MFC 5TH ANOTHOLGY HEALTH IN THE 1980'S ISSUES AND PERSPECTIVES

Item

- Title

- MFC 5TH ANOTHOLGY HEALTH IN THE 1980'S ISSUES AND PERSPECTIVES

- extracted text

-

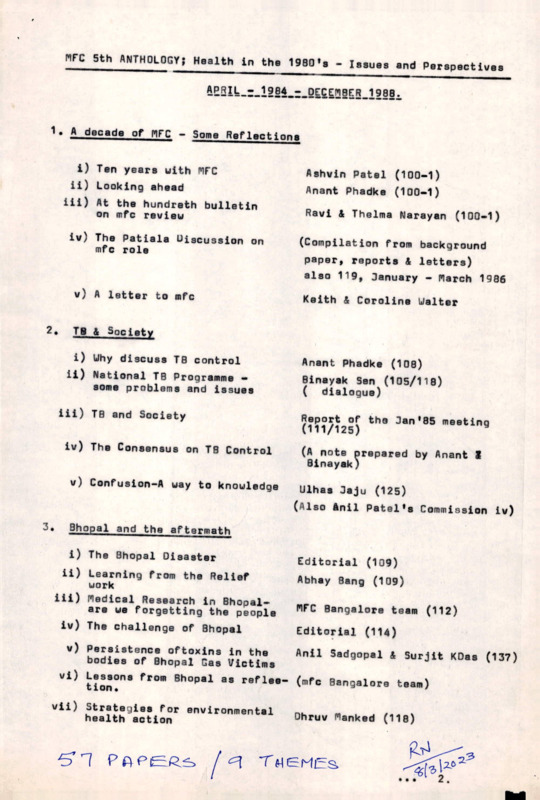

MFC Sth ANTHOLOGY; Health in the 1980'3 • Issues and Perspectives

APRIU-r-lEeA^^DECEriiBER^iges^

1• A decade of MFC • Some Reflections

i) Ten years with MFC

ii) Looking ahead

iii) At the hundreth bulletin

on mfc review

Ashvin Patel (100-1)

Anant Phadke (100-1)

Ravi & Thelma Narayan (100-1)

iv) The Patiala Uigcussion on

mfc role

v) A letter to mfc

2e

(Compilation from background

paper, reports 4 letters)

also 119, January - March 1986

Keith & Coroline Walter

TB & Society

i) Why discuss TB control

ii) National TB Programme —

some problems and issues

Anant Phadke (108)

Binayak Sen (105/118)

( dialogue)

iii) T0 and Society

Report of the Jan'SB meeting

(111/125)

iv) The Consensus on T0 Control

v) Confusion-A way to knowledge

(A note prepared by Anant I

Binayak)

Ulhas Jaju (125)

(Also Anil Patel's Commission iv)

3.

Bhopal and the aftermath

i) The Bhopal Disaster

Editorial (109)

ii) Learning from the Relief

work

iii) Redical Research in Bhopalare we forgetting the people

iv) The challenge of Bhopal

Abhay Sang (109)

MFC Bangalore team (112)

Editorial (114)

v) Persistence oftoxins in the

Anil Sadgopal & Surjit KDas (137)

bodies of Bhopal Gas Victims

vi) Lessons from Bhopal as reflee (mfc Bangalore team)

tion.

vii) Strategies for environmental

health action

Dhruv flanked (118)

TMGMiEs.

>

2.

• £

Family Planning controception and Women1a Health Issues

i) Family Planning in India:

Theoretical assumptions,

implementation and alternatives

Leela Visaria

ii) Editorial

Sathyamala (129)

iii) Two decades of sterilization

Modernization and Population

growth in a rural context

Stanley A freed(129)

and Ruth S freed

iv) A femanist understanding of

contraception

v) Injectable contraceptives

Manisha Gupte (121)

vi) The E.P. Case

Mira Shiva (143-144)

vii) Use and abuse of Bio-Medical

T echnology

Amar Jesani (124)

viii )Sex determination and female

f oeticide

Garbha Parikshan

Virodhi Maech (146)

ix) Dialogue

Abortion

Victim blaming is not the

solution

Arun Gadra (146)

One Daughter Family: Fact or

F ancjj

5.

(MFC Annual meet rejbort

mfcb131)

Padma Prakash (113)

Amar Jesani (146)

Ulhas Jujoo/S.P. Kalantri

(146)

Child Health Issues:

i) Child health in India what is our commitment.

ii) Child health in India

Ravi Narayan (106)

Editorial (133-134)

iii) Child health in India

Report of XIV Annual Fleet

(138)

iv) Paralytic Poliomgetitis A tragedy on the rise

Gloria Surrett (130)

v) Universal child immunization

and child survival: A positive

view.

Ashok Bhargaea (133-134)

Anil Patel

vi) Sex differentials in Nutritional

status in Rural Area of Gujarat

State - An Interim Report.

Leela Visaria

vii) Child care and the prosperity

of Punjab - A reflection.

Sameer Chaduhuri (106)

viii) Blened are the small in sizeif they are Indians.

Kamala S. Jaya Rao (115)

xx£

3

6• Rational Drug Policy 13sues:

i) Doctors role in the RDP Movement

ii) A letter to the Drug Controller

iii) Drug awareness and Action

iv) Fighting for a peoples Drug Policy

— the KSSP experience

Editorial(l03)

Anant Phadke (107)

Editorial (107)

B Ekhal (Dec 85)

v) Scientific medicine

(112)

7. Technology and Health Care.

8.

i) Medical Technology:neither glitter/

nor gold.

Ulhas Oajoo/S.PeKalantri

(145)

ii) Emerging Medical Culture

Ulhas Sajoo (115)

iii) Clinical perspective: Chest

Radiography

S.P. Kalantri (145)

iv) Beware of X rays

S.G. Kabra (145)

v) Transtechugue aspects of Disease

& Death

M<La Kothari &

Lopa A. Mehta.

Primary Health care issuess

i) Towards an appropriate strategy

Eood is the Hands of Big Industry

iii) Logistic support and facilities

for primary health care

iv) Pricing the medical care in

Government hospitals-problem and

alternative solution

v) The Indo V vaccine Action Programme

- A recipe for Disaster

vi) Choloroquin, Cholera and mfc

vii) Media as a tool in Health Action

9.

A

Ulhas Oajoo (102)

Kamala S. Jayaroa 014^

Ashish Bose (137)

Abhay 4 Rani Bang (39)

Proful Bidwan

(148)

Editorial (148)

V imal Balasubramanian

(127)

Politics of Medical Work

i) Conventional medical work

ii) Radical Medical work

iii) Myths perpetucted by the

Voluntary Health Sector

Anant R.S. (141)

Anant R.S. (142-143)

Sathyamala (142-143)

I

4

9. iv.

v.

