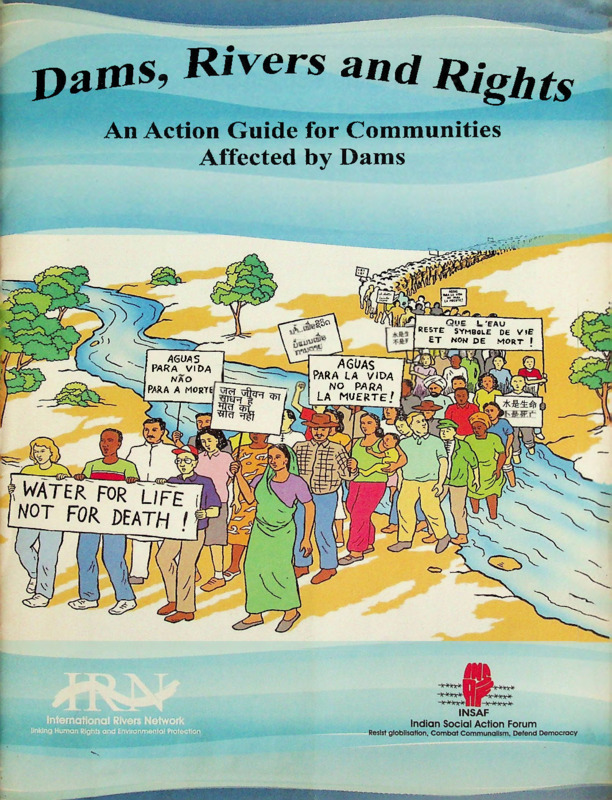

Dams, Rivers and Rights An Action Guide for Communities Affected by Dams

Item

- Title

-

Dams, Rivers and Rights

An Action Guide for Communities

Affected by Dams - extracted text

-

pams, Rivers and Rights

An Action Guide for Communities

Affected by Dams

Reste

ET

AGUAS

I PARA VIDA

NAO

Para a morte

AGUAS

PARA LA VIDA

NO PARA

LA MUERTE'

symbole oe vie

non DE

MORT I

Acknowledgements

From the original publisher

This action guide was produced with the generous support of Oxfam Australia and the Ford

Foundation. The text was written by Aviva Imhof, Ann Kathrin Schneider and Susanne Wong

Shannon Lawrence edited the final draft and Jamie Greenblatt helped with proofreading.

Tracy Perkins provided invaluable help and expertise with illustration concepts, layout and

overall project direction. Thanks to Haris Ichwan for his beautiful illustrations. Thanks to

Hesperian Foundation for allowing us to use illustrations from their extensive collection.

Special thanks to our Advisory Group for providing comments and suggestions and for field

testing the guide with dam-affected communities. This guide was inspired by the courage

and wisdom of dam-affected people and their allies around the world.

Advisory group members include Girin Chetia (India), Pianporn Deetes (Thailand), Ira Pamat

(Philippines), Franklin Rothman (Brazil), Kevin Woods (Thailand/US) and Ercan Ayboga

(Turkey).

Original illustrations by Haris Ichwan. Illustrations on pages 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20,

21,22, 23, 28, 30, 32, and 33 provided courtesy of Hesperian Foundation.

Designed by Design Action Collective

Printed by Inkworks Press

Published by International Rivers Network, 2006

1847 Berkeley Way, Berkeley CA 94703, USA

Tel: +1 510 848 1155, Fax: +1 510 848 1008, info@irn.org, www.irn.org

ISBN-10: 0-97188-584-2

ISBN-13: 978-0-97188-584-4

Re-published by:

Indian Social Action Forum (INSAF)

A - 124/6, Katwaria sarai, New Delhi- 16,

Telefax :+91-11-26517814

Community Health Cell

Printed by:

Designs and Dimensions, L-5 A, Sheikh Sarai,

Library and Information Centre

# 359, "Srinivasa Nilaya”

Jakkasandra 1st Main,

1st Block, Koramangala,

BANGALORE - 560 034.

Ph : 2553 15 18/2552 5372

e-mail: chc@sochara.org

Vamsr Rivers and Rights

An Action Guide for Communities

Affected by Dams

International Rivers Network

INSAF

Indian Social Action Forum

Unking Human Rights and Environmental Protection

Resist globlisation, Combat Communalism. Defend Democracy

Difficult Words

Compensation: Money or other things given to replace people’s losses.

Decommission: To destroy a dam or stop the use of it. This can involve changing a dam structure,

permanently opening its gates or removing a dam.

Displacement: Removal of people from their homes and lands.

Downstream: Area located below or down the river from a dam.

Field Surveys: Information gathering by talking to people and looking at things directly.

Mitigation: Measures to reduce the impact of a dam. They can include creating wildlife

sanctuaries, releasing water downstream of the dam or providing money and new livelihoods to

affected people.

Non-gOVemmental organization (NGO): An organization that is independent from the government.

Non-Violent direct action: Peaceful event organized to pressure decision-makers and raise public

awareness about a struggle.

Public development bank: An international bank, like the World Bank or the Inter-American

Development Bank, that lends money to governments or companies for development. Public

development banks are controlled by governments.

Re-Operation: Changing dam operation to allow the river to flow more naturally.

Reparations: Money or other things given to replace losses or compensate for damages caused

by an existing dam.

Reservoir: A lake that is created when a dam is built.

Resettlement: Moving people into new or existing villages to make way for a dam.

Schistosomiasis: Disease caused by contact with certain types of snails that live in fresh water

from canals, rivers or lakes.

Sediment: Sand, dirt and rocks that are carried by a river.

Upstream: Area located above'a dam, including the reservoir and areas further up the river.

Watershed: The area of land that catches rain and snow that flows into a river.

World Commission on Dams: Independent international commission set up to study the

performance of dams, examine alternatives and make recommendations for future dam

building. Final report issued in 2000. Information available at www.dams.org.

Table of Contents

Introduction

2

Chapter 1: Basic Information About Dams

3

What is a dam?............................................................................................................................ 3

What do dams do?....................................................................................................................... 3

Who benefits? Who loses?.......................................................................................................... 4

How do dams perform?................................................................................................................ 5

Who pays for dams?.................................................................................................................... 6

Chapter 2: Impacts of Dams

7

Graphic: Dam impacts................................................................................................................ 8

Realities of displacement..........................................................................................................10

Millions of people affected downstream................................................................................... 12

Chapter 3: The International Movement Against Destructive Dams...........................

14

Successes of dam fighters...................................................................................................... 15

Successes...but dams still threaten communities.................................................................16

Chapter 4: How to Fight Dams.......................................................................................

17

Planning your campaign............................................................................................................ 18

Important strategies to fight dams............................................................................................ 20

What you can do at each stage of dam building..................................................................... 24

Chapter 5: Alternatives to Dams...................................................................................

29

Alternatives for energy............................................................................................................... 29

Alternatives for water................................................................................................................. 32

Alternatives for flood management........................................................................................... 34

Conclusion......................................................................................................................

