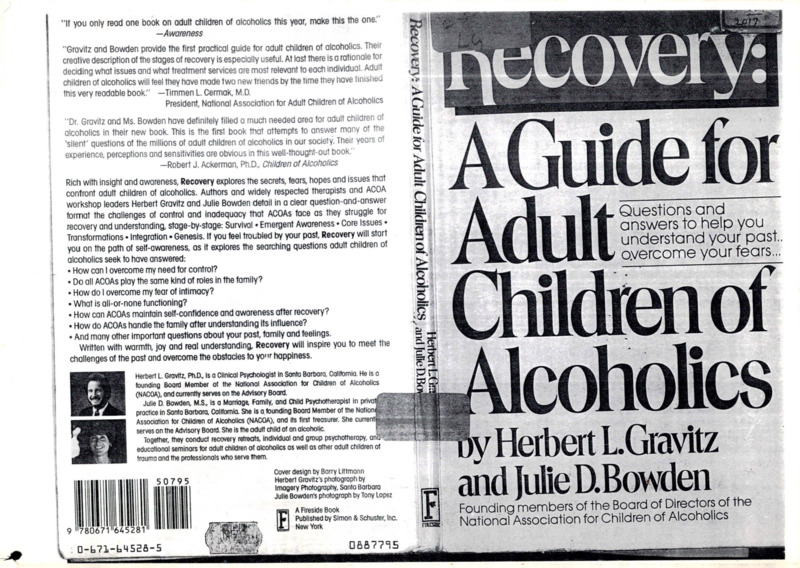

A Guide for Adult Children of Alcoholics

Item

- Title

- A Guide for Adult Children of Alcoholics

- extracted text

-

"If you only read one book on adult children of alcoholics this year, make this the one."

—A wareness

"Gravitz and Bowden provide the first practical guide for adult children of alcoholics. Their

creative description of the stages of recovery is especially useful. At last there is a rationale for

deciding what issues and what treatment services are most relevant to each individual. Adult

children of alcoholics will feel they have made two new friends by the time they nave finished

this very readable book." —Timmen L. Cermak, M.D.

President, National Association for Adult Children of Alcoholics

I

"Dr. Gravitz and Ms. Bowden have definitely filled a much needed area for adult children of

alcoholics in their new book. This is the first book that attempts to answer many of the

'silent' questions of the millions of adult children of alcoholics in our society. Their years of

experience, perceptions and sensitivities are obvious in this well-thought-out book."

—Robert J. Ackerman, Ph.D., Children of Alcoholics

i

1

i

Rich with insight and awareness. Recovery explores the secrets, fears, hopes and issues that

confront adult children of alcoholics. Authors and widely respected therapists and ACOA

workshop leaders Herbert Gravitz and Julie Bowden detail in a clear question-and-answer

format the challenges of control and inadequacy that ACOAs face as they struggle for

recovery and understanding, stage-by-stage: Survival • Emergent Awareness • Core Issues •

Transformations • Integration • Genesis. If you feel troubled by your past. Recovery will start

you on the path of self-awareness, as it explores the searching questions adult children of

alcoholics seek to have answered:

• How can 1 overcome my need for control?

• Do all ACOAs play the same kind of roles in the family?

• How do 1 overcome my fear of intimacy?

• What is all-or-none functioning?

• How can ACOAs maintain self-confidence and awareness after recovery?

• How do ACOAs handle the family after understanding its influence?

• And many other important questions about your past, family and feelings.

Written with warmth, joy and real understanding. Recovery will inspire you to meet the

challenges of the past and overcome the obstacles to yo' »r happiness.

n

ntcovery:

AGuide for

i;

t Chiklrenof

i

*22*

E

£

5‘

A

1Questions and

/> / jl 1IT answers to help you

AAI II III understand your past..

1 HI LX1L overcome your fears...

R-

lllw

!:I

■UH

! 9 ''ySOdyrdASZSI11 11,111111,11,1,1

□-h71-bM5E6-5

~TJk E

A Fireside Book

Published by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

New York

... I

•>

Herbert L. Gravitz, Ph.D, Is a Clinical Psychologist In Santa Barbara, California. He is a

founding Board Member ot the National Association tor Children of Alcoholics

(NACOA), and currently serves on the Advisory Board.

Julie D. Bowden, M.S., Is a Marriage, Family, and Child Psychotherapist in priva^^^^

practice In Santa Barbara, California. She is a founding Board Member ot the Nation^

.

Association for Children of Alcoholics (NAC0A), and Its first treasurer. She current^.^^d

serves on the Advisory Board. She Is the adult child of an alcoholic

P ’' J

alcoholic,

Together, they conduct recovery retreats. Individual and group psychotherapy, anB

educational oAminnre

seminars fnr

for nHiiit

adult rhiWron

children nf

at nimhnlins

alcoholics ns

as well

well ns

as other

other adult

adult children

children of

of

trauma and the professionals who serve them.

Cover design by Barry Littmann

Herbert Gravitz's photograph by

Imagery Photography, Santa Barbara

Julie Bowden's photograph by Tony Lopez

’■'-A'55-'

Mcoholics

y Herbert LGravitz

« and julie D.Bowden

rI

Founding members of the Board of Directors of the

National Association for Children of Alcoholics

r t-.. -■

r r•

; y yj

'•

i

RECOVERY

■

‘

L-J..

A

A Guide for Adult

Children of Alcoholics

.1

Herbert L. Gravitz, Ph.D.

Julie D. Bowden, M. S.

With a Foreword by Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse

J

'■7

A Fireside/Learning Publication Book

Published by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

New York

-fi

I

I

1

Copyright © 1985 by Herbert L. Gravitz

I

and Julie D. Bowden

All rights reserved

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

First Fireside Edition, 1987

Published by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Simon & Schuster Building

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Published by arrangement with

Learning Publications, Inc.

FIRESIDE and colophon are registered

trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States

Acknowledgments

Thanks to: Bill B., John M., Linda B., Jerry W., Pam D., Rick U.,

Suzanne E., and Sue Y.; our first psychotherapy group for “Adult Children

of Alcoholics” at the University of California at Santa Barbara in 1981;

The Santa Barbara City College Adult Education Program, particularly

Ellen Downing for faith in us and the opportunity to work with over 1,500

adult children who taught—and continued to teach—us countless lessons;

John Stoddard for encouragement and cheer; Luis Tovar for insightful

assistance on minority adult children; Raymond Wilcove for his proof

reading acumen; and Danna Downing for her enthusiastic, negotiable, and

humane approach to editing.

Especial thanks go to Linda Mears of Copy Desk for her heroic and

talented help. She unselfishly met every difficult deadline we asked. She

transcribed our initial tapes and typed on first draft. Without her, this book

would have stumbled and stalled.

We also thank our teachers and colleagues on the Board of Directors

of the National Association for Children of Alcoholics, who very early

expressed faith in our work. We have never seen a finer group of human

beings! Dr. Robert Ackerman was especially encouraging and supportive.

Finally, we thank the many others who gave of their time, their heart,

and their pain and who are not mentioned by name because of lack of

space—not gratitude.

of America

10 9 8 7

pbk.

Library of Congress Catalogmg-in-Pubhcation Data

Gravitz, Herbert L., date.

Recovery: a guide for adult children of alcoholics.

Rev. ed. of: Guide to recovery, cl985.

“A Fireside/Learning Publication book.”

Includes bibliographies and index.

1. Adult children of alcoholics—United States—

Miscellanea. 2. Alcoholics—United States—Family

relationships—Miscellanea. 3. Alcoholism—^Treatment

United States—Miscellanea. I. Bowden, Julie D.,

date. II. Gravitz, Herbert L., date.