Narmada Project and Retribals

The HARD Strike - A view Point

10. when Rome is Burning: A Dialogue

'

!\

-*-*-*-*-*-

'I

ARCH, Mangral (104)

Sanjay Nagral (108)

Arun Cadre &

Jyothi Cadre (124)

Dileep Havalankar (126)

Kamala

Oaya Rao (126)

Mukund Uplekar (126)

Sujit K. Das (128)

Marie D* Souza (129)

Dhruv Mankad (130)

Rita Priya (130)

POTENTIAL ARTICLES FOR S’th ANTHOLOGY

Subject

Author

A Feminist Understanding of

Contraception

Manisha Gupte

124

Use and Abuse of Bio-Medical

Technology (Amniocentesis A Case Study)

Amar Jesani

124

When Rome Is Burning

Arun & Jyothi Gadre

Confusion - A Way to Knowledge

U.K. Jajoo

Tuberculosis and Paramedical

Workers

Marie D’Souza

mfc bulletin

No,_____

^21

125

125

\

\

126

When Rome is Burning (response) Dileep Mavalankar

127

Media as a Tool in Health

Action

Vimal Balasubrahman

127

hen Rome is Burning

responses)

Kamala Jaya Rao

Mukund Uplekar

128

Integration of Medical

Systems (A theoretical

Perspective and Practical

Blue Print)

S.K. Kelkar

128

When Rome is Burning

(response)

Sujit K. Das

129

When Rome is Burning

(response)

Marie D*Souza

130

When Rome is Burning

(responses)

Rita Priya

Dhruv Mankad

131

Family Planning in IndiaX:

Theoretical Assumptions,

Implementations and

Alternatives

(XIII mfc Annual Meet, Kaya)

Leela Visaria

131

Integration of Medical Systems

(response)

B.K-w Sinha

131

A Letter to mfc

Keith and Caroline

Walker

• •2

:2s

Author

mfc bulletin

No.

Subject

132

The Epidemiological Approach :

Its Elements and its Scope

Ritu Priya

132

Injury Prevention and Basic

Preventive Strategies

Dinesh Mohan

133 &

134

Universal Child Immunization

and Child Survival x A

Positive View

Ashok Bhargava &

Anil Patel

133 &

134

The New Drug Price Control

Order - A mockery of rational

planning

Anant

135

Persistence of Toxins in the

Bodies of Bhopal Gas Victims

Anil Sadgopal 6c

Sujit K. Das

136

Sex Differentials in Nutritional Leela Visaria

Status in a Rural Area of Guja

rat State : An Interim Report

- Part - I

137

Sex Differentials in Nutritional Leela Visaria

Status in a Rural Area of

Gujarat State - Part II

137

Logistic Support and Facilities Ashish Bose

for Primary Health Care (Crucial

Role of Physical Accessibility)

138

Child Health (XIV Annual Meet

of mfCf Jaipur)

Sathyamala

139

Pricing the Medical Care in

Government Hospitals :

Problem and Alternative

Solution

Abhay and

Rani Bang

141

Politics of Medical Work

Part I : Conventional Medical

Work

Anant

R.S

142

143

Politics of Medical Work

Part II : Radical Medical Work

Anant

R.S.

142

143

Politics of Medical Work - III

Myths Perpetuated by the

Voluntary Health Sector

Sathyamala

142

Issues for Debate on Peoples

Science in Health Care

C.R. Bijoy

R.S.

• •3

3

mfc bulletin

No.

4

Subject

Author

143

144

The E.P. Case

Mira Shiva

145

The Trans-Technique Aspects

of Disease and Death

M.L. Kothari and

Lopa A. Mehta

145

Beware of X-Rays

S.G. Kabra

145

Clinical Perspective : Chest

Radiography

S.P. Kalantri

145

Medical Technology : neither

glitter, nor gold

U.N* Jajoo &

S.P. Kalantri

146

Patient*s Right

Anil Pilgaonkar

146

Sex Determination and Female

Foeticide in Baroda

Garbha Parikshan

Virodhi Manch

146

Victim Blamin Is Not The

Solution

Amar Jesani

146

Dialogue : Abortion

Arun Cadre

146

One Daughter Family : Fact

or Fancy?

U*Ne Jajoo &

S.P. Kalantri

I Block, Koramangala,

Bangalore - 560 034.

3rd August 1992

PHONE ? 53 15 18

k Dear Friends,

Greetings from Community Health Forum!

We had a very interesting meeting on 11th July 1992, when the CHC

Team presented an report of its activities and concerns mostly

through visuals and we got an enthusiastic and stimulating

response from 48 of our Forum members and associates. Many ideas

and suggestions were shared and CHC got a lot of stimulus to work

upon in the months ahead, A detailed proceeding of the meeting

will be sent to all of you, shortly, A short summary is given

overleaf for the benefit of those who could not attend.

This is just to keep you informed that the next two Community Health

Forum Meetings have been arranged.

1o Date

; 14th August 1992 (Friday)

Tine

: 2.30p.m. - 4.30 p.m.

Venue

: Ashirvad,

30, St.Mark’s Road,

Bangalore

560 001.> (Phone 2 21 01 54)

Dr. Vanaja Ramprasad will report on the RIO Conference issues and concerns that should be of relevance to us as

Community Health action initiators.

2. Date

z 5th September 1992 (Saturday)

Time

: 10.30 a.m. - 12.30 p.in.

Venue

s Ashirvad,

30, St. Mark’s Road,

Bangalore ~ 560 001 (Phone; 21 01 54)

Prof. Ravi Kapur, Deputy Director, National Institute of Advanced

Studies (better known to all of us as one of the key pioneers

of the Community Mental Health work of NIMHANS) will share his

perspectives onllYoga and Mental Health’’ deriving inspiration

from his own experiments in this area.

Shirdi Prasad, the facilitater of our Forum has gone .to Sri Lanka

on a special assignment to review Community Health needs of

refugees from the troubled zone..He

He will give us an additional

first hand report on <one of these occasions,. depending on when he

returns.

We look forward to your participation with the same enthusiasm and

numbers witnessed on 11th July 1992.

A pamphlet and newsletter released on 11th July 92 is enclosed for

all those who could not make it to that meeting.

With best wishes from the CHC Team.

See you on 14th August and 5th September.

1

_si ncerelv.

18 percent response. The latter was prompted by

a crisis situation which arose when the then editor

perceived a lack of participation and support and

serious discussion regarding continuation of the

bulletin ensued.

The survey showed an overall

support for the bulletin, which then got a fresh

lease.

1978

1979

Readership surveys

Critique :

Abstract analysis

Too much criticism

Too little constructive suggestions

Increasing formality

Suggestions :

— More experience reports

— Recent advances and appropriate

health care techniques

— More editorials

— More organisational news

— More variety in authors

Responder characteristics :

Medicos — 68%

Non-medicos — 32%

Members — 65%

Field Workers — 10%

Medical College teachers — 35%

Response :

Most popular — title articles and

materials

Bulletin useful — 90%

Existing system irrelevant — 90%

Alternative possible — 90%.

fb)

Availability of articles : Though the Bulletin

appears to have appeared regularly, editors

have had their range of reading and article

extracting ability stretched to the extreme,

resulting in frequent crisis. Typically in

1980, there was an appeal in June as fol

lows : "If this state continues the last issue

will appear in July”.

The crisis was most

often got over by reprint of suitable articles

from other sources. Many were very good

and added an important dimension to the

bulletin. However, lack of original articles

can be not only a health hazard to the editor,

but it also question the creativity and dyna

mism of our membership 1

(d)

Printers' devil : This has not been as much

of a problem as it could have been in a small

bulletin of this nature because of a series of

meticulous proof readers. On occasion, how

ever, it has caused some degree of embarrass

ment and often comic relief. Recently, in

the front page of the bulletin, 'health' our

main preoccupation was wrongly spelt and

'mgc' not 'mfc' was committed to achieving

it by 200 A.D.

With the increasing diversity in membership,

MFC may have to consider producing bulletins/

newsletters directed to stimulating 'thought cur

rents' at different levels.

A bulletin with this perspective and supported

by subscriptions and donations only, is bound to

have many problems. The three most important

often reported in the bulletin were :

Focus : With the diversity of readership and

their expectations 'selection on material for

the bulletin is a gymnastic more difficult than

walking on a tight rope'. (31).

