CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

Item

- Title

- CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

- extracted text

-

DILEEP KUMAR A D

April 2015

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT

USE IN INDIA

1 5 U-A

OM C

JS oPH

CONTACT

PAN INDIA

Pesticide Action Network (PAN) India

Vilangottil House

House No. 104

Prayaga, Warriam Road

Thalore P.O. Thrissur.

Kerala, India

PIN-680306

admin@pan-india.org

www.pan-india.org

I

SOCHARA

Community Health

Library and Information Centre (CLIC)

Community Health Cell

85/2, 1st Main, Maruthi Nagar,

Madiwala, Bengaluru - 560 068.

Tel : 080-25531518

email: clic@sochara.org / chc@sochara.org

www.sochara.org

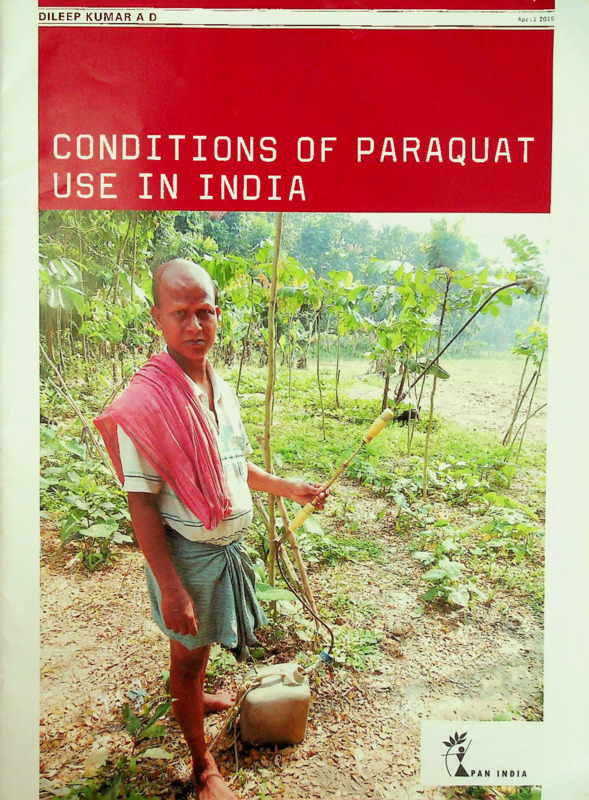

Frontpage A farmer with a hand operated sprayer (West Bengal). Often paraquat and other pesticides are applied

with this kind of sprayer.

IMPRINT Author Dileep Kumar A. D. I Edited by Sreedevi Lakshmikutty I Photos Dileep Kumar A. D.: Frontpage,

page 17, 25; Kondala Reddy: page 5, 30; IUF: page 7, 9, 29 I Design Karin Hutter

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 3

FOREWORD BY THE EDITORS

Agriculture is the most important sector of the Indian

economy providing employment and livelihood to nearly

70 % of the total population. The industrialization of agri

culture has favoured the use of plenty of agrochemicals

including fertilisers, pesticides, micro nutrients and plant

growth regulators in the agricultural fields. According to

recent data from the Central Insecticide Board and Regis

tration Committee (CIBRC), 256 pesticides are registered

for use in India (as of December 31, 2014). Among this,

nearly half are insecticides, followed by fungicides and

herbicides. According to the CIBRC list of registered pes

ticides in India (dated October 1, 2014). 54 herbicides and

13 combination herbicides are approved for use in the

country.

Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal are the

states where the herbicide consumption is high in India.

Though herbicides were widely used in the plantation sec

tor for a long lime, now it is becoming widely accepted in

most agricultural landscapes such as horticulture, cereals,

vegetables and floriculture. About three fourths of the

available herbicides in India are still used in plantation

crops. At present herbicide use is common in major crops

like sugarcane, wheat, rice, maize and vegetables. Data

from a few studies on herbicide consumption shows that

they are being used in approximately 20 million hectares,

which constitutes about 10 per cent of the total cropped

area. In general, herbicides are being used where the eco

nomic stakes for farmers are high, and/or where choices

are limited. In 2013-14 (as on December 18, 2014), the

volume of herbicides consumed in India was 5000 metric

tonne technical grade.

The implications of using pesticides, including herbi

cides, are increasingly being experienced in the form of

hazardous health effects. Several studies across the globe

reveal that pesticides can cause severe health hazards in

cluding infertility and sub-fertility, abnormal develop

ment, birth defects, hormonal disorders, immune suppres

sion, diminished intelligence and cancers.

Herbicides are extremely toxic to other organisms and

soil life. Persistence in soil, pollution of environment and

ground water, toxic residues in food, feed, fodder, develop

ment of herbicide resistant weeds and adverse effect on

non-target organisms and biodiversity, etc. are other nega

tive impacts of herbicide use. The potential of herbicides

contaminating ground water has gained considerable at

tention in recent years.

Butachlor, 2,4-D, isoproturon, glyphosate, anilophos,

paraquat dichloride, pretilachlor, and atrazin are the most

commonly used herbicides in India. Among these, para

quat dichloride has received global attention over the past

couple of years due to its high acute toxicity and ability to

cause severe short term and long term health effects among

users.

For many years, International Union of Food and Al

lied Workers (IUF), Pesticide Action Network and the

Berne Declaration have been asking governments for a

global ban on paraquat and also calling on industry to stop

production and sale of this highly hazardous pesticide.

The product is already banned in many countries all over

the world, including African and Asian nations, the Euro

pean Union and Switzerland, the home country of Syngen

ta, the main producer of paraquat. In countries like the

United States and China the use of paraquat is restricted.

Nevertheless, paraquat is still one of the most used herbi

cides globally, especially in developing countries, where

its use leads to countless poisoning episodes of workers

and farmers.

This led us to do a study on Conditions of Paraquat

Use in India. We did the study across six states where

paraquat use is high. The objective was to understand and

document the use of paraquat, the reasons thereof, the

knowledge about its impacts among farmers and workers.

the use of personal protective measures and the adherence

to regulations by the users. The study has established that

the use of paraquat in India clearly violates the Interna

tional Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management of the

World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Food and Agri

culture Organisation (F/\O). The manufacturers and the

state have a responsibility to change this untenable situa

tion. The Government of India also needs to act and en

sure that the use of herbicides and pesticides is within the

legal frame work of India and international commitments

of India.

We believe that this report shows the need for national

level policy decisions on the regulation of pesticides and

in this case on paraquat specifically. Regulations should be

based on evaluation and assessment of impact of the in

trinsic hazards of and anticipated exposure of users to

these hazardous chemicals.

The editors would like to thank the main author.

Dileep Kumar A D. the team of PAN India and all the others

who have contributed to this study. The team has collected

a lot of new information about the use of paraquat in India.

We believe that this report will be helpful for the decision

makers in India to align Indian regulations with interna

tional policies, so that harm to people and the planet can

be minimized, if not removed completely.

C. Jayaknmar and Dr. D. Narasimha Reddv

(Pesticide Action Network India)

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 4

TABLE OF CONTENT

Foreword by the editors 3

Acknowledgment 5

Executive summary 6

Policy recommendation 7

1.

INTRODUCTION

2.

OBJECTIVES

3.

METHODOLOGY

4.

STUDY AREA

5.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

LIST OF TABLES

1

Recommendation of paraquat dichloride by state

agriculture departments and other institutions 14

3 Variations in approved use and recommended use of

paraquat dichloride in India 15

4 Percentage of paraquat dichloride to the total herbicide

consumption 16

2

8

9

10

5

11

State wise consumption data for paraquat dichloride

obtained through RTI Act 17

7 Classification of respondents 18

12

Legal framework

5.2.

5.3.

Consumption of paraquat dichloride in India

Findings of the field study 18

8

9

12

16

5.3.1. Information and awareness on paraquat use and

safety measures 22

5.3.2. Information and awareness

23

1

Agricultural and environmental impacts

27

2

3

4

5

6

Report based on information obtained from agriculture

extension officers and retailers 28

5.5. Paraquat use in tea plantations 29

5.6. Other weed management methods 29

6.