Guide to recovery. III. Title.

87-8796

HV5I32.G73 1987

362.2'9286'0973

ISBN 0-671-64528-5 Pbk.

-J

(’

?■

«

380

a a

,''!nr AVION y’ Hh 71

?

1 JL

DOCUM

y

t

Special Acknowledgments

Herb: To Leslie, my wife and soul-mate, in recognition of our love and

commitment to each other. We have traveled so many winding and

difficult paths together. May each new turn bring us even closer. And may

our Journey allow our generations to embrace life with more joy.

And to my parents, Philip Benjamin Gravitz and Sophie Korin

Gravitz, with love, honor, and respect. Survivors of a different kind, may

you know and enjoy knowing how far through the generations your seeds

are spreading.

I

Julie: To my children, Dondra, Tony, and Danae, who continued to love

me through all the crazy years, and grew into three courageous, beautiful,

and precious individuals.

And to my mother and father who did their very best, and whose gifts

I am still discovering.

I

.-1

T

:r

This book is dedicated to all the

adult children of alcoholics who, in

sharing their lives with us, taught

us what we now offer back.

r

!

iJ

I

[

I

i

I

r:

Table of Contents

Foreword

Preface

Chapter 1 Introduction

*

Chapter 2 Roots

1. What is an adult child of an alcoholic?

2. What is an alcoholic?

3. Why is alcoholism called a family disease?

4. What is a home like when there is an active alcoholic

in the family?

5. What is a “normal” home like?

6. Does it make a difference how old I was when my

parents or parent became alcoholics or if they left

home when I was a child?

What

if both parents are alcoholic?

7.

8. How does all this apply to me if my parents were

addicted to drugs other than alcohol?

9. Do all adult children of alcoholics feel the same?....

10. Why do I feel so strange, confused and scared?

11. When did all this begin?

12. Where does this leave the children of alcoholics?....

i

iI

II

i

I

■

Chapter 3 Survival

13. Why are adult children of alcoholics called “survivors”?

14. I feel like I was never a kid. What happened to my childhood?

15. What happens when children are raised in a home where

it is forbidden to talk openly about what is happening

in the family?

16. What are the rules that implicitly or explicitly guide

an alcoholic family?

17. What impact does this family atmosphere and these rules

have upon the children?

18. How do children adjust to this very repressive environment?

19. I have played every one of these roles. Can a person

play more than one role?

......................................

7

8

8

9

10

12

12

12

13

14

14

15

17

18

19

21

21

22

26

20. I am very successful and seem to have a good life; yet,

I feel empty and unhappy. What is wrong with me?.. .

21. What needs to happen in the survival stage so that adult

children of alcoholics can begin their recovery from

the effects of parental alcoholism?

r

h

Chapter 4 Emergent Awareness

22. What is emergent awareness?

23. What happens as a result of an intervention?

24. What feelings follow coming out?

25. What are some of the pitfalls at this stage?

26. What is the best way to take care of myself at this stage?

27. What resources are needed?

28. How much can I count on other people to be helpful?. . .

29. How do I deal with my parents at this stage (whether

they are dead or alive, near or far)?

30. Is it necessary to deal with the past and dredge up all

that pain?

31. I don’t remember much from my childhood. Is that common?

32. Why is it important to acknowledge the alcoholism in

my family?

26

27

29

29

30

32

33

34

35

37

37

39

40

Chapter 5 Core Issues

i

L

33. What happens to children of alcoholics as they grow up?

34. In what ways do childhood roles and rules later work

against adult children of alcoholics?

35. What are the main problems of adult children of alcoholics?

36. What are the most common personal issues with which

adult children of alcoholics struggle?

37. What other personal issues might result?

38. In what situations are these issues most noticeable?

39. Why do I dread holidays?

40. What is the best way to take care of myself while I am

confronting core issues?

41. What are the pitfalls at this stage?

42. How do I deal with my parents in this stage?

43. These issues seem to apply to a lot of people. Are they

really unique to adult children of alcoholics?

44. What about the culturally different or the ethnic minority

59

adult child of an alcoholic?....

45. How will I ever be able to get rid of all these problems? 61

43

43

45

46

49

52

53

55

56

57

58

I

Chapter 6 Transformations

46. What is a transformation and how does the transforma63

tions stage fit into the recovery process?

47. How can I begin to work through what happened to me? 63

48. Why are issues of control and all-or-none functioning so

central to adult children of alcoholics?......................... 64

49. How can I begin to come to terms with my all-or-none

67

functioning?

68

with

the

control

issue?

50. How do I begin to come to terms

>

are

51. I do not fully trust anybody. I believe others

somehow going to hurt me. What does this mean? Is

70

something wrong with me?

............

71

How

can

I

begin

to

work

through

my

trust

issues

with

others.

52.

72

53. How do I begin to deal with my fear of intimacy?........

54. Dealing with feelings is still scary for me. What are

some guidelines in dealing with them, especially with

74

the new feelings?

55. Friends and family are telling me I am getting self

centered. Am I focusing too much on nry self and my past? 76

79

56. What about this notion of self-esteem?..........................

57. How important is it for my own recovery to confront

81

my parents at this stage?...........................................

58. How do I know that I am working things through or

82

that transformations are really occurring?

Chapter 7 Integration

59. What is integration?.

60. Why is integration so important for adult children of

alcoholics?............

61. I have been reading this book and feel frustrated and

confused because I do not seem to be feeling better.

Is there something wrong with me?

........

62. How can I maintain my progress and growth without

creating a crisis and without sabotaging myself?

myself? . . .

>

85

86

87

88

■W

4

63. What are the pitfalls in this stage?

89

64. What are some of the most important processes in the

integration stage?

..............

91

65. How can I continue the process of taking better care of myself? 92

66. What resources are needed?

.................. 94

67. How can I avoid being “selfish”?

95

68. What kind of relationships can I expect to have with others? 95

69. What are my rights as an adult child of an alcoholic?... 98

70. Is there a cure?

............................................ 100

71. Where do I go from here?

101

i

1

Chapter 8 Genesis

103

72. What is genesis?

73. What can I do to cultivate genesis-like experiences?... 104

104

74. Does genesis embrace religion?

75. Must I go through the stage of genesis? I feel like I am

just getting comfortable with everything I have been

learning

.........................................................

105

76. If I experience genesis, will I finally get to be perfect?.. 105

77. What other pitfalls might occur in genesis?

106

78. How do I deal with my parents in this stage?

106

79. What now?

107

Appendices

N

We are hearing more and more about adult children of alcoholics,

how widespread their identification is becoming, the serious emotional

and sometimes physical problems they face, and now how their issues can

be addressed. In the last few months, many books have become available

in addressing adult children of alcoholics. One of the best is this work

by Julie D. Bowden and Herbert L. Gravitz. Their book is written in a

clear, concise, easy to read question and answer format. As I travel around

the country, I am continually asked questions very similar to the ques

tions raised in this book. It will help me a great deal to be able to refer

to their book in order to bring answers, ideas, and new information to

the countless numbers of adult children who are so eager for clarity. Clarity

of what happened to them and understanding of how to self-help are two

very helpful themes that run through Herb and Julie’s work. On a per

sonal level, it is comforting and exciting for me to know that Herb and

Julie have facilitated countless sessions (personal and group) with adult

children and truly know what they are talking about. May you enjoy this

book as much as I have and may you enjoy sharing it with your clients

and friends.

—Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse

A Final Note From The Authors

A. Recommended Reading..

B. Where To Get More Help

Foreword

111

113

References

115

Index

119

Preface to the 1987 Edition

I

fI

►

■

■■

r

r

' j

1

J

It has been two and a half years since Guide to Recovery was first

published. Since that time much has happened. It has become clear

that we are in the midst of a healing energy, a spiritual force that is

finding its way into countless homes in our country. The children

of alcoholics, of all ages and numbering in the tens of millions, are

in the midst of a profound social movement.

NACoA, the National Association for Children of Alcoholics,

continues to flourish. Whereas it started in 1983 with little over

twenty members, NACoA is now over 7,000 strong and growing.

Each and every day, as newly formed state chapters emerge,

people are coming to join its special mission. And not only is there

NACoA, there is CACoA, the Canadian Association for Children

of Alcoholics. Things are indeed happening!

I

As we have traveled, presenting lectures and workshops on the

recovery process for children of alcoholics, we have come upon

i another simple but powerful truth. In towns and cities throughout

the country, people have come to us saying, “I read your book and

j it really helped me. But I’m not the child of an alcoholic.” More

and more people began to tell us that the book didn’t really begin to

match their experience until they read the chapter entitled “Core

Issues.” Then they would say, “You hit me right between the

eyes!”

So we continued to learn and we began to see what many of our

colleagues were discovering as well: children of alcoholics are but

the visible tip of a much larger social iceberg which casts an

invisible shadow over as much as 96 per cent of the population in

this country. These are the other “children of trauma.” Surviving

their childhoods rather than experiencing them, these children of

trauma have also had to surrender a part of themselves very early

in life. Not knowing what hit them, and suffering a sourceless sense

of pain in adulthood, they perpetuate the denial and minimization

which encase them in dysfunctional roles, rules, and behaviors.

These are the hidden depths of the iceberg, these children of

trauma. Over 200 million of us are denying our past, submerging

our realities, and ultimately misplacing both our “little” self and

our “big” Self. This is quite a legacy to inherit from our parents,

and we pass it on to our children.

I!

>1

J

V

Hiit

I

M' ir1 .

I'

f li

ll1

ill

!|!

!i

I

Who are we? Who are children of trauma? We are children

raised in other kinds of troubled family systems. We may have

grown up under the influence of such compulsive behaviors as

over- and undereating, gambling, spending, working, or “loving” j

too much. We may have experienced life through the horrors of

traumatic stress, as have genocide survivors, be they Jewish

ative American, African, or other. We may have had a schizo

phrenic or manic-depressive parent or a parent with chronic mental

or physical illness whose denial and misinformation fueled a fire of

guilt and blame. Most have come from perfectionist, judgmental

critical, or other non-loving families who appeared normal or welltunctionmg on the surface.

In all of these families rigidity prevents normal childhood

development. In the name of love, children are ignored, isolated

abandoned, and abused. Visible as never before, child abuse is

marring untold millions. The number of abused children is stag

gering. Who would believe it? Perhaps 230 million children of all

ages m our country! All are children of trauma, the children of our

time.

These survivors of childhood are learning to recover. And we

have come to believe that the very same process that offers

recovery to children of alcoholics produces recovery for children

of trauma. Like children of alcoholics, children of trauma reach

adulthood feeling sick, bad, crazy, or dumb—feeling inherently

flawed. Not all children of trauma make it through to adulthood so

recovery begins with the survival of childhood for them, too. Until

recently survival was the only stage of recovery. That is changing,

s one of our clients stated, to find out about the trauma is to find a

way out. So, we are discovering that emergent awareness for

children of trauma is as powerful and liberating as for children of

alcoholics, and their core issues are strikingly similar. A transforma ion can occur which leads them to a life-enhancing integration

o t eir past and ultimately leads them back to a new beginning a

genesis.

6’

Without abandoning our commitment to the more than 30

children of alcoholics, we would like to open our hearts to

hurtr Ch^en Of trauma’ and acknowledge that they too have been

hurt, and they too have a road map to recovery.

We have been blessed by so many along the way who have 1

given us support, guidance, new learnings, and love. We hope that

this 1987 publication of Recovery by Simon & Schuster will allow

children of alcoholics and other children of trauma to acknowledge

their own history, and provide relief and initiate recovery.

So if you are all grown up on the outside, but feel little and bad

on the inside, then this book may be of help to you. You might want

to take a moment now and thank the child you once were for

helping you survive the trauma, bringing you to this time and this

place. Welcome. We wish you well on the journey. This time it’s

your time to recover.

—Herbert L. Gravitz

Julie D. Bowden

1

Introduction

I

I.

I

j.

I

Leslie was mesmerized. The muscles around her eyes tightened as the

shock of recognition crossed herface. The stories she was hearing sound

ed just like hers! The other people in this group, who looked so picture

perfect, had experienced the same abandonment, the same loss of childhood,

the same sense of betrayal that she had felt in a home dominated by an

alcoholic parent.

Ann, who had recently celebrated her eighty-first birthday, relaxed

as she heard others describe the embarrassment of their childhoods—the

humiliations, the insults, the times they were afraid to come home, and

those terrible holiday scenes. As the shrouds ofsilence slowly disappeared,

she was no longerfeeling isolated and alone. There were no secrets here.

These were her stories too.

Brian was trembling. He was thinking of his parents. Pangs of guilt

pierced his stomach. For the first time he actually talked about what went

on in his family. He dared say out loud to others that his parents were

alcoholic. He fidgeted as he forced himself not to pretend anymore. But

it was hard! Scary! Yet, somewhere at the edge of his awareness, there

was a feeling, a real feeling, that he did not want to deny.

Eric felt detached, as if he were a million miles away. He did not

like to think about what had happened. He wanted to forget. What was

the use anyway? Nothing changes; nothing really makes a difference. If

only he could get rid of those recurring nightmares. He barely remembers

them in the morning. He just knows they come.

The Leslies, Anns, Brians, Erics, and the millions of others like them,

are adult children of alcoholics. Reared in a home in which one or both

parents are alcoholic, they are united by the bondage of parental alcoholism.

Most adult children of alcoholics have always suspected that something

is wrong. They often experience loneliness and they are likely to believe

that they are different from other people. They are! Without fully

r

r

2

l

I

I

I

INTRODUCTION

RECOVERY

3

■

identifying the source of their emptiness, they have endured and suffered.

They have survived the experience of living in a family where unpredic

tability was the one thing that could be counted on. They seldom knew

what to expect from parents—a frown or a smile, a slap or a kiss. They

have survived the experience of living in a family where inconsistency

was the rule. No two days were the same and they could not believe in

what others said. Subjected to denial, broken promises, and lies, they were

often at the mercy of parents whose feelings, perceptions and judgments

were clouded by a mind-altering drug—alcohol. They have survived the

experience of living in a family where everything was arbitrary—things

were always happening by whim or impulse in ways that seemed out of

control. And because their families were like this, they have survived liv

ing with a family in chaos. Almost every day there were crises and emergen

cies at home. It was never really safe to relax—or be a child; Since their

families represented their worlds, they lived in a world of unpredictability,

inconsistency, arbitrariness, and chaos. These are the children of alcoholics.

This book is for these survivors, the children who grew up in an

alcoholic family and became adultsTlt describes the costs they have had

to pay to survive. More important, it presents a way they can re-evaluate

their survival techniques in light of the problems they now face as adults.

This book will help adult children of alcoholics to use these techniques

as resources to propel themselves forward to a life of meaning and joy.

As one adult child of an alcoholic said, “If I can use the debris of outrageous

misfortune and turn it into something positive, then none of what happened

to me occurred without rhyme or reason.”

