Preparation

The choice of crop mix, plant characteristics and

amount of time devoted to cultivation is not

determined solely by consumption preferences nor are

food purchases determined only by income; they are

intimately associated with the technology available to

women for domestic processing, preservation and

preparation. These technologies in turn may be linked

to the seasonal availability of different types of fuel for

cooking and space heating (Foley et al 1984:34] and the

differential fuels available to women in different

income strata through the seasons [ibid 36]. Vidyarthi

[1984] shows from data for one Indian village, the use

of dung and firewood by women in bullock-owning

households and an increasing reliance on crop

residues by poorer women, who use spiky millet stems

through the end of the Kharif season in November,

then pigeon pea stems through the end of rabi in April

(which give the best sustained heat of all residues), and

then a weed, Ipomeafitulosa, which gives a smoky heat

and must be gathered, cut and dried for a month

before use, and gathered wood. He estimates that

agricultural residues may form around 40 per cent of

all fuels used by poorer women.

Huss-Ashmore details these links carefully for female

headed households in highland Lesotho [HussAshmore 1982:156]. In Mokhotlong the type of fuel

used and the time spent getting it vary according to the

seasonal availability of dung. Slow-cooking protein

sources are not used equally through the year but are

depicted during the cold season when the slow burning

12

compacted dung is available. ‘During the summer the

population relies heavily on wild vegetable protein

sources, which require more time to locate and gather

but which can be rapidly cooked', using the horse and

cattle dung picked upon the high pastures and kindled

with quick-burning resinous and woody shrubs [ibid

157J. It is fuel seasonalities and not crop availability

which determine which foods are eaten and the food

preparation equipment used at different seasons.

Women also attempt to cope with crop seasonalities

through food processing, to extend the storability and

shelf life of perishables, from simple sun-drying of

leaves and vegetables treated with soda ash, to more

elaborate transformations such as those involved in

the making of Kenke and gari (cassava products) in

West Africa or chuno (potato products) in the High

Andes.

(vi) Social Organisation

An apparently growing phenomenon is the formation

of multi-generational, multi-locational networks of

households headed by women. Only some of these are

the result of family breakdown — women may be

choosing to have children without what they perceive

to be the burdens of marriage [Kcrven 1979]. They

appear to be an emergent form of social organisation

designed to spread risk and optimise seasonal

management strategies in areas of high gender-specific

migration, marked seasonality, and marked gender

specific livelihood opportunities [see Kervcn 1979 for

Botswana examples; Phongpaichit 1980 for Thai

examples].

Another strategy in areas where there is a developed

labour market is for women from poor households to

associate in specialist labour gangs to take advantage

of seasonal cropping patterns. They may travel over a

wide area, moving with the season from contract to

contract, with gangs known for their speed and skill

gaining premium rates. In a ten-member Sri Lankan

gang documented in 1979, which moved from the wet

zone to the irrigated dry zone twice a year to carry out

paddy transplanting, six were married women, of

whom two were separated from their husbands

[ESCAP/FAO 1979:28-40]. The four resident hus

bands worked as casual labourers. The other women

lived with their families, of whom only three had even

a tiny plot of high land for cultivation. Their ages

ranged from 26 to 55 years and they worked as casual

estate labourers the rest of the year. Their

transplanting earnings were spent on daily living and

family needs; their own clothes and jewellery;

furniture and pilgrimages. The high preference for

turning their earnings into an easily convertible store

of value under their own control, as a hedge against a

crisis and calamity, has been noted in many studies

[Jiggins 1983].

Yet another mechanism is to develop semi-formalised

women’s groups based on existing forms and

principles of female association. Yet these might not

be as useful as might at first be supposed in the

maintenance of the poorer members’ livelihoods

through seasonal stress. In a study of women’s groups

in Kenya, members were asked to identify those who

were 'famine resistant’ or ‘famine-prone’ i.e. who

would or would not be able to stand even a mild

harvest failure or livestock disease. Famine-proneness

turned out to be associated with illiteracy and

household headship [Muzale and Leonard 1985:19].

Resurveyed after a year of drought, the membership

was found to have dropped to those previously