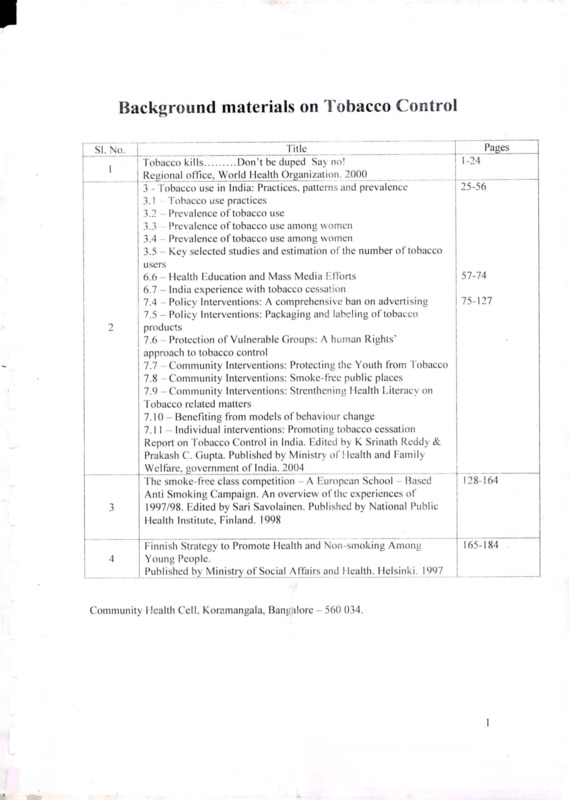

Background materials on Tobacco Control

Item

- Title

-

Background materials on Tobacco Control

- extracted text

-

Background materials on Tobacco Control

SI. No.

I

2

3

4

Title

____

' Tobacco kills

Don’t be duped Say no!

Regional office, World Health Organ[zation. 2000

3 - Tobacco use in India: Practices, patterns and prevalence

3.1 Tobacco use practices

3.2 - Prevalence of tobacco use

3.3 Prevalence of tobacco use among women

3.4 Prevalence of tobacco use among women

3.5 - Key selected studies and estimation of the number of tobacco

users

6.6 - Health Education and Mass Media Efforts

6.7 - India experience with tobacco cessation

7.4 Policy Interventions: A comprehensive ban on advertising

7.5 - Policy Interventions: Packaging and labeling of tobacco

products

7.6 Protection of Vulnerable Groups: A human Rights’

approach to tobacco control

7.7 - Community Interventions: Protecting the Youth from Tobacco

7.8 Community Interventions: Smoke-free public places

7.9 - Community Interventions: Strenthening Health Literacy on

tobacco related matters

7.10 - Benefiting from models of behaviour change

7.1 1 - Individual interventions: Promoting tobacco cessation

Report on Tobacco Control in India. Edited by K Srinath Reddy &

Prakash C. Gupta. Published by Ministry of Health and Family

W el fare, govern men t of India. 2004

The smoke-free class competition A European School Based

Anti Smoking Campaign. An overview of the experiences of

1997/98. Edited by Sari Savolainen. Published by National Public

Health Institute, Finland. 1998

Finnish Strategy to Promote Health and Non-smoking Among

Young People.

Published by Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Helsinki. 1997

Pages

1 -24

25-56

57-74

75-127

128-164

165-184 .

Community Health Cell, Koramangala, Bangalore - 560 034.

1

H

?

a,

5

6

f

\

7

Control of Tobacco Habits

Smoking habits

Tobacco control in India

Tobacco Research and Interventional Studies in India

Tobacco and ArecaNut by V M Sivaramakrishnan. Published by

Orient Longman, Bangalore. 2001____________ ________

Appendix 3 - Health effects associated with exposure to Second

hand Smoke

Appendix 4 - Countering the opposition

Protection from Exposure to Second-hand Tobacco Smoke - Policy

recommendations. WHO, Geneva. 2007

Crowding out effect of tobacco expenditure and its implications on

household resource allocation in India by Rijo M. John.

Social Science and Medicine, 66 (2008) 1356-1367

185-233

234-241

242-253

2

•y-v- 'S13S'??fSs’5?S!S§

SWMtW

^^aG^-lciliS

;c.7Si K-Tad

J J:

Ml

i■

WBs

twww

I?r

.^3'=

I

v

Q

L Zb/ Fi- (x

hM \ J f

h- • /-'. (

CW.

TWfe

^:^'-. /^7/

J .

£

KJ•*

v^®'"

;?u>;

^®gV1'

■J.

I^Jfc.

I

■PS^

-

VorjiS^Tobacco Day

’

2000

[

3

swg'SasSK;.

1

[ealth Organization

fc MediterraneanIHilfgional Office

Contents

Message from the Director General--------------------

3

Message from the Regional director------ -------------

5

The health dimension of the tobacco problem---------

8

The tobacco industry’s war on public health----------

12

From the horse’s mouth: the tobacco industry speaks

16

Reducing the glamourization of tobacco in movies,

I

on television and on music videos--------------------- -

20

A message to all youth from Duraid Lahham-------

28

Tobacco control legislation and its implementation

30

Islamic rulings on smoking----------------------------

37

The Christian view on smoking-----------------------

43

Celebrities killed by Tobacco

46

Message from

Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, Director-General

of the World Health Organization for

World No Tobacco Day 2000

Every day, 11000 people die due to a tobacco-related disease.

Tobacco is a communicated disease—communicated through

advertising and promotion for which the tobacco industry spends

billions of dollars. Tobacco advertisements talk to us from our streets,

films, radios, television sets and sports events. Everywhere our

children and we turn, there is something or someone telling you to

smoke.

What -makes all this unacceptable and treacherous is that this

dangerous and addictive product is sold to youth and adolescents as an

assertion of their freedom to choose. One of the primary objectives of

the tobacco industry is to frame tobacco use as an individual and

behavioural decision. The deception in this casting is that it leaves the

tobacco industry’s activities and practices completely out of the

equation. It assumes that people make their decisions in a state of

vacuum, completely uninfluenced by the environment of industry

advertising and marketing.

Research shows that people’s decision to smoke is influenced by

tobacco industry promotion. Tobacco advertising featuring prominent

sports and entertainment figures project and reinforce and image of

tobacco as glamorous, firn, healthy, sophisticated and wealthy. In

countries where advertising bans are beginning to emerge, subtle

product placement in films and film videos continue to send these

messages to young people. By the time people find out, it is often too

late.

So what is it that the tobacco industry spends billions of dollars to

conceal? They want to suppress truth that documents their

manipulation of nicotine to levels that ensure that addiction occurs and

is sustained. Truth that shows us that the tobacco industry privately

3

develops strategies to market to children while publicly claiming the

contrary. Truth, that instructs us that it is hard, if not impossible to

find any parallel in history where people who have gone about in such

a systematic way perpetuating death and destruction have gone

unpunished and unquestioned.

Our decision to focus on the entertainment, films and sports

industry for World No Tobacco Day this year is a carefully thought

one. It is unconventional and unorthodox, but that is precisely why we

have chosen it—the tobacco industry strikes where people least

suspect it to be. Global advertising bans is also one of the early

protocols that will be negotiated by WHO’s 191 Member States

working on the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. The

decision to highlight that early in the treaty-making process is no

accident—it is our answer to calls from our Member States seeking an

urgent global response to a global menace.

Together, we can hold up mirrors to their practices. Together, we

can buck the tobacco tide that is set to claim 10 million people by

2030, over 70% of them in the developing world. To those young and

not so young who might be debating whether or not to start smoking,

1 would like to say, “tobacco kills—don’t be duped.”