This book reflects recent changes in the field of alcoholism and growing

efforts to identify and assist adult children of alcoholics. New and exciting

things are happening. It was not until 1955 that alcoholism was recog

nized as a disease by the American Medical Association.40 In the 1960s

and 1970s it slowly became increasingly clear to professionals that the

family develops a parallel disease of its own.633-50-53 And in the late 1970s

and early 1980s, explicit acknowledgment has been given to the adult sur

vivors. 8-14 3058 Then, on Valentine’s Day of 1983, the National Associa

tion for Children of Alcoholics was formed to recognize the needs and

problems of children of alcoholics of all ages.44 Yes, things are

happening!

This book is a part of what is happening. It is about a neglected minority

numbering in the millions. Recent estimates indicate there are between

28 and 34 million children of alcoholics, over half of them adults.7’31

1

Because their survival behaviors tend to be approval-seeking and socially

acceptable, the problems of most children (and adult children) of alcoholics

remain invisible.44 It is not that they are not being treated. They are-in

mental health agencies, psychotherapists’ offices, hospitals, employee

assistance programs, and the judicial system.44 But the importance of

their parents’ alcoholism often does not receive the focus and attention

it merits. Despite the increasing recognition of alcoholism as a family

disease, children of alcoholics continue to be ignored, misdiagnosed, and

inappropriately treated. Many limp into adulthood behind a facade of

strength. They survive adulthood, too, but do not enjoy it.

This is a book about how children of alcoholics of all ages can begin

to enjoy their adult lives. We want to share what we have been learning

from the adult children of alcoholics we have encountered as therapists

and educators. Most of all we want to share our enthusiasm and excite

ment as well as convey a message of hope and understanding. We have

seen dramatic, positive changes in adult children of alcoholics once they

understand how their earlier experience with familial alcoholism continues

to influence them.

We invite you to join us on a journey in which we are all pioneers.

The journey will help you to uncover the influence of family alcoholism.

The approach we will use is a question and answer format. The questions

addressed are those we have been asked most frequently by adult children

of alcoholics. As we have journeyed with others, we have come to ap

preciate that there will be a number of responses to what is discovered.

Some people are surprised, shocked, or overwhelmed by the answers. Some

become angry and frustrated. Others remain skeptical and want to know

where the “research” is. Some become very sad and cry, while others

feel relief, elation, and hope. Few remain unaffected. There are reasons

for the strong emotional responses provoked by the questions and answers

presented in this book.

First and foremost, we will be talking about all those things that

children of alcoholics of all ages are taught not to talk about. One of the

cardinal rules in an alcoholic home is, “There’s nothing wrong here and

don’t you dare tell anybody!”8'53 So we are most reverently breaking the

shroud of silence that encases the alcoholic family. We dare to discuss

things as they are, not as they should be or as you might like them to be.

We know alcoholism is one of the most prevalent diseases, one in ree

families are affected.26 The alcoholic family is “the family next door.

Alcoholism is also a complex and puzzling disease; we still do not know

Ih

I

I1

I

4

RECOVERY

INTRODUCTION

H

0

exactly what ca

it?2 We kn{w * js a devastating disease It

the hody mmd, and spirit.3’ It affects the individual, family, and

‘ *S generatl0nal' And because it is generational it affects the

future

There are almost 15 million Americans suffering from

alcobohsm or problem drinking. Their numbers are increasing by almost

a.mi,

PeoPIe each year. Over 75 million Americans are affected

and alcoholism costs this country over $120 billion a year.55 Every two

and one-half minutes there is an alcohol related death.15

Second, adult children of alcoholics are profoundly affected when they

overcome the barrier of denial because this requires them to confront the

consequences of this ravaging disease in a very personal way. Children

of alcoholics are at maximum risk of becoming alcoholic themselves or

developing other addictive behavior. They are at the risk of marrying an

a cohohe one or several times. And they are at the risk of developing

predictable problematic patterns of behavior in which they get stuck over

an over again. 8J’-6 Yet most do not even understand what hit them

lhere is no such thing as growing up unaffected when alcoholism is pre

sent in a family, but it is difficult for the individual to acknowledge these

problems. Arrested emotional development is inescapable unless the effec s of this disease are dealt with. Alcohol is an equal opportunity

destroyer. Whoever gets in its path is affected.

Third, a multitude of powerful feelings is provoked when the individual

begins to come to terms with the past. Over and over we have seen adult

ch' dren experience spontaneous age regression. This means that as adult

children break the demal and silence, they find themselves thrown back

eh Mb Paf cPartiCU?ur WOrds’ music’ or places trigger memories from

childhood^ Some of these experiences have not been remembered or felt

in years Some are pleasant; many are not. All are real. Remembering

and exploring the effects of growing up with alcoholism in the family it

Part,°f a, lar.8er process of learning, growth, and development. In other

words, this is a journey of change. And change is always scary. No mat

ter how miserable you are, at least your life is predictable as it is. Adult

children of alcoholics often confuse stability with consistency and rigidly

cling to what is familiar even though it is destructive.

discu^UThChlldreniOf alcoholics already know much of what we shall

know ed

Y JUSt d° n0‘ kn°W that they know! Our task « to make this

Lch

aCCeSSlble’ meanlngft11’ and USefu1' We believe ‘bat in

more resoA t‘S

W,Sd°m

Strength' The human mind has

resources than it can possibly use. It is a vast territoiy of undiscovered

5

I

I

potential. We believe people make the best choices they can with the in

formation they have and that with new information they will make better

choices. While this means our parents made the best choices they could,

it does not mean that they did not make terrible mistakes at times. We

believe that people grow best in an atmosphere of freedom and choice;

that people with the most choices are usually the healthiest and happiest.

Sometimes adult children of alcoholics are so eager to change that they

will reject valuable parts of themselves. Yet there is a positive aspect to

almost every part of us if we can just find the right context for its expression.

In reading this book, you may find that your experiences do not match

everything that is described. Use this material as a place to begin. Take

what is helpful and leave the rest. We could not possibly cover everything

and we have probably left out some questions that are important to you.

Begin to trust the validity of your own experiences, knowing you will make

sense out of our words and find your own meaning. It is up to you to decide

what kind of changes you want to make, if any, and how this book can

best serve your needs. You can decide, for instance, how much of this

book to read, when to read it, and with whom to share it. Sometimes the

best way to move quickly is to go slowly! Honor your own pace and speed.

It has been our experience that the book works best when read in sequence.

However, maximum benefit will come if you also feel free to put the book

down at times. Taking a walk, talking to a friend, developing a support

system, or going to Al-Anon can help you get through difficult sections.

Reading the book when you are under the influence of alcohol or other

drugs will not be helpful.

Finally, this book provides a way to share the questions and experiences

of adult children of alcoholics. Together, we will explore the inner work

ings of an alcoholic family. We will discover what roles the children adopt

and how these bear on their adult lives. We will look at the personal and

interpersonal difficulties in which adult children frequently become

enmeshed. We will also talk about what can be done to overcome these

difficulties and describe the recovery process. We will show that traumatic

incidents in childhood can lead to abilities and personal strengths that the

individual can draw upon during the recovery process. We will see how

strength can be restored from wounding. We shall discover new paths to

freedom.

