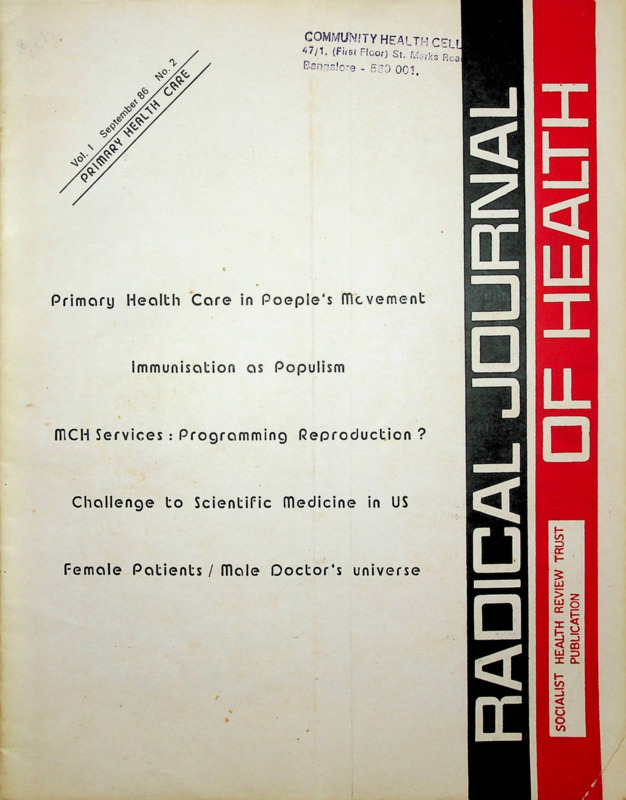

Radical Journal of Health 1986 Vol. 1, No. 2, Sep.: Primary Health Care

Item

- Title

- Radical Journal of Health 1986 Vol. 1, No. 2, Sep.: Primary Health Care

- Date

- September 1986

- Description

-

Primary health care in people’s movement

Immunisation as populism

MCH Services: programming reproduction?

Challenge to scientific medicine in US

Female patients / male doctor’s universe - extracted text

-

COMMUHfTY HEALTH CEl I

'■•7/1. (First Floor) St. Mjrks Roa

Bangalore - 530 OCI,

Primary Health Care in People's movement

immunisation as Populism

mCH Services : Programming Reproduction ?

Challenge to Scientific medicine in US

Female Patients / male Doctor's universe

Yol I

Sept 1986

No. 2

HEALTH

CARE

PRIMARY

41

Editorial Perspective

Working Editors :

Amar Jesani, Manisha Gupte,

Padma Prakash, Ravi Duggal

Editorial Collective :

Ramana Dhara, Vimal Balasubrahmanyan (AP),

Imrana

Quadeer, Sathyamala C (Delhi),

Dhruv Mankad (Karnataka), Binayak Sen,

Mira

Sadgopal

(M P),

Anant

Phadke,

Anjum Rajabali, Bharat Patankar, Jean D'Cunha,

Srilatha Batliwala (Maharashtra) Amar Singh

Azad (Punjab), Smarajit Jana and Sujit Das

(West Bengal)

Editorial Correspondence :

Radical Journal of Health

C/o 19 June Blossom Society,

60 A, Pali Road, Bandra (West)

Bombay - 400 050 India

Printed and Published by

Dr. Amar Jesani for

Socialist Health Review Trust from C-6 Balaka

Swastik Park, Chembur Bombay 400 071

POLITICS OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

Imrana Quadeer

43

SOCIAL DIALECTICS OF PRIMARY HEALTH

Guy Poitevin

52

IMMUNISATION AS POPULATION : A REPORT

Asha Vohuman

55

PROGRAMMING REPRODUCTION ?

MATERNAL HEALTH SERVICES

Manisha Gupte

59

THE HOLISTIC ALTERNATIVE TO SCIENTIFIC

MEDICINE: HISTORY AND ANALYSIS

Howard S Berliner and J Warren Salmon

66

UPDATE - News and Notes

Printed at :

69

Omega Printers, 316, Dr. S.P. Mukherjee Road,

Belgaum 590 001 Karnataka

FEMALE PATIENTS VERSUS

MALE DOCTORS' UNIVERSE

Jytte Willadsen

Annual Subscription

Rates

:

Rs. 30/- for individuals

Rs. 45/- for institutions

Rs. 500/- life subscription individual

US dollars 20 for the US, Europe and Japan

US dollars 15 for other countries

We have special rates for developing

countries.

SINGLE COPY : Rs. 8/(All remittances to be made out in favour of

Radical Journal of Health. Add Rs. 5/- on

outstation cheques)

73

Dialogue

ORGANISING DOCTORS: A DIFFERENCE IN

APPROACH Sujit Das

LIGHT ON BLIND SPOTS: UN Jagoo

ECT AND DRUG THERAPY: IS THERE AN

ALTERNATIVE : A R

The views expressed in the signed articles do

not necessarily reflect the views of the editors.

Editorial Perspective

Politics of Primary Health Care

SINCE the seventies, in many national and international

circuits of health bureaucracies, Primary Health Care (PHC)

has become a panacea for all the evils of the poorer nations.

The WHO has projected it with all its convictions and the

member nations have accepted, it with equal vigour.

According to the Alma Ata declaration.'

Primary Health Care is essentia! health care based on practical, scienti

fically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made

universally accessible to individuals and families in the community

through their full participation and at a cost that the community and

country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development

in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination. It forms an integral

part both of the country’s health system of which it is the central

function and main focus, and of the overall social and economic

development of the community.

Today when this strategy has been accepted by such a large

number of countries, there is a need to examine its potential

strengths and weaknesses.

The idea that health is closely related to people’s living

and working conditions and that it is an outcome of their

socio-economic environment was vocalised by men in

different fields like John Snow, Engels and later Virchow in

the West. It manifested itself in the sanitary movement of

the 19th century. In India and other parts of the East it had

much deeper roots, visible in the method of ancient medical

science itself and in the cultures of Harappa and Mohenjodaro. In India during the struggle for Independence, a

demand for comprehensive health care was a part of the

national movement. Why then this sudden fervour now for

projecting PHC as a new concept by international and

national official circles?

To understand the politics of PHC one has to understand

the role that UN and WHO have played in the overall politics

of the world. Always supporting the interests of the

imperialist nations, these organisations have used the liberal

tools of aid, support and providing consultancy to diffuse,

control and direct crisis situations. The effort to develop an

alternative World Economic Order in the 70s was one such

spurious exercise and as a part of it, was proposed the notion

of alternative health care for the third world.

The motives behind it were to check impending destruc

tive and costly reactions from and within third world nations

whose poverty, disease and squalor were becoming threats

to stability. PHC was the baby of the liberals in the

imperialist camp and WHO projected it as the solution to

poor nations’ health problems—with full promise of help

and support, but a clear understanding that the local political

structures alone will give shape to the implementation of

Primary Health Care! Such an international strategy which

offers free help without any political price is obviously

seeking change in health situation with or without the

political will of the local government. It is interesting that

the international terms of trade are in total contradiction to

this attitude. Even though one knows that some liberals have

their hearts in the right places, this conflict in international

strategy needs serious analysis to understand the reasons for

this special concession to health.