Message by

Dr Hussein A. Gezairy

Regional Director

WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region

on the Occasion of World No Tobacco Day

31 May 2000

As I was completing this message on the occasion of World No

Tobacco Day, a friend of mine asked me the following question: why

does the World Health Organization put such a strong emphasis on

tobacco smoking when everyone is fully aware that smoking is

extremely harmful to health? He added: every smoker knows this fact

and feels it in his poor health and his vulnerability to many diseases

and the rapid deterioration of his health.

That many people are generally aware of the harmful effects of

smoking is one thing, but knowing the full extent of such effects and

the health, social and economic consequences of smoking is

something else. Who, among the vast majority of people, realizes that

in the few minutes a person needs to read this message, smoking will

have killed 60 more people? How many of us realize that tobacco

smoking kills more than 10 000 people every day? As for the diseases

directly related to smoking, these are countless. It is sufficient to state

that if everyone were to stop smoking completely, and if no one were

to light up a cigarette or puff out tobacco smoke, the world would be

spared one-third of all cancer cases, a substantial proportion of

cardiovascular diseases would be prevented, and a further substantial

reduction would be achieved in the number of cases of many serious

and killer diseases. The fact is that smoking is a more fatal killer than

wars, natural disasters and epidemics.

Nevertheless, smoking remains acceptable in many social

environments. Smokers continue to puff away at home and at work,

paying no heed to the extensive and serious harm to which they

4

5

expose their families and colleagues. The tragedy is that the number

of smokers is increasing, and its tragic consequences are rapidly

mounting. According to WHO’s estimates, the number of smokers in

the world today is in excess of 1.25 billion, which is more than

one-third of all people above 15 years of age. If the present trends

continue, this number will continue to rise. By the year 2020, the

number of victims which tobacco kills all over the world will reach 10

million every year, or more than 10 000 every hour of the day and

night.

Despite all the health problems tobacco smoking causes, powerful

interests including multinational companies and prosperous national

industries continue to promote tobacco, targeting adolescents and

women in particular. The tobacco industry is always trying to

compensate for the loss of those of its customers killed by its evil

product. It tries to give smoking a false glamour and an adventurous

aura that it does not have. By so doing, it seeks to attract teenagers

before they gain a full picture of the harmful effects of tobacco and

the hard addiction it causes.

At the same time, officials in certain sectors, such as agriculture,

industry and taxation, imagine that they make large financial and

economic profits from tobacco growing, sale and consumption. But a

proper balance sheet of profits and losses attributed to tobacco will

immediately reveal that the losses incurred by every country of the

world in consequence of smoking far outweigh the profits it makes.

This is true when we include just the hard figures of material gain and

loss. The human loss, in terms of morbidity and mortality, however, is

too great to be balanced against any financial revenue that by contrast

will remain paltry, no matter how high its figures are.

also helps smokers to quit their harmful habit. Such an effort should

also contribute to rescuing the world from the scourge of smoking and

to achieving a tobacco-free world.

But these goals cannot be achieved except through a common

effort in which all take part. Every year the World Health

Organization seeks to enlist the support of one sector of society in the

fight against tobacco with an aim of preventing its promotion. This

year we are trying to enlist the support of all who work in the

entertainment sector, including the media. When we look around, we

find that tobacco promotion seeks to portray smoking as glamorous

and fun. We also see places of entertainment, such as cafes and places

of recreation, providing facilities that encourage people to smoke.

Many hotels and clubs have introduced what they describe as a

Ramadan tent in which the sinful practice of smoking, particularly

waterpipe, is encouraged, and thereby they defile the month of

worship. Women’s smoking of the waterpipe has recently become

very common in these places, while it used to be totally unknown.

The fact is that all this promotion relies on absolute falsehood.

There is in fact no pleasure to be derived from smoking. Pleasure is to

be sought in practices that promote health and prevent disease. Thus

the World Health Organization appeals to all men and women who

work in the entertainment, sector to join it in its strong stand against

tobacco and to contribute to the worldwide effort to protect our young

against the temptation to smoke and to free our world of tobacco. This

is highlighted in the slogan we raise this World No Tobacco Day:

Don’t be duped... tobacco kills.

May God bless you all.

f

C__ , I.

The tragedy represented by tobacco smoking cannot be overcome

except through a collective effort in which all sectors cooperate,

including education, health, media, religion, agriculture, industry and

finance. In this joint effort, measures taken by governments should

support and complement efforts made by individuals and voluntary

organizations. They should all contribute to an integrated effort that

seeks to protect adolescent boys and girls from starting to smoke and

6

Dr Hussein Gezairy

Regional Director

7

The health dimension of

the tobacco problem

Four million people are killed by tobacco every year. For the

smoker, however, this does not happen out of a sudden. Death comes

as the result at the end of a long series of suffering and illness.

Tobacco smoke contains no less than 4000 chemical compounds

which are harmful; 500 of these are very harmful, and 43 are complete

carcinogens, i.e. cancer causing agents, in their own right. Smoking is

also harmful in the short term. The irritant substances in tobacco

smoke can cause a build up of phlegm and a smoker’s cough. Tobacco

smoke also reduces the efficiency of the lungs, making people more

breathless than they would normally be during situations of

rest-exercise, or sudden physical exersion. Furthermore, smoking

reduces the ability of the lungs to fight infection, which makes

smokers more likely to get different types of chest infections.

However, the worst types of the health effects of tobacco smoking

appear only after many years of continuous smoking. This is the

reason why young smokers continue to turn a blind eye to the harm

they inflict on themselves by smoking. The fact remains that a large

number of fatal and life-threatening diseases are caused largely or

entirely by smoking. These include chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, vascular diseases at various critical sites and several forms of

cancer. A study by the American Cancer Society found that 'cigarette

smokers had ten times the risk of dying from chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease than non-smokers. It also established that about

three-quarters of deaths from this disease were attributable to

smoking. In a prospective study of male British doctors,, cigarette

smokers had 13 times the risk of dying of the disease compared to

non-smokers.

The number and types of cardiovascular diseases caused by

smoking is large indeed. These include coronary artery disease and

heart attacks, aortic aneurysms which can lead to sudden death,

carotid artery disease which can lead to strokes and peripheral

8

vascular disease which, in the lower lipibs, can lead to severe pain in

the leg on walking and may necessitate amputation.

The list of diseases known to be associated with smoking includes

cataracts, hip fracture (osteoporosis), and periodontal disease.

As for cancer, it is well established that smoking is the direct cause

of the overwhelming majority of cases of lung cancer. Smoking and

alcoholic drinks are the two main causes of cancer in the oral cavity

and the larynx. When both risk factors are present, the total risk is

higher than the sum of the two risks taken separately. Other cancers

caused by smoking are those of the pharynx, oesophagus, stomach,

pancreas and bladder. Smoking is also related to other cancers in the

head and neck.

This is a summary of what tobacco smoking causes to smokers.

What it causes to non-smokers is in no way less serious or less

extensive. In its report of 1998, the British Scientific Committee on

Tobacco and Health outlines the effects of environmental tobacco

smoke, making the following conclusions:

® Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is a cause of lung cancer

and, in those with long term exposure, the increased risk is in the

order of 20%-30%.

Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is a cause of ischaemic

® heart diseases and if current published estimates of magnitude of

relative risk are validated, such exposure represents a substantial

e public health hazard.

Smoking in the presence of infants and children is a cause of serious

respiratory illness and asthmatic attacks.