Regional Contacts............................................................................... 37

lu 3 o >

(1)

36

Introduction

Around the world, people are rising up against big dams. They are fighting to protect their rivers

and their livelihoods from new dams. They are demanding compensation for problems caused

by old dams. They are proposing better alternatives for energy, water supply and flood

management. All of them are fighting for a voice in decisions that affect their lives.

Over the last 20 years, the international movement against dams has grown strong and had

many successes. Some dams have been stopped. Better alternatives, such as small dams

and water conservation, have been implemented. Communities have received better

compensation. Some dams have been taken down.

But new dams continue to threaten communities worldwide.

International Rivers Network created this action guide to empower communities threatened by

new dams and to share ideas from the growing international anti-dam movement. International

Rivers Network and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) around the world are

ready to help you in your struggle. NGOs that may be able to assist you are listed at the end of

this guide.

We hope this guide provides information and tools to help you decide how to respond to a

proposed dam, how to protect your rights and how to demand a voice in decisions about dams.

► At the beginning of the guide is a list of difficult words and their definitions.

► Chapter 1 provides general information on dams, including how they work, who benefits

from dams and who pays for them.

► Chapter 2 talks about the impacts of dams on communities and natural resources.

► Chapter 3 describes the international movement of people against destructive dams and

its successes.

► Chapter 4 gives ideas for how communities can challenge dams and defend their rights.

► Chapter 5 provides information about better options for meeting people’s water, energy

and flood management needs.

► At the end of the guide is a list of contacts that may be able to help you.

We wish you success in your struggle against destructive dams. We are one in the struggle for

justice and dignity. Water for life, not for death!

International Rivers Network

& Indian Social Action Forum

(2)

Basic Information About Dams

What is a dam?

A dam is a wall built across a river. Dams can be made of earth, rock or concrete. They block

river flow, creating artificial lakes called reservoirs. Water contained in reservoirs can be used

to generate electricity, to provide water for irrigation and drinking, to aid navigation of boats, to

control floods and for recreation. Some dams are built to do more than one of these things.

More than 47,000 large dams (taller than 15 meters) have been built around the world. China,

the United States and India have the most large dams. The world’s biggest dams are over 250

meters tall (or higher than a 60-story building) and several kilometers wide. They cost billions of

dollars and take more than 10 years to build.

What do dams do?

► Water supply and irrigation

dams store water in a reservoir.

This water is sent to cities or

farms using large pipes and

canals.

► Hydropower dams use water to

turn the blades of machines

called turbines to generate

electricity. Electricity is sent to

cities or factories using

transmission lines. After passing

through the turbines, water is

released back into the river below

the dam.

► Flood control dams store water

during heavy rains to reduce

flooding downstream.

Dams come in many shapes and sizes but

most have these features.

► Navigation dams store water and release it when water in the river is low so boats can

travel up and down the river year-round. They are typically built with locks, or devices

which raise and lower boats so they can travel past the dam.

(3)

<J> Who benefits? Who loses?

Factories and city residents benefit from power generated or water stored by dams. Large

agricultural companies benefit from cheap water for irrigation. Dams often take resources away

from rural communities to give these benefits to industries and people living in cities.

Sometimes these industries and people are in neighboring countries.

Construction and engineering companies benefit too. They receive millions of dollars for

designing and building dams. Governments can benefit from taxes collected during operation of

a dam. Because of the large amounts of money spent on dams, corrupt government or

company officials sometimes take money for their own benefit.

The ones who have suffered most from large dams are rural farmers and indigenous or tribal

peoples. Millions of people have been evicted from their homes to make way for dams and

reservoirs. Millions more living downstream from dams have suffered impacts to their

livelihoods and well-being.

To make matters worse, dam-affected people are rarely included in decisions about whether or

not to build a dam. They usually do not know their rights to information and public hearings, to

demand new land and livelihoods, and even to oppose dams. They typically do not receive

benefits of electricity or water although they may live right next to a dam.

Large-scale farmers receive irrigation

water and power from dams.

Dam-affected people often do not receive these

benefits and end up with worse land.

Some dams make floods worse instead of better

How do dams perform?

When dams do not perform well,

governments and people suffer

While dams can provide some benefits, they often

do not produce as much power or irrigate as

much land as expected. Water supply dams often

provide less water than promised. This usually

happens because dam builders overestimate how

much water is available in the river for use.

Flood control dams can stop small floods, but they

can also make damages from large floods worse.

People may build more houses and shops

downstream from a dam because they feel safe.

However, when a large flood occurs and the

reservoir cannot hold the floodwater, more people

downstream may lose their belongings and even

their lives.

Dams do not last forever. They are usually built to

operate for a certain number of years. The

lifespan of a dam depends on many factors,

including how much sediment is in the river. Over

time, reservoirs fill up with sediment. As the

sediment builds up, dams become less effective,

until they can no longer operate.

(5)

The Yacyreta dam was described by former

Argentinean president Carlos Menem as a

“monument to corruption." The dam’s costs have

increased from USS2.7 billion to USS11.5 billion,

and the project is still unfinished.

The dam, located in Argentina and Paraguay,

produces only 60% of the power it is supposed

to produce. The group that manages the dam is

billions of dollars in debt and cannot pay back

loans because the project is unprofitable.

Governments often borrow money to build dams.

They expect to earn lots of money. However, if

dams do not generate as much power as

expected, governments may not have enough

money to pay back loans. They may cut

spending on education and health care which

causes suffering for people too.

For cash-poor countries, investments in risky

dams may increase their debt to institutions like

the World Bank. In these cases, dams built to

reduce poverty may actually increase it.

Who pays for dams?

About USS40 billion is spent on dams each year. Since dams are so expensive to build,

governments usually need to get loans from many funders. The World Bank is one of the most

important dam funders. This public development bank has spent US$60 billion on 600 dams

all over the world. Regional development banks - like the Asian Development Bank, African

Development Bank and Inter-American Development Bank - lend money to governments and

companies to build dams too.

When public development banks fund part of the dam construction, it makes it easier for the

government to get loans from private banks too. Rich countries, like Japan and Germany, also

give grants and loans to governments that want to build a dam.

After the dam is built, the government has to pay these loans back. If the dam does not make as

much money as it was supposed to, the government still has to pay back the debt.

People in rich countries benefit from dam building in two ways. Dam building companies

receive money to build dams, and governments receive interest payments when poor

countries pay back loans.

(6)

CHAPTER 2

Impacts of Dams

When Malisemelo Didian Tau first heard about plans to build a big water

supply dam on her land in Lesotho, Africa, she resisted. But the dam

builders convinced her that only a few people would have to move away to

make many people’s lives better. They promised Malisemelo and her

community compensation, water supply, schools and new homes.

But the promises were not kept. Says Malisemelo, “When we do not get enough compensation

for our lands, it is the death of our children and the death of coming generations because they

will have nothing to help them survive in the future.”

This is not just Malisemelo’s story. Between 40 and 80 million people have been forced from

their homes and lands to make way for dams. Most of these people are poorer now. Their

livelihoods, cultures and communities have been destroyed.