September 1986

At the national level the concept of PHC acquires multiple

dimensions. Given the particular hue of the government, the

implications have varied from Africa to south cast Asia and

Eastern Mediterranean regions. The issue is what use docs

a national government make of the concept? Does it use it

as the concept is presented by the Alma Ata declaration and

make it a part of its effort to develop an integrated strategy

for the betterment of its people, as in Angola, Tanzania and

Mozambique or does it allow the concept to degenerate into

a slogan behind which the same old strategies with some new

features continue to be implemented—at a faster rate perhaps

with the additional inputs from the international fund

givers—as in India and Pakistan?

A grasp on the national politics of PHC requires an.

understanding of the country’s socio-economic and political

structure and the nature of its government and health service.

structures. Only such an understanding allows one to assess

the potentialities or limitations of the system to achieve PHC.

An example of the interplay between PHC and politics is

the level at which it is integrated into the planning process

of a country. Thus, the Chinese and Vietnamese incorporated

PHC in the very process of national planning right from the

period of their independence without giving it a name. In

contrast, India made so much fuss and then relegated PHC

to the care of the health ministry while the overall planning

processes took its own directions. Yet another example is the

implementation and outcome of programmes introduced

under the banner of PHC. These programmes which may

have a potential of providing much needed services are over

taken by the local power elite through their links with the

health and administrative bureaucracies. The nature of the

latter thus becomes the primary determinant of the outcome.

The Community Health Guides scheme and the drinking

water supply through borehole hand pumps in India arc two

such examples.

Another dimension of the PHC efforts at the national level

is the setting of priorities and the selection of technology.

In India despite the official acceptance of implementing PHC

by 2000 AD, the heavy emphasis on urban-based services and

curative approach in rural areas continues with heavy

dependence on expensive equipment and drugs. The drug

policy needed to provide PHC is yet to be formulated. Can

issues of priorities and technology be then isolated from

politics? A simple but revealing example is the supply of

“electrolyte” packets in the Community Health Guides’ kits!

Does it not show links between the health administrators and

the drug industry who know that addition of so many salts

to the basic mixture only increases cost and not effectivity?

If the concept of PHC is getting distorted in the hands

of the not-so-democratic government and is becoming a4ool

for creating two types of services, one for the rich and the-'

other for the poor, should it be criticised, rejected, accepted

as an unavoidable distortion or used to broaden the base of

democratic movements? These are some of the questions

which need to be answered by those who are working in the

41

interest of people’s health. Can PHC as a concept become

an inspiration for those involved in people’s struggle for their

rights? If PHC is an outcome of total development then it

should be. And what have people’s democratic and left

movements done about it?

There are many small or regional projects experimenting

with implementation of primary health care. What is the role

of such projects in focussing upon the issue of PHC or in

diluting it?

In academic circles, in the name of professionalism and

the need to achieve results, a concept of “selective PHC”

has been circulated which means let us not talk of compre

hensive development but do what we can without disturbing

the existing balances. This is attractive to those who would

like to go back to singing praises to powers of technology

and managerial competence. There is need to examine such

concepts threadbare to show their reactionary ideology as

well as non-feasibility.

Are there any lessons that we can draw from the ex

periences of the socialist countries which have tried to

provide health care not in isolation, but as a part of their

total developmental processes? These are the major questions

which need to be addressed when one is dealing with the

bipronged weapon of Primary Health Care.

and perspective of the maternal and child health programme

and points out that without a questioning of the role of the

women in society, any such programme would be ineffective.

Asha Vohuman reports on the mass immunisation pro

gramme which was launched with such fanfare in Bombay

in 1983, not so much because of its potential impact on the

health of the children but because the minister in charge

needed a visibly successful campaign to consolidate her

political gains. The reprinted article from International

Journal of Health Services provides a historical background

of the concept of public health and raises some questions

about holistic health alternatives emerging in the US. And

in the non-theme section we have Jytte Willadsen discussing

the question of the sexist bias in medicine. As a doctor herself

she also touches upon the problems encountered in bring

ing about any changes in the very male oriented medical

establishment in Denmark.

We have as usual the Update and Dialogue sections. Sujit

Das continues the discussion on the role of doctors; Ulhas

Jajoo responds to Anant Phadke’s review of his book When

the Search Began (RJH, I: I) and AS questions if drug

therapy in psychiatric problems does not have a place in the

present socio-political context.

This issue examines some of the problems raised in the •

editorial. Guy Poitevin describes his experiences in taking

up health issues as a part of larger movement for socio

economic change. Manisha Gupte comments on the ideology

Centre for Community Health and Social Medicine

Jawaharlal Nehru University

New Mehrauli Road

New Delhi.

inirana qadeer

XIII Annual Meet of MFC

Medico Friend Circle will hold its XIII Annual Meet at Seva Mandir Training Centre, Kaya (near Udaipur),

Rajasthan, on 26lh and 27th of January 1987.

The theme chosen for discussion this time is “Family Planning in India: Theoretical Assumptions, Implementation

and Alternatives”. Family Planning has generally been considered an important part of Primary Health Care, but over

the past two decades, it has come to occupy a key place amongst the country’s development strategies. Is its elevation to

the level of a panacea, for the problems facing the people, based on well examined theoretical assumptions? What effects

has the policy of incentives and coercion had on the performance of other health programmes? Out of the existing contra

ceptive methods which is the least harmful? Do some of these methods need to be rejected outright? Are there safer alter

natives? These are some of the issues to be discussed at the Meet.

As usual there will be no reading of papers. Background papers on related topics will be circulated beforehand to facilitate

discussions. They include: (a) Problem of population versus resources (b) Theoretical assumption of FP policy in China

(c) Critical examination of the FP policy in the context of the child survival hypothesis (d) Comparative analysis of the

dangers of pregnancy and contraception (e) Women as the main targets of FP policy (f) The paradox of higher FP perfor

mance in tribal areas (g) Incentives and coercions—effects on Primary Health Care (h) Pattern of resource allocation in

bur Five Year Plans (i) Evaluation of the existing FP methods 0) Natural Family Planning methods as safer alternatives.

We invite you to attend the Meet and share your views and experiences. We also invite you to write background papers

on any other topic to the theme. Your note/paper should reach the Convenor’s office by the 31st November.

Participants are as usual expected to pay for their own travel. Simple boarding and lodging facilities will be available

at the venue, on a payment of Rs. 20/- per day per person. We charge a small registration fee to cover the cost of the

cyclostyled background papers. Return reservation facilities are also available. If you wish to attend, please write to:

Dhruv Mankad, Convenor, Medico friend Circle, 1877, Joshi Galli, Nipani-591 237. We will then send you the venue

details and background papers.

42

Radical Journal of Health

Social Dialectics of Primary Health

guy poitevin

This article presents some socio-psychological observations and conclusions drawn from a social study made

of a limited voluntary health programme undertaken by a sinall NGO in remote rural areas of Maharashtra (Sahyadri

Range). This qualitative study is concerned with health as a social process. Health practices are examined as

components of over-all socio-cultural dynamics and the foundations of a people's health movement sought within

the context of a wider attempt of socio-political awakening and people's organisation.