Finances : This has been a chronic problem

throughout, but the remarkable ability of con

sequent publishers to continue against all

odds deserve real kudos. MFC has fiercely

guarded its independence by committing itself

to a policy of financial support by subscrip

tions and personal donations only. It was felt

that external project funding would result in

some inevitable institutionalisation, possible

loss of independence and very likely decrease

in the personal support of committed mem

bers. The increasing deficit has constantly

challenged this stand and the discussion in

1983 finally resulted in a more open policy of

funding with certain restrictions to maintain

our value stand (87).

The future

Some problems

(a)

(c)

The 'demystification of medicine' and 'the

evolution of a style within reach of the common

man' are two important but neglected dimensions

in the bulletin. The fact that many of our member

writers also write for the popular press in the

regional language is some cause for satisfaction

though this needs to be promoted much more

through MFC in the future.

In conclusion the hundredth milestone of our

bulletin has been reached through an exciting and

exacting collective endeavour. What has been the

contribution of this effort to health related thinking

in India in the last decade- only the future will tell.

Ivan lllich, when interviewed in 1978 is reported

to have said that "the bulletin was the best periodi

cal in the third world which analyses health struc

ture and its problems”. Two readers in the 1979

survey on the other interestingly felt that the

the health care system in India was relevant and

that the bulletin had been responsible for their

opinion! Only our readers can decide where we

stand between these two extremes.

9

I

IpC

K

-iv11

I

prescribing. Certain unusual problems like Lathy

rism, discrimination against women in health,

disaster medicine etc., have also been presented.

By and large, however, tne range has been within

ihe traditional boundaries of medicine — both

clinical and community with a strong preoccupa

tion with nutrition, health service policy and drug

issues.

may be representative of the fact that many

of the analysts of yester years are deeply

immersed in action today. In turn these rea

listic issues may be instrumental in stimulat

ing further activism: in MFC circles.

Here

again we are vulnerable to the criticism that

the emphasis on drug issues represents

medical bias but this is inevitable in our pre

sent doctor oriented predicament.

Non-medical issues which are vital to health

care have been covered peripherally with stray

articles on green revolution, dairying, soya bean

and low energy economics.

Vocal Figures

Feature

Three areas stressed in the MFC manifesto

have been particularly neglected.

These being

demystification and popularisation of medical

science, humanisation of medical/health practice

and the open-minded enquiry into non-allopathic

systems of medicine and non-drug therapies.

Does this reflect the existing professional/

medical bias of the group?

Even within the traditional boundaries of

medicine certain issues like ecology and environ

mental health, health problems of tribal regions

and urban slums, workers health, the clinical

investigation, business, unnecessary surgery, malpraxis, the nuclear epidemic and the relevance of

existing research in the country have hardly been

considered. Emerging issues important in a wider

context but relevant to the health movement like

pedagogy, communications, participatory manage

ment and humanistic psychology among others

need also to be included.

1.

2.

3.

4.

Book reviews

32

26

24

17

64

14

1

13

8

8

2

4

2

8

2

8

Activity reports

a. mfc groups 8

b. health

projects

1

(c)

Activity/Project reports : Reports by small

groups all over India with an MFC perspec

tive have been featured on and off. Reports

on projects like Jamkhed, Gonoshasthaya

Kendra and CINI have also appeared. Consi

dering the wealth of field experience gained

in India in the last decade this is an area

I

7

26

19

Discussions/dialogue : The thought current

nature of MFC should have made these a dis

tinctive feature of the bulletin. The experience

has been different. The first phase saw a

very active response from members. Even

though these were often the same inveterate

discussants, they set a healthy precedent. The

second phase saw a very active response from

members. The second phase saw an increase

in this phenomena with a much wider cross

section of readers participating in columns

such as Hyde Park/Dialogue and contributing

letters to the editor. In the last four years

this phenomena has begun to wane and should

be a cause of concern. Are bulletin readers

so busy with their own local preoccupations

that they do not find time to participate in

discussion or is the Bulletin not adequately

thought provoking? Are there many other

factors?

Only a readership survey could

probably throw light on this.

The format of the bulletin has shown much

variation but certain basic features have remained

constant.

These have been the key

L^ad articles :

feature of the bulletin. They have included

original articles written by members and con

tacts as well as reprints from other journals

and sources. These articles have been very

responsible for the reputation of the bulletin.

The selection has been surprisingly consis

tent in terms of relevance and analysis in

spite of the fact that there has never been a

very clear cut editorial policy — our mani

festo reworded from time to time being the

only guiding principle.

Of late the articles

have moved from a more abstract analysis of

issues like health policy to more concrete

like drug misuse, community health worker

and health education.

This concretisation

Articles

a. original

32

10

b. reprints

Letters to

Editors/readers

dialogue

49

(b)

Features

(a)

Phase of bulletin

1-25 26-50 51-75 76-100

I

CHC / ?1EP /

Research Project

Strategies for Social Relevance and'Community

Orientation in Medical Education

:

Buildina.

on the Indian Experience

A

PROCESS

REPORT

Community lldalth CeM ,

Jyune

e

Bangalore#

1992 \

Sponsored by f Christian Medical AssociaVion of India (CMAI).

Catholic Hospital Association of India (CNaI), Christian

Medical College, Ludhiana ( 3MC-L ) .

\

* Society for Coniiiuni ty HealtH Awareness, Research and Action

No. 326, V Main, I Block, Koranian^’ala, Bangalore - p60 034.

/

I ( i i i)

needing much more attention.

Reports of

well-known projects are not as important as

sharing by friends of the little lessons in their

field experience, the new perspectives gained

and the small but appropriate innovations

made. The Sevagram group has been parti

cularly remarkable in such little inputs.

MFC organisational reports have been a con

sistent and welcome feature. The informal

nature of these reports have been typical of

MFC. Reports of the lively group discus

sions at the meets have helped those who

cannot attend the meet to get a feel of the

frank and open style of MFC group work.

(d)

(e)

(f)

(s)

Surprisingly in a hundred issues less than

twenty books have been reviewed. These

have included the classics by lllich, Maurice

King, Mendelsohn and Morley and the ICMR

and WHO compilations of alternative approa

ches. In the light of the recent explosion in

health care literature this is a serious lacunae

in our efforts. Not that all the material avail

able is necessarily relevant to the MFC search

but there is an urgent need to keep members

and readers upto date and well informed, if

this quest for an alternative people oriented

health system is to be built on a scientific

(h)

base.

*- ::

In recent

Government policy documents

significant

output of

years there has been a i \

and

related

government policy documents

reports taking a new look at the Indian situa

tion and supporting/professing alternative

approaches. By and large the MFC bulletin

has carried active response to each of these

— the Srivastava Report, the Janata Health

Policy, the Medical Education Policy and the

Health for all Report. The lack of response

to the new Health Policy of 1983 is a serious

omisssion. This active analysis and feedback

is particularly crucial because the reports of

late feature very radical statements and pro

grammes that create myths and some confu

sion.

These reports seldom mention the

process by which these radical changes can

be actually introduced into the existing exploi

tative and irrelevant systems. MFC members

have a definite role to bring out these contra

dictions and also apply themselves to issues

of process ignored by these reports. At the

same time we need to emphasise those

elements which are helpful to the evalction of

literature m health, job opportunities and other

available resources. In 1978-79, a column

of news clippings to keep readers informed

about issues raised in the popular press was

attempted. In the absence of a documenta

tion centre to back the efforts of the editors,

this has been a low key feature.