7.

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

30

31

Dispersal of paraquat with other materials 19

Quantity of paraquat used and the addition of other

materials 20

LIST OF CHARTS

on personal protective equipments (PPE)

5.3.3. Use of safety measures 24

5.3.4. Poisoning and health effects 26

5.3.5. Disposal of containers 27

5.4.

Commercial names of paraquat dichloride reported

from field 16

6

5.1.

5.3.6.

Details on the approved use of paraquat dichloride 24 SL

in India as on October 2014 13

7

8

9

10

11

12

Consumption of paraquat dichloride and total

herbicide consumption in India 16

Reasons for using paraquat 19

Type of sprayers used-farmers 21

Working in sprayed fields-farmers 21

Source of information and advice on paraquat use 22

Responses to questions related to label and

instructions among farmers 23

Responses regarding training on use of PPE and

pesticide application 24

Use of Personal Protective Equipment 24

Personal protective equipment used by workers 25

Health effects reported by farmers 26

Health effects reported by farm workers 27

Container disposal method-farmers 27

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

PAN India is grateful to Thanal for facilitating, supporting

and guiding the research. We thank Berne declaration. Pes

ticide Action Network Asia and the Pacific (PAN AP) and

IUF (International Union of Food and Allied Workers) for

their support and partnering in this effort to bring knowl

edge for decision making.

I am indebted to Sri. C.Jayakumar and Dr. Narasimha

Reddy (Directors. Pesticide Action Network India) for pro

viding me the opportunity to take up this study; their sup

port, encouragement and guidance for the successful com

pletion of this work. 1 would like to express my gratitude

for the effort taken by Ms. Usha. Dr Sharadini Rath and Dr

Adithya Pradyumna (members, steering committee of PAN

India) for their guidance, suggestions and cooperation which

helped us to take the work forward.

1 would like to express sincere thanks to Mr. Francois

Mcienberg (Campaign Diretor, Berne Dcclarartion), Ms. Sarojcni Rengam (Executive Director. PAN AP), Ms. Sue

Longely (IUF International), for conceiving the research

idea, support and guidance throughout the study.

I owe my deep sense of gratitude to Dr P. K. Prasadan

Collecting data from Pesticide retailer in Telagana state.

(Associate Professor. Research department of Zoology.

Mary Matha zXrts and Science College. Wayanad. Kerala)

for his support, guidance in research and motivation

throughout the work. I express sincere thanks to Ms.

Sreedevi Lakshmikutty for editing the report. I thank Adv.

Harish Vasudevan for his help and advice to collect data

from various Government sources through the provisions

of the Right To Information Act.

Special thanks to Dr. Anupam Paul. Dr. Namita Lungchang. Dr. Sheelawati Monlai. Ms. Shruti Patidar. Ms. Timitha Mungyak, Ms. Konchiva Namchoom. Mr. Ashokdas. Mr.

Alauddin Ahamed, Mr. Amitabh Kumar Singh. Mr. Budhi

Singh and Mr. Kondala Reddy for facilitating and supporting

to gather field data. I thank all the respondents for providing

the information, their patience and co-operation during the

data collection. 1 also thank Ms. T. Chitra for compiling sec

ondary data and Ms. Nihala for helping with data analysis.

I am grateful to my colleagues and friends for their con

stant support and encouragement.

Dileep Kumar A D.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The report presents the findings of a field study conducted

to document the use of paraquat dichloride in India and its

health impacts. Paraquat dichloride has high acute toxici

ty. Pesticide Action Network (PAN) International includes

paraquat dichloridc in its list of highly hazardous pesti

cides. Paraquat dichloride 24 % SL is the only formulation

registered in India and is approved for weed control in

nine crops.

The field study was carried out in eleven study areas

across six States (Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh. As

sam. Madhya Pradesh. Telangana and West Bengal) in In

dia, where paraquat use was observed in a preliminary ex

ploration in 20 areas across 10 States. The field data was

collected through purposive sampling with the help of

questionnaires from farmers and farm workers including

paraquat/pesticide applicators. In addition agriculture ex

tension officers as well as pesticide retailers were also in

terviewed. Secondary data was collected through applica

tions under the Right to Information (RTI) Act from State

Agriculture Departments as well as from the web sites of

respective departments or institutions.

Farmers use paraquat in their fields for controlling

weeds. A total of 14 commercial names of paraquat dichlo

ride have been found to be sold in the study sites. It is be

ing used in about 25 crops (in the study area) including

cereals, pulses, oil seeds, vegetables and cash crops while

the Central Insecticide Board & Registration Committee

(CIBRC) has approved its use in only nine crops. Signifi

cant variation was noted between the use approved by CI

BRC and the recommendations by the various State agri

culture departments and commodity boards such as the

coffee board. Further, manufacturers of paraquat have rec

ommended the use of paraquat in crops not approved by

the CIBRC. Syngenta, for instance, has recommended the

use of paraquat on 12 crops. Recommendations beyond

what is approved by the CIBRC is a violation of the Indian

Insecticides Act.

Farmers buy and use paraquat in an unsafe manner. It

was found that paraquat is sold in plastic carry bags to

farmers who demand 100ml or 200ml of the product. Nei

ther the retailers recommend personal protective measures

while handling paraquat nor do the farmers adopt them.

Particularly, when it is sold in plastic carry bags the risk of

exposure and poisoning is higher through spillage, inhala

tion as well as contact.

A considerable proportion of the respondents said that

they neither read nor follow the instructions on the label of

the paraquat containers, many of the respondents includ

ing farmers and agricultural workers reported that the font

size of instructions given in the leaflet is too small to read

or do not understand what is written. Ninety percent of the

respondents reported that they get information and advice

either from pesticide retailers or agents of distributors.

Awareness and training about how to use paraquat as

well as other pesticides and taking personal protective

measures is lacking among most of the respondents, which

included farmers and agricultural workers.

Neither proper information nor training on the use of

paraquat and personal protective equipment (PPE) are pro

vided by agriculture offices or pesticide retailers. There

fore use of paraquat is occurring under unsafe conditions.

None of the respondents were using the recommended

protective equipment. Seventy six percent of the respon

dents reported that they are not using any protective mea

sures while handling paraquat, only 24% of the respon

dents reported that they use some sort of protective

measures among the following-cap. gloves, mask or face

cover, full sleeved shirt, trousers and shoes. Eighty six per

cent of the respondents reported that the sprayers they

used leaked sometimes, and most said that they did not get

it repaired immediately. Paraquat is applied mostly before

planting and for controlling weeds in standing crops. It is

applied on weeds along the inter rows, ridges, furrows as

well as field bunds and boundaries of crops. Twenty six

percent of the respondents reported that they disperse

paraquat mixed with fertilizers, sand and common salt in

their fields. All the respondents spray paraquat on weeds

and 18% said they mix shampoo, salt, urea or kerosene,

2,4-D etc. to enhance the efficiency of the herbicide. Fifty

four percent of the respondents reported that thej' contin

ue to work in sprayed fields or enter a sprayed field imme

diately after spraying, for work, without wearing protec

tive equipment. Most respondents reported that they

dispose containers of paraquat by throwing them away,

while some reported that they bury or burn them, some

others reported selling them to scrap dealers and a few re

spondents said that they use the containers in toilets.

Farmers and workers were aware that paraquat is acutely

toxic, but because of labour problems they felt compelled to

use these chemicals. Lack of skilled labourers, non availabil

ity of labourers during critical periods of work, increased la

bour cost etc. were the major reasons reported for using para

quat. In addition, farmers claimed that paraquat is cheaper

and weeds can be controlled with lesser effort. Some respon

dents reported that they occasionally do manual weeding.