So we welcome you on what we anticipate will be a most important

journey—your journey, your recovery. It is time!

t '■

ii

I

bi

I

§1

''

I

■

2

rr

d1

Roots

1. What is an adult child of an alcoholic?

1

II

I

I

I

The phrase “adult children of alcoholics” was used by a few

alcoholism professionals in the 1970s when research and clinical obser

vation began to demonstrate that children growing up m families where

there is alcoholism are particularly vulnerable.91859 They are susceptible

to certain emotional, physical, and spiritual problems.8,9-48 55 The Na

tional Association for Children of Alcoholics considers adult children of

alcoholics as having an adjustment reaction to familial alcoholism which

is recognizable, diagnosable, and treatable.44 Based on our work, we

consider an adult child of an alcoholic to be anyone who comes from a

family (either the family of origin or the family of adoption) where alcohol

abuse was a primary and central issue. We have found that almost everyone

who has an alcoholic parent has been and is profoundly affected by the

experience.

Mental health professionals have encountered adult children of

alcoholics by the millions, but have not accurately diagnosed the roots

of their complaints. Children of alcoholics appear for treatment for a host

of reasons other than for being children of alcoholics. For example, they

are treated for alcoholism, co-alcoholism, eating disorders, learning

disabilities, depression, and severe stress. Until recently, explicit

acknowledgment has not been given to their plight as children of alcoholics.

It is time to identify them more meaningfully. It is time to call them adult

children of alcoholics. To do so is an important step in uncovering the

nature of their difficulties and providing effective interventions. It initiates

recovery!

Some people are not sure whether their parents are or were suffering

from alcoholism. We have found that if the question is there, then it is

likely the problem is there. It is very similar to asking, Am I an

alcoholic?” If I am asking that question, chances are I am an alcoholic.

J

i

t

II

I

8

RECOVERY

ROOTS

2. What is an alcoholic?

As the alcoholic becomes sicker and sicker, there is a parallel breakdown

in his or her family. As the alcoholic loses more and more control, others

in the family adapt by assuming increasing amounts of responsibility. Some

one begins to do those things the alcoholic is not doing. Someone makes

excuses to friends and family. In this way, alcohol reaches beyond its

chemical effects on the individual abuser and becomes a family affair. The

family’s demoralization is as devastating as the alcoholism itself.

Initially, the family is not aware of what is happening. Like the

alcoholic, family members do not want to face the reality of their situa

tion. Their denial becomes a hallmark in the same way that denial is a

hallmark of alcoholism. It seemingly protects them from the terror of

acknowledging that their lives are out of control. The family is no longer

a safe place in which to communicate, to grow, or to love. Implicit rules

guide the family along a path of sickness and, at times, destruction. Family

members easily begin to develop unhealthy ways of coping with family life.

t

IM

!

9

Alcoholism is a devastating, potentially fatal disease The „ •

1

J

■■is

4. What is a home like when there is an active alcoholic in the family?

No <one

— sets out to lose control and thereby become an alcoholic

Alcoholism develops subtly and i;

becomes pro.resd^b;;,™'/

“sidmusly. If untreated, alcoholism

progressively worse.

Alcoholics

not hdrink n°t because they are depressed, not because they

are scared, inot because they are sad, not because they are happy. They

drink because the*y no longer have a choice. They have lost control 5™-52

3. Why is alcoholism called

a family disease?

fami^therapy6 Ast"?

in the

!a

of alcoholism and

Jis

observed that the spoustJ of the al""b r '‘C0-dePende^ ''“'5’It was

process.22-57 In the 1970s and 1980 th ° 1C *S drawn lnto the disease

fessionals that other familv

k

lncreasing1y clear to pro

alcoholic.

y members’ t00> are seriously affected by the

I

i

In a home where one or both parents are actively alcoholic, family

life has a distinctive character. Family life is inconsistent, unpredictable,

arbitrary, and chaotic'0™ These four words typify life in an alcoholic

family. For example, what is true one day may not be true the next day.

A child may have a conversation with a drunken parent one night, but

when the child refers to it later, the parent may have absolutely no recollec

tion of that conversation. In an alcoholic “blackout” a person experiences

a type of chemical amnesia and cannot remember what was said or done.

The child does not understand what has happened. Even alcoholic parents

may not realize they have experienced a blackout. That is one reason life

is so inconsistent and unpredictable. Another is that personalities change

with alcoholism. For example, if I am the child of an alcoholic, my mother

might be the most loving, wonderful woman when she is sober, but just

the opposite when she is drinking. I cannot be sure which person I am

going to meet when I come home. Children of alcoholics learn specific

lessons from this. They learn to repress spontaneity, to first check things

out to see if their parents are sober, and how to shrug off disappointment.

There is a whole set of behaviors and attitudes a child develops and car

ries into adult life as a result of such lessons.

i

I

10

ROOTS

RECOVERY

The arbitrariness stems from the whimsical and impulsive changes

that occur from one day to the next; and, of course, children are unable

to determine the basis for these changes. They cannot understand that the

arbitrariness stems from the alcohol abuse. For example, very often parents

are unable to agree on rules for their children. If I am a child of an alcoholic,

it might be that this week my parents have decided that I am old enough

to go out and stay out as late as I want. Next week, for no apparent reason,

I am not allowed out of the house. Or, my father might have a rule that

says I cannot date until I am 18. My mother decides that this is loo harsh.

She believes I should have much more freedom. So I have two conflicting

rules.

children about how they view rules. Rules tend to be realistic, humane,

and not impossible to follow.

The rules take into account the unique feelings, beliefs, and differences

of family members. When feelings are expressed, they are listened to and

accepted. Children are heard and treated with respect in a functional family.

There are rules that state: “Don’t be violent; don’t be abusive, cruel, or

mean Tell us what is wrong so we can help.” It is also permissible to

be separate, have your own things, and your own identity. Boundaries

between each individual are accepted, encouraged, and respected. Com

munications tend to be open instead of closed. When communications are

open one can talk to others ■’bout what they think is happening. For ex

ample, if my mom falls off her chair at the dinner table, I can say, Hey

mom fell off her chair . . . What’s happening? . . I m scared

Wha

can we do?” In a closed, alcoholic system the rules say, Don t talk. Don

So much in the alcoholic home is arbitrary, unpredictable and incon

sistent because everything is based on a drug which impairs functioning.

Chaos is the natural result. Include in this picture the certain emotional

abuse, as well as the potential for physical or sexual abuse and you can

see that life in an alcoholic home is like living with an accident every day.

Ij

i

trust. Don’t feel.”8

In a functional family children depend on adults. Children trust that

they will be cared for. They are allowed to be children and they know

it will be that way tomorrow, too. In a functional home children are: laugh

how to cope and how to assume responsibility. New roles are not th

upon them in one drunken weekend, but are conveyed over years of nur

turing They will not suddenly be expected to take on parental tasks fo

which they are not prepared when a parent vanishes into a bottle or d1Sap-

5. What is a “normal” home like?

This question is often asked by adult children of alcoholics. There

is no such thing as a “normal” home. Unfortunately, children of alcoholics

often believe that somewhere, somehow, there exists a perfect family. This

notion of the perfect family is the standard against which they judge their

own family life. They have unreasonable expectations with which they

compare themselves unmercifully. It appears to them that everyone else

is happy and well adjusted while they are different and damaged.

Let us say that a “normal” family is simply one without alcoholism

or where members can talk openly about their experiences. However, in

stead of looking at things in terms of normal or abnormal, it is more useful

to think in terms of functional and dysfunctional. Functional homes pro

mote children s sense of well-being; they are relatively consistent, somewhat

predictable, minimally arbitrary, and only occasionally chaotic. In terms

of family roles, there is appropriate delegation of authority. Youngsters

are not expected to drive cars, or do the grocery shopping, or run the

household. Children are not given the responsibilities of parenting. The

parents are not children and the children are not the parents.

Rules are more explicit in functional families.53 They do not change

from day to day or from hour to hour, so children usually know what is

i

11

pears to a bar.