Sudden infant death syndrome, the main cause of post-neonatal

• death in the first year of life, is associated with exposure to

environmental tobacco smoke. The association is judged to be one

of cause and effect.

• Middle ear disease in children is linked with parental smoking and

this association is likely to be causal.

9

In addition women g

are at an increased risk i

of cancer of the cervix as ■

a result of smoking. |

Women who smoke and 8

use contraceptive pills 8

run a higher risk of I

Deceptive and

suffering a stroke or a |

alluring

practices

heart attack. Smoking J

employed by

causes

complications |

tobacco

during pregnancy and

companies have

harms the developing baby.

successfully

Mothers who smoke put

drawn women

their own health at great

and girls into the

claws of

risk, and they also expose

smoking

their babies and young

children to all the risks of

passive smoking.

These facts give a clear indication of the magnitude of the

problems faced by health authorities as a result of tobacco smoking.

But the problem is ever on the increase. The number of smokers

throughout the world continues to rise, and a small percentage of

smokers try to quit, with only a moderate rate of success.

yields. People seeking treatment for heroin, cocaine, or alcohol

dependence rate cigarettes as hard to give up as their problem drug.

The aversiveness of nicotine withdrawal is an important factor

underlying the failure of many attempts at cessation."

Furthermore, a habitual smoker more than doubles the risk of

dying before the age of 65. The best health investment anyone can

make is never to smoke. Giving up smoking is the best measure a

smoker can take to improve his or her health. Should all smokers stop

smoking and no one light up again, more than one-third of all cancer

cases would be avoided.

Today, there are different ways to help smokers who wish to quit

the habit. These should be rpade available in hospitals, primary health

centres, pharmacies and oth^r health facilities.

It is important to remember that the choice we have is always one

between tobacco or health. The two are at opposite extremes and

cannot meet up.

Most Member States in the Eastern Mediterranean Region have

taken measures aimed at curbing the spread of the smoking epidemic.

Nevertheless, the problem is still on the increase, due to three highly

important reasons. The first is the fact that tobacco is addictive. The

Report of the British Scientific Committee on Tobacco and Health

states: "Nicotine has been shown to have effects on brain dopamine

systems similar to those of drugs such as heroin and cocaine, and with

appropriate reward schedules it functions as a robust reinforcer in

animals. Dependence on nicotine is established early in teenagers'

smoking careers, and there is compelling evidence that much adult

smoking behaviour is motivated by a need to maintain a preferred

level of nicotine intake, leading to the phenomenon of nicotine

titration, or compensatory smoking in response to lowered nicotine

10

11

Tobacco kills—don't be duped

The tobacco industry's war on public health

The tobacco industry has declared war on public health. A cigarette

is the only consumer product which, when consumed as indicated,

kills. Tobacco is a powerfully addictive substance and the tobacco

industry has subverted science, public health and political processes to

sell a product that addicts its consumer before killing them. Available

data shows that two-thirds of today's smokers started in their teen

years. Far from being a bunch of tobacco leaves rolled into paper

tubes, a <cigarette is a highly engineered product designed to addict and

kill.

Manufacturers are concentrating on the low TPM ["total

^articulate matter] tar and nicotine segment in order to

■reate brands... iwhich aim, in some^ way or another; to

reassure the consumer that these branfls are relatively more

healthy” than orthodox blended cigarettes.

P.L. Short, British American Tobacco Company, "A new Product, 1971

*

*

*

Lies and more lies

One of the primary objectives of the tobacco industry is to frame

tobacco use as an individual and behavioural decision. The deception

in this casting is that it leaves the tobacco industry's activities and

practices completely out of the equation. It assumes that people make

decisions in a state of vacuum, completely uninfluenced by their

environment including industry advertising and marketing.

“The tobacco companies spend US$6 billion a year enticing youth

to smoke. They make you believe that if you smoke, you re going to

be sexy, attractive, successful, accepted by your peers, rocking, and

macho, cool and sassy. They project this image in every media —from

day time movies to night-time movies, magazines and even cartoon

12

characters,” says former “Winston” man turned tobacco control

activist Allan Landers.

Research indicates that the decision to smoke is affected by

tobacco industry promotion. Tobacco advertising featuring prominent

sports and entertainment figures project an image of tobacco use as

glamorous, fun, healthy, sophisticated and wealthy. In countries

where advertising bans are beginning to emerge more subtle product

placement in movies and music videos continue to send these

messages to young people. By the time people find out, it is often too

late.

*

*

*

The threat concerns us all

The tobacco industry acts as a global force sparing no nations and

peoples. There are no true economic or public health arguments in

favour of tobacco as it kills human beings and saps national treasuries.

Tobacco has killed four million people this year. By the 2020s or the

early 2030s, that preventable death toll will rise to 10 million deaths

per year. The tobacco industry and their marketing henchmen need

some 11 000 new smokers every day to replace those they kill. So

they target our children and sell addiction and death as an act of

freedom, rebellion, free choice, sophistication and success.

to ensure increased and longer term growth for the Camel

Filter, the brand must increase its share penetration among

the 14-24 age group which have a set of more liberal values

and which represent tomorrow's cigarette business.

1975 Memo to C.A. Tucker, Vice-President For Marketing, R.J. Reynolds

*

*

13

*

'•#

®

■“

Chuntering the deception

Every eight seconds a person dies of a tobacco-related disease and

almost as quickly another victim is recruited. Big tobacco trades in

death and decepijog^his assault on world health has got to stop. The

WHO has risen to this global challenge. At the core of this response is

the creation of Jhe world’s first legally binding international treaty

dedicated to human health. The WHO Framework Convention on

Tobacco Control (FCTC) will address such issues as advertising bans,

smuggling, taxes and agricultural diversification with a view to

crafting a global response to a global menace.

I

As tobacco control action begins to reduce markets in the west,

transnational tobacco companies are aggressively extending their

global reach. The FCTC will provide a powerful political platform

upon which all the nations of the world can unite and strengthen their

capacities to counter the deadly and deceitful cross border tactics of

the transnational tobacco companies.

If you still believe the industry is simply stuffing tobacco into

paper tubes, not fine-tuning nicotine delivery, consider this

quote from a senior scientist working for a tobacco

company, uncovered recently from a longfhidden document.

In 1972, he said: athe cigarette.should not be construed as a

product but a package. The product is nicotine. Think of the

cigarette as a dispenser of a dose unit of nicotine. Think of a

puff of smoke the vehicle of nicotine. ”

bans, etc) is not known in Sri Lanka or Mexico. On the other hand

unregulated marketing to youth and women in developing and

developed countries in transition (cigarette discos, golden cigarette

contests, etc) which are systematically denied in the west have not

been sufficiently exposed. To ignite this tobacco curtain and build

global support for the FCTC, the WHO has developed the “tobacco

kills-don’t be duped” media initiative.

This new media initiative will systematically attempt to reframe

public perception of the tobacco problem by giving the health and

political community the tools needed to begin to expose and combat

the enormous resources and deceitful tactics of the transnational

tobacco companies.

Obviously there is enormous potential in all these countries.

I would say that the demand for Western cigarettes is

insatiable. It's a fantdstic opportunity for everybody, and

we're talking in any number of countries.

Stuart Watterton, BAT Director of New Business Development speaking of new

opportunities iniEastem Europe and the former Soviet Union, 1995

They've got a good buffer. No matter how badly things go in

the United States, international sales will carry them along.