SEVERAL voices raise to draw our attention on primary health status, the planning of alternative or integrated health

health issues as components of local socio-cultural dynamics. 'services among deprived rural population and the related

This perception prevails, for instances, as a conclusion of welfare, educational or developmental issues, in a more or

the assessment of the working of the Rural Health Scheme less static way. Health is examined here as a social process

made by the Population Research Centre of the Institute of from within a marginalised population, v/z., as a dimension

Economic Growth: “His (Community Health Volunteer, of an overall dynamics of socio-cultural and socio-political

CHV) role as a public health worker is more social than awakening and people’s organisation. The study is concerned

medical. It would require of him to create health con with the conditions of a possibility-of an effort of health

sciousness within the community and to prepare and organise by the people which actually cares for all, bas^d on a critical

the community effort to carry out all the necessary steps of appraisal by those concerned -i e those deprived of health

improving sanitation within the settlement, cleansing up the care facilities—of the present health system and motivated

surrounding areas and imparting health education to all its by a will to try out self-reliant ways. This case study is partial

members. This work within the community is in fact the contribution towards answering some of the following ques

fundation upon which the whole health care delivery system tions: the need for a strategy for enlisting community par

must rest” (Bose A, 1983: 53-80). P B Desai concludes a ticipation, the task of generating social health awareness,

general evaluation of the CHV Scheme in India with the securing of the cooperation of women more than of men,

following assessment: “The most crucial shortcomings of this generating appropriate health practices, organising collective

kind of approach is the failure to upgrade the capabilities health actions, etc. We may even piously wish or dream that

’of individuals, families and communities to take upon

“if we succeed in organising the community for giving to

.themselves the responsibility of attaining and maintaining itself-a primary health care system of its own choice, it may

conditions for healthy living within their jurisdictions. In • become all the more practicable to carry forward this process

•other words, the central issue of the promotion of self-care of self-reliant development into all fields of social and

’is left unresolved” (1983: 7). He then stresses the point that economic progress” (Desai, 1983: 8). But the crucial ques

the definition of the objectives drawn in the Alma Ata tion remains unanswered beyond the many evaluations of

•Declaration (1978) to resolve this central issue is ‘holistic’ in the shortcomings and failures of the CHV Scheme: what does

nature, as t^eir formulation insists on a full community parti it mean methodologically to “organise the community” for

cipation and a spirit of self-reliance and self-determination enabling it to wish, to conceive, to experiment, to chalk out

(WHO-UNICEF, 1978: 3), and the “task of delivering health and to give itself a health system appropriate to its concrete

•care must begin with this non-medical, social endeavour of needs. What does this mean in terms of strategies of social

achieving the necessary social transformation at the grassroot action?

level.”

Primary health care as the subject of social science research.

If such is the case, once we have acknowledged and really should therefore be examined and evaluated by focusing on

perceived the social role of the CHV and measured the ’ the dialectical relation obtaining between the level of health

import of the ‘holistic’ perspective with which we should conciousness and the forms of collective organisation on

approach primary health issues, a corollary immediately health issues on the one hand, and on the other, the local

follows, that health development schemes should seek the socio-cultural, administrative and power structures, including

help and the critical insights of social scientists, anthro those of the public health care system itself. If health status

pologists and psychologists. And this is all the more is rightly considered as an index of social development, health

necessary when we are concerned with provision of primary consciousness—as expressed in relevant renewed perceptions

health education and care based on efforts of self-reliance and representations and consequent forms of collective

among the most underdeveloped sections of the rural popula action—should be rightly considered as a component and

tion, whether these efforts be undertaken by government an index of the socio-cultural, and politcal awakening of a

agencies or NGOs. If these efforts are to be.“viable, dynamic given population.

and positive instruments of social progress” (P B Desai), then*.

The health education and care programme carried out by

primary health schemes should first of all become the subject. the voluntary organisation Village Community Development

matter of social science investigation and critical analysis.. Association (VCDA) in the remote hilly areas of the talukas

. We present here below some/socio-psychological observa of Mulshi and Velhe (Sahyadri Range) was considered as pro

tions and conclusions drawn from a social science study of viding an adequate field of observation for such a scientific

a limited voluntary health programme undertaken by a small investigation by the Centre for Co-operative Research in

NGO in remote rural areas of Maharashtra. The study is not. Social Sciences, Pune which conducted the study with a grant

directly concerned with such objectives as the raising of from the ICSSR. The health programme under study is part

September 1986

43

of a wider educational programme (called “School without of autonomous self-determination as well as develop the

Walls” and comprising mainly non-conventional program theoretical ability of the group of health workers.

The validity of in-depth studies is not to be undermined

mes of cultural action for children and women directed

towards children’s and women’s organised collective action) with regard to the needs of those concerned with macro

which is itself a part of a much wider programme of “con- planning and large scale policies. Macro-level planning

scientisation” and organisation of the deprived sections of cannot with impunity overlook the conclusions of in-depth

the population of several rural talukas around Pune. The analyses. Planning remains a futile exercise whenever it does

health programme is carried out in areas deprived of any not take into account the dynamics operating at thegrassymedical services. Quite recently, the government made an root level.

The scheme under study not being a medical care scheme,

effort to implement its CHV Scheme. A few private practi

tioners sometimes visit the area to give injections and to make sampling methods do not suit the objectives of the investiga

money from the population. Medical officers of the PHC tion. The changes.occuring in health preceptions, practices

(Velhe and Paud) do rarely visit the area, except for enlisting and conditions are evaluated by several types of qualitative

“cases” (tubectomy operations). Sanitary conditions arc procedures. One of the most significant is the so-called

particularly bad. Animals are kept inside the houses. Many “sociological intervention”: The sociologist and his assistants

villages are cut off by the monsoon rains. In the dry season, intervene at the time of seminars and analytical exercises,

very few villages are directly connected by a bus to the taluka in-depth interviews of individuals and groups of health

centres. The scarcity of land»does not permit a sufficient and workers on a specific theme; personal interviews of villagers;

balanced diet. Traditional representations about diseases and inquiries made by some trained health workers, personnel

narratives; minutes and reports of usual meetings and free

their treatment are generally prevalent.

The main aim of the study was, to document a few pos discussions among the health workers; and role-plays. No

sible ways of reciprocal determination, among marginalised questionnaire nor schedules were used; only guide-lines were

rural population deprived of elementary health services, of always carefully prepared for conducting discussions. The

study was spread over two and a half years (1983-1986) as

three series of processes:

(1) The spread of medical knowledge and the consequent a sort of continued analytical effort following and accom

improvement of health conditions among marginalised rural panying the evolution of the action programme.

population;

Awareness of Identity among Health

(2) The process of socio-cultural and socio-political

Animators (HAs)

awakening especially with reference to the representations

about health and body and the present disfunctions of the

The most decisive step consists in generating a basically

health care system, with the consequent people’s collective new approach through a sort of cultural labour prompting

initiatives of organisational attempts to deal with health the volunteers to discover their identities as HAs in a way

problems as well as other related issues;

quite different from their own expectations obviously model

(3) Autonomous and alternative efforts to promote led after the social patterns and the collective representations

attitudes and concrete attempts of collective self-help in shared by the population at large.

respect of primary health education and care among the same

After two to three years of health training and practice,

weaker sections.1

HAs unanimously acknowledge their complete unawareness

The assumption underlying and motivating the study was at the beginning of what health might'mean. The contrast

the conviction of the necessity of such a reciprocal deter between the perceptions acquired during many months of

mination: failing this, no health development scheme—be continuous training and involvement and the remaining

it of a minor scale—can significantly contribute to the radical memories of the initial understanding leads to an evaluation

changes needed in this field. The aim of the qualitative study of what happened.at the begining. First of all, the idea, let

was to describe and establish the nature, the extent and some alone the wish, of any health activity being undertaken by

forms of this mutual positive correlation.