Editorials : Like the lead articles these have

been a distinctive feature of the bulletin

though the style has varied greatly. The

first phaes saw annual editorials setting

measurable objectives for the bulletin but

remaining a silent catalyst in between. The

second phase saw a more regular feature

which not only galvanised the group work but

also put the contents of the bulletin in the

MFC perspective. The last four years has

seen the evolution of a more analytical and

technical editorship which has put the bulletin'

on very scholarly foundations.

Miscellany: Bulletins 1-29 had the Chinese

slogan "Go to the people, live among

them........ " at the bottom of every page

expressing the beginnings of the MFC quest.

Bulletin 30-35 saw the introduction of five

additional features — these being Hindi

articles, health related poetry, cartoons and

line drawings, a contents list and provocative

gimmickry to enhance readers participation.

JR was the only personality to be honoured1

in the front page being a sort of chief

inspirator of the group (46). He displaced

the red disc from top right to right down. In

cidentally the red disc was not selected to

depict the rising sun of revolution but was a

practical attempt to balance the numbers and

break the printed monotony of the first page.

Coincidentally this gave the bulletin its

popular and recognisable symbol.

Anthologies

Twice in recent years, anthologies of the best

original articals were published by MFC. The first

(In Search of a Diagnosis) covering issues 1-24

and the second (Health Care — Which Way to Go)

covering issues 25-50, have both seen a pheno

menal popularity. The first one is now out of print

while the second one is on its way out. The third

anthology is a scheduled to be released later this

year.

Readership surveys

To enable mid-course corrections and get a

feel for the readers views, readership surveys have

been undertaken. Twice, these have been reported

in the bulletin. The 1978 survey elicited only a

nine percent response while the 1979 survey an

a more humane and just system.

Information : Most bulletins have featured

snippets of information on recent events and

8

I

I

1

AT THE HUNDREDTH MILESTONE

Ravi and Thelma Narayan

mfc is as of today, mainly a thought current and the monthly medico friend circle bulletin........

is the medium through which members communicate their ideas and experiences to each other.

Running the bulletin in our chief common activity........

MFC

manifesto 1983

have evolved as time went by — being modified,

re-emohasised and added unto (see Index). Against

the background of these wide objectives the evo

lution and performance of the bulletin has shown

an interesting variety and a rich diversity. Atleast

once during this eight year period a situation of

crisis (45) called into serious question continuation

of the bulletin but the heated discussion threw up

three reasons of organisational significance which

made the bulletin necessary in addition to its

wider relevance. These being that the bulletin was

the only means — to be heard at national/international forums; to involve the new members; and

to prevent degeneration into a federation of local

scattered groups. All these objectives taken to

gether gave the bulletin a new lease of life at

every crisis.

In this centenary issue, as we reflect on the

past, consider rhe present and look into the future,

w'e review the preceding ninty-nine issues of the

bulletin, to discover the strengths and weaknesses,

the opportunities and threats that have been part

of its eight years history.

The Beginnings

The MFC bulletin began as a cyclostyled

note that was circulated regularly to members of

the initial nucleus group, many of whom had links

with the Tarun Shanti Sena in 1974-75. Our re

cords show that there were atleast fifteen such

notes. The style was informal — a sort of 'dear

friends' newsletter keeping members about meettings and discussions, field opportunities and

thought provoking articles on various relevant

health issues.

Founder members will probably

recall with nostalgia the series on the present

health system, 'alternative approaches' and 'radical

medicine', the column entitled 'vocal figures' pre

senting telling statistics of the health situation in

India and the proclamation of Maurice King's book

as the ''bible for every doctor"! The characteris

tic feature of this embryonic phase of the bulletin

was its youthful idealism and infective enthusiasm.

Rallying slogans such as "If China can do it why

can't we?" and 'let's coordinate our efforts to fight

the situation instead of blaming western culture

and criticising brain drain' were typical examples.

Outreach

The bulletin subscription has ranged from

250-700 over the years. Presently it is a little

over 400. The readership includes rural health

project workers, medical students, medical college

teachers, academicians, research workers and non

medicos interested in health.

These are spread

out all over the country but more particularly in

the Western region — Gujarat and Maharashtra —

the traditional home of MFC. A detailed break

up of the subscription list is not yet ready but a

cursory perusal indicates that the readership among

medical students and non-medicos is still far from

significant.

The MFC bulletin as we know it today took

shape at the second annual meet at Sevagram in

December 1975. The first editorial committee

was formed and a plan of issues outlined for the

whole of 1976. The first bulletin was printed in

January-February 1976. Since then the bulletin

has travelled a long way — 93 months of regular

printing, seven double issues, three editors and

seven printing press — to reach this hundredth

milestone.

Scope

The articles featured in the bulletin have

represented a very varied range of topics related

to medicine and health. An index of the hundred

issues which is featured as a supplement to this

bulletin shows twenty eight sections in the classi

fication.

These include health services, medical

education, maternal and child

Objectives

Though the initial objectives were outlined in

the first issue — as many things in MFC, these

control,

communicable

sanitation, mental health,

6

health, population

diseases,

drug

environmental

policy and drug

'5

M•

fy.

r

I

For the last eight years, we have been involved

in health and development work in villages. We

feel it was very fortunate that one of the first books

we read on arrival was 'In Search of Diagnosis': it

helped orient us along the right lines and led us to

become members of mfc, which has always seemed

like a lone voice of sanity crying in the wilderness

of India's health care scene. Now, as we prepare

to leave India, we want to offer our congratulations

for keeping up the critical analysis, and our grati

tude for all we have learned from you over the

years. Reading through the latest anthology re

minds, us that it was on your advice that we threw

out the Terramycin 2cc injections, the Novalgin,

the tonics and all other rubbish, and promoted

ORS in the clinic; and after the TB meet in

Bangalore, our TB programme was revised and

improved.

7

c

The dreadful state of health care in India is

well known to readers of mfc bulletin. The back

ground papers of the Family Planning Meet make

particularly saddening and infuriating reading. We

used to look on this work as a challenge: but after

eight years of close contact with-the health prob

lems of the rural poor, we have to say that we feel

sickened and depressed by the

amount of

ignorance, greed and exploitation which permeates

every level of what passes for 'medical care' for

the majority, of people. Our solution has to be

that there can be no solutions without political

solutions; and that in that movement, we as foreig

ners, have little role to play. It has to be upto you

all then in what looks like a long hard and bitter

struggle.

Keith and Caroline Walker, Valiparai

medico friend

circle

bulletin

APRIL-MAY 1984

TEN YEARS WITH MFC : MY PERSONAL VIEW

ASHVIN J. PATEL

When I was told to give my reflections upon

ten years of MFC, I accepted it reluctantly. Firstly,

because1 I did not have many things to say and

secondly it was not spontaneous for me. However,

I give some stray thoughts that occurred to me.

An Overview

>

'v'

Many of the readers may not know that MFC

was not a planned efforts but a spontaneous one.

It orginated from a socio-political movement Tarim

Shanti Sena which was inspired and ignited by zeal

for total revolution.

Naturally MFC carried

legacy and hang-over of this perspective, values,

culture etc. Many of the founder membersi were

considered radical and unorthodox Gandhians.

Within a year it could attract friends who rang

ed from academicians to field activists; not suprisingly it also included various shades' of opinions from

light to left. I do remember that some friends

clearly denied then, that the doctor has any other

responsible role than treating patients coming to

the dispensary. While others, on the other hand,

felt that health sendees are just an entry point

into the community.

Real health work iis to

struggle for socio-economic-political revolution.