Dams have flooded some of the world’s most important animal habitats and fertile farmlands.

Rivers have been ruined. Fisheries have been destroyed. Some fish, animal and plant species

have disappeared.

This chapter explains the impacts of dams on communities and natural resources. We examine

the specific impacts of dams on displaced families and on communities living downstream of

the dam. Then, we discuss what communities in Lesotho are doing to defend their lives and

livelihoods from big dams.

(7)

Dams Impacts

Dam destroy communities

Reservoirs destroy animal habitat

Families living in the reservoir area lose

their homes, lands and livlihoods.

Communities are often not resettled

Together, and people are usually poorer

after they move.

Forests, wetlands and other habitat

are flooded. Reservoirs can also split

up animal habitat and block migration

Routes

(8)

Dams give water and energy to the rich

Dams kill fish and destroy fisheries

Fish populations decline upstream because fish cannot

migrate post dams. Below dams, changes in water flow

and quality can destroy fish. People who despend on

fish for fdood and income suffer.

Dams and reservoirs take water from

rivers that rural farmers and fishers use.

They provide water and electricity instead

to people who can pay for these services.

Crop yields Decline

Dams flood some of

the best farmlands and

block sediment from

flowing downstream to

fertilize crops. Water

released form

reservoirs can wash

riverbank gardens.

$

%

Dams can release

/ polluted water

■MJ? Poor

quality twater causes

.

quality

issness to people and livstock

downstream.

(9)

Realities of displacement

Displaced communities suffer

One of the biggest impacts of dams is the

forced displacement of people from their

homes. Reservoirs flood areas where

people live, grow crops, fish and raise

livestock. Sometimes families have lived on

the land for many generations. Despite this,

governments and dam builders force people

to leave their homes and lands. Entire

villages are flooded.

40-80 million people have been displaced

by dams worldwide.

Displacement makes most people poorer. They have problems getting enough food to eat and

income to support their families. They may no longer be able to survive by farming and fishing.

Rural communities may be forced to move to cities or towns where they must adapt to a new

way of life. In cities, they can face new problems like crime and drugs.

Displacement destroys communities and cultures. Villages are often divided and separated, so

people no longer live close to friends and relatives. Indigenous people and ethnic minorities are

often the victims of dam

building. Cultural sites and

graves of ancestors may be

flooded. People may lose

connection to their ancestral

lands.

Says an ethnic Nya Heun

man forced to move for the

Houay Ho Dam in Laos,

“Some people thought they

would get sick if they moved.

They thought it’s not our own

land. It’s like moving to a

different country. Our sense

of place, our sense of home,

was destroyed."

Some people displaced by dams have been moved

to land that is not fertile or is too steep to farm.

(10)

Dam-affected people often

suffer emotional and physical

problems. Alcoholism,

depression, domestic

violence, disease and even

suicide often increase after

they are displaced.

Problems with resettlement

Some people who are displaced by dams are given new houses. This is called resettlement.

People may be moved into already existing villages or into new villages built just for damaffected people.

Dam builders often promise that people’s lives will be better after resettlement. They promise

that people will get jobs and big new houses with electricity and water. However, these promises

are usually broken. The houses are often small and poorly made. People cannot afford

electricity or water fees. They usually receive less land than they had before. The new land may

be more difficult to farm than their old land.

Resettled people are often unable to farm or fish or raise livestock like they used to. Sometimes

dam builders encourage them to adopt new livelihoods, like cattle grazing or growing crops to

sell at markets. However, this is usually unsuccessful and people may have a harder time

making a living than before.

Many do not receive enough compensation

Compensation is money or other

things given to replace what people

have lost. When people are given

cash compensation, it is often not

enough money for them to survive.

If people are not used to cash, they

may not know how to make the

money last for a long time.

Many people do not receive

compensation. The government

may say the people have no right to

compensation because they do not

legally own the land they live on.

The community may share the land

or some people may farm land that

is owned by other people. Or the

government may not think they will

be affected by the dam. When

people do receive compensation, it

is often not enough to survive.

Without enough food or money to survive, families often

end up living in slums or working as migrant laborers.

“Government officials told us, ‘Give up your small home in the interest of the big home [the

nation],’” said Zhang Qiu Lau, who was resettled for the Xiaolangdi Dam in China. “They

promised to pay 15 cents a square foot for our homes and replace all our farmland. But up to

now, I’ve received nothing, no cash. And our family, which had half an acre of good quality

farmland per person, received just half as much of much poorer quality land when we moved to

Xiang Yuan."

(11)

Millions of people affected downstream

Dams have destroyed the livelihoods of millions of people living downstream of dams. The

biggest impacts are on fishing and farming.

Fisheries destroyed

Dams destroy fisheries by changing

water flow and blocking fish from

reaching breeding grounds and

habitat upstream of the dam. Fish

populations usually decline. Some

species disappear. As a result,

people may lose an important source

of protein and income. Their

traditional way of life may also be

destroyed.

Crops decline

Fish catch downstream dropped by 60 percent after

Brazil's Tucurui Dam was built. Fewer people fish today.

People can suffer damages to their

crops. Changes in water flow can

erode riverbanks downstream of dams. Sometimes people’s riverside gardens, land and crops

are washed away into the river.

Rivers carry important nutrients and sediment that

fertilize fields after floods. Dams stop these nutrients

and sediment from traveling downstream. Without these

nutrients, crop yields may decline. People may have to

buy chemical fertilizers. If this is too costly, people may

have to stop farming.

Lack of clean water

Water can often become dirty or polluted downstream of

dams. People and animals may get sick if they drink the

water, especially during times of low flow. People may

get sores or skin rashes if they bathe in the river. Less

water may be available for irrigating crops.

Sudden releases cause damage

Dam operators sometimes decide to suddenly release

water from reservoirs. Water levels can increase rapidly.

People using the river may not get any warnings. Their

boats and fishing equipment may be swept away by the

rising waters. In some cases, people may drown.

(12)

After the Yali Falls Dam

was built, Cambodian

villagers got sores and

rashes if they bathed in the

Se San River.

Before the Katse dam was built in Lesotho, local communities could grow crops all year

round. They grew pumpkins, peas, beans, potatoes and other vegetables. Their large

fields could produce enough food to share with others.

But after they were resettled, communities became poorer. Promises of compensation

and new livelihoods were broken. Some people even died.

“Life here on the resettlement site is difficult. We struggle to get everything, even wild

vegetables. At Molikaliko, we had food all year round. Here, we starve all year round,”

said Nkhono 'Maseipati who was resettled for the Katse Dam.

Communities in Lesotho are still fighting for fair compensation. They have filed complaints

with dam builders, publicized their concerns and organized demonstrations. In late 2005,

a government official promised to give communities everything they demanded. Will these

new promises be kept?

If you hear that a dam may be built in your area, it is important to remember stories like

this one. Think about how your life would change if a dam were built nearby. Imagine how

it would affect your family, livelihood, culture and community.

Questions for discussion:

How will the dam

affect your

community?

Will you have to

move?

How will it affect your

livelihood? Will it

affect your fishing or

farming?