The farmers and workers reported numerous adverse

health effects caused by paraquat such as irritation, itch

ing, headache, vomiting, burning sensation, breathing dif

ficulty. muscle pain, abdominal discomfort, lethargy, skin

allergj’ and colour change, tiredness, nausea, giddiness,

fever, eye burn, dizziness, diarrhoea, throat drying, shiver

ing, sneezing and change in heart beat rate. Some respoi:

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 7

POLICY

RECOMMENDATION

dents reported that domestic animals were also adversely

impacted by paraquat (death of a cow and a goat after graz

ing in paraquat sprayed fields; unconsciousness, stomach

enlargement, diarrhoea and tiredness among goats and

cows after grazing; hens and ducks not taking food for a

couple of days after foraging in paraquat sprayed fields).

The actual practices at field level indicate the lack of an

effective regulatory and monitoring system. And because

of this, misuse, unsafe use and violations are happening in

the country with regard to paraquat use.

WE THEREFORE STRONGLY RECOMMEND THAT,

> The Government of India and State government author

ities immediately stop the violations of the Indian In

secticides Act, and enforce the prohibition of paraquat

use in crops where the use is not approved.

> The government urgently addresses the issues and take

necessary steps towards a progressive ban of paraquat in

India in a lime bound manner.

> The government convenes a national working group for

coming up with a package of practices for non chemical

approaches, options and methods for weed management.

THE STUDY FINDS,

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

Significant variations between the crops on which the use

of paraquat dichloride is approved by the Central Insecticide

Board and Registration Committee (CIBRC) and the crops

recommended by State Agriculture Departments or Agricul

ture Universities as well as commodity boards.

Paraquat dichloride is being used for 25 crops in India,

whereas it is approved for use in only nine crops by

the Central Insecticide Board and Registration Committee.

This is in violation of the Indian Insecticides Act.

The manufacturers have recommended the use of paraquat

for crops other than those approved by the CIBRC. This is

clearly illegal and a violation of the Indian Insecticides

Act by the manufacturers. CIBRC should take action against

manufacturers and ensure immediate cessation of these

illegal recommendations.

Often farmers and workers do not read or understand the

label on the paraquat container and instruction leaflet

properly. They normally follow oral instructions of dealers

and retailers and their field staff.

In villages, retailers sell paraquat in plastic carry bags and

refill bottles. Again this is a violation of the Insecticides Act

and an illegal activity and a gross failure of regulation.

Majority of the farmers and workers are not trained in the use

of paraquat, do not have access to information about the use

of paraquat dichloride, are not aware of appropriate safety

instructions and do not use personal protective equipments.

Paraquat is mixed with some other old dangerous herbicides,

such as 2,4-D and additives such as kerosene, shampoo, salt

and fertilizers.

The use of paraquat dichloride is causing immense harm to

farmers and agriculture workers, which are not documented

as we do not have systems in place to do so. The data

collected shows that farmers and farm workers are suffering

adverse health impacts due to exposure to paraquat.

In addition, secondary literature shows that paraquat has

been used for suicides in various parts of the country and has

a high mortality rate.

The conditions of use of paraquat in India violate the Interna

tional Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management. Also, other

conventions are violated, such as the Chemicals Convention,

1990 and the Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention, 2001.

A farmworker on a tea garden prepares pesticide

knapsack sprayers. The study found workers are

usually not trained to handle pesticides nor are they

provided with proper personal protective clothing.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 8

1. INTRODUCTION

Paraquat dichloride (CAS No. 1910-42-5) is a widely used

and highly toxic herbicide. It is a broad-spectrum (non-selective) contact herbicide and a powerful desiccant. Paraquat is

the third most widely used herbicide in the world. It is used

to control broad-leaved weeds and grasses, in a wide range of

agricultural applications and for general weed control; it is

less effective on deep rooted plants. Paraquat is increasingly

used to destroy weeds in preparing land for planting in com

bination with no-till agricultural practices that minimize

ploughing, thus the herbicide is widely promoted for no-till

and minimum-till agriculture use. Paraquat is commercially

produced and sold as dichloride salt and available as di

methyl sulphate as well. (FAO 2003; Watts M, 2011).

Chemically, it belongs to the group of bipyridilium her

bicides. This chemical group is called quaternary ammoni

um salts and generally known as quats. It destroys plant

tissue by disrupting photosynthesis and rupturing cell

membranes, which allows water to escape leading to rapid

desiccation of foliage. It is a fast-acting herbicide and gener

ally affects all exposed green parts of plants and kills them

in one to three days time (Neumeister L. Isenring R 2011).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) categorizes para

quat as a Class Il-moderately hazardous pesticide. Although

the WHO has listed it as moderately hazardous, it has been

listed among most hazardous pesticides in wide use in the

world today. Pesticide Action Network (PAN) International

has categorized it as a highly hazardous pesticide and it

shows high acute toxicity. Besides, paraquat has qualified as

a PAN bad actor as well as a PAN dirty dozen pesticide. The

Toxicological Data Network (ToxNet) and the Integrated

Risk Information System (IRIS) of the Unites States Environ

mental Protection Agency (US EPA) have classified it as a

probable human carcinogenic chemical (Class C). Paraquat

is also reported to have links to reproductive problems and

Parkinson’s disease (FAO 2003; WHO 2009; Watts M. 2011;

PAN Pesticide Database)

Paraquat is known to injure farmers, agricultural work

ers and community members as a result of occupational and

accidental exposure. The skin can absorb it. especially if

the skin has been damaged through exposure to the chemi

cal. Acute poisoning may occur (through skin, eyes or when

inhaled), but symptoms are often delayed. The outcome can

be fatal and in these cases, death results from respiratory

failure. Localized skin damage or dermatitis, eye injury and

nosebleed occur frequently among paraquat users. Long

term exposure to low doses of paraquat is linked to changes

in the lung and appears to be connected with chronic bron

chitis and shortness of breath. Recent studies also link oc

cupational and community exposure to paraquat to in

creased incidence of Parkinson’s disease (Weinberg J, 2009).

Paraquat is used in more than 130 countries. However,

paraquat is banned or its use is disallowed in at least 32

countries including members of the European Union due

to its adverse health effects. In Switzerland, the home

country of Syngenta, the main producer of paraquat, it is

banned since 1989 due to its high acute toxicity for hu

mans. In addition, many labelling organisations such as

the Fair Trade International (FTI). the Forest Stewardship

Council (FSC), the Rainforest Alliance, and food corpora

tions like Dole. Chiquita and retailers like Marks & Spen

cer have voluntarily banned paraquat (Watts M. 2011; Neu

meister L, Isenring R 2011).

Paraquat dichloride (24% SL) is registered in India with

the Central Insecticide Board and Registration Committee

(CIBRC). This is the only formulation registered in India.

CIBRC has categorised paraquat dichloride as highly toxic.

Although CIBRC has not provided any recommendations, it

has approved the use of this herbicide in nine crops. An

other formulation, paraquat dimethyl sulfate was banned

in India in 1993 (CIBRC 2014). Paraquat dichloride is one

among the twenty most commonly used and recommended

pesticides in the country (Chandra Bhushan et al., 2013),

although it is not the most used herbicide.

Paraquat is one of the pesticides most frequently used to

commit suicide. There is no antidote for paraquat. The

mortality rate for paraquat suicide attempts is comparative

ly high, at 42 to 80%. The number of suicides using para

quat throughout the world is estimated to be several tens of

thousands per year (Berne Declaration). Paraquat poisoning

has been reported from various parts of India ranging from

the northern Slates to the southern Stales and northeast

States (Khosya S and Gothwal S V. 2012; Pavan M, 2013;

Narendra S et al.. 2013; Raina S, 2008; Saravu K et al., 2013;

Sandhu JS et al., 2003; Raghu K et al., 2013; Banday T II et

al., 2014; Khan S U. 1975;Tayade S, 2013; Sarojini T, 2007).

Paraquat distribution, sale and use was stoped in Kerala

(a southern State in India) since 2011 along with 16 other

pesticides including endosulfan, due to their being highly

hazardous and having the potential to cause severe health

implications (Kerala Government order, 2011); and current

ly, paraquat is not being used in Kerala as per the data ob

tained through the Right To information Act.