This latter viewpoint was shared by both, the

Gandhians and the Marxists alike.

MFC criticised the present health system and

its approach so eloquently and vociferously that it

could attract attention of many young doctors and

non-doctors. The “prophetic vision” and enthu

siasm of old members proved to be too much for

some. A few resented the indoctrination and the

aggressive way of discussion. A proportion of

them felt that MFC could not give a relevant pro

gramme according to their aptitude and abilities.

There was a feeling that MFC wanted everybody

to agree with its analysis, and then left them alone

to face the frustrating situation.

In the first four years, study-cum-work camps

were organised for medical students and others

which generated lots of enthusiasm. Some medical

colleges could evolve health care programmes for

slums and nearby villages. Many of them are still

continuing. But/perhaps, except for a few, there is

no continuous follow-up and dialogue. They have

become just like any philanthropic dispensary

without having a wider perspective of community

health and development.

How would one measure the progress of such

an organisation? By the number of its members?

It’s impact on societjy? The growth of its 'members

as a collective to understand, analyse and respond

to a situation?

As experience showed the annual meets of

MFC served a purpose as a major point of contact.

However, new participants felt isolated, the target

of indoctrination and threatened by the level and

nature oft discussions. The objective of increasing

the number was not to be realised effectively. Old

members felt that the preoccupation with new

members kept the level of discussion at a preliminaiy level. There was no scope for learning and

mutual growth. Robust, impersonal and objective

arguments were appreciated and welcomed by old

members, while many of the new members perceiv

ed in the same exchange of views, aggressiveness

that tended to be personal. I feel that in the ten

years, MFC members have shown a lot of maturity

to take the arguments and criticism as that of the

thought and not of person. No one ever doubted

another's genuineness, honesty of purpose and

concern for the poor. Even after a session of hot

and involved exchanges there has been no tyace of

bitterness and the feeling of friendship and soli

darity has always grown. To an onlooker sometime

it may seem that we are simply splitting hairs and

are involved in mere polemics, But this seeming

polemics represents deeply held differing view

points, perspectives, social & political ideologies

and backgrounds.

In the first few years, the number of MFC

contacts increased very fast. It might, have been

due to the long felt need for such .a forum, the

unconventional and critical views appearing in

MFC bulletins, the annual meet deliberations or

the regional camps, Then its growth in number

Not only the numbers stag

rached a plateau.

nated, but also the core group, which evolved

spontaneously due to continuous interaction and

concern for the MFC organisation, developed a

kind of disinterest in the organisation. What was

the origin of this disinterest?

lions, concepts, valines and models like bare foot

doctors — C.H.W.; underfive clinic; campaigns

against bottle feeding, commercial foods and irra

tional therepeutics, attacking drug industry, alter

native simplistic curriculum for medical schools;

people’s participation; demystification and de

institutionalisation of health care; self-sufficient

health care programmes; self help; promotion of

other sysetms of health care: etc., etc.,” (to be refe

rred hereafter for sake of brevity as ‘health care

mix’). And even proponents of the first trend,

though grudgingly endorsed this ‘health care mix'

without providing overall framework or model

linking it with the process of socio-economic

change. This led to a lot of confusion in some

and smugness in others.

An interesting current was emerging intertwined

with the other trends, now and then. How as a

group were we going to evolve methods and a pro

cess of self learning conducive to personal as well

as collective growth? This perceived need was not

adequately responded to, which led some to dis

continue their interaction with MFC in despair.

However, a sizeable number of members continued

tenaciously to struggle to find the way tout. This

struggle was not born out of merely .'emotional

attachment to the organisation, but because the

needs and tasks were demanding so. Moreover,

MFC may be small in terms of resources, infra

structure and manpower, but perhaps it is the only

organisation struggling collectively to search for a

socially mjeaningful and durable alternative. It has

evolved and practised certain norms in public life

consistent with its objectives and concern for the

poor.

Various Trends

There were three discernable trends within

MFC

First trend wanted MFC to be a body to

provide deeper analysis of the health situation and

its relation to socio-economic-political factors.

Second one wanted it to experiment in alternative

health approaches at micro level informed with

critical analysis of present health system. Third

trend wanted it to promote philanthropic health

services. The last trend got disillusioned immedia

tely. They thought MFC with such a thorough

critique of present health affair would now come

out with new sefs of concrete alternative program

mes. This was not to be. Although attempts

were made, through regional camps and some

health care programmes involving a few medical

colleges, to introduce this 'analytical process to new

comers; a number of constraints (prevailed.

A

questioning process could be initiated, but the

view-point that not only socio-economic changes

were precondition for improvement of health, but

also that “real activity” to be taken up had to logi

cally aim/ed at socio-economic change, had a para

lysing effect on many.

Not surprisingly, the second trend also consi

dered a socio-economic change to be precondition

and also aim of their health activities. They could

go upto a point in analysing alternative health

approaches in India and elsewhere. They agreed,

in their eagereness for action, ot “certain intewen-

A lone but (emphatic voice was raised which

was appreciated by many about a rush for alterna

tive and much ado about ‘health care mix'. No

efforts were put beyond refuting certain historical

events and pointing out some limitations and defi

ciencies in various work. A point of saturation of

thinking and imagination seemed to have arrived.

I remember how one strong protagonist of

community health got alarmed when government

agreed to implement CHW scheme at national

level. His instant reaction was, “Now government

has agreed to implement CHW scheme, what role

and functions are left for us!” This 'was an indi

cation of poverty of understanding and arrest of

growth at a given time point. But experiences in

the field had shown that the ‘health care mix’ was

2

r

4

H Fc

i

I kF1

Wo

FOO' I O I

I-

'world. If yes, how can we go about it? It may

need broadening of our focus to include those from

academic institutions who have knowledge, compe

tence and aptitude to contribute to such efforts.

Simultaneously, we have to learn and develop our

abilities to understand not only social sciences but

natural sciences too. We may have| to work out

overall plans Of action informed with this perspec

tive and ipersuade ourselves and other groups to take

up some of these commonly agreed upon activities

over a period of time so as to improve our insight

as a collective.

far from adequate. It was misleading and tended to

breed rituals; it gave a false sense of achievement

and even complacency that one was doing everything

one had to do in community health . Wide gaps

in knowledge, information and strategies were there

waiting to be discovered. These were the growth

points one had to look for very carefully. This

realisation underlines the need to develop experi

ences, tin sights and knowledge which is relevant

and pertinent to Indian situation. Both social

sciences as they relate to health problems and natu

ral sciences have to develop further so that com

munity health ceases to be underdeveloped and

primitive. More painful and frustrating is that

even some proponents of the second trend are also

equally unattentive to this perception.

Tire

wateright compartmentalisation

into

political activists and health activists can

help. Competence in health sciences

no longer help.

1

is essential, but

assimilation of egalitarian

values and understanding of political reality are

crucial to undertake such “field research” condu

cive for the health of the masses. ’Most of (the

MFC members have internalised the latter; ques

tion is to fill up the deficiency in the former1 one.

But MFC members are small in number.

Most of them are already engaged in traditional

project work, political activities, campaigns for

educating masses, teaching and research in establi

shed institutions, etc. according to their aptitudes

and priorities. Would such a shift: impinge: upon

personal freedom and preferences?