What compensation

or resettlement is

being offered?

What opportunities

do affected people

have to voice their

opinions and state

their demands?

(13)

CHAPTER 3

The International Movement

Against Destructive Dams

Millions of people around the world fight against dams. Fishermen in Pakistan, farmers in

Thailand and indigenous people in Guatemala fight against dams. University professors in

Japan and human rights NGOs in Uganda also fight against dams. They fight to protect people’s

livelihoods and natural resources. And they fight for people’s rights to take part in decisions that

affect their lives.

These efforts are more effective when people work together in regional and international

alliances. Today, there are networks of dam fighters in Latin America, East and Southeast Asia,

South Asia, Europe and Africa (see Regional Contacts section for more information). These

networks include dam-affected people, people's movements, NGOs, researchers and other

groups. People use these networks to share information, organize joint activities and work

together to stop dams and defend people’s basic human rights.

Dam fighters have organized two international meetings to share experiences and develop

strategies to fight destructive dams. In 1997, participants from 20 countries met in Brazil. A

second meeting took place in 2003 in Thailand with 300 participants from 61 countries. The

movement continues to grow and get stronger.

(14)

Successes of dam fighters

Fewer dams being built

The international movement has been successful in stopping

dams. There are fewer dams being built now than in the past.

Because of strong opposition to dams, governments have even

cancelled dam projects.

Some dams taken down

Today, in the US and Europe, dams that were built many years

ago are being decommissioned, or taken down. The rivers are

returning to life. In France, several small dams on the Loire and

the Leguer rivers were decommissioned in recent years. After

the dams were destroyed, the rivers returned to life. Salmon and

other fish started to swim up and down the river again.

Rights of affected people upheld

Many dam-affected people have successfully fought to protect

their rights. Some people have received better compensation.

Some have participated in decision-making processes. And

some have received irrigation water and electricity.

Because of protests by affected people and their allies, there are

now international guidelines to improve dam-building. These

guidelines were developed by the World Commission on Dams

(WCD). The WCD says that no dam should be built without the

agreement of the affected people. Dam builders should sign

legal contracts with affected people for compensation. If the

contracts are broken, affected people should be able to take

legal action against dam builders. Many governments have not

adopted these guidelines, but dam-affected people are using

these guidelines as a tool to fight for their rights.

Less money for dams

Dams are very expensive. Governments in Latin America, Africa

and Asia have to borrow money from public development banks

and private banks to pay for dams. Twenty years ago, these

funders gave a lot of money to build dams. Today, because of

strong opposition to large dams, they loan less money for these

projects. This has made it harder for governments to build

dams.

(15)

Villagers win victory at Rasi Salai Dam

In 2000, the gates of Thailand’s Rasi

Salai Dam were permanently opened.

This was a big victory for dam-affected

people.

The Rasi Salai dam flooded the

farmland of more than 15,000 people. It

blocked fish migration routes and

flooded a swamp forest. It was a

disaster for everyone. Affected people

decided to fight. They demanded that

the gates of the dam be permanently

opened to restore the river and people’s

livelihoods.

They created a protest village in the

reservoir area to bring attention to their

demands. Some protestors occupied

the dam site. They said they would not

leave until the dam gates were opened.

At one point, the protesters were surrounded by rising water. The protests lasted several

years.

In the end, the villagers won. The Thai government agreed to open the dam gates. Since

then, the Mun River has come back to life. People can once again grow crops on the

banks of the river and catch fish. They have regained their livelihoods.

Buppa Kongtham, a leader of the Rasi Salai movement, explained why she fought to

decommission the dam. “Saving the environment is the only way to help my grandchildren

in the long run. That’s what I’m doing for them now.”

Successes...but dams still threaten communities

These are big successes. But a lot still needs to be done. In many countries around the world,

governments are still building destructive dams. Many people still lose their homes and land to

dams and reservoirs. Many powerful governments, companies and development banks have

big plans to build more dams.

► We need to strengthen resistance against destructive dams.

► We need to work together, support each other and learn from each other to protect the

rights of dam-affected people.

When many people fight together against dams, it is harder for governments and companies to

build dams and harm communities.

(16)

CHAPTER 4

Howto Fight Dams

You can do many things to fight dams and to fight for your rights. The first step is to gather

information about the dam and what impacts it might have on your community. Next you should

figure out what you want and how you can make that happen. Then you take action to achieve

your goals. This process is often called a campaign.

It is important to start your campaign as early as possible. Some important actions you can do

throughout your campaign include getting and distributing information, organizing with other

people in your community and working together with national, regional and international groups.

In some countries, organizing against a dam can be dangerous for community members and

their families. Sometimes it is risky to criticize the government or its dam-building plans. It is

important to be aware of these risks when you develop your campaign strategy.

This chapter gives you suggestions for how to develop a campaign strategy. It outlines actions

you can take throughout the dam-building process. Lastly, it describes the three stages of dam

building and identifies important steps you can take at each stage.

March 14 is the International Day of Action Against Dams and for Rivers, Water and Life.

Hundreds of groups around the world take action to demonstrate against destructive dams,

celebrate victories and educate the public. By organizing activities on March 14. you can

increase awareness about your struggle and the international opposition to large dams.

(17)

Planning your campaign

1. Collect information

It is important to understand how the dam would impact your community and the river. You can

use field surveys to gather information from members of your community. NGOs, university

researchers and other groups may also be able to help you. Here are some questions to think

about:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

What villages and lands will be affected by the dam and reservoir?

How many people will have to move?

How many people will lose their fishing areas and farmlands?

What is the value of the land, crops, houses, and/or fish catch that they will lose?

What compensation or resettlement is being offered?

Who is developing the dam? Is it the government, a private company or both?

Who is paying for the dam?

2. What are your goals?

The next step to organizing your

campaign is to figure out your goals

and develop a strategy to achieve

your goals. Here are some things to

think about:

•

•

•

•

What are you trying to achieve?

Do you want to stop the dam?

Do you want better

compensation?

Do you want to have a say in

decisions about the dam that

affect your community?

Make sure your goals are shared by members of your community. Your goals can be translated

into demands for your campaign. For example: “Stop the Okavango Dam” or “More

compensation for Okavango communities!”

3. Who are your allies and who are your opponents?

Building alliances is one of the most important parts of a campaign strategy. Think about who

can help you in your struggle. Your success depends on how much support you can build within

your communities, with the general public and with other groups.

Think about who your opponents are. What are their strengths and weaknesses? What will they

do to oppose you? Opponents can include other community members, government officials,

dam-building companies and funders.

(18)

4. Who are your targets?

Think about who can give you what you want. Who is making decisions about the dam? It may

be people in your government. It may be a dam-building company. Or it may be a dam funder,

like a development bank. These are your targets. Which of your targets is easiest to influence?

If your government is not very open, it might be easier to influence the dam funder or the dam

builder.

5. What strategies will change the mind of your targets?

What will convince your targets to change their

minds and support your demands? Will protests

be effective? Will media reports change their

minds? Will action in your Parliament or

legislature be effective? Usually a combination of

actions is most successful. Make a timeline

listing actions. Make sure everyone understands

who is responsible for each action. This is your

campaign strategy.