the population itself, did not emerge of its own from the

A second aim was to draw observations and conclusions people concerned or involved as HAs or as beneficiaries.

relating to and bearing i4>on concepts and procedures of What then was the motivating factor prompting them to

development—and especially of health development— of undertake health tasks? People from the lower sections

processes of cultural, social and political awakening and volunteered to undertake a health activity on account of the

organisation of the marginalised sections of rural popula moral authroity that their organisation Garib Dongari

tion. These latter processes are obviously leading towards Sanghatna (GDS) had acquired and of the trust they had

redefining the epistemology of development. The case study already put on the external social agents who floated the ideal

sheds some light on these theoretical issues with regard to (the main animators acting as catalysts of GDS). It is obvious

underdeveloped rural masses the health needs of which have that without the on-going organisational process such a

been consistently neglected.

prompt response, would have been impossible. Without such

Three aspects characterise the methodology: The analysis a collective social support with its components of moral

is jointly and cooperatively carried out at all stages, with authority and confidence, neither the. idea of a health task*

those concerned and involved in the scheme, resorting to would have been effectively welcomed by a deprived popula

methods of collective self-analysis and research-action. Such tion nor any man, let alone a woman, from lower sections

a methodological approach is expected to promote a better would have dared to volunteer.

critical consciousness and consequently to foster the process

Secondly, in the absence of an awareness of the urgency

44

Radical Journal of Health

of health issues, what representations defined and accom cess to, the sharing and circulation of. medical knowledge

panied the idea of a health task? The possibility of some among rural lower sections. Secondly, a health scheme is

honorarium was a very strong constituent; the vague desire bound in the first instance to be specifically ‘recognised’ or

of some sort of ‘employment’ was also there; “to become understood, from a socio-psychologically point of view,

a doctor!” was a widely shared expectation; “to distrubute through the established patterns of representation concerning

medicines and pills, to give injections, or to become a dai”: doctors, health and therapies. There may be therefore some

such was the most substantial content discretly related to naivety on the part of action groups to resort to health as

health; some had really no idea of what could be the task an entry point if this means that health, as such, on account

expected from them; there was a strong apprehension, of its urgency, is expected to easily generate radical social

especially among illiterate women, about their ability to com insights. The prevalent unawareness about health as a

prehend; some daring pushed ahead all of them and some personal as well as social issue and the deeply imbibed preliking too. When we. compare these initial representations critical and unconscious cognitive structures in this respect

with those brought about after three years of experience, make health one of the most deceptive and difficult ‘entry

three main shifts appeared to occur in the preceptions. Firstly, points’ if one looks forward to it as a lever for radicalising

from static notions of social status and prestige position rural populations.

In such circumstances, a main concern of a health scheme

associated with the health profession and the expectation of

an employment, the approach evolved towards activist consists in defining the role of the HA. This had been and

attitudes, became action-oriented and conceived in terms of remains one of the main themes of the regular and con

actual achievement. The systemic outlook was altered into tinuous training programmes of HAs in the VCDA scheme.

a dynamic attitude. Secondly, from self-preceptions in terms As a result of discussions among all those concerned by the

of ignorance, fear and inferiority feelings, there was a shift scheme, doctor, activists and mainly HAs, the following write

towards self-confidence, boldness. Their ability to assimilate up was prepared as a basic chart of the HA’s role, as an

knowledge enhanced the self-image. Inhibition gave way to operational model.

self-assertion. Thirdly, from an individualistic outlook and

Our Health Work: Why and How?

wishes of private profit, there was a shift towards a social

—We and our children fall sick every now and then.

understanding.

—When we fall sick, we never get medicines soon, nor do we get good

The interest was hence motivated at the start by the hope

medicines.

of a small honorarium (discontinued later on), by the wish

/. Why du we fall sick so often?

to be a ‘doctor’, by the desire to escape deceptive practices

The

reasons

are

that:

of the private doctors, by the pleasure of getting informa

1 We do not get enough to eat nor is the food good. Then, as a result,

tion “when we realised that we could understand it”. The

we become weak.

interest of those who had no specific liking for the topic was

2 We do not get enough of water, nor clean and pure water. As a

result in the dry season, scabies increase and in the rainy season, diar

raised when they learnt something new and delivered a few

rhoeas increase.

pills. After two or three years, four main motivations are ex

3 Our living quarters are small and not clean. We keep our cattle

pressed as follows at the time of health seminars: Let us give

inside our houses.

information to the people. Let us sit together and educate

4 During the rainy season, we work exposed to cold winds and we

people. Let us organise the people. Let us be self-reliant. Later

have not enough clothes to put on.

5 Our work is dangerous, instruments arc primitive and insufficient.

new-comers, all women, all illiterate, who joined a scheme

As a result, accidents occur; we are overworked; we quickly tire and

which they had observed, give ,the following reasons for

we do not pay attention to our health condtion.

taking up this responsibility: to get a new education and

6 Many times, we are overwhelmed by difficulties: as a consequence,

training; if they fall sick, to be able to do something by

our mind does not remain sane. The pressure of the male domina

tion upon women is epccially heavy.

themselves; the good results of the medicines circulated by

7 The government has no money the government people do not give

the HAs; no money to buy medicines from private doctors,

us information. But it takes great care of a handful of privileged

but cheap pills available from the HAs, even on credit;

people.

doctors take a lot of money and do not treat unless paid

8 Bad habits: alcoholism, tobacco etc.

beforehand; interest in this topic; if they now learn, their

9 Frequent pregnancies.

10 No vaccination.

children can be taught... To the question that such interest

If we could get rid of these difficulties,.then we would not fall sick

may not be sufficiently strong when male pressure is raised

so often. But, today, these difficulties cannot be removed. As a con

against women taking the lead, the answer is that: “We have

sequence, the frequency of diseases cannot immediately come down.

been selected by a group of people during a meeting. We have

2. Why do we not get proper medicines when we fall sick?

the support of people”.

1

There are no doctors in our area; the ‘medicine men’ are many, they

As a matter of fact, external support is not sufficient. The

deceive us.

female new-comers maintain their involvement out of a

2 The doctors who come iqto our area, behave like 'medicine men’;

strong inteYnal conviction: “We have seen the earlier ones.

for instance, for no reason, they put on a very serious face, use difficult

They committed themselves to this work. They have not

words which they pronounce like mantras and create an atmosphere of

mystery. Although there is no need, they give injections and prescribe

eloped or have been taken away by men! The provision of

useless medicines. The medical profession is being converted in to a

a health education scheme, to succeed or fail for many

business like any other business. It is a profession consisting of selling

reasons absolutely alien in nature to the health issues tackled

medicines. The more money you give, the belter treatment you .will

by the scheme. One of them has been suggested above con

receive. A doctor is no different from an agent of a drug company.

cerning the social factors conditioning the desire for, the ac

Doctors behave like dealers:.they store the knowledge as shopkeepers

September 1986

45

store the commodities ano make us more expensive. There is a com

petition for consumers, (as among dealers) to obtain more consumers

and gain more money.

Where is ’humanity’?

3

What is clear about today’s doctors!

Doctors do just sell treatments. Moreover, oh account of the doctors’

behaviour, some ideas are firmly embedded in our minds, for example:

money is everything; the knowledge of the doctor is very complicated.

We shall never be able to understand anything of it; Our health depends

upon doctors; Doctors’ work is intellectual and of a much higher grade

than our labour in the fields.