Allan Kaplan, tobacco analyst at Merrill Lynch & Co. commenting on Phillip

Morris, 1997

WHO Director General Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland to the Ninth International

Conference of Drug Regulatory authorities, Berlin, 27 April 1999

*

*

*

Igniting the tobacco curtain

Key to big tobacco extending its global reach has been aggressive

marketing and advertising and the creation of a new “tobacco iron

curtain”. What is going on in the west (European Union legislation,

huge tobacco company settlements in the United States, advertising

14

15

From the horse’s mouth:

the tobacco industry speaks

I do not believe that nicotine is addictive.

Thomas Sandelfur, Chief Executive of Brown & Williamson

*

*

*

Recent rcvekitions of corporate documents disclosed in litigation

and associated Wstigations, give compelling evidence for the

longstanding interest of various tobacco companies in young smokers.

The following is an ovendew of statements made by these companies.

Evidence is now available to indicate that the 14- to 18year-old group is an increasing segment of the smoking

population. RJR must soon establish a successful new brand

in this market if our position in the industry is to be

maintained over the long term.

RJ Reynolds planning forecast stamped "secret", 15 March 1976

J believe that nicotine is not addictive.

William Campbell, Phillip Morris

*

*

*

And I too believe that nicotine is not addictive.

James Johnston, R.J. Reynolds

CEOs testifying under oath before Congressional Health and Environment

Subcommittee, 1994

Our attached recommendation...is another step to meet our

marketing objective: To increase our young adult franchise.

To ensure increased and longer-term growth for Camel

Filter, the brand must increase its share penetration among

14-24 age group which have ajnew sit of more liberal

values and which represent tomorrow's cigarette business.

23 January 1975

*

*

*

Nicotine is addictive. We are, then, in the business

of selling nicotine, an addictive drug.

Addison Yeaman, Brown & Williamson, 1963

over the iong

...if our company is to survive afid ffrpsper,

term we must get our :share, of the youth market. In my

opinion this will require new brands tailored to the youth

market.

Claude Teague, RJ Reynolds, Researcher, 1973

*

*

*

Smoking and cigarette for the beginner is a symbolic act. 1

am no longer my mother's child, I'm tough, I am an

adventure, I'm not a square... as the force from the

psychological symbolism subsides, the pharmacological

effect takes over to sustain the habit...

Phillip Morris, Vice President for Research and Development,

"Why One Smokes," first draft, 1969

16

If the last ten years have taught us anything, it is that the

industry is dominated by the companies who respond most

effectively to the needs of young smokers.

Overall Market Conditions 1988, Imperial Tobacco Ltd (TTL)

Since how the beginning smoker feels today has implications

of

for the future of the industry, it follows that a study

:

. this

17

Another popular means of keeping cigarette brands in the public

eye and circumventing restrictions on advertising using cigarette

logos on other products such as caps and t-shirts. Many of these

products are popular with children around the world, and they soon

become walking cigarette advertisements.

Counteradvertising can be a useful addition to a tobacco control

campaign

Excitement, adventure and masculinity., harsh

strong psychological pressure is exerted by the

tobacco industry on children and young people

through advertisement

area would be of much interest. Project 16 was designed to

do exactly that-leam everything there was to learn about

how smoking begins, how high school students feel about

being smokers, and how they foresee their use of tobacco in

the future.

Ads for teenagers must be denoted by lack of artificiality,

and a sense of honesty

Serious efforts to learn to smoke occur between ages 12 and

13 in most cases.

The adolescent seeks to display his new urge for

independence with a symbol, and cigarettes are such a

symbol since they are associated with adulthood and at the

same time adults seek to deny them to the young.

Kwechansky Marketing Research Inc, Report for Imperial Tobacco Limited,

Subject: "Project 16", Date: 18 October 1977

18 ,

In countries around the world, young people are exposed to highly

effective tobacco advertising on a daily basis. Tobacco companies

spend billions of dollars each year to promote tobacco products, an

amount which dwarfs the resources available to most tobacco control

programmes. Thus, one important requirement for an effective

prevention programme is to seriously limit the ability of the tobacco

industry to hook a new generation of smokers through advertising.

At the’ same time, a number of countries have produced

anti-tobacco advertisements for distribution via mass media. Many of

these ads are targeted at young people, with the aim of

de-glamourizing tobacco. There are often possibilities for free

distribution of these ads in the form of public service announcements.

However, they are only useful if they are seen, and not broadcast only

during times when most viewers are asleep. In some • situations,

carefully selected paid counter advertising campaigns may be worth

the cost. In the USA, Doctors Ought to Care (DOC) pioneered the

concept of using paid counteradvertising to ridicule brand name

tobacco advertising and promotion.

Health interests can never hope to match the spending by tobacco

interests on paid media advertising, and probably should not try.

However, paid media advertising, when used with precision, can be an

effective tool in a comprehensive effort to discourage tobacco

consumption. One way of funding this would be to use a portion of

increased cigarette taxes for this purpose. Examples of this strategy

may be seen in several states in the USA as well as in other countries,

such as Australia, France and New Zealand.

■*

»

19

Reducing the glamourization

of tobacco in movies,

on television and in music videos

Four steps the entertainment industry can take to reduce the

glamourization of tobacco:

When tobacco is glamourized in movies, on TV and in music

videos, it sends a powerful message to young people that tobacco use

is both appropriate and desirable.

Following are four steps the entertainment industry can take to

discourage teenage tobacco use:

1. Avoid glamourizing tobacco. Refrain from portraying tobacco use

as something that is exciting, cool or sexy and linking tobacco with

adventure, fun and celebration.

2. Creatively substitute other props. Consider means other than

tobacco-type cliches for portraying rebellion, celebration and

relaxation.

3. Portray the reality of tobacco use. People become sick and die from

using tobacco. Most smokers would like to quit but have a difficult

time because of the highly addictive nature of nicotine.

Environmental tobacco smoke impacts the health of non-smokers.

The majority of people in the world do not smoke and prefer to live

in a smoke-free environment.

4. Work toward reducing overall tobacco use. Avoid creating an

image that smoking is a normal, daily activity. Refrain from having

characters use tobacco in inappropriate situations such .as around

children, in medical care facilities and in non-smoking areas.

rarely reflect realityi Tobacco use is not exciting or glamorous. Many

stars have died from tobacco-related diseases.

Encourage others to watch what they are watching. As a young

person, talk with yourfriends about tobacco use in the movies and on

TV. As a family, watch movies or TV and discuss the difference

between the portrayal and reality of tobacco use. As a teacher or youth

group leader, consider teaching a unit on critical viewing skills.

Work to raise public awareness. Host local youth-based media

events around the time of the Oscars or your local award ceremonies.

Contact your local movie and TV critics and ask that they write

articles on the issue. Copy and distribute this packet at health fairs,

World No Tobacco Day, and other events that promote health and/or

tobacco education. Be creative!

Why is tobacco included in movies and on TV?

There are several reasons why tobacco finds its way into movies

and TV programmes.

It is a convenient prop. If yow^anf,,to establish that a teen is

rebellious put a cigarette in his or her fend.

It may depict reality.

It can reflect the personal attitudes alid use of tobacco by writers,

directors, actors and actresses. Itinay result from direct or indirect

influence by the tobacco industry.

It may be used its a marketing tool to reach specific audiences.

Do a study

Watch what you are watching. Inoculate yourself against the

pro-tobacco messages you receive from entertainment productions.