6. What funding do you need for your campaign?

Every campaign needs resources, whether it is help with organizing marches and

demonstrations, a computer and access to email, a telephone, or printing of campaign

materials. Many groups rely on donations from members of their community. Other sources of

funding include foundations, aid agencies and other people in your country. If you need help

fundraising, try to contact some bigger NGOs in your country. They may have ideas for raising

money.

Discuss your campaign strategy together in your community and make sure that everyone

understands and agrees with it.

(19)

«►> Important strategies to fight dams

Some strategies can be effective at all stages of the dam-building process. The following gives

you some ideas about activities that you can do at all stages of your campaign.

Organize and mobilize

Organize and mobilize affected people

and the general public to support your

struggle. Your campaign success

depends on uniting many people.

Governments and dam builders will

often try to create conflict amongst

community members. By building the

strength and unity of your community

early on, it will be harder for dam

builders to divide you.

One way to mobilize people is to

create your own organization. You can

also link up with other organizations to form a network. Find out if there is a national network on

dams in your country. Organize meetings to plan your campaign strategy and discuss actions

to take. Create alliances with NGOs, academics, researchers, lawyers, and technical experts.

Organize marches, demonstrations, strikes, boycotts and blockades to bring attention to your

struggle. These activities are most successful if you target institutions that are making

decisions about the dam. Organize public meetings in towns and cities.

Distribute information

Produce leaflets, posters, reports

and other materials to raise

awareness about the dam and its

potential impacts on your

community. These materials can

be distributed to affected people,

the general public, NGOs around

the country and government

agencies. This is a good way to

publicize your demands.

(20)

Work with the media

Publicize your message using

radio, newspapers and television.

This will help put pressure on the

government and dam builders to

listen to your demands. Call

journalists that have written

about similar issues in the past

and tell them your stories.

Organize a press conference.

Invite the media to your activities.

Keep journalists informed about

your struggle. Ask NGOs and

other support groups to help you

identify different ways of

delivering your message.

Lobby your government

and funders

Meet with decision-makers to tell

them about your concerns.

Convince local and national

government officials, and members of Parliament or Congress to support your demands.

Organize letter-writing campaigns and petitions to target decision-makers in your government

and dam funders. If the dam is being funded by a private bank or a public development bank,

work with international NGOs to target these funders.

Take legal action

Sometimes legal action can be used to delay or halt dams, or to get better compensation for

affected communities. Find a lawyer and find out whether dam builders are breaking any laws.

Many big law firms will work for free for a good cause.

Propose alternatives!

Try to get experts to help you propose alternatives to the dam. (See Chapter 5 for more

information.)

(21)

Brazilians organize to stop Pilar Dam

In the 1990s, powerful foreign companies wanted to build a dam on the Piranga River in

Brazil’s Minas Gerais state. The dam would displace 133 farming families and destroy

fisheries. Thousands of people downstream would be affected by changing water levels in

the river.

Local residents, an NGO, university researchers and church groups formed an alliance to

fight the Pilar Dam. They worked together to find out what impacts the dam would have on

their lives. They read the companies’ studies and found many problems. They shared this

information with government officials who were also worried about dam’s environmental

impact.

The NGO and researchers explained the environmental studies to the community to prepare

them for a public hearing on the dam. They also helped farmers to compare their own

views of their land, livelihoods and resources with that presented in official studies.

The community was well organized for the public hearing. Children read poems about the

Piranga River and residents held up signs telling the company “Fora" (Get Out). Community

leaders made strong statements expressing their concerns. The pressure from local

residents, the criticism of the companies’ environmental impact studies, and the concerns

of government officials forced the companies to cancel the dam project.

When one of the companies tried to build a new dam in the area several years later, people

again said “NO.” They occupied the site where the company was taking measurements for

the dam. After 43 days, the company technicians left. The community is prepared to resist

again if necessary.

(22)

Thai villager research

For the past few years, people living along the

Salween River on the Thai-Burma border have

struggled against their governments’ plans to build

dams along the river. They decided to conduct

research using local knowledge to document how

they are using the river.

For 2 1/z years, Thai Karen ethnic people from 50

villages gathered data on fisheries, traditional fishing

gear, herbs, vegetable gardens and natural

resources. NGO staff and volunteers helped record

data and write the report, but community members

were the primary researchers. The villagers identified many fish, herbs and edible plants

along the river that they depend on for food. The villagers will use the research to prove how

important the river and forest is to their lives.

How to do your own research

Step 1: Organize a meeting with everyone who wants to be part of the research. Invite

people from as many affected villages as possible. Talk about all the ways you depend on

the river for your livelihoods and decide what you want to research.

Step 2: Divide into teams to conduct the research. The teams should include people who

are experts in the area that is being studied. For example, fishers should do the fish research,

and vegetable growers should do the riverbank garden research.

Step 3: Decide what method you want to use for your research. Here are some ideas:

Fisheries: Divide the river into zones. Assign a team of fishers to research each

zone. After every fish catch, collect a sample of species. Organize a meeting so

people can identify each species by its local name. Talk about their habitat, migration

patterns, size, weight and spawning patterns. If you have a camera, take a

photograph of each species that is caught. Put each photo into a book and write all

the information about the fish underneath the photo.

Riverbank Gardens: Divide the river into zones. In each zone, walk along the

riverbank and take measurements of each riverbank garden. Write down who owns

each garden, what each person grows in the garden, and how they use the

vegetables (for example, for eating or selling). If the vegetables are sold at the market,

write down how much money they are sold for.

Step 4: Record your findings. Decide how to use them to influence decision-makers.

(23)

What you can do at each stage of dam building

This section describes the three stages of dam building and specific actions you can take at

each stage. The three main stages of dam building are pre-construction, construction and

operation.

Stage 1: Pre-construction

Duration: 2 to 20 years or longer.

What happens during this

stage?

Before a dam is constructed, dam

builders develop plans and complete

many studies to see whether it is

possible to build the dam. They also

want to see what the dam’s impacts

might be. Most of the studies are

done by foreign companies.

1. Pre-Feasibility Study. This

study makes sure that the

Surveyors and drilling rigs are often the first signs that

dam can be built and

a dam is being planned in your area

operated. It determines

whether the site is suitable for a dam, estimates how much power or water can be

produced, and estimates the dam’s cost.

2. Feasibility Study and Detailed Design. This study looks at information necessary to

build the dam, such as climate, geology, how much water is in the river, etc. If you see

strangers in the area taking measurements and drilling in the ground, then they are

probably doing the feasibility study.

3. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). The EIA is supposed to look at the

environmental impacts of the dam. It is also supposed to suggest mitigation measures

for the environmental problems the dam will cause. ElAs usually say that most impacts

can be mitigated and the dam should be built.

4.

Resettlement Plan/Social Development Plan. This includes plans for resettling

people who live in the reservoir area. It also includes plans for compensating other

affected people. Affected people living downstream of the dam are often left out of this

plan.