Although paraquat is known to cause severe health

hazards and deaths among farmers, workers and communi

ty around the globe, only meagre data is available from In

dia. Besides, there is no ground level data available on the

application of paraquat in the fields, poisoning, etc. There

fore. the aim of this study was to document the actual prac

tices of paraquat use and associated health and environ

mental impacts from India.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 9

2. OBJECTIVES

The principal objective of the study was to document the

use of paraquat dichloride in India and associated health

and environmental impacts caused by its use. Thus the

study was to learn and document the actual practices of use

of paraquat in agricultural fields, the level of information

and awareness among users, and the extent of use of protec

tive measures among farmers and farm workers while han

dling or applying paraquat. The study was also intended to

show the conditions that could lead to exposure to para

quat and consequent poisoning, and to highlight the health

effects and symptoms manifested as a result of exposure. In

addition, the study was also meant to record any environ

mental impacts that farmers themselves had identified as a

result of the use of paraquat. An attempt was also made to

collect information on the recommendations, safety in

structions provided, training given on the use of personal

protective measures and application of paraquat from agri

culture extension officers and pesticide retailers. There

were some unofficial reports stating that the use of paraquat

has been slopped by farmers in some places in India. There

fore. as part of the study an attempt was also made to docu

ment information related to this. The recommended use of

paraquat in India and national level consumption data

were also collected as part of the study.

Workers in a tea garden spay pesticides without proper personal protective clothing.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 10

3. METHODOLOGY

A preliminary exploration was done to identify the areas

where paraquat is being widely used. Ten States were

identified (Andhra Pradesh. Arunachal Pradesh. Assam.

Chhattisgarh. Gujarat. Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh.

Telangana. Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal) based on the crops

for which paraquat is approved for use in the country. The

Stales were selected considering the area under cultivation

for the crops for which paraquat use is approved. Within

these States 20 districts were identified for the study'. In

these districts, interactions were carried out with pesticide

distributors, retailers and farmers to find out whether they

use paraquat in the area. This preliminary exploration re

vealed that paraquat was in use in eight districts across six

States. From the 12 districts across the remaining four

States it was reported that farmers had not been using

paraquat recently. Then it was decided to go with purpo

sive sampling and the data was collected from the eight

study sites (districts) across six Slates. The data was anal

ysed both through quantitative and qualitative methods.

SAMPLING

Purposive sampling was done to identify the respondents.

The data collection was especially focussed on farmers us

ing paraquat in their farms. The farm workers were identi

fied from the same areas. For the study, data was collected

from 82 respondents comprising of 50 farmers, 23 workers

(including eight paraquat/pesticide applicators), five pesti

cide retailers and four agriculture extension officers.

COLLECTION OF FIELD DATA

The field data for the study was collected from farmers,

farm/plantation workers including paraquat applicators,

pesticide retailers and agriculture extension officers with

the help of survey questionnaires filled up through person

al interviews. Separate questionnaires were developed for

each category of respondents with an emphasis on para

quat use, safetv measures used and recommendations, in

structions provided, information and awareness on safety

measures and trainings.

SECONDARY DATA

Secondary data on consumption of paraquat in India, poi

soning cases reported and other relevant data was also

collected as part of the study. The consumption data was

collected from the office of the Directorate of Plant Protec

tion, Quarantine and Storage under the Ministry of Agri

culture, Government of India, and the web sites of the

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation, Government of

India, and the Central Insecticides Board and Registration

Committee (C1BRC). Attempts were also made to collect

data through the provisions of the Right to Information

(RTI) Act and from various government (both Central and

State government) agriculture departments and institu

tions. For this, RTI applications were filed addressed to

agriculture departments in all the Stales in India as well

as to the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation.

Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage.

CIBRC, and the Department of Chemicals & Petrochemi

cals. However, only limited data from a couple of States

was received by the time the report was prepared.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

> Period of study: Data collection and field observations

were carried out for only four months-December 2014 to

March 2015. The period was not enough to cover a siz

able number of plantation workers/farm workers/farmers

due to the seasonal nature of their jobs.

> Due to the limited number of respondents, the study has

not drawn generalizations about the pattern of use of

paraquat all over India. Nevertheless, it does provide a

realistic picture of how paraquat is used today in India

as the interviews were done at various sites in differ

ent States, and a number of practices and problems ob

served were common in all the sites.

> Size of data: Availability of secondary data on paraquat

use and poisoning in India is limited. State wise data

on consumption of paraquat dichloride could not be

obtained except for some States of India. Therefore, it

was difficult to do a deeper analysis of the usage, health

impacts and other problems.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

Aocil 2015 // 11

4. STUDY AREA-STATE PROFILES

For the study, field data was collected from the eight iden

tified districts in six States. The areas were selected based

on selected crops such as tea, rice, potato, cotton, maize,

wheat and vegetables (in which paraquat is reportedly be

ing used). A short agricultural profile of the States from

which the data was collected is given below.

The Slate of Arunachal Pradesh is located in the north-eastein region of India. The major crops grown in Arunachal

Pradesh include rice, wheat, pulses, tea, cereals, maize,

gram, oilseeds, sugarcane, vegetables, potatoes, apples, or

anges pineapples, etc. More than half of the population in

Arunachal Pradesh depends on agriculture and allied sec

tors for its livelihood.

Assam, located in north-eastern India, is predominantly

rural and the economy is primarily agrarian in nature. Al

most 70% of the population is directly dependent on agri

culture and another 15% on allied activities for its living.

The major crops cultivated in Assam include rice, tea, jute,

sugarcane, fruits, pulses, coconut, cotton, areca nut, pota

toes and other vegetables.

Andhra Pradesh is situated in the south eastern coast of

India. The State's economy is mainly based on agriculture

and livestock rearing. Farming is the main occupation of

the people in the State and 60% of the population is en

gaged in agriculture and related activities. The major crops

are rice, cotton, wheat, sorghum, pearl millet, maize, many

varieties of pulses, oil seeds, sugarcane, vegetables and oil

crops such as peanuts and sunflower. (Telangana is a new

ly formed State, which was part of the Andhra Pradesh,

therefore the profile for Andhra Pradesh is also applicable

to Telangana.)

• Indicate Study area-States

Source: http://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=24868&lang=en

Madhya Pradesh is the second largest State in India, locat

ed in central India, and known as the heart of the nation.

The economy of the State mainly depends on agriculture

with more than 70% of the population involved in agricul

tural activities. The major crops grown in Madhya Pradesh

include cereals such as paddy, wheat, maize and sorghum.

pulses such as green gram, black gram, horse gram, oil

seeds such as soybean, groundnut and mustard. Cash crops

like cotton and sugarcane are also grown in few districts of

the State.

West Bengal is located in the eastern part of India and is

the nation’s fourth-most populous State. Agriculture is the

leading occupation of the people in West Bengal. Rice is

the principal food crop in the State and other major crops

are potato, jute, sugarcane, wheat and oil seeds. Tea is also

produced commercially in the northern districts.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 201S // 12

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Various government agencies are involved in the regula

tion of pesticides in India. The Ministry of Agriculture reg

ulates the manufacture, sale, transport and distribution.

export, import and use of pesticides through the Insecti

cides Act. 1968 and the rules framed there under. The reg

ulation of pesticides is governed by two different bodies:

the Central Insecticides Board and Registration Committee

(CIBRC) and the Food Safely and Standards Authority of

India (FSSAI). CIBRC was established, in 1968. under the

Department of Agriculture and Co-operation of the Minis

try of Agriculture.

The CIBRC is responsible for advising the central and

State governments on technical issues related to manufac

ture. use and safety of pesticides. Its responsibilities also

include recommending uses of various types of pesticides

depending on their toxicity and suitability, determining

the shelf life of pesticides and recommending a minimum

gap between the pesticide application and harvest of crops

(waiting period).