Children do not live in fear in a functional family. In too many alcoholic

homes, children live in fear because of the abuse to which they are su jected. Common fears are that they will be hurt or abandoned, that they

are unlovable, and that things are out of control. This is a result of t

parents not being emotionally and physically available. In a functional fam

ly children know there is someone more resourceful than themselves

a functional family children know they will not be abandoned regard e

of what they do. In an alcoholic home the child feels abandoned again

and again. As one adult child of an alcoholic said, “When I was a little

child, my parents abandoned me, and they never le t t e ous .

Still functional families are human; they are not perfect. That is im

portant to know. In a functional family there may be yelling and

screaming—but not typically. There may be anx.ety and tension

4

1

12

ROOTS

RECOVERY

13

i

on a daily basis. There may be unhappiness—but not usually. And there

may be anger and hurt—but it is not chronic.

6. Does it make a difference how old I was when my parent(s)

became alcoholic or if they left home when I was a child?

!

What seems to be true is that the negative effects of having lived in

an alcoholic family are greater the younger the child is as the disease pro

gresses and the longer he or she lives with an alcoholic parent.

So

yes, we believe it does make a difference how old the child is. And if

the alcoholic parent leaves home, there will be some difference in effects,

but the child must deal with literal abandonment issues and is then often

raised by a co-alcoholic who is sick also. It has been said that the only

difference between the alcoholic and the co-alcoholic is that one does not

drink?3 In other respects, this parent engages in many of the same

behaviors that undermine the child’s sense of safety and well-being.

7. What if both parents are alcoholic?

Research suggests that if you have two alcoholic parents, you are go

ing to be younger the first time you get drunk, you are going to have more

behavioral problems before you get into a treatment program, and the period

between the first intoxication and treatment is going to be much shorter.

You will also tend to develop alcoholism much more rapidly?’ Common

sense would also suggest that with both parents alcoholic, the child has

even fewer resources available than if one parent was sober. It is getting

both barrels of the shotgun, so to speak. Neither parent is available in

any consistent, meaningful, protective way. So, children who have two

alcoholic parents have an even more difficult time and are even more

susceptible and more vulnerable to all the problems affecting children of

alcoholics. Recent research supports the idea that children with two

alcoholic parents have a greater genetic sensitivity to alcohol and, if alcohol

abuse occurs, to develop alcoholism more rapidly.34

8. How does all this apply to me if my parents were addicted to

drugs other than alcohol?

Much of it applies, depending on what other drugs we are talking about.

Alcohol happens to be the number one drug of choice in many cultures;

it is legal, very acceptable, and easily accessible. Children reared by parents

who are addicted to illegal drugs have all of the problems and concerns

of children reared in homes where alcohol is abused. They also have one

additional problem-the illegality of the substence abused and the

corresponding need for duplicity, breaking the law, and concealing infor

mation. In addition there is the fact that parents who deal with illegal drugs

are also more prone to deal with unsavory people and to be in violent situa

tions For instance, if we are talking about a drug like cocaine, people

can become so financially indebted to their dealer that physical threats

or actual physical violence may occur.

Prescription drugs can be very similar to alcohol in that they are quite

acceptable. Again, we have a very insidious drug about which some physi

cians may say, “It’s all right to take this, Mrs. Jason. Go ahead and refill

it whenever you need to.” Only when the patient or the addict begins ly

ing to get more prescriptions or when the mood swings are extreme is

it no longer acceptable. Often the family does not know what it is dealing

with because nobody sees the drug being used. Valium and similar drugs

are also less toxic to the human body than alcohol; the user may therefore

appear outwardly more healthy than an alcoholic?6 Yet, if you have a

mother who is up and down on Valium and “speed” under a doctor’s

orders, you may have some crazy situations that are just as unpredictable,

just as inconsistent, just as arbitrary, and just as chaotic as those with an

i

1

I

alcoholic parent.

$

9. Do all adult children of alcoholics feel the same?

ll

Although children of alcoholics each have a different perspective and

see the environment, their parents, and their situation from their own van

tage point, we consistently find that they identify with certain general ex

periences. Often after we have described the “typical childhood of an

adult child of an alcoholic in a class, someone will approach us and say,

“Everything you said sounded like you were talking about me.” Most

develop similar feelings and fears. It is a relief for many to discover that

they are not alone.

Nevertheless, not all children of alcoholics experience identical emo

tional and physical effects. A number of variables account for this beyond

the fact that each and every child is unique. Again, one factor is the child s

J

Ill

14

RECOVERY

ROOTS

Hi i

fl

Ii

I

II

p

I

famik° bHh0' d6 fad!er,wh0 ,s alcoh°lic; *6 number of children in the

family, birth order; whether the spouse is working on his or her recoverywhether or not there are other, helpful influences available, such as famiabuse^Jther ‘J*0

Whether °r nOt there is Physical or sexual

mav

^iTaJ tOrS SUCh aS the family’s so^oeconomic status

may affect the child of an alcoholic.1

Even in the same family not all children will react the same way For

example one child may clearly see the alcoholism, while another may

the sMn?/ “ 3 P

f3Ct’ he °r ShC might get £Juite “Pset with

±e sibling for even insinuating that alcohol is a problem in their family

ano?h adult.|hlldren of alcoholics have told us that when they spoke to

another family member about alcoholism in the home, the other reacted

with disbehef, saying, ‘‘What alcoholism? Who was an alcoholic? Dad

from ■ r alCOhO!,c! Sometimes they encounter very hostile responses

ch Id inleT a-l 3 8Leat

°f anger f°r “maligning” a parent One

child n the family might remember a series of horrors in childhood, while

wonderT “Whvd mig* ch°Ose t0 remember only the good times and

in a farnilv mt F\UP

Ug'y thingS?” While

10. Why do I feel so strange, confused, and scared?

to catsl aacVhildefenfdefCribin8 3

atmosPhere that is almost certain

to cause a child to feel inadequate, tense, and upset. It seems impossible

to grow up in this kind of environment without feelings of confusion guilt

anger, shame, or fear. These are “normal” responses to an “abnomal”’

situation. It is no wonder that you feel strange, confused, and scared' If

UiereTastt U ‘

°f a" alcohoIic’ y°u 2rew UP in a family where

fomfly pai J3111^ SeaSC’ 3

SeCret’ and Shared but unacknowledged

11. When did all this begin?

15

often children of alcoholics and still traumatized when they become parents.

If parents consume enough alcohol, it can affect the unborn child.17 The

chances of being affected by fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) are high for

children whose mothers drink heavily during pregnancy. The genetic,

biochemical, and neurophysiological mechanisms involved in alcoholism

may begin to affect the child at the moment of conception.I9-40-48-52 This

is in addition to the environmental impact we have been describing. Since

heredity and environment have an impact on the development of the child,

the effects of parental alcoholism begin very early in the child’s life, long

before he or she is aware that there is a problem.

12. Where does this leave the children of alcholics?

Children of alcholics have acquired biological and psychological

vulnerabilities that follow them into adulthood and which, if not addressed,

can become a permanent disability.918-20-59 It is as though the child has

been wounded and was never properly treated. Like an injury not allowed

to heal properly, it carries over into adulthood as a chronic health problem.

Yet, what we have found particularly exciting and what makes us op

timistic is that children of alcoholics have learned to cope with a variety

of truly difficult, sometimes life-threatening situations. In the face of stress

and trauma they have learned to survive. This same strength can be drawn

upon to recover from the negative effects of parental alcoholism.