Possible Tasks

■f

t

MFC lias realised the simplistic nature and

sloganism of various technological and social

interventions in vogue. It is not only not enough

to speak about shift from individual to community

diagnosis, but to understand and decipher intricate

webwork of the individual as a member of a family,

of much larger social groups to which he belongs

through kinship, residence, occupation, religion,

beliefs, etc. and conditions of his life, his work,

his economic and social placement and culture, his

physical and biological environment. Furthermore

refinement and differentiation in relation tjo each

disease process. Thus the real problem does not lie

in actual activities but lies in the theoretical under

standing of the complexly of the disease process in

the community that inform these activities. It( is

through continuing analysis and actions of various

groups on at least some of these1 problems in simi

lar perspective! that relevant, durable and realistic

pieces of knowledge are going tio be built.

We have been busy struggling with ourselves

and for various other factors, we could not interact

with medical students, socially concerned non

medical friends and consumers of health care

adequately. If we refer to the deliberations of the

second annual meet at Hoshangahad it dileneated

guidelines for action programmes quite well. Why

could we not persue it? Can we learn from positive

experiences from KSSP and negative experiences of

other organizations? Is it just a lack of infrastructure

and full time worker or adhocism responsible for

our failures?

Is there a critical mass of socially concerned

physicians! today who are competent enough to

build tip this knowledge: Does the ‘health care

mix’ aped by voluntary groups have rigour and

strength to stand the “scientific scrutiny”? Can

voluntary groups face, with their own observation

and evidences, a tough and thorough-going “objec

tive” criticism made by sympathetic academicians?

Could our priority be to evolve a (collective voice

known not only for its honesty and commitment

to tre cause of the poor; but also respected for its

ability and scientific rigour; not only among like

minded people but also among the professional

Conclusion

I have not tried to reflect on all the aspects of

MFC.( M|any things (have been left out; jljikje i^s

commendable achievements, its democratic and

egalitarian ways of working, place and role of MFC

bullentin, interaction with various groups and

individuals, details of various projects, campaign

and workshops, managing on low budgets function(Continued on page 10)

3

Looking Ahead...

Anant Phadke

would be — it does not show the process through

which the solution it offers can be brought into

practice. MFC can claim that it can show the

process of change which MFC wants to bring

about and that MFC itself constitutes a part of the

process/ Whatever may be our position, we can't

ignore this report. To be sure, there are many

aspects of this report with which MFC agrees.

This report has thus raised the level of debate,

If we are to find out how MFC can develop

further in the future, we should try to understand

the factors that affect the growth and develop

ment of MFC. These factors lie both within MFC

and outside it.

Let us start with the social fac

tors outside MFC.

The socio-economic condition in India is

turning from bad to worse. The plight of the

ordinary people is increasing, so is their opposi

tion to their oppressors. A section of the white

collar intellectuals, students, are bound to be

affected by this and some of them are'bound to

seek alternatives.

This sensitive, .humanitarian,

democratic layer from within the intelligentsia

constitutes a potential for MFC. All of us con

tinue to meet many sensitive, socially-conscious

medicos for whom a group like MFC offers a plat

form which they are happy to know about and

which they would like to join. MFC would grow

if it can approach, such individuals. If there is

a social movement amongst the intelligentsia on

any issue concerning human values, justice, we

can even hope to get a large influx of newcomers.

The original group of MFC was a product of the

Jay Prakashwadi movement. There is no such

movement on the horizon now, but to be sure it

is/ound to emerge, perhaps in a different form.

The social conditions that gave rise to it still con

tinue to dominate our lives. Today the intelli

gentsia seems to have resigned to whatever is

happening. This cynical aloofness is a counter

acting force which affects the growth of groups

like MFC. Nevertheless, on the whole, the situa

tion contains a lot of potential for the growth of

groups like MFC. But along with the growth of

general dissatisfaction amongst the people, the

challenges in front of a group like MFC have also

grown. What are these challenges?

and has set a reference point for discussion and

action. It is no more sufficient for groups like MFC

to discuss and act at the same level as was done

before the publication of this strategic report.

In the non-Government sector, the achieve

ments of some of the pathbreaking voluntary

Health Projects are now well known. What do

groups like MFC have to ^ay about these projects,

their achievements and /limitation, their relation

ship with the goal that we want to achieve? A

number of international agencies are fostering the

methodology as being attempted by these projects

and this adds to their importance.

Thirdly within the medical field, a number

of oppositional movements have grown in last

10 years of Junior Doctors, paramedics and Govt.

Medical Officers for better pay and better work

ing conditions; of consumers against misuse of

drugs .................

How groups like MFC should

relate to these movements

Groups like MFC cannot grow and develop

to any substantial extent unless such new deve

lopments are analysed properly and a standpoint

taken in theory and in practice. Does Medico

Friend Circle have the Resources-theoretical and

practical — to successfully deal with the new

challenges and hence grow into a trend which can

make a dent on the national scene? To answer

this question, let us locate the strengths and weak

nesses of MFC. MFC has been able to survive

and grow against all odds. (Compare MFC with

similar groups.) MFC has not survived by degene

rating into a lifeless institution. (Such institutions

continue only because some funding source is

re,ady to "keep” them.) MFC has also not degene

rated into a political sect with no basis in social

movements. To survive as a lively group is an

achievement for group of medicos which is funda

mentally opposed to the existing medical profes

sion and the existing system of medical care.

Secondly MFC is unique in that though most of

The publication of the report — "Health for

All : An alternative strategy” has posed a concrete

problem. After the publication of this prestigious

report (prepared by the collaboration of ICMR —

ICSSR with the help of a number of renowned

persons in the field of health-care) groups like

MFC have to take/ concrete position about what

is in our view, wrong with the existing system of

medical care and what is the alternative. Is oqr

analysis and solution any different from what Mas

been described in this report? If yes, in what way

and why? One of the criticisms of this/7report

4

4

4

MFC

A/P J90- Ici

(Continued from page 3)

ing without paid full time personnel, tetc. Inspite

of all its limitations and failures, MFC has ’created

a lot of hopes and expectations from varied quar

ters. Pertinent question is whether MFC can

collectively show resilience and 'tenacity to meet

the challenge of examining the process and progress

of its functioning continuously in the light of fresh

experiences and knowledge without slipping into

high profile global fashions, slogans and cliches.

MFC could show a change in emphasis after

a long debate on ‘MFC which way to go' from

achieving socio-economic change to evloving a

pattern of medical education and methodology of

health care relevant to Indian needs and conditions

as a part of broader efforts to improve all aspecst of

society for a better life, more humane and just in

contents and purposes. MFC bulletin could also

show a shift from merely paralysing critiqufe of

micro level issues to examination of various micro

level alternatives and interventions. Annual meets

also tried to respond to issues- like women land

health, medical education, etc. MFC also respon

ded to live and emergent issues like reservation for

sieats in medical colleges for the scheduled tribes

and castes.

These experiences make one feel

confident that MFC has the potential to respond to

relevant issues in a mature and courageous way.

i

COMMOi'^ITY HEALTH FORUM

No. 367, ‘Srinivasa Nilaya*, Jakkasandra, I Main Road,

I Block, Koramangala, Bangalore - 560 034.

30th June, 1992.

Dear

Greetings from Community Health Forum 1

This is to inform you of the next CQHO Forum meeting ?

Date

11th July 1992 (Saturday)

Time

2«00 p.m.

Venue

Topic

s

s

to

4.30 p.m.

Ashirvad,

30, St. Mark’s Road,

Bangalore - 560 001„

iPhone - Ashirvad

C.H^Forum

- 210154

- 531518)

•‘COMMITY HEALTH GET J,.11

You are aware that it is a year since the C.H.C. has registered

as " Seciety for Community Health Awareness, Research and Action”.

Members of C.H.C. will be briefly reviewing the past activities,

sharing with you its concerns and initiatives, while putting up

plans for the future.