The other part of the CIBRC. the Registration Commit

tee (RC), is responsible for registering pesticides after veri

fying the claims of the manufacturers or importers related

to the efficacy and safety of the pesticides concerned. The

approval of the use of pesticides and new formulations to

tackle pest problems in various crops is also given by the

Registration Committee. 11 is the Food Safety and Stan

dards Authority of India that is responsible for recom

mending tolerance limits of various pesticides in food

commodities (Bhushan C et al., 2013).

The State Agriculture Departments (SADs), State Agri

culture Universities (SAUs) and other institutions such as

the National Horticultural Board (NHB) and various com

modity boards make recommendations for agricultural

practices including use of pesticides. The SAUs, SADs,

NHB and commodity boards have their own extension de

partments to reach out to farmers. The farmers of India

have a conventional understanding of agriculture; they

lack the technical understanding of pesticides, their uses

and safety aspects. This makes them vulnerable to mis

guidance and increases the chances of unnecessary and

inappropriate use of pesticides (Bhushan C et al.. 2013).

Approved use of paraquat as per CIBRC

The Central Insecticide Board and Registration Committee

(CIBRC) has approved the use of paraquat dichloride to

control weeds in nine crops-apple, cotton, grapes, maize.

potato, tea, rice, rubber and wheat. The dosage approved

for different crops varies widely from 800ml —2000 ml to

4250 ml. with an average 2072 ml per hectare (around

830 ml per acre). Along with the approved uses the waiting

period between the last application and harvest are also

given. Surprisingly, for food crops such as grapes, maize,

potato and wheat, the waiting period is 90 days, 90-120

days. 100 days and 120-150 days respectively. But it can

be observed that the waiting period has not been given for

apple, tea and rice. The waiting period for cotton is given

as 150-180 days.

Recommendation of paraquat dichloride by State

Agriculture Departments or Agriculture Universities as

well as commodity boards in India

The recommendation data for paraquat dichloride has

been collected from the package of practices recommended

by various State agriculture departments or agriculture

universities (SAD/AU) as well as commodity boards like

the coffee board, rubber board, tea board, etc. These have

been collected from the websites of the respective depart

ments or institutions. Through this method, data for only

12 States could be obtained. In addition, attempts were

also made to collect the same data through the Right to

Information (RTI) Act from all the 28 States in India, but

again responses have been received only from a few States.

From the compilation of the above said data it has

been observed that paraquat dichloride has been recom

mended for weed control in 17 crops. This is based on

incomplete data as confirmation about the recommenda

tion for use of paraquat is awaited from more States. The

table below provides the details of the recommendations

and the source. Again, this has to be compared against the

CIBRC approval for use of paraquat in only nine crops.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 201S // 13

TABLE 1

SL

NO

DETAILS ON THE APPROVED USE OF PARAQUAT DICHLORIDE 24% SL IN INDIA las ot October 2014)

DOSAGE/HA

FORMULATION IN

(ML/LITRE)

DILUTION

IN WATER

(LITREl/HA

POST-HARVEST

INTERVAL BETWEEN

LAST APPLICATION

& HARVEST (DAYS)

APPROVED CROPS

WEED SPECIES

1

Apple

(Post-emergence directed

inter row application at

2-3 leaf stage of weeds)

Rosa moschata,

Rosa eglantaria,

Rubus ellipticus

3.25 L

700-1000

N.A.

2

Cotton

(Post-emergence directed

inter row application at

2-3 leaf stage of weeds)

Digera arvensis,

Cyperus iria, Trianthema

monogyna, Corchorus

spp., Leucas aspera.

Euphorbia spp.

1.25-2.0 L

500

150-180

3

Grapes

(Post-emergence directed

inter row application at

2-3 leaf stage of weeds)

Cyperus rotundas,

Cynodon dactylon,

Convolvulus sp.,

Portulaca sp., Tridax sp.

2.0 L

500

90

4

Maize

(pre-plant (minimum

tillage] before sowing)

Cyperus rotundus,

Commelina benghalensis,

Trianthema monogyna,

Amaranthus sp.,

Echinochloa sp

0.8-2.0 L

500

90-120

Maize

(Post-emergence directed

inter row application

at 2-3 leaf stage of

weeds)

Cyperus iria,

Cyperus rotundus,

Commelina benghalensis,

Amaranthus sp.,

Echinochloa sp,

Trianthema monogyna

0.8-2.0 L

500

90-120

5

Potato

(Post-emergence overall/

inter-row application

at 5-10% emergence)

Chenopodium sp.,

Angallis arvensis,

Trianthema monogyna,

Cyperus rotundus,

Fumeria parviflora

2.0 L

500

100

6

Tea

(Post-emergence directed

inter row application at

2-3 leaf stage of weeds)

Imperata

setaria sp.,

Commelina benghalensis,

Boerraria hispida,

Paspalum conjugatum

0.8-4.25 L

(For season long weed

control, use 2.5-5.0

litres for initial applica

tion. For subsequent

repeat spot application

use 1 litre)

200-400

Not Necessary

(For season-long

weed control, use 2.5

to 5 litres for initial

application. For

subsequent repeat spot

application use 1 litre)

7

Rice

(pre-plant [minimum

tillage] before sowing/

transplanting for

controlling standing

weeds)

Echinochloa crusgalli,

Cyperus iria,

Ageratum conyzides,

Commelina benghalensis,

Marsilea quadriofoliata.

Brachia ria m utica

1.25-3.5 L

500

N.A.

8

Rubber

(Post-emergence directed

inter row application at

2-3 leaf stage of weeds)

Digitaria sp.,

Eragrostis sp.,

Fimbristylis sp.

1.5-2.5 L

600

N.A.

9

Wheat

(pre-plant (minimum

tillage] before sowing)

Grassy & Broad leaf weeds

4.25 L

500

120-150

Source: CIBRC http://cibrc.nic.in/muph2012.doc

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 14

TABLE 2 RECOMMENDATION OF PARAQUAT DICHLORIDE BY STATE AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENTS

AND OTHER INSTITUTIONS

SL

NO

CROPS

_________________

DOSAGE PER HA

SAD/AU OR BOARDS,STATE

Gramoxone 1000ml

in 2000 L water

www.yspuniversity.ac.in,

Himachal Pradesh State

1

Apple

2

Areca nut

Department of Agriculture,

Goa State

3

Banana

Tamil Nadu Agriculture University,

Kerala Agriculture University

4

Cane sugar

Indian Council of Agriculture Research

(ICAR)-Karnol,

Agriculture Department of Assam,

Uttarakhand and Goa States

5

Cashew

Department of Agriculture,

Goa State

6

Cherry

Gramoxone 2000 ml/h

www.yspuniversity.ac.in,

Himachal Pradesh State

7

Coffee

-

Coffee board, Tamil Nadu Agriculture

University (TNAU), Tamil Nadu

8

Cotton

9

Jasmine

-

ICAR-Goa

10

Jowar

Paraquat 1500ml/ha

Madhya Pradesh Agriculture Department

11

Maize

Paraquat 0.5kg with

Atrazine 1.0kg/ha

Agriculture Departments of Madhya Pradesh

and Andhra Pradesh States

12

Oil Palm

13

Pineapple

14

Potato

15

Rice

-

Agriculture Departments of Kerala

and Assam States

16

Rubber

Paraquat 0.5kg +

2,4-D 1.25 kg

Rubber board and Department of Agriculture,

Kerala State

17

Tea

REMARKS

Assam Agriculture Depart

ment recommended

2,4-D (amine-salt)

1.0 kg a.i/ha+ paraquat

0.5 kg a.i/ha in mixture

Agriculture Departments of Odisha,

Punjab, Andhra Pradesh States

Tamil Nadu Agriculture University,

Tamil Nadu

-

Kerala Agriculture University

*,

Kerala

Agriculture Departments of Uttarakhand

and Punjab States

Assam: Pre-harvest

treatment on standing crop

for better grainquality.

TNAU, Tea Research Association

and Tea Research Foundation

Source: Compiled from package of practices published by agriculture departments, agriculture universities, commodity boards and their respective web

sites as well as through the Right to Information Act.