■

3

;i

Survival

13. Why are adult children of alcoholics called “survivors ?

This term acknowledges that adult children of alcoholics made it

through childhood, and stayed alive in what could be described as a war

zone Like shell-shocked war veterans, there were many times throughou

their childhoods when their lives were threatened-emotionally and

spiritually as well as physically. Some were sexually violated. Children

of alcoholics do an amazing job of dodging, negotiating, hi ing, earn

ing, and adapting just to stay alive. They learn to be survivors despite

the demand that they pretend there is nothing wrong. They have had to

shut down their own emotional life many times. They learned to deny i ,

block it out, repress it, isolate it, dissociate from it. Otherwise, their feel

ings could have overwhelmed them. Terribly traumatic things happen to

children of alcoholics. And it is a testament to their skill and courage that

I

I

they arrive at adulthood.

Children of alcoholics had to survive essentially alone, because that

is the nature of the disease of alcoholism. It is an isolating, separating,

and lonely disease. Most of these children had to suffer in silence. They

thought nobody would believe what they said even if they would dare say

it. Who could believe it? In fact, they probably had the experience of be

ing told in no uncertain terms not to speak about what was happening^

In the classroom it may have been clear to them that talking about such

issues with the teacher was not acceptable. They may have known relatives

who watched what was happening and did not speak up. There was a secret

a shroud of silence everywhere.'3 Nobody would speak. No one would

acknowledge the obvious. One woman we worked with spent a great dea

of time deahng with her anger-and later all the hurt-at the adult relatives

around her who saw that her parents were alcoholic, that she was b: g

abused, that she was very troubled, and still did not reach out to help her.

They said nothing. She felt betrayed.

I

1

!

18

SURVIVAL

RECOVERY

consistent or predictable way. The boy loved him very much and did not

want to be a burden. Since he often could not be sure whether his father

was drunk, he devised a test. When his father came home, he would

challenge him to a game of basketball. If his father lost, the son knew

he had been drinking and there would be a long night ahead. If his father

won, then he was sober and the evening would be safe.

We know another child who would be invited to play at a neighbor’s

house, yet never felt free to say, “Sure, I can do that. I don’t have to

do anything until dinner.’’ Rather, the child was very aware of a need

to go home at the end of the school day to check on everything that was

happening. The child needed to know who was sober, who was there and

whether or not she would be needed to care for the other children or start

preparing the family dinner.

All of these children had their childhood usurped by premature

adulthood. Typically, there is a reversal of parent and child roles. This

means that the children really never had a chance to play and have fun,

never really had a chance to be free of the shackles of all that respon

sibility, guilt, worry, and caretaking. Many children of alcoholics, by the

time they reach their late adolescent and early adult years, are already

burned out—weary from being an adult for the first 20 years of their life.

So adult children of alcoholics are called survivors because they have

been through a war—and made it. If they are alive and reading this book,

we know they made it through. We know that they can, have, and will

survive.

14. I feel like I was never a kid. What happened to my childhood?

I

I

i

This is an experience that children of alcoholics very often report.

They are right when they say, “I was never a kid.’* They really did not

experience the freedom and the carefree years of childhood. They were

too busy surviving, placating, picking up the pieces, adjusting, and being

responsible. In other words, they were too busy being everything but a

child.

In an alcoholic family, as the alcoholism progresses and co-alcoholism

develops, there really is very little time left for the children to be children.

They are not treated as children, and may even come to have difficulty

seeing themselves as children. Children need a certain availability and a

certain responsiveness from parents who are not often present in an alcoholic

family.8 Many times the children are instead required to be available and

responsive to the parents’ needs. Children are vulnerable and rely upon

their parents to take care of them, to protect them. However, in an alcoholic

family it is not safe for children to be children. Often there is no one there

to take care of them. To cope with the situation and hide the fear of hav

ing no one to turn to, children of alcoholics learn to build a facade of

strength and competence. They learn to act like an adult while they are

still children.

An eight-year-old girl we worked with described how frightened she

became when she heard a fight starting between her parents after she had

gone to sleep. As the shouting increased and other sounds mounted (glass

breaking, slapping), she made her little sister moveto her bed. Over the

smaller child’s weeping, she reassured her, “It’s all right. Daddy won’t

hurt Mommy, and they’ll make up. Everything will be fine, just you wait

and see.’’ She set aside her own terror to parent her sister. The following

day she continued this pseudo-adult role by taking care of her mother and

offering to help with household chores, while reassuring her that everything

would be fine.

Another child lived in a home where the alcoholism was less obvious.

His father, while not a stumbling drunk, was not available in any

19

i

15. What happens when children are raised in a home where it is for

bidden to talk openly about what is happening in the family?

First and foremost, children are taught to disown what their eyes see

and what their ears hear. Because of denial in the family, children’s percep

tions of what is happening become progressively and systematically negated.

Overtly or covertly, explicitly or implicitly, they are told not to believe

what their own senses tell them. As a result, the children learn to distrust

their own experience. At the same time, they are taught not to trust other

people. How can it be otherwise when they are actually observing one

thing while the significant adults around them are telling them another.

For example, a boy may see his alcoholic mother fall off her chair at the

dinner table and not get up. His stomach muscles tighten, he gasps for

breath, and starts reaching for her because he senses she needs help. His

father, with a glaring look from across the table, insists that there is nothing

wrong. His look says nothing happened and not to move. “Mother is fine,

he states. “Leave her alone, ignore her, and go on eating. So the child

20

RECOVERY

sits carefully at the table with tears beginning to run down his cheeks as

his mother struggles to get up. He tells himself to be quiet, to pretend

nothing unusual is happening, and he tells his throat, tight from the tears,

to swallow that next bite of food.

This child is being taught many lessons. He is learning that his judg

ment is poor and incorrect. “Nothing is wrong,’’ he is told, but everything

seems wrong. “I must be misperceiving. I must be wrong,’’ he starts think

ing, “because how could my father deny my mother help if she really

needs it?’’ The child learns to tolerate many intolerable situations. After

all, the child concludes, “I am not seeing it right. I do not understand

what is happening. Maybe I should just accept the situation. The child

learns that his natural responses are somehow unacceptable, wrong, not

to be trusted. The child also learns that at least one of these adults is lying

to him or telling him something that goes totally against everything he

is sensing, everything that his experience tells him is real. Ultimately, the

child is taught not to trust himself or others. The results are disastrous.11

When people learn at an early age not to trust experience and not to

trust body signals, they begin to ignore feelings. When the boy in our ex

ample sat at the table and his mom fell to the floor in the middle of a meal,

and he was told to sit there and eat, he learned still another lesson. He

learned to set aside a whole set of important feelings and continue on

through mealtime, or through another experience, or through life, just as

if nothing had happened. To do that, he had to separate from his feelings.

So. 20 years later, he may be sitting with a friend or in therapy talking

about mealtimes at his home when he was a child. And he might say that

when he was nine-years-old, mealtimes were pretty interesting, because

his family would be eating and his mom would fall off her chair. And

he might describe this with a calm voice and a stilted smile. He might

tell you this with absolutely no sense of the feelings that initially accom

panied that experience. In fact, the feelings are there, but he has been taught

to keep them separate. As a result, he never learned how to fully integrate

his feelings, thoughts, and observations.

A child who is not allowed to talk openly about the alcoholism in the

family begins to think there is something wrong with him or her. He or

she feels confused, scared, bad, sick or crazy. And there can be no discus

sion of the situation and no explanation that such feelings are common

when you live with an alcoholic.

SURVIVAL

21

16. What are the rules that implicitly or explicitly guide an alcoholic

family?