Recognize that movies and TV are for entertainment and that they

Many studies have been conducted to test the manner and

frequency of tobacco usage in the movies and on popular television

programmes. An example of one such study comes out of California

in the United States. It was conducted by Thumbs Up! Thumbs

Down!, a project of the American Lung Association of

Sacramento-Emigrant Trails. The study looked at all movies with a

domestic box office income of more than $5 million in the time frame

from May 1994 through April 1995. It reviewed television shows over

20

21

Three other actions that will make a difference

six-week period in the spring of 1996. These are movies and

programmes that are screened all the world, not just the US, and have

enormous appeal to teenagers everywhere. Following are the key

J

1h

j .•

findings:

. L;-.

Hollywood gets a Thumbs Up! and a Thumbs Down.'m the amount

of tobacco use. Approximately 50% of the 133 movies reviewed had

zero to 10 incidents of tobacco. The other half ranged from a moderate

11—20 incidents to a smoke-filled 100 plus incidents. Television fared

better with only 15% of the 238 episodes watched containing tobacco.

Overall, movies averaged 10 incidents per hour and television two.

Use varies considerably by studio and network. Studios with low

tobacco use included Walt Disney Pictures, Twentieth Century Fox

and Hollywood Pictures. On the high side were Miramax, Castle Rock

and Warner Brothers. On television, ABC had the lowest incidence

while Fox was highest.

Leading actors are more likely to light up in the movies. In the

movies and television programmes which included tobacco use, one or

more leading actors and actresses lit up 82% of the time in movies and

57% of the time on TV.

^.j are the tobacco of choice. In the movies

Cigarettes and cigars

86% displayed

cigarette use, 52% cigar use,

where tobacco was used,

i

...

12% pipe use and 7% smokeless tobacco. On television episodes with

tobacco use, 67% displayed cigarette use, 42% cigar use and 3% pipe

use. There was no smokeless tobacco use displayed.

So what if your favourite actor lights up on screen?

The entertainment industry has a pervasive influence on our

society. While movies and television may reflect our life styles, they

also help define them. The power of the entertainment industry in

influencing young people suggests that it also has a responsibility to

monitor and reduce the potentially negative impact of its messages on

this audience. One area where it can play a particularly important role

is in helping to discourage tobacco use.

22

.jH,

©®

i:.

me iaiiiuus actor auh juiiaiii nas quit smoking, deciding for himself

without waiting for a doctor recommendation. As a respectable

actor, he will surely stop using cigars or cigarettes in the ads for his

works.

Bask tobacco facts

Tobacco kills 4 million people a year around the world. According

to the World Health Organization, it is the single most preventable

cause of death and disease in the world. In addition to the tremendous

suffering it creates, tobacco use costs the United States alone close to

$100 billion annually in health care and days missed from work. Do

you know what the costs are in your own country? It is a price we all

help pay, whether we smoke or not.

Adults don't make the decision to start smoking: young people do

Each day between 82000 to 100000 teenagers light their first

cigarette. Tobacco use starts in early adolescence. Almost all

first-time use occurs before graduation from high school. People who

start smoking at an early age are more likely to develop severe levels

of nicotine addiction and are more likely to die early of a

tobacco-related disease than people who start later.

Why do young people start? A teenager is much more likely to

light up if his or her parents, brothers or sisters smoke. Peer pressure

is also a powerful influence. The most common offer of a first

cigarette is from a friend. Certainly, the massive advertising campaign

carried out by the tobacco- industry plays a part. Billions go toward

23

It represents rebellion. Lighting up becomes a symbol for

challenging a repressive system, whether that system is your parents

or the government.

It's a way of relieving stress. As tension mounts, people light up.

making the Marlboro Man and his counterparts attractive to children.

Whether it is popularity, beauty, adventure, wealth or uniqueness, the

tobacco industry and its legion of public relations firms have a

multitude of ways suggesting it can be had for the price of a puff. Kids

with low levels of self-esteem and a sense of alienation are especially

vulnerable to the industy's relentless campaign.

Che rale off the entertainment industry

What role does the entertainment industry play in this process'?

When tobacco is glamourized in movies, on TV and in music videos,

it provides a powerful message that tobacco use is an appropriate and

even on desirable activity. Whether the glamourization is intentional

or not, it reinforces the multi-billion dollar advertising campaign

carried out by the tobacco industry. In some ways, it may be even

more effective. No warning label is required when actors and actresses

light up. What the young person sees is someone he or she looks up to,

living a life that he or she would like to live, and doing it while using

tobacco.

I

^LM x^|

I

Creativity has nothing to do with smoking. A successful person is not

necessarily a smoker and should not be.

There are three major ways tobacco use is glamourized:

It's fun. Cool, attractive and successful people light up and they use

tobacco while they are doing exciting things.

Advocacy activity for teens

Youth advocacy efforts are an important way to reduce the

influence and amount of positive tobacco portrayal in movies and on

television. Here are some suggestions:

1. Teens can write to the actors and actresses to express their concern

over how tobacco use is portrayed on screen. Simple form or

hand-written statements or letters to actors/actresses, production

companies, or anyone actively involved in decision making, will let

them know that the amount of tobacco use does not go unnoticed

and is undesirable. The youth may also send letters of recognition

to those who convey an anti-tobahco message to encourage and

congratulate their efforts.

2. Produce a slide with an anti-tobacco message that could be shown

prior to movie trailers previews: Contact your local theatre to find

out if they will show it.

'

3. Send it petition to-a particular actorrd^W or producer signed by

youth. This petition can b^fes Otf concern regarding how

tobacco is being portrayed.

4. Do a pre and post test at a movie theatre. Survey moviegoers about

their impression of tobacco and cite some facts. After the movie,

survey the same audience to see if their impression/reaction

changed.

5. Get permission from a movie theatre and hand out a movie

evaluation form for the audience to fill out. For example, the

release of the Hollywood movie "The Insider" may be a good

opportunity to do this.

6. Have youth create a list of movies that contain smoking scenes.

24

25

7. Encourage teens to write letter/article in a school newspaper.

Include a list- of celebrities who have died from smoking related

diseases. (See list of celebrities killed by tobacco)

These are just aTew of ways to encourage critical thinking while

deglamourizing tobacco use. The goal is to encourage the movie and

television industry to stop portraying tobacco as being a desirable

activity.

Watch what you are watching

How do your country’s movies and television programmes fare? It

Would make for an interesting project. Why don't you find out?

Whether you are sending a message to Hollywood or your local

entertainment industry, discussing tobacco use with your family, or

working on a class or group project, the following questions and

methods utilized by the Thumbs Up! Thunks Down! project should

help in your efforts.

How much tobacco use is shown? The easiest way to determine the

extent of tobacco use is to count intfeits. V^ile there are various

ways of counting, the method used by ^umbs^p! Thumbs Down! is

to count each time tobacco is shown pi^f^jp^en as an incident. For

example, two people smoking at ^e^:$^0^finie on screen are

considered two incidents. When a handfhol&rig a cigarette moves off

screen and then back on and when a camera refocuses on a person

smoking are also considered separate incidents. More than 30

incidents in a movie and over 10 incidents on a television programme

reflect relatively high use.

What type of tobacco is being used? The type of tobacco being

used in movies and on TV can encourage or discourage certain trends

in tobacco use. For example, the prominent use of cigars in recent

movies and TV shows in the US has likely played an important role in

the increasing incidence of cigar use in the US.

Who is using tobacco? Major characters who are played by popular

actors and actresses carry out much of the tobacco use in movies and

on TV. Many of these characters, actors and actresses serve as role

26

models to young people. When these role models light up, it sends a

powerful message that smoking is OK.