As members of the COH. Forum and friends of C.H.C. we EARNESTLY

request your participation, ideas and viewpoints to enable a common

initiative towards Community Health.

Do mark this date/time in your schedules and looking forward to

our meeting.

With regards and Best Wishes,

Yours sincerely,

for CCPMJNITY. HEALTH FORUM,

>

Mf' £ l<

Looking Ahead...

Anant Phadke

would be — it does not show the process through

which the solution it offers can be brought into

practice. MFC can claim that it can show the

process of change which MFC wants to bring

about and that MFC itself constitutes a part of the

process. Whatever may be our position, we can't

ignore this report. To be sure, there are many

aspects of this report with which MFC agrees.

This report has thus raised the level of debate,

and has set a reference point for discussion and

action. It is no more sufficient for groups like MFC

to discuss and act at the same level as was done

before the publication of this strategic report.

If we are to find out how MFC can develop

further in the future, we should try to understand

the factors that affect the growth and develop

ment of MFC. These factors lie both within MFC

and outside it.

Let us start with the social fac

tors outside MFC.

The socio economic condition in India is

turning from bad to worse. The plight of the

ordinary people is increasing, so is their opposi

tion to their oppressors. A section of the white

collar intellectuals, students, are bound to be

affected by this and some of them are bound to

seek alternatives. This sensitive, humanitarian,

democratic layer from within the intelligentsia

constitutes a potential for MFC. All of us con

tinue to meet many sensitive, socially-conscious

medicos for whom a group like MFC offers a plat

form which they are happy to know about and

which they would like to join. MFC would grow

if it can approach such individuals. If there is

a social movement amongst the intelligentsia on

any issue concerning human values, justice, we

can even hope to get a large influx of newcomers.

The original group of MFC was a product of the

Jay Prakashwadi movement. There is no such

movement on the horizon now, but to be sure it

is bound to emerge, perhaps in a different form.

The social conditions that gave rise to it still con

tinue to dominate our lives. Today the intelli

gentsia seems to have resigned to whatever is

happening. This cynical aloofness is a counter

acting force which affects the growth of groups

like MFC. Nevertheless, on the whole, the situa

tion contains a lot of potential for the growth of

groups like MFC. But along with the growth of

general dissatisfaction amongst the people, the

challenges in front of a group like MFC have also

grown. What are these challenges?

In the non-Government sector, the achieve

ments of some of the pathbreaking voluntary

Health Projects are now well known. What do

groups like MFC have to say about these projects,

their achievements and limitation, their relation

ship with the goal that we want to achieve? A

number of international agencies are fostering the

methodology as being attempted by these projects

and this adds to their importance.

Thirdly within the medical field, a number

of oppositional movements have grown in last

10 years of Junior Doctors, paramedics and Govt.

Medical Officers for better pay and better work

ing conditions; of consumers against misuse of

drugs .................. How groups like MFC should

relate to these movements

Groups like MFC cannot grow and develop

to any substantial extent unless such new deve

lopments are analysed properly and a standpoint

taken in theory and in practice. Does Medico

Friend Circle have the resources-theoretical and

practical — to successfully deal with the new

challenges and hence grow into a trend which can

make a dent on the national scene? To answer

this question, let us locate the strengths and weak

nesses of MFC. MFC has been able to survive

and grow against all odds. (Compare MFC with

similar groups.) MFC has not survived by degene

rating into a lifeless institution. (Such institutions

continue only because some funding source is

ready to "keep" them.) MFC has also not degene

rated into a political sect with no basis in social

movements. To survive as a lively group is an

achievement for group of medicos which is funda

mentally opposed to the existing medical profes

sion and the existing system of medical care.

Secondly MFC is unique in that though most of

The publication of the report — "Health for

All : An alternative strategy" has posed a concrete

problem. After the publication of this prestigious

report (prepared by the collaboration of ICMR —

1CSSR with the help of a number of renowned

persons in the field of health-care) groups like

MFC have to take a concrete position about what

is in our view, wrong with the existing system of

medical care and what is the alternative. Is our

analysis and solution any different from what has

been described in this report? If yes, in what way

and why? One of the criticisms of this report

4

f\Jv

f - Wv

lDD-1 Cl,

1^4-

I (i 0

the leading members of MFC are politically cons

cious, they have enough of healthy, non-sectarian,

democratic approach to allow medicos from diffe

rent political leanings to come together, debate,

criticise each other, learn from each other and

develop into a tolerant, mature group. It must,

however, be noted that the "friendly" atmosphere

in MFC is partly because there is not much at

stake. If MFC squarely faces the problems men

tioned above, starts growing as a formidable cur

rent on the national plane, the friendly atmos

phere is bound to be affected atleast to a certain

extent. But the tradition, we have set up will help

us in challenging times. The tradition of respect

ing other's viewpoint, of mutual trust, openmindedness has been our asset. To be sure some

sectarian mistakes have been made of because of

which some people got alienated. But many have

come back and on the whole very few have drop

ped out with sharp discontent. (The core-group

of MFC sometimes gives an impression of an arro

gant, radical, intellectual clique involved within

itself. But this is only a cursory impression — even

that should changes and it is not at all the true

nature of this group.)

The third positive asset of MFC is the ten

dency in MFC to examine things in a critical the

oretical perspective, on a principled basis yet in

a way that would be relevant to the problems in

the actual field. Since most of the leading mem

bers are actually working at the grass-root level,

this critical questioning outlook acquires a special

down-to-earth practical connotation.

This has

earned MFC seme good name (as well as bad

name amongst those who don't like such ques

tioning.)

But the theoretical development in MFC has

been quite slow. It is only recently that things

have really begun to move. The tendency in MFC

to be self-complacent and self-congratulating has

more or less been replaced by a serious concern

to study, work upon and develop our understand

ing.

But still it would take a lot more effort to

systematically develop position on the problems

mentioned earlier. There does not seem to be

adequate realisation in most of us that MFC must

answer these and such problems if it has to make a

dent on the national level. A sense of urgency, requ

ired in view of MFC's lagging ebhind as of today,

is by and large absent. There is a concern for

developing our understanding; but not in relation

to the challenge posed by the events happening

around but as a general concern for theoretical

development.

Things are bad when we come to the ques

tion of making a co-ordinated effort to make an

impact on a national level by forging, propagating

an alternative viewpoint. Most leading members

of MFC are quite involved in their local work.

Most of us have not been able to devote much

time and energy for MFC's organizational work.

Unless the leading members of MFC replan their

local work in such a way that they spend much

more time for MFC's organizational work, unless

more fresh blood comes in, MFC will not be able

to face at all the challenge posed to her by the

developments in last few years. Unfortunately not

Some are even

many MFC members see this.

content with the running of the Bulletin and the

Annual Meet. We must realize that even mere

continuation at the existing level is financially

becoming more and more difficult due to price-rise.

The financial deficit is increasing very fast. Unless

we have atleast 1,000 subscribers (compared to

about 400 to-day) the deficit would become

unmanageable next year (even this year.) There

are more than 2 lacs MBBS doctors in India, (to

take one yardstick of assessing the potential for

MFC to grow) and even one per cent of this

becomes more than two thousand.

MFC is

unknown to many of those who would readily

become its members. We should have reached at

least this section. But that involves a change in

the attitude of many leading MFC members

towards MFC and hence a re-planning of their

priorities in practice. Are we really serious about

forging an alternative, making a dent on current

opinion in India about medical care? Shall we

critically study, try to develop and practice communty medicine much more seriously? Shall we

study and understand in a much more concerned

manner the history, development of social move

ments, social changes in India and abroad? In one

word, shall we get rid of amateurism in us? The

answer to these questions will decide whether MFC

can play its role in the "fundamental socio-econo

mic change'' that MFC wants to align with.