* Paraquat dichloride is stopped in Kerala since 2011

Recommendation for use-manufacturer advice

In order to get a picture about the industry practice on the

recommendation for use of paraquat, the instruction leaflet

provided along with Gramoxone, a product of Syngenta

and Kataar, a product of Canary Agrochemicals were ana

lyzed. As per the leaflet provided with Gramoxone, Syn

genta has recommended the product for weed control in 12

crops and for aquatic weed control as well. Canary Agro

chemicals has recommended their product Kataar for 11

crops and aquatic weeds.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

Variations in approved use and recommended use

of paraquat dichloride in India

The data from CIBRC, State agriculture departments or agri

culture universities (SAD/AU) and commodity boards, in

dustry recommendation as well as use reported from the

field shows plenty of variations and violations. The CIBRC

has approved paraquat for use in nine crops, while the avail

able data shows that the SADs/AUs and commodity boards

have recommended paraquat for use in 17 crops. Over and

above this, data from the six States covered in the study in

dicates that paraquat is being used in a total of 25 crops.

In the list of 17 crops proposed by the SAD/AU, paraquat

is recommended for use by the CIBRC only in seven

crops-apple, cotton, maize, potato, rice, rubber and lea.

The CIBRC has not approved the use of paraquat for the

remaining 10 crops. This shows that these bodies have rec

ommended paraquat in violation of the directive by the

CIBRC, demonstrating the lax approach towards national

regulation. This is a problem which is also found with oth

er pesticides as shown by Bhushan C el al., 2013.

April 2015 // IS

A wide range of variation has been observed in the field

data. As evident from the study, paraquat is being used for

weed control in about 25 crops across six States. Among

this 25. usage on only six crops (cotton, maize, potato, rice,

tea and wheat) has been approved by the CIBRC. Thus, the

use of paraquat for the remaining 19 crops is in violation of

the directive of the CIBRC. Among these 19 crops that vio

late the CIBRC directive, one crop-banana-has been rec

ommended by an agriculture university (again in violation

of CIBRC directive).

The manufacturers have also violated the directive for

approved use by the CIBRC. as evident from the Table 3.

The recommendation by Syngenta includes all the nine

crops approved by the CIBRC. three other crops (coffee,

sugarcane, and sunflower) and for aquatic weed control.

which are not approved by the CIBRC. In the same way, of

the 11 crops recommended by Canary Agrochemicals,

only seven were approved by CIBRC for paraquat use. The

use of paraquat on the remaining four crops (coffee, sugar

cane. tapioca, sunflower and for aquatic weeds) is not ap

proved.

TABLE 3: VARIATIONS IN APPROVED USE AND RECOMMENDED USE OFPARAQUAT DICHLORIDE IN INDIA

1.

CIBRC APPROVED

USAGE

1. Apple

2. Cotton

3. Grape

4. Maize

5. Potato

6. Rice

7. Rubber

8. Tea

9. Wheat

2.

RECOMMENDATIONS BY

SAD/AU/COMMODITY

BOARDS

1. Apple

*

2. Areca nut

3. Banana

4. Cane sugar

5. Cashew

6. Cherry

7. Coffee

8. Cotton

*

9. Jasmine

10. Jower

11. Maize

*

12. Oil palm

13. Pineapple

14. Potato

*

15. Rice

*

16. Rubber

*

17. Tea

*

3.

RECOMMENDATION BY

MANUFACTURERS

4.

DATA FROM THE FIELD

ON CROPS FOR WHICH

PARAQUAT IS USED

1. Apple’

2. Coffee

3. Cotton

*

4. Grapes

*

5. Maize

*

6. Potato

*

7. Rice

*

8. Rubber

*

9. Sugarcane

10. Sunflower

11. Tea

*

12. Wheat

*

13. Aquatic weed control

1. Banana

2. Bottle gourd

3. Brinjal

4. Carrot

5. Chilly

6. Cotton

*

7. Ground nut

8. Jute

9. Kakrol

10. Maize

*

11. Marigold

12. Mustard

13. Okra

14. Onion

15. Orange

16. Parble

17. Potato

*

18. Pumpkin

19. Rice

*

20. Sesame

21. Soybean

22. Sunflower

23. Tea

*

24. Tomato

25. Wheat

*

Source: Compiled from Tables 1 and 2, and recommendation given in the leaflet/label of commercial products of paraquat and field data.

* Crops approved by the CIBRC

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 201S II 16

5.2. CONSUMPTION OF PARAQUAT DICHLORIDE

IN INDIA

The chart given below shows the consumption data of

paraquat dichloride and total herbicide consumption in

India for the period between 2007-08 and 2013-14 (as on

December 18, 2014). The data reveals that the volume of

paraquat consumed is much less when compared to the

total herbicide consumption in the country. However, in

spite of paraquat not being the herbicide used in the largest

quantities in comparison with other herbicides in India, its

conditions of use are dangerous with many opportunities

for serious exposure and risks to human health to farmers.

agricultural workers, and others who handle paraquat,

such as applicators and retailers.

CHART 1 CONSUMPTION OF PARAQUAT

DICHLORIDE AND TOTAL HERBICIDE

CONSUMPTION IN INDIA

in metric tonne (MT) technical grade

Commercial names of paraquat dichloride

reported from the study sites

From the study sites across six States 14 commercial prod

ucts. manufactured by different firms, of paraquat dichlo

ride were used for weed control.

TABLE 5 COMMERCIAL NAMES OF PARAQUAT

DICHLORIDE REPORTED FROM FIELD

SL

NO.

COMMERCIAL

PRODUCTS

MANUFACTURER

1

All quit

Crystal

2

Finish

Total Agricare

3

Gramex

Crop Chemicals India

4

Gramo

Canary

5

Gramoxone

Syngenta

6

Herbucsone

Ankar Industries

7

Kapiq

Krishirasayan

8

Kataar

Canary

9

Milquat

Insecticides India

10

Paranex

Makhateshim-Agan India

11

Paraxzone

National Pesticides and

chemicals

12

Uniquat

United Phosphorous

13

Parachlor 24

-

14

Ozone

Dhanuka Agritech limited

Source: Compiled from field data obtained through the study

Year

Source: Compiled using the data obtained from the Directorate of Plant

Protection, Quarantine and Storage and CIBRC

I TABLE 4 PERCENTAGE OF PARAQUAT DICHLORIDE TO THE TOTAL HERBICIDE CONSUMPTION

YEAR

2007-08

2008-09

2009-10

2010-11

2011-12

2012-13

2013-14

Percent of

paraquat dichloride

consumed

3.63

3.48

5.36

2.52

2.58

4.01

4.98

Source: Compiled using the data obtained from Directorate of Plant Protection Quarantine and Storage and CIBRC

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 2015 // 17

Various Trademarks for paraquat sold in India: Gramo (manufacturer Canary), Gramoxone (Syngenta),

Kataar (Canary), Milquat (Insecticides India)

State wise consumption of paraquat dichloride

The consumption data for paraquat dichloride was collect

ed through the Right to Information (RTI) Act. Below are

the responses received from four States. State wise con

sumption dala of paraquat dichloride for the four States in

India-Punjab. Goa, Maharashtra and Kerala-reveals that

it continues to be used in fairly large volume in three of the

States except Kerala, where paraquat was stopped since

2011. mainly because of health concerns.

I TABLE 6 STATE WISE CONSUMPTION DATA FOR PARAQUAT DICHLORIDE OBTAINED THROUGH RTI ACT 1

Punjab

Goa

Maharashtra

Kerala *

PARAQUAT

DICHLORIDE 24 SL

IN LITRES

GRAMOXONE,

PARACHLORE AND

ALL QUIT; IN LITRES

PARAQUAT DICH

LORIDE TECHNICAL

GRADE IN MT

PARAQUAT DICH

LORIDE TECHNICAL

GRADE IN MT

2004-05

-

-

12

-

2005-06

275532

2500

12

12.415

2006-07

276715

2500

11

13.629

2007-08

296379

2500

09

48.336

2008-09

299550

3000

10

61.817

2009-10

286111

3000

47

33.017

2010-11

305214

3200

156

37.2

2011-12

311450

3000

120

-

2012-13

319237

3000

96

-

2013-14

323952

4200

92

-

2014-15

231448

4000 (up to Jan 2015)

-

-

Year

Source: Compiled using data obtained from the agriculture departments of respective States.