How is tobacco use being portrayed? The way tobacco use is

portrayed is an all-important factor in encouraging or discouraging

tobacco use. When the entertainment industry shows tobacco use as

fun, it suggests it’s a way of rebelling and establishing independence,

or shows it as a means of relaxing and dealing with stress, it sends a

message that using tobacco is a highly desirable activity. When the

entertainment industry suggests that tobacco use is unhealthy or

addictive, portrays a character strenuously objecting to breathing

second-hand smoke, or shows some of the more unattractive aspects

of tobacco use such as smelly clothes and stained teeth, it sends the

message that one should avoid tobacco use.

1

27

A message to all youth

from Dora'd Lahham

I was a heavy smoker, and I would not

refrain from smoking for any reason despite

my knowledge that it is harmful. I even

realized that smoking could easily send me to

my grave. Later, I began to feel that I should

quit, and made several attempts but withput

success. I asked several people who were

able to quit how did they manage to break

loose of the bondage of this killer, which we

imagine it to be give us enjoyment when it

is truly a killer. Whatever I tried in this

respect ended in failure, until a moment arrived

when my worst fears came true. I suffered a blockage of my arteries

which doctors attributed to smoking. This led to the fact that blood

supply to my heart was severely disrupted. Had it not been for God's

mercy, I would have been one among the millions that tobacco kills

every year.

Smoking is a very deceptive habit. We think of it as a source of

some pleasure or enjoyment, and we take it up unaware of the risks to

which it exposes us. It all starts with a cigarette offered to you by a

friend, which you may wish to try because you think it may be

pleasant, or you may think that it gives you a bridge to cross over in a

few minutes to the stage of being an adult. But it is a bridge of smoke

that kills. It is then a matter of one cigarette after another until we slip

into the stage of nicotine addiction. Then the realization creeps in that

smoking is a total evil, with no positive aspects and no .enjoyment

either. It is simply a mechanical habit that enslaves human beings.

Then the smoker is torn apart between his awareness of the risks that

engulf him and those he loves as a result of continuing to smoke and

his inability to break his chains and quit his habit.

28

Some smokers may do like I have repeatedly done, entertaining a

wish to quit but feeling unable to do so. I would seek help and aids;

such as a nicotine patch or some medication which is supposed to turn

you off smoking. But none of this works, because my resolve to quit

has not been strong enough. Then thoughts of what I may have to

endure after quitting blacken my day and return me back to smoking.

Then the moment of truth arrived. I discovered that it is all a matter

of decision and resolve to break the chains and save myself, my health

and the health of those who are very close and dear to me. I felt that it

is imperative for me to pause and reflect, and to take the decision to

stop once and for all this hazardous and ruinous habit. I felt that I had

to take that decision, even in the form of a vow to commit myself

privately and publicly and to honour my resolve.

The point is that it is all a personal decision, commitment and

resolve. I have made that resolve and I praise God for having enabled

me to quit smoking. As it turned out, nothing of my initial fears have

had any real substance. I have not felt any crave to take up smoking

again. I have not been a victim to intolerable suffering. Now I feel

smoking to be repugnant. I wish I had had the courage to quit earlier.

Indeed I wish I had the courage to say no to the first cigarette when it

was offered to me. I would have then spared myself much trouble and

much suffering.

All that it takes, then, is a little reflection and clear thinking.

Smoking kills in different ways. It destroys our health, wastes our

money and time. All that goes up in smoke. What we are left with is

utter ruin.

A final word to all young men and women:

I was young like yourselves. But now at my age, I remember, with

no good thought, my friend who encouraged me to light up the first

time. Hence, I hope that you have the awareness and the courage to

refuse the first cigarette and save yourself and your friends much

suffering.

29

Tobacco control legislation

and its implementation

By

Abdullah Al-Eissa

Vice President, High Court, Kuwait

i

•I

When the wide range of risks smoking represents became well

established, and the health hazards it poses to smokers and

non-smokers were identified, governments and legislative authonties

began to take measures that seek to contain its effects. Some countnes

issued some laws and regulations which aim to control smoking by

banning tobacco advertising, and restricting smoking in enclosed

public areas. They also made certain specifications with regard to the

contents of tobacco products. Legislation is a good and effective tool

of social control. Legislation may provide for the restriction of certain

practices that are deemed hazardous, or represent an unjustifiable risk

to human life, health or wealth. Its provisions may outline the

principles of accountability and imposes penalties that fit with the

aims and purposes of the legislation. Legislation must always be

suited to the circumstances prevailing in society. It must have some

essential qualities that make it suitable for implementation. Only m

this way can it become an effective way to achieve the purposes for

which it has been promulgated.

While this applies to any piece of legislation that aims to establish

social controls and serve certain public interests, like tobacco control

legislation, a number of prerequisites must be fulfilled for it to work

out. These are:

1. Those who are entrusted with its implementation must have no

personal interest that is contrary to tobacco control;

2 The authority supervising implementation should be seen to

' provide a good example. This is achieved through conviction of its

usefulness and a complete commitment to the fulfilment of its

objectives.

30

3. Maintaining justice in implementation. No piece of legislation

should ever be applied to one sector of the population while others

are exempted. No regulation could apply to one company and not

to another. Yet in practice we see that in both industrial and

developing countries legislation banning tobacco advertising have

been applied to radio and television, but not to press. We also see

that the ban on smoking in public places has been welcomed in

Western countries, while its implementation in the developing

world, including Arab countries continues to leave much to be

desired. It is a simple fact to say that restricting smoking in public

places and transport is the responsibility of three different bodies

which must cooperate to ensure the achievement of the aims of

legislation. These are:

a) The smoker, since he is the one who represents the problem and

bears the burden of compliance with regulations;

b) The non-smoker, who is, in this respect, the victim. The nonsmoker is an important actor in such a situation. He should

make clear his disapproval of smoking, particularly if he

happens to be in close proximity to the smoker, suffering the

effects of passive smoking. He should be able to seek help from

the person in charge of maintaining the regulations in that

place, should the smoker insist on contravening those

regulations. It may be suggested that an effective means to

ensure compliance is to file a case against the smoker, claiming

compensation for what he may cause of health risks to the nonsmoker. This, is correct to some extent. What is needed though

is a proof of the damage that a particular person may

experience, as in the case of both smoker and non-smoker share

the same environment for a certain period of time. Moreover,

the court must conclude that there is a causal aspect that

requires compensation. Needless to say, the difficulty of proof

in such cases makes such a law suit very rare. This means that

seeking compensation through the court is not reliable as a

means of restricting smoking in public places. Nevertheless,

judgement has awarded qgjjiggnsation to those affected as a

11

yarns’

result of passive smoking in the US and Sweden. But this

judgements were not awarded against the smokers but-against

the authorities in charge of the place;

c) The authority responsible for the public place or the means of

transport, as the one responsible to implement the regulations in

that particular environment. Such an authority should always

move to protect non-smokers, taking issue with the smoker who

tries to breach the regulations and pointing out to him the need

to comply. Should he persist, then the punishment specified in

the regulation must be implemented.

That apart, implementation differs according to the provisions of

the law A provision requiring the tobacco industry to reduce nicotine

and tar contents is one for an appropriate government department to

ensure compliance. This may be the ministry of health, a consumers

affairs authority or some other. The same applies to a regulation that

requires staff in restaurants not to smoke when they are preparing

meals for their customers. Since monitoring this aspect falls within the

jurisdiction of the authority in control of food and beverages,

whatever the law provides in this area also falls under its jurisdiction.