4

tices of medical care; 4) al raising the level of socio-political

awareness of the whole population in this respect through

health education, self-reliant practices and collective health

action as levers, thus contributing, in its own way, to

strengthen the overall health movement; 5) at resorting to

operational concepts and criteria of evaluation of a social

and cultural nature instead of giving priority to and taking

only as operative norms the quantitative medical im

provements in the health status of a given population,

objective that at any rate the NGOs are unable to achieve—

particularly the small ones—on a suficicntly large scale.

What is rhe use of our health work!

Selection of HAs

We cannot bring about important changes in our condition, so

exposed to diseases with our health activities. The reasons are as

A general model remains futile without its operational con

follows: Our health condition depends much more on many other

cepts. The selection of HAs is one of them. With rare ex

factors of our whole environment than on medical factors; the

ceptions of selection being made by the external main

knowledge that we can get about health as health animators is limited.

animators of GDS, the HAs of VCDA were regularly selected

The pills and medicines that we give are simple and not many.

What then is the use of our health work?

by local groups of GDS during their meetings (with the ‘per

We want to bring, at this primary level, a new concrete way of under

mission’ of the husband or parents for the female HAs). A

taking health work. An example will make it clear. What is the

few women were selected at the start on account of their

difference in the health work, between the method that is usually

activity as teachers in a voluntary nursery school of GDS.

followed today, and our method? This will be clearly understood from

the following example

Sometimes special meetings were called to deal with this issue

Let us suppose that a lady health animator from our group attends

and several meetings were necessary to make a selection. In

a child suffering from summer diarrhoea, what will she be able to

the course of time, when new volunteers joined, they were

achieve?

all co-opted by the local groups of GDS. The selection was

Change in the body. We shall be able to win over the disease which

affects the body of the child.

not a sort of casual appointment but the result of group

Change at the economic level'. A good treatment can be given at a

discussion and exchanges among the assembled people.

very small cost. We can demonstrate it.

When the health workers look back and consider the pro

At the level of health consciousness: The health animator can change

the ideas of the people. What will she/he tell them?

cedures of their initial selection, they come to the following

1 Why diarrhoea occurs, what is the treatment, and if it can be conclusions.

prevented. This techincal knowledge about diarrhoea will be given.

At the beginning, without any experience of procedures

2 Why diarrhoea occurs much more often among the poor and

of collective determination, “We had no idea of the method

in the villages. How the proper preventive treatment of diarrhoea

depends upon a proper water supply. Why today’s doctors and drug

followed, and we did not understand its importance’’, confess

companies lake pleasure in treating diarrhoea with very expensive

all of them. The cooptation process from within a group for

medicines. This is social knowledge that the health animator is giving.

a task to be carried out. in the name of a group or mass

3 How there is no need for a doctor to treat simple and minor

organisation

was a procedure absolutely unknown. They did

ailments and what is the opposition of the private doctors to this

not realise the meaning of this process. Three years later in

statement.

4 How we can deliver people from the exploitation of private 1984, all of them except one woman who dropped out express

doctors.

the firm conviction that it is proper to make the selection

5 How in our health work there is no domination of the doctor.

from within a group of assembled people taking a common

We don’t give him undue importance.

6 Why, despite so many promises and announcements on the part decision.

of the government, this latter cannot seriously undertake genuine

The reason are the following:

health work of that sort.

The selection should be made according to the ideas that

7 This health work is going on in a nice way, because we arc

the people have about it. Their ideas should be taken into

awakened, organised. Our health work will progress to the extent our

consideration; A private selection is a mistake; when there

awakening and our organisation will grow.

8 Still, as long as food, water, shelter, education, cloth, etc. are not is a decision of a group, the selected person feels responsible

available, we shall not stop falling sick time and again.

to the group and the group responsible to the individual. This

This definition of the HA’s role tries to give a concrete

design to a specific concept of health work among and by

marginalised rural population. This concept ought to be

made explicit. The health work in such a context is conceived

as aiming 1) at forging a collective health consciousness based

on a critical perception of the relation obtaining between

people of lower social strata and their actual physical en

vironment and specific social constraints; 2) at making ex

perimental attempts which constitute perse a practical criti

que of the prevailing methods and structures of the health

care system; 3) at projecting in an embryonic form a sort

of miniature model revealing the feasibility conditions of

alternative values, norms, organisational patterns and prac

46

is bound to generate a reciprocal questioning of both of

them. And such habit should exist; in the case of a private

selection, people will not feel like cooperating with the one

selected, nor give him/her their support. When a meeting

is called, everbody will find an excuse for remaining absent.

The model to be followed in the future is as follows:

“In a new village or a hamlet, we shall hold a meeting on

health and give some information about it. Then, we should

tell the people: To tackle your problems in this respect you

should select your own man/woman for that”.

Why should this procedure be followed? This process

induces the awareness of a reciprocal responsibility; It avoids

the danger of pressures of vested interest and the criticism

Radical Journal of Health

attending training course ih health or undertaking health

tasks. Only women upon whom husbands and family could

not keep a firm control were so allured. Their volunteering

showed their lack of social restraint and fear. “Men and

women sit together!” “Women just like to follow their

whims!” It was almost out of lust that they had volunteered!

4 The fourth image was that through this scheme, a dispen

sary would be set up, medicines and pills would be made

available. In this respect, as people were saying that “an

educated man is needed to give medicines”, women had

doubts about their ability to prescribe medicines, as they were

conscious of their ignorance and absence of education.

These data show that two main and anti-thctic socio

cultural cognitive structures gave readymade referential yard

sticks to understand and evaluate the event. The first

reference relates to the women’s roles and image: a woman

should never go outside of the home where she is confined

to subordinate and non-prestigious tasks. The second

reference relates to the prestigious function and role of a

doctor as a supplier of medicines and health services. As the

health animators were considered as doctors, these two

referential factors clashed and as a consequence, the women

were derided, for assuming a role of high rank and superior

knowledge!

The basic and spontaneous point of view was not a

technical or practical approach, but a social reading; and

this reading was no conceptual insight nor analytical appre

hension. It was a judgement. The cognitive structures

worked, as a judicial recognition, not as an act of cognition.

How Villagers Perceive Health Animator

If this is likely to be the case in any transfer, its sucess depends

Another determining factor, mainly at the initial stage, is upon the will and the ability to develop a conceptual

the perception of the beneficiaries and their expectations. understanding and to refrain from any hasty and spon

Four types of reaction characterise these altitudes, in the taneous interpretation by referring to the in-built structures

perception of HAs, which symbolise four cognitive struc of recognition which can lead nowhere but to a judgement

tures through which villagers spontaneously approach this which is only a reduction to the same. This seals the

health experiment.

impossibility of any progress.

This is obvious in our case. If the judicial recognition turns

1 “The village has got a big ‘doctorin’!” This derogatory

into

a judgement against illiterate women and ignorant men

remark related to the women health animators. It points out

firstly, that the health worker is considered as a ‘doctor.’! And taking up the role of a ‘doctor*, as this is simply a contradic

secondly, that the prestige and honour implied in this image tion, still a women may be considered as positively motivated

serve conversely, to ridicule people—, especially the women, to take up this task for the reason that she wants to bring

or the illiterate workers—volunteering for the scheme being home some income, for the benefit of her husband and her

projected so suddenly to such a high position! People did children, as the source of wealth of the house {dhana). This

not react mainly in terms of the concrete advantages of the is also a very clear cognitive structure regarding the role of

scheme, but with regard to the social image of the doctor a woman. The understanding of her desire to become a health

and to the concept of health as a doctor’s commodity both animator is therefore either, negatively, a will to escape her

of them turned into arguments meant to throw discredit upon duties at home and the control of her husband, or positively

ignorant people pretending to be more clever than they were a justifiable intention of bringing home (to her owner, for

the benefit of her house) some wealth, as she is a lakshmi.

to involve themselves in these tasks!

or the mockery against the one who is chosen; this process

assures cooperation, support and participation; there cannot

be any real work by an individual alone.