Note: State wise consumption data is incomplete as data from only four States was obtained.

Paraquat is stopped (distribution, sale and use) in the State of Kerala since 2011, as per the Kerala Government order dated 07.05 2011

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

5.3.

April 201S // 10

FINDINGS OF THE FIELD STUDY

Field data for the present study was collected from 82 re

spondents including farmers, farm and plantation workers

(including pesticide applicators), pesticide retailers and

agriculture extension officers from eight study sites in six

States in India. The data was analysed separately for farm

ers, farm workers as well as applicators, and the survey

results were compiled separately for agriculture extension

officers and pesticide retailers.

bitter gourd, etc. All the farmers use chemical fertilizers and

pesticides including herbicides. Some farmers also use farm

yard manure, oil cakes and green manure in their farm.

All the farmers employ weed management practices

such as manual hand weeding, mechanical weeding by

cattle plough as well as by tractors and chemical weed

control using herbicides. The herbicides commonly found

in use in the study area include glyphosate, paraquat, pretilachlor. quizalofop ethyl. 2,4-D and butachlor.

Demographic details of workers

Classification of respondents

The respondents included 59 men and 14 women, excluding

retailers and agriculture extension officers. Their education

al qualification ranges from secondary school to post gradu

ation. except for a few who arc illiterate. For most of these

respondents, agriculture is the major source of livelihood.

TABLE 7: CLASSIFICATION OF RESPONDENTS

FARM WORKER

APPLICATORS2

FARM

WORKERS1

FARMERS

PLANTATION

AGRICULTURE

WORKEREXTENSION

PESTICIDE

APPLICATORS3 OFFICERS

RETAILERS

3

4

5

TOTAL

82

Demographic details of farmers

Sixty percent of the farmers included in the study have

been using paraquat for up to five years; 24 % have been

using paraquat between five and ten years and the remain

ing 8% have been using paraquat for more than ten years,

the remaining respondents have not furnished any details.

The respondents consist of marginal farmers, small-scale

farmers as well as large-scale farmers. The land holding of

the farmer respondents ranges from half an acre to a maxi

mum of 56 acres. A few farmers have taken land on lease for

cultivation in addition to farming on their own land. The

number of respondents holding land between half an acre

up to 15 acres is 40 (80%). The remaining 20% of the re

spondents hold land ranging from 15 acres to 56 acres.

The major crops grown by the respondents include pad

dy, wheat, mustard, jute, ground nut. sunflower, maize, cot

ton, tea, sesame, banana, sugarcane and vegetables such as

chilly, onion, potato, tomato, okra, brinjal, pumpkin, kakrol

and parble (both are cucurbitaceous vegetables), bottle gourd.

z\s part of the study, data on the use of paraquat, informa

tion and awareness about safety measures and health ef

fects were collected from farm workers in addition to farm

ers. A total of 23 respondents were interviewed and

included 15 workers from the States of Arunachal Pradesh

and Andhra Pradesh. The respondents from Arunachal

Pradesh are daily labourers working in small scale tea gar

dens in Namsai district. Most of the respondents from

Andhra Pradesh are also daily labourers working in cotton.

paddy, and vegetable farms. Ten of them are women work

ers and five of them are male workers. All the respondents

are working in farms where paraquat is used. Almost all

the workers are involved in all the activities in a farm, in

cluding fertilizer application, watering plants, weeding,

harvesting, processing and also washing equipment used

for application of paraquat and pesticides (40% of them

claimed that they have occasionally been involved in ei

ther mixing or applying paraquat).

The remaining eight respondents are farm workers (re

ferred to as applicators) mainly involved in applying pesti

cides including paraquat. Among them, five are farm work

er-applicators from the study area in four States- Andhra

Pradesh. Madhya Pradesh. Telangana. West Bengal and

three arc plantation worker-applicators from a commercial

tea plantation in z\ssam. All of them are males and they

have been involved in spraying paraquat and other herbi

cides. insecticides and fungicides. They also do other work

in the farm apart from spraying. On an average they spend

about 2-3 hours for one spraying and reported that in a

year they spray paraquat 10-15 times. Two applicators

said they have been spraying paraquat since two to four

years, five applicators slated they have been applying para

quat for about six to eight years and one applicator said that

he has been applying paraquat since 12 years.

Reasons for using paraquat

Respondents reported that paraquat helps to kill weeds ef

fectively within a short time period, therefore, they feel

that using paraquat is an easy method to control weeds. In

addition, weed control with paraquat and with other herbi

cides is less expensive compared to the cost incurred for

1 Farm worker: hired workers working in agricultural fields, they normally do not spray pesticides but are exposed while working in fields where these

are used. They are sometimes involved in mixing these chemicals for spraying.

2 Farm worker-applicator: Workers hired by farmers specifically for application of pesticides and herbicides

3 Plantation worker-applicator: Daily wageworkers working in commercial tea plantations, who usually do the spraying of pesticides and herbicides in

the plantation.

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

manual weeding. In addition, the spraying is comparative

ly a less labour intensive operation which takes less time as

well. Sixty percenl of the respondents reported that labour

problem is the major reason for not doing manual weeding.

Twenty eight percent of the respondents reported that para

quat is cheaper than other herbicides and 44% of the re

spondents reported paraquat is effective and burns weeds

quickly. Lack of availability of skilled labourers, non avail

ability of labourers during critical periods, increased la

bour costs, are the major problems faced by farmers due to

which they have moved to using herbicides. Lack of skilled

workers to run and manage the cattle plough, lack of avail

ability of sufficient number of cattle ploughs and increased

cost of rental has reduced the use of cattle plough in weed

ing. Among all the respondents the chemical weed manage

ment method has become widely accepted.

«or*l 2015 // 19

pulses and vegetables. Paraquat is applied in the field

about 15-20 days before the planting date, followed by

field preparation once the weeds are burnt and then the

crop is sown or planted. Paraquat is applied for weed con

trol in standing crops as well. Fifty eight percent of the

respondents reported that they apply paraquat for con

trolling weeds in spaces between the rows, ridges and fur

rows, as well as field bunds and boundaries of crops such

as paddy, wheat and vegetables.

Paraquat is applied in two ways, one is by dispersion

and the other is through spraying. The CIBRC data shows

that paraquat is approved only for spraying. In addition,

information obtained from the leaflet of Gramoxone, the

manufacturer (Syngenta) only recommends use through

spraying. But field data shows that farmers are using it by

dispersion as well, ignoring the label, which is not recom

mended. Both the methods-dispersion and sprayingwere observed in the study area and are described below.

CHART 2 REASONS FOR USING PARAQUAT

Application of paraquat by dispersion

Source: Based on field data

A few respondents especially from zXndhra Pradesh and

Telengana reported this type of application. Here paraquat

is mixed with either sand, fertilisers or salt and the mix

ture is dispersed by hand. Twenty six percent of the farm

ers interviewed, reported this practice. Chilly, cotton.

maize and paddy are the crops for which farmers disperse

paraquat for weed control. Eighteen percent of the respon

dents (farmers) reported having applied paraquat in paddy.

6% in chilly as well as cotton, and 4% in maize. The arti

cles used as carrier substances were sand (18% respon

dents). fertilizer especially urea (16% respondents) and

salt (6% respondents). The average volume of paraquat

used per acre was about 1000 ml with a minimum of 100

ml to a maximum of 1500ml. The other materials added

ranged from five kilograms to 75 kilograms. None of them

reported the use of personal protective equipment while

mixing or dispersing paraquat.

Crops in which paraquat is used (Based an data collected from

the field during the survey)

TABLE 8: DISPERSAL OF PARAQUAT

As per the data collected during the survey the crops for

which paraquat is used includes cereals, pulses, oil seeds,

vegetables and in horticulture. Farmers use paraquat for

controlling weeds in 25 crops (the list is given in Table 3).