Regulations that ban advertising in the media may be primarily

addressed to tobacco companies which are responsible for compliance

with the restrictions imposed. However monitoring implementation is

the responsibility of ministries of information. Certain countries may

issue regulations banning the sale of cigarettes to those below a

particular age. This aims to protect the youth from smoking, and

rightly so. Nevertheless such provisions may remain rather advisory

because of the difficulty of implementation. This is partly due to the

availability of vending machines and the availability of cigarettes in

the supermarkets. It is difficult to require shopkeepers to demand a

proof of age from every young person buying a packet of cigarettes.

Even then it is not difficult to dodge such requirements.

Let us now look at the role of legislation in tobacco control. The

most important points are:

(a) Means of compliance

It is inconceivable that the promulgation of legislation restricting

smoking in certain places and imposing a partial ban on advertising

can achieve the overaU objective of tobacco control. Even the best

legislation will not rid the community of a problem of such a large

magnitude as the tobacco problem. Nor is it possible for the law to

check the tobacco epidemic without concerted efforts exerted by

several sectors working in unison and committed to achieve a tobacco

free society. With such an aim in mind, action must follow two lines

in parallel: firstly, legislation which provides an antismoking legal

forum, and, secondly, an information campaign which supports

legislation by enhancing people's awareness of the hazards of tobacco

and its harmful effects on physical and mental health, as well as its

negative economic and social effects. Such a campaign should benefit

by contributions from medial doctors, religious leaders, media experts,

artists and people who may influence public opinion.

Such efforts must always employ innovative methods and put its

message across in new styles and fresh language.

To fund such efforts, it is most-appropriate that a special tax or

increased custom tariff should be imposed on all tobacco products,

with the revenue allocated for this purpose.

(b) Implementation

When legislation provides for different restrictions and controls

falling within the jurisdiction of different departments and authorities,

responsibility for its implementation will be diverse. However, in the

case of tobacco control we may identify two types of authority:

(1) Authorities that are close to the public, particularly those in

control of public places, such as schools, hospitals, clubs,

government offices, company buildings, etc. Public transport also

comes under this group. Needless to say, implementation in such

places falls on the respective administration of each such place.

(2) Government authorities. Each department or authority should be

assigned responsibility for the enforcement of laws and

33

32

I

regulations that fall within its particular jurisdiction. The

legislature may assign responsibility for issuing enforcement

regulations to different departments. In Kuwait, this role has been

assigned to the Minister of Health. Moreover, article 9 of the

Kuwaiti law gives the Prime Minister and other Ministers

responsibility for implementing the law within their respective

jurisdiction.

(c) Foiling attempts by the tobacco industry to circumvent the

law

Sports

events are

used by the

tobacco

industry to

promote

smoking

j

i

I

d^«

. m ?u

h**

iliXAat £>4 *6-* j-1A-

.X^U-JI jUW<^

*’LJ3

J—*M-*U

wu>

1M

i**U^ Ji^AU

<^* *^*

Ui4^JU^Aa--^

^3<

The tobacco industry utilizes various tools and means to promote

its products, circumventing the laws aimed at tobacco control. In its

attempts to counter the effects of legislation, it employs highly

innovative methods and allocates large budgets. Its efforts include.

© Media advertisments, particularly in papers and magazines,

® Billboards and posters on large buildings and public transport

and in shops and sale outlets;

© Indirect advertising through sponsorship of sports, cultural and

social events;

oo

34

® Promotional products and souvenirs that carry the name of

tobacco brands.

Some countries have enforced strict bans on tobacco advertising in

television^ while others have not imposed such a ban. This limits the

effect of such bans in this age of satellite channels that are monitored

across geographical boundaries. The same applies to the press as

advertising bans apply to national press, while it does not apply to

newspapers and magazines published in other countries. It must be

said that advertising may be very seductive with certain sectors of the

population. Hence very large financial and artistic resources are

allocated to it. Indeed the tobacco industry provides such resources

with the aim of circumventing the law and reaching the public.

This means that we need concerted international efforts, through

the United Nations and its specialized agencies, to work out protocols

that apply to all media channels. Even then the enforcement of such

protocols by private papers and media channels is far from easy.

Nevertheless efforts in this regard must continue, even if that requires

making special agreements with the tobacco industry to stop

advertising for a specified period.

Special efforts should be made to provide the media with

alternative sources of advertising in order to compensate them for the

loss of revenue that results from banning tobacco advertising.

It is my firm conviction that strict implementation of the laws

banning tobacco advertising would have made such promotion efforts

by the tobacco industry a definite breach of the law both in letter and

spirit. It is not to be expected that the tobacco industry will stop its

efforts in this regard, having realized that they are more effective than

direct advertising.

(d) Model integrated legislation

When countries adopt model integrated legislation, numerous

contradictions that now prevail because of the existence of many

different local regulations will be removed. It is important that such

model legislation should incorporate the following principles:

35

Islamic ruling on smoking

(1) The essential rule must be that smoking is banned in any public

place, unless there is a specific exemption allowing it. This is

contrary to what most existing laws provide for, making

smoking in public places permissible unless it is restricted by a

specific legal provision. This rule is the one adopted by the law

in Finland;

(2) Countries that at present do not have tobacco growing or a

tobacco industry should have the right to ban the initiation of

any such activities. On the other hand, the ban should be

limited to any expansion of the present scale of tobacco

growing and tobacco industry in countries where such

activities are at present available. This ban should apply in the

latter group of countries until alternative crops or industries

have been established;

(3) A ban should be imposed on all smoking in all means of

transport including all flights;

By Professor Youssef al Qaradhawi

It is now four centuries since tobacco appeared and began to be

used by people. Scholars at that time felt that they needed to issue a

ruling on tobacco use. As the practice was new and without an earlier

ruling by eminent scholars in previous generations, scholars differed

widely in their ruhngs. Another factor contributing to such differences

was the absence of a proper scientific study explaining the nature of

tobacco and the effects of its smoking. One group felt that it should be

prohibited, another considered it reprehensible or discouraged, and a

third group viewed it as permissible. Some others felt unable to issue a

clear ruling on it, preferring to wait for further evidence about its

effects. In each one of the four Sunni schools of thought we find

scholars adopting any of the aforementioned rulings. This means that

no school of thought was associated with any particular ruling of

permissibility or prohibition of smoking.

(4) A ban on all tobacco advertising should be imposed, whether

direct or indirect, including sponsorship by tobacco companies

of any sports, social or cultural.events;'

Weighing up the arguments

It seems to me that the controversy'among scholars of different

schools of thought at the time when smoking began to spread was not

the result of a difference in the basis on which scholars deduced their

verdicts. It was perhaps due to how they viewed tobacco and its

effects. Some of them felt at the time that smoking resulted in certain

benefits; others thought that its harm was limited and counterbalanced

by some benefits; others still, felt that it had no benefit whatsoever,

but they were unsure that it caused any harm. What this boils down to

is that scholars would have not hesitated to rule that tobacco was

forbidden, had they been aware that it caused definite harm.

(5) Strict limits should be imposed on the nicotine and tar contents

of all tobacco products, including the contents in each

cigarette. These limits should be published on every packet;

(6) Every packet of all tobacco products should carry a health

warning. Regulations may outline the conditions that

such warnings should meet. Health warnings must be

varied, with several warnings given to tobacco

companies for a certain period, then replaced by another

set of warnings for a similar period. The warning should

be prominent on both main sides of the packet, with a

specified perceritage of the area of the packet allocated to

the health warning. The writing should be clear, with

specified colours to make it very prominent.