What do these procedures aim at?

These procedures impart information to the people

(doctors never impart information about health and thrive

upon the ignorance in which they keep the patients; people

get a chance to assemble, exchange and make an effort to

solve their own difficulties; the objective is to become selfreliant, “to stand on our own feet”; this helps to strengthen

and spread the organisation GDS; the intention is to put an

end to the deceptive practices of doctors and of the local

miscreants who act hand in hand with the doctors; this brings

a health knowledge to the village level; this develops a health

consciousness; this gives the women an opportunity of having

some role and stand in society; this offers a chance to

everybody of speaking out.

Let us draw one clear operational conclusion from these

data: the perception of health as a collective issue that

confronts the whole community is generated here through

a social process of cooperation, by the group, of a volunteer.

It is not the perceptions of health as a community problem

which comes first and leads to a renewed social practice. Il

is a renewed social practice which helps developing a new

approach towards health, as it could have been with any other

issue. There cannot be any real consciousness of collective

responsibility unless it takes the form of an appropriate

pattern of social relation or a cooperative social formation.

2 This work was looked at as sort of employment for the

One operational conclusion can be drawn from this. If a

volunteers. As the possibility of an initial honorarium of health scheme aims at engineering a process of social change,

Rs 50 was known, the task was considered as resorted to by vfz, a transformation in the patterns of relationship and

the volunteers under the motivation of this material incen values, it should and it could boldly create a situation which

tive. The women would then be able to bring their contribu will directly challenge the cognitive structures mentioned. For

tion to the maintainance of their husband and children, as that purpose a health scheme should not start with doctors

they are the dhana of the house, its source of wealth, its and medical services run by doctors: health should not firstly

lakshmi.

' ,

be looked at as a technical task. Secondly, the leading role

3 The third understanding is that this task was just a in the implementation of the health activities should be given

chance offered to the women’s eagerness for being ‘set free’, to those women whose health is the most affected by the

abandoning the household duties under the pretext of present health system. These activities should mainly and

September 1986

47

basically consist in imparting elementary health education

to women and more technical knowledge should come as a

secondary dimension. A health animation activity under

taken by women of the lower social sections, taking the initi

ative of visiting and educating village population is likely

to prove one of the most effective levers of social change in

the rural areas, as this practice breaks off strongly built-in

cognitive structures which have a definitive repressive role

and are very significantly responsible for the perpetuation

of a particularly degraded health status among women: the

partiarchal patterns of relationship and values, and the undue

prestigious status of the (male) doctors as the only ones

capable of dealing With health and medicines.

Socio-cultural Pressures Against Health

Animation

Between 1981 and 1984, out of an initial group of 30 HAs

(14 men, 16 women), 17 dropped out (6 men, 11 women),

while 18 new comers volunteered (1 man, 17 women). Those

who remained involved had collectively analysed the reasons

why so many dropped out—26 answers-could be specifically

given for the defection of 17 HAs. These answers arc

classified into 9 categories as follows: .

1:3 male and 3 female HAs abandoned as they did not

obtain the expected financial profit. The honorarium was

considered too meagre; even this was discontinued and

substituted by small help given on the basis of the days spent

on house visits and meetings held, etc. Motivations were put

to the test.

2:5 female HAs left under the social repression obtaining

against women’s assertiveness.

3:2 men and 1 women left for reasons of economic pressure

and poverty.

4:3 men left out of diffidence about their own ability and

social inhibition.

5:1 man and 1 woman were frustrated in their expectation

of a higher status sought through this activity.

6:3 left on account of personal reprehensible behaviour.

7:2 women left because they could not cope up with

the task.

8:1 woman could not bear the clash between the knowledge

received and her traditional beliefs.

9:1 woman left out of lack of proper motivation.

These reasons are indicative of the difficulties and of the

nature of the psycho-social determination of those who

maintain their involvement with a renewed conciousness. It

is obvious that almost all HAs joined the scheme with the

thought that they would get a sort of paid employment thus

improving their low social status. As a matter of fact, if all

of them could secure through this programme somehow

better social position, a qualified social recognition and some

social respect—and self-respect—, paradoxically would

remain more involved in the scheme than those who were

usually deprived of such social respect, often denied the right

to talk in the open and assert themselves, while those who

already enjoyed some social prestige left an activity which

appeared to them as not enhancing their dominant social

position, or even countering it.

One should be fully aware of the basic difficulties which

any attempt of popular health movement among under-

developed rural population has to overcome before becom

ing a strength. If we are convined that there is no alternative

to such a movement for bringing about significant structural

changes in the health care system, wc ought to be still more

aware of the socio-cultural challenges this implies in the first

instance. Two testimonies may convey the magnitude of the

challenge. The first one is the testimony of a woman HA

whose potentialities as organiser are totally repressed by her

husband.

I was conducting a balwadi under the sponsorship of VCDA since

one year. On this account, 1 was, therefore, going from house to house

to fetch the children. ! found many people sick during the monsoon.

Althogh they were suffering from simple ailments they were going

to the doctors and taking injections. Doctors were coming from outside

and knew how to take advantage of this situation; they collected and

lot of money from the population for this. I thought, let us do

something about these minor ailments, through health education. Then

I volunteered to become a health animator

Private doctors do not give information on about diseases, they

just give medicines. They come to our villages only to raise money

from the population. I started telling people thus and trying to con

vince them. Six women came together and, through the Association,

wc requested Dr. Phadkc to come and impart health education. The

doctor used to come twice a month in the beginning and gave us infor

mation about the children’s and women’s health. We were getting Rs

50 as honorarium.

In the beginning, women called me names. But, later on, opposi

tion become less. People trusted the information that wc were giving

them and followed our prescriptions. Similarly, they could observe

by themselves how the government doctors functioned.

When I had to go and attend a meeting (training camp) and spend

one night outside, my husband would object. “Who will look after

our daughter who has reached the age of marriage? The younger

children are going to school: who would look after them?’’

I have now after three year accepted the job of becaning health

worker of the government so that the health education that I received

during these years is not wasted. They organise only one meeting per

month. When VCDA stopped giving the Rs 50 honorarium for

the health work, my husband became completely opposed to my parti

cipation in these activities. This is the reason I accepted government

work. And I continued this health activity with the same motivations

that I got from VCDA training

With the government we do not hSv’i the freedom to function as

we think right; we have to do the wortonly in a very particular way.

Although I have accepted the wor^’of the government I like to at

tend the meetings and the camps for women of the VCDA My ex

perience with the government is very different. People get absolutely

no health education from them. Only one thing matters: to distribute

pills and to keep monthly records. This is what the health officers

consider good and important health work.