Once these studies are done, dam builders meet with governments and banks to try to get

funding for the dam’s construction.

(24)

What can you do at this stage?

This is the best time to influence the dam project. If you think the dam will destroy your

community, then try to stop the dam. Learn about what rights you have under your local laws.

Demand that the government organize public hearings so you can debate who benefits and who

loses from the dam. Try to take legal action to stop the dam. Work with experts to develop better

alternatives or compensation plans and publicize these.

Even if your campaign to stop a dam is successful, the government may try to build it again

later. Building strong alliances is important for your long-term struggle.

Review dam studies

Demand that the studies are released to the public. If you are able to get copies of the studies,

find experts to review them and publish their reviews. Expert reviews can identify problems with

the studies and predict what might go wrong if the dam is built.

Do your own studies

Often dams are built without studies that show how people depend on rivers. If the dam is built,

people are less likely to receive full compensation because there is no record of what they have

lost. It is important to record how your community depends on the river. These field surveys can

also highlight the damage the dam might cause. Thai villagers have developed a research

method for doing this called “Thai Villager Research”. (See box on page 23.)

Target the funders

Find out who is likely to fund the

dam. If the funders are from

another country, contact NGOs

in those countries to ask them to

support your campaign. See the

list of contacts at the end of this

guide.

"Don t worry

about what it

says. Just sign

here. Trust me.

Demand legal agreements

If you decide to move, make

sure that you sign a legal

agreement that contains

everything promised to you.

Make sure you understand the

agreement. Do not sign anything

that you do not understand. The

government and dam builders

will often tell you that you will get

new houses and better land, but

this is rarely true

Do not sign anything you do not understand!

(25)

«£> Stage 2: Construction

Duration: 5 to 15 years. Construction often takes longer than predicted. Sometimes this is

because of technical difficulties, and sometimes it is because of corruption.

What happens during this stage?

The construction process for a dam is usually like this:

5. Future reservoir:

1. Cofferdam:

This smaller dam is built to change the

flow of the river. This is done to make

sure the construction area for the main

dam is not covered with water.

Once the dam is built, the

reservoir is filled. It

sometimes takes one year

or more for the reservoir to

fill up.

4. Main dam construction:

It can take several years for

the main dam to be built.

2. Downstream coffer dam:

3. Diversion channel:

Sometimes they have to build a

dam downstream to prevent the river

water from backing up and flooding

the main dam construction area.

he river flows through

this channel while the

dam is being built.

Sometimes a tunnel is

built through the side

of the mountain to

allow the river to flow.

What can you do at this stage?

Your campaign can still be successful even if dam construction has already started. You might

be able to stop construction, get more compensation, or make the project better. It is important

to continue your struggle.

Organize demonstrations

At this stage, some groups try to stop construction from taking place by organizing blockades

and other forms of non-violent direct action. If you cannot do this, then monitor construction

and resettlement. If the dam builder or government does not do what they said they would do,

organize protests and other actions to demand that they keep their promises.

Work with international NGOs

If the dam is funded by a public development bank, work with international NGOs to make sure

the funder receives information about problems with the dam. Sometimes this funder can put

pressure on the dam builder if they are doing construction or resettlement badly. If things are

really bad, the funder may stop giving money until things improve.

(26)

Stage 3: Operation

Duration: Around 50 years (sometimes more, sometimes less).

What happens during this

stage?

After dams are built, they start to

age. Some reservoirs quickly fill

with sediment. Some dams may

become unsafe or even break.

Once a dam has reached the end

of its lifespan, it needs to be fixed

up or decommissioned. Many

groups around the world are

demanding that dams be

decommissioned because of their

impacts on people and rivers.

What can you do at this stage?

Demand reparations

Even if the dam is built, some companies and governments may still have a legal obligation to

provide compensation. You should research whether this applies to you.

Many people around the world who have been affected by dams are demanding reparations, or

compensation for past damages. They are demanding that the agencies that built the dam

(governments, banks and companies) take responsibility for the impacts of the dam and pay

compensation to affected communities. Some have been successful. (See box on next page.)

Demand changes in dam operation

You can also demand changes in dam operation to help the river flow more naturally again. This

is called dam re-operation. This can involve changing the amount of electricity generated at

different times of the day. Or it could mean releasing more water downstream of the dam. Many

groups around the world are fighting for dams to be re-operated.

(27)

Demanding reparations in Guatemala

While Guatemala was in the middle

of a civil war, the government built the

Chixoy Dam in Maya Achi territory. The

Maya Achi are indigenous peoples.

After some people refused to move for

the dam, paramilitary forces killed

about 400 people in 1982. More than

3,500 people were forced off their

lands. Thousands more lost land and

their livelihoods.

For years, survivors lived in extreme

poverty. But they never gave up their

call for justice. Affected people are

now demanding reparations for their

social, physical and economic losses.

The affected communities, together

with some NGOs and a researcher,

produced a study that documents the

dam’s impact on the environment, natural resources, poverty and food supply. This study

has helped to show what the Maya Achi lost and why they deserve reparations.

In November 2004, the communities organized a big protest at the dam site. After occupying

the dam for two days, the government agreed to form a commission to negotiate reparations.

The commission held its first meeting in December 2005.

Says Cristobal Osorio Sanchez, one of the massacre survivors, ‘’Reparations allow us to

restore our dignity and respect for our culture and our rights. Reparations mean we will be

able to provide for our families and live well again, to develop projects to benefit the community

and to increase the capacity of the people. Reparations will help people feel there is a

sense of future. To feel good about life.

• If you have been affected by a

dam, what have you lost since the

dam was built?

• What kind of compensation would

help repair the damage to your

communities?

• Who do you think should pay

reparations to you? The

government? Dam funders?

• What can you do to pressure

those responsible to pay

reparations?

Questions for discussion:

(28)

CHAPTER 5

Alternative to Large Dams

Better options exist to provide water, power and flood protection to people. These options are

often cheaper, faster to build and less harmful for people and the environment than large dams.

Around the world, dam-affected communities and NGOs have gathered information about

alternatives to large dams. They have used this information to pressure their governments to

support better alternatives. Their efforts have helped stop the construction of destructive and

unnecessary dams.

In this chapter, we discuss some alternatives to dams and highlight successful actions

communities and NGOs have taken to support better alternatives. We hope this chapter gives

you ideas about alternatives you can push for in your campaigns. Because every region has

different needs, you will need to figure out the best options for your region.

Alternatives for energy

There are many ways that governments can provide

energy to their citizens. This includes improving existing

power plants and transmission lines, building new energy

sources, and reducing energy demand.

Reduce demand

Governments can reduce energy demand by encouraging

factories, businesses and people living in cities to use

energy more efficiently. This costs less and is better for

the environment than building new power plants and new

dams.

Some tactics for saving energy include helping people to

pay for machines and lights bulbs that use less electricity.

Governments can make companies and citizens that use

electricity-hungry machines pay more taxes.

Compact fluorescent light

bulbs reduce energy use.