As of now. there is no mechanism in India to monitor and

ensure that paraquat (and other pesticides as well) is used

only on crops for which it is legally approved. There is also

no mechanism to prevent the illegal use (use in crops other

than approved) of paraquat and other such chemicals.

WITH OTHER MATERIALS

Paraquat application in the field

Source: Compiled from field data

Paraquat is applied in the field mainly during pre-plant

ing, pre-sowing, seedling or vegetative stage as a pre-emergence measure as well as applied for post-emergent weed

control. Pre-planting or pre-sowing application is reported

by 70% ol the respondents. This is a common practice ob

served in all the study areas. The pre-sowing or pre-plant

ing application was observed for crops such as cereals.

CROPS

Cotton

Maize

Rice

Chilly

PARAQUAT

DICHLORIDE

Average

about 1000ml

per acre

OTHER

MATERIALS

ADDED

Common salt

Sand

Fertilizers

(urea)

% OF RES

PONDENTS

26

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

April 201S // 20

ommended by the retailers or the agents of distributors.

The practice of adding such substances has not been rec

ommended by the C1BRC. agriculture departments, agri

culture officers or the manufacturers. But field data shows

that farmers are doing this under the advice from retailers

or agents of distributors. It was observed that the retailers

or the agents of distributors have more reach in the rural

community than agriculture officers and are able to influ

ence the practices. Also most of the farmers interviewed

were not using personal protective equipment (PPE) to

protect themselves.

Application of paraquat by spraying

Spraying is the more widely practiced method of using

paraquat observed in the study areas. All the respondents

reported that they apply paraquat by spraying. For cotton.

maize and potato, the dosage used was more than what is

recommended. Eighteen percent of the respondents report

ed that while mixing paraquat for spraying they add 2.4-D

(another herbicide) and other materials such as salt, kero

sene. shampoo and adhesives. Farmers said that these ma

terials are added to improve the effectiveness and to burn

the weeds quickly. They added that such practices are rec

1 TABLE 9 QUANTITY OF PARAQUAT USED AND THE ADDITION OF OTHER MATERIALS

CROPS

PARAQUAT

DICHLORIDE (ML)

USED PER ACRE

(AVERAGE)

Cotton *

CIBRC APPROVED

DOSE (ML/ACRE)

VOLUME WATER

(IN LITRES) USED

FOR DILUTION

(AVERAGE)

% OF

RESPONDENTS

887

500-800

203

2

Jute

1000

r

200

4

*

Maize

1175

320-800

183

8

Mustard

1100

-

160

2

*

Rice

905

500-1200

207

24

Soybean

600

-

125

4

*

Tea

812

320-1700

200

8

*

Wheat

914

1700

143

14

Vegetables

and others

964

800 ml

(only for potato

*)

197

38

Source’ Compiled from field data and Table 1

I

OTHER

MATERIALS

ADDED

18% respondents

■ reported that they

add other materials

such as common

■ salt, shampoo,

kerosene, 2,4-D as

well as some

- adhesive while

mixing

• Crops approved by CIBRC

Some respondents reported that they have had to increase

the volume;of paraquat used over the years. Fifty percent

of the respondents reported having increased the volume

of paraquat used, over what they used previously, to en

sure that weeds are burnt as quickly as possible. A couple

of farmers said that they mostly decide the volume of para

quat to be used without consulting any authority.

It was observed that paraquat application is mostly

done by farmers themselves in their fields. Seventy six per

cent of the farmers interviewed reported that they apply

paraquat in their fields and the remaining 24% said that

they hire workers to apply paraquat and other pesticides in

their fields.

Application of paraquat by farm workers

The farm worker-applicators reported that generally para

quat is spraved before sowing or planting as well as in the

inter row spaces and ridges or boundaries of standing crops.

The frequency of paraquat application varies among differ

ent crops depending on weed growth. In tea plantations

paraquat is sprayed four to eight times a season, for cotton

paraquat is applied three times, for vegetables one to two

limes and for paddy once in a season. Data obtained from

farm worker applicators shows that the average volume of

paraquat used is 955 ml per acre and is diluted on average

with 220 litres of water. Plantation worker applicators re

ported that 750-800 ml of paraquat is used per acre and the

volume of water used is 200 litres. In addition they also said

that if weed intensity was severe, sometimes they added 500

gm of 2,4-D as well. Two farm worker-applicators reported

that in the recent past they had been applying paraquat in

higher doses compared to what they used earlier.

Frequency of paraquat usage

The frequency of application ranged from once in two

weeks to once in a year. Those who apply paraquat once in

a year or once in a season usually do the application before

planting crops such as maize, cotton, paddy, wheat and

vegetables. Other responses included twice a season/year,

three to four times and five to eight times in a season/year.

and once or twice a month. Farmers said that there is no

spraying calendar, but whenever weed intensity is found

CONDITIONS OF PARAQUAT USE IN INDIA

Type of sprayers used and problems

The study revealed that farmers use different types of

sprayers for applying paraquat. The most popularly used

one is a backpack or knapsack sprayer, which is used by

60 % of the respondents. Another type of sprayer used by

24 percent of the farmers interviewed is a simple hand op

erated sprayer popular among farmers especially in West

Bengal. Most of the farmers in the region are marginal, and

this type of hand sprayer is the only one they can afford as

it costs around 250 rupees. These sprayers are not closed

systems and therefore the risk of spillage is higher. A few

respondents (12% of the farmers interviewed) reported the

use of power sprayers operated by diesel motors. Most re

spondents reported that they spray during the forenoon.

especially during the morning and a few reported that

spraying is done in the afternoon and evening.

All the applicators interviewed for the study were us

ing backpack sprayers except one farm worker applicator.

who was using a hand sprayer. All the applicators except

one stated that the spraying was generally done during the

forenoon. The remaining farm worker applicator said that

he did spraying in the evening. All the applicators report

ed that they considered the direction of wind and always

sprayed only along the direction of the wind.

56% of the farmers knew to repair a leaking or damaged

sprayer, and almost half of the respondents (44%) were

incapable of doing the repairs themselves.

The three plantation worker-applicators and three of the

five farm worker-applicators reported that the sprayer leaks

happened sometimes and the remaining one farm worker

applicator reported the sprayer had never leaked. Four ap

plicators (three plantation workers and one farm worker

applicator) reported that they could repair a leaking spraj'er

and they usually repair the sprayer immediately after noting

the leak or after the spray or before the next spray.

Working in sprayed fields- farmers

Most of the respondents reported that they continue to

work in the field (where paraquat is sprayed) immediately

after the spray. They said that they work on the same day if

some work is pending in the farm. Fifty four percent of the

respondents said that they re-enter the field immediately

after the spray. Two percent of the respondents said that

they enter the field the next day after the spray. Eighteen

percent of the respondents reported that they usually wait

for two days after the spray, and eight percent of the re

spondents reported that they enter the field after one week

of the spray. However, if there is some pending work or

urgent work like harvesting or fertilizer application or pes

ticide spray, farmers generally enter the field without wait

ing for a gap after spraying.

7U0J O'

to reach problematic levels paraquat is applied. They add

ed that during rainy season repeated applications are

required. Usually spraying of paraquat kills weeds imme

diately but weeds regenerate in 10-15 days; therefore re

peated application becomes essential especially for crops

that require continuous management in terms of irrigation.

fertilizer application, harvest, etc. Mostly such repeated

applications were noted in vegetables and tea.

«prll 201S // 21

CHART 3 TYPE OF SPRAYERS USED-FARMERS

70

Source: Based on field data

When asked about whether leaks occurred in the sprayer.

majority of the respondents (86%) reported that leaks had

happened, the rest reported no leaks. From the responses

provided it is evident that out of the total respondents only

The plantation worker-applicators reported that workers

were allowed to enter an area sprayed with paraquat only

after 24 hours after the spray. Three of the five farm worker

applicators and 10 out of the 15 agriculture workers report