Three primary rules are described by Claudia Black, in her pioneer

ing work with children of alcoholics.8 The rules that she found over and

over are, “Don’t talk, don’t trust, don’t feel.’’ Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse,

another pioneer who has written extensively about the alcoholic family,

notes that the rules in an alcoholic home tend to be unhealthy, inhuman

and rigid.53 She describes the alcoholic’s use of alcohol as the issue

around which everything else is centered. No other issue affects the fami

ly so deeply. Yet family rules state that alcohol is not the cause of family

problems; someone or something else is at fault; alcoholism is not the prob

lem. Additionally, the status quo must be maintained at all costs, and

everyone must take over the alcoholic’s responsibilities, cover up, pro

tect, accept the rules and not rock the boat. No one may talk about what

is going on to anyone else, and no one may say what he or she is really

feeling. To abide by these rules is to be safe; to break these rules is to

court disaster.

We find that two different sets of rules occur. One set consists of rules

the parents give to the child. These rules are built on domination, fear,

guilt, and shame. We have already talked about those. Another set of rules

is developed by the child in response to the parents’ rules. They go

something like this: “If I don’t talk, nobody will know how I feel, and

I won’t get hurt. If I don’t ask, I can’t get rejected. If I’m invisible, I’ll

be okay. If I’m careful, no one will get upset. If I stop feeling, I won’t

have any pain.’’ The prime directive becomes, “I must make things as

safe as possible.’’ But “safety’’ can exact a heavy price.

17. What impact does this family atmosphere and these rules have upon

the children?

In the midst of an atmosphere of unpredictability, inconsistency, ar

bitrariness, and chaos, the children try to make sense out of what is hap

pening. When placed in such an unstable world, they begin to think that

they are unstable and that the instability in the family is their fault. If you

could listen to what the child cannot say, you might hear something like

this: “This is crazy, so I must be crazy. Something’s wrong so there must

be something wrong with me. I haven’t got love, so I must be unlovable.

rr

22

Then further translations occur. “I must be unlovable” becomes “I don’t

need love.” “I don’t need love,” becomes “I don’t want love.” “I don’t

want love,” becomes “I will reject love when it comes because there is

no such thing; I cannot trust it, it’s not safe!” So, “I don’t need love,

I don’t want love,” ultimately become “I won’t take love. I can’t take it!”

It is easy to forget how profound the parent-child relationship is.

Children are completely dependent upon their parents’ good will and nur

turing. Parents are the people who make it possible, literally, to stay alive.

They provide the home. They provide the food. Parents are also a primary

source of a child’s sense of self worth. When the people who love them

the most hurt them the most, children often conclude that there must be

something dreadfully wrong with them. “I must be bad, sick, or crazy.”

In this way, children of alcoholics learn to distrust both themselves and

others. They learn to endure, to suffer, and to resent. They survive by

distancing themselves from their feelings and denying their needs. Feel

ings and needs are too dangerous, too painful. Instead, children in families

of alcoholics learn to control; they learn to pretend or to lie or both. As

a result, they learn to blur, distort, and confuse.30 Love becomes con

fused with caretaking, spontaneity with irrationality, intimacy with smother

ing, anger with violence. Just as alcoholics blur their view of the world

due to alcohol, children blur the boundaries of feelings, thoughts, and

behaviors due to the alcoholism of the parents.

Often a child is explicitly told by a parent, “You are the reason why

I'm feeling this way. . .why I’m drinking. . .why I’m this. . .why I’m

that. It’s your fault. If only you. . .” Children are wonderfully self-centered.

All young children tend to think that they are the center of the universe;

so it is very natural for them to incorporate these immensely powerful

statements or suggestions by the parent. When told something often enough,

we believe it. The children of alcoholics often do believe they are the cause

of the problems in the family, and therefore feel they should be able to

cure or control the situation. That need for control follows them through life.

18. How do children adjust to this very repressive environment?

Research from the field of family therapy shows that family members

adopt identifiable role behaviors when they are under stress. And all

alcoholic families are under stress. These roles are adopted both to save

the family and to save the child. Virginia Satir, a noted pioneer in family

therapy, first described these roles for distressed families in general.5

II

SURVIVAL

RECOVERY

'•

S

23

More recently, both Claudia Black and Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse, a stu

dent of Satir, separately described common roles specific to alcoholic

families.8,53

Black’s initial work came from her observations of the children of

alcoholics seen in inpatient treatment programs.6-7 She noticed that

although most of them seemed to have adjusted quite well on the surface,

they did not seem to feel. While there are certainly many overtly pro

blematic children from alcoholic homes, the majority are so busy looking

good, so busy people-pleasing, that they are overlooked and ignored. In

addition to the “acting-out” or delinquent child, most children adopt one

or a combination of the following three roles: the responsible one, the

adjuster, and the placater.

The “responsible one” is usually the first-born and often the only

child. This child’s behavior is organized around the principle, “In the midst

of chaos. I’ll do it and take care of it.” This is the child who begins to

pick up responsibilities left behind by a trail of alcoholism and co

alcoholism. These children typically are the marvel of the neighborhoodup very early, to bed very late and, in between, doing everything that needs

to be done to run the household. Mature and reliable beyond their years,

these children will set their own alarm clocks for the morning, get their

younger sisters and brothers up, and make sure that the other children

get breakfast. They may even be the ones who are in charge of getting

their parents up for work. They are the children who will come home,

fix dinner, and then do laundry. They are like the child Black described

who had seven sheets of paper along the wall in her room outlining her

duties every hour of the day, including one specific hour to relax and play.

The child was so responsible that, amid everything else, she also knew

she was a child and should play. So that was scheduled in, too. This is

a child who does very well in school, and does not come to anybody’s

attention as having problems. In fact, these children are often seen as very

good, very well-adjusted. This might be the teenager who stays after class

with her English teacher to help grade papers, who helps other children

with projects during class hours, who hands in her paper early. This ac

complishes several goals. Not only does the child represent the family

positively to the community, she also acquires a sense of stability and control

in one area of her life.

The second role is one Black refers to as “the adjuster." The ad

juster’s guiding thought is, “In the midst of chaos. I'll ignore it." For

example, this is the child who seems impervious to the effects of the

24

environment, and he or she adjusts or adapts by detaching. This is the

child who sits at the dinner table, watches his mother fall from her seat

and seems not to notice, continuing to eat without missing a single bite.

This child can sit in a room watching TV while there is screaming going

on and continue with whatever he or she is doing no matter what is hap

pening, apparently oblivious to the environment. The neighbors or the

parents might say, “How wonderful that Aaron doesn’t seem to be affected

by the problems at home.” Or the teacher might say, “Aaron? Who is

Aaron? Oh! He is the quiet kid who sits in the back of the room and never

says anything.” These children can go through many situations, even an

entire school year, and not be noticed. They adjust so well; they make

so little noise that it is easy to completely miss them. These are the children

who will go along with any and every suggestion because they seem

unwilling or incapable of making decisions. They will shrug their shoulders

and say. “It doesn’t matter,” since they have no sense of their own needs.

Somewhere along the line they lose that sense of power and self through

a belief that they cannot affect their environment or their own lives.

The third role Black calls “the placater.” The placater’s guiding prin

ciple is, “In the midst of chaos, I’ll fix it and make it better.” What placaters

fix are people’s feelings, worries, troubles. They learn to be so sensitive

and perceptive to what is happening that they can walk into a room, and

without even consciously realizing it, figure out just what the level of ten

sion is, who is fighting with whom, and whether it is safe or dangerous.

And reflexively they begin to diffuse whatever tension is in the room.

Placaters are excellent conflict resolvers and negotiators. They work hard