□’

I

5

108

medico friend

circle

bulletin

DECEMBER

1984

Discussing Tuberculosis Control-Why?

— Anant Phadke, Pune

(In the coming Xlth Annual Meet of the Medico

Friend Circle at Bangalore, we would be discussing

various issues concerning tuberculosis control in

India. The question is so vast that it is impossible

to have any useful discussion unless we define the

focus of the discussion. In my view, the purpose of

discussing any issue in mfc needs to be clearly

thought of and agreed upon. In this note, I would

argue what in my view would be the appropriate

purpose of the discussion at the mfc annual meet.

This note would inevitably involve a discussion on

the role of mfc.)

Role of discussion at the annual meet

Let me first quickly put forth a consensus that

we had reached about the general role of the dis

cussion at the annual1 meet. It was thought that

there is a definite section within medicos and non

medicos in India who already have a perspective

similar to that of mfc or who could come to mfc, if

there is adequate contact and dialogue. Different

individuals in this section are more interested in

specific aspects of the health system in India. If mfc

takes up various issues in different meetings, then

those individuals with

specific interdsts in these

subjects would come closer to mfc and may join us.

Secondly such discussions would help us, the mfc

members, to enrich our knowledge and perspective

of the health problems in India through well planned

discussions with the help of resource persons out

side mfc; and mfc in turn would hopefully make some

impact on the new participants during the course of

these discussions. Fine enought But all this does not

specify what specific kind of knowledge we want to

gain and generate through these discussions; whether

and in what way would the discussions be different

from the discussions in the academic or established

circles of community health.

Specificity of mfc

To answer this question, let us go back to the

origins of mfc, the kind of discussions we have had so

far and the debate on ‘mfc — which way to go’

carried through the pages of the bulletin and reprinted

in our anthology — HEALTH CARE WHICH WAY

TO GO? I would also like to remind readers of the

Centenary issue of the mfc bulletin No. 100-101

(May-June 1984) where the contributors had taken

a somewhat critical overview of what the mfc has

achieved, not achieved and what challenges we face

today. It is not possible to go through the history

of mfc in this note. I would only point out two specific

characteristics of mfc which are reflected in all these

writings. One, its concern for Social Revolution. At

least the core members of mfc have been very con

cerned about this and hence the articles in mfc bulle

tin have been quite critical about the existing health

system and the debate ‘mfc which way to go?” was

centered around how mfc could contribute to funda

mental socio-economic-political

(S-E-P as Abhay

Bang had put it then) change. The second characte

ristic has been the critical and questioning attitude

of mfc members:

critical of new ‘solutions’/strategies put for

ward by the establishment and the community

health enthusiasts (this critical outlook partly

reflects the grass root village level at which

many mfc members work)

critical (admittedly to a lesser extent) about

mfc’s achievement and

of late, critical about the existing prescrip

tions of community medicine.

*

False and genuine limitations

are genuine ones is something that needs to

be worked out concretely and is in a way a matter

of judgement also, but to be sure, there is such a

difference. Secondly the established value system

does not completely disappear in such project work

and the problem of poverty, social and educational

backwardness, bureaucracy etc., etc., would continue

to affect health work in such a project, though in a

mitigated and different form. But the direction of

where we want to go would be clear.

My plea is, let us be more conscious about our

' specific character and. shape our discussions in the

coming annual meet accordingly. What does this

mean concretely? For example, let us look critically

at the argument that ‘since India is a poor country

Inj. streptomycin should be reserved only for sputum

positive cases and only the two drug regimen of

Isonex plus thiacetazone be given to sputrum nega

tive cases.’ We shout’d question this argument and

ask ‘Is Indian economy so backward today that it

cannot really afford to give streptomycin to all the

cases of tuberculosis?’ Today, the existing system

squanders resources on useless activities and keeps

a smaller share than what is possible and necessary

for health work. Even within health, resource utilisa

tion is in favour of the medical establishment and the

well-to-do. In the case of drug production, for exam

ple, out of a total of about Rs. 1200 crores of drugs

used annually in India, it is estimated that only about

Rs. 350 crores of drugs are essential and rational.

The rest, though they yield higher profits for drug

companies, are useless and irrational. If these re

sources are utilised properly why can’t all those who

need antitubercular treatment get proper treatment?

Is Indian economy really so backward that radio

graphic facilities cannot be extended more to help the

diagnosis of tuberculosis and other conditions? Why

should mfc accept the false limitations imposed by

the existing system and try to work out solutions

within these false limitations?

A question may be posed: What is the point in

trying to create ideal islands of project work when

tney are going to remain islands, when the strategy

is not going to be generalized?’ Firstly I am not

talking about ‘ideal’’ situations which have no basis

in today’s reality. One is talking about rejecting only

false limitations. Now it is true that even this cannot

be generalised within this system (obviously!) and

our alternative can only flower in a different, better

social system. That is why mfc members should work

within the context of and with the cooperation of

social movements; forces which are really aiming at

a different and better society. This is how we as

medicos can help the social revolution which was the

original and is the specific inspiration of mfc. Instead

of working within the existing system and hence help

ing it, legitimising it, why not work outside or on the

system and help those social' movements which are

aiming at changing the system itself?

There is a practical advantage in working with

such social movements. If a project work is under

taken in an area where such a broad movement to

wards fundamental social change is taking place,

people’s participation, one of the most important

requirements of good community health work (and

which is generally lacking in many projects run

mainly on the basis of funds) can become a reality

and the entire atmosphere is quite different from the

usual one of apathy, lack of faith, lack of commit

ment and too much bureaucracy. In such places, one

can concentrate on the real problems of health work

and also obtain people’s cooperation and participa

tion, required to solve them. I have deliberately used

the general terms social revolution and social move

ments, because concretely which are such movements

is something which individual members have to decide

on their own. Ideologically and politically mfc is not

very homogenous and different individuals have diffe

rent opinions. But one thing is certain, all of us want

a fundamental socio-economic change even if the exact

character of this change is a matter of debate.

My plea is that when we discuss the problem

of tuberculosis or any other problem, let us discuss

it with a view to the social revolution that alone would

be able to create conditions for a healthy society and

a healthy medical system.

We all know very well that India is both econo

mically and socially backward and even after a social

revolution resources are not going to develop at such

a rate as to make all desirable facilities available in

the immediate future. We would, therefore, have to

work out solutions within the constraints of limited

resources. But over and above these real constraints,

the existing system has imposed its own constraints

like — malutilisation of resources for the benefit of

a few; bureaucratic callousness of doctors and other

health personnel; curative oriented training; corrup

tion and commercialization in medical practice;

political interference by vested interests etc., etc. All

these together make it almost impossible for a scienti

fic strategy to be successfully implemented. In

these circumstances should we try to suggest methods

of improving the existing state of affairs a little more

by accepting all the false limitations of this system?

Towards a better medical and social system

Instead of falling into their trap under the name

of ‘Practical difficulties’, and suggesting improve

ments to those who are neither particularly

willing nor capable of improving the existing state of

affairs (remember what happened to the reports of

numerous expert committees) why not expose them?

Why not concentrate on evolving a people oriented

scientific strategy in our own projects and other

activities? Such an approach would reject false limita

tions and try to work within genuine limitations.

Firstly which are false limitations and which

Tall talk?

It may be thought all this is high flown, tall talk'