36

At this point we must make it clear that the task of proving physical

harm caused by tobacco or any other substance is not something that

Islamic scholars should undertake. It is the responsibility of medical

doctors. It is to them that we must refer in this area because they are

a

37

1

L

the experts. Islam requires us to refer to the experts on any matter: Put

your questions to someone in the know (25: 59).

Medical doctors have made clear statements concerning the

harmful effects tobacco smoking causes to man’s general health, and

its particular effects on the smoker’s lungs and respiratory system in

particular. They have emphasized that it is the major cause of lung

cancer. Hence, the whole world has started recently to call for action

against smoking.

II

In our present times, scholars should be unammous in their verdict

on tobacco smoking. A scholarly ruling on this must be based on

medical evidence. Hence, when the doctor says that this practice, i.e.

smoking, is harmful to health, the religious scholar must say that it is

forbidden. Whatever causes harm to human health must be forbidden

in religion.

Yet in respect of smoking, certain aspects of harm need neither a

medical doctor nor a laboratory to confirm. They are well known to

the public at large.

■i

r>

The rationale

Some people may ask: how can you prohibit the use of a plant

without a clear statement? The fact is that it is not necessary that

every prohibited matter should be mentioned by name. Religion lays

down certain rules and principles which may apply to numerous

matters. It is not difficult to outhne the rules, but it is impossible to

enumerate every single matter. It is sufficient to make a rule

prohibiting what is foul or harmful to include under it a large number

of harmful types of food and drink. Hence we find scholars returning

a unanimous verdict of prohibition on cannabis and other drugs,

although there is no statement prohibiting them in particular.

■i.

because the Prophet says, God has decreed that every thing to be done

must be done well. Whoever causes himself or others harm does not

do well. When a person does not do things well, he contravenes God's

decree to do things well. Other evidence that may be cited in support

of this verdict is the Prophet's statement, There shall be no infliction

or harm on oneself or others, and the Quranic verse, Do not kill

yourselves. God is most compassionate to you (4:29).

Among the most comprehensive statements on the prohibition of

eating or drinking harmful substances is this quotation from Imam Al

Nawawi "Whatever causes harm when consumed, such as glass, stone

and poison, is forbidden to eat. Every substance that is not impure and

causes no harm is permissible to eat except what is considered

disgusting, such as semen and mucus. These are certainly forbidden.

It is also permissible to take a medicine that may contain mild poison,

if it is needed and it is, in the considered expert's view, safe to take.

I

The financial aspect

It is not permissible for man to spend his money on something that

brings him no benefit either in this life or in the life to come. Man is

placed as a trustee in charge of his wealth. Thus, both health and

wealth are blessings God has given us. It is not permissible for any

person to impair his health or waste his wealth. The Prophet has

forbidden the wasting of money. A smoker pays his money to buy

what causes him definite harm. That is certainly forbidden. Moreover,

God says: Do not be wasteful, for He does not like those who ate

wasteful. (7:31).

No scholar takes religious statements at face value as strictly as

Imam Ibn Hazm. Nevertheless, he makes it clear that harmful food is

prohibited. In this he rehes on the general sense of religious

statements. To quote Ibn Hazm: ’’Whatever causes harm is forbidden,

The psychological aspect

The psychological aspect of harm is often overlooked by people

who write on tobacco. The point is that when smoking becomes a

habit, the smoker falls in the grip of this habit and cannot get rid of it

easily. It soon becomes an addiction which robs smokers of their will.

Smokers are thus unable to stop it, even when they need to do so,

either because its physical harm becomes excessive, or to set a good

38

39

example for their children, or because they need the money wasted on

tobacco for some beneficial purpose.

In actual fact tobacco enslaves smokers. Hence, a smoker

sometimes gives priority to buying cigarettes rather than spending his

little money on buying food and other essentials for his family.

Should such a person be compelled to refrain from smoking for any

reason, whether personal or enforced, his general condition suffers,

and his judgement becomes easily impaired. He may become highly

irritable. Such harm makes it necessary to issue a ruling concerning

tobacco smoking.

Smoking is foirbidden

There is no way that any scholar could issue a verdict of

permissibility on smoking, after the medical evidence of the harm it

causes has become so strong, and supported by a large number of

medical and scientific authorities. Indeed the extent of the harm

caused by tobacco is now common' knowledge, supported by

indisputable figures.

Since a verdict of complete permissibility of tobacco smoking

cannot be given, then the only verdict possible is to consider smoking

either reprehensible or forbidden. It is already clear that a verdict of

prohibition is more valid and relies on stronger evidence. This is my

ruling, based on the fact that habitual smoking will inevitably cause

certain harm physically, psychologically 'and financially. Indeed

whatever is harmful to health is prohibited in religion.

God says in the Quran: Do not, with your own hands, cast

yourselves to destruction. (2:195) He also says: Do not kill

yourselves; God is ever most merciful to you. (4.29) He also

denounces wasting money in several verses of the Quran: Do not be

wasteful, for He does not like those who are wasteful. (7:31) Do not

squander [your wealth] in the manner of a spendthrift, Indeed

spendthrifts are the brothers of Satan. (17:26-7) The harm caused to

health and wealth by smoking is most definite. Indeed taking any

thing that is injurious to health is forbidden on the evidence of God's

commandment: Do not kill yourselves. (4:29) Hence we must rule that

smoking is definitely forbidden.

In point of fact, medical doctors are unanimous that smoking

causes certain harm. It is true that the harm in this case is cumulative,

not immediate, but a slowly active harmful substance is forbidden in

the same way as a rapidly active one. It is forbidden for anyone to

take a slowly acting poison just in the same way as it is forbidden to

take an instantly killing one. All suicide is forbidden in Islam, whether

slow or instant. A smoker kills himself, or herself, gradually.

Moreover, it is not permissible for a human being to harm or kill

himself or others. Hence the Prophet says: "There shall be no

infliction of harm on oneself or others". As it is unanimously agreed

by medical doctors that smoking represents definite harm to human

beings, countries of the world have required tobacco companies to

include a health warning on cigarette packets, stating that tobacco is

harmful to health. Hence it is not acceptable that religious scholars

should issue any ruling on smoking other than its complete

prohibition.

All five basic needs of human beings are adversely affected by

smoking. These five needs have been identified by religious scholars

as self, mind, offspring, faith and money. It is obligatory for every

human being to preserve these five needs and to take no risks with

them. A man’s faith is adversely affected when we see that some

smokers do not fast in Ramadan, when fasting is obligatory to all

Muslims. Such smokers feel that they cannot refrain from smoking

during the fasting day. Offspring are harmed by the tobacco

consumption of either one or both of their parents. The fetus is

subjected to definite harm when a pregnant woman smokes. Also, a

smoker harms other people in what is known as passive smoking

whereby a non-smoker inhales the smoke of other people s cigarettes

when he or she is in close proximity to them. With all this harm a

smoker causes to oneself and to others, it is not possible to return any

verdict on tobacco smoking other than complete prohibition. Indeed

all Muslim scholars should give a unanimous verdict of its

prohibition.

Some scholars have tied their verdict of smoking to the financial

ability of the smoker, prohibiting smoking to people who cannot

afford it and making it less than prohibited to those who are easily

41

40

able to buy

is incorrect, as it does not look at the problem

of smoking jn its^jofality. The long list of injuries tobacco smoking

presents to phygi^l and mental health must be considered when

giving a ver$p|<^

alongside its financial aspect. Moreover,

it is, not permi||M |fbr a rich person to squander money at will,

because money 1|1( rigs to God in the first place, and then to the

community.

Besides, every Muslim with sound judgement should refrain from

approaching this seriously harmful and foul habit. Tobacco smoking