Governments can also encourage people and industries to use electricity during different times

of the day. Then fewer power plants and dams need to be built.

(29)

Improve existing dams and transmission lines

Transmission lines carry energy from power plants to

people, cities and factories. In many countries, poor

quality transmission lines can waste a lot of power.

Energy can often be saved by repairing transmission

lines.

Existing dams or power plants can also be improved.

By cleaning plants, removing sediment and making

other technical improvements, power plants can

produce more electricity. These improvements can

cost less and take less time to do than building new power plants.

Build better energy sources

Here are some ways to produce energy that are less

damaging to the environment and communities than big

dams. Many of these options can be used to provide power

to big cities and factories, or to rural villages.

Small hydropower

Small hydropower dams are usually only a few meters tall.

They can be built of earth, stone or wood. Small dams often

do not have reservoirs, so they usually do not displace

people. The flow of the river does not change much. Very

small micro-hydro projects often do not involve a dam. They

divert some water from rivers to generate power.

Small hydropower projects can be set up and managed by

local villagers. In China, India and Nepal, thousands of small

hydro projects supply power to villages and towns.

Biomass energy

In many countries, biomass is a very common energy

resource. Biomass includes all waste material that comes

from plants and animals. Animal and agricultural waste is

used to operate stoves, to produce gas and to heat

buildings.

Biomass can also be used on a large scale. In countries

where sugarcane is produced, companies have started to

burn the stalks of sugarcane to generate electricity. Rice

husks and wood waste can also be used.

(30)

Solar power

Ci"—

4

Solar panels can be put on rooftops to collect the energy of the

sun and use it to heat water or produce electricity. Larger panels

collect more solar heat and produce more energy.

Wind power

c

Wind power is less harmful to the environment than large dams.

In many European countries, such as Germany and Spain, a lot

of energy is produced by wind turbines. Countries such as India,

China, South Africa and Brazil, are now building many wind

turbines to generate clean energy.

Geothermal power

Geothermal power uses heat from inside the earth to produce

energy. This heat warms underground reservoirs of water and

steam. Wells can be drilled to bring the hot geothermal water to

the earth’s surface. This liquid can then be used to make

electricity at power plants. The Philippines and El Salvador

generate about 25 percent of their electricity from geothermal

sources.

NGOs identify better alternatives in Uganda

The Ugandan government and the World Bank

have long said the Bujagali Dam is needed to meet

Uganda’s energy needs. But NGOs in Uganda

wanted to look for alternatives that would be less

environmentally damaging and better for the

people. So they started to investigate large-scale

alternatives.

In April 2003, the National Association of

Professional Environmentalists (NAPE), a

Ugandan NGO, organized a major conference on geothermal energy, the alternative

considered to hold the best promise for Uganda. Geothermal experts from around the world,

government officials, environmental groups and the general public attended the meeting.

After the conference, the Ugandan Ministry of Energy formed a team to study energy

alternatives for the country. Thanks to the efforts of NAPE, hydropower is no longer seen as

the only energy option for Uganda. Better, cheaper and cleaner options, such as geothermal

energy, are now being considered.

Alternatives for water

Rivers and wetlands around the world have been dammed and drained for water supply. But a

lot of this water is wasted by inefficient irrigation and water distribution systems that leak.

People who live in cities also often waste water. If water were managed better, there would be

enough to meet everyone's needs. Below are some ideas that can help.

Reduce demand

Large-scale agriculture uses and wastes a lot of freshwater. Irrigation systems for large farms

often put more water on fields than plants need. The extra water destroys the soil. Other types

of irrigation systems can be used to save water. Drip irrigation uses water more efficiently

because it delivers water directly to the roots of the plants. Drip irrigation saves water and is

better for plants and soil.

Large-scale farmers and big farming companies sometimes grow crops in dry areas that need

a lot of water, such as rice and sugarcane. Water can be saved by encouraging large-scale

farmers and companies to grow crops that do not need so much water.

Collect rainwater

Rainwater harvesting is a cheap and effective way to improve communities’ access to water.

People can put tanks next to their houses and collect rainwater that falls off their rooftops. Large

earth jars can also be used to collect rainwater for household use.

For farming, people often build small dams to collect rainwater as it runs

down hills. Water soaks into the ground. Wells can be built to access the

water. Another method is to build small dams and canals

(32)

Harvesting rain, changing lives

In 1986, the Alwar district in

Rajasthan, India, was like a desert.

People did not have enough water

for their homes and fields. At that

time, the group Tarun Bharat

Sangh (TBS) was formed to

increase the water available for

people and agriculture. The

founders of TBS remembered that

people in Rajasthan used to

collect rainwater. When TBS

started their work, the structures

for collecting rainwater had been

forgotten and nobody used them

any longer.

TBS remembered the forgotten wisdom of rainwater harvesting and rebuilt the small

earth dams that their ancestors had built across rivers to capture and conserve

rainwater. In Rajasthan, there are now more than 10,000 small dams and earth

embankments that collect water for more than 1,000 villages. Thanks to the small dams

and embankments, the groundwater level in the area is higher now and rivers that used

to be dry carry water year-round. This has transformed the lives of around 700,000

people who have better access to water for household use, livestock and crops.

“Generations before us never had the good fortune we have,” says Lachmabai, an

elderly woman from Mandalwas village in Rajasthan. “Because of the water we are

happy, our cattle are happy, and the wildlife is happy. Our crop yields have gone up, our

forest is green, we have firewood, fodder for our cattle, and we have water in our wells.”

Questions for discussion:

•

•

How does this story relate to your community?

Are there traditional systems of rainwater

collection in your area?

•

Would a revival of those systems increase

your access to water?

•

If you were able to get large numbers of

people to supply their own water, would this

help you stop a dam project?

(33)

Alternatives for flood management

Large dams are sometimes built to control floods. However, when there is a really big flood

large dams can make flooding damages worse. There are many ways to reduce floods and

make them less destructive. This includes protecting watersheds and creating flood warning

systems.

Protect and restore watersheds

One of the best ways to reduce damage from floods is to protect and restore watershed areas.

Healthy wetlands, floodplains and forests prevent flooding by holding water. They are like a

sponge. Trees slow the speed of floodwaters and distribute water more slowly over the

floodplain. Wetlands soak up water during storms and whenever water levels are high. When

water levels are low, wetlands slowly release water.

River turned into a tunnel

and straightened. This

increases water speed

during floods.

Forests cut down,

making erosion and

flooding worse.

Houses and

factories built

very close to

river are more

likely to be

flooded.

Wetlands

destroyed to

build houses

and

businesses.

Bad Watershed Management

(34)

Today, many wetlands, floodplains and forests have been destroyed for the construction of

roads, houses and industries. This has increased flooding damages. For better flood control,

these natural resources must be protected. If they have been destroyed, they should be

restored.

Create flood warning systems

Governments can invest in flood warning systems so people know in advance when a flood is

coming. This can save lives and reduce flood damages. Early warning systems tell people living

along the river when flooding is about to occur. This could involve having loudspeakers in towns

and having emergency plans for what to do if a flood occurs. Other systems allow people to

keep track of how much water is in the river. When the water levels rise above a certain level,

people know that flooding is likely.