Should b®.abI.c 10 slud>' as we were doing which quesons the women shou d think over and take up. For instance, women

educatioanmOVCment

drinking Watcr’ as a resuk of thal

fn

^ond testimony is the account of the difficulties

!fpvddnf d heby l \e 8r°U0 Of HAs from panshet whose

level of deprivation makes difficulties more acute. 1) The first

t^teaeh*

°nrT d^^ 3b°Ut °ne’S 0<Vn abilitv lo folloW

a^d

W? s' dOClOr’ “We Sha11 not be ab* to learn

ana stuay: \\e were not educed»• >

anything about health, dispensary medicines ” Therewas

no conviction of one’s ahiltrv

‘ 1 nere "as

of the doctor. None of the HAs had

COrre?ll:‘'

!essons

anv meetinn nr ...

.

LVer previous!.- attended

any meeting o expressed himself in a group “For three

months I just kept silent in the meetings'”

as "any XZXdSXZ hUT beinSS- “ mUCh

48

Journal of Health

and cattle. Where is the government? How to go and meet in the HAs and in the organisation a direct challenge to their

them? We did not have any idea about it. We had no idea authority. “They arc not Dhanagars (in one area, many HAs

that we had also rights. HAs were requested to commit were from this caste), they are foreigners: they come to collect

themselves to assume a social role when they had hardly a girls and send them abroad where there is a want of girls.

clear consciousness of their own identity of social beings. One should not vote for them. If they can get four votes,

No wonder this generates a strong feeling of self we can still have ten of them... Listen to the head-men of

diffidence. “I am afraid that people will not come and attend the village. This is not proper. Our women should not talk

our meetings, nor listen to us.” Still, “I am convinced that with men from outside!” “The HAs get plenty of money:

going out to attend meetings, I shall learn something. How this is the reason why they roam about”. “They get medicines

long should we continue to submit and surrender to the free of charge and take money from us!” As expected, the

same leaders make capital of caste feelings to object to the

leaders?”

Going alone from house to house to give information fact that HAs of different castes assemble together, and do

about health was seen as a great difficulty by some. Some not listen to the caste elders.

A few drunkards come to disturb the meetings, teasing,

felt it was easier to impart health education in a meeting,

within a group, when people are assembled together, because shouting, raising their voices with the result that people

there can be exchanges and discussions, and those who cannot express freely their difficulties, despite their genuine

desire to do so. In the beginning we did not know how to

understand can help others to learn.

There was the reluctance to listen to women: “They cannot handle these trouble makers”.

even behave themselves in the society and look after them

selves! How should they come and teach us! Men teased the

Dynamics of Self-Assertion

female HAs, especially after having had their drink, “We

The

interviews

of the new-comers—all women who happen

shall, all of us, now, become doctors!” “Why make everyone

to

join

the

existing

groups of HAs reveal the following

a doctor also like you!”

The pressure of the authority of elders especially upon processes:

Personal acquaintances and a prolonged time of “wait

l)

women makes these latter still more shy and inhibited to

undertake something new and unusual. Men complain and see” attitude preceded any decision. The example and

against women that they attend meetings and report there the concrete testimony of some one else are necessary as a

about the drunkards of the village and all their stupid and preliminary step.

bad behaviour, and first of all about their insults against the

2) A clear invitation to join was made, not to elicit a purely

HAs. The pressure of the more influential male leaders was individual move but a commitment tp participate in a col

and remains a serious difficulty for the women who volunteer lective effort.

or would like to volunteer.

3) The initial step were met with laughter, counter

The countter propaganda objected that outsiders had come

propaganda,

lack of appreciation on the part of the

and trained HAs who immediately listen to them and follow

them, falling a prey to them. “We should only look after our population.

fields, eat peacefully our pancakes of millet. Women should

4) The decision to join was personal and motivated by a

just go to the fields or to the forest for their tasks, earn a will to achieve something and dedicate oneself to a task

few rupees for the house; this is better than attending meeting whose relevance was understood.

and roaming about, everywhere, doing nothing, whiling the

5) This understanding increaseed the strength of the

time in useless activities which do not yield any income. What

will you get (money) from this work? What will these people personal motivation and developed progressively a wider and

realistic social consciousness.

give you?” Aren’t they already ‘social workers’ in our village?

6) The motivation takes momentum, against objectidns,

(leaders who are supposed to care for the welfare of the com

munity). Local leaders do often call women names because out of one’s own effective commitment to tasks which arc

they follow people from outside instead of going to work experienced as beneficial. Action generates self-assertion.

to bring home a few rupees, listening only to them and

7) The group proves to be the best support for the personal

keeping a submissive attitude towards them.

efforts and commitment: A small group of like-minded

Another type of counter-propaganda says: “What did you

people is the essential structural factor.

obtain and what did you give us after three years?” The

8) The elements of general personality development (self

understanding behind the objection is that the organisation

should immediately bring in some material improvements assertion, ability to express oneself and talk in front of a

to show its credentials, to the population, free of charge and group, capability to understand a knowledge considered as

without any effort on their part. The reason motivating the difficult, etc,...) work as an encouragement.

objection is also that the organisation “of the poor of the

9) When money is seen as the main motivating factor, no

mountain” is approaching directly the administration and effective health animation can be sustained. Monetary com

demanding the implementation of the government schemes pensation may not go against a real interest in health and

for the benefits of the needy, independently of the local health education, but once such an interest is maintained by

leaders who have a vested interest in the poor depending upon monetary incentive only, we cannot expect it to develop into

them.

a social concern and commitment for health animation and

HAs insist upon the reactions of the local leaders who see community organisation on health issues.

September 1986

49

shows their superiority and “if we ask, we arc left with the

following answer: “You are ignorant! What can you under

stand! Don’t you have confidence in me?... I told you once,

HAs wished to co-operate with the government health I shall not repeat... and so on they simply do not care

services rather than compete with them. A voluntary scheme for whether we understand or not: nor why we cannot

is no substitute to public health sevices. The several attempts understand.

^A second feature consists in not giving information about

made by VCDA to operate jointly with the government servi

ces met with only a little success. As our concern here is with any disease: they would just hand over medicines. They never

the local socio-cultural processes, we shall consider only the impart nor show any readiness to impart knowledge about

psycho-sociological dynamics obtaining between HAs and health qnd disease. Mainly concerned with cases of family

PHC personnel rather than the possible forms of co-opera planning, they do not give due attention to the sick. Expecta

tion. Let us give due attention to the perceptions of HAs con tions regarding money are another main feature of their

cerning the behaviour and the attitudes of th;'government behaviour. The question may often be raised, from the start.

personnel, as articulated in health seminars^by HAs.

If there is no money, the patient may be sent back or adviced

1. Government doctors are to be seen at the taluka centre to come later, or another day... Money and injections are

and in the villages only in the specific places where com two main aspects of the doctors* behaviour. •

modities and facilities are available. Government doctors will

The doctors would also easily entrench themselves behind

always be seen in the company of a limited, restricted and the laws and rules of the government. They do not appear

specific category of people: with the sarpanch, the patil, the as responsible towards the population; they are not answer

teachers, and sometimes the talathi and the kotwal. Their able to the people.

social place is with the leaders, the rich, the notables, “with

These frustrations and clashes with regard to the medical

those who talk”. They will behave with them with civility. practices of the government personnel lead to conclusions

They will be attentive and considerate with the established already often drawn but naturally stressed by HAs in their

notables andje’aders. They will be seen in their home places. analysis.

They will accomodate them immediately when these latter

1) The doctor’s services are alien to the needs themselves.

come to meet tham and they will attend to them without “Our main expectations is that the government doctors reach

delay, and show them small courtscys. The government us, the poor, who need them. They don’t. They never come

accordingly behave also as local leaders.

to the houses of the rural poor”. “We don’t know what the

2. The attitudes which motivate their way of talking and word nurse mean. If it a thing to be eaten, or an animal?”

their behaviour lead them to make a show of their superiority “We asked the PHC officer to send us a nurse: he just

a^d importance. Their arrogance is resented by the people; promises but nobody has ever come”. Once, at Sakhari,

they do not let others talk and express themselves. They speak thanks to the firm insistance of HAs, doctors came and HAs

fast and loudly over the voice of others as to frighten the helped them to vaccinate the children. HAs motivated and

people. Their manners show that others are not worth assembled the people. Then the doctors promised to come

attention, being all ignorant people. “They consider the poor to another village, Dudhavan, under the pressure of the HAs.

as stupid and childish”. With the poor, they are, insulting But they never did. The false promises of doctors to the HAs

and offending their feelings; they do not give answer if poor are a permanent matter of tension, diffidence and disgust

people ask questions.

about the government health care system, and its personnel.

3. A few features characterise their language and ways'of Another area of tension is the insistance of the government

addressing the common people. They often use words (some personnel that HAs should bring to them women for being

special or English words) that people cannot understand^ sterilised. The government CHV are supposed to do it, why

with the purpose of not being understood. This language should the HAs not give priority to this too? HAs answer:

Chart

Antagonistic Perceptions and Conflicting

Practices

We HAs

The Government Health 'Personnel

— We go antf visit the poor at home

— We arrange for few cheap and good medicines being

supplied to people

— We give priority to the people

—We educate people

— We look at the patient and give the appropriate

medicine

— We think of the whole environment and situation

— We select HAs taking into account the ideas of the

people

— We organise people for collecting action oq health

problem

— We promote health consciousness

— Health is a public issue and a political question

— They enter only in the house of important people

— They give importance to medicines

50

-t They give importance to money

— They just distribute medicines

They don’t give all the medicines required to cure

the patient

They don’t bother for the whole environment

— They make private choices

— They don’t try to assemble the people

- They don’t bother about health awareness

- Health is a private problem to be solved by doctors

Radical Journal of Health

Conclusion

“You don’t give any protection to our childre. Four live and

four die. First come and attend to our children, save them

and we shall bring you plenty of cases. Otherwise, why should

we undergo operations?”

Strategies of “Health For AU” will prove effective when

we succeed in translating them into alternative social prac

tices of “Health by the People”.iThe chart on p 50 is an

2) The health system is not directed towards the people. attempt made by HAs of VCDA, on the basis of.their

Those HAs who were absorbed in the government scheme: experience, to define antithetically, these alternative health

“During the training meeting organised by the government practices required as a foundation of a people’s health move

every month, doctors and their CHV pretend that doctors ment among rural marginalised population.

In view of the magnitude of countervailing forces, there

are ready to go anywhere. If HAs protest that they have never

seen them, that doctors make promises which they never is little likelihood of such alternative health practices gaining

keep... Government doctors and their CHVs look down on their own a significantly large and lasting momentum

upon us, repress us as women who talk too much and had unless (1) they are locally part and parcel of an appropriate

better shut up in front of them! When we asked the doctors: wider peasant movement putting out similar roots,

“Why do you take money from people, regularly, although (2) externally backed by and related to, other branches and

you are paid by the government?”, doctors reply angrily: • forces of the national health movement and (3) internally

“Why don’t you take money yourself also from the people?” born by a permanent self-learning exercise addressing the

Doctors insisted and added, addressing a dai “before doing anthropological, socio-cultural and ideological dimensions

any delivery, you must first ask for money from the people”. of the primary health issues. For lack of space, we did not

Doctors advise their CHV: “You had better stay at home. . deal here with these pedagogical, anthropological and

Do not visit houses.” We, HAs, tell the people: “Go and see ideological components as essential to any effort towards

the CHV of the government.” People reply: “They do health by the people.

nothing. They do not inform us. They do not come and

References

attend us. They tell us nothing, they just give a pill”. We tell

people: “It is your right to go and meet them and avail from Alma Ata 1978: Primary Health Care. Report of the International Con

ference on Primary Health Care, Alma Ata USSR, WHO-11978.

them their services. It is a government service.” People reply:

“We prefer to come and see you. No improvement is gained Bose A and Desai P B, Studies in Social Dynamics of Primary Health

Care, Hindustan Publishing Corporation, New Delhi, 1983.

from them. They are of no use”. Doctors tell us: “You want

Djurfeldt, Goran and Lindberg, Pills Against Poverty, London, Curzon,

conflict... You organise demonstrations... We shall also

1975.

organise such demonstrations... You cannot even sign your Health for All: An Alternative Strategy, Report of a Study Group set

name and you'immediately strongly reply and object to what

up jointly by ICSSR and ICMR, Indian Institute of Education, Pune,

1981.

we say!”

3) The selection of CHV serves vested interests. In Panshet

area, when the CHV scheme started, HAs insisted that

women should also be taken, and not only men, and even

illiterate women. Some were appointed but no further co

operation could materialise in'other places, despite the

readiness of the HAs to help goverment officers in the selec

tion and implementation of the scheme.

Jobert B: La Participation populaire au development sanitaire: le cas

des volontaires de la same en Inde, Pevue Tiers Monde, t XXIII,

91; Juillet-Septembre 1982, Paris.

Poitevin G and con der Weid D, Roots of a Peasant Movement,

Shubhada-Saraswat Publications Private Ltd, Pune, 1981.

Guy Poitevin,

Centre for Co-operative Research in Social Sciences

Rairkar Bungalow

884 Deccan Gymkhana, Pune 411 004.

Economic and Political Weekly

A journal of current affairs, economics and other social sciences

Every week it brings you incisive and independent comments and reports on current problems plus a number of well-researched,

scholarly articles on all aspects of social science including health and medicine, environment, science and technology, etc.

Some recent articles:

Mortality Toll of Cities—Emerging Pattern of Disease in Bombay: Radhika Ramsubban and Nigel Crook

Famine, Epidemics and Mortality in India—A Reappraisal of the Demographic Crisis of 1876-78: Ronald Lardinois

Malnutrition of Rural Children and Sex Bias: Amartya Sen and Sunil Sengupta

Family Planning and th^ Emergency-An Unanticipated Consequence: Alaka M Basu

Ecological Crisis and Ecological Movements: A Bourgeois Deviation?: Ramachandra Guha

Environmental Conflict and Public Interest Science: Vandana Shiva and J^Bandhyopadhyay

Geography of Secular Change in Sex Ratio in 1981: Ilina Sen

Occupational Health Hazards at Indian Rare Earths Plant: T V Padmanabhan

Inland Subscription Rates

Institutions/Companies One year Rs 250, Two years Rs 475, Three years Rs 700

Individuals Only One year Rs 200, Two years Rs 375, Three years Rs 550

Concessional Rates (One year): Students Rs 100; Teachers and Researchers Rs 150

(Please enclose certificate from relevant academic institution)

[All remittances to Economic and Political Weekly. Payment by bank draft or money order preferred. Please add Rs 14 to

outstation cheques for collection charges]

A cyclostyted list.of selected articles In EPW on health and related subjects Is available on request.

---------- ----------------- ------------------------- ;----------- COMMUNITY HCALT! I ClJ L

September 1986

47/1, (First Floor) St. Marks

Bangalore - 560 001.

Immunisation as Populism

A Report

aslia vohunian