Houses and

factories built

away from

edge of river.

Wetlands

along

riverbanks

absorb

floodwaters

and protect

buildings from

being flooded.

Good Watershed Management

(35)

Conclusion

We hope this action guide gives you tools and information to help you in your struggle against

destructive dams. We hope the successes of other communities inspire you as you defend

your rights and your livelihood. You are not alone in your struggle.

As dam-affected people and NGOs said in 1997:

“We are strong, diverse and united and our cause is just. We have stopped

destructive dams and have forced dam builders to respect our rights. We have

stopped dams in the past, and we will stop more in the future.”

- Declaration from the ‘‘First International Meeting of People Affected by Dams" in

Curitiba, Brazil in March 14, 1997,

These words have proven true. Together, we can stop destructive dams and defend people’s

rights. Together, we can meet people’s energy and water needs without hurting communities

and the environment.

Together, we can build a better future.

(36)

Regional Contacts

International Rivers Network

1847 Berkeley Way

Berkeley CA 94703, USA

Tel: + 1 510 848 1155

Email: info@irn.org

Web: www.irn.org

Provides support to local communities and

NGOs who are fighting destructive dams.

Africa

African Rivers Network

C/- Mr. Frank Muramuzi

National Association of Professional

Environmentalists (NAPE), Uganda

P.O. Box 29909, Kampala, Uganda

Phone: + 256 77 492362

Email: nape@nape.or.ug

Web: www.nape.or.ug

Network of communities and NGOs

advocating for sustainable use of African

water resources.

Web: www.emg.org.za

Provides support to organizations and

communities working to stop dams and

protect rivers in Africa.

Europe

European Rivers Network

8 rue Crozatier,

43000 Le Puy, France

Phone: + 33 471 02 08 14

Email: info@rivernet.org

Web: www.ern.org

Network of European groups,

organizations and people working to

protect Europe's rivers.

Latin America

Mr. Hope Ogbeide

Society for Water and Public Health

Protection (SWAPHEP), Nigeria

248 Uselu-Lagos Road, Ugbouto, Benin City,

Nigeria

Phone: + 234 803 742 4999

Email: swaphep@yahoo.com

SWAPHEP works to increase local peoples’

access to clean water and to promote the

sustainable management of freshwater

resources in Nigeria.

Ms. Liane Greeff

Environmental Monitoring Group, South Africa

PO Box 13378

7705 Mowbray, South Africa

Tel: + 27 21 448 2881

Email: rivers@kingsley.co.za

(37)

MAB - Movimento dos Atingidos por

Barragens

HIGS Quadra 705, Asa Sul,

Bloco K, Casa 11

Brasilia/DF, Brasil CEP: 70350-711

Phone: + 55 61 3242 8535

Email: mab@mabnacional.org.br

Web: www.mabnacional.org.br

Brazil’s national movement of damaffected people.

Ms. Elba Stancich

Taller Ecologista

Casilla de Correo 441

CP 2000 - Rosario, Santa Fe,

Argentina

Phone: +54 341 426 1475

E-mail: info@taller.org.ar

Web: www.taller.org.ar

Helps coordinate PEDLAR: the Latin

American Network Against Dams, and for

Rivers, their Communities, and Water.

Mr. Gustavo Castro Soto

Edupaz

Periferico Pte.17-8B, Cda.Cuatro Caminos

Col. San Martin; 29240

San Cristobal de Las Casas

Chiapas, Mexico

Phone: + 52 967 631 5474

E-mail: guscastro@laneta.apc.org

Helps coordinate the Mesoamerican

Movement Against Dams.

Phone: +92 51 228 2481

Email: amjad.nazeer@sungi.org

Web: www.sungi.org

Helps communities defend their rights and

get benefits from development projects in

Pakistan.

East and Southeast Asia

Rivers Watch East and Southeast Asia

C/- Joan Carling, RWESA Coordinator

Cordillera People’s Alliance

P.O. Box 975

2600 Baguio City, Philippines

Phone: +63 74 442 2115

Email: joan@cpaphils.org

Web: www.rwesa.org

Network of NGOs and dam-affected people

in East and Southeast Asia working to stop

destructive river development projects.

South Asia

Mr. Himanshu Thakkar

South Asian Network on Dams, Rivers and

People (SANDRP)

86-D, AD block, Shalimar Bagh,

Delhi 110 088, India

Phone: +91 11 2748 4654

Email: ht.sandrp@gmail.com

Web: www.sandrp.in

Shares information on dam-building in India

and provides contacts for dam-fighters in

India.

Ms. Pianporn Deetes

Living Rivers Siam

78 Moo 10, Suthep Road,

Tambol Suthep

Muang Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand

Phone: +66 53 278 334

Email: pai@chmai2.loxinfo.co.th

Web: www.searin.org

Supports rights of local communities

to their resources and opposes threats to

rivers and ecosystems in mainland

Southeast Asia.

Gopal Siwakoti 'Chintan'

Water and Energy Users Federation-Nepal

G.P.O Box 2125

60 New Plaza Marga

Kathmandu, Nepal

Phone: +977 1 442 9741

Email: gopalchintan@gmail.com

Web: www.wafed-nepal.org

National network of water and energy

project-affected people and local concerned

groups in Nepal. Also helps coordinate

South Asian network of groups working on

dam and river issues.

Friends of the Earth Japan

3-17-24-2F Majiro Toshima-ku

Tokyo 171 -0031, Japan

Phone: +81 3 3951 1081

Email: finance@foejapan.org

Web: www.foejapan.org

Monitors the policies and projects of the

Japan Bank for International Cooperation

(JBIG).

Mr. Amjad Nazeer

Sungi Development Foundation

H.7-A, Street 10, F-8/3

Islamabad, Pakistan

(38)

Indian Social Action Forum (INSAF) is a forum of over 600 trade unions,

peoples movements, NGOs and grassroots groups engaged in resisting

globalization, combating communalism and defending democracy.

INSAF is a democratically governed organization believing in complete

transparency and accountable to its member organizations.

Actions including campaigns, agitations, meetings and publications are

earned out by 15 state units and the national secretariat in New Delhi.

Focussed campaigns and agitations include right to water ( against water

privatization ); food sovereignty right; against international financial

institutions like the World Bank, IMF, WTO and ADB;

communal fascism; armed forces act; etc.

INSAF is actively involved in international campaigns and

networks like the Jubilee South - Asia Pacific Movement on

Debt and Development, reclaiming public water, etc.

For more details, INSAF perspective, publications and contacts:

Visit: www.insafindia.org

INSAF

INDIAN SOCIAL ACTION FORUM

Resist Globalization, Combat Communalism, Defend Democracy

-*****■

-*•****■

International Rivers Network

INSAF

linking Human Rights and Environmental Protection

- ,, ,

Indian Social Action Forum

Resist globllsation. Combat Communalism. Defend Demoer00*

- Media

10339.pdf

10339.pdf

Position: 1903 (6 views)